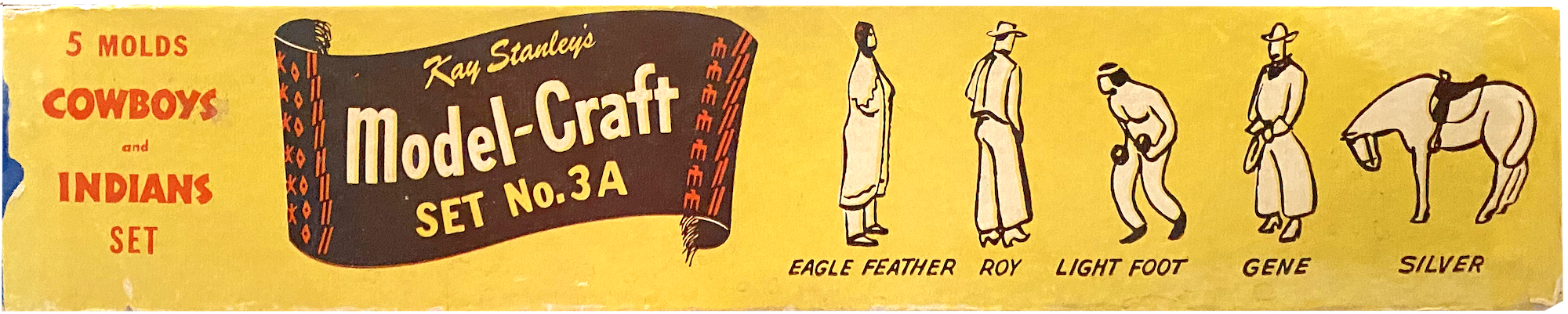

Museum Artifact: Kay Stanley’s Model-Craft Molding & Coloring Set No. 3A – “Cowboys and Indians”, c. 1950s

Made By: Model-Craft, Inc., 521 W. Monroe St., Chicago, IL [Downtown / The Loop]

“Five feet two and weighing 117 pounds, Kay Stanley can be as tough as a truck driver and as charming as a Perle Mesta. At home at any machine in her factory, she is still a charming hostess in her near North Side apartment in Chicago, where she can whip up a barbecue party for 40 people on 24 hours notice.” —Associated Press, 1952

From the late 1940s through the 1950s, Karolyn “Kay” Stanley seemed like the perfect manifestation—or womanifestation—of post-war female empowerment. As a middle-aged divorcee with no children, she laid waste to archaic ideas of the “sad old maid,” and instead garnered regular media attention as both a successful, self-made industrialist and a prominent socialite. Model-Craft, Inc., the toy manufacturing business she founded and operated, employed over 100 workers (almost entirely women) at its Chicago plant and posted million-dollar sales figures, boosted by exclusive licensing deals with major corporations like Disney and Pillsbury. Newspapers and magazines across the country profiled Stanley as a resourceful “Lady Tycoon” who had funded her own start-up and taught herself to repair the old machinery in her factory. Impressed reporters would then make repeat visits to showcase Kay’s latest home decorating project or the celebrity pancake parties she hosted in her swanky Gold Coast brownstone.

From the late 1940s through the 1950s, Karolyn “Kay” Stanley seemed like the perfect manifestation—or womanifestation—of post-war female empowerment. As a middle-aged divorcee with no children, she laid waste to archaic ideas of the “sad old maid,” and instead garnered regular media attention as both a successful, self-made industrialist and a prominent socialite. Model-Craft, Inc., the toy manufacturing business she founded and operated, employed over 100 workers (almost entirely women) at its Chicago plant and posted million-dollar sales figures, boosted by exclusive licensing deals with major corporations like Disney and Pillsbury. Newspapers and magazines across the country profiled Stanley as a resourceful “Lady Tycoon” who had funded her own start-up and taught herself to repair the old machinery in her factory. Impressed reporters would then make repeat visits to showcase Kay’s latest home decorating project or the celebrity pancake parties she hosted in her swanky Gold Coast brownstone.

You might be thinking it’s a shame you’ve never heard about this fascinating woman until now. The much sadder truth, however, is that we don’t actually know what became of her.

Despite the highly public image Kay Stanley maintained for years, her later life reveals a rapid fade into obscurity, to the point that any information beyond the early 1960s seems virtually non-existent—no further trace of her career, home addresses, or even a death certificate, obituary, or gravestone. One possibility is that she remarried, took a new name, and then diverged from the sort of paper trail required by today’s online ancestry algorithms. As a woman without a husband or children, though, it’s also possible that Kay Stanley simply went overlooked by society once the “novelty” of her story wore off.

Fact is, no Chicago business man who achieved Kay’s level of success and notoriety would ever have seen his fate reduced to a mystery. We can only hope someone who finds this article will be able to help us fill in some of the blanks in the narrative. Otherwise, we’re left with a half-told tale of a woman who broke the mold—ironically, by manufacturing molds.

History of Model-Craft, Inc., Part I: Special Kay

Here’s what we DO know about Kay Stanley and her business.

Born Karolyn C. Cotten in Albion, Michigan, circa 1905, she was the only child of Ruth and Oliver M. Cotten, multi-generational Michiganders. Her father was an accomplished pianist and served as the musical director of the Orpheum Theatre Circuit through much of the early 1900s. As a result, Kay spent “most of her girlhood traveling and living in hotels with her parents.” It was only in her late teens late her family settled down more properly, as Oliver Cotten opened a resort hotel of his own in the early 1920s, located on Indian Lake near Dowagiac, Michigan.

Young Kay “was expected to become a musician like her father,” according to one Associated Press featurette. “She did fiddle away at a violin for a few years because her father bribed her with everything from a new dress to an automobile. But it didn’t take.”

Young Kay “was expected to become a musician like her father,” according to one Associated Press featurette. “She did fiddle away at a violin for a few years because her father bribed her with everything from a new dress to an automobile. But it didn’t take.”

Violin lessons aside, Kay Cotten found plenty of activities to occupy her time in high school, joining the glee club, chorus, French club, oratory group, and yearbook staff, all while serving as vice president of her senior class at Dowagiac Union High School. In the 1922 yearbook, her fellow students described her with a couplet: “She’s a small blond / Of whom we’re all fond.”

The term “go-getter” would already seem fitting, and Kay never deviated from that reputation. After college, she finally wound up following in her father’s footsteps, only it was in the world of hotel management rather than music.

Showing a “flair for the business world,” she “entered the hotel business and in a year and a half rose from furniture checker to manager of a Chicago hostelry.”

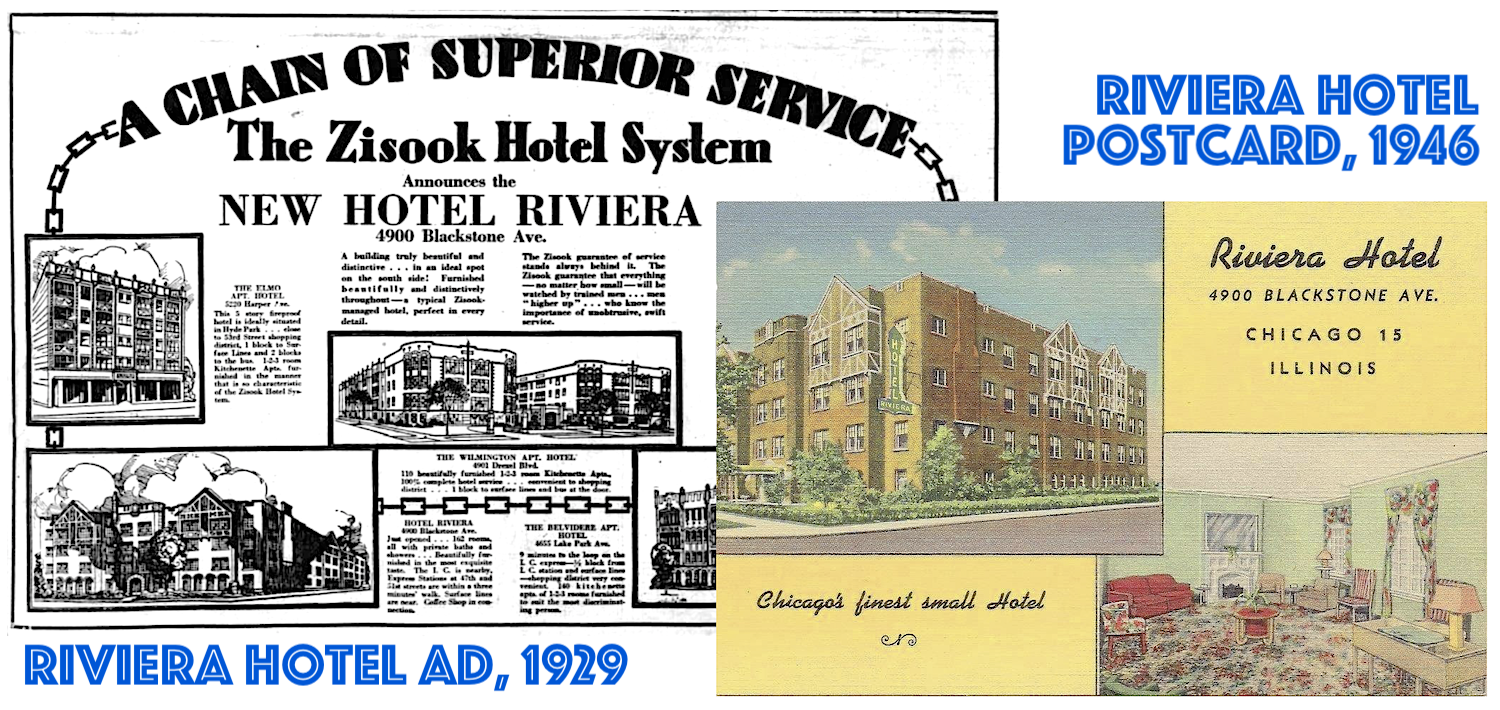

[Fresh out of college, Kay Cotten got a job with the Zisook Hotel Chain, and by 1930, she was managing the new Riviera Hotel in Chicago’s Hyde Park neighborhood. She may have been the youngest female hotel manager in America at the time.]

Indeed, by 1930, still shy of her 25th birthday, Kay Cotten was supposedly the youngest female hotel manager in the country. Working in sales for the Zisook hotel chain, she was put in charge of the company’s newly built Riviera Hotel at 4900 Blackstone Avenue in Hyde Park—an upscale, 162-room accommodation operating during the heart of the Depression and the crossfire of Chicago’s Prohibition gang wars. Even in the 21st century, one could marvel at a young woman running an establishment like this. For her own time, Kay was clearly cut from a different cloth—not merely rebellious like some of her contemporary flappers, but absolutely driven to make her own way in life.

Naturally, there were some bumps in the road. In the worst years of the Depression, Kay was forced to return home for a while, helping her father with the family hotel outside Dowagiac. Somewhere along the line, she also met a Lithuanian-born, Chicago-based salesman named Jay Stanley, who (briefly) became her husband.

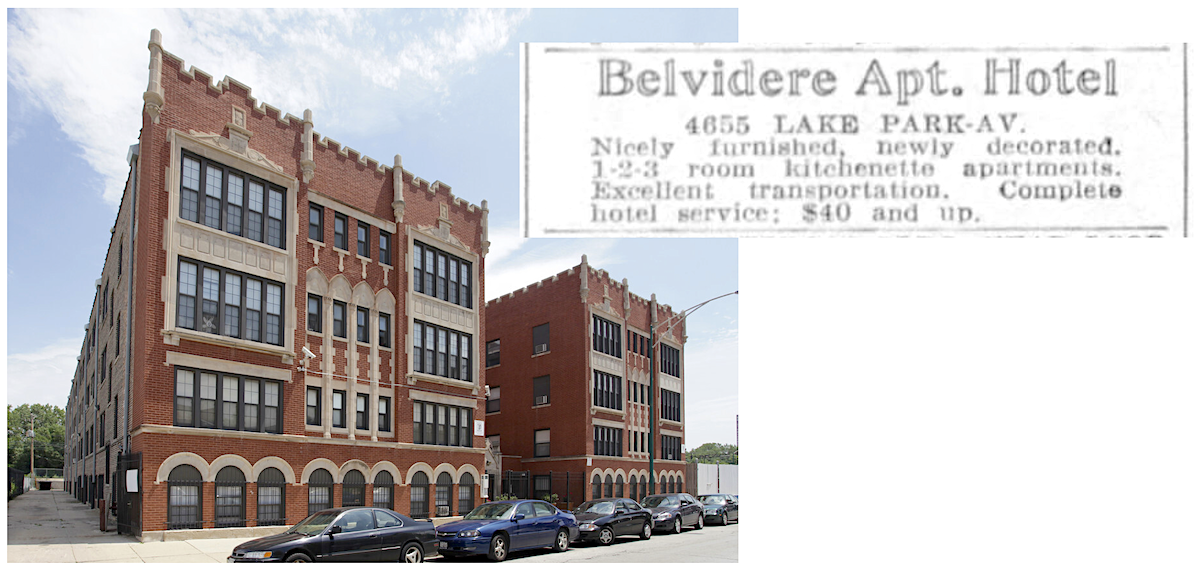

The couple settled back in Chicago in the late 1930s, where Kay came to manage another Zisook property, the Belvidere Apartment Hotel at 4655 S. Lake Park Avenue (now the South Lake Park Apartments). The Stanleys also made their home in the same building.

Oddly, again, we were unable to find a marriage certificate or newspaper notice to confirm Kay and Jay’s nuptials, nor do we know exactly when they decided to cut ties. The relationship likely lasted less than a decade, though, as Jay Stanley is listed as divorced and living alone in the 1950 census, while Kay Stanley—despite the new surname—was back on her path as an independent entrepreneur.

[Kay and her husband Jay Stanley managed and lived at the Belvidere Apt. Hotel, 4655 S. Lake Park Avenue, as late as 1940. The advertisement above is from that year. The photo is of the same complex in 2022, looking much as it would have in Kay’s day.]

II. The Rubber Meets the Road

“The nation’s only woman to own and direct a major toy making business, Miss Stanley has made a notable success in the highly competitive toy-and-game field, where new gimmicks blossom as thickly as dandelions and are about as welcome.” —Chicago Tribune, Nov 20, 1952

In the early 1940s, Kay Stanley was briefly adrift—her marriage was nearing an end, the hotel business was going along with it, and her attempt to jump into the office equipment industry was undercut by metal shortages brought on by World War II. That’s when “this resourceful young woman peered around for other possibilities,” as the Tribune’s Ruth MacKay wrote after interviewing Stanley for her “White Collar Girl” column in 1946. “One of her salesmen had been interested in toy molds as a sideline, and when Miss Stanley took a look at them she decided this was it!”

In the early 1940s, Kay Stanley was briefly adrift—her marriage was nearing an end, the hotel business was going along with it, and her attempt to jump into the office equipment industry was undercut by metal shortages brought on by World War II. That’s when “this resourceful young woman peered around for other possibilities,” as the Tribune’s Ruth MacKay wrote after interviewing Stanley for her “White Collar Girl” column in 1946. “One of her salesmen had been interested in toy molds as a sideline, and when Miss Stanley took a look at them she decided this was it!”

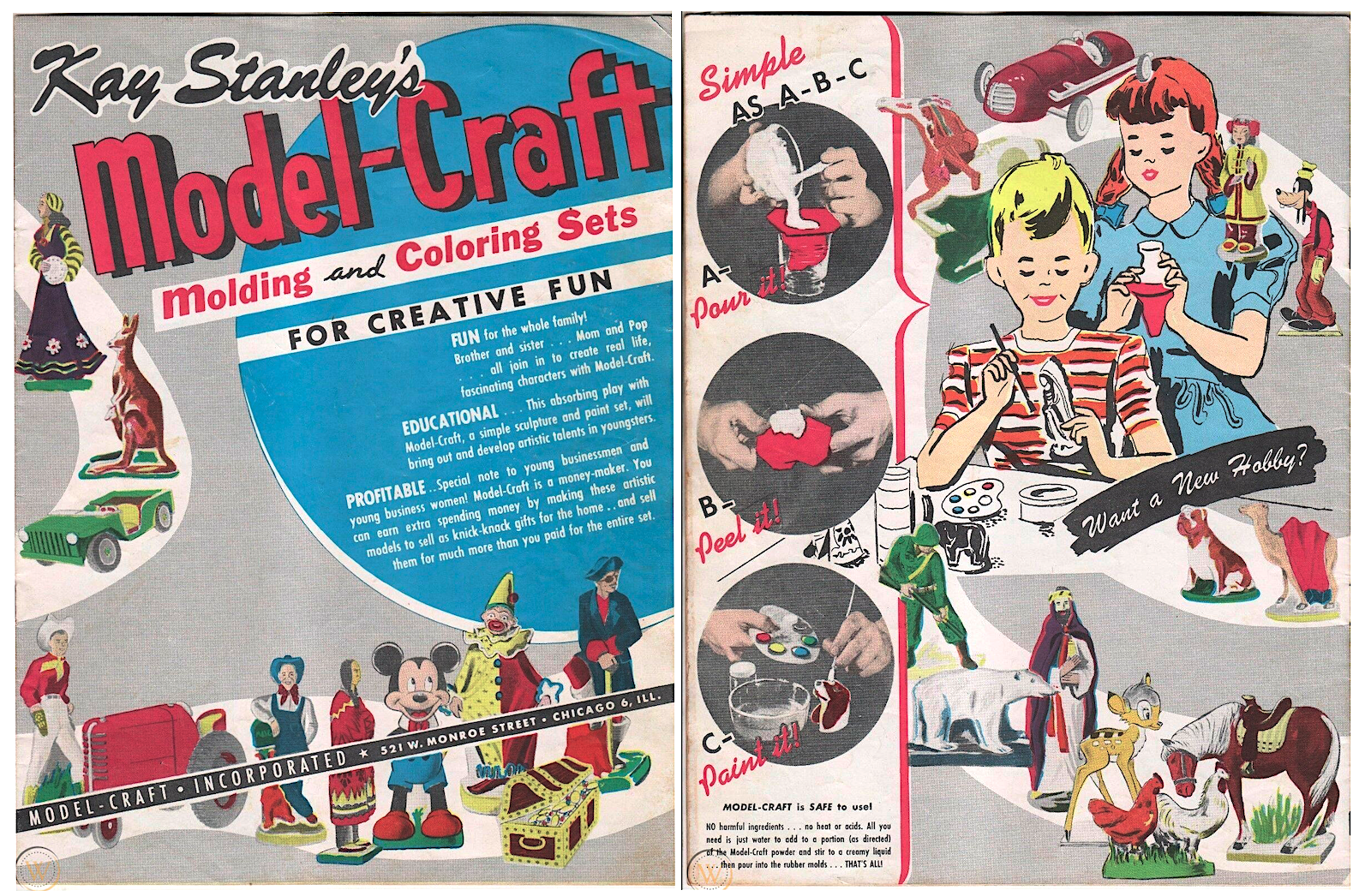

Rubber molding kits had entered the toy market before, with mixed results. In theory, they offered the same creative outlet as products like TinkerToy or Lincoln Logs, since children could “create” their own characters from each mold, using basic watercolor paints to bring the figurines to life. Unfortunately, compared to simple wood or plastic toys, rubberized molds (in addition to the required paints and molding powder that went with them) were hard to produce on a large scale, and in the eyes of many parents, too messy and pungent to be worth the productivity a kid might find in them.

Kay Stanley quickly discovered the smell issue early in her own experiments cooking her first crude rubber molds in small rented factory spaces.

“I was evicted twice because of the odor,” she later claimed, further noting that none of the big Chicago toy buyers showed any interest in her early product pitches. “Everyone told me to quit. But I was too dumb to get out. I thought something would happen and it finally did.”

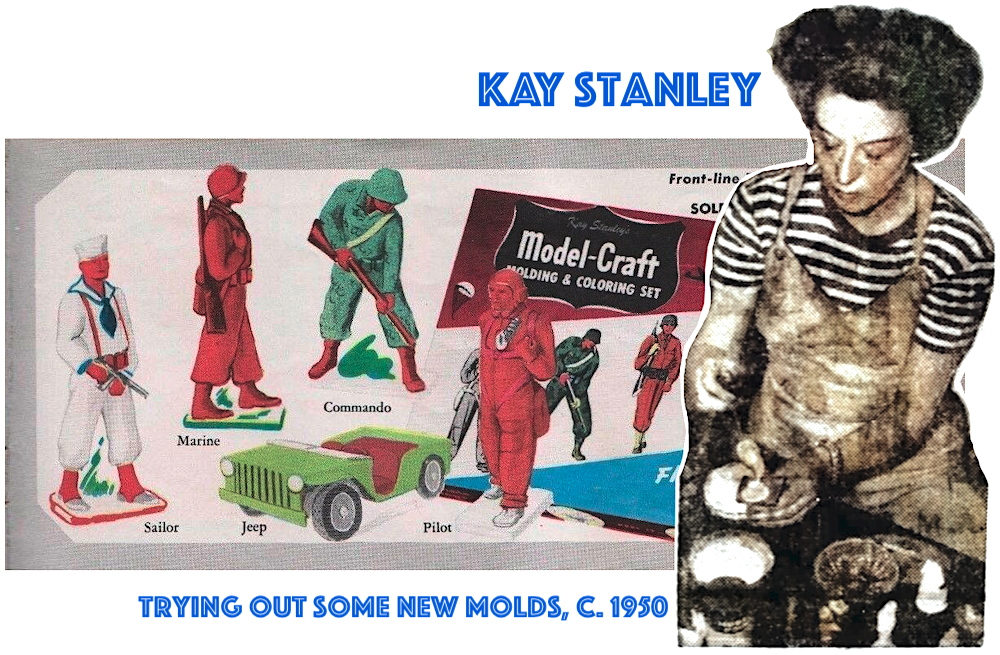

Borrowing money from her grandmother to get started, Stanley hired a ragtag team of 13 workers—the maximum number the War Production Board would allow her in 1942. Like her, they were all women looking for a new opportunity.

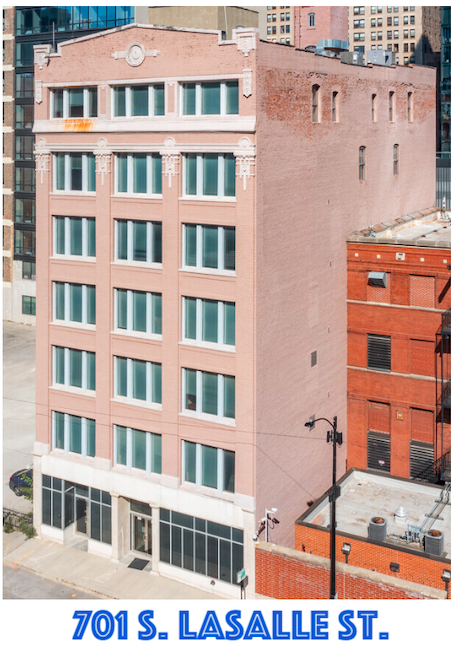

Kay named her new business Model-Craft, Inc., and rented a small factory office inside a seven-story building at 701 South Lasalle Street (that building is still standing as of 2022).

“I couldn’t get repairmen to fix my machinery,” she told the Tribune, “so I had to learn to take it apart and fix it myself. All of it had to be second hand in those days and none of it worked.”

“I couldn’t get repairmen to fix my machinery,” she told the Tribune, “so I had to learn to take it apart and fix it myself. All of it had to be second hand in those days and none of it worked.”

Stanley rarely asked other people to solve problems for her. As an example, when one of her shipping clerks was caught selling company inventory off the books, Kay fired her and took on those shipping duties herself. Shortly thereafter, she encountered a delivery driver who clearly didn’t realize who he was talking to. “I had a deal with the girl who did this job before you,” he told Kay in the loading bay. “We could do the same deal. Your boss never needs to know about it.” That didn’t end well for that fella.

The only people Kay Stanley was dependent on were the toy distributors and retailers of America, and it took a while to win them over.

“Toy buyers are besieged with inventors and promoters of new ideas,” she once said. “But they are afraid to order these new toys because most of their originators can’t produce them in quantity.”

By the end of the war, Kay had proven that she was one of the originators who COULD deliver what she promised, and as orders for Model-Craft kits increased, she was able to increase her workforce to 50 women.

“Miss Stanley is usually in overalls,” Ruth MacKay wrote upon meeting the lady toy tycoon in 1945, “altho when I saw her she was feminine in light blue gabardine with darker blue accessories. She believes wholeheartedly that girls are foolish to ‘grow mannish in business’ . . . believes that women can be successful [she has another woman, Bohnnie Hrdlicks, associated with her in the management of the company and female help throughout the plant] . . . fears that women sometimes do not accept success gracefully, but tend to grow self-important [‘No one is so very important,’ she says] . . . thinks it invaluable to learn to ‘roll up your sleeves and do a job that is necessary’ but to parcel out other jobs and not do the unnecessary.

“Her own career? She takes little credit for astuteness—insists that ideas heckle her until she does something about them.”

In 1946, Kay started turning one of those nagging ideas into another breakthrough for her business. While making generic molds of animals and soldiers was all well and good, she knew that if she could work out licensing deals with other popular entertainment properties, a whole new audience for Model-Craft kits would instantly come with them. So she started making some calls.

[Animated GIF showing the painting of molds from Model-Craft’s “Alice in Wonderland” set. GIF made by Matt at vintagedisneyalice.blogspot.com]

III. Great Days in the Eisenhower Age

“A perfect gift for all year-round. Make your own Disney characters! It’s fun, creative and educational. Model-Craft provides a complete set of materials, including a new style of rubber mold (which may be used again and again), modeling powder, color paints, and all instructions. Model-Craft is the leader in its field with 21 complete sets and 250 characters. $3.” —Model-Craft advertisement, 1948

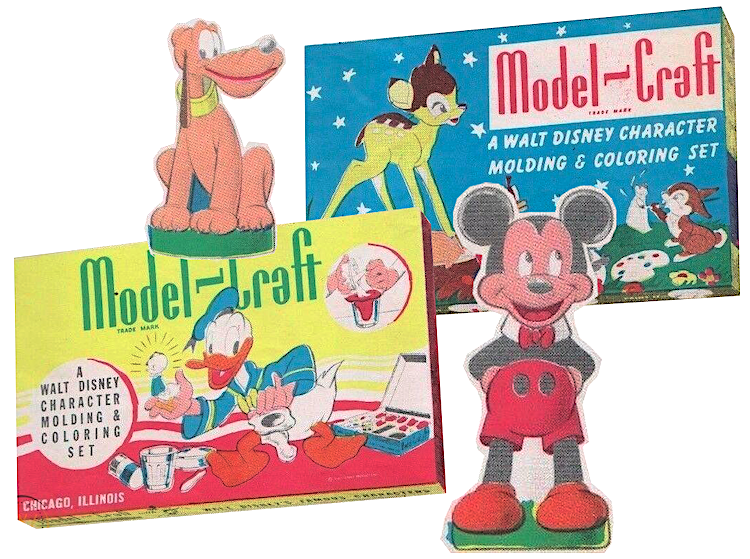

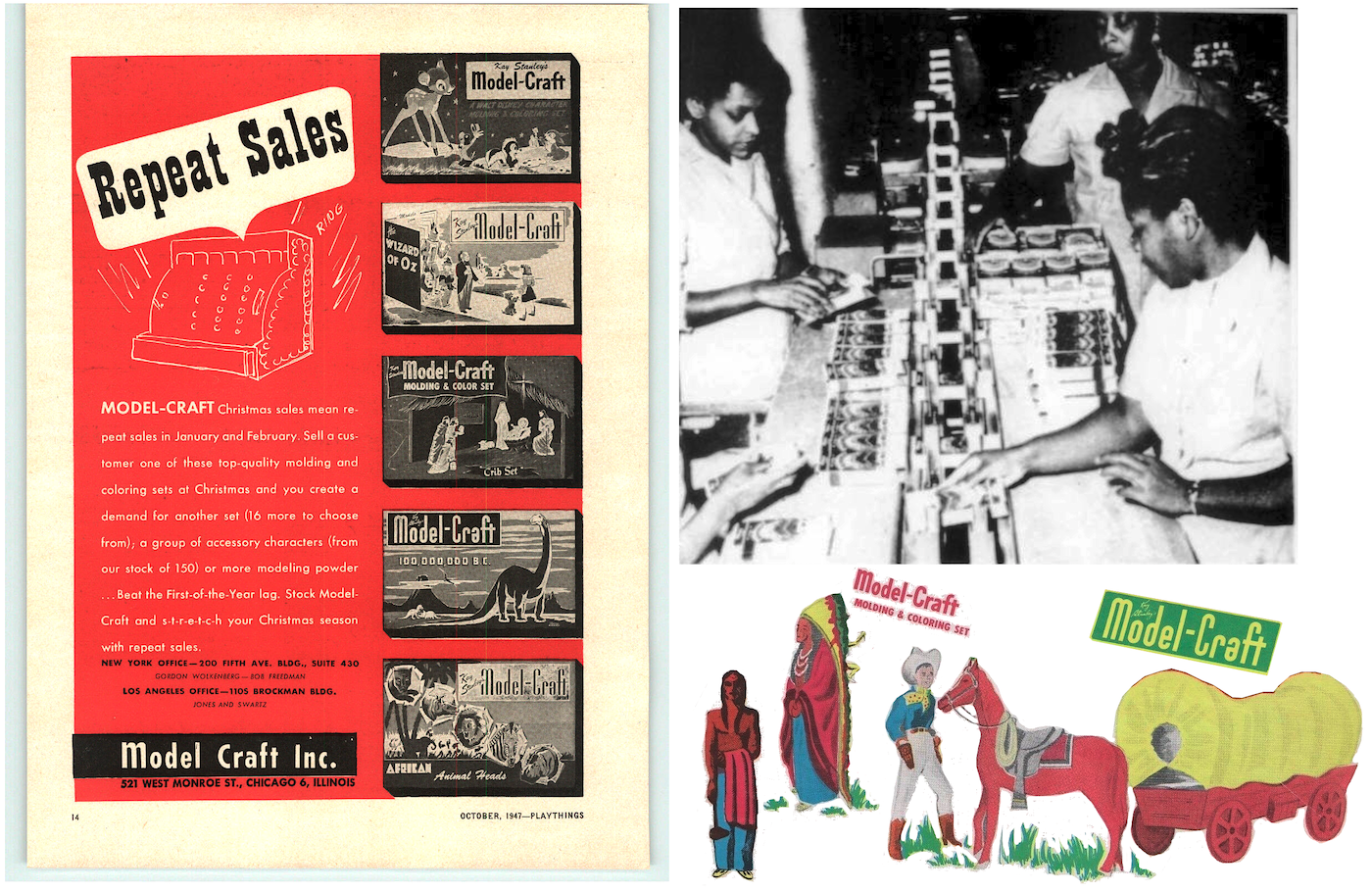

Franchising and licensing deals didn’t quite carry the same cache in the ‘40s and ‘50s as they do in the 21st century, but it’s safe to assume there were still celebrations in the Model-Craft offices when Kay Stanley signed a deal to make rubber mold kits for various Disney properties, including classic character sets (Mickey, Donald, Goofy, etc.) and sets tied to films, including Bambi, Dumbo, and Alice in Wonderland.

Franchising and licensing deals didn’t quite carry the same cache in the ‘40s and ‘50s as they do in the 21st century, but it’s safe to assume there were still celebrations in the Model-Craft offices when Kay Stanley signed a deal to make rubber mold kits for various Disney properties, including classic character sets (Mickey, Donald, Goofy, etc.) and sets tied to films, including Bambi, Dumbo, and Alice in Wonderland.

Other early sets included “The Wizard of Oz,” “100,000,000 BC” (with dinosaurs), “Combat G.I.,” “Zoo,” “Space Cadets,” and the set in our museum collection, “Cowboys and Indians,” which came with five characters (two cowboys, two Indians, and one horse . . . all of them unavoidably a bit stiff looking), an instruction booklet, and a can of modeling powder.

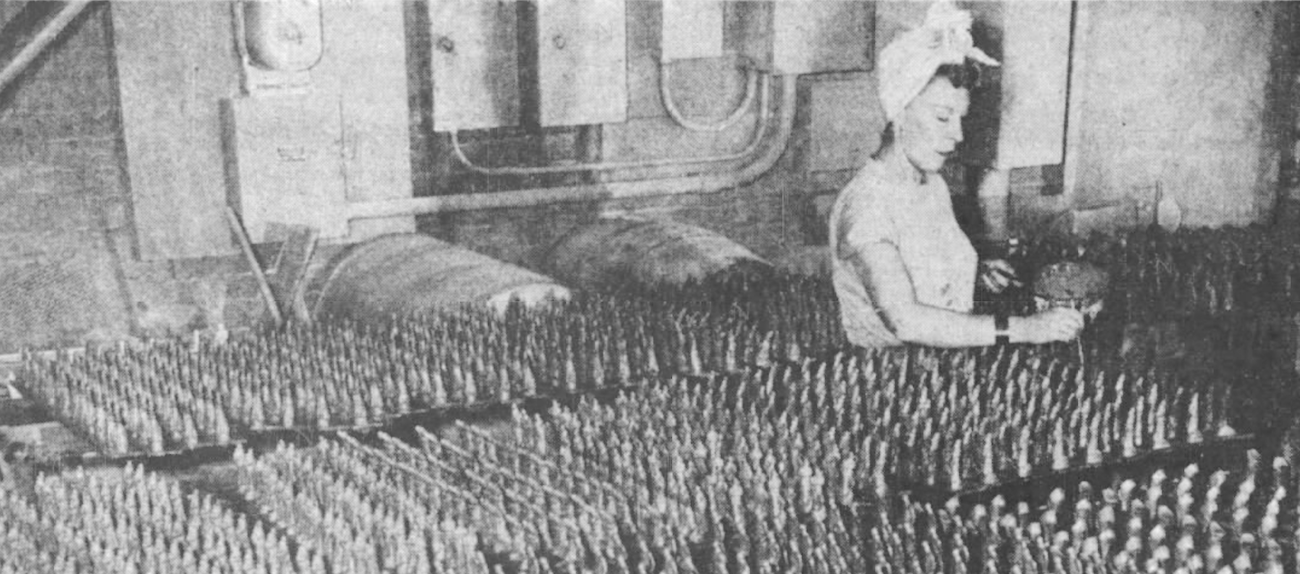

Popular at summer camps or as an activity for Girl Scout and Boy Scout troops, these sets were supposedly better than those of the past, because the durable molds could be used “hundreds” of times. More often than not, though, once or twice was probably all a kid was interested in. Then it was time for a brand new set, which was all the better for the busy Model-Craft factory—now operating out of its own dedicated three-story building in the West Loop, and still employing a largely female and increasingly African-American workforce.

[Left: Ad in a trade magazine for Model Craft sets, 1947. Top Right: Women working a packaging line at the Model Craft factory at 521 W. Monroe Street, 1953. Bottom Right: Some Cowboy and Indian characters from the Model Craft catalog, circa 1950.]

“Today, the Stanley toy factory at 521 Monroe St. turns out 40,000 molds daily during the mid-June to mid-December Christmas rush,” the Tribune reported in 1952. “Her 100 blue-jeaned and bandana-d employees splash liquid rubber over thousands of plaster molds every hour, working in a room where even the walls, floors and windows are splattered with molten red rubber and the air is full of plaster and powder dust. Miss Stanley works part-time at a comma shaped desk, part-time in jeans and bandana supervising the factory.

“Her modeling kits are sold in big department stores, promoted in leading mail order catalogs, approved by toy councils and child guidance advisors—thus, considered a standard plaything for small fry.”

“Her modeling kits are sold in big department stores, promoted in leading mail order catalogs, approved by toy councils and child guidance advisors—thus, considered a standard plaything for small fry.”

While parents still purchased the majority of their kids’ toys in the early 1950s, Stanley saw that trend changing as post-war children started using their allowance money to choose their own entertainment. She also recognized that a lot of kids want toys that mimic reality or make them feel more like grown-ups. “I don’t play down to children any more in designing toys,” Kay told the Tribune. “They seem smarter every year. . . . The day of fairy tales for children is dead. All the children I’ve talked to want me to put out a homicide kit!”

As far as we know, “Kay Stanley’s Homicide Kit” never hit the market, but shortly after that 1952 interview, she did introduce what would become her most successful product—and it was inspired by a similar idea of miniaturizing the real world.

[Kay Stanley doing her best Lucille Ball impression as she personally breaks up a bottleneck in the Model-Craft production line inside the factory at 521 W. Monroe St., 1952]

IV. Having Your Cake

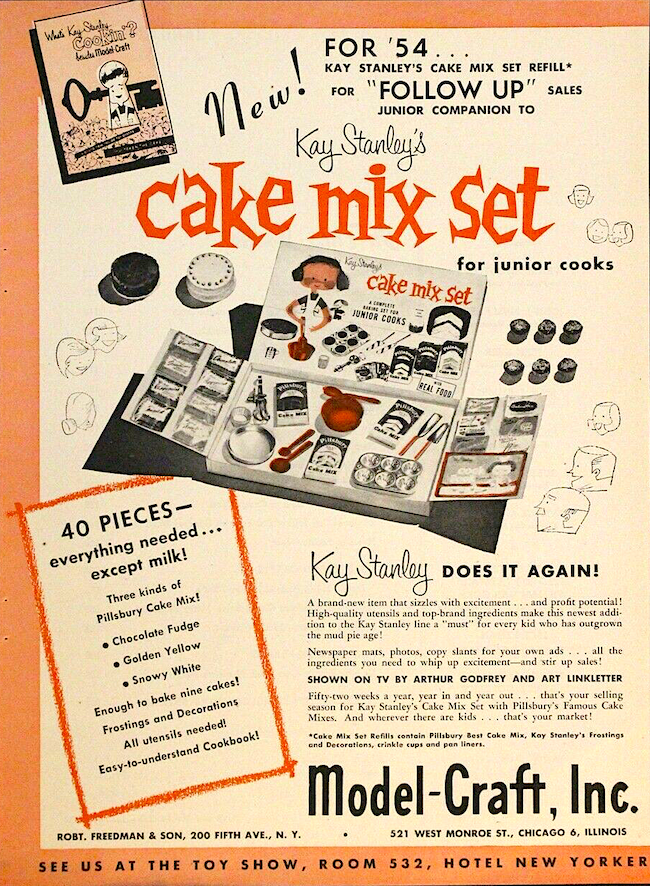

“Kay Stanley’s Cake Mix Set for Junior Cooks” debuted more than a decade before the Easy Bake Oven, and was a similar overnight sensation, catapulting Model-Craft, Inc. into multi-million dollar sales. Once again, Kay had also managed to find the perfect corporate partner to improve her product’s nationwide prospects.

“In Chicago, Kay Stanley, founder and president of Model Craft, Inc., found a bonanza in a tie-up with Pillsbury Mills in developing a toy cake-mix set,” the magazine Modern Packaging reported in 1953. “The set contains real miniature packages of Pillsbury cake-mix flour together with child-sized baking pan, spoons, cup-cake tin, mixing bowl, egg beater, pan liners, etc., all scaled to working size for three-to-nine year-olds. Through research the toy company and Pillsbury established the right dimensions and ingredient quantities so that the cakes would not become over-done in the regular baking time.”

“In Chicago, Kay Stanley, founder and president of Model Craft, Inc., found a bonanza in a tie-up with Pillsbury Mills in developing a toy cake-mix set,” the magazine Modern Packaging reported in 1953. “The set contains real miniature packages of Pillsbury cake-mix flour together with child-sized baking pan, spoons, cup-cake tin, mixing bowl, egg beater, pan liners, etc., all scaled to working size for three-to-nine year-olds. Through research the toy company and Pillsbury established the right dimensions and ingredient quantities so that the cakes would not become over-done in the regular baking time.”

“Kay Stanley does it again!” read a 1954 ad in a toy dealers magazine, which noted that the Cake Mix Set included 40 pieces in total, including “three kinds of Pillsbury Cake Mix, chocolate fudge, golden yellow, and snowy white—enough to bake nine cakes! . . . High quality utensils and top-brand ingredients make this newest addition to the Kay Stanley line a ‘must’ for every kid who has outgrown the mud pie age!”

As with the rubber molding kits, parents didn’t always enjoy the clean-up job that came along with giving their child a swing at real-life baking. But Kay Stanley would re-assure her customers that these unique toys were “in line with the new psychological approach to play. Psychologists maintain a child has to do easily what he or she visualizes as very difficult. So when a girl bakes a cake and frosts it or a boy makes a molded figurine and paints it, both think they have accomplished something wonderful.”

With her name on the package of every Model Craft product, Kay Stanley clearly didn’t mind making herself a key part of her company’s marketing campaigns. And over time, the line between her true self and her carefully crafted public image began to blur.

In the mid 1950s, Stanley purchased a four-story Victorian brownstone house at 1315 Ritchie Ct. and gave it a full modern remodel. On many Sundays thereafter, she’d invite her sophisticated friends (and the local Chicago media) to come enjoy the home and take part in lavish food-themed parties, with Kay playing the role of a real-life Betty Crocker.

“The pancake party is Miss Stanley’s solution to the problem of feeding and feting friends who make it a custom to come calling early on a Sunday,” wrote the Tribune’s Joan Beck in a 1954 edition of the paper’s Family Living section. Stanley had to schedule Sunday, Beck added, because it was “the only day the pretty toy maker takes off from the multimillion dollar business she originated and operates.”

“The pancake party is Miss Stanley’s solution to the problem of feeding and feting friends who make it a custom to come calling early on a Sunday,” wrote the Tribune’s Joan Beck in a 1954 edition of the paper’s Family Living section. Stanley had to schedule Sunday, Beck added, because it was “the only day the pretty toy maker takes off from the multimillion dollar business she originated and operates.”

Another Tribune piece in 1956 describes Kay’s kitchen as “echoing with merry hubbub as guests gleefully help prepare foods which they will savor later. Neat rows of jars—we counted 80!—containing herbs ensure distinctive flavoring for party menus and daily fare. A knowing herbalist, Mrs. [sic] Stanley grows eight varieties in her summer garden.”

Kay Stanley was over 50 by this point, but only seemed to be hitting her stride as a new icon of both American industry and domesticity. This makes it all the more strange that Model Craft, Inc. was already entering its last hurrah.

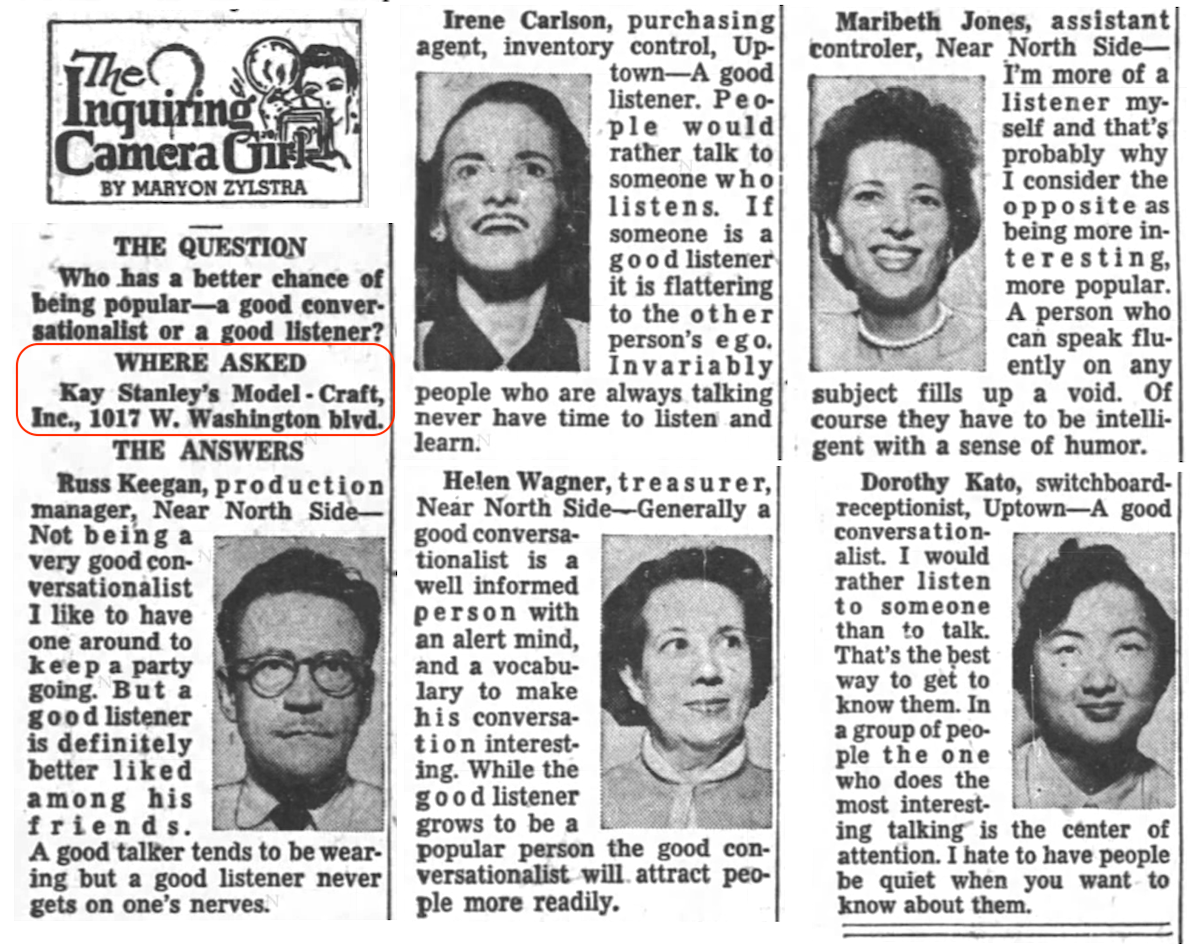

[The Chicago Tribune’s “Inquiring Camera Girl” Maryon Zylstra visited the Model Craft Inc. offices at 1017 W. Washington Blvd. in 1954, and five employees shared their opinions on whether it was better to be a good listener or a good conversationalist. Participants were production manager Russ Keegan, purchasing agent Irene Carlson, treasurer Helen Wagner, assistant controler Maribeth Jones, and switchboard receptionist Dorothy Kato.]

V. What Became of Kay Stanley?

“Kay Stanley, Chicago’s glamorous toy tycoon, vacationing in Panama, spent an afternoon at the Juan Franco race track the day before President Jose Remon was assassinated there. Kay lost some loot and felt a little unhappy . . . until somebody pointed out that the box she’d occupied was riddled with machine gun bullets 24 hours later. Brr!” —Herb Lyon, Chicago Tribune, Jan 6, 1955

While her business continued to develop new products in the late 1950s, including “Kay Stanley’s Fashion Show” and “Kay Stanley’s Bat-Em . . . Catch-Em” (a battery operated baseball pitching machine), Miss Stanley had likely outgrown the days of donning her own bandana on the factory floor.

Model-Craft and a shadow business, Kay Stanley, Inc., maintained corporate offices at 1017 W. Washington Blvd. during this period, but by 1958, the once bustling factory at 521 Monroe Street seems to have been left behind, as more and more manufacturing was outsourced to other suppliers.

Model-Craft and a shadow business, Kay Stanley, Inc., maintained corporate offices at 1017 W. Washington Blvd. during this period, but by 1958, the once bustling factory at 521 Monroe Street seems to have been left behind, as more and more manufacturing was outsourced to other suppliers.

While we can’t yet confirm it, our best guess is that Kay Stanley may have struck a deal with one Chicago toy manufacturer, in particular—Plastic Block City, Inc.—to take over production of most if not all Model-Craft products.

Plastic Block’s plant was located at 4223 W. Lake Street, but their offices in 1960 are listed at 1017 W. Washington address; the same building that was the last known home of Model-Craft.

The clearest connection between the two entities comes in 1961, when the Food and Drug Administration suddenly called for remaining sets of “Kay Stanley’s Cake Mix Set” to be pulled off the shelves, citing their analysis that the strawberry frosting mix included in the kit contained FD&C Red No. 1, an unsafe additive. The FDA report identified Plastic Block City, Inc. as the manufacturer of the product, and cited their address as 1017 W. Washington Blvd., Chicago.

Plastic Block City consented to remove the strawberry mixes from all future bake sets, but from the looks of things, the Kay Stanley line fizzled out entirely shortly thereafter.

[Model-Craft, Inc. spent its final days in an office at 1017 W. Washington Blvd., pictured above. By the late 1950s, Plastic City Block, Inc. occupied the same building, and appears to have taken over production of Kay Stanley’s product line.]

Kay Stanley herself—again, as best we can tell—bowed out of the toy business when she sold out to Plastic Block City in the late ’50s. From there, we can trace her into the early 1960s pursuing a couple new career tracks.

In 1961, she and a business partner named Ethel Wladis were running a “make-up instruction studio” called Quinn-Cotten Ltd.—the “Cotten” part being a callback to Kay’s maiden name (“Quinn” referenced Ethel Wladis’s maiden name, Quinlisk). The company was loosely connected to the John Robert Powers chain of modeling schools, and it still had a Chicago office as late as 1964—60 East Division Street—with Kay Stanley still listed as president. In 1962, there was also a shortly-lived start-up called “Kay Stanley Enterprises,” which trained beauticians to become manufacturing technicians.

Ethel Wladis died in 1969. But as for the woman we’ve been profiling in great detail for the last several thousand words . . . we still don’t know what became of Kay Stanley. The trail goes cold in the mid 1960s, when she would have been nearing retirement age. If you have any knowledge about what she got up to next, do let us know!

[Left: Kay Stanley in the heyday of Model-Craft Inc., mid 1950s. Right: Kay (far right) and her Quinn-Cotten Ltd. business partner Ethel Wladis applying make-up to Chicago charm school students in 1961.]

Sources:

“Funeral Today for Lake Victim (Oliver M. Cotten)” – Battle Creek Enquirer, Oct 11, 1939

“White Collar Girl: Toy Manufacturer” – Chicago Tribune, May 28, 1945

“Santa Goes to Town” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 22, 1946

“Kay Stanley . . . ” – Clarion-Ledger (Jackson, MS), Nov 7, 1952

“Chicagoan Develops from Babe in Toyland to Major Success” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 20, 1952

“Remodeling Modernizes an Old House” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 15, 1953

“Toy Modeling Perfected by Lady Tycoon” – Sunday News (Lancaster, PA), Nov 29, 1953

“Get ’em Young” – Modern Packaging, November, 1953

“For a Quick, Easy Good Time, Have a Pancake Party” – Chicago Tribune, May 23, 1954

“The Inquiring Camera Girl” – Chicago Tribune, July 12, 1954

“Up and Coming Santa Clauses” – Look, October 4, 1955

“She Specializes in Pint Size Cookery for Children” – Chicago Tribune, Jan 20, 1956

“Austin Group to Learn ‘New Face’ Techniques” – Suburbanite Economist, Jan 25, 1961

“Food and Drug Unit Halts Toy Cake Mix Sales” – Lansing State Journal, Dec 14, 1961

Fun Preview of a Book Item – VintageDisneyAlice.blogspot.com

Great article