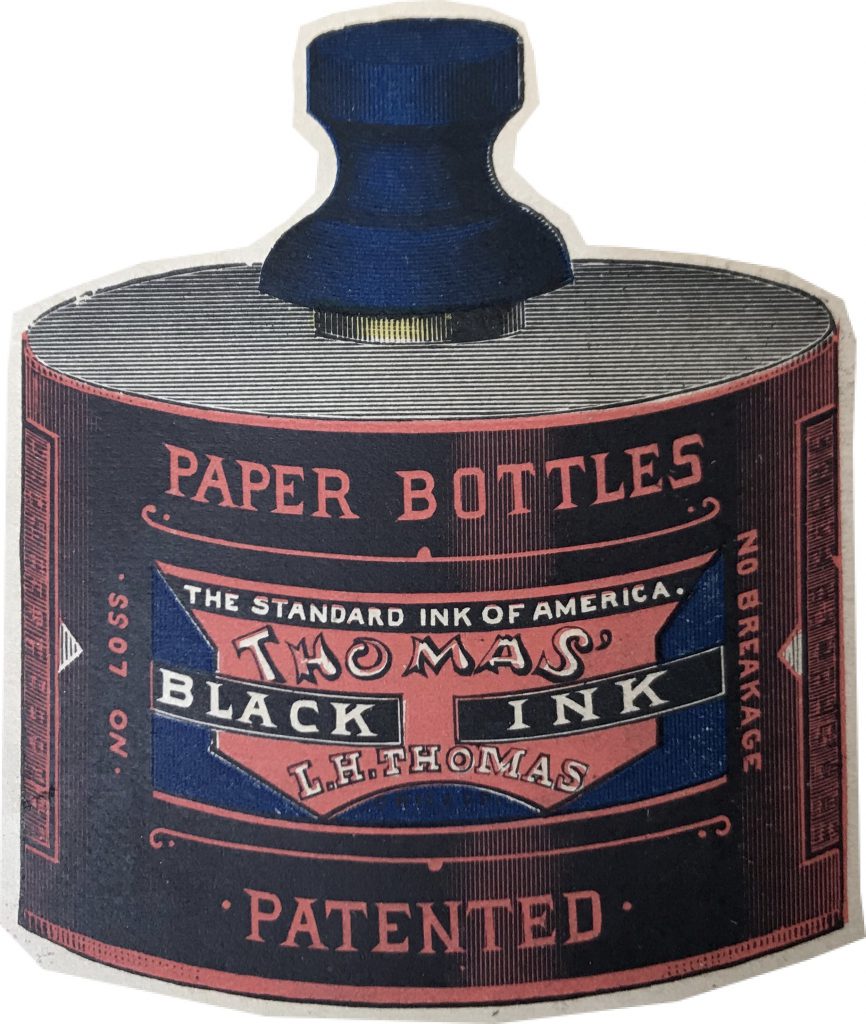

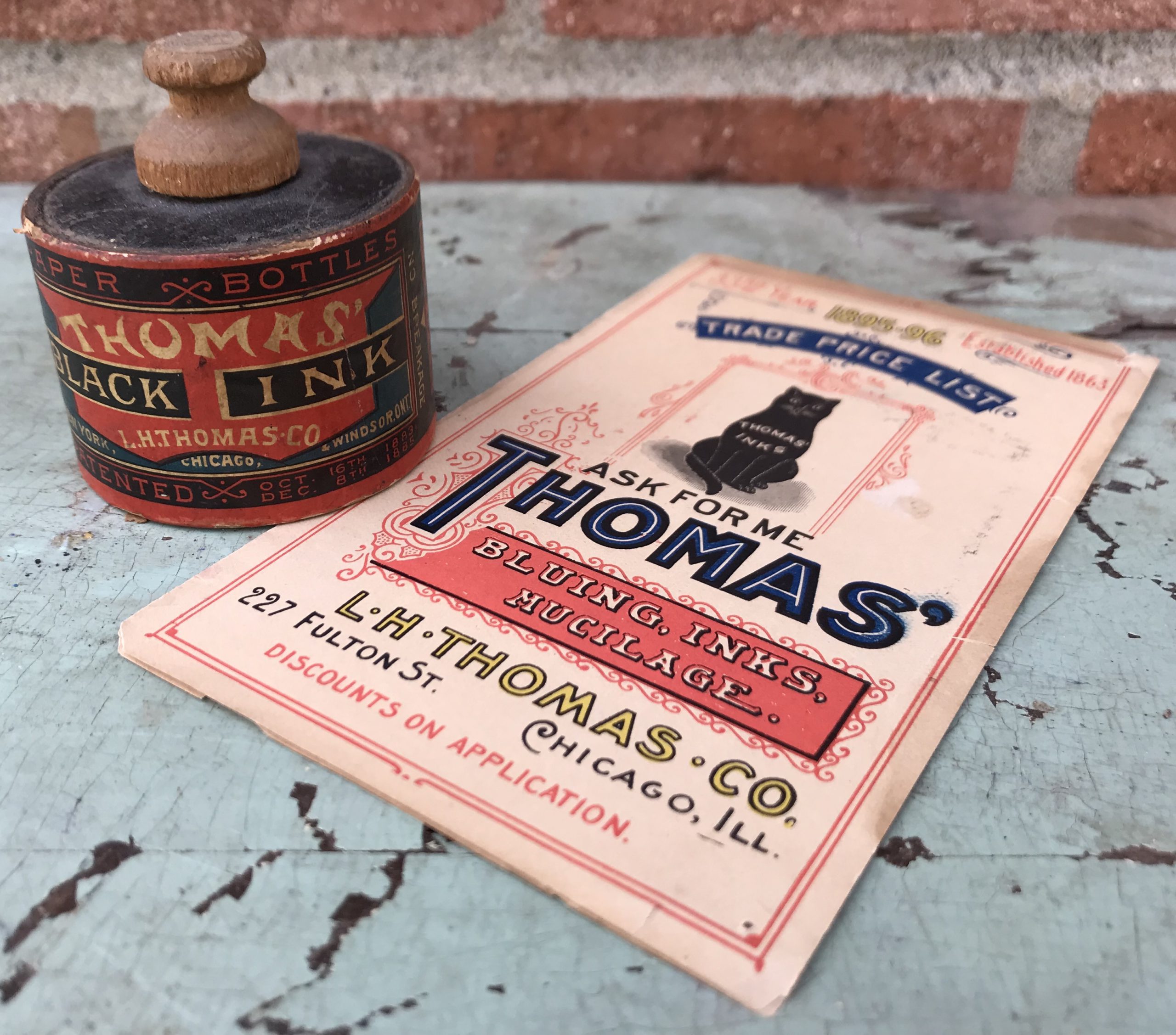

Museum Artifact: Thomas Black Ink Paper Bottle and Price List, 1890s

Made By: L. H. Thomas Co., 7059 N. Clark Street [Rogers Park] and 921 Fulton Street, Chicago, IL [Near West Side]

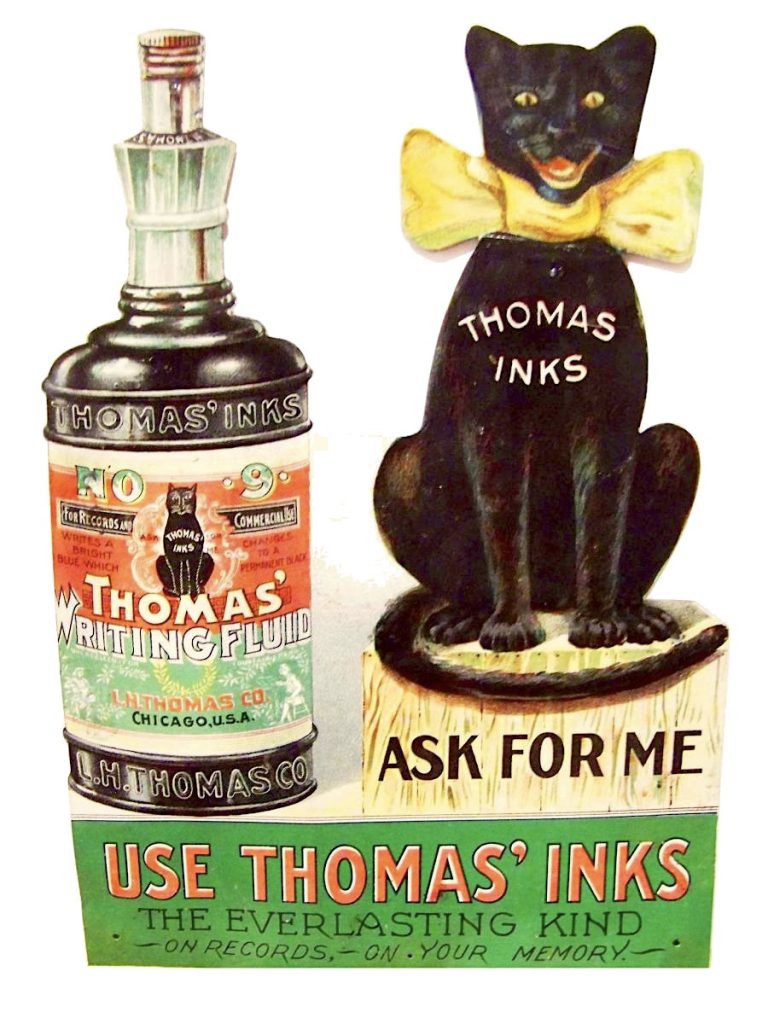

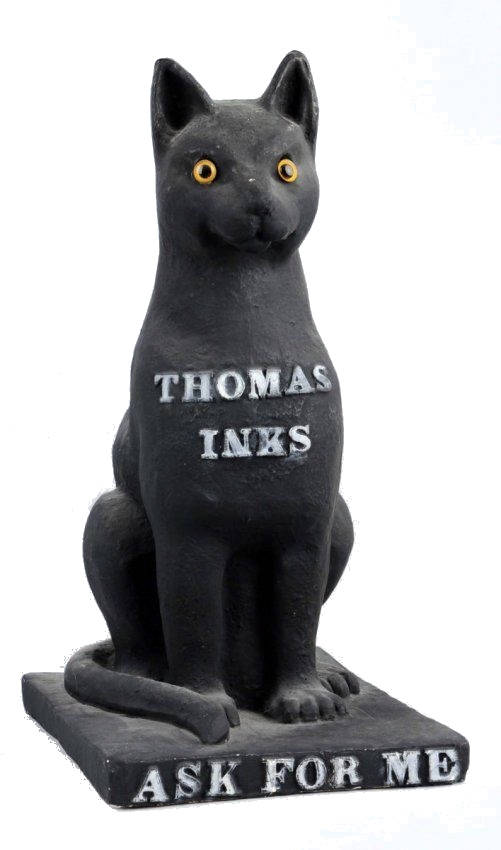

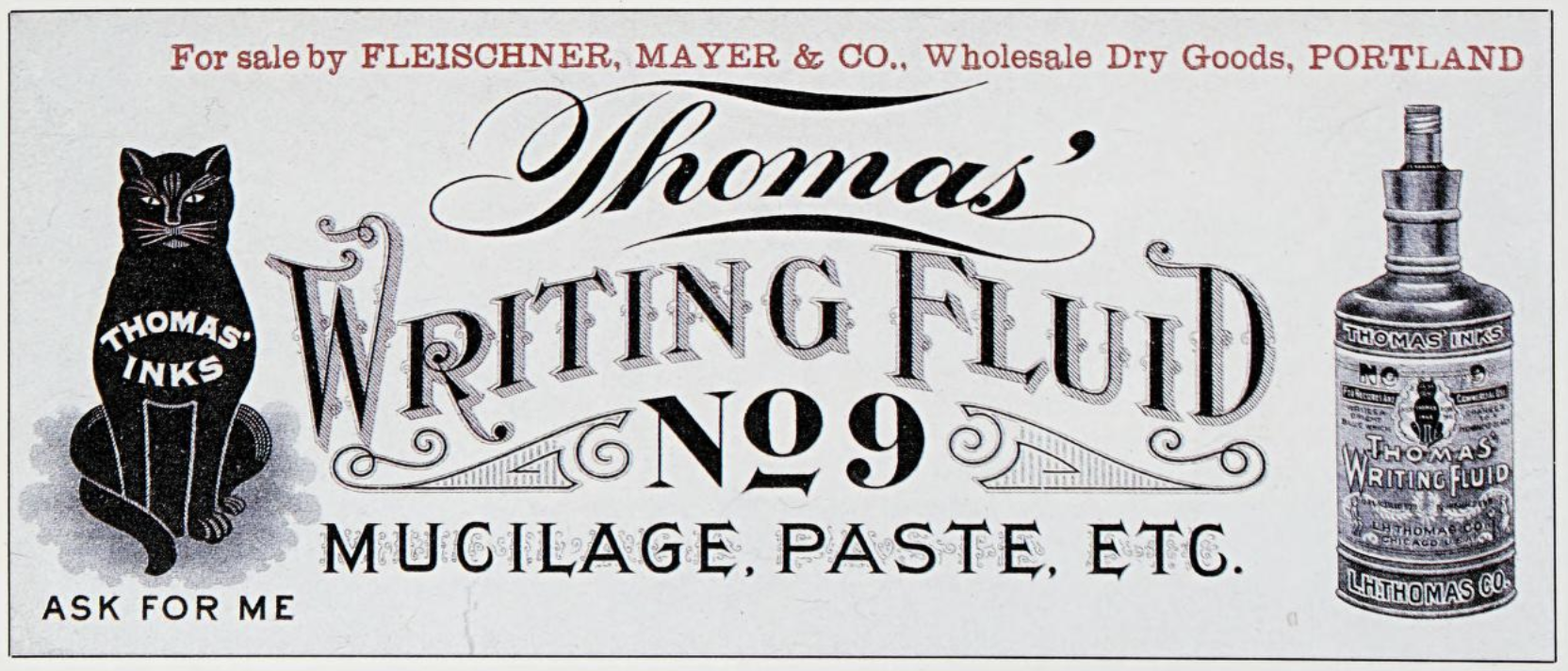

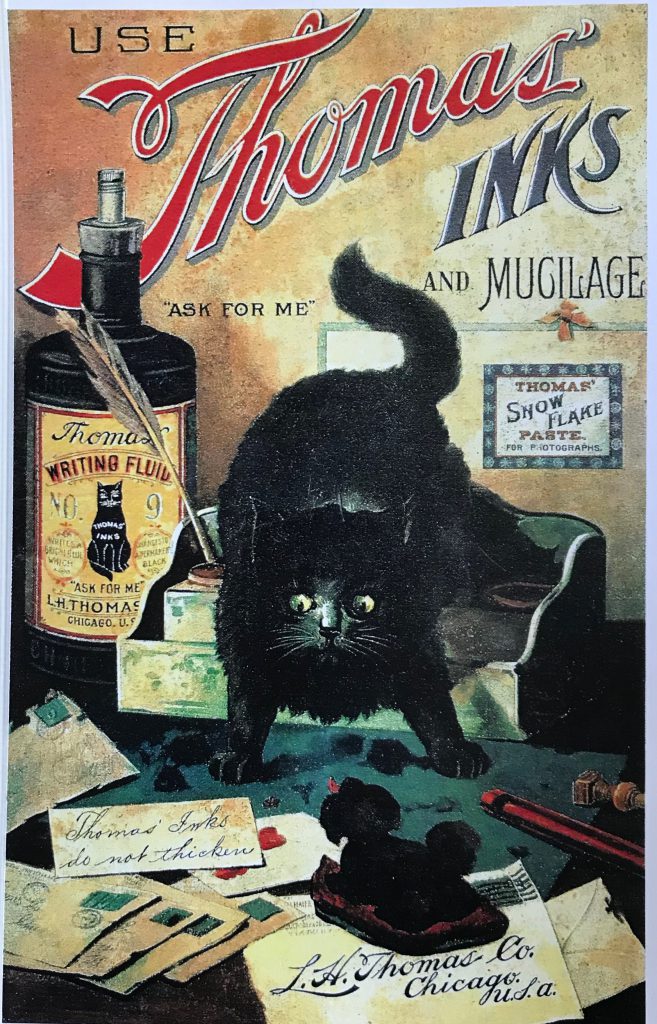

“In the considerable number of fountain pen inks on the market, none are more strongly intrenched among the trade’s ‘best sellers’ than the packages which bear the Black Cat trade mark of the L. H. Thomas Company, Chicago. The Thomas ‘Black Cat,’ by the way, was the pioneer black cat trade mark, and the position of the Thomas product in the favor of ink users is a perpetual refutation of the ‘hoodoo’ which is superstitiously supposed to attend upon the dusky feline.” —The American Stationer magazine, 1907

The L. H. Thomas Company may or may not have led the way in “dusky feline” merchandising, but they almost certainly were the first significant industrial enterprise to settle in Rogers Park. In fact, this mostly forgotten ink and bottle manufacturer was arguably the essential catalyst that helped a once tiny North Side suburb evolve into the diverse and densely populated Chicago neighborhood it is today.

The L. H. Thomas Company may or may not have led the way in “dusky feline” merchandising, but they almost certainly were the first significant industrial enterprise to settle in Rogers Park. In fact, this mostly forgotten ink and bottle manufacturer was arguably the essential catalyst that helped a once tiny North Side suburb evolve into the diverse and densely populated Chicago neighborhood it is today.

“The most recent imported accession to Chicago’s manufacturing interests is the removal here of the Thomas Ink and Blueing Works,” the Tribune reported on April 17, 1880. “They were formerly carried on at Reading, Mich., and are among the most extensive in the United States. The factory will be located at Rogers Park, and the population of that suburb will be considerably augmented by the change. Real estate and rents already show the effects.”

Rogers Park had only just reached the status of “village” two years earlier, and had a population somewhere in the range of 500 people. It would grow to 7x that count in the next few years, as Dr. Levi H. Thomas continued to expand the scope of his primary inks and mucilage factory on Chicago Ave. (present day N. Clark Street), between Greenleaf Ave. and Estes Ave. Many of the workers who joined the company—a relative balance of men and women—took up residence within the surrounding community, creating a unique sense of camaraderie both within the factory and the neighborhood as a whole.

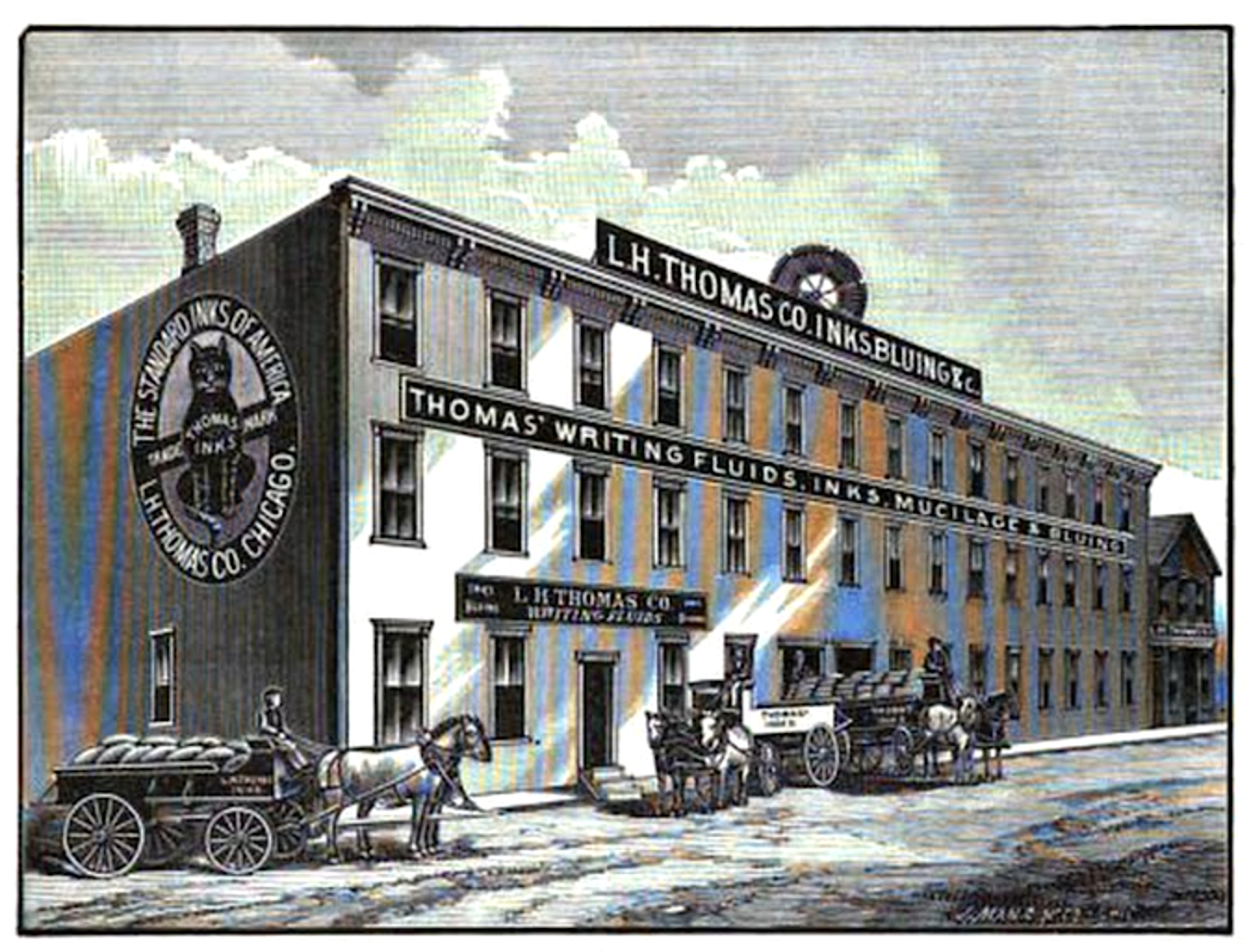

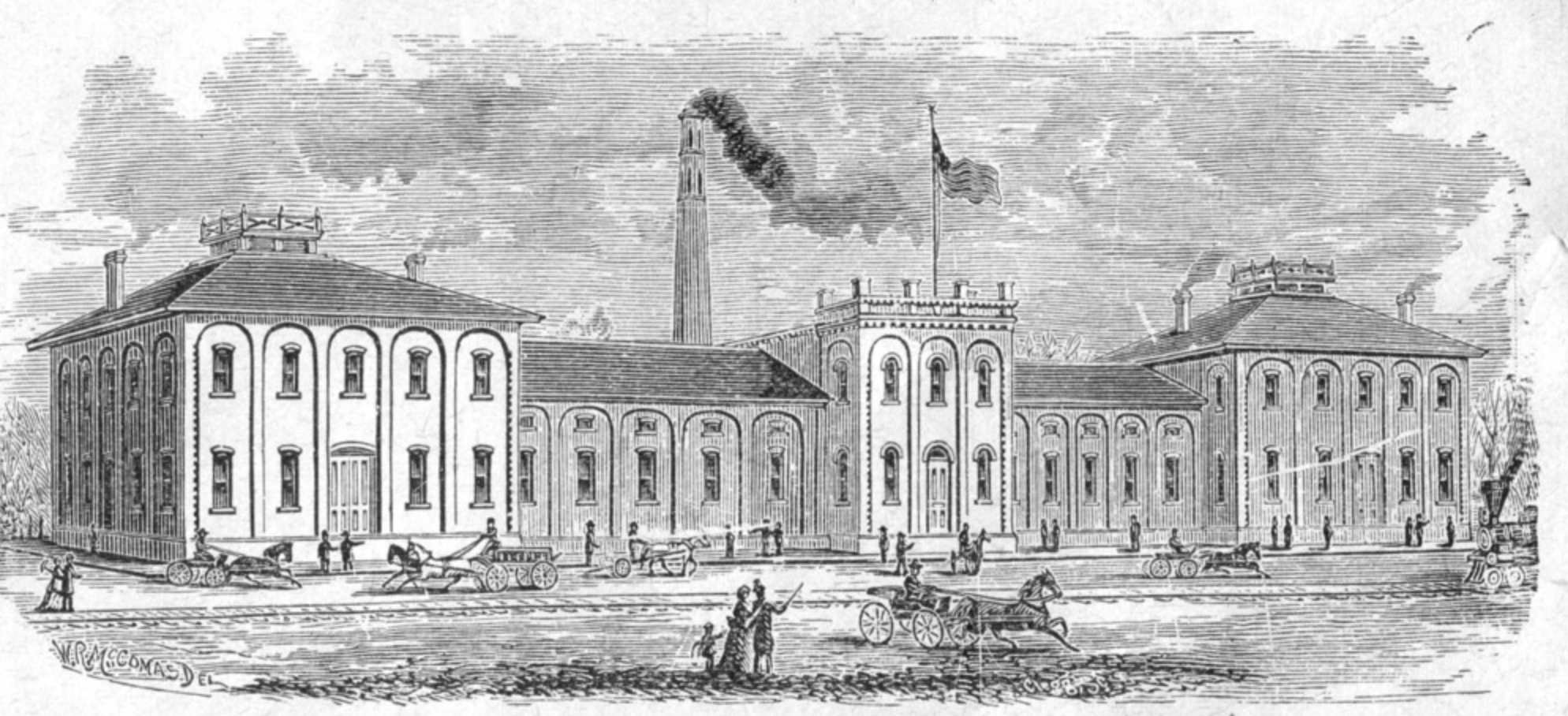

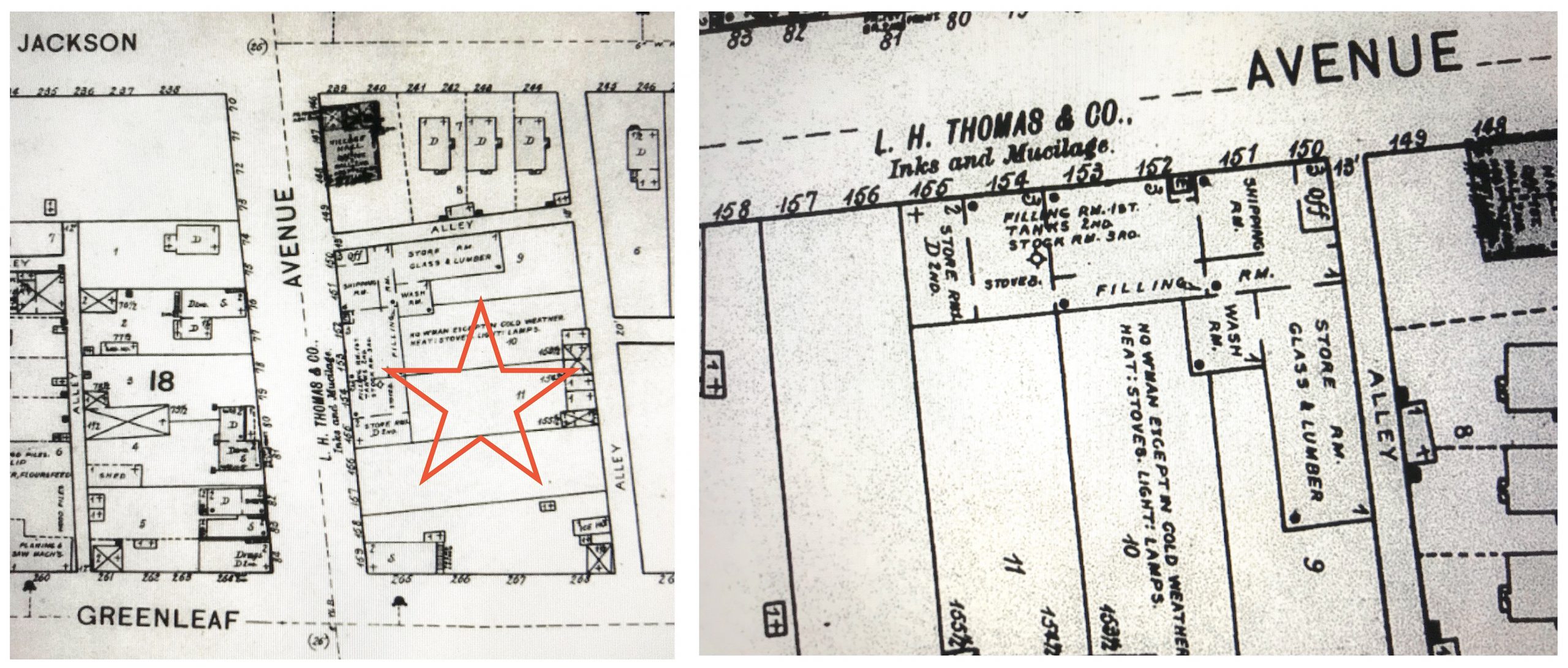

[The three-story L. H. Thomas Co. ink factory in Rogers Park, depicted here in 1890, was located on what’s now North Clark Street, north of Greenleaf Ave. and south of Estes Ave.]

[The three-story L. H. Thomas Co. ink factory in Rogers Park, depicted here in 1890, was located on what’s now North Clark Street, north of Greenleaf Ave. and south of Estes Ave.]

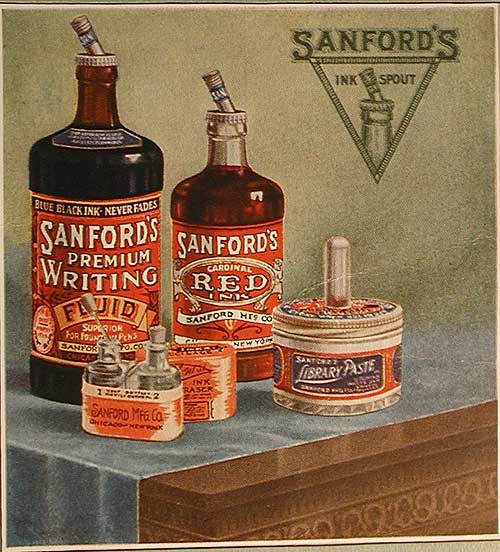

Introduced in an era still a generation shy of self-filling pens and practical typewriters, Thomas’s dipping inks—particularly its best selling Black Ink—catered to literally anyone interested in written communication; from a farmboy learning his 3 R’s to President Rutherford B. Hayes himself (who supposedly used Thomas inks at the White House). Competition was fierce, however, even in the supposedly wide open markets of the “West.” Along with the looming presence of Thomas’s biggest Chicago rival, the Sanford MFG Co., there were loads of smalltime ink-makers trying to get in on the game—including Sharp’s Inks, which brazenly set up its own plant in Rogers Park just a few years after Thomas.

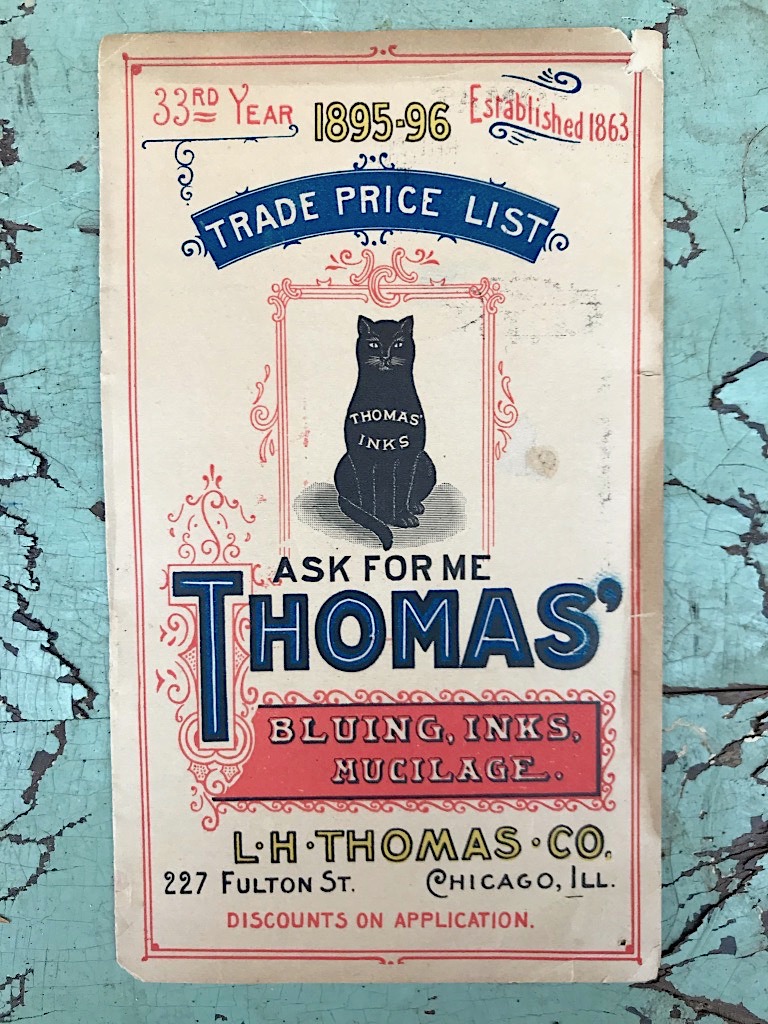

Even so, it looked for a while like L. H. Thomas might have ‘em all licked, as distribution of its recognizable black cat logo spread across the country and all the way to Europe by the 1890s. “Ask For Me,” the four-legged mascot hypnotically instructed would-be customers. And for as long as such writing fluids were still in high demand, people did indeed request “the one with the cat on it.” It was only when the new fangled tools of the 20th century started making their marks that the fangs of the feline finally lost their luster. The cat was out of the bag, and off of the bottles.

History of the L.H. Thomas Co., Part I: The Vermont Doctor

Much like Sanford Ink (the company that ultimately won this particular front of the stationery wars), the L. H. Thomas Company had its roots back East; specifically in the small town of Waterbury, Vermont.

After graduating from the nearby Castleton Medical College in 1860, Dr. Levi H. Thomas (b. 1836) started a practice in Waterbury, apparently with an emphasis on the new homeopathic trend. Shortly thereafter, he put a more practical style of healing into use (hopefully) as a Union Army medic in the Civil War, and may have also gained his first insights into the wholly unrelated world of inks and mucilage. With thousands of soldiers depending on handwritten, hand-delivered letters as rays of hope amid the fog, Thomas saw how the use of inferior inks or adhesives could add severe insult to literal injury.

And so, around 1863 or 1864, Dr. Thomas—thinking he could do better—cooked up his first batch of ink in a small back room of his home. This was not, it seems, out of character. As an amateur inventor in his spare time, Thomas collected patents on quite a few random objects in the 1860s, including a “sled brake,” “steel trap,” “clothes wringer,” “improved mop head,” and a wind-up “toy boat.”

And so, around 1863 or 1864, Dr. Thomas—thinking he could do better—cooked up his first batch of ink in a small back room of his home. This was not, it seems, out of character. As an amateur inventor in his spare time, Thomas collected patents on quite a few random objects in the 1860s, including a “sled brake,” “steel trap,” “clothes wringer,” “improved mop head,” and a wind-up “toy boat.”

“His first receptacle was a 2 gallon jar,” the American Stationer noted in an 1890 feature on the L. H. Thomas Company, retelling its origins. “The ink, which he disposed of among his neighbors and friends, was so superior that the small jar was soon displaced by the new family wash tub. Dr. Thomas recently said that when he reached the manufacture of inks on a scale which required a storage capacity of a wash tub he thought he was doing a large business. To quote his own words: ‘A wash tub full of ink, used pen by pen full, seemed enough to supply the whole world!’”

[An early Thomas Ink newspaper ad from 1870]

[An early Thomas Ink newspaper ad from 1870]

It was quite to Thomas’s surprise, then, when he realized he needed a second wash tub, and from there, a load of barrels in a rented-out barn, to meet the demand for his “smooth, flowing and indellible ink.” After a few years, even the town of Waterbury was no longer sufficient for his growing needs. So, after discussing options with his friend and fellow Waterbury businessman George J. Colby (head of the Colby Wringer Company), the decision was made for both businesses to relocate to the small town of Reading, Michigan, where’d they try to establish a new manufacturing hotspot for the West.

II. The Michigan Politician

“Thomas’ Ink and Blueing Factory was established [in Reading] in the spring of 1872,” according to 1879’s History of Hillsdale County, Michigan. “It had been run in a small way for three or four years at Waterbury, VT, but soon after the opening of the works here, it began to grow in importance, and now ranks as the foremost of the business establishments of the place.

“. . . From occupying a space of 1,600 square feet, the buildings have grown until they now cover an area of about 15,000 square feet, and the help employed has risen from 4 in number until nearly 50 hands are employed at the works, beside the agents who are engaged in selling the manufactures throughout the country.”

Thomas’s first relocation, while successful, was not 100% smooth. In 1875, when the doctor traveled back from Reading to Waterbury for a visit with his old cohorts, he was rudely arrested and briefly thrown in jail for some long forgotten, unpaid insurance assessments. This incident, if nothing else, probably made him a tad less home sick from that point forward.

[The works of the Colby Wringer Company in Reading, MI. Colby moved along with Thomas Ink from Vermont to the small Michigan town in 1872. It’s possible that Thomas may have been based out of the same complex for a time. By the 1880s, the Acme Chair Company had taken over the factory.]

[The works of the Colby Wringer Company in Reading, MI. Colby moved along with Thomas Ink from Vermont to the small Michigan town in 1872. It’s possible that Thomas may have been based out of the same complex for a time. By the 1880s, the Acme Chair Company had taken over the factory.]

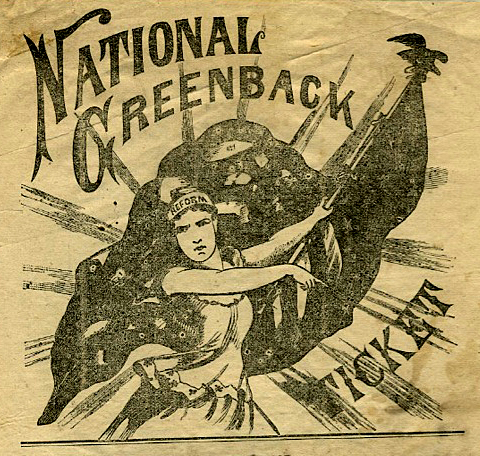

By 1878, a now 42 year-old Levi H. Thomas had become a leading figure of the village of Reading, serving as President of the town’s Board of Trustees when not tending to his regular ink factory duties. That same year, feeling bold as usual, he threw his hat in the ring in the race to represent Michigan’s 2nd District in the United States House of Representatives, running as a member of the Greenbacks—a pro-labor party that promoted anti-monopoly laws and factory reforms. Apparently, though, not everyone was buying the idea of a well-to-do, New England-born industrialist serving the interests of the Midwest working man.

“Levi H. Thomas would sell out the Greenbackers in twenty days if elected,” according to one editorial in the Adrian Press. “He is a Republican, mind you, a Republican, and his Greenbackism isn’t skin deep. No honest Greenback man can trust him. He is political pinchback—sounding brass. There’s no true stuff in or about him.”

In a letter to the editor of the Hillsdale Standard, an anonymous citizen of Reading further assaulted poor Levi’s character in an even more brutal and hilariously sarcastic takedown:

In a letter to the editor of the Hillsdale Standard, an anonymous citizen of Reading further assaulted poor Levi’s character in an even more brutal and hilariously sarcastic takedown:

“The truth of the matter is, this gentleman [Thomas] has a dreadful itching for office,” the writer claimed. “He wanted office awful bad before he left his native state, Vermont, but the people there could not appreciate the fellow’s ability, and so he came to Michigan, and like Hamlet’s ghost, it would not go down after he came here. Before the people of Reading had learned his countenance, say nothing of his great powers of mind, he demanded a set of delegates to present his name in the County Convention for the office of State Senator; but some how or other the people could not estimate him quite as high as he ranked in his own mind, and they refused to comply with the gentleman’s demands. He threatened to leave town; would not stay where he could not be appreciated. But a few of us patted him on the back and coaxed him to stay; assured him that we were deeply conscious of his great ability and gigantic intellect, and some future time would set him up where his light could shine.” Wow!

Unfortunately, I could find no comparable editorials countering these positions in the candidate’s favor, and perhaps as no coincidence, L. H. Thomas finished third in the Congressional race behind the victorious Republican incumbent, Edwin Willits, and the losing Democrat Ira B. Card. Within months—again, probably as no coincidence—Levi Thomas started pondering another change of scenery.

III. Greetings from Rogers Park

“The sales of Thomas’ ink have doubled during the past year,” Levi Thomas wrote in a letter to prospective dealers in 1878. “It is sold throughout the United States and Canada, and is today the most popular black ink in America. It is used in every department of the government at Washington.

“The stationery clerk of the United States House of Representatives is very enthusiastic in his praises of Thomas’ ink. The Supreme Court purchased it after trying a sample that had been frozen seven times. The last schedule of the general post office department calls for three times as much of Thomas’ as of any other popular ink. It is used with great favor at the White House and one of the secretaries says there is inquiry as to the ink being used in writing official documents.”

“The stationery clerk of the United States House of Representatives is very enthusiastic in his praises of Thomas’ ink. The Supreme Court purchased it after trying a sample that had been frozen seven times. The last schedule of the general post office department calls for three times as much of Thomas’ as of any other popular ink. It is used with great favor at the White House and one of the secretaries says there is inquiry as to the ink being used in writing official documents.”

It’s hard to know if Thomas’s black ink truly was the “most popular” in the country. In terms of sales, it very likely was not. But Dr. Thomas, ever the consummate wannabe politician, probably used a similar sales pitch to win over the village of Rogers Park, which gave him $10,000 to flee Michigan for the North Shore of Illinois. In return, Thomas would set up a new plant on the east side of Chicago Avenue (now North Clark Street)—a central hub for a major new influx of workers and residents.

[1891 map of Rogers Park shows the main L. H. Thomas plant on Chicago Avenue (now N. Clark), north of Greenleaf Ave. and south of Jackson Ave. (now Estes Ave.). A close-up shows that the plant’s Filling Room was on the 1st floor; Ink Tanks on the 2nd; and the Stock Room on the 3rd. There were also additional store rooms for glass and lumber and a shipping room at the north end of the complex]

[The Thomas factory in full bustle, 1880s. Courtesy of Rogers Park / West Ridge Historical Society]

[The former location of the Thomas Ink factory in Rogers Park, now a strip mall]

[The former location of the Thomas Ink factory in Rogers Park, now a strip mall]

By choosing to relocate to Rogers Park rather than the established manufacturing centers of Chicago, Thomas was also following the same blueprint he’d used in Reading—creating a company and community simultaneously, and making himself the proverbial big fish in a small pond. Promising a miniature “company town” model with improved rail access on the docket, he had little trouble staffing his new facility.

“Since the removal to [Rogers Park] of the Thomas ink and blueing factory there has not been an unoccupied tenement there,” the Tribune reported on February 27, 1881. “Rents have materially advanced [upwards of 15-25% according to a later report], and holders of corner lots are naming much higher prices than twelve months ago.”

No one could accuse L. H. Thomas of being an absentee landlord, either. From the beginning—despite putting the company’s sales offices in downtown Chicago—Levi and his wife Marilla, along with Marilla’s two children from a previous marriage, made their own home in Rogers Park. Stepson Albert Flagg, in fact, was soon made the factory superintendent and company treasurer, while son-in-law Edgar S. Foote (husband of Marilla’s daughter Flora) was a bookkeeper and salesman. The whole clan lived in what was, predictably, the finest house in the village—an Italianate-style mansion that’s still standing today at 7053 N. Ridge Blvd.

[The Jackson-Thomas House, built in 1873, is a historic landmark at 7053 W. Ridge Blvd. in Rogers Park. Located a few blocks west of where the Thomas Ink factory once stood, it was home to Levi H. Thomas and his family for more than 20 years]

[The Jackson-Thomas House, built in 1873, is a historic landmark at 7053 W. Ridge Blvd. in Rogers Park. Located a few blocks west of where the Thomas Ink factory once stood, it was home to Levi H. Thomas and his family for more than 20 years]

Within two years of its arrival, the Tribune was citing Thomas Ink as the “largest institution of its kind in the West” and “the most important building enterprise” in Rogers Park; proving of “decided advantage to that suburb.”

At the beginning of his ink-making career in Vermont, a young Levi Thomas had pondered whether a single wash tub full of ink could be enough to supply the world. Now, in Rogers Park, his company would eventually have enough storage capacity for 28,250 gallons of writing fluid. And that was only one part of the operation.

“The L. H. Thomas Company’s factory is one of the largest, perhaps the largest building in this country devoted exclusively to the manufacture of writing fluids, inks, mucilage, liquid glue and bluing,” the American Stationer determined. “The main building has a frontage of 125 feet and is 45 feet deep, three stories and a basement, with an extension 32 feet wide, running back 75 feet.” With the purchase of other neighboring buildings, Thomas had “an actual floor space of over 21,000 square feet devoted exclusively to the business.

“To insure and maintain a high and uniform standard in its numerous productions, [Thomas] now manufactures many of its own chemicals and refines all of its own galls, and in its mucilage department extracts all of its gums. It also manufactures all of the wooden boxes and cases of which it uses thousands every month.”

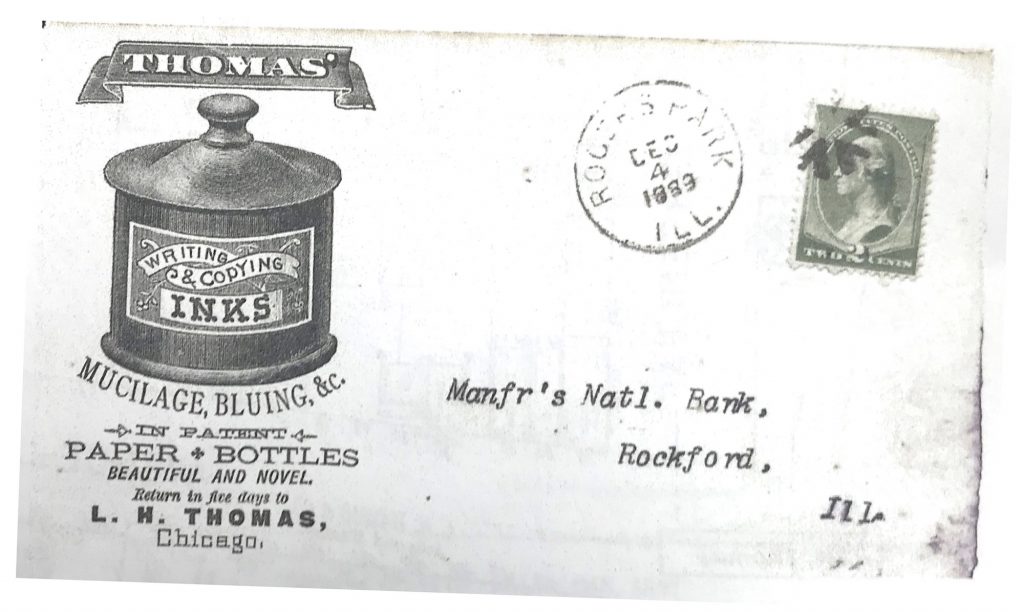

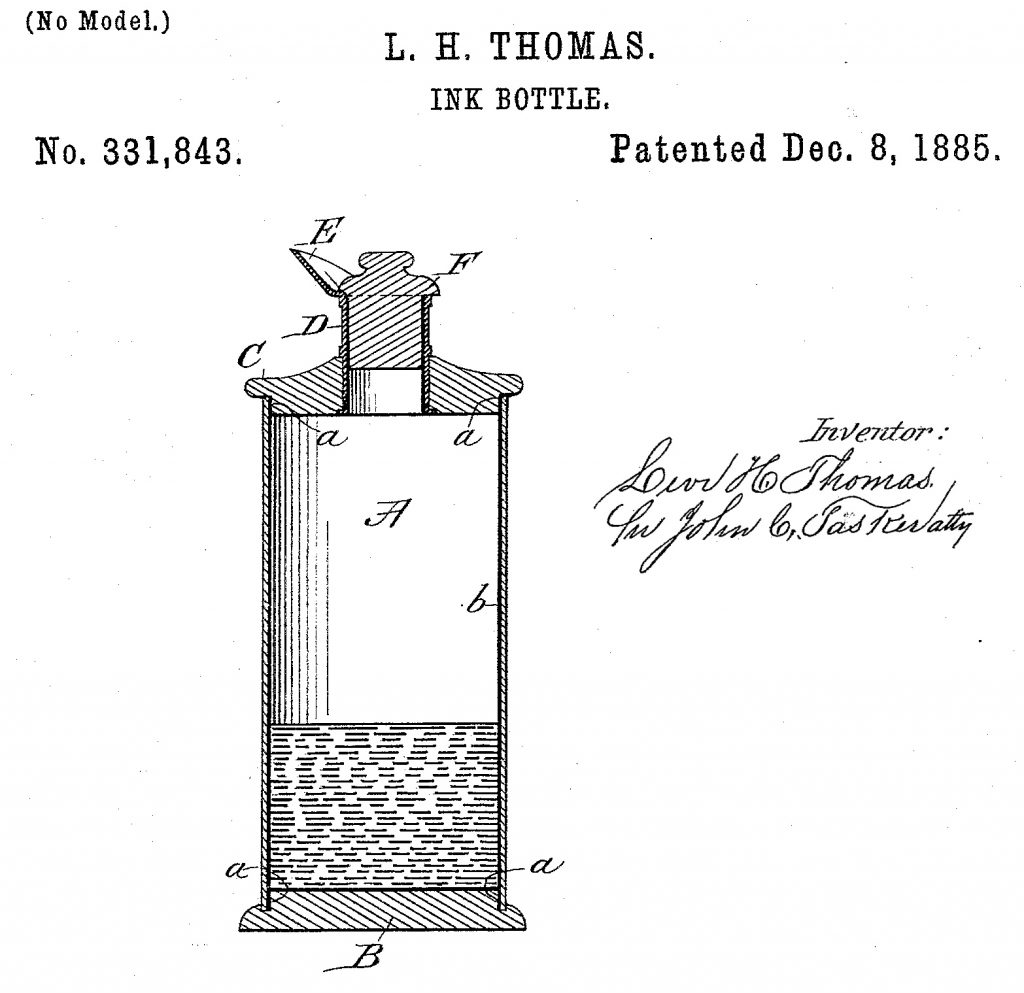

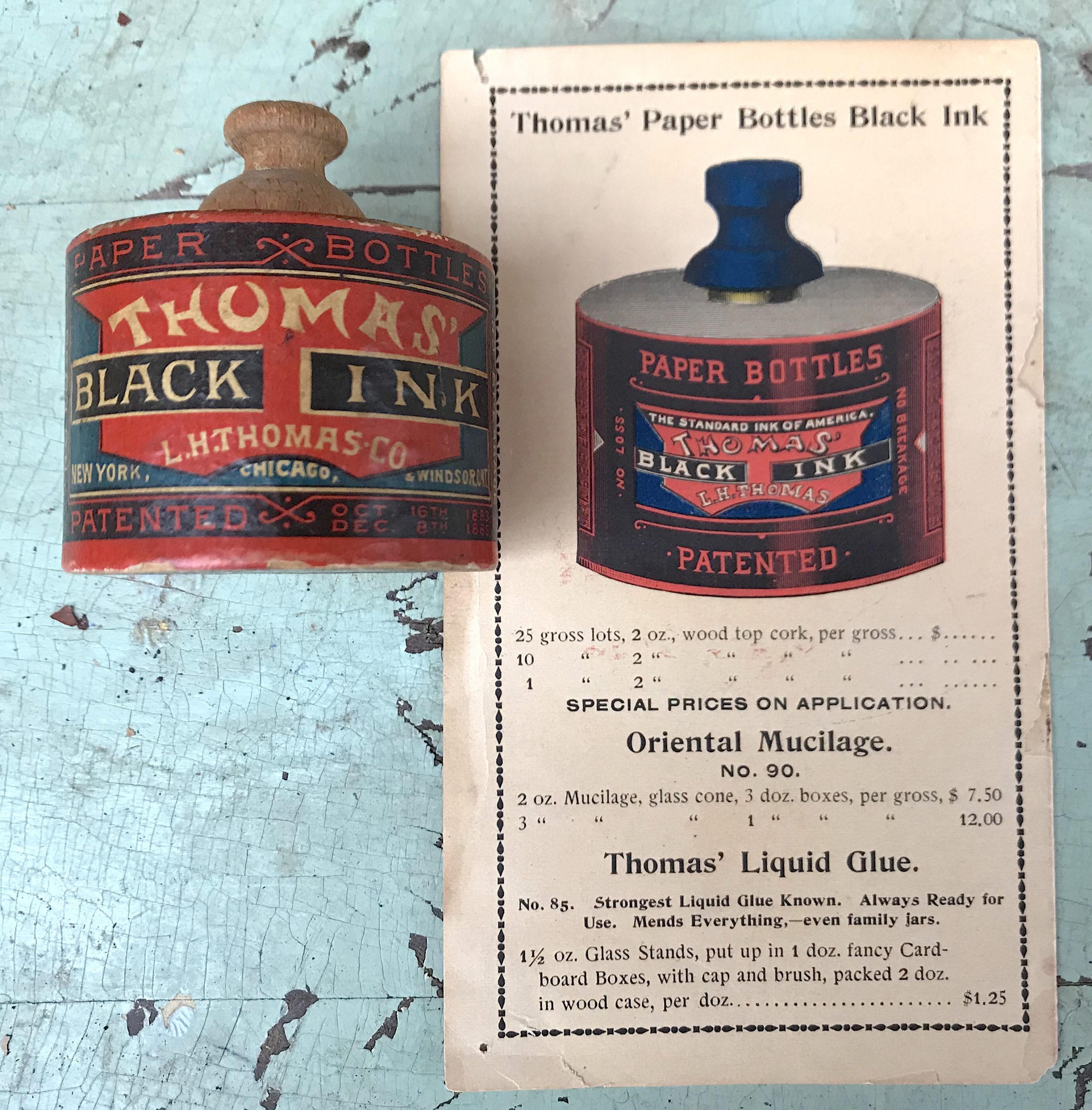

For several years, Thomas had still relied on multiple car loads of glass bottles to be shipped in from outside manufacturers, taking a good chunk out of his profits. For this, too, he’d hatched a rather peculiar solution, introducing a new, cheaply-made paper ink bottle of his own design; a potentially revolutionary innovation.

IV: A New Breed of Bottle

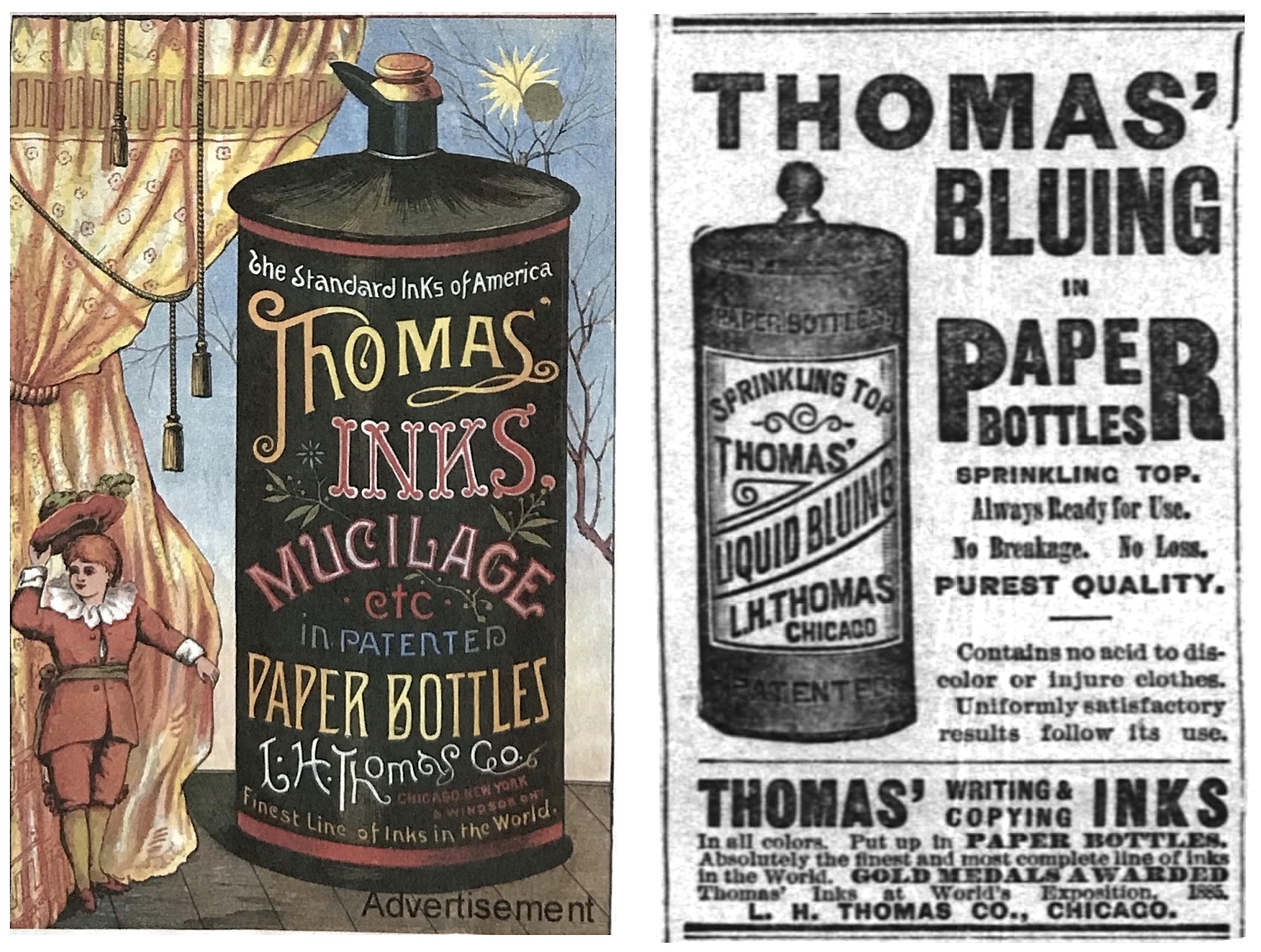

“Among the recent inventions there is probably none connected with the stationery business that is as novel or that is attracting as much attention as the new paper bottles, manufactured by L. H. Thomas, Chicago.” —American Stationer, 1885

Patented in 1885 (No. 331,843), Thomas’s paper bottles—such as the type in our museum collection—caused a big enough sensation out of the gate that a whole separate bottle-making plant was put into production in Rogers Park at Lunt Avenue and Ravenswood. Here, Thomas was able to rapidly produce cheap paper bottles not just for his own inks, but—weirdly—for many of his competitors, as well; including the Sanford MFG Co., E.A. Palmer & Co. of Cleveland, and Carter, Dinsmore & Co. of Boston. The boom in sales helped Thomas secure a new downtown high-rise for his sales team at 59 Michigan Avenue, and by 1887, the paper bottle phenomenon was being touted as far away as London, where shares for a new UK-based Paper Bottle Company, LTD, were made available for purchase.

Patented in 1885 (No. 331,843), Thomas’s paper bottles—such as the type in our museum collection—caused a big enough sensation out of the gate that a whole separate bottle-making plant was put into production in Rogers Park at Lunt Avenue and Ravenswood. Here, Thomas was able to rapidly produce cheap paper bottles not just for his own inks, but—weirdly—for many of his competitors, as well; including the Sanford MFG Co., E.A. Palmer & Co. of Cleveland, and Carter, Dinsmore & Co. of Boston. The boom in sales helped Thomas secure a new downtown high-rise for his sales team at 59 Michigan Avenue, and by 1887, the paper bottle phenomenon was being touted as far away as London, where shares for a new UK-based Paper Bottle Company, LTD, were made available for purchase.

“A novel and important industry has of late sprung up in Chicago,” the Times of London reported on May 7, 1887, “whence it is spreading to other parts of the United States and is now being introduced into England. This is the manufacture of paper bottles by a process which is the invention of Mr. L. H. Thomas of Chicago. These bottles are unbreakable, and of various shapes and sizes suited to the requirements of the trades and manufacturers using such articles. They are produced very much more cheaply than the ordinary bottles made of glass, stoneware or tin . . .” and have the further advantages of “not requiring any packing material in transit” and, “the weight being greatly reduced . . . saving in the cost of freight.”

Thomas installed special machinery for the making of his bottles, and set out several steps for their construction.

First, according to the Times, “a large sheet of paper, glued or cemented on one side, is rolled on a mandrel into a tube of any required length, thickness and diameter.”

First, according to the Times, “a large sheet of paper, glued or cemented on one side, is rolled on a mandrel into a tube of any required length, thickness and diameter.”

Next, “an outer glazed covering, which consists of the colored labels or inscriptions for the bottles, is then glued on the tube, which is afterwards cut up into the required lengths for a given number of bottles.”

“The tops and bottoms (made of either paper or wood) are cemented in, and the interiors are lined with a fluid composition, which sets hard and will resist acids and spirits, adapting the bottles for containing ink, blacking, dyes, paints . . .”

If anything, Thomas’s invention only sounds more intriguing 140 years later, when the idea of any alternative to plastic bottles is worthy of analysis. In its own time, though, the initial enthusiasm over the design gradually started to fade. For the purposes of filling an ink well, the stout paper bottles—such as our vintage Black Ink artifact—didn’t have a proper pouring nozzle, and without a glass exterior, it was harder to tell how much ink was actually left in the container. The disposable nature of the paper bottles, on the bright side, has probably enhanced their collectability. With the vast majority winding up in the rubbish bin, a nice-looking Black Ink bottle like our museum piece is a rare window into Dr. Thomas’s shining moment.

[The paper bottle from our museum collection is a rare surviving example of these nice but disposable designs]

[The paper bottle from our museum collection is a rare surviving example of these nice but disposable designs]

As noted on the back of our museum bottle, the mid 1880s also saw L. H. Thomas awarded Gold Medals for its inks at major conventions in New Orleans (1885) and Toronto (1886). Offices were opened in New York and a new factory in Windsor, Canada. The name L. H. Thomas was spoken with reverence in offices, schools, and the local hangouts of Rogers Park.

And then, quite abruptly, the good doctor sold out.

V. Out of the Park and Into the City

It’s hard to say why L. H. Thomas decided to sell his thriving ink business in 1889. According to the American Stationer, he had simply “retired to enjoy the fruits of years of industry.” And indeed, he and his wife Marilla did maintain their residence at the Jackson-Thomas Mansion into the 20th century. Still, it seems equally plausible that Levi had switched his eggs to a different basket, wholly believing that his handy paper bottles would actually prove more profitable long term than those boring inks and glues. This, of course, did not pan out. We know that Thomas eventually sold his bottle patents to a manufacturer in Glassboro, New Jersey, but it shut down its production for good in 1893 after just two years in operation. “With the closing of the doors a unique industry will be abandoned,” the Philadelphia Times reported.

If Thomas still had any lingering political aspirations, those never came to fruition either. In fact, despite his success in business and high-profile status in Chicago, the later years of Levi Thomas’s life are a complete mystery. It appears that he moved to New Jersey after the death of his wife, and was living in a home there as late as 1915. His date of death is unknown, though, and as of yet, no pictures of the man seem to have survived either.

If Thomas still had any lingering political aspirations, those never came to fruition either. In fact, despite his success in business and high-profile status in Chicago, the later years of Levi Thomas’s life are a complete mystery. It appears that he moved to New Jersey after the death of his wife, and was living in a home there as late as 1915. His date of death is unknown, though, and as of yet, no pictures of the man seem to have survived either.

The fate of the L. H. Thomas Company, as well, has a faded blurriness unworthy of such a fine writing solution.

At first, the transition to new ownership looked promising, as new president Edward H. Alling—a former salesman for Carter’s Ink out of Boston—brought youth and enthusiasm to the role. Unfortunately, Alling was almost immediately sued by Carter, Dinsmore & Co. for breaching the non-compete clause in his contract, and within a year, was replaced in his role by industrialist Warren McArthur—best remembered for the house in Hyde Park that his friend Frank Lloyd Wright built for him [Warren McArthur, Jr., his son, also became a noted furniture designer].

McArthur and his fellow shareholders—including VP George W. Andrew and secretary J. Warren Sanders—had a contract to pay Levi Thomas 10% of their gross receipts until $40K had been paid. But this deal, too, wound up disputed in the circuit courts, as the new owners accused Dr. Thomas of fraudulently over-stating the value of his recipes, dyes, and property. It’s not clear how this played out, but suffice it to say, all loyalty to the old guard was now pretty much out the window at the “new” L. H. Thomas Company.

McArthur and his fellow shareholders—including VP George W. Andrew and secretary J. Warren Sanders—had a contract to pay Levi Thomas 10% of their gross receipts until $40K had been paid. But this deal, too, wound up disputed in the circuit courts, as the new owners accused Dr. Thomas of fraudulently over-stating the value of his recipes, dyes, and property. It’s not clear how this played out, but suffice it to say, all loyalty to the old guard was now pretty much out the window at the “new” L. H. Thomas Company.

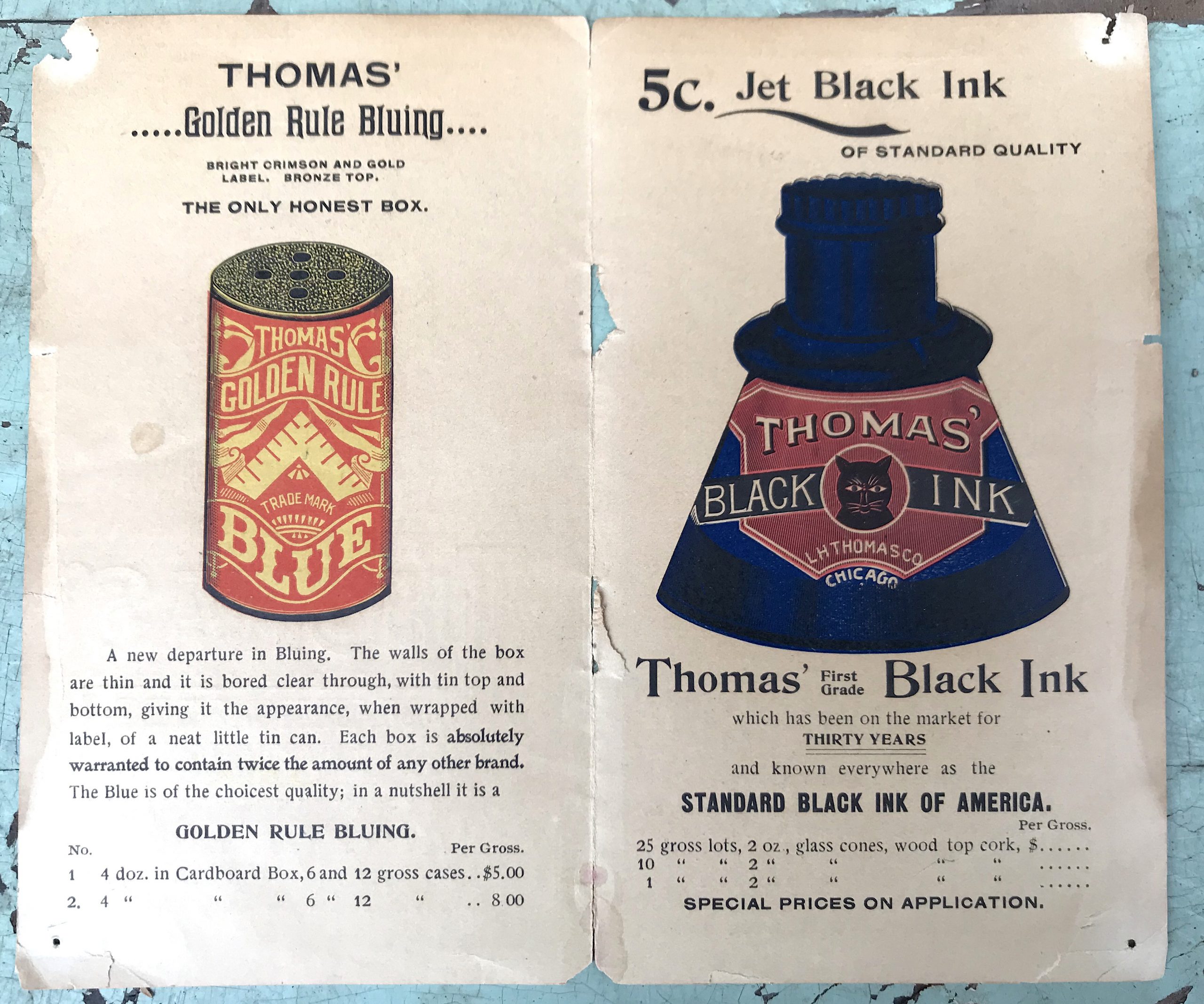

In the early 1890s, McArthur and his crew quickly worked to remold the Thomas Ink brand into their own vision of “Quality + Style.” This meant scrapping almost all of Levi’s increasingly unpopular paper bottles in favor of new colorful glass designs with proper metallic spouts, as well as a complete overhaul of the company’s labels and logos, leading to the welcome proliferation of the Thomas Ink Black Cat and its trademarked slogan: “Ask for Me.” As a slightly less popular adjustment, they also opted to abandon Rogers Park for what an 1892 issue of the American Stationer called “more commodious quarters in the heart of the city of Chicago.”

Rogers Park was actually annexed to the city a year later, so in some ways, the L. H. Thomas Co. wasn’t really “leaving town.” But the emptying of the original factory, followed by a major fire that leveled much of the Rogers Park business district in 1894, pretty well ended that era.

VI. The Ink Dries

As perhaps some level of consolation to the Rogers Park community, Thomas’s downtown “Quality + Style” era didn’t have much of a shelf-life either. In February of 1894, less than two years after the company moved into its new four-story plant at 229 E. Kinzie Street, a reporter for the American Stationer stopped by the building to find it closed up with a placard on the door: L. H. Thomas Company removed to 227 Fulton street; telephone 4257.

“As this number corresponds with the office number of the Sanford Manufacturing Company,” the reporter concluded, “the indications are that the Thomas Company has been merged with the Sanford. I tried twice to catch the Sanford Company through the telephone, but the central office informed me that the firm was busy and to ‘call again.’”

It doesn’t seem like the executives from either Sanford or Thomas ever made much of a proper public announcement of it, but indeed, the more successful of the two rivals had finally absorbed the other, setting up the small remains of Thomas’s operation right alongside its own in Fulton Market (at what would now be 921 W. Fulton Street). It was hardly newsworthy, maybe, because Thomas’s business had begun dwindling—a likely result of the rough economic recession of the period and Sanford’s increased grip on the trade.

It doesn’t seem like the executives from either Sanford or Thomas ever made much of a proper public announcement of it, but indeed, the more successful of the two rivals had finally absorbed the other, setting up the small remains of Thomas’s operation right alongside its own in Fulton Market (at what would now be 921 W. Fulton Street). It was hardly newsworthy, maybe, because Thomas’s business had begun dwindling—a likely result of the rough economic recession of the period and Sanford’s increased grip on the trade.

By 1898, still functioning as a division of Sanford, L. H. Thomas employed just 20 workers of its own; 10 men and 10 women. The company’s de facto president was William Rodiger, better known as Sanford’s vice president.

Certainly, Rodiger and Sanford Company president William Redington could have just opted to squash the Thomas brand completely, but they probably appreciated the company’s 30 years worth of good will in the industry, and there were still plenty more of those cute black cat labels that needed dispensing.

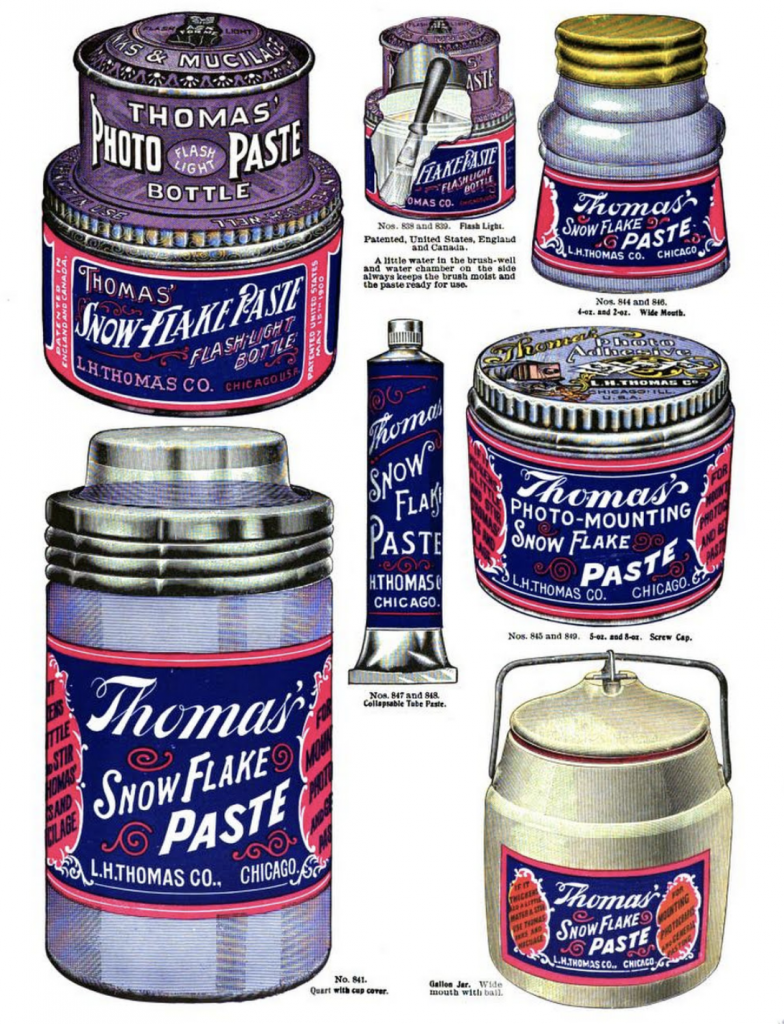

[Images from the Thomas line of products, 1907]

[Images from the Thomas line of products, 1907]

On November 27, 1900, the L. H. Thomas Company finally returned to the local headlines, but for the wrong reason. That’s when a major fire tore through the Fulton Street building they shared with Sanford, sending thousands of gallons of ink into the streets and costing upwards of $200,000 in total damages.

“Our loss is total,” William Rodiger said at the time. “But we will resume business without any delay. We hope to start up inside three weeks, although the manufacturing process cannot be put under way in less than three months. It takes that time for a tank of ink to reach the proper stage for bottling.”

“Our loss is total,” William Rodiger said at the time. “But we will resume business without any delay. We hope to start up inside three weeks, although the manufacturing process cannot be put under way in less than three months. It takes that time for a tank of ink to reach the proper stage for bottling.”

Sanford Ink, which is still in business today and owns such brands as Sharpie, Paper Mate, and Elmer’s Glue, recovered just fine, opening a major new factory in 1902 at Congress St. and Peoria Street. Here, they continued to maintain an office for the L. H. Thomas Co. and sell some of its more popular brands, including “Flashlight” bottles and “Snowflake” paste, as well as the beloved, cat-endorsed black ink: still marketed as the “Standard Black Ink of America.”

“Few inks have withstood the vicissitudes of time and usage as those which bear the Black Cat trade mark of the L. H. Thomas Company of Chicago,” American Stationer noted in 1908. “The quality of Thomas inks has been so often tested and found satisfactory in every particular that they rank today among the leaders and are constantly making more friends.”

Indeed, maybe “bad luck” never truly befell the L. H. Thomas Co., but instead, like many of us in middle age, they simply found it increasingly difficult to keep making new friends.

Indeed, maybe “bad luck” never truly befell the L. H. Thomas Co., but instead, like many of us in middle age, they simply found it increasingly difficult to keep making new friends.

It’s not clear exactly when Sanford officially elected to discontinue its Thomas products, but when William Rodiger died in 1915, he was identified only as the vice president of Sanford MFG, with no further mention of his prior involvement as the chief of L. H. Thomas.

Digging through the archives, we found the occasional brief mention of Thomas inks as late as the early 1920s in some trade publications, but with fountain ink pens rapidly evolving and bottled inks disappearing from shelves, the Black Cat soon returned to the shadows, as well.

Sometimes, if you put your ear to an old antique stationery cabinet, they say you can still hear Thomas’ Black Cat meowing its clarion call: “Ask for Me! Ask for Me!”

SOURCES:

“The Thomas Ink Company” – John Hinkel, Rogers Park / West Ridge Historical Society

“The L. H, Thomas Company” – The American Stationer, Aug 21, 1890

“L. H. Thomas Company’s Inks” – The American Stationer, March 17, 1892

“The most recent imported accession . . . ” – Chicago Tribune, April 17, 1880

“At Rogers Park” – Chicago Tribune, Feb 27, 1881

“Activity at Rogers Park” – Chicago Tribune, March 26, 1882

“Carter vs Alling” – The Federal Reporter, June 30, 1890

“Paper Bottles” – The American Stationer, Nov. 5, 1885

Chicago Correspondence – The American Stationer, Feb 8, 1894

“Paper Bottles: The Business of Manufacturing Them Ceases for Some Reason” – Buffalo Courier, Sept 11, 1893

“The Paper Bottle Company, LTD” – The Times (London, UK), May 7, 1887

“Thomas Inks” – The American Stationer, March 28, 1908

“Thomas Inks” – The American Stationer, August 17, 1907

“Correspondence” (Citizen Editorial) – The Hillsdale Standard (Michigan), May 14, 1878

History of Hillsdale County, Michigan, 1879

“A New Idea for Ink Bottles – Paper,” by Ed & Lucy Faulkner, Bottles & Extras, Fall 2006

Evanston Directory, 1888

Cook County: Rogers Park 1891 Map, Central Map Survey and Publishing Co.

“A Superior Ink” – L. H. Thomas Letter, The Times (Shreveport, LA), March 17, 1878

I have a bottle that looks like the Snowflake Paste bottle . It has the LH THOMAS CO CHICAGO on the bottom of the bottle, with the #846. It unfortunately has no lid or label.

I was gifted a glass flash light bottle that has an orange metal lid with gold print that says it’s Thomas’ Photo Paste Flash light bottle. The top of the metal lid has a black cat and the words The Standard Inks of America Ask for me. The bottle is heavy clear glass with a triangular space in one area inside the bottle. On the bottom it says L H Thomas Company Patented May 15 1900 with the number 839. I was reading the 33 page article and found the history very interesting. The bottle I have isn’t pictured anywhere in your article so may just be a reproduction. Made me curious. Is there anyone interested in getting this bottle for their archives? I like things to go back to whence they came for future generations to enjoy. Thank you and I will look forward to hearing from someone.

I have an antique bottle no label with LH Thomas company on the bottom and Thomas inks on the top. Would you like to have the bottle?