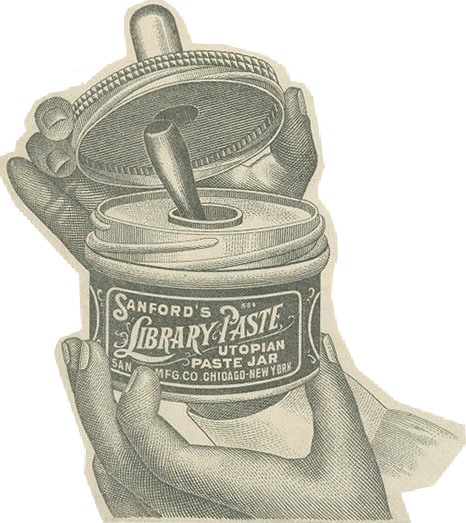

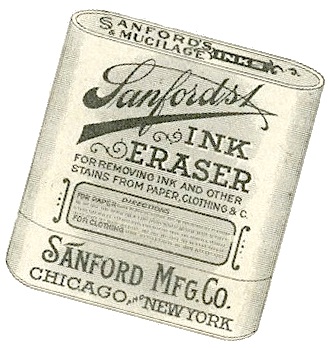

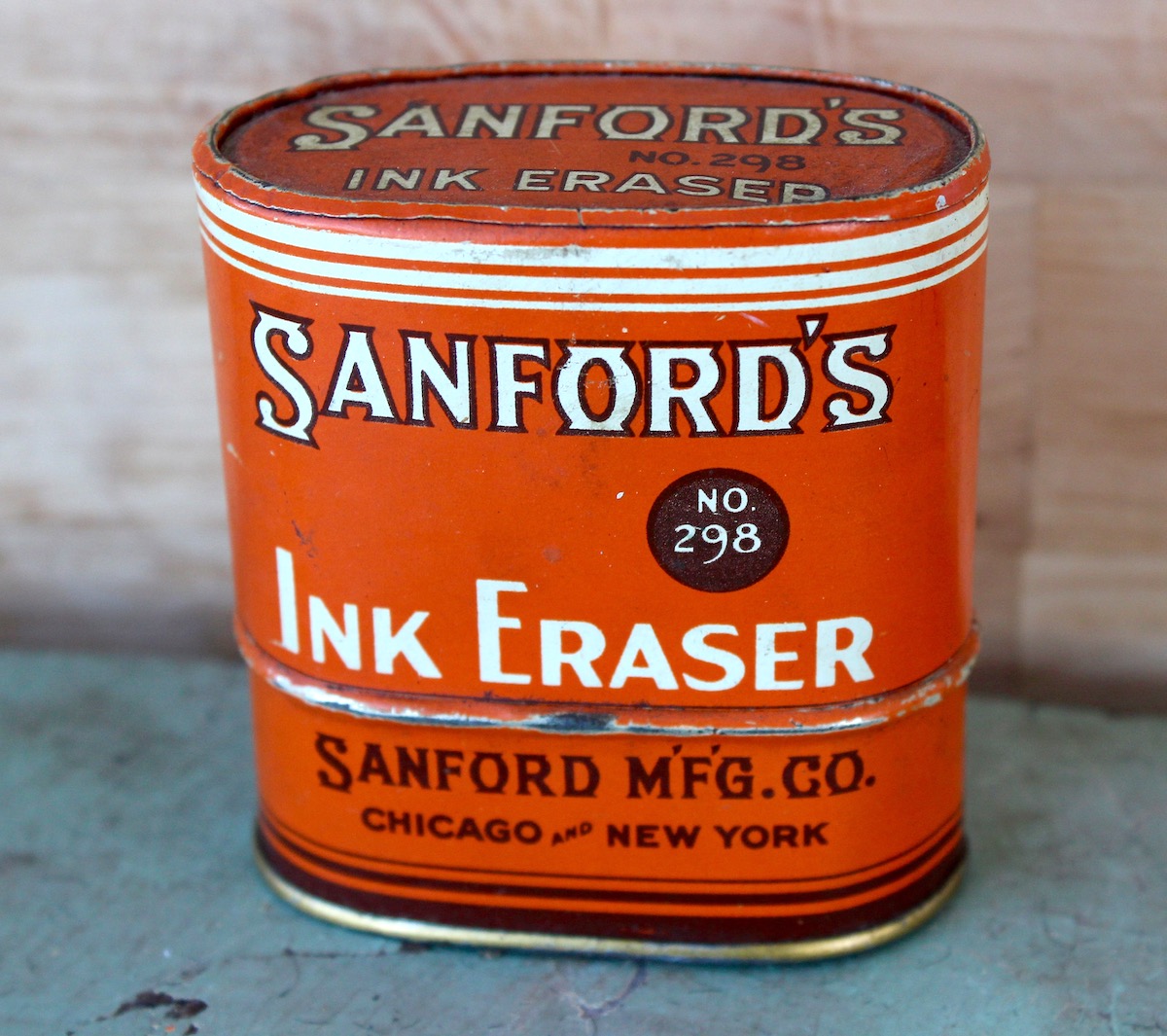

Museum Artifact: Sanford’s Ink Eraser by Sanford MFG Co., c. 1910s

Made By: Sanford MFG Co. / Sanford Ink Company, 846-854 W. Congress Street, Chicago, IL [Near West Side]

“Have you handled Sanford’s ink eraser yet? Every office needs it and every stationer should carry it in stock. It does the work of erasing ink from paper and stains from cloth perfectly. It is put up in a handsome round corner package and is made by the Sanford Manufacturing Company, of Chicago and New York.” —The American Stationer magazine, February 24, 1900

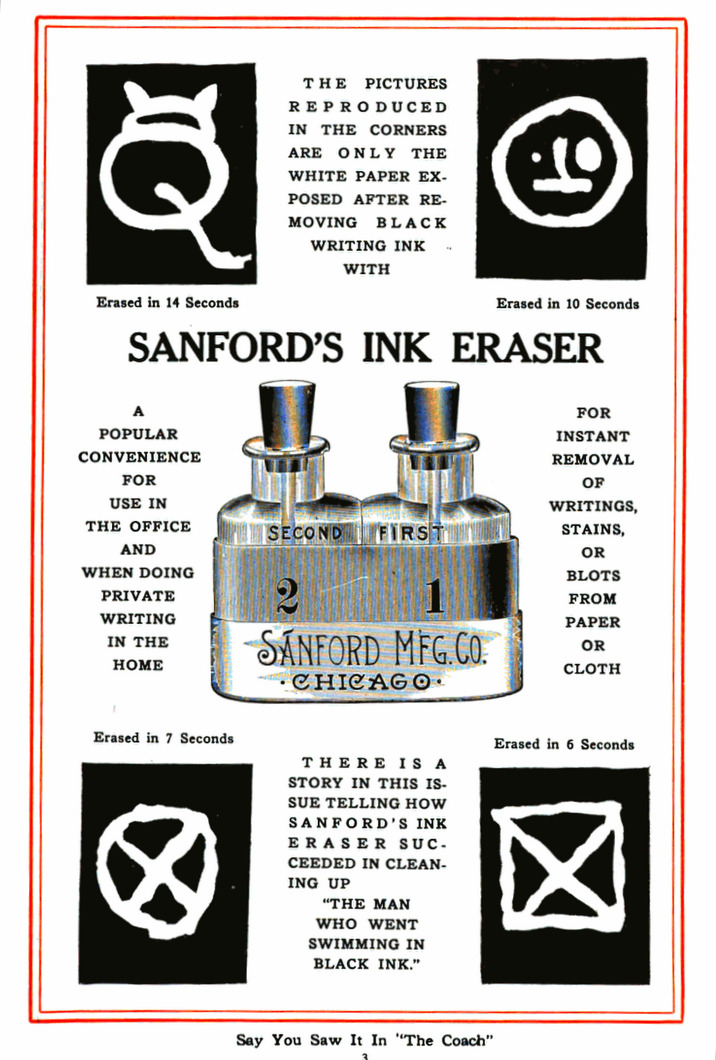

More than half a century before Liquid Paper, Wite-Out, and other correction fluids arrived on the typist’s desk, and at least 30 years before the invention of what Wikipedia calls “the first chemical ink eraser” (propaganda floated by the German manufacturer Pelikan), Chicago’s Sanford MFG Co. was already producing and selling a popular bottled solution for “removing ink and other stains from paper, clothing etc.” Cataloged as item No. 298, it was marketed simply as “Sanford’s Ink Eraser”—as evidenced by the 100 year-old artifact in our museum collection.

It was maybe a bit odd that Sanford—a well-established firm known for touting its reliable line of “permanent” inks—would then develop a product diametrically opposed to that very assertion. The maneuver proved both proactive and profitable, however, and kept No. 298 on the shelves at hardware stores and craft shops for decades.

It was maybe a bit odd that Sanford—a well-established firm known for touting its reliable line of “permanent” inks—would then develop a product diametrically opposed to that very assertion. The maneuver proved both proactive and profitable, however, and kept No. 298 on the shelves at hardware stores and craft shops for decades.

Back in the day, companies didn’t have to list the chemical components of their formulas on the bottle, so the magic of the early Ink Eraser and its corked 2-bottle system are slightly mysterious. Most likely, Bottle No. 1 was something like potassium permanganate, and Bottle No. 2 was akin to photographers hypo solution. According to the instructions, you would begin by applying No. 1 to the paper, “rub gently until the ink has softened, then blot off and apply No. 2 until the ink has disappeared. Then apply No. 1 again until the two fluids are neutralized, and dry with a blotter.” Ugh, a bit much effort. But beggars can’t be choosers.

By the 1960s, when better alternatives finally edged out the old two-bottle approach, Sanford suffered no ill effects. Ink erasing was always a relatively small part of their game, and the company’s most famous creation, the Sharpie marker, was was about to make them a fortune.

Today, Sanford L.P.—headquartered in nearby Oak Brook, IL—has evolved into one of the largest stationery products manufacturers in the world, with not only Sharpie under its banner, but major brands like Paper Mate, Elmer’s, X-Acto, and Krazy Glue, to name a few. In one sense, the business is still in the “inks and mucilage” trade, just as it was 160 years ago. Much of that early history, however—including the story of Mr. Sanford himself—has been forgotten; wiped away like an application of ink eraser . . . until now!

[Sanford’s Ink Eraser was packaged in this style, with a #1 and #2 solution, for more than 50 years.]

[Sanford’s Ink Eraser was packaged in this style, with a #1 and #2 solution, for more than 50 years.]

History of the Sanford Ink Company, Part I: Sanford & Son

Just about every existing version of the Sanford origin story makes surprisingly brief mention of the company’s founder and namesake, William Howe Sanford, Jr. The synopsis usually goes like this one, taken from Sharpie.com: “In 1857, Frederick W. Redington and William H. Sanford, Jr. founded the Sanford Manufacturing Company in Worcester, Massachusetts. In 1866, the company expanded and relocated to Chicago.”

From there, William Sanford is generally never mentioned again. Weird, huh?

From there, William Sanford is generally never mentioned again. Weird, huh?

For a while, I presumed this was simply due to a lack of surviving information about a small business finding its footing in the midst of the Civil War. But a little digging at least shines a tiny bit more light on the real narrative.

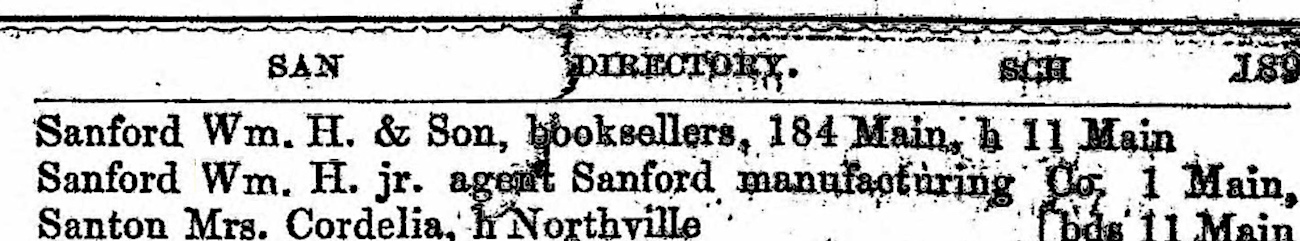

As it turns out, William H. Sanford Jr., at age 21, started the Sanford Manufacturing Company as a supplier of inks and glues to the Worcester bookseller and stationery shop run by his own father, Rev. William H. Sanford, Sr. The reverend’s establishment was known as Sanford & Co., or alternately—and I kid you not—”Sanford & Son.”

[The 1866 Worcester, Mass directory reveals William H. Sanford Jr. still running the Sanford MFG Co. locally, with his dad’s shop, Sanford & Son booksellers, also in business.]

[The 1866 Worcester, Mass directory reveals William H. Sanford Jr. still running the Sanford MFG Co. locally, with his dad’s shop, Sanford & Son booksellers, also in business.]

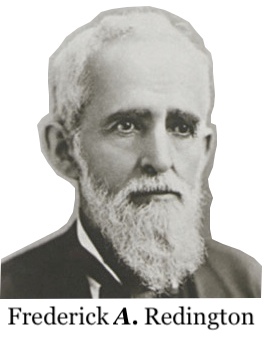

There is no evidence, meanwhile, that Frederick Redington had any involvement with the Sanford business in its early years in Worcester. Aside from being 20 years older than Sanford Jr., Redington (b. 1815) was still working as a hardware merchant in Pomfret, New York, as late as 1865, with a brief service in the Union Army mixed in. Our best guess is that Redington first became aware of Sanford inks and/or mucilage by ordering them for his own shop, then decided to invest in the business after the war. The decision to move Sanford’s operations from Worcester to Chicago, then, becomes a whole other can of worms.

Some say the migration was decided on after the Worcester plant burned down, while others cite an ambitious agreement between Redington and Sanford to conquer the Western market. The one thing rarely if ever mentioned, however, is that young William Sanford Jr. suffered from Brights Disease; a serious kidney ailment known today as Glomerulonephritis, or GN. It had likely kept him off the battlefield during the Civil War, and it ultimately took his life in the spring of 1868, at just 32 years of age. Sanford was still living in Worcester at the time of his death, and never got to see his small business thrive in Chicago. He wouldn’t have imagined that his surname would live on through a multi-national corporation in the 21st century.

[Photo: Grave of William H. Sanford, Jr., 1835-1868, at the Worcester Rural Cemetery in Worcester, MA]

[Photo: Grave of William H. Sanford, Jr., 1835-1868, at the Worcester Rural Cemetery in Worcester, MA]

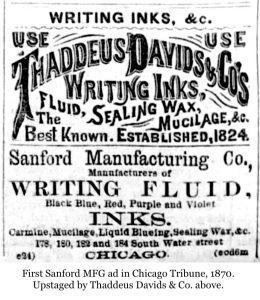

The first mention of the Sanford Manufacturing Company in the Chicago Tribune archives doesn’t appear until two years later, 1870; the same year in which Frederick A. Redington*is listed in the U.S. census as living in Chicago and employed as “secretary of the Sanford MFG Co.” This suggests that Redington might have made the move to Chicago after, rather than before, William Sanford’s death.

Either way, it’s interesting that the Sanford name was never abandoned, even as the business clearly became the Redington family’s enterprise. A tribute to a departed friend, perhaps. Or just a case of sticking with a brand name that had already built a good reputation.

*Speaking of names, many modern sources, including Sharpie.com, cite the co-founder of Sanford Ink as Frederick W. Redington, but actual census, military, and newspaper records make it pretty clear that Fred’s middle initial was actually “A” for Augustus. I’m certainly happy to debate this obscure, relatively meaningless factoid with any remaining members of the Redington clan or reps of Sanford L.P.

Anyway, we’ll never know if a healthy William Sanford Jr. might have kept the ink business on the East Coast. But it’s certainly safe to assume that Frederick Redington didn’t pick Chicago by throwing a dart at a map. The rapidly growing city was wooing ambitious industrialists of all sorts, and the market for fountain pen inks was still very much up for grabs in America’s mid-section.

Anyway, we’ll never know if a healthy William Sanford Jr. might have kept the ink business on the East Coast. But it’s certainly safe to assume that Frederick Redington didn’t pick Chicago by throwing a dart at a map. The rapidly growing city was wooing ambitious industrialists of all sorts, and the market for fountain pen inks was still very much up for grabs in America’s mid-section.

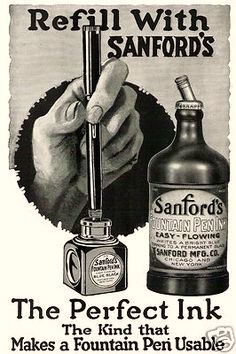

In the late 1800s, bottled inks weren’t just vital to businessmen and bookkeepers. American expansion was creating an ever greater distance between new settlers and their friends and loved ones back home. And with the telephone still in its infancy, it was written correspondence—with durable inks—that most folks relied on. Either by coincidence or calculation, Sanford’s products were now there to help all of those homesick souls and weary travelers put pen to paper.

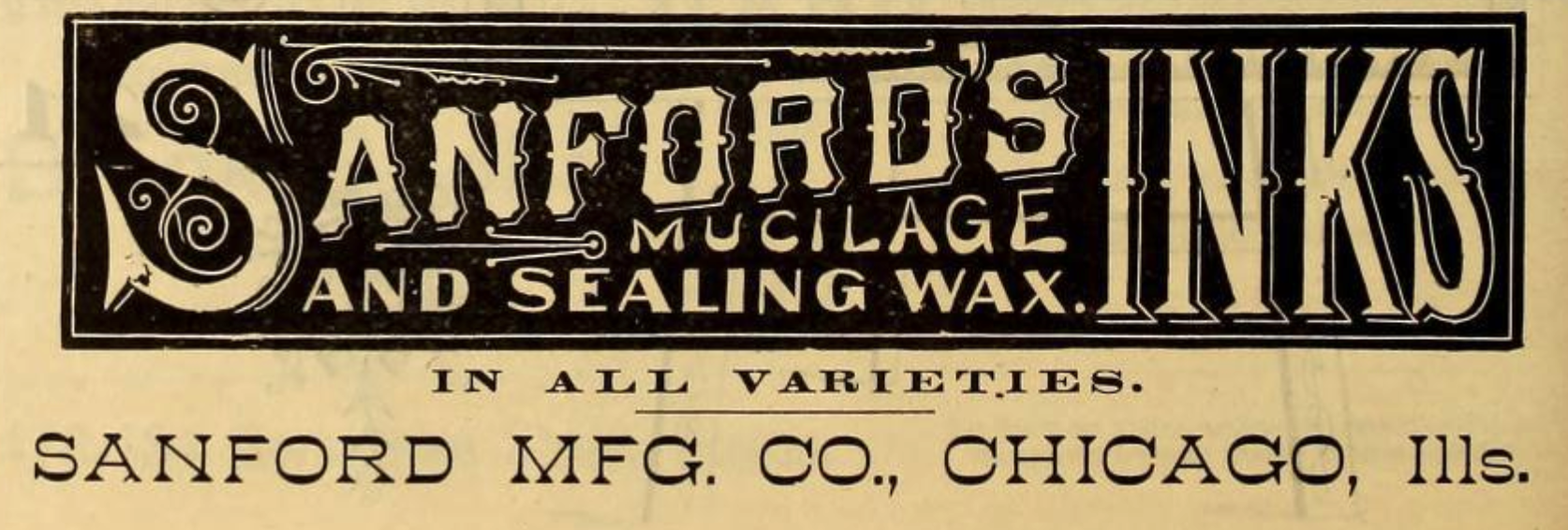

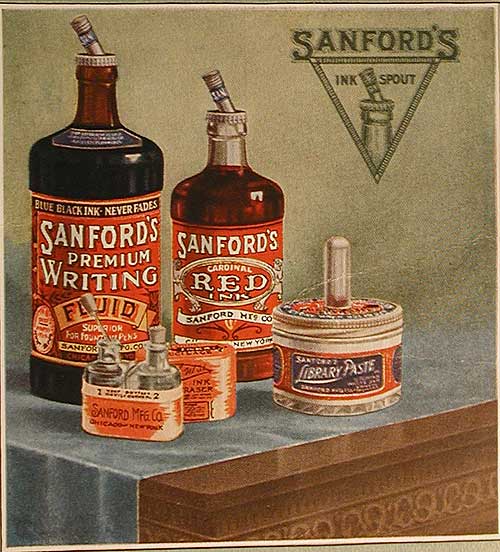

[Sandord MFG Co. advertisement from the American Stationer, 1882]

[Sandord MFG Co. advertisement from the American Stationer, 1882]

II. Ink, Inc.

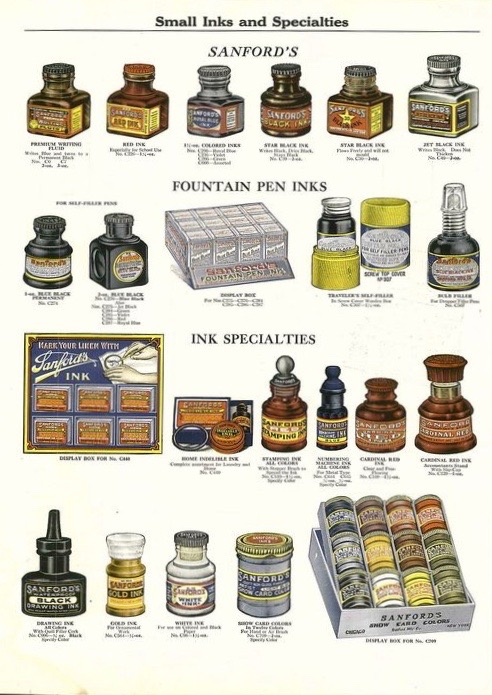

“The growth of the Sanford Manufacturing Company, of Chicago, in the past few years has been wonderful,” the American Stationer reported in 1885. “Its inks and mucilage are now sold in every State and Territory in the Union and in a number of foreign countries. . . . The company is now making twenty different kinds of writing inks, sealing wax of all qualities, and four grades of mucilage. It also controls a number of valuable patents pertaining to the business, among which, familiar to the public, may be mentioned its ‘Universal’ inkstand. This consists of a metal cover, spun on the neck of an ordinary ink bottle. The cover turns either to the right or left, and is easily opened or closed. After the cork is drawn it may be thrown away, leaving nothing to soil the writer’s fingers or table.”

Quality products and innovative, stylish bottles made Sanford a household name, and the company found capable young leadership in the form of Frederick Redington’s son, William H. Redington (1851-1923), who continued to steer the ship after his father’s death in 1893 [a much younger son, Frank B. Redington (1866-1954) also worked for the business, but eventually found his fortune first as the superintendent for the Zeno Gum Company, then as the head of his own business, the F. B. Redington Co.—but that’s a whole other story].

Quality products and innovative, stylish bottles made Sanford a household name, and the company found capable young leadership in the form of Frederick Redington’s son, William H. Redington (1851-1923), who continued to steer the ship after his father’s death in 1893 [a much younger son, Frank B. Redington (1866-1954) also worked for the business, but eventually found his fortune first as the superintendent for the Zeno Gum Company, then as the head of his own business, the F. B. Redington Co.—but that’s a whole other story].

The Chicago era was not all growth and glory, of course. There was competition from patent thieves, the consistent threat of worker strikes, and—most troubling of all—the occasional billowing factory fire to deal with.

The first Sanford plant in the city, at 184 South Water Street, had been rudely wrecked (like everything else) by the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, forcing a rebuild at 151 Monroe Street. But it was the company’s next plant—a large facility at Sangamon and Fulton Street that stood for 20 years—that really went out in its own spectacular, uniquely colorful blaze of glory.

“Filling nearly all the floor space on the three upper stories were forty huge wooden tanks, each holding 1,000 gallons of ink,” the Chicago Tribune reported on November 28, 1900. “While the fire was at its height the floors began to give way under their burden, and the big tanks went crashing through to the basement, filling it with fluids which tinged the flood of water coming from the fire engines. Streams of red and blue and green ink trickled across the sidewalk and mingled in a variegated rivulet that was discernible for a block away.”

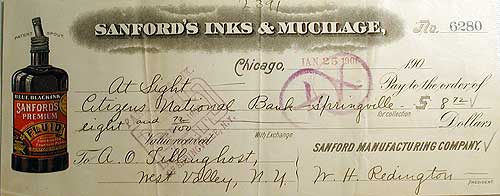

[Check dated from January 1900, signed by company president William Redington. The Sanford factory would burn to the ground later that year.]

[Check dated from January 1900, signed by company president William Redington. The Sanford factory would burn to the ground later that year.]

The 1900 blaze, which also claimed the first floor business of a Sanford subsidiary, the L. H. Thomas Company, wiped out a massive back-stock of products (including the newly introduced Ink Eraser) and left 90 Chicago employees in the lurch.

“Our loss is total,” company secretary William Rodiger told reporters. “But we will resume business without any delay. We hope to start up inside three weeks, although the manufacturing process cannot be put under way in less than three months. It takes that time for a tank of ink to reach the proper stage for bottling.”

To get over the hump, more responsibility was saddled on Sanford’s satellite offices in New York, but by 1902, president William Redington proudly opened the company’s new five-story Chicago headquarters at Congress and Peoria Street (846 W. Congress St., to be exact). By 1907, there were 125 workers employed there, evenly split between men (64) and women (61).

To get over the hump, more responsibility was saddled on Sanford’s satellite offices in New York, but by 1902, president William Redington proudly opened the company’s new five-story Chicago headquarters at Congress and Peoria Street (846 W. Congress St., to be exact). By 1907, there were 125 workers employed there, evenly split between men (64) and women (61).

III. Simply Redington

Much like Chicago itself, the Sanford MFG Co. had somehow used a cataclysmic inferno to fuel its resurgence. This momentum continued through World War I, around the time our featured Ink Eraser bottle was likely made. While most manufacturers were forced to divert their efforts into government work, Sanford had the benefit of sticking to its normal stock and trade, as inks and glues were always deemed “necessities” for the public good. The company proudly touted this in advertisements during the period:

“In a time like the present, when the whole world is in confusion, many articles of daily use can be slighted for the reason that their importance is not of long duration. It is not so with Writing Inks; the quality must be maintained in some way. Records, deeds, Government papers of all kinds must be permanent, otherwise the future will have many serious developments if our records fade out. Therefore, every stationer must look well to his stocks of Writing Inks and be able to give his customers reliable quality whatever the cost may be. … This means the best, represented by the Sanford line of Writing Inks…”

“In a time like the present, when the whole world is in confusion, many articles of daily use can be slighted for the reason that their importance is not of long duration. It is not so with Writing Inks; the quality must be maintained in some way. Records, deeds, Government papers of all kinds must be permanent, otherwise the future will have many serious developments if our records fade out. Therefore, every stationer must look well to his stocks of Writing Inks and be able to give his customers reliable quality whatever the cost may be. … This means the best, represented by the Sanford line of Writing Inks…”

Much of Sanford’s identity and reputation within the industry was still tied to its well liked president William H. Redington, a down-to-earth chap who had grown up in the business, and seemed equally skilled working in product development and sales. When he wasn’t off on a long fishing trip in Wisconsin, he was on the trade show circuit, mixing it up with colleagues and competitors, or penning editorials for industry tabloids.

“One of the most frequent reasons for complaint on Writing Inks,” Redington wrote in a 1917 issue of the trade publication The Coach, “is caused by the customer not getting the kind of ink he should have. To some people, ink is ink, not realizing that there are different kinds. One may as well say, girls are girls, but there is always one that is best, ‘the lasting kind.’”

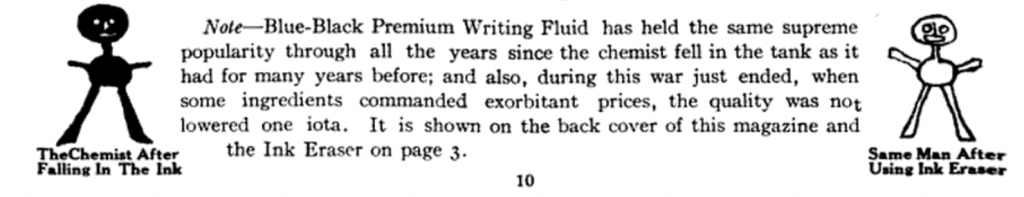

Two years later, the same publication printed another Sanford ad masquerading as an article, this time recounting an anecdote that William Redington had supposedly shared with some dealers at a Chicago auto show. He might very well have told the story, too, if only because it sounds mildly racist enough to be genuine Jazz Age convention chatter. The piece was called “About the Man Who Went Swimming in Black Ink,” and deftly manages to promote both Sanford’s permanent ink and its famous No. 298 Ink Eraser.

Two years later, the same publication printed another Sanford ad masquerading as an article, this time recounting an anecdote that William Redington had supposedly shared with some dealers at a Chicago auto show. He might very well have told the story, too, if only because it sounds mildly racist enough to be genuine Jazz Age convention chatter. The piece was called “About the Man Who Went Swimming in Black Ink,” and deftly manages to promote both Sanford’s permanent ink and its famous No. 298 Ink Eraser.

“Gentlemen,” says Redington, “I wonder if it would please you to hear how once, over at our factory, the master chemist was baptized, regardless of his faith, in a deep tank of black ink, and how we cleaned him up so his wife wouldn’t mistake him for a fugitive slave when he came in the door at his home that night?”

The dealers are all, of course, interested to hear the tale, so Redington describes how this likely imaginary chemist used to stir a vat of Sanford’s superior blue-black Premium Writing Ink while standing precariously on a wooden board above the open vat.

“One day he worked too vigorously and the board suddenly broke,” Redington continues. “Well, when he came to the surface he could swim all right, but he was so intensely black all over that at first we thought the colored population of Chicago had been suddenly increased by one; however, one of the men promptly said, ‘SCRUB HIM IN INK ERASER,’ and that is just what we did, and we made a pretty good job of it too except for his eyes, ears, finger and toe-nails. If we had not scrubbed him up immediately but had left the ink on him for a day or two he would have been black for life.”

“One day he worked too vigorously and the board suddenly broke,” Redington continues. “Well, when he came to the surface he could swim all right, but he was so intensely black all over that at first we thought the colored population of Chicago had been suddenly increased by one; however, one of the men promptly said, ‘SCRUB HIM IN INK ERASER,’ and that is just what we did, and we made a pretty good job of it too except for his eyes, ears, finger and toe-nails. If we had not scrubbed him up immediately but had left the ink on him for a day or two he would have been black for life.”

The same page in The Coach even provided this fantastic illustration of the Sanford chemist, first doused in high-quality Premium Writing Ink, then saved by amazing Ink Eraser!

Marketing of this sort might seem hokey, and it doesn’t age well, but at the end of a war and the dawning of the Roaring ’20s, it gave the Sanford MFG Co. a charming, light-hearted appeal fit for the times. Many customers became devotees of the brand, and stuck with it even during the downturn of the Depression.

IV. Bellwood Bound

The outlook was considerably different for Sanford coming out of the Second World War. In the 1940s, growing competition from dreaded ballpoint pens and instant-drying inks—like those created by the Frawley Pen Company and its “Paper Mate” brand—had Sanford suddenly falling behind in the marketplace. Its stellar reputation now doubled as an albatross around the neck, as buyers associated some of its products with a bygone era.

[The No. 298 Ink Eraser and No. 98 White Ink containers pictured above are both part of our museum collection, and likely date from the 1930s or early ’40s. No. 98 ink was designed “for use on photographs, blueprints, and dark colored papers.”]

[The No. 298 Ink Eraser and No. 98 White Ink containers pictured above are both part of our museum collection, and likely date from the 1930s or early ’40s. No. 98 ink was designed “for use on photographs, blueprints, and dark colored papers.”]

There was another looming problem that the company couldn’t have anticipated. After the war, plans went forward for a new superhighway that would replace part of Congress Street in downtown Chicago. Interstate 290, which would later be known as the Eisenhower Expressway, was basically going to run directly through Sanford’s backyard. They would have to abandon the factory they’d called home for nearly 50 years.

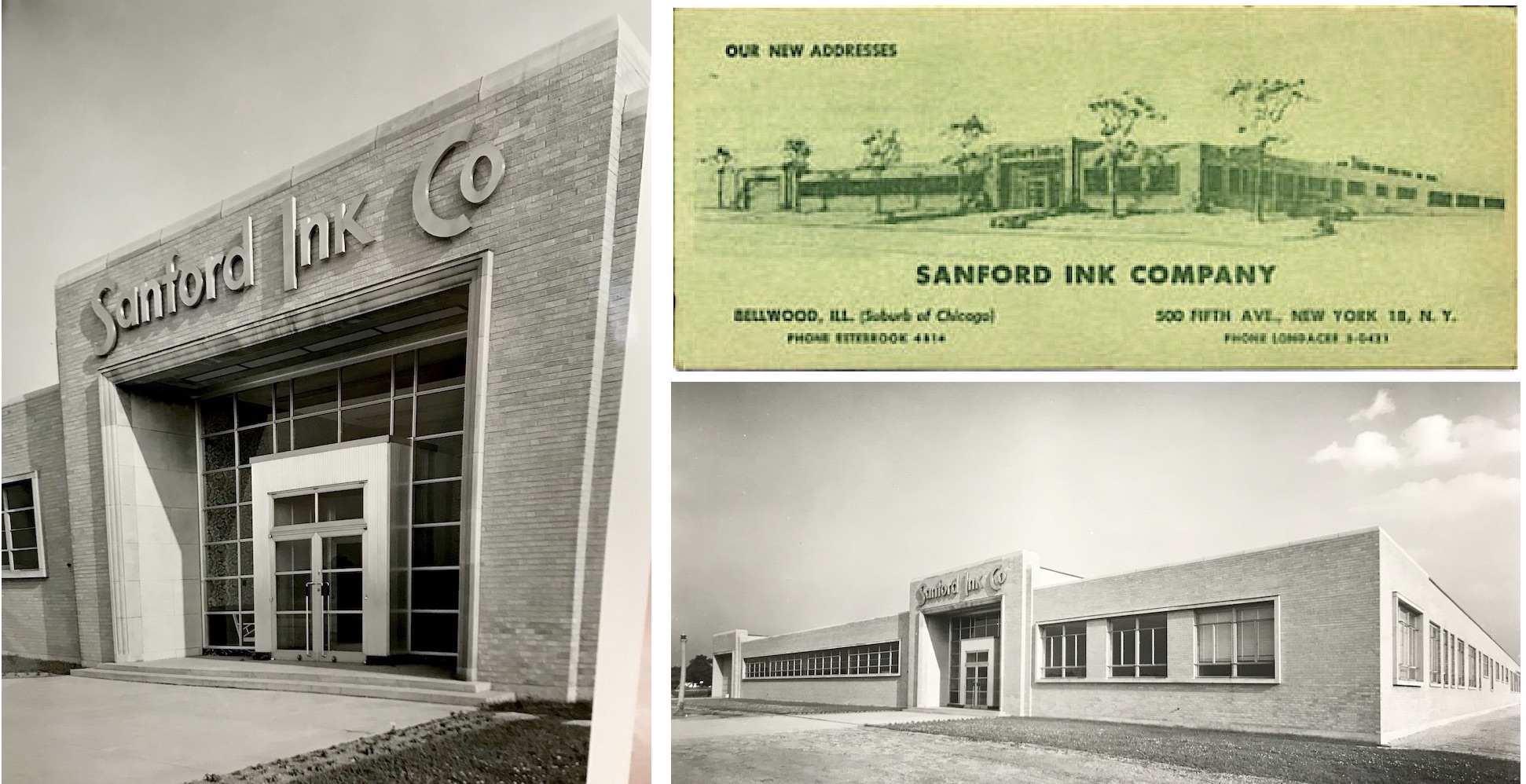

In 1947, following a trend of the times, the company relocated to the suburbs, moving into a modern, 76,000 sq. ft., one-story plant in Bellwood, Illinois, about 13 miles outside of town. Meanwhile, in an interesting twist, the old factory on Congress Street actually survived the highway project, as the city made the ambitious decision to lift the entire structure from its moorings and transport it a block south to the corner of Peoria Street and Harrison Street. This took place in 1949, but may not have been worth the effort in the long run. The structure has long since been demolished. The Bellwood plant, meanwhile, is still standing today, albeit usually advertising for new tenants.

[The Sanford Ink factory at 2740 W. Washington Blvd. in Bellwood, IL. As seen in 1948 and today. Newell-Rubbermaid shut down the plant in 2004.]

[The Sanford Ink factory at 2740 W. Washington Blvd. in Bellwood, IL. As seen in 1948 and today. Newell-Rubbermaid shut down the plant in 2004.]

The beginning of the Bellwood era saw the business now operating officially as the Sanford Ink Company (soon to become Sanford Corp.), with a trimmed down workforce (about 100 employees in 1950) and a more streamlined, automated manufacturing and bottling process. The company’s leadership included chairman Russell Carpenter, who’d joined the business just after William Redington’s death back in 1923, plant manager Howard Jorgensen, and a chain-smoking, lion-voiced workaholic president named Charles W. Lofgren (1907-1985).

According to former Sanford Ink chemist Bill Green, “Charlie [Lofgren] wasn’t just in charge of everything that happened at Sanford, he also knew everything that happened at Sanford, and the two are not always the same thing. Furthermore, whatever happened at Sanford was what Charlie wanted to happen at Sanford. Those two were the same thing. When things went array as they sometimes did, Charlie would fix them.”

Lofgren could be overbearing at times, but working with Bill Green and other bright minds at the Bellwood plant, he eventually helped secure Sanford’s survival and the creation of its biggest single innovation.

[Workers at Sanford’s Bellwood factory, 1948]

[Workers at Sanford’s Bellwood factory, 1948]

V. The Sharpie Era

Sustaining a successful business is a bit like running a marathon . . . inside a maze. There are no straight-aways, only an endless series of intersections and hard choices to make. As a result, the Made-In-Chicago Museum is littered with companies that thrived for a generation or two, only to then inevitably swerve off course—either failing to foresee a new emerging trend or surrendering to foreign competition. This makes the Sanford Ink Company the rare exception that proves the rule. Where other ink makers splattered against the wall, Sanford drew themselves a tunnel right through it.

Private ownership and bold leadership, dating back to Frederick Redington’s day, seemed to be a key factor, and Charles Lofgren was no exception.

“No one ever questioned who controlled everything that happened at Sanford,” says Bill Green, who started working for Sanford in the 1960s, and shares his memories on his own website, Sharpie Stories. “Charlie was Number One. If you wanted to call him on the company phone, you simply picked it up and dialed 1. . . . When he walked into a room, he took all the oxygen out of it. He talked, we listened. He asked questions, we gave answers. And we gave answers knowing he was not only listening, but analyzing.”

“No one ever questioned who controlled everything that happened at Sanford,” says Bill Green, who started working for Sanford in the 1960s, and shares his memories on his own website, Sharpie Stories. “Charlie was Number One. If you wanted to call him on the company phone, you simply picked it up and dialed 1. . . . When he walked into a room, he took all the oxygen out of it. He talked, we listened. He asked questions, we gave answers. And we gave answers knowing he was not only listening, but analyzing.”

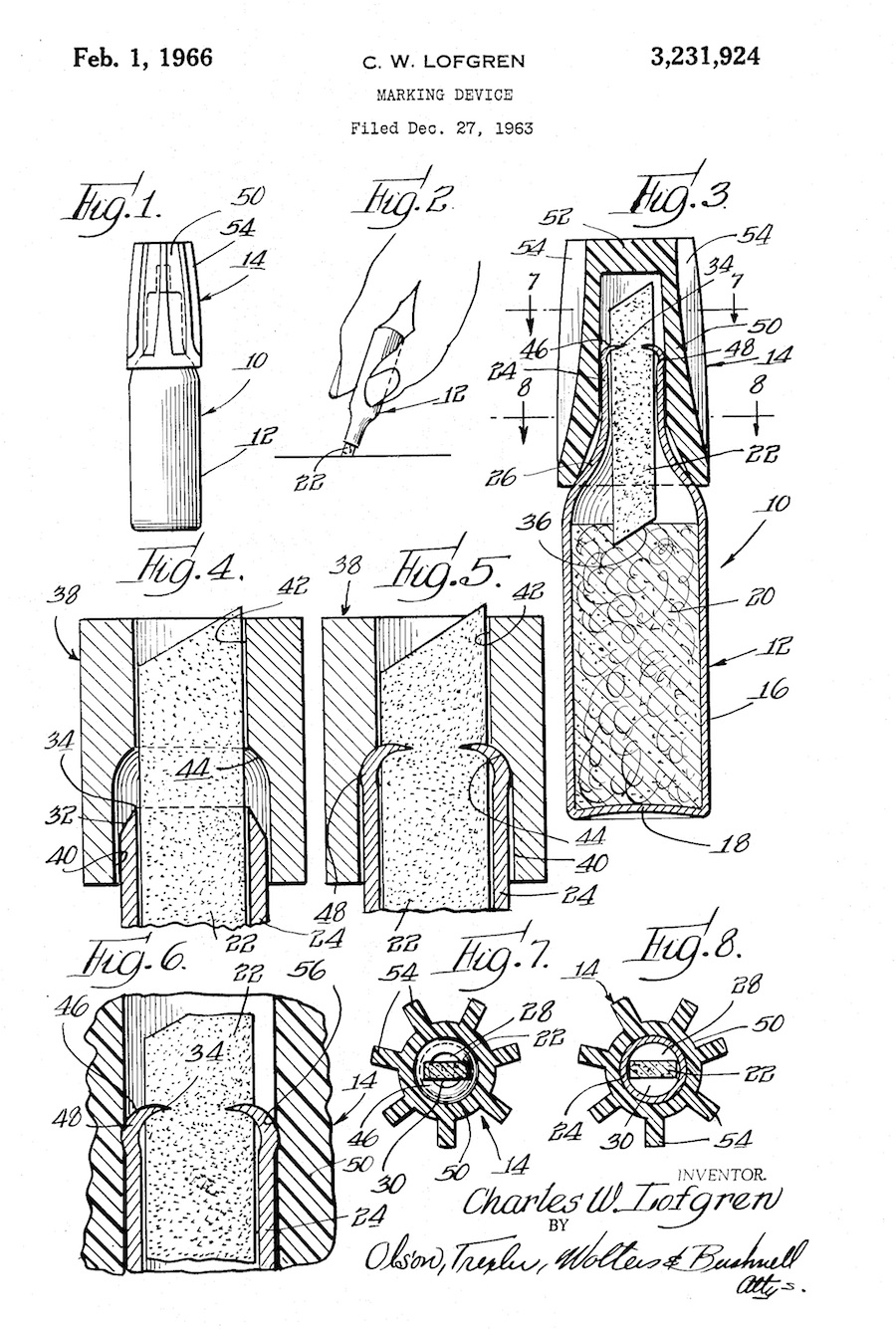

In 1964, right around the time the ballpoint pen was overtaking the old nib fountain pen as America’ preferred writing stick, Sanford needed a Hail Mary pass to ensure its continued relevance in the industry. Their solution, developed and refined by Lofgren’s VP and lead chemist, Francis Gilbert (along with Green and Keith Beal), was a pen-like, felt-tipped permanent marker that could write cleanly on virtually any surface. The “Sharpie,” as they called it, not only sent the business to unexpected new heights, but also—ironically—helped bring some permanence to a long legacy that otherwise might have faded into obscurity.

[Patent for one Charles Lofgren’s marking devices at Sanford in the mid 1960s]

[Patent for one Charles Lofgren’s marking devices at Sanford in the mid 1960s]

“As I think back on that part of my life,” Green says, “I indeed take great pride in what was accomplished. The Sharpie has been produced and sold for many years now. It has provided many jobs right here in America. Many of my personal friends from those days spent their entire careers producing and selling Sharpies, and are now enjoying retirement funded by Sharpie’s success. I like to brag that more people have used the Sharpie than have watched Michael Jordan play basketball, both live and on television.

“And now, looking back on what happened and who made it happen, I am finally beginning to realize the significance of it. A small group of men in a small private company developed and produced a product that has been used by almost all Americans old enough to do so, as well as many people around the world. It has become a piece of Americana.”

Even after the explosive resurgence spurred by Sanford’s Sharpie success, the company remained privately held and a bit private by nature, as well, as Charlie Lofgren preferred it. When Lofgren’s son-in-law Henry Pearsall was elevated to the presidency in 1979, the young lawyer admitted to the Tribune that, “Although we sell in over 70 countries, we’ve tried to maintain a very low profile.”

This philosophy soon changed, however, and by 1984, Sanford’s majority ownership was sold to members of its management team and a group of eager investors. Lofgren, who’d been serving as chairman, stepped down, and died shortly thereafter. By the summer of ’85, Sanford Corp. went public for the first time; a move that Pearsall admitted wouldn’t have thrilled his late father-in-law. “[Charles Lofgren] was the most secretive of men,” he said. “If he were alive today, he’d be sick.”

This philosophy soon changed, however, and by 1984, Sanford’s majority ownership was sold to members of its management team and a group of eager investors. Lofgren, who’d been serving as chairman, stepped down, and died shortly thereafter. By the summer of ’85, Sanford Corp. went public for the first time; a move that Pearsall admitted wouldn’t have thrilled his late father-in-law. “[Charles Lofgren] was the most secretive of men,” he said. “If he were alive today, he’d be sick.”

There were no such ill feelings from the surviving Sanford executives, of course, who all benefitted from the massive financial windfall. The modern era of the business was underway.

By 1991, Sanford Corp. had been acquired by Newell Brands (which became Newell-Rubbermaid in 1999), and in 2004, the shutdown of the Bellwood plant began, putting 250 employees out of work. As part of the supergiant Newell conglomerate, though, Sanford L.P., and the name of an otherwise forgotten Massachusetts ink maker, carries on. As of yet, un-erasable.

Sources:

The American Stationer, Feb 24, 1900

“Ink and Water in Fire” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 28, 1900

“William Howe Sanford” – FindaGrave.com

“Selling Writing Inks Intelligently,” by William Redington, The Coach, No. 5, Vol. 4, Sept-Oct, 1917

“About the Man Who Went Swimming in Black Ink” – The Coach, No. 2, Vol, 6, March-April, 1919

“Sanford Likes Privacy” – Chicago Tribune, May 7, 1979

“Stock Issue Potential Goldmine to Sanford Management” – Chicago Tribune, July 10, 1985

Archived Reader Comments:

“Hello, I found the base of a Sanford ink bottle in a nearby ghost town. It has “Sanford around the edge, a “39” in the center, and then something on the bottom that’s very hard to discern – possibly “IJ” or “13.” Do you have any ideas of the approximate age range of such a bottle. Thank you! p.s.: Beautiful website you have – very enjoyable to read and great photos!” —Cindy Humphries, 2020

I have a SANFORD sidetrac pen model # 72101 and would like to purchase 2 more how can I do this ?

I have an old

Bottle

That is imprinted Sanford ink I’m

Sure one of the first bottles

Before labels

Anyone have any idea when the first ink bottles

Was

Made I’m sure when they opened let me

Know . This bottle is small and I’m

Mint

Condition

Thanks

I have a Sandford’s crock. On the bottom are numbers 150- 82. It is a grayish white with beautiful blue writing. Says Sanford’s inks the dependable lines and pastes, Illegal to refill this jar for resale.. Iam have trouble trying to date this and the worth if any. Thank you

I was one the members of Sr management who purchased the company from family members in 1982 as I recall. I am now 84 and had never read the complete Sanford story. I began in sales in 1968 moved to Bellwood office in 1974 as a regional sales manager. Many meetings with Lofgren and Bob Bergdoll lasting late at night. In my opinion Bergdoll was the driving force in growing our business dealing with “Sweet Chuckie” buying the company, going public and eventually selling to Newell. We were all blessed with a combination of brilliant development of products from the lab combined with aggressive marketing and sales personnel.

I am an inkwell collector and just purchased a pottery Sanford 1 gallon ink bottle. Can you tell me what time period this was produced by the company?

I am Researching the History of a Wooden Box that says Sandford’s Ink Library Paste 23 also has 429 And Chicago New York and details on the history of this would ne greatly appreciated l!

Hola, tengo una antigua lapicera Stanford , es negra y con una faja dorada en el capuchón, pluma dorada y tiene un soporte para enganchar al bolsillo. Quisiera saber qué valor tiene. Muchas gracias

I have a nice collection of antique Sanford’s bottles and products. If you are interested in pictures please contact me.

I worked for Sanford Ink Co. in June 1980. It was an interesting job I had done running a Deglazeing Machine for Sharpie Marker pen barrels to be silk screen printed for production.The pen barrels came from a plastic molding company from Huntington,PA.The machine looked like a laundry mat dryer.I worked hard for the company.The Union ruined that shop in Bellwood,IL,Period.I got laid off after 30 days & the fools kept my Union initiation fee.A really worthless manufacturing job.Never again.Mr Sanford would be mad to see his employees treated like this.

Corrupt Unions have destroyed 100s of business’s and many 1,000s of jobs over the years.

I grew up in Bellwood, Il. As a kid I remember riding my bike on the way to Memorial Park we would check out the dumpster for any reject Sharpie markers. Markers that had bad tips were just thrown away.

The mass manufacturing method of the Sanford brand pens, Sharpie and Marks-A-Lot, were the brain child of a young engineer at Sanford, Ted Jensen. Jensen worked for Charles Lofgren prior to Pearsall joining the firm. As an aside, Jensen claimed that the original design of the Sharpie was drawn on a napkin by former Sanford salesman, Walter Lomach. History has lost these two stories, but the manufacturing design patents exist and can provide historical evidence of the Jensen connection to the production of the Sanford marking pens.

I found a Sandford’s bottle on the banks of the Buffalo river in Arkansas that I would like some identifying and maybe some insight into how rare it may be.

I have a beautiful Sanford Redington refillable rolling ball pen. The refill has dried out, and I don’t know how to find a refill that will fit it. Does Sanford/Newell/Uniball still make them? If so, how can I find them? If not, is there any other refill on the market that will fit it?

It is Chrome with gold accents, and says, “Sanford Redington JAPAN” on it.

thank you for any help that you can give to me