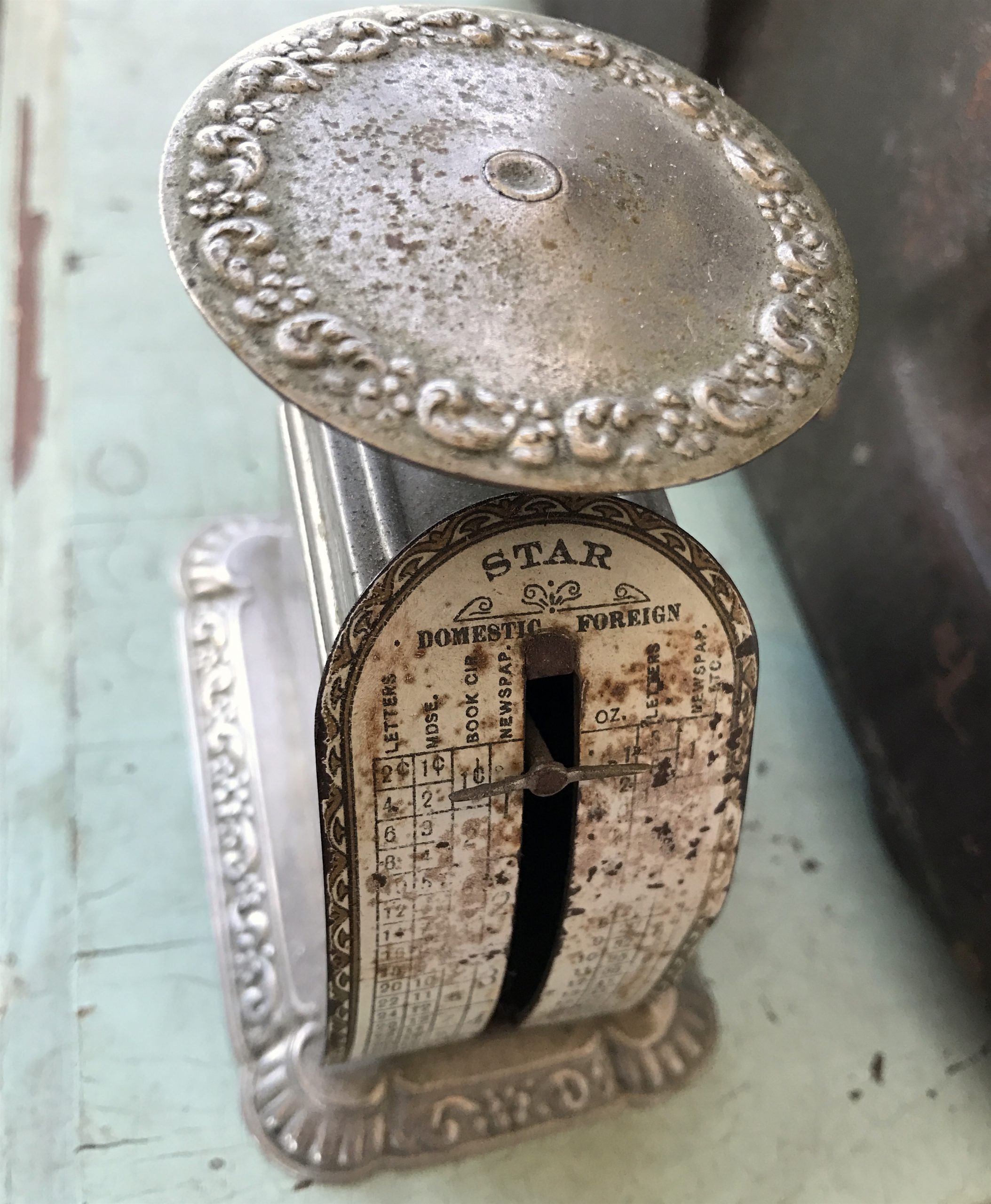

Museum Artifact: Pelouze “Star” Miniature Postal Scale., c. 1900

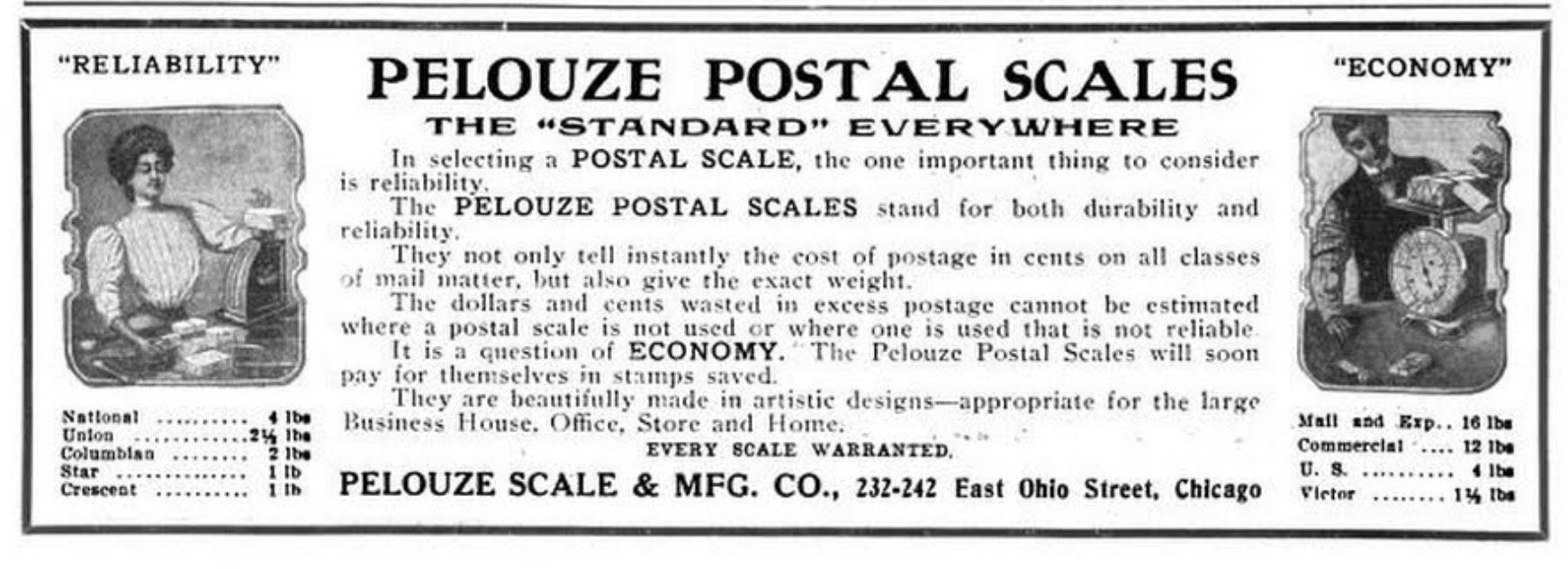

Made By: Pelouze Scale & MFG Co., 133 S. Clinton St. / 118 W. Jackson Blvd. / 232 E. Ohio St., Chicago, IL

Considering Chicago was the unofficial spring-scale capital of the world, the Pelouze Scale & Manufacturing Company had no shortage of competition in its industry. Even our own museum collection includes quality offerings from Pelouze contemporaries like the American Cutlery Co., Triner, and Hanson Brothers. In the categories of power, money, and influence, however, very few manufacturers—of scales or anything else—could challenge the Pelouze name.

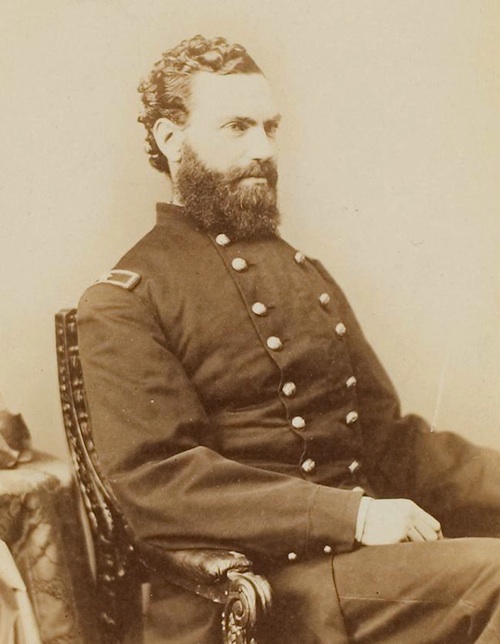

The company was founded in 1894 by William Nelson Pelouze, who—at the age of 29—was already a man of significant stature in Chicago society. He came from one of the more esteemed military families in the country; the son of Louis Henri Pelouze II—a decorated Civil War veteran and Army General who’d stood watch at Abraham Lincoln’s deathbed. The general died in 1878 when William was just 13, but if the son had any doubts about living up to his dad’s reputation, he certainly never seemed to show it.

William, his older brother Louis Pelouze III, and his younger brother Frederick all attended the Michigan Military Academy in Oakland County—a short-lived “West Point of the Midwest.” Within two years of graduating as the standout of his class in 1882, William Nelson Pelouze made his way to Chicago; got work with the Walter A. Wood Mowing and Reaping Machine Company; was elected Captain of Company H of the Illinois National Guard; and married one of Chicago’s most sought after debutantes, Helen Gale Thompson—daughter of the real estate mogul William Hale Thompson, and sister to budding politician William “Big Bill” Thompson, Jr. (future corrupt mayor of Chicago).

The growing influence of the Pelouze name was having some surprising consequences back in Michigan, too, where William’s older brother Louis III—while goofing around with some local Detroit amateur baseball clubs—somehow found his way into an official Major League game. On July 24, 1886, Louis Pelouze [pictured below] stepped in as a replacement outfielder for the St. Louis Maroons, tallying three at-bats in a Saturday afternoon game against the Detroit Wolverines. He struck out twice, made four putouts in the outfield, and never again appeared in a single game at the pro level. Incredibly, this Moonlight Graham moment for Louis Pelouze III was enough to warrant him having his own Wikipedia page today, whereas his father—the great military general whom Lincoln himself held in high regard—hasn’t proven worthy of such an internet honor. Baseball > War.

By 1891, Louis III had given up his baseball dreams and decided to take a page out of his little brother William’s book instead, marrying a filthy rich girl, also named Helen. This time it was Helen Ward, daughter of the richest man in Michigan. Louis Pelouze went on to became a diamond broker in New York City, and he and Helen lived out their days on Park Avenue.

Youngest Pelouze brother Frederick, meanwhile, eventually came up to Chicago to join William’s fledgling business venture, the Pelouze Scale & Manufacturing Company. William had developed an interest in postal scales while working for Chicago’s Tobey Furniture Company, and in 1894, he was ready to go solo with the idea. That same year, the 1st Brigade of the Illinois National Guard elevated William to the rank of Assistant Adjutant General—the same military rank his late father had once held. As a guardsman, William Nelson Pelouze wound up on the front lines of many of Chicago’s most infamous and violent labor conflicts, including the Union Stock Yards riots and the Pullman Strike. These experiences created what would become a lifelong dislike for all unions and, seemingly, most leftwing politics.

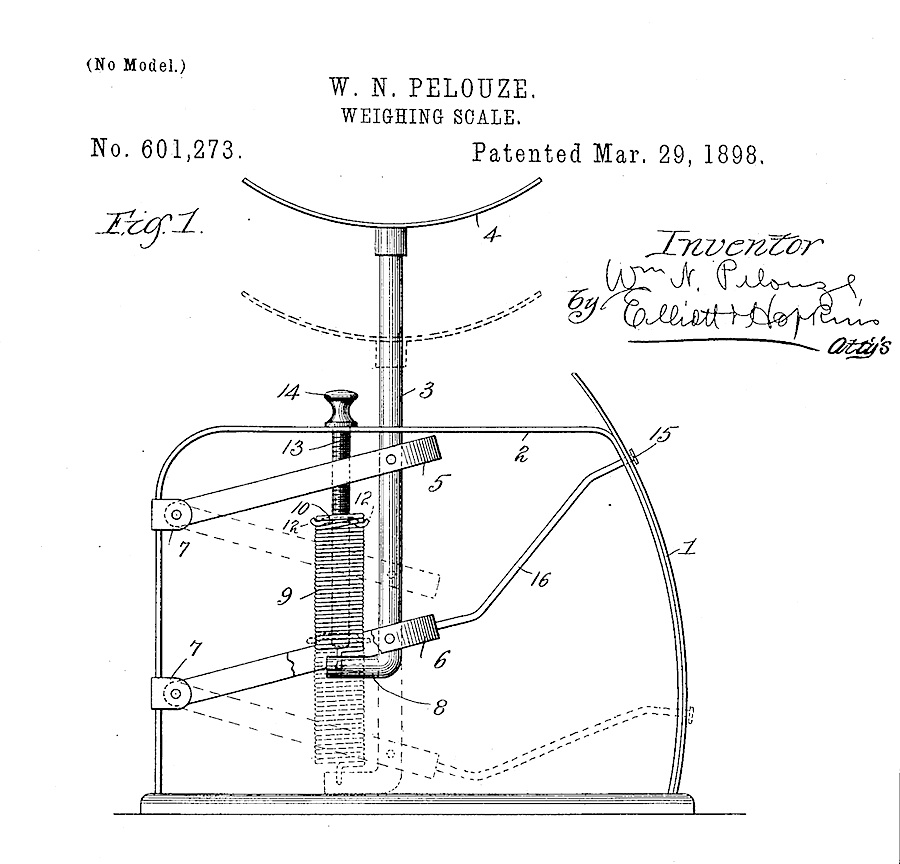

After a brief detour to serve in the Spanish-American War in 1898, W.N. Pelouze returned to Chicago and quickly guided his scale company to major international success, refining some of his patents—like the one below—to create popular lines of Pelouze postal scales, including the miniature, turn-of-the-century “Star” scale in our collection.

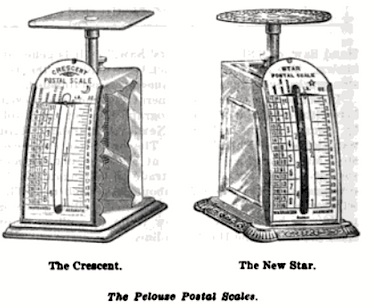

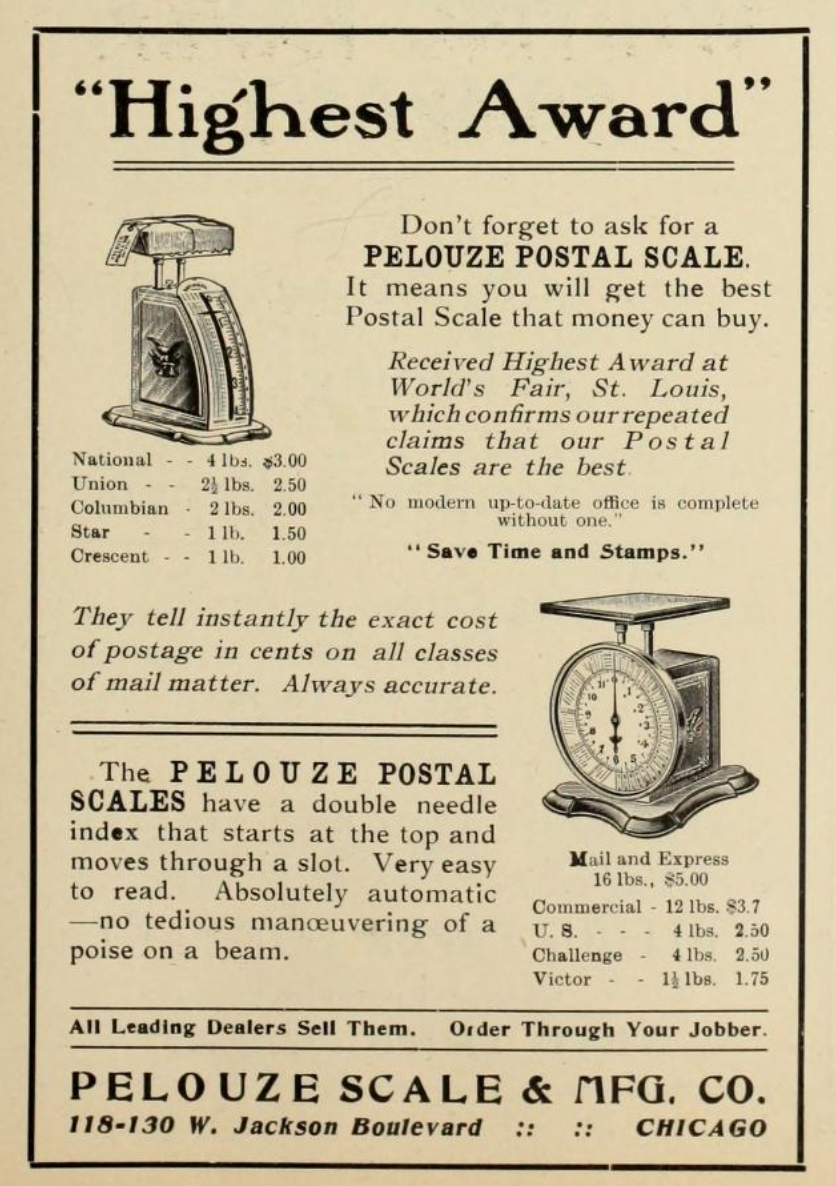

In 1901, Pelouze moved his business from its stuffy first location at 135 S. Clinton Street to bigger digs at 118-132 West Jackson Blvd. The advertisement below dates from two years later, 1903, and shows our exact model of the 1 LB “Star” postal scale along with a similar model, “The Crescent.” The 1903 Star scale was a redesign of the original 1899 version, and introduced paneled sides and embossed base and tops plates, which you can see in our museum piece. This scale sold for $1.50 at the time, which would be somewhere in the $40-50 range today.

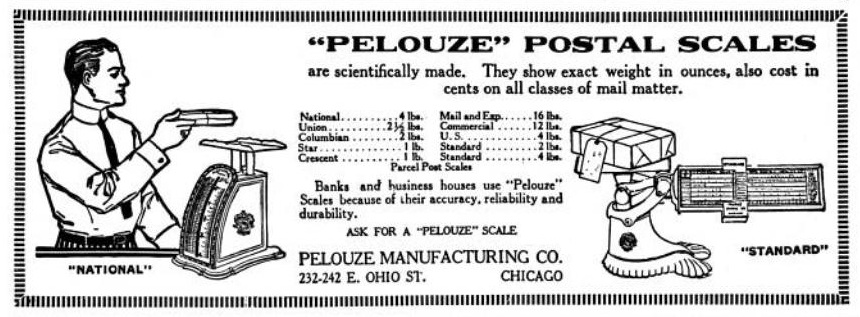

The popular response to the original Pelouze postal scales eventually inspired expansion into family scales, dairy scales, confectionary scales, and other varieties. When those started selling well through mail order services, William tested his luck by launching a second business in 1908—the Pelouze Heating Company—to gain a foothold in the new electric appliance market. This venture proved to be yet another homerun (with apologies to Louis III), and within a few years, William decided to merge his two companies back into one—forming the Pelouze Manufacturing Company. By now, the rich were getting much, much richer, and William Nelson Pelouze, his wife Helen, and his brother-in-law “Big Bill” were at the top of the Windy City food chain.

Along with holding court in every yacht club, dinner club, and generic high society function in town, William Nelson Pelouze was right there in the thick of building what would become the 20th century version of Chicago. In 1909, he was part of the executive committee helping to set Daniel Burnham’s famed “Plan for Chicago” in motion—one of the nation’s first, comprehensive city-planning initiatives. Pelouze also championed the St. Lawrence Seaway as chairman of the Illinois Deep Waterway Commission, and became the president of the Illinois Manufacturers Association. By 1920, his brother-in-law was the freaking mayor, and William himself had been appointed the new colonel of the Illinois Reserve Militia’s First Infantry, as selected by the governor’s office. And yet… rather than rely on local government to get things done, Pelouze consistently preferred the more direct route of corporate might in the private sector.

When Pelouze became president of the Illinois Manufacturers Association, he used it to promote the “Open Shop” movement—an anti-union, anti-Socialist agenda he described as a “defense of the American Plan.” He brought a similar conservative perspective to his role as the first president of the Association of Arts and Industries, a position he held from 1922 to 1936. Here, he was a champion of the industrial arts—noting the important role of good design in American manufacturing and architecture—while simultaneously becoming a sort of public enemy No. 1 for the local art community, which consistently butted heads with Pelouze on the direction of the organization. Where William saw a system for producing capable, by-the-books designers for the industrial workforce, some of his cohorts from the Art Institute of Chicago had grander ideas about design as an individual art form.

Still, to pigeon-hole William Nelson Pelouze as some sort of close-minded curmudgeon—or an empathy-lacking elitist—would be quite unfair. For years, he worked diligently to get jobs programs set up for military veterans, and he was also one of the most important figures in keeping Chicago’s coastline a free space for public use.

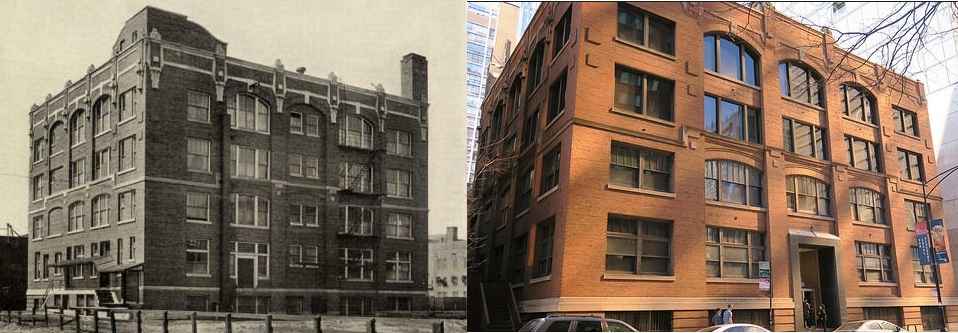

In 1916, Pelouze commissioned a new office building to be built directly beside one of his main factory locations at 232 E. Ohio Street in the Streeterville neighborhood. The new facility, designed by Alfred S. Alschuler, was built to function as a potential factory space itself, with high ceilings, freight elevators, thick floors, etc. But Pelouze decided that using the building as a public space—for offices, studios, and large residential units—would stay more true to Daniel Burnham’s vision for this part of town. Within a few years, the Pelouze Building at 230 E. Ohio Street had set a new trend for architecture in the area, perhaps even marking the point where “industrial” transitioned from a purely functional style to an aesthetic one. Both the 232 and 230 Pelouze buildings on East Ohio Street are, amazingly enough, still standing as historical landmarks.

[The original Pelouze factory at 232 E. Ohio Street, c. 1915 and 2015]

[The original Pelouze factory at 232 E. Ohio Street, c. 1915 and 2015]

During the same year the Pelouze Building was commissioned, William and his wife made headlines by adopting a baby daughter, Medora, whom the Colonel described in a 1916 issue of Geyer’s Stationer:

“She’s the dearest little thing, and such a dainty little miss. She loves to sit in the flower patches and nibble the white petals of the beautiful daisies. She smiles all day long and pulls her daddy’s hair with her chubby little fist.”

Yes, that’s millionaire industrialist, postal scale magnate, and union-hating yacht clubber William Nelson Pelouze, saying just about the cutest shit you’ve ever heard. The man seemed to have a general love not only for his family, but his adopted hometown, and Chicago likely wouldn’t look quite the same today without him.

Pelouze died in 1943 at his family’s swank estate in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. He was 77, and still serving as president of the Pelouze Manufacturing Company.

A year after losing her husband, Helen Gale Pelouze lost her brother, too—the ex-Mayor Thompson—who had by now become one of the most hated men in Illinois. Only a handful of people attended Thompson’s funeral. The loud-mouthed, wildly corrupt ex-mayor (a favorite of Al Capone) still remains the last Republican mayor of Chicago.

As for the Pelouze brand, it carries on to this to this day, under the ownership of Rubbermaid, which is owned by some other company itself, which is probably owned by one of the five companies that owns everything. Today’s electronic Pelouze scales, unfortunately, lack some of that industrial arts aesthetic that still makes the original models easy on the eye.

Along with the tiny Pelouze postal scale featured on this page, we also have a pair of later Pelouze family scales in the museum collection, as well, each dating from probably the 1930s or ‘40s. You can check them out below, or just scroll down to see more photos and/or leave a comment.

Other Pelouze Scales in the Made In Chicago Museum Collection

(Click Image for More Info)

Additional Images of the Pelouze Star Scale & Other Stuff:

[Civil War Brigadier General Louis Pelouze, father of company founder William Nelson Pelouze]

[Civil War Brigadier General Louis Pelouze, father of company founder William Nelson Pelouze]

[The Pelouze Building at 230 E. Ohio Street, built in 1916]

[The Pelouze Building at 230 E. Ohio Street, built in 1916]

Additional Sources:

The Old Guard and the Avant-Garde: Modernism in Chicago, 1910-1940, edited by Sue Ann Prince

Archived Reader Comments:

“Walked past the 230 E. Ohio building thousands of times while working next door at Chicago Recording Co. and had no idea of the buildings history, thanks for this info!” —Marc, 2019

“I love your site! Thank you so much for the information on Pelouze scales. I have a Pelouze Family Scale 24 lbs with patent dates of Mar 29 ’98, Dec 27 ’98, and Mar 14 ’99 (plus “pats pend”) that’s been in my family for years (probably since 1899). It’s very rusty and gnarly looking but still works great — my go-to scale for everything, in spite of having a much newer fancier cleaner streamlined Soehnle. I would love to clean this Pelouze scale a little, though. Any suggestions? I don’t want to ruin it! Thanks again.” –-Eleanor, 2018

Hi. I bought a pelouze mfg scale at a garage sale. I can’t find any like it, I have researched. It is a 4 lb brass scale and the pan is the scoop pan, not flat. Stamped dates on bottom are 1896, 1898, 1903, 1903.

Your website is great, but I have yet to even find a photo of my scale. Any info would be great. My number is 815-858-0370 in case you want to call. I know there isn’t great value but I would love the history of it.

Thank you!

I have a 2 pound Pelouze candy scale with the removable bowl. This came from my father’s estate. He grew up working in drug stores as a young man and eventually became a pharmacist in Detroit. I don’t know when he acquired it.

The patent date on the scale is 1913. Would you like this for your museum? Please reach out to me with an address to send it to if you would.

I am a member of the Illinois Army National Guard and I have an old Pelouse scale, it’s about 7 3/4 in lg, tube design with an interior spring and a wire along the outside that extends the length of the scale. This is a military application and I am just trying to figure out exactly what this is.

dear Sirs I collect old farm related items .At a recent auction I bought A Steel king Ice Balance scale 300# The ones that I see on ebay have a patent date .My scale says patent applied for . What year would that be Thank Ron

What about Pelouze toasters. They are rather rare and quite interesting.

I have a model 1060 , temperature compensating 60 pound scale, any specific info appreciated! What was it’s primary purpose? Still postal ?? Barn find, I cleaned oiled and have working once again

Carl

I have a Pelouze Model PE5R postal scale that is no longer w0rking,do you know where I can send it to be repaired or replaced?

Thank you for any assistance!

Sincerely,

Alton G. Hudson

alhudson447@yahoo,com

I have a Pelouze postal scale, model #P2, is it possible to get updates for the scale “rates dial”.

I have a PE5R scale. The connections to the battery rusted out. Can I send it in to be fixed?

Is there a web source for Pelouze catalogues or trade journals that might help me establish the dates of production for a 2lb Supreme candy scale that has a 1915 patent date on the front of the 5-to-60 cent sliding calculator and two patent dates (1915 and 1927) on the reverse of the calculator?

If possible could I please have the dates of manufacturing for the Gajit? 4″ hem ruler. I want to pass this on with as much info as possible.

thank you

Jeanne

I have a very nice Hang weight Pelouze scale that I have out for sale. Would the museum perhaps want to acquire it?

On a Pelouze 4010, is there a way to change the default reading from lbs. to Kgs?

I live in Canada & we switched to Metric 40 years ago.

Thanks,

Al Brisco

I have a YG180R Pelouze scale with a green sticker bearing the serial # 1200000091, Date Code: 5004. Made in China. Could you please decipher the date code?

Not definite, but it was common for many manufacturers to use week/year combinations on date codes. It could very well be the 5004 would mean 50th week in 2004. I would say it would be 2004 though.

I have a pelouze Postal Rate Computing Digital scale since 1978. Recently, the 9v battery won’t work in it. I would like to secure an AC adapter for it but I can’t find one that will fit. Can you help me? I love my scale.

Thank you,

Walter Smith, Jr.