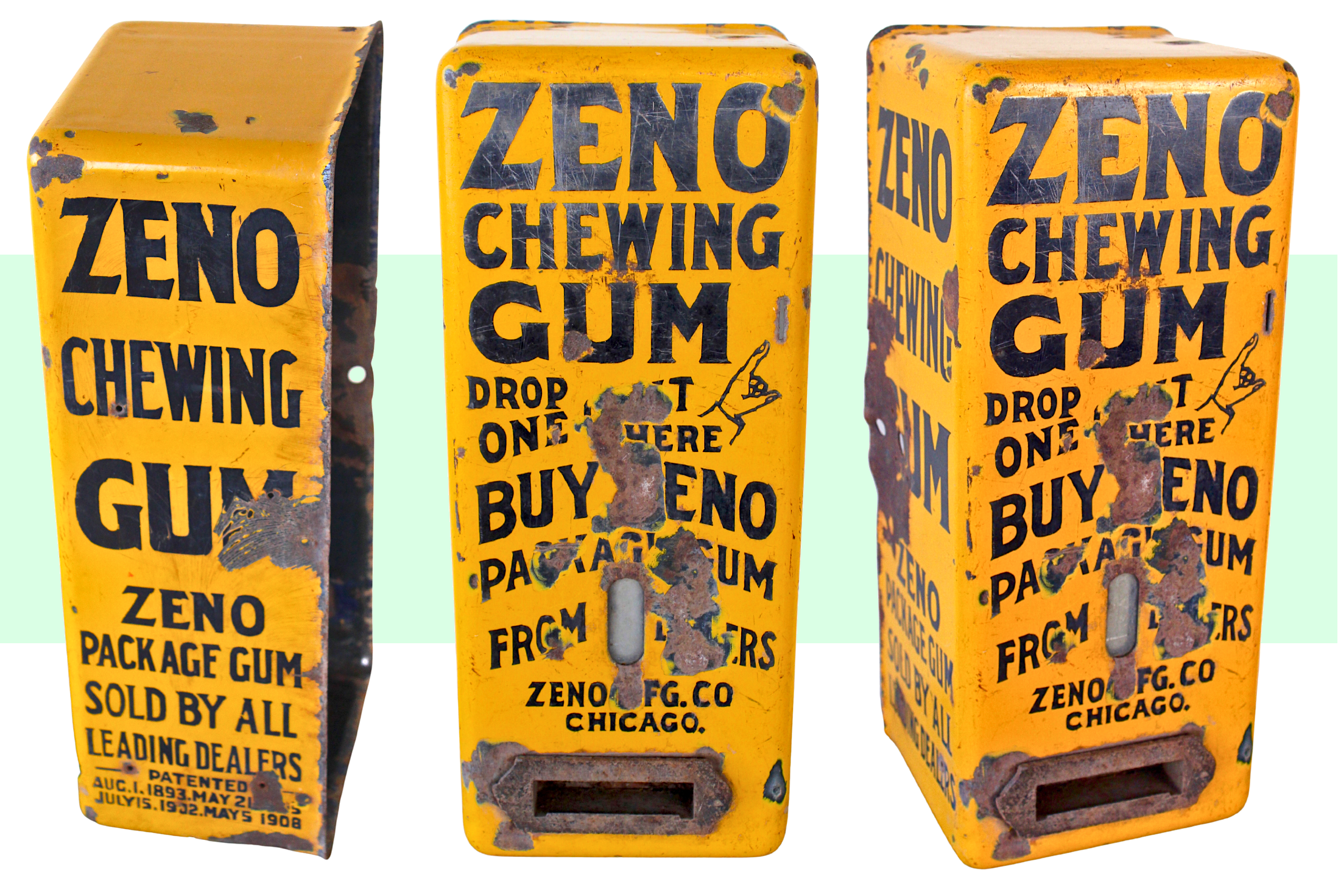

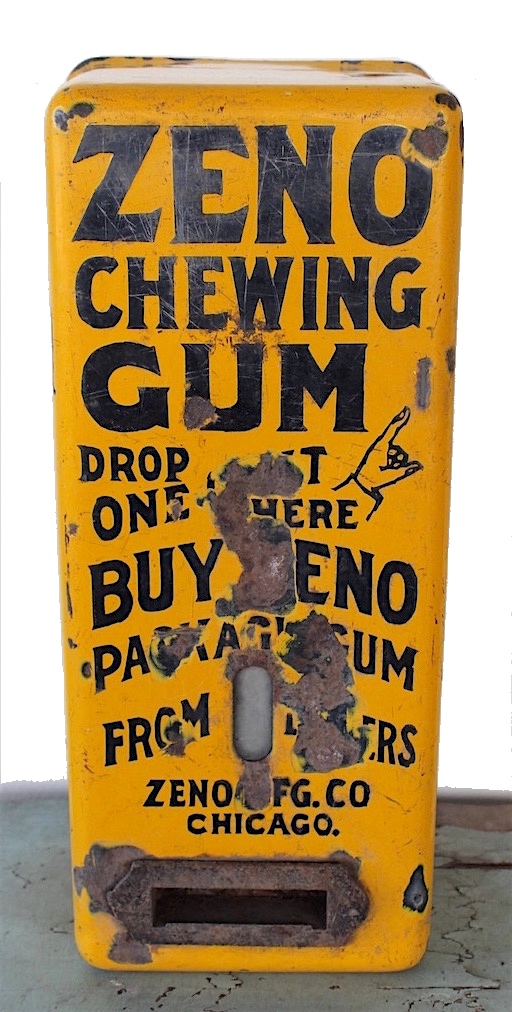

Museum Artifact: Zeno Chewing Gum Coin-Op Vending Machine, 1908

Made By: Zeno MFG Co., 150-160 W. Van Buren St., Chicago, IL [Downtown / The Loop]

It’s been more than 100 years since someone first dropped a penny into this porcelain-enameled steel vending machine, jonesing for a fresh stick of “elegant” Zeno chewing gum. By no coincidence, most awareness of the Zeno Manufacturing Company itself has long since been spat from the public consciousness and trampled over by time, slowly flattened into a proverbial dark circle in the pavement. The company’s lasting legacy—or that is to say, the only time it’s ever mentioned—is as a footnote in the story of a far grander Chicago confectionery institution: William Wrigley Jr. & Co. If you’re partial to a good prequel, however, this one ain’t half bad.

We might as well start with the aforementioned footnote. . . Back in 1892, when Mr. Wrigley was a young soap salesman newly arrived in Chicago from Philadelphia, he started giving away free sticks of gum as an enticement for would-be customers. That gum—produced by the Zeno MFG Co.— quickly proved more popular than Wrigley’s primary goods, and thus, a billion dollar partnership was born. Wrigley worked with Zeno to develop iconic brands like Juicy Fruit and Spearmint, and by 1911, he enveloped the gum business entirely under his own Wrigley Company banner.

We might as well start with the aforementioned footnote. . . Back in 1892, when Mr. Wrigley was a young soap salesman newly arrived in Chicago from Philadelphia, he started giving away free sticks of gum as an enticement for would-be customers. That gum—produced by the Zeno MFG Co.— quickly proved more popular than Wrigley’s primary goods, and thus, a billion dollar partnership was born. Wrigley worked with Zeno to develop iconic brands like Juicy Fruit and Spearmint, and by 1911, he enveloped the gum business entirely under his own Wrigley Company banner.

Generally, the story above is told in such a way that Zeno’s gum seems to just drop out of the sky into Wrigley’s lap. But sometimes, history’s most fortunate happenstances prove a bit less random when you zoom in on them.

The Zeno MFG Co. was established in Chicago roughly a year before William Wrigley, Jr. arrived, at a time when sugarized chewing gum sticks were just starting to gain traction as the all-day noshable. Compared to its small field of competitors sprouting up in the Midwest, Zeno had the distinct advantage of being a subsidiary of a much larger company—providing a source of funding that no Philadelphian with a soap cart could yet have matched.

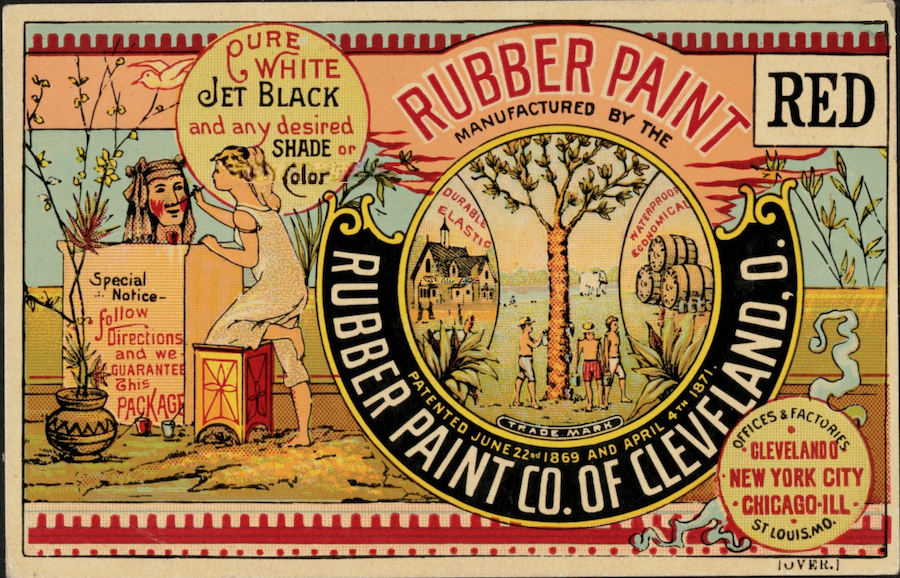

From the outset, Zeno was operated by the well established Rubber Paint Company—a Cleveland based firm that had major branch offices and factories in Chicago, New York, and St. Louis. The general manager of the Rubber Paint Co. at the time was a man named Nelson C. Brewer, and it was his eldest son—William Nelson Brewer—who is really the star of our story.

If you’re wondering why a paint company would suddenly open up a chewing gum factory, W. N. Brewer is the reason.

Zeno History, Part I: The Rubber Meets the Road

“For many years, chemists and others have experimented in mixing India Rubber with Oil, Lead, etc., in order to produce a perfectly water-proof paint, and at last, successful in the effort, have formed a chemical combination of Rubber with oil paints, which, when applied, becomes hard and elastic enough to not crack or peel from the action of the atmosphere, with a gloss equal to work finished with varnish. The Rubber Paint Company, of Cleveland, Ohio, own all the patents covering perfect combinations like the above, which is known and sold by them as ‘RUBBER PAINT.’” —Rubber Paint Co. catalog, 1880

Born in Cleveland in 1860, William N. Brewer (aka Willy) was a college dropout who somewhat reluctantly went back home to work for his dad at the Rubber Paint Company plant around the age of 20. It was a good gig at a thriving business, but Brewer was never the sort to find his contentment in mere stability. He was caught up in the wave of technological and commercial innovation redefining American industry, and he wanted to carve his own path within it.

Combining his factory training with a passion for art and design, he became something of an amateur inventor on the side, eventually collecting a few patents in the process (including one for a style of display case and another for a hat rack). While still employed by the Rubber Paint Co. in Cleveland, Brewer figured he might as well put his brain to the task of finding new uses for the resources right in front of him, as well.

So, applying some lessons from the same chemistry experiments that had produced “the perfect rubber paint,” he hatched a plan to utilize his company’s excess India rubber as the base ingredient for a line of chewing gum. Granted, he was not the pioneer of this concept—the first patent on a rubber-based chewing gum was given to another Ohioan, a dentist named William F. Semple, back in 1869. Others had fine-tuned the snack with various combinations of sugar and licorice over the years since. Still, the chewing gum industry was in its infancy, and Brewer seemed to sense that the arrow was only pointing forward (ya know, like a Spearmint).

In 1890, Brewer pitched his gum idea to the Rubber Paint Company hierarchy (which included his father), and—whether they were stoked about the plan or just motivated to give Mr. Brewer’s kid a pet project—the Zeno Manufacturing Company was born.

Early on, the decision was made to adapt part of the Rubber Paint Co.’s existing factory space in Chicago, at 160 West Van Buren Street, into Zeno’s production headquarters. Both William Brewer and his younger brother Charles helped organize and conduct sales for the business, while a man named Amaariah George Cox—longtime general manager of the Rubber Paint Company’s Chicago operations—handled its affairs.

II. Gums For Hire

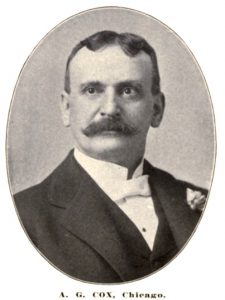

A.G. Cox (1849-1941) didn’t know much about chewing gum. A former math teacher, he’d survived the Panic of 1873 by breaking into the towing and wrecking business (whatever that meant in the pre-automobile era). He’d then parlayed that into a job in paint manufacturing, catching on with the Rubber Paint Co., first in Cleveland, then Chicago.

By 1891, Cox had gained enough power and esteem that the company board offered him the chance to buy the majority stock in the business. It took him seven months to scrounge together $50,000 for a first payment, but the deal was official—A.G. Cox was the new owner of the Rubber Paint Co. and all its subsidiaries, including that strange little animal called the Zeno MFG Co.

With all the new responsibility on his back, Cox could have cut the cord on Zeno before it got off the ground. Instead, he made it a priority, working with the Brewer brothers to build some brand recognition and a regional network of alliances. By striking deals with independent salesmen, druggists, non-competitive manufacturers, etc., Zeno was able to introduce itself to many customers as an incentive or “giveaway” product. Building a relationship with someone like William Wrigley, then, was far from an accident. It was an example of a widespread strategy reaching its best possible conclusion.

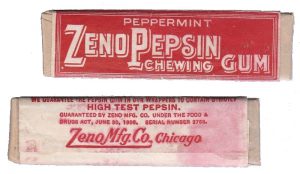

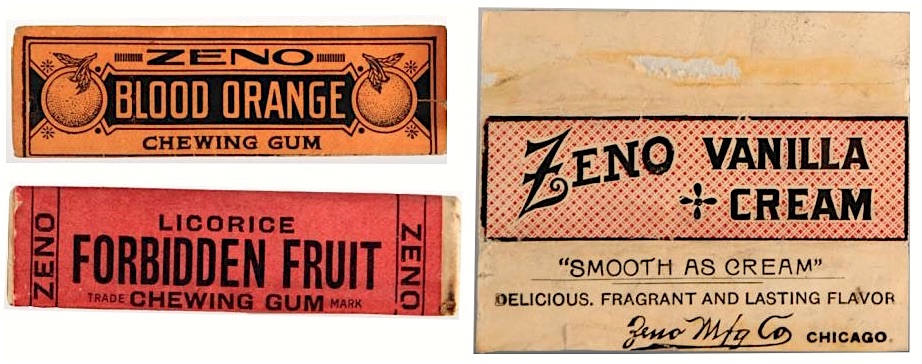

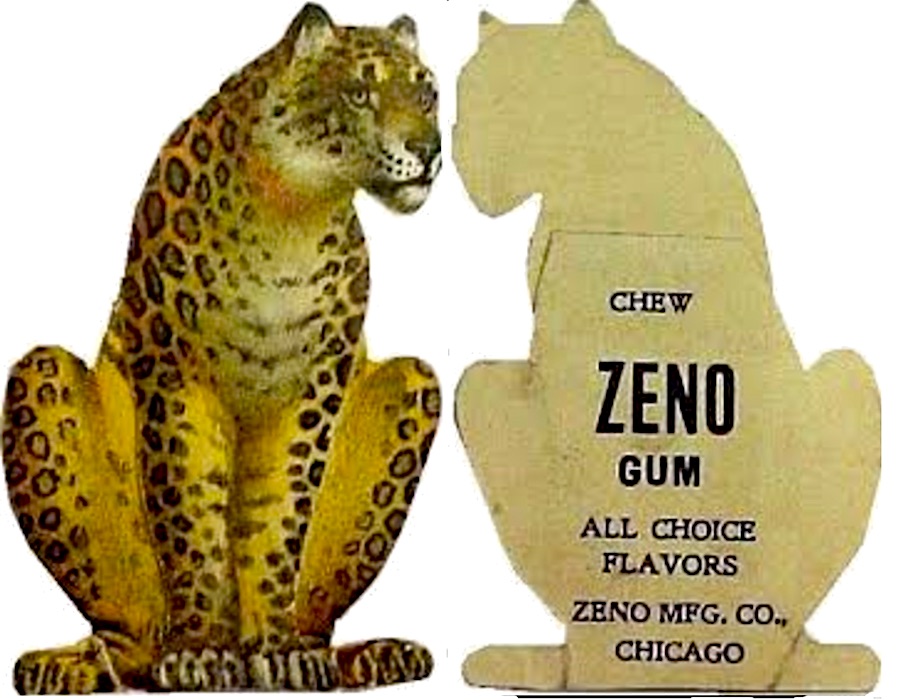

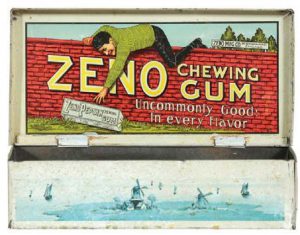

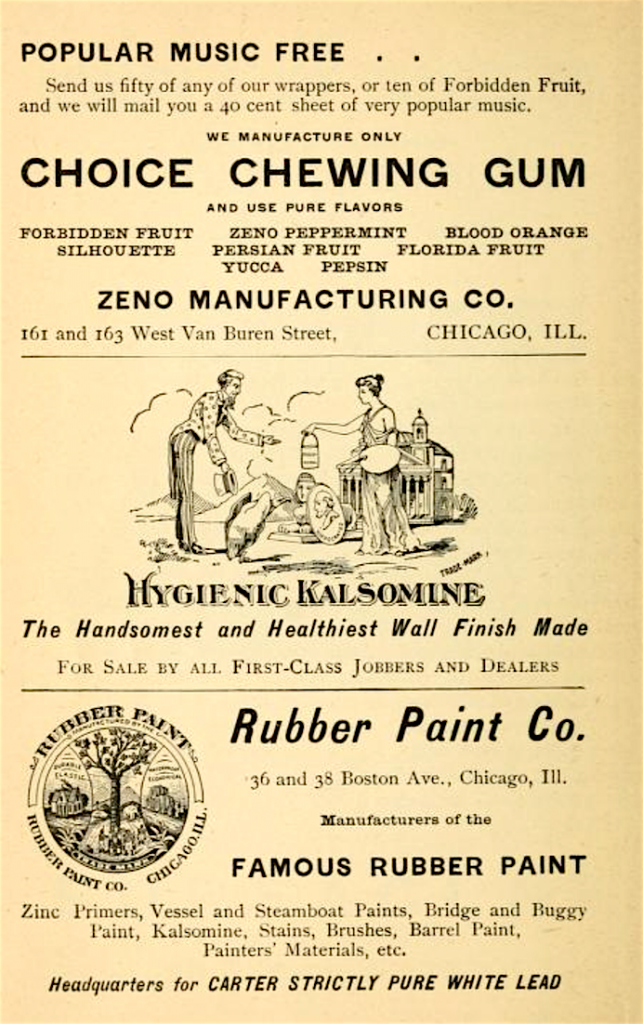

At the Columbian Exposition in 1893, Zeno gum was out in full force, often sold in fancy oak vending machines—another new novelty of the era. Flavors like “Forbidden Fruit,” “Zeno Peppermint,” and “Blood Orange” converted thousands of visitors to the new brand. Likely influenced by William Brewer’s budding lithograph design talents, the gum’s colorful wrapping left an impression, too.

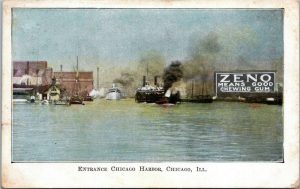

The marketing blitz was so effective that the gum ironically started coming with its own sales incentives, including a line of promotional postcards—often featuring doctored images of famous places with the Zeno logo subtly embedded into the scenery [see for example, the Zeno-fied Chicago Harbor pictured here].

In another campaign, in circulation during the World’s Fair, the company offered a musical prize for loyal gum chewers. “Send us fifty of our wrappers, or ten of Forbidden Fruit,” the ad read, “and we will mail you a 40 cent sheet of very popular music.” Not an mp3, CD or vinyl record, mind you. But a song you could look at and attempt to hum. #GloryDays

By 1895, A. G. Cox began to realize that the ceiling on his gum business might be even a bit higher than the one on rubber paint. To streamline production, he purchased a 1,500,000 acre plantation in British Honduras that produced chicle—the natural rubber of the sapodilla tree, which was the key ingredient in most of Zeno’s new recipes. He also installed a young, up-and-coming mechanical wiz named Frank B. Redington—brother-in-law of Rubber Paint Co. vice president Frank Hayes—as the superintendent of the Zeno factory.

Frank Redington, as it happened, was the son of Sanford Ink Company founder Frederick Redington and the younger brother of that firm’s presiding president, William Redington, so he was something of a pedigreed factory man—eager and ready for a challenge.

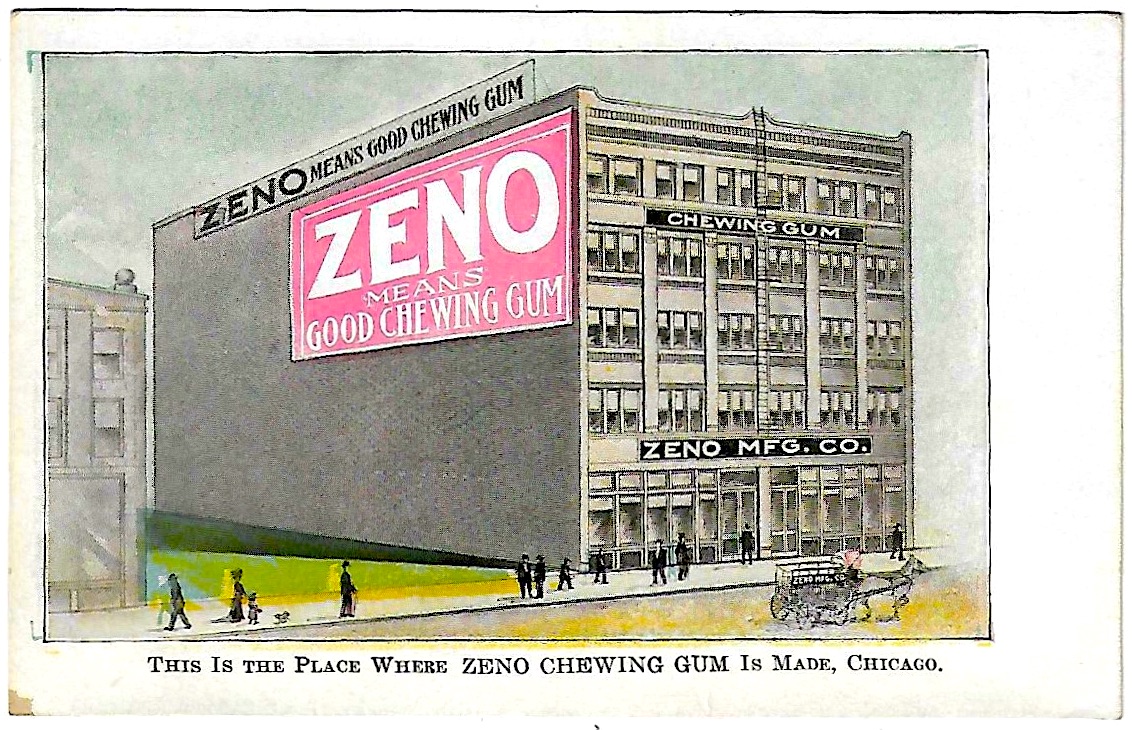

[The Zeno Gum factory at 156-160 W. Van Buren Street (735 W. Van Buren after the street number changes of 1909). The building would be erased by the time I-90 was built directly through this part of town decades later]

[The Zeno Gum factory at 156-160 W. Van Buren Street (735 W. Van Buren after the street number changes of 1909). The building would be erased by the time I-90 was built directly through this part of town decades later]

III. Inside the Zeno Factory

Aside from Redington, Cox, Charles Brewer, and the occasional visit from William Brewer (who was still based in Cleveland), the Zeno plant on Van Buren Street was manned almost entirely by women—if you’ll pardon the expression. In 1901, for example, there were 145 employees on the payroll, and 133 of them were the fairer sex. Gum production was “a rather tedious process involving much painstaking labor,” as a 1902 article in The Inglenook put it, but it didn’t involve a lot of heavy machinery or blast furnaces. Since one stick of gum would be sold at just one cent retail, hiring women—and paying them less than men, of course—would help keep production costs down and profits up.

[Women working in the former Zeno gum factory, now under the Wrigley banner, c. 1912]

[Women working in the former Zeno gum factory, now under the Wrigley banner, c. 1912]

At most gum factories, there were generally automated methods for granulating, curing, cooking, and rolling out the chicle, but it was up to the girls to break up the sticks and individually wrap and pack them—“the most tedious part of the work.”

According to a 1936 issue of Modern Packaging, Zeno’s superintendent F.B. Redington soon found “that forcing girls to work at higher speeds resulted in having to send them home from work, their fingers and thumbs sore and bleeding from wrapping sticks of gum by hand. This observation, in 1897, led to his development of the gum wrapping machine, which eliminated the hand work.”

This machine, according to the Inglenook’s firsthand account in 1902, turned “five sticks at a time into the hands of a girl whose sole duty it is to encircle the package with a rubber band and tuck it away into a fancy box. The machine has a capacity of 400 boxes a day. The average wrapping machine can grind out 140,000 sticks in a day, while 10,000 is an exceptional record for a girl working with her hands alone.”

One would love to believe that Frank Redington invented the gum wrapping machine out of a deep empathy for the plight of Zeno’s bloody-handed workers, but with demand growing exponentially in the marketplace, more efficient production was likely an equal if not greater point of interest from the members of the board.

For many years, women had been not only the primary manufacturers of chewing gum, but the targeted clientele, as well—since a man’s mouth was presumably deemed better occupied with tobacco dip and cigars. This had begun to change towards the turn of the century, however, as Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders had supposedly got hooked on the stuff in Cuba, sparking a new spike in the gummification of America.

“America is par excellence the land of the gum chewer,” a writer for the Atlanta Constitution wrote in 1901. “Soldiers and bicyclists are the chewing gum manufacturers’ best customers, and Chicago is probably the best chewing gum town on the American continent.”

I’m not sure what statistics that journalist had to back up his rankings, but if Chicago was indeed the gum capital it was purported to be, Zeno (partially through its alliance with Wrigley) had the biggest role in keeping up with that demand.

“In spite of the fact that gum is on sale most everywhere,” the Inglenook reported, “much of that consumed in Chicago is an import product. There are only two or three pretentious gum factories in the city, and at the largest of these [Zeno], which makes that sold in most of the slot machines, the daily output is 1,000,000 sticks.”

That’s less than 150 people—just about all of them women—churning out a million sticks of gum per day. Give William Wrigley all the credit you want for building his empire with great salesmanship, but Wrigley wouldn’t have become Wrigley without the crew over at the Zeno plant.

Incidentally, Frank Redington wasn’t done designing machines to improve factory efficiency. He started his own business, the F. B. Redington Company, which is also featured in the Made In Chicago Museum.

IV. “Drop One Cent Here”

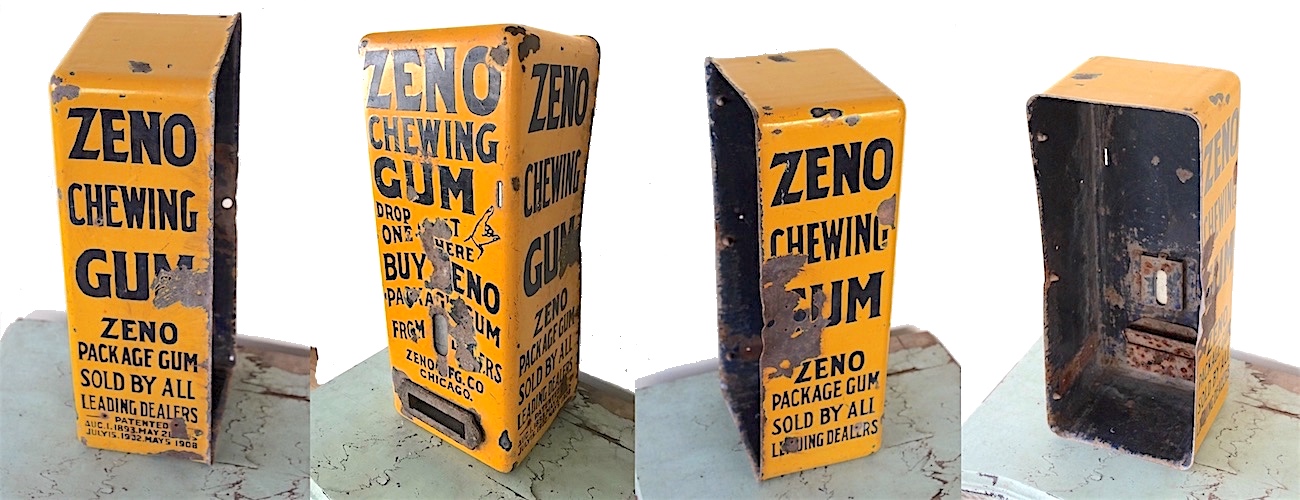

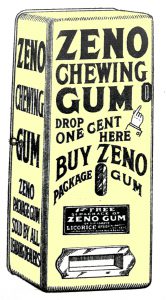

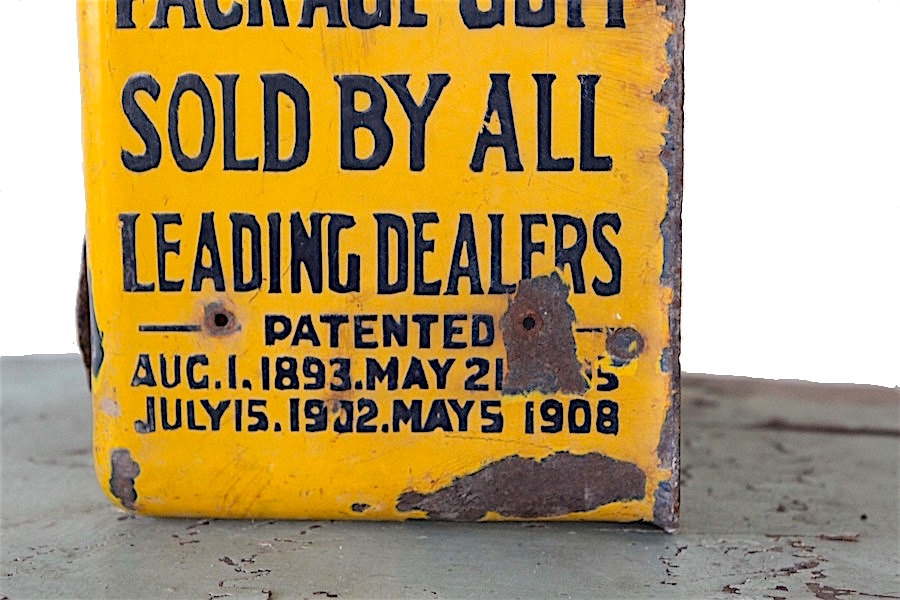

Maybe the only machine more crucial to Zeno’s success than the gum wrapping device was the magical vending machine itself, which evolved from an oak cabinet to the style in our collection, made from pressed steel with a porcelain enamel finish.

Vending machines in any form had only existed since the late 1880s, so the idea of being able to pay 1-cent for a fresh piece of delicious “Blood Orange” Zeno gum wasn’t just appealing to kids, it was a hoot for the grownups, as well. The inner clockwork mechanism of the machine (which, unfortunately, is not part of our gutted artifact) used to fascinate customers who would encounter the Zeno boxes in pharmacies, barber shops, pubs, etc. When the bright yellow boxes started appearing around 1905, they were particularly hard to miss.

Zeno offered merchants a deal: buy 12 boxes of gum (100 pieces in each) at a price of $9.50, and you’d get the countertop coin-op machine FREE. In short order, a hell of a lot of people signed up.

“The Zeno Manufacturing Company are doing active and intelligent work in placing their Automatic Chewing Gum Machine in more and more drug stores,” The Pharmaceutical Era reported in 1901. “This is a little machine which might be said to work while you sleep. It requires no particular care, except to keep filled; this done and the machine placed in a prominent and easily accessible location in or near the store, the pennies will come to it and you will be surprised to see how quickly it will pay for itself.”

As an added bonus for Zeno, many drug stores started advertising their own Zeno machines in local newspapers as a customer enticement, giving the company a priceless grass roots campaign at no cost to them.

[Newspaper ad for a North Carolina drug store, 1898]

[Newspaper ad for a North Carolina drug store, 1898]

In 1905, Chicago’s White City Amusement Park used the allure of shiny new Zeno gum machines as the focus of an advertisement in their own magazine, making it sound like chewing gum was even more popular than carnival rides.

“Following the policy of giving its visitors the highest quality of everything that can possibly be obtained, White City has arranged to install the Zeno Gum Vending machines exclusively at the grounds. The Zeno Gum machines were used exclusively at the St. Louis Exposition and the popularity they aroused there raised the Zeno machines to the first place among gum vending machines.

“The Zeno Manufacturing Company has completed a new machine, which is said to be the most perfect gum vending machine ever devised. The machine is most attractive in appearance and is especially constructed to meet with the demands of White City visitors. The color scheme of the new machine is yellow and black, which is worked together in a most pleasing combination. Hundreds of these machines will be scattered all through White City.”

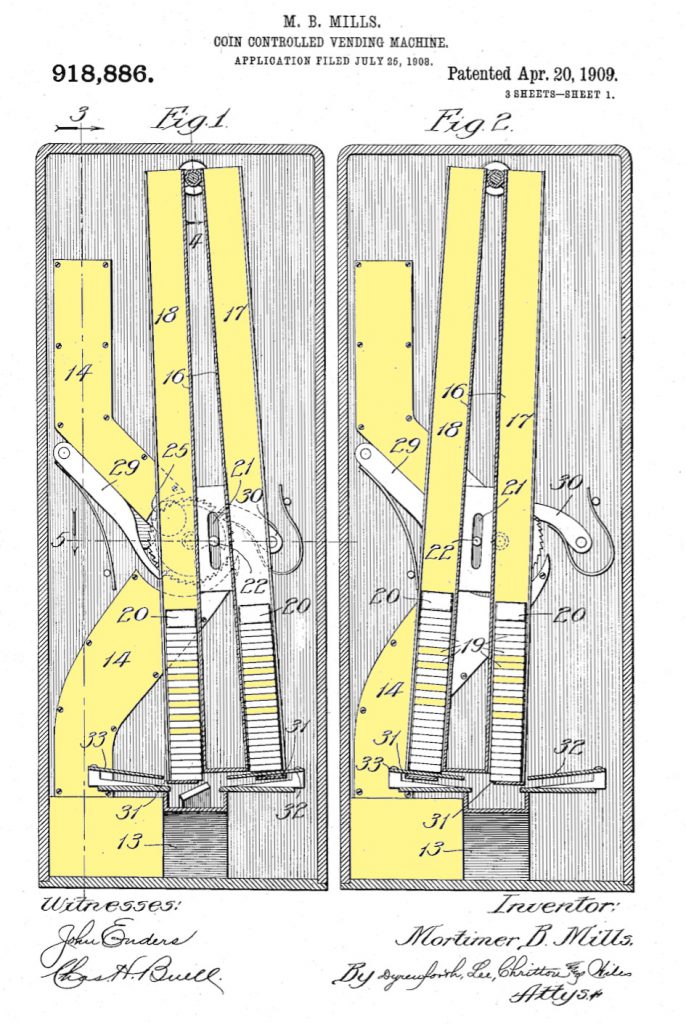

As late as 1916, when Wrigley had taken over full control over the Zeno brand, our yellow vending machine (measuring 17″ tall x 7″ wide x 5.75″ deep) was still in production, selling to dealers for $12. Wrigley called the unit “mechanically perfect” in its Red Book Catalog that year, noting that it “refuses slugs” and “is strictly automatic, as there are no plungers or levers to push. It is only necessary to drop a penny in the slot and the Machine delivers the goods.”

[Patent image for the internal mechanics of the Zeno vending machine in our museum collection]

V. Six Degrees of Willy Brewer

Interestingly enough, William Brewer’s younger brother Charles—a longtime Zeno salesman—wound up using his experience peddling coin-op vending machines to establish a business of his own, the Chas. A. Brewer & Sons Company. From the 1910s into the 1940s, Brewer & Sons would be Chicago’s biggest manufacturer of “punch boards”—a type of drug-store lottery game that sold by the millions (and also became an infamous tool of the mafia for swindling desperate gamblers). We have a classic 1939 Brewer punch board as part of the Made In Chicago collection.

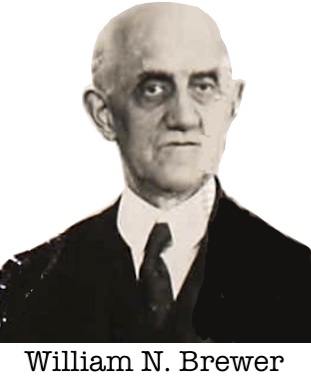

In fact, just about everyone in the orbit of William N. Brewer [pictured here in his later years] seemed to find success in avenues well beyond the walls of the Zeno MFG Co. The rubber gum pioneer was essentially the Kevin Bacon of the 1900’s Midwestern industrial scene— no more than six degrees separated from everything and everyone. This was in no small part a consequence of his own undying ambition and pursuit of new prospects in a wide array of fields.

As far back as 1892, when Zeno was just getting off the ground, W. N. Brewer was simultaneously working as a representative for the Krehbiel Palace Car Company—a Cleveland business aimed at challenging the famous Pullman railway coach empire. Interestingly, a Chicago wing of the Krehbiel company was incorporated in 1893, with F.B. Redington as one of the incorporators. It’s all connected, man!

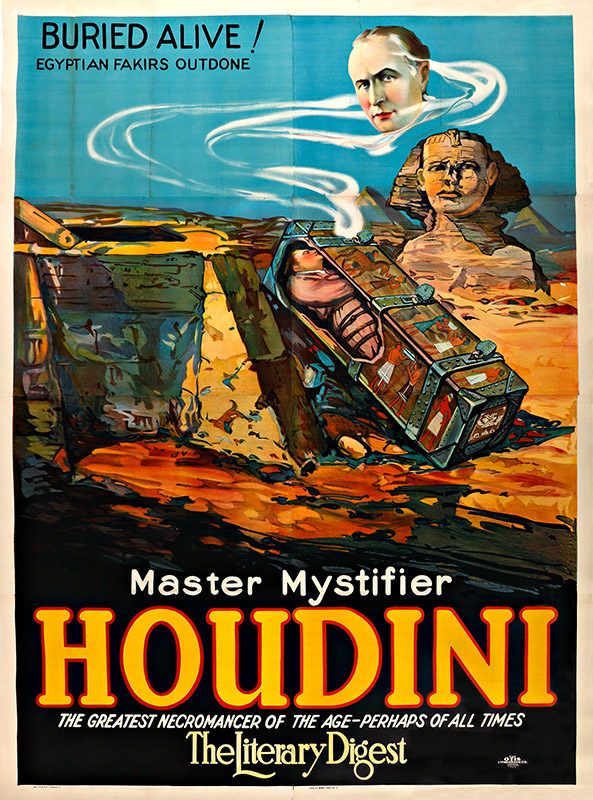

Along with established ties to the Rubber Paint Company, Zeno, Wrigley, Sanford Ink, F. B. Redington & Co., Krehbiel, and his brother’s punch board business, William Brewer also founded the Otis Lithograph Company back in Cleveland in 1903—putting his design chops to work making promotional posters for magicians like Harry Houdini and eventually the silent film industry, including Warner Brothers and Columbia Pictures. William was even cited in a 1917 lawsuit by Charlie Chaplin—then the most famous man in the world—for producing posters of Chaplin films without the star’s consent after he’d left Chicago’s Essanay Studios.

[Vintage Houdini poster designed by W. N. Brewer’s Otis Lithograph Co.]

VI. Conflagrations

The beginning of the end of for the Zeno era came in 1905, when a severe fire destroyed much of the Rubber Paint Co. offices and part of the four-story Zeno plant on West Van Buren Street. The company had effectively rebuilt by 1907, but a second tragedy that year—a Cleveland automobile crash that killed Rubber Paint’s founder Nelson Brewer and his wife Caroline (the parents of William and Charles Brewer)—led to more permanent changes.

A.G. Cox, recognizing that his future now looked rosier in the gum industry, sold the Rubber Paint Co. to a Chicago competitor (Adams & Etling Co.), and re-organized the Zeno MFG Co. as its own separate entity, with Cox himself as general manager. By this point, Wrigley gum had become the most popular brand in the country, and as the manufacturer of that brand, Zeno was quite profitable—but also uncomfortably dependent on the William Wrigley marketing machine.

In 1911, the lurking inevitability finally came to pass. Wrigley bought out the manufacturing end of his business, merging Zeno into the Wrigley Company, and effectively discontinuing any proliferation of non-Wrigley gum brands. A giant modern plant at 35th and Ashland became the central Wrigley factory, and the name Zeno was left to its obligatory footnote status.

A.G. Cox stayed on as Wrigley’s vice president for a while, with another Zeno veteran, Orlando Buck, serving as general manager. Meanwhile, F. B. Redington found success manufacturing printing press counter devices, Charles Brewer became the punchboard king, and William Brewer focused his energy on Cleveland real estate and the Otis Lithograph business, which expanded with offices in New York, Pittsburgh and Chicago (in the Marquette Building).

When W. N. Brewer died in 1924 at the age of 64, there was an obituary written for him in the bulletin of Williams College in Massachusetts—identifying him, first and foremost, as a NON-GRADUATE. “He entered Williams College with the class of 1882, but did not remain to graduate,” it said. “For several years he was engaged in the paint industry, after which he became interested in the sleeping-car business. Finally he gave his entire time to The Otis Lithograph Company, his last organization and one of the largest of its kind, of which he was president at the time of his death. He is survived by his wife, three daughters, and one son.”

There was no mention of the fact that William Brewer, in no small way, had helped start the business that became the largest chewing gum company on the planet—the engine behind the celebrity tycoon that was William Wrigley. His greatest legacy, through some cruel injustice, didn’t even earn a footnote.

SOURCES

“Coin-controlled vending-machine” – US patent 918886 A

Chewing Gum in America, 1850-1920: The Rise of an Industry, by Kerry Segrave

Modern Packaging, Vol. 10, 1936

Wrigley Red Book Catalog, 1916

“Suit Demands Fortune” – Motography, Vol 18, No. 22, 1917

“How Chewing Gum Is Made” – The Inglenook, Brethren Publishing House, Elgin, IL, 1902

“To Gum Chewers,” The White City Magazine, 1905

Annual Report of the Factory Inspector of Illinois: 1901-1902

“Zeno Chewing Gum” – Meyer Brothers Druggist, Vol. 26, Issue 10, 1905

Rubber Paint Company catalog, 1880

“Revolution in Car Construction: Three Palace Cars That are to Supersede the Pullmans” – The Daily Review, Decatur, IL, Oct 4, 1892

“William N. Brewer” – A History of Cleveland, Ohio: Biographical, Vol II, by Samuel Peter Orth, 1910

“Zeno Gum Machine,” Western Illinois Museum

“The Road to Success: A Sketch of Charles L. Barr, Head of F. B. Redington Company,” by Philip Hampson, 1953

“Amariah George Cox,” The Book of Chicagoans, a Biographical Dictionary, Vol. 2, 1911

“History of the Angie W. Cox Public Library” by Thomas A. Reinbeck & Steve Thompson, Pardeeville Library

“Otis Litho” – LearnAboutMoviePosters.com

Williams College Bulletin, Alumni Obituary Record, 1924

I have a Zeno machine in excellent condition with working mechanism (the spring is broken) but the penny will still make all the gears work. I found the in the late 60’s in an old store attic my father had purchased in Putnamville Vt.

My great, great grandfather was Orlando J Buck, the general manager of Zeno, then Vice President of Wrigley after Zeno was absorbed by the Wrigley company.

Chris: I believe your g-grandfather gave my grandfather a job at the Wrigley plant where he worked for the next 29 years. According to the family story, my grandfather Bob Glennie had lost his architectural job in 1932 and eventually was reduced to to trying to sell Hoover vacuum cleaners door to door. He made a sales call in Beverly in November 1933 to a manager at Wrigley’s, who didn’t buy the vacuum cleaner but offer Bob a job once he learned that Bob’s father was the late George Glennie who had been a manager for Wrigley’s (and Zeno) before he passed away in 1923. Bob retired as a purchasing agent in 1962, said to be “the most loved man at Wrigley’s”.

John….. what an amazing story!

Like you, we have many family stories from those times describing my great-great grandfather. I often wondered how many stories were true, or

if some were ‘inflated ‘. We were always told that Orlando was a main character in the Wrigley deal, going from Zeno….. then to Wrigely. I even found a patent that Orlando received for a ‘newly’ developed gum, which switched the main ingredient from chicle, to asphalt!

It was also amazing to learn when I was younger that Wrigley wasn’t really a ‘gum guy’, but just a great salesperson.

It’s so cool to learn Orlando was able to do what he did for your great grandfather. If Orlando gave him a job offer from a sales pitch for a vaccum…. your great grandad must have been amazing! Do you know what he ended up doing for Zeno/Wrigley? I’m sure he went on to be a major part of helping Wrigley get off the ground.

One story that floated around the family was that my great, great grandad…. living mostly in Chicago, needed a vacation spot. Wrigley had apparently bought an ISLAND off of the coast of California (reported as Catalina Island, although I haven’t verified that), and Orlando wanted a place for his own. So, Orlando ended up buying lots of land in the North Woods of Wisconsin….. turning it into the wonderful playland known as Thunder Mountain Ranch. Having around 7500 acres, it’s an amazing display of Orlando’s passion for the outdoors, and sports(ranch has a 9 hole golf course). He did that in 1901, and it’s still going strong as the ‘family retreat’.

Thanks for sharing ‘brother’!

i have a metal box with zeno

chewing gum

all choice flavor

on inside cover

if interested it may lock

We also have one of those.