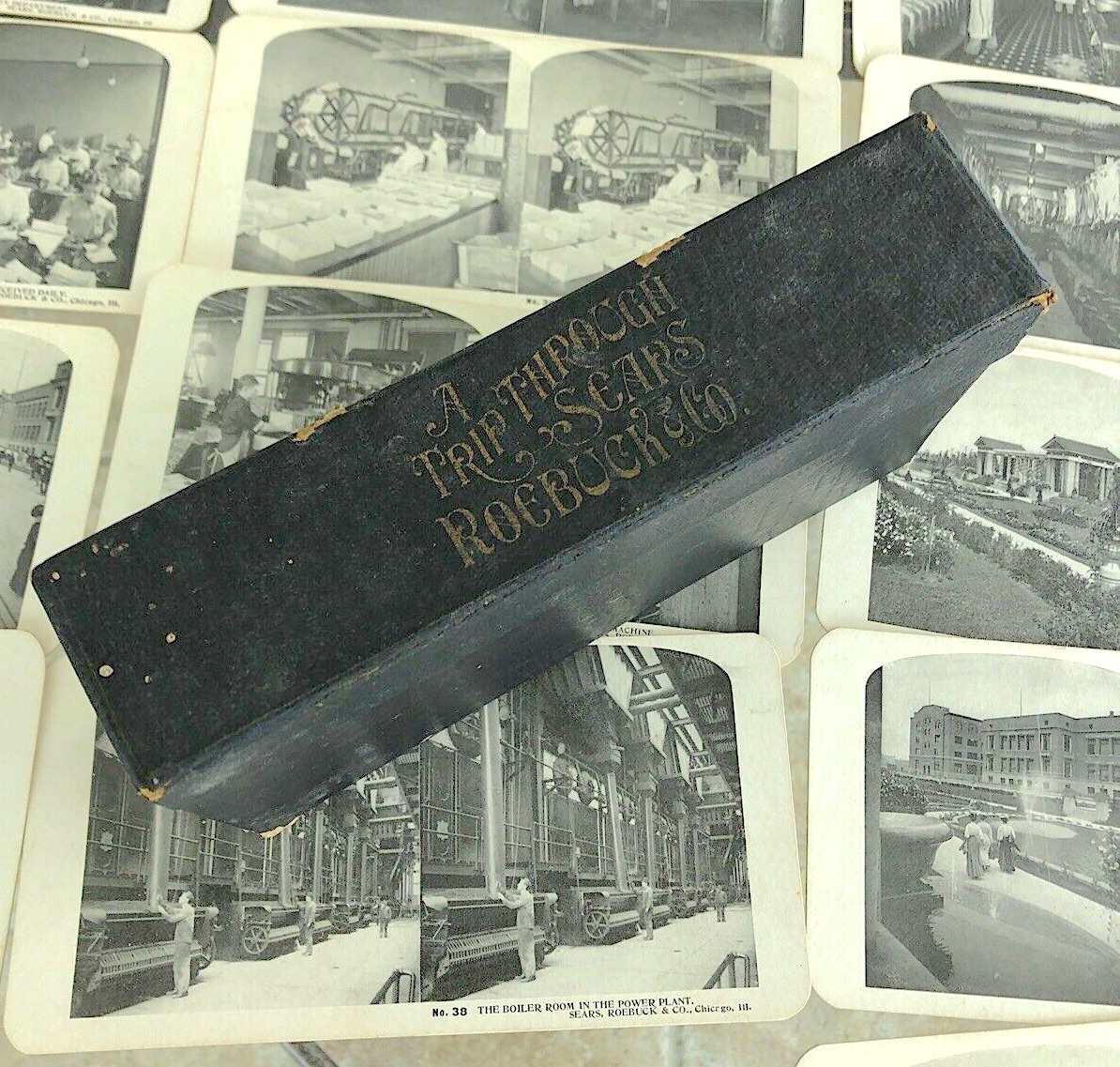

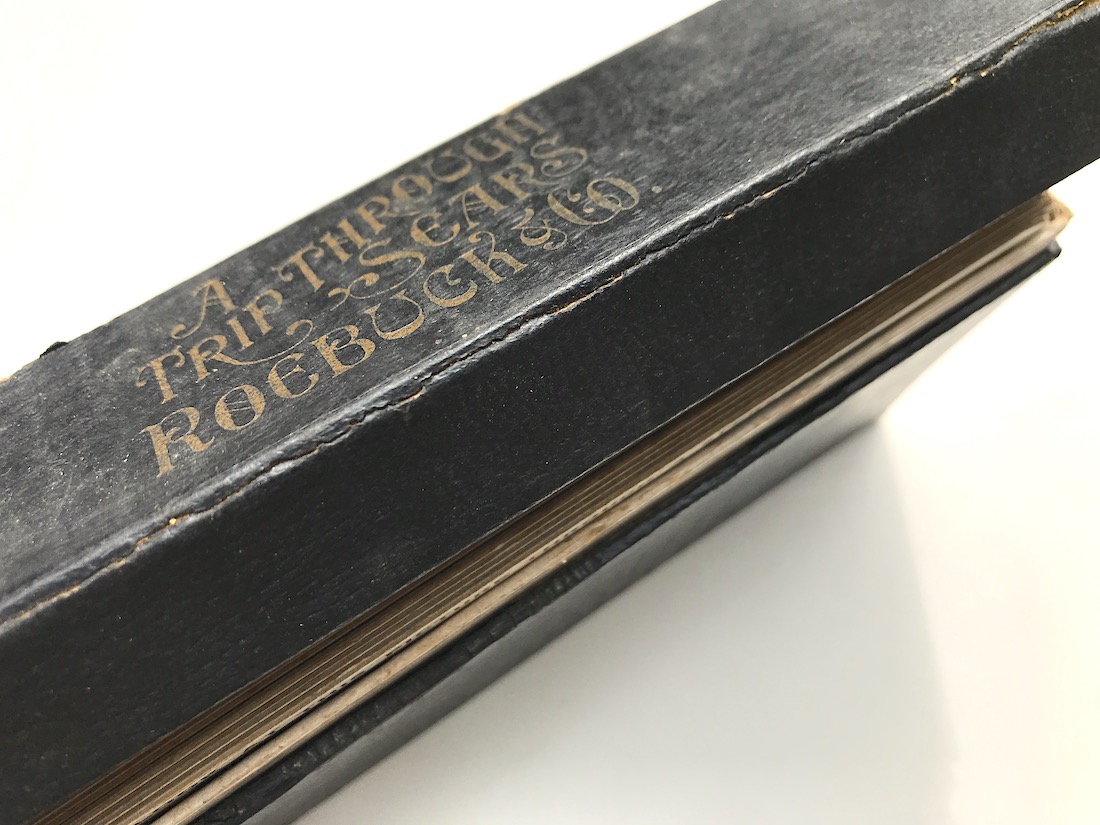

Museum Artifact: “A Trip Through Sears Roebuck & Co.” – Set of 50 Stereoview Photo Cards, c. 1908

Made By: Sears, Roebuck & Company, 925 S. Homan Avenue, Chicago, IL [Homan Square]

“Which company do you think has the most stores, the most customers, the most sales, the most profits – and at the same time is the most loved, the most far-flung, the most legendary, the most American institution ever to charge two bucks for a bottle of snake oil? The answer, of course, is Sears Roebuck.” —Cosmopolitan Magazine

The decline of the Sears name in the 21st century—and we’re not just talking about the blasphemous use of the phrase “Willis Tower”—has sadly undercut the company’s overall standing in American history, turning it more into a cautionary tale rather than an aspirational example. Having once been the country’s No. 1 mail-order business AND its top brick-and-mortar retail chain, Sears, Roebuck & Co. was basically Amazon and Wal-Mart rolled into one, but with products predominantly sourced from inside the U.S., providing thousands of jobs and sustaining hundreds of smaller manufacturing businesses that came to rely on its national sales and distribution machine.

The decline of the Sears name in the 21st century—and we’re not just talking about the blasphemous use of the phrase “Willis Tower”—has sadly undercut the company’s overall standing in American history, turning it more into a cautionary tale rather than an aspirational example. Having once been the country’s No. 1 mail-order business AND its top brick-and-mortar retail chain, Sears, Roebuck & Co. was basically Amazon and Wal-Mart rolled into one, but with products predominantly sourced from inside the U.S., providing thousands of jobs and sustaining hundreds of smaller manufacturing businesses that came to rely on its national sales and distribution machine.

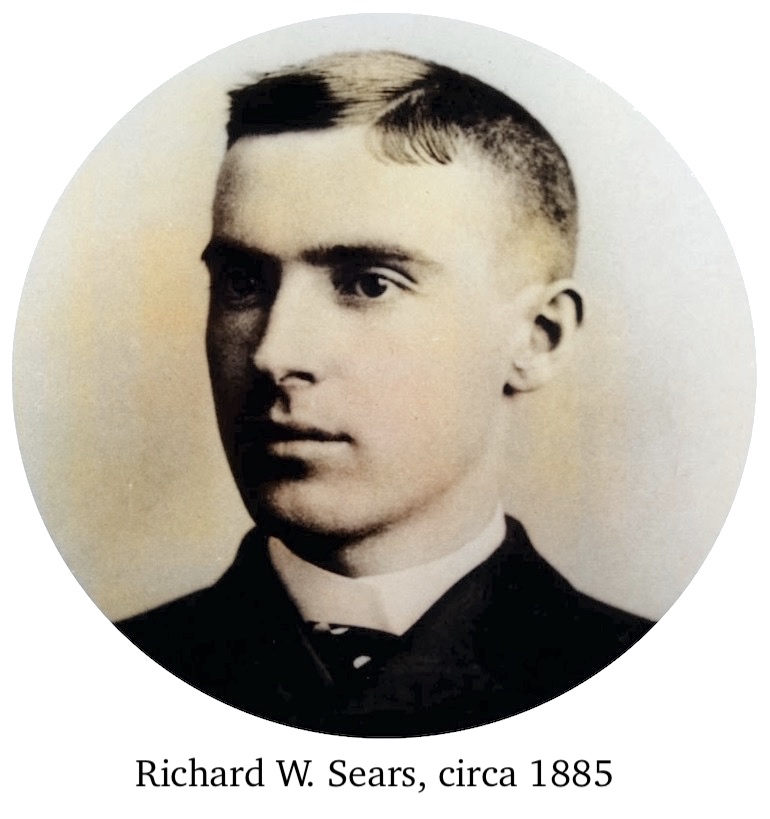

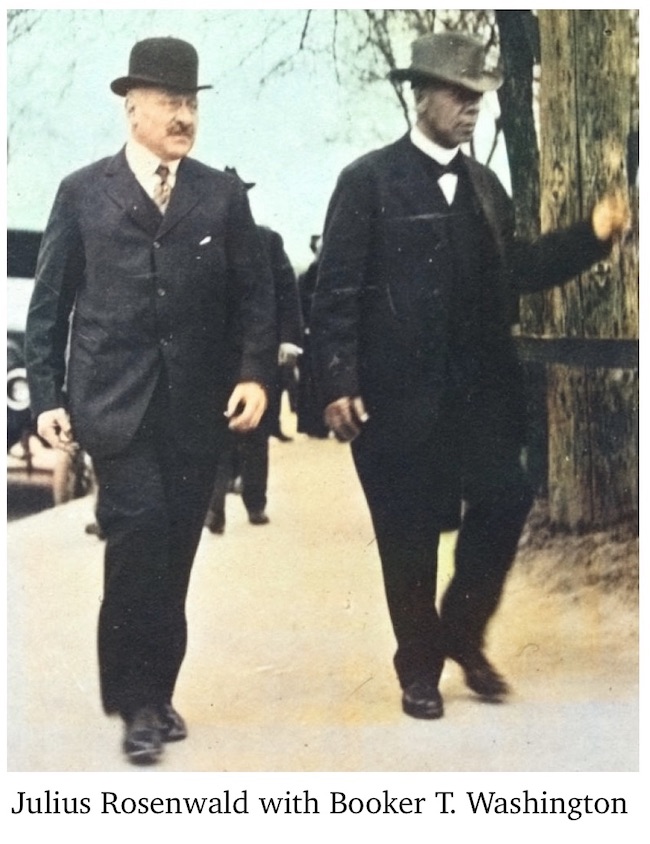

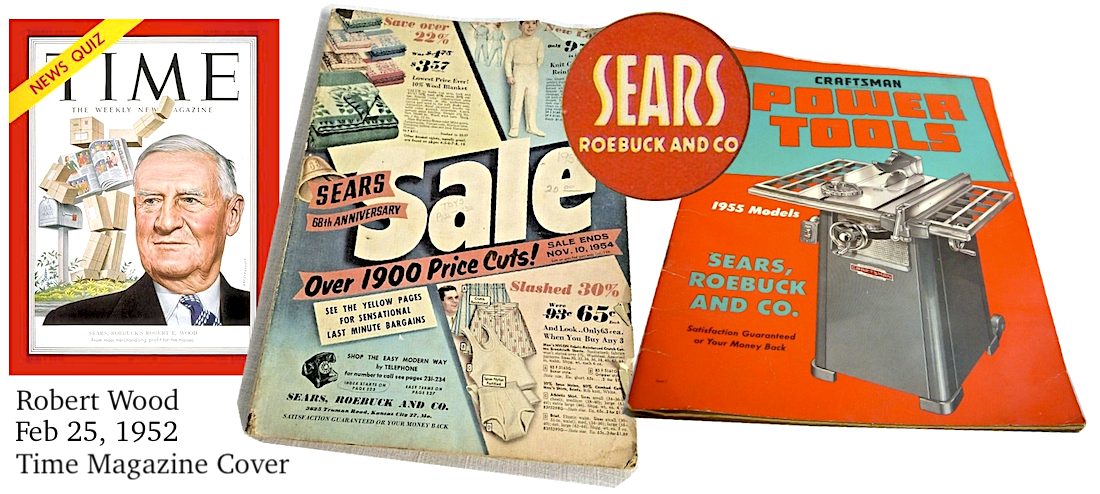

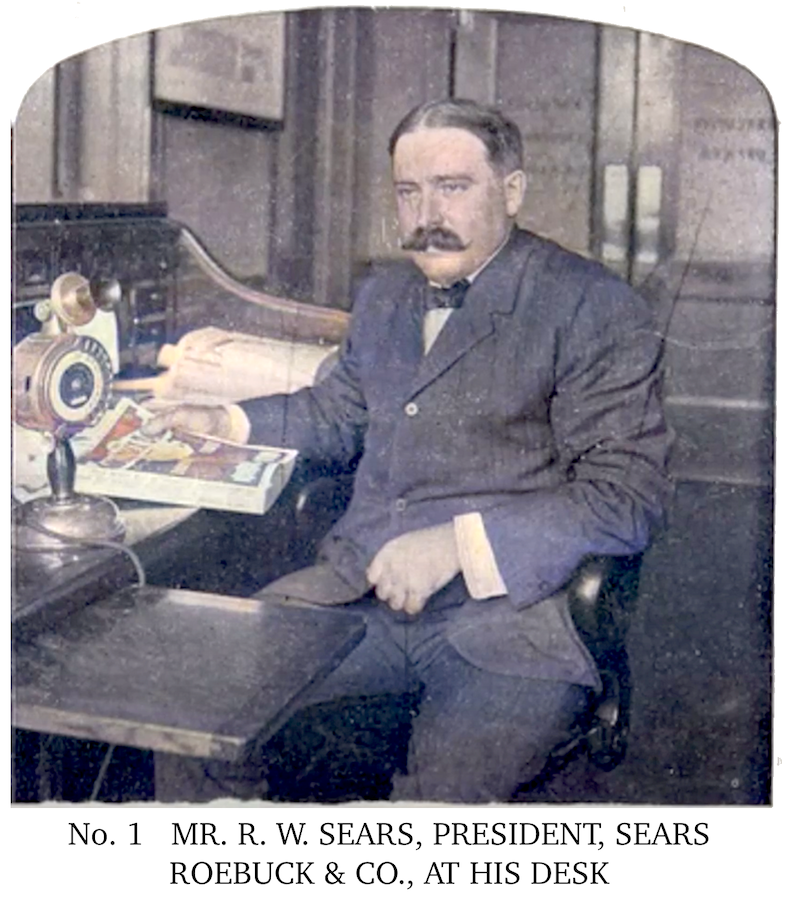

Richard Sears, the original ringmaster of the operation, is sometimes credited with helping to invent the modern retail economy itself. His successors, Julius Rosenwald and later Robert E. Wood, probably did quite a bit more in managing to refine Sears’s unwieldy juggernaut into a manageable business model. Predictably, fair labor practices were often the first things to get sacrificed in the process, but there were also notable efforts—particularly from Rosenwald—to use the company’s power for more honorable causes.

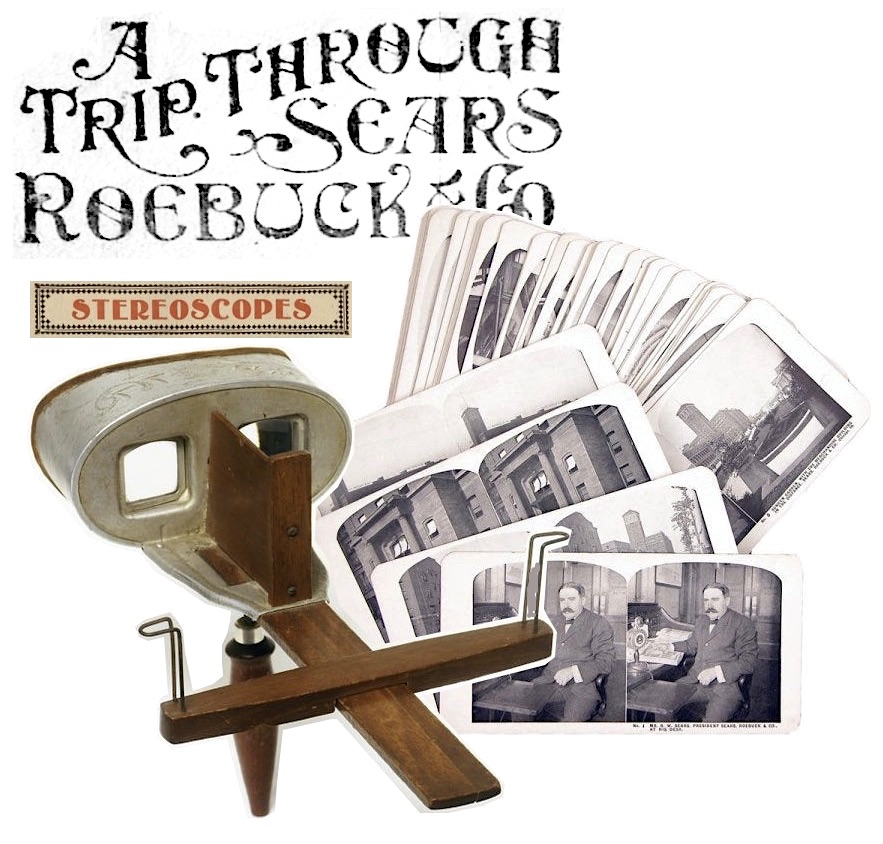

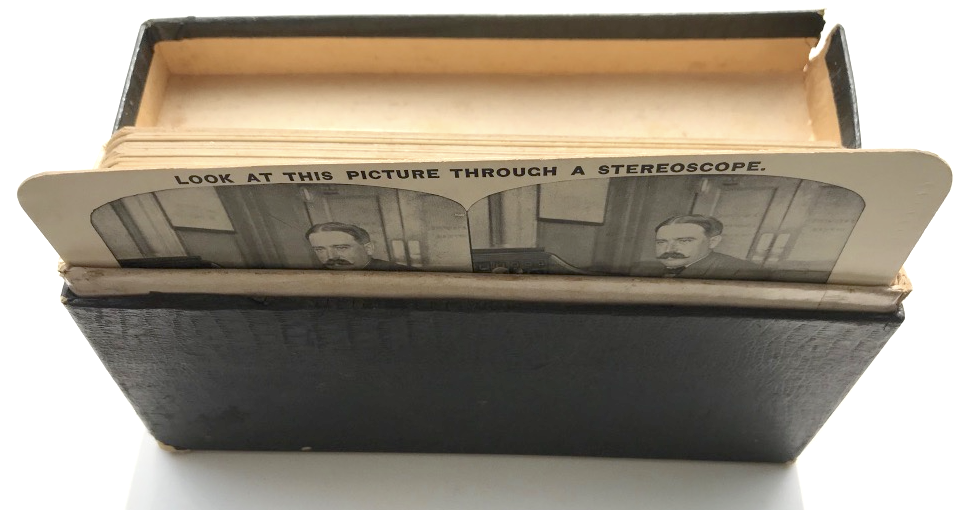

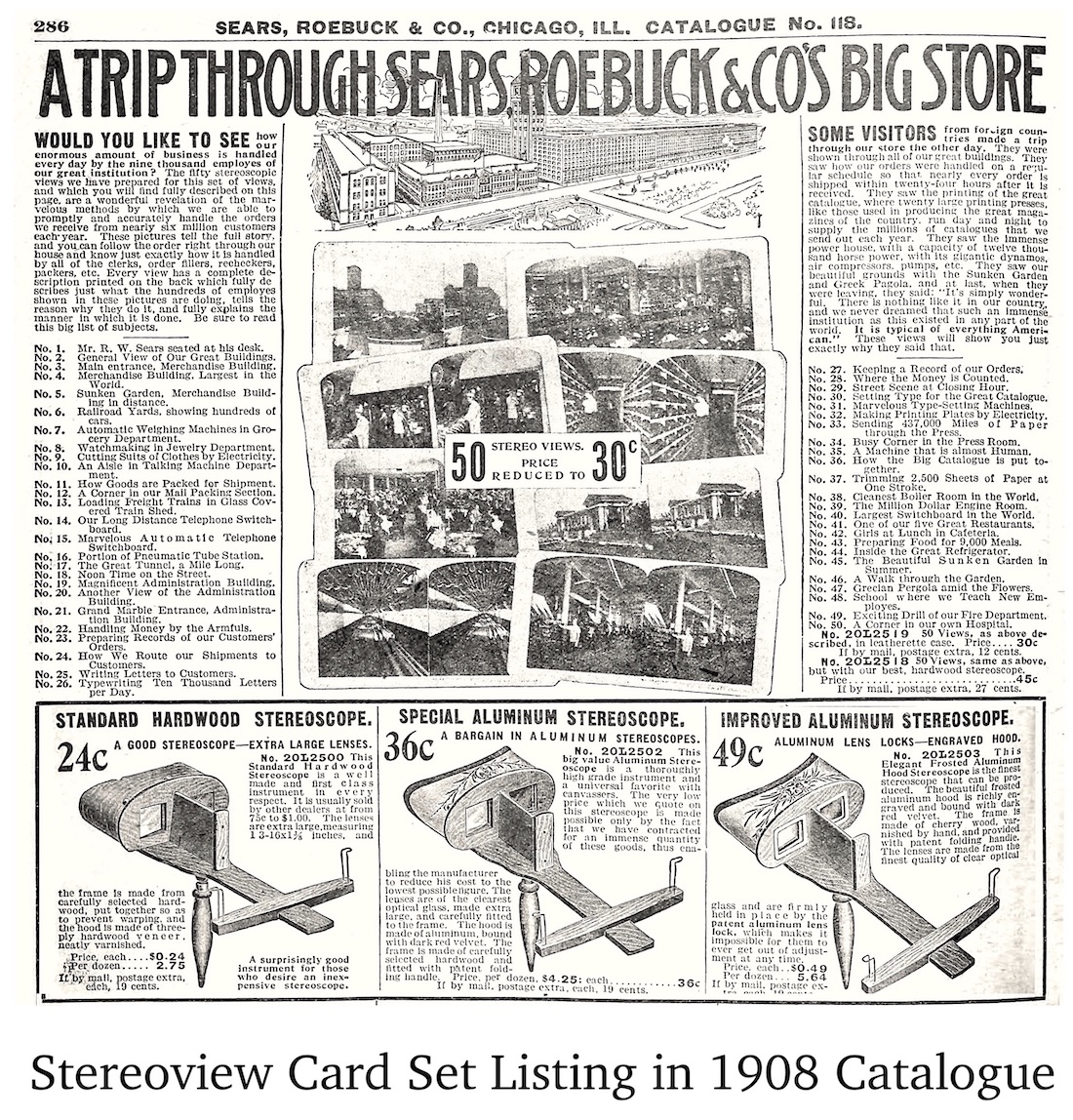

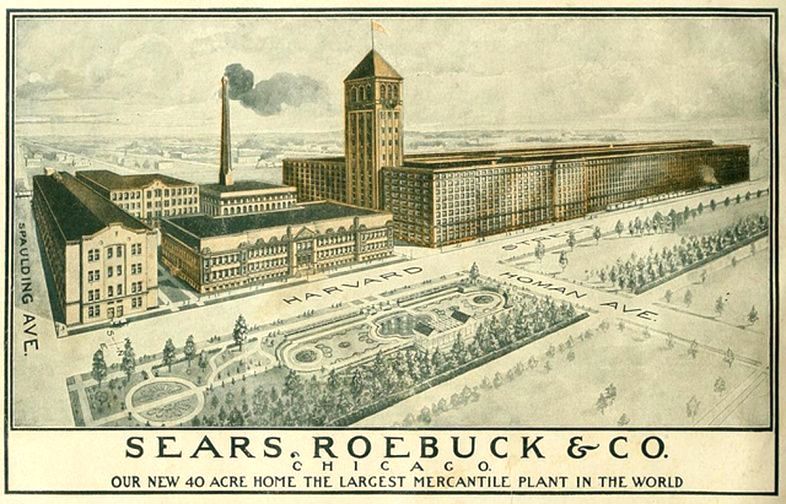

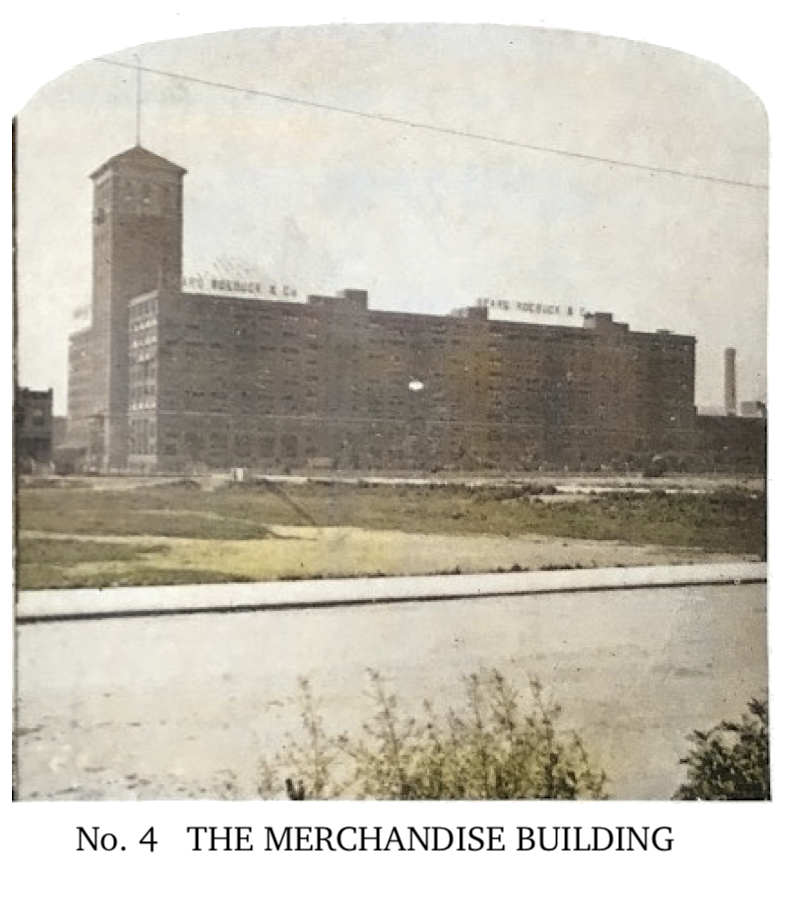

Known to generations as the “World’s Largest Store,” it’s sometimes forgotten that Sears-Roebuck was a large-scale manufacturer, too, making it a perfectly suitable entry in the Made In Chicago Museum. The “artifact” in our collection—a promotional set of 50 Stereoview Photo Cards from 1908—offers vivid evidence of this part of the Sears story, depicting the various bustling departments inside the company’s enormous new 40-acre factory campus in North Lawndale, which would later employ upwards of 20,000 people.

“A Trip Through Sears, Roebuck & Co.” 1908, Colorized Stereoview Card Images #1-16 [Click Any to Enlarge]

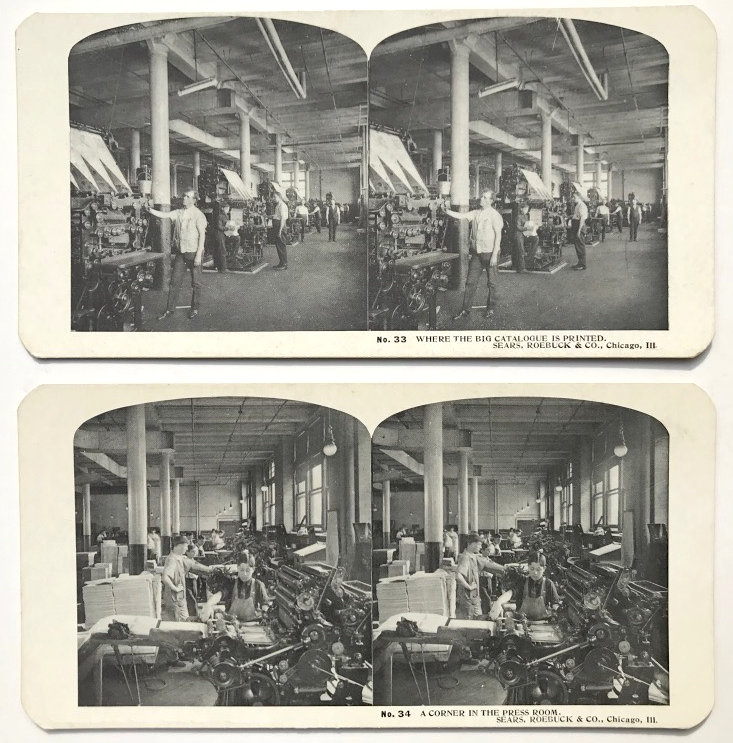

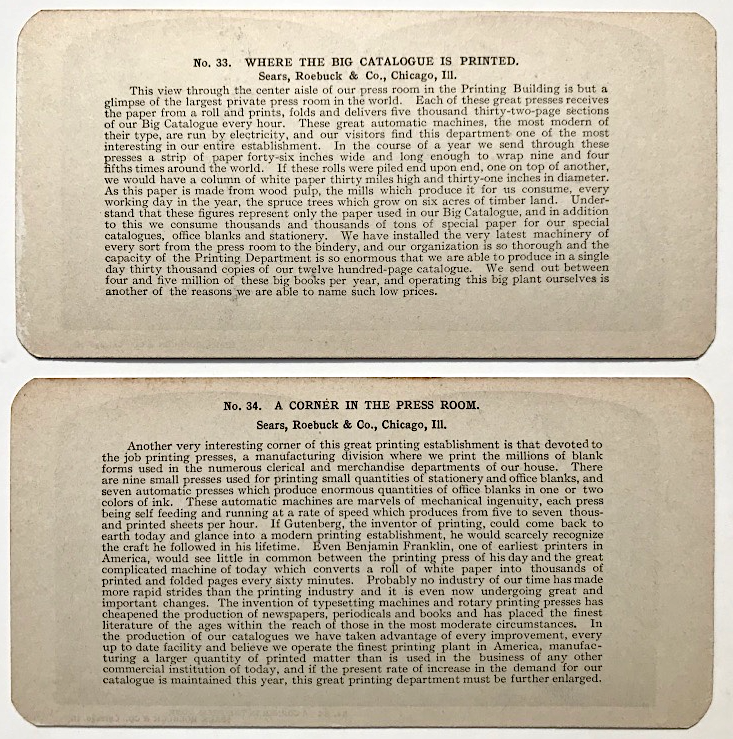

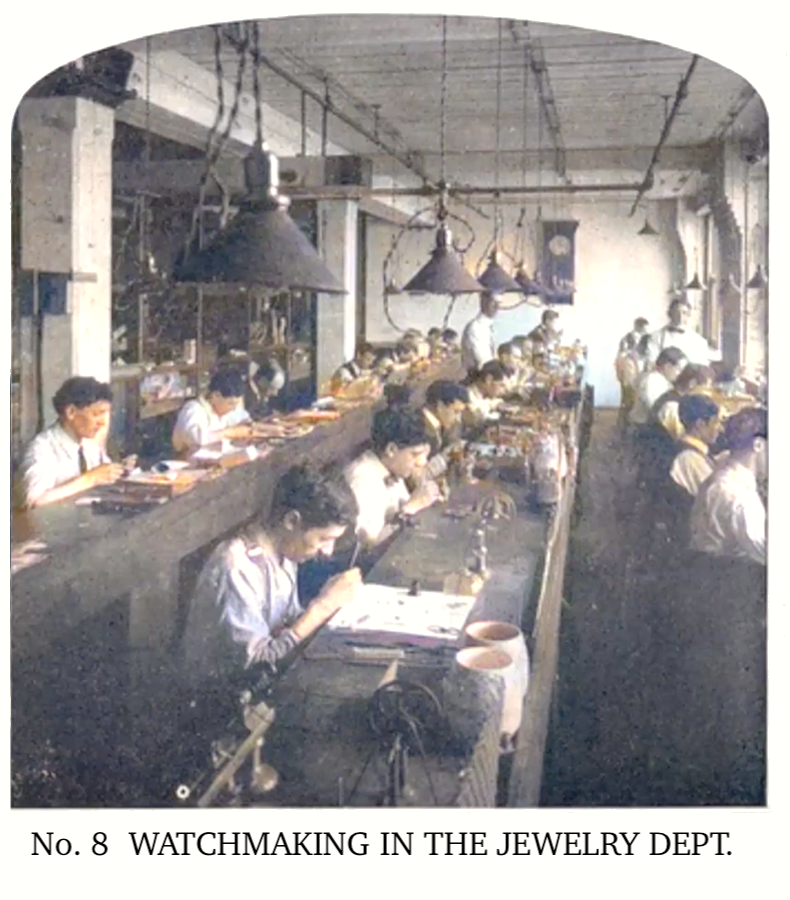

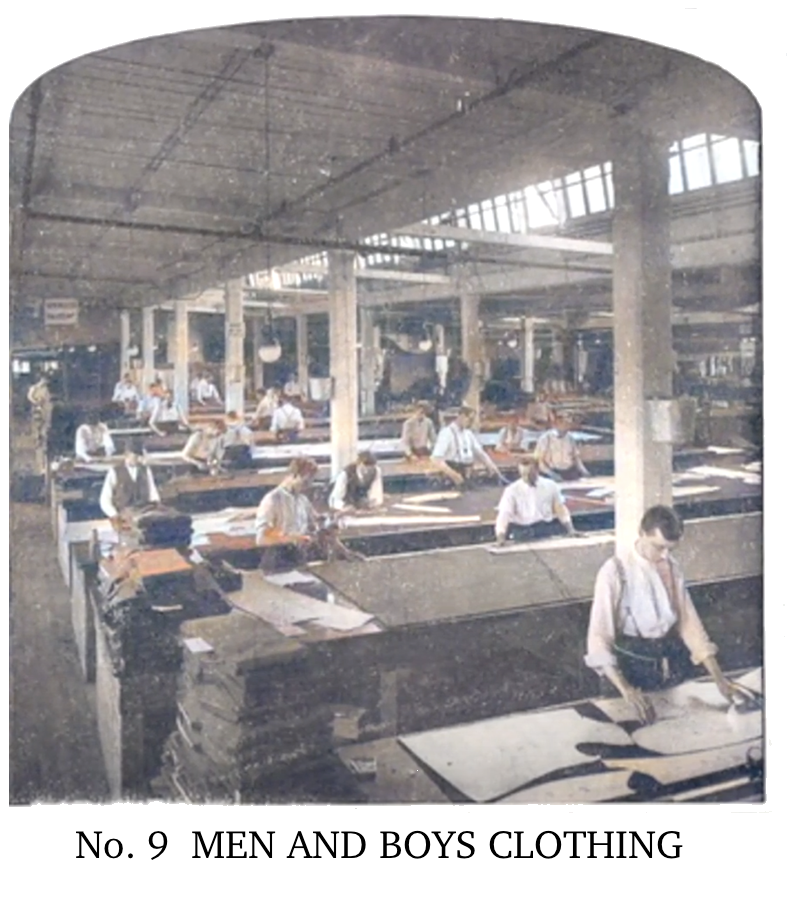

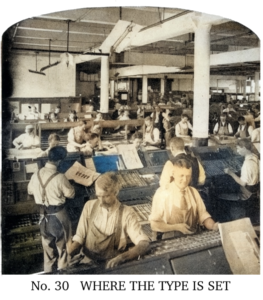

Among the cards is a look inside the jewelry department, with rows of watchmakers hard at work; and another of the men’s clothing manufacturing department, which took up the entire ninth floor of the Merchandise Building. For many years, the famous Sears-Roebuck Catalogue was also produced here in “the largest private press room in the world,” located in the shadow of a 14-story neoclassical warehouse tower.

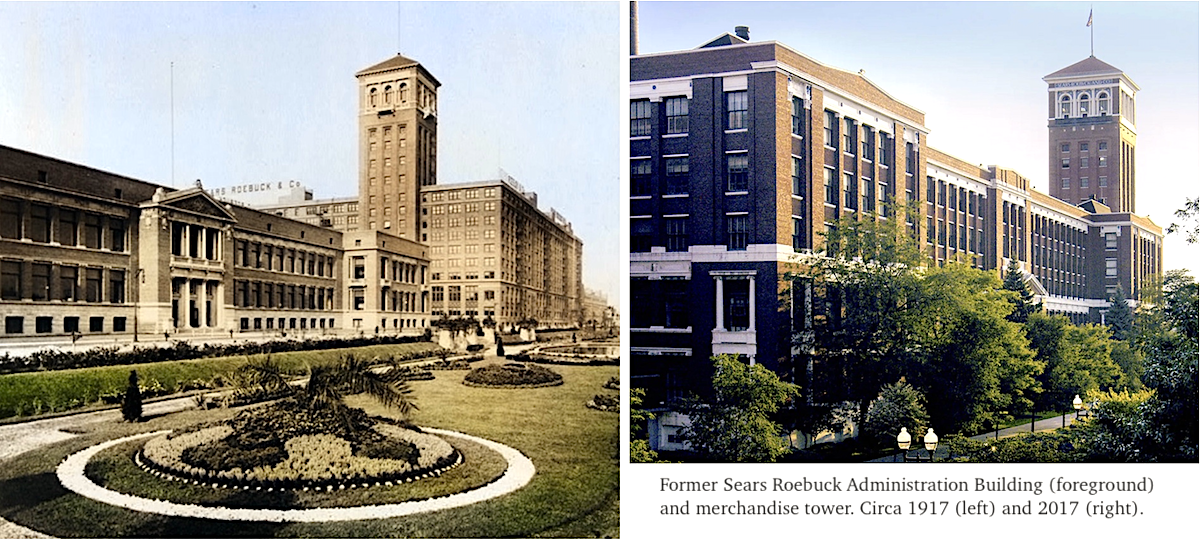

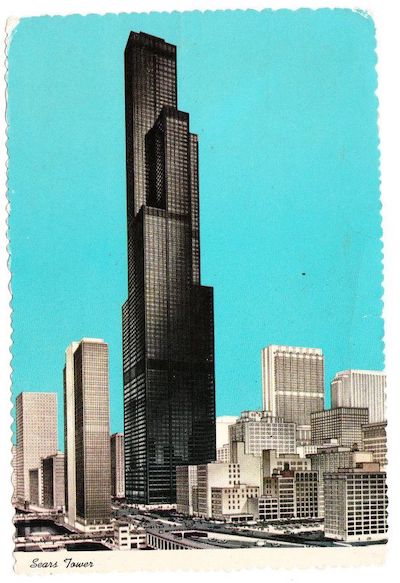

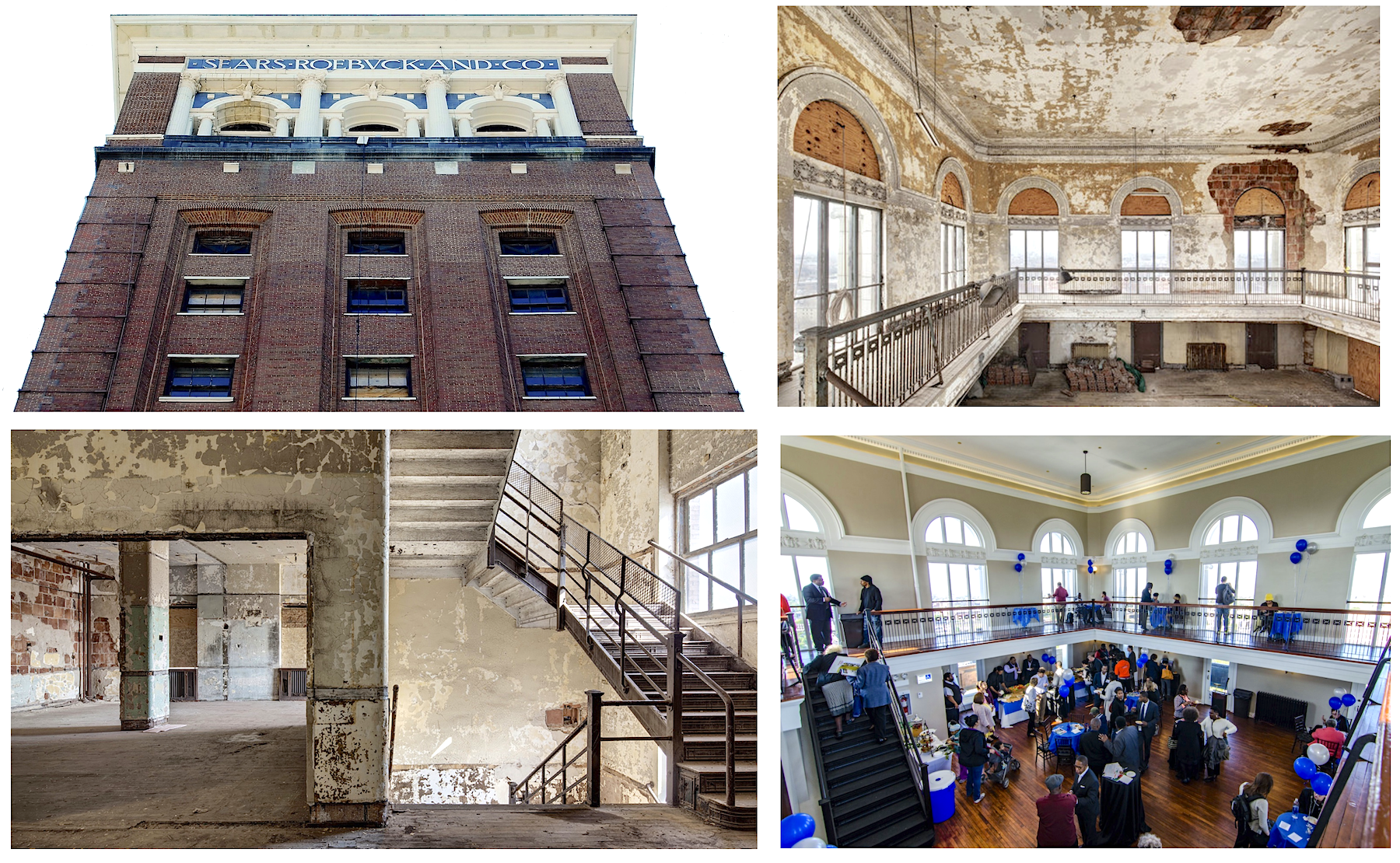

By the 1970s, of course, a new Sears Tower—the tallest building in the world at the time—was completed downtown and became the new company HQ. But to the credit of former Sears Chairman Ed Brennan, the historic old plant wasn’t abandoned and left to the wrecking ball. Instead, working in concert with developer Charles H. Shaw and local government, the area—now known as Homan Square—has gradually been renovated and repurposed for affordable housing and offices, albeit in an area that’s struggled with both crime and controversial policing (one former Sears warehouse was notoriously turned into a secret CPD detention facility, drawing national headlines in 2015). The massive Merchandise Building was ultimately demolished during the modernization effort, but the old Administration Building and original Sears Tower, now called Nichols Tower, still stand—with the latter re-developed in 2016 as a lovely community center and events space. It may yet outlast the actual business of Sears, Roebuck & Company itself.

History of Sears, Roebuck & Co., Part I. Who Watches the Watchmen?

Richard W. Sears “was no more honest than the other snake oil salesmen of his time,” according to Gordon L. Weil, author of the 1977 book Sears, Roebuck, USA: The Great American Catalog Store and How It Grew. “But he was a lot better at writing advertising copy.”

The term “folksy” is often used in reference to Sears, who was born in Minnesota in 1863 and worked as a frustrated station agent before essentially stumbling into the mail-order business in 1886. His first racket was pocket watches, which he ordered in bulk from a Chicago jeweler and then sold off in a sort of pyramid scheme through his network of other freightmen in the North Star State. This profitable enterprise evolved into a business, the R. W. Sears Watch Company, and an eventual move to the commercial hub of Chicago in 1887, where Richard opened an office on Dearborn Street.

The term “folksy” is often used in reference to Sears, who was born in Minnesota in 1863 and worked as a frustrated station agent before essentially stumbling into the mail-order business in 1886. His first racket was pocket watches, which he ordered in bulk from a Chicago jeweler and then sold off in a sort of pyramid scheme through his network of other freightmen in the North Star State. This profitable enterprise evolved into a business, the R. W. Sears Watch Company, and an eventual move to the commercial hub of Chicago in 1887, where Richard opened an office on Dearborn Street.

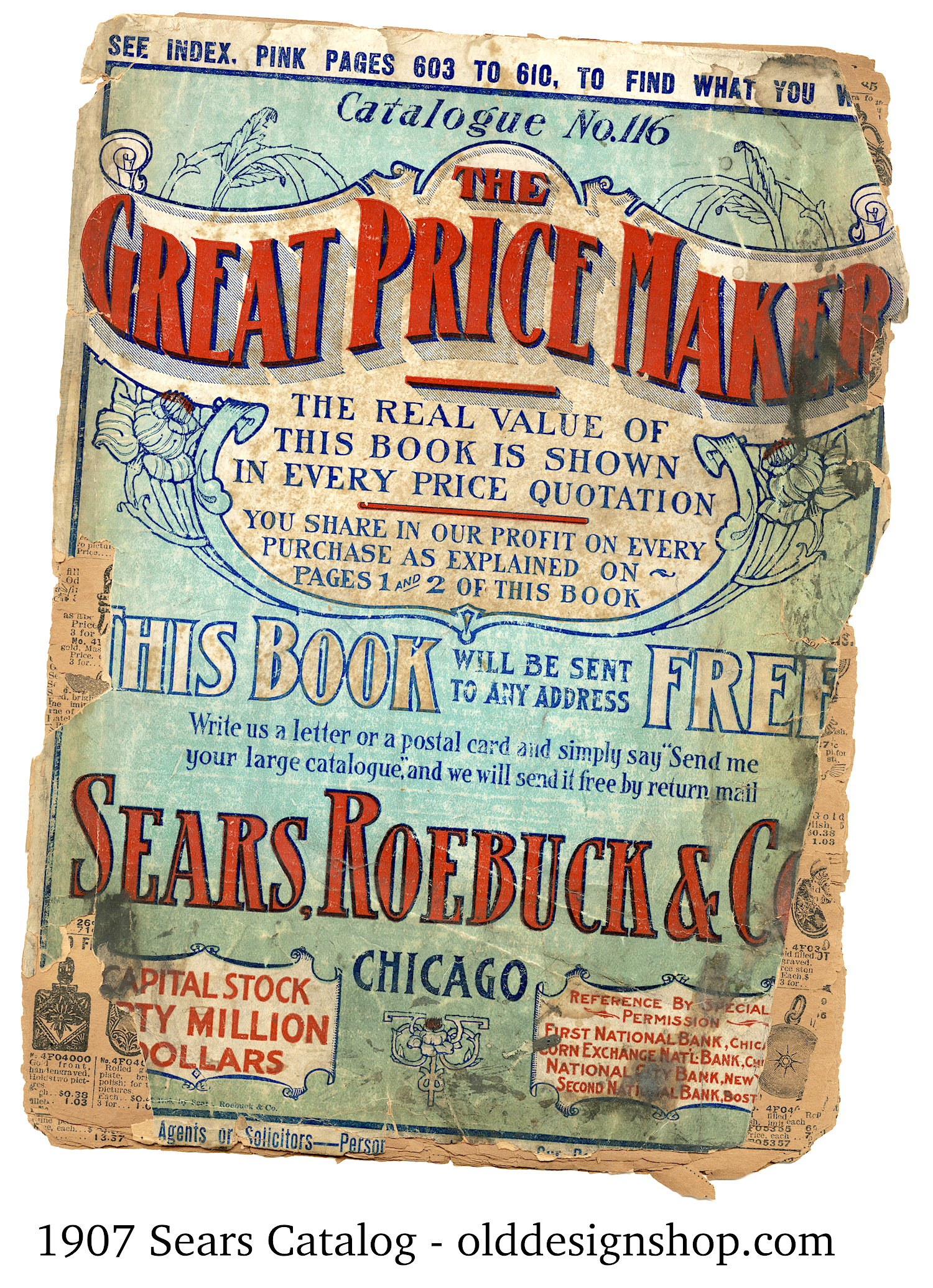

Tellingly, Richard Sears was never motivated to learn much about the watches he was selling or how they worked; his interest, and skill, was in touting them—taking advantage of the loose or non-existent advertising laws of the day. It’s hard to say whether his ad copy reflected a unique understanding for his mostly rural Midwestern clientele or just the manipulative wordplay of a huckster . . . maybe both? In any case, the results of Sears’s unusually prolific newspaper promotions paid off rapidly, as the R. W. Sears catalog got a bit heftier with each new edition.

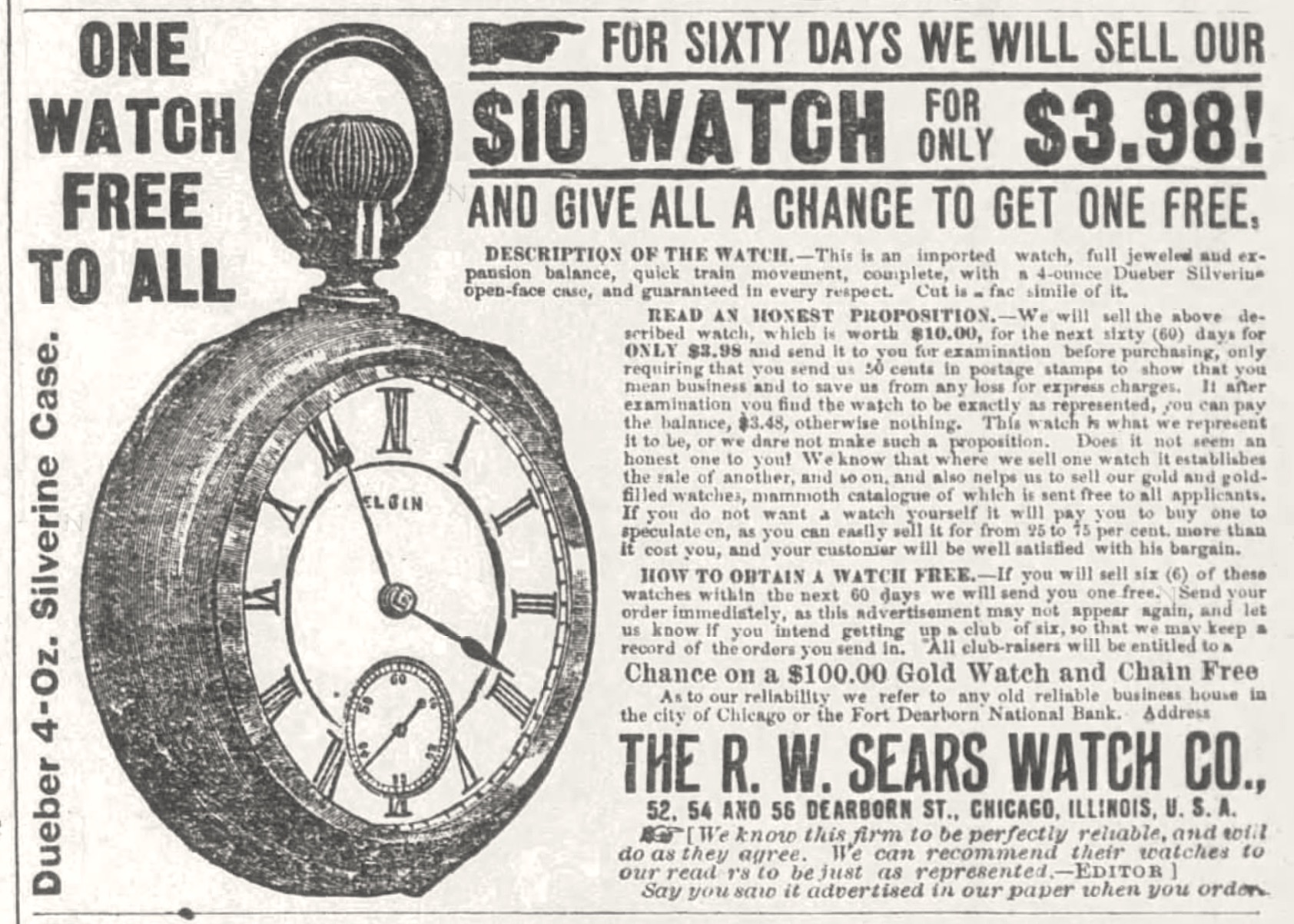

“For sixty days we will sell our $10 watch for only $3.98!” read one newspaper ad from 1888, featuring an image of an Elgin pocket watch and an offer for readers to “examine it” before buying, for the cost of a mere 50 cents in postage. “This watch is what we represent it to be, or we dare not make such a proposition. Does it not seem an honest one to you! We know that where we sell one watch it establishes the sale of another, and so on, and also helps us to sell our gold and gold-filled watches, mammoth catalogue of which is sent free to all applicants. If you do not want a watch yourself, it will pay you to buy one to speculate on, as you can easily sell it for from 25 to 75 percent more than it cost you, and your customer will be well satisfied with his bargain.”

[1888 newspaper ad for the R. W. Sears Watch Co.]

Clearly, even at the age of 25, Sears had a methodology to his madness; enticing customers not just with the idea of buying a product, but with the incentive of becoming “in the know” dealers the same way he had. The only thing his business was missing was someone with actual technical knowledge about the merchandise, and he found that in Alvah C. Roebuck (1864-1948); a Hammond, Indiana watchmaker who answered a wanted ad posted by Sears in the Chicago Daily News.

According to Gordon Weil’s version of events, Roebuck came in for an interview at the R. W. Sears office on Dearborn and presented a watch he’d made, representing the best of his talents. “Sears took the timepiece and examined it, much as an illiterate ‘reads’ a letter,” Weil wrote. “Finally, he dropped all pretense. ‘I don’t know anything about watchmaking but I presume this is good, otherwise you wouldn’t have submitted it to me. You look alright and you may have the position.’”

And thus began the on-again / off-again corporate bromance that would come to define both men’s legacies.

Things were rocky right from the get-go, as Richard Sears’s somewhat whimsical impulses saw him sell off his interest in the R. W. Sears Watch Co. to Roebuck; then move back to Minneapolis; then start another watch company of his own (called the Warren Company); then buy back in to a new deal with Roebuck . . . all in the span of a few years. Alvah, the steady tinkerer, was a much needed foil for the young Sears, but after finally establishing Sears, Roebuck & Co. together in 1893—the same summer as the Columbian Exposition—the duo never really found a way to healthfully co-exist as partners.

In a 1984 Sears retrospective called Shaping An American Institution, author James C. Worthy writes, “it is obvious that Richard Sears was one of the great promotional geniuses in American business history, but he was also a poor businessman and an inept manager. He gave scant attention to the handling of rapidly increasing number of orders his advertising and catalogs brought in, and the internal affairs of the company were chaotic.”

Roebuck ultimately found Sears’ reckless business practices too stressful to cope with, and asked for a $20,000 buyout in 1895. Sears agreed, but a rather odd agreement was eventually reached that saw Roebuck happily return in a different role—as manager of the jewelry and watchmaking department; doing what he loved without the pressure of keeping the books balanced.

The company name, despite this change in the executive offices, was already written in literal stone. But with Roebuck more content under a factory lamp, Richard Sears would need a new partner—a leader and an organizer—to help ensure Sears, Roebuck & Co. could continue to expand without exploding. Success in the 20th century would depend on who could fill those shoes, and those orders.

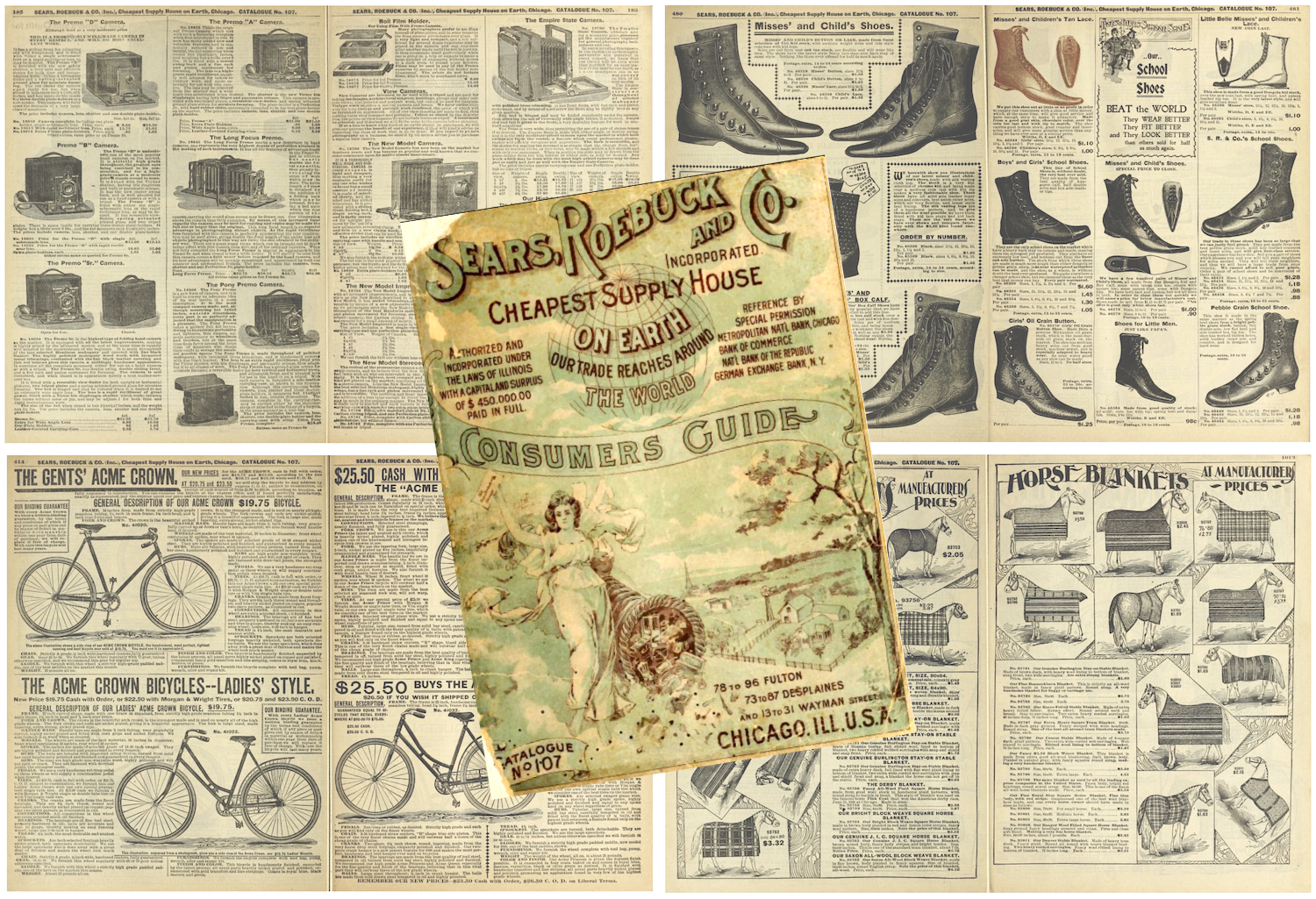

[Pages from Sears, Roebuck & Co. catalogue No. 107, 1898]

Part II. Hail Julius

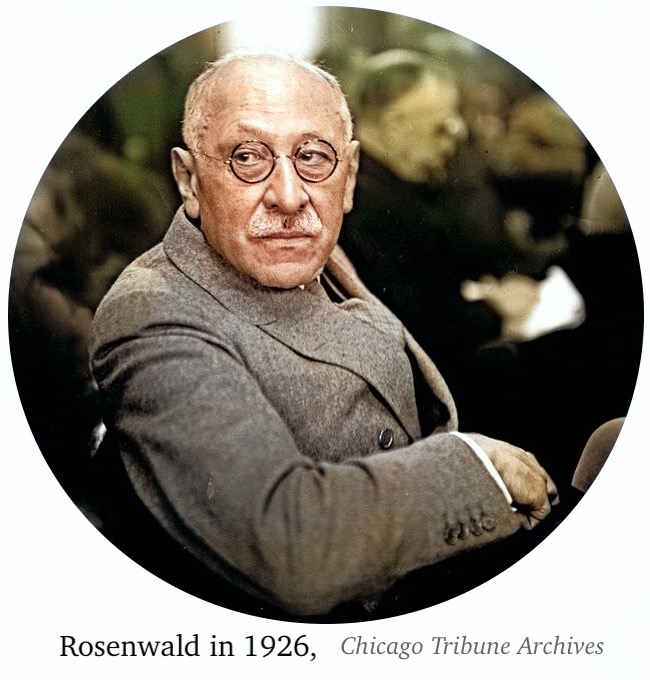

“Most people are of the opinion that because a man has made a fortune, his opinions on any subject are valuable. For my part, I always believe most large fortunes are made by men of mediocre ability who tumbled into a lucky opportunity and couldn’t help but get rich, and that others, given the same chance, would have done far better with it.” —Julius Rosenwald, Sears chairman, 1929

Being the humble, oft-forgotten hero of the Sears story, it’s safe to assume that Julius Rosenwald was referring to himself as the “lucky” individual in the quote above. But he just as easily could have been talking about Richard Sears as the “mediocre” rich man and himself as the one who, given the same chance, did “far better” with a unique opportunity.

Being the humble, oft-forgotten hero of the Sears story, it’s safe to assume that Julius Rosenwald was referring to himself as the “lucky” individual in the quote above. But he just as easily could have been talking about Richard Sears as the “mediocre” rich man and himself as the one who, given the same chance, did “far better” with a unique opportunity.

Born in Springfield, Illinois, in 1862, Rosenwald was the son of German Jewish immigrants. At the time of his birth, his father Samuel was building a men’s clothing business, making decent money selling uniforms for Union soldiers during the Civil War. Julius followed the same path; not finishing high school or college, but becoming a moderately successful men’s garment maker in Chicago. He even sold some of his suits in an early Sears mail-order catalog, making him well acquainted with the business and its frustrating president Mr. Sears, who already had a reputation for going into debt with his suppliers.

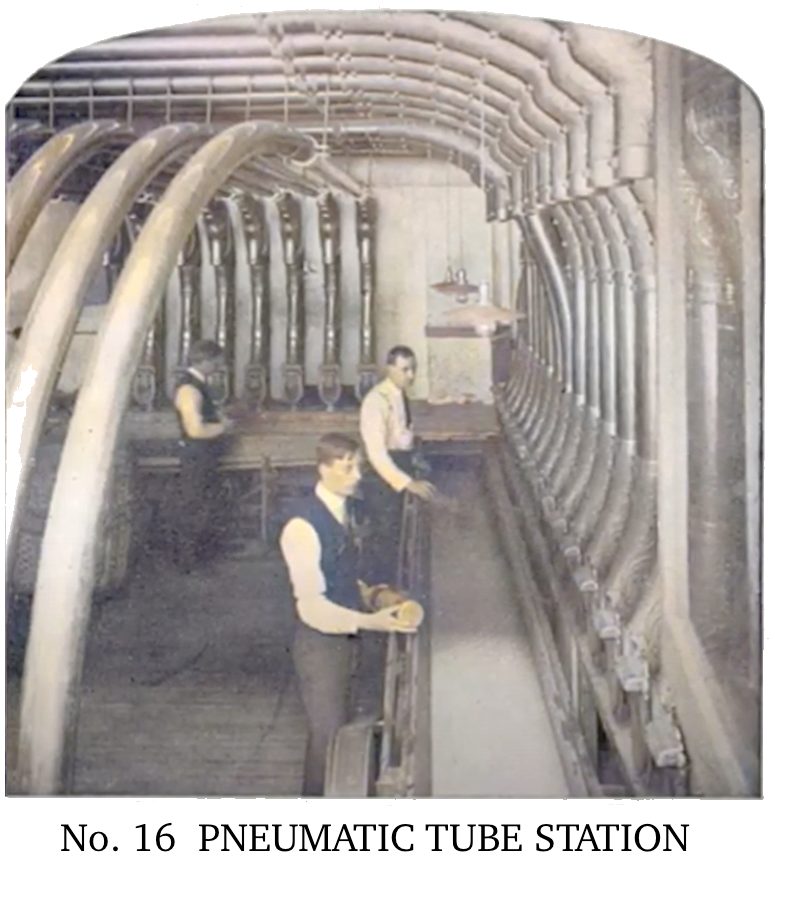

In 1895, Rosenwald and his brother-in-law Aaron Nusbaum (a pneumatic tube manufacturer) joined forces to buy a 50-percent share in Sears, Roebuck & Company for the price of $75,000. These men were not captains of industry, and Sears was still known mainly as a watch dealer. But things changed in a hurry.

“In opposition to Sears’s belief that innovative gimmicks were essential to keep the mail-order business healthy, Rosenwald and Nusbaum were convinced that sound business practices were important,” author Peter M. Ascoli writes in his 2006 book Julius Rosenwald: The Man Who Built Sears, Roebuck. “If supply could not keep up with demand, it was time to cool down demand and ensure that goods went out correctly and in a timely fashion. . . . Real improvement was made in record keeping and data gathering. For the first time, information was developed about sales in each department on a weekly, monthly, and even a daily basis. Reports were also available that showed sales for one week compared with sales for the same week one year previously.”

Amazingly enough, these were revolutionary practices for the 1890s, and combined with a booming U.S. economy, Chicago’s enviable shipping advantages, and a growing list of interested suppliers, a new mail-order behemoth was born.

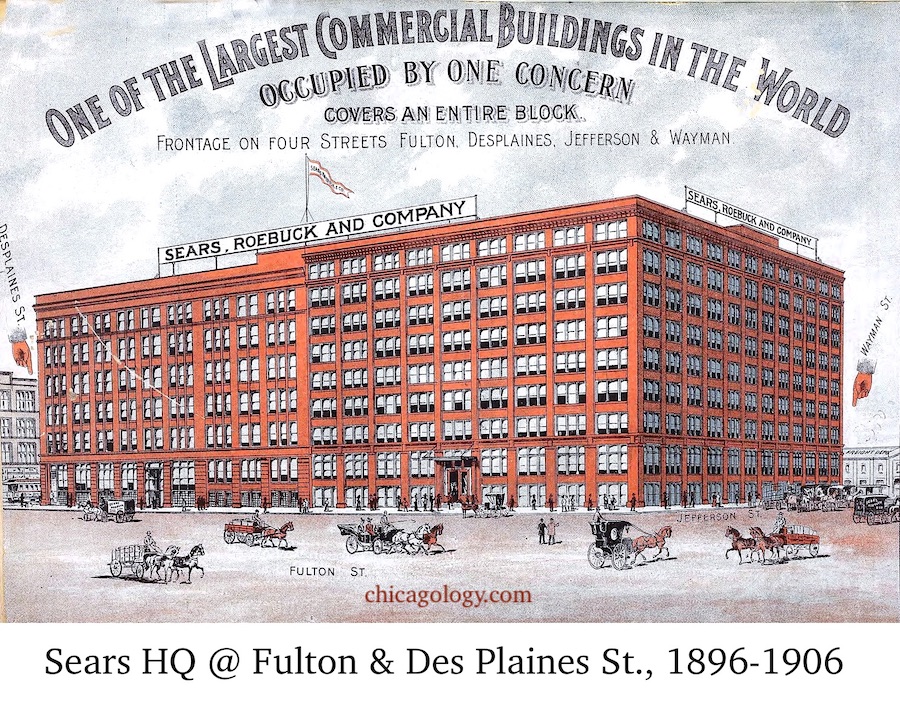

Between 1895 and 1900, sales increased from $750,000 to over $10 million, and a new headquarters at West Fulton Street and Des Plaines Street (the Enterprise Building) grew to cover a whole city block and stand eight stories in height. The catalog expanded equivalently, now featuring everything from food stuffs and stoves to bicycles and firearms. Even so, neither R. W. Sears nor his partners were basking in contentment. Nusbaum, in particular, had a rough temperament that had grated on both Sears and Rosenwald, and by 1901, Julius agreed to oust his own brother-in-law from the business. Nusbaum got a handsome $1.25 million payout on the way out, but it probably didn’t make things any more pleasant at the next Passover dinner with the extended family.

Between 1895 and 1900, sales increased from $750,000 to over $10 million, and a new headquarters at West Fulton Street and Des Plaines Street (the Enterprise Building) grew to cover a whole city block and stand eight stories in height. The catalog expanded equivalently, now featuring everything from food stuffs and stoves to bicycles and firearms. Even so, neither R. W. Sears nor his partners were basking in contentment. Nusbaum, in particular, had a rough temperament that had grated on both Sears and Rosenwald, and by 1901, Julius agreed to oust his own brother-in-law from the business. Nusbaum got a handsome $1.25 million payout on the way out, but it probably didn’t make things any more pleasant at the next Passover dinner with the extended family.

With Nusbaum gone, Rosenwald and Sears turned their focus to the next great undertaking—streamlining Sears’s entire operation into a new headquarters on an unprecedented scale, fully equipped for the modern age.

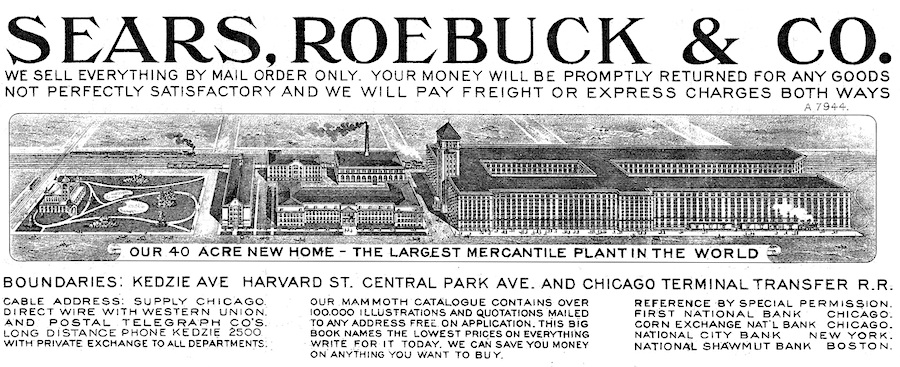

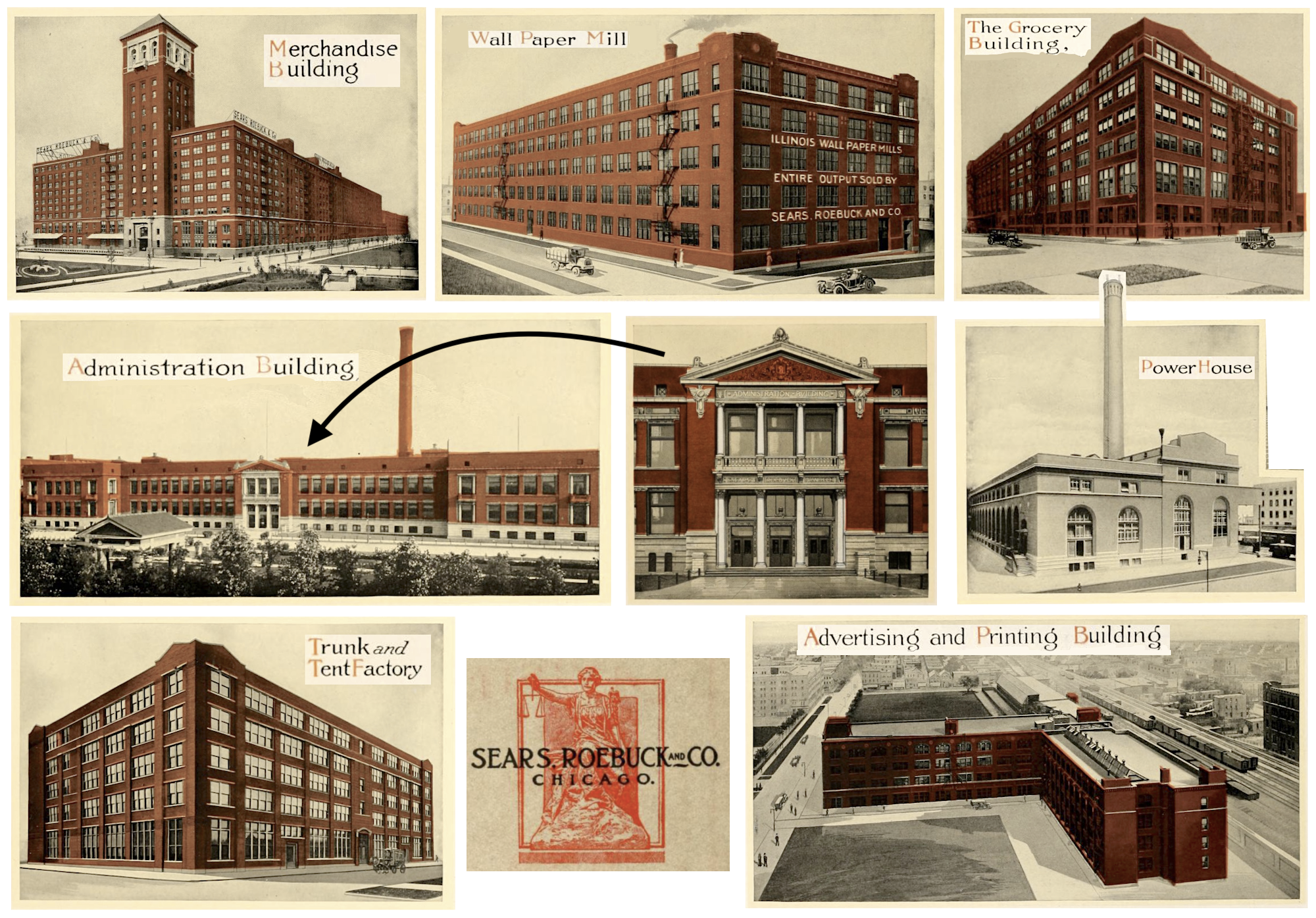

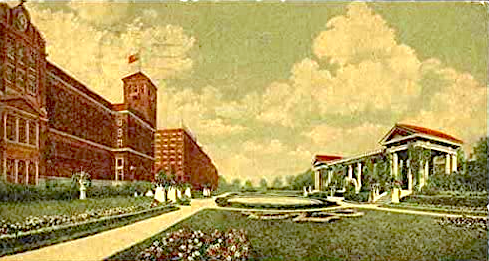

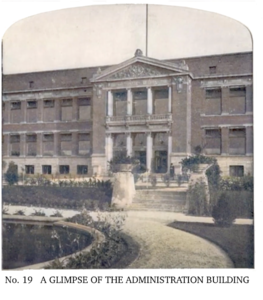

“The company hired the finest architects, planners, builders, and craftsmen,” John Oharenko writes in 2005’s Images of America: The Historic Sears, Roebuck and Co. Catalog Plant. “Every effort was made to visually blend the commercial structures to the surrounding parks and boulevards, and the new and residential district of North Lawndale. . . . The scale of work is astonishing even by today’s standards. Some 7,000 artisans and laborers were working on the building at one time. And 353,000 bricks were laid within eight hours.”

As the work neared completion in 1906, Rosenwald cashed in another bit of good fortune, phoning up a childhood friend named Henry Goldman, now a partner in the New York investment firm Goldman Sachs. Rosenwald hoped to secure a loan to help handle the new plant’s expenses, but Goldman had a better idea. Forming a syndicate with another familiar name of big banking, Lehman Brothers, he convinced Rosenwald and Sears to take their company public with an IPO, believing the good reputation of the Sears catalogs would make it an appealing buy. The gamble paid off, and $40 million was secured in preferred and common stock.

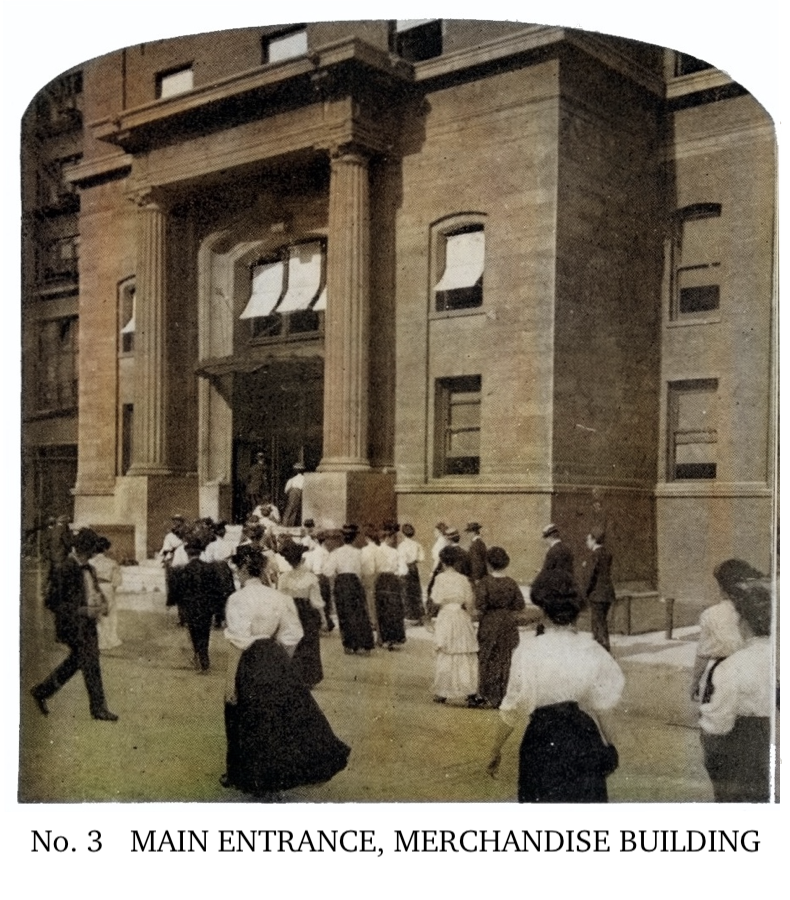

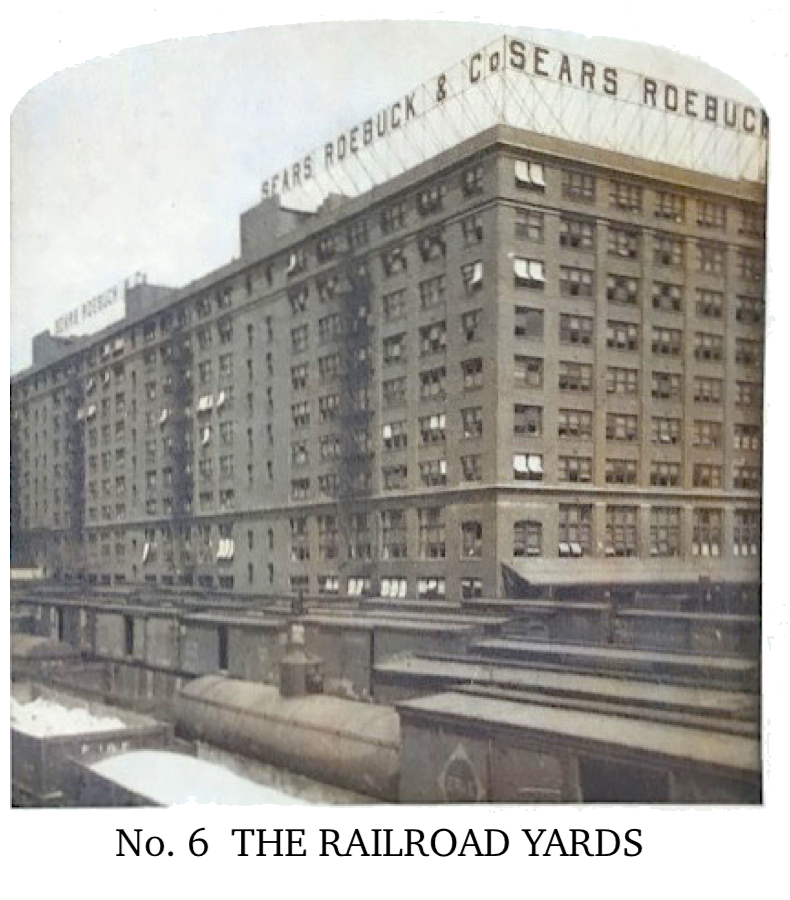

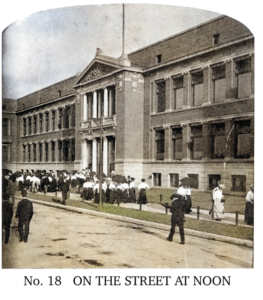

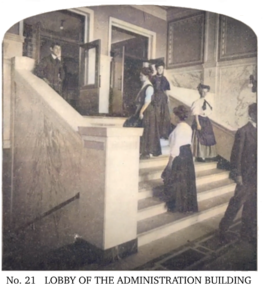

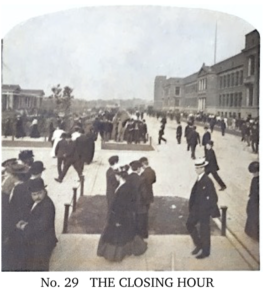

Naturally, Sears made its new headquarters—which actually contained seven interconnected buildings with a total floor space of 3 million square feet—a focal point of its national advertising from 1906 onward. Not only were 9,000 employees migrating to the campus, but an invitation was put out to any of the company’s 6 million customers to stop by and get a free tour, as well.

“If you ever come to Chicago don’t fail to pay us a visit at our new 40-acre home,” read a 1908 profit-sharing booklet. “It’s the wonder of the commercial world, the largest mercantile plant in the world, the largest single buildings in the world devoted to the handling of merchandise.”

Part III. A Trip Through Sears, Roebuck & Co.

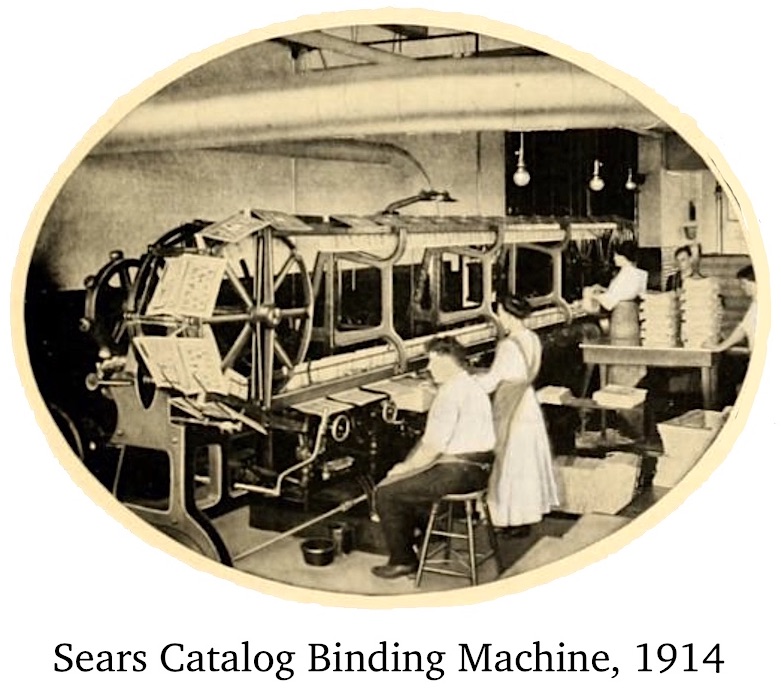

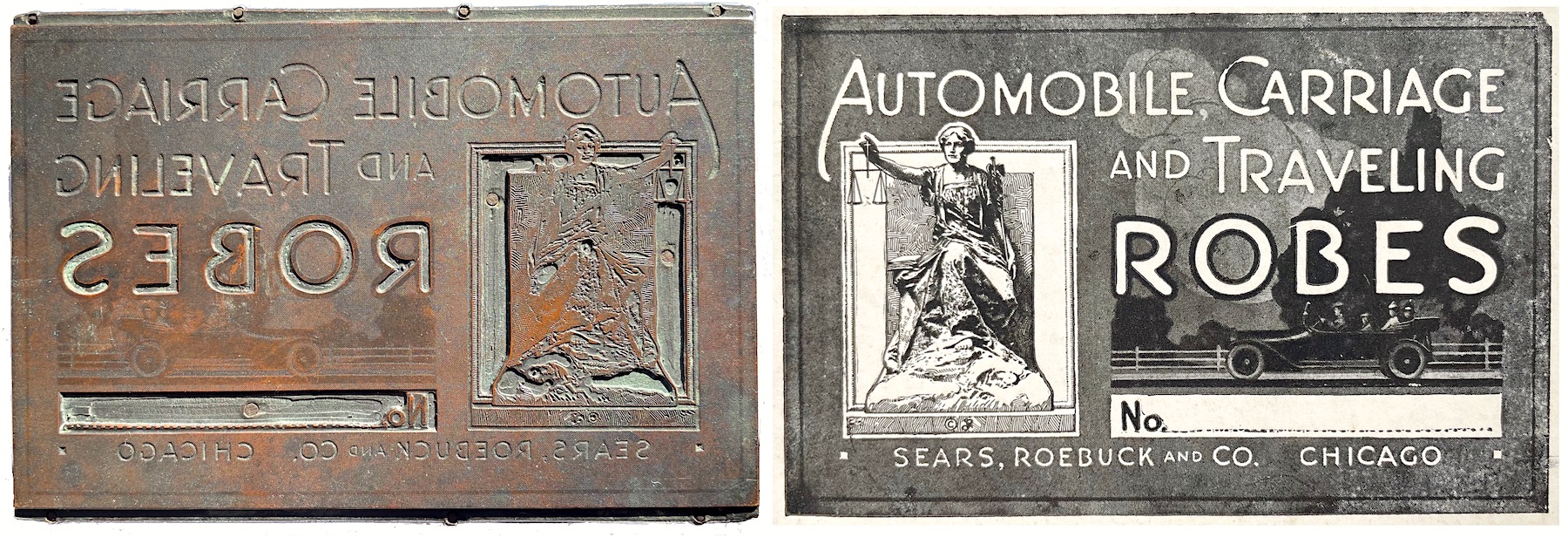

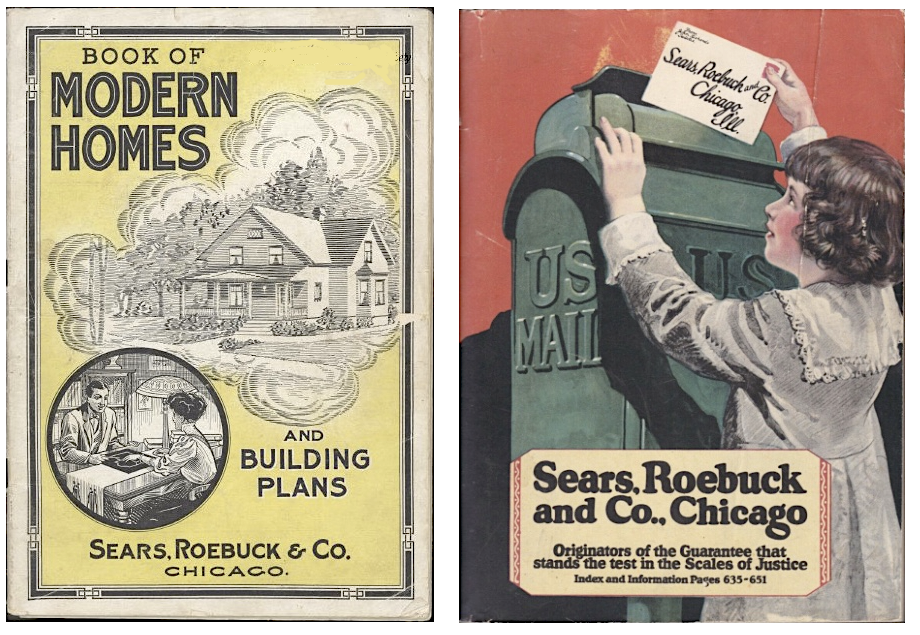

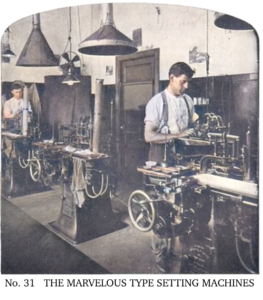

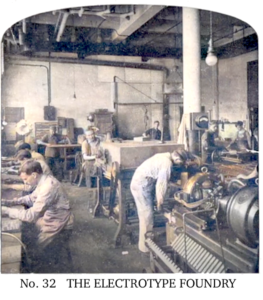

For the vast majority of Sears catalog customers, a journey to Chicago wasn’t in the cards. So, as an alternative, a set of literal cards was commissioned to give the public a virtual tour of the North Lawndale plant and campus. These were printed in Sears’s own press room, of course, using a letter press and copper plates, but unlike a standard photo postcard, they were displayed in the trendy side-by-side Stereoview format, which added an illusion of 3-D depth when the card was looked at through a stereoscope viewer (sold separately in the Sears catalog!).

The 50 featured photos were likely taken by representatives of the Conley Camera Company of Minnesota, which Richard Sears had acquired as his company’s primary camera supplier back in 1903. The images date from the time of the plant’s grand opening in 1906, but the cards weren’t properly printed, boxed, and advertised until 1908, when the catalog priced the full set at 30-cents, complete with a leatherette box.

The 50 featured photos were likely taken by representatives of the Conley Camera Company of Minnesota, which Richard Sears had acquired as his company’s primary camera supplier back in 1903. The images date from the time of the plant’s grand opening in 1906, but the cards weren’t properly printed, boxed, and advertised until 1908, when the catalog priced the full set at 30-cents, complete with a leatherette box.

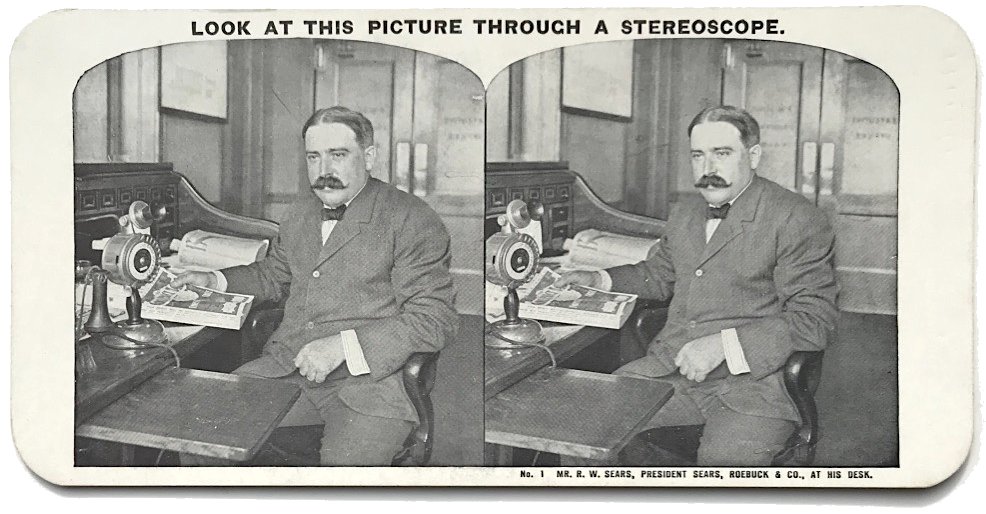

Card No. 1, naturally, features Richard W. Sears himself—still only a tad over 40 years old—sitting a bit awkwardly at his desk and clutching a Sears Roebuck catalog in his right hand. In our museum’s set, the backside of this card is completely blank, but in other printings, it includes a personal greeting from Mr. Sears. In some ways, it’s also his farewell address, as a bout of ill health led to his unexpected retirement from the company presidency before the end of 1908. Sears remained in the role of chairman, but died just six years later from Bright’s Disease at the age of 50.

“I regret it is impossible for me to meet every one of our customers face to face and know them personally,” Sears wrote, “yet our relations with hundreds of thousands, though separated by many miles, have been so pleasant and satisfactory that I feel I almost know them as neighbors.

. . . I regret, too, that all our customers cannot with their own eyes see the place where their orders are filled and see the people who do the work, how they do it and how they are directed. . . . For the benefit of those who cannot, these fifty stereoscopic views have been gotten out that you, in your own home, may have a little insight into the ways we do our business and the place in which it is done. Hoping this insight into our institution will make you feel even better acquainted with Sears, Roebuck & Co., and the writer, I am, most gratefully yours, Richard W. Sears.”

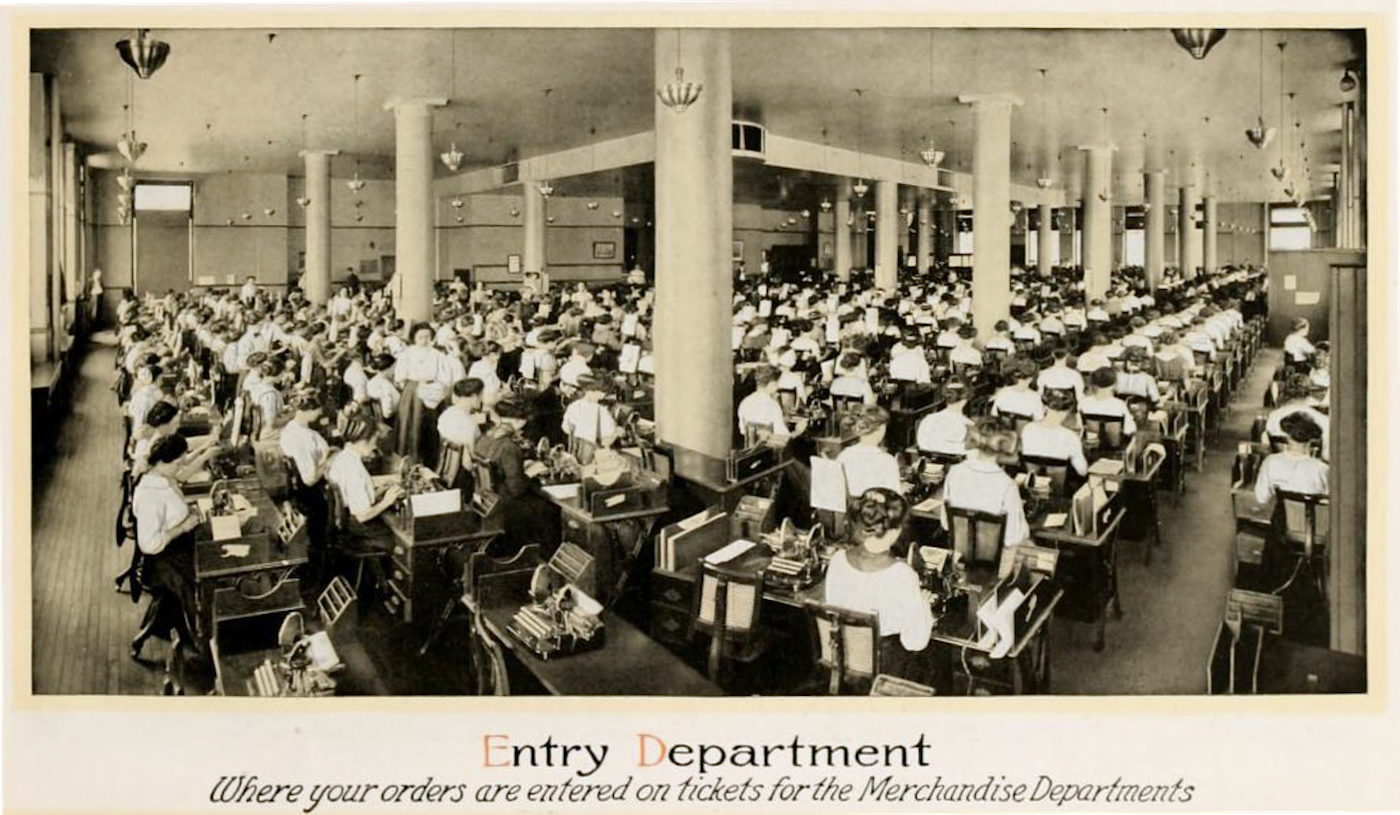

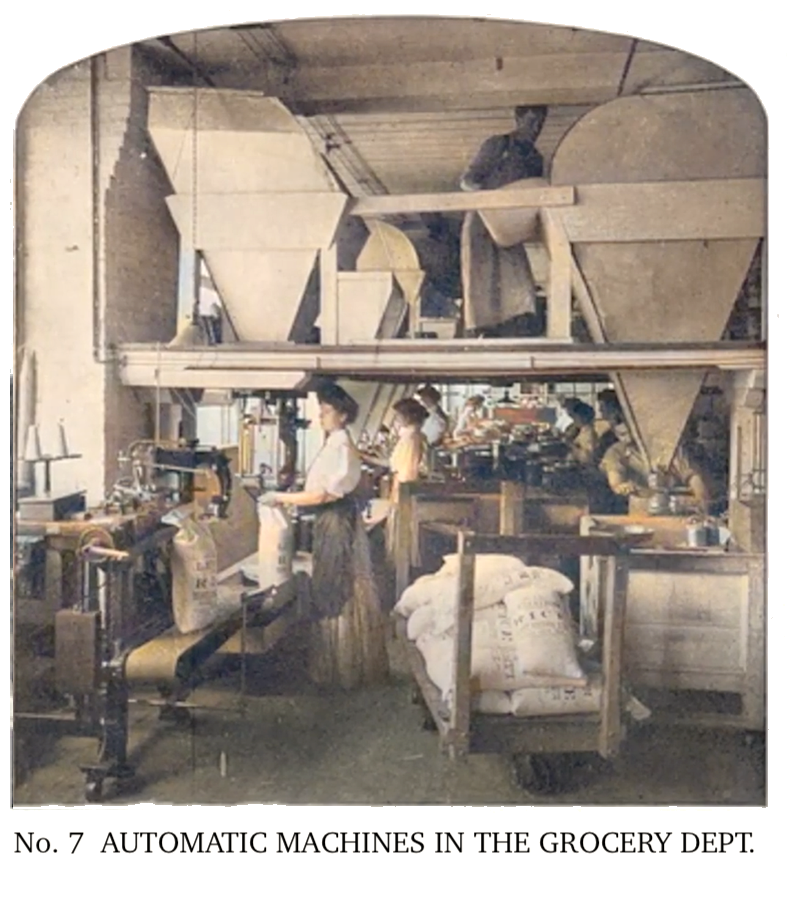

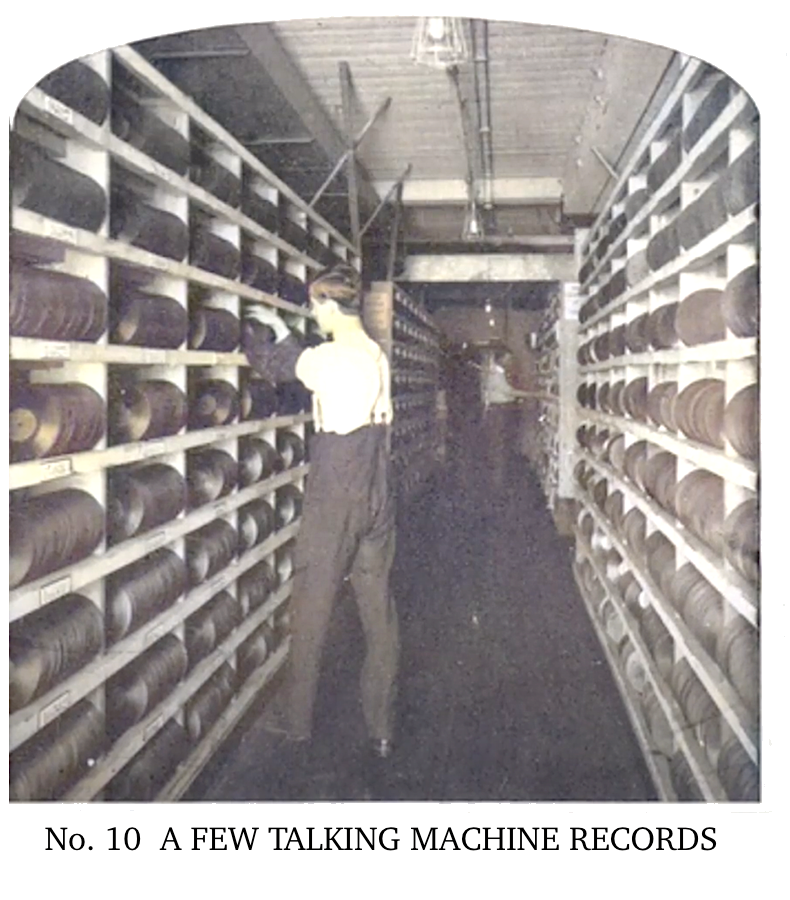

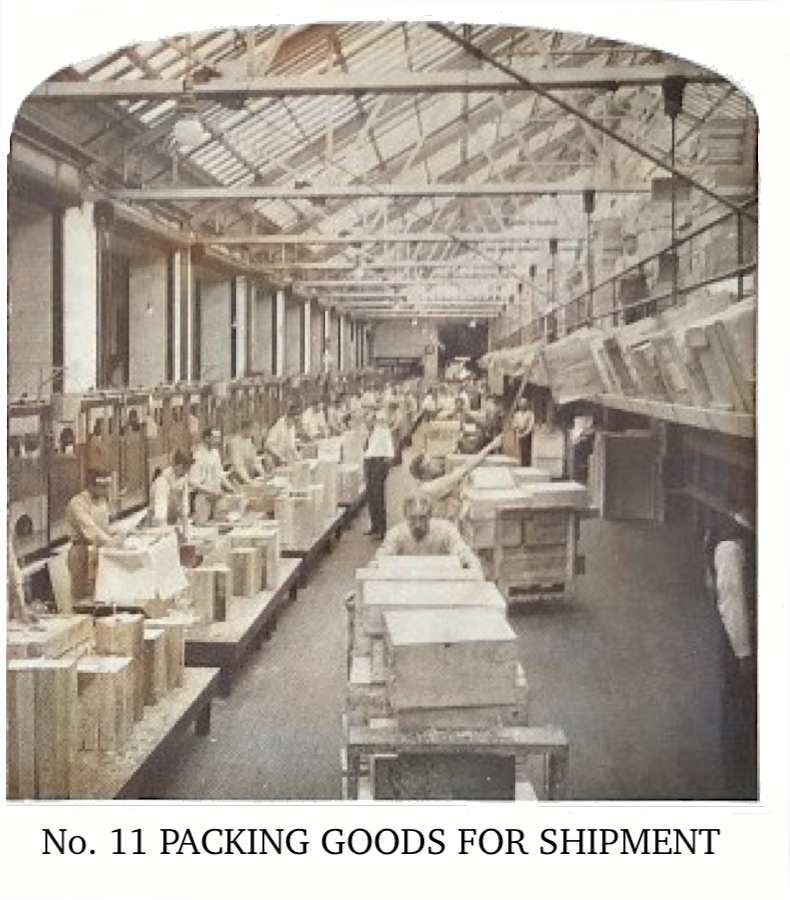

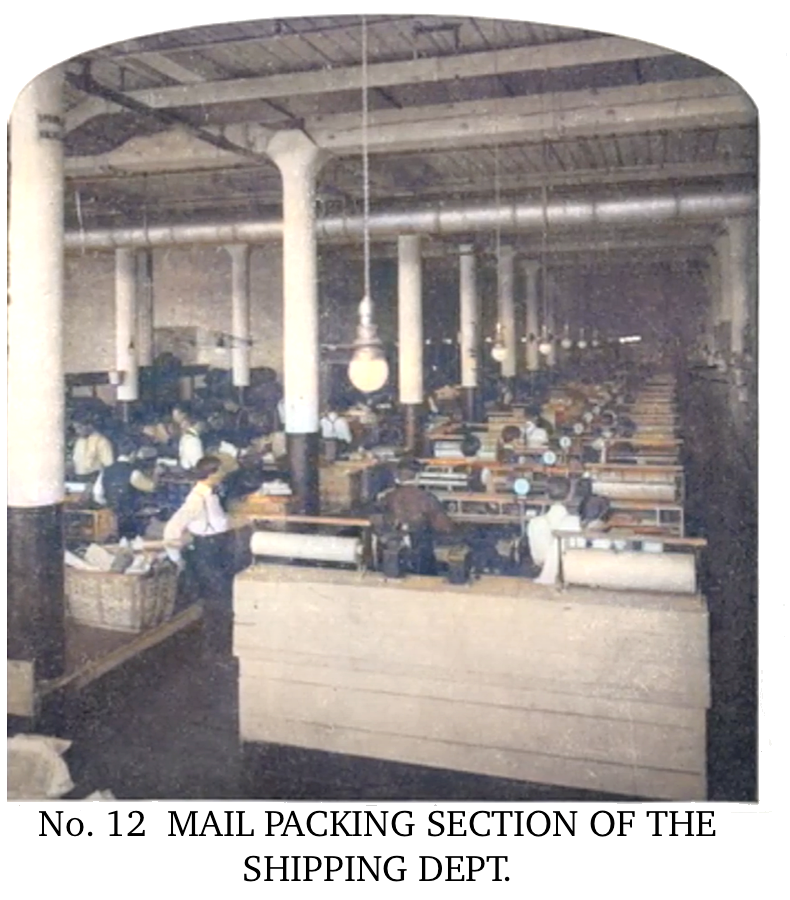

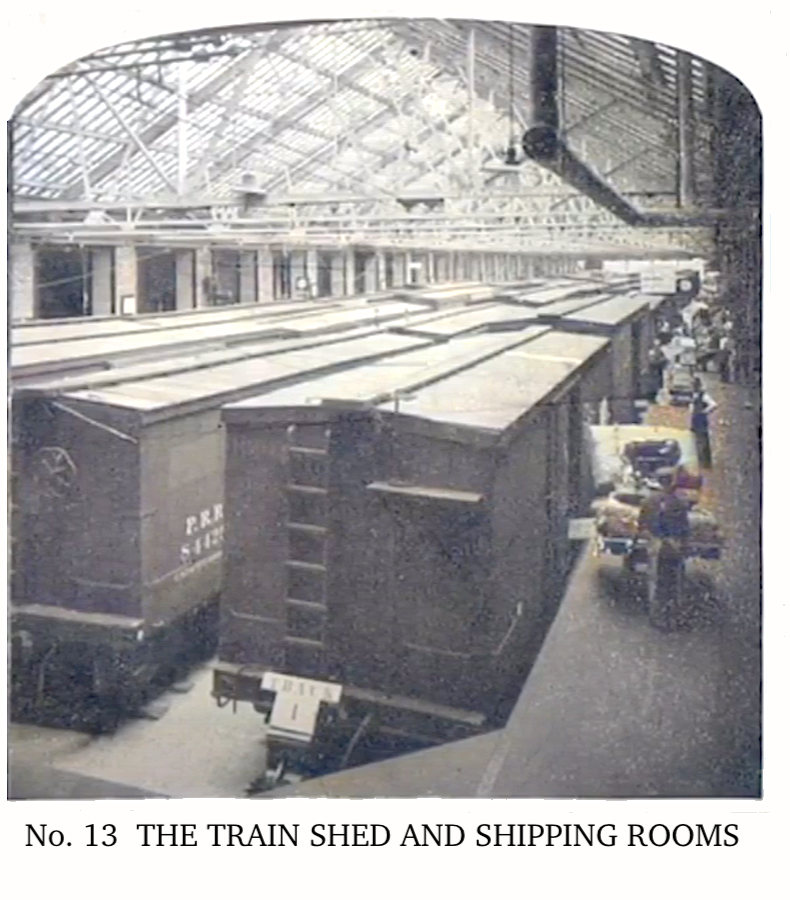

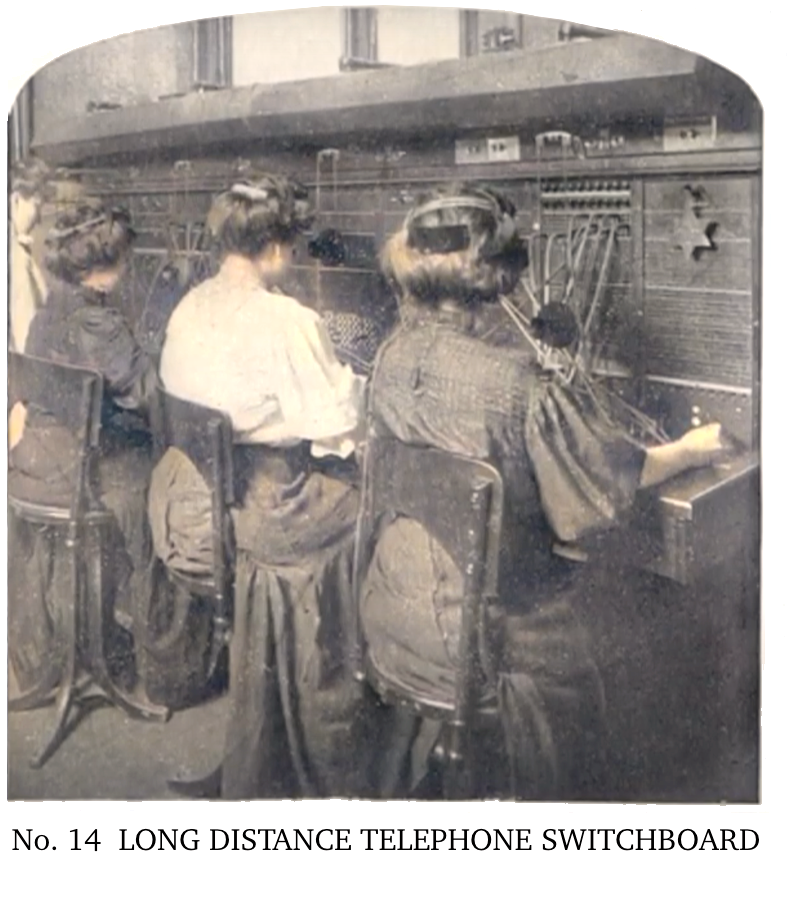

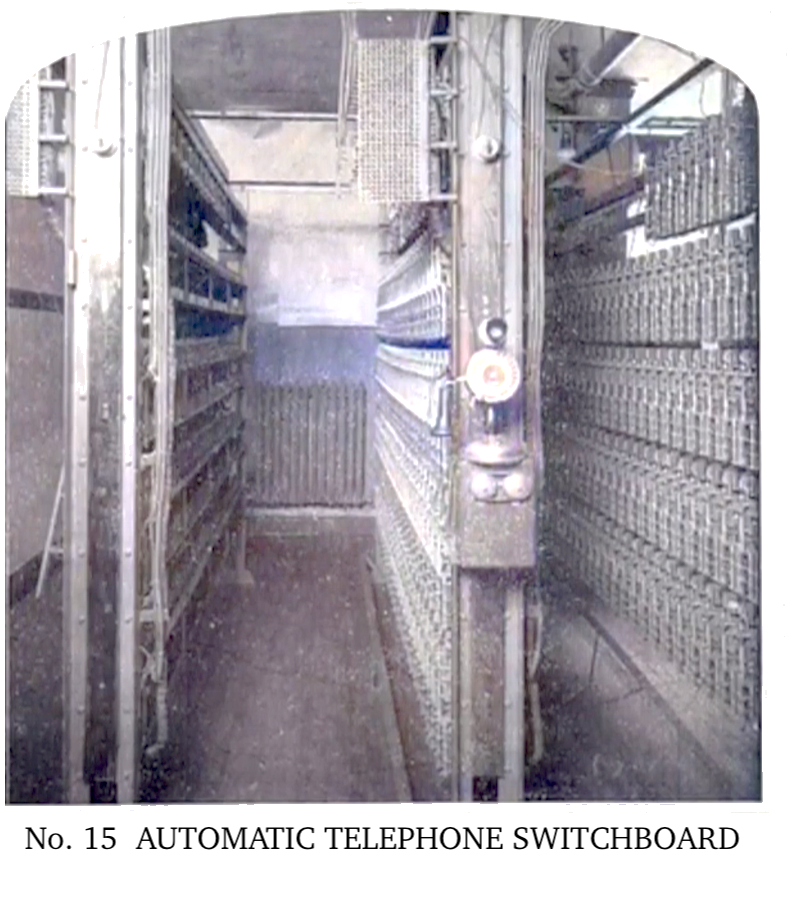

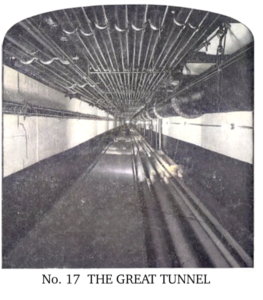

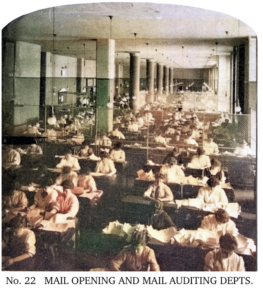

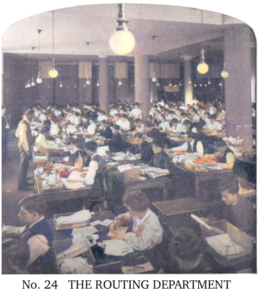

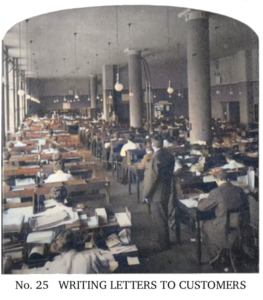

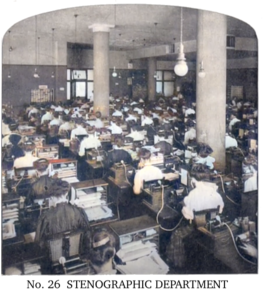

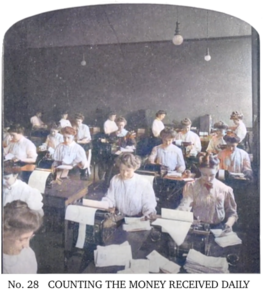

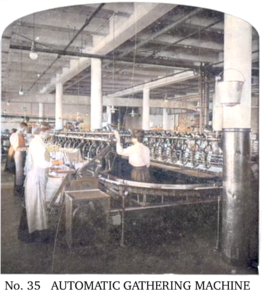

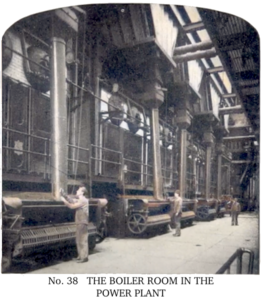

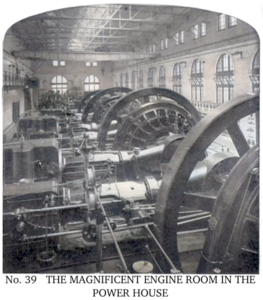

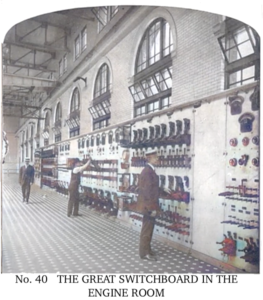

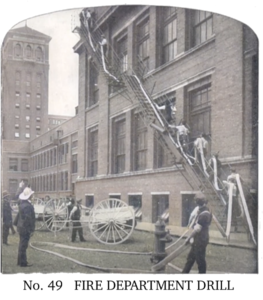

The Stereoview cards, which were collectively titled, “A Trip Through Sears, Roebuck & Co.,” clearly endeavored to show a balance of the plant’s internal efficiency and outward beauty. There’s also a mix of human power and state-of-the-art machine power—a sea of 200 women transcribing letters on stenographs; fruits and veg getting weighed, measured, and wrapped by automatic machines; calls being received at a long distance telephone switchboard; and the remarkable pneumatic tubes and underground tunnel systems that made the whole complex navigable in seconds, or, at least, minutes.

“A Trip Through Sears, Roebuck & Co.” 1908, Colorized Stereoview Card Images #17-32 [Click Any to Enlarge]

Along with Rosenwald, a man named Otto Doering seemed to be the brains of the operation, which makes sense, as his job title was literally operations superintendent.

“Doering introduced a system where each order was assigned a particular shipping room for a particular fifteen-minute period,” according to research by Daniel Raff and Peter Temin in their 1999 paper, Sears, Roebuck in the Twentieth Century: Competition, Complementarities, and the Problem of Wasting Assets. “Each department supplying an item in the order was notified of this time and place and directed to deliver the item then and there. Items not arriving in time were shipped separately. The supplying department was billed for the extra cost. Why did this system work so well? At a formal level, it worked because it subdivided the process of mailing goods into its component parts and provided the opportunity and the incentives for each part to be done well. The component parts were finding the goods, assembling the order, and packaging it.”

Things were a little bit simpler when it came to the Sears catalogue, which was printed and shipped at such volume that every household in America might as well have placed an order.

Things were a little bit simpler when it came to the Sears catalogue, which was printed and shipped at such volume that every household in America might as well have placed an order.

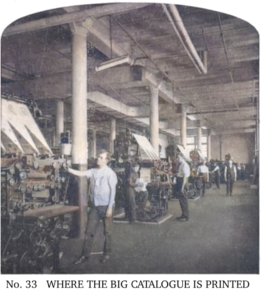

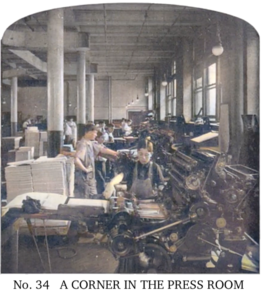

“Every modern machine and appliance known to the book-making industry is employed in the printing plant to facilitate the rapid and the economical production of our great catalogue,” reads the description on Stereoview card No. 37. Another card, No. 33—offers “a glimpse of the largest private press room in the world. . . . Our organization is so thorough and the capacity of the Printing Department is so enormous that we are able to produce in a single day thirty-thousand copies of our twelve-hundred page catalogue. We send out between four and five million of these big books per year, and operating this big plant ourselves is another of the reasons we are able to name such low prices.”

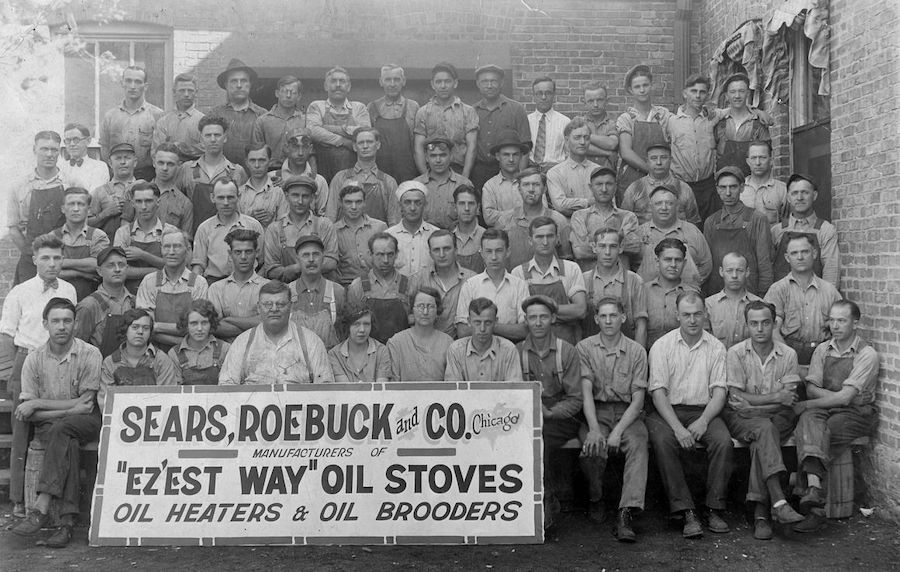

During this same period, Sears also operated a wallpaper mill, a paint factory, and a tent factory within the Lawndale campus; not to mention the camera plant in Minnesota, a half dozen shoe factories in New England, a stove plant in Ohio, and several facilities dedicated to the company’s prefab “Modern Home” division (aka mail order houses!), including a lumber mill in Cairo, IL. As that list continued to grow, Sears Roebuck’s self sufficiency allowed for the occasional extravagance, most evident in the aesthetic flourishes and employee perks that surrounded the Chicago headquarters.

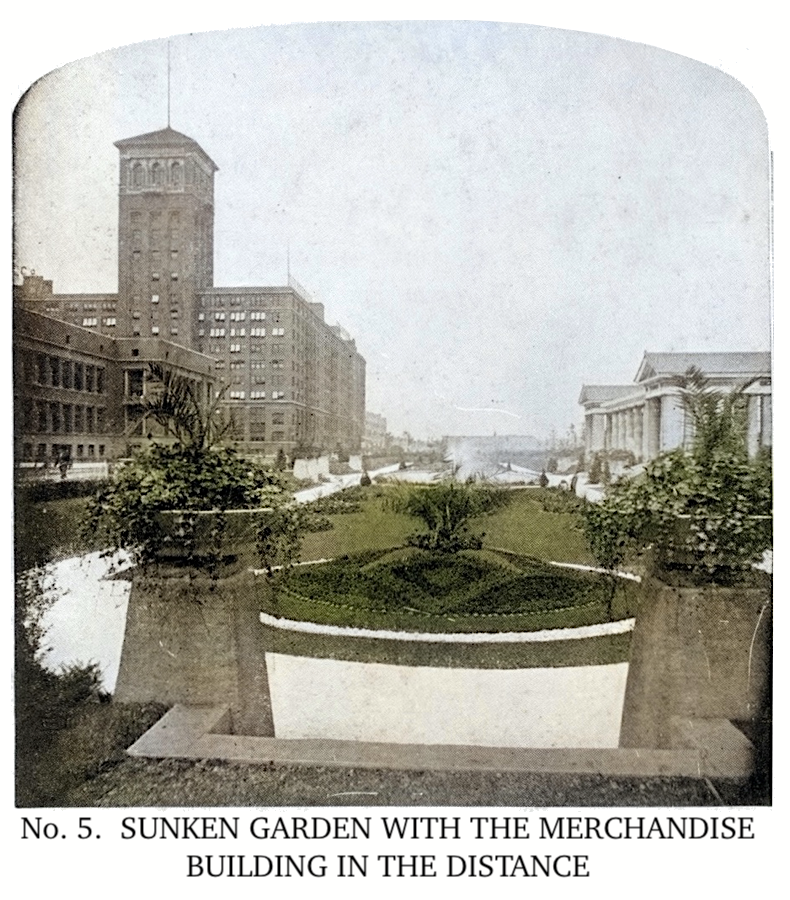

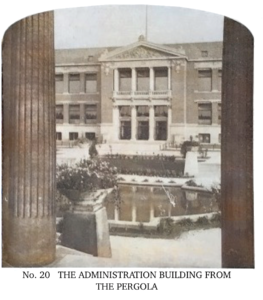

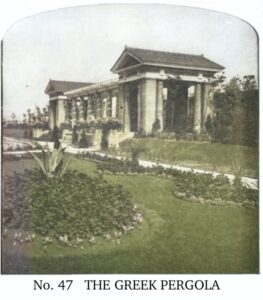

“In front of the Administration Building is a beautiful sunken garden with flowers, shrubbery and trees artistically arranged and labeled with their common and botanical names,” reads the company’s promotional book A Visit to Sears, Roebuck & Co., printed a few years after the Stereoview cards. “In the center of the garden is a vine-clad pergola with a fish and lily pond in the foreground. The remainder of the grounds is devoted to athletic fields, including baseball diamonds and tennis courts.”

“In front of the Administration Building is a beautiful sunken garden with flowers, shrubbery and trees artistically arranged and labeled with their common and botanical names,” reads the company’s promotional book A Visit to Sears, Roebuck & Co., printed a few years after the Stereoview cards. “In the center of the garden is a vine-clad pergola with a fish and lily pond in the foreground. The remainder of the grounds is devoted to athletic fields, including baseball diamonds and tennis courts.”

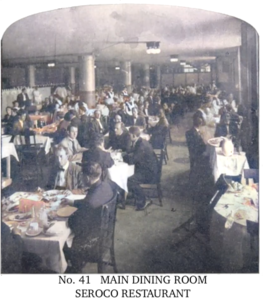

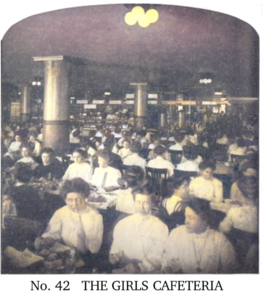

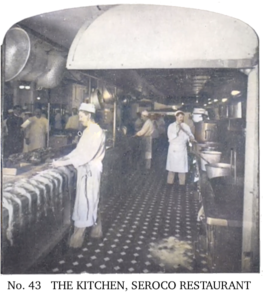

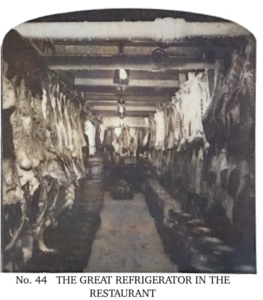

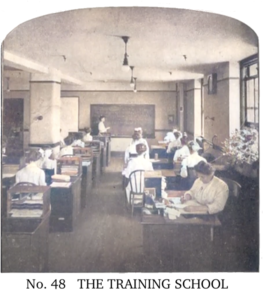

There were plenty of nice things indoors, too, including a 3,000 volume employee library, five restaurants (plus a “girls cafeteria”), a training school, a hospital, and a special sales department dedicated to employee purchases.

Of course, lest it be misunderstood, factory life in the first decade of the 1900s was still far from bliss.

[Group photo of the EIGHT baseball clubs organized among workers at the Sears Chicago plant, c. 1914]

One of the workers toiling in the new plant’s clothing department was a man named Sidney Hillman (1887-1946), later to become one of the most significant labor leaders of his era. In a 1914 testimony before the Commission on Industrial Relations, Hillman recalled working for Sears from 1907-1909, observing the shaky morale among workers who were discouraged from unionizing and often left at the mercy of their bosses.

“In our place we were working about 7,000 girls, ten hours a day,” Hillman recalled. “And before the 10-hour law was passed they used to work three nights a week, getting for remuneration a supper that was paid for by the company in their own restaurant. I believe the girls used to work much harder than the men there.

“In our place we were working about 7,000 girls, ten hours a day,” Hillman recalled. “And before the 10-hour law was passed they used to work three nights a week, getting for remuneration a supper that was paid for by the company in their own restaurant. I believe the girls used to work much harder than the men there.

“I started in with $7 a week, and during three years I worked up to $11 or $12, but what I consider more important is this: the constant fear of the employee being discharged without cause. There really was no cause at all, sometimes. The floor boss, as we called him, did not like a particular girl or a man, and out they went. I remember especially the panic of 1907, when the employees were in constant fear of ‘who will be thrown out?'”

“A Trip Through Sears, Roebuck & Co.” 1908, Colorized Stereoview Card Images #33-50 [Click Any to Enlarge]

Part IV. Business Pure and Simple

“Sell honest merchandise for less money and people will buy. Treat people fairly and honestly and generously and their response will be fair and honest and generous.” —Julius Rosenwald

Serving as Sears Roebuck’s president from 1908 to 1925 and its chairman up until his death in 1932, Julius Rosenwald did more than anyone to establish the company’s general philosophy. While he is an obscure, mostly forgotten figure today, those who have explored his life from a 21st century perspective have often found him to be a severely under-appreciated American do-gooder; particularly in comparison to a lot of the tycoons of his day.

He was the man, after all, who pushed for gardens, training schools, medical care, and restaurants on factory grounds, as well as a revolutionary profit-sharing plan (introduced in 1916) to give workers a better sense of community and long-term security. He was also one of the country’s great philanthropists, boosting up the causes he believed in most, including the city of Chicago (he helped establish the Museum of Science and Industry and gave large sums to the University of Chicago), the Jewish community to which he belonged, and—most uniquely and impactfully—the African-American community.

Even before Rosenwald’s arrival, Sears Roebuck & Co. had already helped improve the quality of life for many black customers, as the mail order catalog provided a new way to circumvent the racial discrimination still rampant in many local retail establishments. Rosenwald, for his part, wanted to go a significant step further in addressing this inequality.

Inspired by discussions with Booker T. Washington, he established the Rosenwald Fund in 1917 to provide seed money for the construction of over 5,000 schools across the South, helping to educate and empower countless disenfranchised children. The program is estimated to have directly served more than one-third of the South’s rural black students and teachers by the end of the 1920s. Rosenwald’s foundation also worked with the Urban League and NAACP and helped establish the first African-American Y.M.C.A. locations.

“Rosenwald’s belief in the chord binding the welfare of Jews and African Americans together defined his life as a Jew in early twentieth-century America,” writes Hasia R. Diner, author of Julius Rosenwald: Repairing the World.

[Colorized photo of the Pee Dee Rosenwald School in Marion County, South Carolina, c. 1930s., courtesy of nps.gov. The majority of Rosenwald Schools fell out of use and into disrepair after desegregation in the 1950s.]

And yet, even with a generous and admirable mensch like Mr. Rosenwald, it’s easy to find details that complicate the narrative a bit. His employee profit-sharing plan, for example, was largely created to weaken the power of the labor unions in the Sears plant, which he considered a menace. And while his empathy for the black community seems thoroughly genuine, Rosenwald wasn’t above expressing his position in a more measured manner to suit a certain audience.

In 1919, when a reporter for a trade magazine asked why he gave “all this money to the negroes,” Rosenwald responded: “Simply to help the whites. That’s all there is to it—a plain, simple business proposition of helping the white people of this country. If you persist in kicking a man into the gutter all the time, you have to stay down at his level or you can’t kick him. If you try to rise without taking him with you he will be a drag on your progress. I have helped the negroes simply to help the whites, and I think that is a very good and sufficient reason.”

In the same interview, Rosenwald—who was 57 at the time—downplayed the motivations behind all those Sears Roebuck employee perks, as well, offering a blunt explanation that seems more in line with Sidney Hillman’s cold assessment.

“We have about 25,000 employees,” he said. “Naturally among these are quite a number of thousands of girls. Suppose a girl is ill. Is it better to send her home and thus lose her entire day’s work, or is it more profitable from our standpoint to have facilities for giving her proper medical attention and give her a place to rest until she recovers or feels better? In this way, perhaps, half the girl’s services may be saved to us during the day. Multiply this by several hundred—which is just about average day’s activity— and you will see the reason. . . . It is all a matter of business with us, and we are not in the slightest degree backward about making that fact plain to our employees. We have no high-sounding theories here. There is nothing about our system that involves professional sociology in the slightest degree. It is business pure and simple.”

Interestingly, Sears Roebuck did become quite invested in sociology after Rosenwald’s death, launching an “employee attitude survey program” in 1938. The data the company collected proved quite enlightening both to executives and academic researchers over the next few decades, but its purpose was single-minded: to stop workers from organizing and to bust up unions. It wasn’t always successful; labor strikes became more common in Sears’s retail store years. There were also occasional boycotts from African-American groups over racist hiring practices and customer service biases at the company. Despite Julius Rosenwald’s more noble efforts, capitalism and progressivism remained difficult bedfellows.

[Workers strike against unfair labor practices at Sears, 1967]

Part V. The Store

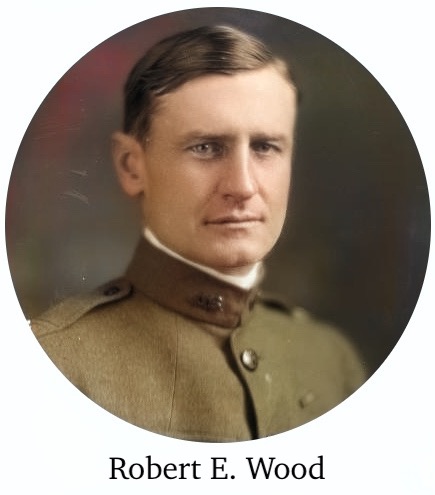

Among Julius Rosenwald’s last acts before retiring from the presidency were the launch of the WLS radio station (“World’s Largest Store”) in 1924, and the opening of the company’s first brick-and-mortar retail store—located on the Chicago factory campus—in 1925. During this same period, he hired the former vice president of Montgomery Ward, a square-jawed brigadier general named Robert E. Wood (b. 1879), to take on the same role at Sears. At the time, Montgomery Ward had been making considerable gains in the mail-order market while Sears had started to flounder.

Once Rosenwald announced he’d be stepping down, Wood hoped to grab the reins, but the line of succession was complicated and contentious. Rosenwald’s son Lessing was in the mix, as were longtime VPs Max Adler (eventual founder of Chicago’s Adler Planetarium) and Otto Doering. Rosenwald ultimately went with a wild card, Charles M. Kittle—a big wig with the Illinois Central Railroad. But after Kittle’s untimely death in 1928, Wood was finally handed the keys. He was younger than Doering and Adler and hadn’t made his millions yet—Rosenwald figured that would make him more motivated to earn his proverbial stripes.

Once Rosenwald announced he’d be stepping down, Wood hoped to grab the reins, but the line of succession was complicated and contentious. Rosenwald’s son Lessing was in the mix, as were longtime VPs Max Adler (eventual founder of Chicago’s Adler Planetarium) and Otto Doering. Rosenwald ultimately went with a wild card, Charles M. Kittle—a big wig with the Illinois Central Railroad. But after Kittle’s untimely death in 1928, Wood was finally handed the keys. He was younger than Doering and Adler and hadn’t made his millions yet—Rosenwald figured that would make him more motivated to earn his proverbial stripes.

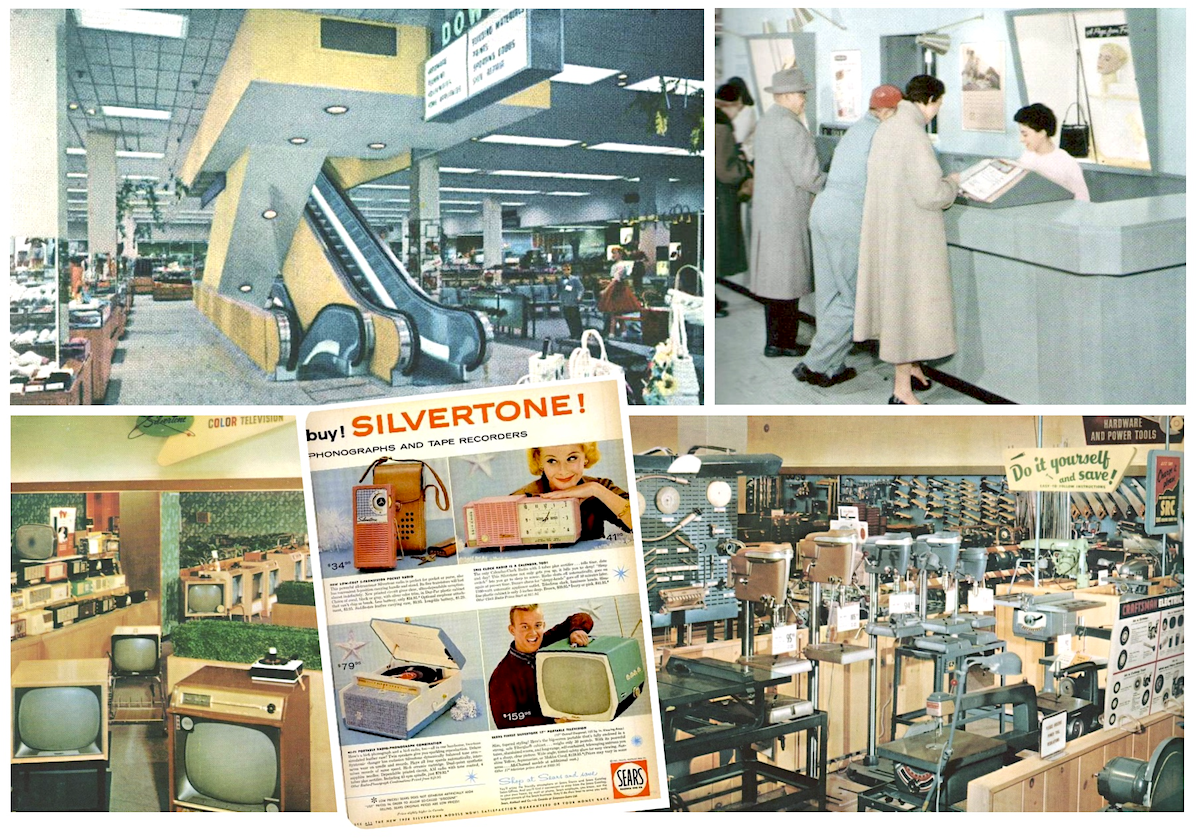

Wood had already played an active role with Kittle in pushing Sears into the retail world in the late 1920s, and as president, he pressed on the gas even more. By 1929, there were 300 Sears retail stores across the country, accounting for 40% of the company’s overall business; two years later, the stores outsold the mail orders for the first time. By now, Sears had also outsourced the printing of its famous catalogs (first to the Cuneo Press, then R. R. Donnelly & Sons). It was a dramatic shift in focus and expectations for the business, not unlike “talkies” replacing silent film during the same period.

The onset of the Great Depression was a big shift of a whole other kind, but Robert Wood largely stuck to his vision during the economic pinch, recognizing—before most of his competitors—that department stores needed to evolve. With more and more families owning automobiles, it was no longer necessary to battle for expensive downtown real estate, nor did Sears need to emulate the fancier furnishings and posh vibe of a Marshall Field. Instead, Wood saw his stores more like military commissaries—offering a simple and “masculine” shopping experience, built around the same popular lines customers already trusted from the Sears catalogs: hardware, farm gear, sporting goods, auto parts, etc. Consequently, as more families got their tires and spark plugs at Sears, Wood wisely came up with a scheme to start offering customers insurance packages, too, under the name of Allstate.

[Above: Newspaper clippings from Lansing, Michigan (left) and Pittsburgh, PA (right) announcing the imminent openings of new, local Sears Roebuck retail stores, both in 1929. Below: Exterior view of a Sears store and parking lot in Phoenix, AZ, 1950s.]

For all its influence as a national retail superpower, Sears remained somewhat overlooked as a manufacturer—or, at least, as a manager of a manufacturing empire. Stronger relationships were developed with designated suppliers across all fields during General Wood’s reign, and Sears reps “participated actively in the design of many of the products it sold,” according to Raff and Temin. “The buyers worked with the manufacturer to create a product that the buyer could sell and that would fit in with other products the buyer was handling. Sears created a testing laboratory to help this process by evaluating new products and providing a mechanism to introduce new ideas and further modifications.”

Sears customers came to recognize and trust the store’s various in-house brand names, like Craftsman tools, Kenmore washing machines, and Silvertone radios and guitars, but the products carrying those names were often produced by dozens of different manufacturers, leaving a mighty complicated paper trail for modern day historians and collectors to follow.

[1950s Sears Store Interiors]

Part VI. Knocks On Wood

Through most of the 1930s, Lessing Rosenwald—Julius’s son—was the company chairman, but he lived in Philadelphia and was content to let Robert Wood run Sears Roebuck’s affairs in Chicago. By 1939, he’d handed off the chairmanship to Wood, as well.

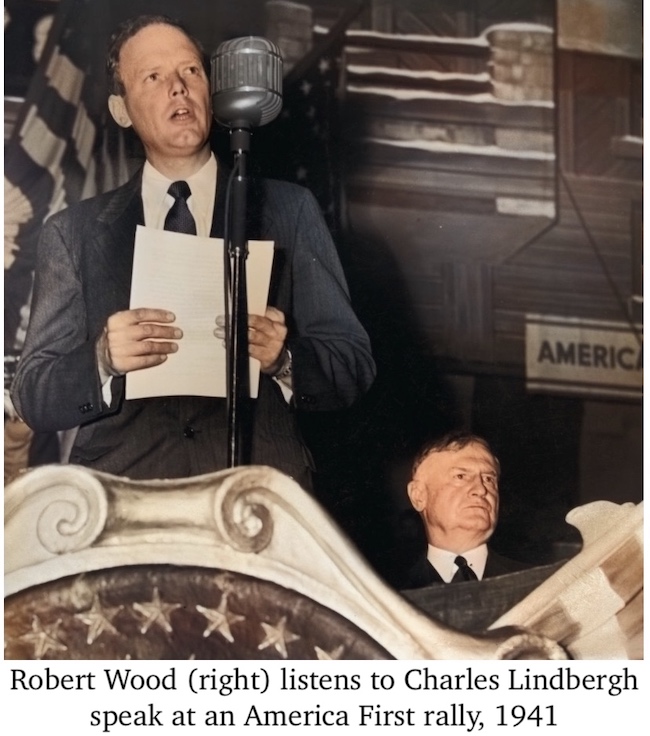

While objectively successful and influential, Wood, aka “The General,” wasn’t popular with everybody, and his attitudes and politics haven’t aged as well as those of Julius Rosenwald. A West Point grad and a staunch conservative Republican, Wood loudly espoused a position of isolationism for the United States before its entry into World War II. Toward that end, he became one of the biggest financiers of the infamous America First Committee—which ultimately devolved into an anti-semitic, Nazi-sympathizing embarrassment under the leadership of the famed aviator Charles Lindbergh.

Wood wouldn’t associate himself with those uglier elements of the America First movement; his motivations were purely financial, he said. Even so, his views on Jews and African Americans were known to be less than evolved, and former cohorts like Lessing Rosenwald and Max Adler never fully forgave him for not disavowing Lindbergh’s propaganda early on.

Wood wouldn’t associate himself with those uglier elements of the America First movement; his motivations were purely financial, he said. Even so, his views on Jews and African Americans were known to be less than evolved, and former cohorts like Lessing Rosenwald and Max Adler never fully forgave him for not disavowing Lindbergh’s propaganda early on.

Nonetheless, Robert Wood carried on as Sears’s supreme leader during the war and won his biggest victories for capitalism in the years immediately after. As he had during the Depression, Wood correctly anticipated changes in the population and its buying habits in peacetime, and rather than playing it safe like arch rival Montgomery Ward, Sears poured $300 million into new store openings and renovations in the late 1940s.

“When World War II ended, Sears ranked only slightly ahead of Montgomery Ward,” John Oharenko writes in his book. “When Wood retired in 1954, Sears’s $3 billion in sales was triple that of its rival. A little more than a decade later, Sears became the largest retailer in the world and the first to hit $1 billion in monthly sales.”

In 1977, author Gordon Weil wrote that “the postwar expansion, Wood’s last great contribution to the company of Richard Sears and Julius Rosenwald, made Sears what it remains today—one of the giants of the American economy.” Weil also acknowledged that Wood often couldn’t get out of his own way, as evidenced by his vocal support of Senator Joseph McCarthy’s Communist witch hunts in the 1950s. As a businessman, though, “he was always willing to shun orthodoxy in favor of the bold move; and, like Sears and Rosenwald, he regarded the company as an extension of himself.”

Part VII. From Great Heights . . .

As most people know, Sears’s next 60 years didn’t go as well as its first 60, although growth actually continued well after Robert Wood and the “old guard” had departed.

After leaving Homan Square for the new Sears Tower mega-skyscraper in 1973, the company was still producing 15 million copies of its hefty main catalog, five times a year, along with 300 million editions of its specialty and tabloid catalogs. Most of these were now outsourced to another Chicago printing firm, R. R. Donnelley, but Sears was, by some standards, still the largest publisher in America, on top of being its biggest retailer.

When Gordon Weil was writing about the Sears legacy and visiting the new Sears Tower in 1977, he noted that “Out of every 204 working people in the United States, one works for Sears,” and that “its sales represent 1 percent of the entire gross national product.” The company didn’t sell handguns, cigarettes, or booze, and the catalog had since jettisoned cars and prefab houses, but beyond that, just about everything was still available in-store or inside the “big book.”

When Gordon Weil was writing about the Sears legacy and visiting the new Sears Tower in 1977, he noted that “Out of every 204 working people in the United States, one works for Sears,” and that “its sales represent 1 percent of the entire gross national product.” The company didn’t sell handguns, cigarettes, or booze, and the catalog had since jettisoned cars and prefab houses, but beyond that, just about everything was still available in-store or inside the “big book.”

At the same time, Weil observed the obvious cracks in the Sears armor—its run-ins with the Federal Trade Commission for ethics violations; the lack of any women or ethnic minorities (including Jews) in its current leadership. The company had been the “king of the mountain” for nine decades, Weil wrote. “That is a dangerous and difficult place to be.”

Sure enough, even from the height of a 108-story headquarters, the leaders of Sears, Roebuck & Company during the ‘70s, ‘80s, and ‘90s couldn’t see the future quite as skillfully as Richard Sears, Julius Rosenwald, and Robert Wood once had.

“In retrospect, it seems clear that by the late 1970s Sears’s earnings growth had essentially flattened out,” Raff and Temin wrote. “There had been decades of boom since the move into retailing, but now they seemed to be over.”

As Wal-Mart and K-Mart surpassed Sears as retail kings in the 1980s, and other more specialized shopping mall stores grabbed their shares of the market, Sears found itself victimized by the same sort of advanced technology and data evolution that had made their own Homan Square plant a wonder of the industrial world back in the early part of the century.

“If Sears had rethought its internal operations and taken advantage of some of the progress of technology since Rosenwald’s distribution plant was built,” Raff and Temin surmised, “it might have been able to maintain its traditional economies of operation into new decades.”

Even Raff and Temin’s analysis, written in 1999, doesn’t foresee Amazon and the further failure of Sears to grab any significant power as an online entity in the 21st century.

Of course, it’s easy enough to play Monday morning quarterback, lazily presuming anybody else would have seen the iceberg looming in the darkness. So it’s probably better to just mention the facts.

Sears, which is still headquartered today in nearby Hoffman Estates, IL, was forced to file Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2018 and eventually cut its fleet of retail Sears stores down to less than 250, with gradual closures of many of those surviving stores announced throughout the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021. The company’s last big print catalog was mailed out in 1993, around the same time it moved its offices out of the Sears Tower . . . which subsequently was re-christened the Willis Tower in 2009.

Sears, which is still headquartered today in nearby Hoffman Estates, IL, was forced to file Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2018 and eventually cut its fleet of retail Sears stores down to less than 250, with gradual closures of many of those surviving stores announced throughout the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021. The company’s last big print catalog was mailed out in 1993, around the same time it moved its offices out of the Sears Tower . . . which subsequently was re-christened the Willis Tower in 2009.

Whatever the company’s ultimate fate may be, it will always be worthwhile to look back at how its leaders built an international retail model never seen before, setting up an entire culture of front porch and parking lot consumerism. It’s also worth remembering that none of their efforts or grand plans would have amounted to anything without the sweat and energy of hundreds of thousands of employees; a large portion of them underpaid women and minorities. From the grand scope of the old Chicago plant to every Sears retail space in small-town shopping malls, 100 years of success relied on individuals as much as statistical analysis. It’s something to remember if you ever visit Homan Square’s original Sears Tower; a monument to big ideas and the Chicago workers who brought them to life.

[Renovation of the original Sears Tower, now the Nichols Tower. Event photos by Eric Allix Rogers]

[Renovation of the original Sears Tower, now the Nichols Tower. Event photos by Eric Allix Rogers]

[The printing block above, circa 1910s, came to the Made In Chicago Museum in 2021 all the way from the small town of Heckmondwike in West Yorkshire, England. Brian Battye, who donated the block, said he found it while cleaning out the offices of Illingworth Bros., his family’s century-old printing and stationery business. The block still produces a fine image (as seen on the right), advertising “Automobile, Carriage and Traveling Robes,” which were used to keep people warm in the unheated vehicles of the early 20th century]

[Workers at Sears’s “Ez’Est-Way” Oil Stove factory in Kankaee, Illinois, 1920s. Courtesy Kankakee County Museum.]

[Women in the Sears Entry Department using Chicago-made Oliver typewriters, c. 1914]

Research Sources:

Images of America: Historic Sears, Roebuck and Co. Catalog Plant, by John Oharenko with the Homan Arthington Foundation, 2005

Sears, Roebuck, U.S.A.: The Great American Catalog Store and How It Grew, by Gordon L. Weil, 1977

Shaping an American Institution: Robert E. Wood and Sears, Roebuck, by James C. Worthy, 1984

A Visit to Sears, Roebuck & Co., 1914

Final Report and Testimony Submitted to Congress by the Commission on Industrial Relations, August 23, 1916

“Build Up Your Employes” – American Wool and Cotton Reporter, Nov. 6, 1919

“A Brief History of Conley Camera Co.” – sevenels.net

“Employee Attitude Testing at Sears, Roebuck & Co.,” by Sanford M. Jacoby, The Business History Review, Vol. 60, No. 4, 1986

“The Great Set of the Great Plant” – Stereoworld, July/August 1998

“Sears, Roebuck in the Twentieth Century: Competition, Complementarities, and the Problem of Wasting Assets,” by Daniel Raff and Peter Temin, 1999

Julius Rosenwald: The Man Who Built Sears, Roebuck and Advanced the Cause of Black Education in the American South, by Peter M. Ascoli, 2006

“The Rise and Fall of Sears” – Smithsonian Magazine, July 25, 2017

Julius Rosenwald: Repairing the World, by Hasia R. Diner, 2017

“The Incredible Shrinking Sears” – New York Times, Aug 11, 2017

“Goodbye to Sears” – Daily Journal (Kankakee, IL), Feb 18, 2018

“Catalogs Undercut Jim Crow” – Washington Post, Oct 18, 2018

“The Achievements Behind America’s Great Philanthropist” – Philanthropy Daily, April 11, 2019

Chicagology – A Trip Through Sears, Roebuck & Co.

My father in law purchased a boat kit in the early 1930s and I have restored it is there a place it can go where other Sears items are like a museum where I can ship it?

My grandfather Watson Barger worked in Sears and ran the catalog department for years. He retired from Sears..

What about Disney’s introduction into the Chicago market of Winnie the Pooh first franchised in about 1964. Disney died in 1966

Hello, I have a 1908 hard copy Sears and roebuck catalog. The binder is very warn and loose. It was my Great grandma’s. And I would love to see it in a showcase somewhere, where other people could enjoy it. Is there such a place? Can’t wait to hear from you. Thank you!

I recently was given a dresser made by Sears I’m guessing sometime between the 1920s and the 1940s it does have a shipping label on it but parts that I need to not be made out such as the date there is a serial number 3434 x I was just hoping to get more information on it. I have searched the web quite extensively looking for one like it and have not had any luck I have tried searching the Sears sites and calling not getting anyone I had to call from Wisconsin to Kansas to a store to just ask a person that answers the phone if they could direct me to a number or website with archives and they were not able to do that so I’m hoping you could help me. Thank you for your time

I am looking for a replacement spark plug for a Sears and Roebuck / David Bradley Roto Spader I am restoring. Model no. 107120 I believe that it’s a 1955 model. Any help with a number would be highly appreciated.

Is there a museum that items can be donated to? My husband was nation vp of store operations and worked for Sears for over 30 years. He designed the cash register they used in the late eighties/early nineties. I have a model of the cash register as well as other memorabilia.

I have a bicycle that my Dad purchased through the Sears Roebuck catalog in the 1950s. She learned to ride it and then later I inherited it. Would anybody be interested in it before it is put out to pasture. I also have a picture of my sister on it. Thanks

Back in 1955 my mother took me from Boston to visit an older distant cousin in Canton, OH. Turns out that their home had been built from a Sears & Roebuck “kit.” It was a sturdy home in just about every respect that I can now recall. “Uncle” had built a small bathroom off the kitchen for “Auntie” to use because she had difficulty negotiating stairs.

Is there a place that collects and displays old sears tools?

I have a model of sears and Roebuck home that they have on display in their office It shows two different fronts of how the house can be built.