Museum Artifact: Eye-Lash-Ine Eyelash Remedy Tin, 1920s

Made By: Dr. F. Formaneck Company, 1333 S. California Ave., Chicago, IL [North Lawndale]

“The Beauty, Charm and Soulful Expression of the Eyes can be brought out to the Very Best Advantage with Long, Luxurious Eyelashes. EYE-LASH-INE grows eyelashes and relieves granulated eyelids. At druggists, barber, and beauty shops or by mail upon receipt of 50 cents.” –-Dr. F. Formaneck Co. advertisement, 1923

Unlike most of the patent medicine peddlers at the turn of the century, Fred Formaneck was a proper, bonafide medical doctor—and not a small-time one at that. A former attending surgeon for Cook County Hospital and the Chicago Police Department, the Wisconsin-born Formaneck was also a vocal leader in the Bohemian-American community from which he came, often giving speeches in the Czech language at Bohemian meeting halls throughout the Midwest, usually to rally support for the Republican Party. His efforts made enough ripples that even President Theodore Roosevelt took notice in the lead-up to the 1904 election.

Unlike most of the patent medicine peddlers at the turn of the century, Fred Formaneck was a proper, bonafide medical doctor—and not a small-time one at that. A former attending surgeon for Cook County Hospital and the Chicago Police Department, the Wisconsin-born Formaneck was also a vocal leader in the Bohemian-American community from which he came, often giving speeches in the Czech language at Bohemian meeting halls throughout the Midwest, usually to rally support for the Republican Party. His efforts made enough ripples that even President Theodore Roosevelt took notice in the lead-up to the 1904 election.

“I want you particularly to see Dr. Formaneck,” Roosevelt wrote in a letter that April to the secretary of the Republican National Committee, Elmer Dover. “I feel he would be of immense assistance among the Bohemians, perhaps especially in Illinois, but also elsewhere throughout the country.”

Roosevelt went on to describe the 42 year-old Formaneck in rather glowing terms, unwittingly leaving the doctor a rather priceless and permanent testimonial (thanks to the TR archives). “Dr. Formaneck is a man of means and high standing, who wants nothing from us, who has been of great service in the past,” Teddy informed Dover. “And though his business is such that he can not spend as much time for us this year, he is yet willing to spend some time to supervise the translation of documents into Bohemian, and give his advice as to what documents should be translated; and he would also furnish Bohemian speakers, etc.”

Remarkably, Roosevelt even seems to be aware of Formaneck’s increased personal workload in 1904—a direct result, no doubt, of the establishment of the Dr. F. Formaneck Company a year earlier.

[President Theodore Roosevelt, gushing over his admiration for the Chicago doctor Frederick Formaneck in 1904]

History of the Dr. F. Formaneck Company

Long before the President of the United States started name-dropping him, Frederick Formaneck looked like a long shot to ever get noticed by anybody. Born in Muscoda, Wisconsin, in 1862, he was the tenth of eleven kids raised by humble farmers Albert and Anna Formaneck, immigrants from Zaluzany, Bohemia, or what would now be the Czech Republic. When Fred was 10 years old, the family relocated via wagon train to new farmland in the Dakota Territory, near present day Wahpeton, North Dakota. Despite the harsh conditions, the Formanecks clearly did something right. Not only did they manage to send one of their sons off to earn a medical degree from Chicago’s Rush Medical College (Fred graduated tenth in his class in 1887), but in a time when the average life expectancy was around 47, just about every member of the large Formaneck family lived into their 70s. Both of Fred’s parents and five of his siblings ultimately reached their 80s.

That kind of health and longevity might actually lend some credence to the legitimacy of Dr. Formaneck’s own medicinal concoctions, some of which were supposedly inspired by old Bohemian remedies. Unfortunately—as is so often the case with these types of businesses—we’ll never know for sure if Fred was a true believer in his products or a mere opportunist, cynically motivated to cash in on the profitable pharmaceutical trends of his era.

That kind of health and longevity might actually lend some credence to the legitimacy of Dr. Formaneck’s own medicinal concoctions, some of which were supposedly inspired by old Bohemian remedies. Unfortunately—as is so often the case with these types of businesses—we’ll never know for sure if Fred was a true believer in his products or a mere opportunist, cynically motivated to cash in on the profitable pharmaceutical trends of his era.

This was the golden age of patent medicines in America, after all, just before the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 introduced the first meager attempts at regulating the industry. As a young, practicing Chicago surgeon with a prominent downtown office, Fred Formaneck would certainly have been aware of the popularity of patent medicines and the many Chicago businesses involved in their manufacture. He would also have understood the ongoing battle between the serious medical establishment and the promoters of “quackery,” or unproven (usually bogus) drugs. From early in his career, though, Fred seemed intrigued by the idea of playing both sides.

In 1893, during the famed summer of the Columbian Exposition, Formaneck established a business he called the Preventine Chemical Company, organized for the purpose of manufacturing medicines. This enterprise suggests that Formaneck was already interested, relatively early in his medical career, with dispensing his own drugs—a smart solution for cutting out the middleman, if nothing else. During the same period, as his status grew through his work with Cook County Hospital and the Chicago PD, he was also establishing his reputation as an opinionated and influential figure, never shy about involving himself in any health-related issue.

“The catarrh (phlegm) that is so prevalent in Chicago is largely due to the foreign matter that is in the air,” Formaneck wrote to the Inter Ocean newspaper in 1891, speaking out against the air pollution of the relatively new industrial boom. “That the death rate would be greatly lessened if the smoke nuisance could be abolished I have no doubt. In a few weeks la grippe will make its appearance in the city, and its effect will be particularly fatal because of the fact that so many systems have been weakened and diseased by the soot and smoke that have been taken into the lungs.”

Another fairly progressive position could be found in Formaneck’s views on pet care. When his pet terrier Patsy went missing from his Pilsen home in 1894, Fred placed an ad in the Chicago Tribune describing the pooch as having, among other things, a “gold-capped tooth.” This had the unintended consequence of sending half the boys in Pilsen on a mad hunt for the dog, for all the wrong reasons, but fortunately Patsy was returned in one piece, and Dr. Formaneck was subsequently asked to explain the gold tooth situation to curious Tribune readers.

“I have seen dogs with filled teeth before,” he said, “but rarely. In cases where dogs are of great value and the teeth are decaying the animal is sometimes taken to the dentist and operated on. . . . Patsy’s gold-filled tooth is an ornament. It shines and glistens whenever his mouth is opened. And Patsy seems to take a great deal of pride in showing that gold cap.”

“I have seen dogs with filled teeth before,” he said, “but rarely. In cases where dogs are of great value and the teeth are decaying the animal is sometimes taken to the dentist and operated on. . . . Patsy’s gold-filled tooth is an ornament. It shines and glistens whenever his mouth is opened. And Patsy seems to take a great deal of pride in showing that gold cap.”

Formaneck might not have been fully in touch with the working class by this point, but he did hold a particular position of borderline celebrity within Chicago’s Bohemian community, parlaying his unique success as a surgeon and druggist into a growing role as a vocal supporter of Republican Party politics. Having a soap box among Chicago’s Czech speakers wasn’t as niche a position as one might think, either. For context, as the Encyclopedia of Chicago explains it, “Chicago was the third-largest Czech city in the world by 1900, after Prague and Vienna. In addition to their local concentration, Chicago Czechs lived at the center of a network of Midwestern Czech communities, including significant populations in Ohio, Iowa, Wisconsin, Nebraska, Minnesota, and Missouri.”

To complicate matters, the Czech population was also a divided one, split between old-school Catholics and new-school “freethinkers,” the latter of which more likely included Dr. Formaneck. No less than four Czech-language newspapers circulated in Chicago alone—each catering to a slightly different subset of these belief systems among the 100,000 Czechs in the city. In 1896, one of those papers even put Dr. Formaneck in its crosshairs, accusing the doctor of “inhumanity” and “receiving money under false pretenses.” Formaneck, in turn, sued the publishers for libel.

[People dancing at a Bohemian party in Chicago, 1910. Photographed by Lewis W. Hine]

Whatever conflicts, criticisms, and controversies hounded him, Dr. Formaneck entered the 20th century largely unscathed and well equipped to turn his new Dr. F. Formaneck Company into Chicago’s latest patent medicine producer extraordinaire; complete with a tip of the cap from the popular Republican president.

From 1903 forward, though, the Dr. F. Formaneck Co. almost exclusively advertised in Bohemian newspapers across the Midwest, rarely making attempts to cross over into a larger mainstream audience. This supports the idea that Formaneck’s products were, indeed, rooted in familiar Bohemian medicine traditions, even if the concepts—i.e., hair tonics, kidney and liver remedies, blood purifiers, etc.—were essentially no different than those in the catalogs of other Chicago patent med dealers like Foley & Co. or E.C. Dewitt’s.

The Formaneck factory/office was located at 1333 S. California Ave, a building which served a more front-facing purpose as the “Bohemian Hospital,” a small ten-bed housing facility in which Dr. Fred Formaneck continued to serve as the head physician into the 1920s.

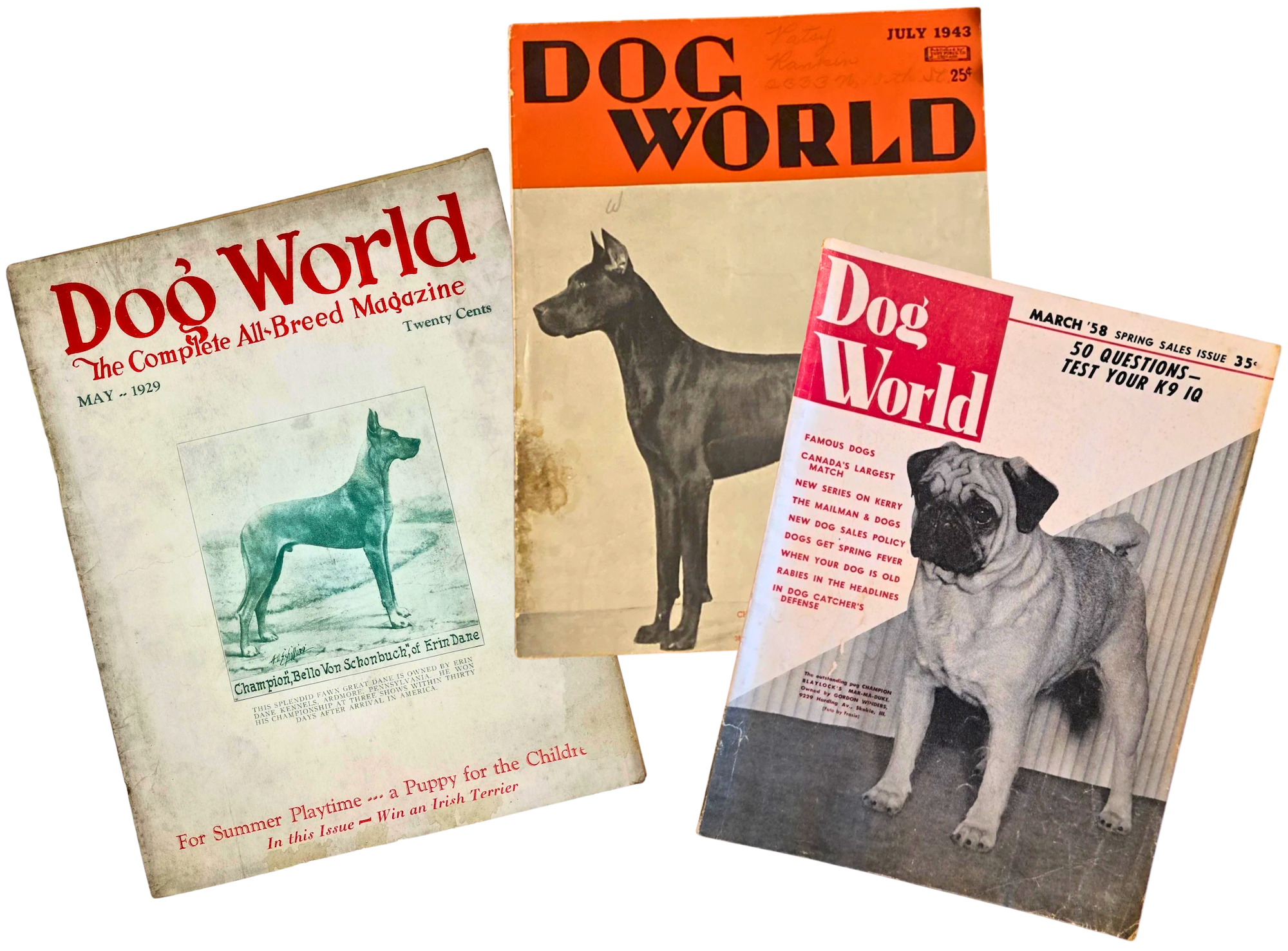

Formaneck and his wife Eugenia never had children, and perhaps as a consequence, they continued pursuing new projects and taking on more responsibilities. In 1916, at the age of 54, Fred channeled his previously established reverence for canines into the establishment of a new magazine, Dog World, which he personally edited and financed through his own independent publishing company, the Dog World Publishing Co. of Oak Park. Formaneck and his wife ran Dog World for seven years before selling the magazine to new ownership in 1923. It remained in publication until 2012.

Dog World was almost certainly Fred Formaneck’s most prominent contribution to a national audience, but if there was a runner-up in those rankings, it would probably be the Eye-Lash-Ine product featured in our museum collection, which was copyrighted in 1916 and put into production in fantastic lithographed tins some time in the early 1920s. Eye-Lash-Ine was almost certainly an attempt to cash in on the success of “Lash-Brow-Ine,” the precursor to Maybelline mascara and the first product released by Maybelline founder Tom Lyle Williams, a fellow Chicagoan, in 1915. Unlike the Maybelline product, though, Eye-Lash-Ine was promoted less as a cosmetic and more as a treatment for the health of the eyelids rather than the hairs poking out of them. Did it work? Unfortunately, nobody who gave it a whirl 100 years ago is around now to confirm.

Dog World was almost certainly Fred Formaneck’s most prominent contribution to a national audience, but if there was a runner-up in those rankings, it would probably be the Eye-Lash-Ine product featured in our museum collection, which was copyrighted in 1916 and put into production in fantastic lithographed tins some time in the early 1920s. Eye-Lash-Ine was almost certainly an attempt to cash in on the success of “Lash-Brow-Ine,” the precursor to Maybelline mascara and the first product released by Maybelline founder Tom Lyle Williams, a fellow Chicagoan, in 1915. Unlike the Maybelline product, though, Eye-Lash-Ine was promoted less as a cosmetic and more as a treatment for the health of the eyelids rather than the hairs poking out of them. Did it work? Unfortunately, nobody who gave it a whirl 100 years ago is around now to confirm.

Formaneck advertised Eye-Lash-Ine (without attaching his own name to it) in mainstream newspapers like the Chicago Tribune and a few others, but only for a short period in 1923.

That brief run makes it somewhat surprising how many of these original tiny tins have survived 100 years later, suggesting that either (a) Formaneck produced a ton of Eye-Lash-Ine with the hopes of having a big success, and/or (b) people who bought Eye-Lash-Ine were more likely to keep the packaging, since it’s quite a nice looking litho design. Whatever the explanation, Eye-Lash-Ine almost immediately failed as a cosmetic product, but lives on as an example of high-minded 1920s aesthetics.

Dr. Fred Formaneck himself carried on with his business and his medical practice through the 1920s. He died in 1935 at the age of 72, leaving an estate of $12,500 to his widow Eugenia. If you factor in inflation, that’s well below $300,000 in 2025 money, and without children included, it suggests the good doctor’s fortune may have been dinged a bit during the Great Depression. Nonetheless, the Formanecks had more than enough scratch left to select a glamorous resting place: the Masonic Mausoleum in Acacia Park Cemetery in Norwood Park.

Sources:

“Dr. Fred Formaneck” – The Inter Ocean, Dec 15, 1891

“Preventine Chemical Company” – Chicago Tribune, May 11, 1893

“Terrier with a Gold Tooth” – Chicago Tribune, March 21, 1894

“Bohemian Editors Not Alarmed, Criticize Libel Suit” – Chicago Chronicle, Jan 14, 1896

“Republican Meeting Tonight” – Cleveland Leader, Nov 2, 1900

“Dr. F. Formaneck Co.” – Illinois Medical Journal, June 1903

“Letter from Theodore Roosevelt to Elmer Dover” – 1904 – TR Center @ Dickinson State

“Czechs and Bohemians” – Encyclopedia of Chicago, 2005

“Words from the Past” – DogNews.com, 2021

“Dr. Frederick Formaneck” – FindaGrave.com

Ah!! Thank you so much for sharing this history! Eye-Lash-Ine comes up for sale frequently but I never investigated it. The tin design is so iconic!