Museum Artifact: Playskool Crib Rail Boat Toy, c. 1960

Made By: Playskool Manufacturing Company, 1750 N. Lawndale Ave. [Humboldt Park]

“Next to baby-sitting grandmothers, the stylized wooden toys made by a Chicago firm called Playskool Manufacturing Co. may well be the greatest parent-savers of the age. Two-year olds have been known to play with a Playskool gadget for up to fifteen minutes without once bothering mommy or daddy—and that is about as long as any toy, or even the box it came in, can possibly hold the interest of a pre-school child.” —Newsweek, 1962

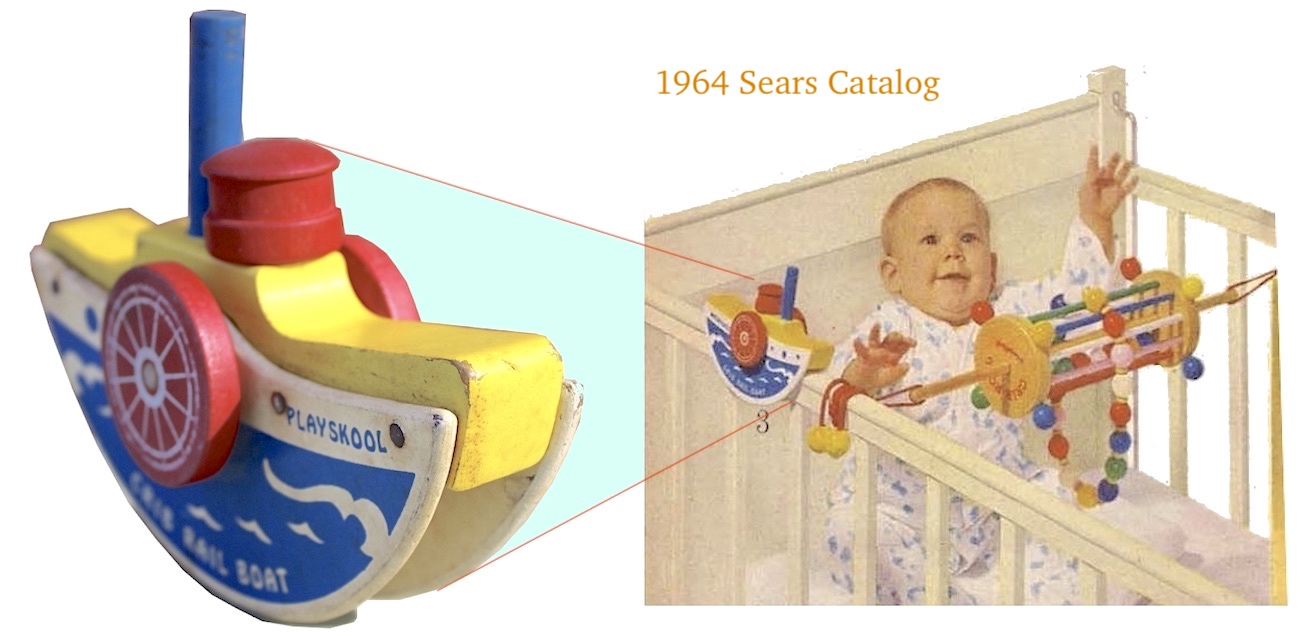

If the Playskool “Crib Rail Boat” in our museum collection looks vaguely familiar, it might be channeling a hazy recollection from your own babyhood, when a few bright primary colors and a spinning wheel could provide all the entertainment and educational value you needed.

For nearly a century, the distinctive pre-school toys of the Playskool line have helped create similar formative experiences for millions of youngsters, not to mention millions in profits for the various purveyors of the brand. Unfortunately, when it comes to the infancy of the business itself, the details are every bit as fuzzy as a childhood memory.

According to the official Playskool corporate website—operated by its current parent company, Hasbro—“two women in Wisconsin” launched the enterprise back in 1928—“one named Lucille King, the other unknown.” As former school teachers, King and her partner are credited with “starting their own company that made toys inspired by experiences in their classrooms.”

Considering the enormous success that followed, one might presume that we’d know a bit more about these visionary educators-turned-entrepreneurs. Instead, one of the women was forgotten completely, and the other, Lucille King—despite being inducted posthumously into the Toy Industry Hall of Fame in 2021—remains a mystery in her own right; seemingly without a single photograph, quote, or newspaper clipping to memorialize her alleged role in creating an American toy empire.

It certainly wouldn’t be unusual for a woman’s accomplishments to be pushed to the periphery in her own time, only to be recognized later. But in this case, a little deeper research reveals that the first Playskool products actually pre-date Miss King’s involvement in the business altogether. And while evidence does confirm her role as a sales representative with the company in the 1930s, the popular narrative of Lucille King as a “founder” or “mastermind” of Playskool has all the earmarks of a retro-fitted mythology; with the first versions of that account not appearing until the 1970s, after Milton Bradley had purchased the business.

Whatever the facts of its inception, Playskool’s commercial breakthrough didn’t really come in its early years anyway. It was during World War II, when functional wooden toys filled the void left by metal rationing, that national notoriety and profits climbed. By then, Playskool had an enthusiastic and savvy new Chicago ownership team, along with a big factory in Humboldt Park to bring items like the Crib Rail Boat to the rug-rats of America.

[As described in a Sears catalog, the Crib Rail’s Boat’s “paddle wheel spins so the boat slides along the rail of a playpen or crib. Delights and intrigues. Also rocks on floor. $1.39”]

History of Playskool, Part I: The Home Kindergarten

It’s pretty safe to say that Playskool was born in Milwaukee and raised in Chicago. It’s just the players involved and the timeline of events that have become obscured across decades of copy-pasted blurbs in “toy collector” books.

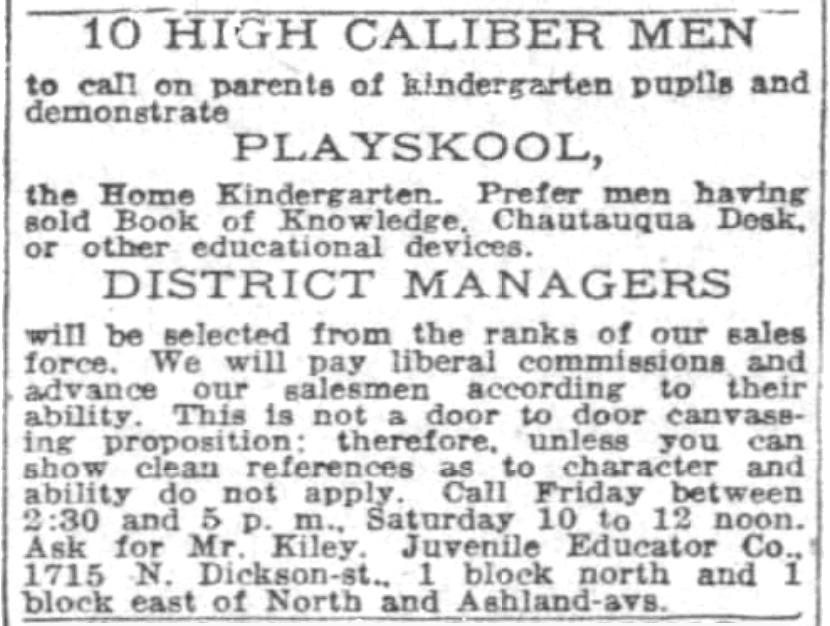

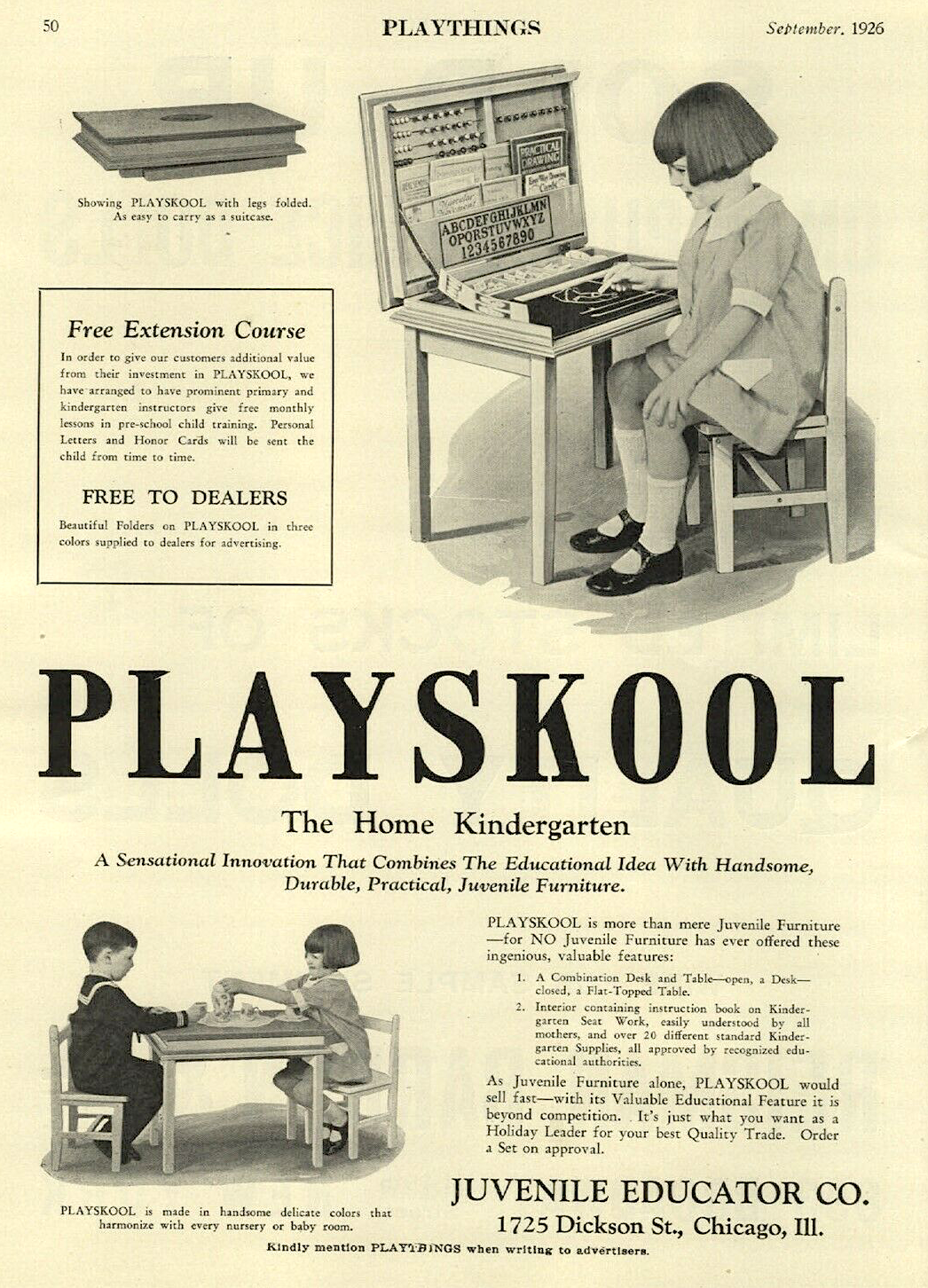

The two earliest references we could find to the brand name “Playskool”—with that familiar intentional misspelling—both come from the month of September, 1926. One is a noteworthy full-page ad in the trade magazine Playthings; and the other is actually a small classified ad in the Sept. 17 edition of the Chicago Tribune, seeking “10 High Caliber Men” to help demonstrate “Playskool, the Home Kindergarten” to parents of small children.

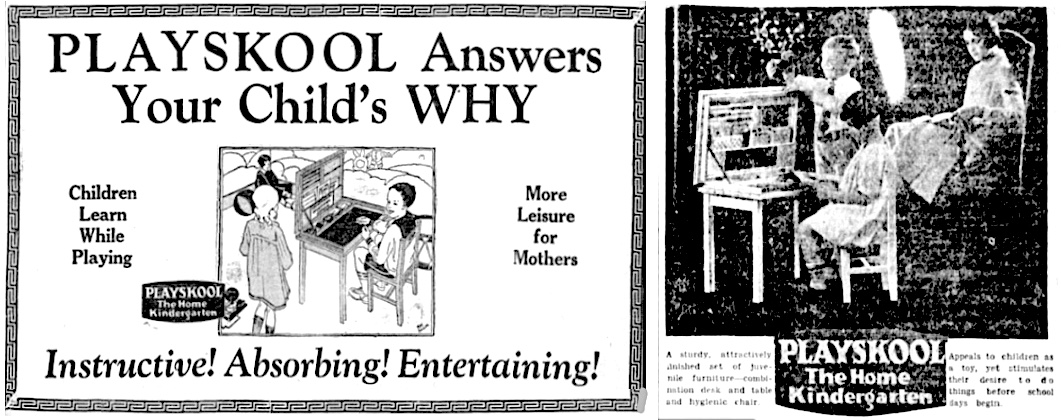

From these early promotions, it’s clear that Playskool was originally a single product—an “artistically furnished” desk-table and chair equipped with “specially adapted kindergarten material,” i.e., wood blocks, crayons, etc. “A sensational innovation,” claimed the magazine ad, “that combines the educational idea with handsome, durable, practical, juvenile furniture.”

Interestingly, both 1926 ads also associate the product with a Chicago business called the Juvenile Educator Company, headquartered at 1715 N. Dickson Street [the Tribune post tells respondents to “Ask for Mr. Kiley” when they get there]. But as best we can tell, this company is never mentioned again in relation to Playskool products, or anything else for that matter—suggesting it may have been little more than a pop-up operation of sorts. The actual inventor and original dealer of the clever little at-home learning lab was, more likely, an independent contractor by the name of Harry A. Hansen, a Norwegian-born, Milwaukee-based craftsman who seems to have been largely forgotten by America’s toy historians.

[One of the first ads for Playskool, from the September 1926 issue of Playthings]

Hansen was 36 years old in 1926, and was raising a son, Rex, with his wife Florence. We don’t know what his specific line of work had been up to this point, but he appears to have thrown himself fully into the Playskool project, investing both in the manufacturing and sale of the product (the word “Playskool,” incidentally, may have been inspired by the Norwegian word for school, “skole,” rather than stylized purely for branding sake).

The most detailed—and perhaps only existing—account of Hansen’s creation of “The Playskool” comes from a 1929 issue of the American Lumberman, which relates how Hansen “became disgusted” when a poorly built toy blackboard supposedly fell from his son’s bedroom wall and broke the poor kid’s arm. After this, Harry “set himself to the task of inventing a new and better blackboard—that would not fall and break the arms of young sons. . . . As he studied the question, he came to the conclusion that his son needed not simply a blackboard but a fairly complete school equipment, with materials to make his own toys, all gathered together into one unit. It must be attractive but usable, but above all it must be substantial and entirely safe.

“In the form which Mr. Hansen finally decided met the requirements, the new creation appeared to be, at first glance, only a child’s table and chair attractively painted. But the table top was hinged at the back, and upon raising the lid one could see underneath subdivisions most ingeniously arranged to accommodate many different kinds of playthings to delight a child. . . . This device met with such immediate and enthusiastic response from his son that Mr. Hansen decided to make more of them and put them on the market.”

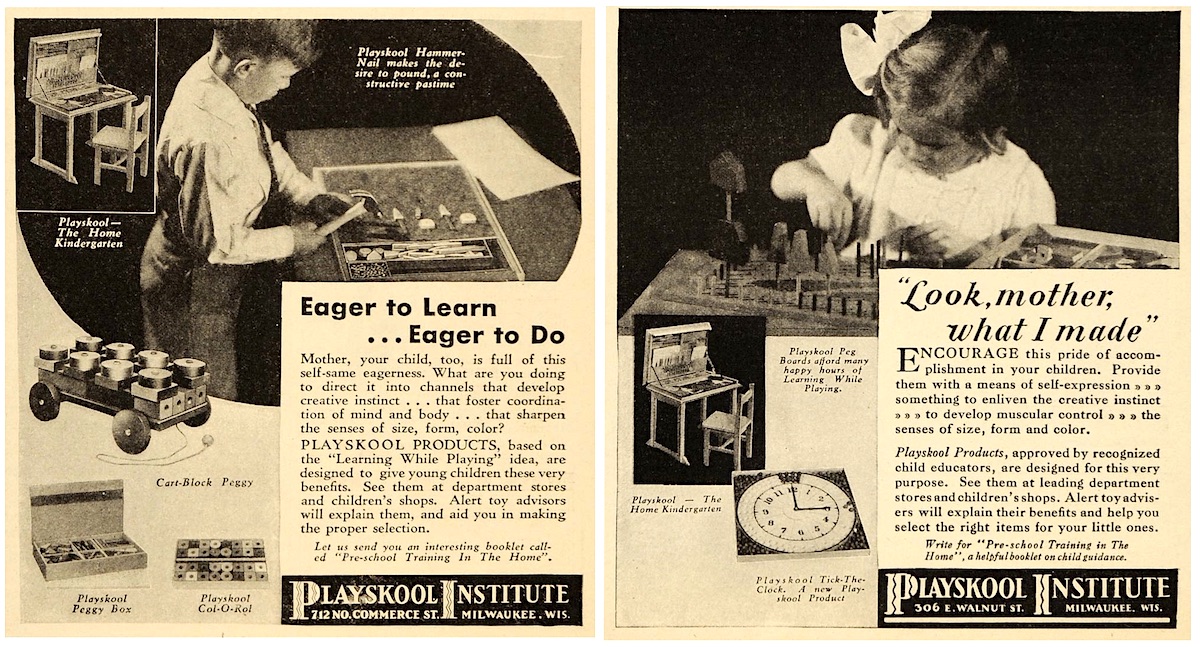

[1928 advertisements for the original Playskool desk, “The Home Kindergarten”]

One can take this story with some degree of suspicion—for one thing, the writer gets Hansen’s middle initial wrong (listing it as “H” rather than “A,” despite firm evidence of the latter), and for another, it seems unlikely that Harry’s son Rex, who was 14 years old in 1927, would have been getting crushed by falling toy chalkboards at his age. But we can trust a bit more of the second half of the article, which recounts how Hansen’s scuffling DIY venture found new life when an unlikely partner entered the story.

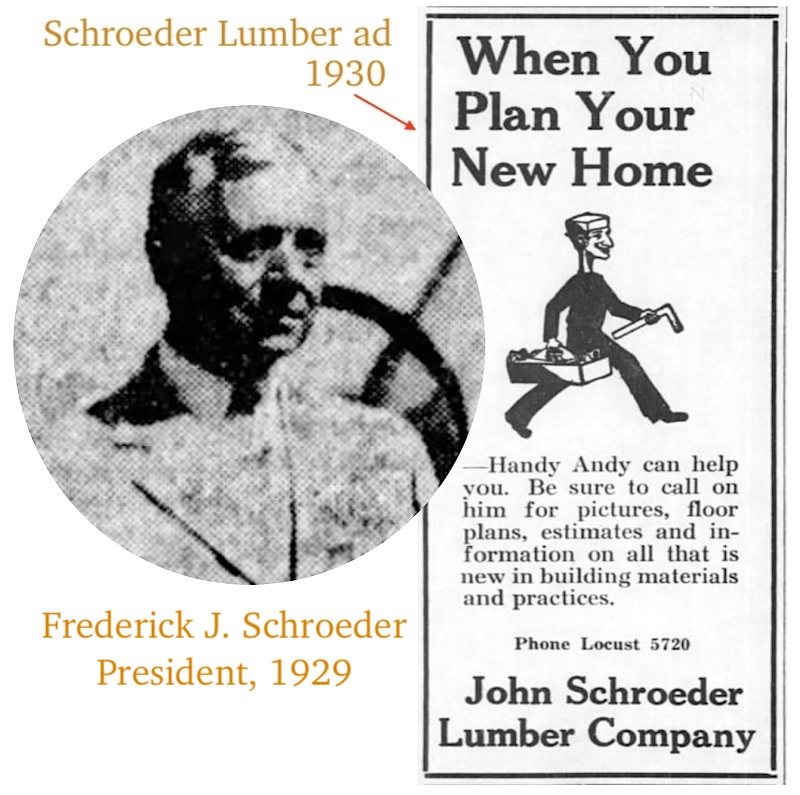

“News of [Hansen’s] enterprise, which had been carried on in Chicago, reached the John Schroeder Lumber Co., of Milwaukee, and its officials realized that here was an unusually good idea for converting lumber into cash. So the Schroeder company took over the manufacture and sale of the little desks, with Mr. Hansen supervising the work. Others on the engineering staff aided him to improve on the invention, in design and equipment.

“. . . Playskool, as the desk is now called, is so designed as to allow room for many materials. When the hinged top is raised it becomes the back of the desk, with compartments for books and pictures. It also has wires strung across it, to hold colored wooden beads which will make mathematics real to the young mind. The alphabet is attractively printed across the bottom of the cover, so placed that the child will be looking at it all the time he is sitting at the desk.”

“. . . Playskool, as the desk is now called, is so designed as to allow room for many materials. When the hinged top is raised it becomes the back of the desk, with compartments for books and pictures. It also has wires strung across it, to hold colored wooden beads which will make mathematics real to the young mind. The alphabet is attractively printed across the bottom of the cover, so placed that the child will be looking at it all the time he is sitting at the desk.”

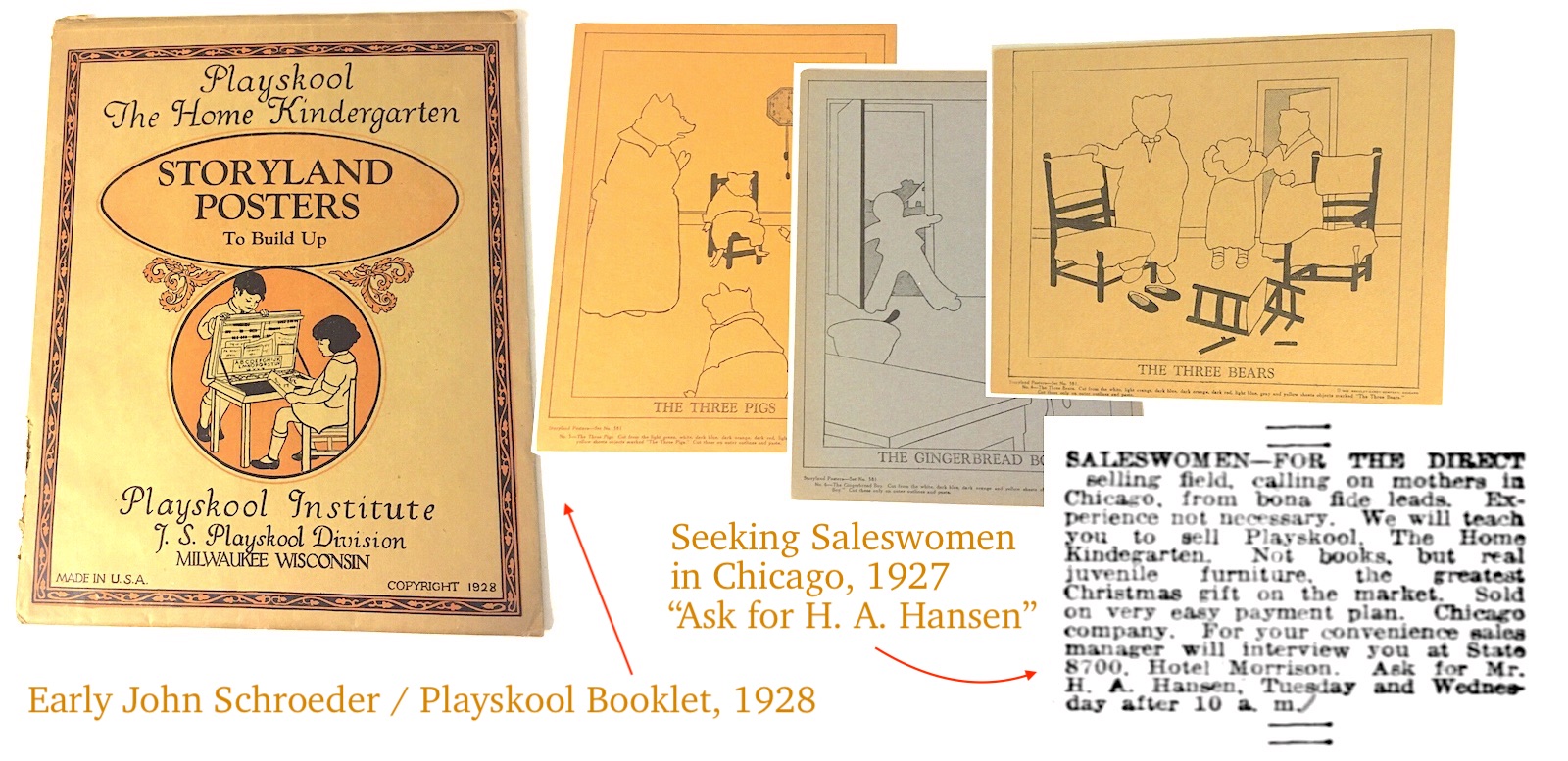

This whole “Home Kindergarten” idea was truly the bee’s knees, as folks would have said back then. By October of 1927, Frederick J. Schroeder, president of the John Schroeder Lumber Company, had already approved the creation of a “Playskool Division” to mass produce it, and though based in Milwaukee, the company carried on a presence in Chicago, recruiting salesmen and women from an office at 450 E. Ohio Street. In November of the same year, ads in the Chicago Tribune find Harry Hansen himself training potential Playskool saleswomen from a makeshift office in the Hotel Morrison.

During this same time period, Playskool’s supposed founder, Lucille M. King, was not yet even an employee of the budding business. When she traveled to spend Christmas of 1927 with her mother in Appleton, Wisconsin, the local paper directly identified her as a “teacher in Milwaukee.” By the following year, however, we can begin to trace how this unassuming 34 year-old educator might have found her way into an entirely new line of work . . . and eventual status as a toy industry Hall of Famer.

Part II. The Institute

Starting around the autumn of 1928, a large Playskool promotional push was in full swing across the Midwest, and something new had been added to the campaign. The Playskool desk was now backed by a supposed “council of educators” known as the “Playskool Institute,” which had its own office on Commerce Street in Milwaukee. Essentially, the Schroeder Lumber Company had cooked up a way to legitimize the Playskool desk by giving it—and other new products in development—the stamp of approval from an official-sounding educational body.

“Playskool measures up to the educational ideas and ideals of prominent child psychologists who have devoted their lives to the study of child training,” read one 1928 newspaper ad. “It has their hearty endorsement because it conforms to present day tendencies in the teaching of children—with special emphasis on pre-school children.”

“Playskool measures up to the educational ideas and ideals of prominent child psychologists who have devoted their lives to the study of child training,” read one 1928 newspaper ad. “It has their hearty endorsement because it conforms to present day tendencies in the teaching of children—with special emphasis on pre-school children.”

A 1929 advertisement more specifically describes the new “Playskool Institute” as a “group of educators, authorities on child training, practical teachers and parents, all working together with a commercial organization to originate, produce and distribute play material in which is incorporated the basic idea of ‘learning while playing.’”

As far as we can tell, there was never a single ad that described the Playskool Institute as the brainchild of Lucille King or any other specific educator. The greater likelihood, based on the evidence, is that King and several other local Milwaukee school teachers were hired by the John Schroeder Lumber Company as advisors and sales reps during the creation of the “Institute.” Even if she didn’t hatch the idea herself, though, there’s no doubt that King was an important figure in Playskool’s development over the next 15 years.

[The Milwaukee mailing address of the Playskool Institute jumped around several times between 1928 and 1930, as evidenced in these ads from the period, which show both a 720 North Commerce Street and a 306 W. Walnut Street address.]

III. King in Her Court

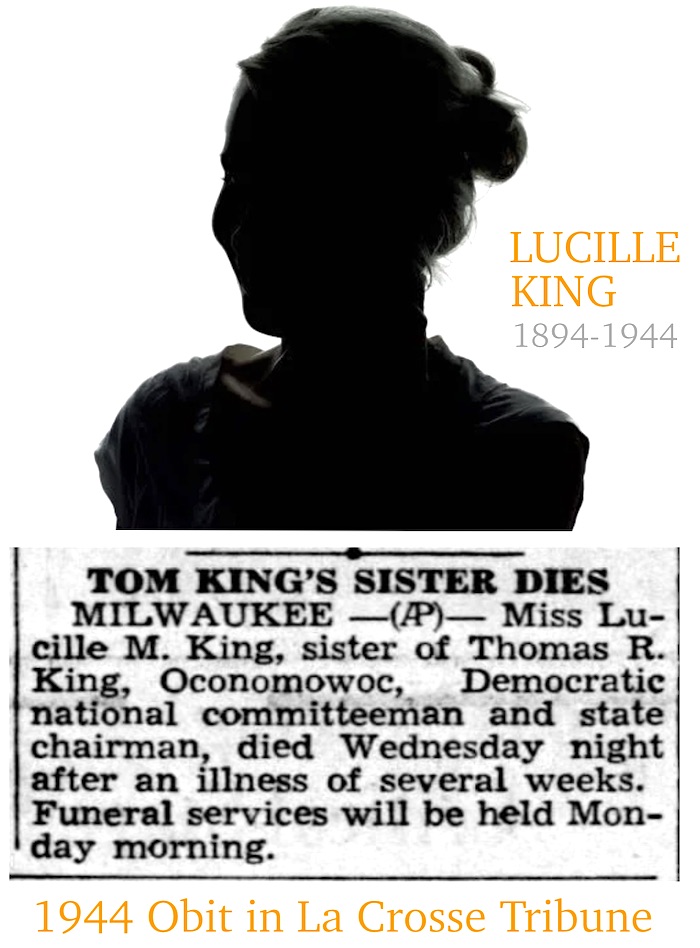

Lucille M. King was born in 1894 in the small town of Chilton, Wisconsin, between Green Bay to the north and Milwaukee to the south. The daughter of German immigrants, she grew up with five brothers and one sister, the latter of whom—Genevieve—also became a school teacher. One of her brothers, George, joined the military at Camp Funston in Kansas during World War I, and died there—one of the earliest victims of what would come to be known as the Spanish Flu. Another brother, Thomas, later served as Chairman of the Democratic Party of Wisconsin during the early 1940s. He was a prominent enough politician that some obituary headlines following Lucille King’s death in 1944 simply read: “Tom King’s Sister Dies.”

That insulting contextualization of her life—along with the fact that her own gravestone spells her name Lucile (with one less “L” than every other mention we could find)—further supports the idea that Miss King was not a recognized figure even in her own time, and that the notion of her holding a leadership role with Playskool may have been a half-truth that turned into a posthumous narrative decades later (perhaps cooked up by a marketing department in need of an agreeable corporate origin story).

That insulting contextualization of her life—along with the fact that her own gravestone spells her name Lucile (with one less “L” than every other mention we could find)—further supports the idea that Miss King was not a recognized figure even in her own time, and that the notion of her holding a leadership role with Playskool may have been a half-truth that turned into a posthumous narrative decades later (perhaps cooked up by a marketing department in need of an agreeable corporate origin story).

Our best guess is that King was hired by the John Schroeder Lumber Co. in 1929 as one of the first members of the Playskool Institute. She never married, and with the freedom that entailed—along with her family’s potential political connections—Lucille might have seen the new job as a unique opportunity to do something meaningful, and profitable, beyond the classroom.

In the 1930 census, King is listed as a “Saleswoman” with a “Wholesale Lumber Products” company, pretty well confirming her entry into the Playskool family—although it is notable that she chose to identify herself as a sales person rather than an executive or product developer. At the time, she was also a lodger in the home of Jerome and Alice Reichert on 21st Street in Milwaukee.

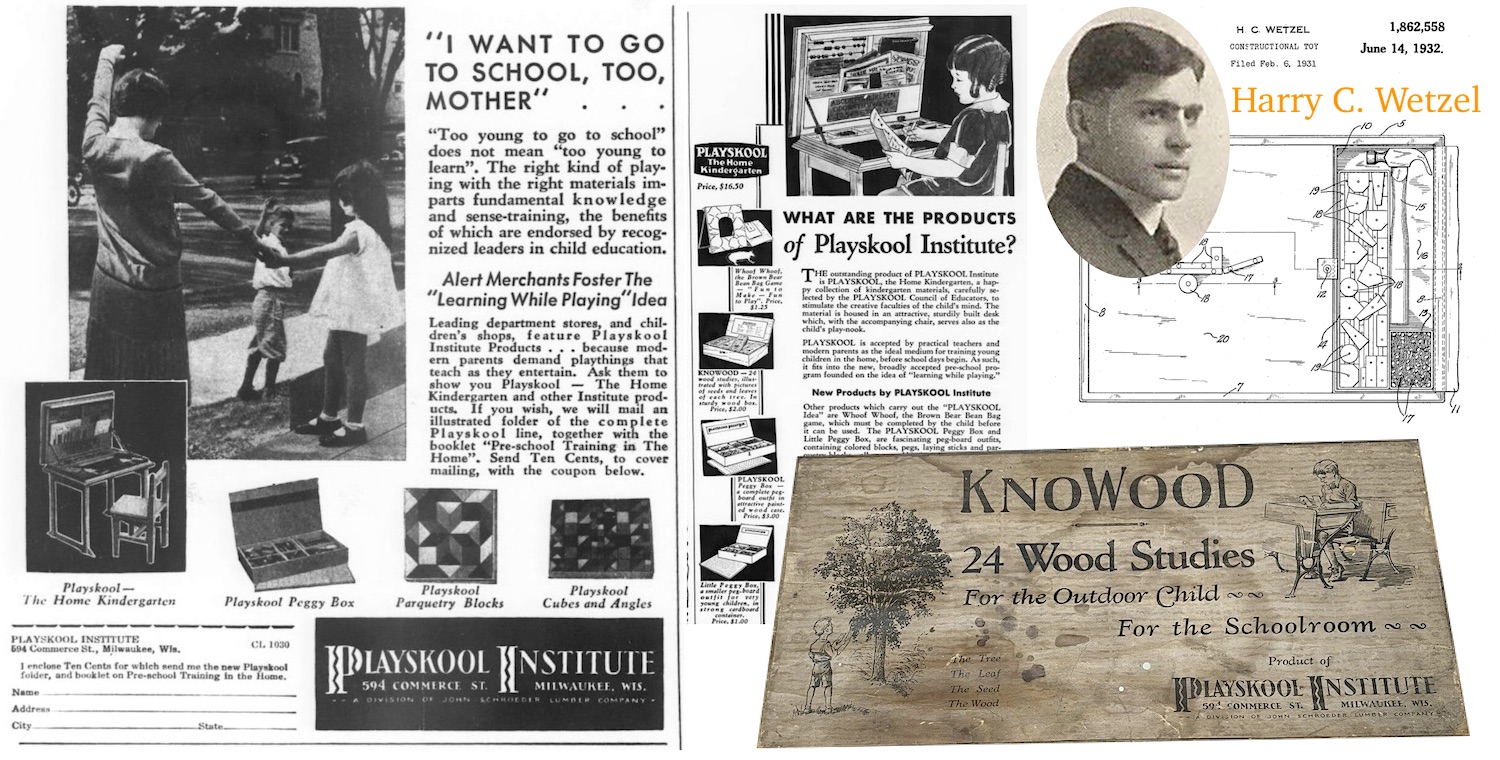

Despite the economic challenges of the early 1930s, Playskool was trying its best to expand, with the original Hansen desk now joined by the “KNOWOOD” educational kit, the Playskool “Peggy Box,” and “Whoof Whoof,” aka the “Brown Bear Bean Bag Game.” According to one ad, “Playskool is accepted by practical teachers and modern parents as the ideal medium for training young children in the home, before school days begin.”

In 1931, the Playskool Institute officially evolved from a division of John Schroeder Lumber into its own incorporated business in Milwaukee, “dealing in toys, mechanical goods, woodenware, earthenware, clay products, etc.” When the creation of Playskool Institute, Inc. was announced on October 10, 1931, however, neither Harry Hansen nor Lucille King were listed among the incorporators. Instead, there were three men from within the Schroeder Lumber ranks—E. J. Schickel, Benjamin Springer, and Harry C. Wetzel. Springer had developed the KNOWOOD kit, and Wetzel was one of the men who helped improve Hansen’s original Playskool desk, eventually patenting a similar educational “constructional toy” kit in 1932, which taught pre-school children how to safely use hammers and nails—a necessary skill, I suppose, for toddlers of the Depression.

The name Harry Hansen is never mentioned again in Playskool lore, and by the time of his death in 1936 at the age of just 46, the industry already seems to have collectively forgotten his contributions.

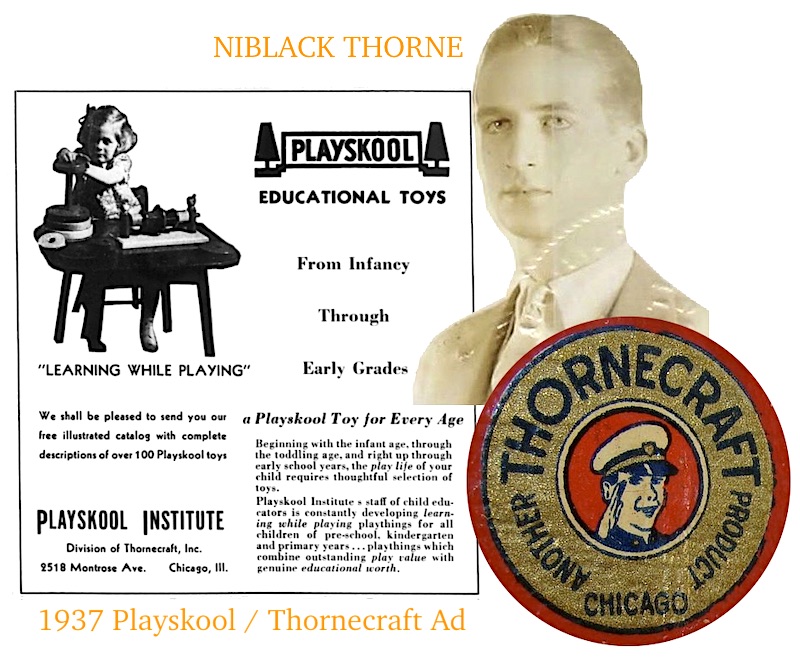

Lucille King managed a slightly better fate. In 1935, when Schroeder Lumber started sinking in the depths of the Depression and sold Playskool to a Chicago toy company called Thornecraft, Inc., she managed to stay on as a sales rep, eventually spending more and more of her time in Chicago as a result.

Thornecraft, which owned a factory at 2518 W. Montrose Ave., was operated by a “socially prominent” Chicago figure named Niblack Thorne. His mother, Narcissa Niblack Thorne, was a well known artist and designer of intricate miniature rooms (aka “Thorne Rooms”)—many of which are still on display at the Art Institute of Chicago. By comparison, her son’s business was a bit less celebrated—in 1935, for example, Thornecraft’s attempt to cash in on a national balloon racing fad led them to sell a product, the Buck Rogers Strat-o-Sphere Dispatch Balloon, that came packaged with “two harmless chemicals” to form an “anti-gravity gas.” Turns out those chemicals actually included dangerous levels of sulphuric acid, resulting in a violation of the Federal Caustic Poison Act and legal intervention by the U.S. government.

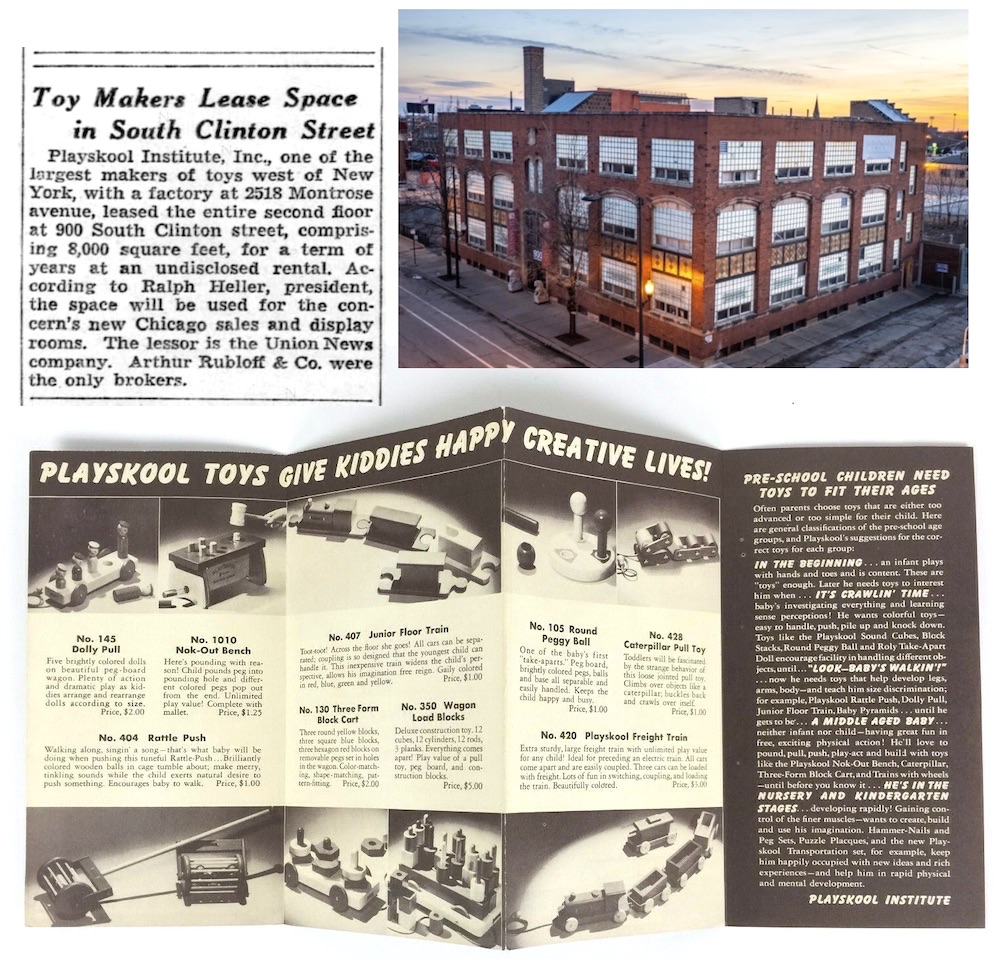

After a few years, perhaps for the better, Thornecraft lost interest in its middling Playskool department, abandoning the division and putting it up for sale. It became a bit of a “loose football” for a while after that. A Chicago businessman named Ralph Heller was in charge by 1938, opening a Playskool office at 900 S. Clinton Street and very nearly cutting a deal to move the company’s factory workforce (about 75-100 people) to Sheboygan, Wisconsin, a year later. But something went amiss, and the Heller regime swiftly gave way to executives from Chicago’s Joseph Lumber Company instead.

After a few years, perhaps for the better, Thornecraft lost interest in its middling Playskool department, abandoning the division and putting it up for sale. It became a bit of a “loose football” for a while after that. A Chicago businessman named Ralph Heller was in charge by 1938, opening a Playskool office at 900 S. Clinton Street and very nearly cutting a deal to move the company’s factory workforce (about 75-100 people) to Sheboygan, Wisconsin, a year later. But something went amiss, and the Heller regime swiftly gave way to executives from Chicago’s Joseph Lumber Company instead.

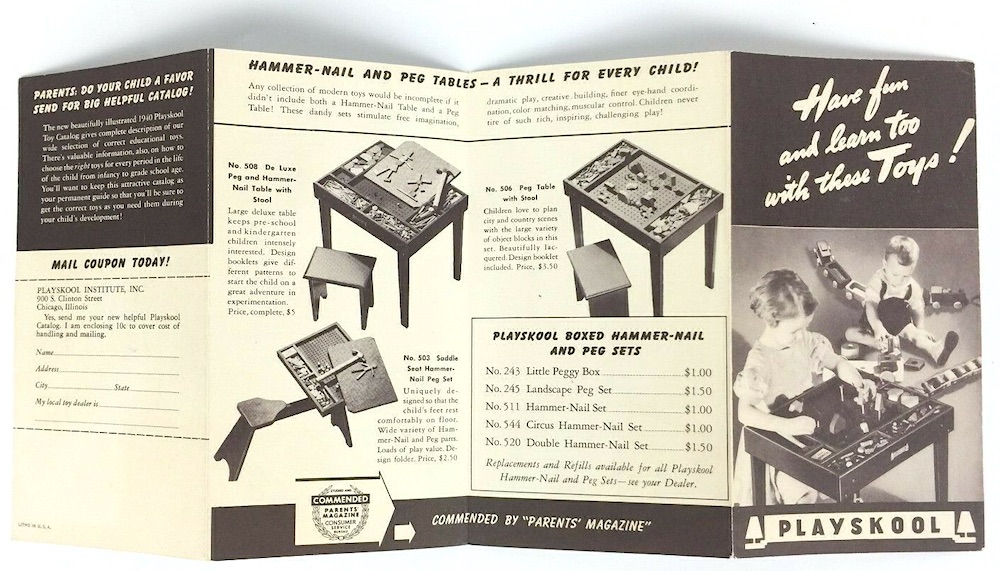

Heading into 1940, Playskool was still in flux. The company had virtually zero ad budget, and its catalog of toys had pretty well plateaued with a few dozen offerings: among them the popular “Hammer-Nail Set,” along with various wooden pull trains, peg boards, and stacking blocks.

Lucille King was probably having her doubts about the survival of the business at this point, but a pair of savvy saviors were about to turn the ship around.

[Playskool briefly occupied the second floor of the building pictured above at 900 S. Clinton Street from the late 1930s into the early 1940s; the same time period this small catalog flyer was published]

IV. Manny and Bob

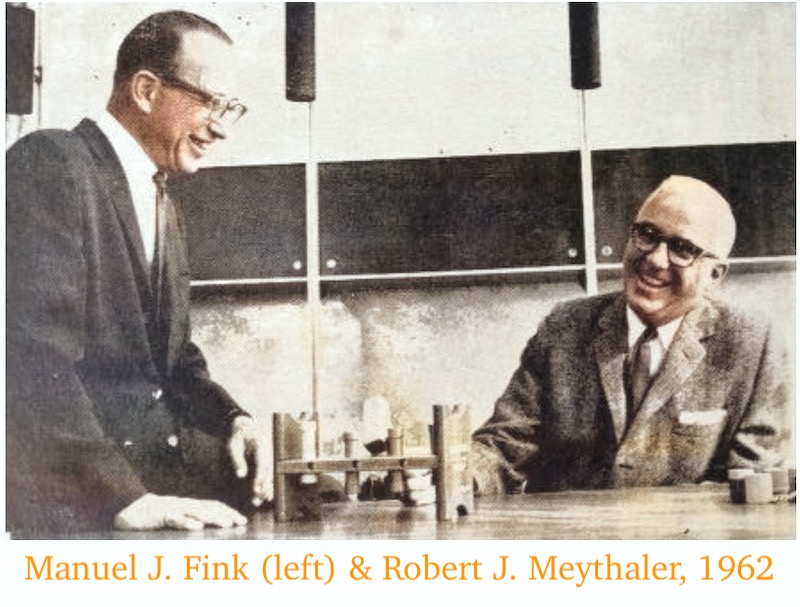

Between 1938 and 1940, two young businessmen were brought into the Playskool offices in a last-ditch effort to give the Institute some direction. The first was Manuel Fink, an experienced Chicago department store buyer, and the second was Robert J. Meythaler—another Wisconsin native who was both an accomplished insurance accountant and a keen amateur woodworker. It’s not entirely clear if they were first hired by Niblack Thorne, Ralph Heller, or Harry Joseph of the Joseph Lumber Co. The important thing is that Fink and Meythaler saw a potential in the Playskool products that those other fellows didn’t quite recognize.

With a battle plan in place, the re-organized Playskool Manufacturing Company acquired a new factory space in 1941 at 1750 N. Lawndale (former plant of the Harmony music instrumental company), and by the following year—in the midst of World War II—Fink and Meythaler saw strong enough returns that they decided to buy out the business with their own capital, with Meythaler taking over as president and Fink as VP.

With a battle plan in place, the re-organized Playskool Manufacturing Company acquired a new factory space in 1941 at 1750 N. Lawndale (former plant of the Harmony music instrumental company), and by the following year—in the midst of World War II—Fink and Meythaler saw strong enough returns that they decided to buy out the business with their own capital, with Meythaler taking over as president and Fink as VP.

According to Frank and Theresa Calpan’s 1974 book, The Power of Play, “Bob Meythaler created many of the first original wooden Playskool preschool educational toys in his basement workshop. In those days few toy shops would make room on their shelves for the abstract, shape-fitting toys and toddler-geared push-and-pull toys of this pioneering company. It took years of patient cajoling and hard selling to get retailer support for ‘educational toys.’”

The timing of Playskool’s re-emergence was also fortuitous—if one can use such a term considering the circumstances.

“. . . World War II decimated the metal toy industry in the United States,” the Caplans explain in their book, “and the wooden toy companies like Holgate, Playskool, Fisher-Price, and Childhood Interests were in great demand. For the first time, Americans discovered the play value inherent in a carefully designed and manufactured educational toy. Playskool and Fisher-Price grew tremendously.”

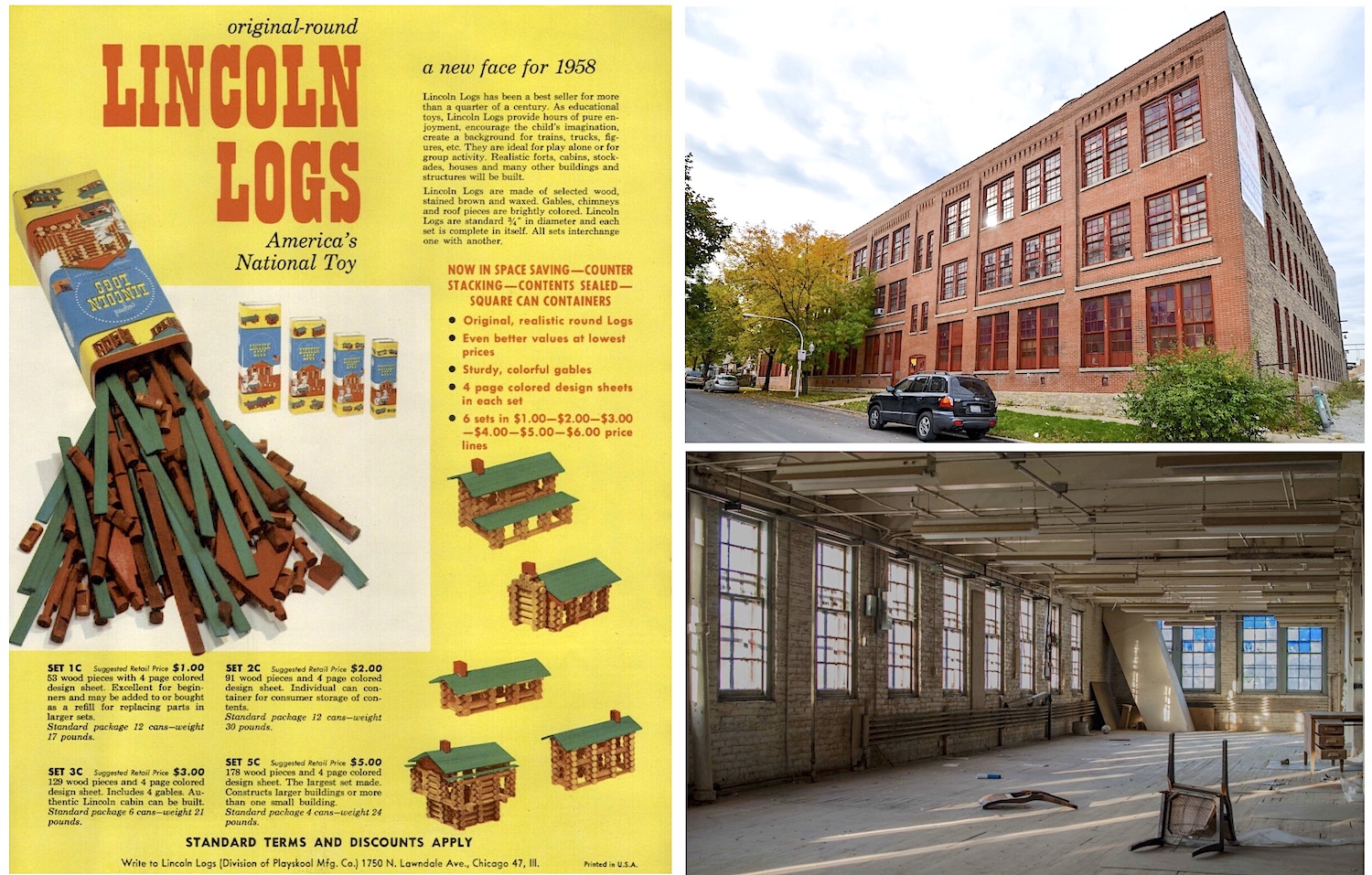

The sales spikes of the early 1940s not only helped Playskool survive, it gave Meythaler and Fink some industry sway, and the ability to expand. In 1943, they made their first big acquisition, taking over production of another popular wood toy, Lincoln Logs, from the J-L Wright MFG Co. (an old myth claims that Lincoln Logs inventor John Lloyd Wright, son of Frank, sold his business to Playskool for just $800, but that’s almost certainly hogwash).

With Playskool toys and Lincoln Logs both emanating from the same Humboldt Park factory, the glory days of the business had officially begun. And fortunately, some of the longstanding holdovers from the Playskool Institute were there to see it; including Lucille King, who was promoted to the role of Midwestern Sales Manager, representing both the Playskool and Lincoln Logs brands. She was at the height of her career when an unknown illness took her life in 1944 at just 49 years of age.

[While it’s generally remembered as the former Lincoln Logs factory, the building above at 1750 N. Lawndale was also the primary Playskool plant through the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s]

V. The Right Toy for Every Age

“Toys are not just gifts . . . they are tools of play. As your child plays today, so will he work and live tomorrow!” —Playskool catalog, 1950

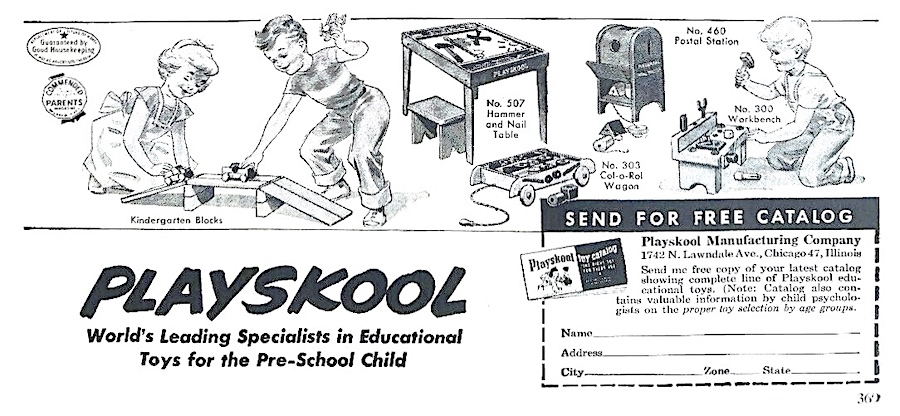

After the war, Meythaler and Fink’s next big move was to invest more into Playskool’s national ad budget, and to give the brand the sort of awareness originally envisioned back in the days of the Institute. No expense was spared, as Playskool promotions appeared in targeted publications like Parents, Redbook, and Today’s Health, as well as Life, Better Homes & Gardens, McCalls, etc.

After the war, Meythaler and Fink’s next big move was to invest more into Playskool’s national ad budget, and to give the brand the sort of awareness originally envisioned back in the days of the Institute. No expense was spared, as Playskool promotions appeared in targeted publications like Parents, Redbook, and Today’s Health, as well as Life, Better Homes & Gardens, McCalls, etc.

“Our toys are regularly inspected by psychologists and are tested in child psychology clinics,” Meythaler told the Tribune in a 1946 piece; one of the first to profile the company in much depth. “We try to build toys that teach a child coordination, develop his aptitudes for design and color, and stimulate his imagination while affording an outlet for his play energy.”

The company continued to segment its catalog in sections based on different age groups, with some toys optimized for infants, others for toddlers, and others for preschool and kindergarten age kids: hence, the slogan, “The Right Toy For Every Age.” This made logical sense, but was also a clever way to get parents invested in the idea of a “program” of toy buying that was strategic and rooted in education, rather than amusement.

“Watch your child’s development carefully and add new toys as new needs arise,” reads a 1950s Playskool sales flyer. “People often make the mistake of giving a child toys only at Christmas or on birthdays. This method of presenting a child with too many toys at one time often only confuses him. Give him toys regularly . . . with thoughtfulness, not merely generosity.”

There were 150 workers building Playskool toys at the Lawndale Avenue plant in 1953, and—despite the company’s association with wooden toys—plastic was now part of the production process, as well. By 1958, the firm owned additional factories in Hampshire, Illinois; Appleton, Wisconsin; and South Bend, Indiana.

1958 is also the year that Meythaler announced the acquisition of one of Playskool’s earliest wood-toy rivals, Holgate Toys—a former Philadelphia firm based at the time in Statesville, North Carolina. Holgate’s chief toy designer was a fellow named Jerry Rockwell, brother to arguably America’s most famous illustrator of the time, Norman Rockwell.

With quite a few iconic designs already to his credit, Jerry Rockwell was invited to join the Playskool team in Chicago, and he remained in that position into his senior years in the 1960s, overseeing popular classics like the drop-box post-office, the House That Jack Built, Wood-a-Motive trucks, the Tyke Bike, and various new lines of counting beads and pegboard sets.

“There are really no new ideas in toys,” a 72 year-old Rockwell told the Tribune in 1964. “A good designer takes other types of toys and gives them a new appearance and adds new play values. For example, we are now in the process of adding all kinds of sounds to toys—music, bells, rattles, tones. Up until three years ago, adults wanted kids’ toys seen and not heard! Pre-schoolers, however, enjoy sound. They begin to perceive different kinds of sound and thus take the first step in acquiring the long-ignored art of listening.”

“There are really no new ideas in toys,” a 72 year-old Rockwell told the Tribune in 1964. “A good designer takes other types of toys and gives them a new appearance and adds new play values. For example, we are now in the process of adding all kinds of sounds to toys—music, bells, rattles, tones. Up until three years ago, adults wanted kids’ toys seen and not heard! Pre-schoolers, however, enjoy sound. They begin to perceive different kinds of sound and thus take the first step in acquiring the long-ignored art of listening.”

Rockwell saw a lot of ways in which kids were actually a bit smarter than their parents when it came to an affinity for Playskool products. “Children can take apart toys that an adult can’t,” he said. “They can, also, with time, learn to put them back together. That is why we build our toys of hard, polished wood or of sturdy plastic. We want children to enjoy taking them apart and putting them back together, over and over again.”

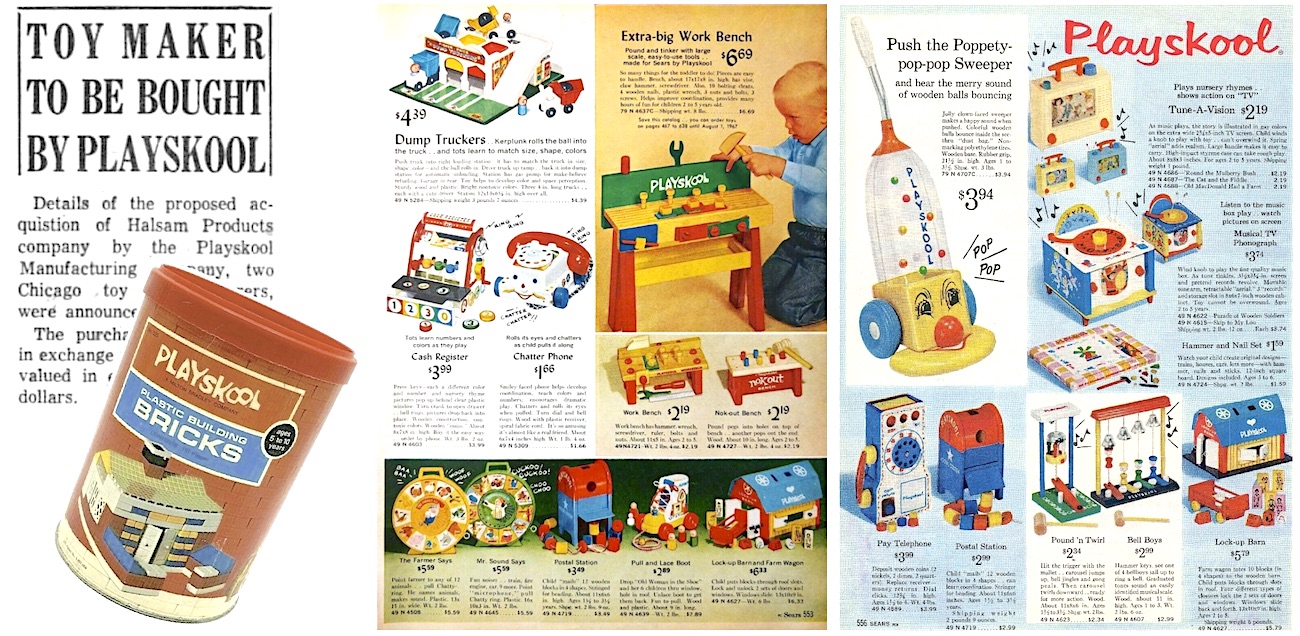

Playskool made another major acquisition in 1962, paying $3 million to take over the full product line of another Chicago toy institution, the Halsam Products Company. It was another perfect fit, as Halsam’s properties also included the Embossing Company, a leading maker of wood blocks, checkers, and dominoes.

Between 1960 and 1966, Playskool’s sales leaped from about $12 million annually to $23 million, and the workforce expanded to more than 600 in Chicago alone, split between the Lawndale Avenue factory and another plant at 3720 North Kedzie. Optimism for continued growth seemed built into the business model.

“We have approximately 4.5 million new potential customers a year,” president Manuel Fink told Newsweek in 1962. “That’s the national birth rate.”

The only challenge, perhaps, was the unpredictability of that particular clientele. “We’re going to pit our best creative minds and finest technological resources against the unlimited capacity of children to break toys with incredible speed,” chairman Robert Meythaler joked in the same Newsweek feature.

After more than 20 years in charge, Meythaler and Fink could look back with some measure of pride at what they’d built. Where Playskool had once represented a sort of novel, fringe concept in at-home education, by the 1960s, mainstream America had fully embraced many of the principles people like Harry Hansen and Lucille King had been promoting back in the ‘20s. Playskool seemed destined to remain a Chicago manufacturing powerhouse for generations to come.

VI. Profits, Loans and Protests

In 1966, Bob Meythaler was 53 years old and Manuel Fink was 57. They weren’t exactly at retirement age, but they weren’t spring chickens either. Without a clear second generation stepping into the business, the better move increasingly became obvious—to cash in on the substantial toy powerhouse they’d fostered together.

There were strong flirtations with General Mills to buy out the business in ’66, but as Playskool’s profits kept soaring, Meythaler and Fink stalled at selling too low. Finally, in the spring of 1968, a more fitting partner came into the picture, as Milton Bradley—one of the few bigger fish in the toy manufacturing sea—began merger negotiations. When the deal was completed, Playskool, Inc. ceased its 30-year run as a Chicago-owned business. Even as a division of the Massachusetts-based Milton Bradley Company, however, there remained some reason for encouragement among local Chicago workers.

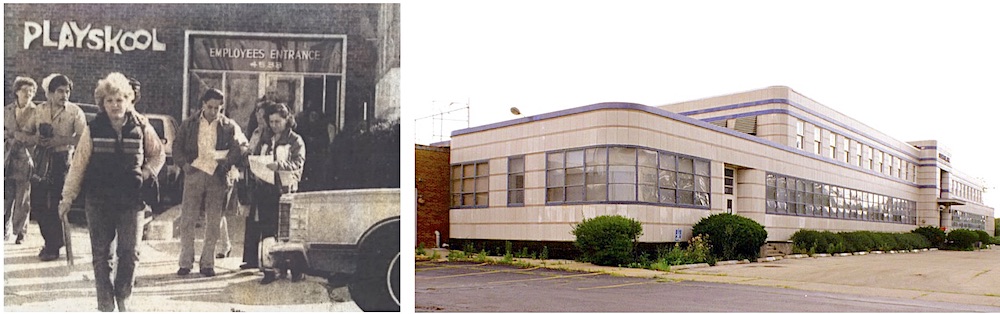

For a while, both the Kedzie Avenue and Lawndale Avenue plants remained in operation. Then, in the early 1970s, all Chicago manufacturing was consolidated into a sprawling facility at 4501-4545 W. Augusta Blvd—a former Motorola complex in West Humboldt Park. For a time, Playskool’s local employee count reached as high as 1,200.

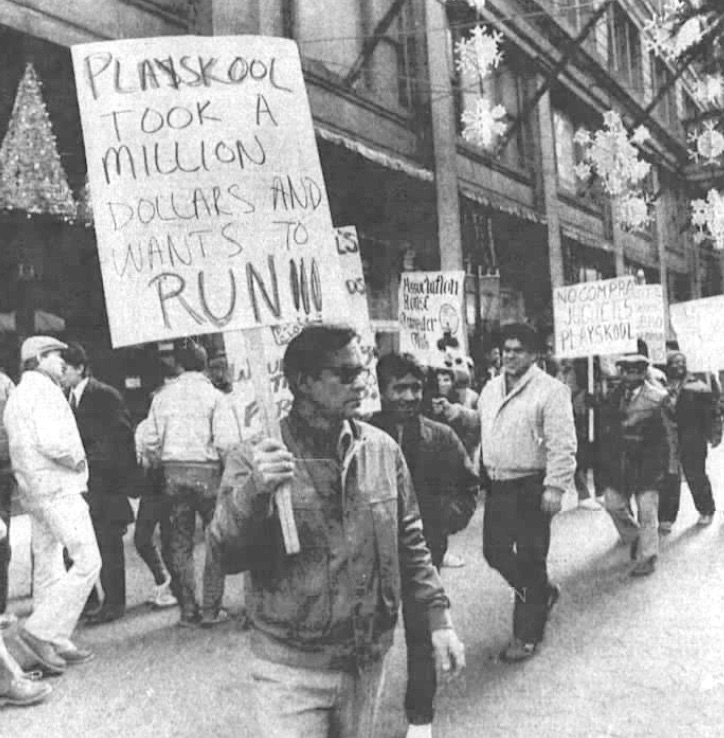

As the great exodus of Chicago factories continued later into the 1970s, however, those workers needed something to assure them that Playskool—and its Milton Bradley overlords—were committed to Chicago. They seemed to get that comfort in 1980, when City Hall gifted Playskool with a $1 million “IRB,” or Industrial Revenue Bond—which the company could pay back simply by agreeing to create more local jobs.

As the Tribune later reported, “Playskool, which had 1,156 jobs at the time, said it would use the money to create another 446 jobs. Instead, employment at Playskool has shrunk since then to about 700 [in 1984].”

[Left: Workers outside the Playskool plant entrance at 4533 W. Augusta Blvd., 1984. Right: A more recent view of the distinctive Streamline Moderne style facility that Playskool occupied from 1973 to 1985.]

This apparent mis-use of funds didn’t really come to light until the late summer of 1984, shortly after Milton Bradley was purchased by Hasbro. Within days of the deal, MB announced it would be shutting down Playskool’s last remaining Chicago plant on Augusta Blvd. and terminating all 700 employees—75-percent of whom were black or Hispanic, and 60-percent of whom were women.

Much of the rage that followed, both from employees and the wider community, stemmed from the fact that Playskool was posting record sales at the time, and hardly in need of cutting costs. “This company is making profits,” a union leader told the Tribune. “To see them close their damned doors and pull out is really disgusting.”

Milton Bradley execs, as well as Playskool president George Volanakis, claimed that the main problem was the condition of the 50 year-old factory, but nobody seemed to buy the explanation. For months, union workers and activists protested the factory closure and called for boycotts against Playskool, Milton Bradley, and Hasbro toys.

Milton Bradley execs, as well as Playskool president George Volanakis, claimed that the main problem was the condition of the 50 year-old factory, but nobody seemed to buy the explanation. For months, union workers and activists protested the factory closure and called for boycotts against Playskool, Milton Bradley, and Hasbro toys.

The doors of the Chicago plant were shut for good in 1985, although gallant efforts were made by the Greater North Pulaski Development Corp. to find new uses for the building. Within a couple years, some smaller businesses began occupying parts of the complex, including another wooden toy maker, the Sandberg Manufacturing Company, which was owned for a time in the early ‘90s by another Chicago toy giant, Strombecker.

In 1998, the Freedman Seating Company—a Chicago manufacturer dating back to the 1800s—purchased one of the Augusta Blvd. buildings, and later expandwd into the entire complex in 2010 . . . a rare happy ending! The old plant on Lawndale Avenue lives on as a storage facility along the 606 biking trail, and the Kedzie Avenue facility—while in need of some TLC—remains in use as office spaces in Irving Park.

Since leaving Chicago, of course, Playskool—the brand—has carried on quite well under the Hasbro banner, with other big name products like Glo-Worm, Mr. Potato Head, Tonka, and Play-Doh moving within its division. As tie-ins with TV and film continued to dominate the market, though, Playskool’s original mission—“Learning While Playing”—has gradually taken more of a backseat with the need to compete.

Sources:

“10 High Caliber Men . . .” – Chicago Tribune, Sept 17, 1926

“How Lumber Retailer Developed a Specialty” – American Lumberman, June 15, 1929

“Playskool Institute, Inc.” – corporation, Capital Times (Madison, WI), Oct 11, 1931

“Toy Makers Lease Space in South Clinton Street” – Chicago Tribune, April 17, 1938

“The Playskool Toys (all Jewish basketball team)” – Berwyn Life, Feb 12, 1939

“Playskool Institute of Chicago to Locate on Pad Company Site” – Sheboygan Press, April 6, 1939

“Miss King Dies at St. Joseph’s: Rites Planned Monday” – Sheboygan Press, April 28, 1944

“Santa Goes to Town” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 22, 1946

“Elect Three Men as Directors of Playskool” – Chicago Tribune, Feb 3, 1962

“Playskool Sees Sales Spurt” – Chicago Tribune, March 24, 1962

“Hardly Child’s Play” – Newsweek, October 1, 1962

“Meet Jerry Rockwell, Toymaker to Tiny Tots” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 13, 1964

“Playskool Net Leaps 130 Pct. in Fiscal Year” – Chicago Tribune, March 27, 1968

The Power of Play, by Frank and Theresa Caplan, 1974

“Playskool Leaves Neighbors Feeling Like Broken Toys” – Chicago Tribune, Oct 22, 1984

“Hasbro Sells Closed Plant to Butler Group” – Chicago Tribune, Jan 6, 1987

Lucille King gravesite: FindaGrave.com

Toy Industry Hall of Fame 20222 Inductee Press Release, Aug 31, 2021

i found a vintage revolving blue plastic playskool shape sorter with an orange wooden knob in the center, stacked with green wooden circles, red squares, yellow hexagons and blue triangles. how can I determine if they have lead paint? My 2 year old grandson likes to stick things in his mouth.

When did the wooden jigsaw puzzles start production? In particular, the Peanuts series which shows a 1952, 1958 copyright but that refers to the characters, not the puzzles. Most being sold on sites such as ebay cite the 1958 but I don’t believe that is when they were actually made. Thank you for any help.

I recently found a “home kindergarten” green desk and matching chair, mfg. By J S Playskool division, Milwaukee wi, there are lots of wooden shapes and pieces that were included, not sure which ones originally came with the desk. Just wondering if there would be any interest for this item in a museum?

That’s a great find, Peggy. I’m not sure the Made In Chicago Museum would be the best home for it, since it represents the Milwaukee era of the company. But it definitely could be something of significance perhaps for a toy museum. The original home kindergarten desks could be quite rare these days. –Andrew Clayman, Made In Chicago Museum

I have an old king cole, sing a song of six pense puzzle with 31 3 printed on the back. I can’t find any like it on the internet. I want to know how old it is. It was in my grandma’s playroom and well used when I was young. I am now 63.

The warehouse portion of the facility on Augusta Blvd had issues. (the rest of the facility seemed to be structurally sound). There was netting installed on the ceiling of the loading dock and the associated ceiling in the warehouse adjacent as concrete was falling down from overhead. Used to have to don hard hats to venture into the warehouse area to check on parts you needed for your employees. The “humor” at the time was that the semi’s unloaded in record time as they learned to recognize the sound of concrete falling on the roofs of the semi’s. Story was, the warehouse portion had been built with a suspended/hanging floor design, where the floor hung from the outer walls of the building. The original design called for products to be moved using conveyor “rollers” similar to those used to offload trucks. But over time, heavy forklifts were used, and stopping the forklifts caused the suspended/hanging floor to move, which separated it from the sides of the walls. The rumors at the time (in 1983-84) were some people were not surprised that Playskool had tried to bring the Chicago based hourly workers to Rhode Island when they realized that New England housewives would not be able to perform the largely manual labor tasks associated to manufacturing. My recall was some of the Hispanic folks who did the work were flown to the New England area to “teach” the housewives how to do the tasks. Many toys and similar were made literally by hand. Lincoln Logs, puzzles, and other toys had elements of manual construction involved. It was a hands on facility…The largely Hispanic workers at the Augusta plant did piece work, with bonuses for exceeding production. The rumor was at the time that this was not seen as feasible in the New England environment which was presumed at the time to be largely devoid of a Hispanic working population, plus it took a lot of practice and experience to perform the tasks, none of which was available in the New England area. News articles also imply the wage cost would be less at MB or Hasbro, which is why the operation was moved in 1984, but my recall at the time after being offered a chance to fly out and see the Rhode Island area to make a relocate decision, was that real estate costs were so high, compared to the salary I made, that I would have needed to stay in some sort of company provided housing where your “rent” would be deducted from your paycheck. I opted to find employment in the Chicago area instead and never took them up on the relocation offer. Supervisors such as myself packed out the last boxes of puzzles left behind on the manufacturing floor in the last days before the facility closed.

Industrial designer Wesley Sharer worked at Playschool for most of his career, but his most famous design is the Shure Unidyne I Model 55 “Elvis” microphone. Introduced in 1939, the Unidyne I was designed by Sharer while he worked as an independent consultant for Shure Brothers Company, Chicago. The Unidyne I is in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York City.

Yet another fascinating story, well researched and well told. The Thorne Rooms and Rockwell connections — who knew!! Thank you!

When was the pressed metal Playskool Pullman toy manufactured?

When was the first playskool cobbler’s bench made. The logo is in cursive.

I have an early cobbler bench that is made to sit on but playschool is in green block print. 1932 by what I can gather with hammer and nails.

Playskool was only in cursive from 1950 – 1963