Museum Artifact: Roy Smeck Soprano Ukulele, c. 1950s

Made By: The Harmony Company, 3633 S. Racine Ave., Chicago, IL [Bridgeport]

For about 80 years, Chicago’s Harmony Company consistently ranked among the largest producers of stringed instruments in the world. Unfortunately, when we’re talking about “the arts,” such a legacy of quantity can often presume a deficiency in quality—warranted or not.

Sure, Harmony was always the unashamed brand of the common man, and their affordably priced products were churned out en masse and sold predominantly through the pages of mail order catalogs. But to reduce the company’s output down to the single adjective of “cheap”—or to equate them to the auto-machined Asian imports of the modern day—would be hitting a mighty discordant note.

Sure, Harmony was always the unashamed brand of the common man, and their affordably priced products were churned out en masse and sold predominantly through the pages of mail order catalogs. But to reduce the company’s output down to the single adjective of “cheap”—or to equate them to the auto-machined Asian imports of the modern day—would be hitting a mighty discordant note.

In reality, it was Harmony’s stubborn dedication to genuine craftsmanship that eventually got them overrun by foreign competition in the 1970s. Up through its final years, the company was still touting: “We’ve produced millions of instruments, but we make them one at a time,” and it wasn’t just a slogan. The technology for using pre-set automation to clone guitars and other fretted instruments had existed since at least the 1940s, but Harmony president Jay Kraus—who led the firm for the better part of 50 years—firmly believed that even a low-cost beginner’s instrument deserved a closer attention to detail.

As a result, many budget-priced Harmonies became the unlikely tools of the trade for some of the biggest names in popular music—from blues legends like Howlin’ Wolf (Sovereign Flat-Top acoustic) to rock gods like Keith Richards (Meteor electric) and Jimmy Page (Sovereign H1260 acoustic). In more recent years, noted garage rockers Jack White (Rocket electric) and Dan Auerbach (H78 and StratoTone) have championed vintage Harmony axes, as well, drawing a new audience to the long defunct brand.

[Dan Auerbach of the Black Keys playing a vintage Harmony guitar]

[Dan Auerbach of the Black Keys playing a vintage Harmony guitar]

Even a less “rockin” Harmony artifact— like the 1950s Roy Smeck ukulele in our museum collection—can age quite gracefully into its golden years. We’re not going to compare it to a Stradivarius or anything, but hey, it’s no cookie cutter, either. A whole team of dedicated employees helped bring this little mahogany uke to life at Harmony’s old Racine Avenue plant in Bridgeport, and they did so with pride—even if they knew it would end up selling to some snot-nosed kid for 10 bucks.

“Perhaps the greatest note of pride about the company,” according to a 1952 article in the Central Manufacturing District Magazine, “may be struck in the fact that modern production methods have been applied to an age-old product while retaining the artistic touch of the master craftsman. More than half of Harmony’s nearly 150 employees, including the many women, are skilled workers. Some are so skilled that not even the top feats of engineering have been able to approach their touch. Harmony officials say that some of its jobs will never be replaced by machinery.”

And they weren’t, but the machines won anyway.

[Photo of Harmony Company factory workers, c. 1904 – (C) Westheimer Corp.]

[Photo of Harmony Company factory workers, c. 1904 – (C) Westheimer Corp.]

The Origin Story

According to a popular software algorithm that translates the handwriting from old U.S. census records, Harmony’s founder and first president, William J. F. Schultz, was employed in 1910 as a proprietor of “municipal dusters.” While that sounds extremely fascinating in its own right, I must regretfully correct the robot and report that Schultz was, instead, still selling “musical instruments” at the time.

Schultz was born in Hamburg (as “Wilhelm,” of course) in 1857, and—with his new bride Minnie—joined the wave of German immigration to Chicago in 1882. Back in the motherland, Schultz had honed his mechanical craft as a builder of cabinets and staircases. His greater passion, though, had always been music, and his own talent was serviceable enough to earn him a spot in Hamburg’s leading singing society of the time. He would happily keep that side hustle going in his new home, joining the United Singing Society of Chicago, but the bigger goal was to somehow “live the dream” and make music a part of his working life.

He had come to the right place. Within months of his revival in Chicago, Schultz nabbed a job with the Knapp Drum Company, which was soon bought out by one of the city’s preeminent musical instrument manufacturers and dealers, Lyon & Healy. From 1884 to 1891, William Schultz learned the ropes from the masters of American mass-production, spending most of those years as a foreman for L&H. He helped design and manufacture drums and tambourines out of the old Knapp plant, and eventually added banjos to the arsenal. Despite the considerable size of Lyon & Healy’s operation, demand for stringed instruments, in particular, always seemed to outpace the supply. Schultz sniffed out an opportunity.

He had come to the right place. Within months of his revival in Chicago, Schultz nabbed a job with the Knapp Drum Company, which was soon bought out by one of the city’s preeminent musical instrument manufacturers and dealers, Lyon & Healy. From 1884 to 1891, William Schultz learned the ropes from the masters of American mass-production, spending most of those years as a foreman for L&H. He helped design and manufacture drums and tambourines out of the old Knapp plant, and eventually added banjos to the arsenal. Despite the considerable size of Lyon & Healy’s operation, demand for stringed instruments, in particular, always seemed to outpace the supply. Schultz sniffed out an opportunity.

By the age of 35, it was time to fly the coop. Combining forces with an all German team that included Charles Richter (VP) and Frederick Retschlag (Secretary), Schultz launched the Harmony Company in 1892 with a capital stock of $25,000. The firm’s name was actually a bit unusual for its time—paying homage to the broader artform itself rather than the men involved or the products produced. Something like the “W.J.F. Schultz Musical Instrument MFG Co.” would have been more par for the course.

Branding aside, young Mr. Schultz [pictured] was taking a considerable risk leaving Lyon & Healy and going out on his own. Harmony started out with just four workers on staff, and it rented out a mere two rooms in the old Edison manufacturing building on the river (current site of the Civic Opera House). In February, they gleefully made their first sale—a pair of guitars to the Chicago Music Company. The ice was broken.

Branding aside, young Mr. Schultz [pictured] was taking a considerable risk leaving Lyon & Healy and going out on his own. Harmony started out with just four workers on staff, and it rented out a mere two rooms in the old Edison manufacturing building on the river (current site of the Civic Opera House). In February, they gleefully made their first sale—a pair of guitars to the Chicago Music Company. The ice was broken.

Just three months later, orders had increased to the point that the company needed more space, and operations were moved to a facility at Chicago Avenue and Green Street. The ice was now a rolling snowball, if you don’t mind a mixed metaphor.

Even after the economic recession of the 1893, Harmony managed to find its footing, expanding to 40 workers and earning a national reputation in remarkably short order. The firm’s original specialty was violins, but from early on, the business plan was to serve not only the orchestral elite, but the everyday citizen. Good instruments, reasonable prices.

By the dawn of the 20th century, Harmony’s factory had moved a few more times—Ann & Lake Street; Homer & Campbell Street; Clybourn & Herndon Street—before it finally found a longer term home in a three-story, 30,000 sq. ft. space at 1750 N. Lawndale Avenue. That building would soon double in size with new additions, and would remain the Harmony HQ from 1904 through 1940. It would wind up better known locally, however, as the eventual Lincoln Logs plant in the 1950s and ‘60s. Now a storage facility, the building is still visible today from the 606’s Bloomingdale Trail.

[The former Harmony plant at 1750 N. Lawndale, in early 1900s vs. present day]

[The former Harmony plant at 1750 N. Lawndale, in early 1900s vs. present day]

Sears Years

While Harmony remained a noted violin manufacturer during its early years at the Lawndale plant, its output was evolving with the popular tastes of the day. Mandolin orchestras were major attractions around the turn of the century, and demand for the instrument was at an all-time high, so Harmony ramped up its mandolin production. Banjos were utilized in trad folk performances and trendy new ragtime shows, so Harmony made more banjos. Classical six-string guitars were re-imagined by designers like Christian Martin and Orville Gibson as louder, steel-string all-purpose instruments, and so Harmony got more skin in that game, too.

William Schultz never had to fear making a major miscalculation, because he knew as well as anyone that music itself—providing the giant canvas it does—would never wain in the public interest. As long as Harmony kept up with the trends, demand would always outpace supply, and there would be money to be made. By selling most of their instruments through wholesalers like Sears Roebuck, there was also a comfortable ecosystem in place, in which Harmony could focus on its bread and butter—manufacturing—without worrying about the growing complexities of distribution.

For Sears-Roebuck, however, that established status-quo wasn’t quite sufficient enough. By 1916, when Hawaiian music had emerged as America’s latest craze, Chicago’s mail order giant decided it wanted to properly corner the market on ukuleles, flat-tops, and slide guitars. Unsurprisingly, the Harmony Company—in the span of just a few years—had become the country’s largest maker of such instruments. And so, rather than just selling Harmony products, Sears now aimed to put the whole operation under its tent.

For Sears-Roebuck, however, that established status-quo wasn’t quite sufficient enough. By 1916, when Hawaiian music had emerged as America’s latest craze, Chicago’s mail order giant decided it wanted to properly corner the market on ukuleles, flat-tops, and slide guitars. Unsurprisingly, the Harmony Company—in the span of just a few years—had become the country’s largest maker of such instruments. And so, rather than just selling Harmony products, Sears now aimed to put the whole operation under its tent.

In his younger days, William Schultz might have balked at such an offer. But he was now on the doorstep of 60, and was the last man standing from Harmony’s original group of investors. The Great War overseas was also putting Schultz and many of his fellow German business owners in a sometimes uncomfortable position in Chicago’s high society. He opted to sell to Sears-Roebuck, and was retained as president for just a year afterwards. Harmony was now a subsidiary of the mighty Sears conglomerate.

In 1917, Harmony’s capital stock, under its new ownership, was increased to $100,000. There were roughly 125 workers employed at the Lawndale plant (mostly a mix of Germans and Latinos), and more than 70,000 instruments were leaving the facility each year. That would jump over 100,000 by 1920.

While some instrument makers had seen the arrival of the gramophone and recorded music as a serious threat—something that would discourage people from wanting to play their own instruments—the opposite may have been true. Exposure to new sounds planted seeds of interest in people from all walks of life, and the Harmony-Sears partnership would prove wildly successful in satiating those needs.

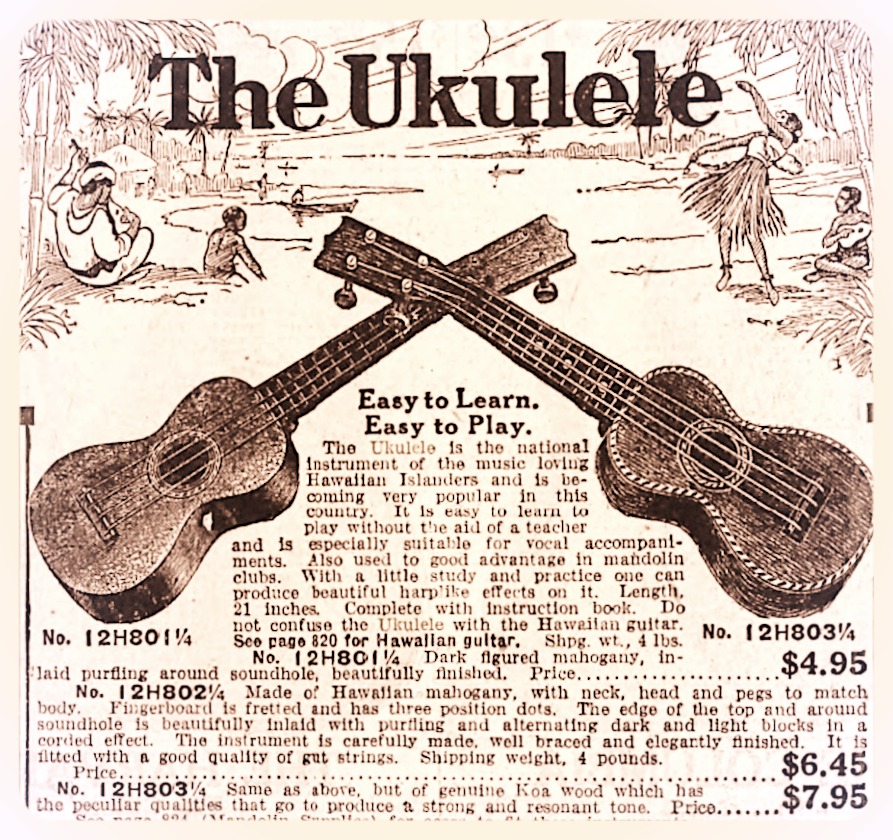

[Harmony ukuleles, uncredited, in the 1917 Sears Roebuck catalog]

[Harmony ukuleles, uncredited, in the 1917 Sears Roebuck catalog]

By Any Other Name

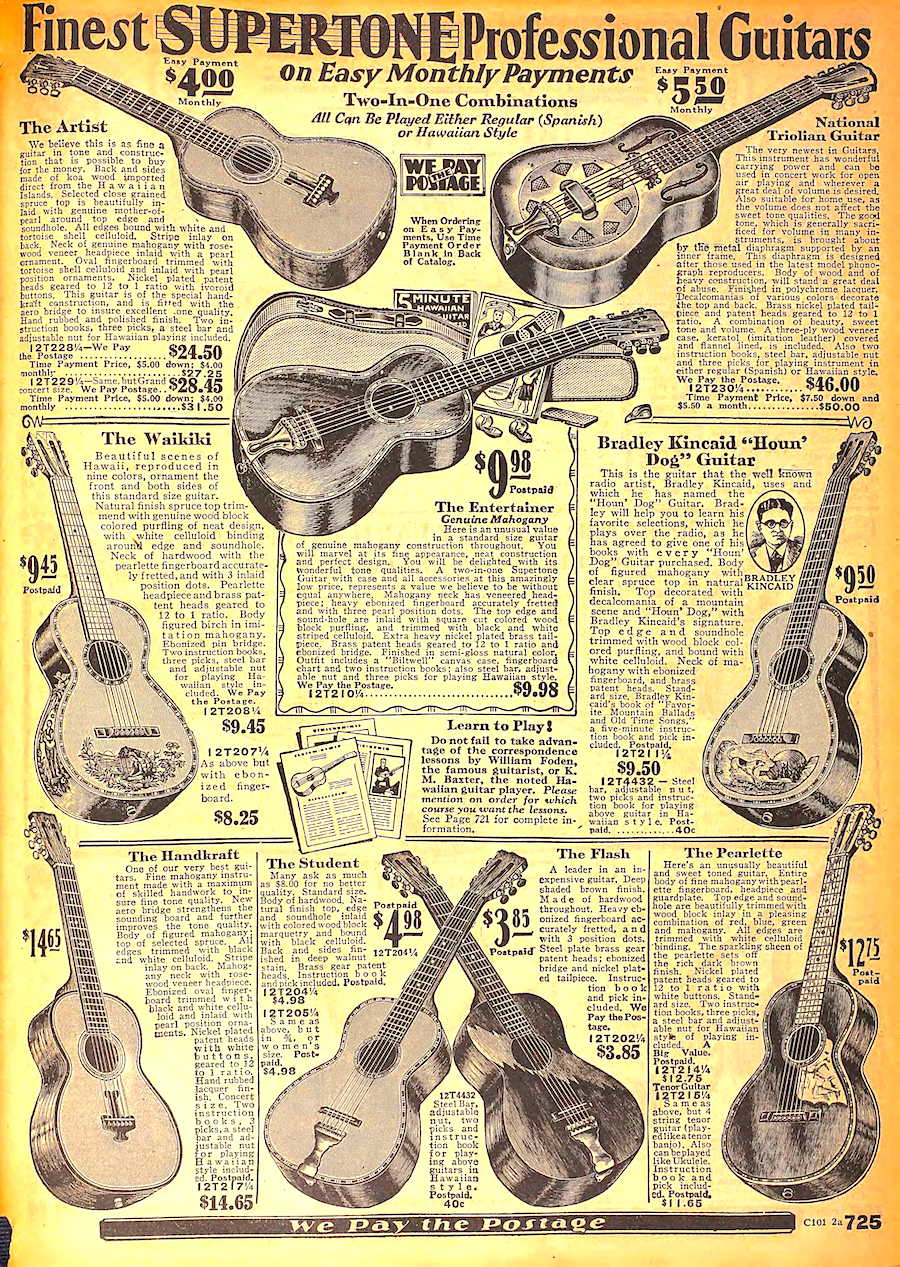

With World War I in the rearview, Harmony’s international exports jumped dramatically, and the company soon made more stringed instruments than any other American manufacturer. If there was any downside to the Sears Years, it was only that Harmony had sacrificed much of its own brand recognition for the sake of maximizing its order intake. The early guitars, mandolins, and ukes they produced for Sears were advertised not as “Harmony” instruments, but under Sears’ own “Supertone” (and later Silvertone) brand name.

During the 1920s, new company president Jay Kraus—a former silverware manufacturing manager with Chicago’s Albert Pick & Co.—opened up the Lawndale plant to even more off-brand orders. Any outside wholesaler requesting a minimum of 100 instruments could hire Harmony to build them. Since Sears-Roebuck benefited from these deals with its controlling interest, they apparently had no beef with Harmony “jobbing” for other music companies, and the company did so with gusto, soon eclipsing an output of 400,000 instruments per year by the late ‘20s.

During the 1920s, new company president Jay Kraus—a former silverware manufacturing manager with Chicago’s Albert Pick & Co.—opened up the Lawndale plant to even more off-brand orders. Any outside wholesaler requesting a minimum of 100 instruments could hire Harmony to build them. Since Sears-Roebuck benefited from these deals with its controlling interest, they apparently had no beef with Harmony “jobbing” for other music companies, and the company did so with gusto, soon eclipsing an output of 400,000 instruments per year by the late ‘20s.

The business model turned Harmony into an extremely profitable enterprise—even during the subsequent Depression years—but it also began to push them further into the category of second-tier “budget” or “beginner” goods.

As a much later consequence for antique instrument collectors, identifying every type of Harmony ukulele or guitar can also prove an impossible headache. For every instrument with the actual Harmony label on it, there are likely another 100 out there—made by the same hands—with some other name. This only becomes a bigger problem when you get into the ‘30s, ‘40s, and ‘50s, as Harmony either bought out old competitor brands or produced familiar names for other companies—La Scalla, Stella, Sovereign, Valencia, Vogue, Airline, Holiday, Kay, and Regal, to name a handful.

Fortunately, Jay Kraus didn’t completely dismiss the value of a little bit of brand recognition. He strategically cherry picked the best opportunities to connect a potentially lucrative new instrument design with the Harmony name, and few cases of this produced better returns than his company’s long relationship with a talented musician named Roy Smeck.

Laying the Smeck Down

Born in Reading, PA, in 1900, Roy Smeck was professionally known as “The Wizard of the Strings”—a nod to his versatile talents on the guitar, lap steel, banjo, ukulele, and plenty others. Maybe more significant than his virtuoso skills, though, was his unique place in history—well positioned at the convergence of mainstream sound recording, radio, and moving pictures.

While he had already earned plenty of fame on the Vaudeville circuit, Smeck entered a new level of celebrity in the late 1920s after starring in some of the earliest Vitaphone “talkie” pictures for Warner Bros. Among his new fans was Harmony’s young president Jay Kraus, who made a point of tracking Smeck down after a 1926 performance.

[Roy Smeck performs in the Vitaphone film “Wizard of the String: His Pastimes” from 1926]

“At the Oriental Theater in Chicago,” an elderly Smeck remembered in a 1984 interview with The Resonator, “Mr, Kraus, president of Harmony company, made me an offer [to produce] a Hawaiian guitar, uke, banjo and guitar. By that time I had the whole act, including fifty uke solos: ‘Yes, Sir That’s My Baby’ in 12 countries, the 3-banjo effect, the talking Hawaiian guitar on ‘Mama Blues,’ and Bill Robinson’s stairs routine on uke.” In response to Kraus’s hefty sponsorship offer, Smeck said he could only ask one thing: “How long can I keep fooling them?”

Kraus’s original plan was to work with Smeck on designs that they would dub the Roy Smeck Vitaphone series. But when Warner Bros. killed that plan, Kraus settled for a halfway solution: The Roy Smeck Vita-Uke and Vita-Guitar.

“The Roy Smeck Vita-Uke provides a combination of all the popular features of the ukulele with a new and unusually brilliant tone,” Kraus told The Music Trades upon the instrument’s debut in 1927. “It is a decided innovation and I feel sure that it will become extremely popular with ukulele players everywhere. It has an exceptionally pleasing design.

“The Roy Smeck Vita-Uke provides a combination of all the popular features of the ukulele with a new and unusually brilliant tone,” Kraus told The Music Trades upon the instrument’s debut in 1927. “It is a decided innovation and I feel sure that it will become extremely popular with ukulele players everywhere. It has an exceptionally pleasing design.

“There are two sound holes, cut in the shape of seals, which we have found aid materially in producing the unusual volume and quality of tone. The instrument is of the finest construction. The body and neck are made of figured mahogany, while the top is of selected, close-grained spruce. The instrument is finished in lacquer, which is hand rubbed and polished.”

Few of these design elements, it should be noted, came from the mind of Smeck himself. Wizard though he was, he acknowledged decades later that it was Kraus and Co. who really carried the reins on such things.

“I didn’t actually design any instruments,” Smeck said. “They would show me the models they wanted to use my name on and I would show them the kind of action that I liked. The ease of playing an instrument is very important to me. Besides action, my only preference for the f-hole arched top guitar was that it have a body about 16 inches wide. I had them make the electric Hawaiian guitar with a large felt bottom so it wouldn’t slide off the player’s lap.”

If there was any specific inspiration for cutting the sound holes in the shape of seals (as in, the sea animal), nobody—including Smeck—seemed to know it.

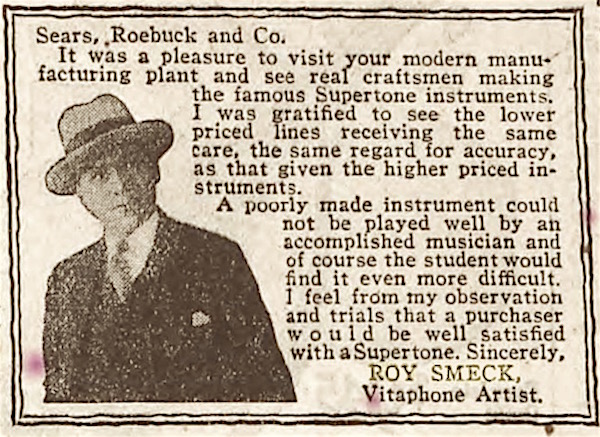

In any case, the Vita line and its sister Supertone instruments (made for Sears) became huge sellers. Accordingly, Smeck made a visit to the Harmony plant in 1928 and later provided a quote for the Sears-Roebuck catalog later that year:

“It was a pleasure to visit your modern manufacturing plant and see real craftsmen making the famous Supertone instruments,” he wrote. “I was gratified to see the lower priced lines receiving the same care, the same regard for accuracy, as that given the higher priced instruments.

“A poorly made instrument could not be played well by an accomplished musician and of course the student would find it even more difficult. I feel from my observation and trials that a purchaser would be well satisfied with a Supertone. Sincerely, Roy Smeck. Vitaphone Artist.”

Variations on the original Roy Smeck uke designs would remain part of the Harmony arsenal for the next 43 years. The soprano ukulele in our collection was listed for $13.50 in Harmony’s 1959 catalog, and was described as such: “The stage and record star Roy Smeck endorses this uke as top favorite for playtime music. Of selected mahogany, accurately made, carefully finished. Brown, mahogany eggshell lacquer finish. Accurately molded fingerboard. Non-slip tuning pegs. Standard size, 6-1/2 x 20-3/4 in.”

[Ukulele page from 1959 Harmony catalog]

[Ukulele page from 1959 Harmony catalog]

Jay’s Way or the Highway

In 1922, a 29 year-old Jay Kraus—then still a manager with Albert Pick & Co.—penned an editorial for Hotel World magazine entitled “The Care of Your Silver Service.” Within one paragraph of that piece, he manages to reveal the sensibilities that would define his eventual five decades of leadership with the Harmony Company. All you have to do is swap out the references to silverware with the comparable tools of the musician.

“A piece of silverware—be it common spoon or fork or finest piece of hollow ware—is really a work of art. Artistic minds have designed it, trained intellects have produced the equipment with which is was made, skilled hands have fashioned the ware itself. For all the ages, silver has been esteemed and akin to luxury. Today when modern manufacturing processes have brought its cost to within reach of all, it should be esteemed no less and, most of all in the restaurant, held worthy of proper care so that its condition shall always please the most fastidious.”

“A piece of silverware—be it common spoon or fork or finest piece of hollow ware—is really a work of art. Artistic minds have designed it, trained intellects have produced the equipment with which is was made, skilled hands have fashioned the ware itself. For all the ages, silver has been esteemed and akin to luxury. Today when modern manufacturing processes have brought its cost to within reach of all, it should be esteemed no less and, most of all in the restaurant, held worthy of proper care so that its condition shall always please the most fastidious.”

Kraus was still just 32 when the Sears-Roebuck board elevated him to the presidency of the Harmony Co. in 1925. He was clearly ideal for the role—combining William Schultz’s artisanal perfectionism with a savvier understanding of 20th century big business. Ten years into the job, he was joined by a new sales wiz and future VP, Charles Rubovits. The pair were so determined and sure of themselves—and validated by unlikely success in the 1930s—that they began to tire of taking orders from the old suits at Sears.

A bit of a power struggle ensued, and for a time, it looked as though Kraus had come out on the wrong end. He resigned from his position in 1940, with John T. Higgins taking over his role. The change was super duper temporary, however.

[The 1937 Sears catalog was one of the last during Harmony’s time as a Sears-Roebuck subsidiary]

[The 1937 Sears catalog was one of the last during Harmony’s time as a Sears-Roebuck subsidiary]

A few days before Christmas, Kraus and a team of allies formed a new corporation and proceeded to buy up the controlling stock of Harmony. It had the looks of a hostile takeover, but it’s hard to say whether Sears was truly blindsided by the move. Kraus, after all, already had a new factory ready and waiting to become the next Harmony headquarters. Sears may simply have elected to bow out of the instrument manufacturing game after crunching the proverbial numbers.

“We are pleased to announce that the inventory, machinery and equipment, and good will of The Harmony Company have been purchased by a new corporation recently organized by Mr. Jay Kraus,” purchasing agent J.H. Graser informed the media just after the buyout. “In that connection the old Harmony Company has changed its name to Melody Instrument Company, and the new corporation organized by Mr. Kraus will be known as The Harmony Company. Operations of the old Harmony Company were discontinued on December 21, 1940. The new Harmony Company is located at 3631-33 South Racine Avenue, Chicago, Illinois, and began operations on December 23, 1940.”

[The Harmony factory at 3633 S. Racine Ave. in 1941]

[The Harmony factory at 3633 S. Racine Ave. in 1941]

Despite the short-lived creation of the Melody Instrument Company (which existed mainly to handle old invoices and legal paperwork), Sears washed its hands of the business. In turn, Jay Kraus re-launched Harmony at a 37,000 sq. ft. factory in the famed Central Manufacturing District, just a block from his old Albert Pick & Co. stomping grounds. Initially, he brought a reduced team of 80 workers with him, but it was still enough manpower to produce 250 different models and 1/3 of the total fretted instruments made in the U.S. (the ratio in 1941 was 75% guitars, 15% mandolins, and 10% ukuleles). Chicago had long since become the country’s unrivaled guitar manufacturing hub, and no company produced more of those axes than Harmony.

Inside the Racine Avenue Plant

In September of 1941, Harmony was featured in an article in the Central Manufacturing District Magazine.

“When The Harmony Company located its factory in the Central Manufacturing District a short time ago,” columnist David S. Oakes wrote, “it may be said to have added a new note to an industrial roster whose amazing range of business classifications seems to know no limit. Also it lent emphasis to the fact that no day passes in which the District does not impinge upon the commerce of the entire world, for a tour among the customers of this concern would require the globe to be girdled.”

[Sidney Katz (left), assistant to the company president, plays a tune on a Harmony cutaway guitar for assistant secretary Catherine Barkoulies and Vice President Charles Rubovits.]

[Sidney Katz (left), assistant to the company president, plays a tune on a Harmony cutaway guitar for assistant secretary Catherine Barkoulies and Vice President Charles Rubovits.]

Just a few months later, America’s entry into World War II cast a sudden cloud of doubt over Harmony’s global enterprise. Less than a year into their operation as an independent business, Jay Kraus and Charles Rubovits faced not only the loss of workers to the war effort and the limitations caused by rationing, but also a giant depletion in their international clientele.

Kraus himself formed the Music Industry War Council to game-plan the years that followed. Efficiency became paramount at the Racine plant, and any long term hopes of competing with the likes of Martin and Gibson were left to the wayside. Harmony was now committed to its role as a maker of instruments for the wholesale trade, and that even included a continued relationship with Sears, making the popular Silvertone series for decades to come.

At the Harmony factory, “approximately one-fourth of the total area was located in the basement, where lumber storage and rough initial operations are accommodated,” Oakes wrote. “The balance is represented by the entire third floor which, with the exception of an adequate office reservation at the front, is devoted to manufacturing and shipping. The scheme of layout throughout is a model of efficiency, for every inch has been utilized.”

At the Harmony factory, “approximately one-fourth of the total area was located in the basement, where lumber storage and rough initial operations are accommodated,” Oakes wrote. “The balance is represented by the entire third floor which, with the exception of an adequate office reservation at the front, is devoted to manufacturing and shipping. The scheme of layout throughout is a model of efficiency, for every inch has been utilized.”

Again, the logical move would have been to cut corners in the selection of materials and the use of manual labor, but Kraus—ever still the silverware (and Silvertone) purist—continued shipping in quality rosewood, ebony, and mahogany for Harmony’s better instruments, and he had his superintendent Joseph Elias run a tight ship in every department, from the shipping-and-receiving to the woodworkers, machinists, sanders, gluers, and assemblers.

“Practically every stage in the evolution and movement of a guitar from the unsawed board to an individual kraft wrapper is also one of inspection. The process of quality assortment begins at the foot of the lumber chute in the basement where the raw stock arrives from cars set on the Chicago Junction Railway sidetrack alongside the building. At each machine it continues, and at the benches where the hand touches are applied it is intensified until the finished product represents the ultimate in its class. In working the various woods into instruments, observance of the grain is an all important consideration, and every operation, especially on the machines, must be guided so as to insure a smooth and optically attractive result.”

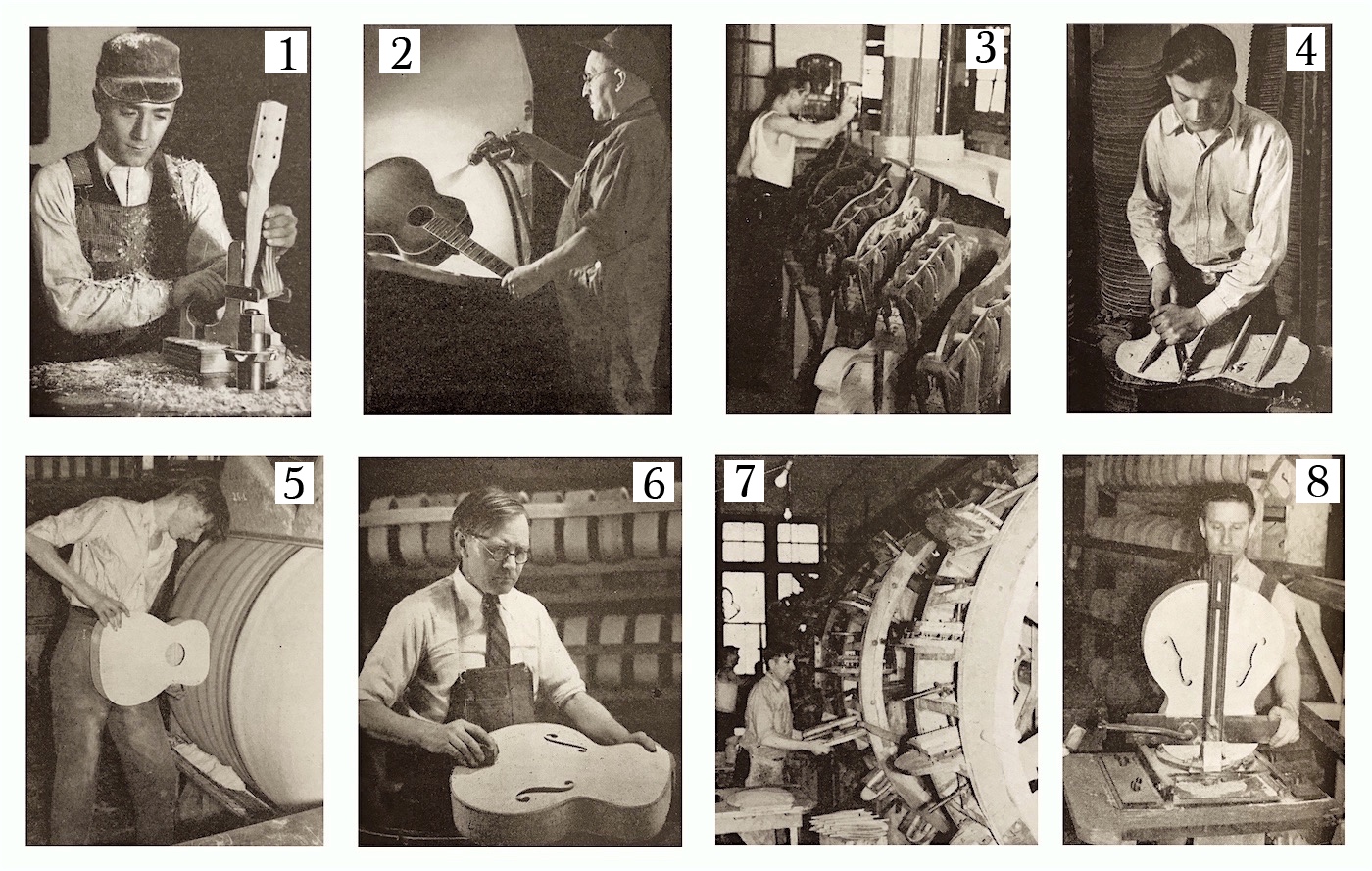

Various Stages of Harmony Guitar Production in 1941

1. Shaping the neck for its dovetail into the guitar soundbox

2. Grain and color effects added

3. Bending stoves used to form the side panels of the guitars

4. Braces are wrought and applied

5. Drum sanders smooth away broader portions of the instrument

6. Hand sanding and inspection from experienced craftsmen

7. Wheels revolve to measure gluing cycles as braces are applied to the sound box

8. Using special jig and router to cut dovetail joint into the soundbox

Sign of the Times

Harmony survived the war, and by the end of the 1940s, the business was essentially back at full power, employing 150 workers and producing more than half of all fretted instruments in the country. Overseas exports never did return as hoped, however, due in large part to exchange rates. Still, the mainstreaming of musical education in America and the emergence of televised performances helped grow public interest and balance out the international losses.

After a slow period, even the ukulele had risen to prominence again, re-popularized by another string wizard, Arthur Godfrey. Jay Kraus gleefully told reporters that he’d sold nearly 150,000 ukes in 1949, and that he expected it to soon eclipse 300,000.

A few years later, as Harmony celebrated its 60th anniversary, the company was again featured in the official magazine of the Central Manufacturing District. By this point, Jay Kraus (now nearly 60 himself) had been elected president of the Central Manufacturing District in his own right, and he’d served similar leadership roles with the National Association of Musical Merchandise Manufacturers and the American Music Conference. From this lofty perch, he gave reporter M.D. Schopp a very rosy outlook on the future.

“The public is getting more music conscious,” he said. “More and more musical instruments are being shown in national consumer advertising of every and all kinds of non-musical products. It’s one of the signs of the times that even the advertising agencies recognize.”

“And there is no company fostering the sign of the times more earnestly,” Schopp noted, “than The Harmony Company and its leaders through their outside musical interests and through their own instruments, ‘best sellers,’ as Mr. Kraus calls them. The most untalented amateur, by learning to play guitar, mandolin, or ukulele, can advance his musical interest and education. Stringed fretted instruments are here to stay as a valuable self-expression of music, one of the world’s most valuable assets.”

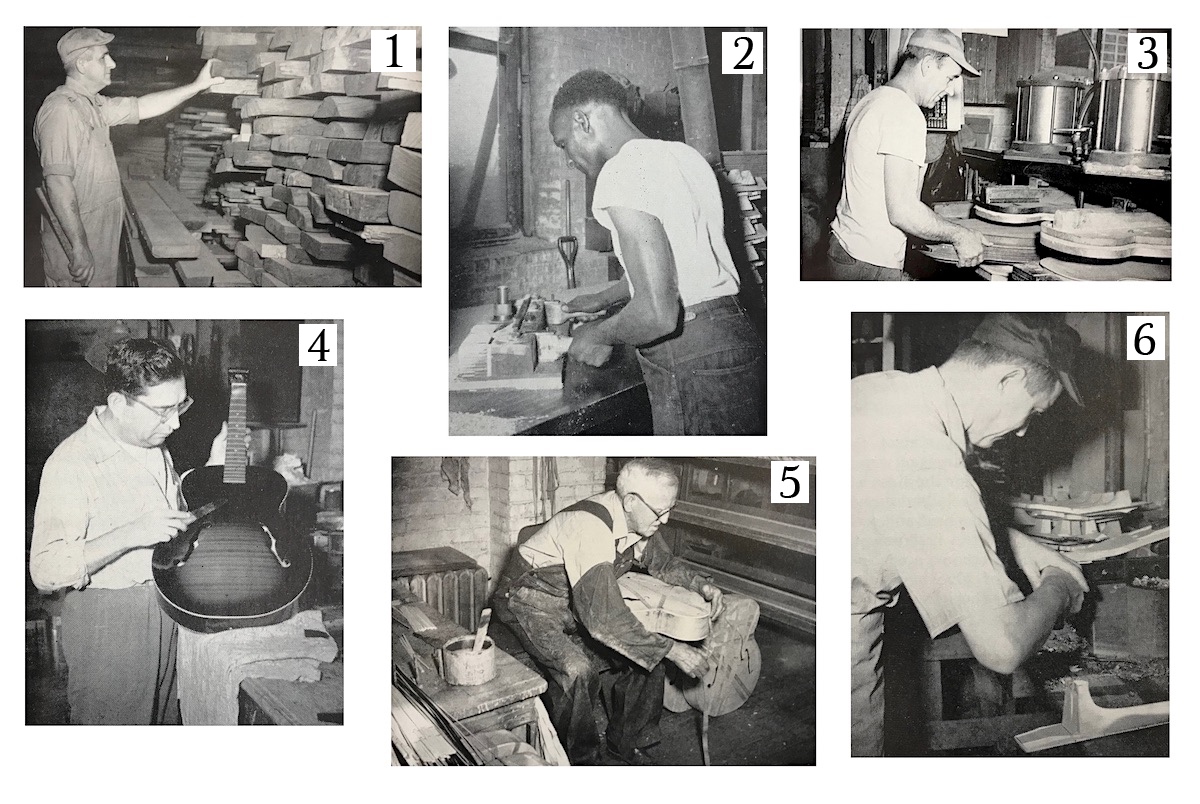

Harmony Guitar Production, 1952

1. Foreman Frank Elias chooses a good batch of Brazilian rosewood

1. Foreman Frank Elias chooses a good batch of Brazilian rosewood

2. Shaping a neck on a spindle revolving 7,200 times per minute

3. Resin adhesives and extreme heat fuse the top and bottom of the guitar to the frame

4. Checking the finish for blemishes

5. Celluloid bindings are glued by August Hansen, a 50 year veteran of the Harmony factory

6. Spoke-shaving, like hand carving, couldn’t be done by machines

Last Hurrah

In a phenomenon that’s hardly unusual for major tech and electronics manufacturers in Chicago, the 1960s was Harmony’s commercial high point and their swan song.

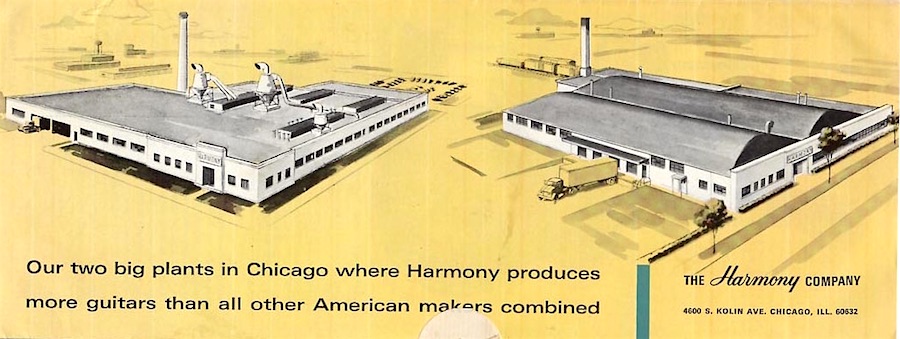

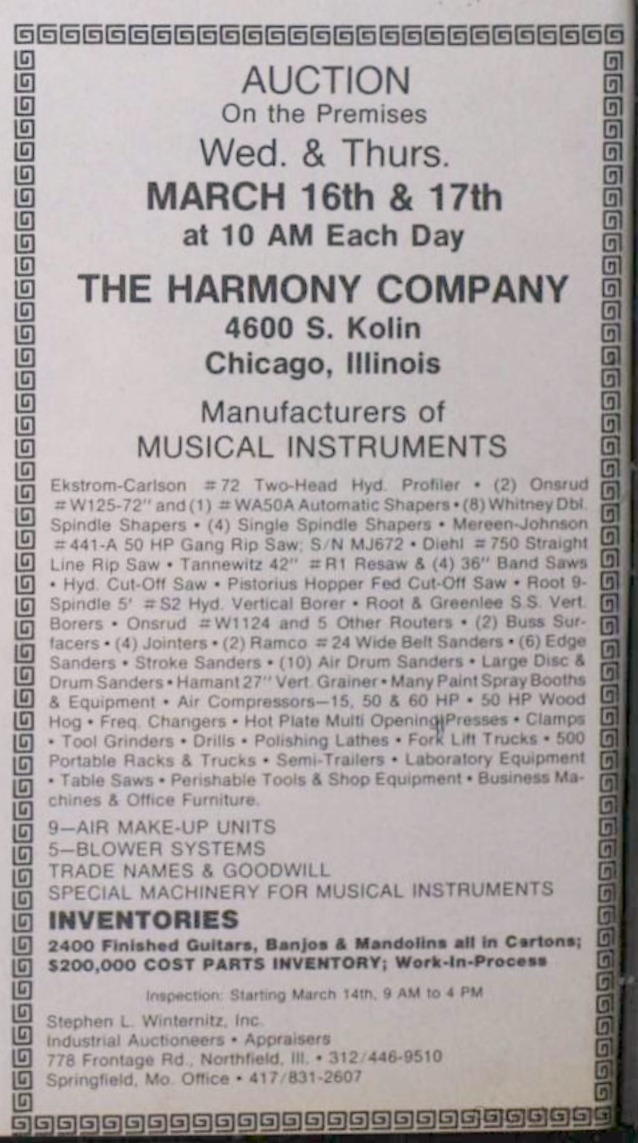

In 1962, the company began its fourth and final era with a move to a new, more modern factory space at 4600 S. Kolin Ave. in Archer Heights. A second plant was added on the same block a few years later, providing a whopping 125,000 sq. ft. of space. By any measure, Harmony was making more guitars than anyone else on planet Earth in 1965, and considering the explosion of interest generated by both rock n’ roll and the folk revival, there couldn’t have been a better time to be at the top of that category.

And yet, Harmony was just a decade away from its ultimate demise. The company’s failure to recapture the global market, combined with the rise of new competition from rock n’ roll crazed Japan and other countries, would seal their fate.

In the summer of 1968, a then 62 year-old Charles Rubovits attended a panel discussion in Chicago hosted by the Guitar and Accessory Manufacturers Association. The mood in the room was one of moderate discomfort. Sales numbers were down, and the guitar boom—at least for American manufacturers—seemed to be stalling.

“The guitar industry has matured,” Rubovits assured the group at the time. “The market has leveled off at a higher plateau than ever before. We will go on from here to a new peak, which can start in any direction.”

These were optimistic words, but as noted earlier, Kraus and Rubovits were only willing to go so far when it came to changing their business model. The duo remained stubbornly unwilling to expand Harmony much beyond its longtime workforce of 150-200 people, nor to fully automate construction of cheaper instruments. Wise and innovative as they’d been during the Depression and War years, they were both now old men, and perhaps a bit too stuck in their ways.

“We had the know-how, but we didn’t have the guts,” Rubovits recalled years later. “We were very successful [in the 1960s], so we didn’t want to do more, and as a result the Japanese began to get a bigger and bigger share of the market.”

“That’s why we eventually went out of business,” former Harmony vice president Larry Goldstein told Reverb.com in 2015. “We couldn’t compete with the stuff coming in from Japan in those days because they were automated. We were still doing everything by hand, even on the starter guitars. Guitars that were selling for $19 were being made entirely by hand.”

“That’s why we eventually went out of business,” former Harmony vice president Larry Goldstein told Reverb.com in 2015. “We couldn’t compete with the stuff coming in from Japan in those days because they were automated. We were still doing everything by hand, even on the starter guitars. Guitars that were selling for $19 were being made entirely by hand.”

Three months after Rubovits spoke at the guitar seminar, he was suddenly elevated to the role of president after 33 years with the firm. Jay Kraus, his mentor and the man most synonymous with The Harmony Company, had died at age 75.

“We had a fire at the Harmony factory [in 1968],” Larry Goldstein recalled to Reverb.com. “The garbage company used to come in to pick up the garbage on the inside of the building. When they emptied the container into the truck, there was a spark, which ignited the sawdust, wood and acetate in the garbage.

“All this was burning in the truck, and the driver was going to try to drop it inside the building. The foreman used his head and jumped in this truck and drove it out to the parking lot. That was Jay Kraus’s last day at the factory. He had inhaled too much of the smoke. He went home that night and died of a heart attack. We think it was from the fumes he inhaled while he was standing there watching what was going on.”

One hesitates to utilize the metaphor of a dumpster fire, and Goldstein may be well incorrect presuming Kraus’s death was caused by one. But there can be little argument that Harmony never recovered from that day.

Charles Rubovits, while a fully capable leader, was given an impossible mission, and by 1977, his business had run out of fight.

“The factory equipment and other assets were sold at auction to satisfy the creditors,” Rubovits told American Guitars magazine, “and they finally liquidated, paying off ten cents on the dollar.”

In the post-war era alone, from 1945 to 1977, Harmony is believed to have produced an astounding 10 million guitars. That doesn’t even count the ukes, banjos, mandolins, etc. It was an enormous and enormously successful company that probably deserves far greater credit as a groundbreaking Chicago institution.

“Our first aim throughout these many decades,” the company stated in its 1966 catalog, “has always been to produce DEPENDABLE guitars that will give years of service to their owners—years of musical satisfaction, years of fun.

“. . . Our guarantee means exactly what it says—and, should any problem ever arise, we’re right here in Chicago to back it up.”

Sources:

“They Shall Have Music . . .” by David S. Oakes, Central Manufacturing District Magazine, September 1941

“There’s Harmony in the District,” by M.D. Scopp, Central Manufacturing District Magazine, November 1952

“Keeping America in Harmony” – Chicago Tribune, March 22, 1992

“The Care of Your Silver Service,” by Jay Kraus, Hotel World Vol. 94, 1922

Harmony Database – Harmony.Demont.Net

Roy Smeck: The Wizard of the Strings in His Life and Times, by Vincent Cortese, 2004

“Take a Photo Tour of the 1904 Harmony Instrument Factory” – by Chris McMahon, Reverb.com

“Talking with Roy Smeck” – The Resonator, 1984

“The Old Harmony Makes the New Melody Company” – Presto Music Times, 1941

“The Harmony Company” – AcousticMusic.org

“The Harmony Company” – The Purchaser’s Guide to the Music Industries, 1922

“The Harmony Company” – Manufacturing and Wholesale Industries of Chicago, Vol. 2, 1918

“GAMA Panelists Stress the Popularity of Guitar” – Billboard, July 6, 1968

The Electric Guitar: A History of an American Icon, by Andre Millard

Archived Reader Comments:

“In the 1960’s The U S music companies were doing a great business, The British invasion and Rock music in general really helped push the sales. In the middle to late 60’s The Asians came in with 2nd rate musical gear and under cut Fender, Gibson, Guild, Washburn and other U S Musical manufacturer’s and Suppliers. Japan’s Drums and Guitars were made with lower grade metal and wood. I have researched their guitars and drums. The United States companies used a high quality grade of wood Like a Maple or Birch, And a high quality metal for their instruments. Japan used Luan “Ply wood” which is low grade wood. The Metal Japan used was much thinner, lighter and not forged as well. Our Government should have stepped in and either not allowed them to sell here, or put a Tax on imports so high that it would have given Our U S companies a chance to survive. Japan Paid their Workers very little , They used Low cost supplies, Wow this sounds very much like the way today’s companies operate. I wonder where We got the Idea from? Our government allowed other countries to come here and disrupt our economy. I wonder if Japan would have sat still if we tried to do that. My issue is not with Japan but with the leaders at that time in history who had no problem selling Unites States Musical Instrument Companies down the drain.” —Richie Bartolo, 2019

“My father-in-law, who at the time owned a small country store type hardware store/ music shop in Kentucky, drove to Chicago for the auction in 1975 or 1976 and bought as many guitars, mandolins, and ukulele’s that he could fit in the U-Haul he rented and brought them back to Kentucky and sold them over the next 30 years. I have a couple of these Harmony 6 and 12 string guitars today. He said he didn’t pay more than 25 cents on the dollar (in 1976 dollars) for any of them.” —Paul Curry, 2018

“A superb article- really interesting.  ” —Nick R., 2018

” —Nick R., 2018

I have a Harmony Stella H929 that I gig with. When the stamp inside was still visible, it indicated it was made in the autumn of 1954. I bought it a couple of years ago and had a luthier/repairman remove the floating bridge, install a bridge plate and then cut a new bridge out of ebony. It sounds great. And distinctive.

It’s cool to think that a mass-produced guitar from Chicago is still inspiring and making music 71 years after it was built.

What a great article. So interesting to read the history of the company.

I was given a Harmony soprano ukulele from my grandfather when I was 10 in 1972. I never did play it much. Now after all these years, I would love to learn to play but I’ve lost an end screw on one of the tuning pegs. I’ve scoured the internet but can’t seem to find a replacement. I would love to keep the original tuning pegs rather than replace them. Do you know where I could find one? Thanks, Linda

I worked for Harmony co. for seven and a half years. From 1965-1973. Made all the picks and pick plates from that time and also worked on many of the bridges. Spent time in my early years there in handling lumber and in glueing necks and rosewood plates on necks. The story possibly has an error in that the superintendent’s name was Frank Elias not Joseph. The fire that started in that garbage truck was from celluloid scrap that I had thrown out. I worked in a separate area in the factory with the side benders who bent all the guitar and use sides. We worked behind a fire door. I dumped scraps from my celluloid picks and pick plates twice a day in the outside garbage hoppers. The garbage truck fire started from spontaneous combustion. Wood scraps where not throw in the garbage but ground up and used for heating fuel.

We are looking for a bridge for a harmony model number H6272 .It has a green stamp inside that says 1719H6272.It has a golden tag inside and aoval gold tag that says classic guitar.Can you tell me where to go? tonisanford804@yahoo.com

We have two wheels from the Harmony factory, they are steel and oak, very heavy very bigWill sell.

I have been collecting vintage guitars for a few years now, playing for over 30. I have about 300 acoustics. Most Ive found are Harmony and the quality is STILL amazing after all these decades of sitting closets, attics, under beds, in garages, ect. Minimal work needed to make them playable and the best part is the solid woods they used age so well that they have a very unique sound unline anything else. What great guitars, so sad our trade deals killed off such great companies like Harmony. I have a lot of Kay guitars to and while they are great as well, they dont hold a candle to to the old Harmony guitars. RIP Harmony, I dont recognize the new Asian made Harmony in name only as actual Harmony guitars.

Great article…thought you may be able to help me. I have a Maple finished P Bass clone, ST65n, that is a made in Japan Harmony bass. Would you know the history? Who built it, pickups etc. Same for the Harmony Marquis bass. Thanks for providing info on “cool” old instruments. John

I have a few old harmony ukes I really like. One is called the Red label uke.

Any idea what year H used the red labels? Thanks very much

I enjoyed reading the history of Harmony especially since I was fortunate to be a student of Roy Smeck during 1959-1961 at his apartment in NYC. I also had the opportunity to see one of his last concerts in the 80’s & I was interviewed for the documentary being made about his career. Aside from being a great musician he & his family were very cordial.

I have a Harmony Ukulele from the 1960’s or the early 1970’s. Harmony advertised it for $21.00. Which I think is one of the most expensive ones in the catalog. Guessing my parents bought it from Sears. It’s in perfect condition. Wonder if it have antique value? To me, it’s sentimental value is priceless.

Could anyone confirm that the 1936 (Berlin Olympics) commemorative parlour guitars were actually produced in 1936? I am in Scotland and have the Ralph Metcalf, silver medal model, picked it up in a charity shop 20 years ago. Still in fair condition but missing it’s original bridge. Thanks.

I have a violin, Glasser bow, and bag and I can’t find any information on a Harmony violin. Do you know where or who I would contact for more info. I’m looking to sell it. Thanks!

Sadly, the info about the “1975 auction” continues to be repeated…

The company was auctioned off in 1977…

You’re correct, Kent. The included newspaper ad for the auctioning off of Harmony’s inventory was from 1977. It has now been noted.

Hi

so much Harmony history and so few resources. This site is one exception. i am trying to find out when Harmony started adding the moulded plastic fretguards to Harmony Soprano ukes, particularly the Roy Smeck model. i see plenty of “50’s”Roy Smeck ukes on market with plastic fretboards. However in this video the author says they were not added until 1958. it would be good to get a year. We need a Harmony book like the Martin Ukulele one. There are enough resources to have a separate guitar and ukulele book as they were such a prolific maker. if i lived Stateside i would definitely be interested in doibg research on a Harmony ukulele hostory book.

Hello, I have an instrument with headstock labeled Harmony Deluxe (Baritone ukulele). It has a carved headstock, looks like steel frets, looks like fake mother of pearl dots on the fingerboard, the fingerboard and banding on the top look like plastic. It has 3 concentric circles around the sound hole (maybe a decal?). The bottom of the bridge is shaped like the bottom half of a police badge. The top is spruce colored and sides and back are darker. I can’t find anything that looks like it. Could be a Frankenstein. Just wondering if it is really a Harmony and what year it might have been made.

Reach out to me, nat.adams149@gmail.com

When I was about 12( now 70) I fell in love with guitars and filled out a mail order for a catalogue from Harmony. Every day I went to the mailbox eager to get it – seemed to take forever. When I decided on which one to get ( think it was a reddish black acoustic archtop) I then had to beg my dad to buy it( tough job really). From there I upgraded all the way to an H75 Sunburst which I loved even more than hockey. Now after 40 years of not playing, I am back into guitar – 3 in the stable now but the last one will be , as an homage to Harmony, an H53 Rocket Redburst..for me this model completes the circle…

I am a retired luthier now living in Port Charlotte, Fl. My wife and I previously owned a production shop in Pigeon Forge, Tn. for 40 years. In the late 70’s, my good friend,Tut Taylor, passed on to me some items he bought at the Harmony auction and I have 800 Brazilian Rosewood fingerboards that I need to sell since at 83 I have no plans for them. They are not fretted but do have perloid inlay. I’m asking $3.00 each if you take them all.

Outstanding article. The guitars of the early 20th century are still popular in Vast numbers but have such a complicated web of manufacturers,distributors etc. It can be hard to trace some of them. But I’ve found that 8 out of 10 end up being a Harmony. I’ve recently acquired a 1937 Sears catalog model “The Flash” I haven’t been able to find another photo or resale record of this model on the internet. Im wondering how many were produced and if you can give me any information at all about its rarity . Thank you so much.

Dana

Thanks for the great info. in this well written essay. As a guitar enthusiast and historian I was impressed by the personal details of the owner and company history.

There is, I feel an important missing section; The Harmony Company’s foray into the development and manufacture of their electric guitar line during the 1930’s and early 40’s. Although not a big player in the field their design’s we’re unique and well thought out. The one of a kind pickup design suspended on a dowel stick that ran the length of the archtop guitars body isolating it from acoustic overtones was genius. As well, the stunning design of the 1936 cast metal Electric Hawaiian was a visual masterpiece.

great insight, Lynn. Thanks for sharing. I’ll try to add some more detail on the early elec guitars.

Hello,

I own a small music store in CO, and a customer brought in a “The Harmony Company” Classical guitar H605… Orange Top and what looks like Rosewood back and sides! I cannot find this model # anywhere on the internet. Is this thing pretty rare? Any info would be appreciated – especially a selling price – It is in very good condition. I can send pics if you email me. Thank you!

I have a Silvertone guitar with the numbers 4554 900 inside. I have photos I could share. I’d love to track down the exact year it was made. It’s a family heirloom that belonged to a long ago deceased uncle.

I recently found a 1950s Harmony Ukulele at a Salvation Army for $3.99. I didn’t know anything about it when I saw it, but when I saw the screws on the fretboard I knew it was a good find. How can I tell what year it was manufactured? I was able to pinpoint it to the 1950s based on the design of the Harmony logo. BTW my daughters name is Harmony.

Uschi, I think you’ll find that to be a Honda rand guitar from the mid-1980s.

Dear Mr. Cayman,

I’m interested in informations about my guitar.

It’s a 12string model with the number H160A

Can you tell me in which year they produced this guitar?

Thank you!

Sincerely yours

Uschi Saretzki