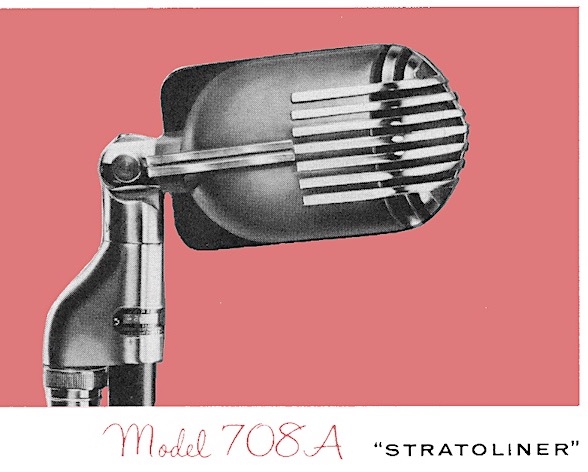

Museum Artifact: Shure 708A Stratoliner Crystal Microphone, 1940s

Made By: Shure Brothers, Inc., 225 West Huron Street, Chicago, IL [River North]

“We know very well that absolute perfection cannot be attained, but we will never stop striving for it.” —Sidney N. Shure, founder of Shure Brothers, Inc.

Introduced in 1940, the “Stratoliner” microphone in our museum collection finds the world famous Shure, Inc., at an interesting crossroads in its history. The electronics manufacturer—then known as the Shure Brothers Company—had only been making so-called “crystal” microphones for five years, and the new streamlined model 708A represented another big step toward the home market; with a simplicity and price tag more suited for casual, amateur use than the professional ranks.

“An expensive-looking crystal microphone at moderate cost,” read a 1941 Shure data sheet for the 708A. “Provides wide-range response for good reproduction of either voice or music. It is designed for public address, home recording and all general purpose use. A special advantage to this microphone is the fact that it can be tilted vertically for omni-directional pickup for group recording.”

“An expensive-looking crystal microphone at moderate cost,” read a 1941 Shure data sheet for the 708A. “Provides wide-range response for good reproduction of either voice or music. It is designed for public address, home recording and all general purpose use. A special advantage to this microphone is the fact that it can be tilted vertically for omni-directional pickup for group recording.”

After just a year in production, though, America’s entry into World War II temporarily halted the Stratoliner’s roll-out, as Shure transformed into a vital contractor for the U.S. military, putting most consumer products on the back burner.

In the end, the potential commercial “setback” of the war actually turned Shure from a well known name into an iconic one; with its arsenal of audio products helping to amplify the voices of presidents and poets, comedians and clergymen, rock stars and rappers. Microphones, wireless tech, tape recording, phonograph pickups, mixers, hearing aids, headphones—just about anything connected to clear sound ultimately landed under the Shure tent.

The company employed over 1,000 local workers at the height of its original Chicago era, before going fully international in the 1960s, then uprooting most manufacturing to Mexico in the ‘80s. Their world headquarters has never strayed far from the region, however, with a current HQ in Niles, IL, and a recently opened sales and marketing office in downtown Chicago (125 S. Clark Street)—just a stone’s throw from where Sidney Shure first started his business in 1925.

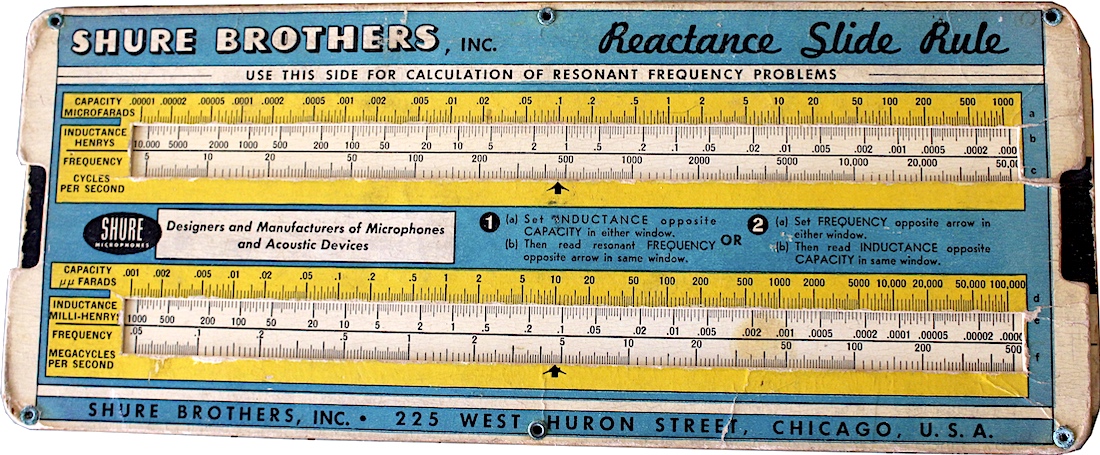

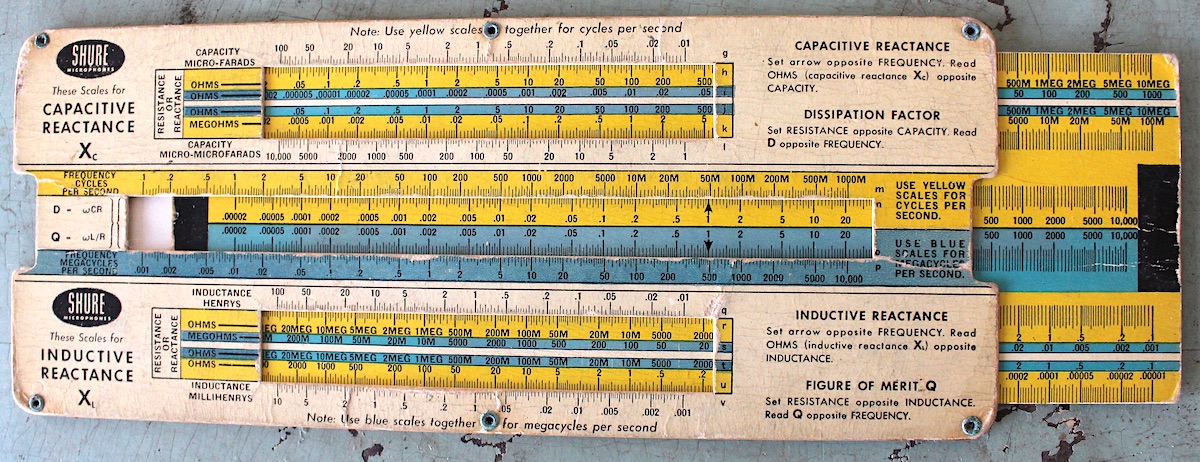

[The Shure Brothers “Reactance Slide Rule” above, dating from the 1940s, is also part of our museum collection]

History of Shure Inc., Part I: Not Your Average HAM

In the age of electrified sound, Sidney Natkin Shure is to the microphone what Les Paul is to the guitar and Laurens Hammond is to the organ. And like those two men, Sidney had Chicago as the perfect habitat for his early innovations.

Shure was born in the city in 1902—the son of Yiddish-speaking Jewish immigrants from Russia—and grew up mostly in the 34th Ward / Far South Side. Like many boys his age, he became fascinated in his teen years with the brand new technology of amateur radio. In contrast with some of his fellow wireless HAM geeks doing battle in Chicago’s “radio gangs,” however, Sidney had considerable resources at his disposal—and a unique appreciation for the delicate balance of supply and demand in a new industry.

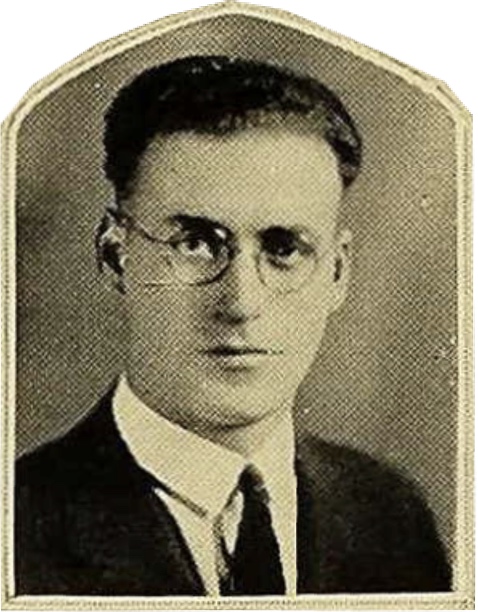

The name Shure, you see, was already widely recognized around town. Sidney’s uncle Nathan Shure was the titular founder of the N. Shure Company (est. 1888)—one of Chicago’s early wholesale mail-order houses—and his father, Mandel Shure, was a longtime executive with the same firm. This not only gave Sidney a firsthand introduction to big business, it also enabled him to indulge his own personal passions with the aid of a financial safety net. As such, he earned a Bachelor of Science from the University of Chicago in 1923, studying geography and taking leading roles in the Commerce Club Finance Committee, Towers Club, Menorah Society, and Cap & Gown Staff. He also went further down the rabbit hole of the radio revolution, devouring all the latest wireless magazines and newsletters and educating himself on the mechanics of the various devices rapidly invading America’s households.

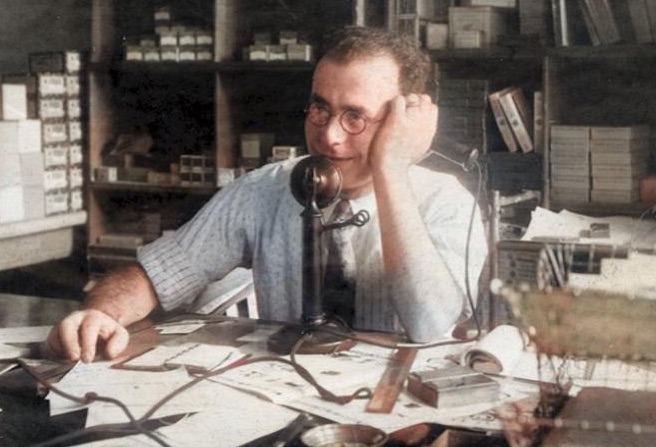

At this early stage, Shure might not have had the technical genius of radio parts makers like Karl Hassel and Ralph Matthews, who were launching their Zenith business on the North Side; nor Ross Siragusa, the teenage wunderkind who started his first company (soon to be known as Admiral Corp.) on the West Side in 1924. Coming from a family of modern marketing experts, though, Sidney was able to quickly turn his hobby into a profitable enterprise in his own way—first working as a salesman for an existing wholesale dealer, then organizing a radio parts distribution business in 1925, at the age of 23. He called it the Shure Radio Company, but for all intents and purposes, it was just Sidney, alone, in a small office.

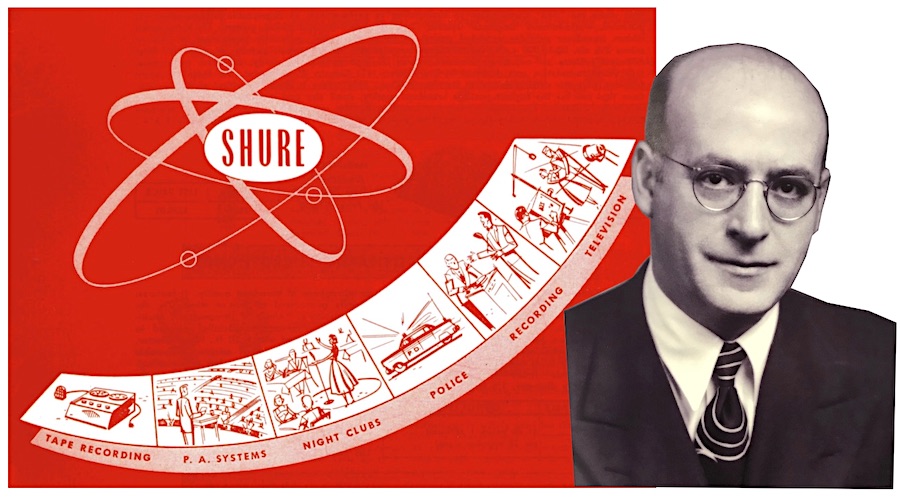

[Sidney N. Shure, circa 1930]

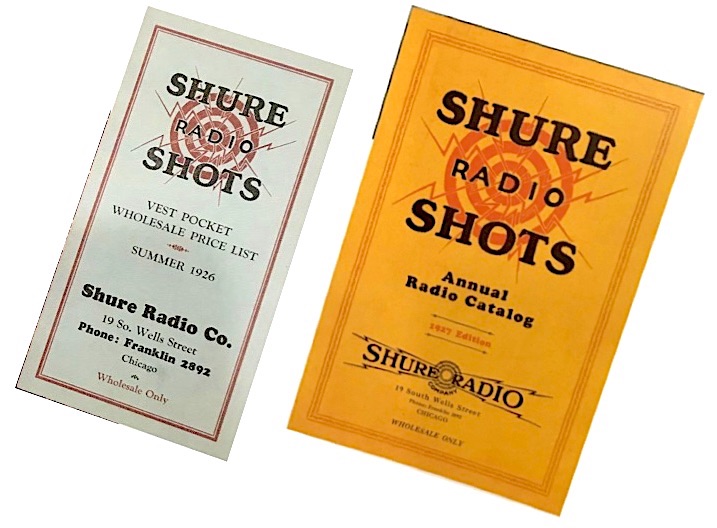

That first office was located at 19 South Wells Street—in the buzzing heart of the Loop—and while it had oodles of competition from other small-time radio part suppliers in Chicago and every other large town, it was one of just six in the nation to put out its own exclusive mail order catalog in 1926.

This wasn’t just your run-of-the-mill catalog either. Presumably taking direct guidance from his father and uncle—and likely borrowing some design and publishing talent from the Nathan Shure stable—Sidney created an eye-catching new bible for the radio enthusiast, featuring more than 1,000 products acquired from dozens of different manufacturers, large and small.

In short order, the “Shure Shots” catalogs caught the attention of their intended audience, and within a year, the Shure Radio Company was on an upward trajectory.

II. A Little Humbling

By 1928, Sidney Shure’s one-man operation had grown to 75 employees, including his own little brother Samuel Shure—fresh out of MIT with a masters degree in heating and ventilation engineering. From expanded offices at 335 W. Madison Street, the newly renamed Shure Brothers Company set forth with a new mission—not just to win over radioheads, but the wider public, as well.

While no manufacturing was being done in-house, a service department was established to handle quality control; an accounts team wrangled in more supply partners; and an advertising department whipped together new catalogs that looked an awful lot more like Uncle Nathan’s hefty wholesale novelty compendiums than the specialized radio bible of a few years earlier.

Clearly, Sidney hadn’t yet settled into the idea of his business becoming merely the premier audio tech brand in the country. Instead, his boundless ambition had him leaning more toward his family’s old business model: trying to sell a little bit of everything, and a whole lot of it.

“Our advertising department is working hard preparing our big annual fall catalog,” Sidney wrote in a 1928 letter, shortly after acquiring the parts and accessory division of a rival business, Hudson-Ross, Inc. “In the meantime, there’s plenty of good weather left for the sale and use of sporting goods, camping equipment, portable phonographs, and many other lines of summer goods.”

In an alternate timeline, the Shure Brothers Co. might well have carried on as another one of Chicago’s big wholesale dinosaurs, perhaps following the Sears mold into brick-and-mortar stores and eventual decline. But thanks to the stock market crash of ’29, that thread was unraveled within months of being sewn. With Shure’s manufacturing partners and key buyers closing up shop left and right, Sidney and Samuel had no choice but to do the same, canceling their big catalog and letting go just about all of their staff. Samuel, himself, saw little hope for recovery, and moved to St. Louis to work for a heating and ventilation business. Sidney Shure was practically back to square one.

It’s not in particularly good taste to call the Great Depression a “blessing in disguise,” but in terms of lining up the dominoes for Shure’s ultimate lasting success, it was probably a necessary evil.

III. Making Our Own

“We are in the business to perform a service to people. ‘People’ includes our customers, our employees, our suppliers, and the communities in which we live.” —Sidney N. Shure

In the first years of the Depression, S. N. Shure retreated to the world of radio, rightly presuming that, even in dark times, Americans’ desire for home entertainment would only continue to grow. With companies like Zenith, Admiral, Hallicrafters, and Motorola now able to produce affordable all-in-one tube radio sets en masse, the parts industry was no longer quite so viable, so Shure looked to accessories like radio microphones as a wiser pursuit. He still had one more key lesson left to learn about good business, however—namely, that it sometimes helps to “own” what you sell.

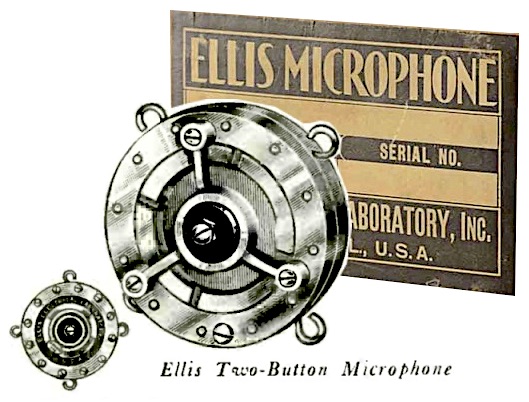

In 1930, Shure signed a distribution deal with a 65 year-old Chicago radio microphone inventor named Hugh J. Ellis. As part of the contract, Sidney created a sales division for Ellis Electrical Laboratories, Inc., and got exclusive rights to sell Ellis’s patented designs. It was a move that helped keep Shure in business, but the relationship quickly soured. Hugh Ellis felt he was getting taken for a ride financially, and started seeking other distributors. Shure responded by taking Ellis to court for violating their contract. A judge, however, ruled in favor of Ellis, saying the original deal “was invalid because of lack of mutual advantage in its terms.”

In 1930, Shure signed a distribution deal with a 65 year-old Chicago radio microphone inventor named Hugh J. Ellis. As part of the contract, Sidney created a sales division for Ellis Electrical Laboratories, Inc., and got exclusive rights to sell Ellis’s patented designs. It was a move that helped keep Shure in business, but the relationship quickly soured. Hugh Ellis felt he was getting taken for a ride financially, and started seeking other distributors. Shure responded by taking Ellis to court for violating their contract. A judge, however, ruled in favor of Ellis, saying the original deal “was invalid because of lack of mutual advantage in its terms.”

Hard to say if Sidney really was exploiting an old man, but one thing’s for sure—any future patent acquisitions would need to be airtight. The safest way of ensuring that, naturally, was for Shure to start collecting a bit more intellectual property under his own roof. As early as 1931, he hired a new engineer to work for him at the Chicago office; a youngster named Ralph Glover. Together, they worked on developing the first Shure-produced microphone—adapted from Hugh Ellis’s designs, but without the legal baggage attached.

The Shure 33N Two-Button Carbon Microphone debuted a year later, featuring a polished nickel-plated finish, concealed buttons, and a mesh-covered diaphragm. It was sleek, lightweight, and modern—an inviting alternative to clunky radio mics of the ‘20s.

Sidney Shure read the tea leaves, and this time, he didn’t over-reach or distract himself with unrelated novelties. Shure Brothers moved into a new building at 225 West Huron Street, which offered room for manufacturing and lab research. A national sales team was set up—a pretty confident undertaking in 1932—and wide-scale production began on the 33N and the company’s first condenser mic, the 40D. Maybe there was good reason to feel optimistic. Unlike the Wild West marketplace of the radio trade in the ‘20s, there were only four companies in America manufacturing microphones in the early years of the Depression, and this was drawing engineering talent to Huron Street like moths to the flame.

“As a student at the University of Cincinnati during the Depression [1935], I heard of a co-op job in Chicago,” remembered former Shure engineer Benjamin Bauer, writing in Audio Magazine in 1962. “The pay was to be 40 cents per hour but during those days we would have traveled to the ends of the earth for a job! The type of work? Developing microphones and pickups.

“No one knew too much about these products and the market for them was extremely limited. I asked Ralph Glover, at the time Chief Engineer of Shure Brothers, how long he expected the market for microphones to last. ‘Five years’ was the reply, and this was good enough for me.”

Bauer would stick around significantly longer than that, eventually collecting over 100 patents in his field; a shining example of how Shure invested in its brains to make its gains.

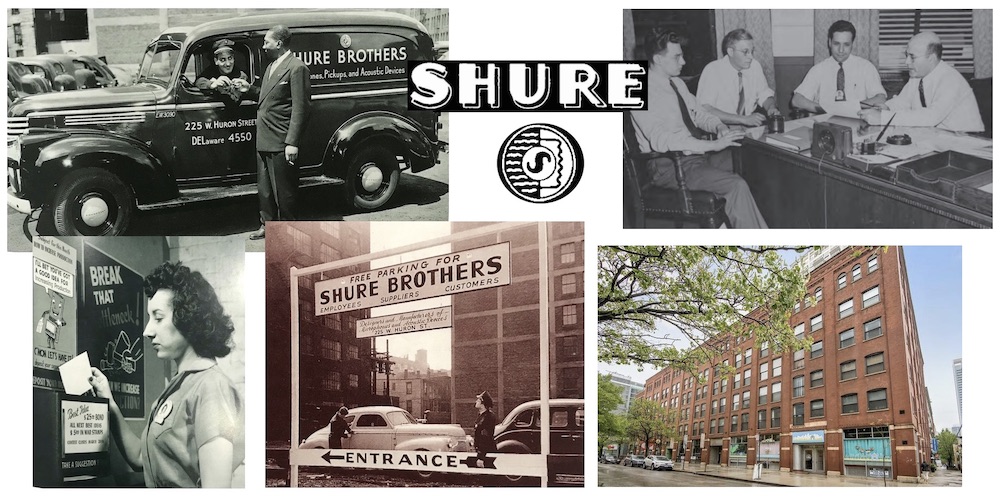

[Top Left: Company driver Hampton Donahoo hands the keys to Emmis Kooyumjian, 1946. Top Right: Ben Bauer (far left), Sidney Shure (far right) and two other men meet in 1943. Bottom Left: Employee Lois Schiska offers some worker feedback, 1943. Bottom Center: Employee Steve Mikolaczyk parks his car as security guard Sergeant Hawkinson looks on in the Shure lot on Huron Street, 1943. Bottom Right: This building at 225 West Huron Street was Shure Brothers’ headquarters from 1932 to 1956]

IV. Crystal Blue Persuasion

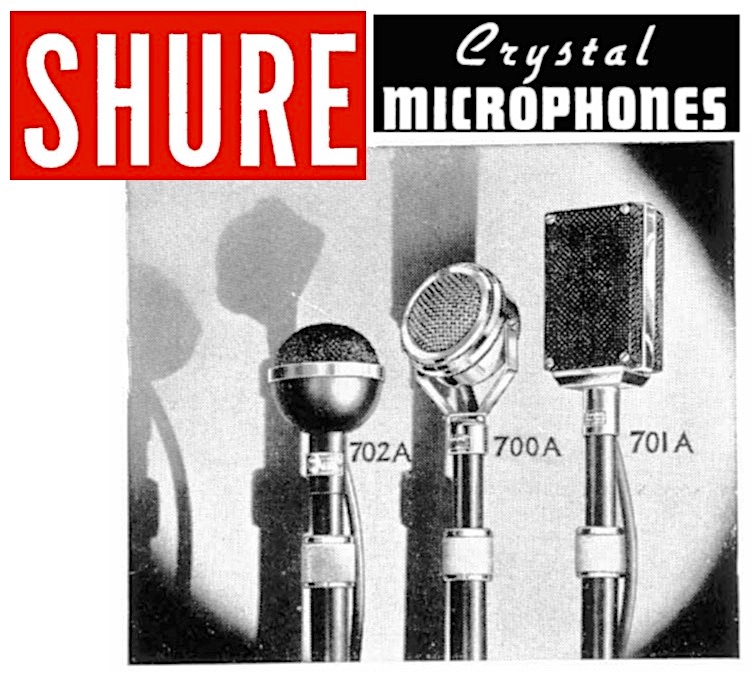

“Shure Crystal Microphones are the result of exhaustive engineering development by the technical staff of ‘Microphone Headquarters,’ working in cooperation with scientists at The Brush Development Company, the inventors of the Bimorph piezoelectric crystal unit.” —Shure Brothers catalog, 1935

In 1935, the same year college kid-geniuses like Benjamin Bauer were wandering the offices, Sidney Shure was venturing boldly back into the world of patent licensing; this time far better prepared for battle than he was during the Hugh Ellis debacle. With his new engineering department hard at work developing its own products, and his factory emerging as a national leader in its niche, Sidney was now in an enviable position to negotiate with some of the critical patent holders in the industry.

In 1935, the same year college kid-geniuses like Benjamin Bauer were wandering the offices, Sidney Shure was venturing boldly back into the world of patent licensing; this time far better prepared for battle than he was during the Hugh Ellis debacle. With his new engineering department hard at work developing its own products, and his factory emerging as a national leader in its niche, Sidney was now in an enviable position to negotiate with some of the critical patent holders in the industry.

One of the biggest fish in that sea, intellectually speaking, was the Brush Development Company of Cleveland, Ohio, which was “the leading manufacturer of microphones, phonograph pickups and loudspeakers made from piezoelectric Rochelle Salt crystals.”

Without getting too deep into the technological weeds, Rochelle Salt—or Sodium Potassium Tartrate Tetrahydrate—can essentially convert mechanical energy into electrical energy when acted upon (aka the “piezoelectric effect”), and the Brush Development Company had been centrally focused on patenting many electric products utilizing this “crystal” tech, including phonograph pickups and microphones.

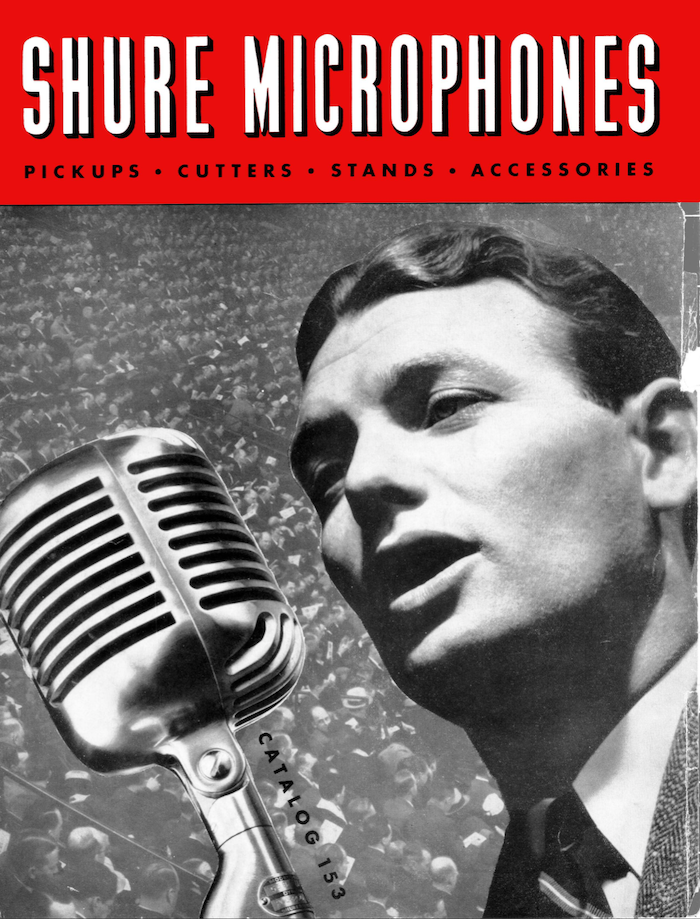

By 1933, the Astatic Corporation of Youngstown, Ohio, was already producing some of Brush’s crystal mics for commercial use, and their popularity made it clear to Shure that he needed to negotiate a licensing deal of his own. It came to fruition in ’35, and within months, Shure had its Model 70 and Model 71 crystal microphones in production, laying the groundwork for the fabulously streamlined designs of the late ’30s.

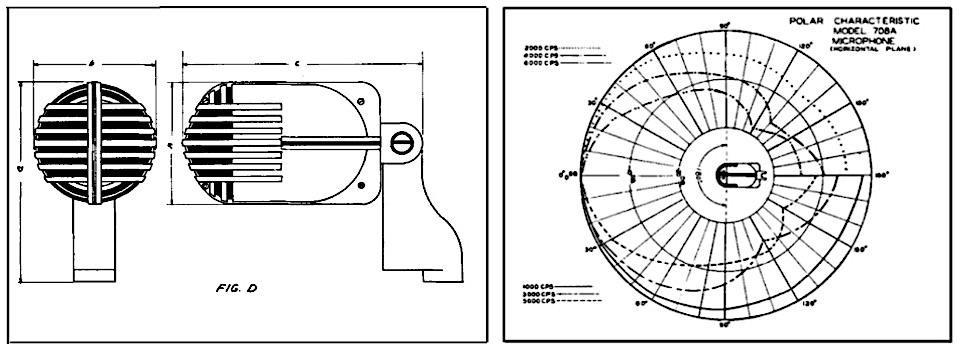

[Above: Three Shure crystal microphones from the 1940 catalog – the Straoliner 708A, the 707A Crystal, and the 717A Crystal Hand Microphone. Below: Data Sheet spec drawings of the 708A]

“Unlike carbon mics, crystal microphones didn’t require an external power source,” according to a 2020 article by Shure’s resident company historian Michael Pettersen, “which eliminated the hiss associated with the constant DC voltage running through the carbon granules, and offered a wider frequency response. But,” he adds, “they weren’t as rugged. The piezoelectric Rochelle salt crystals were prey to heat, moisture and humidity.”

Crystal mics became far more robust in later decades, but the early models—like the 708A in our museum collection—had to be handled with considerable care to maintain a high performance. That was actually part of the purpose of the streamlined Art Deco designs—it didn’t just help the mics look good in catalog pictures, it also created the aura of a high class piece of equipment; advanced and precise but ever so slightly fragile . . . not a thing to be “played” with. A price tag of $17.50 for our Stratoliner—about $320 in modern cash—also got that message across.

According to Michael Pettersen, the Stratoliner was more specifically inspired by the design of pre-war airships / zeppelins, which had recently proven their own fragility during the Hindenburg disaster.

Importantly, despite his enthusiasm for getting in on the crystal microphone game, Sidney Shure never entirely lost his “big catalog” instinct for diversification. In the late ‘30s, his company was one of the few in the world producing carbon, crystal, condenser, and dynamic mics, not to mention medical tech like the “Stethophone” and hearing aid devices, plus an exclusive line of phonograph cartridges.

The most iconic pre-war product to come out of the Shure labs—just a year before the microphone in our museum collection—was the mighty Unidyne 55. This design is instantly recognizable to the average Joe for its pop cultural relevance alone, stylishly immortalized in photographs—or hokey velvet paintings— of Elvis Presley and Frank Sinatra.

Usually credited to a freelance Chicago industrial designer named Wesley Sharer, the inspiration for this model supposedly came from the grille of a 1937 Oldsmobile Coupe Six. Like Elvis, the look was unimpeachable, but the Unidyne 55 was perhaps more significant as a technical game changer, as it was the first “single-element dynamic unidirectional microphone” on the market when it debuted in 1939.

This development was the brainchild of our aforementioned friend Benjamin Bauer—a Ukrainian refugee who became a permanent member of the Shure team in 1937, aged 24, and shortly thereafter hatched the “uniphase principle” that would revolutionize the industry.

“When Wilcox Gay came out with disc home recording in 1938,” Bauer wrote in 1962, “we were off to the races with microphones, pickups, and magnetic record cutters, which found their way into hundreds of thousands of homes in America. This taught me to never underestimate the capacity of the American public to accept complex technological advances where these served an important physical or emotional need. Being able to hear one’s own voice and saving for posterity the voices of dear ones definitely served such a need.”

[A young Frank Sinatra sings “The Song is You” with the Shure Unidyne 55 in 1943]

V. “Microphones For Victory”

“Sidney Shure approached everything he did with great conviction and intensity. He wanted to do it as well as it could be done and then do it at that level over and over again.” —Lee Gunter, U.S. Air Force, Shure Chief Engineer of New Products (employed from 1945-1995)

Sidney Shure was a born-and-bred Chicagoan, but also a man of the world, and deeply connected to his Jewish heritage. Along with supporting various local Jewish organizations and causes, he also connected to the “Holy Land” in a very specific way—becoming one of the world’s most prolific collectors of rare postal stamps from Palestine and Israel. It was an indication that the modern acoustic industrialist was interested in older forms of communication, too, and the way people have always benefited from a better understanding of one another.

When the U.S. entered World War II, Shure’s desire to help the Allied cause was certainly motivated by more than patriotism or civic duty. The Nazis were a threat to the people and institutions he held the most dear, and any way he could direct his own resources in the defense of those things was well worth the challenge.

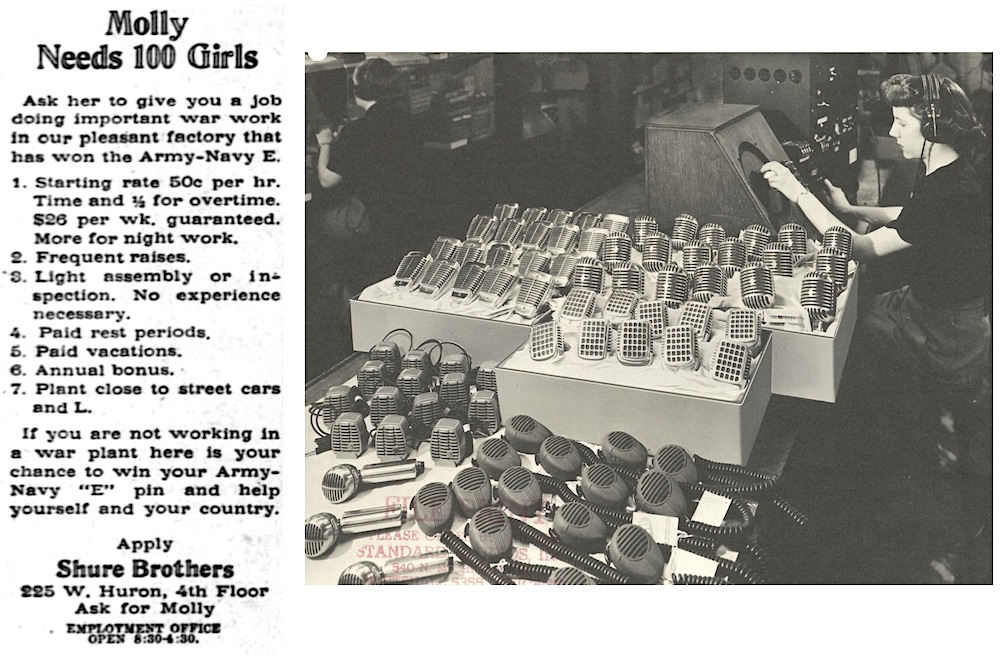

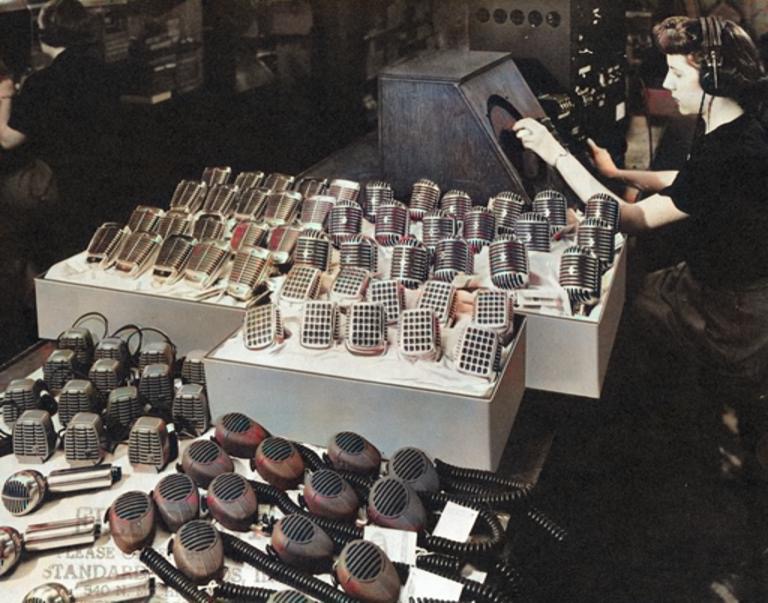

By 1942, Shure Brothers was a pivotal contractor for the U.S. Armed Forces, with the plastic, hand-held T-17 microphone emerging as the preferred model for the Army and Navy throughout the conflict. As consumer products were shelved and all attention shifted to military contracts, Shure’s wartime workforce ballooned to over 1,200, rapidly building not only the T-17, but the T-30 Throat Microphone, HS-33 and HS-38 Headset Mics, the M-C1 mic for oxygen masks, and much more.

[Left: Advertisement from a 1943 issue of the Chicago Tribune, seeking “100 girls” for wartime work at the Shure plant. New recruits coming to the employment office were told to “ask for Molly.” Right: One of Shure’s wartime employees and a stack of microphones ready for service]

Every device built for the war effort was required to meet strict military specifications, and in accordance with this, Shure’s test lab now doubled as a sort of microphone torture chamber, ensuring each piece of equipment could sustain insane amounts of abuse—from fire, water, wind, and any other element—in order to carry out its mission.

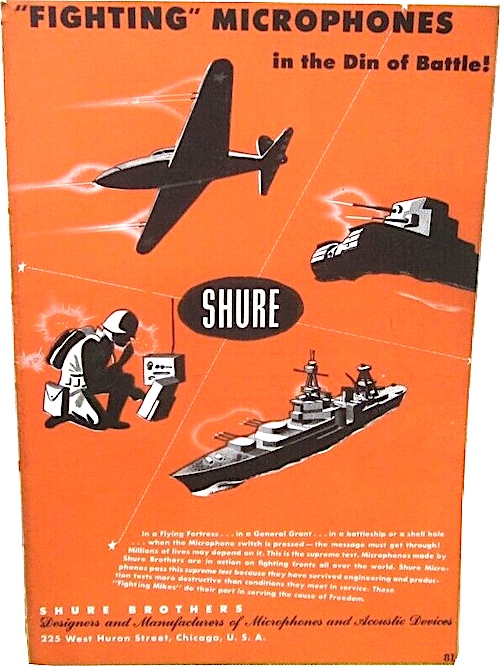

“In a Flying Fortress . . . in a General Grant . . . in a battleship or a shell hole . . . when the Microphone switch is pressed—the message must get through!” read a wartime Shure advertisement. “Millions of lives may depend on it. This is the supreme test. Microphones made by Shure Brothers are in action on fighting fronts all over the world. Shure Microphones pass this supreme test because they have survived engineering and production tests more destructive than conditions they meet in service. These ‘Fighting Mikes’ do their part in serving the cause of Freedom.”

[Women working at the Shure factory at 225 W. Huron Street during World War II]

Sidney Shure took this idea a step further when communicating with his workforce, drawing a connective thread between their efforts on the assembly line and the ultimate success of their friends and loved ones fighting overseas.

“Your Job at Shure Brothers Is Important to Victory,” one employee manual / rallying pamphlet was titled. The same booklet included an interesting sort of narrative propaganda poem, intended to inspire the workers to feel their direct connection to the cause.

A lone flyer darts beneath a cloud . . .

A lone flyer darts beneath a cloud . . .

. . . far, far below, he sights a ship convoy.

He drops lower . . . ‘Japs’ . . . Jap destroyers . . . Jap transports

. . one . . two . . eight . . twenty-two of them.

He checks for position.

He presses the button on the T-17 Microphone.

Back at headquarters, the message is flashed.

Again, microphones convert words into electrical impulses . .

a mighty air armada answers the call at Henderson Field

. . . bombers, fighters take wing at Port Moresby . .

from secret air fields, the Eagles of Liberty rise to strike.

Back home, on the other side of the world . . .

other Americans snatch up their morning papers

as they hurry to work . . .

‘JAP FLEET ANNIHILATED’ shouts the headline.

Workers bend over their work . .

putting things together that make a microphone . .

assembling parts that make a headset . .

and their pulses beat faster as they think

of the lone flyer who pressed the button on a T-17.

Shure Brothers was awarded the Army-Navy “E” Award in 1943 for its excellence as a wartime production contractor, and when the war ended, the decision was made to carry over the same military standard testing requirements as the company transitioned back into the consumer market. Raising the bar was admirable enough during wartime; the fact that Sidney Shure wanted to maintain that level of commitment in peacetime is perhaps more of a statement.

“I had tremendous respect for [Sidney Shure], because he lived every day by his principles, and he ran his company the same way,” said Vic Machin, a former executive VP at Shure who first joined the company in 1942. “He was an uncommon leader. He never thought anyone should have to compromise their principles or values to find success; and, in that way, he taught us not only how to build quality products and contribute to the success of the company, but also how to live our lives.”

VI. Rock n’ Roll & Rose

Though he died in 1995, Sidney Shure is still spoken about in almost saintly terms in the hallways of Shure, Inc. But of course, principled or not, he was just a man. After the war, his marriage to his wife Frances—mother of his two children—began deteriorating, and when he hired a 29 year-old executive assistant named Rose Langer in 1949, sparks soon flew. By 1954, Sidney had separated from Frances and, at the age of 52, married Rose.

If—being the 1950s and all— you’re imagining some sort of stereotypically “Seven Year Itch” scenario here, Rose L. Shure certainly does not fit the Monroe bimbo mold.

A self-made woman from a working class Iowa family, Rose paid her own way to earn a business degree from the University of Iowa, and once she joined the Shure team, she proved herself more than a worthy business partner and eventual successor to her husband.

Two years after their marriage, Sidney and Rose announced the move of the Shure corporate offices from their longtime home on Huron Street to a new, modern facility in Evanston (222 Hartrey Ave.). Here, in the late ‘50s, the company became the world leader in phonograph cartridge production, supplying the top record player manufacturers like RCA, Magnavox, and Emerson. It continued to push innovation, too, pioneering one of the first wireless microphone systems (Vagabond) and the first phono cartridge equipped for stereo recording (M3D). Some breakthroughs were a bit more short lived than others, like the WC-20 Phonograph Cartridge, a dashboard record player for cars (known as the “Highway Hi-Fi”) that briefly came standard in the Chrysler Imperial from 1956 to 1958. It’s unknown if thousands of scratched up Buddy Holly 45’s led to its discontinuation.

[222 Hartrey Ave. in Evanston; Shure’s HQ from 1956 to 2002]

Speaking of rock n’ roll, it’s not a stretch to say that the audio industry faced a major sea change in the ‘60s not unlike popular music itself. An explosion of record buying among teens and kids led to increasing demand for rugged, versatile, and often portable turntables. Meanwhile, the musicians themselves needed microphones that could better capture the energy of the performance without getting overwhelmed by the noise or physicality that often now came with it.

Maybe it was just a case of good fortune, but Shure’s developments in the mid ‘60s perfectly rode this wave like a Malibu surfer grooving to a Dick Dale guitar lick.

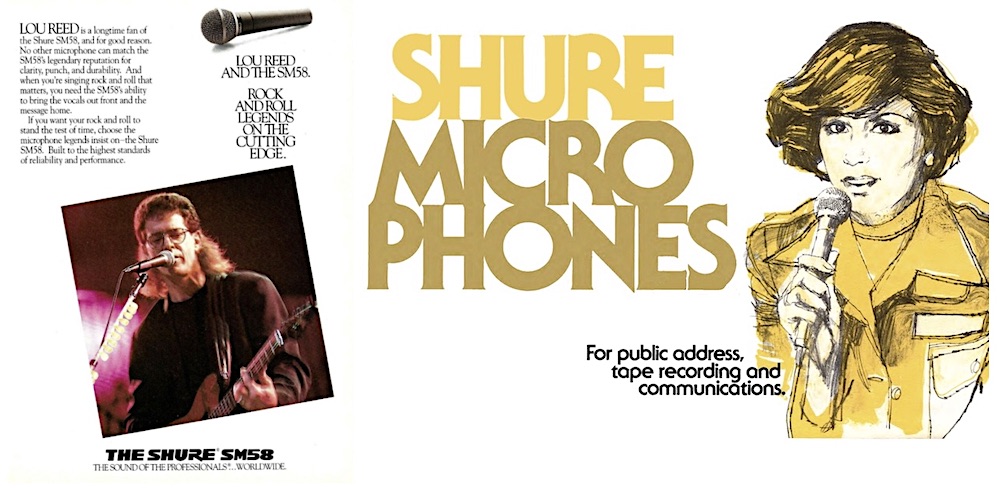

Between 1964 and 1967, the company rolled out the V-15 Stereo Phonograph Cartridge series (the first analog, computer-designed model with superior tracking), the M100 High Fidelity Stereo System (elite for its era), the Vocal Master (a “portable total sound system” with amplifier, mixer and loudspeakers), and the game-changing SM57 and SM58 microphones; the latter of which would carry into the 21st century as the highest selling professional mic on Earth.

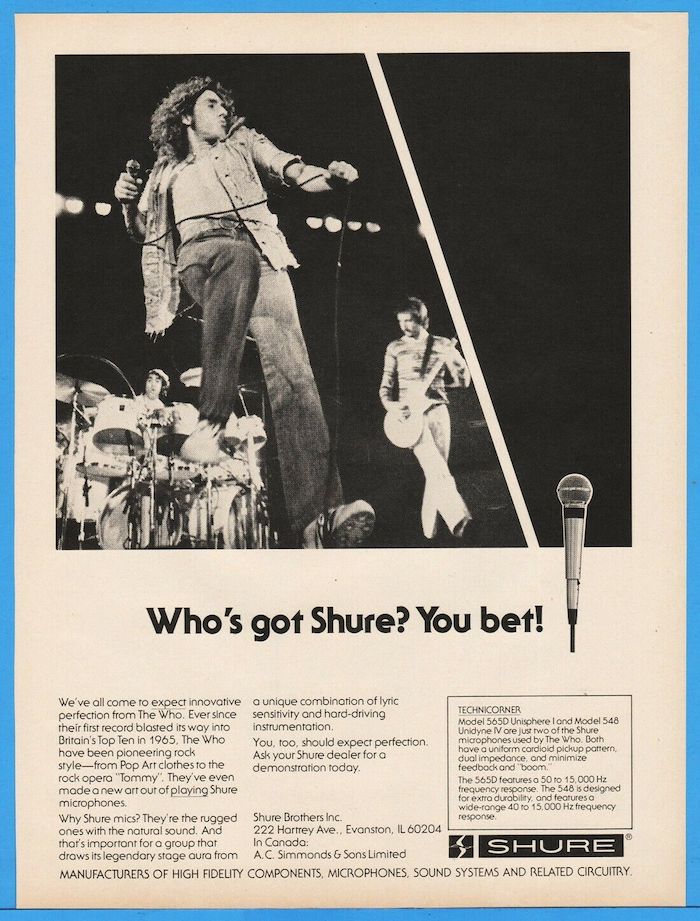

Adapting the Unisphere ball grill from Shure’s earlier 565 model, the SM58 was originally intended for use as a studio microphone, but it soon became the quintessential hand-held stage mic not just of rock’s glam age, but of crooners and country acts, as well. In the ‘70s, Shure happily embraced this development, launching an ad campaign featuring many of the biggest acts of the period, with taglines like “Ask Led Zeppelin about Mike,” “Mick’s Mike” (referring to Mick Jagger of the Rolling Stones), “Who’s Got Shure? You Bet! (featuring Roger Daltrey of The Who), “Loretta Lynn & Shure: Country Cousins,” and “First with the Fifth” (featuring the Fifth Dimension).

Adapting the Unisphere ball grill from Shure’s earlier 565 model, the SM58 was originally intended for use as a studio microphone, but it soon became the quintessential hand-held stage mic not just of rock’s glam age, but of crooners and country acts, as well. In the ‘70s, Shure happily embraced this development, launching an ad campaign featuring many of the biggest acts of the period, with taglines like “Ask Led Zeppelin about Mike,” “Mick’s Mike” (referring to Mick Jagger of the Rolling Stones), “Who’s Got Shure? You Bet! (featuring Roger Daltrey of The Who), “Loretta Lynn & Shure: Country Cousins,” and “First with the Fifth” (featuring the Fifth Dimension).

“I’ve found this microphone to be absolutely remarkable,” Roger Daltrey said in a recent Shure promotional video—noting that he’s used the SM58 for 50 years. “And no one’s more abusive to a microphone than I am.”

A 1982 magazine ad included a particular clever slogan: “The World’s Least Conservative Profession has Maintained One Rigid Tradition. The SM58.”

“In an industry that discards electronic products like ice cream wrappers, the SM58 and its close cousin, the SM57, have remained the overwhelming choice of rock, pop, R&B, gospel and jazz vocalists for the last 16 years. Why? Simply because there is no sound quite like the SM58 sound. Its punch in live vocal situations, coupled with a distinctive upper mid-range presence peak and fixed low-frequency rolloff, give it a trademark quality no other manufacturer can imitate, although others have tried.”

VII. Home and Away

Unsurprisingly, the number of imitators only increased in the years ahead, and while Shure found increasing success focusing on phono cartridges during the glory days of vinyl, they sound found themselves a bit flat footed as cassettes—and especially compact discs—laid waste to a once “rigid tradition” of analog music listening in the ‘80s and ’90s.

In 1981, at age 79, Sidney Shure semi-retired into a chairmanship, promoting James Kogen to the role of president and general manager. At this stage, Shure Brothers still had several manufacturing facilities in the Chicagoland area (Evanston, Arlington Heights, and Wheeling), along with a Shure Electronics plant in Phoenix, AZ. With Chinese imports increasingly competing at lower costs, however, Shure soon followed the all too common trend of this era; moving most of its microphone and phonograph manufacturing to Mexico, where it could employ cheaper labor. Years later, in 2005, Shure opened its first plant in China, as well.

In 1981, at age 79, Sidney Shure semi-retired into a chairmanship, promoting James Kogen to the role of president and general manager. At this stage, Shure Brothers still had several manufacturing facilities in the Chicagoland area (Evanston, Arlington Heights, and Wheeling), along with a Shure Electronics plant in Phoenix, AZ. With Chinese imports increasingly competing at lower costs, however, Shure soon followed the all too common trend of this era; moving most of its microphone and phonograph manufacturing to Mexico, where it could employ cheaper labor. Years later, in 2005, Shure opened its first plant in China, as well.

While most of Shure’s old manufacturing jobs left Chicago, the headquarters of an increasingly global business always remained close by, remaining an important local employer. Following Sidney Shure’s death in 1995, new chairwoman Rose Shure continued to serve a daily active role in the business, including the decision to move the headquarters from Evanston to a brand new hyper-modern complex in Niles, IL, in 2003 (located at 5800 W. Touhy Ave.).

[Current Shure Inc. headquarters at 5800 W. Touhy Avenue in Niles, IL]

Shure Inc.—having dropped the “Brothers” from the name in 1999—survived the stumbles of the ‘80s by returning to its microphone roots in the ‘90s and ‘00s, not only producing their classic designs, but a host of new wireless mics for the digital age. They also now produce high-end headphones, personal monitor systems, and integrated conferencing systems.

Rose Shure died in 2016, and was remembered at the time by CEO Sandy LaMantia as “a truly extraordinary woman. Our company and many charitable and cultural organizations have benefited from her thoughtfulness and generosity. I am confident that the legacy left to us by Mr. and Mrs. Shure will continue to endure in our hearts and in our minds. That is exactly the way Mr. and Mrs. Shure would want it to be.”

Sources:

Shure: Sound People, Products and Values, by Charles J. Kouri, Rose L. Shure (editor), 2001

Shure Data Sheet No. 129: Model 708A “Stratoliner” Crystal Microphone, March 1941

Your Job at Shure Brothers is Important to Victory – pamphlet, 1943

“Mandel Shure” (obit), Chicago Tribune, Jan 23, 1948

“Audio Pioneers: Ben Bauer” – Audio Magazine, May 1962

“Lose Court Battle for a Monopoly on Work of Inventor” – Chicago Tribune, July 20, 1932

“Company Fights Court’s Ruling for Inventor” – Chicago Tribune, July 22, 1932

“Microphone Maker Sidney N. Shure, 93” – Chicago Tribune, Oct 19, 1995

“Shure Incorporated Mourns the Passing of Their Chairman, Mrs. Rose L. Shure” – Shure.com, Jan 25, 2016

“The History of Crystal Microphones and Artifacts from the Shure Archives,” by Michael Pettersen, Shure.com, April 21, 2020

“Back in the Loop: Shure Returns to Chicago City Center,” by Abby Kaplan, Shure.com, March 7, 2018

“Echoes of a Legend: A Look Back at the UC Alumnus and Inventor Who Gave the World Its Most Famous Microphone,” by Brittany Barker, Magazine.uc.edu

Hi Michael. I have an old 515SB and want to know if these can be converted to have a famale XLR receiver socket in the base of the mic?

Looking forward to hearing from you.

Cheers

I have a Shure Brothers Microphone made in Chicago. The mdl no. Is 9702 everyone I’ve communicated with seem to think it’s a 55. The Brown tag has serial no. B 3205 and the OHMS is 100,000 does anyone have any knowledge about this model?

Please contact me at Shure. You can use info@shure.com for the email address. Photos of the microphone will be most helpful Michael Pettersen – Shure historian

I am trying to restore a Shure 708SH. What cryctal is used in it?

Thank you

David

Shure purchased the crystals from Brush Development Company, Cleveland Ohio. Brush went out of business decades ago. The crystal type is Rochelle Salt. Michael Pettersen – Shure historian

I just received a model M1 Shure Ultra Wide Range Crystal Microphone Serial # L6029. Can you tell me what year it was made and if I can get a 3 prong plug for it?

Thank you,

Phyllis Wilber

Please send photos of the microphone to info@shure.com M1 is an OEM model number – a mic made by Shure but sold to another company for use in its product. Michael Pettersen – Shure historian