Museum Artifact: “End of the Trail” Native American Print & Wood Frame, 1925

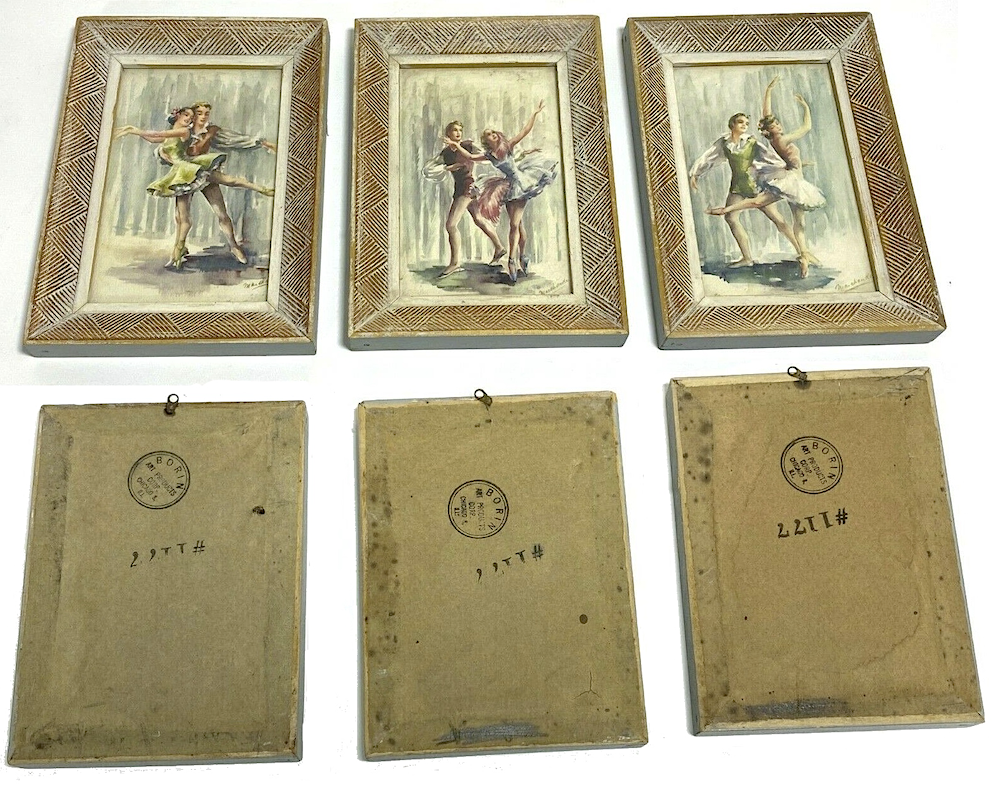

Made By: Borin Manufacturing Company / Borin Art Products Co., 1325 S. Cicero Ave., Cicero, IL

When it comes to talented men of potentially questionable character, some folks say you must learn to “separate the art from the artist”—to appreciate their work on its own merits. It’s not clear if this same philosophy applies to the art dealer, but Nathan Borin at least offers us a challenging case study.

As the founder and president of Chicago’s Borin Manufacturing Company, aka the Borin Art Products Corporation, Mr. Borin became something of a high-roller on the streets of Cicero in the 1920s, back when Al Capone was still running the neighborhood. He had a few other things in common with Capone, too, including a diminutive stature, a sharp business acumen, a penchant for womanizing, and a violent streak—though I suppose we’ll stop just short of calling him a gangster.

As the founder and president of Chicago’s Borin Manufacturing Company, aka the Borin Art Products Corporation, Mr. Borin became something of a high-roller on the streets of Cicero in the 1920s, back when Al Capone was still running the neighborhood. He had a few other things in common with Capone, too, including a diminutive stature, a sharp business acumen, a penchant for womanizing, and a violent streak—though I suppose we’ll stop just short of calling him a gangster.

Mob ties or not, Nathan Borin did manage to become a national tabloid villain for a while, as his scandalous and bizarre separation from his second wife—and the years of court cases that ensued—made headlines from L.A. to Boston. Unfortunately for him, that story didn’t come with any of the cachet or reverence Americans tend to set aside for actual criminal masterminds. Instead, it became the ugly blot that overshadowed the man’s achievements and essentially defined him to the public. “Nathan Borin, of Divorce Case Notoriety, Is Dead,” read the Chicago Tribune headline upon his death in 1956.

As for Borin’s business—it had ostensibly launched as a humble frame and mirror shop in 1920, but really came into its own once Nathan realized he could make a lot more money if he stopped purchasing the commercial art that went into his frames, and instead hired his own in-house artists to produce exclusive prints—including both originals and reproductions of famous works.

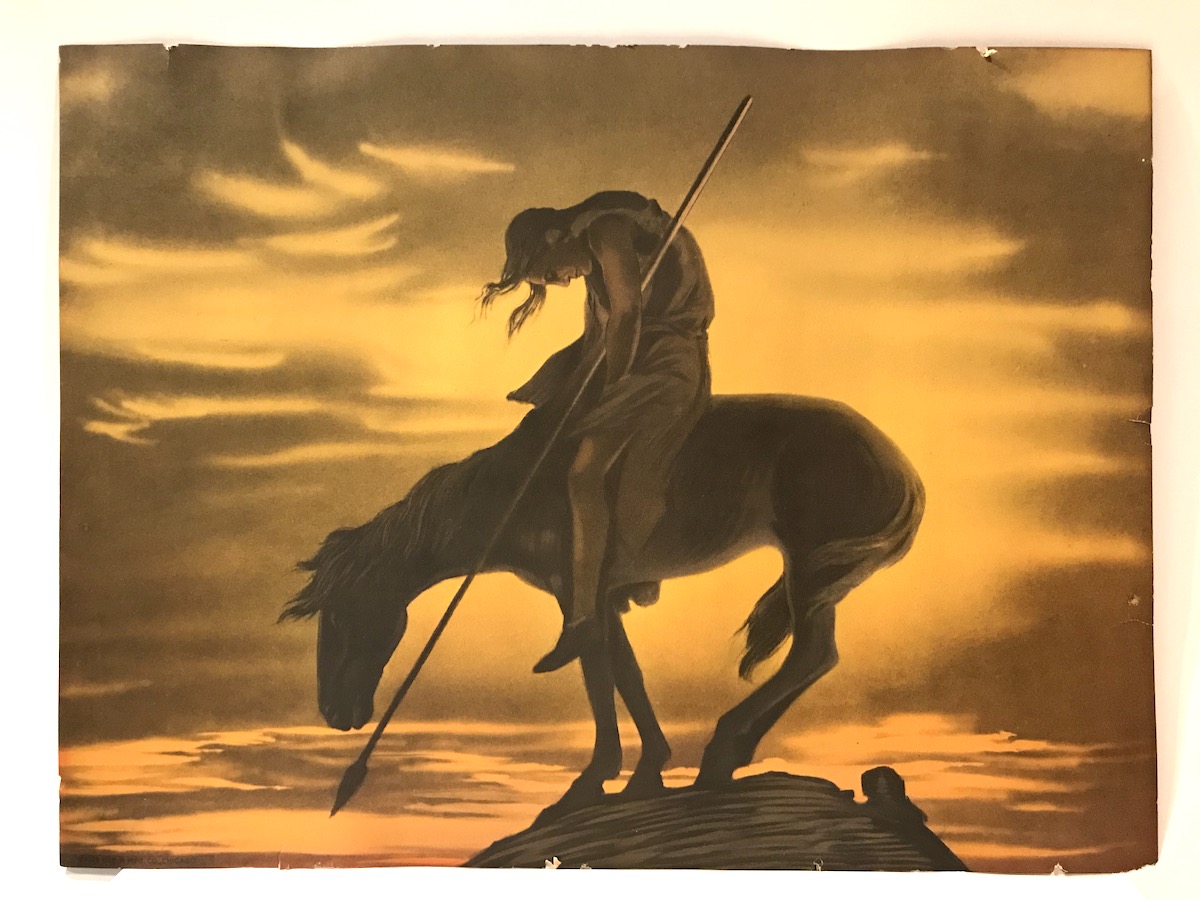

[The 1925 Borin MFG print is based on the sculpture “End of the Trail” by James Earle Fraser (1876-1953)]

The artifact in our museum collection actually falls in-between those two categories, as the colorful 1925 lithograph of a Native American on horseback was not a copy of a famous work, per se, but certainly directly inspired by James Earle Fraser’s popular sculpture of the previous decade, known as “End of the Trail.”

The powerful image—which has since been interpreted by critics as both a symbol of defeat and resilience—wound up crossing over from the art world into popular culture after Fraser unveiled a giant plaster version of the work at a 1915 exposition in San Francisco.

Ten years later, “End of the Trail” had become almost ubiquitous American wall art, with low-cost photos, paintings, and lithograph depictions finding their way into thousands of middle class living rooms. Our museum example is no exception; it was first purchased by my own great-grandparents and displayed in their rural Ohio home during the Depression, and it has continued to hang from one hook or another, across maybe a dozen different homes, ever since—a testament, I suppose, to the decent frame-making skills of our buddy Nathan Borin.

History of the Borin MFG Co., Part I: Setting a Vivitone

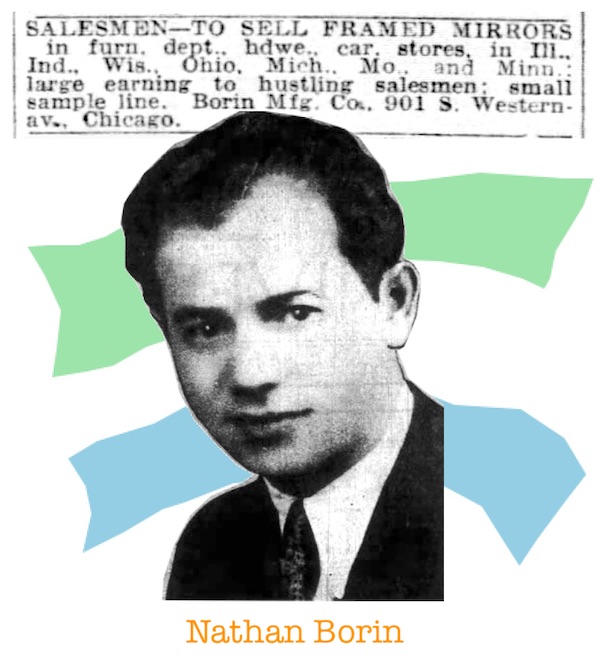

Nathan Borin was a Jewish immigrant and really started out as a textbook example of the American dream realized. Born in Kiev, Ukraine, in 1894 (almost certainly under a slightly different name), he didn’t arrive in the States until 1911, aged 17, speaking mainly Yiddish and equipped only with “hope, imagination, and energy,” according to one account.

Settling in Chicago, he married his first wife Molly in 1917, moved into an apartment at 1236 S. Tripp Avenue in North Lawndale, and became a father three years later, when daughter Pauline was born. At the same time, to support the family, Borin opened up a frame and mirror shop three miles east of his home, at 901 S. Western Avenue in the Tri-Taylor district.

It’s unknown if Nathan himself had carried over a talent for this trade from the Old World, but he supposedly put all of his hours into the effort regardless, “soliciting business daytimes and doing the work at night.” By 1922, he had organized the Borin Manufacturing Company, accumulating $25,000 in capital and actively recruiting “hustling salesmen” to travel throughout the Midwest, lugging around his sample line of “framed mirrors” to pitch to various furniture, hardware, and department stores.

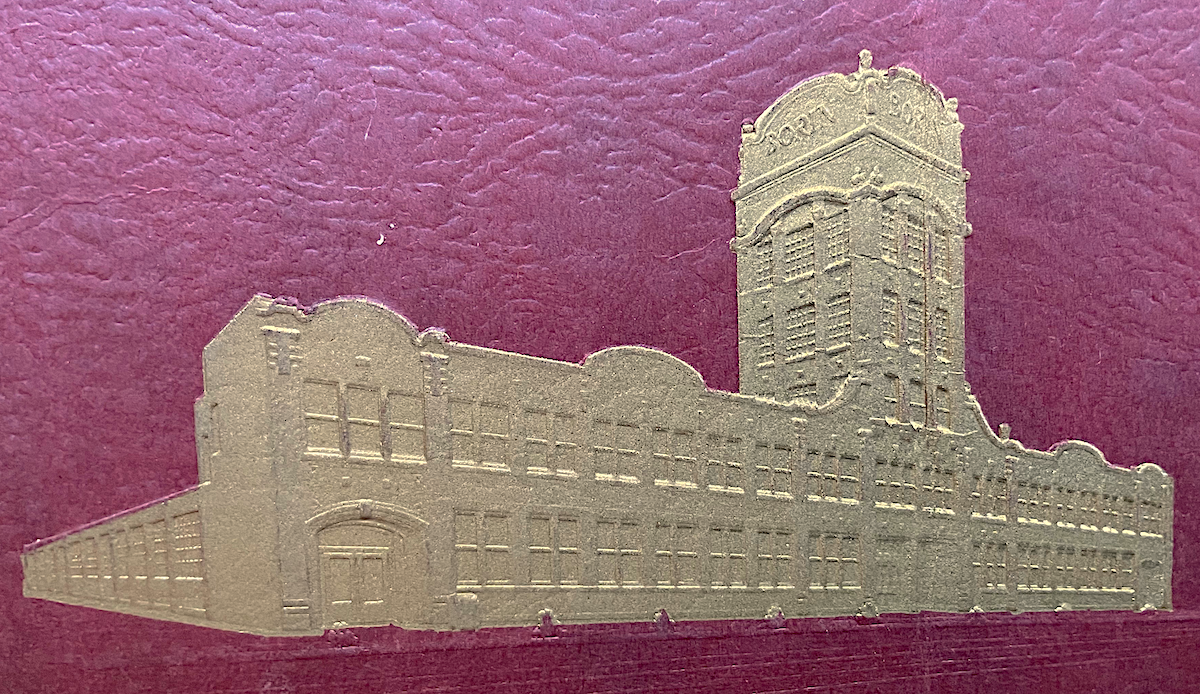

In 1925—the same year printed on our “End of the Trail” artwork—the Borin MFG Co. had miraculously ballooned to a half-million dollar enterprise, and a new dedicated factory was established in Cicero at 1325 South Cicero Avenue, soon recognizable by a six-story brick tower with the BORIN name adorning the top.

According to an article printed years later in the New York Daily News, half of Borin’s early business was in mirrors, “but the most profitable part of it was picture frames and the pictures to go in them. He specialized in framed reproductions of masterworks or of portraits of famous people,” most of which were sold through big department store retailers like Marshall Field & Co., Mandel Bros., and The Fair Store in Chicago, as well as Gimbel Bros. in New York; Jordan, Marsh & Co. in Boston; The Emporium in San Francisco; and J. L. Hudson & Co. in Detroit, among others.

According to an article printed years later in the New York Daily News, half of Borin’s early business was in mirrors, “but the most profitable part of it was picture frames and the pictures to go in them. He specialized in framed reproductions of masterworks or of portraits of famous people,” most of which were sold through big department store retailers like Marshall Field & Co., Mandel Bros., and The Fair Store in Chicago, as well as Gimbel Bros. in New York; Jordan, Marsh & Co. in Boston; The Emporium in San Francisco; and J. L. Hudson & Co. in Detroit, among others.

“His competitors eventually complained he was underselling them and got the picture publishers to cut off his supplies,” the Daily News claimed. “Undaunted, Borin decided on a gamble. He hired his own artists. They produced originals or copies of masters and he developed a new reproduction process.”

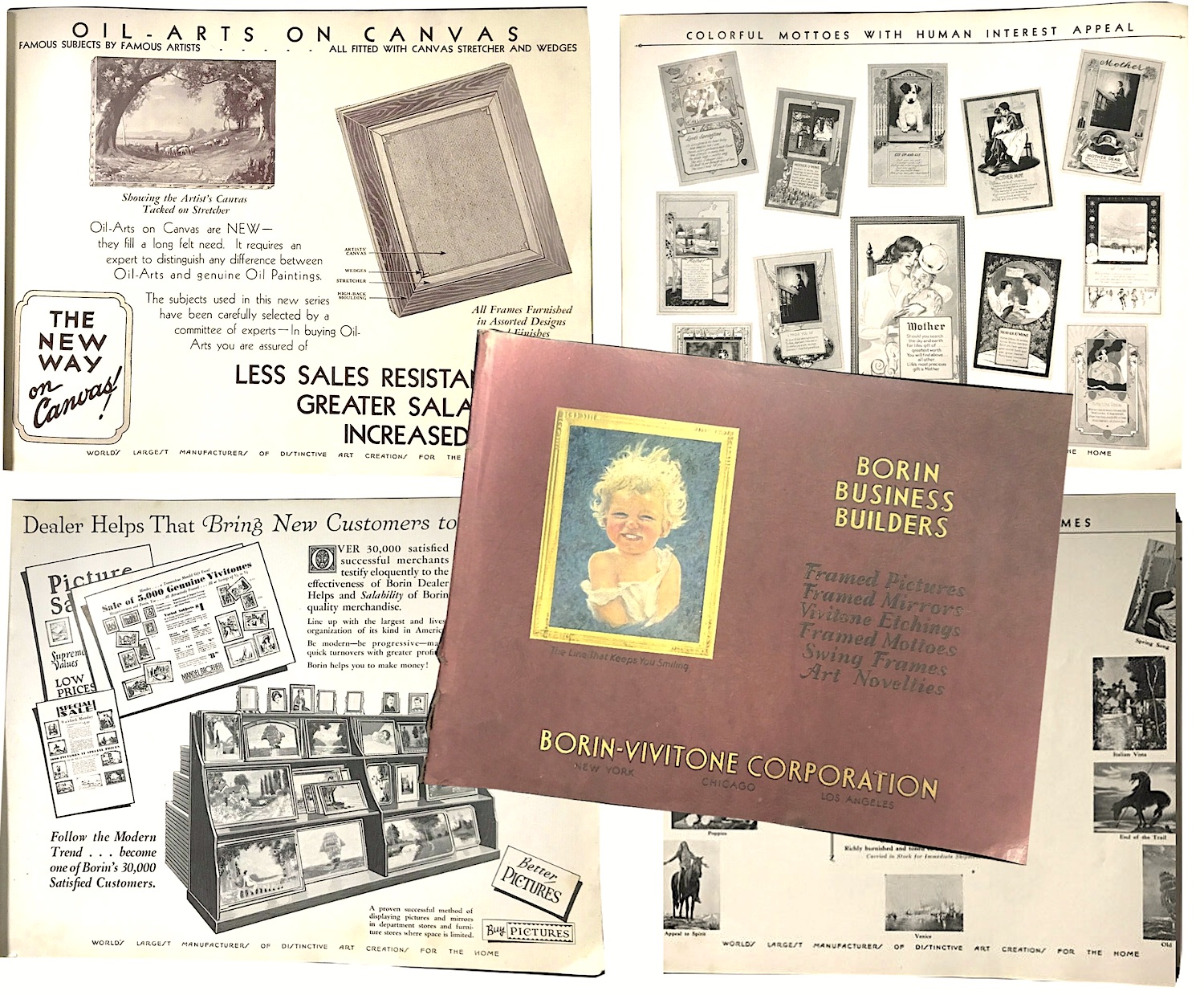

That process, under license from the Aquatone Corporation, was a new type of fast-paced precision engraving known as a Vivitone, which Nathan Borin said could be used to reproduce large quantities of the “finest etchings and mezzotints at such prices [often no more than $1] as to permit them to be in every home.”

[Pages from the Borin-Vivitone Corp. dealer catalog for 1930]

In February of 1929, the Borin MFG Co. was officially re-organized as the Borin-Vivitone Corporation, and capitalized at a whopping $2,000,000. The new organization claimed to be “the largest manufacturer in the United States of framed works of art and decorative art products for home furnishings,” and by that spring, Nathan was setting up distribution hubs in New York and Los Angeles.

“Today, competition is influencing all phases of business life,” the company’s new dealer catalog exclaimed. “To some is it but one measure of success, to others, the measure of failure. . . . It has fallen to this organization and yourself to be Leaders—the ones to whom competition is always keenest—and you have been successful, and we have been successful. By means of quantity production, volume buying organization efficiency, and dealer co-operation, we have cut costs and reduced selling prices. Mr. Dealer, you and the Borin-Vivitone Corporation have become the standard of success.”

Inside the Borin Factory in Cicero, 1930

Not even Wall Street’s meltdown later that year could bring the Roaring ‘20s to a halt for Nathan Borin. While attending some sort of Gatsby-esque party during this same stretch, he found himself pathetically enamored with one of the attendees; a 19 year-old girl named Claire Burman. Nathan was 35 and married with three kids, but if your moral compass is pointing the wrong way anyway, such things will rarely impede your path.

Part II. The Battling Borins

After turning a profit every year of the 1920s, Nate Borin’s fast rising business hit the proverbial wall in 1930, and by 1932, Borin-Vivitone was re-organized again, this time split off into two separate entities both still headquartered at the Cicero offices: the Borin Art Products Corporation and Illinois Art Industries, Inc. While Nathan ostensibly “ran” both companies, his business partner Lorne V. Locker seemed more tuned in to the day-to-day operations, leaving Nathan plenty of time to get sidetracked.

Borin’s personal salary was supposedly $10,000 per year by this point, which equates to about $190K in today’s money; not exactly tycoon cash, but enough to be a very well-to-do man in the early 1930s. Accordingly, he and his family had recently “moved on up” to a much nicer apartment on the North Side, at 2920 Commonweath Avenue in Lake View, giving Nathan a considerable commute down to the factory in Cicero. There was now even more fertile ground for a double-life to emerge.

Borin’s personal salary was supposedly $10,000 per year by this point, which equates to about $190K in today’s money; not exactly tycoon cash, but enough to be a very well-to-do man in the early 1930s. Accordingly, he and his family had recently “moved on up” to a much nicer apartment on the North Side, at 2920 Commonweath Avenue in Lake View, giving Nathan a considerable commute down to the factory in Cicero. There was now even more fertile ground for a double-life to emerge.

At the aforementioned party in which Nate first encountered the aspiring teenage actress Claire Burman, the young lady apparently “didn’t pay much attention to him. He was an ‘older man’ and not her type,” the New York Daily News later reported. “Anyway, she was busy studying dramatics and voice. In Hollywood she had met many movie people and nursed a desire to get into pictures.”

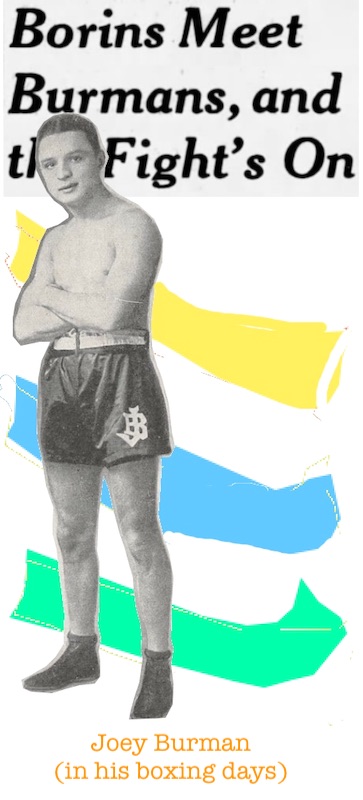

Claire’s brother Joey Burman was a former bantamweight boxing champ, and while the family was based in Chicago, his success had helped them score a second house in Hollywood, supposedly right across the street from Greta Garbo’s. As for her own credits, Claire Burman’s biggest claim to fame would ultimately be the time she almost got the role of a “panther woman” in a 1932 version of the The Island of Dr. Moreau. Even so, she could talk the talk and walk the walk like a film star.

For this reason, according to that same Daily News story, Nathan Borin “was as persistent in his conquest of Claire [Burman] as he had been in his business,” sending her flowers, jewelry, minks, etc. “He swept aside all her objections, including that of the difference in ages [and presumably the whole wife and kids bit?], and finally they were married—on Nov. 11, 1933, in Agua Caliente, Mexico.”

For this reason, according to that same Daily News story, Nathan Borin “was as persistent in his conquest of Claire [Burman] as he had been in his business,” sending her flowers, jewelry, minks, etc. “He swept aside all her objections, including that of the difference in ages [and presumably the whole wife and kids bit?], and finally they were married—on Nov. 11, 1933, in Agua Caliente, Mexico.”

The name of that Mexican town literally translates to “Hot Water,” which seems quite appropriate considering what they’d just gotten themselves into.

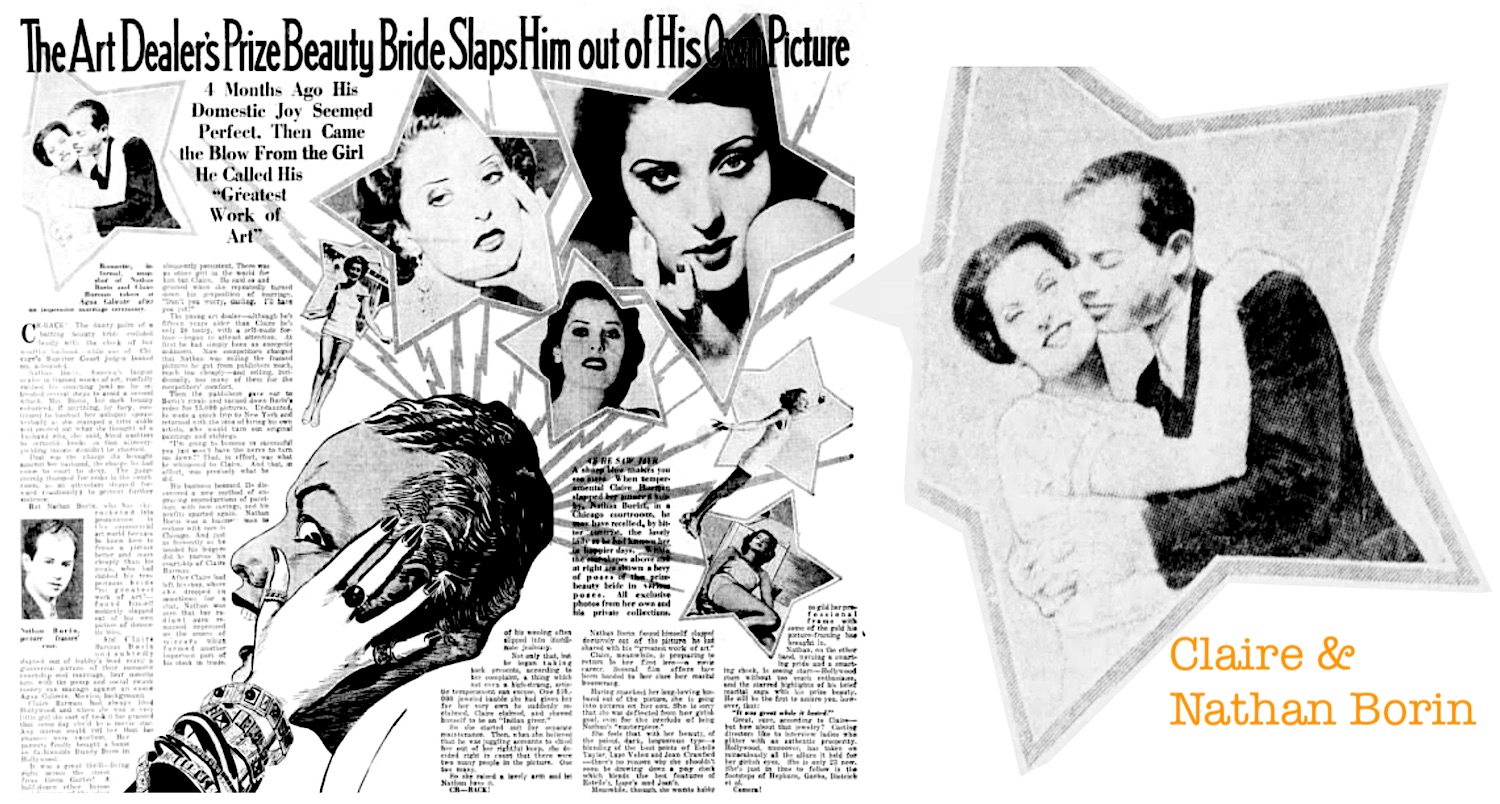

It’s unclear when Nathan Borin officially divorced his first wife Molly, but unsurprisingly, his next marriage had a very short honeymoon period. In fact, while Nathan publicly referred to his new bride as his “greatest work of art,” Claire Borin later alleged that he actually told her, on their wedding night no less, that “I only married you to get even with you because you didn’t want to marry me.” Things would continue along a similar trajectory from there.

In February of 1934, just three months into the marriage, Claire Borin filed suit against her new husband, claiming Nathan had “beat her and threatened to throw acid in her face.” She also demanded he return a $5,000 bracelet he’d given her and then taken back. At their court hearing, for good measure, “she walked over to her husband, whispered something in his ear, and then clouted him.”

“Thus the astonished judge was witness to the first battle of the war,” the Daily News noted, referring to the ongoing series of court appearances that would earn Nathan and Claire a lasting nickname in the press: the “Battling Borins.”

[A sensational recounting of the first big Borin divorce trial in 1934, as published in the El Paso Times and Philadelphia Enquirer, among other papers]

Despite reconciling after the 1934 incident, the troubled couple would take legal action against one another repeatedly over the next 15 years, resulting in well over 100 increasingly bitter and sometimes absurd court appearances.

In 1935, Nathan filed suit in a Los Angeles court claiming his wife had abandoned him to hitch up with a Hollywood producer, Ephraim M. Asher, which she and Asher both denied. Claire came back and sued Nathan in Chicago for alimony payments.

“I shall step aside and sacrifice my love for her,” Nathan said at the Chicago trial, “if she will admit she is in love with another man. All I want is to see her happy, even if I lose her in doing so.”

“I wouldn’t go back to him for $50,000,000,” Claire retorted.

“I wouldn’t go back to him for $50,000,000,” Claire retorted.

Even the Mexican government got involved, filing its own suit demanding the Borins annul their marriage. Apparently, far too many Hollywood types were getting hitched in Mexico and then “discrediting” the practice with divorces and scandals.

Nobody seemed to want to see them together, and yet, Nathan and Claire elected to reconcile once again.

Claire next filed for divorce in 1937, citing cruelty, but the Battling Borins just couldn’t quite quit one another, and things were inevitably complicated by the birth of a child—a daughter named Bonnie Joy—born in 1939. After that, and through most of World War II, there was at least a respectful lull in the saga. By 1945, though, the soap opera returned. Claire again filed for divorce, saying Borin “hit her, twisted her arm, sent her and Bonnie Joy to Florida, and threatened her with phone calls and telegrams.”

During a few hearings that fall, Nathan’s lawyers alleged that Claire had called employees at the Borin Art Products Company to tell them their boss was a “moron.” She had supposedly said the same thing to Bonnie Joy, who then “repeated it to the neighbors.” In the end, Nathan was required to pay his estranged wife’s rent, plus $150 in monthly support and various other court costs.

“She’s an atom bomb, all right,” he said after the ruling—a bit of an insensitive metaphor, considering this was literally weeks after Hiroshima and Nagasaki. “But I’ve still got a lot of fight in me.”

“An atom bomb, am I?” Claire fired back. “Well, I used to fall for him every time he came crawling back to me, but never again. Hmph. I have to laugh when I remember how he called himself the ‘Great Russian Lover.’”

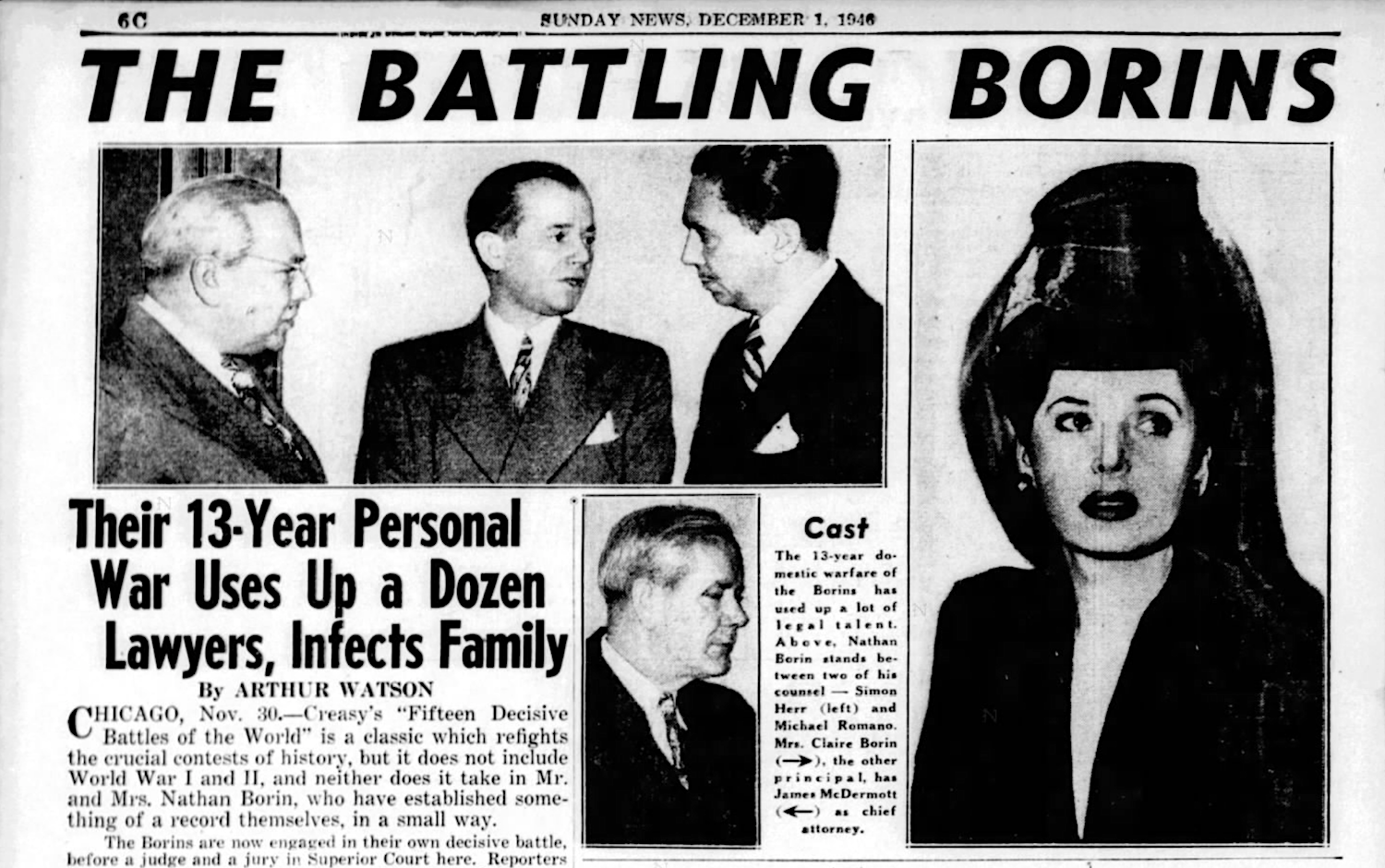

[The “Battling Borins” tagline, which first appeared in 1937, was well known to readers across the country when the New York Daily News ran a 3-page story on the saga in 1946]

Divorce proceedings carried into 1946, and the circus-like atmosphere unsurprisingly led to more embarrassment, as Claire and Nathan each named names and aired every available bit of dirty laundry while accusing one another of various tawdry pulp fiction affairs with actors and call girls; from steamed up limos in Lincoln Park to swanky hotels in New York and Miami. The first Chicago judge assigned to the case, John Sbarbaro, disqualified himself, claiming he felt too biased against BOTH sides.

“This evidence is the foulest I have ever heard in a divorce court,” he said. “The Borins not only battle, but they exude a virus which causes numerous counsel, ordinarily gentlemanly lawyers, to fight among themselves.”

While most of Claire’s family—the Burmans—were at her side, two of her sisters, Lillian and Nancy, inexplicably opted to testify on Nathan Borin’s behalf. This led to a physical altercation—a family brawl, really— in broad daylight, outside the Sherman Hotel at Clark and Randolph, with hundreds of random Chicago passersby looking on. It supposedly started with Claire and Lillian having a sisterly tussle, followed by their forming boxing champ brother Joey Burman—in defense of Claire—taking a slug at Lillian’s husband, 54 year-old Dr. Julius Isaacs. Another brother, Dave, apparently hit the good doctor with some sort of pipe, and was later charged with assault for the attack.

While most of Claire’s family—the Burmans—were at her side, two of her sisters, Lillian and Nancy, inexplicably opted to testify on Nathan Borin’s behalf. This led to a physical altercation—a family brawl, really— in broad daylight, outside the Sherman Hotel at Clark and Randolph, with hundreds of random Chicago passersby looking on. It supposedly started with Claire and Lillian having a sisterly tussle, followed by their forming boxing champ brother Joey Burman—in defense of Claire—taking a slug at Lillian’s husband, 54 year-old Dr. Julius Isaacs. Another brother, Dave, apparently hit the good doctor with some sort of pipe, and was later charged with assault for the attack.

In court, Lillian Isaacs called her brother Joey a “no good bum.”

“I ain’t no bum,” the ex-fighter protested. “The old doc swung at me first, so I hit back. God gimme two hands. I don’t need nothin’ else. I ain’t scared of nothin’ or nobody.” Besides, Joey added, “I pulled my punches. After all, he’s an old man.”

As the actual divorce proceedings continued, Claire’s attorney claimed that Nathan Borin’s only interest during the entire marriage was “consorting with women and spending his time in night clubs.”

Borin, “who has worn a different suit nearly every day and is partial to impressionistic neckties,” according to the Daily News, “got up to admit that he sometimes entertained women, but they were always business associates or friends of his wife.”

The Borins’ maid testified on Claire’s behalf, claiming Nathan had bribed her to join his own defense.

“This is going to be the dirtiest divorce case on record,” Borin allegedly told her. “Neither I nor Mrs. Borin will get custody of our daughter when it’s over. She’ll be put in a home.”

Claire denied all accusations of adultery, and her sister Elaine—who had defended her alongside the two ruffian brothers— said that “Claire was just Borin’s showpiece. He liked to be seen with her. She gave him the appearance of respectability.”

It wasn’t until 1949—16 years after their ill-advised wedding—that Nathan and Claire Borin finally finalized the paperwork on the divorce. Poor little Bonnie Joy [seen below] went with her mom, who went on to marry two additional millionaires. Nathan, predictably, found another girl half his age and got into a whole new vat of hot water.

III. Meanwhile, Back at the Frame Shop

In between his various alleged romantic sojourns, Nathan Borin was presumably setting aside at least some of his time to keep the machines running at the Borin Art Products plant, although—as noted— longtime associates like Lorne Van Locker likely had more to do with it.

In the heart of the Depression, the factory apparently took on a very public presence in Cicero, as locals would gather in line outside the plant, rain or snow, to collect scrap wood that the company offered for free as kindling. Locker (who was sometimes listed as the president of Illinois Art Industries, Inc.)—along with vice president William F. Hofert and production manager A. L. Hovey, among others—also managed to keep their own employees somewhat encouraged after some rough losses.

In the heart of the Depression, the factory apparently took on a very public presence in Cicero, as locals would gather in line outside the plant, rain or snow, to collect scrap wood that the company offered for free as kindling. Locker (who was sometimes listed as the president of Illinois Art Industries, Inc.)—along with vice president William F. Hofert and production manager A. L. Hovey, among others—also managed to keep their own employees somewhat encouraged after some rough losses.

“Since the beginning of the year, we’ve increased our payroll approximately 150 per cent over a similar period last year,” Hovey told the local newspaper Cicero Life in May of ’34. “As far as the outlook is concerned, it is bright, and we are anticipating a fairly good summer and fall.”

Three years later, despite its best efforts, management was faced with growing dissent from its workforce, culminating in a “sit-down” strike by 150 employees (including 40 girls) in March of 1937, organized by the C.I.O. (Congress of Industrial Organizations). With Nathan Borin caught up, as usual, in marital strife, another one of his officials, M. R. Ivers, spoke to the press in his absence, stating that the “minor disturbance” was settled within a few hours. He also blamed four new workers at the plant for riling up the others.

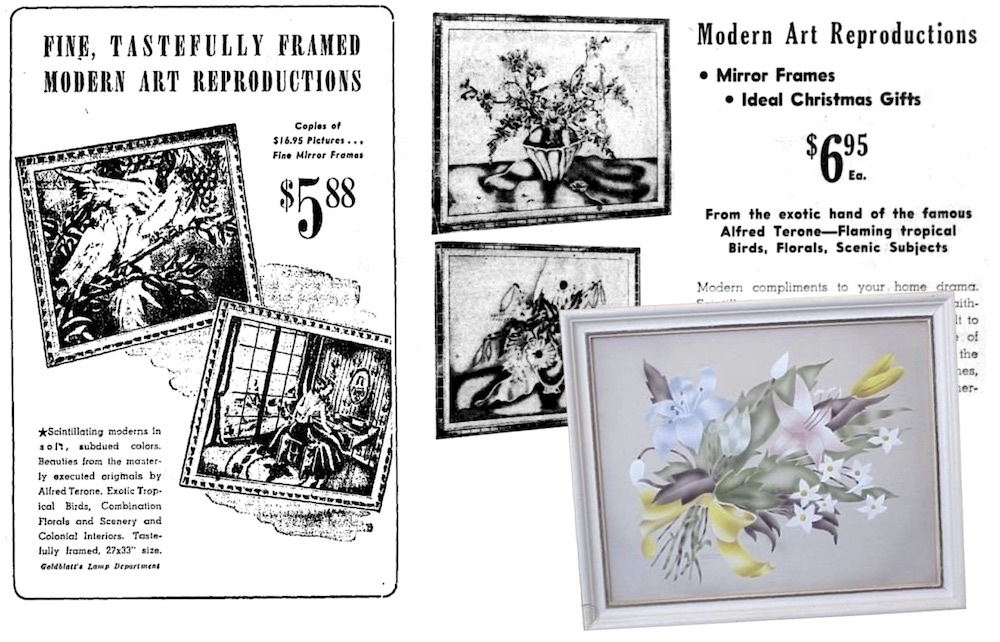

As best we can tell, Borin Art Products was able to continue production during World War II, with advertisements of the period often touting the skills of one particular employee: an artist named Alfred T. Terone. Both Terone (1913-1979) and his wife Cecelia (1916-1999) were graduates of New York University and highly trained artists in their own right, but they came to Chicago in pursuit of a new industrial sort of commercial art; airbrushing pictures for mass-produced prints and re-creating classics as affordable $5 wall art, backed by brown paper and mounted in machine-produced frames. It wasn’t work that was going to get them a gallery at the Art Institute, but surprisingly, it did offer some notoriety, as Terone’s “Hand-Colored Beautytone” prints became Borin’s biggest sellers.

[Two newspaper ads from the early 1940s tout the skills of Alfred T. Terone in reproducing classic art works. He and his wife Cecelia also produced original prints of their own, like the example in the foreground]

“From the exotic hand of the famous Alfred Terone,” read one 1943 ad, “flaming tropical birds, florals, and scenic subjects. . . . Modern compliments to your home drama. Scintillating in their mirror frames . . . so faithfully reproduced from originals, it’s difficult to tell them apart. If your furnishings are of maple, you’ll be more than interested in the Colonial Interior subjects. Soft, subdued tones, rich in ancestral heritage. Each one a generous size. 28×33”.”

IV. Burning Down the House

In contrast with Terone’s relaxing floral prints, unfortunately, was Nathan Borin’s familiar instability. As would come to light years later, Borin was making false claims on his taxes through much of the early 1940s, leading to a long line-up of deficiencies and penalties. As no coincidence, the Borin Art Products Corporation was dissolved in 1943, as Nathan Borin became the sole partner in a new version of the Borin Art Products Company, with his wife/combatant Claire’s personal stock plundered in the process.

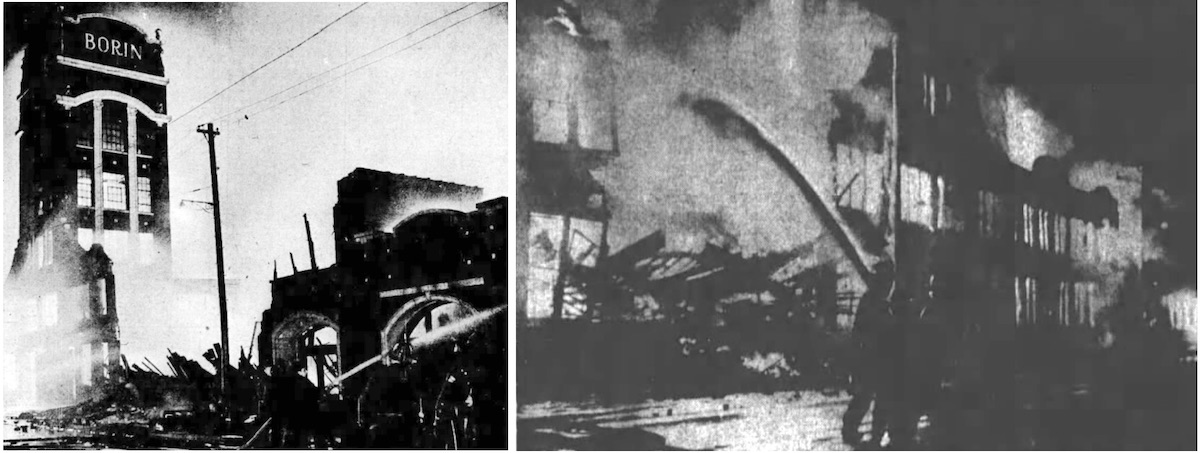

Everything seemed to come to a head in 1946. That spring, Lorne Locker—who’d been with the company for 20 years and taught accounting at Loyola University in his spare time—died at 63, leaving the business without its prime number cruncher. The ugliest months of the “Battling Borins” divorce proceedings were also underway. But the most devastating event of the year—at least for those who made their living working for Nate Borin—actually came back on January 2nd, when a fire destroyed most of the Cicero plant and two neighboring buildings at a cost of more than $1,000,000, as estimated by the factory superintendent at the time, Joseph Levinson. A striking image of the blaze with the Borin tower looming in the background was printed in papers across the country.

[Scenes of the massive fire that destroyed most of the Borin Art Products plant at 1325 S. Cicero Ave. in 1946]

“The worst fire I’ve ever worked was the Borin Art Co. blaze,” Cicero firefighter John Huiner recalled a few years later. “We worked on that job from 10 o’clock in the evening until 8 o’clock the next morning back in 1946. It was the most spectacular blaze I’ve ever seen. Our work was hampered by bursting containers of varnish and paints. One fireman contracted pneumonia from exposure.”

Claire Borin would later add the fire to her laundry list of accusations against her husband, noting in court filings that he was “guilty of many acts of fraudulent wrongdoing in handling the affairs of the [business], including misappropriation of funds and fraudulent bookkeeping,” and that “the effect of the fire was to force the discontinuance of the business” and to essentially cash in on the insurance.

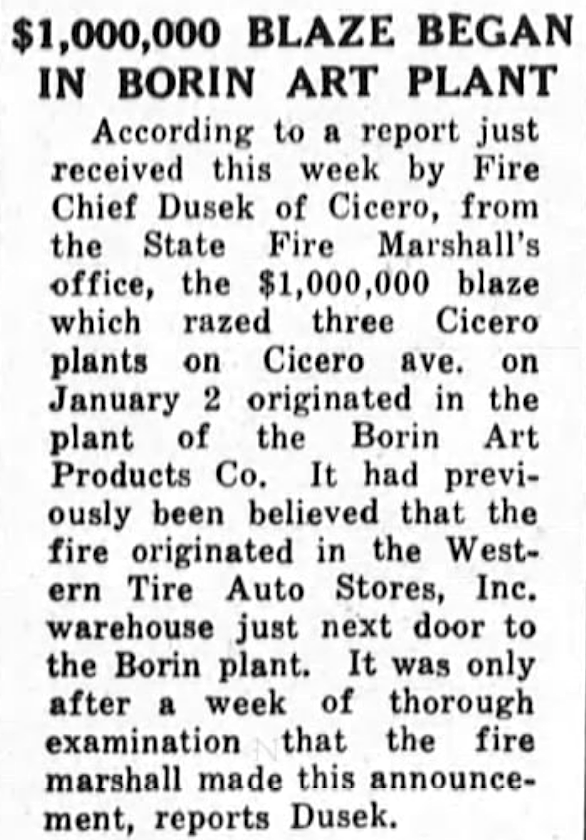

Nathan Borin obviously never copped to any such thing, but there is more than a little reason for suspicion. For one thing, there had been another unusual fire at the plant a few years earlier, during his financial struggles in 1942, which firefighters successfully put out. And while news reports initially indicated that the 1946 fire began inside the Western Tire Auto Store next door, the State Fire Marshal’s office did its own investigation and determined that it had, in fact, started in the Borin plant, as noted in the report included here from Cicero Life.

Nathan Borin obviously never copped to any such thing, but there is more than a little reason for suspicion. For one thing, there had been another unusual fire at the plant a few years earlier, during his financial struggles in 1942, which firefighters successfully put out. And while news reports initially indicated that the 1946 fire began inside the Western Tire Auto Store next door, the State Fire Marshal’s office did its own investigation and determined that it had, in fact, started in the Borin plant, as noted in the report included here from Cicero Life.

No charges, as best we can tell, were ever made in regards to the fire. Instead, out of those literal ruins, the Borin Art Products Co. surprisingly carried on, much like Nathan Borin’s love life.

The company rebuilt and reopened part of its original Cicero plant in 1948, before apparently moving its HQ the following year to 2500 W. 21st Place.

In 1954, Nathan Borin, by now aged 60, severed his ties with the business he’d created over 30 years prior. Robert Stern, a company vice president, was elected its new president and general manager, and the company was renamed the American Decorative Products Corp. Any trail of that business runs cold, however, after 1956.

Nathan Borin, likewise, saw his story end in 1956. He died that April and earned the cruel obituary headline we noted in the intro: “Nathan Borin, of Divorce Case Notoriety, Is Dead.” In fact, Nate had collected a third and final divorce shortly before his demise. Back in 1947, before the court saga with Claire Burman was even complete, Borin had shacked up with the newly crowned “Miss Miami Beach”—a 19 year-old model known as Pepper Donna (aka Janet Shore). She was an almost blatant stand-in for the younger version of Claire. The relationship played out similarly, too, albeit with a slightly shorter run to the finish line.

Nathan literally connected himself to Pepper by handcuffs at their Las Vegas wedding in 1949 “to make sure the tie was tight enough” this time around. When Pepper (known later in life as Donna Kaufman) died in 2005, her daughter Rhonda claimed that the famous gangster Bugsy Siegel had been Borin’s best man at the Vegas wedding. It certainly sounds plausible, and the Boston Globe believed the anecdote enough to print it. But alas, Bugsy was already two years in the grave by that point.

Nathan literally connected himself to Pepper by handcuffs at their Las Vegas wedding in 1949 “to make sure the tie was tight enough” this time around. When Pepper (known later in life as Donna Kaufman) died in 2005, her daughter Rhonda claimed that the famous gangster Bugsy Siegel had been Borin’s best man at the Vegas wedding. It certainly sounds plausible, and the Boston Globe believed the anecdote enough to print it. But alas, Bugsy was already two years in the grave by that point.

Long story short, the new couple set up a roost at Borin’s new Chicago apartment, 4300 Marine Drive, and had several weeks of peaceful matrimony, with Pepper even starting acting classes at the Goodman Theater. Soon it was clear, of course, that her husband wasn’t suited for his own role, and Pepper filed a divorce complaint in November of ’49, claiming Nathan struck her twice in their home. A second claim followed in 1951, and by 1953, the divorce was official.

Pepper Donna, like Claire Burman before her, went on to marry two more millionaires; “if at first you don’t succeed. . .” In 2005, her daughter Rhonda (from a later marriage) told the Boston Globe that the Chicago art dealer Nathan Borin had been ruthless to her mother, but that her “free spirit, big heart, and positive outlook” helped her survive and move on.

Pepper’s final statement to Nathan Borin back in 1953 was one that we can all appreciate, having just read about the guy. According to her daughter, on her way out of their Chicago home for the last time, Pepper stole a bag of 50-cent pieces that Borin had been collecting for years, and she used those coins to pay for a taxi that took her all the way to New York. “She also made the trip with her parakeet,” her daughter added.

[1927 advertisement for the The Fair, a Chicago department store, featuring a “marvelous selection of framed pictures purchased from the Borin Manufacturing Co.”]

Sources:

“Borin-Vivitone Corporation – 40,000 Shares” – Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, Feb 25, 1929

“Wife Sues Nathan Borin, Wants Her Bracelet Back” – Chicago Tribune, Feb 25, 1934

“The Art Dealer’s Prize Beauty Bride Slaps Him Out of His Own Picture” – El Paso Times, April 29, 1934

“Life Makes Survey of Cicero Factories; Most Are Optimistic” – Cicero Life, May 7, 1934

“Bitter Charges Disrupt Borins’ Alimony Hearing” – Chicago Tribune, April 2, 1935

“2,500 End Sit Strikes After a Record Week” – Chicago Tribune, March 14, 1937

“Fire Destroys 2 Big Plants; Loss a Million” – Chicago Tribune, Jan 3, 1946

“1,000,000 Blaze Began in Borin Art Plant” – Cicero Life, Jan 13, 1946

“Judge Sbarbaro Refuses to Hear Battling Borins” – Chicago Tribune, April 5, 1946

Lorne V. Locker obit – Chicago Tribune, April 18, 1946

“The Battling Borins” – New York Daily News, Dec 1, 1946

“What was the Worst Fire You Have Experienced?” – Berwyn Life, Dec 1, 1948

“The Battling Borins Finally Win Divorce; Mother to Keep Child” – Freeport Journal-Standard, March 1, 1949

“Removes Handcuffs from Bride” – Rock Island Argus, June 20, 1949

“Mrs. Borin on Honeymoon with Chicago Mate” – Madera Tribune, Nov 9, 1949

“Battling Borin Files Own Divorce Complaint” – Herald & Review (Decatur, IL), Nov 26, 1949

“And She Can Go Like Donald Duck” – The Miami News, Oct 22, 1950

“Shares in Estate: Mrs. Claire Morse” – Chicago Tribune, Oct 12, 1953

“. . . Election of Robert Stern” – Chicago Tribune, March 15, 1954

“Nathan Borin, of Divorce Case Notoriety, is Dead” – Chicago Tribune, April 4, 1956

Claire B. Morse, Appellant, v. United States of America, Appellee, 265 F.2d 788 (9th Cir. 1959)

“Donna Kaufman, 79; Model Saw Beauty in Life, Giving” – Boston Globe, Feb 10, 2005

“End of the Trail, Then and Now” – Met Museum, Feb 19, 2014

I have a framed print of Jesus Christ on the Mt of Olives, with the Borin Art Products stamp on the back, # 309. I’m interested in additional information on this piece.

Hello I have this painting had some questions can you please email me and I will send pics thanks..

Goes Lithographing Co. oF 42 W 61ST sT cHICAGO PRINTED bORIN aRT PICTURES FOR DECADES. Lone wolf, sacred hearts of JC & Mary. many goddess reclining scenes and sheep english scenes. Goes had its own line of art prints for sale as well that were sold to framers such as Ausable & Turner and Borin , Donald Art andinto Canada. Removed to Delavan WI 2010 established 1879 the company is run by 5th generation family members. many prints are available on ETSY for sale.

I have 2 pictures titled Sacred Heart of Jesus. Showing a picture of Jesus and Mary with a heart on their chest. 14×18 Has Illinois Art Industries Inc. 1325 S Cicero Ave Chicago printed on the back. Just wondering the date on these or if they are from your store(Borin). Thank you

I have 2 floral bouquet pictures

Number 9307 on back of picture

Gold frames with rope hangers

They belonged to my husbands grandparents

I would love more information on them

I have a framed light up picture of Jesus, the sticker on the back says “Borin presents Vita-Vision dramatic third dimensional pictures… exclusive Borin product, Borin Arts Products Corp, 2500 W 21st Place, Chicago 8 ILL.” There’s also style no, size, price on the sticker but all are blank. I can’t find anything like it online?

I own a painting of country snow and cabin house #1360?

I have a painting or print of a man with a camel in the desert. It says .. M.Borin as the signature. I wish to learn more about it.

I have a painting stamped 1928 Borin Manufacturing company Chicago “Holland Flower Market ” by M Parish. Does anyone know anything about this picture? Numbered #135

1915-1928

I also have this holland market print and would like to know more about it.

Mine is also from !928.

did you get a reply Cindy Wagner

I own a Borin mirror # 3402. I’d like to known more about it.

I have 5 Gold Vein mirrors. On the back it says Mirro-Tone-Decor. Borin Art Product-Chicago. All 5 mirrors have a print in the middle, mostly depicting horses. On the large octogonal mirror is a hand written # 1470.

Trying to find any info on these since I am preparing to sell them. Any idea of worth? I can send pictures.

Thank You

who was M.Rickets Borin.. I have the set of Victorian ladies framed. what year are they from? might you know the answer?

I own a Borin Decra-tone clock. (Originally purchased at Jordan Marsh Co., Boston, MA..) Can you please give me the value?

I have 2 oil painting on canvas. They are a pair, framed named and numbered. “Villa Del Amour” and “Potter of Damascus”. Bothe are No.56353

Have painting called “Last of Summer”

i have an oil painting of the southern belle and on the back it has in the small round circle 1325 s. ciicero ave. chicago borin art products and in the center it hasframed pictures and mirrors and i wondering does it have a background ????????? also anything else about it.?????

I recently bought a clock stamped k 161 I was wanting to know the history on it it says borin decra-tone k 161 .

Hi I bought a Borin Vivitone mirror stamped 3610 on back. I was wondering if you could point me in the direction so I could find out more on it. Thank you