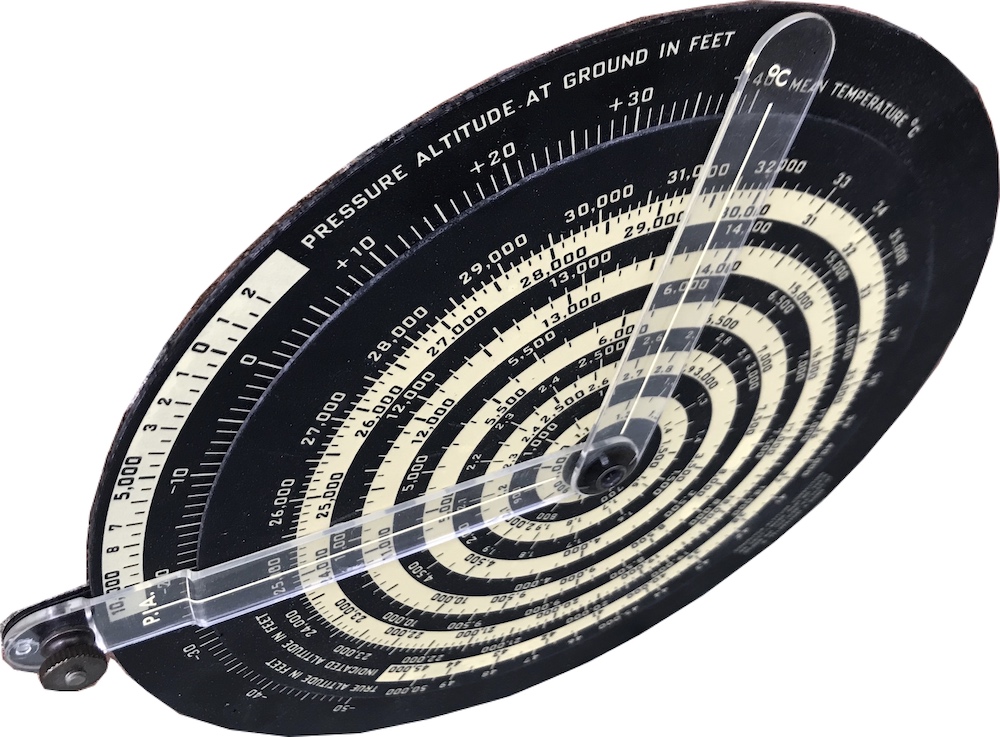

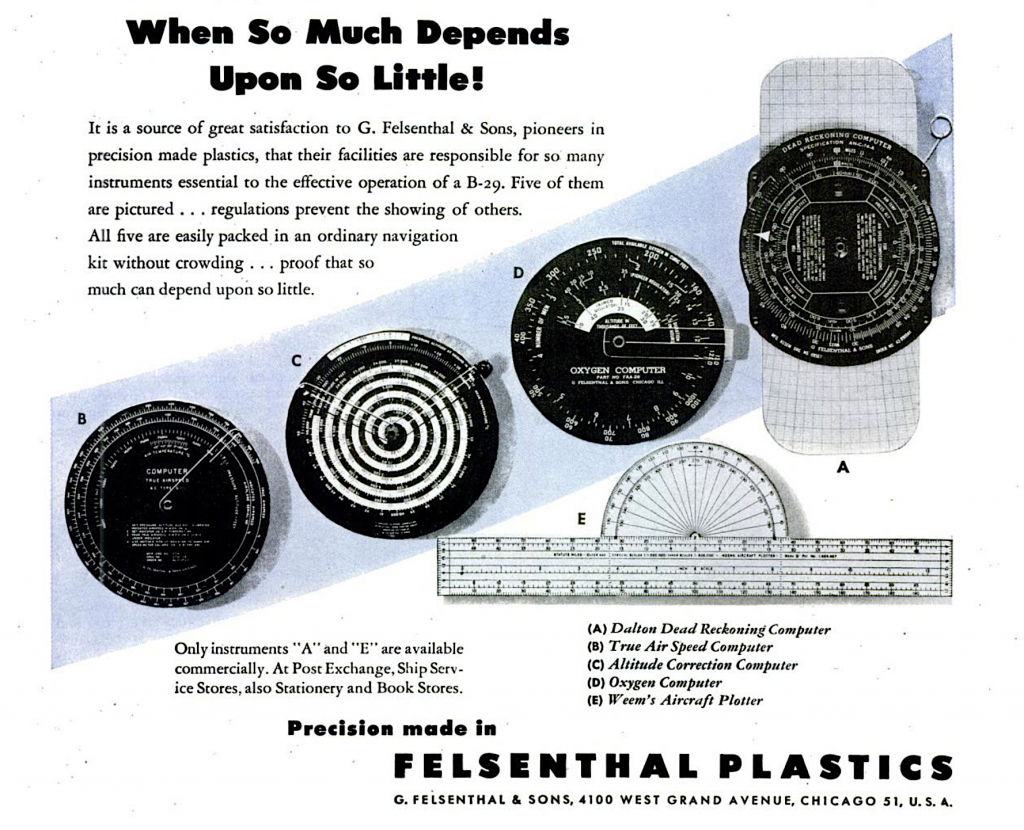

Museum Artifact: Altitude Correction Computer, c. 1945

Made By: G. Felsenthal & Sons, 4100 W. Grand Ave., Chicago, IL [Humboldt Park]

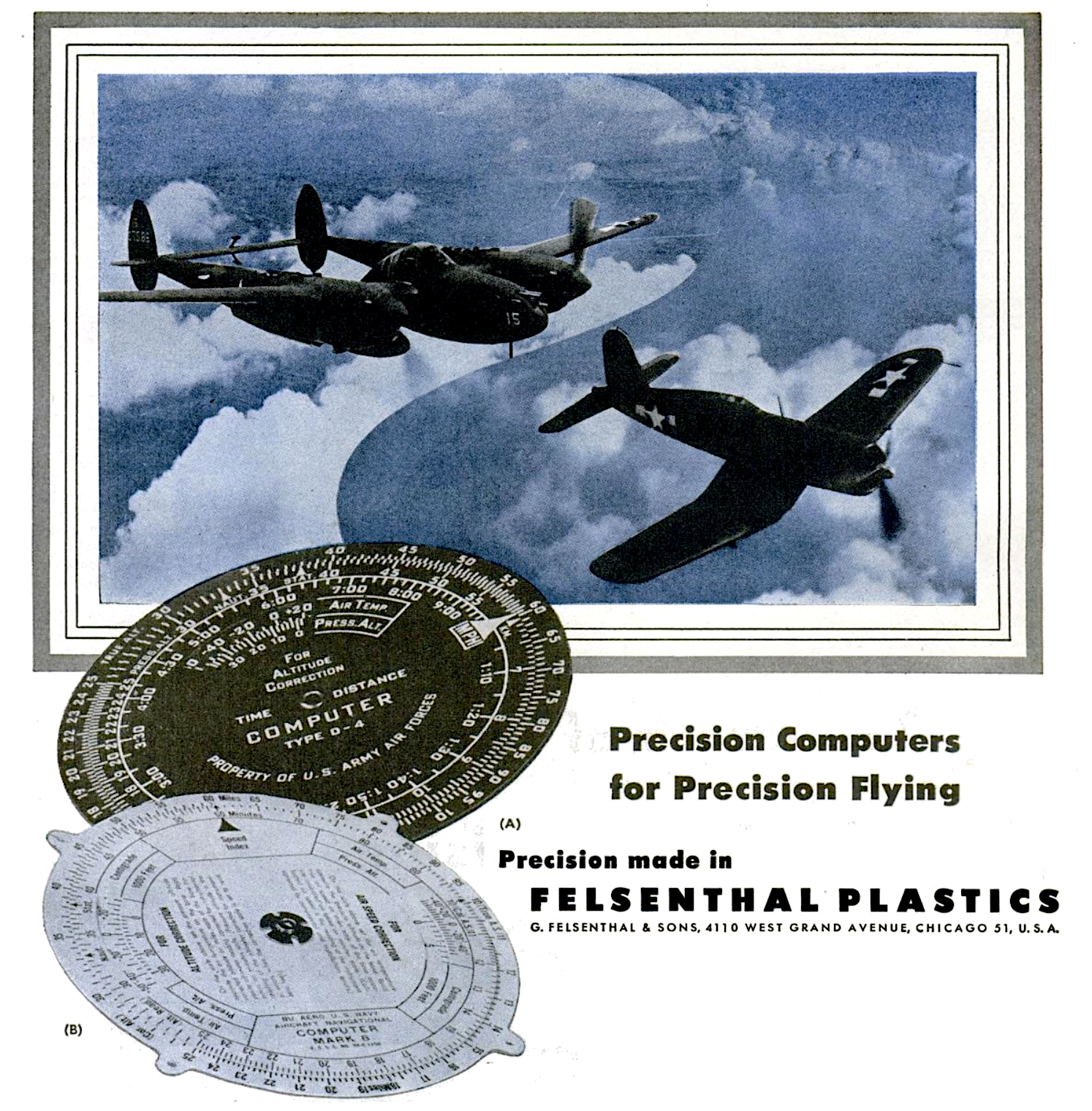

“No sign posts on the mountains . . . no concrete highways in the soup . . . no rocky peak so kind it steps aside to let a plane go by. Yet, with the navigational instruments precision made by Felsenthal, in Felsenthal Plastics, Army Airmen fly the toughest country in the world.” —G. Felsenthal & Sons ad in Flying Magazine, January 1944

In the same way many a rough-and-tumble kid found discipline and a greater purpose during World War II, so too were many businesses transformed as a result of those extraordinary circumstances. For more than 40 years, the Chicago firm of G. Felsenthal & Sons had unapologetically peddled in “advertising novelties”—trinkets and doo-dads that, by their very definition, were among the first types of manufacturing shelved when wartime rationing called only for “necessities.” What might have spelled doom for the Felsenthals, however, wound up plotting the company on a dramatically different course, as the factory that once made cheap pens and piggy banks wound up making 80% of the plastic aviation navigation instruments used by the flyboys overseas.

In the same way many a rough-and-tumble kid found discipline and a greater purpose during World War II, so too were many businesses transformed as a result of those extraordinary circumstances. For more than 40 years, the Chicago firm of G. Felsenthal & Sons had unapologetically peddled in “advertising novelties”—trinkets and doo-dads that, by their very definition, were among the first types of manufacturing shelved when wartime rationing called only for “necessities.” What might have spelled doom for the Felsenthals, however, wound up plotting the company on a dramatically different course, as the factory that once made cheap pens and piggy banks wound up making 80% of the plastic aviation navigation instruments used by the flyboys overseas.

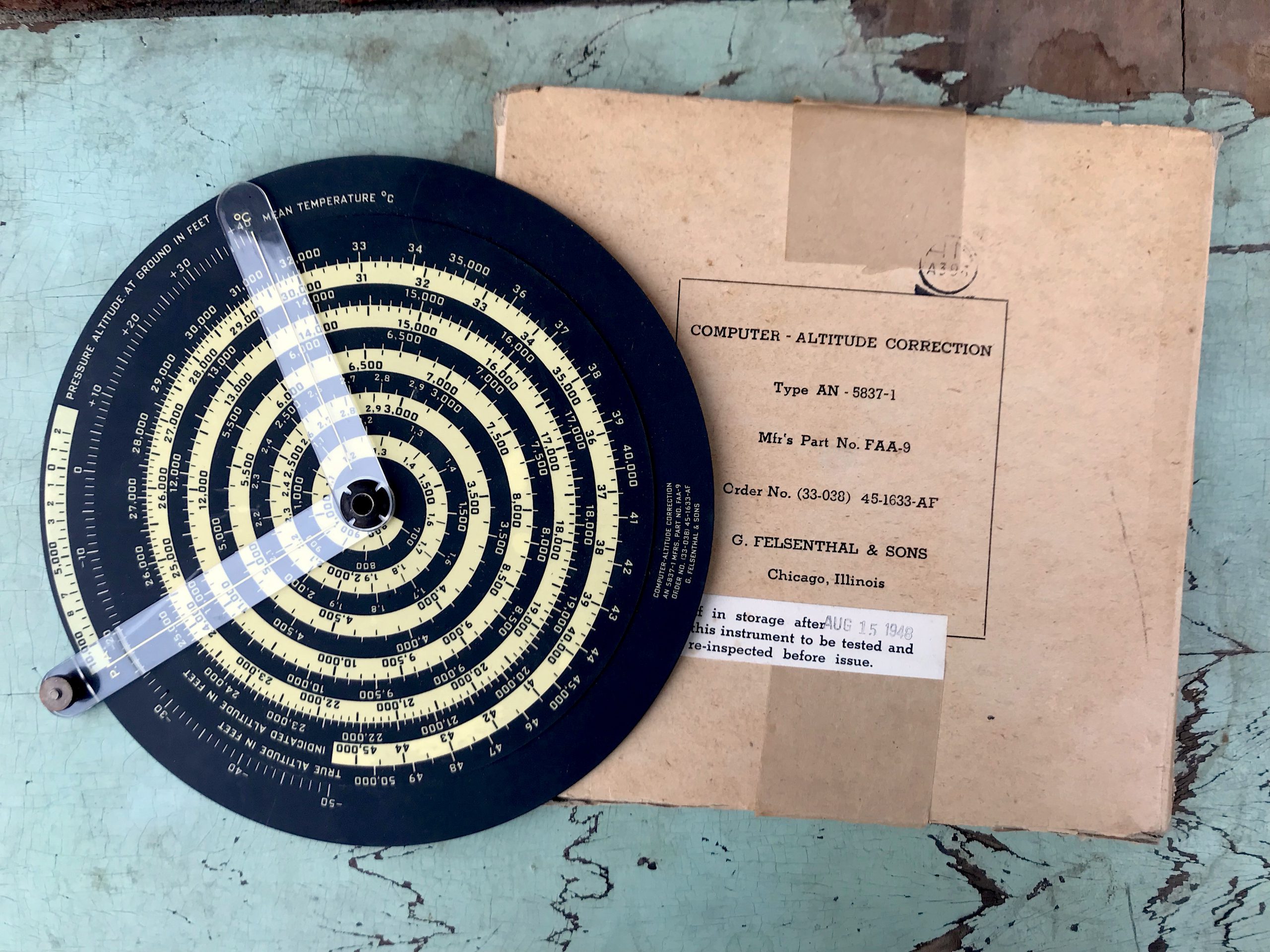

The AN-5837-1 Altitude Correction Computer in our museum collection is one of those said instruments, and while it might look better suited to hypnotizing a pilot than keeping him on course, the general consensus seems to be that these little eight-inch plotters—in their own small way—helped win the day.

Like the Dalton Dead Reckoning Computer and Weems Plotter of the same era, the manufacturing of the AN-5837-1 was contracted out to several different companies during the war. The fact that Felsenthal wound up making the bulk of them speaks to how quickly the business and its operators were able to pivot into their new trade. . . . Although, being in the novelty business for so long, they might have just re-purposed some spinning hypnotist’s discs they already had in stock.

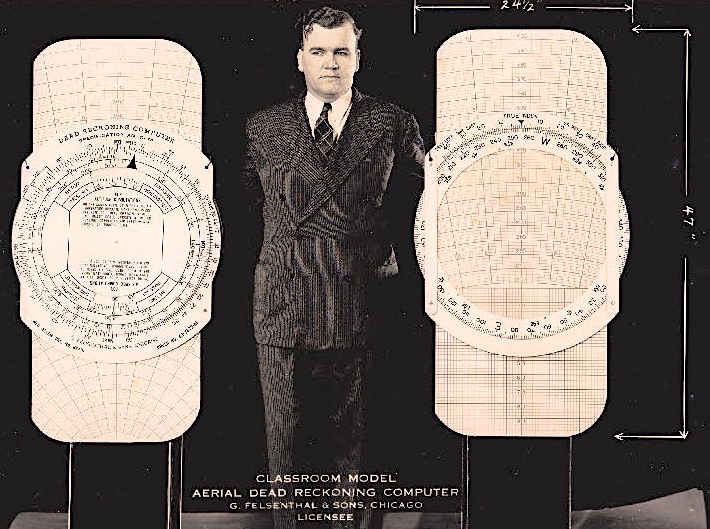

[Promotional image of a giant, classroom model version of the Aerial Dead Reckoning Computer produced by G. Felsenthal & Sons, 1940s]

[Promotional image of a giant, classroom model version of the Aerial Dead Reckoning Computer produced by G. Felsenthal & Sons, 1940s]

Meet All the Felsenthals

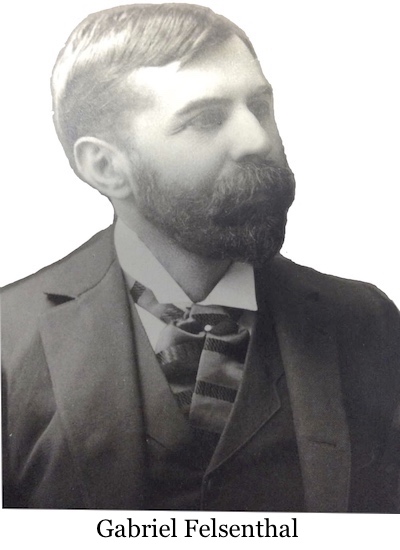

The original “G” in G. Felsenthal & Sons was Gabriel “Gabe” Felsenthal (1856-1925), the Kentucky-born son of Jewish Bavarian immigrants. Gabe’s eventual success as a seller of wares was hardly unique within his family. His father, Marcus, ran a dry goods business in Louisville, and brought up his sons in the trade. Two of those sons, Gabe’s younger brothers Adolph and Lee, were actually the first to move to Chicago, forming their own wholesale jewelry business on State Street in the early 1880s called A. & L. Felsenthal—later to become the Ad-Lee Novelty Co.

Gabe’s path to the Second City would be a longer one. Up through the age of 35, he remained in Louisville, perfecting his skills as a jeweler and watchmaker, and dabbling with new inventions for things like cuff buttons (he nearly nabbed a patent, if not for an unfortunate lawsuit from a button-making firm in New York). Eventually, Gabe partnered up with two of his younger cousins, Henry and Julius Felsenthal, to form “Felsenthal Bros. & Co.,” and in 1892, that entity announced its immediate upheaval to Chicago. Their new office, at 203 Fifth Avenue, was not far from A. & L. Felsenthal’s HQ over at 157 State Street.

Gabe’s path to the Second City would be a longer one. Up through the age of 35, he remained in Louisville, perfecting his skills as a jeweler and watchmaker, and dabbling with new inventions for things like cuff buttons (he nearly nabbed a patent, if not for an unfortunate lawsuit from a button-making firm in New York). Eventually, Gabe partnered up with two of his younger cousins, Henry and Julius Felsenthal, to form “Felsenthal Bros. & Co.,” and in 1892, that entity announced its immediate upheaval to Chicago. Their new office, at 203 Fifth Avenue, was not far from A. & L. Felsenthal’s HQ over at 157 State Street.

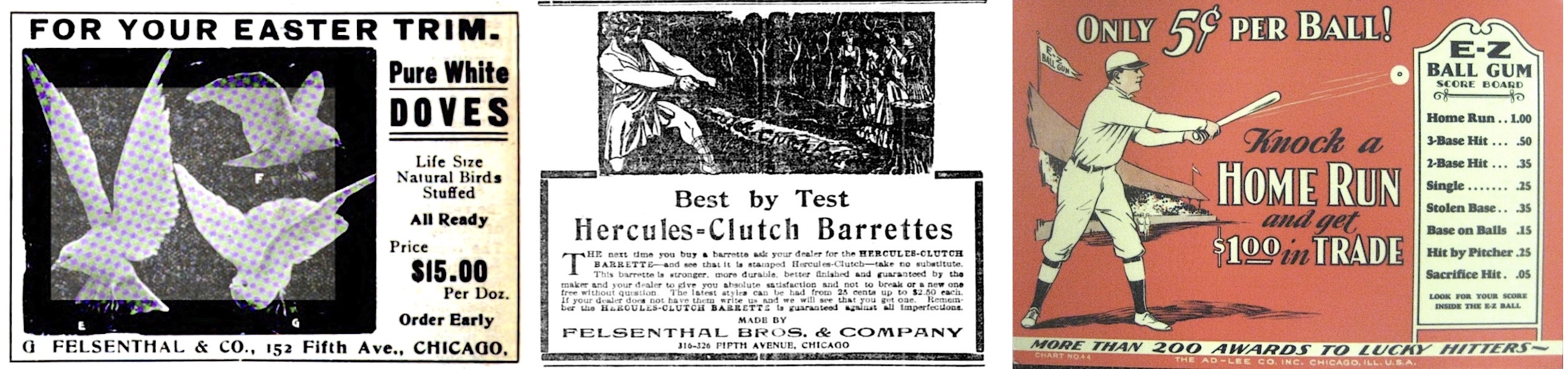

From that point, considering their similar lines of business, the entire Felsenthal clan could have elected to join forces, making this a much simpler story to tell. Instead, it kind of went in the opposite direction.

After just five years, Gabriel Felsenthal retired from Felsenthal Bros. & Co., and struck out on his own, first forming the Crown MFG Co. in 1897, then G. Felsenthal & Co. a year later [it doesn’t seem like the break-up was a harsh one, as Gabe’s new office at 154 Fifth Avenue was right next door to his cousins]. And so, as the 20th century dawned, Chicago was now home to not one, not two, but THREE separate wholesale novelty companies run by different members of the very same Felsenthal family. Who did you trust to make your custom-engraved trinkets? A. & L. Felsenthal? Felsenthal Bros? Or G. Felsenthal & Co? Passover dinners must have been a minefield.

[The Felsenthal family had the novelty business covered in Chicago. From left: a G. Felsenthal & Co. ad for “life size natural birds stuffed” (1901), a Felsenthal Bros. & Co. ad for “Hercules-Clutch Barrettes” (1910), and an Ad-Lee Novelty Co. (formerly A. & L. Felsenthal) ad for “E-Z Ball Gum” coin-op machines (1921)]

[The Felsenthal family had the novelty business covered in Chicago. From left: a G. Felsenthal & Co. ad for “life size natural birds stuffed” (1901), a Felsenthal Bros. & Co. ad for “Hercules-Clutch Barrettes” (1910), and an Ad-Lee Novelty Co. (formerly A. & L. Felsenthal) ad for “E-Z Ball Gum” coin-op machines (1921)]

From Stuffed Birds to Movie Magic

Anyway, part of the impetus for Gabriel Felsenthal’s new venture in 1898 might have been his desire to evolve beyond the typical jeweler’s junk trade into more unconventional sorts of advertising novelties.

In the early years, this could mean just about anything—up to and including . . . decorative dove taxidermy, “spangle belts,” wall-mounted match scratchers, telephone name plates, and papier-mache Santa Clauses (all actual things Felsenthal advertised). But Gabe’s real passion seemed to be the new and exciting world of photography and “moving pictures.”

In the early years, this could mean just about anything—up to and including . . . decorative dove taxidermy, “spangle belts,” wall-mounted match scratchers, telephone name plates, and papier-mache Santa Clauses (all actual things Felsenthal advertised). But Gabe’s real passion seemed to be the new and exciting world of photography and “moving pictures.”

G. Felsenthal & Co. got into camera production as early as 1899, but they didn’t gain much traction until one particular item caught the public’s attention about a decade later.

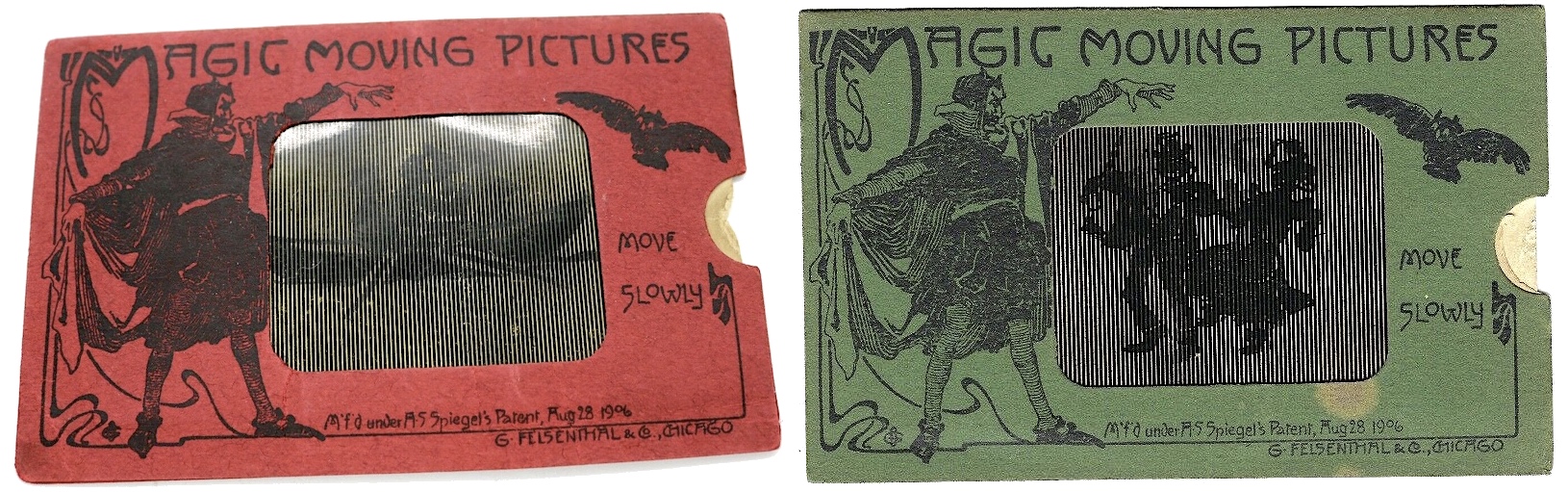

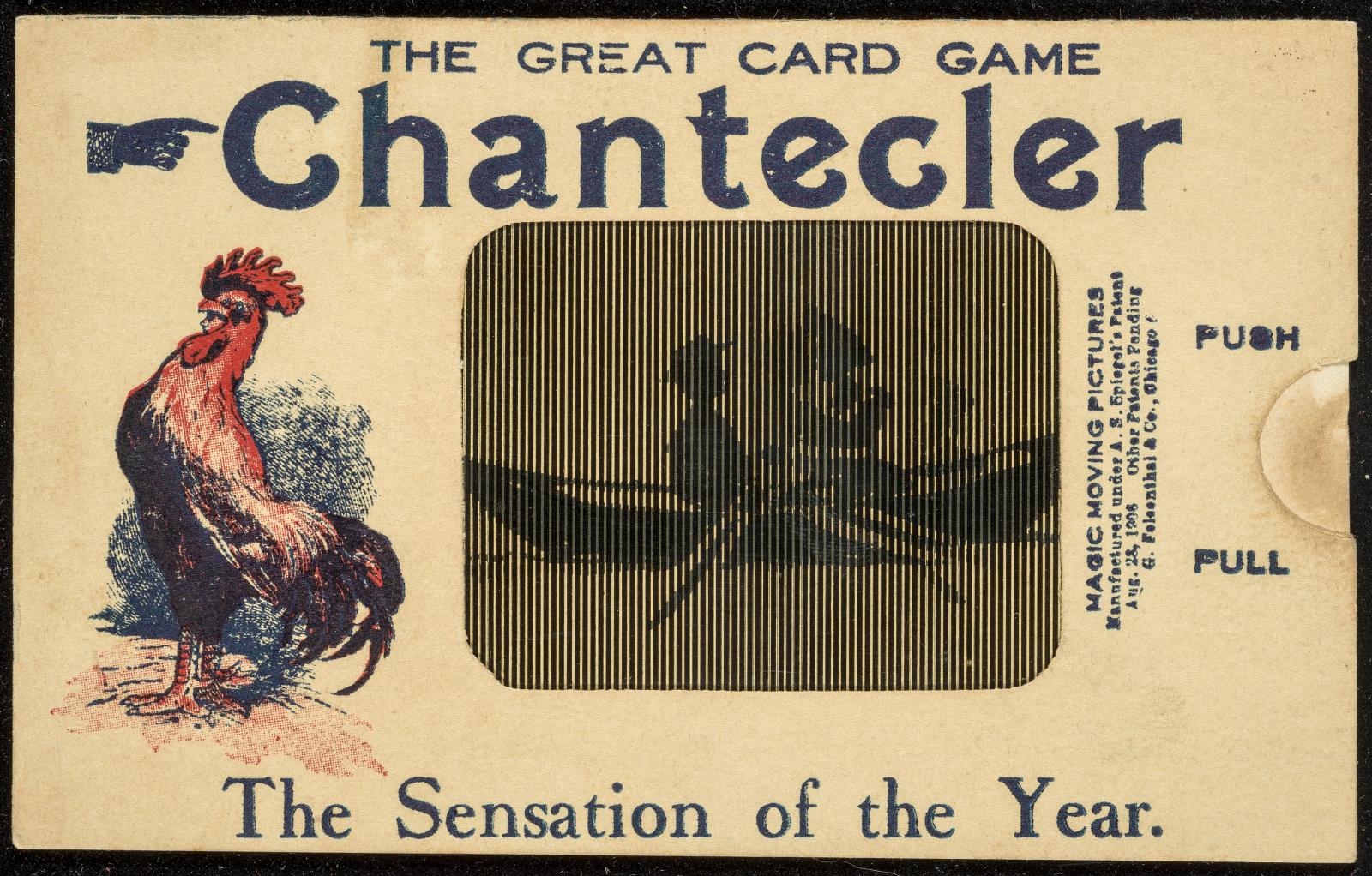

“A movie picture show in your home!” a Felsenthal ad boasted in 1909, describing its new “Magic Moving Pictures” postcards [by this point the company had moved to 217 E. Van Buren]. “A new and attractive invention. Amusing and interesting to old and young.”

[These “magic” sliding postcards utilized gelatin silver on paper and line-screen on film inside a cardboard mount]

[These “magic” sliding postcards utilized gelatin silver on paper and line-screen on film inside a cardboard mount]

In the age of the Nickelodeons, it’s hard to overstate just how fresh and mesmerizing any moving image really was, and Felsenthal’s colorful pull cards—which utilized a 1906 line-screen animation patent by Alexander S. Spiegel—still hold up as a fascinating sort of first-wave hologram, bringing three separate images together on one miniature handheld “screen.”

“See the Horses Run, Lovers in a Boat, Chicken Fight, Grandpa Rocking the Baby, Baseball Players, and other lifelike objects.”

Yup, even 100 years ago, people could still find virtual reality—no matter how mundane—far more interesting than real life.

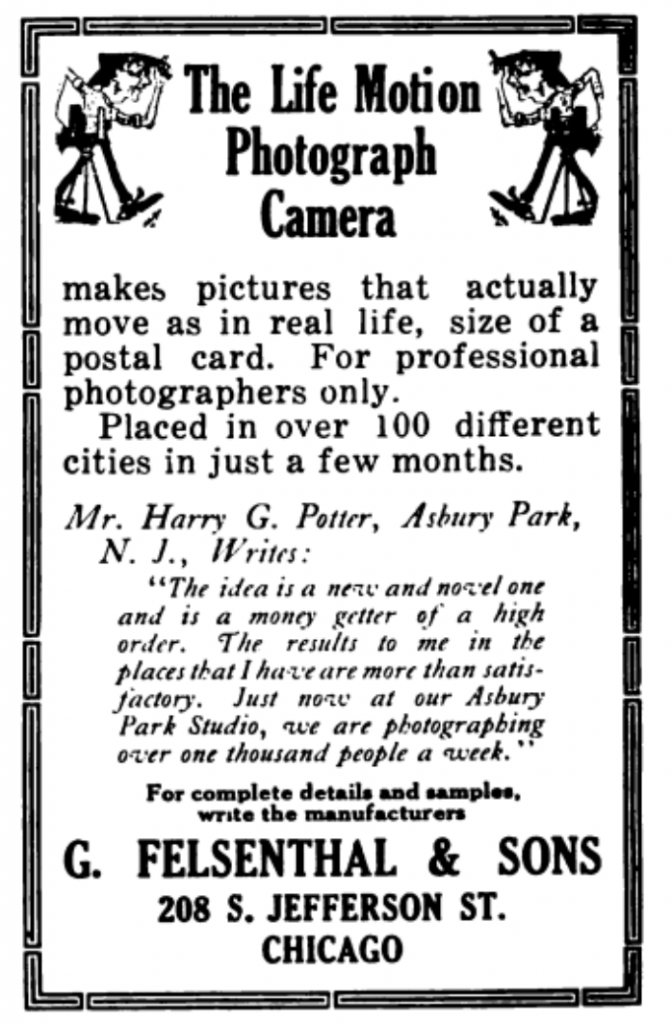

By 1915, Gabriel Felsenthal had gone a considerable step further with the same concept, patenting designs for a new camera apparatus that could “take a series of photographs on one plate,” thus creating the “illusion of motion” when properly displayed. It was the first true indication that his company might have a future in more sophisticated sorts of instruments.

“One of the most pleasing photographic novelties that has come to our notice for many years,” according to a 1914 issue of the American Journal of Photography, “is the magic moving photograph produced with the camera sold by G. Felsenthal & Co., 206 South Jefferson St., Chicago.

“One of the most pleasing photographic novelties that has come to our notice for many years,” according to a 1914 issue of the American Journal of Photography, “is the magic moving photograph produced with the camera sold by G. Felsenthal & Co., 206 South Jefferson St., Chicago.

“Three different poses with varying facial expression are made of a person on one plate, a device (lever) at the back of the camera being manipulated after the first and second exposures. This gives unlimited opportunities to produce pictures that are both serious and humorous.

“This pleasing and surprising novelty bids fair to become the one great summer-amusement everywhere, for it appeals not only to amateurs, but to professionals who will recognize in it a ready and popular source of pecuniary profit. The manufacturers assure us that ample protection will be given to commercial users of their Life-Motion Photograph Camera. Every one interested should send at once for a sample of these amusing motion-photographs.”

Sadly, I’ve yet to find any evidence of what the Life-Motion Photograph Camera actually looked like, and I’m not even sure if any still exist in the world—they were only marketed for a short time, and with the onset of World War I, production abruptly halted, probably for good.

Here Come the Sons

It was during this same period, just before the the Great War, that G. Felsenthal & Co. was officially re-incorporated as “G. Felsenthal & Sons,” with Gabe’s eldest kids Lester (1886-1948) and Irving (1888-1956) becoming the latest members of their mercantile family tree.

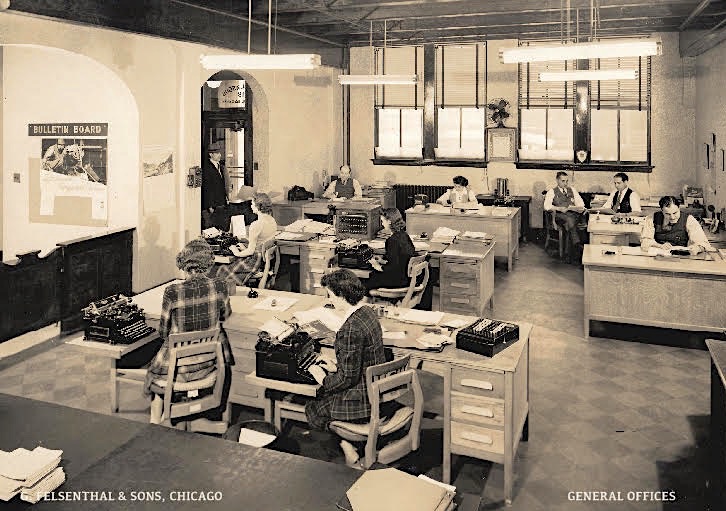

The hand-off appeared to be well timed heading into the novelty-obsessed 1920s, and in 1921, a new three-story factory was established at 1407 Hudson Avenue, former home of the Peerless Confection Co. Here, the production of pens, candy bar holders, tape measures, vanity cases, paper weights and other “celluloid specialties” could expand. All was not rosy for long, however.

The hand-off appeared to be well timed heading into the novelty-obsessed 1920s, and in 1921, a new three-story factory was established at 1407 Hudson Avenue, former home of the Peerless Confection Co. Here, the production of pens, candy bar holders, tape measures, vanity cases, paper weights and other “celluloid specialties” could expand. All was not rosy for long, however.

Gabriel Felsenthal died in 1925 just shy of his 70th birthday, and in 1928, his sons were forced to relocate the business when the city announced it would be taking over the land on Hudson Avenue for the “Field garden apartment project.” On the bright side, the company was able to commission a new two-story structure on Grand Avenue, designed by one of the legends of industrial architecture, Alfred S. Alschuler. It opened a year later (just in time for the stock market crash) with all the bells and whistles of a fully modern facility.

Lester and Irving were determined to keep their dad’s vision alive.

[Second generation: Irving G. Felsenthal, left, and his brother Lester J. Felsenthal, c. 1940s]

[Former G. Felsenthal factory at 4100 W. Grand Ave., 1940s and today]

[Former G. Felsenthal factory at 4100 W. Grand Ave., 1940s and today]

A New Purpose

Logically, the Great Depression should have spelled the end for Felsenthal, as it did for many of its rivals in the advertising novelty racket. In the midst of an economic meltdown, there wasn’t exactly a booming interest in customized paperweights.

Rather than letting their brand new factory and machines go to waste, however, Lester and Irving found ways to stay productive. This likely meant a greater focus on injection molded auto parts, industrial name plates, and other stuff less likely to be promoted to the general public. As a result, advertisements for G. Felsenthal & Sons virtually vanished from commercial newspapers and magazines in the 1930s, creating a bit of a hazy cloud over this era of the business. In fuller context, though, it’s pretty clear that the survival strategies implemented during these years also set the table for the financial windfall that wartime demands would bring.

[Workers at the Felsenthal plant on Grand Avenue, circa 1940s. Clockwise from top left: kick press machines, conveyer belt assembly line, punch presses, and the laminating department.]

[Workers at the Felsenthal plant on Grand Avenue, circa 1940s. Clockwise from top left: kick press machines, conveyer belt assembly line, punch presses, and the laminating department.]

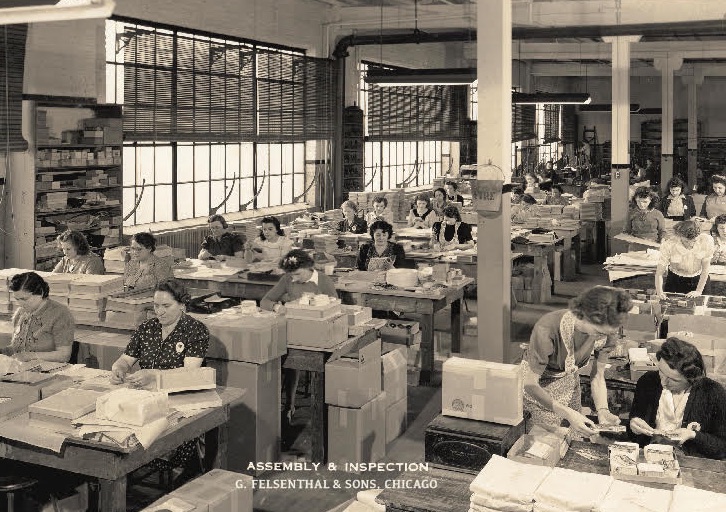

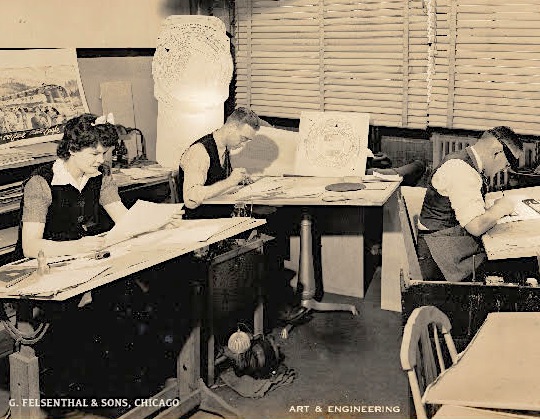

By the early ’40s, the Grand Avenue plant was abuzz with rattling machines and percolating minds. Felsenthal’s wartime workforce, equal parts women and men, included its own arts and engineering department and conveyer-belt style assembly lines, churning out new “computers” of the flat plastic sort.

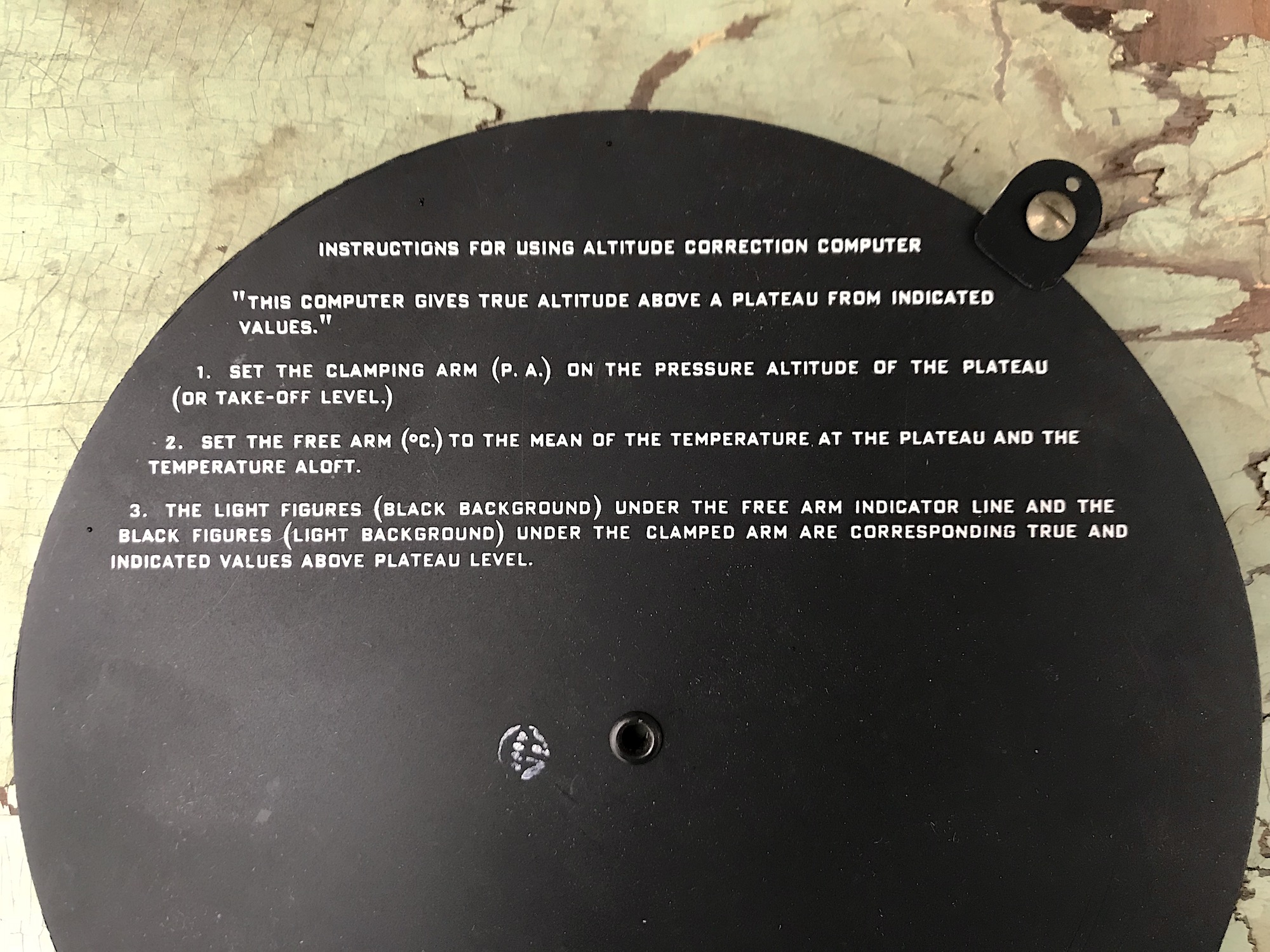

The company eventually made more than 75% of the plastic calculating instruments used by the Army Air Forces, and over 90% of those used by the Navy Bureau of Aeronautics. This included our museum artifact, which operated, as explained on the back of the disc, by giving the “true altitude above a plateau from indicated values.”

How to Use the Felsenthal Altitude Correction Computer (according to the computer itself):

How to Use the Felsenthal Altitude Correction Computer (according to the computer itself):

1. Set the clamping arm (P.A.) on the pressure altitude of the plateau (or take-off level).

2. Set the free arm (degree C.) to the mean of the temperature at the plateau and the temperature aloft.

3. The light figures (black background) under the free arm indicator line and the black figures (light background) under the clamped arm are corresponding true and indicated values above plateau level.

Hmmm, okay then. Easy peasy, lemon squeezy. . .

Anyway, the U.S. government was ultimately so pleased with Felsenthal’s efforts that they awarded the firm the Army-Navy “E” Award for excellence. Sounds fairly vanilla, but only 5% of the roughly 85,000 companies involved in wartime manufacturing contracts got that recognition. Apparently, key factors in achieving this status included:

–Quality and Quantity of Production

–Overcoming of Production Obstacles

–Avoidance of Work Stoppages

–Maintaining of Fair Labor Standards

–Training of Additional Labor Forces

–Good Record Keeping in Relation to Health and Safety

[Advertisement from Flying magazine, 1944]

[Advertisement from Flying magazine, 1944]

Post-War Plastics

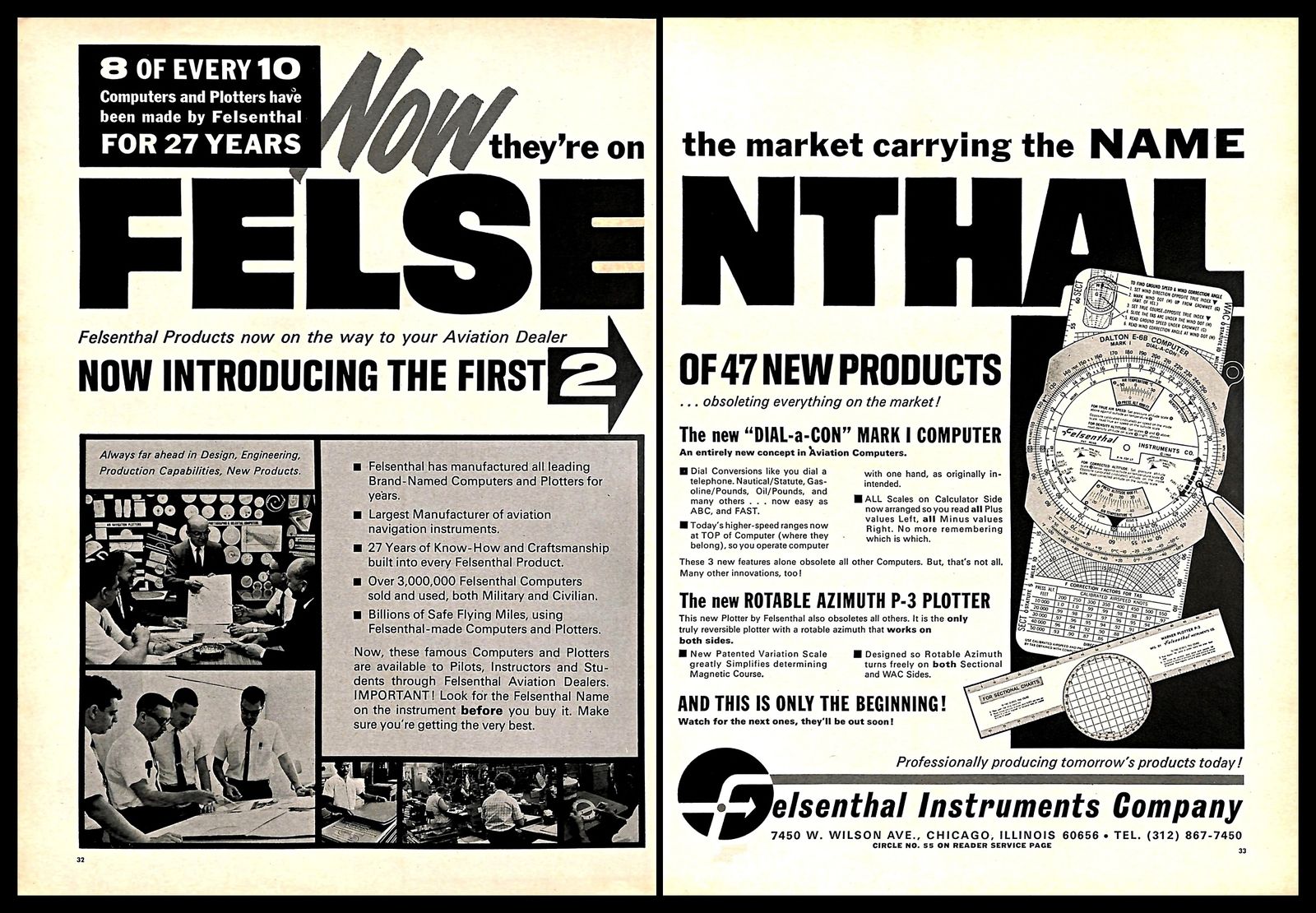

After the war, there was no going back to the days of papier mache Santas. G. Felsenthal & Sons not only remained a leading manufacturer of aeronautics instruments, but also a formidable producer of injection molded plastic parts for the auto industry, office equipment, food containers, home appliances, and televisions.

In 1953, the company moved into a new, single-story factory, in the modern style, at 3500 N. Kedzie Avenue. Six years later, though, with both of the Felsenthal sons deceased, the family business was effectively concluded, as the J. L. Clark Manufacturing Company of Rockford purchased the company and turned it into their new plastics division.

[Former Felsenthal Plastics plant at 3500 N. Kedzie, utilized from 1953 to the mid ’70s]

[Former Felsenthal Plastics plant at 3500 N. Kedzie, utilized from 1953 to the mid ’70s]

The Kedzie Avenue factory continued to operate under the Felsenthal Plastics name even after Clark subsequently sold it in 1971 to Milwaukee’s Grede Foundries, Inc. (a rough name for any business trying to claim its acquisitions are ethical). By 1977, however, times had clearly taken a negative turn, and a final sale to the Northern Engraving Corporation in 1977 appears to have brought Felsenthal’s Chicago tale to a close.

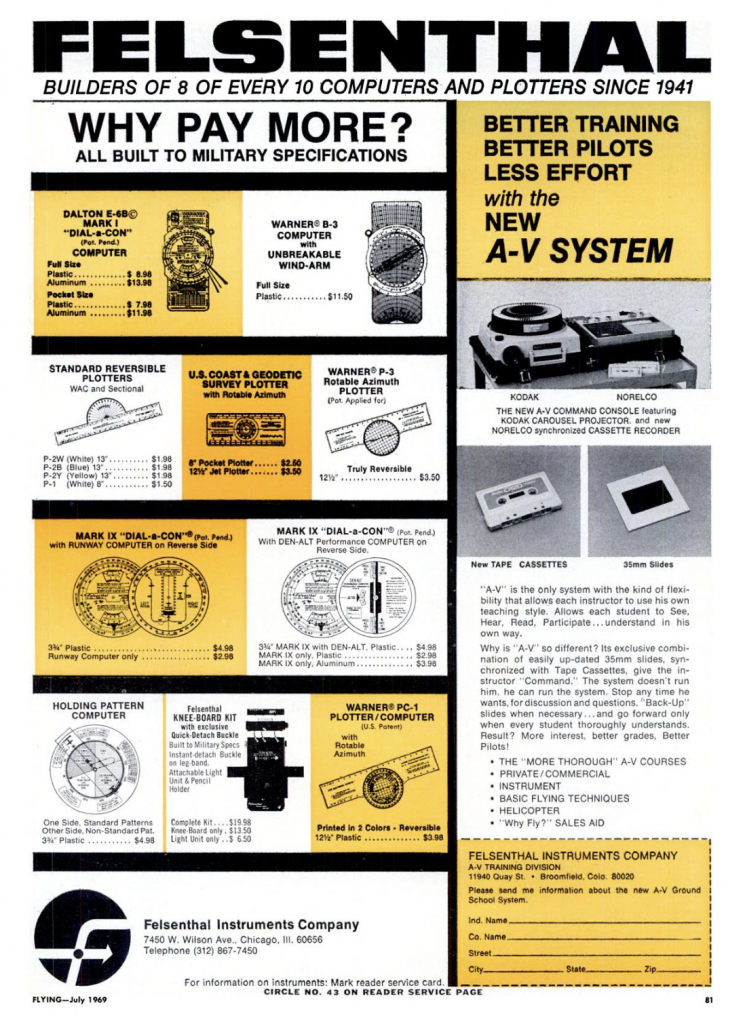

There is a little bit of a loose thread, though. In the mid 1960s, Felsenthal split off its computer/instrument production into a separate business, the Felsenthal Instruments Company, which had its own dedicated plant at 7450 W. Wilson Avenue. This split was probably overseen by the J. L. Clark MFG Co., which presumably still operated both halves of the Felsenthal brand. But it’s also possible that the instrument wing went independent for a brief time. Either way, it all eventually dissolved in the ‘70s, as so many nice things did.

There is a little bit of a loose thread, though. In the mid 1960s, Felsenthal split off its computer/instrument production into a separate business, the Felsenthal Instruments Company, which had its own dedicated plant at 7450 W. Wilson Avenue. This split was probably overseen by the J. L. Clark MFG Co., which presumably still operated both halves of the Felsenthal brand. But it’s also possible that the instrument wing went independent for a brief time. Either way, it all eventually dissolved in the ‘70s, as so many nice things did.

Flying high on their wartime merits for years, G. Felsenthal & Sons eventually could no longer navigate their way through rapid changes in the plastics industry. But many of the instruments they helped develop established a standard that’s still apparent in some of today’s far more advanced cockpit computers.

[Ad for the Felsenthal Instruments Company, a separate division from Felsenthal Plastics. 1968.]

[Ad for the Felsenthal Instruments Company, a separate division from Felsenthal Plastics. 1968.]

***

Special thanks to David Goldman of Mercury Plastics, Inc. for providing assistance with this research. David’s great-grandmother was Regina Felsenthal (sister of Lester and Irving), and his grandpa was John Goldman, who started Mercury Plastics in Chicago in 1955, clearly inspired by the existing family business. Mercury is still in operation, based out of a former Stewart Warner plant at 4535 W. Fullerton Ave.

[G. Felsenthal & Sons sign can still be seen today above the doorway of the old factory at 4100 W. Grand Ave.]

[G. Felsenthal & Sons sign can still be seen today above the doorway of the old factory at 4100 W. Grand Ave.]

[An early Felsenthal & Co. ad from 1899, promoting their papier mache services, also suggests Gabe Felsenthal might have made a name for himself in Chicago by building a “big Santa Claus” for the World’s Fair in 1893]

[An early Felsenthal & Co. ad from 1899, promoting their papier mache services, also suggests Gabe Felsenthal might have made a name for himself in Chicago by building a “big Santa Claus” for the World’s Fair in 1893]

Sources:

“G. Felsenthal & Sons” – History Display, provided by David Goldman

“Celluloid Compacts Made by G. Felsenthal & Sons” – CollectingVintageCompacts.blogspot.com

“The Magic Moving Photograph” – Photo Era, May 1914

“Felsenthal to Build a Factory in Grand Avenue” – Chicago Tribune, Jan 8, 1928

“Plastics Division Purchased” – Waukesha Daily Freeman, June 9, 1971

Jeweler’s Circular and Horological Review, Vol. 24, 1892

Jeweler’s Circular and Horological Review, Vol. 34, 1897

Ancestry.com

Archived Reader Comments:

“I have a really cool wood framed mirror that my grandfather bought my grandmother a long time ago that I inherited when they passed. It has wording on it that reads, ELK COLLAR BUTTONS are guaranteed, Felsenthal Bros. & Co., Makers. ———— Chicago. I’m assuming it’s from 1892 if it reads Felsenthal Bro. & Co. It’s still in perfect condition and this is such a great article to read about the Family. I hold the mirror very close to my heart and the history is very cool.” —Julie, 2020

“Hi, My name is John Cascio. My father, Vincent J. Cascio, worked as an artist for 27 years for this company and created finished art still in use today. The last location was on Wilson Avenue with a Chicago address located in Harwood Heights. I worked there for a short period for Felsenthal Instruments while going to College, (1962-1966) Great people. I still remember most of the people that worked there including Ben Rau. My cousin Jack Cascio worked there in art and production control also for many years.” —John Cascio, 2020

“I have one of Felsenthal’s NAVIG-AIDERs. When my husband used it to pilot us from Seattle up to Vancouver and the San Juan Islands in the late 80’s, I thought to myself, “You’ve got to be kidding me.” But we made it (He was a very experienced skipper out of California.) This story is amazing, especially since I am from Chicago, know this area very well and recognize some of the factories. Thank you for sharing this incredible history.” —DB, 2020

“A beautiful rendering. My grandfather was Lester Felsenthal, my mother’s Dad… and Gabriel my great grandfather. I am so grateful for the account of Felsenthal and Sons and the integrity and tenacity of a flexible Chicago company that adapted and thrived. Fun to see how they were creative businessmen not to mention surviving the rigors of a family business. Thanks David Goldman!! Your Cousin, Beth! Lester and Reggie’s granddaughter. Joannn’s daughter! Excellent research and you captured our heritage!” —Beth, 2019

Hello,

Did the instrument company make “equal space divider” under private label for the T Alteneder Co of Philadelphia. They sold one that is the spitting image of the one sold under the Felsenthal name..??

THanks

I have a Felsenthal “Computer, Local Hour Angle Type X-1”. It’s fascinating. Can you tell me what year it was created, and help me figure out how to use it?

I live in the Netherlands and bought a photograph on which “Life Motion Photograph” is inscribed (it seems to be handwritten). I looked the term “Life Motion” up in a few Dutch sites and found a few Dutch companies that seem to have used this technology and some photography journals that describe it, all ca. 1915-8. The photograph itself looks rather ordinary to me! A middle-aged woman with her hair in a bun and a slight smile on her face.

Unfortunately, someone has trimmed the border of the photograph so part of the inscription has been cut off.

I am a Felsenthal descendant (and the family historian on the Birkenstein line, which Mariana Felsenthal married into, likely performed by Rabbi Bernhard Felsenthal). Thank you for this!

What a great, well written and engaging article. Great work!!

I had an old “FAB” celluloid tap measure with the name Felsenthal & sons in micro print on it.

googled it and got this article. Love stories of business history in US. What a country!

Can you tell me what year this is from. My dad was in the Korean War & Vietnam War.

U.S. PROPERTY

CHART PLOTTING BOARD MARK-7

SPEC. MIL-B-5046 A

STOCK NO. R 88 B 0650-005-000

MFG’S PART NO. N. FNA 306

CONTRACT NO. N 383s – 75488

G. FELSENTHAL & SONS,INC

CHICAGO 51, ILL.

I just purchased one of these at Thunder Over Michigan, Willow Run. It is unopened with date stamp for “reinspection” after Mar 26, 1948. Is it worth more unopened?? I’ll probably buy another one just for display purposes

Do you know of anyone who is buying Felsenthal magic motion picture advertisement cards? I found one in my Grandma’s drawer after she passed…very neat!

Thank you,

Amy

Are there better instructions on how to use the Computer-altitude correction device? We have one and the instructions on the back, but how and why to use this device isn’t totally clear. Perhaps a training document showing pilots how to use this?

I need the instruction manual for the CPU-26A computer air navigation dead reckoning computer. Can you help me out?