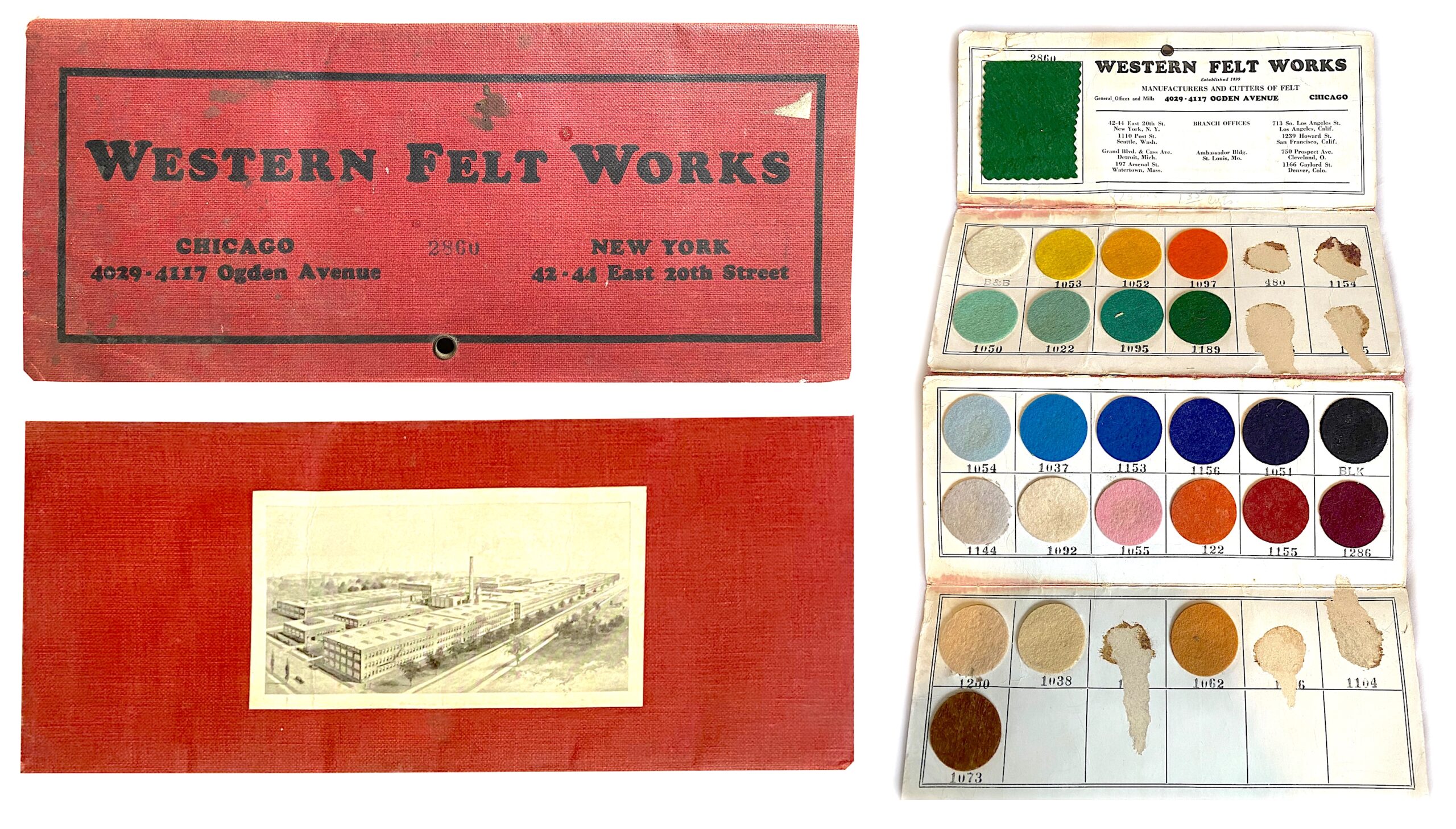

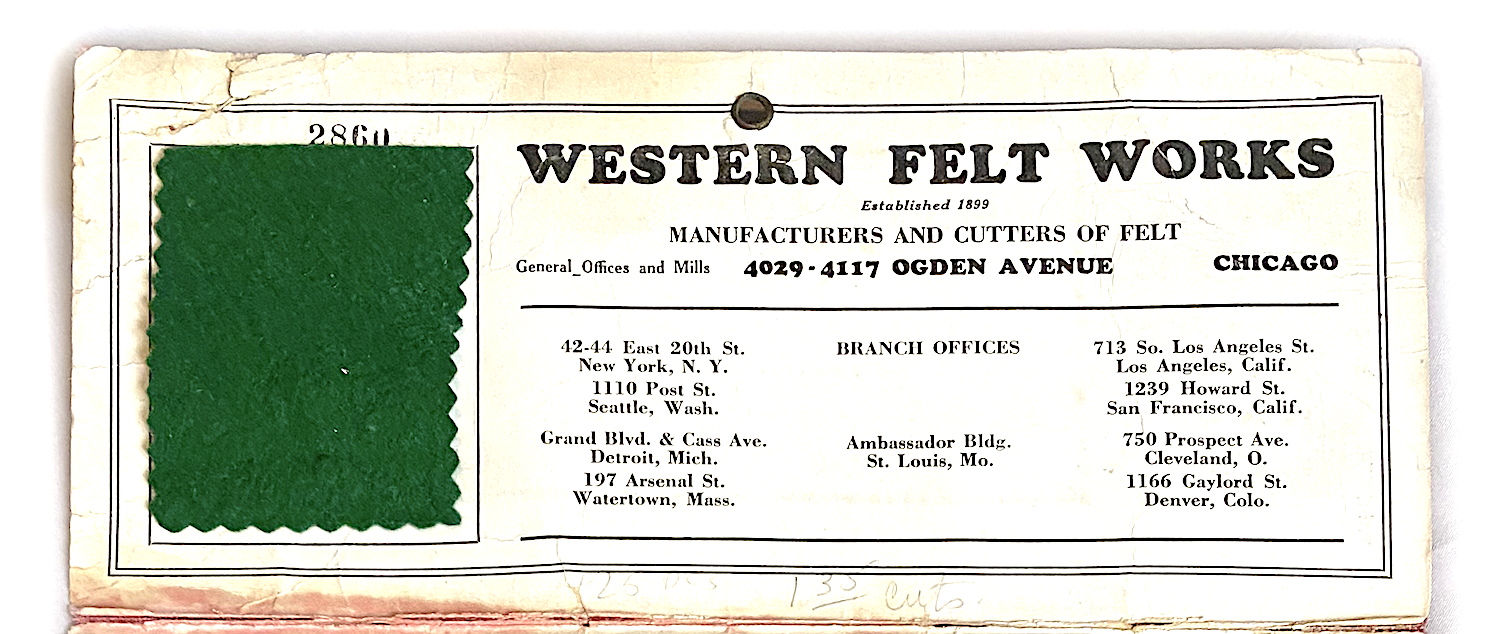

Museum Artifact: Salesman’s Pamphlet with Original Felt Samples, c. 1920s

Made By: Western Felt Works, 4029-4117 W. Ogden Ave., Chicago, IL [North Lawndale]

“Today is felt’s heyday. Its use is almost universal, and its appeal . . . well, its appeal is the appeal the individual is capable of creating. For every display use, there has never been a more versatile material.” —Display World magazine, 1931

If steel is the archetypal industrial product of the 20th century American metropolis, then its complementary cousin has to be felt—the soft textile counterbalance to the spewings of the blast furnace. Naturally, Chicago was churning out plenty of both materials, and in the latter category, no company supplied more well-pressed wool to America than the Western Felt Works.

If steel is the archetypal industrial product of the 20th century American metropolis, then its complementary cousin has to be felt—the soft textile counterbalance to the spewings of the blast furnace. Naturally, Chicago was churning out plenty of both materials, and in the latter category, no company supplied more well-pressed wool to America than the Western Felt Works.

When this firm completed a major expansion of its North Lawndale factory in 1921, an article in Fibre and Fabric magazine provided a “partial list” of the myriad of products coming out of the plant; giving us a snapshot of felt’s widespread prominence across just about every American industry: “Automobile washers, gaskets, lubricating wicks, and windshield strips; furniture draw linings and showcase linings; hat pads and cap linings; laundry felts; incubator felts; felt bolsters for tanneries; phonograph turntable felts and washers; piano felts in rolls or cut to size; radiator cover linings; robe linings; pennant and upholstery colored felts; saddlery felts and pads for horses; shoe and slipper felts, tongue linings, cut heel pads, and felt inner soles; sporting goods linings and paddings; stamp pad and toy felts; tailoring felts and pressing machine padding; and tractor and truck washers and gaskets.”

Thirty years later, Western Felt Works—with nearly 2,000 employees now on its payroll— was still working with an unusually diverse clientele. “The possibilities for putting Western Felt Works products to work are almost limitless,” read a 1952 advertisement. “Its versatility of qualities, shapes, sizes, and densities make it applicable in many new ways. . . . Manufactured from wool-softness to ‘rock’ hardness, Western Felt can be made to meet practically any specification. It is resilient, flexible, resistant to heat, age, alcohol, compressibility, oils, etc.”

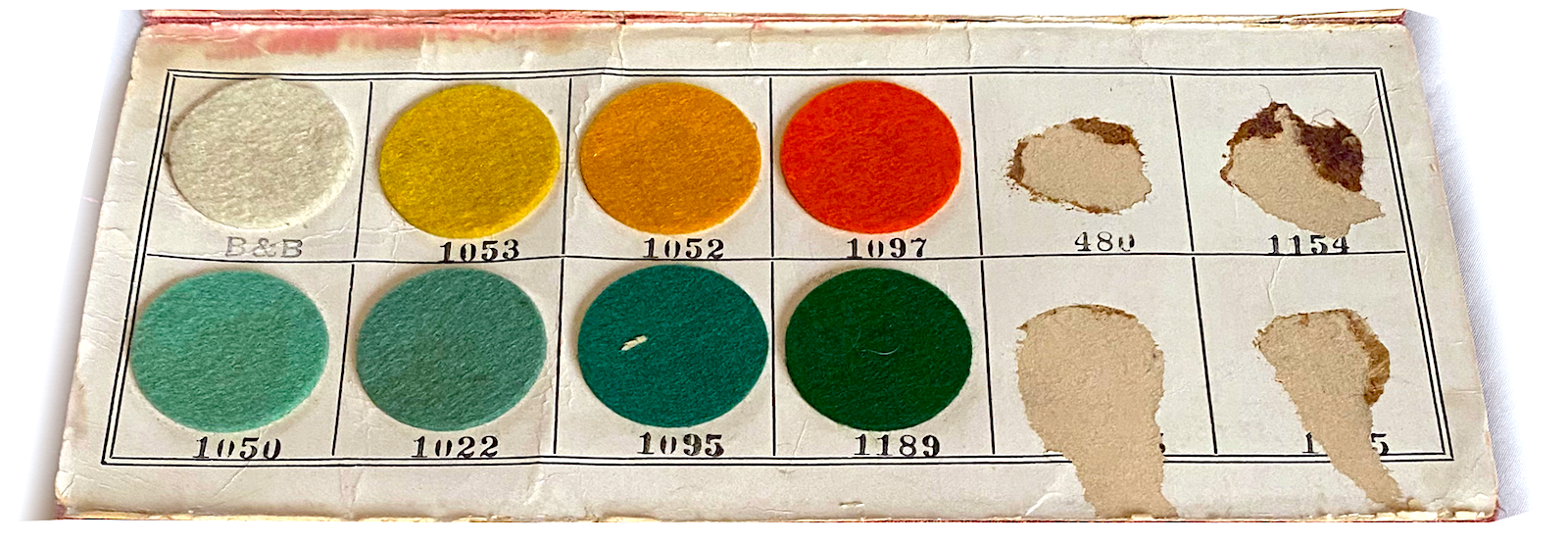

One person particularly well versed in the dynamism of Western Felt is William R. Faurot, who first came to work at the Ogden Avenue plant in 1954, when he was 22 years old.

“I worked at Western Felt from 1954 to 1964,” Mr. Faurot told the Made In Chicago Museum in 2022. “They paid for my MBA. One of the two founders was my grandfather Henry Faurot. The other founder was my grandfather’s brother-in-law George Silverthorne. Like many family businesses, they split along family lines. And, like many family businesses, the company was sold and later liquidated. I bought 100 shares at $35 per share and received $3.50 per share on liquidation. I believe that, at age 90, I am the sole surviving employee!”

History of the Western Felt Works, Part I: Faurot & Silverthorne

Western Felt Works might have risen and fallen like many family businesses before it, but this family was hardly on the hum-drum side when it came to intrigue and drama. Along with reaching the most exclusive penthouses of high society, there was also an inordinate amount of tragedy that befell the clan.

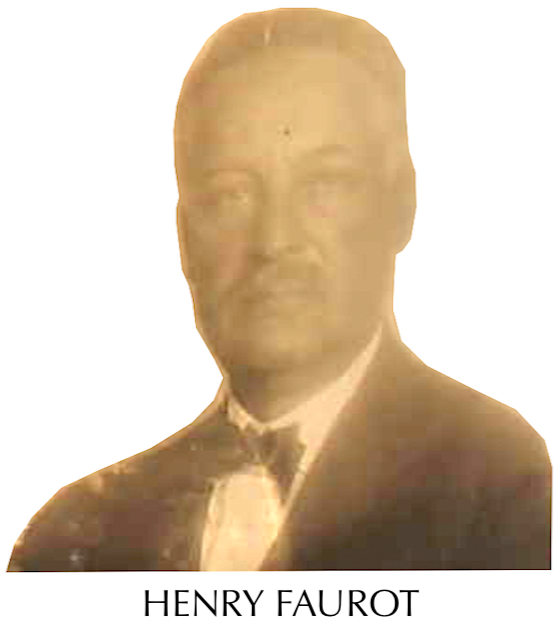

The aforementioned company founder Henry W. Faurot (b. 1864) was a native of Albany, New York, and worked as a grain elevator operator before coming to Chicago in his 20s to join one of the city’s stockyard giants, Armour & Company. He met and married his wife Catherine Silverthorne in 1891, and shortly thereafter, introduced his new brother-in-law William E. Silverthorne to his own future bride, Julia Belle Chapin. As no small detail, Julia was also the niece of Faurot’s boss, the nouveau riche tycoon Philip D. Armour himself. And thus, overnight, the Faurots and Silverthornes were now part of one of the most powerful families in America.

The aforementioned company founder Henry W. Faurot (b. 1864) was a native of Albany, New York, and worked as a grain elevator operator before coming to Chicago in his 20s to join one of the city’s stockyard giants, Armour & Company. He met and married his wife Catherine Silverthorne in 1891, and shortly thereafter, introduced his new brother-in-law William E. Silverthorne to his own future bride, Julia Belle Chapin. As no small detail, Julia was also the niece of Faurot’s boss, the nouveau riche tycoon Philip D. Armour himself. And thus, overnight, the Faurots and Silverthornes were now part of one of the most powerful families in America.

Thanks in part to these connections, Henry Faurot was soon put in charge of Armour’s “curled hair and felt” division in Chicago, which would prove to be both a blessing and a curse. In 1898, he helped oversee the construction of a new five-story factory for the Armour Felt Works, located at 31st Place and Benson Street. Less than a year after it opened, though, in March of 1899, this plant was completely decimated by a horrific fire that left eight workers dead and many more injured. Had this tragedy not occurred, Faurot may well have stayed on with Armour well into the 20th century. Instead, in the immediate aftermath of the fire, the 35 year-old opted for a new start on his own terms, which Philip Armour dutifully granted.

[Left: Philip Armour, boss of Armour & Co., and Henry Faurot’s boss for most of the 1890s. Right: New York Times headline following the deadly fire at the Armour Felt Works in Chicago on March 27, 1899.]

For assistance in his next venture, Henry kept things in the family. Along with financial help from William Silverthorne, he recruited another brother-in-law, George M. Silverthorne, to co-manage the new enterprise. Despite appearances, George didn’t earn this opportunity on nepotism alone.

While he was 13 years younger than Faurot, George Silverthorne was arguably the more “worldly” of the two. After graduating from the Michigan Military Academy in 1896, he had volunteered for service in the Spanish-American War, where he was promoted to the rank of captain at just 21 years of age. Silverthorne spent half a year in Cuba during the conflict, then returned to Chicago, where he studied law at Northwestern for the next year.

As the timing worked out, young George was looking to begin his professional career just as his sister’s husband was trying to start over again. And so, in the summer of 1899—within a few months of the Armour fire and George’s exit from law school—the first mill of the Western Felt Works was officially organized at 787-797 South Canal Street.

As the timing worked out, young George was looking to begin his professional career just as his sister’s husband was trying to start over again. And so, in the summer of 1899—within a few months of the Armour fire and George’s exit from law school—the first mill of the Western Felt Works was officially organized at 787-797 South Canal Street.

“Mr. Henry Faurot, late manager of the Armour Felt Works, destroyed by fire a short time ago, has himself started a large felt manufactory under the name of the Western Felt Works,” the American Wool and Cotton Reporter noted at the time. “The machinery and equipment is of the best modern pattern. They will make a specialty of felts used in the clothing industry. The chiefs and a great number of the skilled employees of the late Armour factory are secured for the new firm.”

The transition went smoothly, and by 1904, Fibre and Fabric magazine was reporting that “the Western Felt Works are very busy; orders enough are looked to keep the plant running for a year. They make all kinds of goods, from saddle felts up to the finest trimming felts. The superintendent, Mr. George Silverthorne, is an up-to-date felt manufacturer in every way, and under his management every department runs like clock work. The overseers are as follows: William Peace, carder; Dan Haggerly, finisher and fuller; Ernest Patterson, dyer; William Haggerly, second dyer; John Beart, picker; Otto Schultz, bookkeeper and paymaster.”

[The “Ramshead” trademark was widely used on Western Felt products during its early years, as show in the Ramshead Rug advertisement above from 1901, as well as the 1913 ad for Ramshead Brand Pads for Horses]

There were 85 workers employed at the plant in 1905, and this more than doubled to 175 by 1910, as a new demand for automobile felts rapidly increased production. During this period, Western Felt relocated to what would become its long term home at 4115 W. Ogden Avenue in North Lawndale; a factory that would be routinely expanded in the years ahead.

“The outlook is good for new American business in my opinion,” Henry Faurot told the Tribune in 1914—a year in which Western Felt was taking on huge military orders to supply the Allied Forces with felt for artillery harnesses, saddles, and canteen covers. “While we are now running part of the factory nights to keep up with foreign army orders, which will keep us busy for several months, and are employing about 30 percent more help than normally . . . I feel we are entering into a period of prosperous and busy times.”

[1919 advertisement showing Western Felt’s growing factory complex at 4115-4133 Ogden Avenue]

II: Soft Felt, Hard Feelings

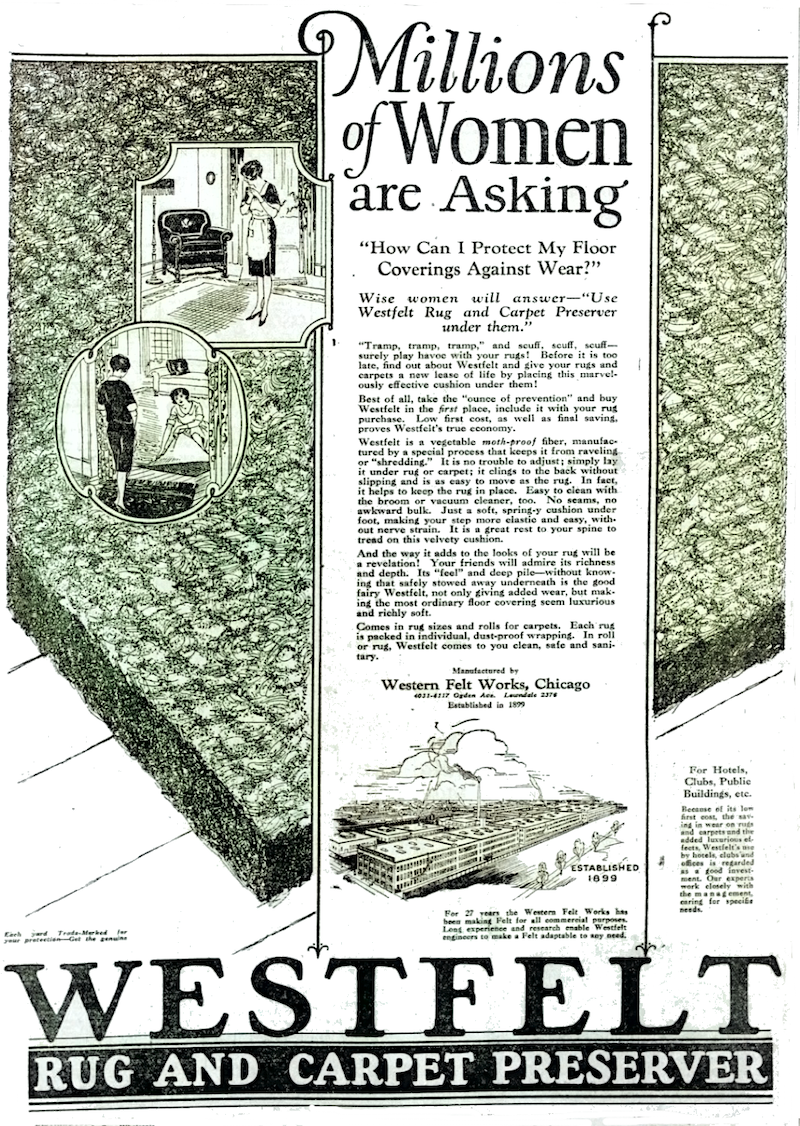

In the early 1920s—around the same time the salesman’s sampler in our museum collection would have been in circulation—Western Felt completed work on its biggest factory expansion to date. With more than 400 workers now in its employ, the company confidently described itself as the “largest independent felt mill in the United States.”

“In this plant,” read a 1923 advertisement, “under centralized control, we carry on every process from grading raw wool to packing our daily carloads of cut shapes. You are sure of uniformity, promptness, and high quality by using Western Felt.”

“In this plant,” read a 1923 advertisement, “under centralized control, we carry on every process from grading raw wool to packing our daily carloads of cut shapes. You are sure of uniformity, promptness, and high quality by using Western Felt.”

Another ad from the same year notes that the Chicago factory was “days nearer the principal automotive centers than any other factory. Its size bespeaks our immense capacity. . . . Many of the largest automotive accounts—as well as smaller ones—depend entirely on Western Felt for their requirements.”

In 1926, to add to the company’s association with the automotive revolution, the very road directly outside its factory doors was incorporated into a new superhighway known as Route 66, meaning thousands of cross-country motorists would now be passing by the impressive headquarters of the nation’s top felt manufacturer.

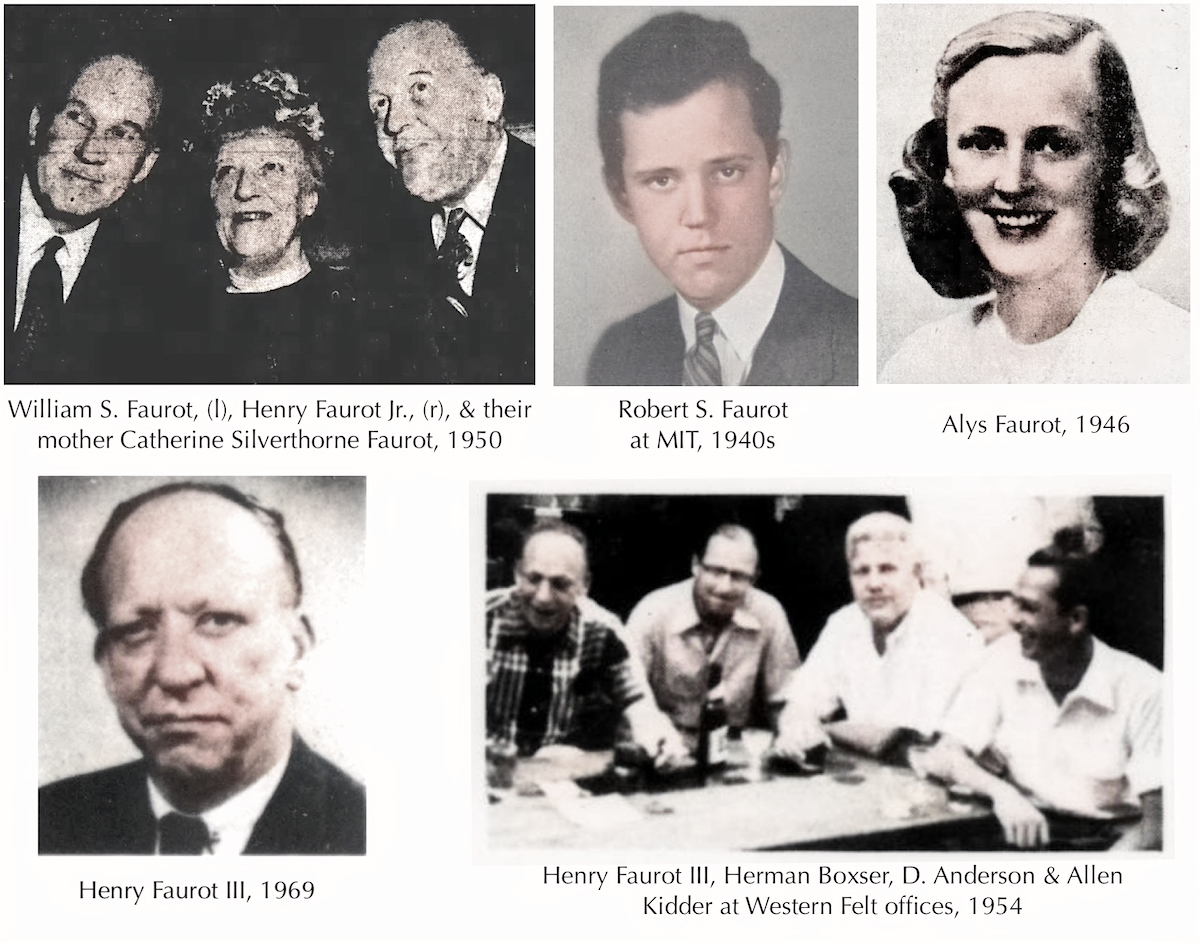

By this point, a new generation of Faurots and Silverthornes had joined the Western Felt team, including sibling executives Henry Faurot, Jr. (b. 1892), William S. Faurot (b. 1899) and George S. Faurot (b. 1901), as well as young salesmen George Silverthorne, Jr. (b. 1905) and his kid brother John H. Silverthorne (b. 1906). While they were all beneficiaries of their fathers’ sustained success, the wider reputation of their famous family would soon be tarnished by a string of tragedies, controversies, and tabloid embroilments.

[Bottom Left: The Western Felt complex as illustrated in 1927. Top Left and Bottom Right: One of the original buildings still standing today, at 4115 W. Ogden Ave. Top Right: A Packard car dealership just down the road from Western Felt on Rte 66 at 4038 W. Ogden, as seen in 1933]

Most publicized of all was the biopic-worthy saga of Alice de Janzé (b. 1899)—the daughter of William Silverthorne and Julia Belle Chapin, and niece to both George Silverthorne, Sr. and Henry Faurot, Sr.

Alice was born the same year as Western Felt’s founding, and was by most accounts a modern, free-spirited, and artistic person. Sadly, though, her parents’ wealth couldn’t secure her a healthy upbringing. After her mother’s death in 1907, her alcoholic father William Silverthorne proved to be a dangerous influence, sending Alice into a chaotic spiral as a teenage socialite, bouncing from Chicago to New York to the French Riviera, where she developed a life-long drug habit and struggles with depression. At 22, Alice married a wealthy French aristocrat and race car driver, Frédéric de Janzé, making her a “countess” in the process. Spurning a traditional Western lifestyle, the young couple soon joined the notorious “Happy Valley” enclave of Jazz Age proto-hippies in Kenya (then a British colony), where rumors of rampant drug use and sexual promiscuity made them lightning rods for controversy.

Alice was born the same year as Western Felt’s founding, and was by most accounts a modern, free-spirited, and artistic person. Sadly, though, her parents’ wealth couldn’t secure her a healthy upbringing. After her mother’s death in 1907, her alcoholic father William Silverthorne proved to be a dangerous influence, sending Alice into a chaotic spiral as a teenage socialite, bouncing from Chicago to New York to the French Riviera, where she developed a life-long drug habit and struggles with depression. At 22, Alice married a wealthy French aristocrat and race car driver, Frédéric de Janzé, making her a “countess” in the process. Spurning a traditional Western lifestyle, the young couple soon joined the notorious “Happy Valley” enclave of Jazz Age proto-hippies in Kenya (then a British colony), where rumors of rampant drug use and sexual promiscuity made them lightning rods for controversy.

Alice had already earned the nickname “the wicked Madonna” before 1927, when she made international headlines for an incident that may have inspired 100 film-noir scripts. In broad daylight at the Gare du Nord train station in Paris, she took out a revolver and shot Raymond Vincent de Trafford—a British aristocrat with whom she’d been having an affair—then turned the gun on herself. Both Alice and de Trafford survived their wounds, and in the media storm that followed, the countess explained the “sudden impulse” that had motivated her actions. “I said to myself, I must take him with me forever,” she told a magistrate. “As he slipped his arm round my waist I drew my revolver from my pocket. I put it between us . . . at this moment I heard the whistle of the engine and the thing happened.”

Adding to the sensational story was the fact that de Trafford refused to press charges against de Janzé, and instead defended her actions. Incredibly, within a few months, the shooter and the victim even renewed their romance, eventually marrying (albeit briefly) in 1932.

Sadly, the Silverthornes’ low points didn’t stop with Alice. In 1932, George Silverthorne, Jr. lost his 11-month old son Thornton after the baby was accidentally smothered in his cot. The following year, 26 year-old John H. Silverthorne—an up-and-comer at the Western Felt Works—committed suicide in his home; shooting himself just moments after saying goodnight to his wife and 2 year-old daughter in the next room. Suicide would ultimately spell the end for Alice de Janzé, as well, as she was found with another self-inflicted gunshot wound in 1941 (an incident depicted, with little empathy, in the 1987 film White Mischief). There were difficult losses on the Faurot side of the family, too, including the death of Henry Jr.’s wife Dorothea in 1935 at the age of 45, leaving behind her three kids Henry III, Robert, and Alys.

[Left: 1927 headline in British newspaper the Leicester Mail covering the “Gare Du Nord Affair,” in which Alice de Janze shot her lover and herself at the Paris train station. Center: Alice de Janze in 1927. Right: Chicago Tribune report from 1933 on the suicide of Western Felt executive John H. Silverthorne, who was only 26. Pictured far right is John’s widow, Elizabeth Silverthorne.]

As if the dark clouds of these tragedies and the economic losses of the Great Depression weren’t enough, the Western Felt Works also faced the greatest turmoil within its own ranks in the 1930s. The longtime partnership between the Faurots and Silverthornes was over by the decade’s end, as George Silverthorne, Sr. retired and George Jr. left to join the Columbia Feather Company. Henry Faurot, Sr. remained in the presidency, but Henry Jr. now handled most of the company’s daily business as its vice president. This included the responsibility of tackling growing unrest among Western Felt’s workforce.

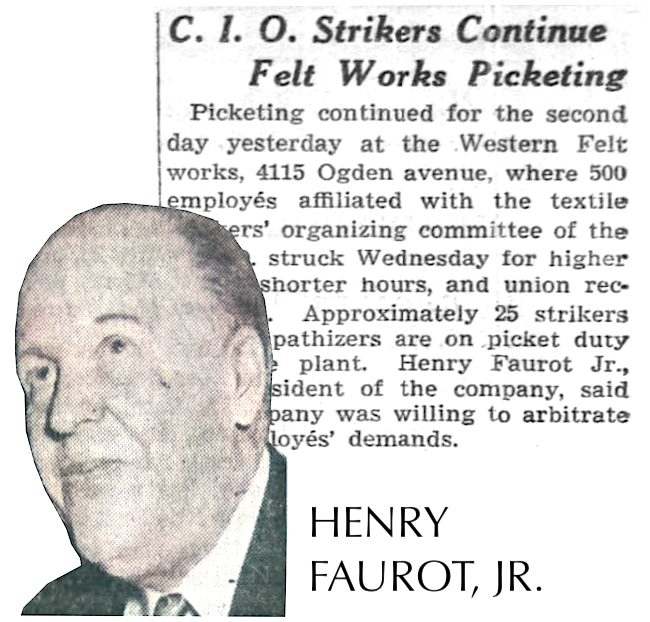

“Picketing continued for the second day yesterday at the Western Felt Works, 4115 Ogden Avenue,” the Tribune reported in June of 1937, “where 500 employees affiliated with the textile workers’ organizing committee of the C.I.O. struck Wednesday for higher wages, shorter hours, and union recognition.”

“Picketing continued for the second day yesterday at the Western Felt Works, 4115 Ogden Avenue,” the Tribune reported in June of 1937, “where 500 employees affiliated with the textile workers’ organizing committee of the C.I.O. struck Wednesday for higher wages, shorter hours, and union recognition.”

Faurot, Jr. said at the time that he was willing to arbitrate the workers’ demands. A year later, though, Western Felt Works was found guilty of unfair labor practices by the National Labor Relations Board, which determined that Faurot, Jr. had discharged many of the striking employees rather than negotiate with them. After the ruling, Western Felt was ordered to reinstate 80 workers, with backpay, and to recognize the Textile Workers’ Organizing Committee.

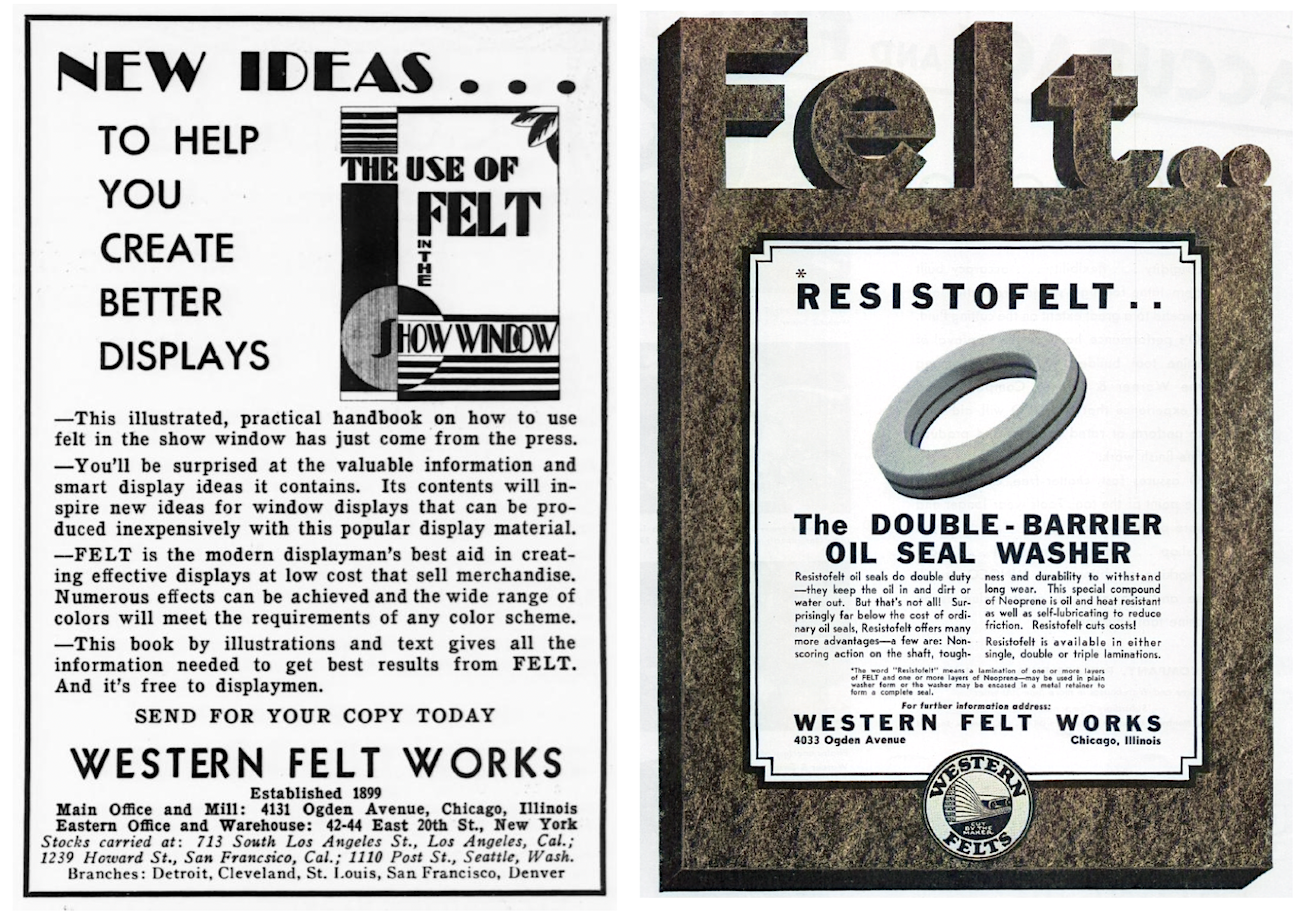

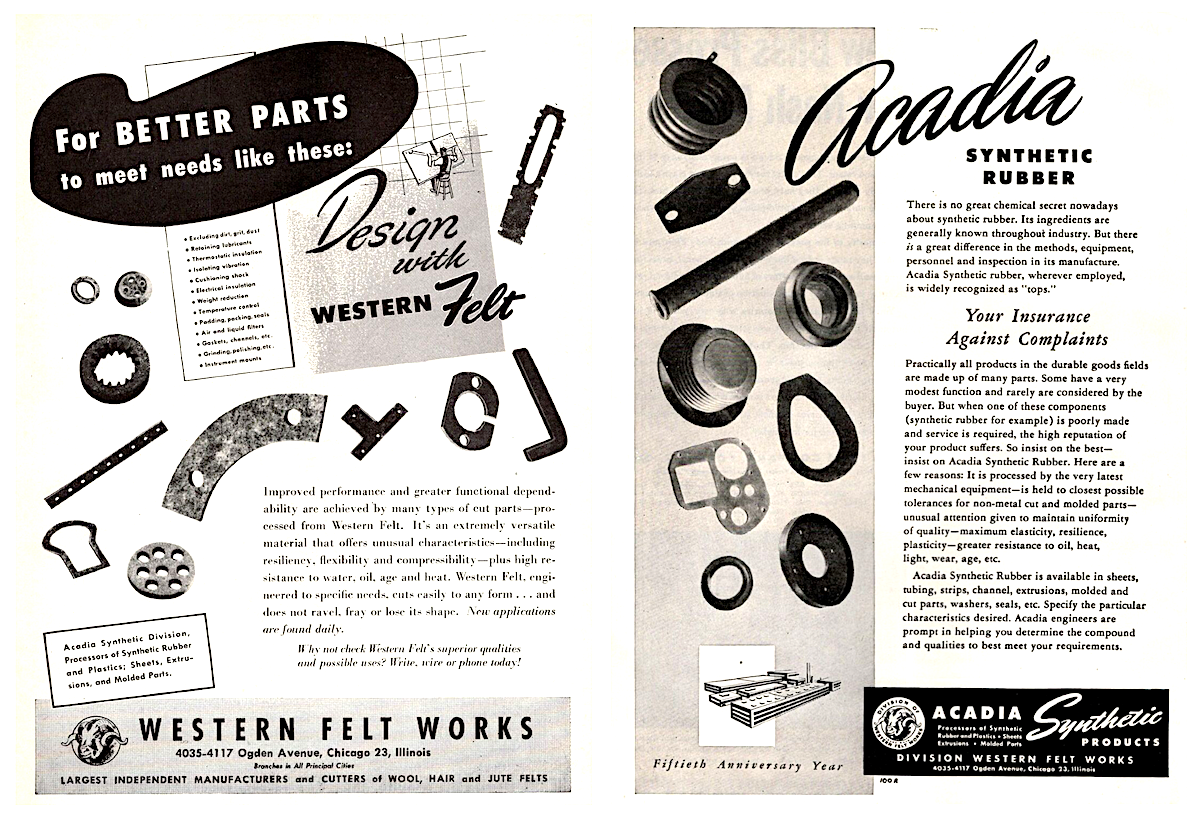

Somehow, despite the infighting, economic obstacles, and emotional devastation, Western Felt still entered the 1940s as an industry leader. The company’s product lines—such as Acadia, Westfelt, and Resistofelt—were widely known, and it now operated branch offices in more than a dozen cities from Newtonville, Mass. to Seattle, Wash.

[Western Felt advertisements from 1933 (left) and 1937]

III. Seals and Synthetics

“There is no great secret nowadays about synthetic rubber. Its ingredients are generally known throughout industry. But there IS a great difference in the methods, equipment, personnel and inspection in its manufacture. Acadia Synthetic rubber, wherever employed, is widely recognized as ‘tops.’” —Western Felt advertisement for its Acadia Synthetic Products division, 1949

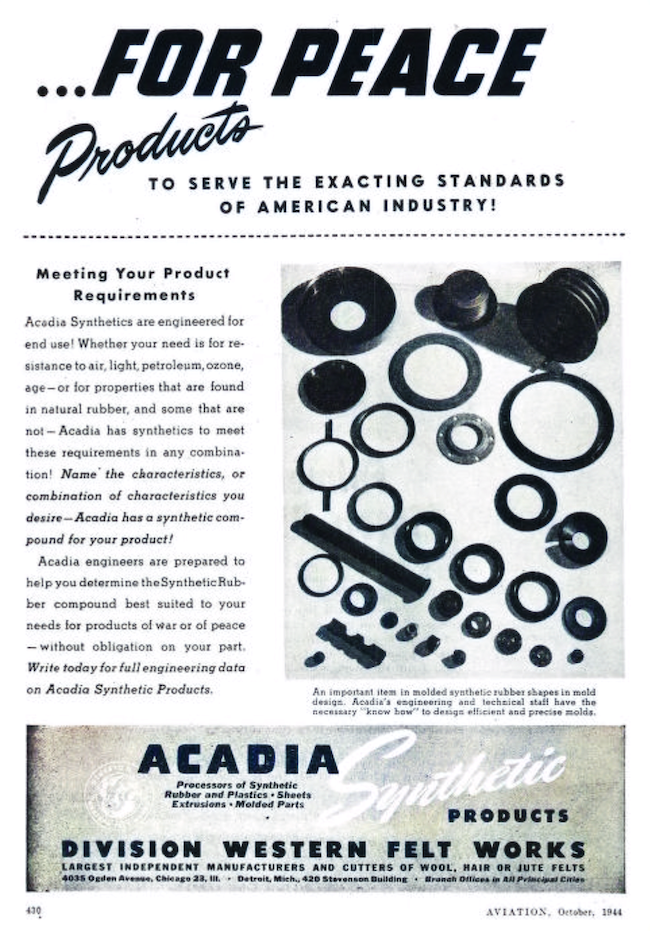

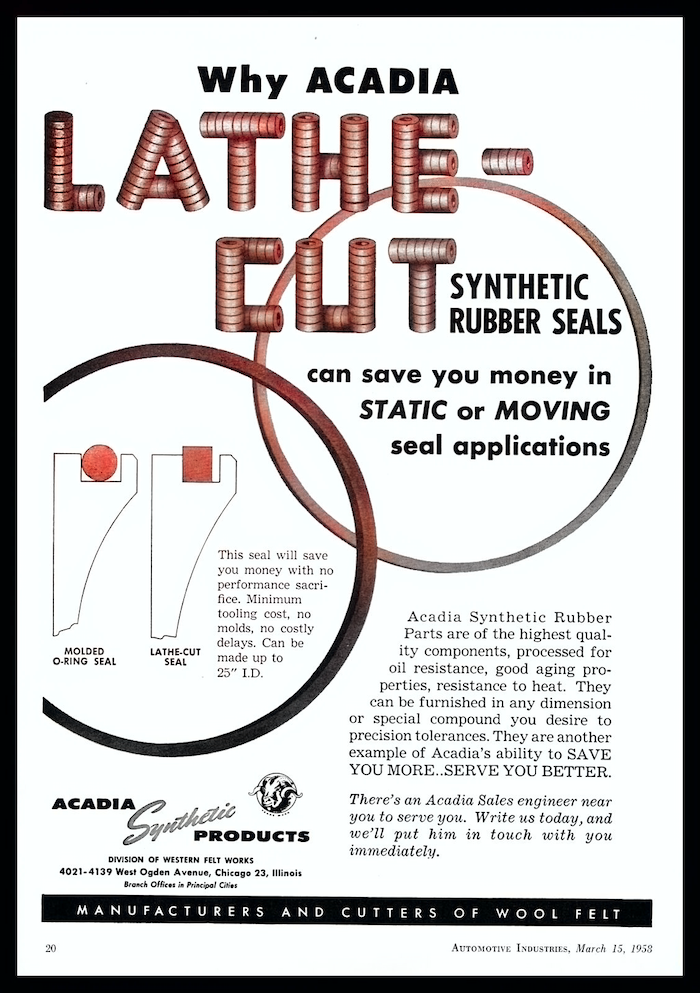

Partly in response to a nationwide rubber shortage during World War II, Western Felt began a gradual pivot into newer technology, specifically synthetic rubbers and plastics. The “Acadia Synthetic Division” was established within the Chicago plant to focus on these lines, and year by year, it took over an increasing chunk of the company’s concern.

Partly in response to a nationwide rubber shortage during World War II, Western Felt began a gradual pivot into newer technology, specifically synthetic rubbers and plastics. The “Acadia Synthetic Division” was established within the Chicago plant to focus on these lines, and year by year, it took over an increasing chunk of the company’s concern.

After Henry Faurot Sr.’s death in 1948, the transition into a new era really began. A third generation of Faurots stepped into leadership roles, including Henry III (b. 1919)—a Purple Heart recipient during the war—and his younger brother Robert S. Faurot (b. 1922), who earned a degree in Chemical Engineering from M.I.T. in 1944, indicating his interest in guiding Western Felt beyond its namesake material. As noted in our introduction, another member of that new generation was William R. Faurot—the son of William Silverthorne Faurot and perhaps, by his own estimation, the oldest living ex-employee of the Western Felt Works as of 2022.

The women in the Faurot family weren’t directly involved in the running of the business, but again, they proved to be individuals of considerable noteworthiness. This included Henry Faurot Jr.’s second wife, Margaret Pirie—one of the heirs to the famed Chicago department store fortune—as well as Henry III and Robert’s younger sister Alys Faurot Cort, who had the adventurous spirit of her cousin Alice de Janze, without any of the darker impulses.

Along with being an artist and a socialite, Alys Faurot Cort was a volunteer nurse’s aid during World War II, and founded and managed an orphanage in the Mexican town of San Miguel de Allende from the 1960s into the 1980s. “She was certainly born into [a world of wealth],” Cort’s daughter said after her death in 2000, “but she was also its biggest rebel. Her dynamic spirit couldn’t be weighed down. . . . She always had this notion that she could make the world better. And people were drawn to her charm. She could, and did, make friends with everyone she met.”

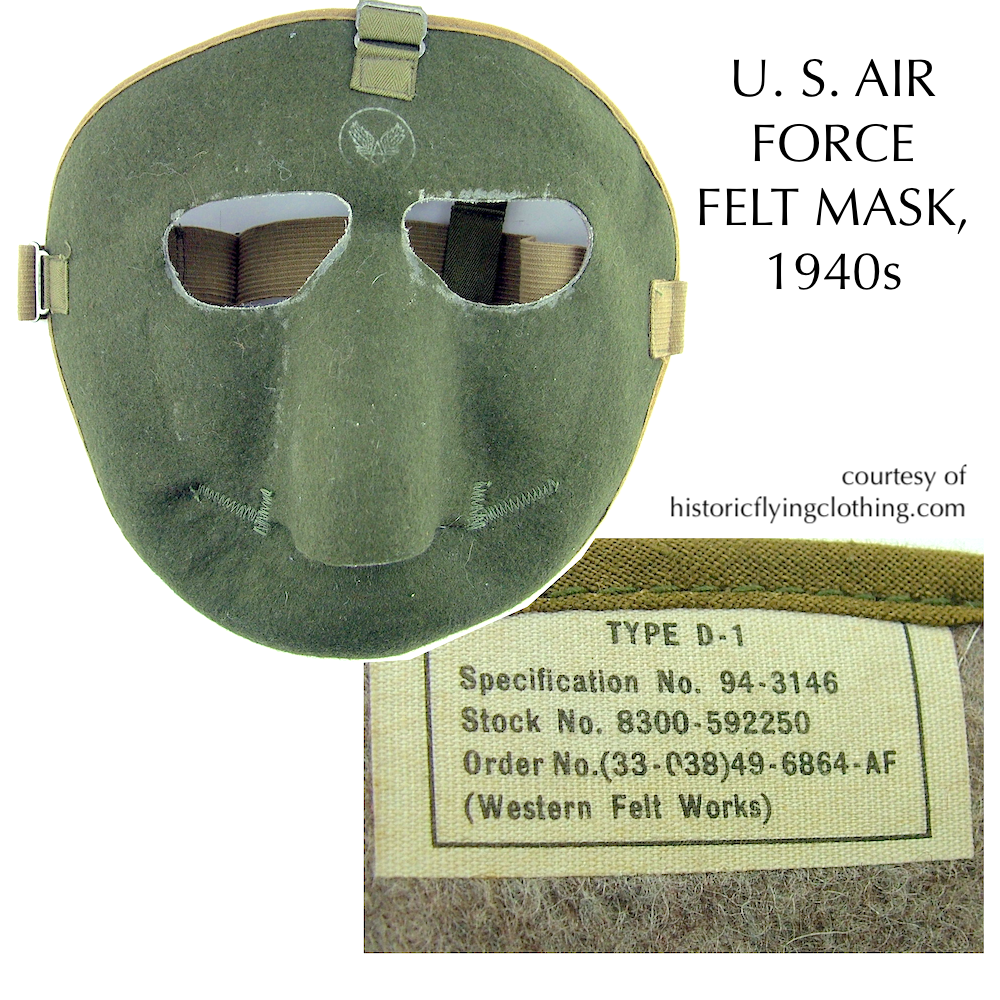

During and after World War II, the actual felt part of the Western Felt business continued to evolve, even as the exciting space age science of the Acadia Division stole more of the resources. As it had been during the First World War, felt was in high demand by the Allied Forces, used for objects like the Air Force face mask pictured here. The material was also advertised as a potential replacement option for rubber in making grommets, gaskets, and weatherstrips. Through the ‘50s and ‘60s, marketing efforts still pushed premium Western Felt to everyday consumers in the less greasy fields of fashion and window displays.

During and after World War II, the actual felt part of the Western Felt business continued to evolve, even as the exciting space age science of the Acadia Division stole more of the resources. As it had been during the First World War, felt was in high demand by the Allied Forces, used for objects like the Air Force face mask pictured here. The material was also advertised as a potential replacement option for rubber in making grommets, gaskets, and weatherstrips. Through the ‘50s and ‘60s, marketing efforts still pushed premium Western Felt to everyday consumers in the less greasy fields of fashion and window displays.

“Sew easy! Then go swingin’, singin’, havin’ your fling-in Fiesta Felt,” read a 1955 ad for one of the company’s clothing felts, which was available to buy in rolls at department stores. “Beautiful, many-hued Fiesta Felt adds authentic smartness to any wardrobe you can name. It’s college-bred, resort-conscious, goes to market, office or gay evening events with shapely distinction. New—so it wins approving glances; widely accepted—so it keeps you feeling comfortably ‘right.’”

What could be more important than feeling “comfortably right” during the height of McCarthyism in America?

[Left: 1955 ad for Western Felt’s “Fiesta Felt” line. Right: 1961 ad for the company’s Treated Felts]

In any case, by the 1960s, the real engine of the business had inevitably moved into synthetic fibers, including a specialty in precision seal manufacturing for the automobile and appliance industries. Relationships were forged with heavyweights like Dow Chemical and DuPont. If not for another string of difficult family losses at the end of that decade, things might have played out differently from that point forward.

Between 1968 and 1972, the three brothers who had led Western Felt for much of the century—Henry Faurot Jr. (aged 76), William S. Faurot (73), and George Faurot (66)—all died in the early years of their retirements. More sudden and unexpected was the loss, in 1968, of 46 year-old Robert S. Faurot. The aforementioned M.I.T. grad was actively serving as Western Felt’s president when he was killed in a car crash near his home.

Between 1968 and 1972, the three brothers who had led Western Felt for much of the century—Henry Faurot Jr. (aged 76), William S. Faurot (73), and George Faurot (66)—all died in the early years of their retirements. More sudden and unexpected was the loss, in 1968, of 46 year-old Robert S. Faurot. The aforementioned M.I.T. grad was actively serving as Western Felt’s president when he was killed in a car crash near his home.

After losing a father, two uncles, and a brother (and arguably his most valued advisors) in that short span of time—company chairman Henry Faurot III decided to enter the 1970s with a fresh start, just as his grandfather once had after the Armour factory fire seven decades earlier.

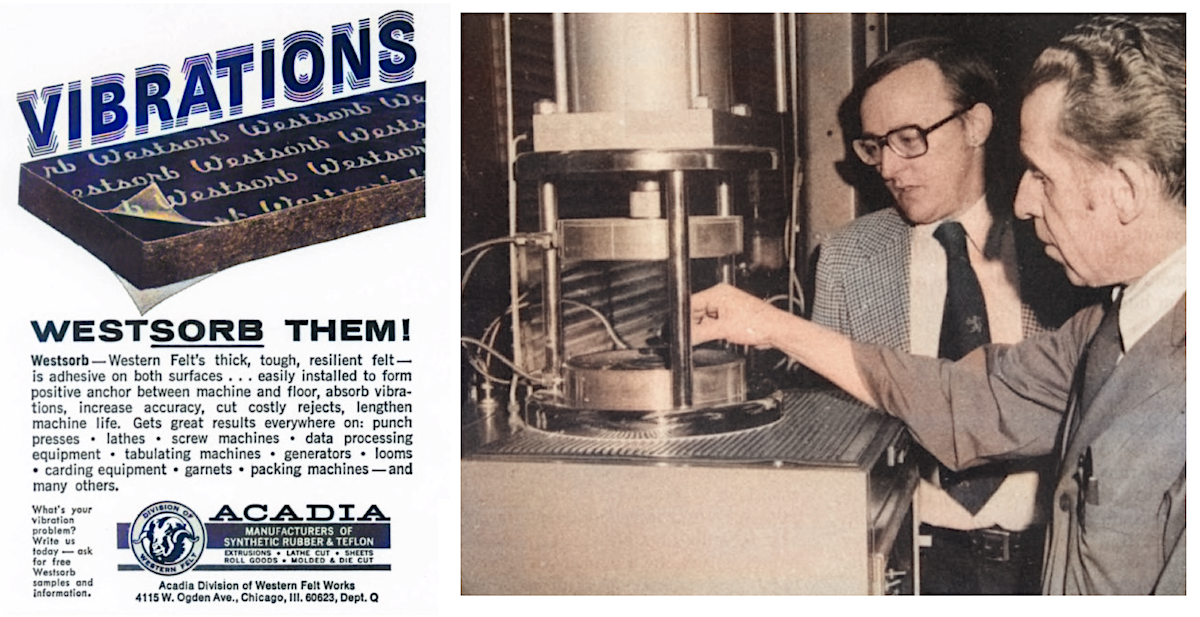

The name of the Western Felt Works was officially retired in favor of Western Acadia, Inc. And with the old Ogden Avenue factory complex on the decline, more money was put into other facilities, including a new synthetic fiber plant in Bartlett, Illinois, where the company would produce more of its new trademark products, including “Westex” and “Westsorb.”

[Left: 1967 ad for Western Felt’s “Westsorb” line. Right: Quality control manager Henry Hain (left) and chief chemist Leonard Fron test material on a rheometer at the Western Acadia lab, 1978]

The company’s total employee count—which had peaked at close to 2,000 after the war—was sitting around 600, with the majority still working at the Ogden Avenue location. Sales numbers were decent, but with Henry Faurot III now approaching retirement age himself, acquisition offers that might once have been ignored started receiving consideration. It was the familiar story for specialist manufacturers in the 1970s.

Finally, in 1978, Western Acadia was purchased by Lydall, Inc. of Manchester, Connecticut. The new owners kept the Chicago factory in operation for another several years, but those jobs were gradually lost, and the once great plant—the headquarters of felt production in America—suffered the same fate as the famed road, Rte. 66, along which it resided.

Sources:

“Honors for Chicago Man” [George M. Silverthorne] – The Inter Ocean, Dec 11, 1898

“Fire Imperils Hundreds: Destruction of the Armour Felt Works” – New York Times, March 28, 1899

“Mr. Henry Faurot . . . ” – American Wool and Cotton Reporter, Sept 28, 1899

“The Western Felt Works are very busy . . . ” – Fabric & Fibre, Vol. 40, 1904

“Heavy Demand for Felt Goods” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 26, 1914

“New Plant of Western Felt Works” – Fibre & Fabric, Jan 15, 1921

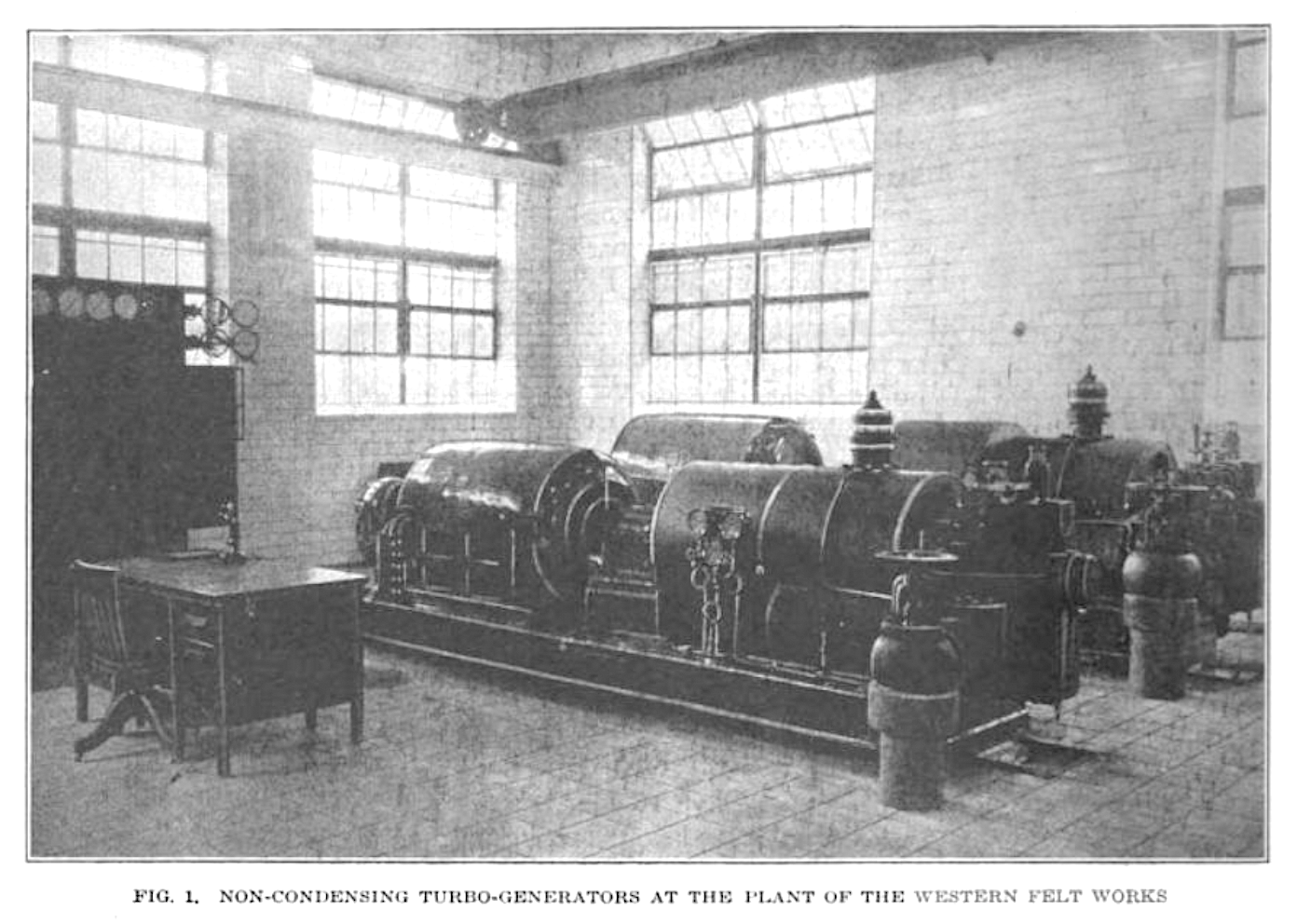

“Non-Condensing Turbine Plant of the Western Felt Works” – Power, Vol. 53, No. 8, 1921

“Comtesse’s Secret in Shooting Drama” – Leicester Mail (UK), March 28, 1927

“Western Felt Works” – Automotive News, May 26, 1927

“Felt for Modern Displays and Its History” – Display World, December 1931

“Thornton Dixon Silverthorne [obit]” – Rock Island Argus, Jan 18, 1932

“Young Society Husband Kills Self in Home” – Chicago Tribune, Jan 24, 1933

“CIO Strikers Continue Felt Works Picketing” – Chicago Tribune, June 11, 1937

“Felt Company Is Found Guilty by Labor Board” – Chicago Tribune, March 16, 1938

“S.A.E. Standard Felt Specifications” – Western Felt Works pamphlet, 1941

“Henry Faurot [obit]” – The Rubber Age, Vol. 63, Iss 3, 1948

“Acadia Synthetic Products Div.” – American Dyestuff Reporter, Aug 16, 1954

“George Silverthorne Faurot [obit]” – Chicago Tribune, Jan 18, 1968

“Antioch Man Involved in Fatal Crash [Robert S. Faurot]” – Antioch News, Oct 24, 1968

“Henry Faurot Funeral Rites are Set Today” – Chicago Tribune, Oct 28, 1969

“Synthetic Fiber Plant Opened in Bartlett” – Chicago Tribune, Oct 29, 1970

“Lydall Firm Agrees on Purchase” – Hartford Courant, Jan 20, 1978

“Precision Seals Demand High Performance Elastomers” – Elastomerics, March 1978

“Alys Faurot Cort, Artist, Philanthropist” – Chicago Tribune, June 3, 2000

With the demolition crews mobilizing and starting to salvage timber and bricks, unfortunately most of the plant succumbed to fire Friday night, October 11, 2024. However, the original Prairie School structure along Ogden is still intact (for the next few weeks, that is.)

https://hoodline.com/2024/10/historic-felt-factory-engulfed-in-flames-chicago-s-lawndale-neighborhood-witnesses-major-fire-at-endangered-western-felt-works-building/

Western Felt Works and surrounding buildings are facing demolition in 2023. Permits have been issued. The building is on the Endangered List of Preservation Chicago. The development is not supported by the neighborhood for several reasons. Here is one link of many:

https://www.chicagomag.com/news/when-a-proposed-development-threatens-disinvestment/ My father worked there for many years, and the building and business were of such importance to our nation’s history and Chicago.I hope that others can reach out to persuade the property owners to revise their plans. Here is a second link:https://chicago.suntimes.com/environment/2024/05/15/north-lawndale-fight-demolition-plan-truck-traffic-chicago

My father Tom Lacy was a “sales engineer” for Western Felt and then Western Acadia. This history gave me some good clues on his work life. He went to MIT and might have been hired by Robert Faurot. The name is familiar. Dad worked in the Newtonville, MA office in the 1950’s near where he grew up and moved to NYC in 1961 where he sold and ran a Western Felt warehouse. He later moved the warehouse to Fairfield (?) NJ. I worked there occasionally in the summers. He travelled quite a bit around the northeast doing sales and had a several person crew shipping out of the warehouse. They were a close knit crew. He lost the job about 1978 and this history gives the likely explanation – that is when the company was sold.

My dad Joseph Rasimas worked as a

Machine operator for 40 years at

Western Felt.He was employed through

The 40’s and 50’s and had to come from

The north side near Wrigley Field.

He didn’t want to supervise but preferred

To be one of the guys.

Wayne Rasimas/his som

A colorful, but very competitive, and and combative family, causing much bitterness and grudges that lasted for generations.

The Silverthorne and Faurot families did not speak to each other for many years, and it caused quite a flap when when the grandaughter of George Silverthorne (me) married the. Grandson of Henry Faurot.

(Frank Reed)

Jaquelin Silverthorne Reed

My father worked at Western Felt Works. I have a bag pins that were service year pins. They are quite beautiful and amazingin design. I will add more about those after I check that box. Would love to know my parents exact date of hire or connect with anyone who would have been there in the 1950’s and the 1960’s. I even worked part of a summer there so have those memories of being on the floor to share. On eBay I managed to acquire a felt card sample and will donate it eventually.

My dad Richard Ferguson died March 12 2022 at 90 years old in his personal belongings were a pin with western felt works at the top of it and below that is a head of a ram sheep and below that is the number 10.I would like to know more Thank You

Service pin for 10 years I think. They were beautiful. My father has one and I need to check for the number.

I worked at Western felt from from 1954 to 1964. They paid for my MBA. One of the two founders was my grandfather Henry Faurot. The other founder was my grandfather’s brother-in-law, George Silverthorne. Like many family businesses, they split along family lines and like many family businesses the company was sold and later liquidated. I bought 100 shares at $35.00/share and received $3.50/ share on liquidation. I believe that, at age 90, I am the sole surviving employee!