Museum Artifact: Hand Painted Baseball Figurine, 1940s

Made By: Electric Corp. of America / ECA Toys, Inc. / ECA MFG Co., 2518 W. Montrose Ave., Chicago, IL [Ravenswood]

Dating from the early 1940s, our sleepy ceramic Little Leaguer here was produced a few years after the first Hummel figurines hit the U.S. market, making him a sort of hyper-Americanized, wartime knockoff of those popular German collectibles. The little guy has his own charm, I guess, but the odd part is the manufacturing label under his feet, which claims that the piece was “Hand Painted” in the U.S.A. (not, from the looks of it, by a professional) and distributed by the “Electric Corp. of America, Chicago, ILL.”

It begs the question: Why would a grandiose-sounding tech enterprise like the ELECTRIC CORPORATION OF AMERICA be dabbling in cutesy statuettes for grandma’s curio cabinet?

It begs the question: Why would a grandiose-sounding tech enterprise like the ELECTRIC CORPORATION OF AMERICA be dabbling in cutesy statuettes for grandma’s curio cabinet?

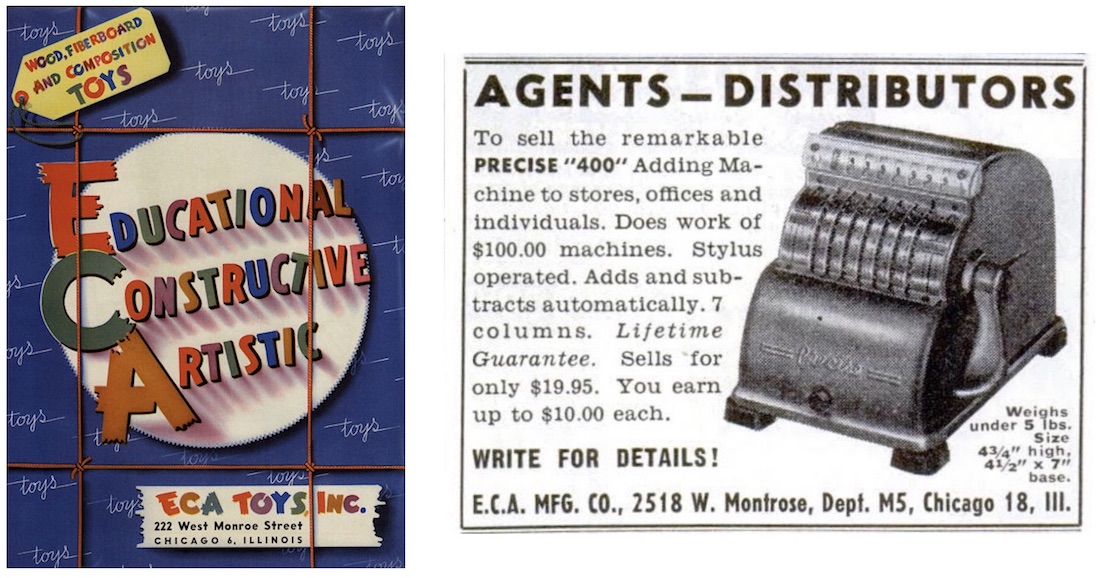

Well, as best I can tell, the company (which was alternately known as the ECA Manufacturing Co. and ECA Toys, Inc.) was a bit unsure of its own identity from the get-go. Only in operation from about 1942 to 1949, it was originally organized for the production of “fluorescent lighting equipment, electric fans and ice cream freezers,” according to a 1942 issue of Electrical World magazine, but even those efforts took an immediate backseat to defense contracting during the war. By 1944, as a likely consequence of metal rationing, ECA took an unlikely foray into the wholesale toy business, selling a range of trains, planes, and games made mostly of “fiberboard and wood.” Where the ceramic and porcelain figures came into play is anybody’s guess—I could find no specific references to the company selling them, hand-painted or otherwise.

By 1948, after the toy business tanked, the ECA MFG Co. got involved with the production of the “Precise 400” brand of office adding machines—which similarly came and went with little fanfare.

[Left: Cover of a 1944 ad sheet for ECA Toys, Inc. Right: A 1948 ad for E.C.A. MFG Co. and its Precise 400 Adding Machine, from Popular Science magazine]

[Left: Cover of a 1944 ad sheet for ECA Toys, Inc. Right: A 1948 ad for E.C.A. MFG Co. and its Precise 400 Adding Machine, from Popular Science magazine]

In a vacuum, the Electric Corp. of America looks like a small business trapped unluckily between wartime limitations and peacetime competition—never able to find its footing and ultimately banished into inconsequence. In the wider context of Chicago industrial history, however, it turns out that the ECA was really more of a brief, liminal moment in a much larger story—a footnote in the otherwise fascinating life of a Chicago original named Leo S. Maranz, founder of the Tastee Freez fast food franchise.

The Maranz, the Myth, the Legend

“[Leo Maranz] is a great businessman. He is the kind of man business needs; a builder and a pioneer. Then he was punished for stepping out too far, too fast.”—Herbert Molner, Exec. V.P. of Tastee Freez, 1968

Born in Chicago to Jewish immigrants from Russia, Leo Maranz (1900-1988) and his three siblings had a humble upbringing, supported by their father Samuel’s earnings as a tailor shop presser. Growing up in the golden age of American innovation proved pretty inspirational, though, and young Leo soon eagerly sought a more fortuitous future in that world.

Born in Chicago to Jewish immigrants from Russia, Leo Maranz (1900-1988) and his three siblings had a humble upbringing, supported by their father Samuel’s earnings as a tailor shop presser. Growing up in the golden age of American innovation proved pretty inspirational, though, and young Leo soon eagerly sought a more fortuitous future in that world.

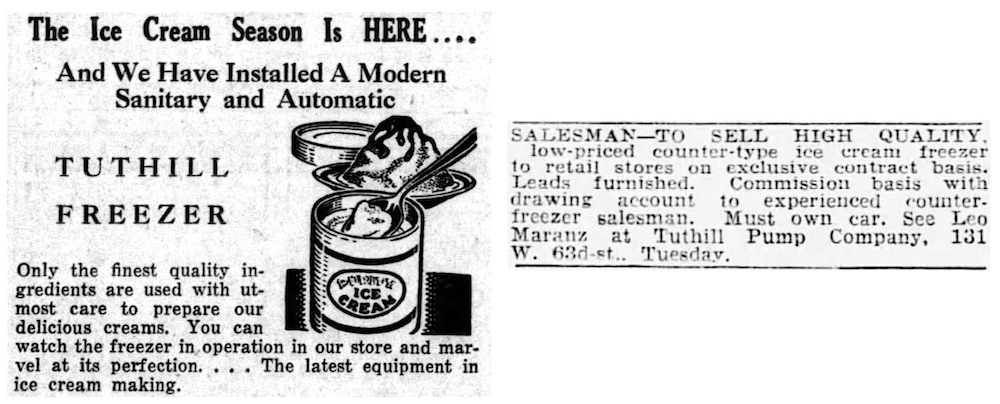

In 1921, he graduated from Chicago’s esteemed Armour Institute of Technology, and as a working mechanical engineer, soon became a specialist in the fairly new arena of electric refrigeration. For years, he worked on his own specialized “ice cream freezers,” selling them around the country independently, then as an employee of the Tuthill Pump Co., aka the Tuthill Freezer Co., during the Depression.

Maranz was singled out in a 1936 edition of the Indianapolis Star as “one of the pioneers in the counter freezer field,” devising some revolutionary methods for creating and sustaining ice cream and related treats at just the right texture and temperature (previously, you pretty much had to eat ice cream in the five minute window in which it was made). The hard part was finding a sustainable business model for selling the expensive freezer technology itself.

[Left: 1935 ad for The Candy Shop in Newport News, VA, touting their new Tuthill Freezer. Right: 1935 ad for Tuthill Pump Co., seeking freezer salesmen. The contact was Leo Maranz.]

[Left: 1935 ad for The Candy Shop in Newport News, VA, touting their new Tuthill Freezer. Right: 1935 ad for Tuthill Pump Co., seeking freezer salesmen. The contact was Leo Maranz.]

Soft serve ice cream was in its infancy, and while the very first Dairy Queen opened its doors in nearby Joliet, Illinois, in 1940, they contracted with a competitor of Maranz, an inventor named Harry Oltz, to build their freezers. Leo was, for lack of a better term, out in the cold.

Deep Freez

From the looks of it, then, the Electric Corporation of America was Maranz’s first big effort to diversify his business and run his own organization. Launched in 1942, the company operated out of two locations throughout its existence: an office at 222 West Monroe and a warehouse / manufacturing facility at 2518 W. Montrose Ave in Ravenswood. The latter building would later become the first headquarters of the Tastee Freez Corp. of America, as well, but has since been demolished.

From the looks of it, then, the Electric Corporation of America was Maranz’s first big effort to diversify his business and run his own organization. Launched in 1942, the company operated out of two locations throughout its existence: an office at 222 West Monroe and a warehouse / manufacturing facility at 2518 W. Montrose Ave in Ravenswood. The latter building would later become the first headquarters of the Tastee Freez Corp. of America, as well, but has since been demolished.

Maranz originally intended to use the ECA as a three-division operation for making (a) freezers (b) electric fans, and (c) fluorescent lights. As noted, though, those plans never really got off the ground.

”During the war there was no equipment built or anything unless it was essential to the war effort,” former Dairy Queen franchisee Gil Stein told the Tribune in 1991. ”There were no new freezers built at the time.’’

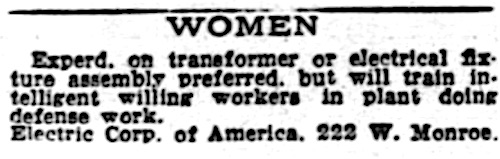

[1942 ad seeking women to work at the ECA factory during the war]

[1942 ad seeking women to work at the ECA factory during the war]

And so, with his freezer production literally scrapped and the fans and lighting similarly shelved for metal rationing, Maranz was forced to do a lot of improvising. Defense work likely gave him the cash influx he needed, but there still needed to be some sort of existing business to return to when the war was over.

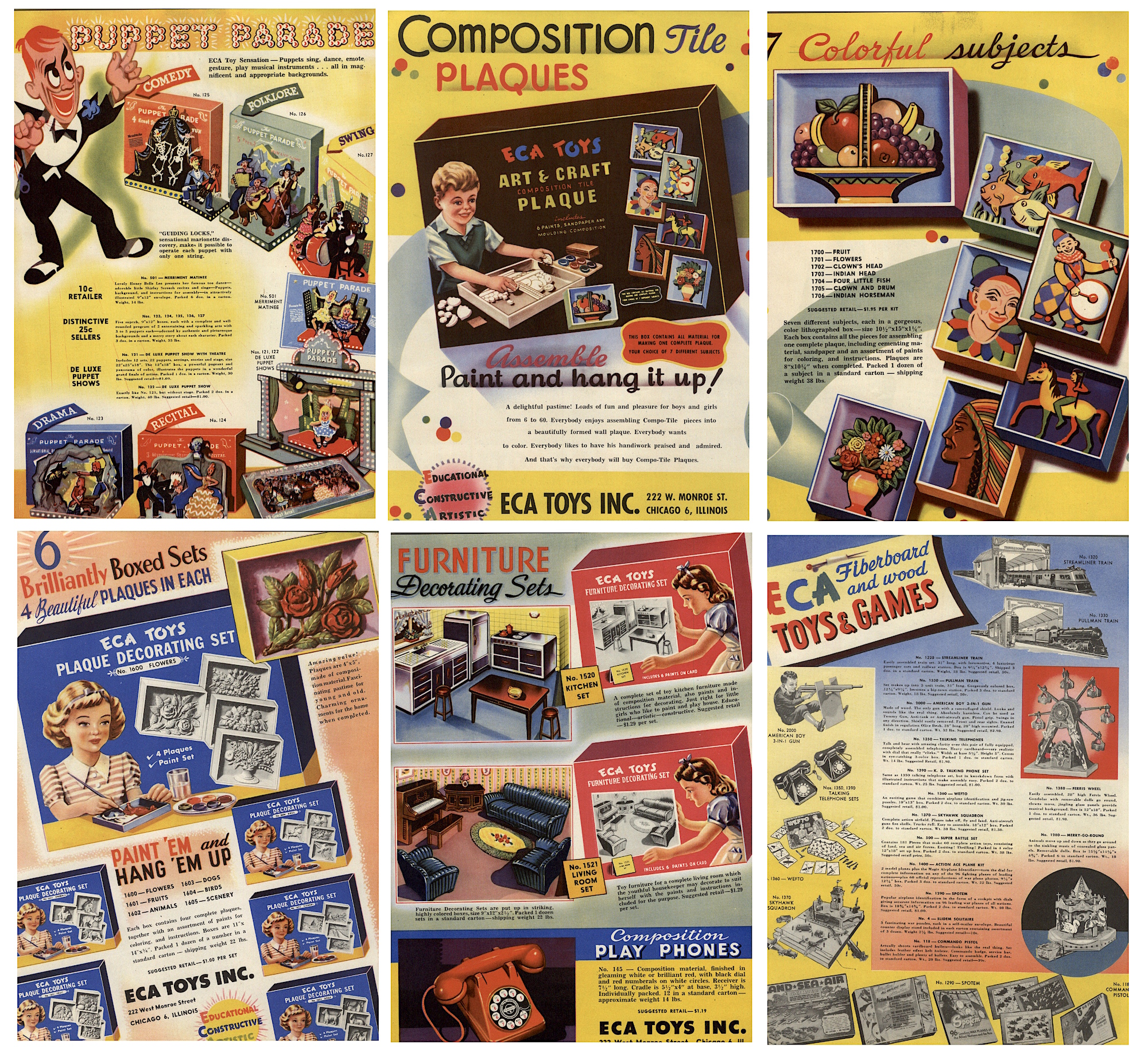

We may never know [or care?] exactly how the diversion into cheap toys came about. Maranz had several different partners in ECA over the years, including J.H. Schwartz and a B-list superhero named Ben Antman. Any one of them, or various outside partners/manufacturers, could have gotten the ball rolling. However it unfolded, ECA Toys somehow developed a pretty substantial catalog of wholesome kids products in a very short time, and it became the main crux of Maranz’s business through 1944 and 1945. The toy division even adapted the ECA name to stand for something new: “Educational, Constructive, Artistic.”

[Images from a 1944 ECA Toys mailer]

[Images from a 1944 ECA Toys mailer]

A lot of ECA’s wartime toy offerings were of the arts and crafts variety. Rather than being hand-painted like our figurine, some items were essentially molds for the kids to colorize themselves.

“Paint ‘Em—Hang ‘Em,” read a blurb in Billboard magazine in 1944. “Brilliantly boxed sets of plaques, together with an assortment of paints for coloring, are being offered by ECA Toys, Inc., Chicago. Educational, constructive, artistic—these toys promise a fascinating pastime for young and old alike. The plaques, coming four in a box, can be obtained in flower, fruits, animals, birds, and scenery designs, and they are said to be charming ornaments for the home when completed. ECA Toys, Inc. is featuring a complete line of other decorating sets, all claimed to be big features in art-craft attractions.”

[Left: Box cover from an ECA Toys doll furniture kit. Right: This newspaper ad from December of 1945 re-identifies the business by its original name, Electric Corp. of America, and seeks dealers to sell metal toys—back in production for the post-war era. This was either a brief movement toward expansion for the ECA toy biz, or more likely, a fire sale en route to its demise.]

[Left: Box cover from an ECA Toys doll furniture kit. Right: This newspaper ad from December of 1945 re-identifies the business by its original name, Electric Corp. of America, and seeks dealers to sell metal toys—back in production for the post-war era. This was either a brief movement toward expansion for the ECA toy biz, or more likely, a fire sale en route to its demise.]

Regardless of how personally involved he may have been on the wholesale toy front, Leo Maranz never let his mind stray too far from his original, very specific specialty: soft serve ice cream technology.

After the war, with metal manufacturing back in play, “Maranz decided that a unique freezer he had designed was too good to be distributed through conventional channels,” according to Harry Kursh’s 1968 book, The Franchise Boom. “Acting as his own distributor, he sold the freezers for $3,300. But often he found that to sell the freezer he practically had to help the buyer start a business, even to the extent of laying out and designing the store for him.

“Mr. Maranz saw no future in this kind of operation. . . But having helped some of his customers start a business, there was the germ of a possible future!”

The Franchise

There are plenty of published accounts of the founding of Tastee Freez—one of the first major fast food chains in America—but none I’ve yet read preface the event with any mention of Leo Maranz’s time as the president of the Electric Corp. of America. Instead, the 1940s are reduced to a hiccup, as Maranz—the struggling 1930s freezer designer—suddenly appears as the head of a major restaurant franchise in 1950.

A 1953 edition of the Lansing State Journal called it “a story of amazing success in one of the toughest business fields. . . A story of how two men, in the best American tradition, parlayed a simple idea into a $1,000,000 business in less than two years.

A 1953 edition of the Lansing State Journal called it “a story of amazing success in one of the toughest business fields. . . A story of how two men, in the best American tradition, parlayed a simple idea into a $1,000,000 business in less than two years.

“Leo Maranz of Chicago manufactured ice cream machines, and Harry Axene worked for an ice cream firm but didn’t like the set-up. . . The pair joined forces in 1950 to form the Tastee Freez corporation. What happened afterward has set the whole business world agog.”

It’s well worth noting that Harry Axene’s previous “ice cream firm” was the granddaddy of them all, Dairy Queen—with whom Axene had helped build the modern framework for how food franchises could operate. Now, facing a power struggle, Axene decided to find a superior soft serve freezer and try to compete with the very beast he’d created. Leo Maranz, who’d been shopping around his various freezers for nearly 20 years by this point, jumped at the opportunity.

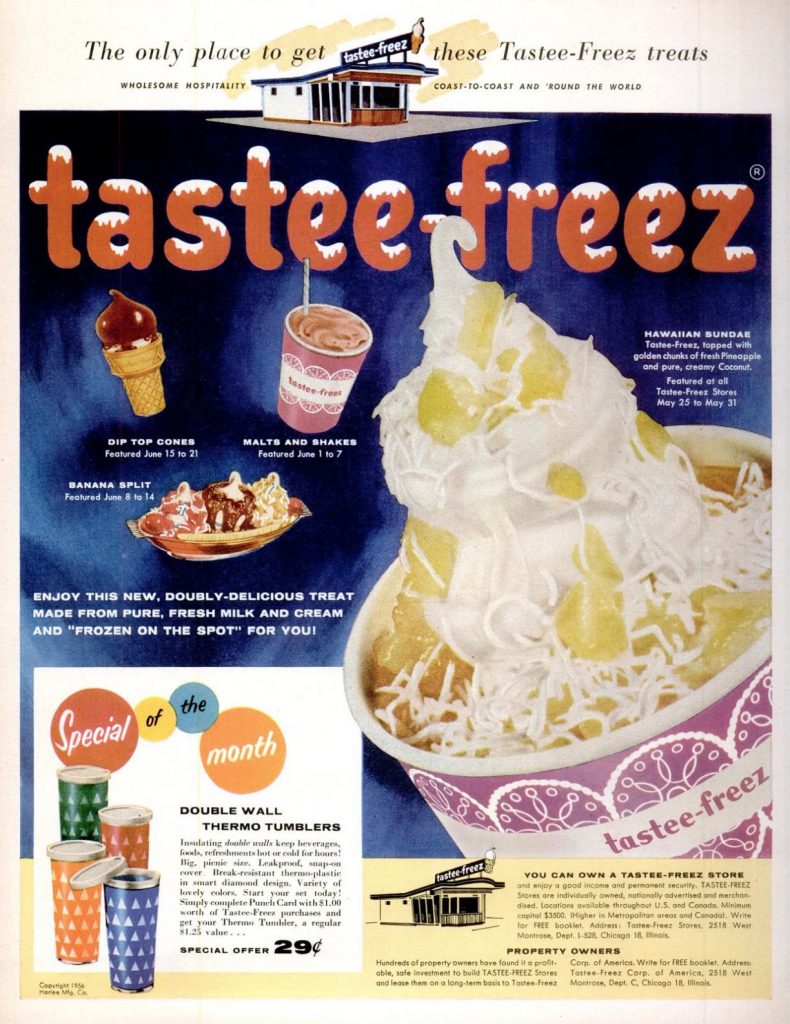

“By 1951, the first store was opened in Chicago,” the Lansing State Journal article continued. “By February, 1953, nearly 500 stores have been opened in nearly every country in the Americas, and in Italy, North Africa and Japan.”

[One of the older surviving Tastee Freez locations in the U.S. (more recently re-named “The Freeze”) is located in Chicago’s Logan Square neighborhood at 2815 W. Armitage Ave.]

[One of the older surviving Tastee Freez locations in the U.S. (more recently re-named “The Freeze”) is located in Chicago’s Logan Square neighborhood at 2815 W. Armitage Ave.]

Basically overnight, the Electric Corp. of America was a distant memory, as Leo Maranz was suddenly at the controls of an international ice cream phenomenon. Now, rather than just selling his machines, he was selling customers their own opportunity to own a piece of the Tastee-Freez business as regional franchise operators.

“Be Your Own Boss,” read a 1954 ad. “If you have $3,000 to $3,500 and would like to be in business for yourself, write, wire or call Tastee-Freez. Over 800 successful stores now in operation. Earnings Large.”

Even though the world now saw him as a millionaire restaurateur, Maranz was still running a manufacturing business in Chicago much as he had been with ECA. His patented soft serve freezers were even made in the former ECA facility on Montrose Avenue. The manufacturing wings of the Tastee Freez Corp. were known as the Harlee MFG Co. and the Freez-King Corporation (production moved to 1200 N. Homan Avenue in the ’60s, then to Des Plaines).

Even though the world now saw him as a millionaire restaurateur, Maranz was still running a manufacturing business in Chicago much as he had been with ECA. His patented soft serve freezers were even made in the former ECA facility on Montrose Avenue. The manufacturing wings of the Tastee Freez Corp. were known as the Harlee MFG Co. and the Freez-King Corporation (production moved to 1200 N. Homan Avenue in the ’60s, then to Des Plaines).

During the height of its growth in the late ’50s and early ‘60s, Tastee-Freez had nearly 2,000 locations and was a legit threat to its old regional rival Dairy Queen. Like DQ, the business expanded its offerings beyond ice cream, as well, offering your standard American fast food fare, along with toy give-aways—some likely plucked from the old backstock of ECA Toys, Inc.

[1956 Tastee Freez ad featuring “America’s Sweetheart Doll”]

[1956 Tastee Freez ad featuring “America’s Sweetheart Doll”]

Painting Into a Corner

Since there are only about two-dozen Tastee Freez restaurants still in business today, you might rightly guess that the bubble burst at some point. The year, specifically, was 1963.

“It was England,” according to a 1968 article in the Detroit Free Press, “that got Maranz and Tastee Freez into trouble. In that country he was working with the famous Lyons restaurant chain, and the Lyons people came up with the idea of putting the Tastee Freez ice cream machine into trucks and creating mobile stores. It was a success in England, but a flat tire in this country.”

Tastee Freez Industries, Inc., which was still headquartered at 2518 W. Montrose Ave. in 1963, filed for Chapter 11 that September, and it looked unlikely they’d ever recover. The Securities and Exchange Commission even froze trading of the company’s common stock, citing “serious questions as to the adequacy of currently available financial information upon which investors may make an informed evaluation.”

Tastee Freez Industries, Inc., which was still headquartered at 2518 W. Montrose Ave. in 1963, filed for Chapter 11 that September, and it looked unlikely they’d ever recover. The Securities and Exchange Commission even froze trading of the company’s common stock, citing “serious questions as to the adequacy of currently available financial information upon which investors may make an informed evaluation.”

Leo Maranz was 63 at this point, and was spending most of his time in Palm Springs, California, basking in the spoils of that hard-earned freezer money. After earning 90 cents per share in 1962, though, his company reported a deficit of $8.82 per share in ’63, along with a $6 million debt related to the ice cream truck debacle.

Tastee Freez rebounded and survived largely thanked to the efforts of Maranz’s young assistant Herbert Molner, who quickly elevated to the role of Exec. Vice President and, by the 1970s, Chairman of an expanded business called TFI Companies, Inc.—which included the now Des Plaines based Tastee Freez as “one of its smaller holdings.” [Herb Molner’s son John Molner, incidentally, is now famous for being TV journalist Katie Couric’s husband].

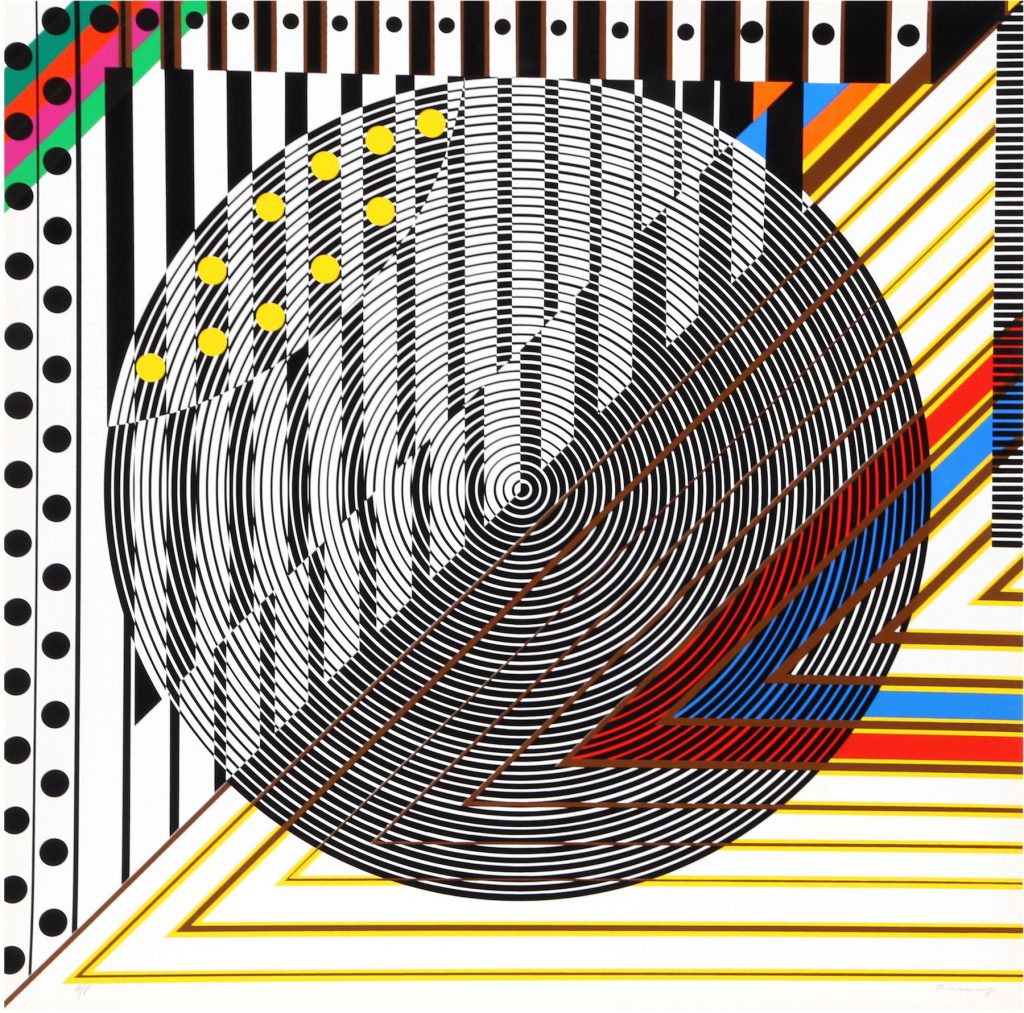

Meanwhile, in retirement, Leo Maranz—liberated from refrigeration—found a whole new outlet for the complex mechanical structures in his mind, emerging as a respected painter of “polished abstract geometrics.”

[“Overture” (c. 1980) is an example of the artwork of Leo Maranz during his later years as a retiree. Due to the intricacy involved in his pieces, he usually only painted about three per year.]

[“Overture” (c. 1980) is an example of the artwork of Leo Maranz during his later years as a retiree. Due to the intricacy involved in his pieces, he usually only painted about three per year.]

“I really didn’t know what I was doing,” Maranz told the Chicago Tribune in 1975, referring to his early experiments as an artist, “but being an engineer, it was very much a natural thing. Accidentally, I found out I was a geometric, hard-edged painter.”

I guess we could call this an ironic twist, since our story began with a “hand-painted” artifact from Maranz’s distant industrial past. From cheap, quaint figurines, an elderly Leo had evolved into a life of luxury and modern art snobbery, as he and his wife Esther spent their winters in Palm Springs and their summers in a 92nd floor apartment in Chicago’s then-new John Hancock Center. The home / studio was created by the famous Chicago interior designer Richard Himmel, who, if it need be said, had nothing to do with Hummels.

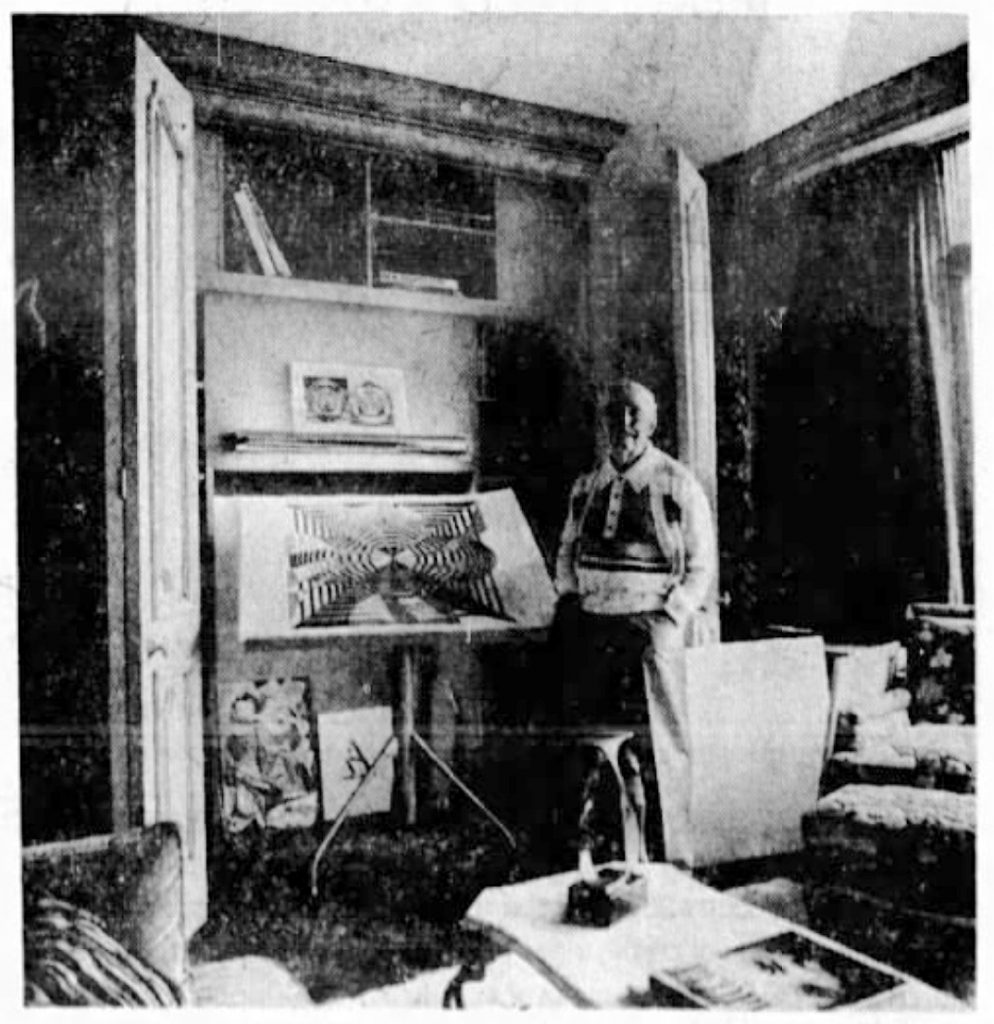

[Leo Maranz in his home art studio on the 92nd floor of the Hancock Building, 1975]

[Leo Maranz in his home art studio on the 92nd floor of the Hancock Building, 1975]

[Special thanks to museum patron Sue Brod of Mundelein, IL, for finding and donating this item!]

[Special thanks to museum patron Sue Brod of Mundelein, IL, for finding and donating this item!]

Sources:

“Vavul Is Distributor for Tuthill Freezers” – Indianapolis Star, May 31, 1936

“Paint ‘Em, Hang ‘Em” – Billboard, Aug 19, 1944

“Story Behind Success Told” – Lansing State Journal, Feb 23, 1953

The Franchise Boom, by Harry Kursh, 1968

“Tastee Freez on Comeback Trail” – Detroit Free Press, Nov 4, 1968

“Meditating: Don’t Laugh, It Works” – Chicago Tribune, April 21, 1974

“Living In One of the Highest Apartments in the World . . .” – Chicago Tribune, Oct 6, 1975

“From Soft Ice Cream Came Franchise Queen” – Chicago Tribune, April 29, 1991

International Dairy Queen, Inc. History – FundingUniverse.com

Archived Reader Comments:

“Prior to Electric Corp. of America / ECA Toys, Inc. / ECA MFG Co. being located at 2518 W Montrose Ave, I find that Playskool Institute Inc. had a manufacturing plant there, and prior to them the manufacturer Thorncraft Inc. operated out of that location. I believe that Thorncraft Inc. bought Playskool in 1935 and then sold it to Joseph Lumber Company in 1938, which at some point renamed their company Playskool Manufacturing Co. My Great Uncle lists his employer on his Draft Card as of 16 Oct 1940 as Playskool Institute Inc. at 2518 W Montrose Ave, Chicago, Illinois. The fact that this location previously was used to produce wooden toys by Playskool may have had something to do with ECA producing wooden toys for a period of time from that location.” —Chas Scidmore, 2020

Good evening Andrew, I have a ceramic figure marked “COPYRIGHT BY ECA 1944”. It is a Victorian Lady measuring 7″ in height. I have not been able to find any information on this figure apart from your article on Electric Corporation of America (ECA TOYS).