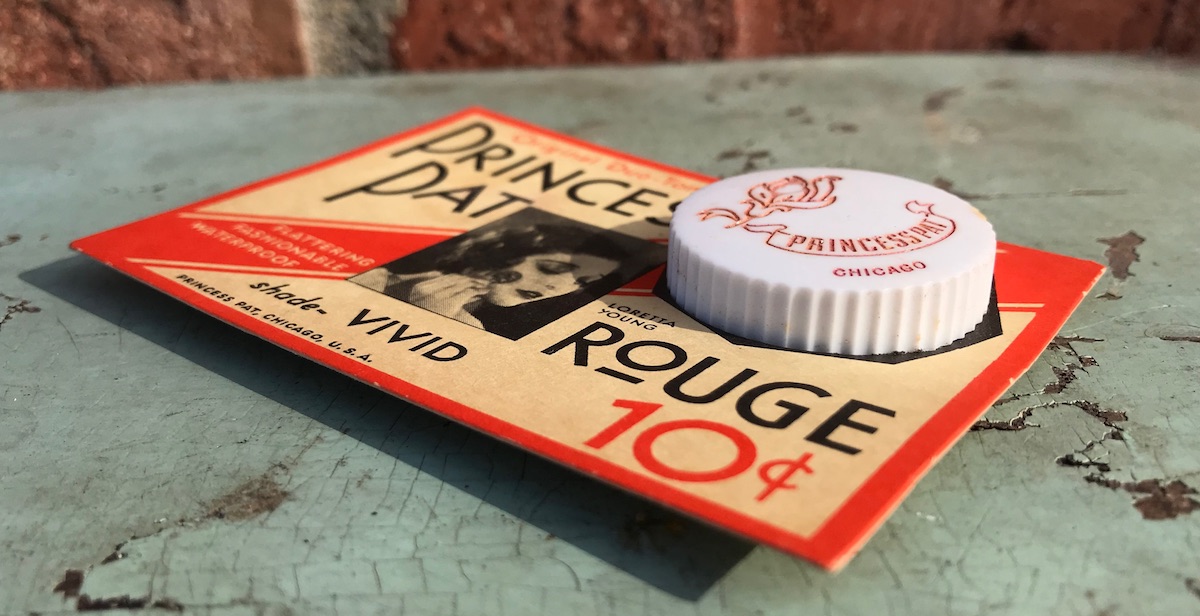

Museum Artifact: Princess Pat Duo-Tone Rouge, c. 1931

Made By: Princess Pat, Ltd., 2709 South Wells Street, Chicago, IL [Armour Square]

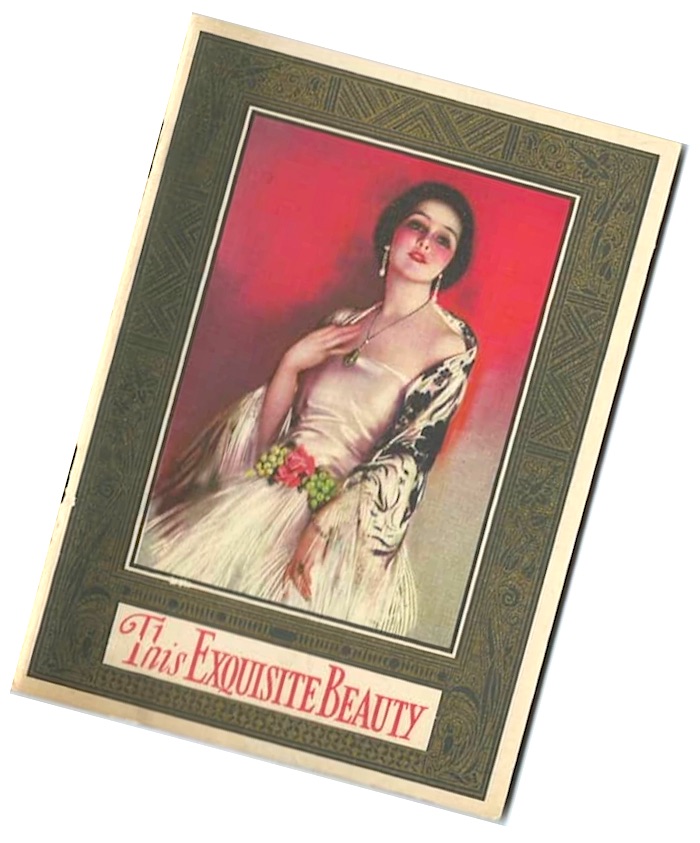

“She is exquisite, this woman of today. She is frank—too vivid and intense for pretense. She revels in luxury . . . Color, line, softness, she perceives and strives for. She does not fear her mirror.” —excerpt from Princess Pat sales booklet, “This Exquisite Beauty,” c. 1930

Patricia Gordon was not a princess. In fact, the co-founder and president of Chicago’s Princess Pat, Ltd. wasn’t even technically a “Pat.” A first-generation Jewish immigrant, she was born in Russia as Frances Berezniak in 1888, and was still known to her friends and husband / company co-founder Max Martin Gordon as “Fannie” well into her later years.

Patricia Gordon was not a princess. In fact, the co-founder and president of Chicago’s Princess Pat, Ltd. wasn’t even technically a “Pat.” A first-generation Jewish immigrant, she was born in Russia as Frances Berezniak in 1888, and was still known to her friends and husband / company co-founder Max Martin Gordon as “Fannie” well into her later years.

The naming of the Gordons’ cosmetics line was initially intended as a trendy homage to Queen Victoria’s popular granddaughter, Princess Patricia of Connaught. But as the true public face and voice of the brand, Fannie Gordon eventually adapted her own identity to better serve the business. She became the titular Patricia, and—in combination with a 50-year career as a chemist, business executive, writer, lecturer, radio host, and advertising guru—arguably achieved her own version of royalty within the beauty industry.

History of Princess Pat, Part I. “A Mystical Underglow”

Princess Pat, Ltd. and its sister company Gordon-Gordon, Ltd. were South Side institutions (mostly in the Armour Square neighborhood) from the 1910s to the 1950s, developing along a very similar early trajectory to their North Side rivals at Maybelline. Obviously, those paths would eventually diverge, as international immortality wasn’t in the cards for our rouge-making friends. Still, for a relatively small, family owned business, Princess Pat generated a fierce and loyal following—adeptly riding the delicate line between serious skin care science and old-fashioned hyperbolic quackery (the Federal Trade Commission would eventually target them for the latter).

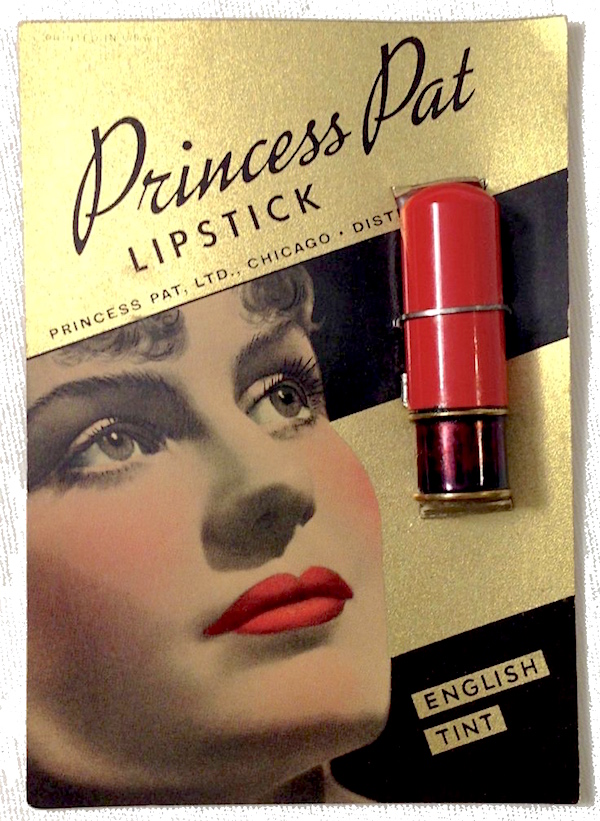

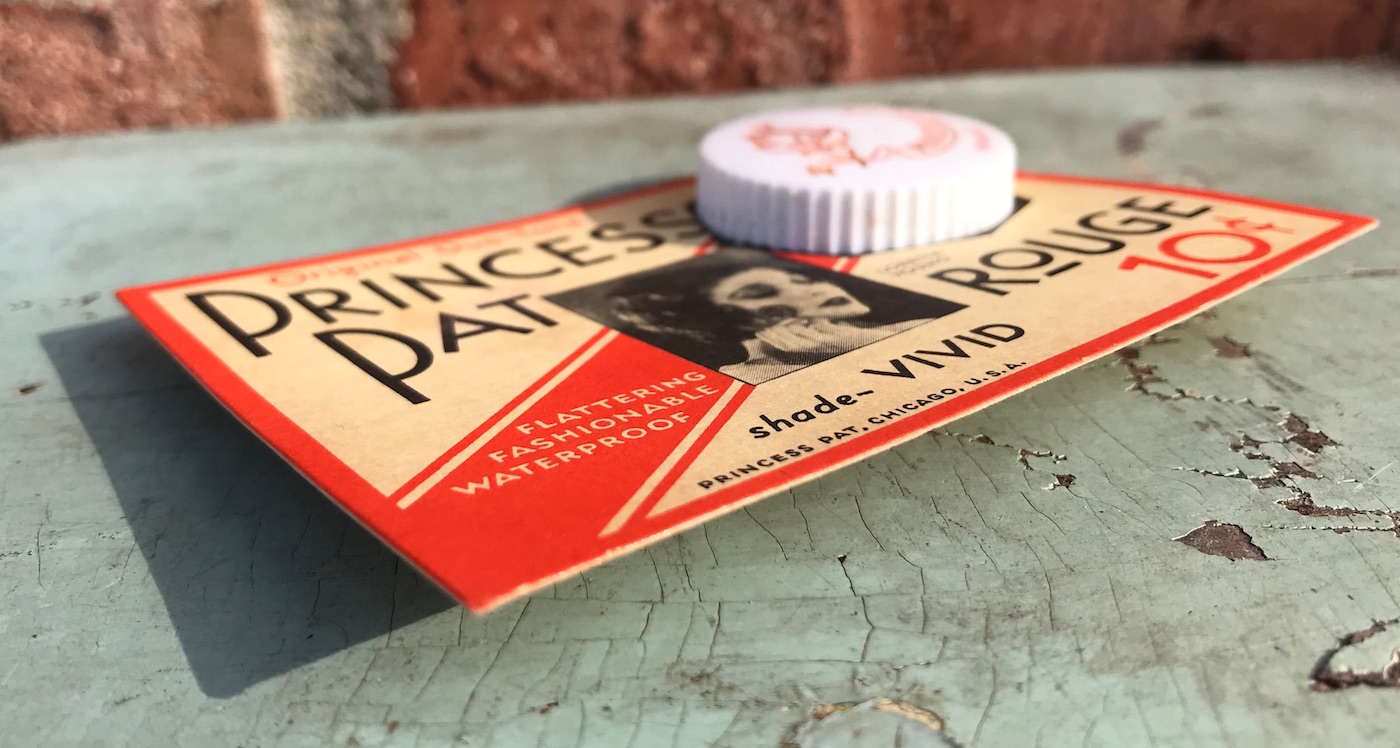

Even when their financial standing got a wee bit wobblier during the 1930s, the Gordons survived by offering the women of the Depression an affordable path to a glamorous new image, often represented by young Hollywood starlets like Loretta Young, who was just 18 when she licensed her visage over to the company’s Duo-Tone “Vivid” Rouge 10-cent sampler pack in 1931 (as seen in our museum artifact).

[Loretta Young, a Warner Bros actress in the early ’30s, was one of many young film stars that Princess Pat turned to as model endorsers of its beauty products]

[Loretta Young, a Warner Bros actress in the early ’30s, was one of many young film stars that Princess Pat turned to as model endorsers of its beauty products]

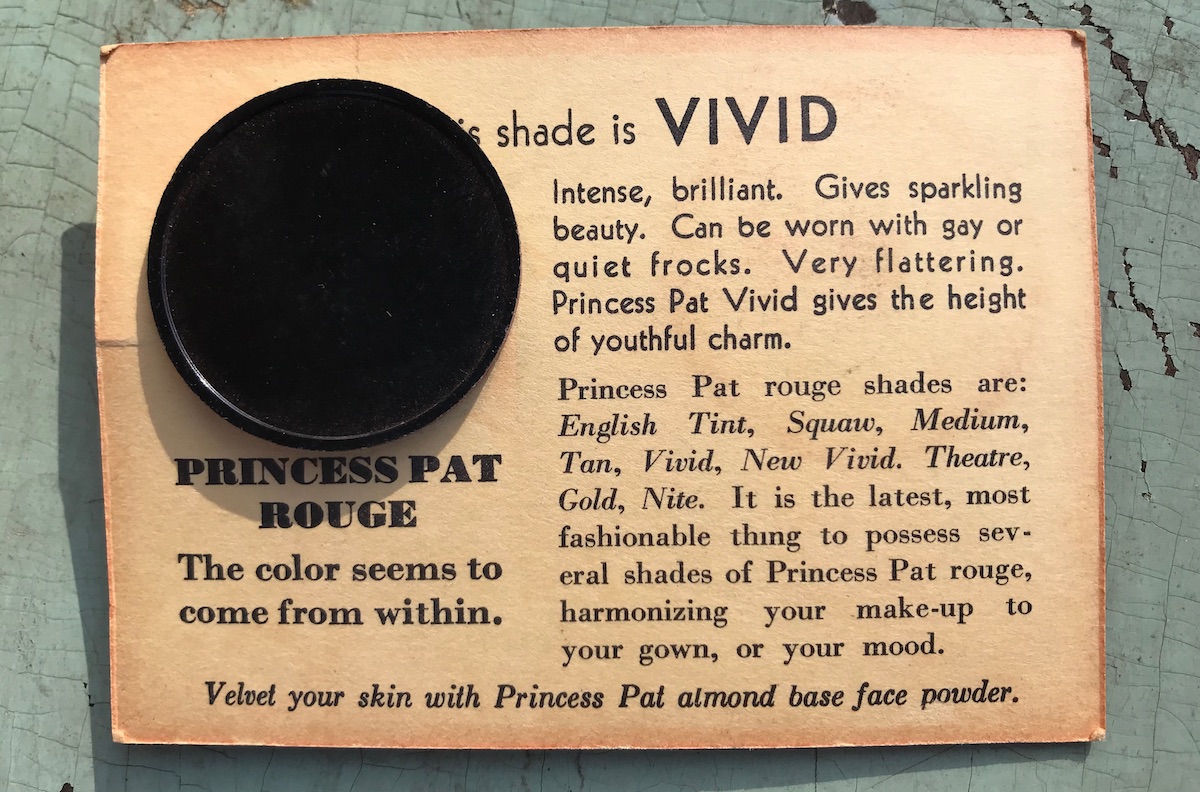

“Rouge that appears artificial defeats the very purpose for which you use rouge,” Patricia Gordon explained in a 1932 advertisement in Silver Screen magazine. “Choose, then, the one rouge of which it may truly be said, ‘the color actually seems to come from within the skin.’ This one rouge is Princess Pat—because none other possesses the almost magical secret of the famous duo-tone blend.

“Each shade of Princess Pat rouge,” Gordon continued, “possesses a mystical underglow to harmonize with the skin, and an overtone to give forth vibrant color. Too, Princess Pat rouge changes on the skin, adjusting its intensity to individual need.”

“Each shade of Princess Pat rouge,” Gordon continued, “possesses a mystical underglow to harmonize with the skin, and an overtone to give forth vibrant color. Too, Princess Pat rouge changes on the skin, adjusting its intensity to individual need.”

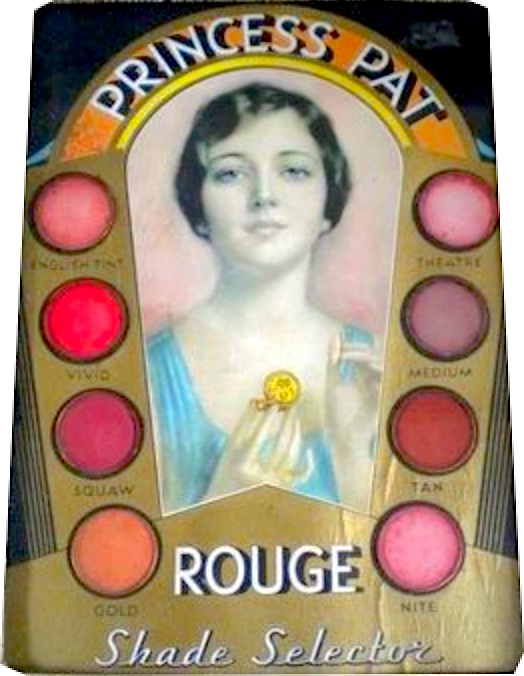

The promise with this product seemed to be—rather ludicrously I suppose by current standards—that “all eight shades” of Princess Pat Duo-Tone Rouge would “match every skin.” So no matter which of the snootilly named shades you selected—Vivid, Squaw, Theatre, English Tint, Gold, Medium, or Tan—the result would “harmonize with your gown—to be brilliant or demure—to be fashionably different. . . . To look as you desire to feel.”

Given the unofficial racial segregation of the cosmetics industry during this period, we’re left to assume that “every skin” probably meant “from white to very white.” Even so, there was a growing audience out there for what Princess Pat was selling, and the astute leader of the company clearly knew how to reach them.

II. Processes and Princesses

Frances Berezniak’s road to becoming Patricia Gordon started in 1895, when—at the age of 8—her family arrived in America and took on a new anglicized surname, “Berry.” Two years later, unbeknownst to young Fannie Berry, another family of Russian Jewish immigrants, this time re-christened the Gordons, settled nearby in Chicago’s West Town neighborhood. One of those Gordon kids, Max Martin Gordon, would go on to attend Northwestern University with Fannie, as they each worked their way to Pharmacy degrees in 1905 and 1906, respectively.

[The wife/husband team behind Princess Pat: Frances B. “Patricia” Gordon and Max Martin Gordon]

[The wife/husband team behind Princess Pat: Frances B. “Patricia” Gordon and Max Martin Gordon]

As newly trained chemists and eventual newlyweds (as of 1907), Berry and Gordon settled into a home at 4620 S. Vincennes Avenue, where they started building up savings to launch their own South Side pharmacy. The couple’s shared work ethic and similar hardscrabble immigrant backgrounds likely gave them a determination and resilience slightly beyond some of their wealthier Northwestern cohorts, and a flair for salesmanship didn’t hurt either. Over time, this early venture spun off into an upstart cosmetics enterprise, which they called simply Gordon Gordon, Ltd.

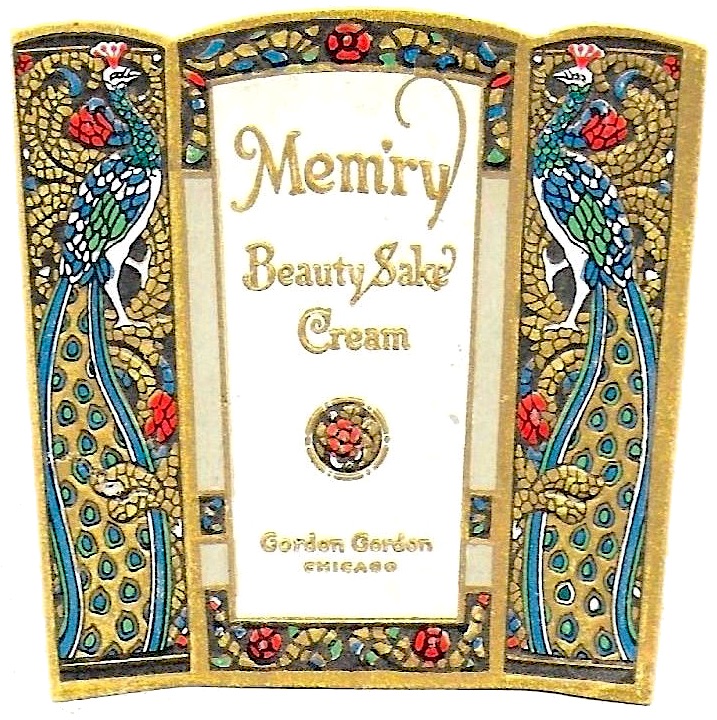

The young entrepreneurs were still in their 20s when they started marketing their earliest homemade beauty products, including everything from anti-odor treatments and skin creams to their first popular rouge formula, which sold under the short-lived “Mem’ry” brand name.

The young entrepreneurs were still in their 20s when they started marketing their earliest homemade beauty products, including everything from anti-odor treatments and skin creams to their first popular rouge formula, which sold under the short-lived “Mem’ry” brand name.

A new Gordon-Gordon perfume, called “Princess Pat,” debuted in 1919, the same year Britain’s lovely Princess Patricia (1886-1974) married naval commander Alexander Ramsay in a much ballyhooed ceremony at London’s Westminster Abbey.

Ramsay was a mere “commoner” by royal standards, so the princess had to publicly relinquish her own royal title during the wedding—a symbolic sacrifice that seemed to add to her romantic appeal among the general public, both in the UK and her adopted Canada. Americans, as ever, were hopelessly attracted to the glitz and glamour, as well, thus inspiring the Gordons to capitalize on the name.

[Painting of the real Princess Patricia of Connaught, by James Jebusa Shannon, c. 1905]

Sure enough, “Princess Pat” swiftly became the company’s hottest selling line in the years after World War I, expanding from perfumes into an assortment of other “beauty aids,” including creams, ice astringents, lip sticks, almond-based face powders, and the first “English Tint” rouge.

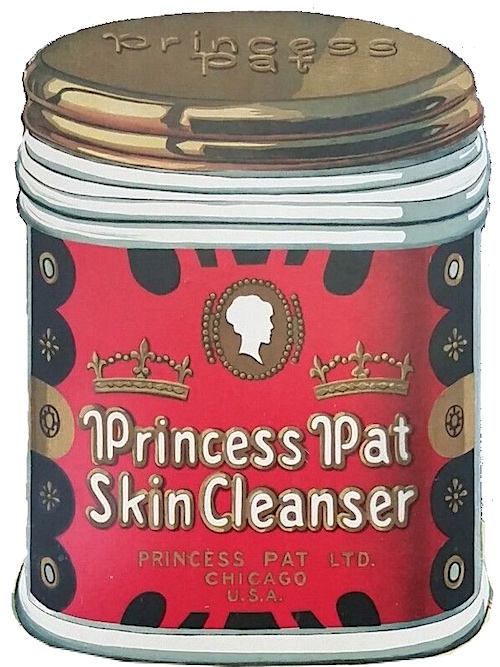

With the new branding came a new style of packaging to match, with fancy medieval fonts; royal red, black and gold coloring; and a pair of primary logos: (1) a coronet fit for a princess and (2) the silhouetted profile of a young woman—easily recognizable as the famed royal lady.

Most of the company’s compacts and other containers were manufactured by a Connecticut supplier, but the Gordons were still very hands-on in determining their form and function, even collecting a few patents in the process—including one for a powder box with a sliding drawer and another for a loose powder dispenser known as the “Tap-It.”

Most of the company’s compacts and other containers were manufactured by a Connecticut supplier, but the Gordons were still very hands-on in determining their form and function, even collecting a few patents in the process—including one for a powder box with a sliding drawer and another for a loose powder dispenser known as the “Tap-It.”

By 1923, as a nation of flappers turned their rosy cheeks to Chicago, Princess Pat was spun off into its own distribution company—Princess Pat, Ltd.—with Gordon-Gordon Ltd. carrying on as the manufacturing wing of the business. M. Martin Gordon was the treasurer of the new venture, and as an important distinction, Fannie Gordon was named both its president and advertising director.

After operating out of a small plant at 2701 South Park Avenue (now MLK Jr. Drive) in the early 1920s, Gordon-Gordon moved to a bigger facility at 2709 South Wells Street by 1925—a stone’s throw from what would eventually become the Dan Ryan Expressway.

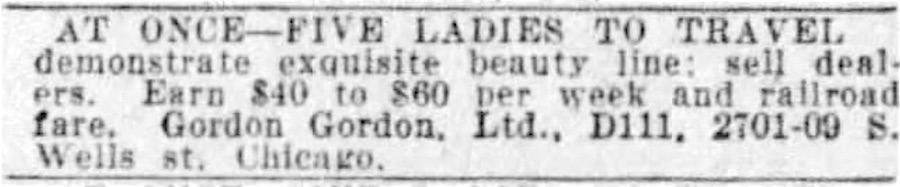

[Wanted ads like this one from 1926 appeared in newspapers across the country, seeking women to sell Princess Pat and other Gordon-Gordon products on the road]

[Wanted ads like this one from 1926 appeared in newspapers across the country, seeking women to sell Princess Pat and other Gordon-Gordon products on the road]

Princess Pat’s small crew of employees were mostly women, paid to prepare all of those lovely new cases and kits for mail order shipments and retail distribution. The traveling sales workforce was almost entirely female, as well—recruited across the country to pound the pavement, knock on doors, and sing the praises of Princess Pat’s “exquisite beauty” regime.

Fannie Gordon was, of course, commander-in-chief among Princess Pat’s workforce. And yet, if you went by U.S. Census records alone, you’d have no way of knowing it. In the 1910, 1920 and 1930 census, alike, her occupation is listed as “none.” A bit perplexing, considering she was actively leading the family business in a multitude of ways—from those patented package designs to product development to writing the lion’s share of the company’s fantastically over-the-top promotional material. The Gordons had no children, so Princess Pat was very much Fannie Gordon’s pride and joy.

[2701-2709 South Wells Street: An earlier, likely unrecognizable version of this building was the Princess Pat / Gordon-Gordon headquarters for over 30 years]

[2701-2709 South Wells Street: An earlier, likely unrecognizable version of this building was the Princess Pat / Gordon-Gordon headquarters for over 30 years]

III. The Woman With Many Names

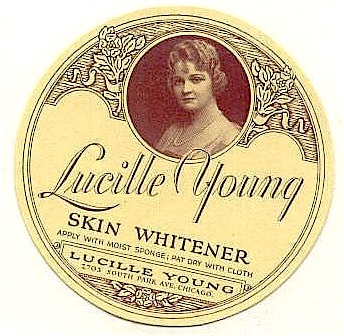

Around the same time Princess Pat was taking off, there was another Chicago-based, mail-order cosmetics business buying up ad space in many of the same movie and fashion magazines. The company was known simply as Lucille Young (headquartered in Chicago’s not-so-famous “Lucille Young Building”), and its namesake spokeswoman was touted as “America’s most widely known beauty expert—a beauty advisor to over a million women.”

“I do two things,” Lucille told her would-be customers in a Silver Screen advertisement. “I correct every defect. I develop hidden beauty. . . . My way of making women over completely is amazingly different. Thousands write me that results are almost beyond belief. Yet every Lucille Young beauty aid is scientific—known to act for all alike. That is why I can guarantee your absolute satisfaction.”

“I do two things,” Lucille told her would-be customers in a Silver Screen advertisement. “I correct every defect. I develop hidden beauty. . . . My way of making women over completely is amazingly different. Thousands write me that results are almost beyond belief. Yet every Lucille Young beauty aid is scientific—known to act for all alike. That is why I can guarantee your absolute satisfaction.”

There was a famous silent film actress during this same period in the 1920s named Lucille Young (no relation to Loretta Young), but as you may have guessed, this was decidedly NOT that person. Lucille Young was, instead, just another alter ego of Fannie “Patricia” Gordon.

In the 1920s and 1930s, it was relatively common for a business to present several different faces to the world. Rather than pigeon-hole itself behind a single brand or identity, casting a wider net offered more avenues for experimenting with different consumer demographics and potentially finding a breakthrough. This certainly seemed to be the Gordons’ strategy in developing the character of Lucille Young, and for maintaining her even as Princess Pat clearly became their real breadwinner.

The use of fictional, figurehead spokesmodels wasn’t solely a marketing strategy in this case, either. As a lover of theater and the arts, Fannie Gordon actually seemed to revel in the opportunity to play the roles of Lucille Young and “Princess” Patricia Gordon, among others. These characters, though exaggerated versions of herself, were represented by real photos of Fannie, who had to have some substantial self confidence to pull off being the living embodiment of exquisiteness.

[These three images of “Lucille Young” (clearly Fannie Gordon) were used routinely in advertisements and packaging during the 1920s and ’30s]

[These three images of “Lucille Young” (clearly Fannie Gordon) were used routinely in advertisements and packaging during the 1920s and ’30s]

“Once I was homely,” Lucille Young admits in one ad. “The portrait above is living proof of what I can do for you, too.”

Such confidence was hard won, and was evident in Fannie Gordon’s work behind the scenes, as well. She wasn’t the only woman to launch or lead a cosmetics business during her time, but she was one of the few who refused to relinquish control of it.

“Of the many firms once owned and operated by women,” fashion writer Catharine Oglesby noted in 1935, “the great majority have passed over into the hands of large companies controlled by men who are directors in large holding companies.” Not so with Princess Pat!

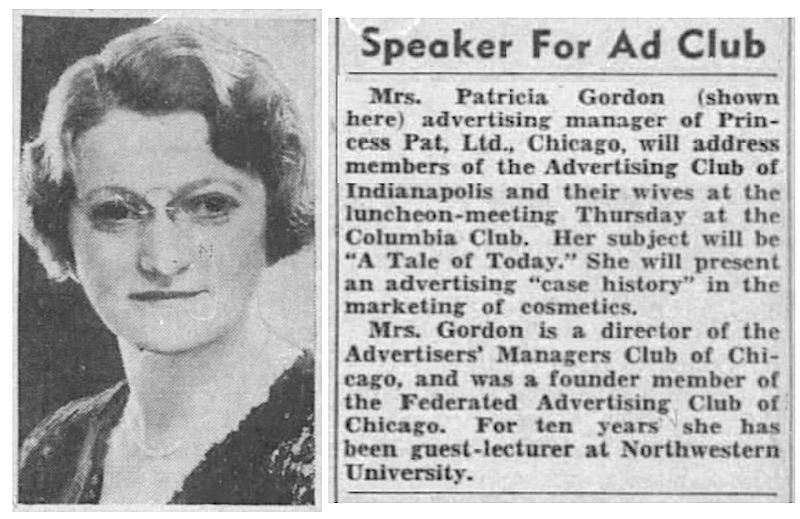

In fact, Fannie Gordon only expanded her involvement in local business circles as time went on, becoming a director of both the Advertisers’ Managers Club of Chicago and the Federated Advertising Club of Chicago, as well as a regular guest-lecturer on business and marketing at Northwestern.

[The Indianapolis News reported on a speaking engagement for Fannie Gordon (by now going by Patricia professionally) at the Ad Club of Indianapolis in April of 1936]

[The Indianapolis News reported on a speaking engagement for Fannie Gordon (by now going by Patricia professionally) at the Ad Club of Indianapolis in April of 1936]

Beyond traditional magazine and newspaper ads, Gordon promoted her brands in unorthodox, long-form promotional booklets and even her own periodical: “Modern Story: A Magazine Devoted to Romance and Beauty.” The articles therein were often personally penned by Fannie, sometimes using her maiden name, Frances Berry, to further throw people off the scent. To say the subject matter had a feminist bent would be debatable (there was no shortage of pulp fiction about using a fine complexion to woo handsome bachelors), but in a time when middle aged women were still deemed largely invisible by the beauty industry, Fannie was arguably quite progressive in her approach.

“There have always been lovely women, but never until this very modern day has there been exquisite perception of beauty—never the same loving, fostering care,” she wrote—under the Patricia Gordon name—in a 1930s Exquisite Beauty booklet. “Not so long ago, there were women who grew old! Why? . . . Because to live for beauty, to cherish the fullness of life, was held unbecoming, indeed wicked. The finger of disapproval pointed out the woman not content to ‘let nature take its course.’ Fair and Forty! Growing old gracefully! What a dreadful philosophy.

“There have always been lovely women, but never until this very modern day has there been exquisite perception of beauty—never the same loving, fostering care,” she wrote—under the Patricia Gordon name—in a 1930s Exquisite Beauty booklet. “Not so long ago, there were women who grew old! Why? . . . Because to live for beauty, to cherish the fullness of life, was held unbecoming, indeed wicked. The finger of disapproval pointed out the woman not content to ‘let nature take its course.’ Fair and Forty! Growing old gracefully! What a dreadful philosophy.

“She of forty today! Ah, the splendor of her, the patrician loveliness—if she has been clever. She, indeed, is the exquisite. In her presence, let ‘sweet sixteen’ beware. Youth, perhaps, needs no adornment—perhaps? But the woman of fuller years is a dangerous rival. Chic? . . . She has it—and a thousand subtle charms. Years have but added grace as she bends silken knee in curtsy. Color, line, softness—they are hers, permanently. The same slim figure, the same creamy satin skin. But an added, intriguing sophistication.”

[Princess Pat advertisements from the early 1930s]

[Princess Pat advertisements from the early 1930s]

IV. “Beauty Editor of the Air”

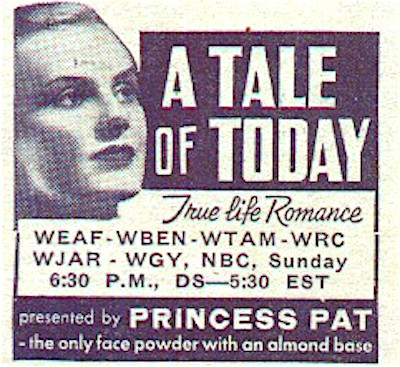

Based on her obvious skill with words and the theatricality of her style, it should come as little surprise that Patricia Gordon soon found her way to the radio airwaves, hosting a show in the early 1930s called “Patricia Gordon: Beauty Editor of the Air,” which was syndicated across much of the country on NBC in 1933 and ’34. She and her husband also sponsored regular programs called the “Princess Pat Dramas” and “A Tale of Today” in the mid 1930s.

One of Patricia’s copywriting assistants during this period of relative celebrity status was a young struggling novelist and playwright named Vera Caspary, who would go on to fame of her own in the 1940s for penning the popular detective novel Laura.

In her autobiography, Caspary [pictured] describes giving a speech to the Chicago Council of Jewish Women in 1933, encouraging the “bourgeois ladies” of the group to consider the serious threat that Naziism was beginning to pose in Europe. While most of the women “remained smugly certain that nothing serious could happen to nice Jewish people who minded their own business,” Caspary’s words found a more sympathetic audience in “my royal patron Princess Pat—otherwise Fanny Gordon, for whom I’d written copy on mail-order beauty.

In her autobiography, Caspary [pictured] describes giving a speech to the Chicago Council of Jewish Women in 1933, encouraging the “bourgeois ladies” of the group to consider the serious threat that Naziism was beginning to pose in Europe. While most of the women “remained smugly certain that nothing serious could happen to nice Jewish people who minded their own business,” Caspary’s words found a more sympathetic audience in “my royal patron Princess Pat—otherwise Fanny Gordon, for whom I’d written copy on mail-order beauty.

“She had deserted her business that afternoon,” Caspary wrote, “to hear her protégée lecture ladies who had not worked for their bread and mink, and had looked down their long noses at the daughter of a Russian Jew when she had served them in the drugstore where she and her husband had mixed the rouge that was the foundation of their fortune.

“Mrs. Gordon had gone into the fiction business, not the fictions of cosmetic advertising but the drama of radio publicity. Although she had a keen ear for the clink of dollars, it was not for profit alone that she had become a producer of weekly shows. As a girl she had studied elocution and still fancied herself a gifted actress. The radio plays were secondhand theatre and when she swept into the studios, she was greeted with no less reverence than those princes who had established theatres and produced spectacles out of royal conceit.”

[“A Tale of Today” was one of a number of radio programs sponsored by Princess Pat, with promotional intros often provided by Patricia Gordon herself]

[“A Tale of Today” was one of a number of radio programs sponsored by Princess Pat, with promotional intros often provided by Patricia Gordon herself]

This was the Fannie/Patricia Gordon dynamic in a nutshell—striving for high art, but rooted in her early working class experience. Both of these elements came through in 1934, when she won attention for exploits in another field of entertainment, assisting in the composition of an award winning orchestral suite based on the low brow characters of Vaudeville.

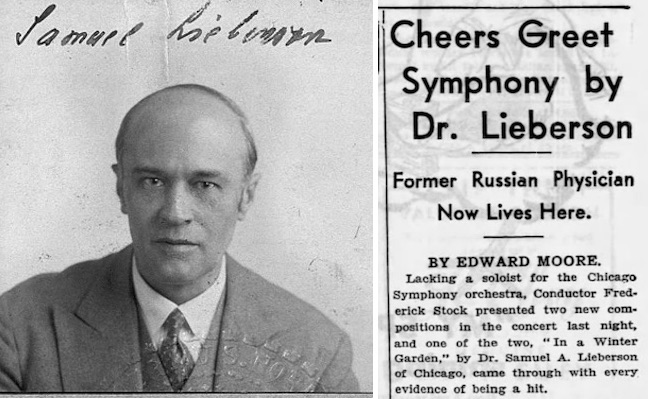

“A peep into the private lives and hobbies of radio personalities is always interesting,” the Northwestern University Alumni News reported, “and sometimes surprising. One of these ‘peeps’ reveals Patricia Gordon (Mrs. M. Martin Gordon, Pharmacy ’06), better known as ‘Princess Pat,’ creator of cosmetics (whose voice is familiar to NBC chain listeners), as a patron of the arts and the commissioner of the Orchestral Suite ‘In a Winter Garden,’ which captured the prize for Dr. Samuel Lieberson at the Hollywood Bowl last year.

“. . . Dr. Lieberson [pictured] was attending a musical evening at the Gordon home in the summer of 1933 when the hostess, Patricia Gordon, outlined her idea of a composition reflecting the highlight of Vaudeville. The composer was intrigued with the idea and accepted the commission. The score was finished, acclaimed, and awarded the prize at the Hollywood Bowl. The composer, Dr. Lieberson, dedicated the score to Patricia Gordon.”

“. . . Dr. Lieberson [pictured] was attending a musical evening at the Gordon home in the summer of 1933 when the hostess, Patricia Gordon, outlined her idea of a composition reflecting the highlight of Vaudeville. The composer was intrigued with the idea and accepted the commission. The score was finished, acclaimed, and awarded the prize at the Hollywood Bowl. The composer, Dr. Lieberson, dedicated the score to Patricia Gordon.”

The suite, which Patricia had fully conceptualized and sketched out, was the most successful work of Samuel Lieberson’s career, and eventually enjoyed a run with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Sadly, it was never given a proper recording, and has since been essentially forgotten.

[Promotional Princess Pat pastel art by F. Earl Christy, late 1920s]

[Promotional Princess Pat pastel art by F. Earl Christy, late 1920s]

V. Cease and Desist

While radio dramas and orchestral suites might seem far removed from the business of selling make-up, a small business had to be creative during the Depression. Any press, as they say, was good press.

For his part, Max Martin Gordon refused to acknowledge that Princess Pat or Gordon-Gordon were actually suffering any ill effects from the economic fallout at all.

“The organization has not cut salaries,” he said in a 1932 interview, “nor let out competent employees, nor ruthlessly slashed operating expenses. Instead, new products have been perfected, new merchandising policies adopted, and selling effort intensified, and in this its officers take great pride.”

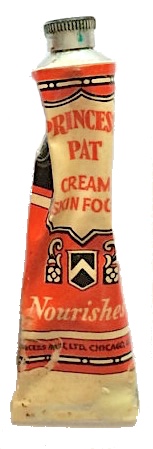

Of all the company’s products, the already discussed Duo-Tone Rouge was among the most consistent sellers in the ’30s, now offered in simpler, modern packaging, as the aristocratic and geometric deco flourishes of the ‘20s were largely curbed.

Of all the company’s products, the already discussed Duo-Tone Rouge was among the most consistent sellers in the ’30s, now offered in simpler, modern packaging, as the aristocratic and geometric deco flourishes of the ‘20s were largely curbed.

Loretta Young’s famous face certainly helped keep the goods moving, and Patricia Gordon’s flowery radio diatribes about “exquisiteness” played their role, too, but these efforts were always balanced out with important claims of scientific legitimacy—proven results based on “years of research.”

As early as 1926, a company booklet called “Devoted to Beauty” described how “It is not strange that millions of women should have come to regard Princess Pat, Ltd., as the house of discoveries in matters pertaining to beauty. For each Princess Pat Beauty Requisite is a distinct discovery—a definitely individual, scientific idea for complexion beauty and betterment, in full accord with nature.”

Unlike your typical Jazz Age hucksters, the Gordons really did have professional training and degrees in pharmaceutical studies from a very reputable university. So it’s at least plausible that they believed their own hype. Still, there were plenty of raised eyebrows from skeptics, particularly regarding the company’s adherence to quacky theories on skin health.

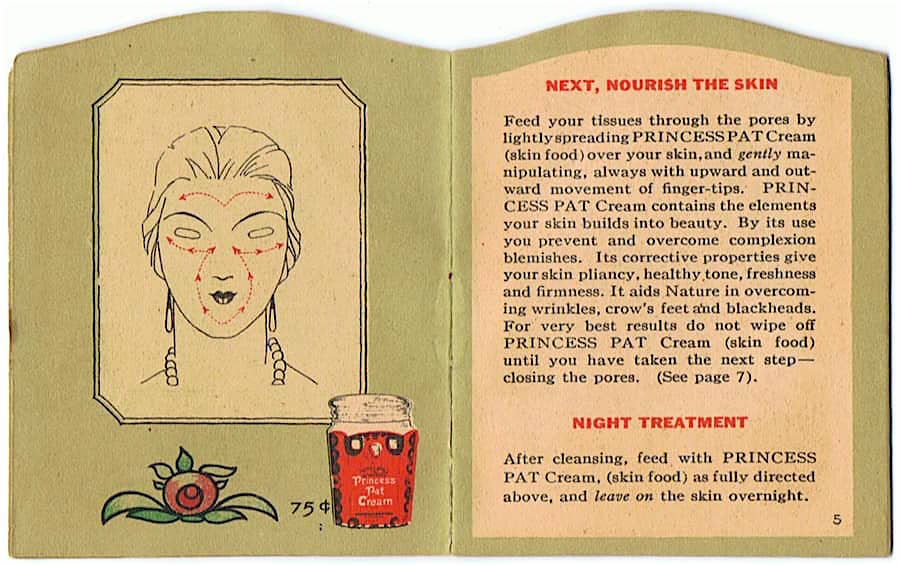

According to Patricia Gordon’s writings, for example, Princess Pat’s “Skin Food” Cream literally fed the tiny mouths of the face (aka, the pores) for nourishment, just as you’d put vegetables through your actual mouth. Princess Pat Ice Astringent, meanwhile, safely closed the pores back up to keep out damaging dust and germs. The result: “a fine grained, youthful skin texture.”

[A lot of Princess Pat’s beauty care language revolved around the idea of “feeding” the skin through the pores for cosmetic and nutritional benefits]

[A lot of Princess Pat’s beauty care language revolved around the idea of “feeding” the skin through the pores for cosmetic and nutritional benefits]

Pushback on such claims was pretty feeble until 1939, when the Federal Trade Commission finally started cracking down on false advertising throughout the cosmetics industry.

When the FTC’s two-year investigation of Princess Pat concluded in 1941, they pulled no punches, charging Princess Pat, Ltd. and Gordon-Gordon Ltd. with “the use of unfair methods of competition in commerce and unfair and deceptive acts and practices in commerce.” According to the Commission, just about every product in the Princess Pat line failed to do what it promised.

“Skin Food Cream will not nourish the skin” / “Skin Cleanser will not penetrate the surface of the skin or prevent coarse pores, pimples, etc.” / “Muscle Oil will not prevent crow’s feet, wrinkles, and sagging muscles.”

“Skin Food Cream will not nourish the skin” / “Skin Cleanser will not penetrate the surface of the skin or prevent coarse pores, pimples, etc.” / “Muscle Oil will not prevent crow’s feet, wrinkles, and sagging muscles.”

“. . . [Princess Pat’s] use of the aforesaid false and misleading statements, and representations disseminated as aforesaid, has had, and now has, the capacity and tendency to mislead and deceive members of the purchasing public into the erroneous and mistaken belief that the aforesaid statements and representations are and were true, and into the purchase of substantial quantities of Princess Pat products because of such erroneous and mistaken belief.”

In other words, the U.S. Government had determined that Princess Pat was, in fact, a snake oil saleswoman. Certainly not a good look for a monarch, and yet, surprisingly, not the end of this particular story.

VI: Finishing Touches

In 1940, shortly before the FTC’s decision was announced, a survey found that Princess Pat’s famed Duo-Tone Rouge still ranked among the Top Five most popular brands in America, trailing only Luxor, Max Factor, Lady Esther, and Richard Hudnut. Princess Pat lipstick was also a Top 10 finisher in its field.

Maintaining that popularity wasn’t going to be easy once the U.S. Government ordered the Gordons to cease and desist from the style of marketing that had largely defined their business for 30 years. On the bright side, though, they weren’t alone. Dozens of other cosmetics companies had been targeted and reprimanded as part of the same crackdown, so in some respects, everyone was moving into the 1940s on equal footing.

The next challenge, of course, was World War II, when women left behind the glamour for the factories, and rationing limited the availability of supplies. The whole industry was put on the back burner, but Princess Pat’s situation was more like an open flame.

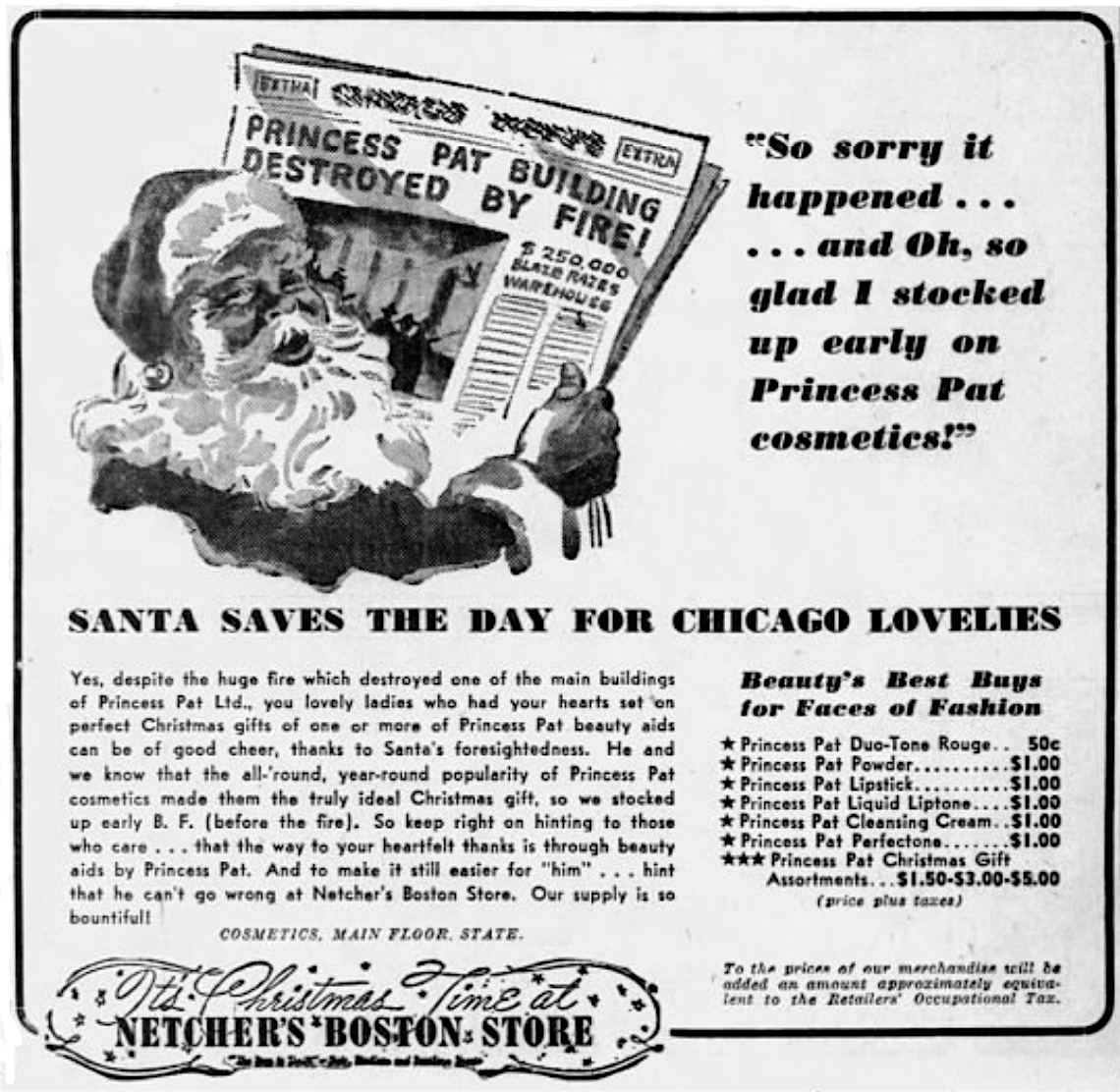

In December of 1943, smack in the middle of the war, the company made national headlines after its “main manufacturing and storage plant” caught fire (according to the United Press), destroying an estimated $250,000 worth of back-stock cosmetics. None of the articles about the blaze mention the address of the building—only that it was “destroyed.” Since Princess Pat was running classified ads three weeks later looking for file clerks at the usual 2709 South Wells Street headquarters, however, we can assume that this story was either exaggerated in terms of damages, or inaccurate in terms of location (presumably, it could have been a warehouse, rather than the company’s main plant).

In December of 1943, smack in the middle of the war, the company made national headlines after its “main manufacturing and storage plant” caught fire (according to the United Press), destroying an estimated $250,000 worth of back-stock cosmetics. None of the articles about the blaze mention the address of the building—only that it was “destroyed.” Since Princess Pat was running classified ads three weeks later looking for file clerks at the usual 2709 South Wells Street headquarters, however, we can assume that this story was either exaggerated in terms of damages, or inaccurate in terms of location (presumably, it could have been a warehouse, rather than the company’s main plant).

[Just days after the Princess Pat building fire, Netcher’s Boston Store in Chicago happily promoted its un-burnt stock of the company’s goods, ready to sell for Christmas]

[Just days after the Princess Pat building fire, Netcher’s Boston Store in Chicago happily promoted its un-burnt stock of the company’s goods, ready to sell for Christmas]

Around this same time, harking back to their old Lucille Young playbook, Max Martin and Patricia had organized another separate business, the Glamr Girl Cosmetic Co. (headquartered at 221 W. 27th Street, which is the same building as 2709 S. Wells St.), to give them a potential revenue stream outside the damaged Princess Pat brand. It never made much of a dent.

By the early 1950s, the Princess Pat offices in Chicago still employed a team of 60 workers, and according to Patricia Gordon’s own testimony in a random 1951 trademark case, their client list included: “Marshall Field, Mandel Brothers, Carson Pirie Scott & Company, Bloomingdale, Macy’s, May Company, Walgreen, Whelan, Stineway Drug Company, Broadway Department Store . . . practically every worthwhile store in the United States and Canada; Simpson’s, Eaton’s, Sanborn’s in Mexico; and all over the world, practically.” And yet, with Princess Pat’s chief officers now in their sixties and no longer quite in sync with modern notions of “exquisiteness,” momentum—and sales—were slowing. Following the death of M. Martin Gordon in 1955, the end was clearly near.

By the early 1950s, the Princess Pat offices in Chicago still employed a team of 60 workers, and according to Patricia Gordon’s own testimony in a random 1951 trademark case, their client list included: “Marshall Field, Mandel Brothers, Carson Pirie Scott & Company, Bloomingdale, Macy’s, May Company, Walgreen, Whelan, Stineway Drug Company, Broadway Department Store . . . practically every worthwhile store in the United States and Canada; Simpson’s, Eaton’s, Sanborn’s in Mexico; and all over the world, practically.” And yet, with Princess Pat’s chief officers now in their sixties and no longer quite in sync with modern notions of “exquisiteness,” momentum—and sales—were slowing. Following the death of M. Martin Gordon in 1955, the end was clearly near.

In 1960, the Chicago Tribune noted the death of “Patricia B. Gordon, president of Princess Pat Cosmetic company,” but there were no accounts of the remarkable achievements of a girl named Fannie Berezniak. “Mrs. Gordon was a philanthropist,” her obituary read, “but shunned publicity on her activities.” And so maybe that’s the way she always preferred it. Ever the actress, “Princess Pat” enjoyed connecting with the world through characters, makeovers, and magic potions. It was all a bit of a performance, and as an unfortunate consequence, we’ll never fully know the hardworking woman behind the rouge.

Interestingly, there is still a cosmetics research and manufacturing company in Carson, California known as Gordon Labs, Inc., which claims to trace its roots back to a west coast wing of the business M. Martin Gordon organized in 1937. This has proven difficult to substantiate.

SOURCES:

Modern Story Magazine, No. 9, 1931

This Exquisite Beauty, pub. by Princess Pat, Ltd., c. 1930

Devoted to Beauty, pub. by Princess Pat, Ltd., 1926

Hope In a Jar: The Making of America’s Beauty Culture, by Kathy Peiss, 1998

The Secrets of Grown-Ups: An Autobiography, by Vera Caspary, 1979

“Speaker for Ad Club” – Indianapolis News, April 7, 1936

“In the Matter of Gordon-Gordon LTD and Princess Pat PTD” – Federal Trade Commission Decisions, Vol 32, 1940-41

“Princess Pat: The Real Story of This Cosmetics Brand” – Collecting Vintage Compacts

“Princess Pat” – Cosmetics and Skin

“$250,000 Cosmetics Loss” – The Lincoln Star, December 8, 1943

“Nettie Rosenstein, Inc., Appellant-applicant, v. Princess Pat, Ltd., Appellee-opposer,” 220 F.2d 444, U.S. Court of Customs and Patent Appeals, March 22, 1955

“Mrs. P. Gordon Dies; Headed Two Make-Up Firms” – Chicago Tribune, Aug 6, 1960

“Dr. Lieberson Dedicates Score to Patricia Gordon” – Northwestern University Alumni News, Vol. 14, May 1935

Yesterday, November 19, 2024 I found a Princess Pat metal compact about the size of a quarter at Ohio Street Beach. Has it been in the lake all these years? It has an Art Deco motif on it; the water logged metal coloring is a deep browny eggplant color and simply says Princess Pat on the front, nothing on the back. I can’t open it and appears to be water tight all these Years as I can hear movement inside when I shake it. I am an antique lover and will keep this treasure as I have found it among the rocks at the beach.

I have a blue Gordon Gordon peacock label bottle….no cork. It’s beautiful…

Hola buenas tardes en un lote que compre me salió el último cuadro de princess pat rouge shade selector me gustaría sabe más sobre el

The “Gordon Labs” in California has absolutely nothing to do with the Gordons from Chicago. California state records clearly show that the California company now called Gordon Laboratories was originally named “H.B. Gordon Manufacturing Co., Inc” and registered in 1967 long after Patricia and Martin passed away. The California company was only renamed Gordon Laboratories in 2004 and seems to be exploiting the name and legacy of the Gordons from Chicago. There is no proof the Gordons or Princess Pat, Inc. had any connection to the California business nor is there evidence of a “west coast wing” of the Chicago-based company. Curiously, there was an earlier Gordon Laboratories established in California (1965 – 1971) for the manufacture of cosmetics and toilet preparations but it dissolved.

I have just a few small promotional materials from Princess Pat. One is the book “The Exquisite Beauty” in excellent shape. I have a rogue shame guide and a couple other things. I would donate them somewhere if someone will tell me where to send them Thank you. Such interesting history!

Hi,

I am a princess pat collector. please contact me if you would like donate/sell?

Hi, I’m Kitty…When I was young girl my family moved into an old house filled with junk. We bought the house as is, My mother found an old vase out on the back porch that had an old compact in it. It was about as big as a quarter and, perhaps, a forth of an inch deep. It was filled with greasy red lipstick that was to be applied with the finger. On the compact was the picture of woman from the early 1900’s. It read, “Princess Pat Lip Rouge. Makes laughing parted lips adorable” My mother laughed when she found it. It’ a simple childhood memory, but as I sit here now at 74n years old, I wish I could find one.

Hello,

I had a rogue box with princess pat Ltd name on the back given to me in childhood…to play with, by my maternal grandaunt who was a spinster and had died of b. Cancer. This box was very dear to me and I had left it at home ( my mom’s place) and moved on with my life. Once when mom came to visit me she found some of my things and photographs of school and college and brought this box and gave it to me …I was thrilled to see it and always wanted to know about the history behind this rouge….it was exciting and fascinating to read this page and know that I have a treasure with me from the 1920s …I was so happy to find this page on the internet…😊