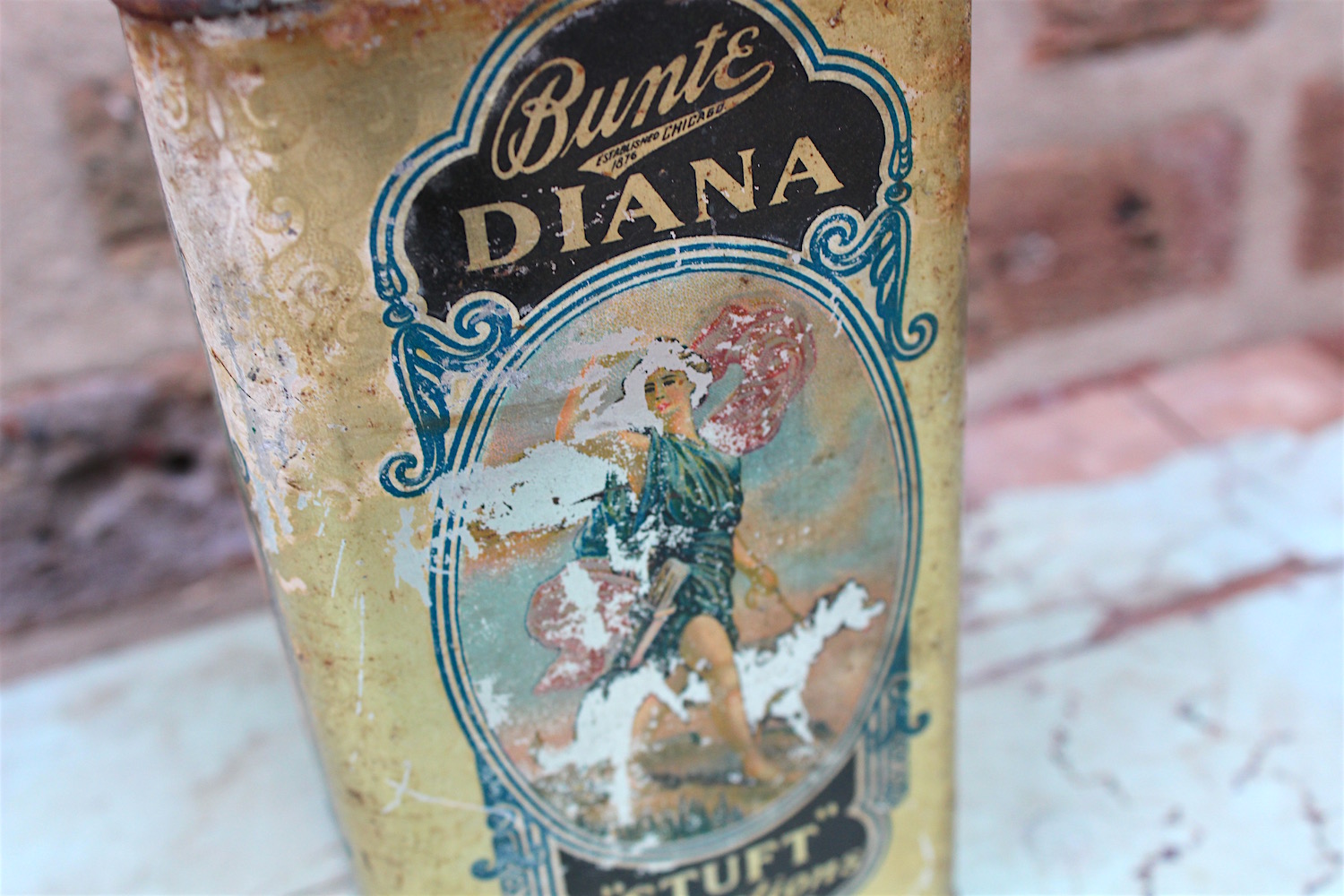

Museum Artifacts: Bunte “Fine Confections, “Diana,” “Stuft” and “World Famous Candies” Tins by Bunte Brothers, 1910s-1930s

Made By: Bunte Brothers Candy, 3301 W. Franklin Blvd., Chicago, IL [Humboldt Park]

Which industry best exemplified the spirit of Chicago at its manufacturing zenith? The steel mills? The Union Stock Yards? The railroads? Architecture?

Nope. It was definitely candy—sweet, delectable, teeth-rotting candy.

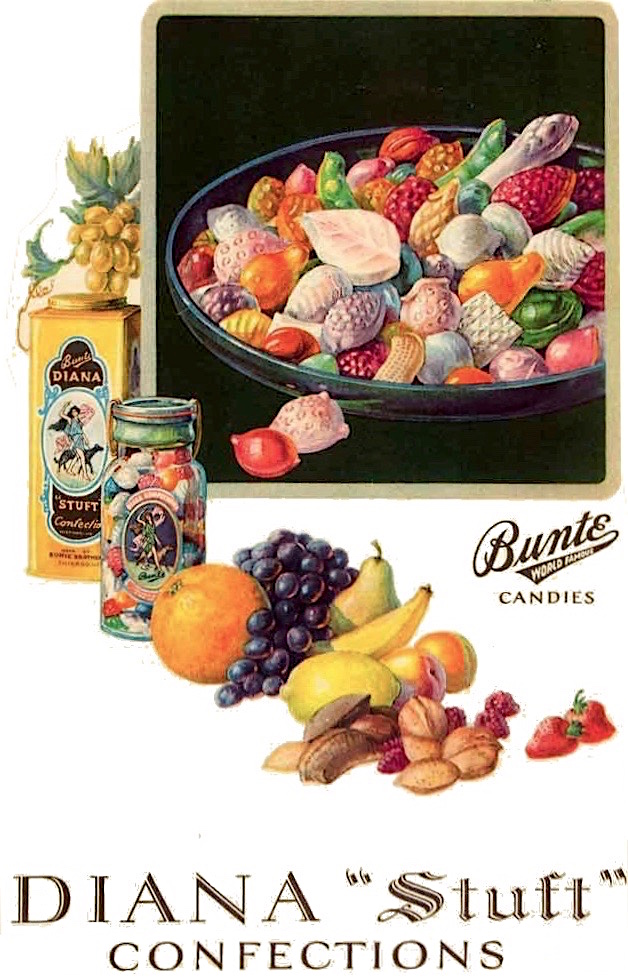

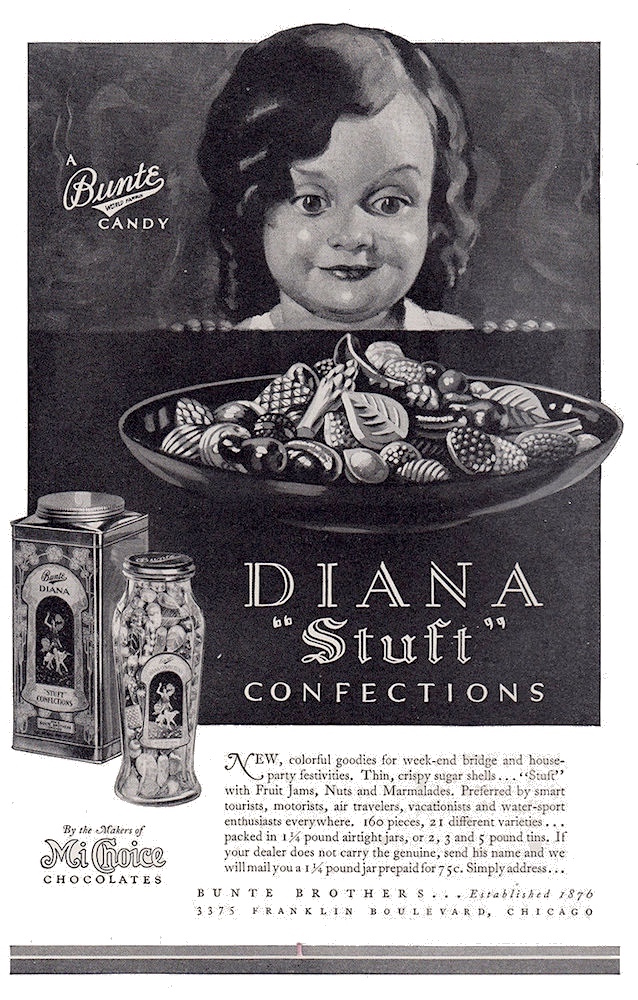

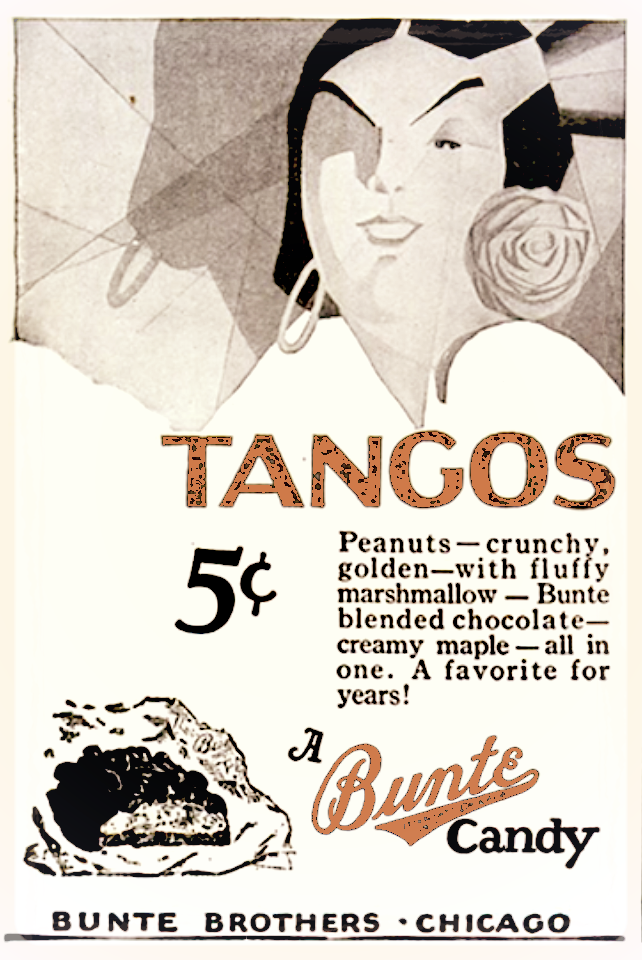

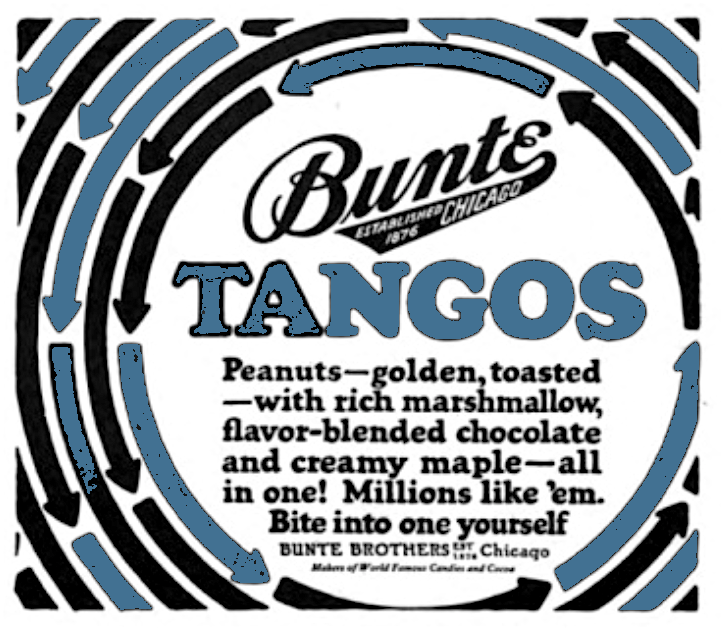

For the thousands of Chicago factory workers employed in the confectionery trade, there was often no better reward for a hard day’s work than a handful of the merchandise. During the late 19th and early 20th century, the city was home to many of the leading candy makers in the country, and Bunte Brothers, for a time, was arguably chief among them all—producing more than 1,000 different varieties of goodies, including the first peanut-chocolate candy bar (Tangos), the first hard candies with soft fruit filling (Diana “Stuft” Confections), and possibly the first mass-produced, wholesale Christmas candy canes.

The four colorful Bunte tins in our museum collection, which date from around the 1910’s to the ’30s, have a regal, classical flare to match the company’s sophisticated reputation. Across 80 years, Bunte Brothers truly mastered the art of making cheap candy seem classy, and in the process, they enabled several generations of sweet-toothed Americans to enjoy their vices with reverence, rather than shame.

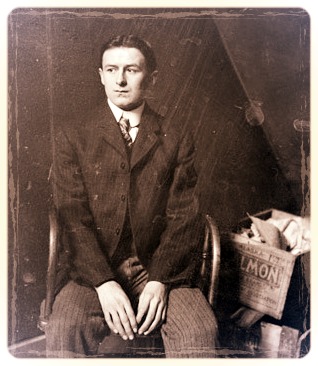

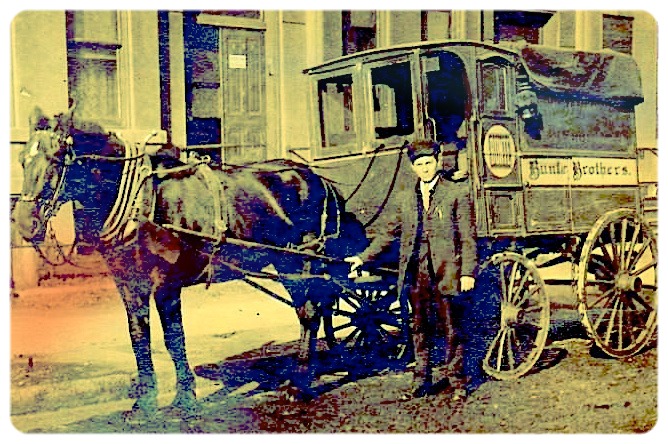

[Bunte salesman Christian Sorensen posing with his delivery wagon, circa 1900. Picture courtesy of Sorensen’s great grandson, Dan Fulwiler]

[Bunte salesman Christian Sorensen posing with his delivery wagon, circa 1900. Picture courtesy of Sorensen’s great grandson, Dan Fulwiler]

Die Ersten Brüder

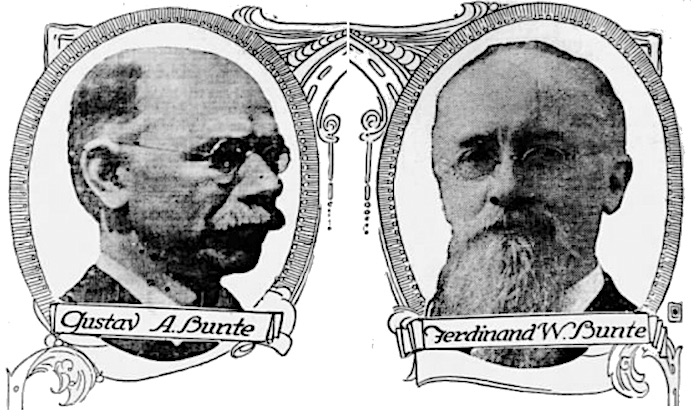

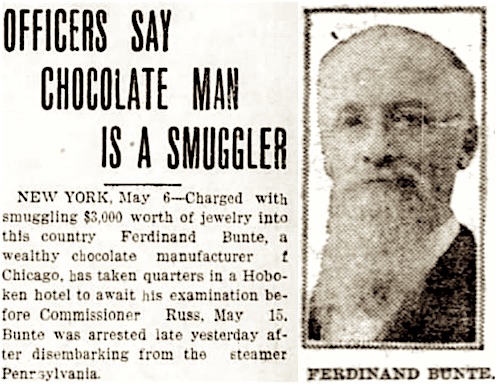

The original Bunte Bros. were Ferdinand (b. 1846), Gustavus (1852) [pictured below], and Albert (1855); German immigrants who arrived in Philadelphia as teenagers and entered into the candy business there in the late 1860s—after Ferdinand had completed a stint with the U.S. Marine Corps at the tail end of the Civil War. According to legend, young Ferdinand Bunte’s first go at confectioning—using one little kettle in the back room of his store—produced sweets so mouth-watering that people started coming from all over town just to get a whiff of them.

The Brothers Bunte were the confectioners du jour in the City of Brotherly Love, but success was ultimately fleeting. With the congestion of competition in the east coast candy market, it was exceedingly difficult for any one business to keep its head above water.

The Brothers Bunte were the confectioners du jour in the City of Brotherly Love, but success was ultimately fleeting. With the congestion of competition in the east coast candy market, it was exceedingly difficult for any one business to keep its head above water.

And so, hearing the clarion call from the West, adventurous brother Gustav called upon Ferdinand and Albert to move their enterprise to Chicago in 1876. Here, they partnered with another upstart German candyman named Charles Spoehr to open a small shop at 416 S. State Street.

By Christmas of that first year, the firm of Bunte Bros. & Spoehr was already establishing a stellar reputation, even earning a shoutout from the Chicago Tribune in an article about State Street’s rising commercial appeal. “Their caramels are considered the best in the city,” the paper raved.

From there, it’d be easy to just say “and the rest was history,” but there were some notable stops and starts along the way—most of which are usually omitted from published company histories. The State Street shop, for example, dissolved after just a year in business, and the Bunte Brothers subsequently scattered a bit for a while. Ferdinand took a position as a foreman in the candy factory of another German-by-way-of-Philly, John Kranz, while Gustav and Albert partnered with the firm of Julius H. Schulz at 184 Indiana Street. Even when Bunte Bros. & Spoehr announced a glorious reunion in the 1880s, it didn’t quite bring the whole family back together.

Within months of Ferdinand rejoining the fold in 1885, his kid brother Albert promptly left to start his own separate business, Albert Bunte & Co. It’s unclear if there was a sibling feud at work, or if Al simply wanted to spread his wings. Either way, Ferdinand and Gustav would go on to be the namesake architects of the Bunte Brothers brand, while Albert functioned first as a competitor, then a peripheral figure in the years that followed.

“The First Requisite”

As was the German tradition, Bunte Bros. & Spoehr liked to emphasize quality over quantity when it came to promoting their goods. Only the highest grades of cocoa beans, gelatines, and pure sugar cane would do.

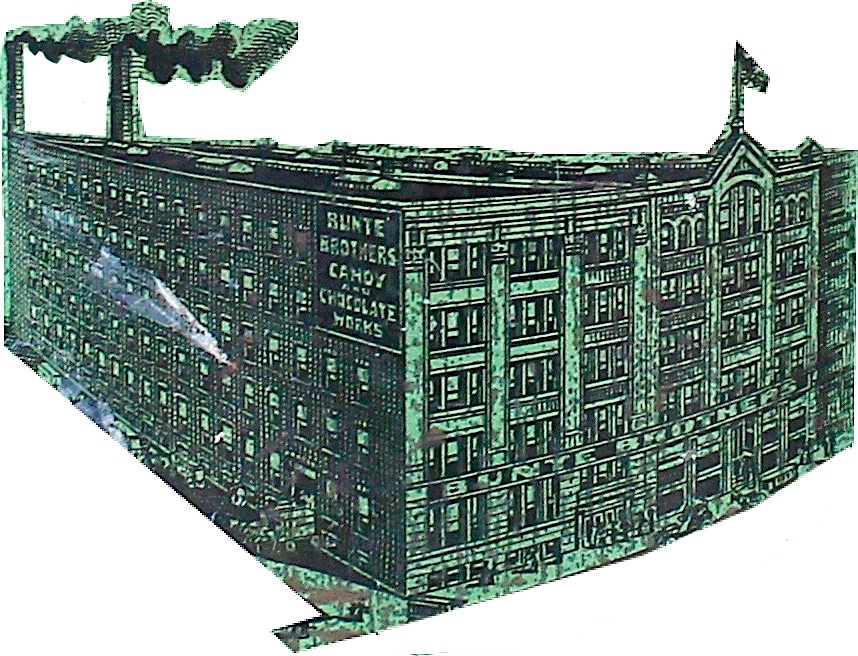

When demand for Bunte’s “Fine Confections” started outpacing supply, however, the firm was forced to concentrate on new means of mass production, repeatedly expanding its workforce, pushing its circulation, and relocating to increasingly large facilities: 94 Wells Street, 83 Market Street, 70 W. Monroe Street, and finally to a large, five-story factory down the road at 141 W. Monroe (720 by modern street numbering). The latter facility, which would remain the company’s home from the 1890s until 1920, is pictured on the back of the Fine Confections tin in our museum collection, as seen below.

“Among the prominent houses of Chicago is Bunte Bros. & Spoehr, manufacturing confectioners,” A.T. Andreas wrote in his 1886 History of Chicago. “This firm has been in business but a few years, but in a comparatively short time they have built up a trade that is truly wonderful, placing their goods with success in states where no other Chicago manufacturer in this particular branch of trade has ever thought of venturing.”

“Among the prominent houses of Chicago is Bunte Bros. & Spoehr, manufacturing confectioners,” A.T. Andreas wrote in his 1886 History of Chicago. “This firm has been in business but a few years, but in a comparatively short time they have built up a trade that is truly wonderful, placing their goods with success in states where no other Chicago manufacturer in this particular branch of trade has ever thought of venturing.”

In 1899, an issue of The Dispatch (of Moline, IL) further hailed Bunte Bros. & Spoehr as “well deserving of the reputation created by the excellence of their goods.”

“We base our business on the principle that quality is the first requisite,” a Bunte representative added, “and our trade has grown steadily until now our confectionery sells itself.”

Unfortunately, like many manufacturers of the period (or any other period, for that matter), Bunte seemed willing to cut corners in other areas of its business—including ethics—to keep that level of quality sustainable economically.

In 1894, as a harsh example, more than one-third of the company’s 113 employees at the Monroe Street plant were young girls under the age of 16—a vulnerable workforce that often went home with bloody fingers after hours of wrapping and packaging small candies. To make matters worse, plant manager Ferdinand Bunte was repeatedly cited by Illinois factory inspectors for failing to accurately report on his child labor numbers, and for scheduling some of the factory women for longer shifts than the legal limit of eight hours.

Ferdinand got in some other types of legal trouble, as well. In 1910, the very wealthy 64 year-old was arrested by U.S. customs officers in New York for smuggling loads of jewelry and watches into the country from his native Germany, using a false bottomed trunk on a steamship.

The embarrassing episode grabbed headlines nationwide, and yet, like Ferdinand’s past moral missteps, it didn’t seem to put much of a dent in his reputation as the noble candy mogul. After his death in 1920, Ferdinand Bunte was praised in the pages of the Historical Encyclopedia of Illinois as “a man of high ideals . . . a loyal and enterprising citizen and a true and faithful friend. . . . His character and achievements remain as a force for good in the community.”

The embarrassing episode grabbed headlines nationwide, and yet, like Ferdinand’s past moral missteps, it didn’t seem to put much of a dent in his reputation as the noble candy mogul. After his death in 1920, Ferdinand Bunte was praised in the pages of the Historical Encyclopedia of Illinois as “a man of high ideals . . . a loyal and enterprising citizen and a true and faithful friend. . . . His character and achievements remain as a force for good in the community.”

. . . And who am I to say otherwise?

Even the Bunte Brothers’ heritage—an albatross around the necks of many German-American business owners during the First World War—never seemed to stir much resentment against them. Ferdinand was quick to remind people of his service to America during his very first years in the country, and of his days as a White House guard during the Andrew Johnson administration—a gig he immortalized with Bunte’s “White House” brand cocoa mix. In the long run, the politics and challenges of the early 20th century would actually send Bunte into its golden era, rather than a tailspin.

[Bunte “White House” cocoa mix advertisement, 1917]

[Bunte “White House” cocoa mix advertisement, 1917]

War Boom

After roughly a quarter century in business, Bunte Bros. & Spoehr was finally properly incorporated in 1903, and after Spoehr’s retirement three years later, it was reorganized again as simply “Bunte Brothers.”

In the years that followed, the company rolled out some of its most successful brands, including Tangos and Diana “Stuft” Confections. They also purchased an additional eight-story complex next to their existing Monroe Street factory, giving Bunte a multi-building, candy-making superplex in the West Loop. The only real limitation on Bunte’s continued growth, it seemed, was its clientele.

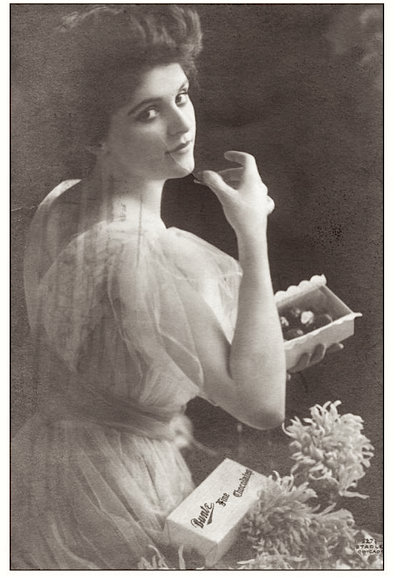

Up until the First World War, chocolate and candies were primarily marketed toward women and children, as men were presumed to have all they needed in the form of booze and cigars. As early as 1893, though, the Buntes seemed aware that a broader audience could be reached.

Up until the First World War, chocolate and candies were primarily marketed toward women and children, as men were presumed to have all they needed in the form of booze and cigars. As early as 1893, though, the Buntes seemed aware that a broader audience could be reached.

In a letter sent from the company to the nation’s grocers that year (offering guidelines for selling confections in counter displays), they explained that “a candy counter, if properly cared for, becomes the most attractive feature of the store to a majority of the people who enter it. This is especially true in small towns and of country people. When you are on the train notice who are the best patrons of the peanut boy. You will see that country people not only buy, but keep their eyes on the basket of sweets every moment it is in sight.”

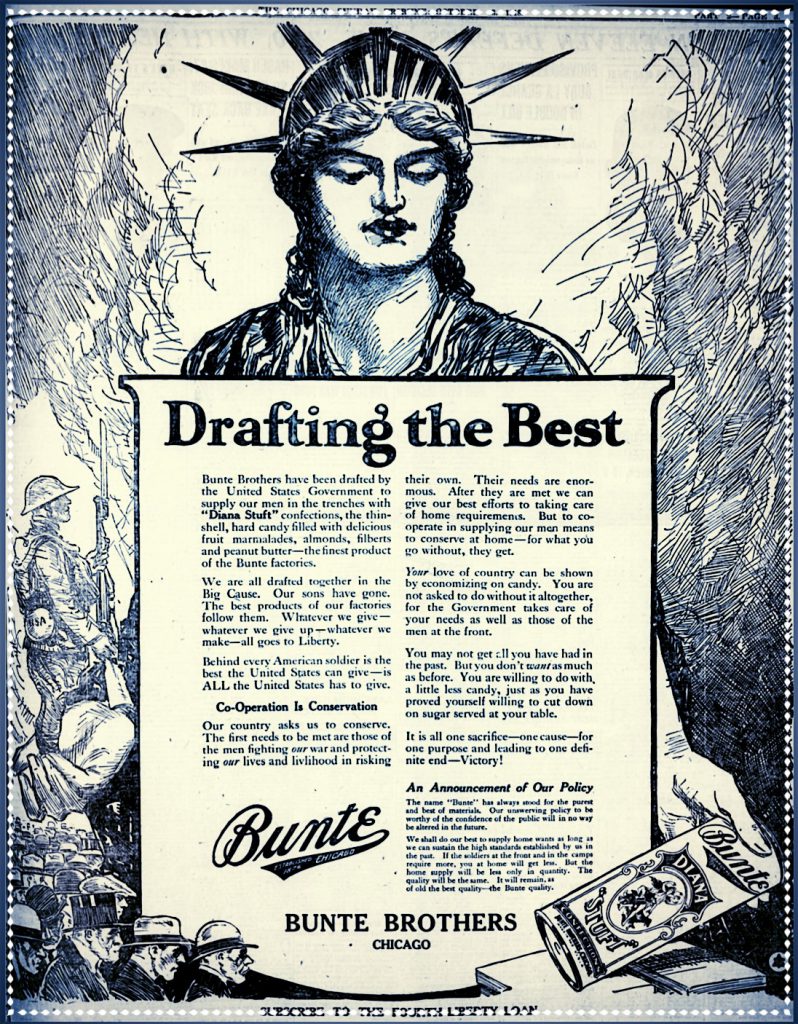

A bit condescending, perhaps, but Ferdinand and Gustav were on to something. By the time the war broke out, the U.S. Government had also come to see the appeal of candy to “country people,” many of whom made up the growing fighting forces overseas. Candies were cheap, traveled well, and provided hungry soldiers with a boost of energy and an emotional pick-me-up. Not surprisingly, when it came time to fill the army’s ration orders, Bunte was patriotically first in line.

“Bunte Brothers have been drafted by the United States Government,” read a 1918 ad, “to supply our men in the trenches with ‘Diana Stuft’ confections, the thin-shell, hard candy filled with delicious fruit marmalades, almonds, filberts and peanut butter—the finest product of the Bunte factories.

“Bunte Brothers have been drafted by the United States Government,” read a 1918 ad, “to supply our men in the trenches with ‘Diana Stuft’ confections, the thin-shell, hard candy filled with delicious fruit marmalades, almonds, filberts and peanut butter—the finest product of the Bunte factories.

“We are drafted together in the Big Cause. Our sons have gone. The best products of our factories follow them. Whatever we give—whatever we give up—whatever we make—all goes to Liberty.”

Ferdinand Bunte was, of course, less inclined to mention that two of his own daughters were living in Germany, both married to German men caught up in the other side of the conflict. Several years later, Ferdinand would die in Deutschland himself, visiting those daughters shortly after the war’s end. On the brighter side, his life’s work had provided a legacy. The candy business was booming more than ever as returning American servicemen brought home their new love of Bunte candies, and no two men would benefit more from it than the next generation of Bunte Brothers.

[The tins from our museum collection, from left: “World Famous Candies” (c. 1920s), “Fine Confections” (c. 1910s), “Diana STUFT Confections” (c. 1920s), “Diana Filled Confections” (c. 1930s)]

[The tins from our museum collection, from left: “World Famous Candies” (c. 1920s), “Fine Confections” (c. 1910s), “Diana STUFT Confections” (c. 1920s), “Diana Filled Confections” (c. 1930s)]

Bunte Bros., The Next Generation

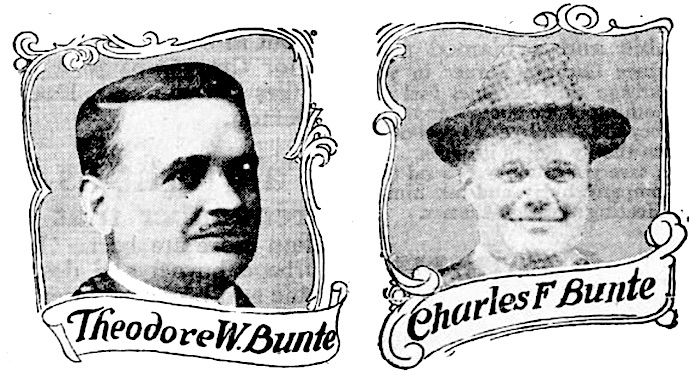

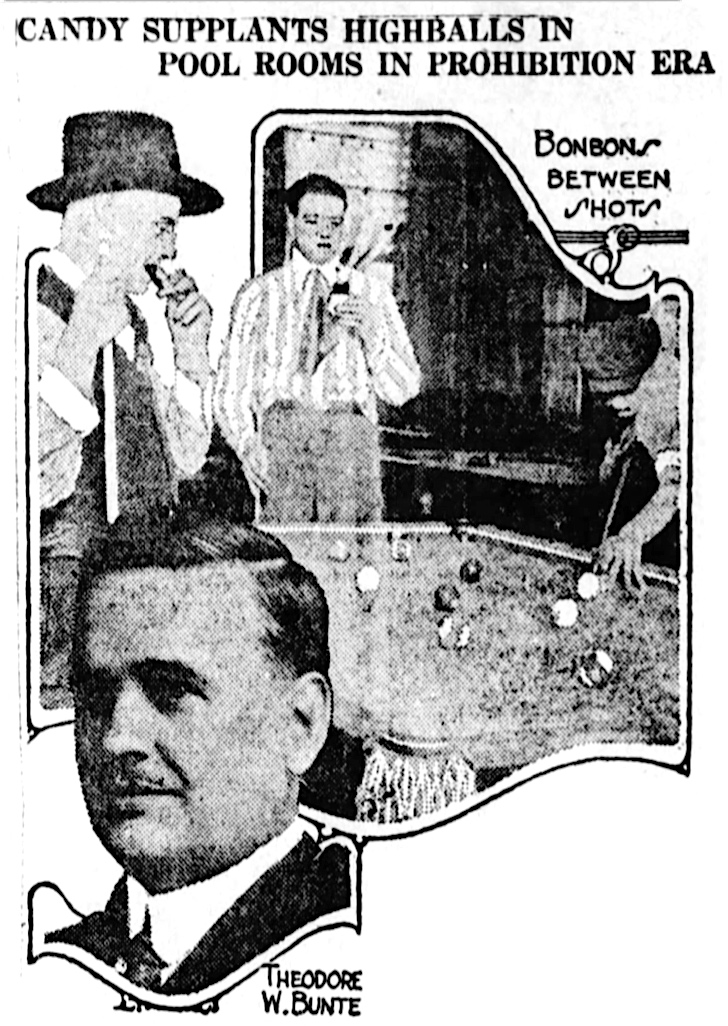

Back in the summer of 1917, right in the middle of the war and three years before Ferdinand Bunte’s death, a passing of the torch was announced via a full page ad in the Chicago Tribune, as Ferdinand’s sons Theodore W. Bunte and Charles F. Bunte were officially named President and Vice President of the firm, respectively.

By now, the company was riding high not only from its government contracts and growing pool of adult candy buyers, but also from success with its forays into non-traditional products like cocoa mix, marshmallows, and menthol cough drops (“Stop That Tickle for a Nickel!”). There were now more than 1,000 Chicagoans in Bunte’s employ, as well, with most of them of somewhat suitable working age.

By now, the company was riding high not only from its government contracts and growing pool of adult candy buyers, but also from success with its forays into non-traditional products like cocoa mix, marshmallows, and menthol cough drops (“Stop That Tickle for a Nickel!”). There were now more than 1,000 Chicagoans in Bunte’s employ, as well, with most of them of somewhat suitable working age.

At the ages of 71 and 65 respectively, Ferdinand and Gustav were no spring chickens, themselves, and they were finally content to walk away from their creation and let a new set of Bunte Brothers take the reins. The announcement was also paired with an invitation for potential investors to buy new shares of Bunte stock and get on board the money rocket into the 1920s.

“We, the elder Bunte Brothers, are turning over to the younger Bunte Brothers the active management of our great candy business. In doing so we wish to express our great appreciation of the public confidence vested in us for more than 40 years. We have regarded candy making as a sacred trust. We have made candy to be healthy and wholesome for hundreds of thousands of youngsters and grown-ups in every part of the world. These people—our public—have made the name of Bunte a household symbol of quality. They have made possible the slogan, ‘Bunte supplies candy for the four corners of the globe.’

[As company president, Theodore W. Bunte and his wife would take up residence in the Edgewater Beach Apartments, while brother Charles moved his family to a cushy pad in Wilmette]

[As company president, Theodore W. Bunte and his wife would take up residence in the Edgewater Beach Apartments, while brother Charles moved his family to a cushy pad in Wilmette]

“For Theodore and Charles Bunte we bespeak the utmost in confidence on the part of those who have so liberally patronized us. Please remember that both Theodore and Charles Bunte have been active heads of this business for 12 years . . . They are masters of the art of candy making and selling—Theodore in the invention of candies and candy making machinery, and Charles in the selling of our products. Much of the great progress made by our company in late years has been due to these men.

“Now, following our retirement, we are gratified to look ahead and prophecy that with young blood, modern aggressive policies and increased facilities, the Bunte organization will be able to handle the large business increases which have been offered to it in the past and the still greater increases to come in the immediate future.” — Ferdinand & Gustav Bunte

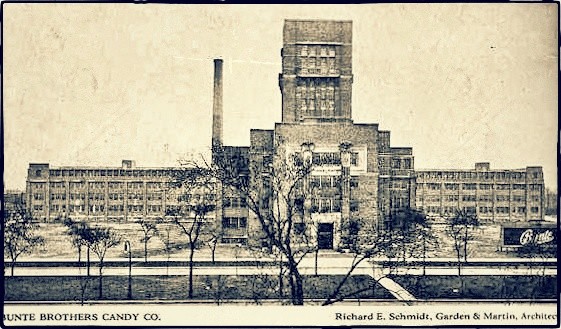

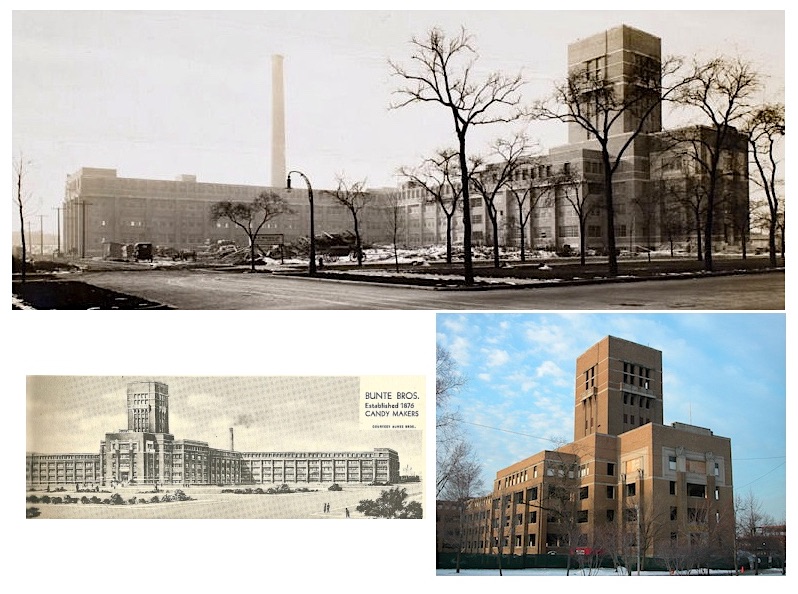

The mention of “increased facilities” was no abstract concept. Within weeks of the transfer of power, Bunte Brothers purchased the land in Humboldt Park on which would stand their next (and final) factory—a state-of-the-art behemoth at 3301 W. Franklin Blvd., designed by the architectural firm of Schmidt, Garden and Martin.

The Franklin Factory

While perhaps not quite as whimsical as the Wonka factory, the five-story, 450,000 sq. ft., $2,000,000 Bunte plant on Franklin Blvd., which opened in 1921, could at least be described as the 1920s equivalent of today’s liberal-minded tech company offices.

In a 1921 issue of Advertising and Selling, writer Duane Wanamaker described the “magnificent new factory” as “the climax of [Bunte]’s prosperity—an imposing business monument, built, one might say, of candy and chocolate.

“The factory, among other features, has its own laundry. The boilers are operated by automatic machinery so that coal can be delivered directly from the freight cars to the machines for furnace firing, eliminating all dust and grime.

“The factory, among other features, has its own laundry. The boilers are operated by automatic machinery so that coal can be delivered directly from the freight cars to the machines for furnace firing, eliminating all dust and grime.

“The importance of welfare work for the employees has been considered with minute care. Courts for handball and indoor baseball are laid off on the roof and are open to employees at noon and after closing hours. An immense restaurant, accommodating from 1,500 to 2,000 people, serves the best food prepared by expert chefs at nominal prices. A beautifully appointed rest room is maintained with a professional attendant in charge. A carefully adjusted ventilating system has been installed which insures abundance of fresh air, and fresh drinking water from bubbling fountains are available all over the plant.”

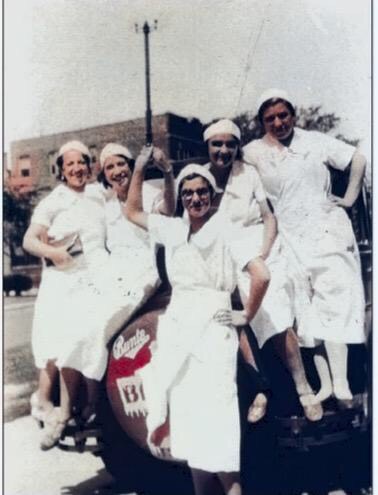

It’s hard to say that any factory worker 100 years ago ever “had it good,” but the early days of the Bunte Palace certainly would sound appealing for a workforce comprised largely of Italian and Jewish immigrants from around the Humboldt Park neighborhood.From a more cynical perspective, though, workplace perks were also routinely a strategic ploy to help squash union unrest.

Over time, predictably, some of the extravagances of the Franklin plant began to fade away, and labor disputes rushed back in like the tides. In one of the most heated, during the early days of World War II, 800 members of the Candy and Confectioners Workers Union walked out of the Franklin factory to the picket line. By that point, they were demanding a 20-cent per hour raise for the men, and 12-cent raise for the women. The company wouldn’t go above 5 cents. No game of rooftop baseball was going to solve every problem.

The plant would remain Bunte’s home for 40 years in total. After its closure in 1961, the building was quickly converted into a high school, Westinghouse High, and remained so until its demolition in 2009. The current Westinghouse High School football field now sits where the Bunte factory once stood.

The Joys of Prohibition

Presiding over the Franklin Street plant in its early, happier days, Theodore and Charles Bunte probably couldn’t believe their good fortune. Their expensive new factory had opened almost simultaneously with the rise of Prohibition, and while a law about alcohol consumption wouldn’t seem particularly relevant to the candy trade, sales numbers quickly indicated otherwise.

“The billiard parlors and cigar stores are becoming formidable competitors of confectionery stores in the sale of candies,” Theodore Bunte told reporters in 1920. “Instead of ordering liquor between games, pool and billiard players eat candy. A man who had the temerity to eat candy in a pool room once would have been thought a mollycoddle. Since prohibition, the pool rooms have built up an immense candy business. We have been shipping candy in carload lots to many cities to supply this new trade.

“The billiard parlors and cigar stores are becoming formidable competitors of confectionery stores in the sale of candies,” Theodore Bunte told reporters in 1920. “Instead of ordering liquor between games, pool and billiard players eat candy. A man who had the temerity to eat candy in a pool room once would have been thought a mollycoddle. Since prohibition, the pool rooms have built up an immense candy business. We have been shipping candy in carload lots to many cities to supply this new trade.

“Women in the past have been the mainstay of the candy trade,” he added. “But it is a matter of trade statistics that men have become the nation’s greatest candy eaters since bone-dry prohibition went into effect. The candy habit has superseded the whiskey habit.”

It was the perfect one-two punch. Men discovered a joy of candy as soldiers, then found their alternative vices taken away a short time later. Bunte’s fan base essentially doubled overnight.

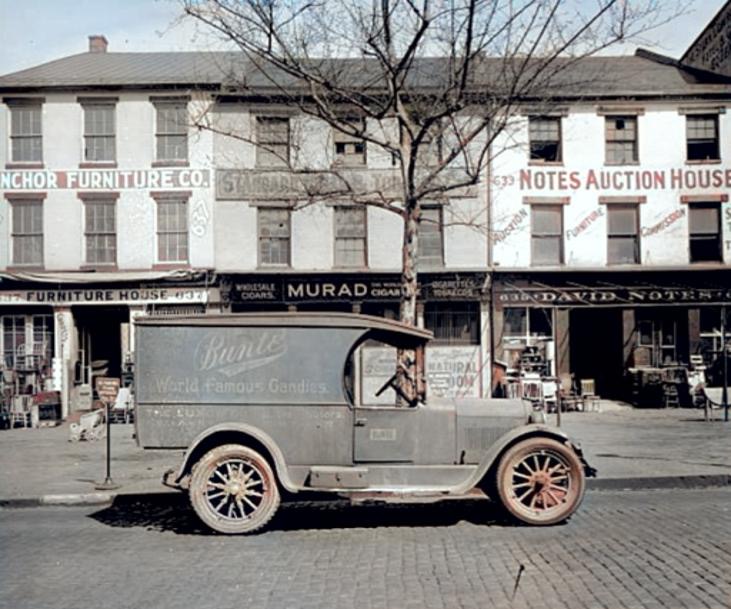

[Bunte Brothers delivery truck, c. 1920s]

Even the rise of major local, low-priced confectionery competitors like Curtiss and Mars didn’t do much damage to Bunte’s bottom line in the ‘20s. Former Bunte associates E. J. Brach and George Williamson (creator of the Oh Henry! bar) were thriving, too. There was room for everyone. The battleground was now less about spurring interest from the consumer, and more about figuring out how best to funnel their money into the company coffers.

Working with advertising manager John C. Blackmore and ad agency Vanderhoof & Co., Charles Bunte put together a unique marketing strategy. When you make literally hundreds of different types of candy, trying to promote them all would be a senseless enterprise. Instead, Bunte advertised only a select few main products, with an emphasis always on the Bunte name itself.

“The policy,” according to that 1921 article by Duane Wanamaker in Advertising and Selling, “has been to pick out leaders and feature them strongly in connection with the name ‘Bunte,’ trusting to the high quality of the goods to awaken the public taste to a point where ANY confectionery with the name Bunte on it meant super-goodness.

“The policy,” according to that 1921 article by Duane Wanamaker in Advertising and Selling, “has been to pick out leaders and feature them strongly in connection with the name ‘Bunte,’ trusting to the high quality of the goods to awaken the public taste to a point where ANY confectionery with the name Bunte on it meant super-goodness.

“ . . . The Bunte people have largely been able to impress the dealer the same way. That is why they very often sell a dealer his entire stock, from box goods to penny pieces, because that dealer knows that everything Bunte makes is good and that the public will buy on the strength of the name Bunte.”

One of Bunte’s biggest hits with dealers in the 1920s, however, didn’t even bear the company name. Theodore Bunte had filed for a patent on a candy cane making machine in 1921, and within a few years, Bunte was sending out thousands of the seasonal delights, wholesale, to grocers and druggists across the country. Prior to this, most Christmas candy canes were made specially in candy shops and in small batches. Bunte helped make the striped candies ubiquitous, and it helped them pay out those Christmas bonuses in the process.

[1915 issue of the trade magazine Candy & Ice Cream, featuring a front page Bunte ad]

[1915 issue of the trade magazine Candy & Ice Cream, featuring a front page Bunte ad]

Chase’d Into Obscurity

If the 1920s offered the perfect storm of good factors for success, the 1930s clearly balanced out the equation. The national economic collapse aside, Bunte also began losing pace with its competitors in the candy bar era, most of which were willing to use cheaper ingredients while Bunte stubbornly clung to its “first requisite.”

The death of Charles Bunte in 1932 was a gut punch, and the end of Prohibition ended that happy side hustle, as well. After regularly totaling sales approaching $7 million annually through most of the previous decade, they were lucky to manage half that amount in the first few years of the Depression. The company’s stock faded similarly.

By the late ‘30s, there were signs of a bounceback, but any hopes of recapturing its old standing in the marketplace seemed bleak. Most of Bunte’s wide scale trade was tapped out, and it became more of a local Midwestern entity in its final years.

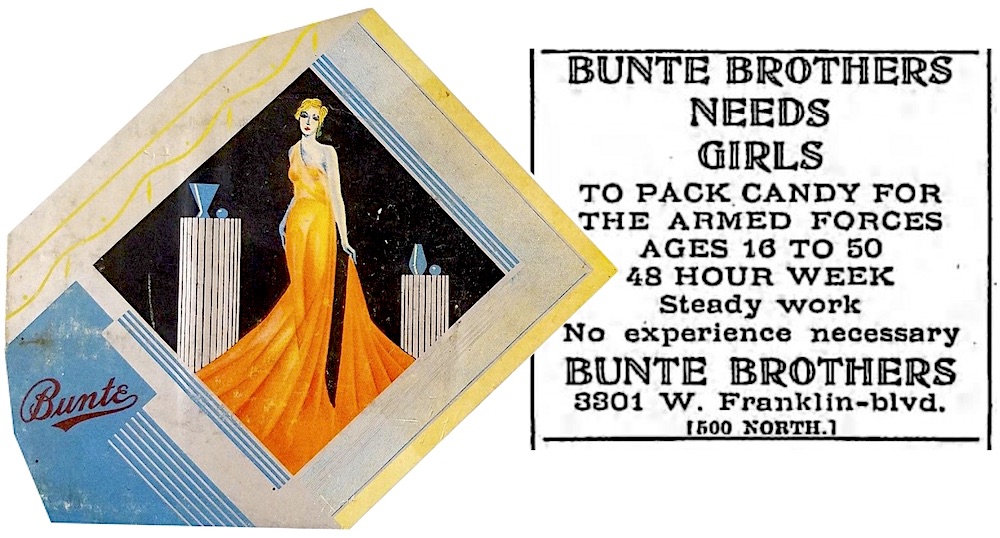

Theodore Bunte’s death in 1941, just before the U.S. entered the war, forced a far less ceremonial passing of the torch to a third generation. The company carried on with Theodore’s son Ferdinand as president, but the second rendition of Ferdinand Bunte couldn’t quite capture the magic that his grandpa once had. Bunte was again a supplier to the troops during WWII, but by the start of the next decade, they were fielding calls on a merger or buyout to save the sinking ship.

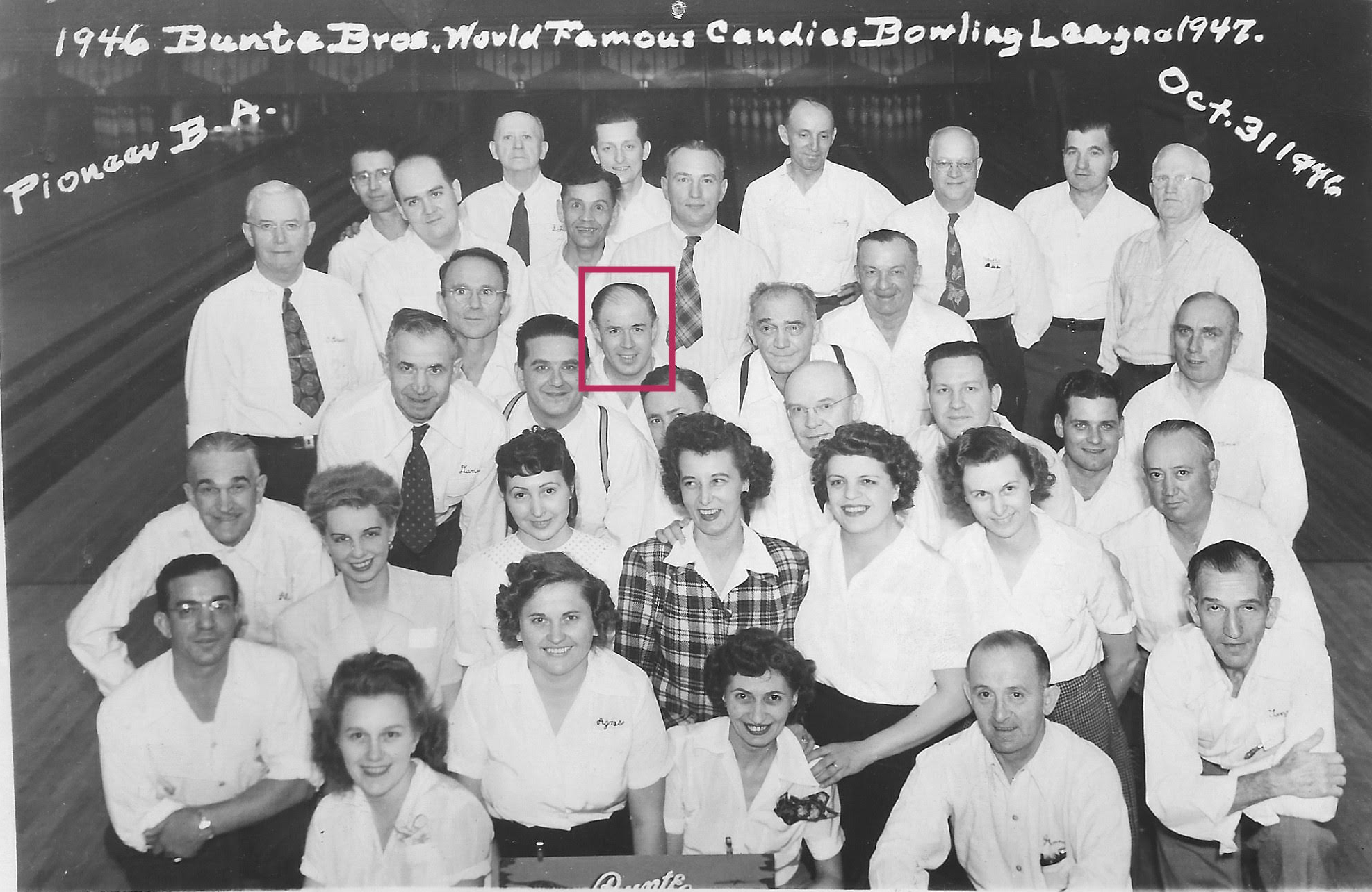

[Above: Packaging and newspaper ad seeking workers, 1940s. Below: Photo of the Bunte factory’s men’s and women’s bowling teams, 1946. This original image was shared with the Made In Chicago Museum by Linda Uhl, whose father, Bunte employee Edward Verner, is highlighted in the image inside the red frame.]

The Chase Candy Co. of St. Joseph, Missouri, eventually backed up the Brinks truck in 1954, and Ferdinand Bunte No. 2, who was 60 years old by this point himself, accepted the deal. Unlike his predecessors, he claimed he had no one in the family willing to carry on the business.

Chase initially agreed to keep Bunte in operation as a subsidiary, and the Franklin Street plant remained open for a few more years. Whereas Bunte had once seemed destined for confectionery immortality, however—a la Hershey or Mars—it was now clear that the story would have a imminent and final conclusion.

The last ugly straw was a lawsuit filed in 1961 by Trans World Airlines, claiming that Bunte-Chase was deeply in debt and unable or unwilling to pay for the past year’s air transportation costs. The Chicago factory was shuttered shortly thereafter.

The last ugly straw was a lawsuit filed in 1961 by Trans World Airlines, claiming that Bunte-Chase was deeply in debt and unable or unwilling to pay for the past year’s air transportation costs. The Chicago factory was shuttered shortly thereafter.

Sadly, no one has been able to enjoy a proper, freshly packaged Tango or Diana confection for nearly 60 years now. As such, Bunte’s place in Chicago’s candy history, let alone America’s candy history, has faded into obscurity. We choose to remember them, then, as Advertising and Selling magazine did 100 years ago.

“Among Chicago’s candy manufacturing firms, none has contributed more to building up the city’s prestige at home and abroad than the House of Bunte, whose rise from small beginnings to a commanding position in the candy industry is a romance of business.”

Sources:

Chicago’s Sweet Candy History, by Leslie Goddard

“1905 Historical Sketch of Chicago’s Confectionery Trade” – Cook County IL GenWeb

“Bulk Candy Advertising That Whets the Public Taste” – Advertising and Selling, Vol. 31, 1921

“Ferdinand Bunte” – Historical Encyclopedia of Illinois, Vol. II, 1926

“Carrying Confectionery” – The Pharmaceutical Era, Jan 1893

“Bunte Bros. & Spoehr” – The Dispatch, Oct 7, 1899

Report of the Factory Inspector of Illinois, 1894

“Wealthy Chicagoan is Taken at Pier as a Bold Smuggler” – Chicago Tribune, May 6, 1910

“Ferdinand Bunte Dies in Germany” – Chicago Tribune, July 24, 1920

History of Chicago: From the Earliest Period to the Present Time, by A. T. Andreas, 1886

“Candy Supplants Highballs in Pool Rooms in Prohibition Era” – Daily Ardmoreite (Oklahoma), July 20, 1920

“State Street” – Chicago Tribune, December 24, 1876

“Bunte Gives Reasons for Sale of Stock” – Chicago Tribune, October 21, 1953

“T.W.A. Sues Bunte Bros. Candy Firm” – Chicago Tribune, Aug 11, 1961

The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets, 2015

Candy and Ice Cream, Vol. 26, 1915

“Bunte Brothers” – Manufacturing and Wholesale Industries of Chicago, 1918

“Ask Geoffrey Baer”: Chicago Tonight, WTTW

“An Appreciation and a Prophecy” – Chicago Tribune, June 3, 1917

“Merger Steps Taken By Two Candy Firms” – Chicago Tribune, October 20, 1953

Archived Reader Comments:

“I can remember the Bunte plant about 4 blocks east of where I lived as a kid. It closed and became Westinghouse H-S” —Anon, 2020

“I just found a Bunte Brothers 3 lb. tin in my attic. Round tin 10 inches in diameter, with bouquet of flowers on the top. Says Bunte Brothers Chicago U.S.A. on the rim of the lid. My family has lived in this house over 100 years, so I am not sure when it was placed in the metal trough with an old heavy door over it. No one left to ask.” —Marge Bowton, 2019

“I am trying to update our discontinued candy binder at the candy store I work at and I cannot find any information about the Blizzard Bar that was made by Bunte. I found a photo of an old ad in a catalogue selling the Blizzard Bar to shop owners but it didn’t give me any information as to what it was. Would you happen to know what it consisted of? Thank you! Fantastic article by the way… SO informative and interesting!” —Kelsey (from Canada), 2018

“I bought an old Bunte Brothers candy tin in Germany yesterday just because it looked so nice and I wanted to find some information on that company. So happy to find this information – thank you so much for that. The name of the candies is RIVERRO – maybe you have some information for me when the tin was produced? Looking forward for some more information and many greetings from Germany – the home of the Bunte brothers…” —Katharina, 2018

“This is one of the most informational articles that I have EVER read…….I attended George Westinghouse Vocational Area High School located at 3301 W. Franklin Blvd., Chgo., IL (formerly Bunte Brothers Candy Co.) located in Humboldt Park…….I am such an avid lover of finding out about “history” of things…….I stumbled upon the article, thought it was too long to read BUT now I am so glad that I read it know the HISTORY of my High School…..I have so-o-o-o, many great memories of attending H.S. in that building. I LOVED THIS ARTICLE!!!

” —Penelopee Bankhead-Finley, 2018

” —Penelopee Bankhead-Finley, 2018

“Looking for a picture of the store at 720-728 W Monroe where my Grandmother worked.” —Barbara, 2018

“ Wonderfully useful information! We are a museum in Milwaukee that has about two dozen tins and boxes of the Bunte Co. with a half dozen always on display, so it is great to know more of the history.” —Chudnow Museum of Yesteryear, 2017

Wonderfully useful information! We are a museum in Milwaukee that has about two dozen tins and boxes of the Bunte Co. with a half dozen always on display, so it is great to know more of the history.” —Chudnow Museum of Yesteryear, 2017

“Ferdinand and Gustave are my great great great great uncles lol” —Christina, 2017

“I just discovered my Great Grandfather had a Bunte candy route in Chicago maybe in the early 1920’s. ” —Nancy, 2017

“I have a round candy tin of my Mom’s I kept when she passed. It has a light green lid with dark green trim. On the side of the lid it says “Bunte Brothers Chicago U.S.A.., on the other side it says 3 lbs. net wt. The container itself is dark green with Canco stamped pm the bottom. It stand 2 in. high and is 9 3/4 in. across the top. It has red roses painted in the middle of the lid. My Mom’s middle name was Rose, so I am thinking it could have been a gift from my Dad. They met about 1937 or 38 and married in 1940. Of course she had 8 brothers and it could have been anyone of them. She had kept it all these years and stored some of her sewing things in it.” —Neal Rakestraw, 2016

Just found a glass bottle with Bunte Chicago embossed in glass. Is this from the cough drops?

I opened a Feb 1942 army ration can earlier today and found four Bunte hard candies inside. Two lemon lime and two butterscotch. They were as fresh as could be expected and having been in an air tight can for 82+ years was a good safe place for them. Some very wonderful old time candies. Found this site with the company history this evening and was a good read. Thank you!

It’s flat but I found A Bunte opera Almond fluff box in my grandmother’s things after she passed. We live in Texas

I have a Bunte Brothers Chicago U.S.A. round tin from my Grandmother. It is gold with a bouquet of flowers on it. Does anyone know it’s value?

I have a one pound tin.golden color pond and trees.Contains 1943 + letters of great grandfather.

My great grandfather (who was a lawyer) worked for Bunte Brothers in1910-1920’s(ish). My grandmother talked about the Diana Stuffs and visiting the candy factory as a young girl. Thank you for the historical article!!

These were my 5th great grandparents. It is a wonderful article. My grandmother and her father lived in Philadelphia and were part of the Bunte family but the name had been changed to Buntz. My grandmother did not even know her own mother’s name but she did have a dish of the hard candies with the soft center on her table in a candy dish. No one knew that she came from this dynasty, especially because they grew up so very poor. Thank you for the pictures and for helping my genealogy research.

I too am related. Are you willing to connect??? 😊

The Tango bar they made was a wonderful item.

Mars candy co. should remake and bring them back.

I have 5 of the Diana Bunte tins that my Mom used as canisters. They were from my Grandparents. Also German immigrants.

I just bought a wooden shipping crate that says “from Bunte Brothers Chicago USA” in a classic German font. The ends are both marked “Halloween”! Interesting to know the history. $5 well spent.

I have an orangy-red 1 pound paper Bunte box with the words “A Little Everything in Chocolates” on the top. On the bottom of the box it lists is printed “This package Contains the Following pieces. Subject to unavoidables which sometimes cause slight changes’ followed by a 3 column list of 21 different kinds of candy. Any museum interested in displaying this box or adding it to your collection, please reply by email.

I have a Bunte Colonial Chocolate box with a Colonial Man and women on the top of box. Not sure of date?

Hello, I have a beautiful advertisement bookmark. Its back side reads: “BUNTE Goods bearing this Trade Mark may be relied on as being of Superior Quality AND FREE FROM ADULTERATION Retailers should only buy such goods as will retain the trade of the most desirable customers BUNTE BROTHERS 139 and 141 West Monroe Street CHICAGO, ILL” . Top side of the bookmark that I’m willing to sell depicts a picture of beautiful girl, ribbon and flowers.

I have a bunte brothers Caramel suckers box. 80 count kind of a burnt orangish butterscotchish color approx 10×6 1/2 by 2 1/4 “

Would like to date it if possible.

Thank you

Bill

I remember the Bunte Company once made a candy called Rose Gels. They were shaped like a chocolate drop, but contained a semi-gel like raspberry flavor. Wiebolt’s Department store always sold them. I learned of Bunte as the manufacturer of Rose Gels from Margie of Margie’s candies in Chicago. I miss them.

For the last 35 years i have lived in Ferd Bunte’s summer home in Powers Lake Wi. Just cut his and his wife Mary’s name out of the concrete floor in the shop i am remodeling. The third generation Bunte i am talking about. Lots of history here.

I too am related to the Bunte Brothers. Are you willing to sell what was cut out?

We have a Bunte Old Tyme Mix 2.5 lbs

It has Christmas Bears on it

Just curious

I have a Bunte Brothers Chicago USA shipping crate. Excellent condition. No date.

wondering if you have any idea of year. It came out of the General Store owned by my

Children’s Great Grandparents.

Thx!

Any interest in selling? I am a decedent of the family 😊

I have a reprint of a 1927 Sears Roebuck catalog, and in their candy section have Bunte’s Tangos and some other candy bar of theirs.

Very informative. My great grandfather was Charles A Spoehr the Spoehr of Bunte and Spoehr. He married Johanna bunte. Their son, Conrad continued in the candy business opened a candy store front in Chicago, worked for various candy companies, including Curtiss where he was instrumental in developing the Butterfinger candy bar

My grandma had a couple of the tin cans in her kitchen and I graduated from George Westinghouse Vocational high school that it was turned into.

Loved the article. I have a rare 1/2 Lb empty early 1900s White House Dutch Cocoa paper tin. Wish I was able to taste some of the original!

Was going to throw the tin out, but think it’s good piece of history to hang on too, or sell to someone else who appreciates good history 🙂

I have a 1# flat Bunte Candy tin. It is navy blue with turquoise lettering & features a spray of yellow flowers with leaves placed diagonally across the top. Is there any interest in buying it?

Great informative article,I just bought an old shipping box that said Bunte brothers ,Chicago.Now I know what they shipped.

I have a tin from 3 lb candy which I would gladly donate to your museum. It is 10” round, golden color with spray of flowers including pink roses in center on lid top. Not great condition but has held buttons for years. Thanks for this informative article.