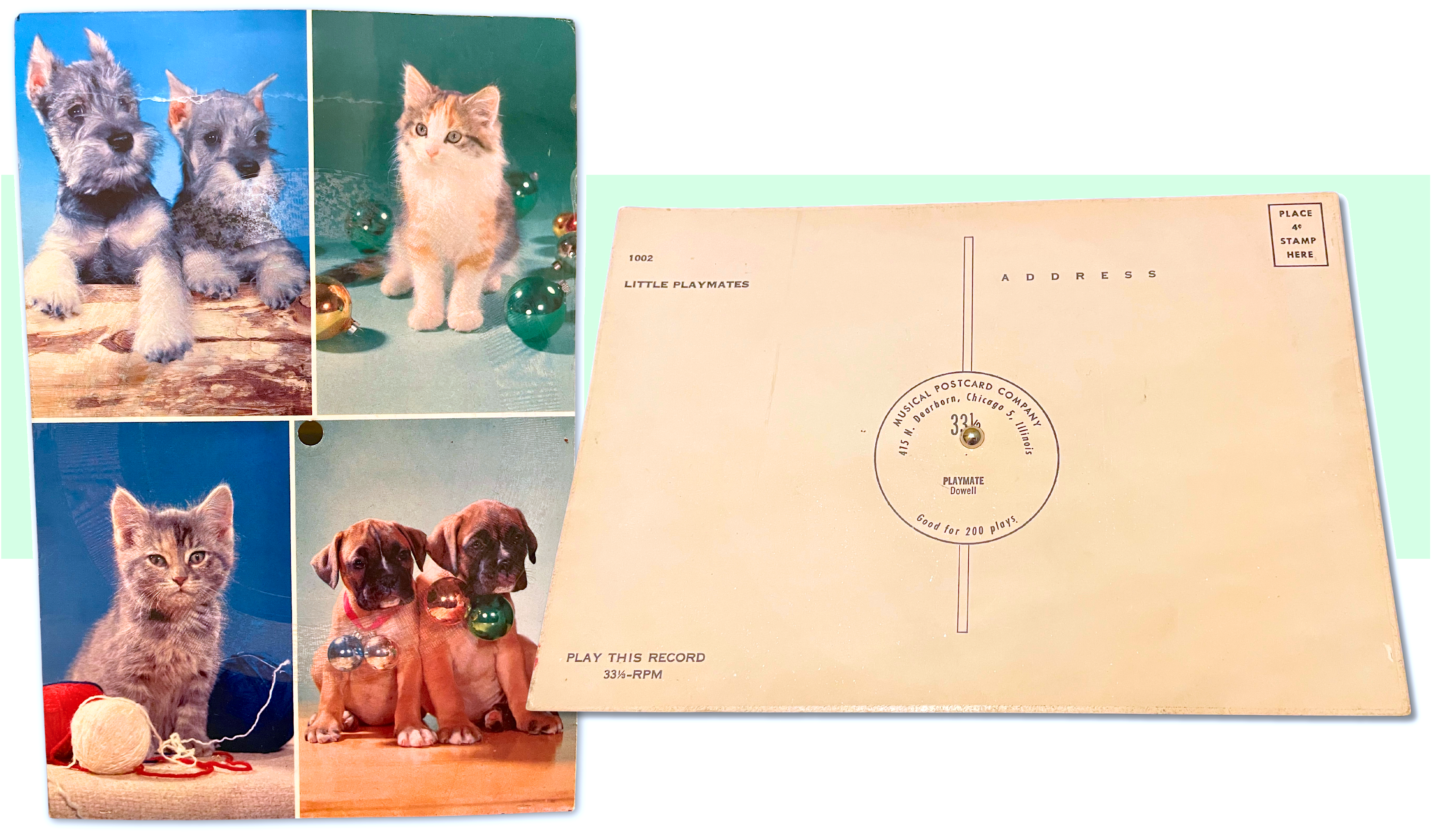

Museum Artifact: “Little Playmates” Musical Postcard / Christmas Card and “Chicago” Musical Postcard, c. 1960

Made By: Musical Postcard Company, 415 N. Dearborn St., Chicago, IL [River North]

Donated By: Nyla Panzilius

It’s no news to anyone that you can’t fit a square peg in a round hole. But what about playing a rectangular paper record on a round turntable? If you’re simultaneously intrigued and skeptical, you’re probably no different than the person who received this cheery, puppy-and-kitten-laden Christmas card back in 1960 or so.

The musical postcard, also known as a talking or singing postcard, was already a well trod novelty by the time Chicago’s Musical Postcard Company got into the business. But there were reasons to believe this format had yet to realize its full potential. During the 1950s, with the birth of rock n’ roll, the rise of the 7-inch single, and the development of more affordable color printing methods, a few entrepreneurs anticipated an imminent golden age for the “phonocard.” Among them was a Chicago-based insurance salesman named Sol S. Bernstein.

The musical postcard, also known as a talking or singing postcard, was already a well trod novelty by the time Chicago’s Musical Postcard Company got into the business. But there were reasons to believe this format had yet to realize its full potential. During the 1950s, with the birth of rock n’ roll, the rise of the 7-inch single, and the development of more affordable color printing methods, a few entrepreneurs anticipated an imminent golden age for the “phonocard.” Among them was a Chicago-based insurance salesman named Sol S. Bernstein.

Born in Stockport, England, in 1902, Bernstein came to America with his family at age 11, settling in Chicago’s 10th Ward. He worked as a bookkeeper and salesman for a paper products company in his younger years, ultimately settling with his wife Mary in Logan Square, where they raised their kids Phyllis and Michael in an apartment at 2439 N. Albany Avenue.

It was, by most measures, a successful immigrant tale and a typical middle class, mid-century American lifestyle. But an aging Sol Bernstein may have felt that—much like the musical postcard—he was still capable of greater things. And so, utilizing his experience and connections from the insurance world and the paper trade—along with the help of a new business partner fresh off the boat from Morocco—he hatched a scheme for a business of his own. And when we say scheme, we mean that in both the strategic and potentially devious sense of the word.

Yes, it turns out that the Musical Postcard Company wasn’t quite as sweet and innocent and those puppies and kittens would suggest.

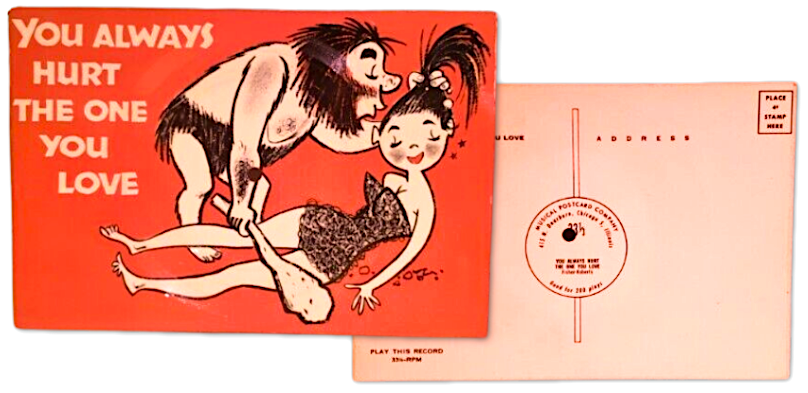

[A comical greeting card that hasn’t aged very well, circa 1960. This offering from the Musical Postcard Co., features the song “You Always Hurt the One You Love” by Spike Jones and His City Slickers; a rare example of the company utilizing a recording from a widely known performer.]

History of the Musical Postcard Company, Part I: The Square Record

We tend to think of singing greeting cards as a fairly modern novelty; since the 1990s, embedded microchips have been annoying people in the Hallmark aisle, mostly with festive jingles. But the conceptual union of recorded sound and paper picture cards dates much further back, with the first use of the term “musical postcard” showing up as early as 1904.

“A striking novelty in picture post-cards is about to be placed on the market by a French syndicate,” the New York Times reported that year, borrowing a story from the London Mail. “To an ordinary pictorial card is affixed a very thin transparent gelatine disk, on which is impressed a gramophone musical record. A hole is pierced through the center of the disk, and the post-card can be placed on an ordinary ‘talking machine’ and played in the usual way. . . . The disk, being perfectly transparent, does not in any way interfere with the picture beneath. As a novel advertising medium the new cards are certain to be popular.”

These early French audio cards, under the name La Sonorine, were designed to capture custom personal recordings transmitted on a device called a Phonopostal. This made it easy to imagine a huge range of exciting applications on the horizon . . . audio love letters sent to faraway partners; picture cards of popular musicians that would also “sing” their hit songs; promotional flyers for politicians that could double as portable stump speeches.

For most of the next half-century, though, the musical postcard went through disappointing fits and starts, always sounding better conceptually than it actually did in practice. Most production was based in Europe; the few American manufacturers of phono postcards often resorted to just stapling miniature black shellac gramophone records to their cards rather than mess with trying to effectively put grooves into a transparent material. Recorded messages were usually garbled and could only be played a few times.

With the general public losing its enthusiasm, the talking postcard industry went mostly dormant during the ‘30s and ‘40s, but started sprouting up again after World War II. By 1954, new production techniques allowed a 33-1/3 microgroove record to be pressed on clear, laminated paper, with enough durability for upwards of 200 plays. Again, most of the purveyors of this new wave were based in Europe, including the Vistasound and Fonoscope companies in the UK, Orchestrola and Ninophon in West Germany, Colorvox in Hungary, and a variety of publishers in Poland and the Soviet Union.

[Mid-century talking postcards from Colorvox (left) and Fonoscope (right), two European companies that started using laminated microgrooves]

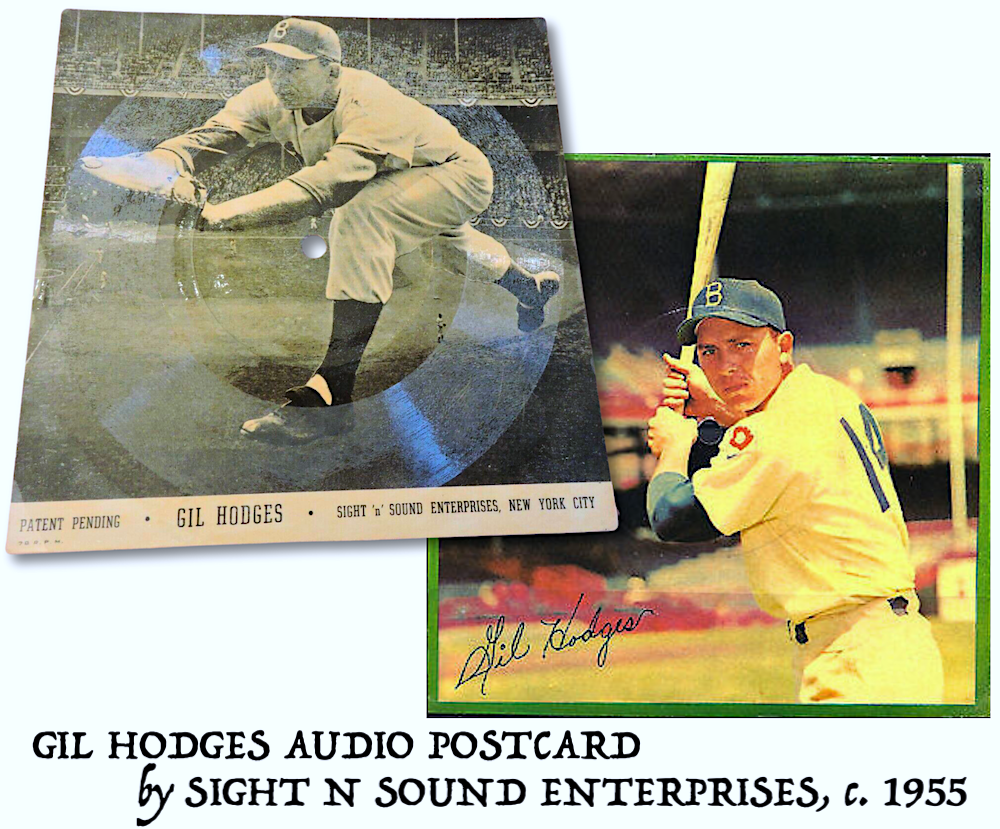

Stateside, one of the early adopters of the new format was Sight ’N Sound Enterprises of New York. The company produced some notable audio picture discs of local baseball heroes in the mid 1950s, such as the Brooklyn Dodgers’ Gil Hodges and Roy Campanella. And their talking postcards earned some fresh press, albeit not dissimilar from that of La Sonorine 50 years earlier.

“In physical format, the new mailing piece is the same size as a regular postcard,” the magazine Advertising Requirements reported in 1955, “but with a hole punched in the center. This hole is placed over the spindle on a phonograph and a special message recorded on the card is played for the recipient. The postcards have very good fidelity of reproduction and can handle voice, sound effects and music.”

“In physical format, the new mailing piece is the same size as a regular postcard,” the magazine Advertising Requirements reported in 1955, “but with a hole punched in the center. This hole is placed over the spindle on a phonograph and a special message recorded on the card is played for the recipient. The postcards have very good fidelity of reproduction and can handle voice, sound effects and music.”

For whatever reason, though, none of the big American publishing houses—be it postcard, greeting card, or the record business—jumped on the singing postcard train. Most of the cards popping up in American shops by 1959 and 1960 were still imported from Europe, often with novelty audio tracks or Christmas songs ripped off from original American or British recordings.

This was the landscape the Musical Post Card Company entered when it opened its Chicago office.

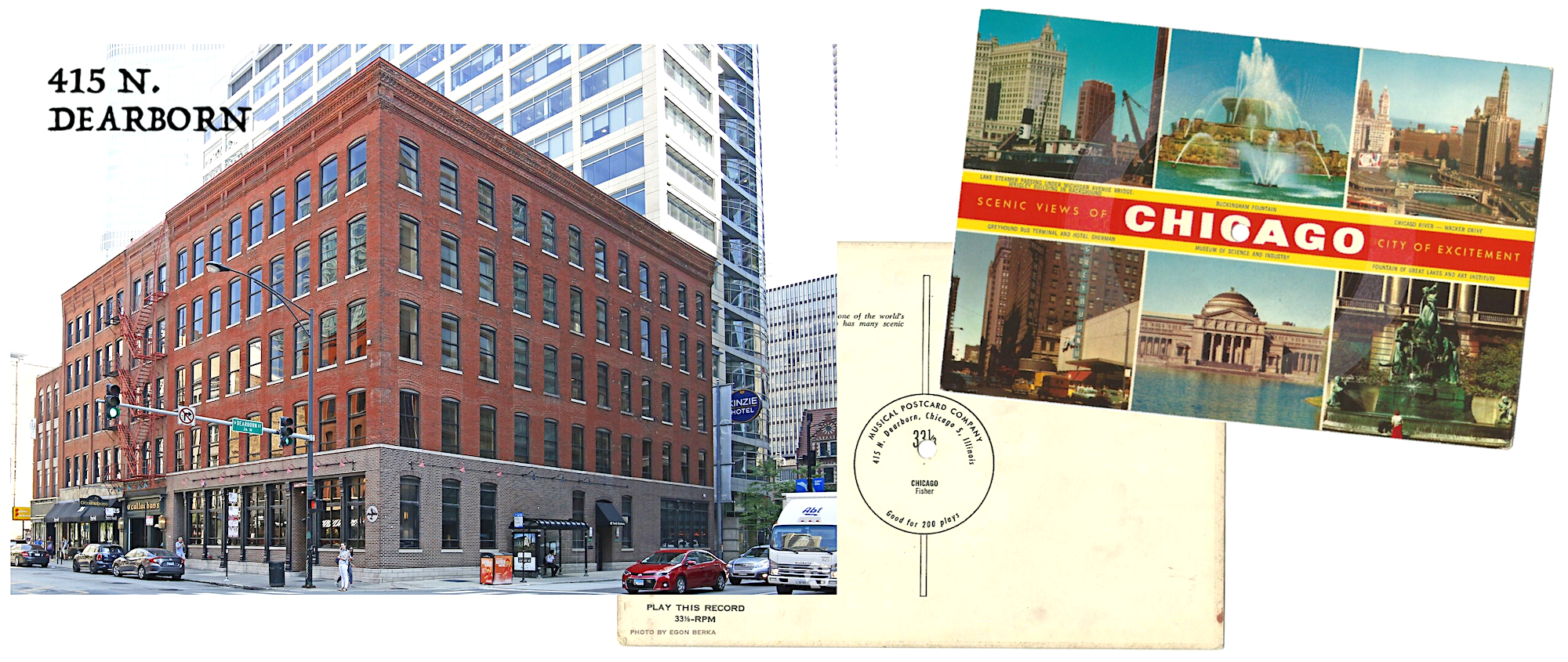

[The office of the Musical Postcard Company, as listed on the back of most of its cards, was in this building at 415 N. Dearborn St. On the right is a Chicago themed Musical Postcard featuring local landmarks and the accompanying song, “Chicago (That Toddlin’ Town)”]

II. A Man Looking for an Opportunity

As best we can tell, the complete saga of the Musical Postcard Company, Inc., encompassed roughly five years, starting around either 1958 or 1959. In that short period, the business used several different mailing addresses, presumably attached to a series of small offices: 630 W. Adams Street; 5776 N. Lincoln Ave.; and the location identified directly on the back of most of its postcards: 415 N. Dearborn St.

The only “executives” specifically identified in connection with the business were the nearly 60 year-old Sol Bernstein and his son Michael L. Bernstein, who had barely turned 18. While it’d be nice to imagine that dad and son set up a printing press and a recording studio with the goal of jumpstarting a new American industry for talking postcards, the evidence suggests their venture was less about making a product, and far more about finding people willing to invest in the idea of it.

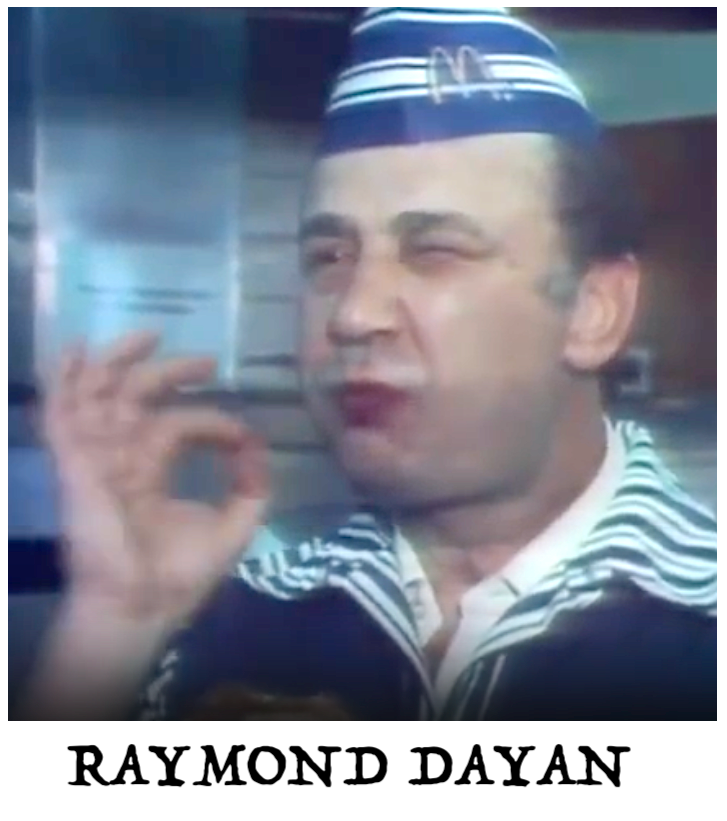

According to later court records (eek), Musical Postcard was actually just one of several Chicago enterprises Sol Bernstein had launched around this same time period, each of them following the same questionable profit model. In these sister ventures, Bernstein was joined by additional partners, including two associates of particular interest. One of them, 32 year-old Michael E. Viola, Jr., had recently moved to Chicago after serving six months for sales fraud in Pennsylvania, and was now the newly minted vice president of Asper-Vend Industries, Inc., a distributor of aspirin-spouting vending machines (Bernstein was the president). The other notable character was 27 year-old Raymond Jacques Dayan, a boisterous, Moroccan-born designer who co-founded the Dayan Greeting Card Company with Bernstein, specializing in small, illustrated humor cards (sans audio). The cards would quickly be forgotten, but Dayan would later go on to much greater fame, or infamy, as the man who brought the first McDonald’s restaurants to Paris in the 1970s.

According to later court records (eek), Musical Postcard was actually just one of several Chicago enterprises Sol Bernstein had launched around this same time period, each of them following the same questionable profit model. In these sister ventures, Bernstein was joined by additional partners, including two associates of particular interest. One of them, 32 year-old Michael E. Viola, Jr., had recently moved to Chicago after serving six months for sales fraud in Pennsylvania, and was now the newly minted vice president of Asper-Vend Industries, Inc., a distributor of aspirin-spouting vending machines (Bernstein was the president). The other notable character was 27 year-old Raymond Jacques Dayan, a boisterous, Moroccan-born designer who co-founded the Dayan Greeting Card Company with Bernstein, specializing in small, illustrated humor cards (sans audio). The cards would quickly be forgotten, but Dayan would later go on to much greater fame, or infamy, as the man who brought the first McDonald’s restaurants to Paris in the 1970s.

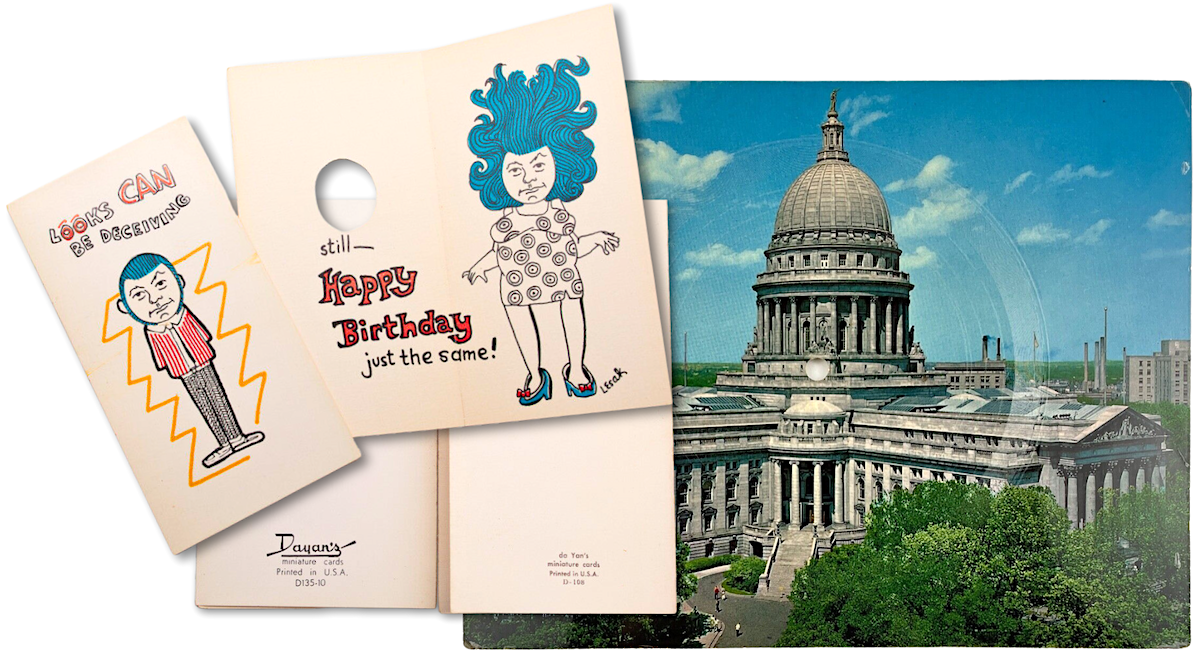

At this earlier stage in his career, however, Dayan enjoyed far less scrutiny and an ability to flamboyantly run a fraudulent business for several years under the radar. He and Bernstein were able to acquire their greeting cards from an outside supplier at a cost of just $6 per 1,000. That same stack would then be offered on to independent distributors at 6x the starting rate. The musical postcards were probably obtained through similar channels, although some appear to have been made by simply applying laminated record grooves of “Happy Birthday” over cheap Dayan greeting cards. In other cases, it seems like grooves may have been added to older, standard picture postcards—including a series originally published by the A. A. Cook Co. of Milwaukee.

To be fair, the song choices did at least tend to match the pictorial content. An old A. A. Cook view of the Wisconsin state capitol building, for example, was paired with a rendition of “On Wisconsin.” An overhead of Milwaukee’s County Stadium got “Take Me Out to the Ballgame,” and a more local collage of Chicago landmarks played Fred Fisher’s “Chicago (That Toddlin’ Town).”

[Left: An example of a Dayan’s Miniature Greeting Card, produced by Raymond Dayan and Sol Bernstein in the early 1960s. Right: A Musical Postcard of the Wisconsin State House featuring a 33-1/3 record of “On Wisconsin.” The original image came from a postcard published by the A. A. Cook Co. of Milwaukee]

The actual performers of these songs were rarely ever credited on the postcards, however, creating something of a mystery box of forgotten 1950s session singers, captured indefinitely on cardboard.

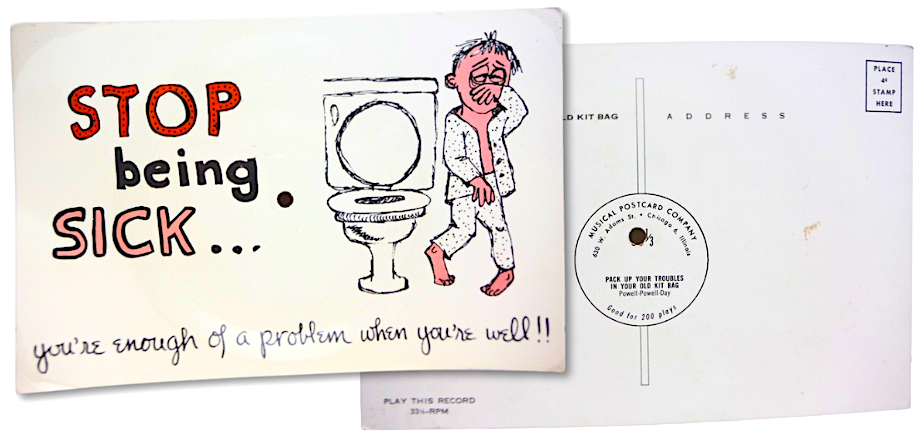

Many of the phonocards the Musical Postcard Company “produced”—such as the puppy and kitten Christmas card in our museum collection—could have originated just about anywhere, making it all the more impossible to guess at who might be singing the attached version of “Say, Say, Oh Playmate.” While this song was a big hit in both the 1940s and 1950s—and is still in circulation on children’s sing-a-long records today—this particular recording isn’t one of the famous renditions by the Kay Kyser Orchestra or the Fontane Sisters. Instead, the solo female singer is unnamed on the card itself, and all attempts at matching her performance to any version archived on the internet proved unsuccessful. It admittedly adds a bit to the ghostly quality of the postcard audio, especially considering we might reasonably be the first people to hear this ultra-obscure record in 60 years.

[Each Muscial Postcard claimed to be guaranteed for up to 200 plays, meaning this puppy and kitten card has a maximum of 199 spins to go]

In any case, Sol Bernstein didn’t seem too concerned with advertising the talents of the singers on his postcards, nor did he promote his products much at all to a general consumer audience—it wasn’t part of the budget. Instead, all effort was focused on recruiting and exploiting—err, employing—a network of regional distributors to proliferate these cards down the proverbial food chain.

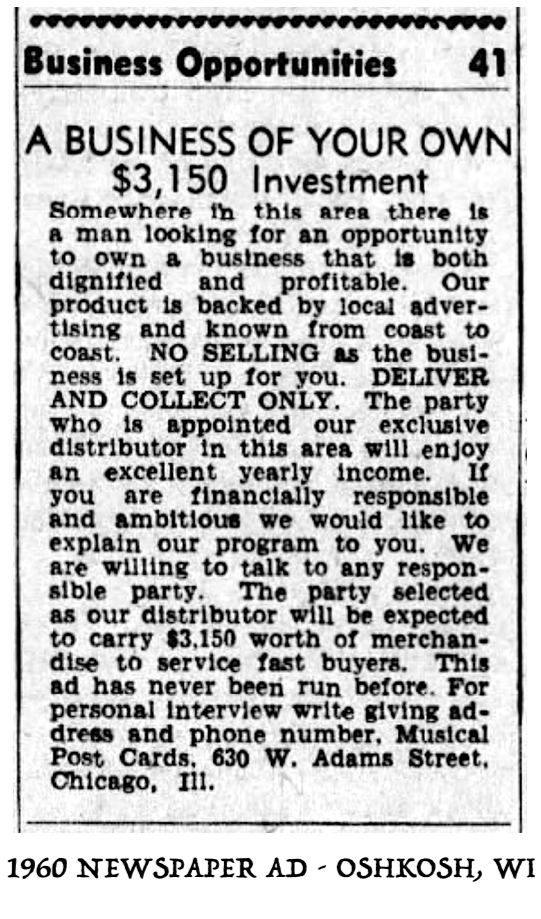

“A Business of Your Own: $2,350 Investment,” read a 1960 advertisement posted in the classified section of the Nashville Tennessean newspaper. “Somewhere in this area there is a man looking for an opportunity to own a business that is both dignified and profitable. Our product is known from coast to coast. NO SELLING as the business is set up for you. DELIVER AND COLLECT ONLY. The party who is appointed our exclusive distributor in this area will enjoy an excellent yearly income. If you are financially responsible and ambitious we would like to explain our program to you. We are willing to talk to any responsible party. The party selected as our distributor will be expected to carry $2,350 worth of merchandise to service fast buyers. This ad has never run before. For personal interview write giving address and phone number. Musical Post Card Company, 630 W. Adams Street, Chicago 6, Ill.”

Of course, the same ad HAD run before. In fact, the same ad in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, had run a few months earlier, asking for a $3,150 investment, which perhaps proved a bit too ambitious. So, adjusting down to $2,350, Bernstein and his partners were able to start hooking some marks in a half-dozen different cities.

Of course, the same ad HAD run before. In fact, the same ad in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, had run a few months earlier, asking for a $3,150 investment, which perhaps proved a bit too ambitious. So, adjusting down to $2,350, Bernstein and his partners were able to start hooking some marks in a half-dozen different cities.

The idea behind the scam—which was running concurrently with Bernstein’s vending machine and greeting card businesses—was too convince would-be distributors that they should:

1. Purchase a big pile of musical postcards via mail from Chicago.

2. Deliver those cards to local retailers to display in their shops at marked up prices.

3. Wait for those retailers to sell off the lot, ensuring big profits.

The crux of the pitch relied on the distributor believing that musical postcards would, indeed, be something that Americans would pay 60 cents for, compared to the 5 or 10 cents of a normal picture card. To be fair, it’s possible that Sol Bernstein genuinely believed that himself; that this medium was finally going to have its moment. Importantly, though, his business model wasn’t dependent on that dream coming true. It only needed some other schmoes who were willing to roll the dice on it.

The whole plan probably worked a bit too well for Bernstein, because after a few years raking in profits from his paper novelties and aspirin packets, the Feds finally caught a whiff of something fishy.

III. Return to Sender

“The federal grand jury indicted six men yesterday for an alleged $90,000 mail fraud in the sale of musical greeting card distributorships and promises of $100 a week in profits,” the Chicago Tribune reported on May 29, 1964 [bear in mind, $90,000 in 1964 would be equivalent to nearly $900,000 in 2024].

Indicted alongside the 62 year-old Sol Bernstein were his greeting card partner Raymond Dayan, his aspirin vending cohort Michael Viola, and three others: Peter B. Gerdes, DeWitt H. Dodge, and Joel R. Peterson. On top of the $90K card indictment, Bernstein and Viola were hit with an extra $40K charge for the vending machine scam.

Indicted alongside the 62 year-old Sol Bernstein were his greeting card partner Raymond Dayan, his aspirin vending cohort Michael Viola, and three others: Peter B. Gerdes, DeWitt H. Dodge, and Joel R. Peterson. On top of the $90K card indictment, Bernstein and Viola were hit with an extra $40K charge for the vending machine scam.

The case was referenced a year later in a syndicated newspaper article titled, “Be Alert to Get Rich Quick Mail Frauds.”

“Two related companies, Dayan Greeting Card Co. and Musical Post Card Co., placed blind ads in newspapers, offering $50-a-day profits on the investment of $2,400 in greeting cards and racks,” the article specified. “The promoters bought the cards for $6 per thousand, sold them to distributors for $36, and the retail price was supposed to be $100. The cards were of low quality and there were few retail buyers. Postal inspectors found 32 victims were swindled of more than $89,000. The principal promoter was jailed for 60 days, fined $1,000, and placed on probation for two years. Five others received lesser sentences.”

Fortunately, it doesn’t seem like Sol Bernstein’s son Michael was ever implicated in the case, but seeing his dad go to prison for a couple months probably wasn’t how we imagined their business partnership going.

If you think Sol learned his lesson after this embarrassing episode, though, the evidence again suggests otherwise. He and Michael Viola were both openly recruiting salesmen for vending machine distributorships again within a few years. And by 1969, Sol and his wife Mary were the president and VP of a new Chicago company called Century Projects, Inc., which doesn’t appear to have deviated much from the Musical Postcard pyramid model.

[This building at 3015 S. Archer Avenue was briefly the home of Sol Bernstein’s Century Projects Co. in 1969-1970. The 1969 ad to the right follows the same mold as the Musical Postcard scheme earlier in the decade.]

“A Business of Your Own,” read a 1970 ad in the Daily-Republican Register newspaper of Mount Carmel, Illinois. “$895 cash investment will bring excellent return servicing a route of U.S. Postage Stamp Machines. Write, including phone no., Century Projects, 3015 S. Archer Ave., Chicago, Ill 60608.”

The success of the stamp machine scam is unknown, but considering Sol Bernstein was back to his old tricks at nearly 70 years of age makes for a rather sad ending to the story. Sadder still, his son Michael died young in 1978, followed a year later by his wife Mary. Sol, himself, breathed his last in 1982.

Meanwhile, during that same summer of 1982, Bernstein’s old greeting card pal Raymond Dayan was making headlines around the globe. Dayan, who’d worked for McDonald’s founder Ray Kroc as an interior designer in the early 1970s, had somehow parlayed that gig (via charm and bluster) into becoming the restaurant chain’s first franchisee in France, the land of supposedly high culinary standards. Dayan proved his doubters wrong, eventually running 14 profitable, tourist-driven McDonald’s locations around Paris. By the early ’80s, however, the folks at McDonald’s HQ in Illinois had grown tired of Dayan’s freewheeling interpretation of restaurant standards and his refusal to renegotiate his original contract. Taking legal action, the home office forced Dayan to remove all his McDonald’s signs and affiliations in 1983, and his subsequent attempts to rebrand his restaurants as “O’Kitch” proved unsuccessful. Dayan lived out his final years back in Chicago. He died in 2011, aged 77.

Sources:

“Musical Postal Cards” – New York Times, Sept 28, 1904

“Sight ‘n Sound Develops New ‘Talking Postcards'” – Advertising Requirements, May 1955

“Jailed for Six Months (Michael E. Viola, Jr) – Lancaster New Era, Dec 10, 1958

“A Business of Your Own: $2,350 Investment” – The Nashville Tennessean, July 10, 1960

“Six Indicted on Charge of Mail Fraud” – Chicago Tribune, May 29, 1964

“Be Alert to Get Rich Quick Mail Frauds” – Union Springs Herald (Alabama), Oct 14, 1965

Mary G. Bernstein (obit) – Chicago Tribune, Oct 15, 1979

“McDonald’s Seeks to Keep Its Arches Golden in Paris” – Atlanta Journal Constitution, Sept 19, 1982

“Mon Dieu! American Culinary Virus is Infecting France” – Journal Times (Racine), June 26, 1983

“Phonocards and Phonopost History” – lotzverlag.de