Museum Artifact: Burma Brand Spices: Pure Ground Cinnamon Tin, c. 1940s

Made By: Empire Spice Mills Manufacturing Company, 917 S. Western Ave., Chicago, IL [Near West Side]

Chicago’s Empire Spice Mills Manufacturing Company (no relation to the current Empire Spice Mills of Winnipeg, Canada) was a peculiar little enterprise that only existed for a little over a decade, from the late 1930s to a few years beyond the Second World War. It was not a major commercial player in the spice game, and was actually cited on several occasions for violating the U.S. Food & Drug Act by falsely labeling its products. A “pure” vanilla extract, for example, was found in 1940 to contain mostly a hodge-podge of artificial flavorings and colors. Lest we write this Empire off altogether as a forgettable fly-by-night, however, a few nuggets of intrigue do stand out from its story.

For one thing, they knocked it out of the park with their packaging! The tiger logos and striking blue-and-gold labels of Empire’s “Burma Brand” product line have charmed vintage tin collectors for decades. To our admitted surprise, some of those old trademarks are also still very much in active use. Burma, in fact, is the flagship brand for another Chicago business called Consumers Vinegar & Spice Company, Inc.—the same wholesale firm that bought out Empire Spice Mills way back in 1948 [the actual namesake country of Burma hasn’t even kept its branding for that long, as it became Myanmar in 1989].

For one thing, they knocked it out of the park with their packaging! The tiger logos and striking blue-and-gold labels of Empire’s “Burma Brand” product line have charmed vintage tin collectors for decades. To our admitted surprise, some of those old trademarks are also still very much in active use. Burma, in fact, is the flagship brand for another Chicago business called Consumers Vinegar & Spice Company, Inc.—the same wholesale firm that bought out Empire Spice Mills way back in 1948 [the actual namesake country of Burma hasn’t even kept its branding for that long, as it became Myanmar in 1989].

Certainly the most noteworthy piece of trivia tied to this business, though, is the name of the fella who owned it.

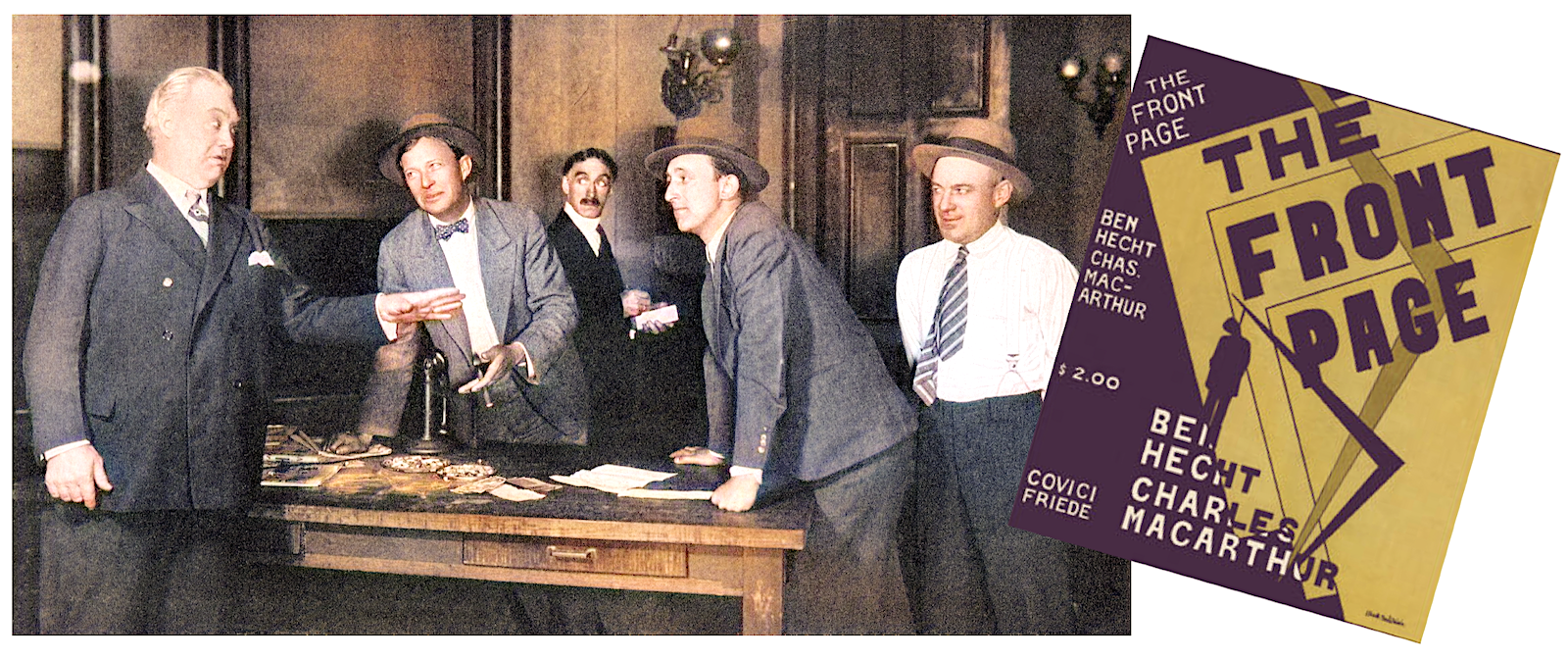

Harry J. Romanoff, who is regularly listed throughout the 1940s as the president and registered agent of the Empire Spice Mills MFG Co., was far better known to Chicagoans of this era as one of its preeminent newspaper reporters. In many respects, he was the real-life model for the determined, flamboyant, fast-talking Chicago newsman often celebrated and satirized on stage and screen. Even the hit Broadway play The Front Page (1928), which helped popularize that archetype, was written by a couple of Romanoff’s former newsroom colleagues, Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur.

So how did the man with his ear to the ground wind up peddling pure ground cinnamon? Your guess is as good as ours, but we do at least know a bit about the journalist behind the spice dealer . . .

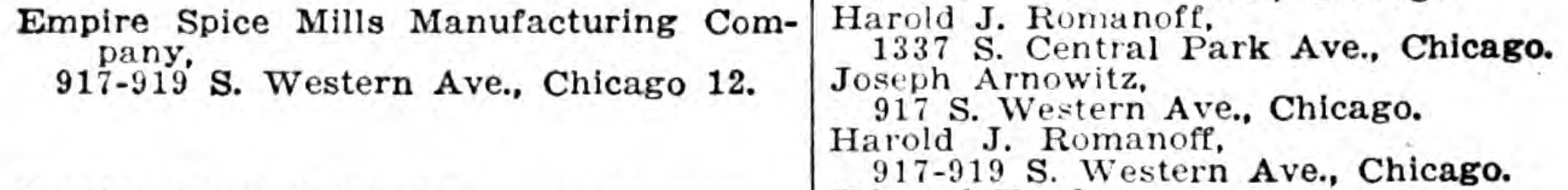

[The above 1944 listing from Illinois’s Certified List of Domestic and Foreign Corporation shows Harold “Harry” J. Romanoff as the president and registered agent of the Empire Spice Mills MFG Co.]

[Playbill and still photo from the 1928 Broadway production of “The Front Page,” inspired by the Chicago newspaper world of the 1920s and characters like Harry J. Romanoff. Pictured on stage are actors George Barbier as “The Mayor,” Willard Robertson as “Murphy,” Claude Cooper as “Sheriff Hartman,” Allen Jenkins as “Endicott” and William Foran as “McCue”]

Getting the Story

Born in Chicago in 1896 to Russian immigrant parents, Harry Romanofsky had all the hutzpah of a first-generation American kid living in the country’s fastest growing city. As a teenager, he was already “head copy boy” at the City News Bureau by the time Ben Hecht first joined the staff there. And by the 1930s, he’d established a reputation—even in the ultimate age of unashamedly sensationalist reporters—as the one most willing to go the extra mile for a story.

“Romy was a myth. He was a force,” wrote another of Romanoff’s former co-workers, sports reporter Norm Reissman. “A little round man who found reams of copy rushing out of his head, a thousand angles there, the moment a story broke. He came alive like a shot of electricity; he was on the phone with an angle on ‘how to get the guts of the story.’ He advised young reporters. He dictated full stories to them, full columns cascading from his system which didn’t know how to stop for a breath of air. And then he’d order a large pizza and invite anyone within earshot to forget the world and eat a little.”

“Romy was a myth. He was a force,” wrote another of Romanoff’s former co-workers, sports reporter Norm Reissman. “A little round man who found reams of copy rushing out of his head, a thousand angles there, the moment a story broke. He came alive like a shot of electricity; he was on the phone with an angle on ‘how to get the guts of the story.’ He advised young reporters. He dictated full stories to them, full columns cascading from his system which didn’t know how to stop for a breath of air. And then he’d order a large pizza and invite anyone within earshot to forget the world and eat a little.”

Chicago journalist George Murray, who worked alongside Romanoff at the Hearst newspaper offices, described him in similarly grand terms in his 1965 book, The Madhouse on Madison Street.

“Harry Romanoff is a non-writing reporter,” Murray wrote, “as are many of the best in the business. He needs only a good rewrite man to capture the drama of the story as he tells it and make it come alive for the reader.

“Like every natural storyteller, Romanoff is an actor. He can be all things to all men, with chameleon-like changes too quick for the eye to follow. The method actors of the Broadway stage could learn from Romanoff to live their parts on a moment’s notice. His only textbooks have been newspapers, but his memory is encyclopedic. For him there is only one goal: Get the story.”

[From left to right: Still from 1931 film adaptation of “The Front Page”; 1967 issue of Chicago’s American, one of the Hearst papers for which Harry Romanoff worked; pinback for the Chicago Herald & Examiner, precursor to the American; and Romanoff’s home office at the Hearst Building, 326 W. Madison St., 1950s.]

As a character quite literally right out of the The Front Page, Romanoff also had few if any qualms about pushing ethical boundaries in order to get that proverbial headline. He regularly made phone calls in phony voices, impersonating everyone from police officers to politicians . . . all in the interest of shaking down a witness for the scoop.

In 1919, while working with the Herald & Examiner, Romanoff famously drew a confession out of a child murderer by presenting him with an emotional visual aid—a doll that had been owned by the victim. In reality, Romanoff had purchased the doll himself earlier that day, but such questionable gamesmanship was widely applauded when it resulted in justice.

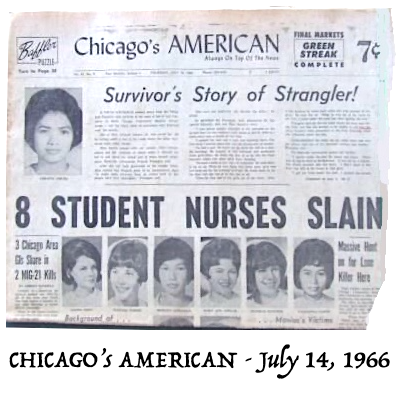

Nearly 50 years later, following the infamous Richard Speck murders in 1966, an aging Romanoff, now city editor for Chicago’s American newspaper, “managed to get the gory details of the deaths from a policeman after introducing himself as the Cook County coroner. He also interviewed the mother of the suspect, Speck, by pretending to be her son’s attorney.”

Nearly 50 years later, following the infamous Richard Speck murders in 1966, an aging Romanoff, now city editor for Chicago’s American newspaper, “managed to get the gory details of the deaths from a policeman after introducing himself as the Cook County coroner. He also interviewed the mother of the suspect, Speck, by pretending to be her son’s attorney.”

Around the same time, when a young reporter named Dorothy Storck was investigating a kidnapping case, Romanoff, as her editor, asked where the ransom note from the kidnapper was. “They didn’t leave a note,” she said. “So what about the note the mother wrote begging her kidnapper to return her baby?” Romanoff snapped back. “She didn’t write a note like that; she’s illiterate,” Storck explained. Deeply annoyed, Romanoff stomped his foot. “So write the note for her!” he ordered. The newspaper did just that and published it the next day.

All of this begs the question: would a single-minded newspaper man like Harry Romanoff genuinely commit his spare time to running a door-to-door, canned spice business? Or did he take on the role at the Empire Spice Mills as part of some lengthy undercover investigation, with the goal of blowing the roof off Chicago’s illegal spice labeling trade?

That certainly would be the more amusing version of events, but alas, no such expose was ever printed as far as we could tell. A little digging reveals that Harry’s younger brother, Reuben Romanoff, also served as an executive with the Empire Spice Mills, further suggesting that this was, indeed, just an innocent side hustle for the Romanoff family, and not a crime reporter’s magnum opus.

[The former headquarters of the Empire Spice Mills MFG Co. at 917 S. Western Ave. is still standing today. The latter era logo of the company’s Burma Brand, seen above, is also still in use today by Consumers Vinegar & Spice, Inc.]

“The Heifetz of the Telephone”

It’s hard to determine what level of success the Empire Spice Mills achieved during its brief run, but with no considerable advertising budget, it seems the business relied mainly on established supply deals with independent shop owners, kitchens, hotels, etc. It might have been a profitable little enterprise, but then again, Harry Romanoff’s judgment wasn’t always razor sharp.

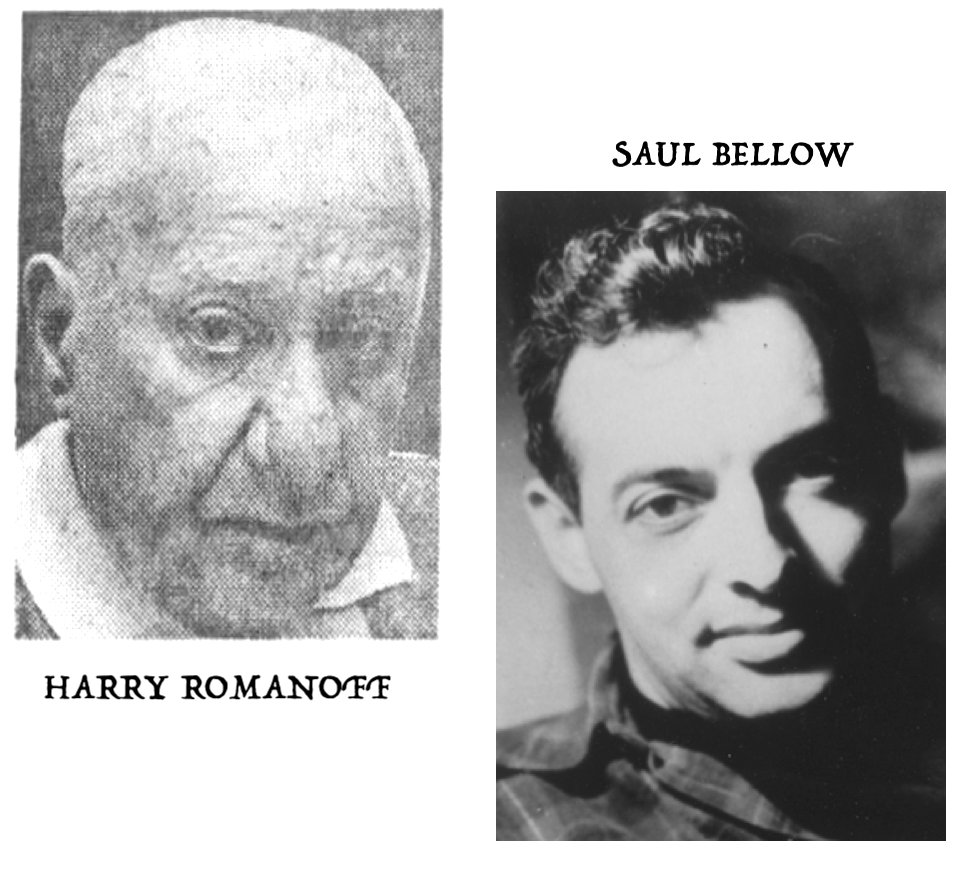

In the 1930s, for example, a young Saul Bellow—future Pulitzer Prize winner—interviewed for a reporting job at the Hearst offices. Bellow would later remember meeting with Romanoff, who “has a nose like a double Alaska strawberry and was well used to dealing with young people like me. He looked me over and said, “You’ll never make a newspaper man, and forget about this writing stuff altogether.’”

It was really persistence, more than perceptiveness, that was Romanoff’s superpower.

It was really persistence, more than perceptiveness, that was Romanoff’s superpower.

“Harry J. Romanoff is the very essence of the high spirit of competition which has made American journalism the safeguard in our society that no constitution in itself can provide,” Congressman Roman C. Pucinski said in the House of Representatives following Romanoff’s retirement from the Chicago Today paper in 1969. “As night city editor, Romanoff has never hesitated to call anyone anywhere in the world if he thought he could develop a fresh lead or a new development in a story for the morning’s edition.

“I do not believe there is a public official of stature in this country who has not experienced a nocturnal call from Romanoff in the middle hours of the night asking about some details regarding a story that ‘Romy’ was developing.”

As Romanoff explained in unapologetic defense of his tenaciousness, “I believe in the public’s right to know. If the story is important to the American people, I have no compunctions about calling their public officials in the middle of the night to get it. . . . I’ve probably spent more than $1 million in phone calls around the world. The phone company even awarded me a statue once.”

[Harry Romanoff was portrayed by actor Joseph Julian (right) in a 1959 episode of the TV series Deadline. The episode, titled “The Case of the Stranger,” was inspired by Romanoff’s role in cracking the real-life “Case of the Ragged Stranger” in 1920. Along with fellow reporters and future “Front Page” scribes Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, Romanoff had helped reveal that suspect Carl Wanderer had actually killed his wife Ruth, despite claiming that he’d tried to save her from a mystery attacker.]

Fall of the Empire

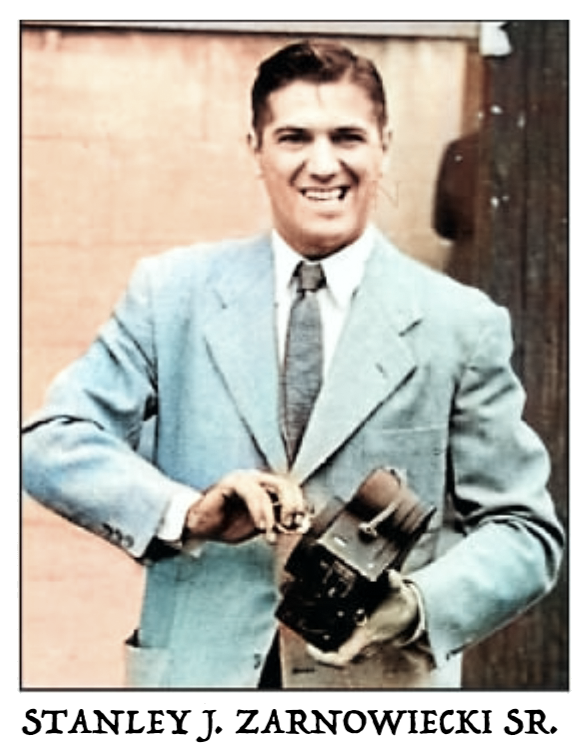

Harry and Reuben Romanoff quietly presided over the Empire Spice Mills through World War II and at least up to 1948. Shortly thereafter, the dots appear to connect to a young Chicago businessman named Stanley J. Zarnowiecki, Sr., a former Oscar Mayer salesman who had recently started his own vinegar supply business. Seeing Empire’s door-to-door spice sales as a comparable business model, he acquired the firm and combined its assets into a new entity, the Consumers Vinegar & Spice Company. That business evolved into more of a bulk supply house later in the 20th century, carried on by Stanley Zarnowiecki, Jr.

“The life of a small business owner can be tough,” Stanley Jr. told the Tribune after his father’s death in 2004. “[Stanley Sr.] was very proud of his business and what he accomplished. He was a go-getter who saw an opportunity.”

“The life of a small business owner can be tough,” Stanley Jr. told the Tribune after his father’s death in 2004. “[Stanley Sr.] was very proud of his business and what he accomplished. He was a go-getter who saw an opportunity.”

As of 2023, Consumers Vinegar & Spice was still selling spices online under the Burma brand name and logo.

Harry J. Romanoff died in 1970 at the age of 79, less than a year after his retirement from the newspaper biz. Lloyd Wendt, his publisher at Chicago Today, remembered him as “one of the great reporters of our time—or any other time.” Romanoff’s association with the Empire Spice Mills was never mentioned in any of his obituaries or much of anywhere else outside business directories. His brother Reuben’s obituary in 1973, however, re-established the connection, noting that Reuben Romanoff had also been an owner of the Empire Spice Mills prior to joining his brother Harry full-time in the newspaper world in the early 1950s.

[More recent Burma Brand offerings from the trademark’s current owner, Consumer Vinegar & Spice Co.]

Sources:

“Spice Mills Lease Part of Former Baking Plant” – Chicago Tribune, Feb 6, 1938

Notices of Judgment Under the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, 1940

The Madhouse on Madison Street, by George Murray, 1965

Hon. Roman C. Pucinski of Illinois – Extensions of Remarks, U.S. House of Representatives, June 11, 1969

“Cite Press Vet” – Chicago Tribune, October 16, 1970

“Romanoff, Ex-Today Editor, Dies” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 19, 1970

“A Legend? No Sir, Romy Was for Real” – Stickney Life and Forest View, Dec 27, 1970

“Reuben W. Romanoff” [obit] – Chicago Tribune, May 30, 1973

“Bellow: Chicagoan and Failed Newsman” – Des Moines Tribune, Feb 5, 1977

“No Love Lost on Press Now” – Philadelphia Inquirer, Sep 24, 1980

Readings in Mass Communication, by Michael C. Emery and Ted Curtis Smythe, 1980

“Entrepreneur Built Vinegar, Spice Firm” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 11, 2004