Museum Artifact: Admiral Deluxe Table Radio, 1955

Made by: Admiral Corp., 3800 West Cortland Street, Chicago, IL [Hermosa]

“Here’s a radio you’ll get a tremendous thrill out of owning! So smart, with its golden-mesh metal grille and dial . . . so contrasting in choice of Ivory, Beige, Green or Mahogany cabinet colors. So low-priced for the performance it gives! This is the new radio you have been looking for!” —Newspaper ad for the $24.95 Admiral Deluxe Table Radio, 1955

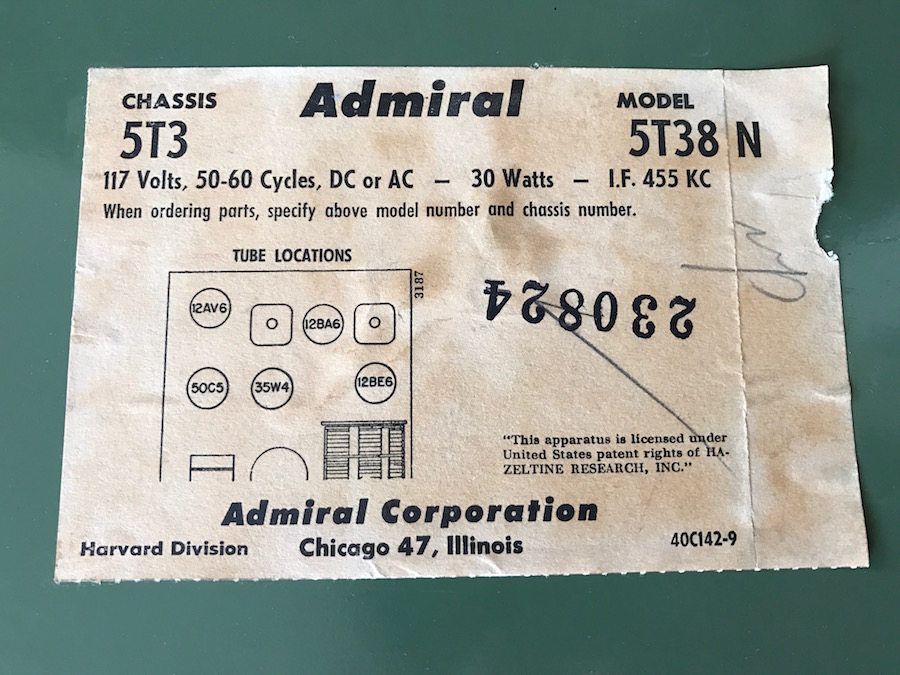

Looking like the electronics equivalent of a Buick Super Convertible, this mint-colored 1955/56 bakelite radio includes a 6-inch Alnico speaker, “printed circuit” chassis, five tubes for “long range performance,” and a few ghostly echoes of Fats Domino and Buddy Holly.

Looking like the electronics equivalent of a Buick Super Convertible, this mint-colored 1955/56 bakelite radio includes a 6-inch Alnico speaker, “printed circuit” chassis, five tubes for “long range performance,” and a few ghostly echoes of Fats Domino and Buddy Holly.

Its manufacturer, the Admiral Corporation, was a rock star in its own right by this point in time, employing more than 6,000 workers in the greater Chicagoland area, and producing a wide range of electric appliances, from record players and refrigerators to some of the earliest color television sets.

Radios, which had once been the company’s bread and butter in the pre-war years, had been a bit rudely kicked to the backseat as TV sales soared. Nonetheless, this particular model—serial number 5T38N—has a certain charm that suggests Admiral hadn’t started phoning in the audio end of its business just yet.

History of Admiral Corp, Part I. Ross the Boss

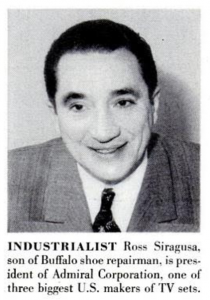

Admiral Corp’s fearless leader was its founder and president Ross D. Siragusa (1906-1996)—an Italian immigrant and son of a cobbler—who harnessed his own boundless curiosity to become one of the original, fresh-faced tech moguls of the radio age.

Admiral Corp’s fearless leader was its founder and president Ross D. Siragusa (1906-1996)—an Italian immigrant and son of a cobbler—who harnessed his own boundless curiosity to become one of the original, fresh-faced tech moguls of the radio age.

From early on, Siragusa was one of those kids who just enjoyed taking machines apart and putting them back together again—perpetually intrigued by the bones and marrow of good engineering. As a teenager, he had a summer job testing bell-ringing transformers at the Chicago plant of the Jefferson Electric Company. According to legend, though, young Ross soon got bored with his daily tasks, and started using the equipment for his own nerdy experiments, eventually leading to his dismissal. No worries! When you’re a budding teenage tech savant and you want to play with transformers (and we’re not talking Optimus Prime here), you might as well just start your own business. And that’s what an 18 year-old Ross Siragusa did.

Right after graduating from Loyola Academy High School in the summer of 1924, he launched the Transformer Corporation of America, using the back of his dad’s shoe shop as a “headquarters.”

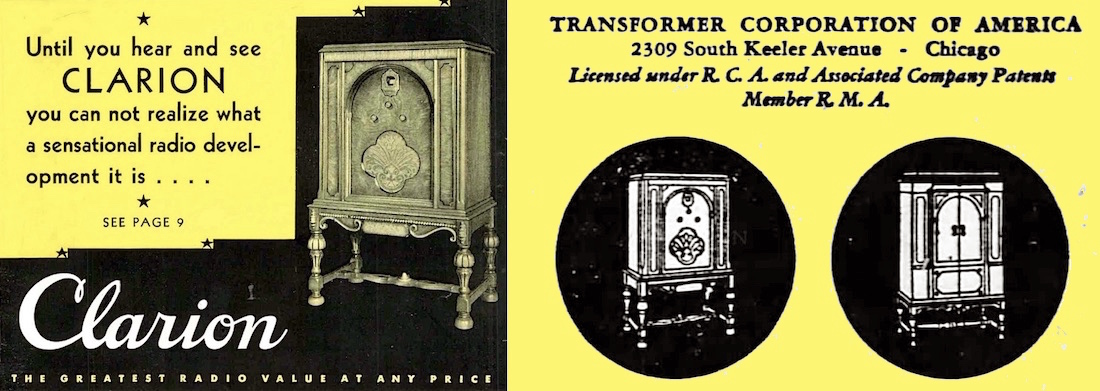

[Transformer Corp. of America ads, featuring the Clarion receiver, 1930]

[Transformer Corp. of America ads, featuring the Clarion receiver, 1930]

By 1929, as a testament to the kid’s ridiculous talents, the Transformer Corp. of America (by now located on the fourth floor of a factory at 2309 S. Keeler Ave. in North Lawndale) was already one of the biggest suppliers of radio parts in the world, and was starting to get into receiver production, as well, with its growing “Clarion” line. If not for the stock market collapse later that year, the company might well have maintained its course. Instead, the legs were cut out from under it, leading to slowing sales and bankruptcy by 1934. Siragusa—still just 28 years old—had to dig his way back to a new starting point.

“Ross tried to pay off all his creditors,” his cousin and eventual business partner Vincent Barreca remembered in a 2001 retrospective. “These were people who later became his suppliers in his future business. They were willing to sell to him again because of his honesty and efforts to pay them back.”

Showing an incredible degree of business savvy for a guy who’d never really worked his way up the ranks nor spent a day in college, Siragusa quickly got his ducks in a row for a second crack at the big time. This time, instead of focusing on parts for traditional radio cabinets, he’d take aim at the affordable, portable radio market—while also keeping an eye on that wondrous new technology he’d seen at the 1933 World’s Fair. . . the television.

[Admiral / Continental Radio ads from 1939, as the company began using it’s famous slogan: “America’s Smart Set”]

[Admiral / Continental Radio ads from 1939, as the company began using it’s famous slogan: “America’s Smart Set”]

II. Continental Drift

Selling off most of his own possessions, Siragusa scrounged together $3,400 in capital, $5,000 in equipment, and the use of a friend’s garage, thus beginning his new venture, the Continental Radio & Television Corporation. Admittedly, there wasn’t much fanfare. It was 1934, and nobody had the scratch to buy big ticket electronic appliances. Rather than seeing that as an impediment, however, Siragusa shot for the working and middle class markets, developing products that could be made cheaply and sold at lower prices than those made by RCA or fellow Chicago-based suppliers like Zenith and Motorola.

In 1936, he also bought the “Admiral” trademark for a song ($200), and made it his first flagship brand. The name earned such a stellar rep that it eventually became the official identity of the company after World War II.

In 1936, he also bought the “Admiral” trademark for a song ($200), and made it his first flagship brand. The name earned such a stellar rep that it eventually became the official identity of the company after World War II.

“Product development was my father’s strongest suit,” his son and successor Ross Siragusa, Jr., recalled in 2001. “He excelled at conceiving products with the proper appeal and offering them at the right price points. His business philosophy was: ‘sell a lot at low profit margins and low overhead. Make your profit on volume. This approach worked fairly well for awhile, until our competitors began to catch up.”

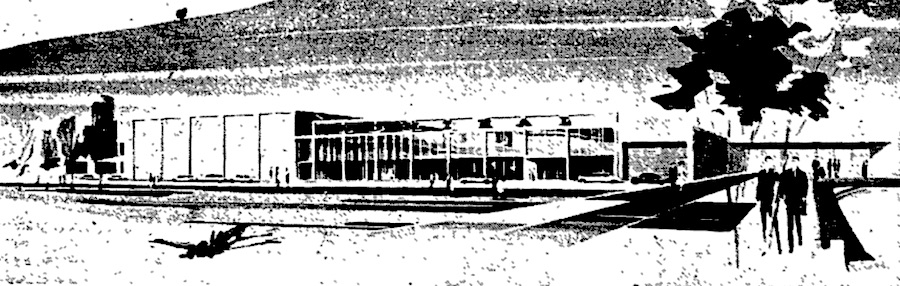

From 1937 to 1974, the primary Chicago plant for Continental/Admiral was located at 3800 West Cortland Street—one of the many factories strategically positioned along the old Bloomingdale train line (including Schwinn Bicycles, Ludwig Drum Co., and Playskool). The factory was dramatically expanded in 1964, but ultimately left behind a decade later. It was leveled in the 2000s, and the Marine Leadership Academy at Ames stands in its place.

[This 1964 artist’s conception of the expanded Admiral Corp headquarters, which stretched along Hamlin Avenue between Cortland St. and Armitage Avenue, is frustratingly the only “image” of the plant I’ve managed to unearth thus far]

[This 1964 artist’s conception of the expanded Admiral Corp headquarters, which stretched along Hamlin Avenue between Cortland St. and Armitage Avenue, is frustratingly the only “image” of the plant I’ve managed to unearth thus far]

III. Meeting Change

The Continental Radio and Television Corp., despite its name, didn’t sell TV sets in the years before the war. Video technology still demanded an enormous cost in parts, and it simply wasn’t practical to roll out to the public en masse, particularly with the Depression carrying on. Even so, the business did well enough in the radio trade to position itself for some profitable government contracts during the WWII, building related communications technology for the military. This boost gave Siragusa the flexibility to expand his overall production with an eye to peacetime, and eventually, the TV revolution.

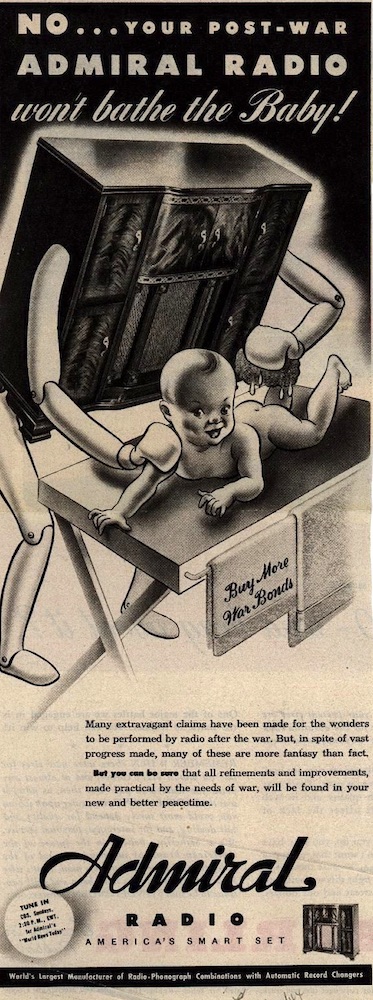

“When the war ended,” according to a 1949 company profile in the Des Moines Register, “Admiral started a massive advertising campaign long before it had reconverted to civilian production, to have a market ready for its products. The company cashed in, along with others, on the pent-up demand for radios. It did not enter television until February, 1948, but had spent 2 million dollars getting ready and came in with a splash.”

“When the war ended,” according to a 1949 company profile in the Des Moines Register, “Admiral started a massive advertising campaign long before it had reconverted to civilian production, to have a market ready for its products. The company cashed in, along with others, on the pent-up demand for radios. It did not enter television until February, 1948, but had spent 2 million dollars getting ready and came in with a splash.”

Within just a year and a half of entering the TV fray, Admiral was producing 15,000 sets a day (at multiple facilities across the country) and claiming nearly a quarter share of the entire industry’s production. According to Siragusa, they were also paying for 25% of the TV related advertising in the country, mostly in newspapers. But good marketing wasn’t the sole explanation for Admiral’s big breakout.

“We have,” Siragusa said at the time, “the most efficient factory and plant organization in the country, giving our sales department the lowest cost in the industry. . . . If we see signs of price cutting, we move right in. If we feel a model is laying an egg, we cut it right off. Like other companies, we set up production schedules for our various models. But if we find one is going over better than expected and another is backing up on us, we revise our schedules—and fast.”

Having started his career in the early days of radio, Siragusa was uniquely qualified to guide a business through the land mines of an unpredictable new technology. Quick pivot points and confident decision making, clearly, were vital within an “ever changing situation,” but he also knew that trend chasing could lead to dead ends without a consistent emphasis on quality.

“We go overboard,” Siragusa said, “on the extent to which sets are peaked for maximum performance on all channels. The tolerances are a little narrower—more sets probably are rejected at the end of our assembly line than any other in the industry.”

[Workers at an Admiral factory in Bloomington, IL, 1956]

[Workers at an Admiral factory in Bloomington, IL, 1956]

As the TV era exploded in the 1950s, workers at the Cortland Street plant—and an ever increasing network of satellite facilities—literally couldn’t keep up with the demand, particularly as the sets became more affordable, better functioning, and increasingly rich in programming content. Radios were useful and all, but the television was the new centerpiece of the home.

As reported in the Chicago Tribune, Admiral’s first quarter sales in 1950 increased by 97% compared to 1949. Siragusa, still a young buck at 44 years of age, was now a millionaire and one of the true bigwigs of American industry (the families of future Presidents Kennedy and Johnson both called him a friend). In the same Tribune story, he stated that production of TVs alone would increase from 400,000 to more than a million in 1950. A reporter asked him if he had any concerns about that wave slowing down a bit.

As reported in the Chicago Tribune, Admiral’s first quarter sales in 1950 increased by 97% compared to 1949. Siragusa, still a young buck at 44 years of age, was now a millionaire and one of the true bigwigs of American industry (the families of future Presidents Kennedy and Johnson both called him a friend). In the same Tribune story, he stated that production of TVs alone would increase from 400,000 to more than a million in 1950. A reporter asked him if he had any concerns about that wave slowing down a bit.

“Last Friday night our distributors across the country had a total of 5,000 sets on hand,” Siragusa replied, “and we are shipping at a rate of 80,000 a month. Figure it out for yourself.”

Learning a lesson that the Notorious B.I.G. would so eloquently re-iterate some 50 years later, Siragusa—despite all the success—was in a bit of a “mo money, mo problems” bind in the early 1950s. To keep up with public demand, he had a second plant in Chicago at 4150 N. Knox Avenue, and gobbled up additional factory spaces in the nearby Illinois towns of Galesburg, Bloomington, and Harvard (the latter of which was the birthplace of our 1955 radio), employing over 6,000 workers in the region by 1953. There was an international push, too, with plants in Toronto and other markets.

The company that was scrounged together with just over $3,000 now had assets in the multi millions. All along the way, however, Siragusa’s ambition was still outpacing his means.

[Our museum radio was made at this former Admiral plant in Harvard, IL, at 320 S. Division Street. It was Admiral’s from 1947 to 1978, and is now a True Value distribution center. Photo: 2014]

[Our museum radio was made at this former Admiral plant in Harvard, IL, at 320 S. Division Street. It was Admiral’s from 1947 to 1978, and is now a True Value distribution center. Photo: 2014]

IV. Hail Caesar

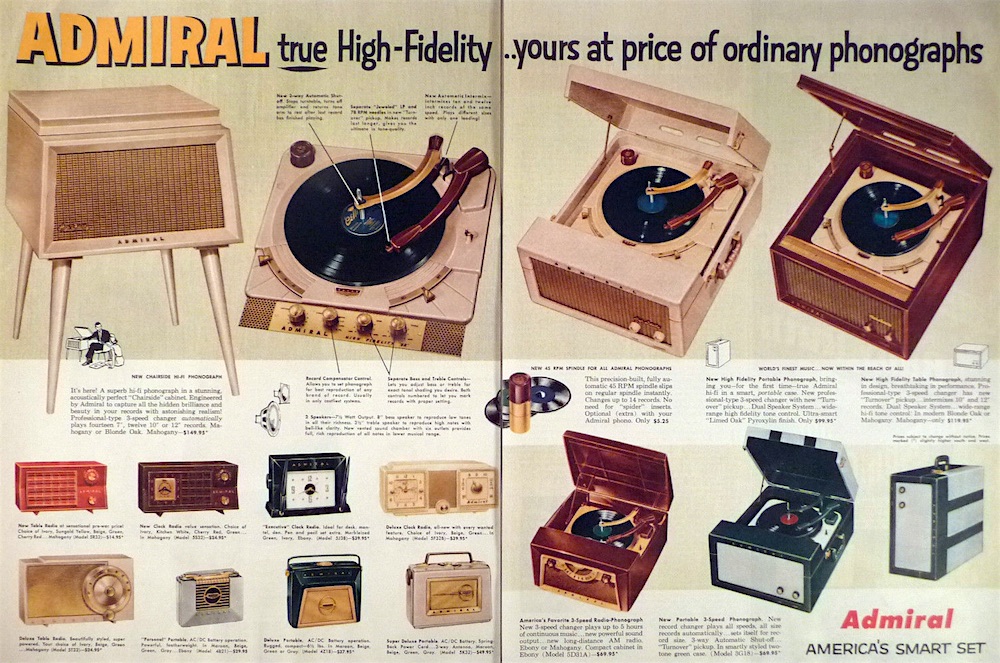

Beyond standard TV and radio, Admiral was stretching into new combination record player / radio cabinets and even refrigerators, electric stoves, and other kitchen appliances.

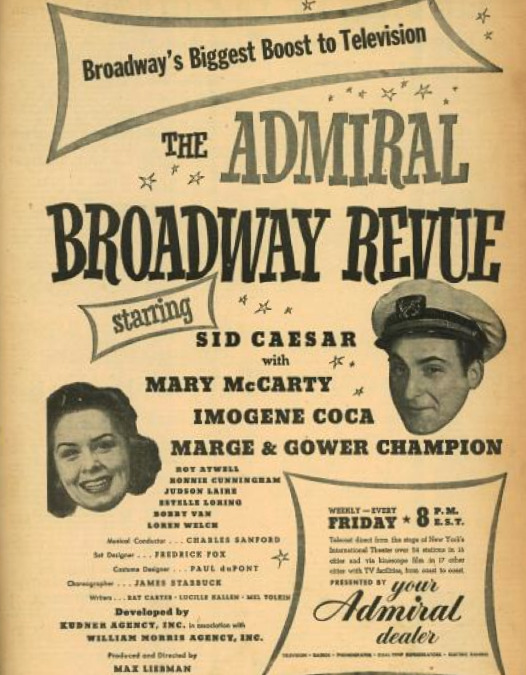

The company also jumped inside the world of television by sponsoring and producing programming, including some of the earliest televised Notre Dame football games (Siragusa was a proud Catholic) and an hour-long comedy hosted by Sid Caesar called the Admiral Broadway Revue—the precursor to the hugely influential Your Show of Shows.

The company also jumped inside the world of television by sponsoring and producing programming, including some of the earliest televised Notre Dame football games (Siragusa was a proud Catholic) and an hour-long comedy hosted by Sid Caesar called the Admiral Broadway Revue—the precursor to the hugely influential Your Show of Shows.

With the latter program, Siragusa was going straight into enemy territory, paying for a show on the NBC network, which was owned at the time by one of Admiral’s biggest rivals, RCA. That’s not the reason the show was short lived, though. Not according to Sid Caesar anyway.

“The show ran on Friday nights, for nineteen weeks, from February to June 1949,” Caesar recalled in his memoir Caesar’s Hours: My Life in Comedy. “I thought we were doing well, both critically and with the audience, and suddenly Admiral withdrew its sponsorship. I couldn’t believe it.

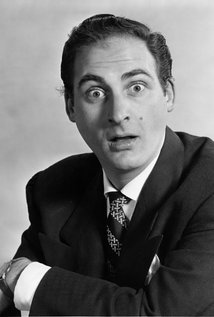

“. . . It was only after the season that I learned the truth. That summer I had a two-week engagement at the Chicago Theater, where I was held over for eight weeks. I got a phone call from Ross Siragusa, the president of Admiral. He invited me to come over and have lunch with him. ‘I think I owe you an explanation as to why the Admiral Broadway Revue was canceled.’[Photo Below: Sid Caesar, 1950s]

“I will never forget him telling me that the show was so popular that Admiral could not keep up with the demand for television sets that the program generated. When the show first began, Admiral had been producing 50 to 100 sets a week, and selling the same number. The popularity of the show caused business to pick up, and within months orders skyrocketed to 5,000 sets a day! He was beyond what he could produce” [Sid’s numbers might be exaggerated just a tad, but he was a comedian, not an accountant].

“I will never forget him telling me that the show was so popular that Admiral could not keep up with the demand for television sets that the program generated. When the show first began, Admiral had been producing 50 to 100 sets a week, and selling the same number. The popularity of the show caused business to pick up, and within months orders skyrocketed to 5,000 sets a day! He was beyond what he could produce” [Sid’s numbers might be exaggerated just a tad, but he was a comedian, not an accountant].

“The company was faced with a choice: it could continue to sponsor the show, or it could take that money and build a new factory. Siragusa told me that they had decided to build a new factory, and that’s why the show was killed. ‘You mean the show was too good?’ I asked. ‘Yes,’ he said. ‘It was a little too rich for our blood.’ The Admiral Broadway Revue was and is probably the only show in history to be canceled because it was too successful.”

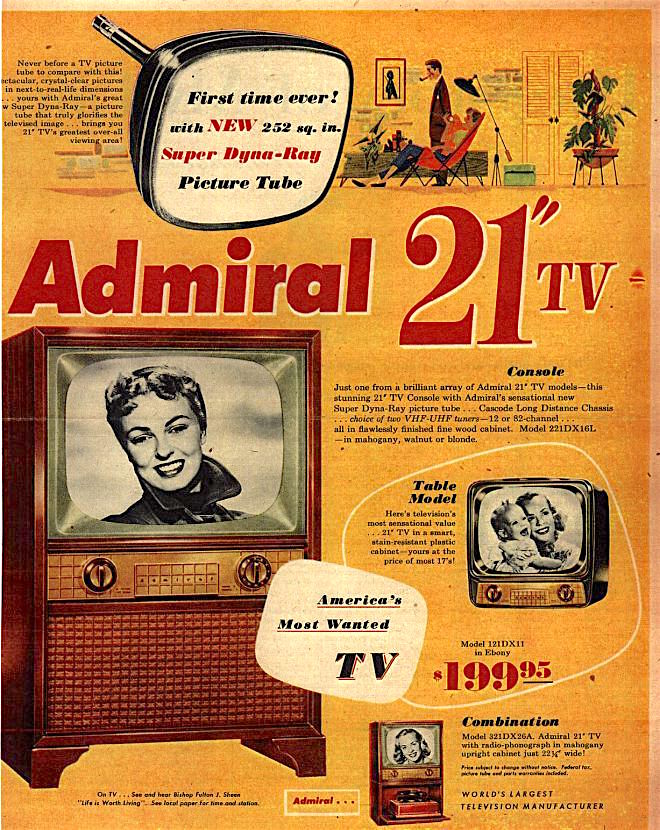

In the early 1950s, a 20-inch black-and-white Admiral TV with a cabinet would sell for around $150—a lowball price at the time, but not exactly “cheap” (it’s equivalent to about $1350 in modern money). The company’s earliest forays into color TV in the late ‘50s, meanwhile, cost closer to $1,000 a pop (or $8,000 with inflation), which gives you a good idea what a crazy magical box people perceived such a thing to be at the time.

[Admiral magazine ad for a TV combo set from 1951]

[Admiral magazine ad for a TV combo set from 1951]

V. “Get to the Bottom Line”

Ross Siragusa was often on the front lines as television manufacturers repeatedly battled with industry regulators in the ’50s and ’60s. Rapidly changing norms in the medium—from UHF compatibility to colorization—could render huge inventories obsolete overnight, so even small decisions by the FCC and other organizations could demand a challenge. The admiral of Admiral was certainly capable of being a fiery customer when he needed to be, but by most accounts, he was also a charmer; more likely to wine and dine someone or entertain them with impromptu piano concerts. He was famously charitable, as well, creating the Siragusa Foundation in 1950 (before it was trendy). It’s still in operation today.

In the boardroom, meanwhile, Siragusa was described as stern but fair—and always interested in new ideas.

In the boardroom, meanwhile, Siragusa was described as stern but fair—and always interested in new ideas.

“Ross had a very quick mind and would get impatient with rambling statements,” his former accountant Melvyn Schneider recalled. “He always said, ‘Get to the bottom line.’ You also learned to say what you meant within the first couple of lines of a letter or you would lose him. He was extremely honest, extremely reputable. He also was a tough businessman and never gave anything away, but the distributors and dealers all liked and admired him.”

When Siragusa retired in 1969, he’d built Admiral Corp. into an international giant with $400 million in sales and 14,000 employees globally. His son, Ross Jr., was installed in the role of president, but not surprisingly, retirement never quite suited Papa Siragusa. He butted heads with his son over the direction of the company in the 1970s, and by 1973, it was decided that the best move was to look for a buyer. Rockwell International Corp stepped up and acquired Admiral in 1974, but the deal didn’t prove particularly fruitful for either side, and most original traces of the Admiral empire were dispersed or liquidated by the 1980s.

The Admiral brand name, after some loop-de-loops, has survived, however, and is currently owned by Whirlpool, with some appliances sold exclusively at Home Depot.

Epilogue: Ross Siragusa’s Message to “Young America”

Ross Siragusa died in 1996 at 93. He had proved that a young kid could succeed by thinking like a grownup, and that an old man could stay sharp and successful by thinking a bit like a kid.

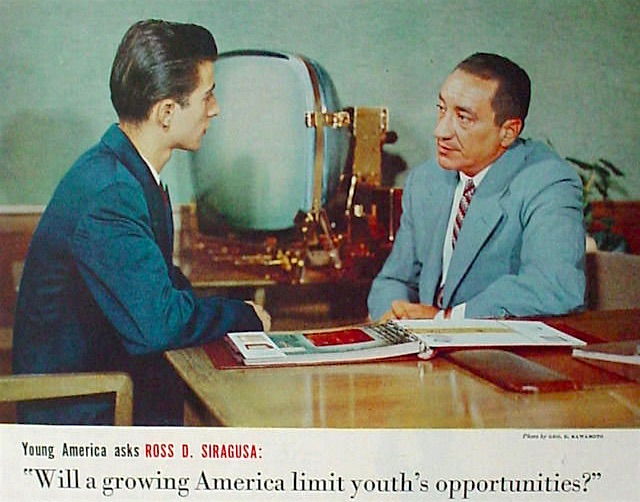

Back in 1953, Siragusa was interviewed at the height of his powers by an 18 year-old Chicago student for a small featurette in the Saturday Evening Post. He was essentially just asked one question: “Will a growing America limit youth’s opportunities?”

And this is how the self-made electronics giant—the Italian-American kid from Chicago, Ross D. Siragusa—responded:

“There will always be countless opportunities for ambitious youth in practically every industry in our nation. The size of America will never limit its opportunities.

“But young blood and fresh new ideas are a must for every phase of American business. Without these, opportunities will cease to exist and industries will cease to grow. A slow withering of our economy will follow.

“A fine example of American initiative is the electronics industry. It zoomed to importance during World War II with military applications. Then the postwar civilian introduction of television gave spectacular impetus to the growth and importance of this field.

“In less than seven years, television has absorbed thousands of young men and women in the manufacture of electronics equipment, in the operation of stations and the production of television programs. Hundreds of new stations will require additional operating and programming staffs. The electronics field alone will offer many opportunities for years to come.

“Youth should not be concerned because America is growing. On the contrary, youth should look to the future with enthusiasm . . . should prepare itself to take advantage of all the opportunities that will be extended in the great years ahead.”

The Artifact:

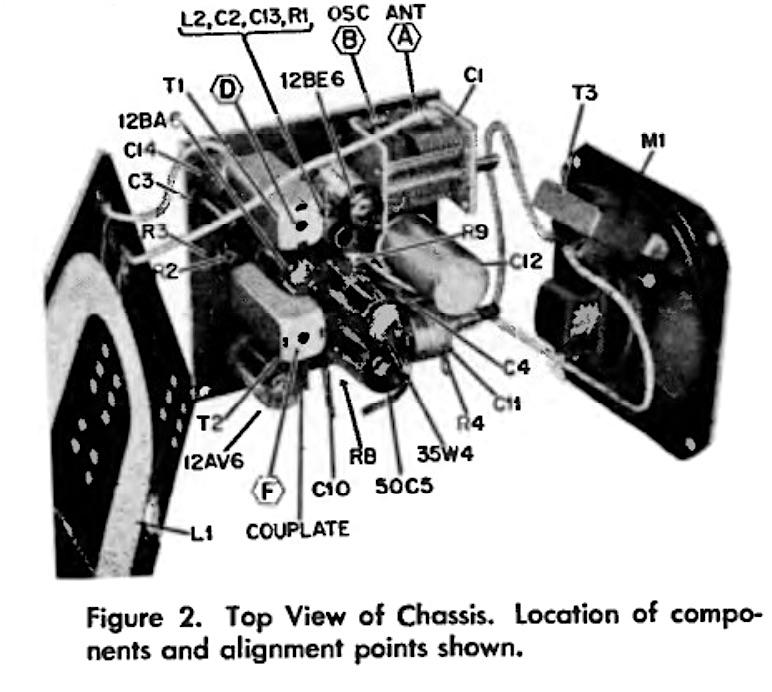

For any tech-inclined readers, here is a wee bit more about the 5T38N tube radio from our collection, from a 1955 Admiral manual referring to that model, among others:

“This receiver employs the latest radio circuitry and a ‘printed’ circuit wiring technique. The ‘printed’ circuit wiring used in this receiver replaces the hookup wire used in earlier receivers. The ‘printed’ circuit wiring is permanently bonded to the underside of the plastic chassis base. This results in uniformity of chassis wiring, fewer wiring troubles and simplified circuit tracing and trouble shooting. All circuit components are of standard size and design and are mounted on the top side of the chassis; see figure 2. Audio circuit components are contained in a couplate.”

[The Admiral Broadway Revue, 1949]

Sources:

Ross D. Siragusa Monograph, by the Siragusa Foundation, 2001

“Siragusa’s Success Story Behind Admiral’s Growth” – Des Moines Register, Oct 16, 1949

“Young America Asks Ross D. Siragusa” – Saturday Evening Post, Nov. 28, 1953

Caesar’s Hours: My Life In Comedy, With Love and Laughter, by Sid Caesar, Eddy W. Friedfeld

Cases in Competitive Strategy, by Michael E. Porter

Ross David Siragusa Obituary, New York Times, 1996

“Admiral Corp Net Earnings Soar” – Chicago Tribune, 1950

Archived Reader Comments:

“My dad, Robert Garner, worked at Admiral’s Cortland Ave. plant from the late ’40’s until 1969. He was from Virginia and found himself in navy basic training at Great Lakes during WW2. After the war he trained in Chicago with the Lee de Forest institute where he got his electronics background (he’d also been a radio-man in the navy). He was the guy at the end of the assembly line who checked out the products for proper performance before they went out the door. It was a union shop and he was a proud member of the IBEW during his time there. He had great respect and admiration for Ross Siragusa, who, according to dad, held the patent for the first multi-speed record turntable. . . . When I was little my folks had an Admiral combination TV-record player-radio set, a big floor standing model and a decent piece of furniture. For some reason they replaced it with a big Zenith TV and a Grundig console stereo. Wish I had the Grundig today!” —Paul Garner, 2018

My father, Robert Shan, also worked at Admiral in Chicago around 1968. 2nd shift. I believe he was a electronic technician. As a kid i remember lots of American brands including Zenith. This story brings back lots of nice memories.

Could the tension between Ross Siragusa Sr. and his son have been the real reason Admiral collapsed, rather than just market forces? Did the father’s inability to let go and the son’s leadership style create an irreparable rift that made the company vulnerable to a bad acquisition?

Is there a way to get a picture or the year Serial number 591590 model number YS8105 DL 7 Chassis No 23a7

I worked at Canadian Admiral at the Port credit Plant 1971-1973 in the white goods division (refrigerators). This was about the time Television was very competitive with Japan and our technology was lagging.

This was about the time Rockwell bought the company and things were going off in different directions. A consortium bought the Canadian division from Rockwell and it went bankrupt in 1981 because the consortium raided the coffers.

In my tenure at Admiral in the early 70’s when the company was run by Ross Siragusa Jr. it was still an economic powerhouse in Canada

About 20 years ago, I aquired a 1965-ish Admiral “Ensign” record changer through an internet sales/blog website.

This machine was still packed in its original shipping container, never installed in a product, and in absolutely perfect cosmetic condition, asides from needing fresh lubrication, and of course a new cartridge/needle.

It is a model rebranded as a Marsland M180, a company based in Canada.

However, it’s clearly an Admiral 2C7F1W.

I suppose that Marsland imported some Admiral equipment for their own products.

Well, after all this time, the poor record changer, never being used, will soon have a “home”, since I’m now a retired professional electronics service technician, and am custom-designing a small consolette stereo phono cabinet for it, along with a custom transistor amplifier, control panel, and including a pair of “aux” jacks for another audio source (cd, tape, tuner, mp3 player, etc).

The cabinet will be in a snazzy “mid-century modern” design standing on wrought-iron “spider legs”.

3/4 inch pine will be used throughout the cabinet construction.

Yes, woofers/tweeters at the ends of the 3 foot long consolette, each in their own chambers.

After custom designing 9 table radios and assorted other products, I think that Admiral record changer is entitled to finally show off its quite respectable performance for decades to come.

By the way, search youtube for the mid-1960s Admiral “Flight Deck” console stereo advertisement, now THAT was a masterpiece of engineering!

That caught my eye and showed how great American products could be.

I have a Admiral copper Freezer,Got this from my Aunt 10 years ago been using it till yesterday

when I noticed water on floor. To my surprise I caught everything in time to move all the frozen items to another freezer. I don’t and can’t find any info or drawing number (10EUF) Model Number (10U35) serial Number (2141087) the 1 after the 2 could be 7 can’t tell.

the wires are brittle in a round black block labeled Riverside Electric Dearborn Mich.Do I scrap the freezer or get parts to repair

I worked for Admiral, Government Electronics Division 2060 N. Kolmar, from 1968-73. We made electronic devices for the military like the ARC 51 aircraft radio which was used in the Huey helicopter.

Dave Tonkinson, me too Ron, also worked on the IFF Radar equipment there too.

I remember hearing Ross Seragusa on the radio in the 60s was he ever in politics.

My dad, Pete Pucci worked at the Courtland Ave plant after the war until they sold his division around 1977. He even met and married my mom Florence there!! We always had Admiral TVs and radios at home and our huge console color tv was around and working until the 90’s. I still have a console radio/record player he won in an Admiral golf outing when I was very young. All in all a great company!!!

1964 I was 17yo living in Beloit Wisconsin. Having graduated but had to be 18 to get a real job in WI, so crossed the border to Harvard to work at Admiral. My first introduction in the real working world. Wonderful memories.

I have an Admiral Slide/Light Viewer my husband bought new many years ago. I need to find a new light bulb for it but no one has one. Can you help me?

We have an Admiral Radio with a serial number of 1200828. Can you tell me a little about this radio please.

I’m looking for a refrigerator door gasket for a ruffly 1950 refrigerator does anyone still manufacture them or have any old stock?

I own a 12-17-1962 Admiral TV “THE MARQUETTE” model STF 2749A-serial 9473618 for $898.95. I like to know the value of this TV PLUS and where I can sell it. Everything works.

I have a share of Admiral Corporation stock that my father (Logan Grey) received (dated) Aug 19 1955. It is signed by Ross D Siragusa (President) and George E. Driscoll? (Secretary). Does this certificate have any stock value or other value?

The stock certicates have no financial value, but are small collector items, selling on eBay for $5-$10. I recently purchased a couple for my kids, as George Driscoll was their grandfather.

I have an Admiral Stereo For Sale. Turn Table. Radio. And Eight Track all works. Where would I sale?

I have an old Admiral television probably 1950. It still worked the last time I tried it. Do you have any interest in purchasing it?

Did Admiral ever have a newletter to their dealers? My Uncle was a dealer for Admiral and Curtis Mathes and seemed to have been winning trips back in the 60’s. I would like to find a source to find info.

I have a black/white. Tv (Admiral). Model t1811n, serial number 3127310. I am Curious when the set was made and what today’s value may be as a collectors item. It is in really really good shape.

I have an Admiral classroom television build date 1965, black & white rescued from a school being just days before it was to be demolished , they had a sale of the furniture in the gym , picked up the set for $ 10.00 in 1987. The set still works great, think any of the junk they make these days will ever last 55 years !.

Did Admiral ever publish a newsletter for the dealers? My uncle ran Mettille TV in Illinois about 1951 to 1970. I was told he would win trips from the company from his sales, and wonder if this information would have been published.

I am trying to Find out about an Admiral D-51 Serial No. 5674 to see what it could be worth or where it could be fixed.

Address was 2241 Indiana Ave . Chicago,il

I worked for an Admiral Distributor in St. Louis, Brightman Distributing, while in school, and joined Admiral as Field Engineer in 1969 working out of the Bloomington, IL location. Later, during the Rockwell era, I was Manager of Service Sales in the Schaumburg, IL. I stayed until we turned the lights out in 1979. It was a bittersweet time, with the Japanese invasion of the industry eventually destroying the US industry. I then went with GTE Sylvania serving as a Branch Manager in Detroit, Batavia NY, Boston, and then Chicago, witnessing the end of Sylvania also. To day China has it all much to our shame.

My father also worked for Admiral. He started in the late 30’s, the early days and remained until about 1970. I knew Mr Siragusa, RD was a common reference to his name. He was a guest at my wedding and shared a dance with my wife. I worked for one of his suppliers and participated in solving a problem with supplying perfectly round clamps for mounting convergent yokes to color tubes. RD gave me my first paid job, when the Galesburg factory had an employee open house I was asked to stand and point out the overhead conveyor system that moved refrigerators from the end of the production line across the highway to an automated warehouse. It was about 1960 and I was expecting to get a couple of dollars an hour which would have been great pay at the time. At the end of the day he gave me a $100 bill. He noted that he had been pleased that whenever someone had dropped a paper or left a can outside of the garbage I had picked it up and disposed of it properly keeping the area clean. He liked attention to the small details. People I know who worked for him all would say he was an SOB but fair. Never asking anyone to put out more effort than he himself would do. Same quality that was evident within his team and a quality I hope will be noted about me.

I have a radio built from admiral Corp and I was wanting to know how old it was I have a number here it’s 493382 I’m not sure if it will be any help, but any would be appreciated thank you!

I enjoyed your history of the Admiral Corporation. The depth and extent of your article was excellent!

It opened my eyes about the Company, and its founder.

Hello,

Do you know if George McCurdy of McCurdy Industries ever sold radio parts to Admiral?

McCurdy was a big manufacturer of radio equipment in the 50′ and 60’s.

Please let me know. Thank you!

Frith McCurdy