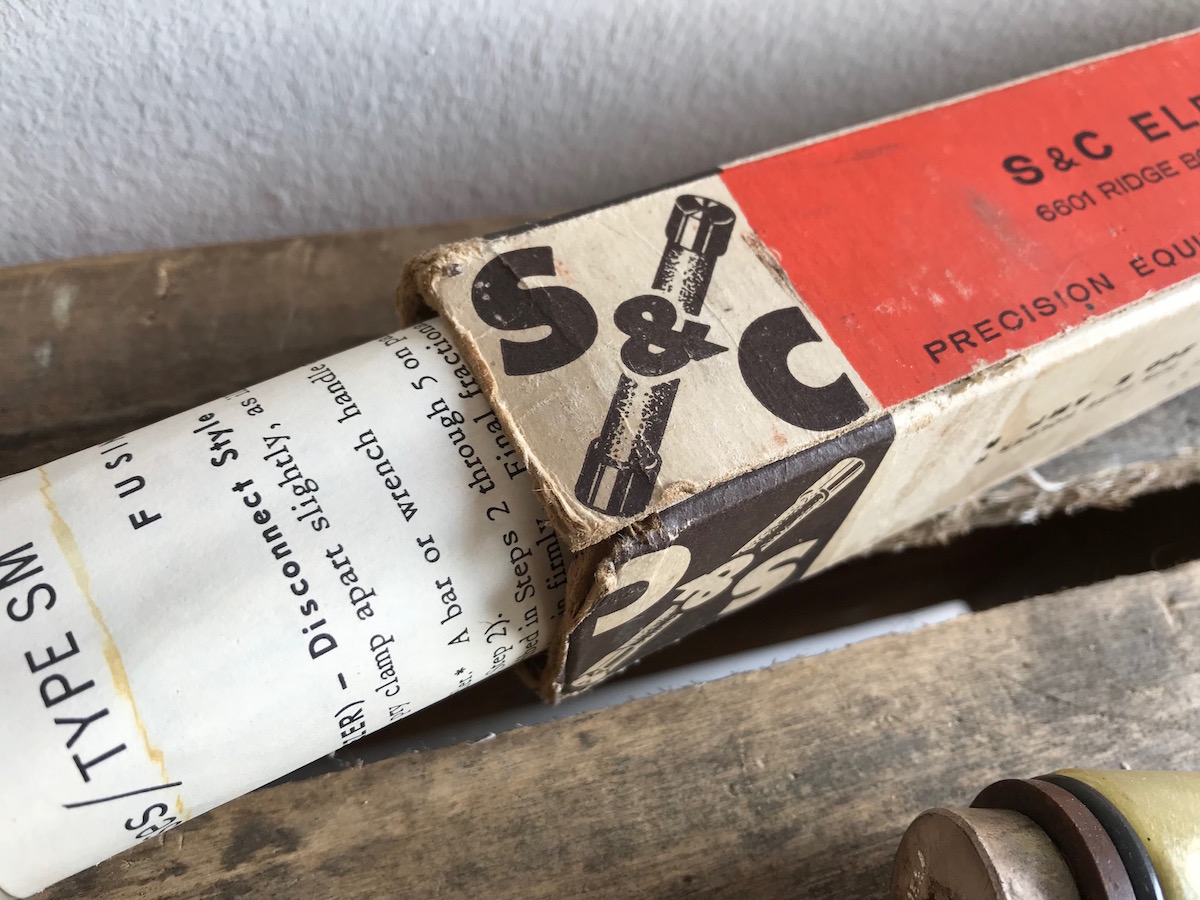

Museum Artifact: SM-4 Power Fuse Refill Unit, 1960s

Made By: S&C Electric Co., 6601 N. Ridge Blvd., Chicago, IL [Rogers Park]

In 2012, shortly after Chicago’s S&C Electric Company marked its 100th anniversary, the IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers) awarded the business special recognition for one of the “milestone” achievements in electrical engineering history—the 1909 invention of the liquid power fuse. During a special dedication ceremony at S&C’s Rogers Park headquarters, former IEEE president Dr. Moshe Kan hailed the original S&C Fuse as a “marvel that still impresses today,” but also acknowledged that the genius of its design probably would never resonate with the average Joe.

“What makes this invention different than milestones by Tesla, Marconi, Edison, and Popov,” Kam said, “is that, try as we might, this is truly a landmark for us engineers; a breakthrough that, in all likelihood, we will not be able to share widely with the public. . . Schweitzer and Conrad [the S & C in S&C], who worked on a problem of great significance to public welfare, and whose inventions have enabled the safe and inexpensive supply of electricity for millions, are probably destined to be remembered only by us; the relatively few who are closer to their field of interest and who can appreciate fully the ingenuity and importance of their life’s work.”

“What makes this invention different than milestones by Tesla, Marconi, Edison, and Popov,” Kam said, “is that, try as we might, this is truly a landmark for us engineers; a breakthrough that, in all likelihood, we will not be able to share widely with the public. . . Schweitzer and Conrad [the S & C in S&C], who worked on a problem of great significance to public welfare, and whose inventions have enabled the safe and inexpensive supply of electricity for millions, are probably destined to be remembered only by us; the relatively few who are closer to their field of interest and who can appreciate fully the ingenuity and importance of their life’s work.”

Sure, it sounds a little condescending to suggest that we—the tiny-brained masses—could never appreciate the work of two men who helped bring us the modern electrical power grids we all rely on for, well, everything. But, if we’re being honest, Dr. Kan ain’t wrong. An object like the tubular SM-4 Power Fuse Refill Unit in our museum collection is never going to inspire the same fascination or warm nostalgia as an Edison light bulb or a vintage radio. While a power fuse is an “everyday object” in many respects, it’s not something we regularly have to handle or think about, and it certainly doesn’t have a rabid collector’s market. As such, public interest in the history of these objects and the people who created them is limited at best, much like our understanding of what the county lineman is actually doing up in that cherrypicker.

For this reason, when the business once known as Schweitzer & Conrad Inc. officially became S&C Electric in the 1940s, it also may have inadvertently erased any hope of sustaining the legacy of its founders in the mainstream consciousness.

On the bright side, though, the company they created has survived and thrived beyond anyone’s wildest expectations—defying the usual life cycle of its 20th century peers to remain a uniquely independent and relevant tech manufacturer here in the 21st.

Family owned for decades, S&C is now the property of its own employees, and rather than fleeing for the suburbs or selling out to the competition, it has only continued to expand its 47-acre Chicago campus—a headquarters first opened just after World War II, and now employing close to 2,000 local workers.

History of S&C Electric Company – Part I: Mr. S. and Mr. C.

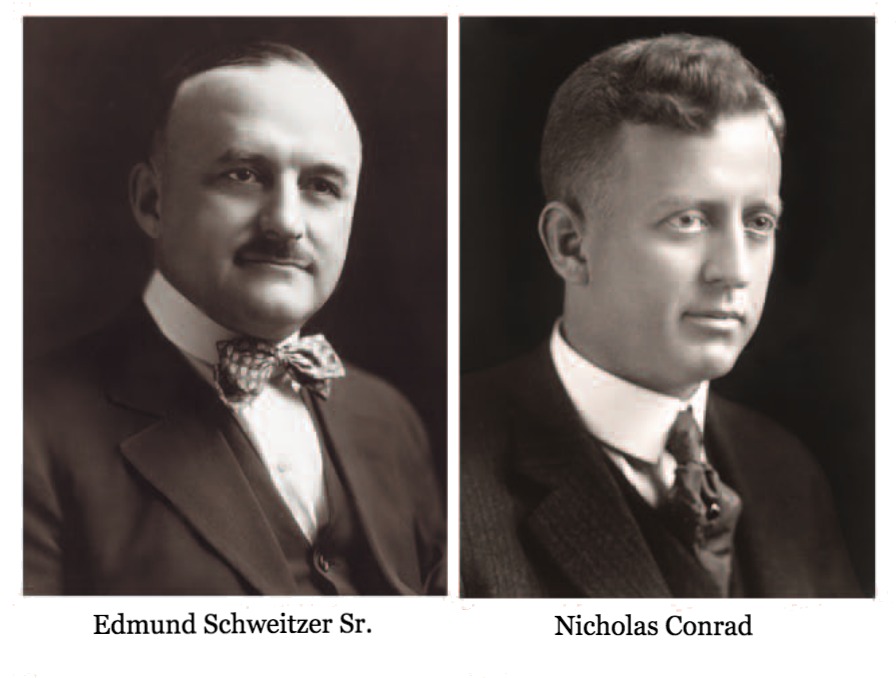

Edmund O. Schweitzer (1875-1949) and Nicholas J. Conrad (1883-1956) grew up at the dawning of the electrical age; a pair of Midwestern kids who wisely angled their career paths in the direction of that revolution. They collected electrical engineering degrees from Purdue University and the University of Wisconsin, respectively, and by 1907, both fellas were vital minds at the new Commonwealth Edison Company, formed from a merger of Commonwealth Electric and the Chicago Edison Company. Schweitzer was the Chief Testing Engineer for ComEd, while Conrad was the Generator Starting Engineer.

Edmund O. Schweitzer (1875-1949) and Nicholas J. Conrad (1883-1956) grew up at the dawning of the electrical age; a pair of Midwestern kids who wisely angled their career paths in the direction of that revolution. They collected electrical engineering degrees from Purdue University and the University of Wisconsin, respectively, and by 1907, both fellas were vital minds at the new Commonwealth Edison Company, formed from a merger of Commonwealth Electric and the Chicago Edison Company. Schweitzer was the Chief Testing Engineer for ComEd, while Conrad was the Generator Starting Engineer.

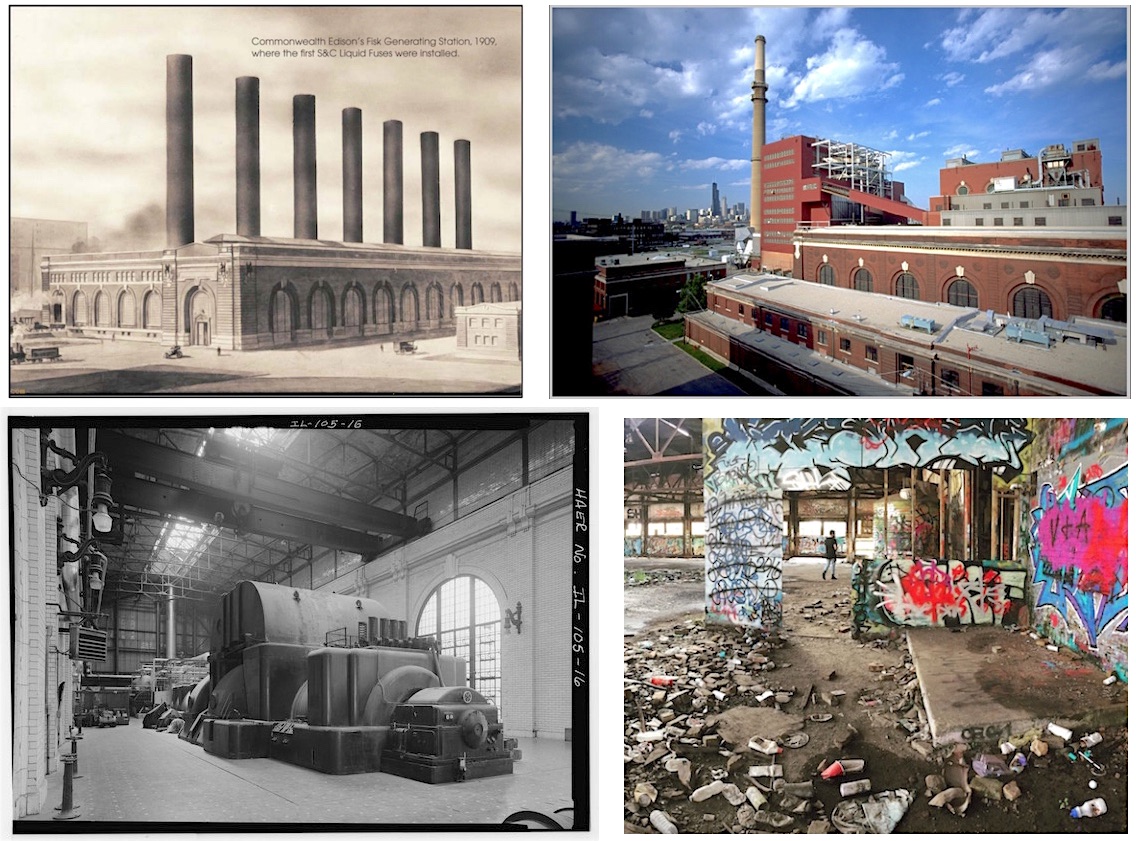

One of the first projects Mr. S. and Mr. C. worked on together was the ongoing construction of the Fisk Street Generating Station in Pilsen, which would go into operation as the “pioneer steam turbine power house of this country” (Electrical World, 1909) and “the largest electric light and power station in the world” (Technical World, 1906). According to S&C lore, a disastrous fire at Fisk Station in 1909 was actually the impetus for Schweitzer and Conrad to start investigating a better, safer fuse design. Weirdly, though, I could find no reference to any such fire in news archives from that year.

[Then & Now of Chicago’s Fisk Generating Station, which was shut down and abandoned in 2012]

[Then & Now of Chicago’s Fisk Generating Station, which was shut down and abandoned in 2012]

In any case, the big wigs at ComEd were certainly aware that there were vulnerabilities in their rapidly evolving power systems, as short circuits too routinely led to leaks, blasts and other various mishaps. Early power fuses couldn’t be relied on to safely “interrupt” short circuits, so, Schweitzer and Conrad were tasked with finding a long-term solution.

What they came up with was the first high-voltage liquid power fuse, the S&C High Potential Fuse: “a spring-loaded fuse inside a high-temperature glass tube filled with a fire-extinguishing liquid, carbon tetrachloride,” according to a historical account in the June 2016 issue of IEEE Industry Applications Magazine. It was a simple but ingenious tweak that proved to be every power station’s new troubleshooting silver bullet.

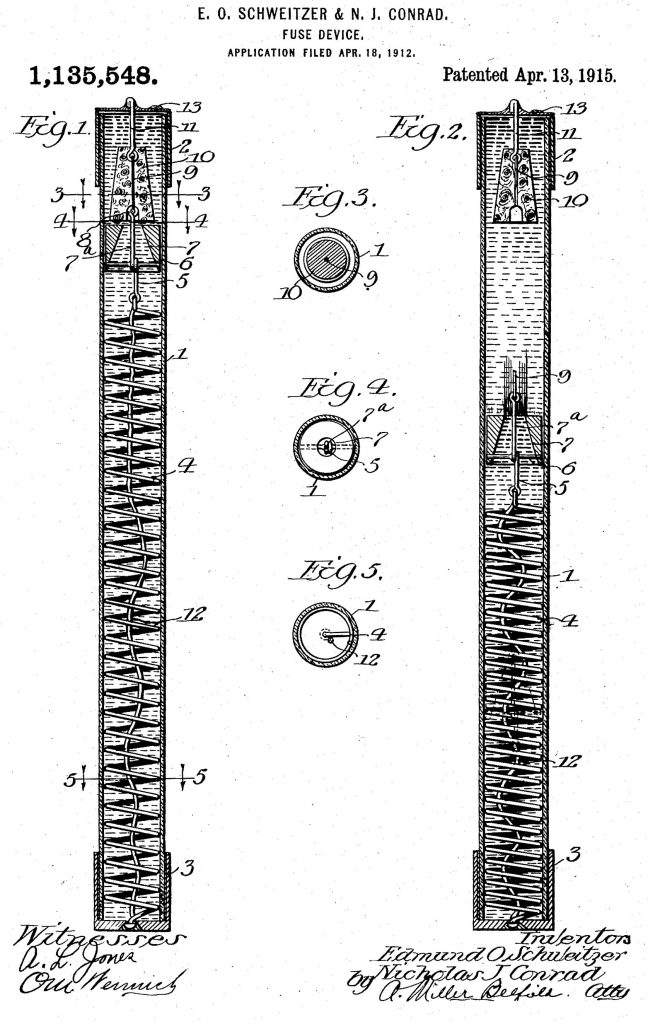

While the design was worked out in 1909, production didn’t start until 1911, with Conrad literally making the early prototypes on his own workbench and selling them one-by-one to ComEd for $1.25 a piece. This was the beginning of Schweitzer & Conrad, Inc., organized in 1911 behind just $1,000 in borrowed money. The business was something of a lark at first. Both Mr. S. & Mr. C. kept their day jobs with ComEd, and their side project occupied just a few rented rooms in a building at the corner of Wilson Ave. and Ravenswood Ave., with one full-time employee (an assembler named Ed Toman) on staff that first year. The S&C Fuse patent [pictured] wasn’t even approved until 1915, and yet, everyone in the industry seemed to be keenly aware of it long beforehand.

While the design was worked out in 1909, production didn’t start until 1911, with Conrad literally making the early prototypes on his own workbench and selling them one-by-one to ComEd for $1.25 a piece. This was the beginning of Schweitzer & Conrad, Inc., organized in 1911 behind just $1,000 in borrowed money. The business was something of a lark at first. Both Mr. S. & Mr. C. kept their day jobs with ComEd, and their side project occupied just a few rented rooms in a building at the corner of Wilson Ave. and Ravenswood Ave., with one full-time employee (an assembler named Ed Toman) on staff that first year. The S&C Fuse patent [pictured] wasn’t even approved until 1915, and yet, everyone in the industry seemed to be keenly aware of it long beforehand.

“The faults common to all of the ordinary types of fuses have been very successfully overcome in this new type of S&C fuse,” Electrical Review reported in 1912. “Numerous tests have been made, subjecting the fuse to severe conditions of short-circuit, and the results obtained were so remarkable that prominent engineers, both from this country and abroad, have expressed themselves most favorably regarding the results of the tests and the future possibilities of the fuse.”

As demand for the new fuse continued to grow, Nicholas Conrad made the bold decision to leave ComEd and devote himself to running Schweitzer & Conrad, which opened a new exclusive factory at 4435 N. Ravenswood Ave. in 1917. Edmund Schweitzer, perhaps looking at the risks of going independent in wartime, elected to stay at ComEd, and would remain just a silent partner in S&C for the duration of his involvement.

[The first main S&C Electric plant was in this building at 4437 N. Ravenswood Ave.]

[The first main S&C Electric plant was in this building at 4437 N. Ravenswood Ave.]

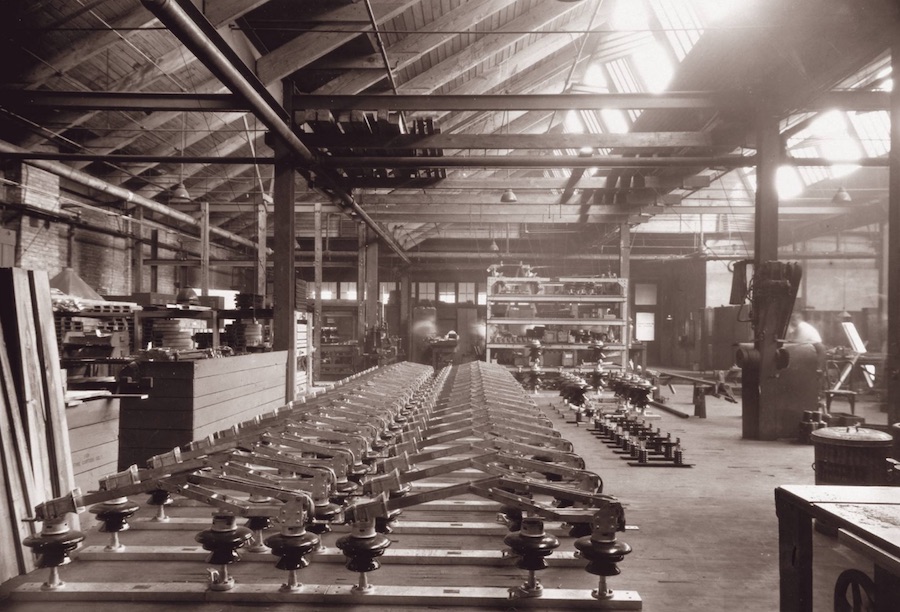

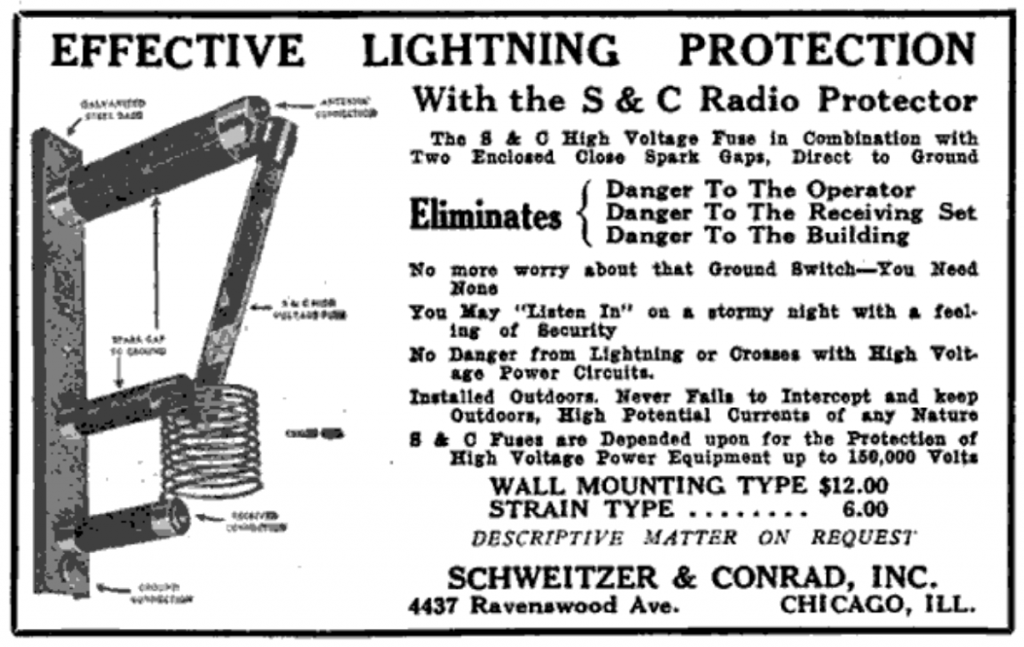

For a while, fortune certainly favored the bold. Conrad turned the profits from the S&C fuse into major investments for his startup company—particularly in the arena of research. Along with a series of updated fuse patents (Conrad collected close to 50 in his career), the company introduced other cool-sounding instruments of great interest to forward thinking industrialists: choke coils, lightning arresters (bad-ass!) and a Pantograph switch for high voltage transmission lines.

By 1925, the Ravenswood factory employed 110 workers, many of them skilled European craftsmen who’d settled in the Ravenswood area. A high percentage were immigrants from Luxembourg, the same country Conrad’s own family had come from.

[Pantograph switch production at the Ravenswood plant, c. 1925, courtesy of S&C Facebook page]

[Pantograph switch production at the Ravenswood plant, c. 1925, courtesy of S&C Facebook page]

II. The “Lost Years”

It was remarkable enough that Schweitzer & Conrad had managed to compete with giants like General Electric and Westinghouse throughout the 1920s, but the company’s unlikely second chapter was probably doubly as impressive.

Following the stock market crash in 1929, the business hit an understandable slowdown, which was greatly exacerbated by a lingering illness that was hindering Nicholas Conrad’s ability to work. Sensing impending doom as the Depression set in, both Conrad and Schweitzer elected to sell their business to a Milwaukee-based radio parts manufacturer called Cutler-Hammer. It was 1930, and the S&C story appeared to have reached a sudden and disappointing end.

For the next 15 years, Schweitzer focused on his work with ComEd, while Conrad concentrated on regaining his health. Surprisingly, though, their old business carried on under Cutler-Hammer’s ownership, retaining the S&C name, the Ravenswood plant, and the vast majority of its original staff. This included Conrad’s former apprentice Sigurd Lindell, who co-created the “load-interrupter switch” in the late ‘30s—one of more than 100 patents collected by the company during what was supposed to be the slog of the Depression. It was a weird “transitional” phase in many respects, and not a hugely profitable one. And yet, to Cutler-Hammer’s credit, the original S&C vision was maintained year by year, straight on through World War II, when military contracts helped keep the factory in operation.

Finally, in 1945, with a now 63 year-old Nicholas Conrad feeling suddenly rejuvenated with post-war optimism, the C made a surprise return to S&C. Conrad re-purchased the business from Cutler-Hammer and bought out the remaining stock of an aging Schweitzer, as well. It was a triumphant comeback story of sorts, but it really hinged on Conrad enticing a certain new business partner to join him in a leadership role: his own son, John R. Conrad.

[Left: Nicholas Conrad and his son John in Atlantic City, 1927. Center: Tribune story on the new S&C plant in Rogers Park, 1949. Right: John and Nicholas Conrad breaking ground on part of that new facility, 1949.]

[Left: Nicholas Conrad and his son John in Atlantic City, 1927. Center: Tribune story on the new S&C plant in Rogers Park, 1949. Right: John and Nicholas Conrad breaking ground on part of that new facility, 1949.]

III. The Next Generation

John Conrad (1915-2005) had grown up in Ravenswood, but was still in high school when his father sold the family business to Cutler-Hammer. From there, young Johnny went on to earn his degree from the University of Chicago, studying economics rather than engineering—perhaps sensing that his success might depend more on running a business than launching one (by contrast, both Edmund Schweitzer Jr. and Edmund Schweitzer III followed in the family tradition and became celebrated electrical engineers for other companies).

After college, John got his first major job as a properties manager with Douglas Aircraft in Long Beach, California, where he proudly helped build planes for the war effort.

After college, John got his first major job as a properties manager with Douglas Aircraft in Long Beach, California, where he proudly helped build planes for the war effort.

When Nicholas Conrad re-acquired Schweitzer & Conrad Inc. after the war, however, a now 30 year-old John couldn’t turn down the chance to come home to Chicago and help his dad awaken what they both saw as a sleeping giant—and an important part of their family legacy.

Within a year, father and son sought out real estate for a new manufacturing plant, just a bit further north of Ravenswood in Rogers Park.

“Nicholas J. Conrad, president of the S&C Electric company, said recently that his firm selected a site at 6600 Ridge Ave. for erection of a 2 million dollar modern manufacturing plant and office,” the Tribune reported in 1949. “The location is in and near good residential neighborhoods and it will permit workers to find good homes within walking distance of their work. ‘It also provides the company with a nearby source of high grade workers,’ Conrad said.”

[“Unit One” construction site of new S&C plant at 6601 N. Ridge Blvd., late 1940s]

[“Unit One” construction site of new S&C plant at 6601 N. Ridge Blvd., late 1940s]

By 1952, Nicholas had officially handed the reins of the business to John, who at age 37, was now devoted to building the rapidly expanding Ridge Avenue plant and its surroundings into a miniature factory-town utopia.

Soaring profits had helped the S&C workforce grow to more than 400, and according to the 2010 S&C booklet A Century of Innovation, John Conrad was a popular president, providing his employees with “above-average pay and benefits, a comfortable factory, and a social environment that included bowling leagues, family picnics, and Christmas parties. In return, he asked for complete loyalty, attention to detail, and a very high standard of quality and cleanliness. Overtime was added to the income of factory employees when business was good, and helped avoid layoffs when demand slowed. His formula worked. Many employees stayed at S&C for their entire careers.”

They never unionized either—a rarity by this era.

[Workers and their families at the S&C company picnic, 1946]

[Workers and their families at the S&C company picnic, 1946]

Even amid all the peaceful post-war productivity, however, obstacles were aplenty. Nicholas Conrad died in 1956, leaving John on his own to navigate a landscape that many felt was far too competitive for a private business to survive. Success after the war had led to increasingly devastating tax rates as high as 70%, something John bemoaned in a 1952 Tribune article as a limiting factor in updating the company’s machinery. In that same story, he said that the bulk of S&C’s 3% profits went right back into maintaining its 42-person research staff.

“To S&C, research is vital,” the Tribune noted. “Without it the small company simply could not compete with its larger rivals.”

As a major credit to John Conrad’s business ethics, S&C seemed to turn its disadvantages into points of pride over the years ahead. In the late 1950s, when the U.S. government cracked down on 29 electric equipment suppliers for price fixing, S&C was notably NOT among those indicted. Similarly, as bigger companies floated offers to acquire S&C’s reputable line of products, Conrad brushed them off with attitude. “I’m not about to let S&C become the trinket of some big empire,” he supposedly said.

As a major credit to John Conrad’s business ethics, S&C seemed to turn its disadvantages into points of pride over the years ahead. In the late 1950s, when the U.S. government cracked down on 29 electric equipment suppliers for price fixing, S&C was notably NOT among those indicted. Similarly, as bigger companies floated offers to acquire S&C’s reputable line of products, Conrad brushed them off with attitude. “I’m not about to let S&C become the trinket of some big empire,” he supposedly said.

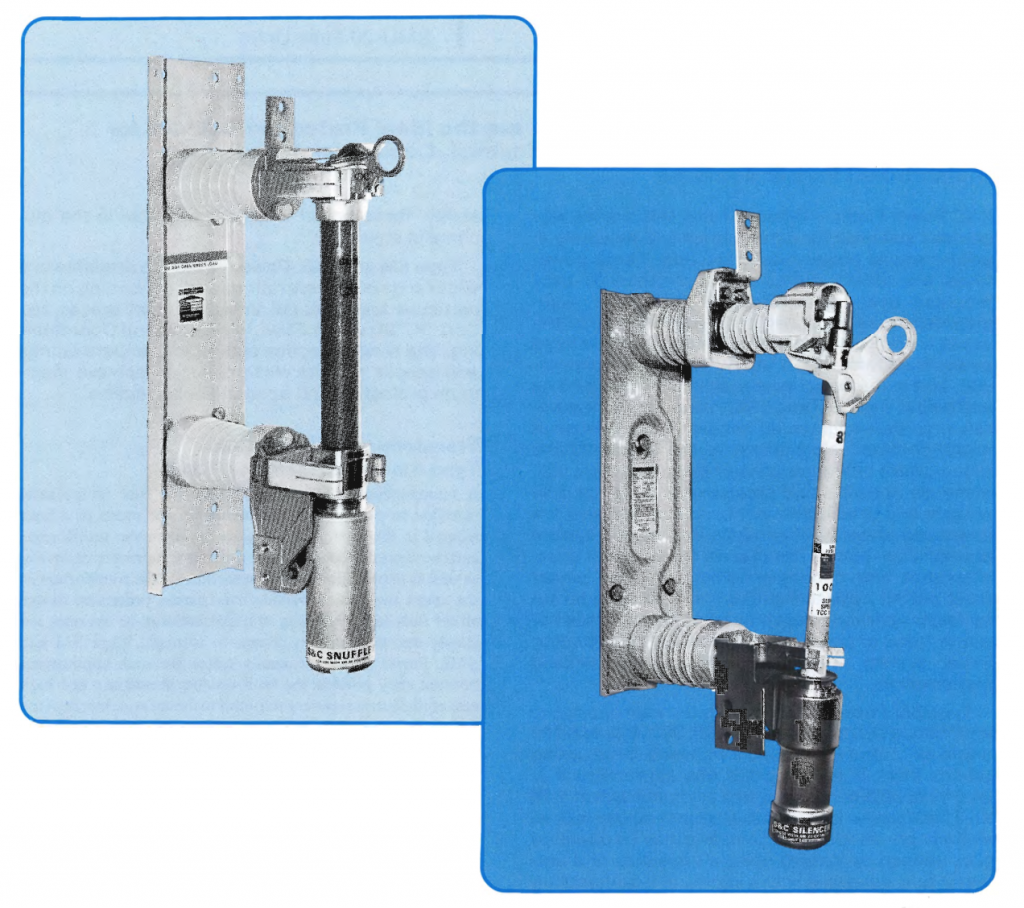

S&C expanded into Canada in 1953, and they rolled out a number of major new innovations before the decade ended, including the Type XS Cutout [pictured in the factory image above], the Loadbuster interrupter, and Circuit-Switcher—all soon trusted tools of the lineman’s trade . . . if not, perhaps, household names.

Conrad honored his late father with the creation of the Nicholas J. Conrad Laboratory in 1959. The $2 million addition to the Rogers Park campus was the first large building in Chicago to be heated electrically, and it made three bold statements about the state of S&C as a company: it was staying independent, it was staying local, and it was pushing forward in innovation.

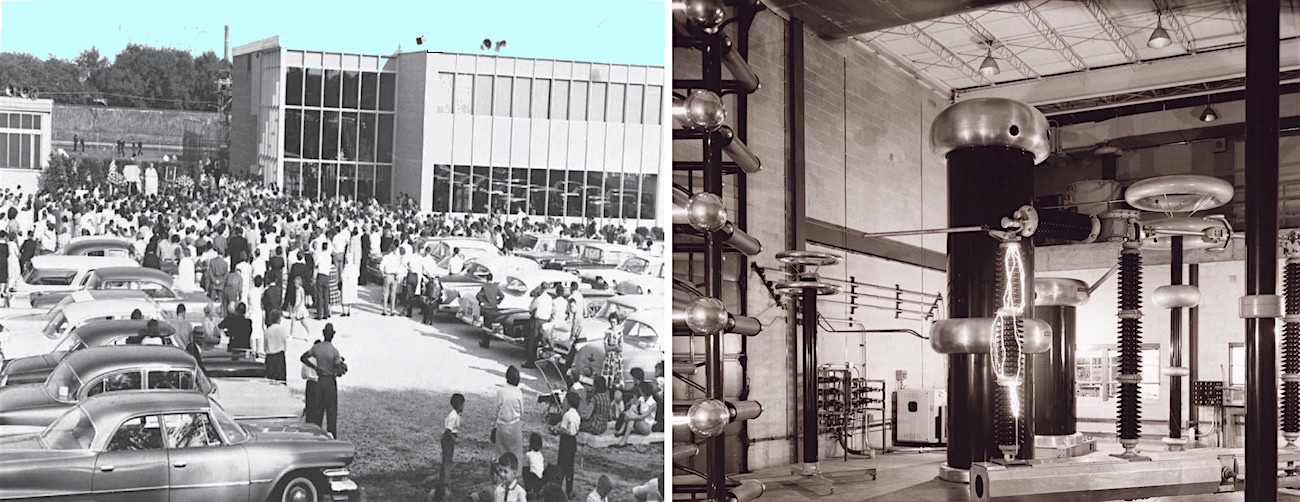

[Left: Grand opening of the Nicholas J. Conrad Laboratory at S&C’s Rogers Park complex, part of the company’s 50th anniversary in 1961. Right: Inside the NJC lab, where products could now be tested at voltages from 2,500 to 1.6 million volts (courtesy of S&C Facebook page)]

[Left: Grand opening of the Nicholas J. Conrad Laboratory at S&C’s Rogers Park complex, part of the company’s 50th anniversary in 1961. Right: Inside the NJC lab, where products could now be tested at voltages from 2,500 to 1.6 million volts (courtesy of S&C Facebook page)]

IV. The Artifact

It was around this time, in the early 1960s, that the vintage S&C artifact in our museum collection—the SM-4 Refill Unit—was made. While it was sold more than 50 years after S&C’s original liquid power fuse, it could be considered a recognizable descendent, I suppose.

S&C made these SM units for decades, and a user’s manual from a later 1983 edition helps explain their construction in language far more useful than any hopeless attempt at layman’s terms I could muster.

S&C made these SM units for decades, and a user’s manual from a later 1983 edition helps explain their construction in language far more useful than any hopeless attempt at layman’s terms I could muster.

“The refill unit consists of a fusible element, arcing rods, and a solid-material arc-extinguishing medium contained within a filament-wound glass-epoxy tube.

The fusible element is connected at one end—through a current-transfer bridge—to the refill unit lower ferrule. At the other end, the fusible element is connected to the main arcing rod, which extends upward through the main bore of the refill unit to the upper terminal. The auxiliary arcing rod, of stainless steel, is threaded into the upper terminal and extends downward through a small-diameter stepped bore and through an opening in the current-transfer bridge. No load current is carried by this auxiliary rod since, at its small-diameter section, it is insulated from the auxiliary arcing contact.”

Make sense? Yeah, well, as we’ve established, this stuff ain’t for everybody.

That same 1983 manual summarized the general function of SM fuses and how they could be utilized:

“S&C Power Fuses—Types SM and SML are the ideal protective devices for transformers and cables on utility, industrial, commercial and institutional power systems. . . . They are widely applied for transformer protection because of their inherent simplicity, reliability, economy, fast response characteristics, and freedom from maintenance. These characteristics make Type SM and SML Power Fuses preferable to circuit breakers in most transformer-protection applications.”

Our earlier 1963 model of the SM-4 still has its original instructions in the box, complete with these helpful visual aids on “FUSING: Without Muffler or Sneezer”:

Step 1: Remove the hexagonal clamping nut.

Step 1: Remove the hexagonal clamping nut.

Step 2: Unscrew and withdraw holder cap, to which is attached the spring-and-cable assembly.

Step 3: Screw refill unit tightly onto spring-and-cable assembly.

Step 4: Insert this combination into the holder and screw the cap down tight.

Step 5: Carefully draw the pull-up cord outward from holder until knurled collar shoulder is approx. 1/8″ beyond spring fingers on end of holder, then release pull-up cord slowly, permitting collar to seat on fingers. Remove and discard the cord.

Step 6: Replace hexagonal clamping nut, screwing down firmly to lock refill unit into place.

Aesthetically, the SM-4 tube certainly isn’t much to look at, but in action, it represented S&C quality at its finest—American ingenuity and design still keeping the lights on in the late 20th century.

V. The Pride of Rogers Park

S&C’s employee count topped the 1,000 mark in the 1960s, and the Ridge Blvd. plant continued to develop through the ‘70s, even as rising electricity costs and increased foreign competition posed new challenges.

Now approaching retirement age himself, John Conrad started a more aggressive recruitment effort to bring in the best young engineering minds from leading universities—the tops of the Baby Boomer lot. He called these new hires the “Young Turks,” and one of them—a kid out of Canada’s Queen’s University named John W. Estey—soon emerged as the blue chip prospect. By 1977, Estey was Vice President of the company, and by 1988, Conrad had installed him as the new president.

Now approaching retirement age himself, John Conrad started a more aggressive recruitment effort to bring in the best young engineering minds from leading universities—the tops of the Baby Boomer lot. He called these new hires the “Young Turks,” and one of them—a kid out of Canada’s Queen’s University named John W. Estey—soon emerged as the blue chip prospect. By 1977, Estey was Vice President of the company, and by 1988, Conrad had installed him as the new president.

As much as things changed, though, some things at S&C remained non-negotiable—tops among them, was the company headquarters.

“Relocating is no longer an option for us,” a 72 year-old John Conrad told the Tribune in 1987. “We’ve made a decision to stay put.

“From our standpoint, our workforce has been key to out strength,” he continued, noting that S&C had always had a strong loyal relationship with its surrounding community, dating back to those early Luxembourgers that worked for Schweitzer & Conrad. “We learned early how to get along with our neighbors. We put waste control measures in before the requirements became as strict as they are. Most manufacturing facilities aren’t thought to be good neighbors, but I think we’ve help up our end of the deal.”

[The S&C campus in Rogers Park has gradually expanded to 47 acres, with much of the actual complex underground and somewhat unnoticed by the locals]

[The S&C campus in Rogers Park has gradually expanded to 47 acres, with much of the actual complex underground and somewhat unnoticed by the locals]

S&C’s benefit services manager, Diane Taylor, went into greater detail about Rogers Park and S&C’s unique marriage in that same 1987 article.

“I don’t know of many companies that can claim to have employees who live and work in the same area,” Taylor said, “but it’s something we try to keep track of because we’re interested in what it means to keep a manufacturing company in the city.”

Notably, S&C’s staff continued to reflect its neighborhood, even as the demographics in Rogers Park dramatically changed. “Our workforce is 59 percent white and 41 percent minority, including blacks and Hispanics,” Taylor said in ‘87. “It’s similar to the mix of the area where we’re located. Our commitment here didn’t change when our employee mix changed. Rogers Park is a healthy community, and we’d like to think that companies like ours help in its stability.”

VI. Power to the People

Thirty year later, S&C remains the largest manufacturing employee in Rogers Park—largely thanks to John Conrad’s stubborn commitment to that old factory-town ideal. “We’re a little guy compared to Westinghouse or GE,” he once said, “but we’ve grown by expanding our market. Our products are sold in South America, Korea, Taiwan, Australia, the Philippines, and some Middle East countries. . . . We’re privately held, and we don’t have to bother with Wall Street’s grumblings about this or that. We’re accountable to ourselves and the community where we live.”

Thirty year later, S&C remains the largest manufacturing employee in Rogers Park—largely thanks to John Conrad’s stubborn commitment to that old factory-town ideal. “We’re a little guy compared to Westinghouse or GE,” he once said, “but we’ve grown by expanding our market. Our products are sold in South America, Korea, Taiwan, Australia, the Philippines, and some Middle East countries. . . . We’re privately held, and we don’t have to bother with Wall Street’s grumblings about this or that. We’re accountable to ourselves and the community where we live.”

That accountability took on a whole new dynamic after John Conrad’s death in 2005. Since he had refused to sell the business to outsiders, and his three daughters had no interest in keeping their stock, Conrad’s company eventually came under the majority control of an employee stock ownership program (ESOP), meaning S&C’s 2,500 workers worldwide are also now their own bosses . . . sort of.

As president and CEO, John Estey [pictured] was certainly still the guy everyone looked to. Originally hired in 1972, Estey was a part of S&C for almost as long as Nicholas and John Conrad were, and before his 2015 retirement, he made a comparable impact, too, revamping manufacturing in the ‘90s and helping to roll out a new arsenal of gold standard innovations: the Scada-Mate Switching System, Fault Tamer Fuse Limiter, Vista Switchgear, and the Trans-Rupter II Transformer Protector, among others.

As president and CEO, John Estey [pictured] was certainly still the guy everyone looked to. Originally hired in 1972, Estey was a part of S&C for almost as long as Nicholas and John Conrad were, and before his 2015 retirement, he made a comparable impact, too, revamping manufacturing in the ‘90s and helping to roll out a new arsenal of gold standard innovations: the Scada-Mate Switching System, Fault Tamer Fuse Limiter, Vista Switchgear, and the Trans-Rupter II Transformer Protector, among others.

S&C also gained ground in the digital revolution, buying two electronics tech companies (EnergyLine and Omnion) in the late ‘90s, and breaking new ground with devices and software that could create “smart” self-healing circuits.

Under current president Kyle Seymour, S&C remains a respected force in electricity delivery, and as of now, it’s still committed to both its employee ownership structure and its home base of Chicago. They’ll never be regional icons like Wrigley or Motorola, but S&C certainly deserves a little love from outside the inner circle of electrical engineers. On behalf of all the people who don’t understand magic lightning tubes but still think they’re cool, we salute you!

[S&C at an IEEE convention, 1974, courtesy of S&C Facebook page]

[S&C at an IEEE convention, 1974, courtesy of S&C Facebook page]

SOURCES

“Liquid Fuse to Smart Grid: A Century of Innovation” – S&C Electric Co., 2010

“Twin Synchronous Machines for Short Circuit Testing” by Barry C. Brusso, IEEE Industry Applications Magazine, May/June 2016

“S&C Electric Company Appoints Kyle Seymour as New President” – PR Newswire, Jan 8, 2013

“S&C Power Fuses Types SM and SML” – S&C Descriptive Bulletin, March 21, 1983

“John R. Conrad: 1915-2005” – Chicago Tribune, Sept 5, 2005

“Milestones: World’s First Reliable High Voltage Power Fuse, 1909” – Engineering and Technology History Wiki

“IEEE Milestone Dedication Held at S&C Electric Company” – IEEE Chicago Section

“S&C Electric Good Neighbor for 76 Years” – Chicago Tribune, May 26, 1987

“Recent Developments in the Art of Circuit-Interrupting Devices for High Voltages” – Electrical Review & Western Electrician, July 27, 1912

“The S&C Automatic Switching Units” – Electrical Review & Western Electrician, May 12, 1917

“S&C Electric Company History” – FundingUniverse.com

“Comments During the Dedication of an IEEE Milestone on the World’s First Reliable High Voltage Power Fuse, 1909 (3 August 2012, Chicago, IL, USA)” – MosheKam.org

“S&C Electric’s Unusual Succession Path” – Crain’s Chicago Business, May 12, 2012

“Chicago Company Builds Out, and Shows Off, Smart Grid and Energy Storage” – U.S. Energy News, Nov 8, 2016

“All Hail S&C Electric Company!” – Diane Taylor, Living-Las-Vegas.com, Oct 2, 2011

“Plan 2 Million Dollar Plant for Ridge Ave” – Chicago Tribune, Oct 27, 1949

“Taxes Cripple Small Firms’ Development” – Chicago Tribune, September 18, 1952

Nicholas J. Conrad obit – Chicago Tribune, Sept 19, 1956

In 1995 I designed 20 graphic panels about the history of S&C for the 75th Anniversary of the company. Some of the text and photos in this article were used on the graphics. It was an interesting project. I met John Conrad and John Estey.

Thanks for creating this page about S&C. I live in Evanston and pass it by it every time I bike to work in Chicago. It’s unusual in that it’s such a large manufacturing campus but surrounded by homes. I’ve long wondered what goes on there. How nice to find out that they are a good corporate neighbor.

Can you give me any information on a very old tool I’ve found and it has your data plate on it? It’s a very interesting find.