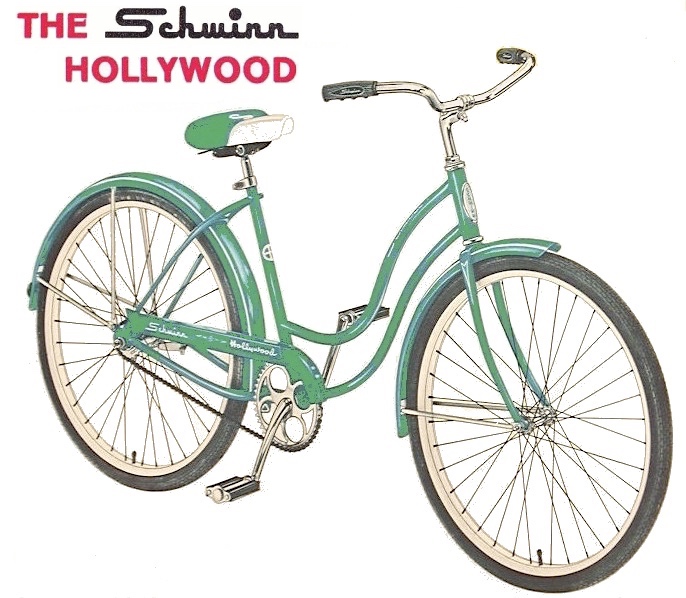

Museum Artifact: Schwinn “Hollywood” Bicycle, c. 1970

Made By: Arnold, Schwinn & Co. / Schwinn Bicycle Company, 1718-1740 N. Kildare & 1856 N. Kostner Ave., Chicago, IL [Hermosa]

The last Chicago-built Schwinn bicycle rolled off the assembly line in 1982, and while the brand name is still embossed on the badges of various Chinese imports, anybody who buys a new one is bound to hear the inevitable cranky lament from a passerby: “they don’t make ‘em like they used to.”

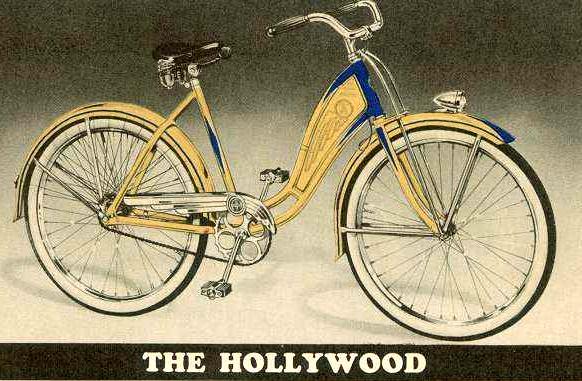

The Schwinn in our own collection is a “campus green” Hollywood model, circa 1970—a “middleweight for girls” according to a catalog from the era. “Graceful styling. Chrome plated fenders, two-tone saddle, built-in kickstand, Schwinn tubular rims, 24” x 1-3/4” nylon cord tires, ladies’ frame that’s easy to get on and off.” The bike retailed for about $60, and was originally purchased at what might be the oldest still-operating Schwinn dealer in America—Barnard’s Cyclery in Oak Park, Illinois.

The Schwinn in our own collection is a “campus green” Hollywood model, circa 1970—a “middleweight for girls” according to a catalog from the era. “Graceful styling. Chrome plated fenders, two-tone saddle, built-in kickstand, Schwinn tubular rims, 24” x 1-3/4” nylon cord tires, ladies’ frame that’s easy to get on and off.” The bike retailed for about $60, and was originally purchased at what might be the oldest still-operating Schwinn dealer in America—Barnard’s Cyclery in Oak Park, Illinois.

While the Hollywood bike was ostensibly a budget-priced kid’s option, it was still built to be a workhorse—as was the Chicago way. Our museum artifact stayed on the road for a solid 50 years, in fact, serving most recently as the trusty steed of a young Japanese immigrant in the 2010s. She zig-zagged the streets of her new Chicago neighborhood each day, learning the lay of the land on a bike that some of her neighbors might have once had a hand in building. The basket attachment also came in handy.

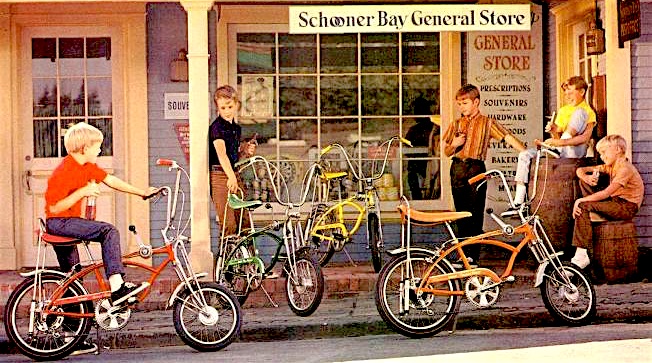

There is a thriving market out there for vintage Schwinn bikes, which is part of the reason a shop like Barnard’s (est. 1911) can still be in business today. Some buyers just like the look and feel of the old classics, while others are trying to tap into something more personal and sentimental. Schwinns occupy plenty of pages in the flip-book of Baby Boomer nostalgia, after all, coasting through idyllic suburban summer days with the sound of baseball cards buzzing between the spokes. There is an unavoidable “Wonder Years” vibe to these things.

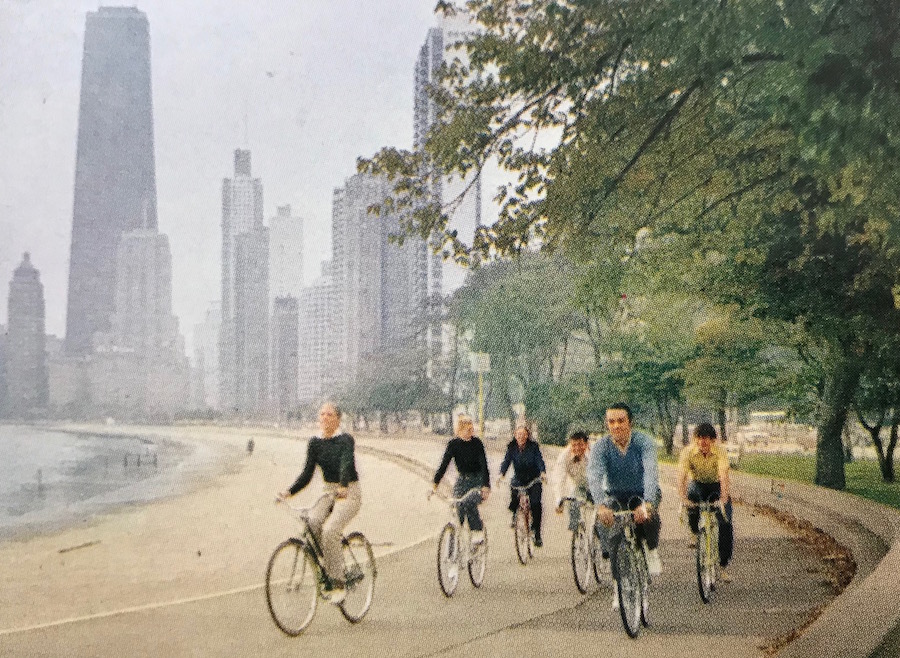

[Ridiculous picture from the 1969 Schwinn catalog]

[Ridiculous picture from the 1969 Schwinn catalog]

For all its associations with the 1950s and ‘60s, though, Schwinn’s mid-century heyday was really just an easy downhill glide after five decades of determined, non-stop pedaling. Crew-cutted Eisenhower kiddos had Schwinns on their Christmas lists because Schwinn was already the name their parents knew and respected. The brand was deeply embedded into the culture from the dawning of the 20th century onward.

As such, trying to tell the entire story of Arnold, Schwinn & Co. is basically akin to describing 120 years of American industrial development in general. The company offers just as many lessons in the benefits of persistence and innovation as it does in the consequences of tunnel vision and stubbornness. Whole books have been published on Schwinn bikes, written by proper bicycle people. We’re going to keep it a bit simpler.

[Advertisement for the Schwinn Corvette, from a 1959 issue of Boy’s Life]

[Advertisement for the Schwinn Corvette, from a 1959 issue of Boy’s Life]

Schwinn History, Chapter I: Immigrant Schwinnigrant

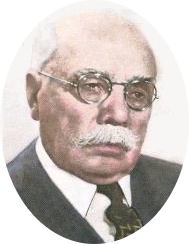

When a 31 year-old Ignaz Schwinn made the decision to leave his native Germany for America in 1891, he was already one of Deutschland’s most accomplished bicycle engineers and the manager of the progressive Heinrich Kleyer factory (which later evolved into the famous Adler Works). His ambitions were a tad too big for the old country, however, and in choosing his next move, he carefully calculated Chicago as the ideal destination.

When a 31 year-old Ignaz Schwinn made the decision to leave his native Germany for America in 1891, he was already one of Deutschland’s most accomplished bicycle engineers and the manager of the progressive Heinrich Kleyer factory (which later evolved into the famous Adler Works). His ambitions were a tad too big for the old country, however, and in choosing his next move, he carefully calculated Chicago as the ideal destination.

This was the Chicago of the Gilded Age, after all—the phoenix that had risen from the Great Fire’s ashes; the fastest growing epicenter of trade, industry, and technology in the U.S.; and a town with a World’s Fair in the works. On a more practical level, Chicago also had (a) a strong community of German immigrants, and (b) a huge share in the budding bicycle craze of the 1890s. New bike manufacturers seemed to be setting up shop in the city every day, with one particularly large enclave on Wabash Avenue earning the name “Bicycle Row.” Companies like the American Cycle Co., Kenwood, St. Nicholas, Gormully & Jeffery, and Monarch were among the many that sold nationally.

To be clear, bicycles (in various incongruent forms) had been around for decades. But improved “safety bike” designs, mass production, and cheaper costs now made them the must-have mode of transport for millions of everyday Americans. The resulting two-wheel gold rush was making some men their fortunes, and crushing others under the weight of competition. As a fresh-off-the-boat arrival, Ignaz Schwinn probably should have been a bit intimidated by this hectic scene, but if he was, he sure didn’t show any signs of it.

[Ignaz Schwinn, his son Frank, and wife Helen; new arrivals to Chicago in the 1890s]

[Ignaz Schwinn, his son Frank, and wife Helen; new arrivals to Chicago in the 1890s]

During the World’s Fair summer of 1893 and on through the nationwide economic depression of the two years that followed, Ignaz effectively grabbed the bike industry by its handlebars. First, he worked his way up to the role of superintendent with the Fowler Cycle MFG Co. (previously known as Hill & Moffat), a large and profitable enterprise. From there, he became the lead designer for the International Manufacturing Company, which employed a workforce of 150 men in its bike plant. Mr. Schwinn commanded instant respect in these roles, and left his imprint in a hurry. But he was far from satisfied. Working for other men’s companies was always going to mean compromising some aspect of his own vision.

And so, despite the rough economy and clear warning signs that the bicycle bubble was doomed to burst, Ignaz made his big move. He found himself a business partner—a well connected moneyman from the meat packing industry named Adolph Arnold [pictured]—and together they launched a new company in 1895 called Arnold, Schwinn & Co.

And so, despite the rough economy and clear warning signs that the bicycle bubble was doomed to burst, Ignaz made his big move. He found himself a business partner—a well connected moneyman from the meat packing industry named Adolph Arnold [pictured]—and together they launched a new company in 1895 called Arnold, Schwinn & Co.

Right from the beginning, Schwinn and Arnold set the goal of producing a bicycle of undeniably superior design; something that would separate itself from the sea of cheap ramshackle models flooding the market. They saw no point in being humble about this effort, either. The company branded its product the “World” bicycle, and loaded its early catalogs with flowery language of international conquest.

“The cycling public now, more than ever before, appreciates the degree of perfection in designs, mechanical skill, materials and workmanship necessary in the production of an up-to-date modern bicycle,” claimed the 1897 Schwinn catalog. “The season of 1897 finds ‘World’ bicycles in undisputed possession of an established and recognized reputation for true worth, superiority, and perfection of modern cycle construction, judgment having been passed by a most critical and exacting cycling public from Klondike’s glacial realms to South America’s Horn; from Iceland’s icy shores to Africa’s end of Hope; from Siberia’s snowy fields over China’s Wall of Stone; under Japan’s balmy skies to the Land of the Kangaroo—North, South, East and West, wherever man may roam, ‘WORLD Cycles’ have found a home and are synonym with BEST.”

I can’t speak to Schwinn’s reputation across the Seven Seas, but the business was certainly making dough on its home continent. Even when the national bike boom reached its inevitable end around the turn of the century (with help from the new automobile craze), Ignaz Schwinn was able to navigate the obstacle course deftly, pushing forward while most of his competitors sunk into obscurity. Into the smog of the combustion engine era, Arnold, Schwinn & Co. pedaled on.

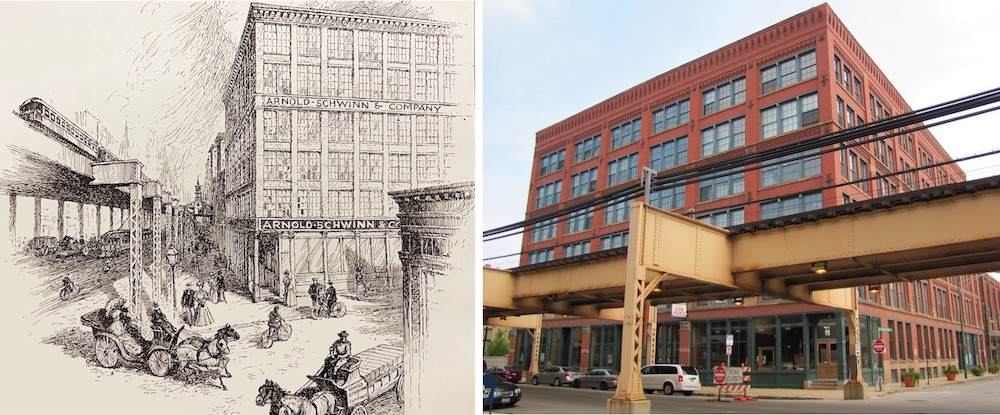

[The original Schwinn factory (1895-1900), at the corner of Lake Street and Peoria Street, is still standing today as the “Lake Street Lofts”]

[The original Schwinn factory (1895-1900), at the corner of Lake Street and Peoria Street, is still standing today as the “Lake Street Lofts”]

II. Schwinn For the Win

Schwinn did tinker with the idea of manufacturing cars—many early automakers were converted bike and carriage builders—but he eventually expanded into motorcycles instead, leading the Excelsior and Henderson brands into a brief rivalry with Harley-Davidson and Indian.

Schwinn did tinker with the idea of manufacturing cars—many early automakers were converted bike and carriage builders—but he eventually expanded into motorcycles instead, leading the Excelsior and Henderson brands into a brief rivalry with Harley-Davidson and Indian.

At the same time, Ignaz worked out increasingly fruitful bicycle distribution deals with various department stores and mail order giants like Sears Roebuck, spreading the cult of Schwinn from the big cities to small rural towns.

Adolph Arnold had certainly played a vital role in indoctrinating Ignaz into the cutthroat world of frontier capitalism, but come 1908, a helping hand was no longer required. Schwinn bought out Arnold’s share of the company, installing himself as the sole master and commander of the business (although he did keep the Arnold, Schwinn & Co. name in use for decades afterward).

[Ignaz Schwinn, left, and his son Frank., in 1916]

[Ignaz Schwinn, left, and his son Frank., in 1916]

By 1914, Schwinn was the largest bike-maker on earth, and claimed more than a quarter of all the bicycles produced in the United States. That same year, an issue of the labor magazine The Metal Polisher, Buffer & Plater described the fast-rising cycle mogul Ignaz Schwinn in glowing terms:

“Mr Schwinn is a remarkable man in more ways than one. He is small in stature, being less than 5-1/2 feet tall, but every pore exudes energy. He handles every detail of his immense business, having no superintendent in either factory, and although rated many times a millionaire, has no use for the frills of society, finding his enjoyment in work. Although past 50 years of age, he has the vitality and energy of a man of 30; you can find him at the bicycle factory as early as 8 a.m. and at the motorcycle plant after the workmen have gone home. Mr. Schwinn has always employed our members in both factories, having signed agreements with Local 6. He is a radical opponent of the exploitation of both child and female labor.”

[Frame builders in the Schwinn plant, 1916]

[Frame builders in the Schwinn plant, 1916]

Indeed, even during the company’s early years, when child labor was the norm in Chicago factories, Schwinn didn’t much subscribe to the idea. In 1895, the report of the Factory Inspector of Illinois lists 60 workers employed at the original six-story Schwinn plant at Lake Street and Peoria Street. All of them were male, and only two were under the age of 16. Ten years later, Schwinn had relocated to its more familiar West Side home at 1718 N. Kildare Avenue, and the workforce had expanded by 100. But the breakdown was quite similar: 160 adult men, 9 teen boys, and just one woman.

Along with the inescapable masculinity of this operation, there was also an intensity and pressure that came with maintaining an impossibly high standard of quality. Schwinn bikes were pricier than a lot of the other brands on the market, but “German engineering” was a popular selling point then as it is today, and that reputation was vital to the business. Even as the Kildare plant repeatedly expanded and improved its efficiency with modern machinery and mass-produced parts, there was still a certain expectation that every Schwinn bike would be “hand-crafted” and fine-tuned by highly trained human beings. A Schwinn wasn’t a Schwinn until Mr. Schwinn said it was a Schwinn.

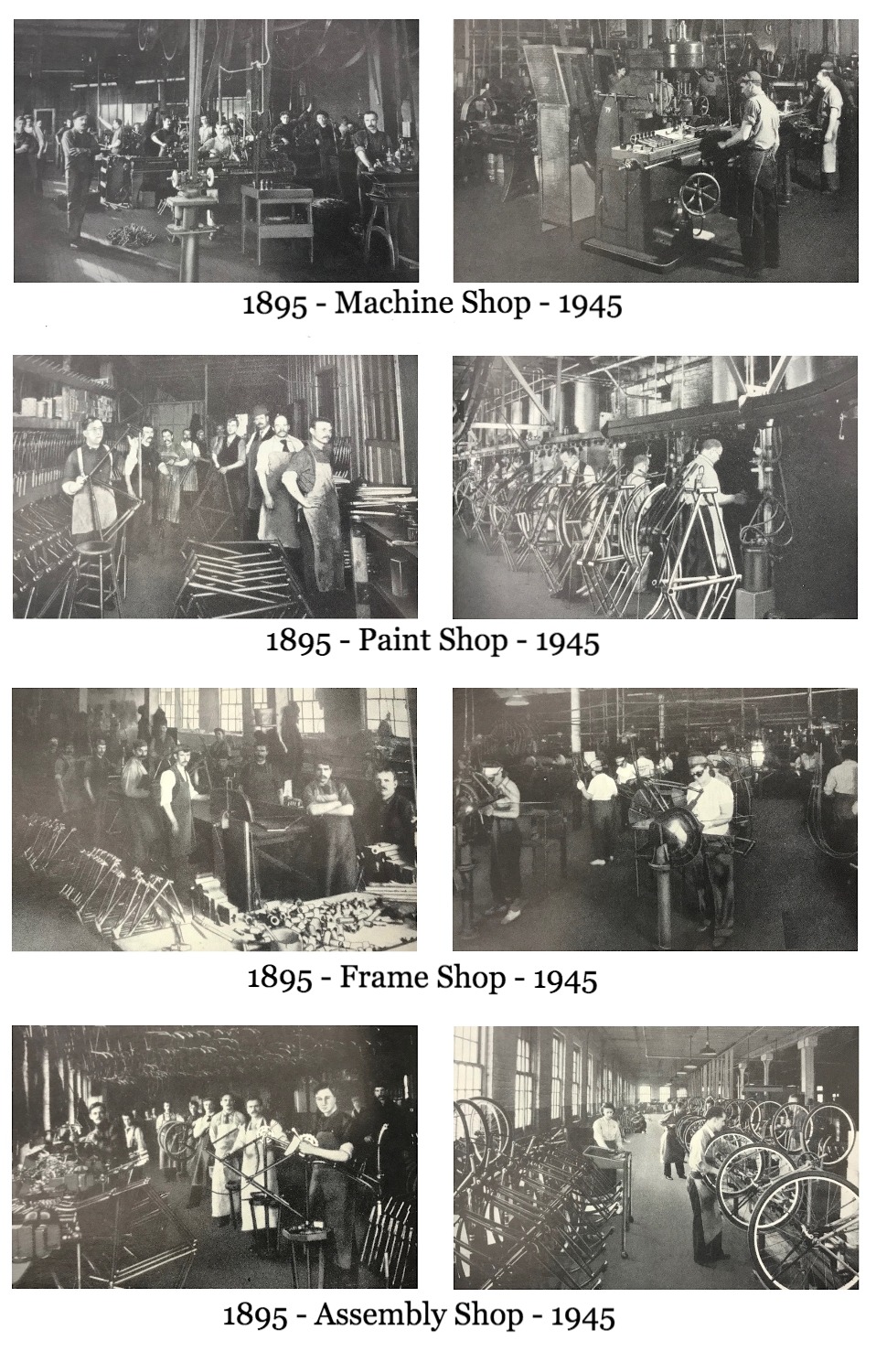

Schwinn Factory Workers: 1895 vs. 1945

III. In Times of Conflict

For as much as Ignaz Schwinn stuck to his stereotypically German principles, his company mainly succeeded because of how it rolled with unexpected punches. Sometimes, that meant having to make some painful sacrifices, like putting that aforementioned German heritage on the back burner.

Schwinn had spent his half his life in Germany, but when the U.S. entered World War I in 1917, he aligned himself with his adopted homeland, turning the Kildare plant over to the needs of the American government for the next two years. The same scenario played out again from 1942-1945, and with many of the 1,000+ Schwinn employees fighting overseas, the company modernized its views on female workers, as well, with hundreds of women taking on major roles during the war years, building machines (including bikes) for the army.

[Schwinn’s primary Chicago complex at 1718-1740 N. Kildare Ave., pictured above in 1940, stopped commercial production to make military bikes and other equipment for the U.S. Government during World War I and World War II]

[Schwinn’s primary Chicago complex at 1718-1740 N. Kildare Ave., pictured above in 1940, stopped commercial production to make military bikes and other equipment for the U.S. Government during World War I and World War II]

Many German business owners in the U.S. faced considerable scrutiny and sales losses as anti-German sentiment spread during both World Wars. To compensate, some went the extra mile to flag wave and prove their American patriotism. Schwinn used a slightly more subtle approach. Having made their fame on the “WORLD” bicycle, they weren’t going to try to pass themselves off as nationalists. They would, however, make a point of celebrating the “Made in the USA” aspect of the brand above the “German engineering” element. Careful effort was also made to include plenty of wholesome “All-American” athletes, film stars, and other celebrities as Schwinn endorsers.

Bing Crosby and his four sailor-suited sons show up in the 1941 catalog (along with “Glamour Girl” Rita Hayworth), and when the next edition came out after the war in 1946, Roy Rogers, Joan Crawford, Bob Hope, Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, and a young actor named Ronald Reagan all saddled up for photo shoots. It’s no coincidence that the first “Hollywood” bike for girls debuted during this same era.

[The Schwinn “American” bike pledged allegiance, while Hollywood stars Ronald Reagan and his first wife, Jane Wyman, vouched for the brand in the 1946 Schwinn catalog]

[The Schwinn “American” bike pledged allegiance, while Hollywood stars Ronald Reagan and his first wife, Jane Wyman, vouched for the brand in the 1946 Schwinn catalog]

Schwinn certainly handled the challenges of wartime admirably, but it was actually the years between the wars that really secured the company’s future and its place at the top of its industry.

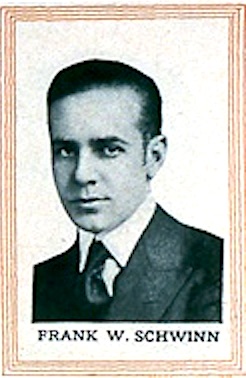

During the Roaring ‘20s, motorcycle production had helped buoy the company as bicycle sales slumped across the board (adults wanted horsepower, and bikes were for kids). After the stock market crash of 1929, however, Ignaz took drastic action, selling off the motorcycle division and focusing on a return to the company’s roots. In 1931, a now 71 year-old Ignaz also handed over most of the day-to-day concerns of the company to his vice president and firstborn son, Frank (F. W.) Schwinn, who’d been training under his wing at the Kildare plant since 1918 (notably, Papa Schwinn did NOT surrender the title of company president).

To get through the Great Depression, Arnold, Schwinn & Co. basically looked to the same playbook that had helped them survive the challenges of 1895—new blood, fresh ideas, and superior designs. Fortunately, the next generation was up to the challenge.

[One of the first “Hollywood” bikes for girls, from the 1939 Schwinn catalog]

[One of the first “Hollywood” bikes for girls, from the 1939 Schwinn catalog]

IV. Frank Schwinn Saved Schwinn, Frankly

Like his dad, F. W. Schwinn did not seem hampered by a lack of ambition, nor was he content to sit back and let the world famous family business rest on its laurels. With the semi-retired Ignaz Schwinn still keeping a close watch on things, Frank made some bold decisions that helped launch a second golden age not only for the Schwinn company, but the bike industry as a whole.

Like his dad, F. W. Schwinn did not seem hampered by a lack of ambition, nor was he content to sit back and let the world famous family business rest on its laurels. With the semi-retired Ignaz Schwinn still keeping a close watch on things, Frank made some bold decisions that helped launch a second golden age not only for the Schwinn company, but the bike industry as a whole.

First of all, while other Depression-era manufacturers were understandably using cheaper components and increasingly marketing bicycles as “toys”—Schwinn actually went the opposite direction. The company stopped dealing with department stores and worked exclusively with proper bicycle retailers—such as Barnard’s or the Chicago Cycle Supply Company. This helped develop a legion of loyal dealers and customers, all of whom appreciated Schwinn’s focus on quality above quantity. Frank also threatened to start importing parts from Europe if U.S. suppliers didn’t raise their own quality standards, and the tactic worked—the parts remained domestic, but far superior to what most bike companies were using.

Maybe the biggest Schwinn innovation of the 1930s was the introduction of the larger balloon tire—originally used by German manufacturers for rough cobblestone streets. It created a whole new riding experience, and—combined with elaborately decorated new chain guards and colorways—caught the attention of a whole new generation.

Ornamental metal head badges were another increasingly useful attention grabber, not just distinguishing different brands and models from one another, but functioning as a status symbol—like the hood ornament on a luxury car. Schwinn’s badge designers really went all out, and our Made In Chicago collection includes a slick example, the “Majestic,” which would have fastened to the front bar of a bike of the same name in the 1940s.

Ornamental metal head badges were another increasingly useful attention grabber, not just distinguishing different brands and models from one another, but functioning as a status symbol—like the hood ornament on a luxury car. Schwinn’s badge designers really went all out, and our Made In Chicago collection includes a slick example, the “Majestic,” which would have fastened to the front bar of a bike of the same name in the 1940s.

In all, Frank Schwinn added roughly 40 new patents to the company’s arsenal. In the darkest of economic times, he’d managed to make “adult bikes” appealing again while also opening up a whole new class of high end bikes for kids—all backed by a then unheard-of “lifetime guarantee” of quality.

V. “Courage, Diligence and Industry”

By the time of the company’s 50th Anniversary in 1945, Ignaz Schwinn—now in his 80s—still made a point of visiting the factory almost every day, making sure everyone from the machinists and welders to the assemblers and painters were upholding that original Schwinn “World” vision. The company’s official anniversary book, 50 Years of Schwinn Built Bicycles, described Ignaz as a business leader who “helped to build America . . . one of the men who leaped into the breach and provided work for his fellow man.

“Of his many endeavors, there is none finer than that which brought to so many thousands the opportunity to help themselves along their way through life by fabricating the materials he needed, selling the product he manufactured or gaining a livelihood in his employment. The quality of the leadership, which made Arnold, Schwinn & Company, is its very lifeblood. The example of courage, diligence and industry which Ignaz Schwinn has for so many years lived for his organization, will carry on. It will not be forgotten.”

“Of his many endeavors, there is none finer than that which brought to so many thousands the opportunity to help themselves along their way through life by fabricating the materials he needed, selling the product he manufactured or gaining a livelihood in his employment. The quality of the leadership, which made Arnold, Schwinn & Company, is its very lifeblood. The example of courage, diligence and industry which Ignaz Schwinn has for so many years lived for his organization, will carry on. It will not be forgotten.”

Schwinn died in 1948 at the age of 88, and was buried at Rosehill Cemetery.

Afterward, F. W. Schwinn finally became the company president in an official capacity (he’d been handling the responsibilities for years), and the business carried on smoothly into its postwar glory days—the hands-free, coasting period mentioned earlier. Boys and girls, men and women, racers and casual riders . . . everyone had a Schwinn designed for their needs, and a colorful marketing campaign to go with it.

Schwinn never played it conservative with their ad budget, but their best sales agents were always their customers. Popular mid-century models like the Streamline Aerocycle, the AutoCycle, the Continental, Panther, Jaguar, Hornet, Black Phantom, and Sting-Ray all generated word-of-mouth buzz at bike shops, playgrounds, offices, etc. The Chicago factory was basically producing the bicycle equivalent of the Mustangs and T-Birds coming out of Detroit, and the biggest challenge was just keeping up with demand.

According to the Encyclopedia of Chicago, Schwinn’s sales hit $20 million by 1961, and by 1968—prime “Wonder Years” times—they were producing one million bikes a year and were back to employing well over 1,000 Chicago workers at the Kildare and Kostner Avenue plants. All seemed rosy, but like the last weeks of a summer holiday, colder breezes were moving in.

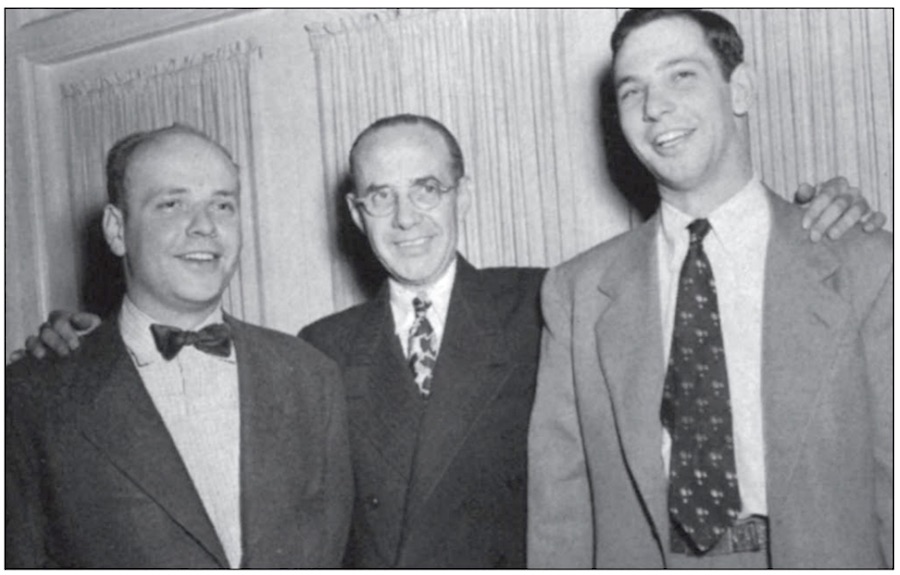

[F.W. Schwinn, center, with sons Edward Schwinn Sr. (left) and Frank V. Schwinn, late 1940s]

[F.W. Schwinn, center, with sons Edward Schwinn Sr. (left) and Frank V. Schwinn, late 1940s]

VI. Bad Brakes

For years, F. W. Schwinn had been preparing to hand the leadership of the family business to his eldest son, but when Edward Schwinn died tragically of leukemia at age 48 in 1972, those plans—and the course of the company—changed.

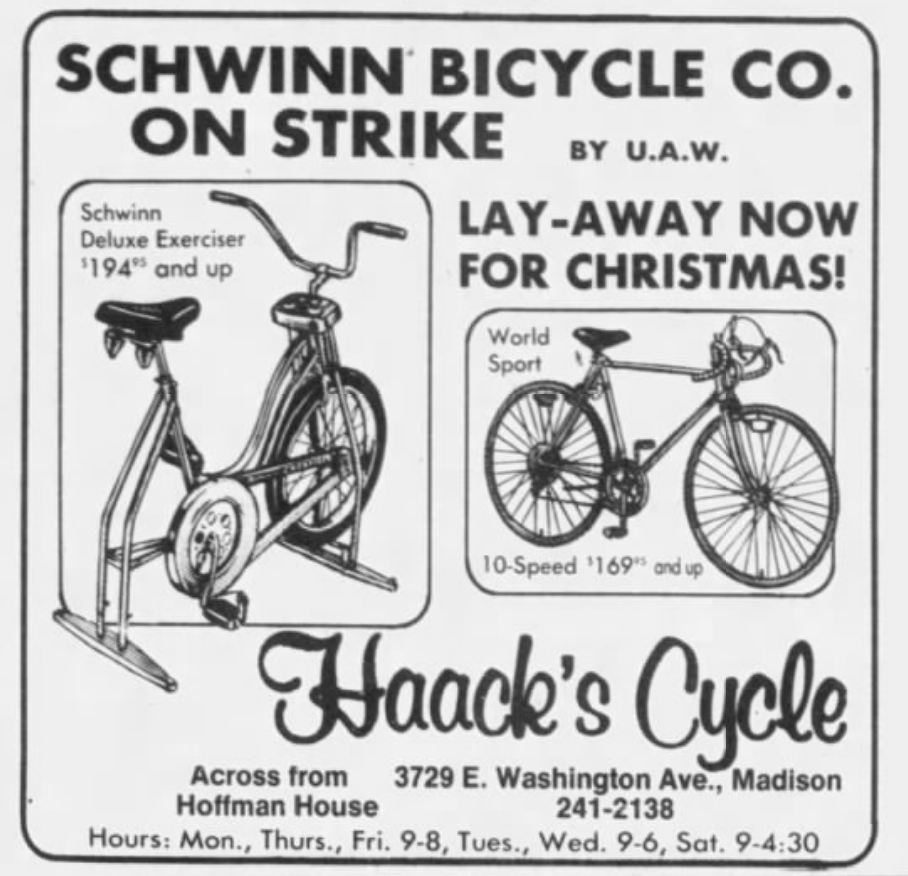

The next president was instead a younger son, Frank V. Schwinn, and while he’d certainly grown up immersed in the business of bikes, he didn’t seemed to have the foresight and ingenuity on the topic that his father and grandfather had. Frank V. tried to stay true to the Schwinn law of quality over quantity, but in a rapidly changing marketplace, his inability to upgrade manufacturing facilities or anticipate new trends gradually slowed the company’s development. His successor, fourth generation owner Edward Schwinn, Jr. (a nephew) was no improvement. Not only did Schwinn fail to catch wind of the mountain bike revolution in the ’70s and BMX in the ‘80s, but they also suffered unprecedented labor disputes under Edward’s watch, culminating in 1,400 workers walking out for a 13-week strike in 1980. It was the first picket line in the company’s history, and a death blow to Schwinn’s 85 year relationship with Chicago.

Insult upon injury, Schwinn had gradually become a stale brand in the eyes of the youth market during the same period. Rather than begging their parents for Schwinns at Christmas, young bike enthusiasts scoffed at these old-fashioned “grandpa bikes.” Schwinn went from the class of the industry to hopelessly “uncool.” They had become trapped inside their own mythology.

Insult upon injury, Schwinn had gradually become a stale brand in the eyes of the youth market during the same period. Rather than begging their parents for Schwinns at Christmas, young bike enthusiasts scoffed at these old-fashioned “grandpa bikes.” Schwinn went from the class of the industry to hopelessly “uncool.” They had become trapped inside their own mythology.

The company finally abandoned Chicago in 1982, laying off 1,800 workers and relocating to a plant in Greenville, Mississippi. About a decade later, still reeling from foreign competition, the business went bankrupt.

The once sprawling Kildare Avenue factory was set to be torn down by 1985, but the job was largely handled prematurely by a suspected arsonist’s fire in the empty complex in August of 1984. The vacant lot left in its wake remained an eyesore in Hermosa for 20 years before finally becoming the home of the new North-Grand High School in 2004. Meanwhile, the former Schwinn assembly plant and office building at the neighboring address of 1856 N. Kostner Avenue managed to avoid both the blaze and the wrecking ball, and is still standing today.

[The former Schwinn facility at 1856 N. Kostner Ave. is still standing as of 2021.]

[The former Schwinn facility at 1856 N. Kostner Ave. is still standing as of 2021.]

After filing for bankruptcy in the ‘90s, Schwinn was passed along a succession of new owners, eventually hitting bankruptcy again by 2001. It was then purchased at auction by Pacific Cycle, Inc.—a company that made its own fortune selling cheaply made bikes imported from China and Taiwan. Naturally, the new breed of so-called Schwinns are produced in the same fashion.

Pacific Cycle is owned by a Canadian conglomerate called Dorel Industries, and both entities seem to at least partially understand the lasting appeal of the Schwinn brand. The contemporary designs routinely make reference to the familiar Schwinn models of yesteryear, and there have even been re-introductions of beloved icons like the Sting-Ray. Looks can be deceiving, however.

The real Schwinn bikes—the genuine article, Chicago built—are only available in vintage shops like Barnards. Anything else, as they say, “ain’t made like that anymore.”

SOURCES:

Schwinn Bicycles, by Jay Pridmore and Jim Hurd

50 Years of Schwinn-Built Bicycles, 1945

“The World Is Mine” – 1897 Schwinn Catalog

Museum of Mountain Bike Art and Technology

No Hands: The Rise and Fall of the Schwinn Bicycle Company, by Judith Crown & Glenn Coleman

“Arnold, Schwinn & Co” – Encyclopedia of Chicago

Clockspeed: Winning Industry Control In The Age Of Temporary Advantage, by Charles H. Fine

“Arson Suspected in Fire at Former Schwin Factory” – Chicago Tribune, August 24, 1984

Archived Reader Comments

“First of all: Thanks for all your hard work putting together this wonderful resource! I never owned a Schwinn, but certainly rode many of my friends’ Schwinns growing up. The Stingray was all the rage right around the time I got my first bike, with it’s “banana seat” and high rise handle bars (“are those safe”, my mom wondered!). As a little kid your bike was your ticket to “freedom”, not having to walk everywhere finally. Parents were “cooler” in the 60’s and 70’s: They turned us loose, more or less, and we just went as far as we dared explore on our bikes. They didn’t try to be in control constantly or try to do everything for us like today’s parents (of which, I confess, I am one). I will admit, however, that my Admiral-employed dad made a helluva science project for me in 2nd grade. So yeah, that was one time he took over, mostly!” –Paul Garner, 2019

“It is late in both my life and that of a true Schwinn collector ..however.. I lived at 1647 Kildare for 5 years; 1942 till 1947 where my uncle was quality inspector till he retired in 1983 I now have 23 Schwinn tank bikes.. I recently sold my 52 Phantom for 1350.” –Henry Schmidt, 2018

“I was a tooling machinist at the Kostner plant in the mid-1970s and wonder if anyone has any photographs of the inside during production. That plant housed the screw machine and punch press departments, among others. Plating was at Kildare. Last time I was in Chicago, I drove by and noticed that the chromed bicycle silhouette over the office door is still there…” –K.C., 2018

Prior to 2020, I rode the green line ‘el’ west to Ashland Ave, for years going to work. While we stopped at Morgan St. I noticed the ghostly shadow of painted letters at the top of the building at Lake and Peoria. If you look closely you can still make out “World Cycle”, maybe a “Co” on the end, I don’t remember exactly. Back then I researched that company to find that it was the Schwinn Co. from so many years ago. Glad to see it included in your history of such a great Chicago company.

I have a Schwinn Racer JG019892 that is brand new. It was built in 1971 and still has the mold flash on the outside rim of the original tires. I belive it was baught as an investment. I am sure it has less than 10 miles of riding on it. Its a man’s blue with chrome fenders, 3 speed, and hand brakes. Please email fixer11742@gmail.com if interested.

I actually have a brand new 1969 Schwinn Apple Krate I purchased 30 years ago as an investment…

I bought it from a family whose Mom and Dad both worked for schwinn I believe somewhere near downers grove or possibly on Kostner Ave. in Chicago…

I have been purchasing accessories and paperwork for the bike over the last 30 years!

I believe it has great worth and actually willed it to my 2 daughters when I pass….

MY QUESTION: I recently purchased 2 green wheel inspection tags off of eBay….

The seller claimed them to be from the 60/70’s. …. They were so cheap, it was worth the risk!!

Was there ever such a thing?

Thanks in advance….

I rode a Schwinn Voyaguer around the world, 1988- 1990. USA, Iceland Europe, East Europe, USSR (First foreigner ALLOWED, guest, Soviet Peace Committee.) Went on through West china, Xinjiang, up the Karacorum Highway and over Khunjerab Pass. (Now highest Paved highway in the world, under construction back them.) AKA The Silk route. Onward through Pakistan, India, Nepal, Tibet and China. Finished with ride from Nagasaki to Sapporo then Alaska back to my home in California. I have both bikes as well as 40 hours of video and hundreds of photos.

I think my material needs more, Schwinn is now Big Box, no shops.

Now 83, ANY IDEAS for a depository that would display and use? Museum, University OR???

Thanks J. R. ‘Pat’ Patterson (805) 760-3764

worldriders2@yahoo.com

My grandfather, Adam Smith, was the pinstriper for the Paramount bikes that Schwinn made. He worked alongside Frank Schwinn and they hand striped those bikes. I have the brushes he used to stripe them. Very special and nostalgic. It was fun to read the article on the old factory.

What year is my Schwinn Tandem bike serial number T003360

Quality Chicago,

can anyone tell me if this serial number AT30630936 is a authenty swhinn bike,what year was made and model?

im trying to find information my bike, if i send photos can someone help me?

I have a 68 schwinn and want to know more info on it. Call or text me 574-327-5134

My great grandfather Nikolas Majerus worked for Schwinn back in the day. My grandmother’s birth certificate from 1907 shows his occupation as bicycle maker. True history for sure

Nei primi anni 80 sono stato a Chicago , visitato il Museo e negli uffici Shwinn per firmare con altri soci l’accordo di distributori esclusivi per Italia e successivamente per altri Paesi Europei delle MB e City Bike nonchè la linea Fitness , ho conosciuto i vertici della società , Edward presidente è venuto poi in Italia al Salone Moto Bici a Milano dove abbiamo presentato tutta la linea Schwinn Ai grandi appassionati e conoscitori della storia della Schwinn non parve vero poter acquistarne una in Italia . Dopo pochi anni ( potrei scrivere un libro ) è saltato tutto . Possiedo ancora 4 Schwinn tra cui una P90 P70 e P50

Gioielli

In my second year as a business student in Moorhead Minnesota in 1977 I did a marketing project on the retail bicycle industry. I wrote the Schwinn company requesting information from their perspective and they generously sent me a packet of data on the then current market. Sadly, their data indicated a saturated adult bicycle market, with the ‘English’ style racer and the upright casual/touring style as the only styles available. It was shortly after that the mountain bike craze spread from California, to Colorado and then Minnesota by 1980’s. Sadly again, the Schwinn company seemed to have been asleep (or in death throes!) and failed to capitalize on this exciting and rejuvenating development. Since then, innovations in materials, geometry, mechanics, a general opening up of communities to bicycle friendly streets and a renewed interest in personal health and environmental awareness have combined to bring the bicycle back into popularity! I’m loving it!!

I have dark blue coed Chicago made it’s old I don’t know where to find serial numbers

i have a schwinn woman traveier serial no. d897187 i looked it up on schwinn serial no. site it shows built in 5-1-1958 but i can only find 1957 and 1959 no 1958 and it has 27 in. wheels can any one help me on this 727 641 6122

Have a continental2 circa 1970sall original parts is it something your interested in

Would you be interested in buying my 1973 paramount road racing Schwinn with campagnolo 50th anniversary groupo? If interest I can send photos. Gary gray 3193666337 and speedee303@gmail.com

Excellent article on Schwinn’s history. There is more information about Schwinn and its last Chicago incarnations available here: https://sheldonbrown.com/chicago-schwinns.html There are included links to further information about Schwinn’s manyfacturing technology at this site. The museum might wish to consider posting these original articles as the author, Mr. Brown is deceased and I would say it’s anyone’s guess how long Harris cyclery, the host site, will continue to offer Mr. Brown’s articles and links.

Hello, I have a 2 pack of circa 1970 Schwinn Bridge playing cards in a leather case with a pen. The item is in pristine condition and the card boxes are still plastic wrapped. I haven’t been able to find anything like them online. Not sure who would be interesting in this item.

Looking for Opaque green paint , restoring schwinn 1972 super sport

I have a bicycle that looks a lot like a vintage Schwinn . Late 30S to. 40 . The badge on the front says Varsity.

Do you have any idea what it may be.

Also has a Ford Motor Co. Tag on it.

I am buying a headbadge for my circa 1957 Schwinn Spitfire. The ad says it’s genuine Schwinn, metal, never used and that Schwinn remade them in 1998. Is that true? Did Schwinn remake them in 1998?

Many parts were sold in 98 as well as the 100th anniversary edition Schwinn Classic Cruiser basically a reproduction post war Black Phantom fully equipped with tank w/ horn in it. Chrome springer forks cantilevered frame spring seat balloon whitewall tires and Book rack.

My mother who just passed away and gave me her old Schwinn winner Delia woman’s bike powder blue .. not sure what year it is ? 40s or 50s.. could you tell me if they have value or are rare ?

can anyone tell me the year my bike was made with serial number H345784