Museum Artifacts: Fidelitone Master and Supreme Phonograph Needles and All-Groove Needle Counter Display, 1950s

Made By: Permo, Inc. / Fidelitone, Inc., 6415 N. Ravenswood Ave., Chicago, IL [Rogers Park]

Still in business today and headquartered just an hour north of Chicago in the small town of Wauconda, Illinois (Wauconda Forever!), Fidelitone Inc. is technically the same company that Arthur J. Olsen started way back in 1929, though he certainly wouldn’t recognize it.

When Olsen died in 1951, his thriving Rogers Park enterprise was known as Permo Incorporated, and “Fidelitone” was merely a subsidiary division—a brand name for its popular line of durable phonograph needles. That was the central crux of the business back then—researching, manufacturing, and selling the tiny accessories that made spinning records sing. By 1958, the company officially changed its corporate identity to Fidelitone, Inc., acknowledging its continued focus within the industry of turntable and jukebox styluses. It wasn’t until new tech and foreign competition rolled in during the ‘60s, ’70s and ‘80s that things took an unusual detour, resulting in Fidelitone’s current standing as a major logistics, shipping, and supply chain management business—employing more than 600 workers around the world.

When Olsen died in 1951, his thriving Rogers Park enterprise was known as Permo Incorporated, and “Fidelitone” was merely a subsidiary division—a brand name for its popular line of durable phonograph needles. That was the central crux of the business back then—researching, manufacturing, and selling the tiny accessories that made spinning records sing. By 1958, the company officially changed its corporate identity to Fidelitone, Inc., acknowledging its continued focus within the industry of turntable and jukebox styluses. It wasn’t until new tech and foreign competition rolled in during the ‘60s, ’70s and ‘80s that things took an unusual detour, resulting in Fidelitone’s current standing as a major logistics, shipping, and supply chain management business—employing more than 600 workers around the world.

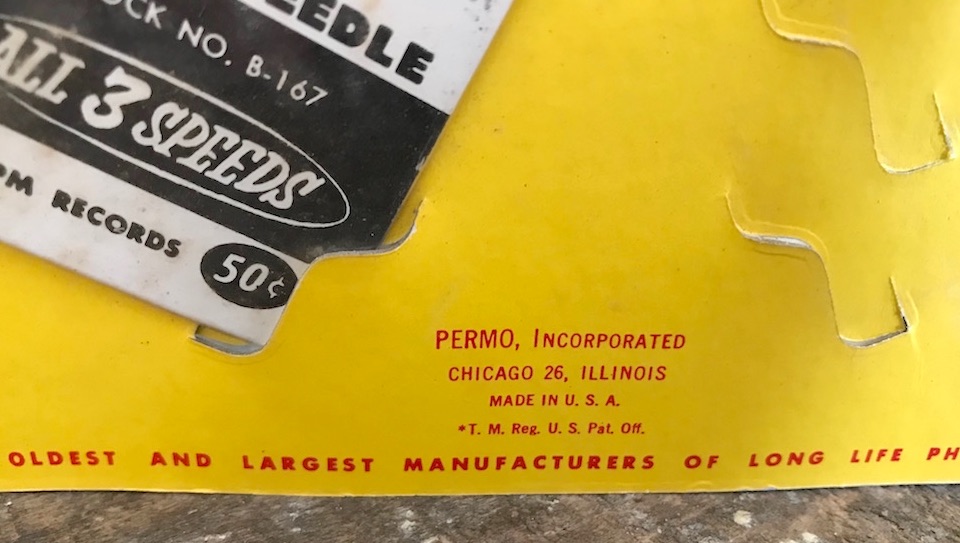

Obviously, clinging to the title of “World’s Oldest and Largest Manufacturers of Long Life Phonograph Needles” wouldn’t have played out too well in the cassette, CD, and MP3 generations anyway, so kudos to the company for contorting its whole business model to fit the modern era. As for why the “Fidelitone” name has persisted, however, that’s more of a sentimental thing.

“Our family has an emotional attachment to the name, even though it has no logical connection to our business now,” current Fidelitone CEO Craig Hudson told Family Business magazine in 2010. Hudson’s father, Douglas F. Hudson, was Art Olsen’s brother-in-law, and served as the company’s president for many years. “My father used to say Fidelitone was a lucky name, and we wanted to keep it.”

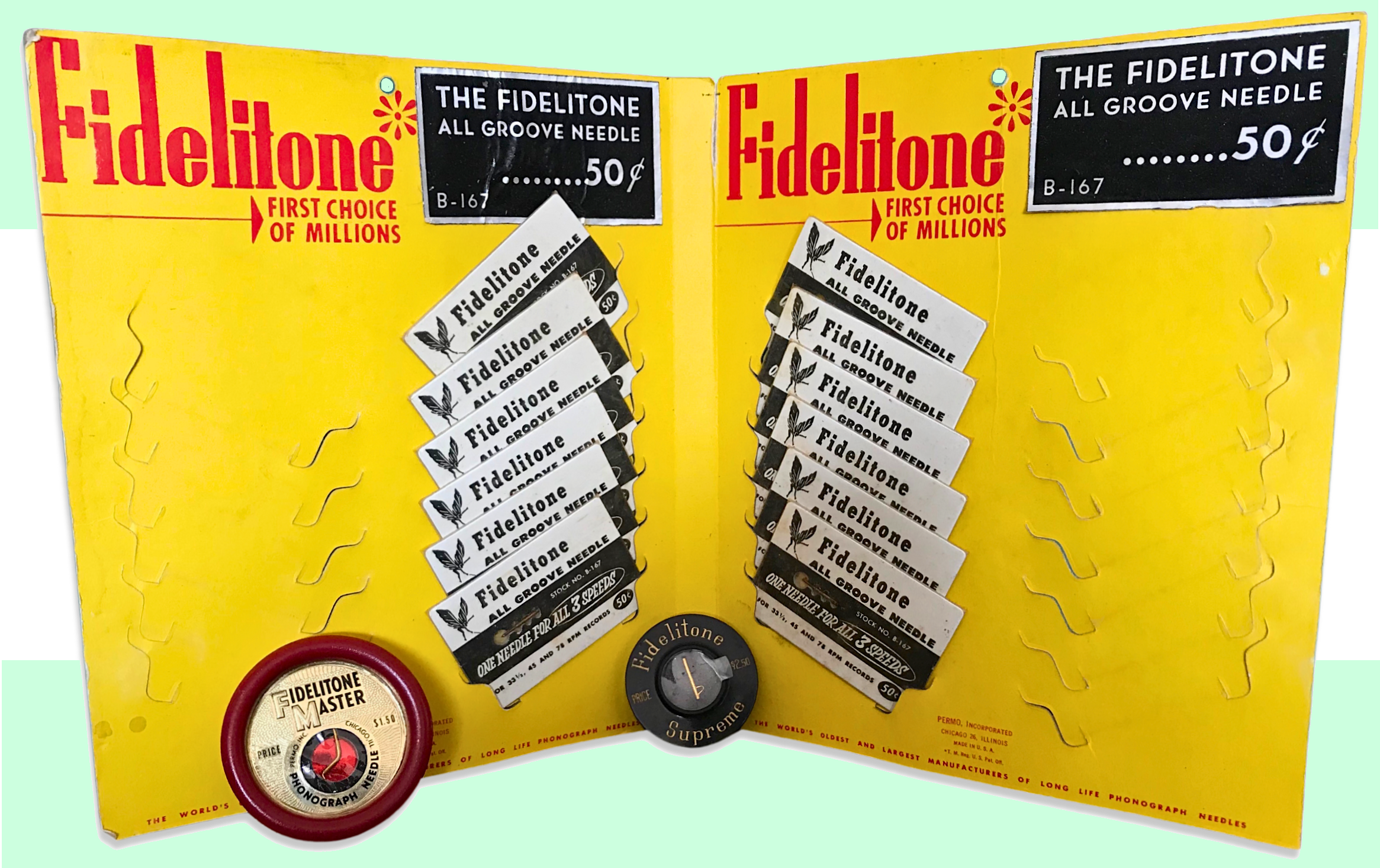

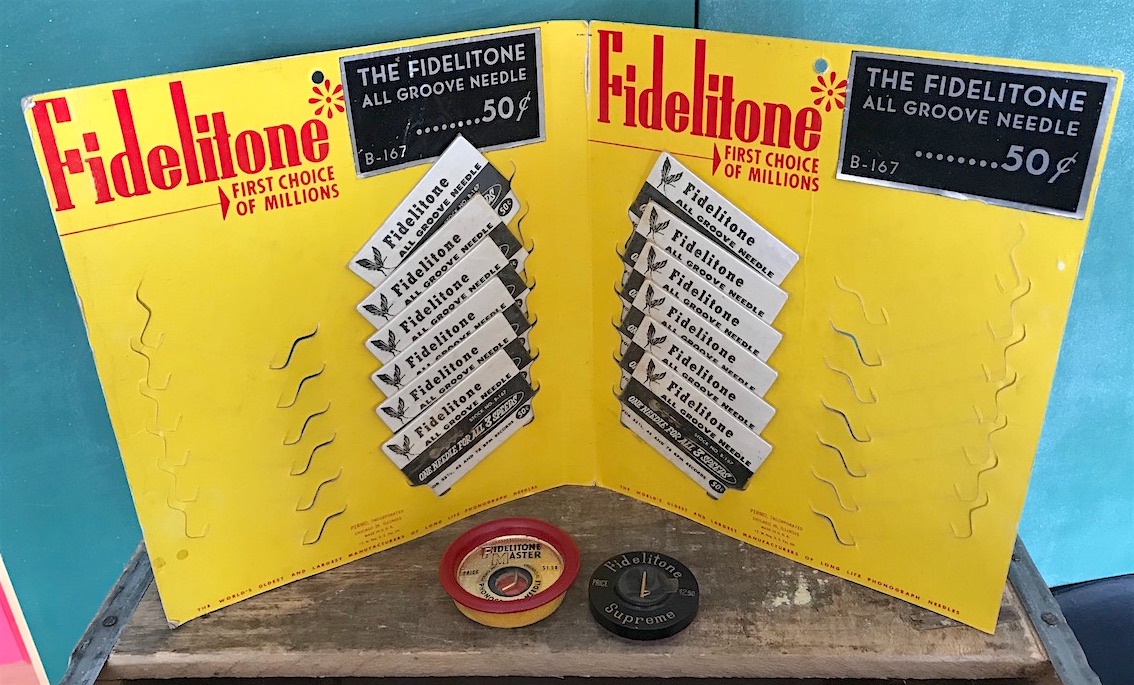

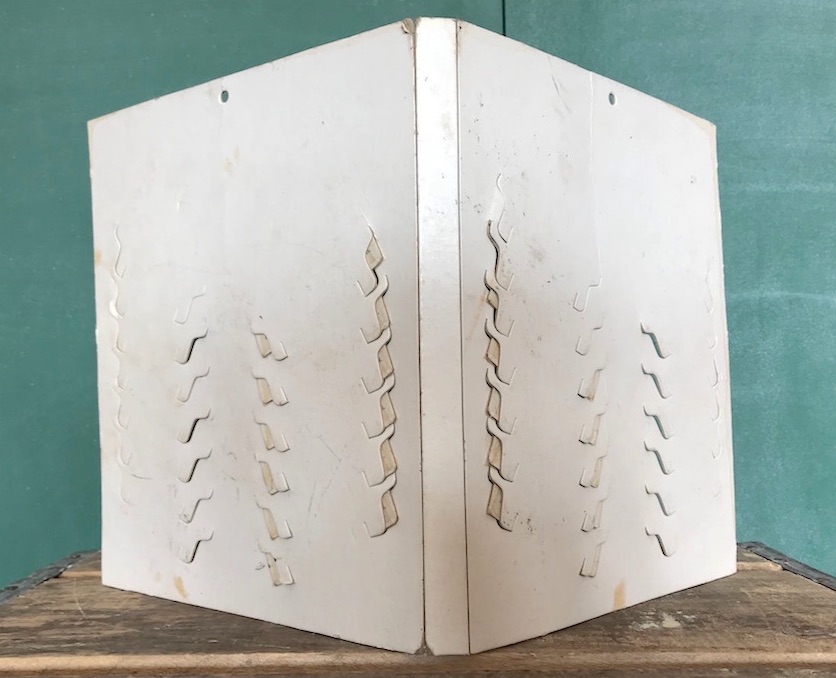

[Our museum collection includes a 1950s Fidelitone “All Groove” counter display set and these earlier 1940s Fidelitone Master and Fidelitone Supreme needles]

[Our museum collection includes a 1950s Fidelitone “All Groove” counter display set and these earlier 1940s Fidelitone Master and Fidelitone Supreme needles]

History of Permo Inc. and Fidelitone, Part I: “Art” Imitating Life

Arthur J. Olsen (born 1896, Milwaukee, Wisconsin) was a man with considerable time on his hands—time earned the hard way. Serving in the Marines during World War I, he’d suffered serious wounds in combat, earning him an eventual Purple Heart, but in the more immediate aftermath, a six-year stint in a convalescent hospital. It took seven surgeries to get him walking again, and he did so with a limp the rest of his days. It was during those initial long, slow years of recovery in the 1920s, though, that Olsen happened upon his life’s work.

With little else to occupy his mind in the hospital, he’d taken great joy in the relatively new technology of the disc-record gramophone and the miniature concerts it brought to his bedside. I’m not sure if he was a jazz daddio, a ragtime fella, or an opera snob, but he was—by all accounts—a “music lover” of some sort, and the record player was his new best friend. The same could not be said, however, for a certain component of said record player—the ever-vital but persnickety phonograph needle.

With little else to occupy his mind in the hospital, he’d taken great joy in the relatively new technology of the disc-record gramophone and the miniature concerts it brought to his bedside. I’m not sure if he was a jazz daddio, a ragtime fella, or an opera snob, but he was—by all accounts—a “music lover” of some sort, and the record player was his new best friend. The same could not be said, however, for a certain component of said record player—the ever-vital but persnickety phonograph needle.

Back in the Roaring ‘20s, many a swinging party was brought to a literal screeching halt by the failings of archaic needle technology. Early styluses—particularly on popular Victrola talking machines—routinely wore out, broke, and scratched up records. As such, new needles had to be installed constantly to ensure a quality play and the protection of vulnerable shellac disks.

For a war veteran in traction, this issue was all the more frustrating. And so, Art Olsen put his mind to a solution. The Permo Products Corporation was born.

II. Wizard of Osmium

According to the “History” page on the current Fidelitone corporate website, “When founder Arthur Olsen realized the need for a longer-lasting needle, FIDELITONE developed the Diamond Stylus, a high-quality needle that is now a featured collector’s item.”

That narrative, however, doesn’t seem to track. For one thing, diamond needles had already been available for years, including on some early Edison players. And while they were certainly “high quality,” they were also expensive, impractical to manufacture, and rough on record grooves (at least in the pre-vinyl era). For his own inspiration, Olsen had actually looked to a very different substance.

In the 1920s, fountain pen manufacturers like the Sheaffer Pen Co. and the Wahl Company started using precious metal alloys (osmium, iridium, etc.) to make pen nubs for their “Lifetime” and “Eversharp” brands, respectively [see photo: a Wahl Eversharp advertisement from 1927]. The same materials, Olsen figured, could be applied to a certain other precision implement.

In the 1920s, fountain pen manufacturers like the Sheaffer Pen Co. and the Wahl Company started using precious metal alloys (osmium, iridium, etc.) to make pen nubs for their “Lifetime” and “Eversharp” brands, respectively [see photo: a Wahl Eversharp advertisement from 1927]. The same materials, Olsen figured, could be applied to a certain other precision implement.

“This started Olsen on his plans to produce a ‘long-life’ record needle,” Cash Box magazine recounted in a 1951 profile. “After many experiments a needle was finally produced, which not only lasted through thousands of plays, but reproduced the sound of the record in true tone.”

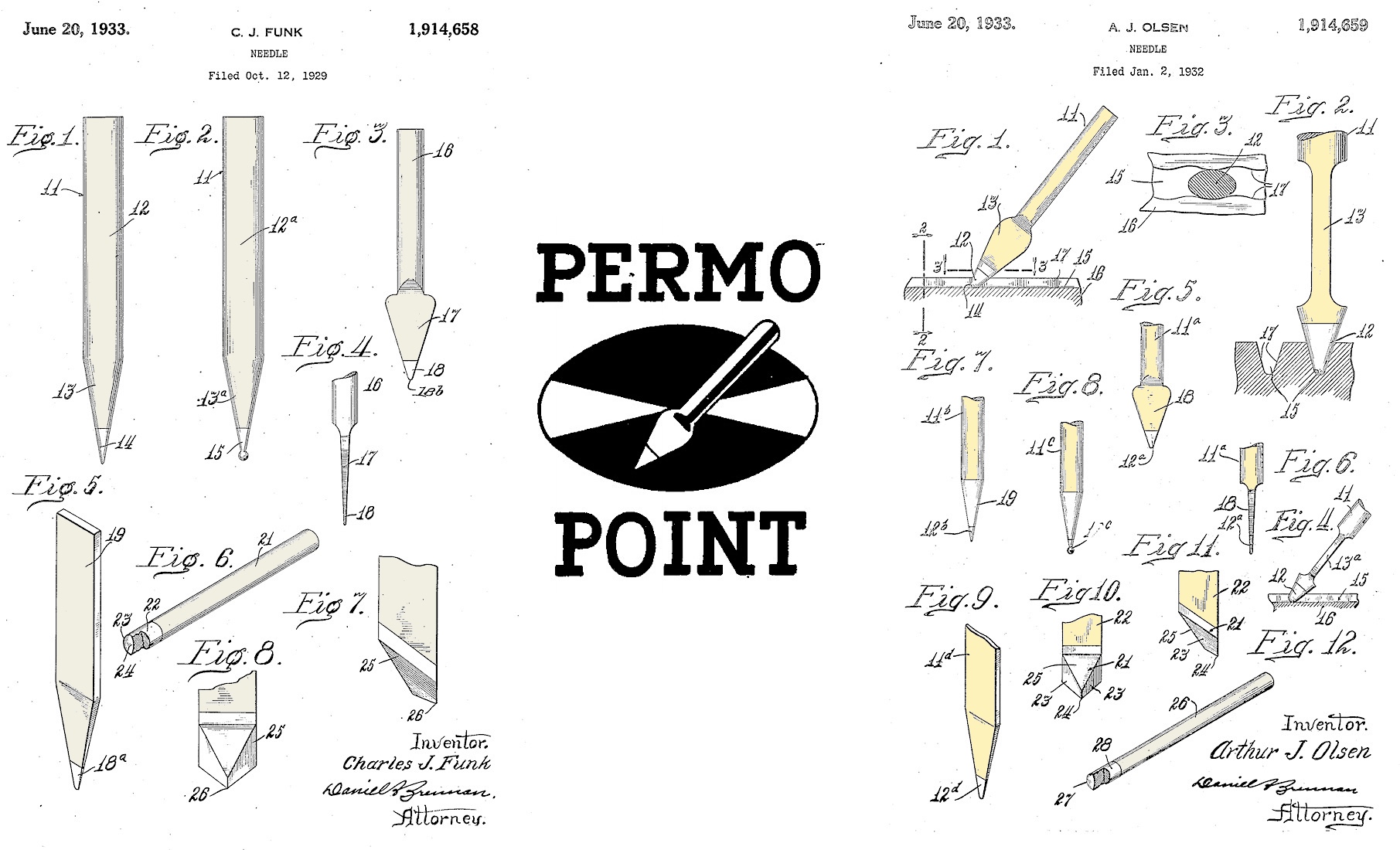

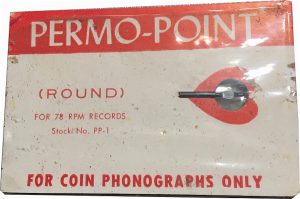

The first “Permo Point” needle, introduced in 1929, was actually co-developed with a Chicago inventor named Charles J. Funk—a young Hungarian immigrant whom Olsen had plucked straight from the Wahl Company’s engineering team. In an updated patent application Olsen penned two years later, he described his new breed of stylus as “having an improved alloy metal, wear-resisting, record-engaging portion . . . which is not susceptible-to rust, corrosion, or misshaping. . . . Material wear of the needle is practically eliminated and the volume of sound reproduced or recorded thereby remains substantially constant during continued use.”

[Permo’s first needle patents were approved in 1933, and included Charles Funk’s 1929 design as well as Arthur Olsen’s 1932 model]

[Permo’s first needle patents were approved in 1933, and included Charles Funk’s 1929 design as well as Arthur Olsen’s 1932 model]

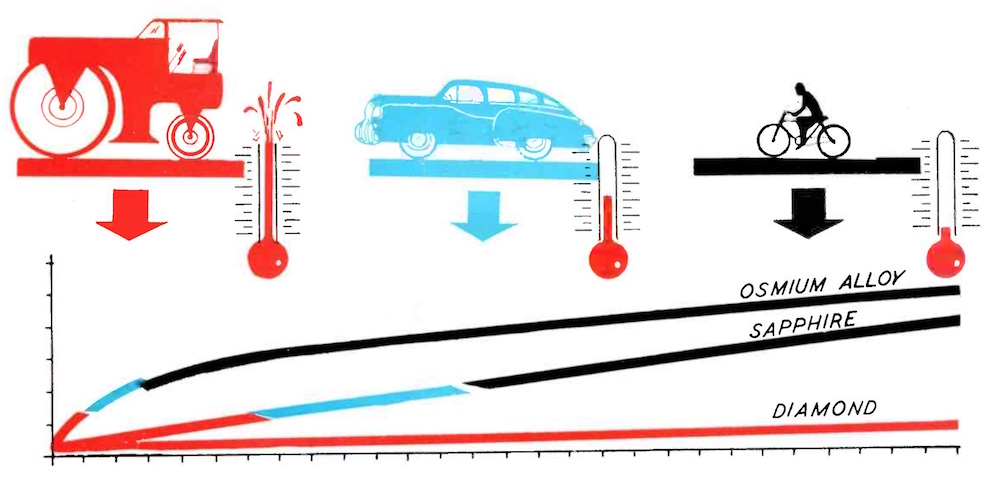

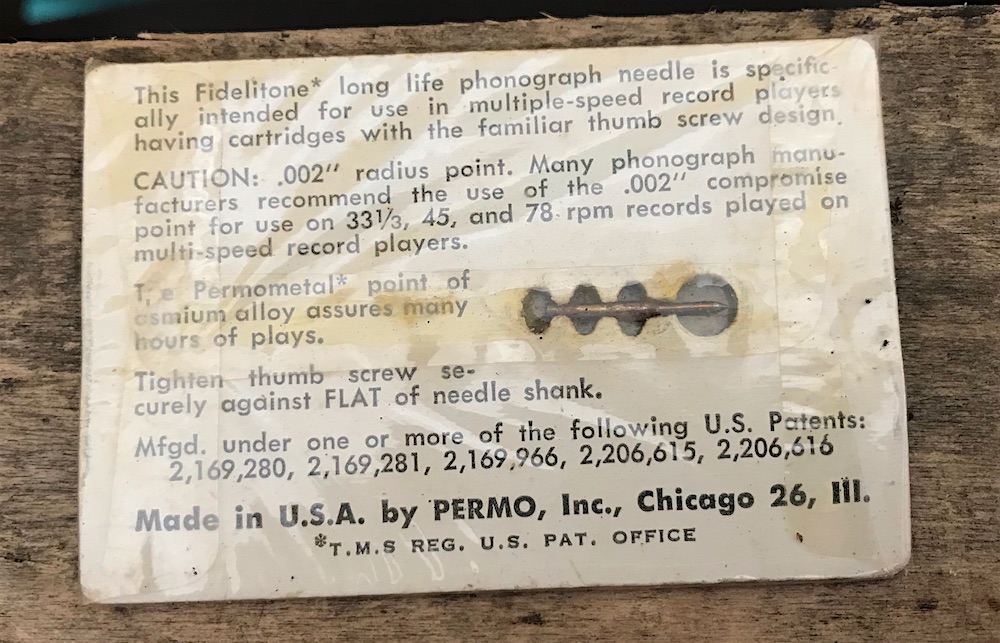

Olsen utilized a special osmium alloy (later to be known, unofficially, as “Permometal”) to create what he felt was the perfect, custom-made stylus tip. Many years later, Permo / Fidelitone would fully embrace the production of both diamond and sapphire needles, as well, but as late as 1950—in stark contrast to Fidelitone’s current corporate account—Art Olsen was still arguing for the advantages of his beloved osmium alloy over those more popular gems.

“The conflicting conditions under which the needle tip must function and the very hardness and wear-resistance of the diamond creates a paradox which limits its practical public usage,” he wrote in an article for the Broadcast Engineers Journal, also noting that a “sapphire point, riding in the groove in which loosened crystal fragments have become deposited, accelerates both needle and groove wear.”

“A unique quality of phonograph needle points made of osmium alloys,” Olsen offered as a contrast, “is that they wear-in rapidly and wear-out slowly. The quick wear-in increases the area of contact [important for high fidelity sound] and reduces unit pressure and temperature. The gradual wear-out extends over a very long period of record plays, resulting in prolonged record and needle life.”

[A graph from Art Olsen’s 1950 article in The Broadcast Engineers Journal “symbolically portrays the relative effects of high unit pressure and temperature upon the diamond, the sapphire, and the osmium alloys. The sooner the ‘steam roller’ and ‘automobile’ unit pressures are reduced the better it is for the life of both the record and the needle.”]

[A graph from Art Olsen’s 1950 article in The Broadcast Engineers Journal “symbolically portrays the relative effects of high unit pressure and temperature upon the diamond, the sapphire, and the osmium alloys. The sooner the ‘steam roller’ and ‘automobile’ unit pressures are reduced the better it is for the life of both the record and the needle.”]

You could disagree with Olsen’s assertions, maybe, but there was no doubt that the boss took his science seriously. In the mid 1930s, when the Permo Products Corp. moved from its first factory space (4311 N. Ravenswood Ave.) up the road to a much larger facility at 6415 N. Ravenswood in Rogers Park, Olsen invested big bucks equipping the facility with a state-of-the-art metallurgy lab, plus skilled experts to run it. In an industry now liberated from the recently deceased Thomas Edison, the next small innovation could make one company rich and put a bunch of others out of business. Olsen wanted to be sure he was well positioned for the former camp.

Industry schmoozing, of course, was a big requirement, too. So, joined by his younger brother Ray and a baby-faced sales manager named Sherman Pate (fresh out of Northwestern), Olsen tirelessly worked the nation’s convention circuit, glad-handing with suit-wearing reps from the big record companies and the makers of coin-operated phonographs, soon to be better known as “jukeboxes.” The Permo Products Corporation, in just a few years time, had the ears of the entire music business.

[The former Permo Inc. / Fidelitone complex at 6415-6433 North Ravenswood Ave. in Rogers Park, home to the company from the mid 1930s to the mid 1970s. The northernmost portion of the plant (pictured on the left above) had previously been one of the first homes of the Zenith Radio Corp in the 1920s, and is currently home to the Chicago Industrial Arts & Design Center.]

[Ad from a 1946 issue of the Tribune, seeking “girls and women” from around the Rogers Park neighborhood for “light, clean factory work” at the Permo plant]

III. Small in Size, But Large in Function

Lest it be overlooked, Permo Inc. began at the dawn of the Great Depression and grew during its darkest years—no small task. When you compare the challenge to, say, two years on a battlefield or six more in a hospital bed, however, you can see why Art Olsen didn’t complain much.

In the February 1937 issue of Automatic Age, an article titled “Small in Size, But Large in Function” paid considerable kudos to the Permo Point phonograph needle as a new leader in the coin-op trade.

“This product is said to be used as standard equipment by every manufacturer of automatic phonographs and distributed by the leading record companies.

“Its performance record is said to fully authenticate the advertised statement of ‘better than 2000 plays!’ The elliptical pointed needle is comparable to a sapphire in its hardness. As it is matched to all standard pick-up heads, true reproduction is received regardless of volume. It is said to be the only long life needle that truly reproduces high fidelity.

“Art Olsen, president of the Permo Products Corporation and one of the most popular men in the automatic field, has extended every possible effort to supply dependable equipment in the industry.”

Despite its stellar rep within the trades, the professional-grade Permo Point needle was still a bit of an insider’s product, perhaps—not a household name. As the economy slowly rebounded and new, more affordable phonographs entered more homes, however, Art Olsen and his crew recognized the need to build a new identity for the general consumer market.

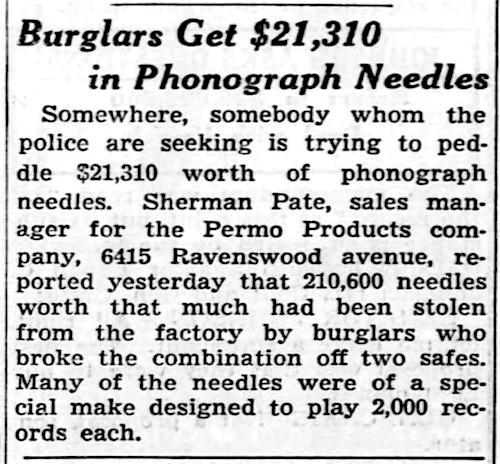

The tipping point might have come in February of 1939, when a peculiar band of burglars broke into the Rogers Park factory and cracked its safes, absconding with a remarkably specific 210,600 Permo Point needles worth $21,130 (about $380,000 after inflation). Were they common criminals? Sleeper agents from a rival stylus manufacturer? I have no idea. But they probably gave Permo board members good reason to consider whether they could offer the average record listener a better deal on needles than the black market could.

The tipping point might have come in February of 1939, when a peculiar band of burglars broke into the Rogers Park factory and cracked its safes, absconding with a remarkably specific 210,600 Permo Point needles worth $21,130 (about $380,000 after inflation). Were they common criminals? Sleeper agents from a rival stylus manufacturer? I have no idea. But they probably gave Permo board members good reason to consider whether they could offer the average record listener a better deal on needles than the black market could.

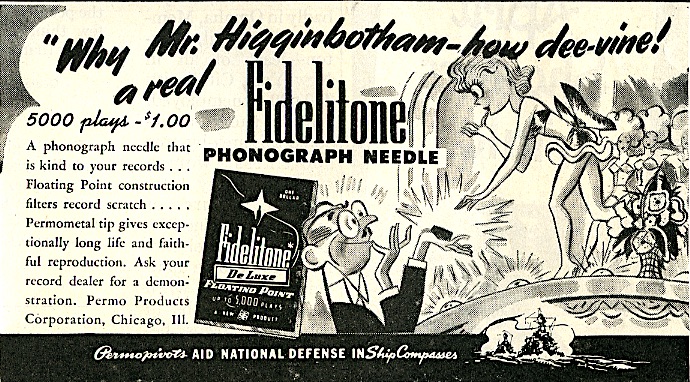

And so, by the following year, Permo introduced the Fidelitone brand as its new record needle aimed specifically at the everyman, with starting price points at 50 cents and a buck.

[A 1942 ad for the Fidelitone DeLuxe promises 5,000 plays for a mere $1 cost]

[A 1942 ad for the Fidelitone DeLuxe promises 5,000 plays for a mere $1 cost]

“Fidelitone gives you a brilliant performance and assures a longer life for your cherished records,” one ad read. “Designed to bring you thousands of perfect plays with a fine, pure tone that will be unexcelled throughout its long life, the Fidelitone Master glides gently along the grooves with a considerate kindness to your precious records. It filters record scratch and boasts a patented device which locks the needle in the tone arm securely.”

The national Fidelitone marketing campaign really kicked into gear in 1941, which again, wasn’t the best timing in the world.

IV. The General Morale

After Pearl Harbor, Permo’s Chicago factory was assigned an increasing number of U.S. military contracts, utilizing the same materials from its styluses to produce delicate components for airplane instruments and battleship compasses. As a decorated veteran himself, Art Olsen was more than happy to shift over some of his resources for the greater cause. “PERMO willingly and anxiously accepts this condition as its patriotic duty,” the company noted in an open letter to jukebox operators in 1942, “and shall not complain of the extent to which this activity [war production work] may grow.”

At the same time, however, Olsen clearly wanted it known that his normal product—the record needle—still served an important role of its own in the war effort.

“Phonographs contribute much to the building of the general morale,” that same 1942 letter noted, “as a large percentage of the public and the hundreds of thousands of the country’s fighting forces depend on them for their public entertainment. . . . A long-lasting needle,” Olsen further argued, “fits in admirably with the general urgency for national conservation of resources.”

Cynically, you might say Permo was just looking for a loophole to keep its commercial arteries open in the midst of a war with no foreseeable end (if so, who could blame them?). But in that same winter of ’42, the company at least went the extra mile to prove its “point.”

“Permo Products Corporation, manufacturer of the Permo Point needles for coin phonographs and Fidelitone line of long life phonograph needles for home use, recently made a donation of Standard Permo Point needles to the U.S. armed forces for use in automatic record players in army recreation rooms,” Billboard magazine reported on January 10.

“Permo Products Corporation, manufacturer of the Permo Point needles for coin phonographs and Fidelitone line of long life phonograph needles for home use, recently made a donation of Standard Permo Point needles to the U.S. armed forces for use in automatic record players in army recreation rooms,” Billboard magazine reported on January 10.

“In acknowledgment Brigadier General F.H. Osborn, chief of the morale branch, writes as follows: ‘This will acknowledge receipt of the package of 300 Standard Permo Point needles. It is gratifying to learn of your gift of this material for use of the men in the armed forces in outlying bases. The gift will contribute substantially to the contentment and well-being of the men serving our country in isolated locations. I am sure these men will be deeply appreciative.’”

One of those men, incidentally, would be Sherman Pate, as the Permo V.P. enlisted for service that same year.

One of those men, incidentally, would be Sherman Pate, as the Permo V.P. enlisted for service that same year.

A good reputation built in war goes a long way in peace, and so it was for the Permo Products Co., which was about to re-organize as Permo Incorporated. When the boys finally came home and sat down to listen to their own phonographs, the Fidelitone brand emerged as the nations’ best seller.

V. Fidelitone!

During and after the war, Art Olsen never lost his obsession with R&D and the next big innovation. Toward that effort, an accomplished engineer named Henry L. Imelmann was brought in to work on the Fidelitone lines, and his patents soon joined new ones attributed to Olsen and Sherman Pate, who apparently was also more than just a sales guy.

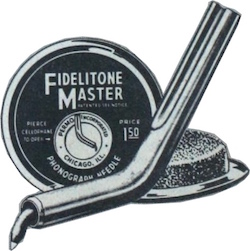

By the mid ‘40s, there was an established family of Fidelitone needles, two of which are part of our museum collection—the Fidelitone Master and its slightly pricier cousin, the Fidelitone Supreme. A 1948 advertisement in Billboard laid out the full line-up:

The budget option was the Fidelitone Floating Point (50 cents): “Its precious metals tip assuring long life makes it worth much more than its modest price.”

The budget option was the Fidelitone Floating Point (50 cents): “Its precious metals tip assuring long life makes it worth much more than its modest price.”

One step up was the Fidelitone DeLuxe ($1.00): “Gives superb performance. Has all six standard Fidelitone features.” Those exclusive features, incidentally, were: (1) Permometal-Permium-(Osmium Alloy) Tip, (2) Floating Point Construction, (3) V-Groove Locking Design, (4) Minimum Record Scratch, (5) Maximum Kindness to Records, (6)Maximum Needle Life

One step up was the Fidelitone DeLuxe ($1.00): “Gives superb performance. Has all six standard Fidelitone features.” Those exclusive features, incidentally, were: (1) Permometal-Permium-(Osmium Alloy) Tip, (2) Floating Point Construction, (3) V-Groove Locking Design, (4) Minimum Record Scratch, (5) Maximum Kindness to Records, (6)Maximum Needle Life

Fidelitone Master ($1.50): “Has all Fidelitone features plus vertical compliance. Gives thousands of fine reproductions. Truly a master of performance.” Directions from the Master needle in our collection: “Place needle in pick-up so that offset extends toward front of tone arm. Tighten thumb screw securely. When needle is properly inserted the offset portion will angle toward the center of the turntable.”

Fidelitone Master ($1.50): “Has all Fidelitone features plus vertical compliance. Gives thousands of fine reproductions. Truly a master of performance.” Directions from the Master needle in our collection: “Place needle in pick-up so that offset extends toward front of tone arm. Tighten thumb screw securely. When needle is properly inserted the offset portion will angle toward the center of the turntable.”

Fidelitone Supreme ($2.50): “The needle with spring in its heart. The only straight type needle with both vertical and horizontal compliance—increasing needle and record life.”

Fidelitone Supreme ($2.50): “The needle with spring in its heart. The only straight type needle with both vertical and horizontal compliance—increasing needle and record life.”

The Fidelitone Classic ($5.00): “The Ultimate in tonal production; in the preservation of records; in eliminating record scratch and extraneous noises; in increasing needle life with thousands of plays; in protection against needle damage.”

The Fidelitone Classic ($5.00): “The Ultimate in tonal production; in the preservation of records; in eliminating record scratch and extraneous noises; in increasing needle life with thousands of plays; in protection against needle damage.”

Most of these 1940s styluses came packaged with a record cleaning brush, and despite their relatively friendly prices, they still had a bit of a regal look to them—a clear intention to keep Permo’s classy standing above its riff-raff competition.

Around this same time, vinyl was slowly emerging as the new material standard in the record business, and needles needed to adjust accordingly. The Fidelitone line continued to expand, with dozens of variations soon promising compatibility with 33-1/3, 45 and 78 RPM records, plus countless additional refinements customized for the cartridges of all the big turntable manufacturers of the day. They even rolled out diamond and sapphire models when reduced tracking pressure in record players made them gradually less harmful to the vinyl and more appealing to audiophiles.

Around this same time, vinyl was slowly emerging as the new material standard in the record business, and needles needed to adjust accordingly. The Fidelitone line continued to expand, with dozens of variations soon promising compatibility with 33-1/3, 45 and 78 RPM records, plus countless additional refinements customized for the cartridges of all the big turntable manufacturers of the day. They even rolled out diamond and sapphire models when reduced tracking pressure in record players made them gradually less harmful to the vinyl and more appealing to audiophiles.

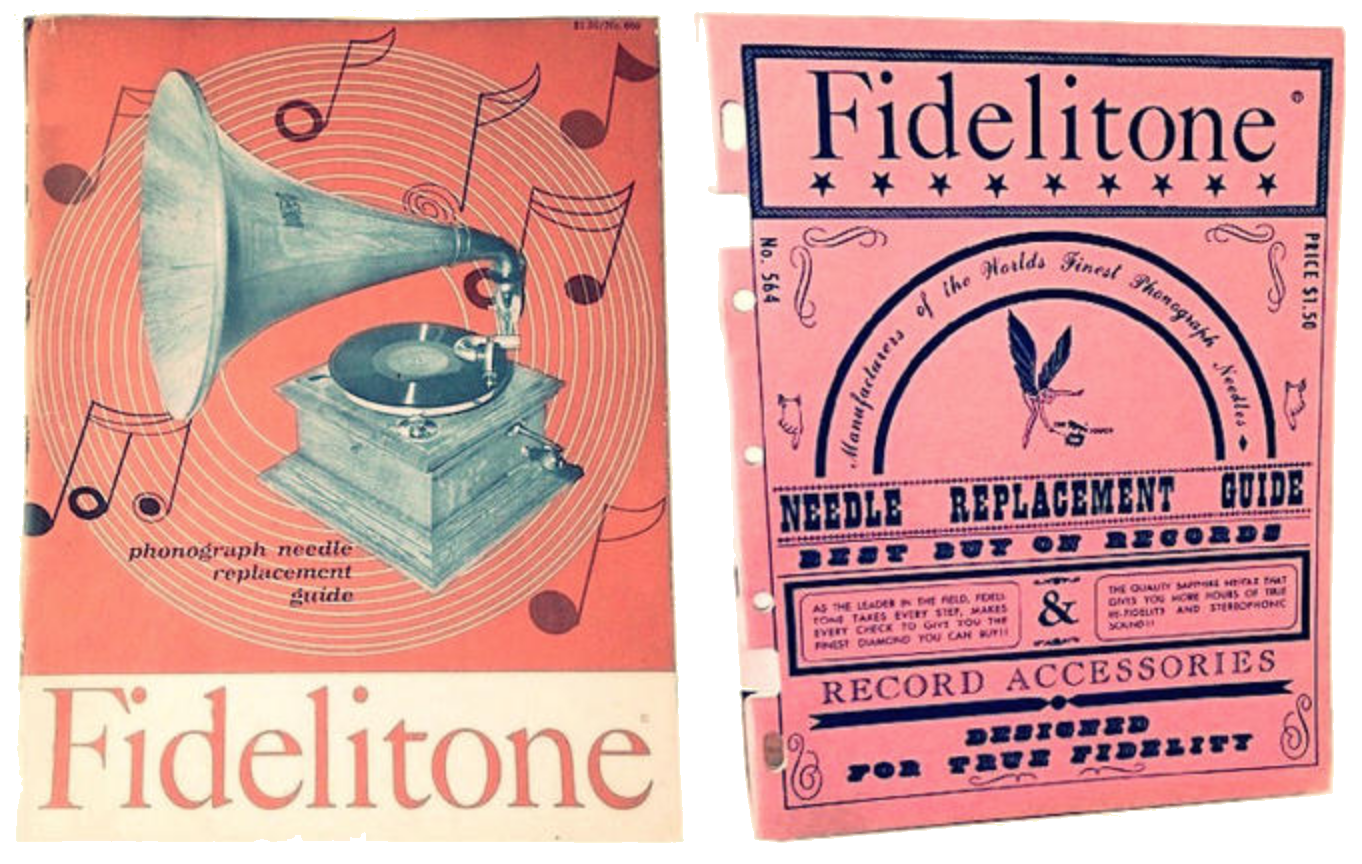

Along with a standard catalog of its own products, Permo Inc. started producing some of the earliest Needle Replacement Guides—the types of resources still used by record collectors to figure out which random little thingamabob will actually work with any given obscure record player.

VI. No Such Thing as Permanent

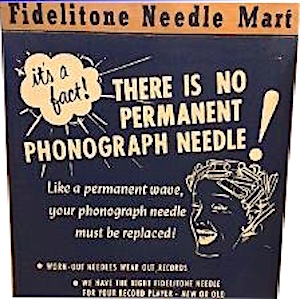

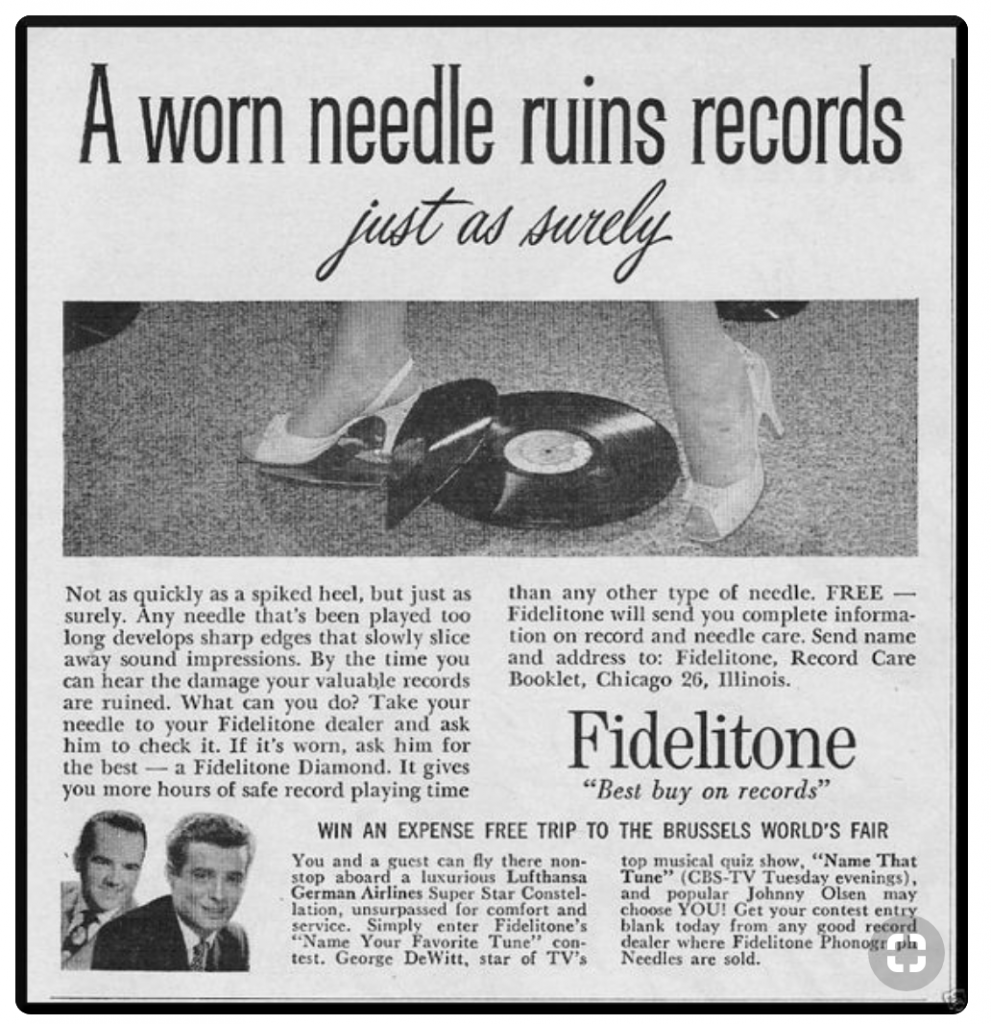

By 1950, Arthur J. Olsen, at the age of 53, was sort of the de facto patriarch of the phonograph needle industry. He was now 20 years into the work, and he knew the ins and outs like nobody else. His only fear by now, perhaps, was that he’d created a monster—the idea of a stylus so durable and consistently effective that a consumer with a lesser ear might just consider it a “permanent” solution; a “one and done.” Some record players had already started coming out with permanently built-in needles, and while most of them were massive failures, Olsen still wanted to dispel the myth of any such magic. A business dependent on repeat purchases couldn’t exactly claim otherwise.

“There has been a lot of talk and advertising about permanent phonograph needles,” Olsen wrote in the Broadcast Engineers Journal. “Many people are firmly convinced that the phonograph needle in the record player they have recently purchased will never wear out. They are in for a rude awakening when impaired reproduction becomes apparent; then, too late, they will discover the damage to their records as a result of a WORN OUT or fractured needle.

“There has been a lot of talk and advertising about permanent phonograph needles,” Olsen wrote in the Broadcast Engineers Journal. “Many people are firmly convinced that the phonograph needle in the record player they have recently purchased will never wear out. They are in for a rude awakening when impaired reproduction becomes apparent; then, too late, they will discover the damage to their records as a result of a WORN OUT or fractured needle.

“The positive fact is that THERE IS NO PERMANENT PHONOGRAPH NEEDLE! Let’s look at ‘the record,’ as the late Al Smith so well put it. When two materials rub together, particularly in dry friction, one or both must wear. This is particularly true in the case of the point of a phonograph needle in contact with a record groove when the average playing area of contact of the needle point is actually under pressures of from 25,000 to 6,000 pounds per square inch.”

It’s a lesson that still warrants attention for today’s modern crop of vinyl spinners, many of whom have embraced vintage technology for the hipster cred without, perhaps, totally contemplating the minutiae of the machines.

On a darker level, Art Olsen’s matter-of-fact analysis of material impermanence also winds up applying to his own story.

VII. The Needle Has Landed

On March 3, 1951, Cash Box magazine published a letter written by Sherman Pate—by then Executive Vice President of Permo, Inc.—to George A. Miller, National Chairman of the Music Operators of America, discussing the upcoming OMA convention in Chicago and Art Olsen’s appearance there.

“We want you to know that Permo will do everything it can to make the meeting this year an outstanding success,” Pate wrote.

“Art Olsen’s interest in and friendship for Music Operators stems from his long and happy association with the industry during the last twenty-two years. His aim is to express his thanks to his friends in the industry by manufacturing the finest coin phonograph needles that can be made and by supporting them in their common efforts to improve their position in the market.

“ . . . We of Permo look forward to meeting you and all other Music Operators at the Palmer House at Chicago, March 19th to 21st, 1951.”

[Permo Inc. president Arthur J. Olsen, center, with Bill Gersh (left) of Cash Box magazine and George A. Miller (right), chairman of the Music Operators of America, 1950]

[Permo Inc. president Arthur J. Olsen, center, with Bill Gersh (left) of Cash Box magazine and George A. Miller (right), chairman of the Music Operators of America, 1950]

Less than a week later, and just 11 days before the 1951 convention, Art Olsen was dead—the victim of a heart attack suffered while aboard his yacht near Key West (the man had done well for himself).

“All the industry here has been tremendously saddened by the passing of Arthur J. Olsen,” Cash Box later reported. “. . . Many coinmen, who had planned on being in Chicago on March 18 for the start of the MOA Convention, upon hearing of Olsen’s death, flew in for the funeral. . . . Many stated at the services, ‘He was a real man, as well as one of the best friends any man could ever hope to have.’”

Olsen’s death was obviously a shock to his company, too, but in his new role as president, Sherman Pate assured investors that Permo Inc. and its then subsidiary, Fidelitone Inc., would carry on the “policies and practices” of its founder. Shortly thereafter, district manager Doug Hudson and his wife Arless (sister to Art Olsen’s widowed wife Ruth) stepped in and purchased the company shares owned by Art’s daughter, who wasn’t interested in entering the business. From that point forward, the Hudson name would be synonymous with Fidelitone in all its future manifestations.

[Left: Art Olsen and his wife Ruth. Right: Ruth’s sister Arless Hudson with husband Douglas F. Hudson. The Hudsons purchased a chunk of Permo / Fidelitone stock in the 1950s and would keep it a family business into the 21st century, with Doug Sr. long serving as president and chairman.]

[Left: Art Olsen and his wife Ruth. Right: Ruth’s sister Arless Hudson with husband Douglas F. Hudson. The Hudsons purchased a chunk of Permo / Fidelitone stock in the 1950s and would keep it a family business into the 21st century, with Doug Sr. long serving as president and chairman.]

Along with Pate and Hudson, additional leadership from Thomas Feten (Executive VP), Lloyd Anders (VP of Engineering), Gail Carter (VP of Sales), P. W. Olson (plant superintendent), and William Lenz (Metallurgical Director) helped the company buffer its founder’s loss in the 1950s.

Finally, after Doug Hudson assumed the presidency from Pate in 1956, the decision was made to leave the “Permo” name to the past and carry on as Fidelitone, Inc., with the goal of diversifying the company’s reach.

In 1959, just as stereo sound was exploding on the scene, the company introduced its first major stylus innovation since Art Olsen’s death—the Pyramid Point; developed by new chief engineer Charles Weigand. Two years later, in a more eyebrow-raising move, Doug Hudson announced the acquisition of the JVM Microwave Company, leading to a brief company re-brand as Fidelitone Microwave, Inc.

The name, and the microwave business, didn’t pan out. But the move was indicative of the company’s focus on adventurous new lines of expansion.

[In the 1960s, Fidelitone became the world’s largest manufacturer of diamond styluses; a far cry from the days when Art Olsen preached for precious metals]

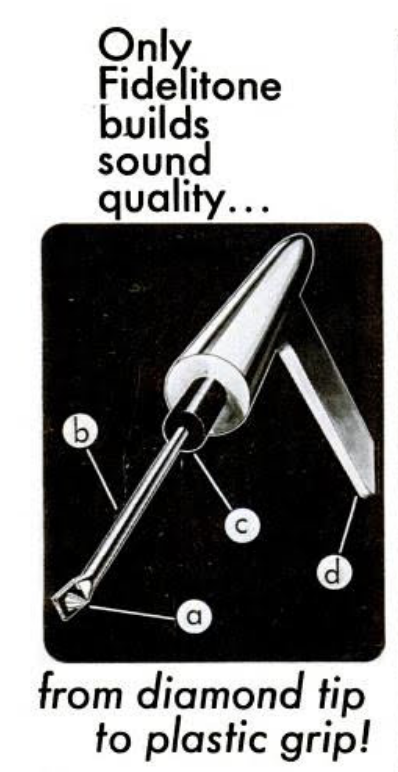

Fidelitone was no longer a one-trick pony. By 1970, they were the world’s biggest producer of diamond point needles (clearly scrapping Art Olsen’s old theories), but the Rogers Park factory was also cranking out dozens of other audio/recording components—aluminum needle shanks, rubber bearings, plastic lever arms and packaging, and even early blank cassettes and recording tape. “Everything is made and put together in our Chicago plant,” boasted a 1970 advertisement. “The complete Fidelitone story is easily summed up . . . stick with the leader! From diamond tip to plastic grip!”

Gosh, if I’d known that the complete Fidelitone story could be “easily summed up,” I could have saved you and me both a ton of time. But since we’ve come this far, I suppose we might as well conclude by noting Fidelitone’s exodus from its longtime Ravenswood plant in the early 1970s. This, for all intents and purposes, lowered the curtain on Arthur Olsen’s original Chicago phonograph business. What came next, no one really could have anticipated.

Gosh, if I’d known that the complete Fidelitone story could be “easily summed up,” I could have saved you and me both a ton of time. But since we’ve come this far, I suppose we might as well conclude by noting Fidelitone’s exodus from its longtime Ravenswood plant in the early 1970s. This, for all intents and purposes, lowered the curtain on Arthur Olsen’s original Chicago phonograph business. What came next, no one really could have anticipated.

According to Doug Hudson’s son Craig, CEO of Fidelitone Logistics, his father didn’t necessarily plot out the company’s extreme evolution in the ’70s, but he did have the guts to see a thread and follow it. “The phonograph needle is really a repair part,” Hudson told Family Business in 2010. “We sold needles to Sears, whose customers brought their phonograph players in for repairs. In the ’70s there was a big influx of Japanese consumer products into the country. We convinced Sears to let us handle the repairs for TVs and radios. With that, Fidelitone went from manufacturing a dying product to distributing parts for a rapidly growing industry.”

After relocating to suburbia—first Palatine, then Arlington Heights, and finally Wauconda—Fidelitone’s parts distribution business gradually led to the creation of one of the country’s first comprehensive individual drop ship programs (shipping directly to the end user), and a full-on logistics business was born. The timing, for once, was perfect.

In the 1980s, as people began chucking out their old turntables and stacks of styluses collected dust in empty record shops, Fidelitone carried on. Arthur Olsen’s dream of creating something “long lasting” had, in the end, exceeded anyone’s expectations.

[The Fidelitone All Groove Needle display still lists Permo Incorporated as the manufacturer, suggesting it dates to the 1950s, before Fidelitone Inc. became the official company name]

[The Fidelitone All Groove Needle display still lists Permo Incorporated as the manufacturer, suggesting it dates to the 1950s, before Fidelitone Inc. became the official company name]

Sources:

Fidelitone Logistics Official Website

“A Long Playing Legacy” – Family Business, Autumn 2010

“Looking Ahead with the Operators” – Billboard, March 28, 1942

“There Is No Permanent Phonograph Needle” by Arthur J. Olsen, The Broadcast Engineers Journal, Feb 1950

“The Phonograph Needle – Bulletin II” by Arthur J. Olsen, The Broadcast Engineers Journal, April 1950

“Permo Point Plans MOA Meet Exhibit” – Cash Box, March 3, 1951

“Many Attend Last Rites for Arthur J. Olsen” – Cash Box, March 24, 1951

“Small in Size, But Large in Function” – Automatic Age, February 1937

“Permo Needle Gift for Army Phonos” – Billboard, Jan 17, 1942

Fidelitone ad – Billboard, Feb 7, 1948

“It’s All in the Point: Permo Combines 20 Years’ Hard Work, Experience, Research and Funds to Perfect Juke Needles” – Billboard, Feb 18, 1950

“It Isn’t Round Now, It’s A Pyramid: Needle Gets Needled!” – Chicago Tribune, October 4, 1959

“Electronics Firm Sold to Fidelitone” – Chicago Tribune, April 8, 1961

U.S. Patent – “Needle” – Arthur J. Olsen, Jan 2, 1932

U.S. Patent – “Phonograph Needle” – Arthur J. Olsen, August 10, 1936

I have a tool box sold by Sears Roebuck as a Craftsman Brand Item. The part Number indicates that it was manufactured by Fidelitone in December of 1986. Could anyone tell me the location where this item (City and State) was actually manufactured? Was it a Fidelitone operation or a subcontractor who actually made the tool boxes? They probably made many different sizes and shapes of these items for Sears, possibly for many years. The Fidelitone company history indicates that they were a supplier of other items for Sears over the years.

Thank you very much for any help in this matter of interest.

I made a mistake. 706 is the supplier code involved here and I have discovered there were two Suppliers with that Code The other supplier is Waterloo Industries and they are the manufacturers of Craftsman Tool Boxes.

I have a small tool like device marked with “Fidelitone” that may be related to this topic.

It is aluminum, about 1-5/8” in diameter, has four flat tabs like screwdriver blades, a center hole, an arrow device centered over the hole with the number 1 on one side of the hole and 2 on the other.

Does this ring a bell?

45 RPM record adapter.

Hi

I saw on eBay a new old stock Fidelitone replacement cartridge and stylus for the Shure V15 cartridge/stylus. The cat no. is 306e-549. It is made in Japan. Are Fidelitone phono cartridge/stylus manufactured in Japan? Is it still operating?

Thank you

ACTUALLY a Question. I am trying to find out around how many plays could I expect from a Fidelitone Floating Point Long Life Phonograph Needle-Permo Inc. the 50 cents one?

Also the Fidelitone Floating Point Long Life Phonograph Needle-Permo Inc. De Luxe one $1.00?

Also the Fidelitone Master $1.50 Around how many plays can I get with the master?