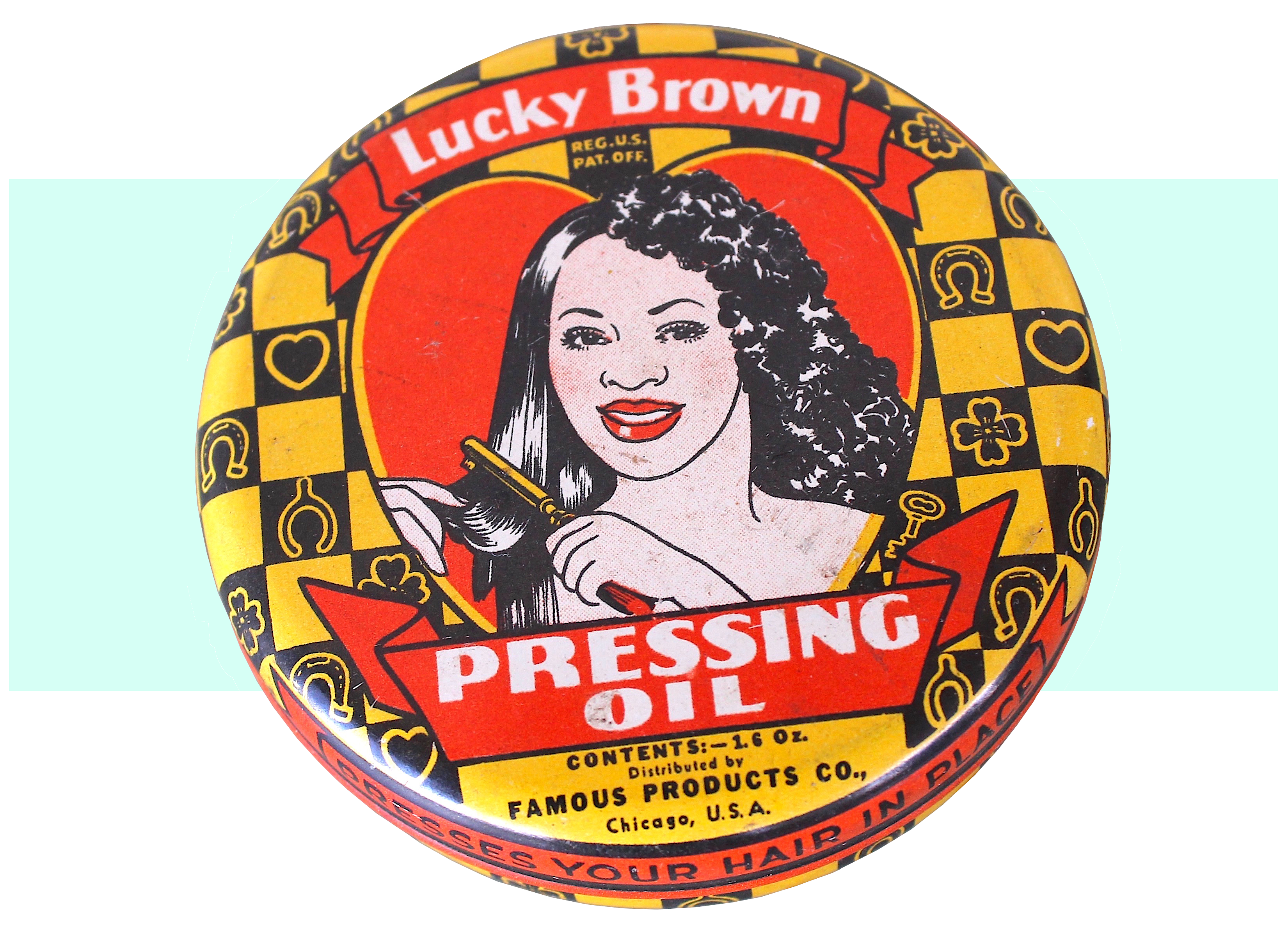

Museum Artifacts: “Lucky Brown” Hair Pressing Oil (1938) and “Slick Black” Promo Poster, c. 1940s

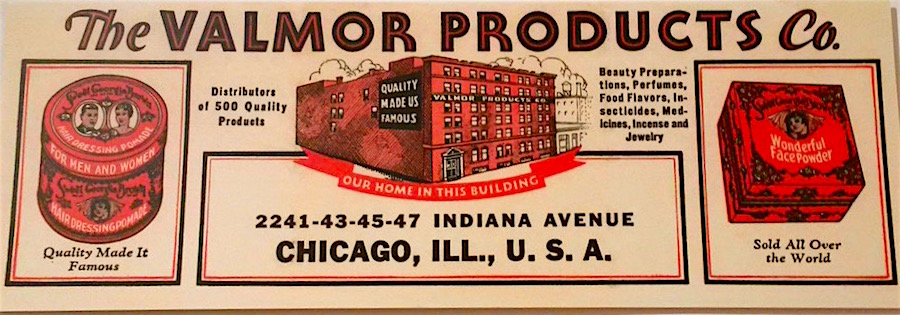

Made By: Valmor Products Co. / Famous Products Co., 2241 S. Indiana Ave., Chicago, IL [Near South Side]

Whether you enjoy debating the ethics of cultural appropriation, the definition of true art, or the line between female empowerment and objectification, the story of the Valmor Products Company basically covers all the bases—like a pulp-novel catalog of 20th century American contradictions.

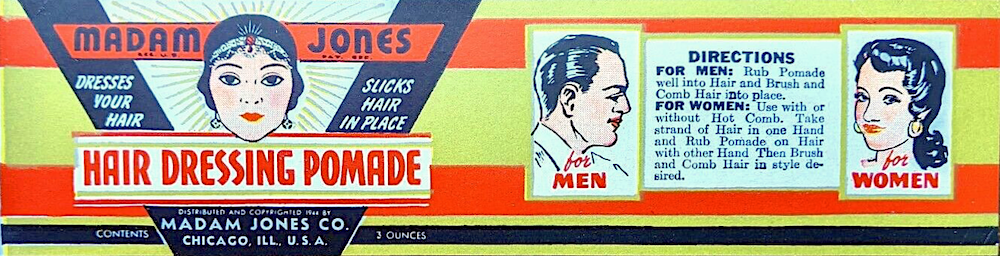

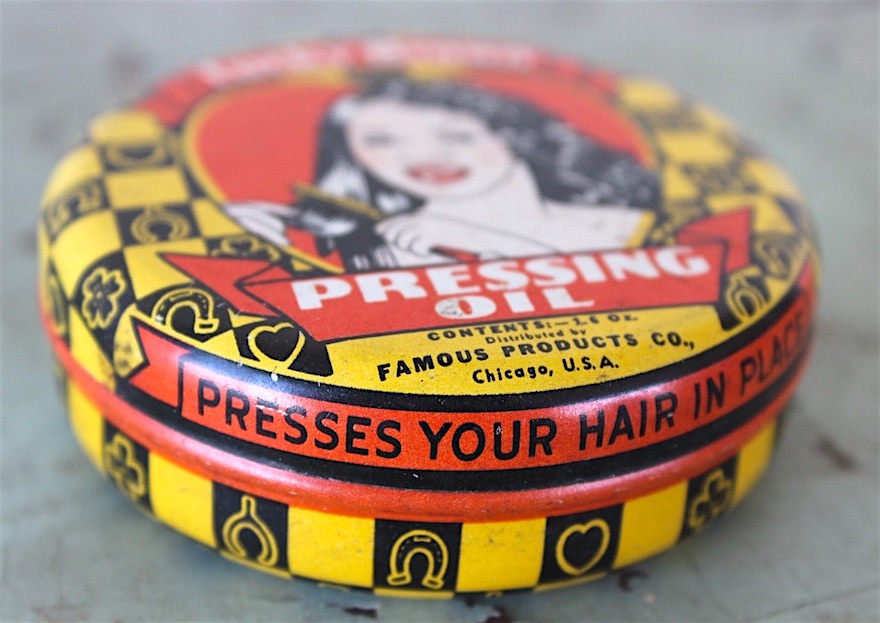

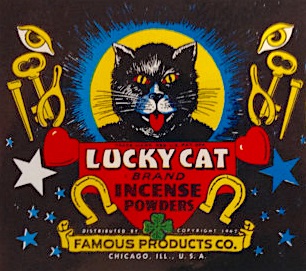

For nearly 60 years, this relatively obscure South Side business—operated by a Jewish husband-and-wife team but catering almost entirely to an African-American audience—produced a mind-boggling inventory of products, from hair pomades, perfumes and skin creams to blues records, dream books, and bizarre “magic” curios. They were sold not only under the Valmor name, but a wide range of company pseudonyms, including Lucky Brown, Madam Jones, King Novelty, and the distributor attached to the 1930s-era tin in our museum collection, Famous Products Co.

For nearly 60 years, this relatively obscure South Side business—operated by a Jewish husband-and-wife team but catering almost entirely to an African-American audience—produced a mind-boggling inventory of products, from hair pomades, perfumes and skin creams to blues records, dream books, and bizarre “magic” curios. They were sold not only under the Valmor name, but a wide range of company pseudonyms, including Lucky Brown, Madam Jones, King Novelty, and the distributor attached to the 1930s-era tin in our museum collection, Famous Products Co.

Seen as cheap drugstore fodder in their own time, these products managed to build the foundation of a highly profitable enterprise during the Great Depression, with mail-order and door-to-door sales accounting for much of the business. It was Valmor’s distinctive, vibrant, and often sexually-charged packaging, however, that would eventually far eclipse the popularity and usefulness of its various goods.

More than 30 years after the business folded, dedicated collectors now scour the globe looking for rare tins and bottles from the Valmor vaults, and in 2015, an exhibition at the Chicago Cultural Center shed new light on the artistic merits of those stunning labels—specifically the contributions of the company’s little-known African-American illustrators Charles C. Dawson and Jay Jackson.

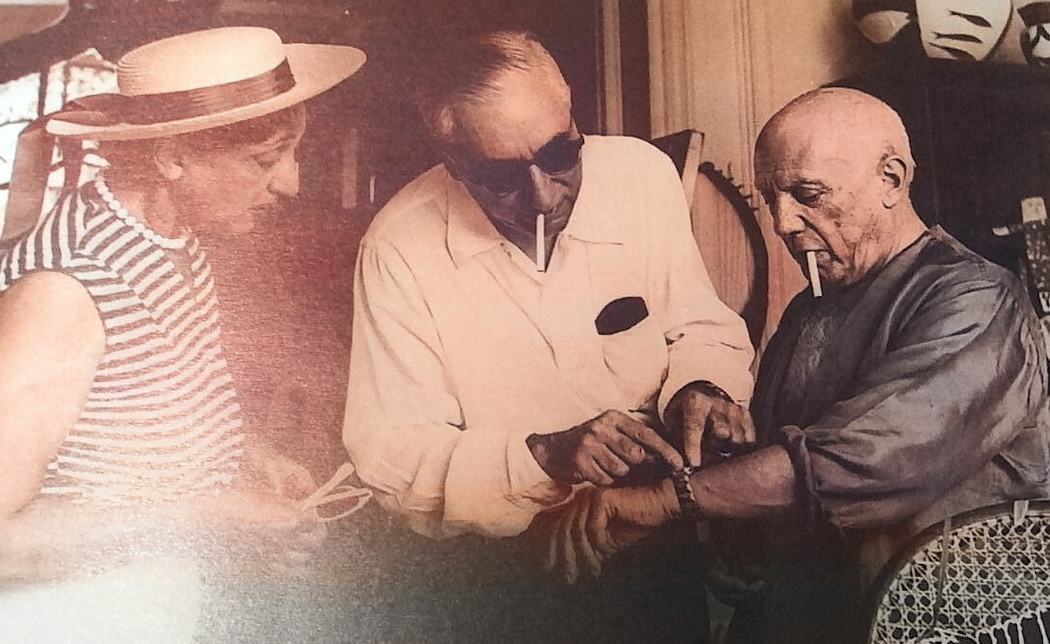

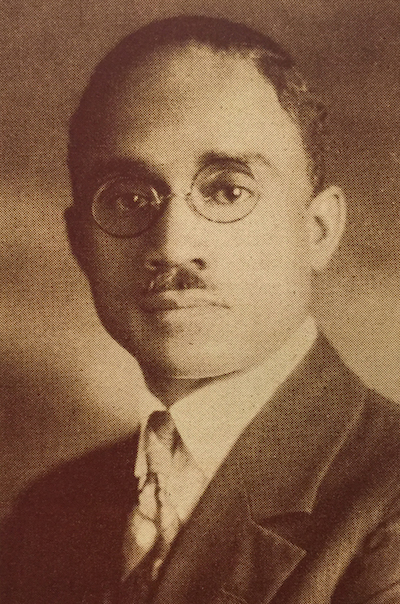

The great shame and irony of all this posthumous recognition is that Valmor’s founder and lifelong president, Morton G. Neumann (1898-1985), was actually one of America’s most prominent and prolific collectors of modern art—he was a personal friend of Picasso, no less. And yet . . . he never seemed to fully recognize the value of the work that had been done for years right under the roof of his own business.

[Morton Neumann, center, with his wife Rose and a dude named Pablo Picasso, 1964. Neumann was a leading collector of Picasso’s works and a bit of a fanboy of the artist. He is seen here presenting Picasso with a custom-made watch in which the 12 digits of the dial are replaced with the 12 letters in P-A-B-L-O P-I-C-A-S-S-O.]

History of Valmor Products, Part I: Humble Beginnings?

When he organized the Valmor Products Company in 1926, Morton Neumann was a 28 year-old journeyman chemist just looking for his piece of the proverbial pie. He’d been in the toiletries trade for a few years, and as a born-and-bred South Sider himself, came to realize that there was a clear shortage of cosmetic products being tailored specifically to the thriving black and Latino communities he encountered everyday in the Bronzeville neighborhood.

What comes next, then, is either a case of astute capitalist opportunism or calculated cultural exploitation, depending on your angle

What comes next, then, is either a case of astute capitalist opportunism or calculated cultural exploitation, depending on your angle

In some respects, Neumann was admirably serving his community as both a merchant and a better-than-equal-opportunity employer. Nearly every listed Valmor Products Co. office over the years was located either in or on the outskirts of Bronzeville, employing many local black residents as warehouse workers and salesmen. The company’s first headquarters, at 5249 S. Cottage Grove Avenue, doubled as a recording studio for the Valmor blues record label, and would later become an early home of the legendary Chess Records in the late 1940s (then known as Aristocrat).

During the 1930s, Neumann purchased larger warehouse space between S. Indiana Avenue and S. Prairie Avenue at the intersection of Cermak Road. He also had a mailing address at 2541 S. Michigan Ave. from the 1950s into the 1970s, a short stroll from the offices of one of Valmor’s biggest ad partners, Johnson Publishing—of Ebony and Jet fame.

As a Jew of Hungarian descent, Neumann was far from ignorant to the challenges and needs of a disenfranchised minority. And though he eventually moved to the North Side himself (his own funeral was held in Edgewater rather than Bronzeville), he probably deserves some credit not just for keeping Valmor where it started in Chicago, but for providing good job opportunities to black workers across Valmor’s entire national sales network during even some of the roughest years of the Great Depression.

“We are today giving employment to thousands of ambitious men and women throughout the country, but particularly in the South, who are our direct representatives,” Neumann told the Chicago Defender, the city’s leading black newspaper, in 1936. “The standard of high quality found in our products has made them very popular with the public. As a result our agents have been able to establish themselves in their communities and earn good livings. It is interesting to know that many of our agents, who due to economic conditions were thrown out of work, were able to take up our line and provide for themselves and their families in a most satisfactory manner. Many former ministers, mechanics, laborers, office workers, and tradesmen have found freedom from financial worries as well as happiness in their work through the opportunities afforded by us. We are very proud and thankful for the humble part we are playing in helping to pull America out of the depression.”

“We are today giving employment to thousands of ambitious men and women throughout the country, but particularly in the South, who are our direct representatives,” Neumann told the Chicago Defender, the city’s leading black newspaper, in 1936. “The standard of high quality found in our products has made them very popular with the public. As a result our agents have been able to establish themselves in their communities and earn good livings. It is interesting to know that many of our agents, who due to economic conditions were thrown out of work, were able to take up our line and provide for themselves and their families in a most satisfactory manner. Many former ministers, mechanics, laborers, office workers, and tradesmen have found freedom from financial worries as well as happiness in their work through the opportunities afforded by us. We are very proud and thankful for the humble part we are playing in helping to pull America out of the depression.”

Neumann may very well have fancied himself a progressive hero of sorts, but before we can reach a fair assessment of the man and his motivations from a modern perspective, we eventually have to take stock of the Valmor products themselves; what they say about the racial divide in America, and what it means to have profited, indirectly or not, from that divide. Since Neumann compounded the problem by apparently refusing to give his graphic designers their due credit (the work of Dawson and Jackson was only recognized years later), while simultaneously parlaying his Valmor earnings into a massive world-renowned collection of “real art”. . . the story becomes a bit more predictably disappointing and of its time, so to speak.

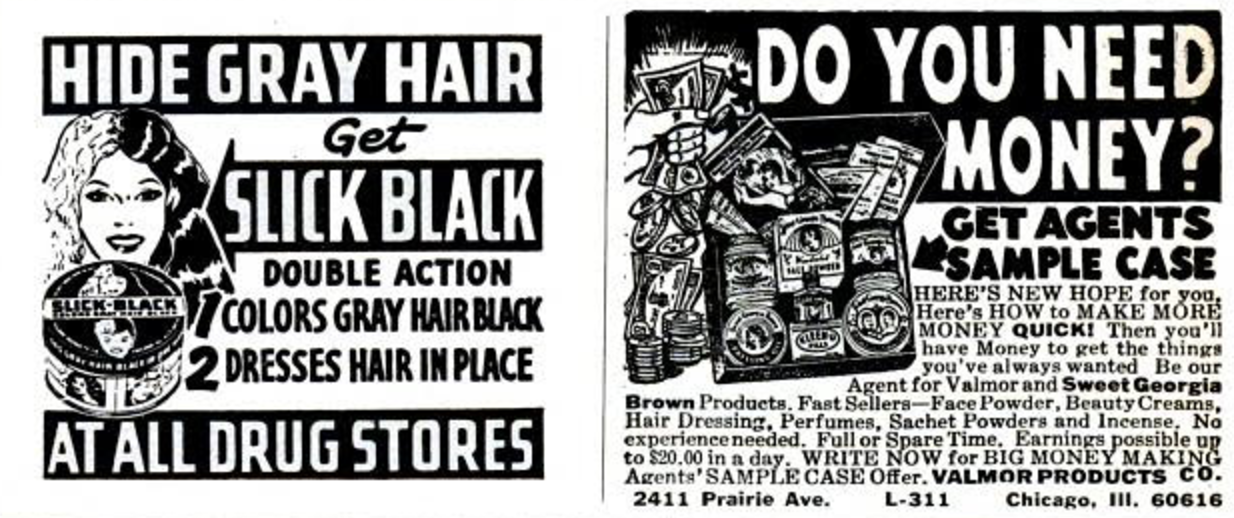

[Left: Original 16×11″ promotional poster for Valmor’s Slick Black hair color, 1940s, also part of our museum collection. Right: Ad from a 1946 Valmor “Dream Book” and view of the Slick Black tin]

II. Style Over Substance

In the years before the Civil Rights movement and the “Black is Beautiful” revolution that grew from it, African-American women were consistently peddled cosmetics with a depressingly transparent motif—hair straighteners, skin lighteners. . . products to make you look more like the standard white ideal of beauty. The societal pressure to achieve this ideal, much like the pressure cast on American women of all shapes, sizes, and backgrounds, was pervasive long before Morton Neumann came along, and it’s hardly been vanquished today. The fact that Valmor failed to move the needle on that problem, then, can’t entirely be held against it. What the company did do, however—thanks to the provocative nature of its label designs—was give a new commercial platform to an unashamedly more romantic and sexualized image of the modern black woman.

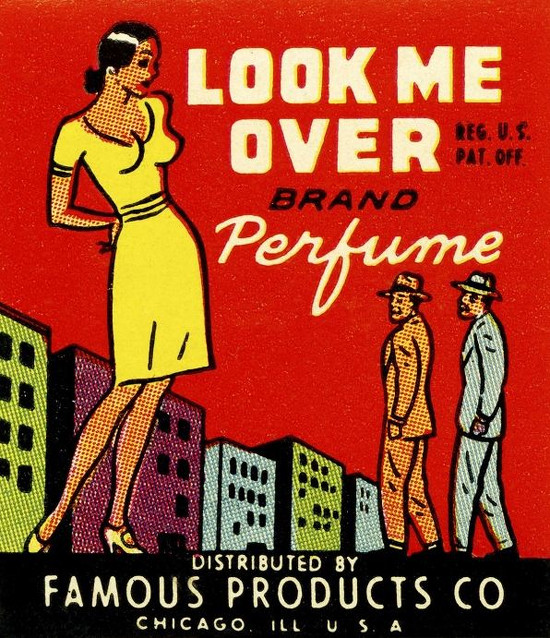

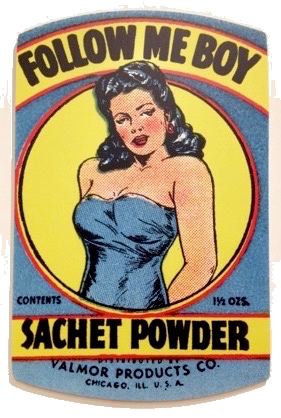

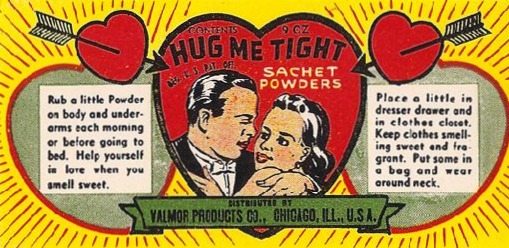

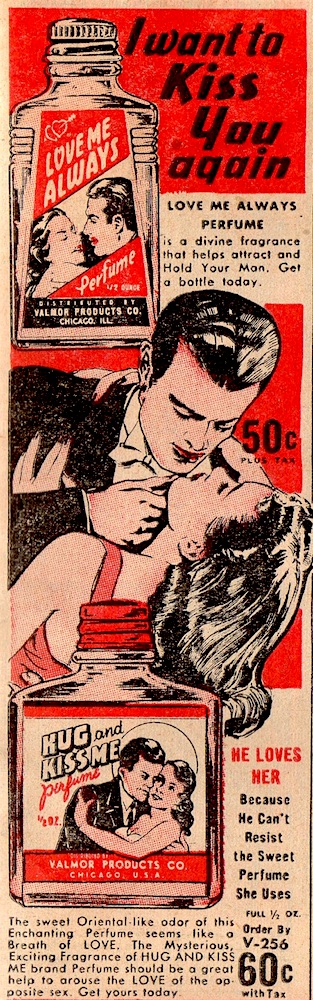

We’ll never know if this design directive came straight from Morton Neumann or from the influence of his early hired artists like Dawson and Jackson, but the pulpy romance-novel artwork—along with flirtatious product names like “Follow Me Boy” sachet powder and “Kiss Me Now” perfume—became calling cards through the entire history of the company. The cosmetic mail-order catalogs, specifically, gave their target clientele very clear cause-and-effect scenes of the passionate moments awaiting them if they used the Valmor product in question.

We’ll never know if this design directive came straight from Morton Neumann or from the influence of his early hired artists like Dawson and Jackson, but the pulpy romance-novel artwork—along with flirtatious product names like “Follow Me Boy” sachet powder and “Kiss Me Now” perfume—became calling cards through the entire history of the company. The cosmetic mail-order catalogs, specifically, gave their target clientele very clear cause-and-effect scenes of the passionate moments awaiting them if they used the Valmor product in question.

“Hello, Beautiful,” a dashing light-skinned man says to a smiling light-skinned woman in a 1946 ad for Sweet Georgia Brown face powder. “Is your complexion dark and sallow?” the smaller text warns. “Here’s the secret for having a LIGHTER, BRIGHTER, more lovely looking skin in just a few seconds. Use Sweet Georgia Brown Face Powder. It is specially made to give tan and dark complexions the Brighter attractive beauty that everybody admires.”

There is nothing subtle about this, but then again, there was nothing subtle about anything when it came to Valmor. To get noticed on a drugstore shelf or in the hands of a door-to-door salesman, Neumann clearly felt the best response was an immediate one. By employing mostly black designers and salesmen (and likely copywriters, as well), he also had the ability to market his concoctions in a style and language more likely to resonate with the intended customers.

For a chemist, Neumann sure seemed to have an innate knack for mass-marketing, from brand identity (and diversification) to the obligatory “art of the deal.” As early as 1927, he’d published his own guide book for the salesmen of the Valmor Health Products Company (as it was originally known). Titled “Pathway to Profit,” it laid a groundwork for enticing potential customers not only by singing the praises of the product itself, but by offering incentives for a purchase—hardly a new concept, but useful nonetheless.

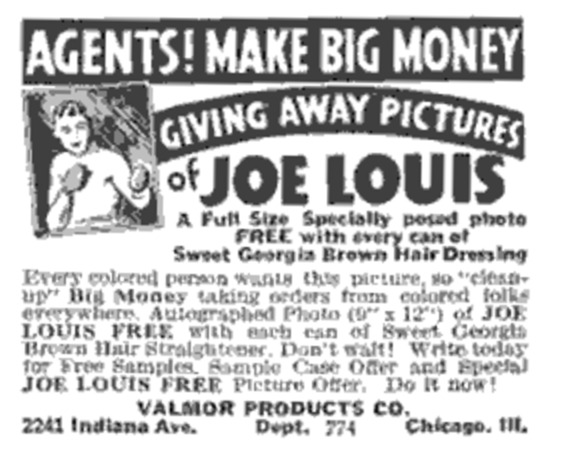

In the 1930s, for example, Valmor agents went door-to-door giving away free photographs of the most famous black man in America, boxer Joe Louis, with every purchase of a can of “Sweet Georgia Brown” Hair Dressing. The sales agents themselves were recruited from ads, mostly in black publications, that essentially guaranteed big profits from getting involved in this campaign.

“Every colored person wants this picture,” one ad read, “so clean up Big Money taking orders from colored folks everywhere. . . . Don’t wait! Write today for Free Samples. Sample Case Offer and Special JOE LOUIS FREE Picture Offer. Do it now!”

Joe Louis would eventually start selling his own officially licensed Chicago-made pomade under the banner of the “Joe Louis Products Co.,” and any prior arrangement with Valmor or Morton Neumann seems dubious at best. Nonetheless, the tactic was effective.

Since many African-Americans in Chicago and other northern cities were Southern transplants from the Great Migration, much of the Valmor marketing harked back to old Southern traditions, spiritualism, and hoodoo mysticism, as well. The idea was to push a supposedly progressive 20th century aesthetic while still tugging at older, baked-in cultural touchstones and senses of black identity.

By no coincidence, Valmor’s first and most significant graphic artist, Charles C. Dawson, was one of those Southern transplants himself, born in Brunswick, Georgia, in 1889. And while the artwork he created for the company might look like white-washing by today’s standards, he was operating light years ahead of his time in most respects.

III. Dawson’s Creed

None of Charles Dawson’s art ever hung in any of the esteemed galleries of the Morton Neumann Family Collection, but he probably played a bigger role in creating Neumann’s fortune than Pablo Picasso ever did.

There is no record of exactly how or when Dawson came to work with Valmor—largely because Neumann wouldn’t let his artists sign their work—but it’s likely that he caught on with the firm in the early 1930s, when the Depression made such a steady gig highly appealing. Morton Neumann’s artistically-minded wife Rose is also sometimes credited with influencing Valmor’s packaging renaissance, and it’s certainly possible she played a role in seeking out Dawson, whose reputation was already well established.

If anything, Dawson was probably overqualified for the job. A graduate of Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee Institute, he had worked as a Pullman porter for years to pay his way to a degree from the School at the Art Institute of Chicago, where he excelled as a founding member of Chicago’s first black artists collective (the Arts and Letter Society). When World War I broke out, Dawson served in France as a lieutenant with the Buffalo Soldiers. And when he came home, he put his artistic gifts to work as an advertising illustrator and an organizer of several black artist exhibitions—including the first ever held at a major American museum (1927’s Negro In Art Week at the Art Institute).

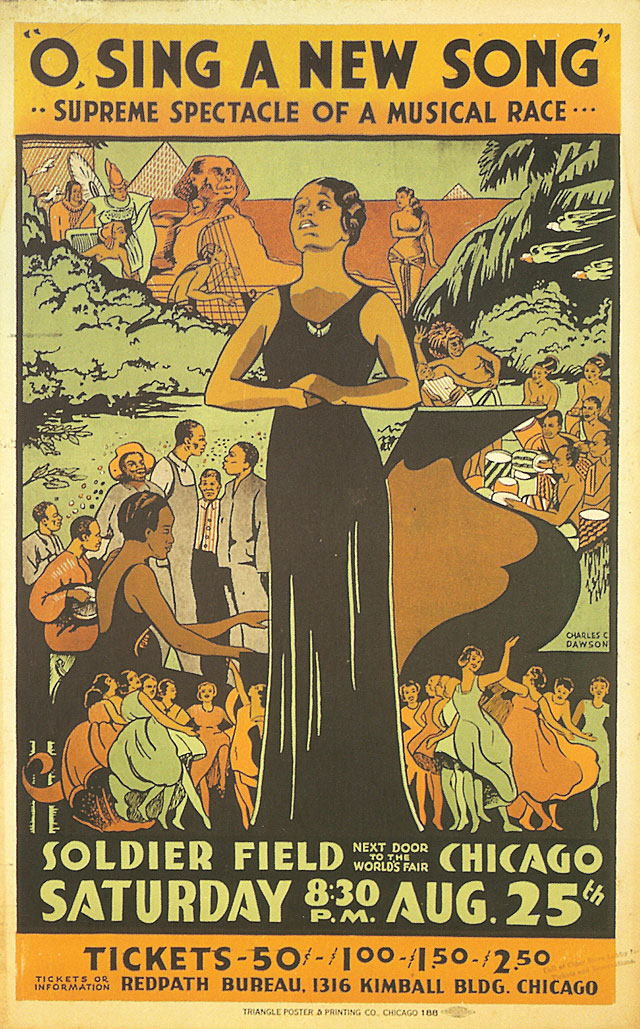

According to the American Institute of Graphic Arts, Dawson’s early years with Valmor coincided with him becoming “the only black artist to have a substantial role in the 1933–1934 Century of Progress Fair,” for which he produced “a mural illustrating the Great Migration for the National Urban League’s display in the Hall of Social Science . . . and a poster for the Pageant of Negro Music, ‘O, Sing A New Song,’ which took place at Soldier Field.”

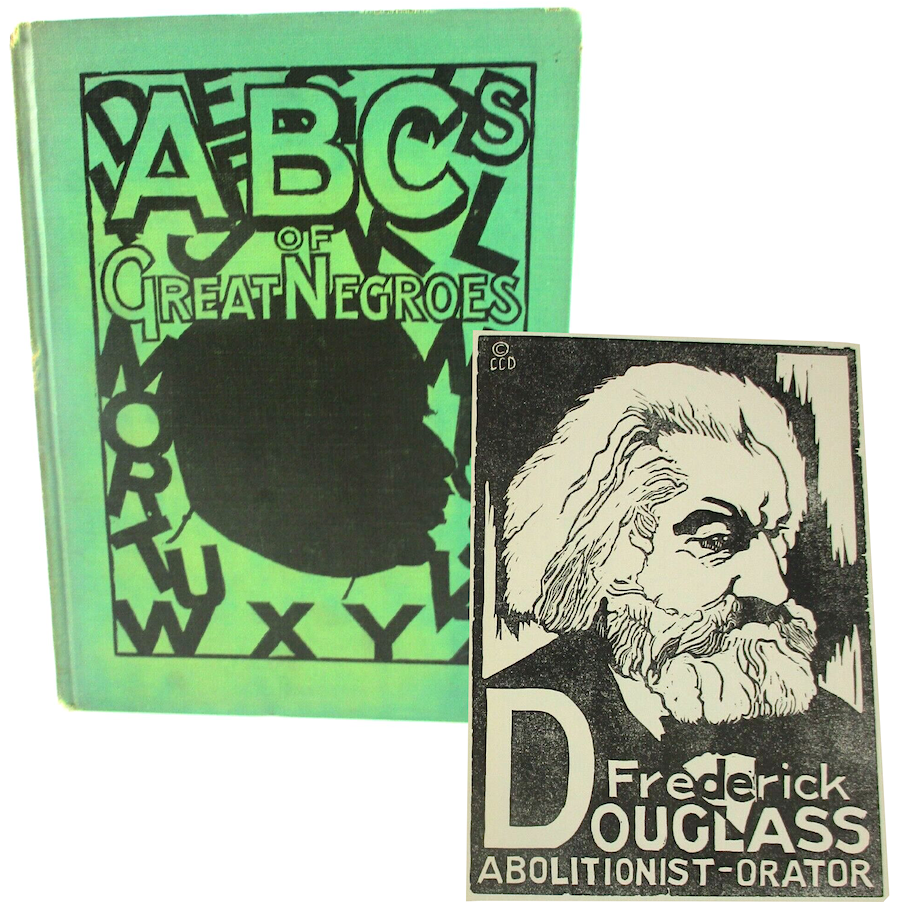

Dawson also published an educational art book for children in 1934—ABC’s of Great Negroes—featuring original portraits of great black men and women from history.

Though he might have been caught up in some of the cultural assimilation trends of the era—a survival requirement for some black professionals—Dawson was far from an apologist for blackness or someone running away from his heritage. His designs for Valmor—a form of pop art way ahead of Warhol and Lichtenstein—used sex to sell mainstream products in a way rarely seen before, with characters of ambiguous race, if not overtly black or Latino, and women who were just as pleased to seduce a man as pine for one.

Though he might have been caught up in some of the cultural assimilation trends of the era—a survival requirement for some black professionals—Dawson was far from an apologist for blackness or someone running away from his heritage. His designs for Valmor—a form of pop art way ahead of Warhol and Lichtenstein—used sex to sell mainstream products in a way rarely seen before, with characters of ambiguous race, if not overtly black or Latino, and women who were just as pleased to seduce a man as pine for one.

“Valmor products hold an undeniable place in the history of black beauty products,” says Patrice Grell Yursik, the creator of Afrobella.com, a popular blog focused on African-American cosmetic trends. “The packaging by Charles C. Dawson spoke directly to the aesthetic of the time. There absolutely is a light-skinned ideal in his design, but the fact the products existed in a time of need and offered a glimpse of black beauty in a Eurocentric landscape makes this far from a shameful chapter. I believe the products and positioning of Valmor ultimately helped to inspire future generations of beauty entrepreneurs to create even more products for an always-underserved market, celebrating more accurate reflections of diverse beauty over time.”

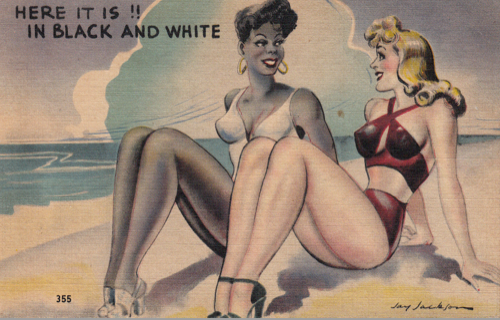

Later Valmor artists, like the noted pin-up and comic illustrator Jay Jackson, carried on Dawson’s aesthetic through World War II and on into the 1950s. By that point, though, Morton and Rose Neumann had shifted their attention more to the art hanging on their own walls.

[A 1940s postcard design, quite risqué for its time, by African-American artist Jay Jackson, a successor to Charles Dawson at Valmor]

IV. Neumann’s Own

When Morton G. Neumann died in 1985 at the age of 87, the Chicago Tribune devoted a hefty 548 words to his obituary, but only three of them—“local cosmetics manufacturer”—made any reference to the business he’d run continuously since 1926 (the word Valmor wasn’t mentioned at all). Instead, like many other publications across the country, the Tribune remembered Neumann almost entirely for the things he’d accumulated—“one of the finest collections of 20th century art in the world.”

In retrospect, it seems not only noteworthy, but slap-in-the-face fascinating to learn that such a revered figure in the high-art community had purchased many of his most valuable pieces on money earned from selling hair-straighteners and skin-lighteners to black people. Even if we wanted to simplify Neumann into some sort of villainous exploitative art snob, though, it wouldn’t really do this odd character justice.

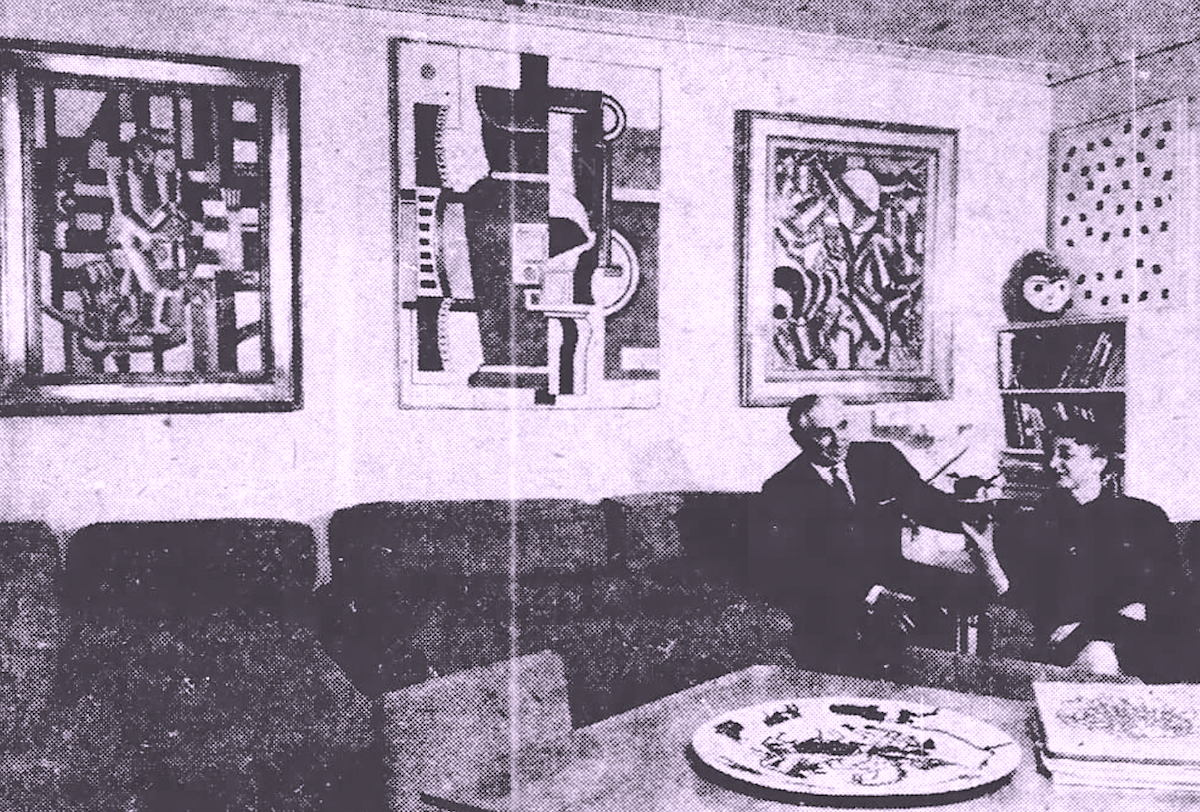

[picture: Morton and Rose, circa 1940s]

According to a 2005 piece in the New Yorker, for example (which also made zero reference to Valmor), “Morton Neumann was dismissed early on by the art world as a coarse and gullible enthusiast.”

This is backed up by the aforementioned obituary in the Tribune, which cites one longtime friend as saying, “Morton isn’t a collector. He’s a naif.”

“There are no pearls of wisdom from Morton Neumann,” said another. “His talent is visual. Everything is in that great eye.”

According to the Tribune, Morton “did not start to develop his eye until 1948,” when he and Rose took a trip to Paris and became enamored with the idea of owning pieces of visual profundity. The couple “returned home with paintings by Bernard Buffet, Marie Laurencin, Maurice Utrillo and Georges Rouault. They began the collection.”

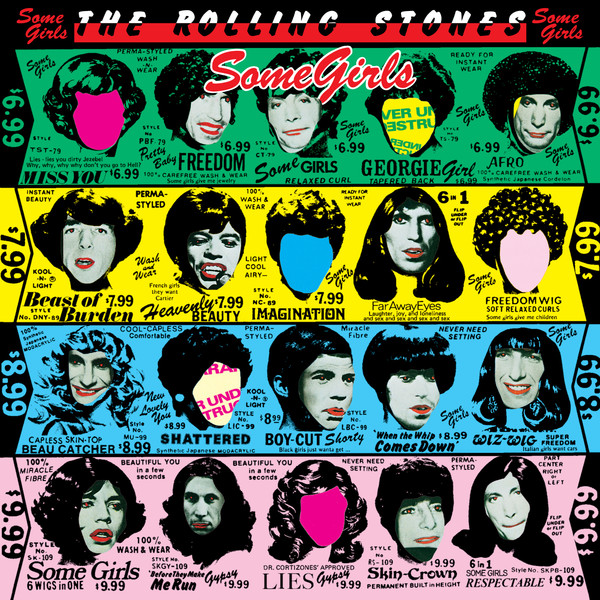

To suggest that Morton and Rose randomly “grew their eyes” in 1948, however, only further buries the significance of the Valmor Products Company in either showcasing or helping to inspire their art appreciation at an earlier age. At some point, Morton and Rose had to recognize the talent of Charles Dawson and Jay Jackson in order to hire them in the first place. And though they somehow drew a line between that commercial art and the quite similar works of Warhol and Lichtenstein (both of whom were part of the Neumann Family Collection), Valmor’s influence was still spilling into popular culture in its own way. Case in point, the album cover of the Rolling Stones’ 1978 record, Some Girls.

[Incidentally, rather than appreciating the hat-tip, Valmor sued the Rolling Stones and album designer Peter Corriston for using an old Valmor ad as the template for this design]

[Incidentally, rather than appreciating the hat-tip, Valmor sued the Rolling Stones and album designer Peter Corriston for using an old Valmor ad as the template for this design]

The disconnect between the art-loving Neumanns and the Valmor art itself is perplexing. Part of what made the Neumann Family Collection so in-demand and celebrated by trendy art mavens was its evolution over time. Rather than settling into certain preferred styles, Morton and his son Hubert (the boys get most of the credit, of course) always kept an open mind, eagerly seeking out the new and exciting, and setting a goal of seeing the world “as young people do.” Maybe they were just too close to their own source material.

In any case, the idea of the permanently youthful, curious, and adventurous Morton Neumann paints a fine picture (pun intended), but at least one first-person account of a meeting with the man creates a very different image of a curmudgeonly old codger clinging to a dying business.

[Morton and Rose Neumann showing off the Picasso collection in their Chicago home, 1955]

V. Never Meet Your Heroes

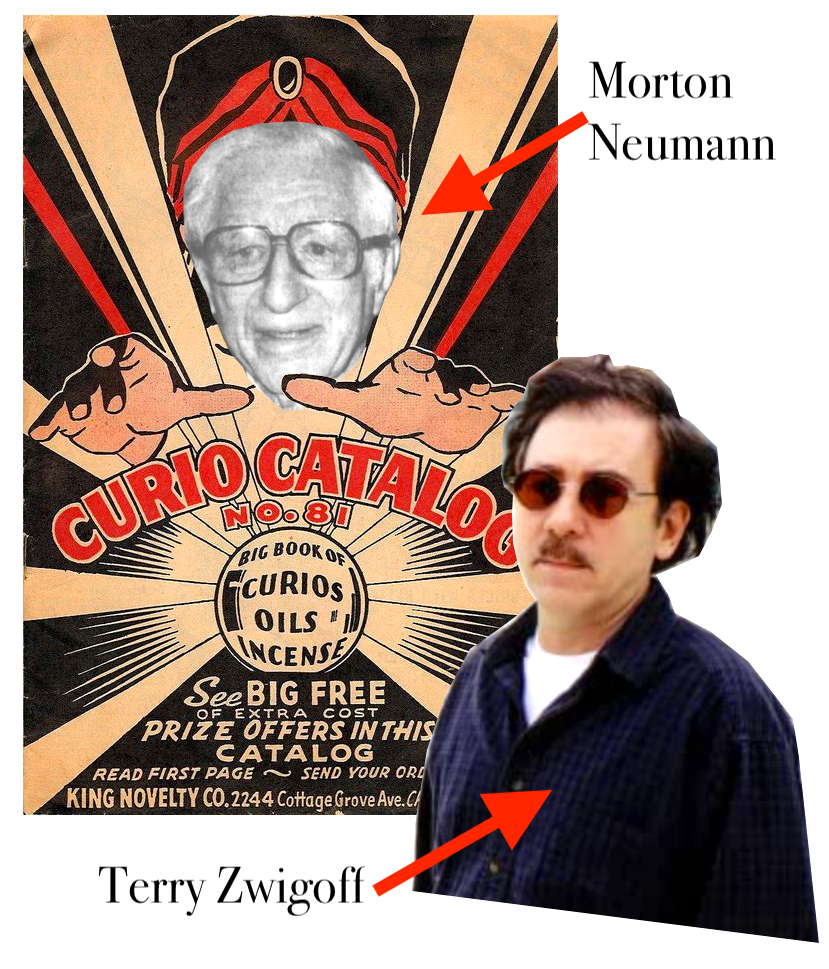

Back in 1974, screenwriter and Chicago native Terry Zwigoff (of Ghost World and Bad Santa fame) was just a 25 year-old kid with a budding passion for collecting the old hand-drawn, four-color Valmor labels of yore. When he learned that the company was still in business (to his surprise), he decided to pay the Valmor offices a visit. Zwigoff recounted the strange events that followed in a 1993 article for Weirdo magazine.

“By the time I met [Neumann] in 1974, Valmor had become a two-person operation. Morton and his wife (the receptionist) actually filled all the mail orders themselves. Morton was so eccentric as to personally deliver orders to local stores. One old woman who ran a tiny candle shop in one of the most dangerous neighborhoods in Chicago’s South Side told me that he’d drive up and double park his Rolls Royce when he delivered her monthly order for $10 worth of Valmor Wick Oil.

“By the time I met [Neumann] in 1974, Valmor had become a two-person operation. Morton and his wife (the receptionist) actually filled all the mail orders themselves. Morton was so eccentric as to personally deliver orders to local stores. One old woman who ran a tiny candle shop in one of the most dangerous neighborhoods in Chicago’s South Side told me that he’d drive up and double park his Rolls Royce when he delivered her monthly order for $10 worth of Valmor Wick Oil.

. . . I called the [Valmor] number and started to question the bad tempered receptionist on the phone about old bottles and she curtly announced they were ‘wholesale only’ and hung up. The next day I drove down to the warehouse and entered a small office in the front where I confronted the same old nasty woman I’d spoken to on the phone. No one else was around. I told Old Nasty I was very interested in their old products and labels, had come all the way from San Francisco, and wanted to buy some. She didn’t want to hear about ‘old’—‘Wholesale only, we got nothing old. . . waste our time. . . Get out. . . get out before I call the police!’ I started in on her again about how I really admired the craftsmanship of the old art work and design and would pay a good price if they’d let me look around the warehouse for this older stuff. In the middle of my begging and her shrieking, an old guy about 80 appeared out of the recesses of the seemingly deserted back warehouse. Morton Newmann [sic], complete with cigar, reminded me of an extremely cranky George Burns.

‘What’s the problem here?’ he snapped suspiciously.

‘Well sir, you see, that is… I like the old…and…’ He seemed to soften a bit when he figured out I was sincerely interested in the company and the products and the artists who drew the old packaging. Although he claimed to know little about the history of the company or the artists, he did send some old black guy, who had been sweeping the floor, into the warehouse with instructions to bring out a cart full of old bottles and cans to sell me for $1.00 each. He acquiesced a bit more and told me that he thought it was some gypsy guy who drew most of the early artwork but he was dead, and no, there was no original art work left around.”

It’s hard to say how much Zwigoff dramatized this story, or how accurate his memory was, or how sharp Morton Neumann’s own mind was by 1974 (when he was 76). But if the basic account is true, it’s a brutally sad one. For one thing, Rose Neumann—Morton’s muse who died in 1998—is the ill-mannered receptionist depicted here, totally uninterested in even discussing Valmor’s history. Far worse, though, is Morton’s vague and false description of Valmor’s early artist. Sure, he didn’t take credit for the art himself (many sources actually credited Neumann with designing Valmor packages for years), but he did suggest an anonymous and long-since-dead “gypsy” had done the work. In truth, Charles C. Dawson was still very much alive in 1974. After working as the curator of the Museum of Negro Art and Culture and the George Washington Carver Museum in the late 1940s, he’d retired to New Hope, Pennsylvania, where he still made his home.

Even by 1993, when Zwigoff wrote his article, he still hadn’t learned the truth. Dawson, meanwhile, had died in 1981, never getting his deserved recognition for the Valmor catalog.

Around the time of Morton Neumann’s death in the mid 1980s, the Valmor Products Company finally came to an end, as well, purchased by New York’s R.H. Cosmetic Corp. Terry Zwigoff, who’d been sending letters to the Valmor offices still in hopes of finding original art hidden away somewhere, instead received a reply in 1985 from R.H. president Richard Solomon.

“He said my letter had been forwarded to him,” Zwigoff wrote, “as he’d just bought out the Valmor Co. And yes, there were acres of old products, original art, even the original printing presses and old plates. Too bad he threw it all out. He only bought the company because he wanted the rights to several hair pomades that were still big sellers. If only he’d known someone was interested in it.”

Zwigoff’s pain, perhaps, can now be shared by all of us.

For a deeper look at Valmor artwork at its creative peak, click the image below to flip through the company’s complete Catalog No. 22 from 1936.

Valmor-Catalog

[Valmor ran ads like these in Ebony magazine, virtually unchanged, from the late 1960s into the early 1980s]

[Valmor ran ads like these in Ebony magazine, virtually unchanged, from the late 1960s into the early 1980s]

Sources:

Made In Chicago Museum Interview: Patrice Grell Yursik, Afrobella.com

“The Valmor Story,” by Terry Zwigoff, Weirdo No. 18, 1993

“Quarters Grow Too Small, So Company Moves” – Chicago Defender, March 28, 1936

“Love For Sale” – John Foster, DesignObserver.com

“Charles C. Dawson: Artist and Designer During the 1920s and 30s” – Jae Jones, BlackThen.com

“Charles Dawson” by Daniel Schulman, AIGA.org

“Throwback. Colorism and Mysticism in the Graphic Illustrations of Valmor Products.” – SuperSelected.com

Spiritual Merchants: Religion, Magic and Commerce, by Carolyn Morrow Long, 2001

“Valmor and Sweet Georgia Brown Dream Book” – RepositoryofUsefulKnowledge.com

“The Collector Who is Breaking a Thousand Curators’ Hearts” – New York Times, Dec. 9, 1997

“The Valmor Products Company: Jewish Dealings in Race, Magic, and Alterity” – Golem Theory

“Morton Neumann, City’s Patron of Art” – Chicago Tribune, April 10, 1985

“Gallery Losing Loaned Art” – Washington Post, October 6, 1998

“Jay Jackson: African American Cartoonist and Illustrator” by Jim Linderman, ArtSlant.com

“Lucky Brown Cosmetics” – LuckyMojo.com

“This 90-Year-Old Bronzeville Company Told a Love Story in Labels” by Kelly Bauer, DNAInfo.com

“Salesman: Days and Nights in Leo Koenig’s Gallery” – Nick Paumgarten, New Yorker, Oct 17, 2005

“Love for Sale: The Graphic Art of Valmor Products” – CityofChicago.org

Archived Reader Comments:

“I just bought 13 different cosmetoc and product labels at an antique store today. They are original.labels. im not sure if they were removed from packaging at some point or if they were never put on packaging but they are gorgeous. I loved the art of them and thats why i bought them but didnt know what they were until i read this article. ” —Thespoena McLaughlin, 2019

“Excellent article. We’re building a small collection of Dawson’s and Jackson’s work at Letterform Archive and your context was extremely helpful. We’ll be referring our guests to it frequently.” —Stephen Coles, 2019

“I have a John The Conqueror Great Herb Compound bottle from the Famous Products Co. because I am a huge Willie Dixon and Muddy Waters fan.” C. Just, 2019

“Found this page today after reading an article about Morton Neumann’s son and his art collection in the 2018 Art Issue of W magazine with Cardi B on the cover, yet only a brief mention of Valmor. Very appreciated. ” —M, 2019

Who owns the copyrights to the old artwork: Dawson’s family or the new owners. Thanks.

Amazing article! I read about Valmor about 20 years ago, and recently a neighbor of mine found some Valmor paperwork objects in their old house’s attic, so I decided to look it up again.

Thanks!

It should be from 1940 and I’d love to see it

I found in papers of my grandfather a Valmor Hair Styles Catalog No. 24 but there is no date on it, can anyone help me date the catalog?

In 1995 I started working on a book titled Spiritual Merchants: Religion, Magic, and Commerce, which was published by University of Tennessee Press in 2001. It discusses the African-based traditions of hoodoo and conjure and the Voudou religion of New Orleans and how (mostly) white entrepreneurs appropriated them for the manufacture of “spiritual products.” The book includes a section on the Valmor Company. Terry Zwigoff’s article was one of my sources of information.

We have a Madam Jones Powder cardboard container with the powder still in it. It’s not unopened, but it’s in nice shape. Do you know how to reach these museums to see if any of them would be interested?