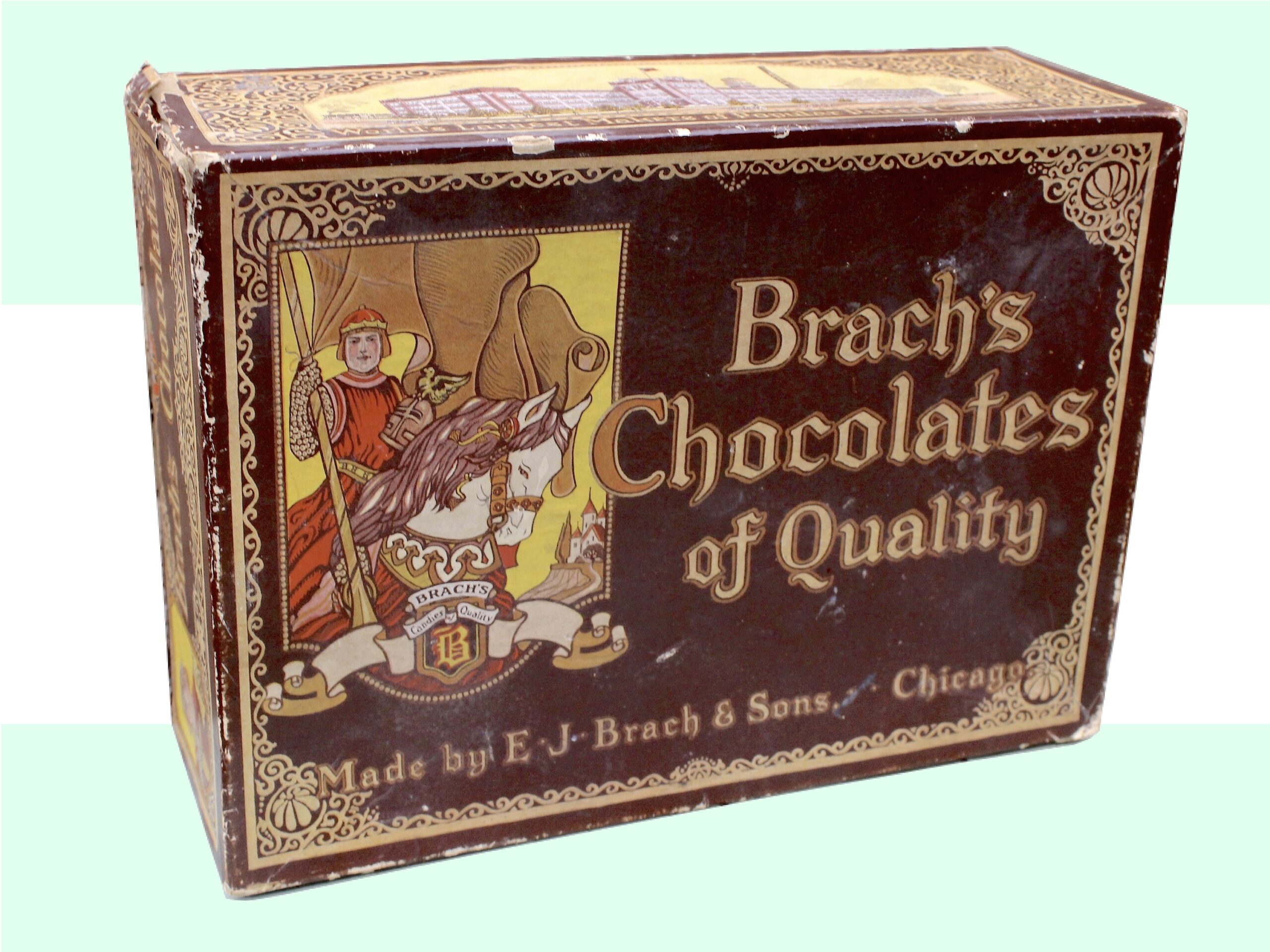

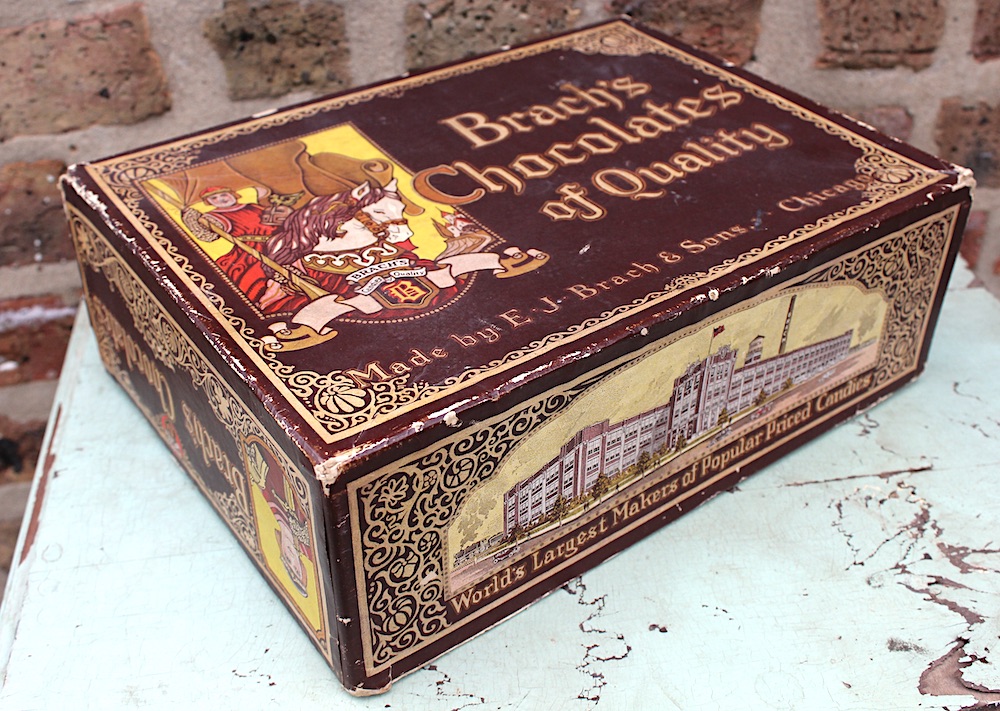

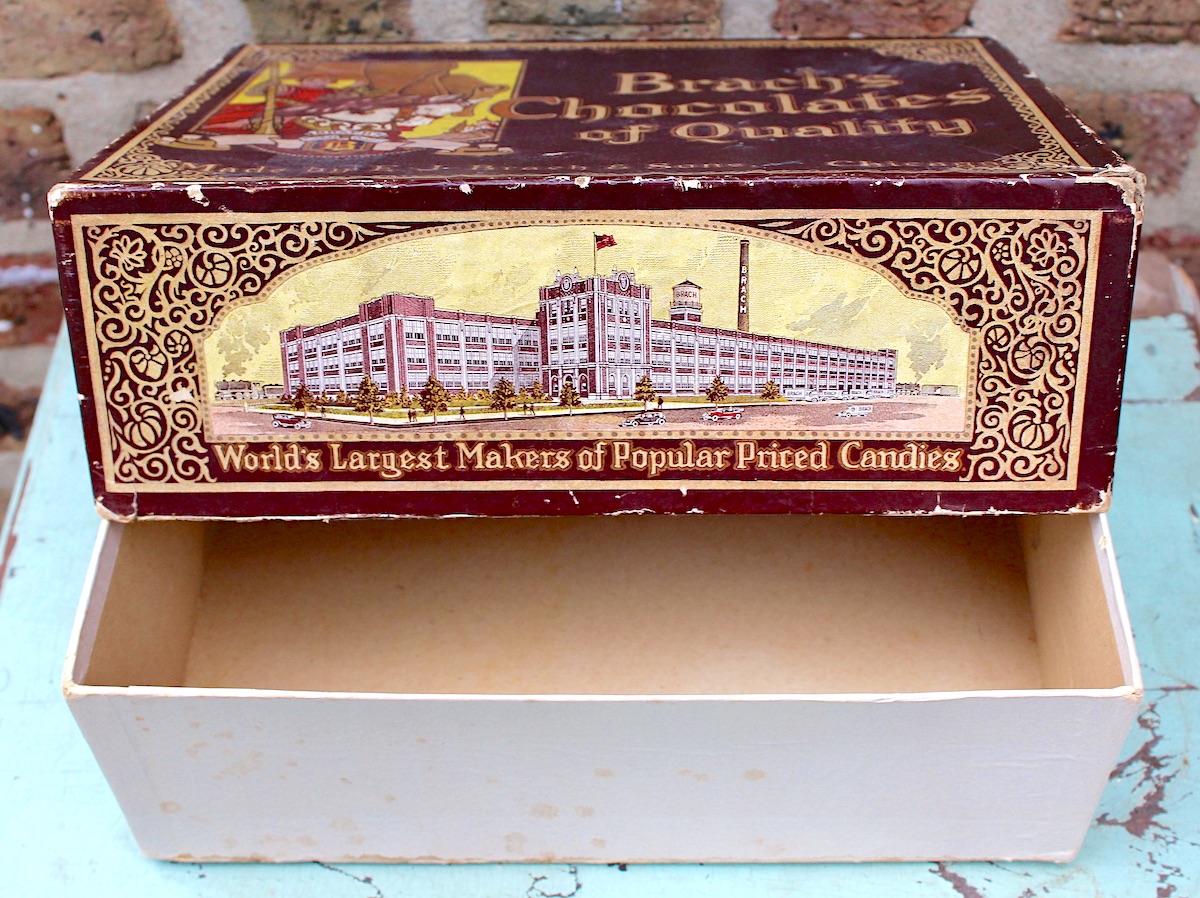

Museum Artifact: Brach’s “Chocolates of Quality” Box, c. 1920s

Made By: E.J. Brach & Sons, 4656 W. Kinzie Street, Chicago, IL [Austin]

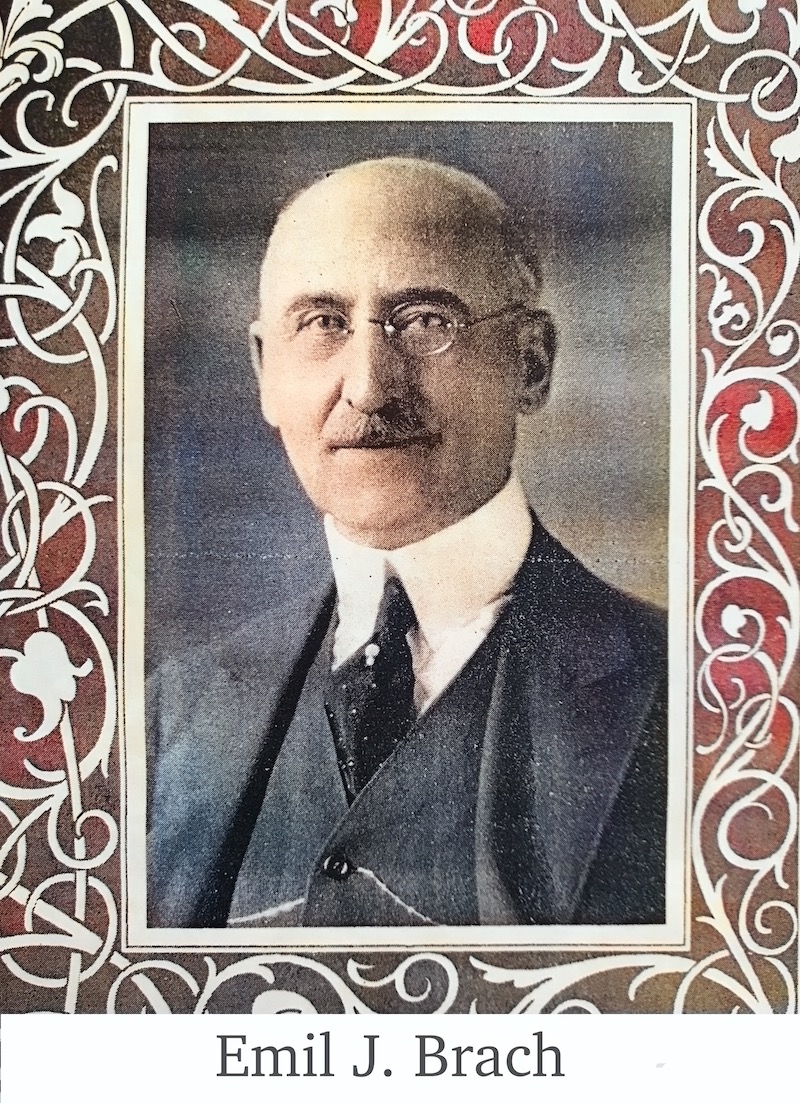

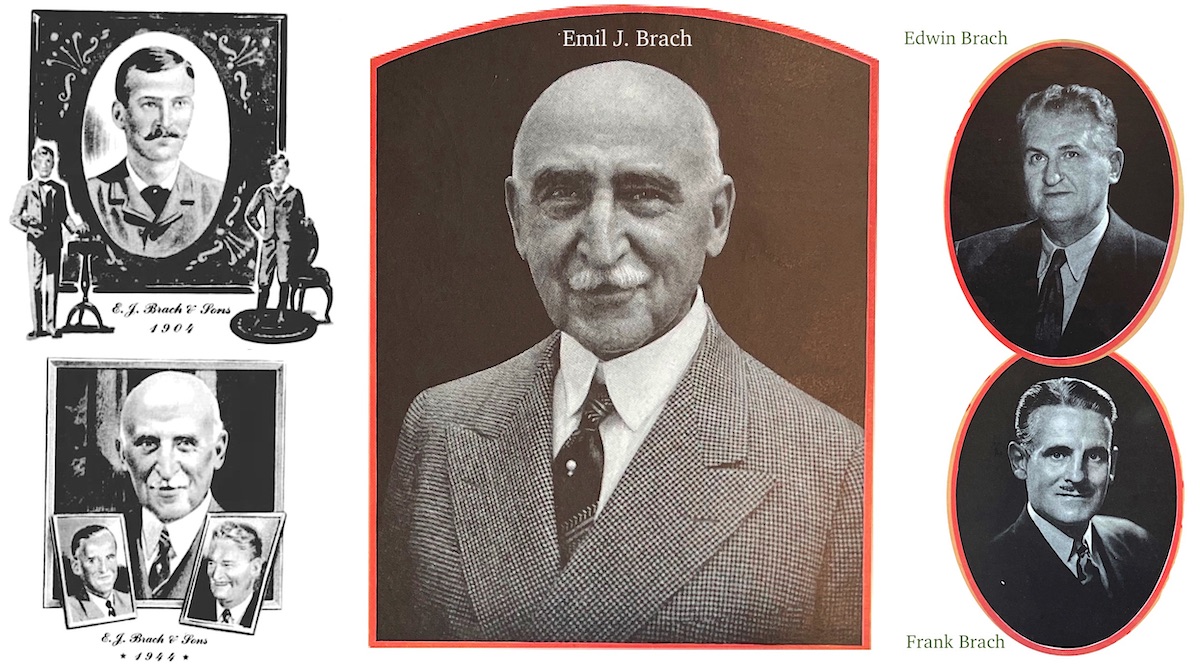

“When my sons and I opened a little candy store forty years ago, we hoped folks would like our candy. But we never dreamed they’d like Brach candies so well we’d outgrow our little ‘Palace of Sweets’ in just a few brief years. We didn’t dream that soon the Brach candy-kitchens would be among the finest in the world. However, over the years we’ve stuck to this aim—to make the best in candy and sell it at reasonable prices. And we’re proud that every year more people are asking for Brach candies.” —Emil J. Brach, founder and president of E. J. Brach & Sons, 1944

It’s probably a bit of a curveball to have Brach candies represented in our museum collection by a box of chocolates. While the company has certainly excelled in the art of the cocoa bean over the years (including a highly popular line of cherry cordials), its most significant contributions to the confectionery arts have always been those colorful little “pan candies”—i.e., Star Brite Mints, Butterscotch Disks, Milk Maid Caramels, assorted toffees, and that polarizing Halloween staple, candy corn (aka Indian Corn or Harvest Corn). In other words . . . the treats that were purchased in bulk and sporadically picked out of a tray on your grandparents’ coffee table.

It’s probably a bit of a curveball to have Brach candies represented in our museum collection by a box of chocolates. While the company has certainly excelled in the art of the cocoa bean over the years (including a highly popular line of cherry cordials), its most significant contributions to the confectionery arts have always been those colorful little “pan candies”—i.e., Star Brite Mints, Butterscotch Disks, Milk Maid Caramels, assorted toffees, and that polarizing Halloween staple, candy corn (aka Indian Corn or Harvest Corn). In other words . . . the treats that were purchased in bulk and sporadically picked out of a tray on your grandparents’ coffee table.

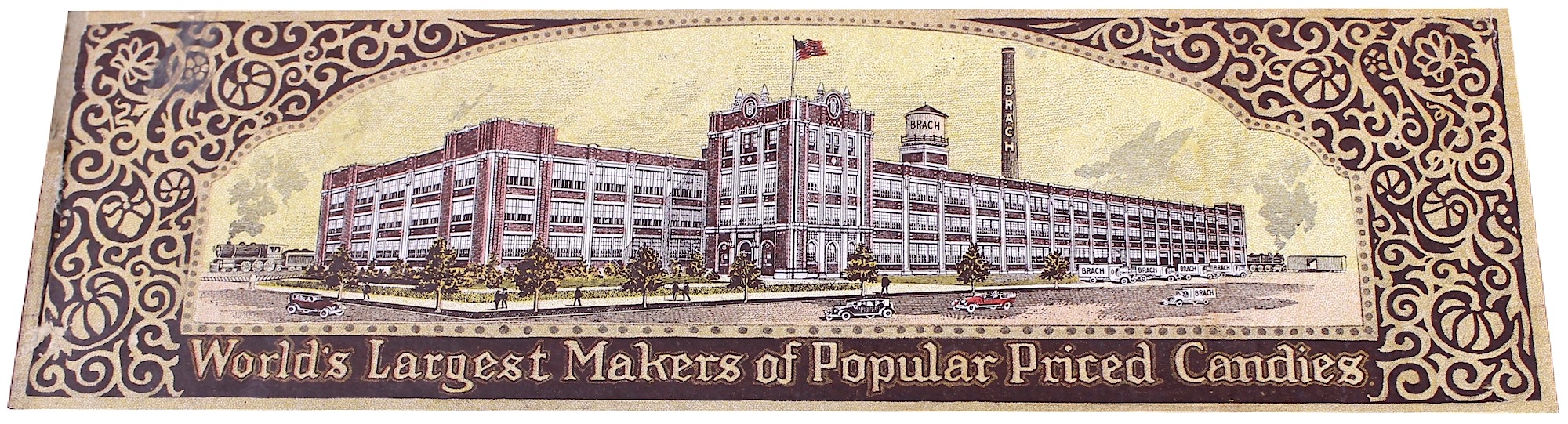

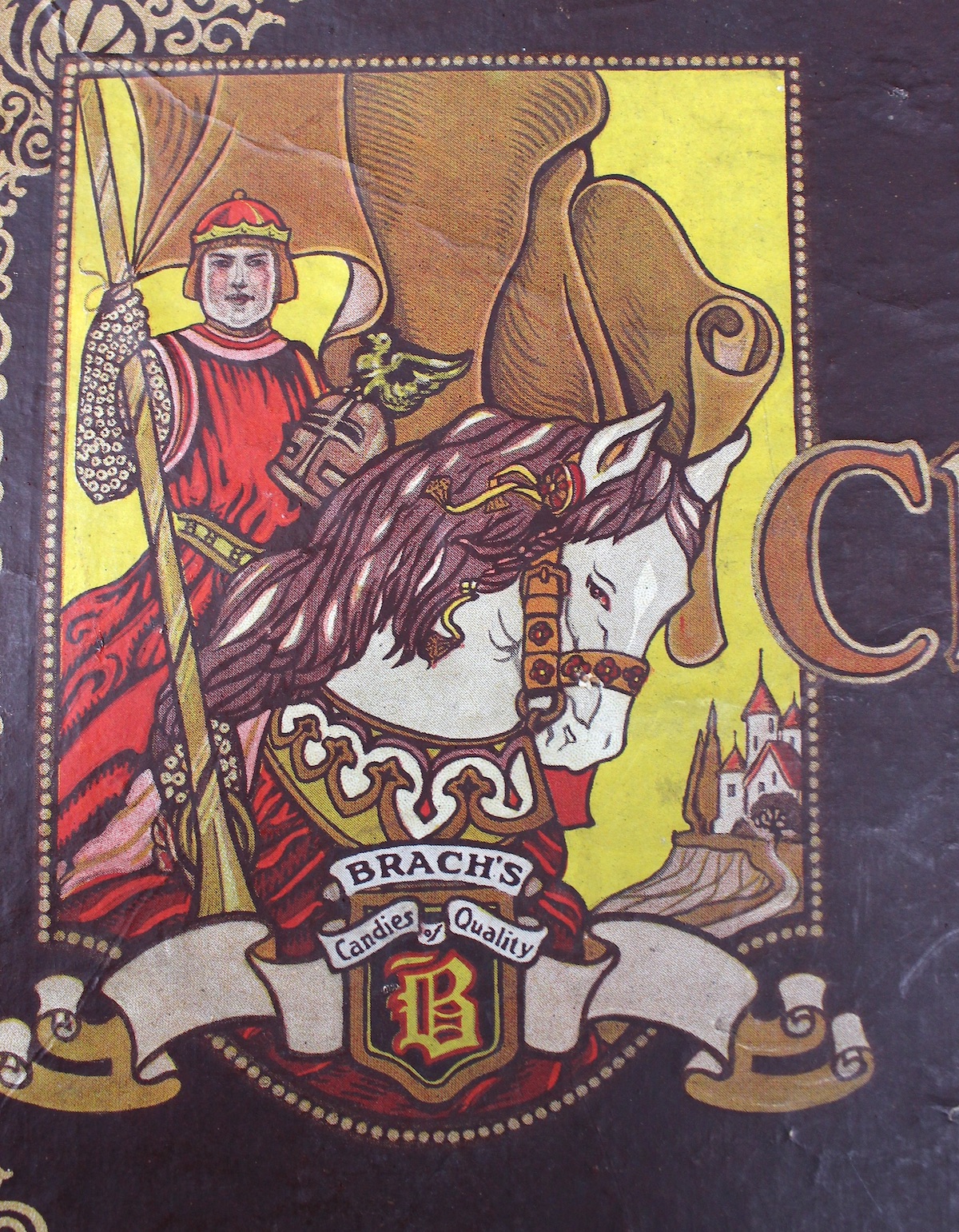

It’s less clear which specific delights would have been included among Brach’s lesser-known “Chocolates of Quality,” but we know the box in our collection actually contained “Creamy Maple Walnuts,” according to a stamp on the side. We also know that it dates back to the 1920s—judging not just by the prominent use of the company’s short-lived medieval knight mascot, but by the accompanying illustration of its still new mega-factory complex at 4656 W. Kinzie Street, nestled between the West Side neighborhoods of South Austin, Humboldt Park, and West Garfield Park.

Built for $5 million in 1923, the factory—once the largest candy manufacturing plant on Earth—had reached a state of dilapidation by the time Brach’s Confections, Inc., finally announced its closure after 80 years, in 2003. That decision, which put over 1,000 Chicagoans out of work, also marked the end of the sweet maker’s sometimes bittersweet relationship with its hometown—a saga that included a deadly factory explosion in 1948 and the mysterious disappearance (and presumed murder) of matriarch Helen Brach in 1977.

[The Brach candy factory at 4656 W. Kinzie Street, as it appears on the chocolate box in our museum collection, circa 1925]

A few months after the shutdown of the Kinzie Street plant—despite doing $340 million in sales over the prior fiscal year—Brach’s was sold to a Swiss candy firm for the honest-to-gosh price of ONE U.S. DOLLAR . . . and a promise to cover all of Brach’s substantial outstanding debt.

If this great Chicago confectionary institution went out with a whimper, though, at least its proud old headquarters got more of a Hollywood ending. In October of 2007, part of the building was famously blasted to bits for a special effects sequence in the blockbuster Batman film The Dark Knight (Heath Ledger’s Joker can be seen casually strolling away from the burning administration building, which was standing in for “Gotham City Hospital”). The rest of the abandoned structure was finally demolished in 2014.

[The abandoned Brach factory’s administration building playing the role of a bombed out Gotham Hospital in The Dark Knight. Filmed in 2007, released in 2008.]

Brach’s candies, it should be noted, can still be found at your local supermarket, produced under the rebuilt banner of another historic Chicago confectioner, the Ferrara Candy Co. Tracing the confusing line of different mergers and conglomerations that have shuffled around the Brach brand in recent decades, however, is less important to our concerns than the original father-and-sons operation that put it on the map.

History of Brach’s, Part I: The Palace of Sweets

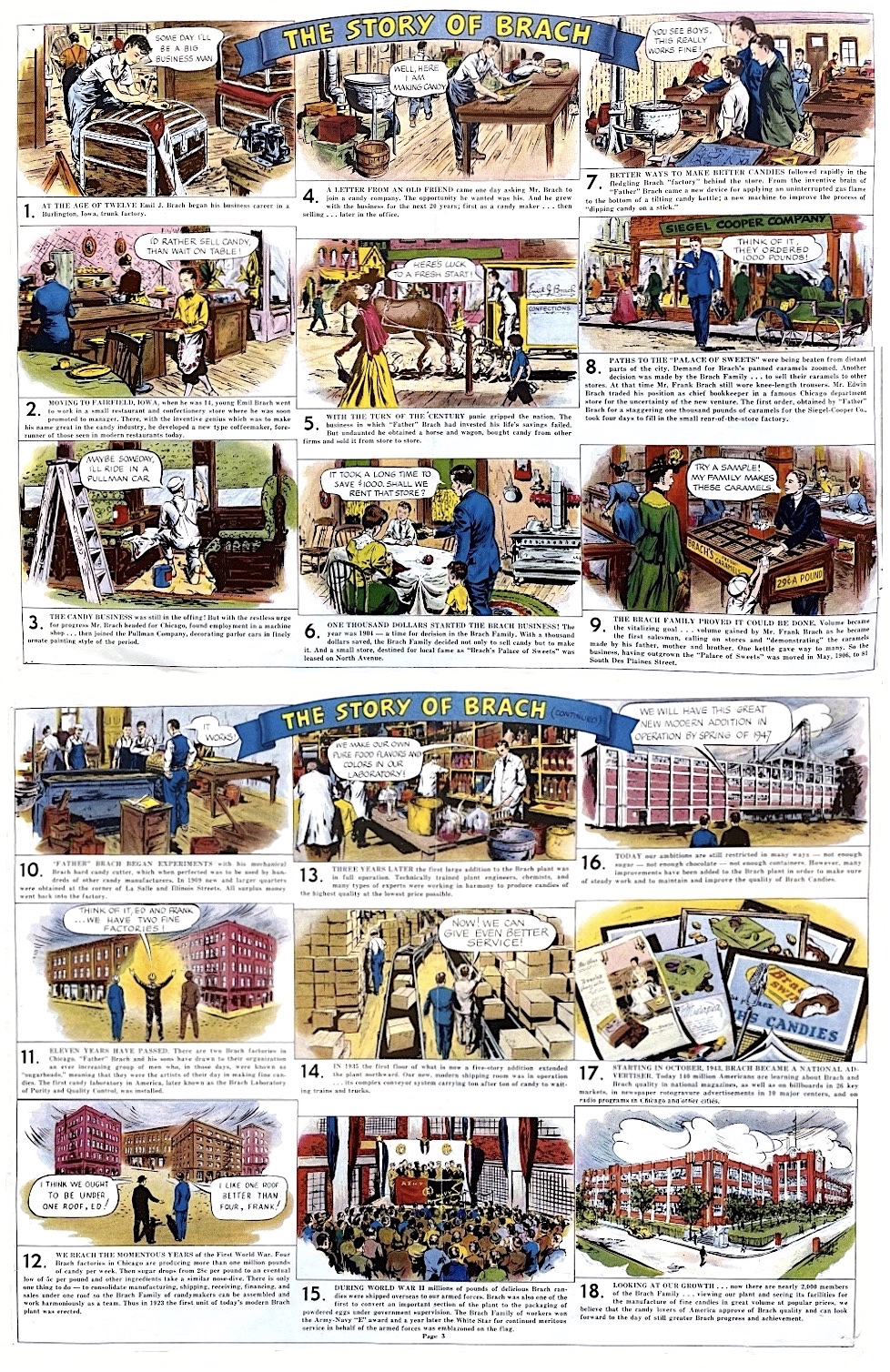

Emil J. Brach is the sort of character that ought to be familiar to anyone who has read more than a few of the company histories in the Made In Chicago Museum—being another example of the persevering, mechanically-minded German immigrant.

Born in 1859 in a small village in Deutschland’s Black Forest, Emil immigrated to America with his family as a small child, settling in Burlington, Iowa. He was working in a trunk factory by the age of 12 (as one often does), did janitorial tasks to pay his way through the Burlington Business College, and by the age of 18 was already managing a general store in Fairfield, Iowa. In the latter job, Brach became acquainted with a traveling salesman named Charles Spoehr, then a representative for the heralded Chicago candymaker John M. Kranz. A good impression was made among the fellow Germans, and by the time Emil moved to Chicago to pursue factory work in 1881, Spoehr tracked him down and offered him a more appealing gig in the offices of his own new candy firm, Bunte Brothers & Spoehr.

Born in 1859 in a small village in Deutschland’s Black Forest, Emil immigrated to America with his family as a small child, settling in Burlington, Iowa. He was working in a trunk factory by the age of 12 (as one often does), did janitorial tasks to pay his way through the Burlington Business College, and by the age of 18 was already managing a general store in Fairfield, Iowa. In the latter job, Brach became acquainted with a traveling salesman named Charles Spoehr, then a representative for the heralded Chicago candymaker John M. Kranz. A good impression was made among the fellow Germans, and by the time Emil moved to Chicago to pursue factory work in 1881, Spoehr tracked him down and offered him a more appealing gig in the offices of his own new candy firm, Bunte Brothers & Spoehr.

At 22, Brach appeared to have gotten his big break, but it would actually be another 20 years before his forays into the candy world really paid off. In the interim, he was more of a scuffling journeyman—becoming disenchanted with life as a salesman, then tanking financially in his first big effort to run his own candy business. That venture, the Dreibus-Heim Company (a partnership with Jacob G. Dreibus . . . we’re not sure who Heim was), started in 1896 and stumbled into the 20th century, eventually selling off its factory at 110 Clinton Street and all its machinery in 1908. From the looks of it, Emil jumped ship a few years before that, supposedly taking his last remaining $1,000 and investing it into a new sweet shop in Lincoln Park, run in partnership with nobody aside from his two teenage sons, Edwin and Frank.

[Emil J. Brach standing outside his “Palace of Sweets” on North Avenue, circa 1904]

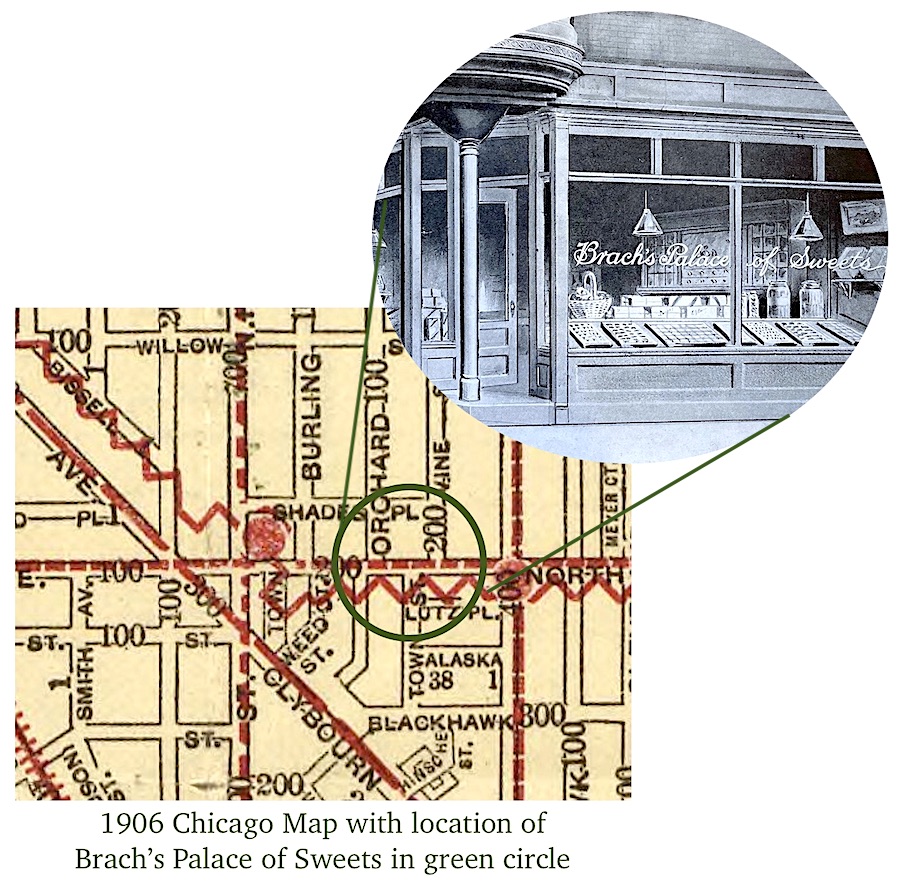

Pretty much every article ever written about E. J. Brach & Sons begins with a mention of that first, fabled Chicago storefront—the “Brach Palace of Sweets”—which is said to have opened in 1904 at the corner of North Avenue and Towne Street. It was “a hot day in October,” Edwin J. Brach later recalled about the shop’s first day. “We sold plenty of ice cream sodas at 5-cents each, but very little candy.”

Oddly, we couldn’t find a single reference to “Brach’s Palace of Sweets” in any newspapers of the period—although there were several other Chicagoland establishments using the exact same branding in the early 1900s, including “Mrs. Cummings’ Original Palace of Sweets” on the South Side at 330 W. 63rd Street.

The oft-described location of Brach’s shop at North Avenue and “Towne” Street also creates some confusion in retrospect, as turn-of-the-century maps reveal no sign of a Towne Street, but instead a pair of mini North Avenue offshoots called “Town Street” and a “Towns Court,” neither of which still exist. If the Palace of Sweets stood at the corner of North Avenue and Town Street in 1904, then it would have been a little east of Halsted, between what is now Orchard Avenue and Vine Street. Unsurprisingly, any building matching its description is also long, long gone, leaving us only with a solitary photo of a proud Emil Brach standing outside his establishment, probably in 1904. Beside him is a large sign reading, “Why go downtown for candy when you can get it here 25% less?”

The oft-described location of Brach’s shop at North Avenue and “Towne” Street also creates some confusion in retrospect, as turn-of-the-century maps reveal no sign of a Towne Street, but instead a pair of mini North Avenue offshoots called “Town Street” and a “Towns Court,” neither of which still exist. If the Palace of Sweets stood at the corner of North Avenue and Town Street in 1904, then it would have been a little east of Halsted, between what is now Orchard Avenue and Vine Street. Unsurprisingly, any building matching its description is also long, long gone, leaving us only with a solitary photo of a proud Emil Brach standing outside his establishment, probably in 1904. Beside him is a large sign reading, “Why go downtown for candy when you can get it here 25% less?”

Despite its legendary status in Chicago confectionery history, Brach’s Palace of Sweets was only actually in use for about a year and a half. But in that time, a 42 year-old Emil Brach finally seemed to find his niche, brainstorming a string of significant innovations for the candy industry—not so much in terms of flavors and concoctions, but more classically German principles like efficiency and automation.

[Inside the 18×25 foot backroom at the Palace of Sweets, where Emil Brach (mustache and hat), his son Edwin (back to camera), and a small staff worked on more efficient ways to make its most popular sweets, c. 1905]

II. From the Palace to the Plant

Rather than displaying some sort of intuitive genius, Emil Brach simply looked back on the hard lessons of a 25-year career and used them as an advantage over some of his younger competitors in Chicago’s cutthroat candy marketplace.

“Although a hard worker, [Brach] began to see that labor, alone, is far too costly to permit any great merchandising success for the manufacturer,” read one account in the 1925 company history, The Story of Brach. “So he began to devise methods and devices to decrease the amount of hand labor required, and to increase volume of production. This he knew would permit ‘price,’ the basis of merchandising.”

“Although a hard worker, [Brach] began to see that labor, alone, is far too costly to permit any great merchandising success for the manufacturer,” read one account in the 1925 company history, The Story of Brach. “So he began to devise methods and devices to decrease the amount of hand labor required, and to increase volume of production. This he knew would permit ‘price,’ the basis of merchandising.”

Among the “mechanical contrivances” Brach experimented with in the tiny backroom of the Palace of Sweets were a dipping machine for “taffy-on-a-stick”; a candy kettle powered by a perpetually operating gas burner; and a simplified method for making soft and chewy caramels on heated pans.

The pan caramels, which Brach was able to sell in bulk at half the cost of most other shops in town, were really the launch-point for the business, transforming it overnight from a small retail establishment into a rapidly growing wholesale manufacturer—inking contracts with many of the big department stores in town. It didn’t hurt that Emil Brach’s sons seemed to be financially-minded wunderkinds in a way he never had been.

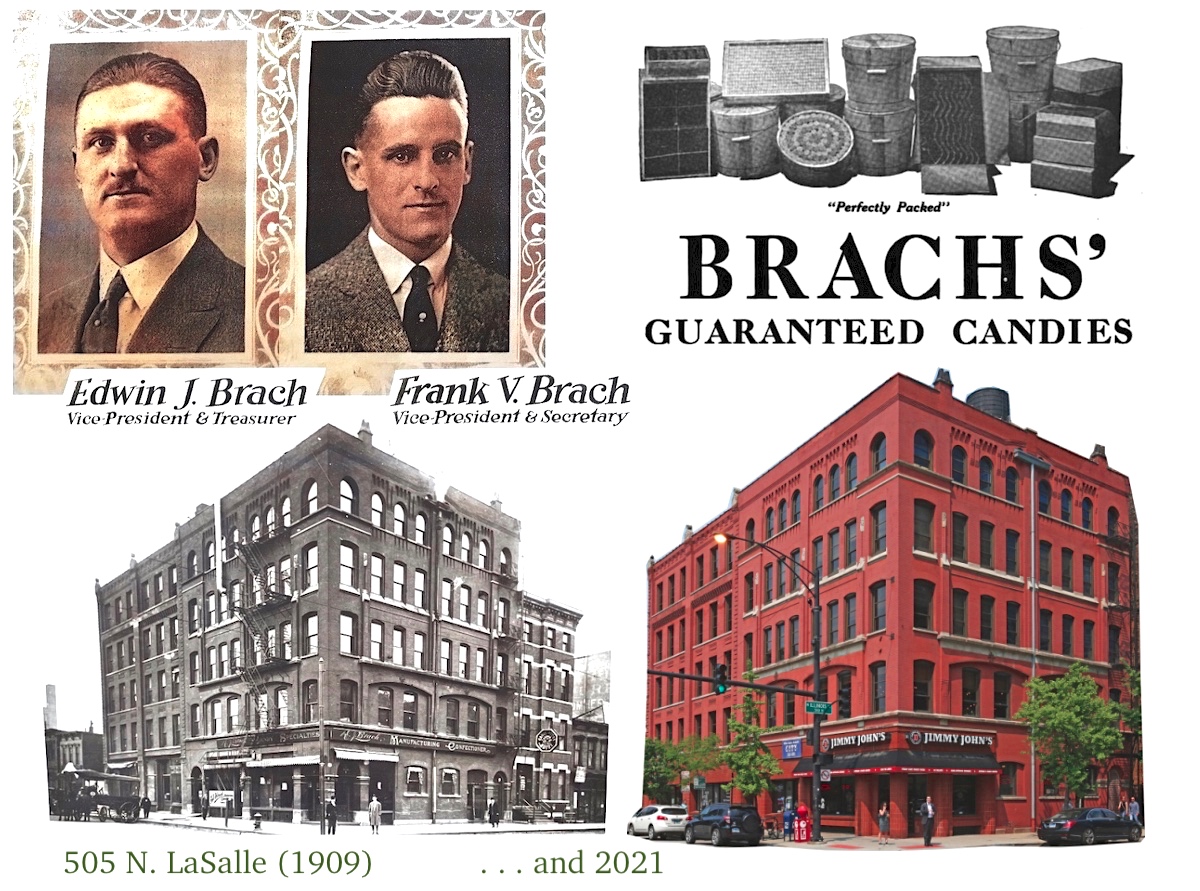

Edwin J. Brach (b. 1887), who’d also worked as a bookkeeper for Marshall Field & Co. before turning 20—easily transitioned into a role as the capable administrator of E. J. Brach & Sons. His kid brother Frank V. Brach (b. 1890)—who was still just 16 years old when the family business acquired its first factory space in 1906—was the face of the company in many respects, first manning the till at the Palace of Sweets, then leading the first sales team of the wholesale operation, driving caramel-filled wagons around the city.

In the spring of ’06, Brach Confections relocated to a much larger three-story headquarters at 81 S. Desplaines Street, where peanut and hard candies were added to the arsenal, and weekly output quadrupled from 3,000 LBS to 12,000 LBS. This would look like a drop in the bucket in due time.

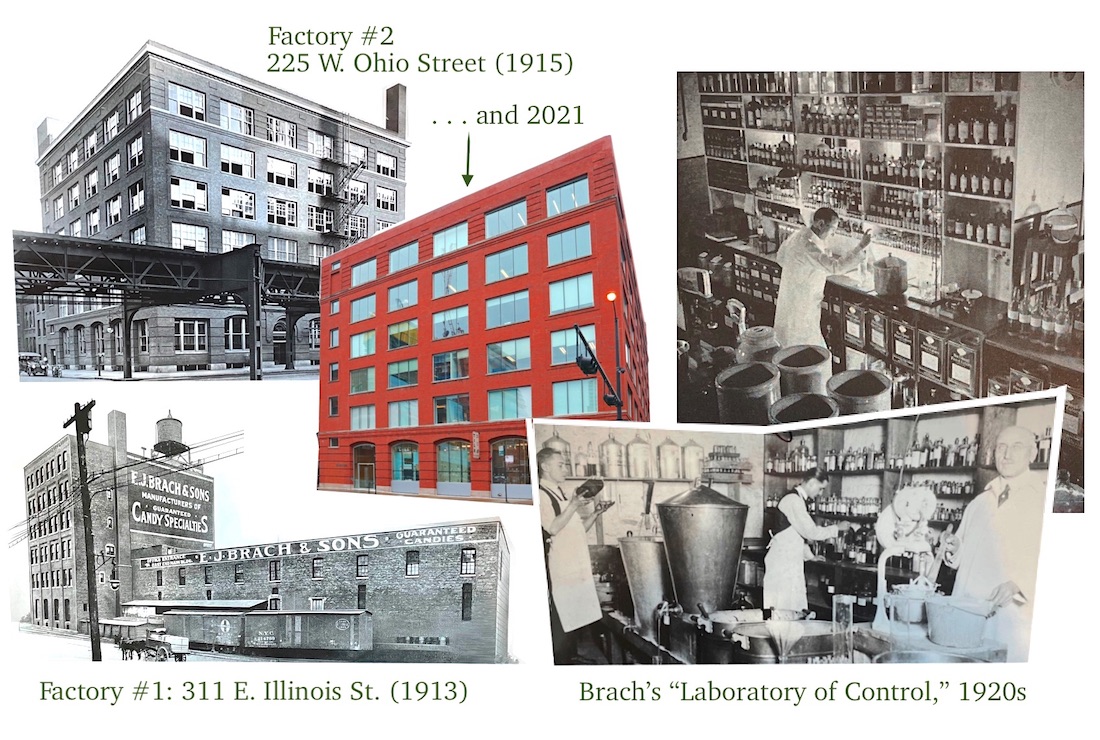

Another factory move was required by 1909—a five-story building at the corner of LaSalle and Illinois Street (which is still standing today)—helping to bump the weekly output to 50,000 LBS. And just four years after that, spiking sales forced the business to migrate to a more shipping-friendly facility down the street at 311 E. Illinois Street, right on a railroad line. Weekly production jumped to 250,000 LBS of candy, which also now included lines of jelly beans, fudge, cream candies, gum candies, marshmallows, and chocolate icing and dips.

E. J. Brach remained determined to keep costs low and labor minimized—he developed a mechanical hard candy cutter, for example, that became an industry standard. But there was also an established rule within the business that the Brachs would never get themselves indebted to outside entities via hefty loans, no matter how tempting the prospect. In the short term, this required some personal sacrifice, as Edwin and Frank Brach continued to make less than $10 a week even as their business produced 500,000 LBS of candy during that same interval of time. “All surplus money went back into THE FACTORY,” claimed another company memoir, 1944’s The Brach Family Album.

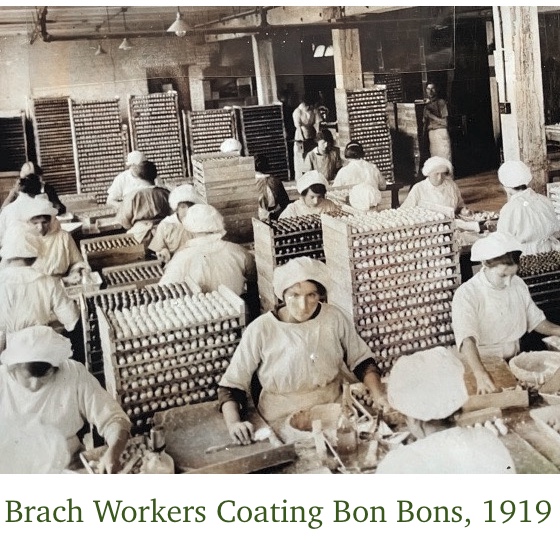

Maybe it’s true. After all, in the span of about five years—and even with all those mechanical innovations to reduce hand labor—the Brach workforce had still ballooned from about 6 folks in a backroom to more than 50. And that number would continue to rise exponentially as the firm employed not only more factory workers, but a national sales team and a unique staff of “confectionery scientists” in its “Laboratory of Purity and Quality Control”—a rather novel concept for a candymaker in the mid 1910s.

Maybe it’s true. After all, in the span of about five years—and even with all those mechanical innovations to reduce hand labor—the Brach workforce had still ballooned from about 6 folks in a backroom to more than 50. And that number would continue to rise exponentially as the firm employed not only more factory workers, but a national sales team and a unique staff of “confectionery scientists” in its “Laboratory of Purity and Quality Control”—a rather novel concept for a candymaker in the mid 1910s.

Originally, the Laboratory of Control was a sort of marketing gimmick to ensure the public that Brach’s candy was “clean” and “untouched” by the oft-diseased hands of human beings. But the department became increasingly sophisticated over time.

“When our president, Mr. Emil J. Brach, personally started a laboratory of control to test raw materials and perfect his private candy formulas,” a Brach company newsletter recalled in 1945, “little did he realize that he was starting a factory within a factory. . . . While today every process in the making of Brach’s Candies, from start to finish, is under the direct supervision of a staff of trained chemists . . . while every material is tested for absolute purity and each candy batch is tested and made to strict conformity with all the National and State Pure Food Laws . . . it is interesting to find that those delicate and distinct flavors that make Brach Candies so outstanding are actually made and blended in our own laboratory of control.”

There did reach a point, in the years during and after the First World War, where the Brach family probably didn’t feel the sense of control they might have liked over their ingredients, their facilities, or their reputation.

Like so many German-American businesses during the war, Brach’s suffered from plenty of unwarranted guilt-by-association during an era of rising anti-German sentiments. Emil Brach himself, having left Germany as a child, wasn’t as deeply immersed in Chicago’s German immigrant community as some of his fellow first generation businessmen. His wife, Katherine, was of Irish descent; their home wasn’t in a German neighborhood (but rather in Uptown, at 4151 N. Sheridan Road); and the family didn’t have much direct involvement in the city’s various German-American clubs and organizations. They almost certainly saw themselves as Americans through-and-through, making it all the more challenging to see some members of the public refuse to do business with them.

Along with pressures from the conflict overseas, Brach & Sons was also struggling with a slowdown in imports needed for their confections, and the complications of trying to fill increasingly large orders that now required four separate facilities—Factory No. 1 at 311 E. Illinois; Factory No. 2 at Franklin & Ohio Street; a shipping room in the Pugh Terminal; and Factory No. 3 (address unknown). If efficiency had made the business thrive, there was clearly only one path forward into the 1920s, when those weekly production numbers—once a cute 3,000 LBS per week—would now exceed 2 million pounds.

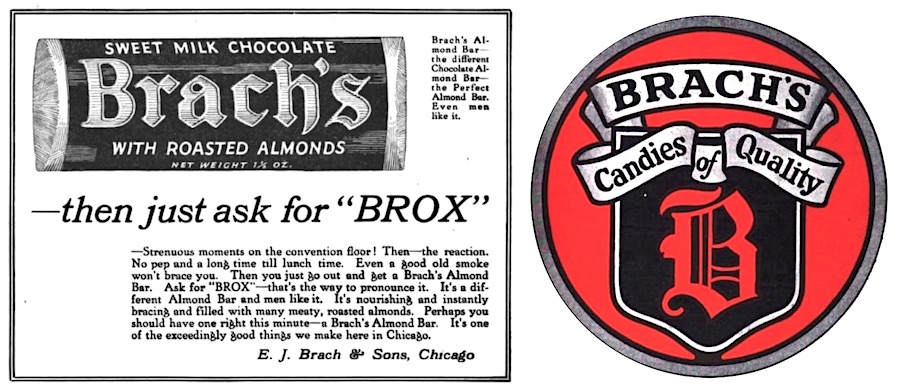

[As a subtle means of de-Germanizing the brand name during and after World War I, Brach’s began using the tagline “Just Ask for BROX,” as in the ad above, which appeared in the official program of the 1920 Republican National Convention]

III. A Five Million Dollar Candyland

“Among its many wonderful industries, Chicago boasts the greatest candy institution in America—E. J. Brach & Sons. . . . Today, Brach sells through the best class of candy merchants in America, 127 kinds of quality candy—each kind representing the pinnacle of quality, purity and flavor—yet selling at popular prices.” —Brach & Sons newspaper ad, 1920

For a while there in the early 1920s, Brach ads would claim that the company’s prices were so good that they were actually selling candies “below cost”—that was until the Federal Trade Commission took notice and determined that the company was clearly selling at a profit. That’s how you pay for giant factory overhauls, after all.

For a while there in the early 1920s, Brach ads would claim that the company’s prices were so good that they were actually selling candies “below cost”—that was until the Federal Trade Commission took notice and determined that the company was clearly selling at a profit. That’s how you pay for giant factory overhauls, after all.

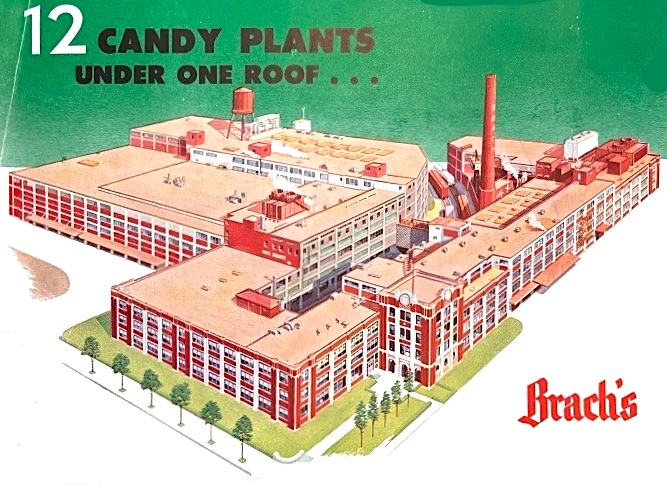

In 1922, work began on the building that would consolidate Brach’s entire manufacturing, research, and administrative wings under one very large roof. Alfred S. Alschuler, the undisputed king of Chicago industrial architecture, led the project, and by the following year, the new plant opened on the West Side at Kinzie, Kilpatrick, Kenton, and Austin Avenue.

At a cost of $5 million, it was more than twice as expensive to build as one of its inspirations—the new Bunte Brothers factory in Humboldt Park, which had been completed two years earlier for a mere $2 million. With Brach’s workforce now approaching 2,000 men and women, the building needed to be big enough to fit them and modern enough to keep them from jumping to one of the other hip new candy plants across town.

As such, the Kinzie plant was one of the original “sunlight factories” of the period, with windows filling half the wall space, complemented by seven acres of smooth concrete floors, a steam plant, a refrigeration plant, an electric transforming station, private railroad switches, and the “latest and most efficient labor-saving machinery of American and European make.”

[The Brach factory on Kinzie Street, as it looked in 1945, after several major additions]

This included a state-of-the-art department dedicated to chocolate production, as Brach looked to make inroads not just in box chocolates, but in the chocolate bar craze of the ‘20s, which already included Curtiss’s Baby Ruth, Williamson’s Oh Henry, and Mars’s Milky Way. Their answer, it seems, was Brach’s Almond and Milk Chocolate Bar, aka “The Perfect Almond Bar,” but it never gained a ton of traction. Another attempt was made years later with the 5-cent “Swing” bar, with similar mixed results.

Even so, Brach promoted its chocolate bars in the ‘20s as “concrete examples of the constant striving toward a goal of perfection in which this organization takes a special pride. Behind each confection made by Brach—every pail candy, the many chocolate products, fancy box confections and bar goods—there lies a story of rare workmanship, of nature’s finest products gathered from the ends of the earth, of delicate blending with the most highly sensitive machinery.”

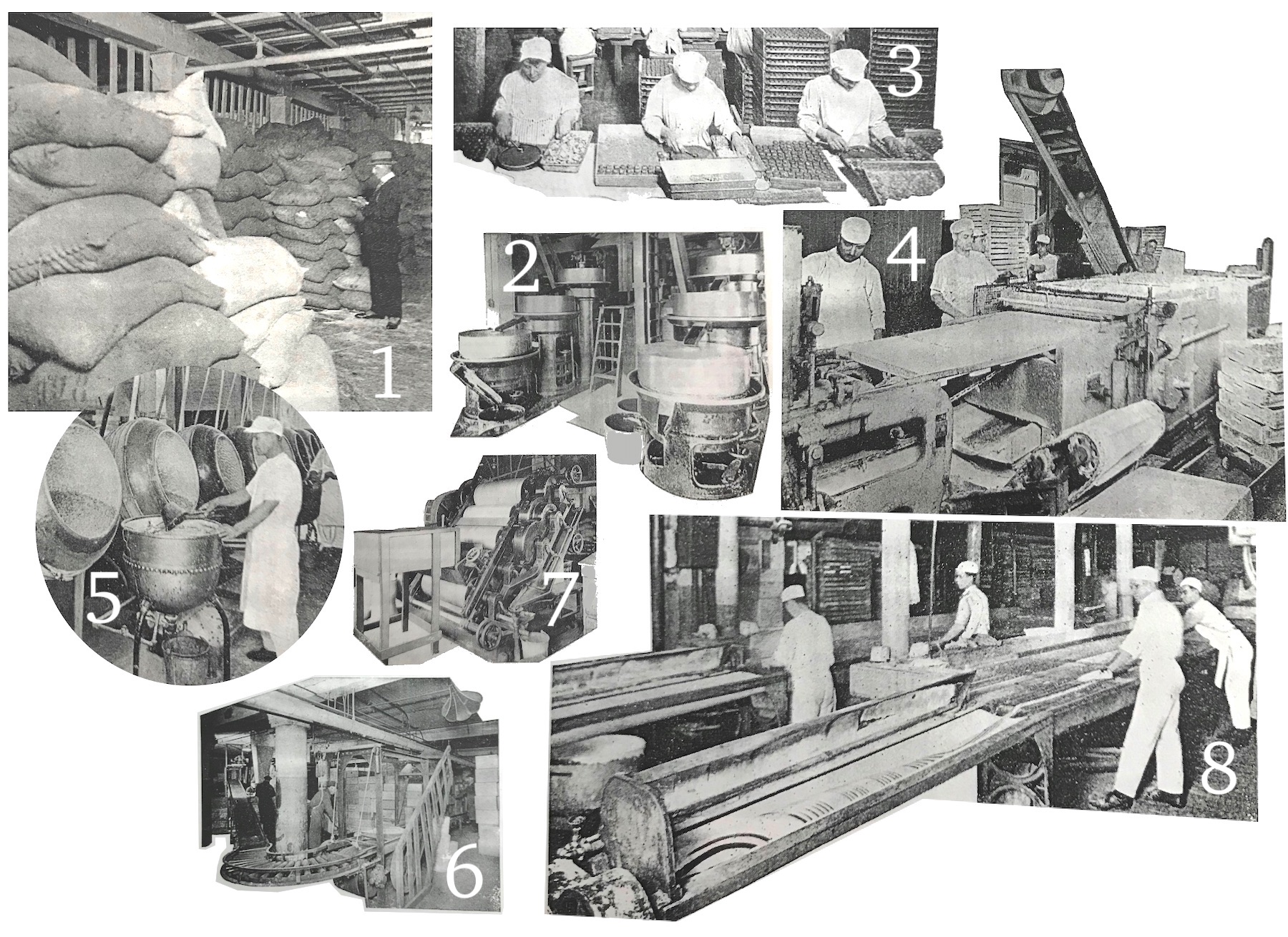

Inside the Brach Factory, 1925

[1- Inspecting a shipment of Venezuelan cacao beans in the receiving house. 2- Triple mills grind the kernels of the cacao beans into a semi-liquid state. 3- Women hand dipping a cream fondant on Brach’s Glace Dipped Creams. 4- A “Mogul” machine molds close to 2,000 circus peanuts per minute. 5- Batteries of large revolving pans keep the “centers” of pan candies rolling as successive coatings are applied. 6- A powerful conveyor runs through the shipping department. 7- Five steel roller refiners grind chocolate down to “amazing fineness.” 8- A batch roller spins stick candy to give a “twist” effect to the stripes.]

Following the death of his wife Katherine in 1924, Emil Brach—now in his mid 60s—started dating one of the factory’s filing clerks, a 37 year-old Swedish immigrant named Marie Hult. The two married in 1925, and Emil mostly retired to Florida and the Carolinas, only making occasional visits to Chicago to check on his sons’ progress. Strategically, the Brach marketing team never let Emil drift too far from the company’s branding, however—reinforcing the comforting idea of a friendly patriarchal overseer and his steady, reliable family business.

That image came in handy when the freewheeling 1920s abruptly gave way to the struggles of the 1930s. Brach’s slumping sales mostly mirrored the entire industry, which was doing about half the business it had back in the heights of the candy boom, but the company still somehow eked out profits and continued to invest back into its ever-expanding factory campus, which was already on its third major overhaul by 1935.

That image came in handy when the freewheeling 1920s abruptly gave way to the struggles of the 1930s. Brach’s slumping sales mostly mirrored the entire industry, which was doing about half the business it had back in the heights of the candy boom, but the company still somehow eked out profits and continued to invest back into its ever-expanding factory campus, which was already on its third major overhaul by 1935.

That year, discussing the addition of a new shipping and storage wing with a modern conveyor system, vice president Frank Brach told the Tribune, “The steadily increasing volume of our business, together with the urgent need of speeding up the loading of the increased number of trucks that come to pick up our candies from practically every state, make this new wing an urgent necessity. . . . Despite the present low price range for candy, our business has grown right through the depression.”

Frank then made sure to mention that, “thirty years ago, my father, brother, and I started with a small, one story candy shop at North avenue and Towne street. We specialized then as we do now in the popular priced candy favorites that always have been in demand.” As always, the idea of a quaint family business was more appealing than the reality of an increasingly massive candy corporation, sending out fleets of trains and trucks with stockpiles of machine-siphoned mints and marshmallows. It was also a rosier picture than Frank’s own family life; his first wife Eunice, mother of his two children, filed for divorce in 1931, citing domestic abuse.

IV. Energy Food for the Armed Forces

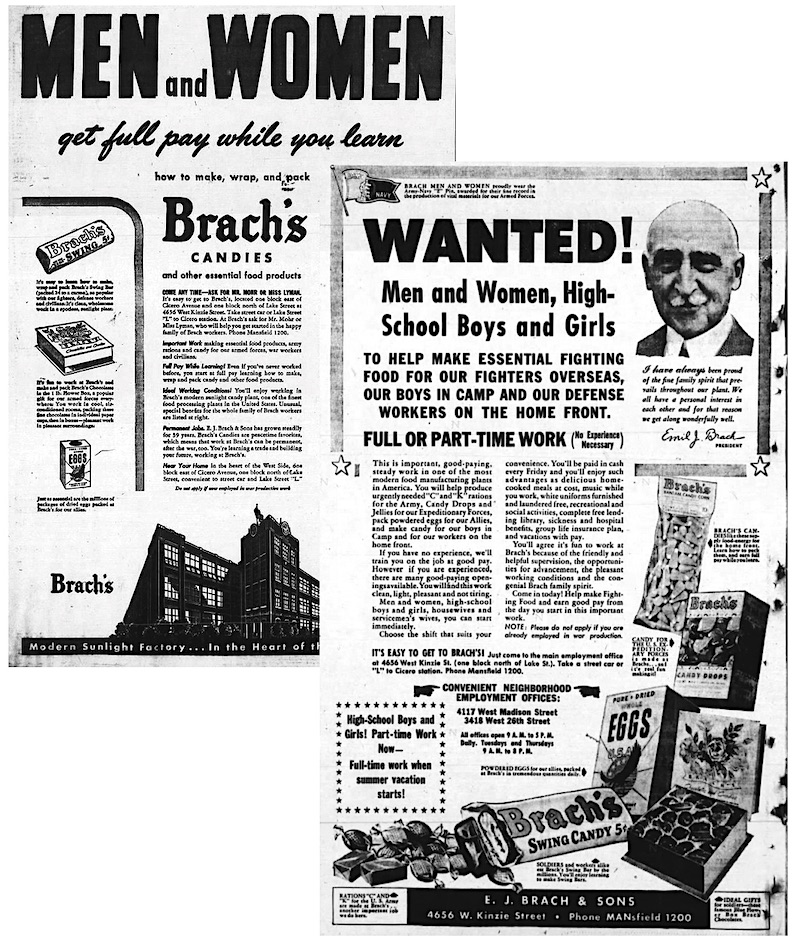

“WANTED! Men and Women, High-School Boys and Girls . . . to help make essential fighting food for our fighters overseas, our boys in camp, and our defense workers on the home front. Full or part-time work. No experience necessary.” —Brach newspaper ad, April 1944

For a lot of Chicago manufacturers, the demands of World War II required an abandonment of one’s primary product line in favor of highly specific defense contracting—munitions production and the like. The city’s leading candymakers usually had a more subtle transition out of their civilian normality, though, making largely the same sorts of products, but packaged in even greater numbers, and with a soldier’s rations in mind. Sometimes, the government would also task the candy plant with a bit of food production outside its usual ouvre—in Brach’s case, a whole department was set up to make powdered eggs.

For a lot of Chicago manufacturers, the demands of World War II required an abandonment of one’s primary product line in favor of highly specific defense contracting—munitions production and the like. The city’s leading candymakers usually had a more subtle transition out of their civilian normality, though, making largely the same sorts of products, but packaged in even greater numbers, and with a soldier’s rations in mind. Sometimes, the government would also task the candy plant with a bit of food production outside its usual ouvre—in Brach’s case, a whole department was set up to make powdered eggs.

Being a wartime food provider undoubtedly elevated the Brach brand on to the national stage like never before, leading to its first major national advertising campaigns, which positioned the vaguely German sounding company as a purveyor of patriotic “energy food for the United States Armed Forces.” Millions of Brach caramels, cellophaned hard candies, boxed Candy Drops and Jelly Drops, chocolate Swing Bars, and other treats were dropped into designated “C” and “K” rations for the troops, while plenty more were distributed via the Red Cross to prisoners of war, the USO, and defense plant workers.

“Naturally the diversion of so much of our production from civilian consumption has restricted our deliveries to thousands of regular Brach customers,” read one ad in 1944. “But in the spirit of the times, which is the spirit of Victory and Freedom, we have enjoyed the friendly understanding of our customers and their gracious acceptance of curtailed deliveries from our plant.”

As soon became clear, losing much of that usual peacetime civilian market was nothing compared to the gains of a government contract. To keep up with the demand, Brach was constantly recruiting more sales team members and factory workers to come by and apply at the plant, with more than 2,500 eventually filling out the roster.

“Get full pay while you learn how to make, wrap, and pack Brach’s Candies,” read one 1943 recruitment ad. “Come any time. . . . Ask for Mr. Mohr or Miss Lyman, who will help you get started in the happy family of Brach workers.”

“You’ll be paid in cash every Friday,” another ad proclaimed, “and you’ll enjoy such advantages as delicious home-cooked meals at cost, music while you work, white uniforms furnished and laundered free, recreational and social activities, complete free lending library, sickness and hospital benefits, group life insurance plan, and vacations with pay.”

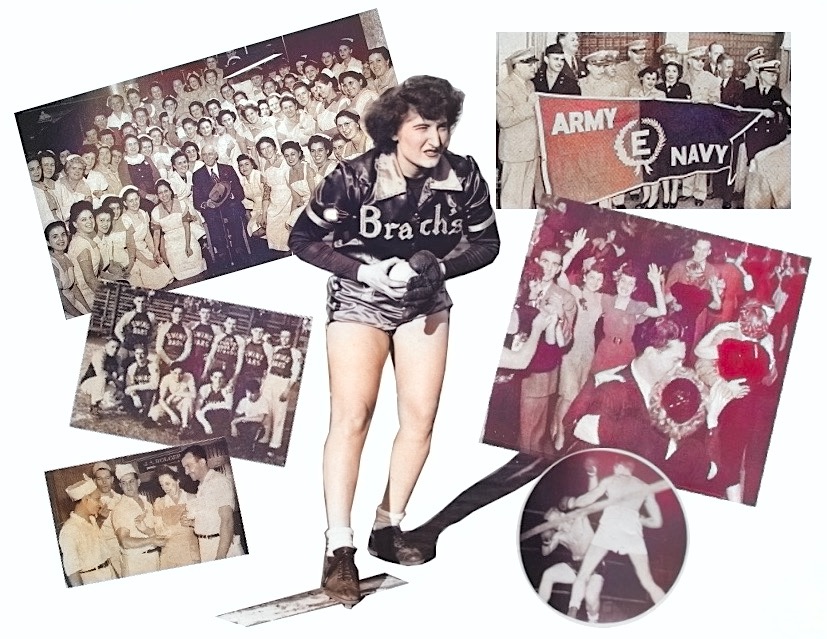

Along with the serious mission of “Victory,” these various workers perks—which also included company dances, picnics, charity boxing matches, and organized bowling and softball leagues—all contributed to a shared sense of purpose and camaraderie among many of the wartime workers—new and old, male and female, black and white. There was also a constant awareness of the more than 400 Brach employees who’d been forced to leave their jobs to serve in the conflict.

“I have always been proud of the fine family spirit that prevails throughout our plant,” an 85 year-old Emil Brach was quoted in 1944. “We all have a personal interest in each other and for that reason we get along wonderfully well.”

The Brach factory was awarded an Army-Navy “E” flag for exemplary performance in 1943, followed by a “White Star” award in 1944 for continued “meritorious service.” That year, a company newsletter noted, “It’s been three years now since we were catapulted into the greatest war in American history. . . . Years that have seen high school students on assembly lines, women handling sealing machines, and salesmen stacking candy cases in freight cars. These have been exciting, maddening, tragic and yet triumphant years.”

[Even during the darkest days of World War II, morale was kept up at the Brach factory with picnics, dances, and sporting events, including a charity boxing night, bowling league, and men’s and women’s softball leagues. Pictured in the center of the collage is Alice Kolski Lundgren of the “Brach’s Kandy Kids” softball club. She didn’t work in the candy plant, but was employed by the team the factory sponsored. She led the Kandy Kids to the 1944 championship in the National Girls Softball League and was named its Most Valuable Player.]

V. A Post-War Bomb

In some ways, the trials of WWII gave Brach’s a clear and positive sense of identity; something that would prove harder to maintain during the unexpectedly tumultuous years that followed VJ Day.

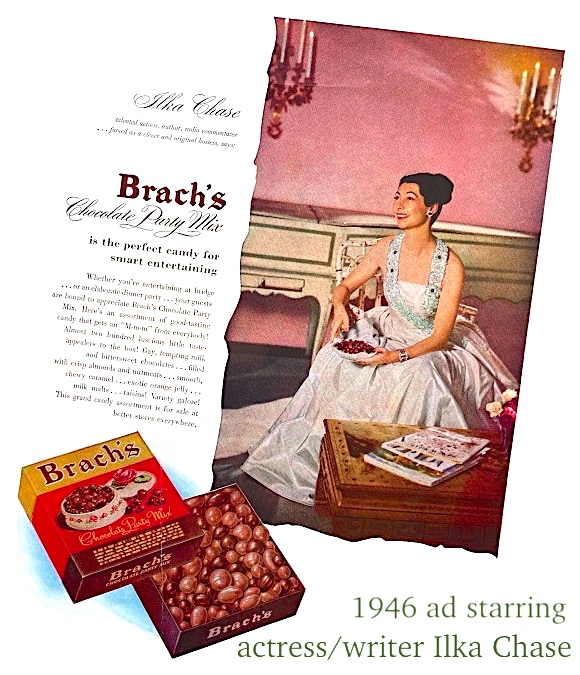

In 1947, Emil Brach died, concluding his transition from business leader to mythical figurehead. Sons Edwin and Frank, who’d been running the company for over two decades, had a lot of choices at their disposal for how to maneuver the Brach brand after the war. Along with yet another factory addition, completed in ’47, the national marketing campaign continued to grow and evolve, with many ads now painting Brach’s as more of a luxury candy brand for the choicier sophisticate; people like actress and author Ilka Chase, who popped up in post-war ads for the company.

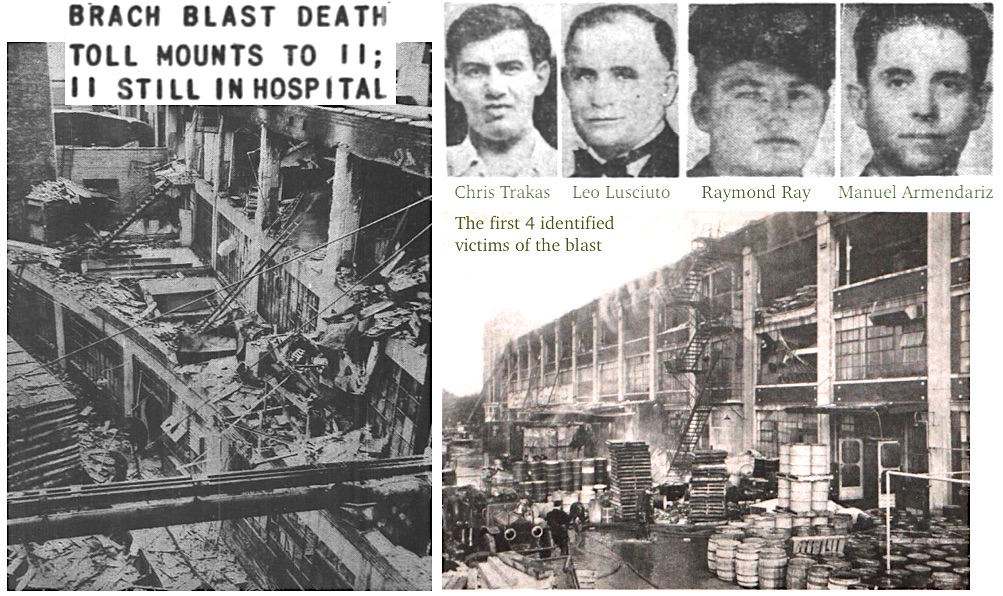

That sort of image was abruptly undercut, however, by tragedy—as a deadly explosion at the Chicago plant made national headlines in the late summer of 1948.

That sort of image was abruptly undercut, however, by tragedy—as a deadly explosion at the Chicago plant made national headlines in the late summer of 1948.

“Although it had been charged with violations of fire department regulations some time before,” the magazine Fire Engineering later said of the recently revamped Brach plant, “the factory was said to be as near disaster-proof as modern science could make it at the time of the fire. Notwithstanding this fact, an explosion occurred in the early hours of the morning, either as a result of a fire, or from some undetermined cause, which had all the effects of a super bomb of World War II.”

The sound of the explosion and the ensuing plumes of smoke—which began at approximately 3am on September 7, 1948, awakened many residents on the West Side, and created many a longstanding local anecdote. It was also one of the worst industrial tragedies in the city’s modern history, killing 15 workers and injuring several fire fighters. Weeks of investigations determined the likely cause was an electrical spark interacting with corn starch in the air. The factory’s sprinkler system couldn’t slow the spread, nor could the efforts of several late shift workers, who had emptied all available extinguishers before perishing in the blaze.

It took one-third of the Chicago Fire Department to put out the flames and save the factory, and all agreed that had the same incident occurred during daylight hours, many hundreds could have been killed.

“It is management’s solemn duty to safeguard their employees,” a mournful Frank Brach said in the aftermath. “It is a matter of conscience, a matter of good business, and a matter of decency for an employer to do everything in his power to put his plant in safe condition.”

[After the explosion, many victims were in the hospital for days, as the death toll slowly grew to 15]

A company announcement extended deepest sympathies to the families of the lost employees, gratitude to the firefighters, and encouragement to the nearly 2,500 Brach workers hesitant about the future.

“In a disaster of this kind it is heartwarming to note how every man and woman in our organization has risen to the challenge of the occasion, devoting full energy to carry on, and it is most gratifying to have had offers to help and cooperation from so many of our fellow candy manufacturers.”

The explosion helped increase awareness of the dangers of “starch dust” fires, and information from the investigations was shared with candy plants around the world.

[Various group shots of Brach’s diverse workforce in 1947-48]

VI. Pick-a-Mix

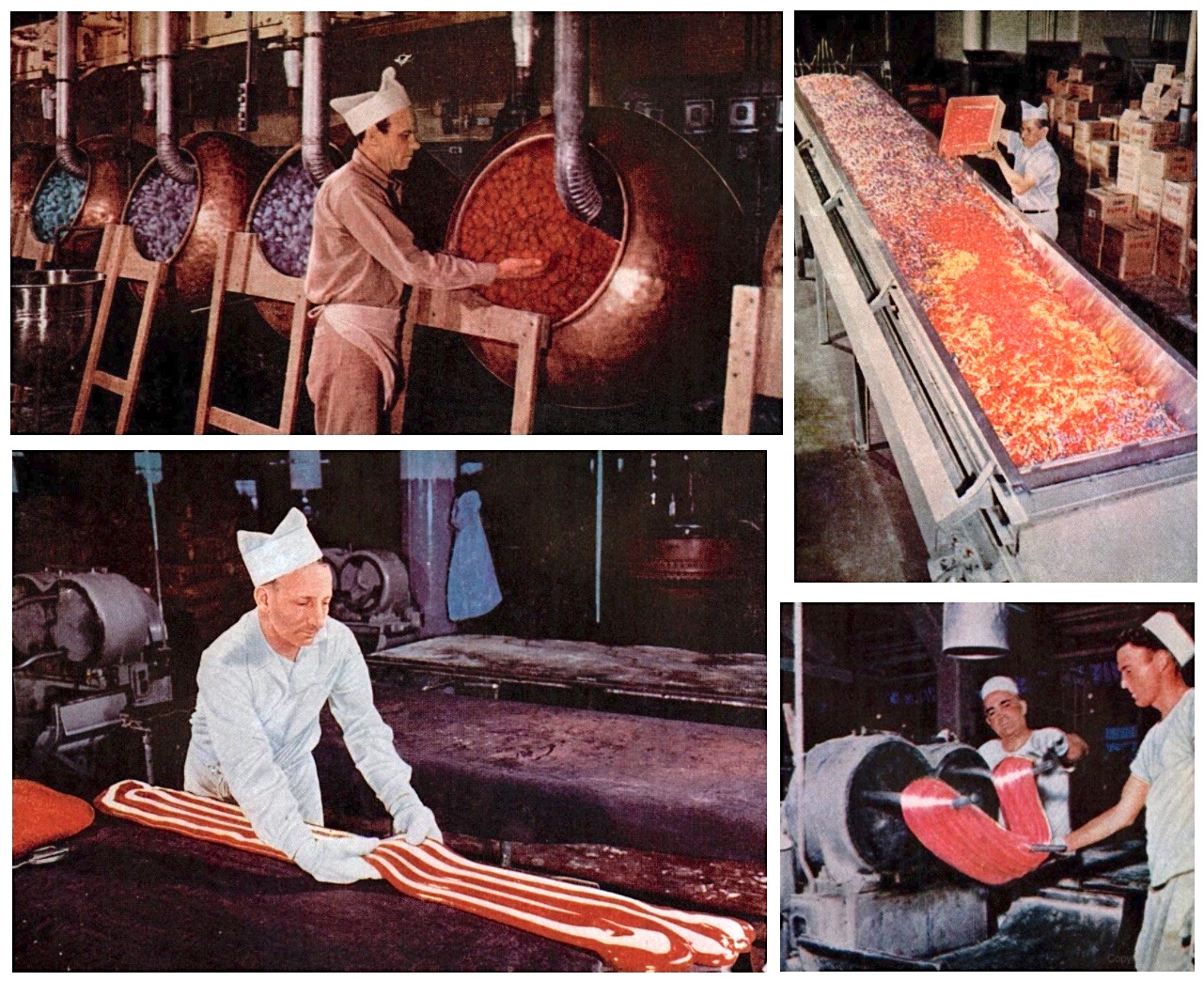

“High atop a huge factory in Chicago is the fairy-tale kingdom of a man with a unique and appealing profession,” began an article in the December 1952 issue of Popular Mechanics. “So appealing, in fact, that if he were only known to the nation’s small fry he’d outdazzle all manner of cowboys, puppets, and spacemen. This is America’s largest sweet-tooth factory—a full 17 acres of luscious sights, smells and tastes—and here Otto Windt plies a unique trade in the high little office: he’s actually paid to taste candy, day in and day out.”

Just four years removed from the factory explosion, the Brach plant—and its chief candy technician Otto Windt—were now the envy of an idealistic, candy-loving nation once more. While most kids had to wait til Easter or Halloween for a big haul of Brach’s, the guys and gals at the Chicago HQ seemed to be in a sort of perpetual, colorful holiday state.

Just four years removed from the factory explosion, the Brach plant—and its chief candy technician Otto Windt—were now the envy of an idealistic, candy-loving nation once more. While most kids had to wait til Easter or Halloween for a big haul of Brach’s, the guys and gals at the Chicago HQ seemed to be in a sort of perpetual, colorful holiday state.

“Today Brach’s may ship out a million pounds of candy in 24 hours,” Popular Mechanics noted. “Some of the figures are significant: It takes 20,650 acres in cane and beets to produce the company’s sugar intake; 20,250 acres of corn to make the corn syrup; the full production of 2,750 dairy cows to meet milk requirements.”

Meanwhile, to process all those ingredients, the factory—managed by VP Bill Melody—now included “every conceivable mechanical aid . . . hydraulic pumps shoot peanut butter and fruit fillings into the heart of hard candies . . . Glistening stainless-steel kettles—vacuum cookers—turn out 300-pound batches of sweets. Huge mixers stir cream centers to velvety smoothness, and miles of conveyor belts carry ingredients, candies, and packaging materials to workers throughout the plant.”

Inside the Brach Plant, 1952

[Top Left: The tumble drum “panning” process with candy eggs, giving them their color coating and luster. Bottom Left: Candy or “rope” is pulled on a hot, leather-topped table. Top Right: A big assortment of different candies is churned in a mechanical bin to be packaged as party mixes. Bottom Right: “Swinging the batch” by looping the candy over the arms of a mechanical puller to create texture. From Popular Mechanics, December 1952]

In the 1950s, Edwin and Frank Brach, each now in their 60s, were still bold and ambitious about the company’s growth potential, but also a bit more conservative about the type of products that would get them there. The chocolate bar market, for example, was getting a bit too fierce, and Brach’s long battle to compete against the Baby Ruths and Snickers of the world looked far less appealing than a more focused dedication to the smaller hard candies they’d always done best.

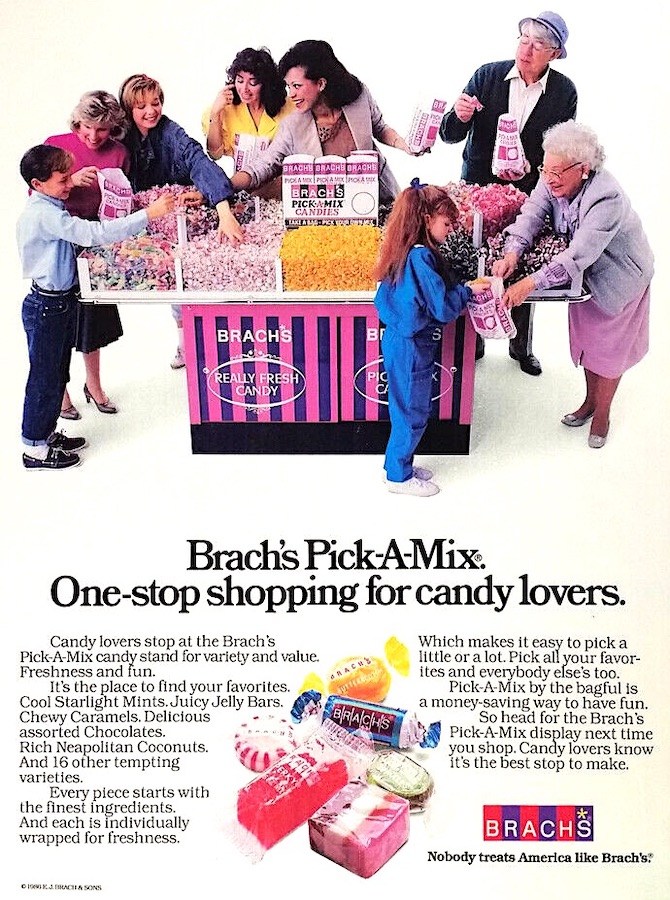

With colorful magazine and television ads spreading the name far and wide, Brach’s solidified its place as the biggest producer in the bulk candy game—with sales taken to new heights by its “Pick-A-Mix” scheme, which enabled supermarket customers to grab assorted scoopfuls of different Brach candies and buy them by the pound. It was a throwback to the old days of the Palace of Sweets in a way, and it would soon become the norm in many grocery stores from the late 1950s onward.

In 1961 alone, E. J. Brach & Sons produced over 200 million pounds of candy, which now came in more than 500 different varieties. It was the company’s best ever sales year to date, topping $62 million (closer to $600 million after inflation), and the common stock of the business was also now admitted for trading on the New York Stock Exchange for the first time. In a country with more than 400 substantial candy manufacturers, Brach’s owned 7% of all U.S. sales.

In 1961 alone, E. J. Brach & Sons produced over 200 million pounds of candy, which now came in more than 500 different varieties. It was the company’s best ever sales year to date, topping $62 million (closer to $600 million after inflation), and the common stock of the business was also now admitted for trading on the New York Stock Exchange for the first time. In a country with more than 400 substantial candy manufacturers, Brach’s owned 7% of all U.S. sales.

Between 1955 and 1965, another $10 million was put into expanded factory space and equipment, as the Kinzie complex started to look like a candyland palace of a more literal sort. A lettering system that had been adopted to identify the separate plants and warehouses in the complex had now reached all the way to “R” and “S” after a pair of 11-story warehouses went up in the mid ‘60s.

“We run into a somewhat unusual problem every time we complete new warehouse facilities,” Brach VP Stephen T. Powers told the Garfieldian in 1964. “About the time a new warehouse is completed, we find we need increased production space, so it is converted for manufacturing. Then we must draft further plans for warehouse facilities.”

To its competitors, the most infuriating part of Brach’s endless growth was the fact that—true to its early principles—the business had no debts, back loans, or mortgages. “My banker friends say I’m a bad customer,” Frank Brach joked to the Tribune in 1965, “but that’s alright with me. I like to pay for the expansions out of funds from operations.”

Despite this unique position of success and stability, Frank Brach was no spring chicken, and he was spending most of his time—as his father had—in Florida, living in semi-retirement with his second wife Helen. As such, when Frank’s older brother and company chairman Edwin Brach died in 1965, the fate of the family business was put in serious question for the first time.

In February of 1966, some fears were realized when it was announced that E. J. Brach & Sons would be acquired by the one the country’s proto brand-eating conglomerates, American Home Products. As part of the deal, though, the Chicago plant would continue to operate independently, and Frank Brach would remain as its chief executive.

VII. Brach’s After the Brachs

After Frank’s Brach’s death in 1970, the company’s fragile connection to its humble roots was lost. Frank’s second wife, widow, and heiress to his fortune, Helen Brach (aka “The Candy Lady”), suffered a particularly sad fate in the ensuing years.

Helen put a lot of her efforts into a foundation for animal welfare, and soon began dabbling in the expensive world of race horse training. In due time, she was defrauded by the operators of a corrupt country club stable, and was soon targeted as part of a more sinister criminal conspiracy. Returning from a trip to Rochester, Minnesota, in February of 1977, Helen Brach disappeared without a trace and was never seen again. Foul play was always assumed, but no one was ever charged in the disappearance itself, despite a few obvious suspects from the busted horse racket.

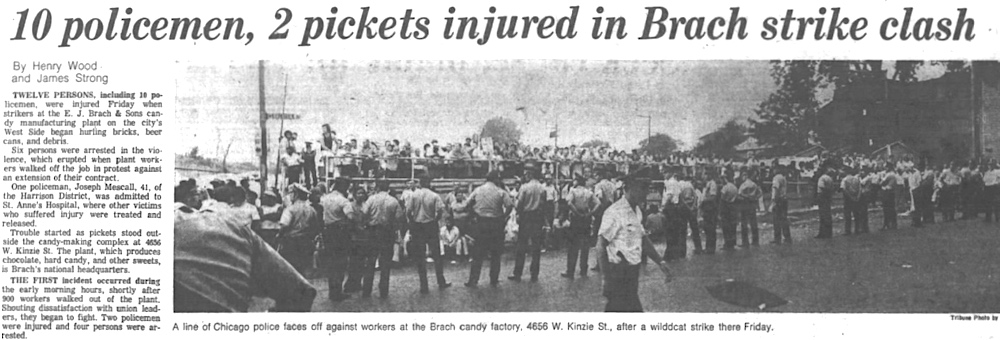

Along with the ugly tabloid tale of Helen Brach dominating headlines, the Brach plant in Chicago was also the site of a violent labor protest in the summer of ’77, when 900 striking workers walked out of the plant and soon clashed with police, resulting in a dozen injuries and a half dozen arrests. A lot of employees were frustrated, in part, by feeling unrewarded by the continuing success of the Brach candy business itself, which was still posting strong sales through the 1970s into the 1980s.

When American Home Products finally opted to sell the company at a commercial peak, coming off profits of $75 million in 1986, the Chicago mega-plant was employing more than 3,500 workers, maintaining a delicate balance with union leaders that would later give way to more strikes in the early 1990s.

[Brach’s union workers increasingly clashed with ownership in the years after the Brach family sold the business, including this violent walkout in 1977]

The new owners, Jacobs Suchard LTD of Switzerland, were not well loved by the locals, nor were they able to keep up Brach’s long streak of success, as sales plummeted from the late ‘80s into the ‘90s, with CEO Klaus Jacobs widely blamed for over-managing and consistently mishandling the basics of time-tested candy selling in the U.S. market. During this same period, Brach’s merged with the similarly named Brock Candy Company of Tennessee, boosting sales but confusing just about everybody.

The cardinal rule of the Brach family—to avoid going into debt—was well out the window with these new operators, and by the time the firm was sold to a different Swiss firm, Barry Callebaut AG, in 2003, the deal primarily hinged on Callebaut agreeing to get Brach’s Confections out of a $16 million hole. Hence, the symbolic purchase price of one dollar.

The Chicago plant closed its doors after 80 years in 2003, and since 2012, Brach’s has existed under the ownership of the Ferrara Candy Co.—another pan candy name with deep Chicago roots and complicated 21st century entanglements (the current iteration of the business actually came about from another confusing alliance, as Ferrara merged with Minnesota’s Farley & Sathers in 2012, then was acquired by the Italian confectioner Ferrero SpA in 2017).

In 2019, Ferrara (still owned by Ferrero) announced its corporate headquarters would be returning to Chicago, inside the Old Post Office at 404 W. Harrison Street. And thus, Brach’s—in a roundabout fashion—has come home.

Sources

“Emil Julius Brach” – ImmigrantEntrepreneurship.org

“Four Great Brach Factories Dedicated to Making Quality Candies” (Advertisement) – Chicago Tribune, March 21, 1920

The Story of Brach, c. 1924

“Mrs. Frank Brach Seeks Divorce” – Chicago Tribune, Sept 13, 1931

“Brach Builds Big Addition to Candy Plant” – Chicago Tribune, April 7, 1935

The Brach Family Album, 1944

Brach News, June 1945

Brach’s Record Album, 1946

The Brach Review of 1947

“Inquest Told Dust Blast Caused Brach Fire That Killed 15” – Chicago Tribune, Oct 15, 1948

“Chicago Candy Plant Explosion Blamed on Dust” – Fire Engineering, Jan 1, 1949

“They Make Candy By the Ton” – Popular Mechanics, December 1952

“Brach Expansion Details” – The Garfieldian, Jan 15, 1964

“E. J. Brach, 77, Head of Candy Company, Dies” – Chicago Tribune, Jan 28, 1965

“Chief Candy Taster at Brach’s Also Holds Down Presidency” – Chicago Tribune, July 4, 1965

“American Home and Brach Tell Plan to Merge” – Chicago Tribune, Feb 21, 1966

“$23 Million Estate Left By Brach” – Chicago Tribune, July 3, 1971

“City’s Candy Crown Toppling” – Chicago Tribune, June 10, 2001

Archived Reader Comments:

“Hi my name is Stella Klich (maiden name Pierri ) once worked at Brach Candies , I started back in Aug of 1970 till April of 1995. last dept. was Customer Service . My now husband Edward Klich worked in the Shipping Dept as the Supervisor from 1965 till Dec of 2004 where he Shipped out they last Truck of this Wonderful Awesome chocolate. It was a very sad goodbye for all employed at Brach;s. Good Memories made there.  ” —Stella Klich, 2019

” —Stella Klich, 2019

“My father worked for Brach’s in the cherry department.” —cam08554, 2019

“I worked for Brach Candy in Chicago for 30 years, from 1973 until the closing in 2003, I knew the 2,2 mil. square foot facility from top to bottom, inside and out, loved working there, hated to see it shut down.” —A. Thornton, 2019

I’m curious if anyone can assist me. I recently bought a solid wood door with a cone-shaped top, resembling a castle door. It’s approximately 8 ft tall, 4 ft wide, and the seller claimed it’s from the Chicago Brooks Candy building. Wondering if anyone recalls such doors or has information about them.

My father, Bill McDonald worked as a process engineer at Brach’s automating the candy lines. I’m sure he is responsible for improving their profit margins during the 1970’s and early 1980’s.

I worked for Loretta Josefowski one summer in the late 70’s during college break.

I did multiple jobs, for her employees that went on summer vacation. I remember getting samples of Chocolate Liquor ready for Loretta and three other super tasters, of course I was instructed to taste it also. Loretta was the Lab supervisor. I would get trained by each employee, and then perform their duties while they were on vacation. I like chocolate covered mint patties, chocolate covered peanut clusters and chocolate covered caramel peanut clusters right off the production line. Of course Chocolate Covered Cordial Cherries were a great treat. It was interesting seeing how candy is made from raw materials, flavors, processes, factory equipment, employees, and packaging machines. It’s like I got the “Golden Ticket” to explore Chicago’s Brach’s Candy Factory.

Conan McDonald

Where can I purchase a 5lb box of assorted chocolates? I was born in 1955 and always remember one present we could open on Christmas Eve ….. a piece of chocolate from Brach’s. It was a tradition that lived on in my family for years. I would like to carry on the tradition.

My aunt, Loretta Josefowski, who worked for Brach’s for 39 years, once got me a summer job there when I was in college. I worked in the office but one time went on tour of the plant. I found it fascinating! The Halloween candy corn was made by machinery that formed the candy shape into trays of cornstarch. Then the machine would pour the 3 colors of liquid into the cornstarch and the whole tray would be put into a cooler. Later the cornstarch would be shaken off and the candy corn would be left in the tray. Another great candy to see be made was their chocolate coated malted milk balls. The center would first start out being very hard pellets of malt. They were so hard you could break your teeth on them. The workers put them in a round oven and heated air would be blown in as the malt pellets would be tumbled in the rolling oven. The hot air caused the pellets to expand and 30 minutes later you had a melt-in-your mouth malt center. They then coated the centers with chocolate and put them back in a tumbler to be buffed and polished til they were shiny chocolate covered malt balls. What a production! I came home that day with my clothes smelling like every candy I had seen be made that day!

My aunt, Loretta Josefowski, worked for Brach’s for 39 years. She had a degree in biology/chemistry and worked in the lab testing incoming raw products like sugar. At one point, Brach’s tested some employees to put them on a ‘taste-testing’ panel. She was found to have 100% tastebuds meaning she could detect any flavor or ingredient that was put before her. When he retired, the President of Brach (Frank Brach??) wrote her a letter reminding her that in the whole Brach’s company, only she and he had been proven to have 100% taste!! When she retired, the marketing department hired her as a consultant to taste and compare competitors’ candy to Brach’s candy. Over the years, her nieces and nephews enjoyed many a product of Brachs. In fact, as a baby, my first tooth was cut on a piece of Brach’s hard candy!

My grandfather John Brach ( died in 1963) claims he was related to then Brachs Candy co. He came over from Poland. WE don;t know about any of his family. At least once a year he would to to New York but no one knew why. Did E J Brach have any family? Is there any place I can get some information?

Thank You

Linda JO Brach