Museum Artifact: Industrial Signal Horn Siren, 1920s

Made By: Benjamin Electric MFG Co., 120-128 S. Sangamon St., Chicago, IL [West Loop] and Des Plaines, IL

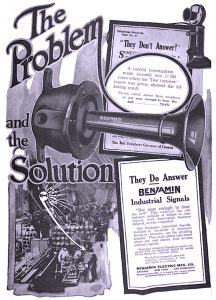

“The clear, powerful tones of Benjamin Signals are preventing lost calls, lost time, and costly interruptions the country over. To the farthermost corners of the greatest plants they shout the call for attention, finding the wanted man wherever he may be. . . . In machine shops, in erecting shops, in engine and boiler rooms—wherever the clank and clamor of machinery drowns the ordinary bell—there Benjamin Industrials Signals are making the dominant, penetrating appeal and saving dividends to big business.” —Benjamin Electric MFG Co. advertisement, 1919

Organized in 1901, the Benjamin Electric Manufacturing Company wasn’t just emblematic of the new electrical age of American industry, it was catering directly to that industry with its own products—developing hundreds of innovations in factory lighting, warning/call systems, safety devices, and other wired fixtures vital to the 20th century production plant. So prolific was company founder and electrical engineer Reuben B. Benjamin, in fact, that by the time of his death in 1933, only five men had collected more U.S. patents.

The vast majority of Benjamin’s nearly 400 inventions were related to plugs, switches, sockets, and shades for industrial lamps, but as represented by the artifact in our museum collection, he and his team also helped change the sound of the modern factory, introducing improved klaxons or electrical signal horns that were strong enough to pierce through the churning hum of punch presses, screw machines, and conveyor belts; not to mention the daydreams of day-drinking executives.

Our specific Benjamin Horn (not to be confused with the character from Twin Peaks) is model number 8355A, and was officially known as a “Factory Non-Weatherproof Howler,” according to the 1925 edition of the Benjamin Electrical Products catalog. “This howler has a pressed steel body with approved insulated side entrance for open wiring,” the catalog entry reads. “One-piece, drawn brass, bell type sound projector is attached to a heavy pressed steel cover which also carries the mounting bracket. Black enamel finish.” The price tag was $10, which is equivalent to about $150 in modern cash.

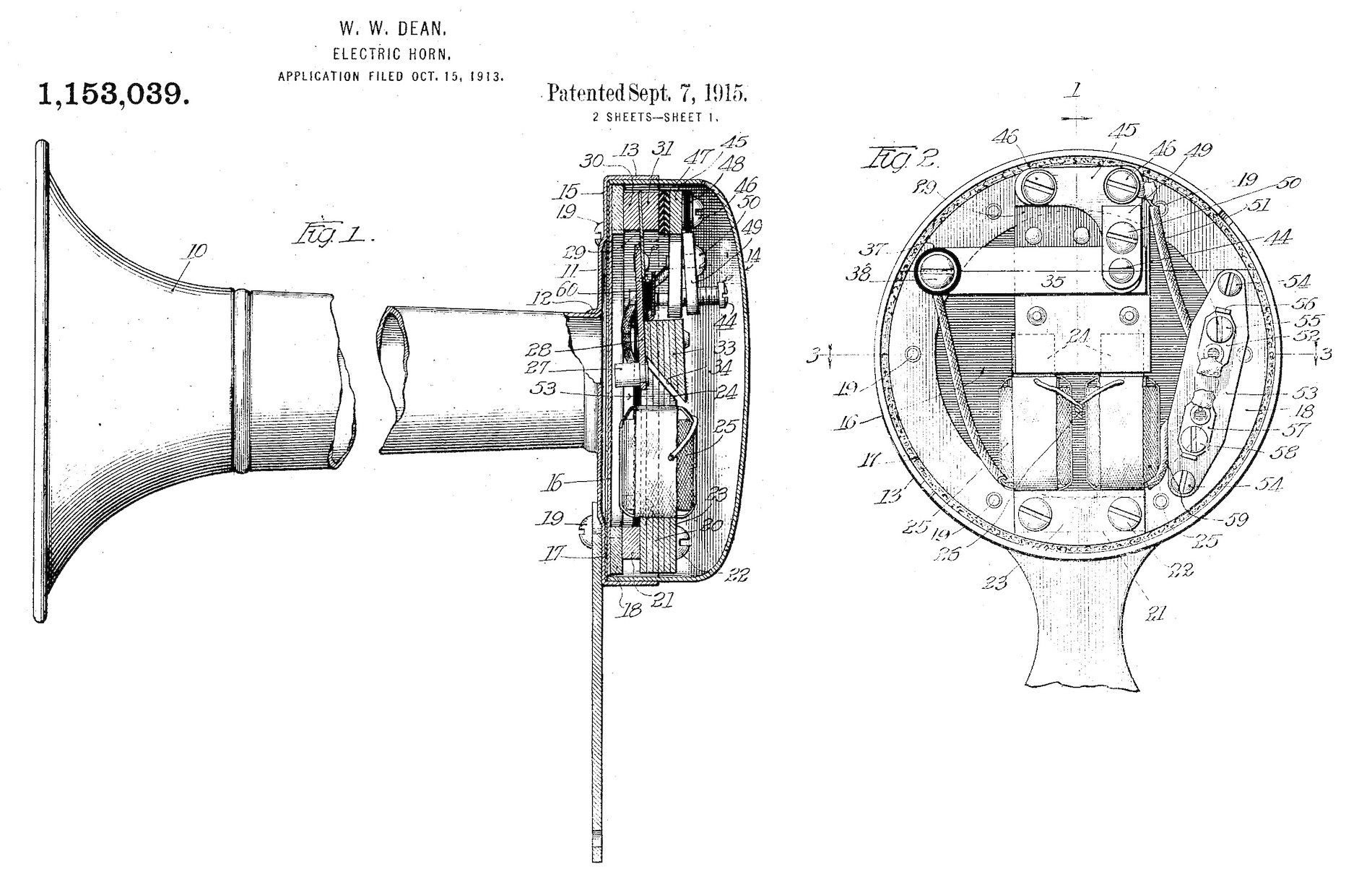

These amplifying devices were essentially supercharged versions of similar designs R. B. Benjamin had patented for use as automobile horns, with various refinements added during the 1910s by engineers Clarence B. Harlow and William W. Dean (a former employee of the Kellogg Switchboard & Supply Co.). As early as 1915, company ads were touting the Benjamin Factory Horn’s “loud, penetrating, far-carrying, non-irritating tone,” and its ability to not only reach the ears of an entire workforce, but—if need be—just one specific employee among them.

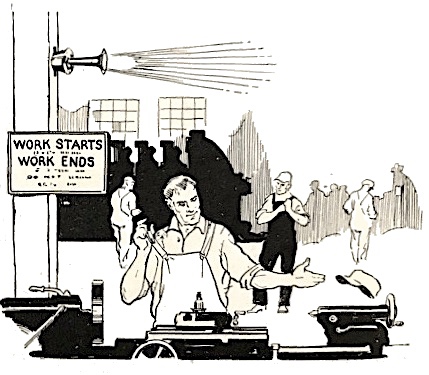

“The Benjamin Horn-Call System cuts out one unnecessary step between caller and called,” explained a 1916 ad in Factory Magazine, “eliminating the necessity for a switchboard and the operator’s attention. At each executive’s desk there is a Horn-Call button, which, operating through a master relay, simultaneously sends the call throughout the plant, and finds the man wanted, wherever he may be.”

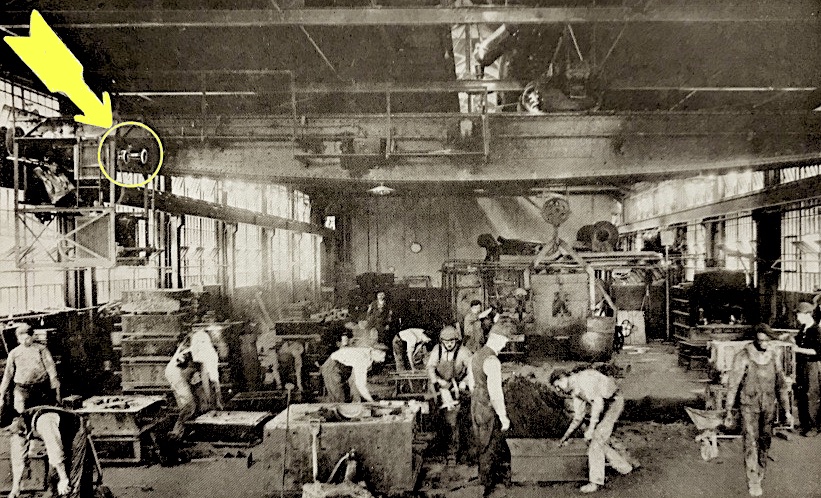

[“The men in this foundry work in sensible unconcern even though their heads might be taken off by the load on the crane” –that’s the actual text that accompanies this image from a 1919 Benjamin Electric sales book called Cause & Effect. “The men know that they will be warned when the crane moves. They have more power for work because they have no reason to worry.”]

By 1925, the Benjamin catalog bragged that its howlers were “so ruggedly made and perfectly assembled that infallible daily performance may be expected for years.” The company also listed 14 potential places where the horns could prove beneficial:

→ Factory superintendent’s and foreman’s calls

→ Signaling the opening and closing hours of labor

→ Tell-tale or warning; for water tank levels, steam or gas pressures, sprinkler systems, etc.

→ Tell-tale or warning; for water tank levels, steam or gas pressures, sprinkler systems, etc.

→ Telephone signals in engine rooms.

→ Industrial Fire Alarms

→ Police Call Systems

→ Burglar Alarms

→ Power Stations, Calls and Signals

→ Traffic warnings for street closings.

→ Railroad Crossings

→ Mines

→ Marine Signals

→ Draw Bridge Signals

→ Municipal Fire Stations

Now, before the howler sounds on us, let’s get a little more of the backstory on R. B. Benjamin and his path to becoming one of Chicago’s greatest—if not particularly well known—engineering geniuses.

History of the Benjamin Electric MFG Co., Part I. Reuben on Rye

“Electrical conveniences in the home are nowadays accepted by the public as a matter of course,” Electrical World Magazine noted in 1923, “without any realization of the brains and energy that have been necessary to place these things at its disposal. To the effort and ability expended in the development of convenient and safe wiring devices the extent and popularity of the whole electrical industry have, nonetheless, been in very large measure due, and in this work the name of Reuben B. Benjamin stands in the front rank.”

Many of the leading engineers in Chicago’s early electrical and telephone firms were recent immigrants from Germany, Sweden, or other corners of Europe. Reuben Benjamin was a different story. His great-grandfather, Ebenezer Benjamin, was a captain in New York’s 17th Regiment during the Revolutionary War, and his father Timothy Benjamin worked as a paper manufacturer in Fulton, New York, where Reuben was born in 1869.

When he was still a boy, Benjamin’s family abruptly abandoned its East Coast roots and headed west for Illinois, but they gave Chicago a miss and settled instead on a remote farm in McLean County. By the time he was a teenager, Reuben had somehow wound up even deeper into the sticks, working as a ranch hand somewhere in South Dakota. Here, “he went through the great blizzards of 1887 and 1888 and developed that pertinacity and strength of character that took him to the front later in life,” Electrical World mythologizes.

Farm life does indeed produce a lot more mechanically-inclined minds than one might initially suppose, and Benjamin’s early experience tinkering with agricultural equipment inspired him to seek out higher education in that field, eventually becoming one of the first three men to earn a degree in electrical engineering from Iowa State College (then known as the Iowa Agricultural College and Model Farm).

After graduating in 1892, Benjamin made the practical decision to head to Chicago to put his new skills to use, and by the following summer, he was already working for the Chicago Edison Company (precursor to ComEd), just in time to take in the stunning displays of electrical power on display at the World’s Columbian Exposition. As a 24 year-old kid plucked out of the Great Plains, this had to be pretty damn exciting.

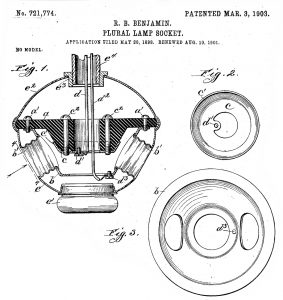

Reuben’s big breakthrough as an inventor came just five years later, in 1898, when he applied for his first patent on a “plural lamp socket.” Also known as a “wireless cluster,” this small but important thing-a-ma-bob was basically an adapter that could be connected to a standard Edison light socket, enabling multiple bulbs and/or appliances to be plugged into the same unit at the same time. Before this, if you wanted to plug in, say, an electric iron, you might need to shut off the light in the room in order to do so. The cluster also reduced the need for wiring work and made a huge difference in how large scale buildings, like factories, could be electrified.

According to a 1986 article by Professor Fred E. H. Schroeder in the journal Technology and Culture, Reuben Benjamin’s original cluster adapters were “manufactured in his basement by high school boys working after school. The $2,400 investment grossed sales of $10,000 in the first year.”

The official “founding” of the Benjamin Electric Manufacturing Company is sometimes aligned with the wireless cluster’s patent filing in 1898, but there was actually a three year gap before Benjamin was able to cobble together investors (and that high school workforce) in order to organize a proper company in 1901.

Putting up the $2,400 were a couple of fellow Iowa transplants—Walter D. Steele and Walter Clyde Jones, as well as Jones’ Chicago law associates Keene H. Addington and Curtis B. Camp. The investment, needless to say, was a wise one.

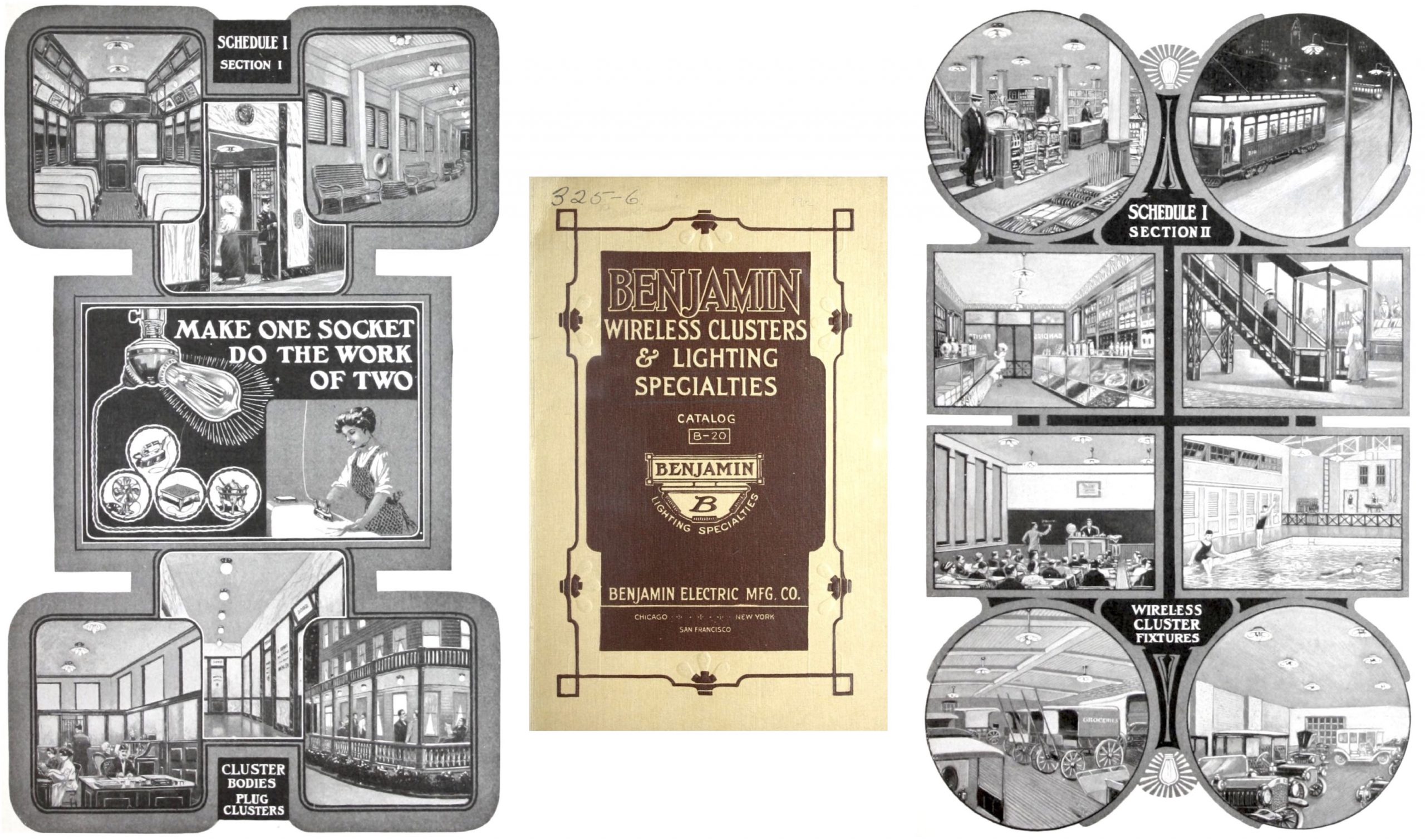

By 1904, the Benjamin Electric MFG Co. had its own facility at 42 W. Jackson Blvd (after street number changes, this is essentially where Union Station is today), with 19 workers making wireless clusters. Just four years later, that workforce had exploded to 174 men and women, producing a wider assortment of “electric goods.” Company offices were also established in New York and San Francisco to keep up with growing national demand, and international factories were opened in Toronto, Ontario, and London, England. It was a rapid rise to worldwide recognition.

[Pages from Benjamin Electric Wireless Clusters & Lighting Specialties Catalog, 1912]

II. Illuminating Ideas

“A workman is no better than his tools. And the greatest of all tools is light—correct light. . . . Benjamin Industrial Lighting is the scientifically correct method of factory illumination. It relieves eye strain and reduces fatigue. It increases production, decreases spoilage, and prevents accidents. It keeps workmen in better spirits, making them better husbands and better fathers, as well as better workmen.”—Benjamin Electric advertisement, 1919

In 1910, Benjamin Electric moved into a four-story building at 120-128 S. Sangamon Street, which housed both the corporate offices and all regional manufacturing for most of the next decade. That structure is still standing today, largely unchanged.

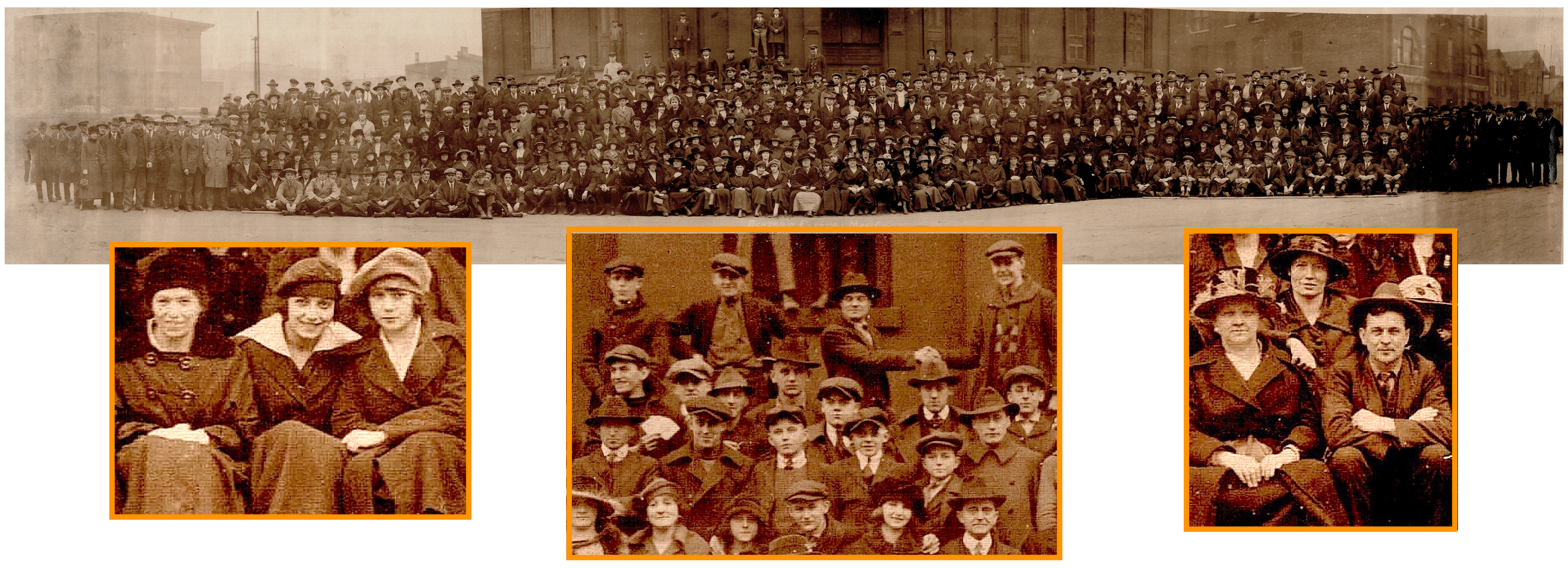

Thanks to Reuben Benjamin’s great-grandson Jeff Benjamin, who reached out to the Made In Chicago Museum in 2021, we have a rare high resolution photo depicting the full workforce of the Benjamin Electric Company gathered outside the Sangamon Street plant in 1919. It suggests a pretty equal balance of male and female employees, covering a broad age range. Zooming in on a few segments of wide angle shot brings out some of the personalties of these folks, as well; some of them smiling in the aftermath of both World War I and the Spanish Flu pandemic.

[Workers pose for a photo outside the Benjamin Electric plant, November 1919. Courtesy of Jeff Benjamin]

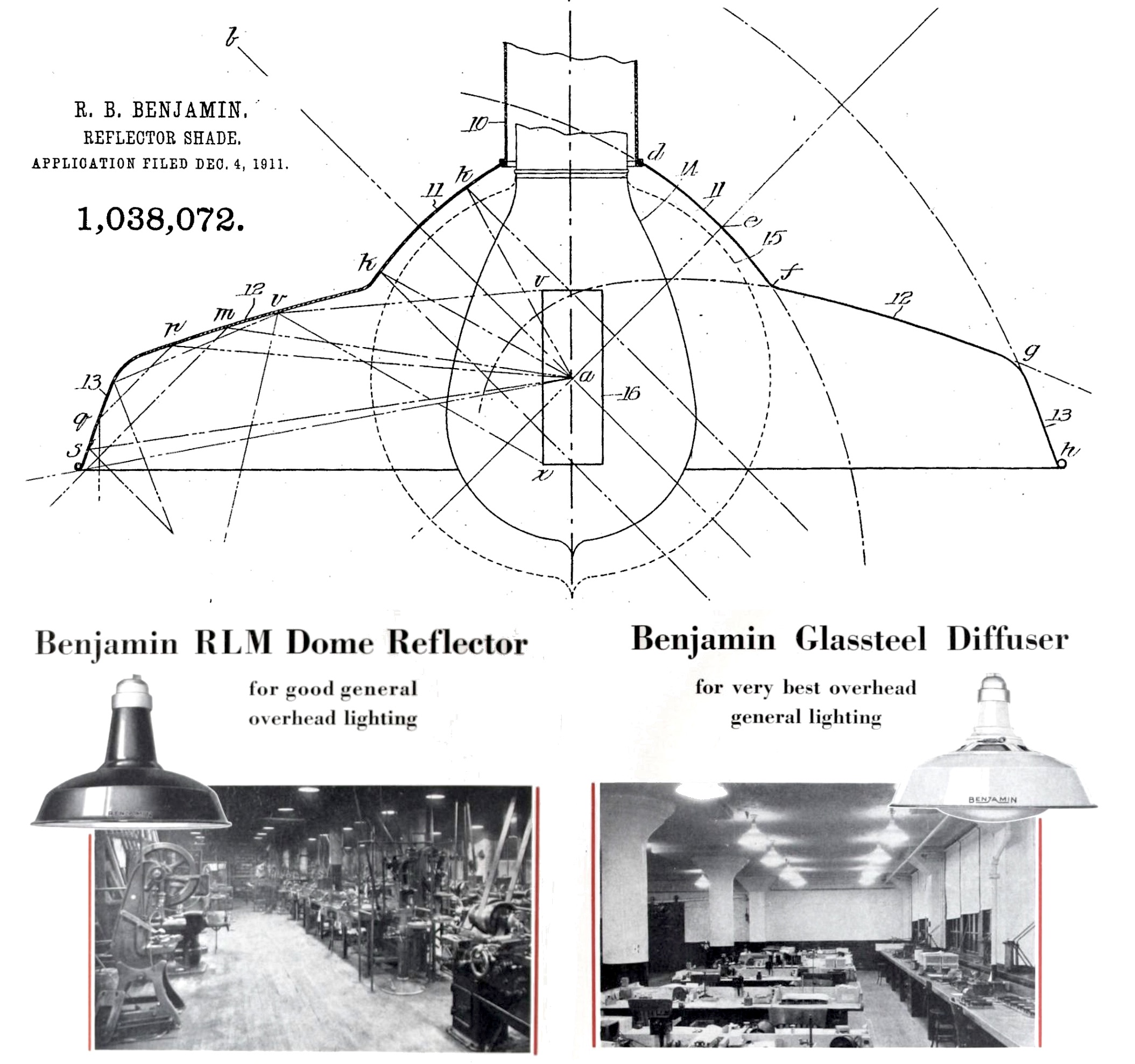

During the early years at the Sangamon plant, Reuben Benjamin was fine-tuning what might be his most instantly recognizable creation—the RLM Dome Reflector lamp shade (RLM = “reflector light microscopy”). These fixtures essentially did for exposed filament light bulbs what Benjamin’s signal horns did for sound. As he described it in a 1911 patent application, the goal was “to provide a shade of this character which will distribute the light rays efficiently and as evenly as possible over the required area. It is a further object of my invention to prevent, as much as possible, waste due to the rays extending outward at too wide an angle.”

Benjamin’s dome shades quickly became a new industrial standard, and when General Electric purchased the rights to the design, RLM lighting was gradually absorbed into the wider culture, embraced by mid-century interior designers for home use, and ultimately revived as retro-chic restaurant decor in the 2000s.

Such an invention would be enough for most wealthy industrialists to hang their hat on, but Reuben Benjamin was too busy throwing new ideas against the wall to stop and admire the ones that stuck.

“The fertility of Mr. Benjamin’s brain,” Electrical World wrote in 1923, “is shown by the fact that, in addition to the wireless cluster, he has been the inventor of the swivel plug, the ‘Benco’ socket, ‘Benox’ interchangeable devices, two-way plugs, many designs of industrial lighting equipment, safety lighting for oil refineries and places where gases or explosive dusts are present, besides hundreds of wiring improvements, many of which have been generally adopted.”

“When I visualize some desirable result,” Benjamin said of his own creative process, “I prefer to head for it directly. This means, first of all, clearing my mind as much as possible of everything that may have been done about it previously.”

This approach notably contrasts with that of one of Benjamin’s idols, Thomas Edison, who often started by analyzing every existing solution before squaring up his own.

“My memory isn’t particularly good,” Benjamin explained, “and strange as it may seem, I believe that this is a help rather than a drawback, because then my brain isn’t cluttered up with old information. I try to proceed straight toward the objective just as though no one else had ever worked on the problem. I depend much on flashes of insight and you’d be surprised how often you can cut ‘cross lots toward your goal when you start with an unprejudiced mind. . . . Heading directly for your goal also brings you up against far less patent interference than you’d think.”

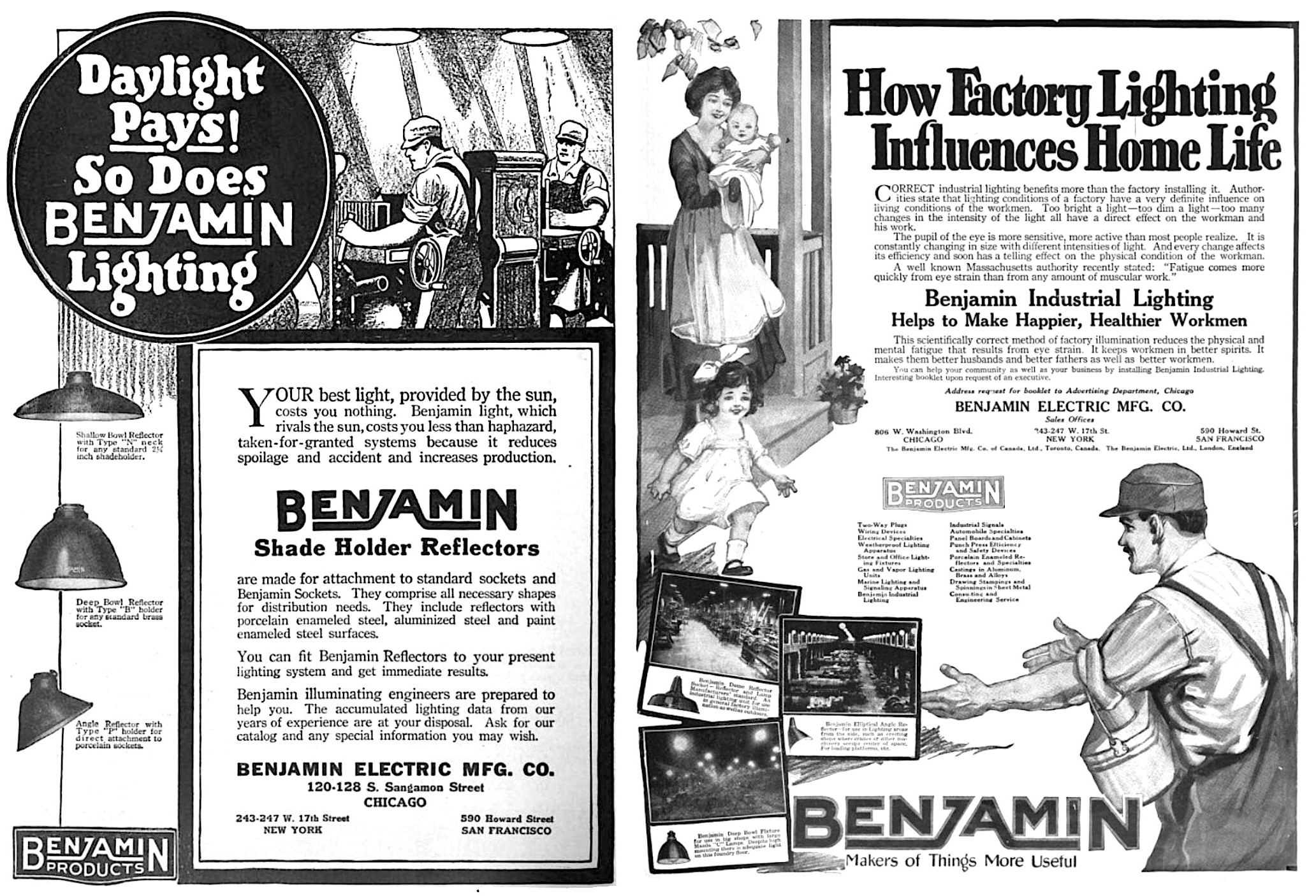

There was equal wisdom behind Benjamin’s marketing strategies, as early company advertisements sold the benefits of their industrial fixtures in a way that managed to address both the humanity of factory workers and the bottom line of factory bosses. Better lighting didn’t just tighten up production line efficiency, it also reduced worker injuries and improved morale—progressive ideas back in the literal dark ages of American manufacturing.

[The Benjamin Electric ads above were both published in 1919, and reveal how the ad department appealed to both the pocket book and heart strings of the factory owner.]

[The Benjamin Electric ads above were both published in 1919, and reveal how the ad department appealed to both the pocket book and heart strings of the factory owner.]

III. Des Plaines! Des Plaines!

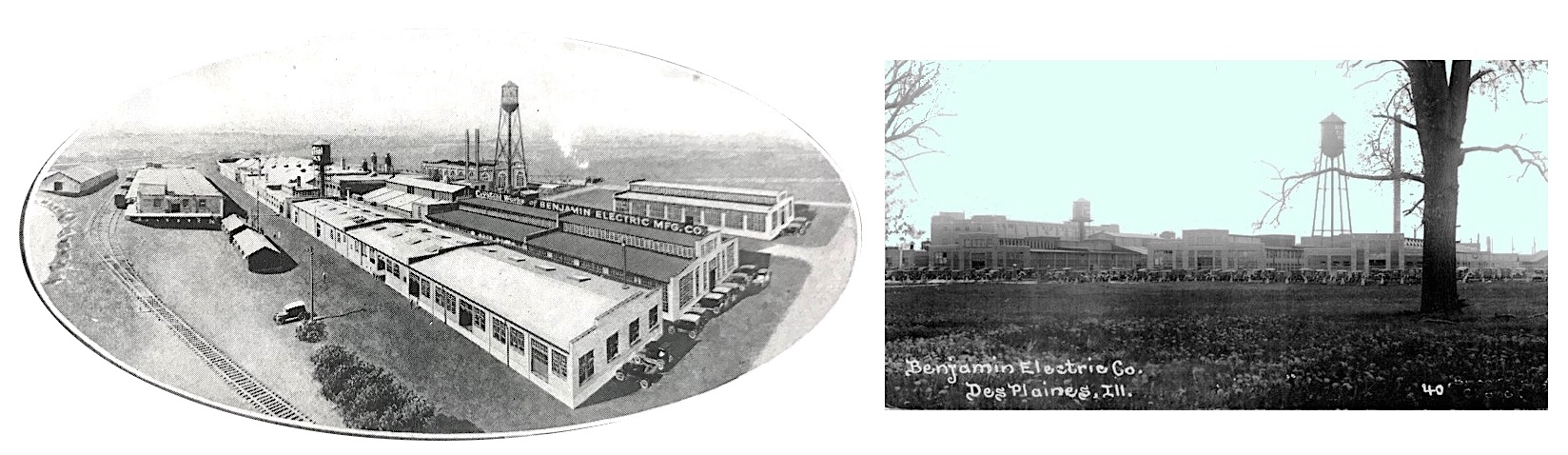

Dating back to Benjamin’s development of the RLM dome, his company had a close working relationship with the Royal Enameling and Stamping Works of suburban Des Plaines, Illinois. Royal made porcelain reflectors and a variety of other products for the firm, and by 1918, with World War I winding down, Benjamin Electric officially absorbed Royal, purchased its plant, and brought on its president, J. Horton Fall Jr., as a director.

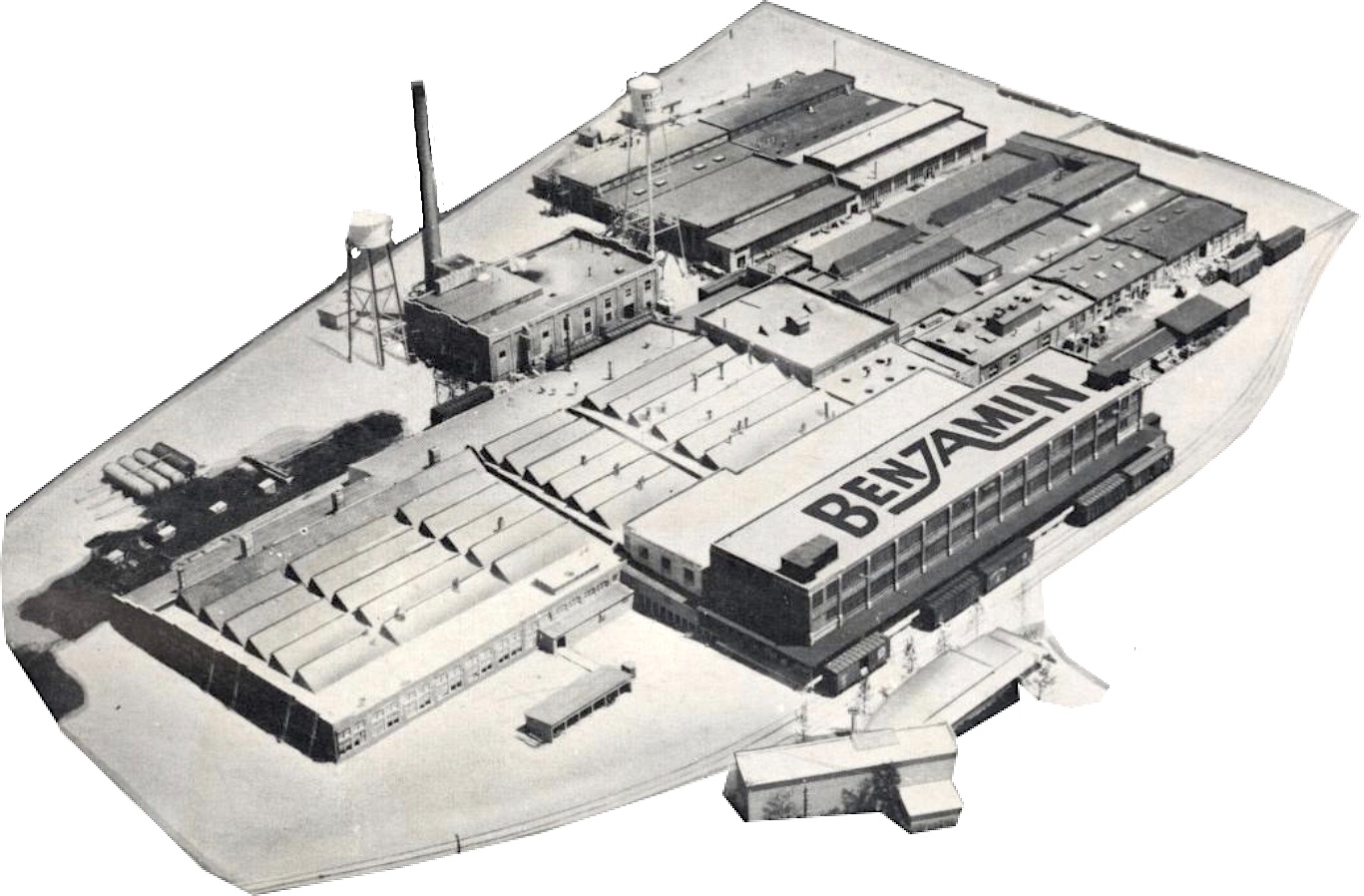

The Benjamin building on South Sangamon Street remained in use as the corporate headquarters through the 1920s, and wiring devices, radio parts, and klaxons (including the howler in our collection) were still made there. Much of the rest of the operation shifted to the expanding “Crysteel” works in Des Plaines, however, which was soon touted as the “World’s Largest Porcelain Enamel Specialties Plant,” making 60-percent of the porcelain reflectors on the planet.

[Benjamin Electric purchased the Des Plaines works of the Royal Enameling and Stamping Works in 1918 and went to quick work expanding it in the 1920s]

“The Crysteel Works at Des Plaines, Illinois, is thoroughly equipped to punch, stamp, draw, spin, and finish sheet metal shapes of every description,” the 1925 Benjamin catalog boasted. “This great modern plant turns out the famous Crysteel Porcelain Enameled products such as table tops, refrigerator linings, stove parts and numerous others. Here are made and finished with Crysteel Porcelain Enamel all the Benjamin Reflectors and super equipment for industrial lighting listed in this catalog.”

Benjamin Electric’s presence on the outskirts of Des Plaines had a great impact on the small town, which more than doubled in population between 1920 and 1930, from 3,451 to 8,798, and doubled again by 1950. Between the wars, the Crysteel plant was easily the top employer in the region, with a workforce reaching upwards of 900 men and women at its post-WWII peak.

“R.B. Benjamin, president of the company, says with much truth that the electrical industry is the magic industry of the world today,” read a 1922 newspaper ad promoting investment in the business. “The growth of the Benjamin Company to a position of national leadership in many lines shows it is keeping pace with this great development.”

IV. “Buoyed Up By Hope”

In 1929, Benjamin Electric sold its Chicago plant and moved its headquarters officially to Des Plaines, although it did maintain a large Chicago warehouse at 215 S. Green Street.

Growth remained steady in the first year of the Depression, but reality soon caught up with the firm. With manufacturing crippled across the country, demand for industrial fixtures was going to be unavoidably impacted, as well, and the numbers soon told the ugly tale—close to $1 million in net losses in 1931 alone. Many employees were laid off at this time and couldn’t return to their positions for two years or more.

To add to the gloom, Reuben Benjamin—while on vacation in Clearwater, Florida—died the day after Christmas, 1933, aged 64. He left behind a wife, five daughters, and a son. The company, meanwhile, was left in the able hands of his longtime business partners Walter B. Steele and W. H. Fall, Jr.

By 1935, business was starting to rebound enough in Des Plaines that a full production schedule was finally put back in place, and a special coach line was created to shuttle in needed workers to the Benjamin plant from nearby Palatine, Arlington Heights, and Mt. Prospect.

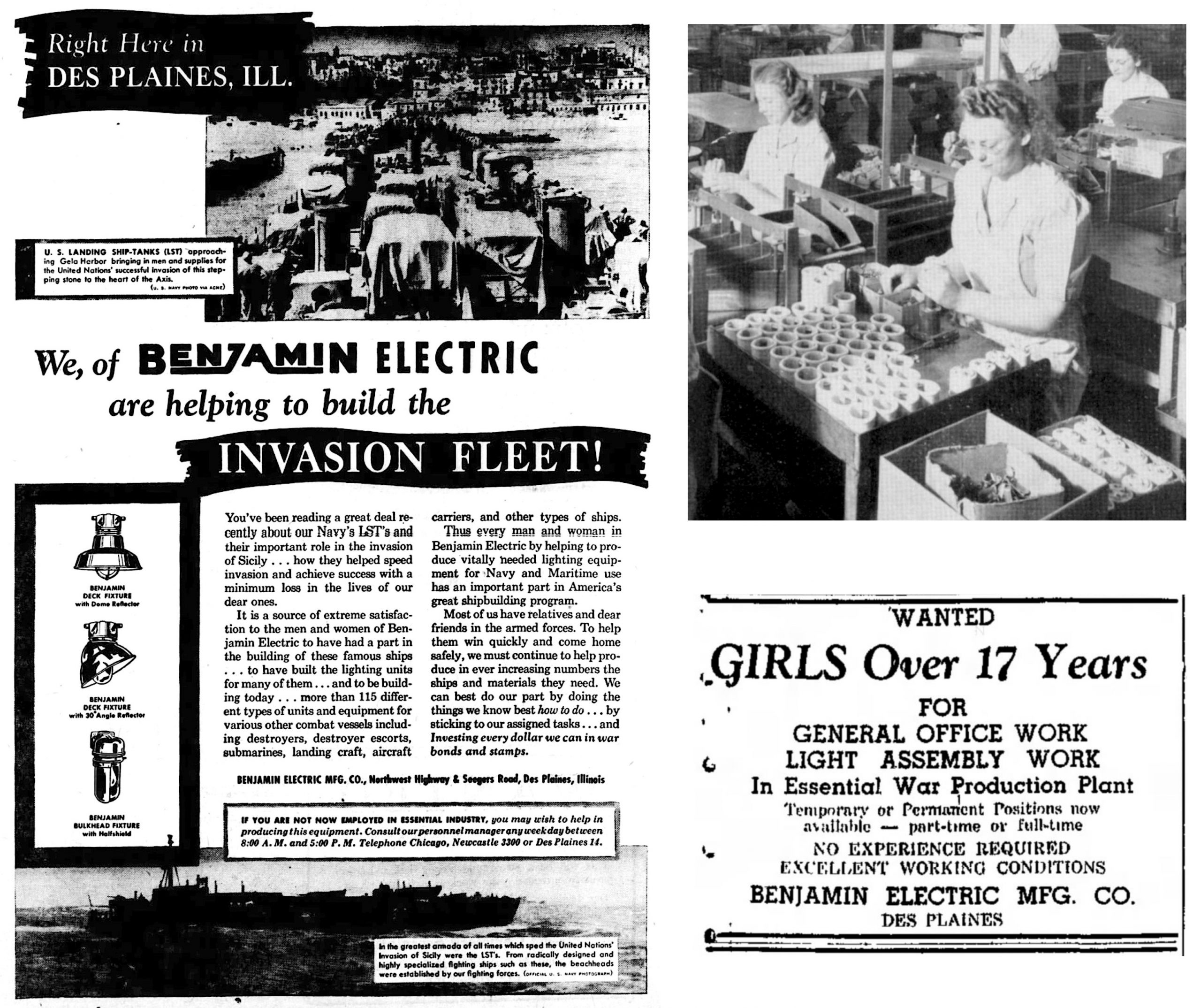

The company’s recovery went from steady to supercharged once the U.S. went into war production again in 1941.

“We, of Benjamin Electric, are helping to build the Invasion Fleet,” a 1943 newspaper ad proclaimed, referring to the Navy’s LSTs (landing ship tanks) during the invasion of Sicily. “It is a source of extreme satisfaction to the men and women of Benjamin Electric to have had a part in the building of these famous ships . . . to have built the lighting units for many of them . . . and to be building today . . . more than 115 different types of units and equipment for various other combat vessels including destroyers, destroyer escorts, submarines, landing craft, aircraft carriers, and other types of ships.”

[Left: 1943 newspaper ad touting Benjamin Electric’s contributions to the war effort. Top Right: Women on the assembly line in Des Plaines. Bottom Right: Newspaper ad seeking women for “general office work” and “light assembly work in essential war production plant,” 1944.]

With nearly 150 Benja-Men now serving overseas, many women who’d previously worked in the assembly department moved to the machine shop, while others were recruited to fill in the assembly line. Each month, the employee newsletter, The Benjamin Whistle, published updates on the “ever lengthening Honor Roll of Benjamin men serving in Uncle Sam’s armed forces.”

“It is with extreme regret that we see our boys leave us,” one issue bemoaned, “but we all know how necessary it is and are buoyed up by the hope that it won’t be long before they are back home again.”

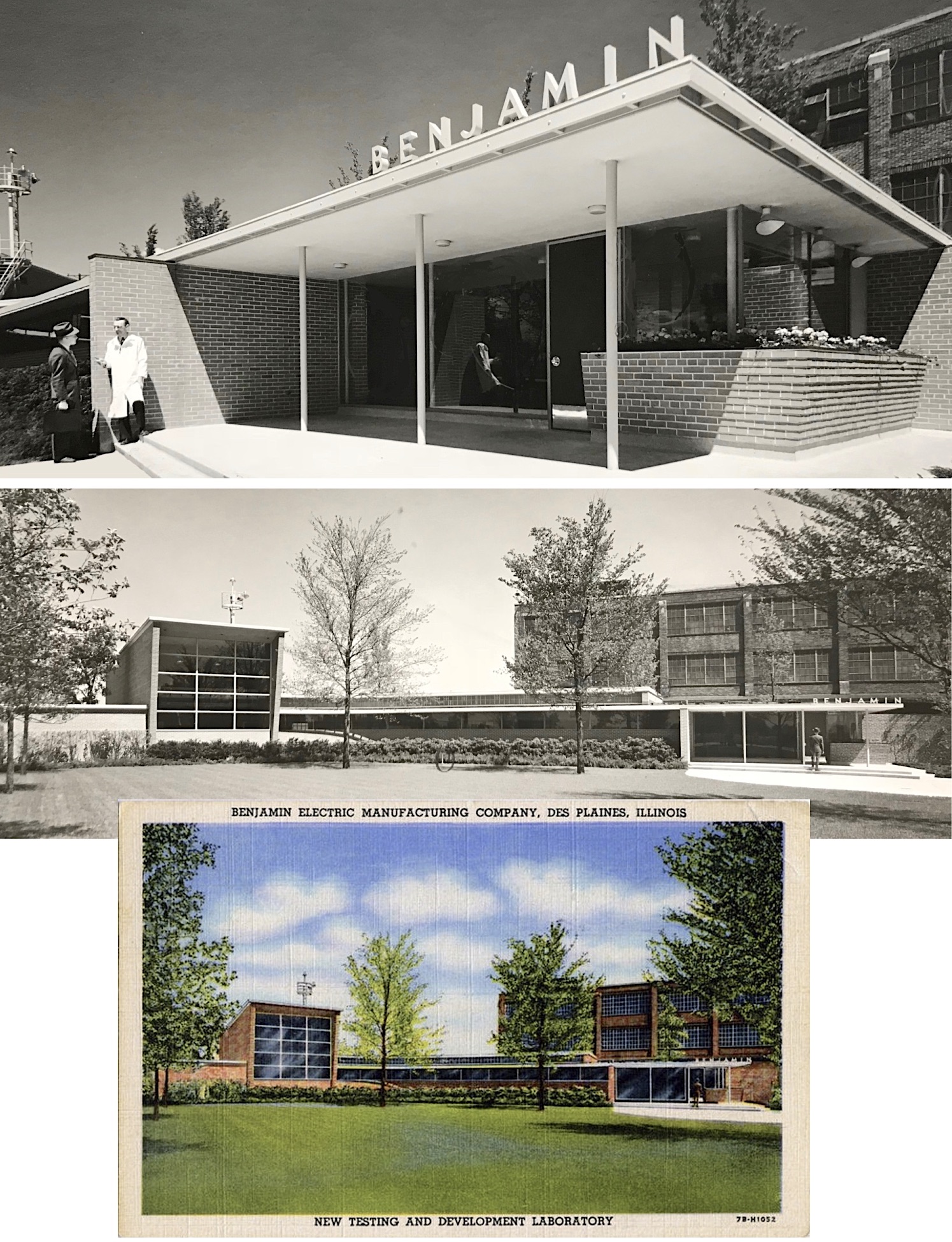

In June of 1945, with the war’s end on the horizon, Benjamin Electric vice president Hoyt P. Steele—son of the half-retired company president—announced immediate plans to invest in a major renovation of the Des Plaines plant, including the construction of a modern research laboratory. The War Production Board gave its blessing to start on the project ASAP, and when Benjamin’s 900 workers gathered for the company Christmas party later that year, the celebration went beyond welcoming home victorious servicemen.

Steele handed out bonus checks to those in attendance (with the help of Santa Claus) and made it known that the company not only planned to bring back former employees still returning from the war, but to hire at least 100 additional veterans to work in the expanded plant in 1946.

V. “Re-Lighting America”

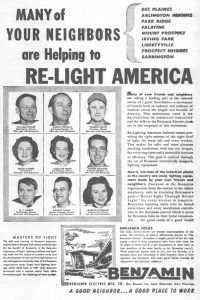

“Many of your friends and neighbors are taking a leading part in the onward sweep of a great movement—a movement of benefit both to industry and millions of workers across the length and breadth of America. This momentous trend is the RE-LIGHTING OF AMERICAN INDUSTRY and the folks at the Benjamin Electric plant are in the vanguard of this movement.” —Benjamin Electric newspaper ad, 1946

William Pahlke, 27th year; Gustav Dueball, 25th year; Herbert Meyer, 24th year; Helen Harper, 21st year; Caroline Horn, 5th year; Marion Haseman, 1st year . . . these were some of the old and new faces one could see at the Des Plaines plant in 1946—all of them enjoying the perks of a fully modernized post-war campus.

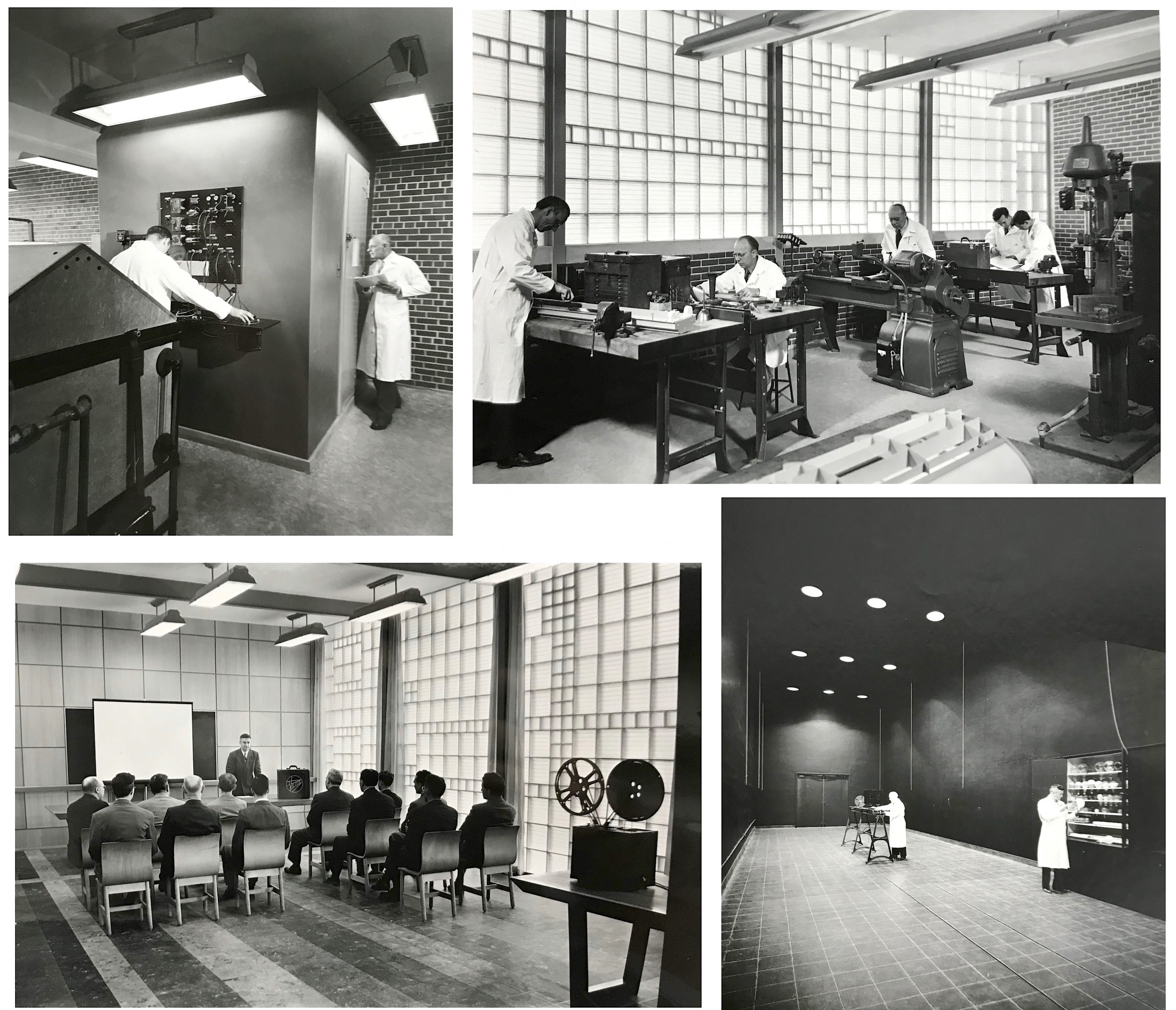

Many of the renovations were practical and related to worker comfort—air conditioned offices, elevators, new windows, repainted walls, improved lighting (with the latest Benjamin fixtures, of course), bigger bathrooms, and a proper cafeteria. The rooms of the brand new laboratory building, on the other hand, suggested the clean competence, sci-fi mystery, and cold sterility of the nuclear age.

“The Benjamin Laboratory has provided the improved facilities required to adequately develop and test complex lighting equipment for modern day needs,” a company catalog explained, noting that those facilities included a Photometric Lab (complete with integrating spheres, photometers, brightness meters and reflectometers), a Laboratory Model Shop for “ironing out design and operation bugs,” and a Test Lab for measuring the equipment’s resistance to corrosion, weathering, vibration, etc.

[Spooky interiors of the new Benjamin Electric Laboratory in Des Plaines, 1946]

Any Benjamin employee—from the top scientist to the press operator or secretary—could seek out company-sponsored extracurriculars, as well, be it the Benjamin Electric softball team, bowling league, glee club, etc. Regular company outings brought the entire workforce and their families out to build a sense of community. Sometimes there were fun talent shows, and other times—like the unfortunate office Christmas party of 1948—the Des Plaines Ladies of the Elks came out and performed an old-time “Blackface Minstrel show” while mixing in impersonations of Hoyt Steele and various other executives. The Daily Herald called it the “highlight” of the event. Anyway . . .

The second generation of company leadership—led by the aforementioned Hoyt B. Steele and new sales manager J. Horton Fall III—didn’t mind being the butt of an occasional joke. Good relations with union workers meant less risk of labor problems down the road. Even when Local 1150 of the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers did go on strike in the spring of 1947, the picketing was peaceful, and the issues were resolved in less than a week. Hoyt Steele later testified before Congress in 1954, stating his strong opposition to the union tactic of “secondary boycotts.” Overall, though, the tenor was generally peaceful at the Benjamin plant.

In 1951, during an event celebrating the company’s 50th anniversary, U.S. Congresswoman Marguerite Stitt Church addressed the crowd, noting that “the contribution of firms like the Benjamin Electric MFG Company in lighting up America’s factories has proved invaluable to the progress of the Nation’s defense efforts.”

That was almost too simple a summation, though. By the 1950s, the Benjamin Electric warehousing facilities, alone, covered three floors and 60,000 square feet, enough to hold “more than 1,800 catalog items,” according to a count in the 1952 catalog.

“A list of the users of these products would begin with the United States Government, take in most of the names of well known industrial giants among the motor manufacturing companies, the railroads, the packing industry, etc., and reach into medium and smaller industrial and commercial organizations by the scores of thousands throughout this hemisphere and the rest of the world.”

This makes it all the more hard to fathom how all of this could essentially disappear in a matter of a few years.

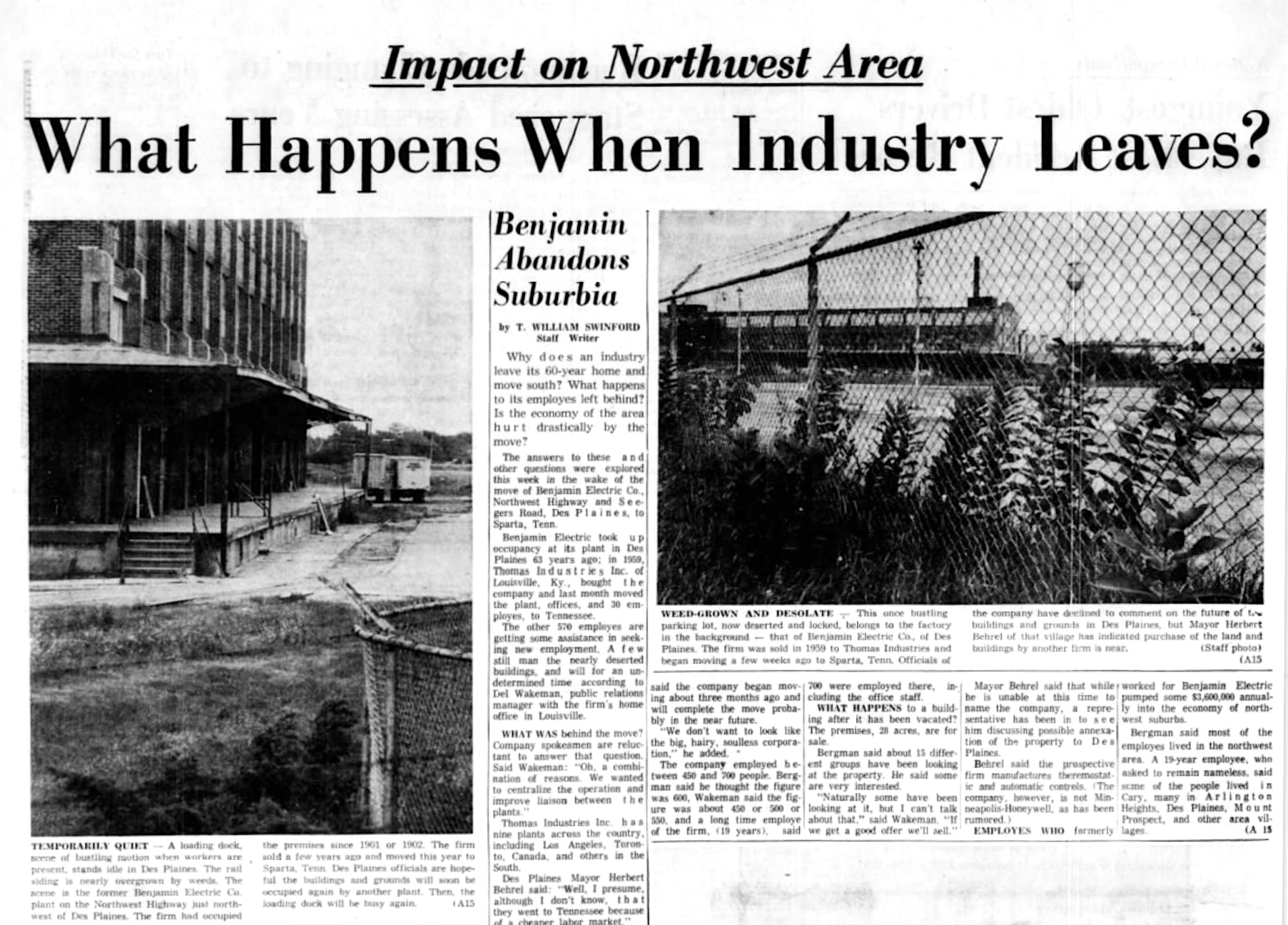

In 1957, Hoyt Steele resigned his post as company president to follow a more lucrative track with General Electric. His replacement, John R. Bartizal, had years of service with Benjamin Electric, but perhaps a greater willingness to listen to potential offers for the firm. The right offer came the following year, it turns out, as Thomas Industries of Louisville, Kentucky, acquired the entirety of the Benjamin Electric MFG Co. operation, transforming it into a division of its existing lighting equipment business.

John Bartizal stayed on as manager of the Benjamin division, and employees in Des Plaines were told business would continue as usual. Some believed it, many doubted it, nobody felt great about it.

In 1963, after years of red flags, Thomas Industries finally announced its intention to consolidate its manufacturing, which would include closing the Benjamin Electric plant in Des Plaines and moving the diminishing brand to Sparta, Tennessee. The deed was done by 1964, leaving 570 remaining Illinois workers out of a job.

Other companies drifted through the abandoned Benjamin plant over the next few decades, but the last surviving buildings from the complex were leveled and replaced by 2007. The last howler had sounded.

SOURCES

“Benjamin Electric Manufacturing Company” – incorporators, Chicago Tribune, April 11, 1901

Cause and Effect – Benjamin Electric Sales Book, 1919

“Benjamin Electric Mfg. Co.” – bonds for sales, Chicago Tribune, July 2, 1922

“Reuben B. Benjamin” – Electrical World, Vol. 81, No. 22, June 2, 1923

Benjamin Electrical Products, Catalog No. 24, 1925

“Benjamin Electric MFG Co., Petitioner, v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, Respondent” – Reports to the United States Board of Tax Appeals, Vol. 6, 1927

“Next to Edison: Can You Name the Ten American Inventors with the Greatest Number of Patents?” – Santa Ana Register, May 4, 1930

“Benjamin Electric Net Loss $816,274” – The Times (Munster, IN), June 16, 1932

“R. B. Benjamin, Head of Electric Company, is Dead” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 27, 1933

“Open Coach Line to Benjamin Electric Plant at Des Plaines” – Arlington Heights Herald, March 1, 1935

“We, of Benjamin Electric, are Helping to Build the Invasion Fleet” – ad in Arlington Heights Herald, Aug 27, 1943

“Benjamin to Build Laboratory” – Cook County Herald, June 15, 1945

“Benjamin Employees Get Bonus Checks at Christmas Party” – Arlington Heights Herald, Dec 21, 1945

“Many of Your Neighbors are Helping to Re-Light America” – ad in Chicago Tribune, Dec 29, 1946

“Benjamin Electric and Union Reach Agreement” – Arlington Heights Herald, April 11, 1947

“Benjamin Electric Christmas Party” – Mount Prospect Herald, Dec 24, 1948

“Benjamin Electric Celebrates 50th Year with Open House” – Cook County Herald, June 8, 1951

Benjamin Fluorescent Lighting Systems (Catalog), 1952

“Statement of Hoyt P. Steele, Executive Vice President, National Electrical Manufacturers Association,” Congressional Hearings on Taft-Hartley Act Revisions, 1954

“Thomas Industries Acquires Illinois Lighting Producer” – Courier-Journal (Louisville, KY), Nov 14, 1958

“What Happens When Industry Leaves?” – Arlington Heights Herald, Aug 20, 1964

“Small Things Forgotten: Domestic Electrical Plugs and Receptacles, 1881-1931” by Fred E. H. Schroeder, Technology and Culture, Vol. 27, No. 3, July 1986

“Benjamin Electric Plant Gave Way to New Industry, Homes” – by Brian Wolf, patch.com, May 15, 2012

“Des Plaines Honors WWII Women, Children” – Chicago Tribune, Feb 26, 2015

I have acquired 9 beautiful pendant lights made in England patent 718503/4/5, Benjamin. Can anyone guide to help me understand when these were made

I’m looking for photos of the cluster fixture Pat 1903. Esp. The 6 light, 5 around & 1 down with the 1 3/4″ HOLOPHANE shades & the 15″ big shade. Thank you.

Tengo una bocina con estás características me podrán dar información de que año será

Benjamín Electric MFG.CO

NO.8299A

INDUSTRIAL SIGNAL

RES.OF COILS220

Voltaje 110 60

CURRENT 17

Antemano muchas gracias y una disculpa

Thank you so much for this exhaustive article about my great-grandfather and his many achievements! It was so nice to stumble upon it!

I quite agree with my esteemed cousin Brooks. Well done, and thank you for this fine research into the largely unsung story of our great-grandfather, Reuben Berkeley Benjamin.