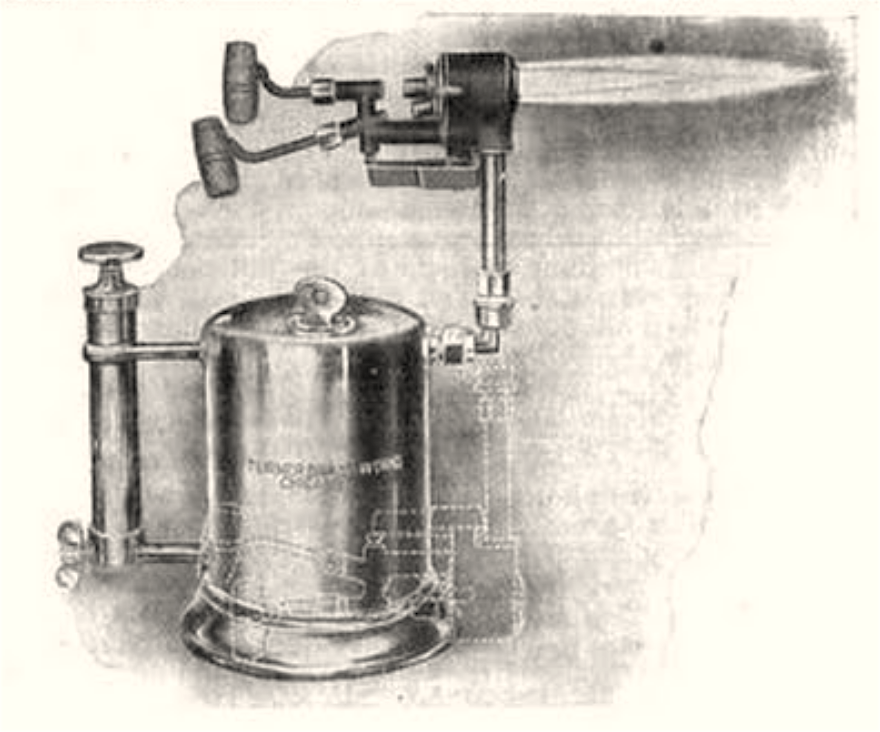

Museum Artifact: Turner-White “Hot Blast” Blow Torch, c. 1905

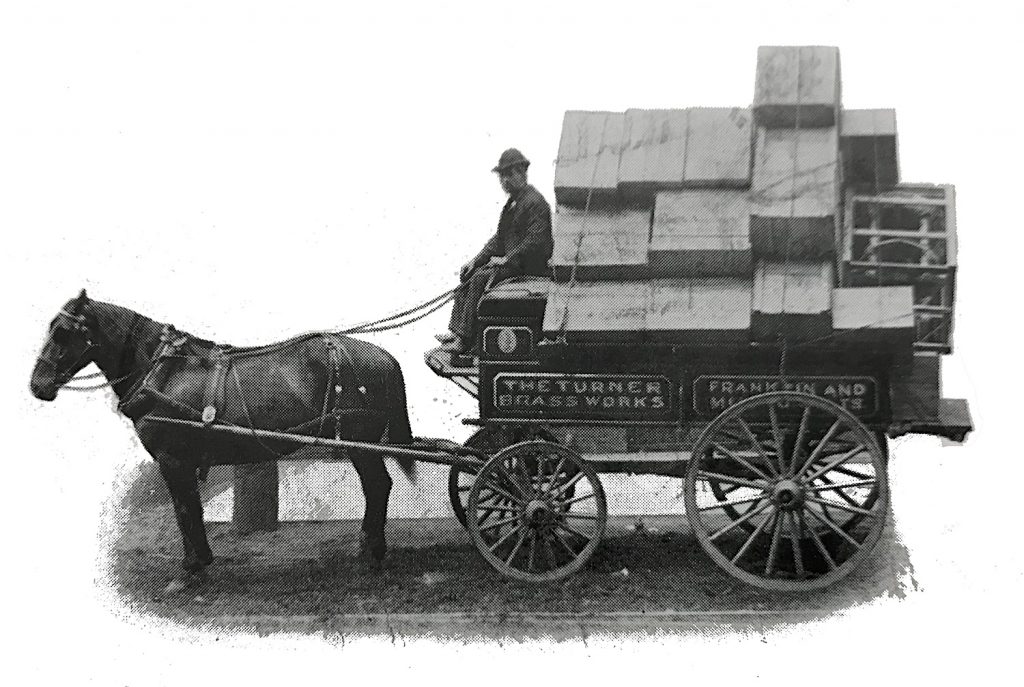

Made By: Turner Brass Works, N. Franklin St & Michigan Street (now 225 W. Hubbard St.), Chicago, IL [River North]

“A pint torch for general light work, constructed with our improved automatic brass pump in the tank. The burner is of heavy bronze, strong and durable. For electricians, painters, etc., we guarantee it to give perfect satisfaction.”—description of the White No. 7 “Hot Blast” torch, from the 1905 Turner Brass Works catalog

For almost 90 years, the Turner Brass Works was part of the fabric of the community of Sycamore, Illinois—a small town about an hour west of Chicago. As a 1925 issue of Sycamore’s newspaper The True Republican put it, “the world’s largest exclusive manufacturer of blow torches, fire pots and braziers carry the name of Sycamore to every corner of the globe and thus does the lion’s share in advertising its home city.”

For almost 90 years, the Turner Brass Works was part of the fabric of the community of Sycamore, Illinois—a small town about an hour west of Chicago. As a 1925 issue of Sycamore’s newspaper The True Republican put it, “the world’s largest exclusive manufacturer of blow torches, fire pots and braziers carry the name of Sycamore to every corner of the globe and thus does the lion’s share in advertising its home city.”

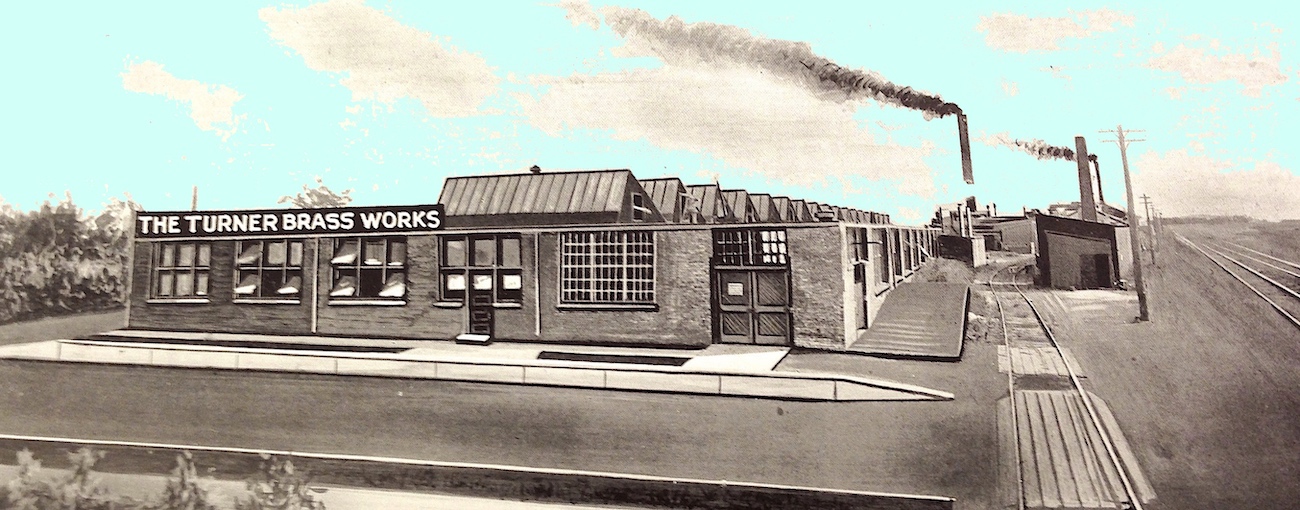

Turner’s Sycamore plant [pictured below] remained in operation all the way into the late 1990s, when it finally shut its doors and met the wrecking ball. There were countless memories made there over multiple generations, but alas, we won’t really be discussing them here.

Why? Well, because the Turner blow torch in our collection wasn’t actually made in Sycamore. It was forged in downtown Chicago, shortly before the company’s relocation.

[The Turner Brass Works in Sycamore, IL, which opened in 1907, is seen here in 1918]

[The Turner Brass Works in Sycamore, IL, which opened in 1907, is seen here in 1918]

In fact, we can pretty well pinpoint the date of origin of our torch to a small three-year window between 1904—the year Turner acquired the patents and “Hot Blast” trademark of their Chicago rivals, the White MFG Co.—and 1907, when the Sycamore era began.

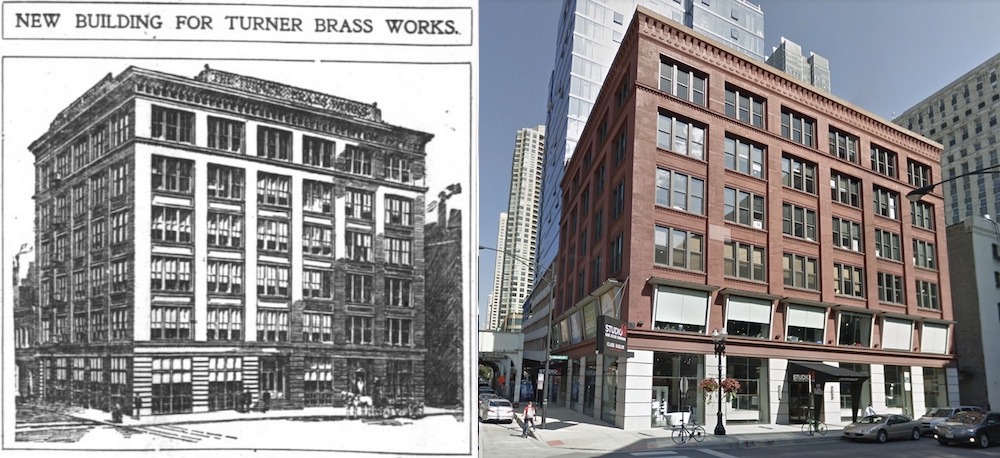

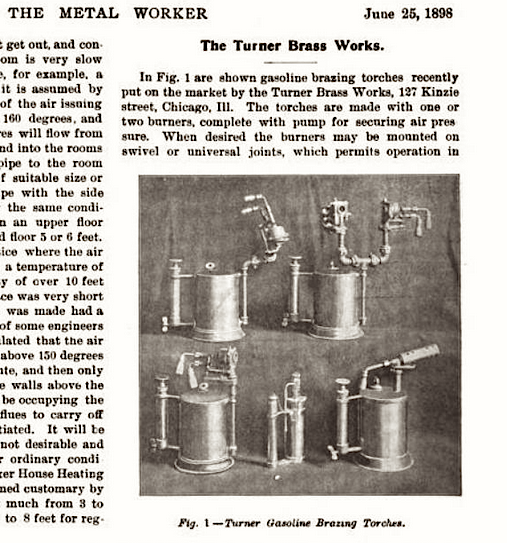

During this period, Turner Brass was headquartered inside a six-story plant in River North, at the corner of Franklin Street and Hubbard Street (then known as Michigan Street). The complex had been built in 1901 to consolidate Turner’s various other foundries and assembling plants into one facility. Here, “a variety of over 80 torches, fire pots, and braziers are now manufactured under one roof,” according to a 1904 issue of the Western Electrician. “Their factory covers one quarter of a block and is equipped with the latest types of machinery and special facilities for the manufacture of mechanical heat appliances.”

[The former Turner Brass Works plant in Chicago (1901-1907) is still standing, and looking better than ever, at 225 W. Hubbard St.]

[The former Turner Brass Works plant in Chicago (1901-1907) is still standing, and looking better than ever, at 225 W. Hubbard St.]

Turner’s own 1905 torch catalog describes the Chicago business, with the addition of the White MFG Co. arsenal, as the “largest concern in the world engaged in the manufacture of up-to-date improved gasoline, kerosene, alcohol and gas appliances,” and mentions separate catalogs available for automobile specialties, hardware, name plates, gas vapor and arc lamps, brass figures, and more.

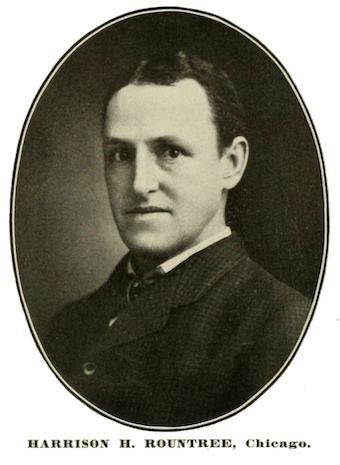

As one might expect, things could occasionally get a bit chaotic inside a 56,000 sq. ft. manufacturing space, packed with more than 200 tradesmen more accustomed to working in their own familiar circles. Adding fuel to the fire, so to speak, was Chicago’s escalating labor movement, as workers unions were increasingly motivated to protest and strike against unfair treatment. During these uprisings, Turner’s president—a young sophisticate named Harrison Hawkins Rountree—wasn’t always on the right side of history. But he did leave his mark in other ways, including using some of his brass cash to help finance (and potentially inspire) one of the best-selling novels in American history.

The Man Behind the Curtain

Harrison Rountree was just 34 years old when he took over the reins of the Turner Brass Works in 1889, buying out the company’s founder and namesake Edward S. Turner, who was stepping aside after 18 years in the game. Turner’s original Chicago brass foundry, E.S. Turner & Co., had barely been in business three months when it was wiped out by the Great Fire of 1871. With no sense of irony, the firm swiftly rose from those ashes to become “a pioneer in the manufacture of mechanical heat appliances” and “among the first to manufacture a line of gasoline torches” (Western Electrician, 1904). If anybody was gonna be burning things up in his city, Turner decided, it was gonna be him.

By comparison, Harrison Rountree was a neophyte to the blast furnace biz. The son of a former prominent Wisconsin state senator (John Hawkins Rountree) and brother-in-law to a leading Chicago publisher (Chauncey L. Williams), “Harry” himself was a lawyer by trade. In fact, he was part of the law firm that helped negotiate E.S Turner’s buyout and the incorporation of the Turner Brass Works. Installing himself as company president might then sound like a massive conflict-of-interest situation, but in Wild West Chicago, there were few objections.

By comparison, Harrison Rountree was a neophyte to the blast furnace biz. The son of a former prominent Wisconsin state senator (John Hawkins Rountree) and brother-in-law to a leading Chicago publisher (Chauncey L. Williams), “Harry” himself was a lawyer by trade. In fact, he was part of the law firm that helped negotiate E.S Turner’s buyout and the incorporation of the Turner Brass Works. Installing himself as company president might then sound like a massive conflict-of-interest situation, but in Wild West Chicago, there were few objections.

Moving into an expanded company headquarters at the corner of Kinzie Street and Wells Street, Rountree immediately started the process of combining his business acumen with the Turner Brass Works’ ample production line of torches, furnaces, dental prosthetics(!), and primitive bicycle and automobile accessories.

“This,” according to a retrospective Chicago Tribune fluff piece in 1904, “was the substantial beginning of an enterprise which has been commensurate with the growth of the city itself. As the latter has taken in suburb after suburb and enlarged its boundaries time after time, so the Turner Brass Works corporation, by reason of continuous growth, has repeatedly branched out and extended its facilities.

“. . . Behind it all, of course, is the excellent and well established reputation of the company and the popularity of its products, which are the result of the most improved methods of metal manufacture supplemented by artistic and well directed effort along every line.”

Cool Cats to Hang With

When not skillfully directing his business, Harrison Rountree was working the rooms of Chicago’s high society. He was far from the classic cigar-chomping tycoon, however, preferring to keep more sensitive, artistic company. His social circle included a young architect named Frank Lloyd Wright, the proto-feminist author Kate Chopin, and artist Orlando Giannini, who created the original concept for the gymnast image that would long serve as the Turner Brass Works’ logo.

Also in amongst this crowd was a struggling children’s book writer by the name of Lyman Baum—better known to his small readership as L. Frank Baum. But we’ll get to him in a minute.

Also in amongst this crowd was a struggling children’s book writer by the name of Lyman Baum—better known to his small readership as L. Frank Baum. But we’ll get to him in a minute.

Anyway, Rountree and his wife Lillian, a writer herself, would host these various interesting people at fancy dinner parties, presumably discussing little of the daily goings on at the brass factory. As a “society lady,” Lillian also had her own rather extraordinary commitments, including an active membership in the “Chicago Cat Club,” which hosted the city’s annual competitive “Cat Show” in the 1890s.

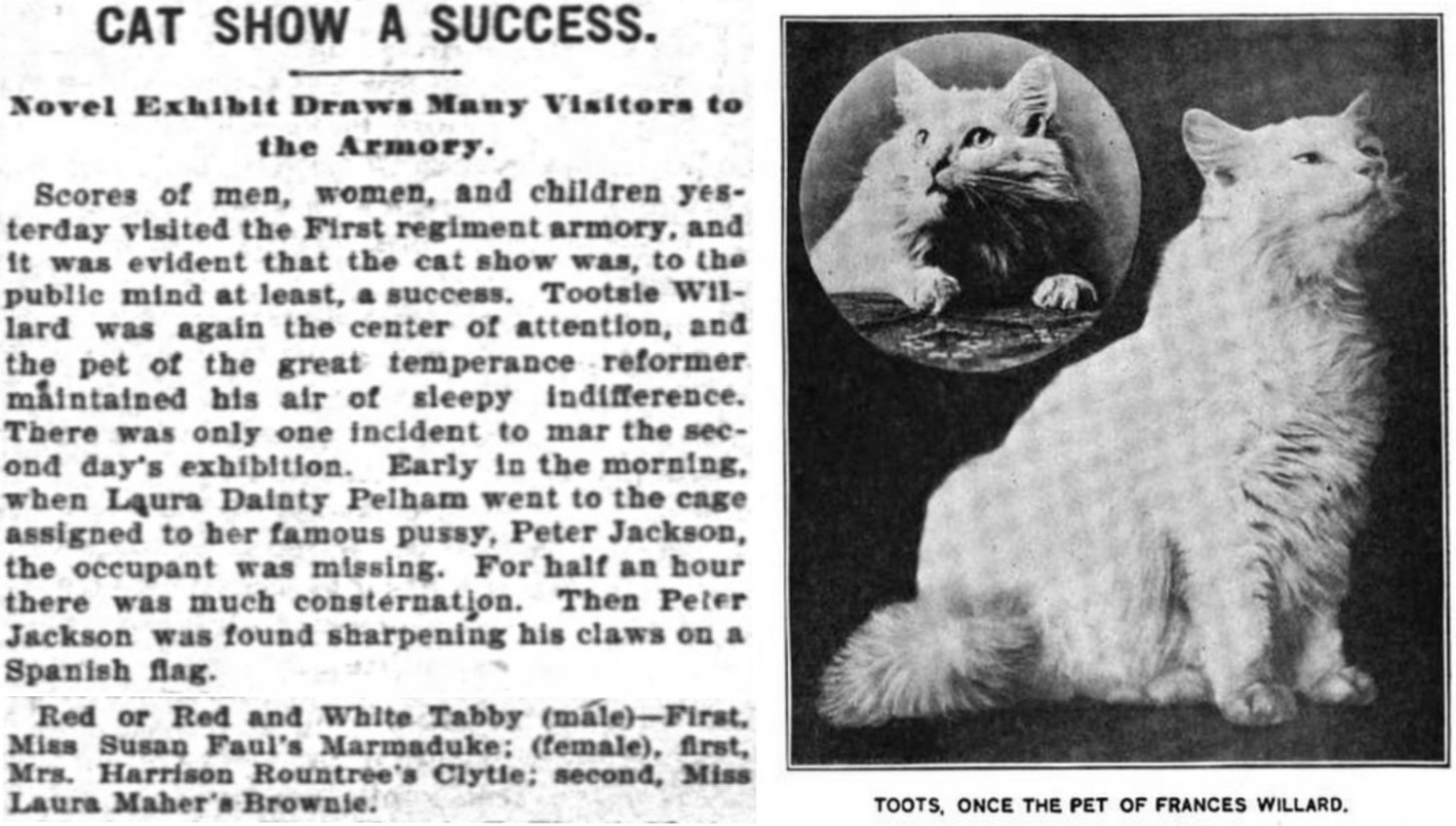

The Rountrees’ own tabby “Clytie” won a prize in the ginger cat category, as I’m sure you’ll be pleased to know. It was “Tootsie Willard” who was “again the center of attention,” however.

[Chicago Cat Show results, as published in a 1898 issue of The Inter Ocean, describe the fine showing of Turner Brass president Harrison Rountree’s cat “Clytie.” The accompanying photo of champion cat “Toots” comes from a 1900 issue of Metropolitan. Yes this is all real.]

[Chicago Cat Show results, as published in a 1898 issue of The Inter Ocean, describe the fine showing of Turner Brass president Harrison Rountree’s cat “Clytie.” The accompanying photo of champion cat “Toots” comes from a 1900 issue of Metropolitan. Yes this is all real.]

Also joining in the feline festivities was Harry Rountree’s young adopted daughter Dorothy, who became president of the “Chicago Children’s Cat Club” in 1899, at the age of nine. The goal of the new club, according to a 1900 article in Metropolitan, was “to make its members humane and sympathetic toward all dumb creatures, and to instruct them in the special branch of catology. The annual fee is twenty five cents and all the funds of the club are used to support a refuge for stray and homeless cats.”

It may or may not be a coincidence that, one year later, “Dorothy” also became the name of the young protagonist in a certain L. Frank Baum novel that you might have heard of, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900).

Sure, Toto probably would have been a cat if that were the case (and others have cited Baum’s niece as the true inspiration), but there’s no doubt that Baum and Harry Rountree had become good buddies long before Oz was published, and that Frank and his wife Maude knew the whole Rountree family very well. Harry was also a major supporter and financier of some of Baum’s early projects, and Baum, in turn, dedicated his 1898 book By the Candelabra’s Glare to his close friend.

Years later, Rountree was appointed the trustee of Baum’s estate after the author’s attempt at putting together a traveling show resulted in his bankruptcy. For a while, Rountree was in charge of the royalties from many of Baum’s works, including The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, although he sold them back to Frank’s widow Maude Gage long before the subsequent Hollywood film made it an even greater cash cow.

If you care to make the effort, you could potentially find other elements of Harrison Rountree’s influence in Baum’s most famous work. For example, some people think the “Tin Woodman,” aka Tin Man, is intended to represent the de-humanization of workers during the industrial age. That certainly might be putting weight where it doesn’t belong, but if Baum did want some insight on that issue, he need look no further than his old pal Harry—a man trying desperately to navigate the day-to-day relations of employer-and-worker during Chicago’s industrial explosion.

[First edition of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, published by Chicago’s George M. Hill Co.]

[First edition of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, published by Chicago’s George M. Hill Co.]

In the spring of 1900, in fact, just weeks before The Wonderful Wizard of Oz debuted, Harrison Rountree was asked to testify at a Congressional hearing of the “Industrial Commission on Chicago Labor Disputes.” This came just as a large contingent of his own employees were on strike, citing unfair wages. They may had have a point, too. The average brass worker (many of them teenagers) at Turner’s plants made about $2.50 per day. PER DAY. Even in 1900 numbers, that’s brutal. Now, consider that these men were working 6 days a week, for at least 60 hours, and bringing in less than the equivalent of $20,000 in annual wages by today’s standards. The glory days of the industrial working man hadn’t arrived yet. Or else, they were a myth.

So, as a man known as an arts benefactor and an overall cheerful chap, how did Mr. Rountree balance out these incongruities in his business practices?

Well, in his lengthy testimony, Rountree inadvertently offers some historically invaluable insights not just on Turner Brass Works’ inner-workings, but on the state of factory life in Chicago and across the country at the turn of the century. Included are some rather harsh views on labor unions that wouldn’t sound out of place from some business owners in 2019; balanced out by a clear underlying desire to do right by his employees. “My connection with my men is very close,” he says at one point. “I know half of them by name.”

Highlights from the Testimony of Turner Brass President Harrison Rountree before the Industrial Commission on Chicago Labor Disputes, March, 1900.

On how Turner’s products were manufactured:

On how Turner’s products were manufactured:

“We make brass goods. We buy raw copper, tin, lead, zinc, and other materials, run our own foundry in which we do our casting, have a finishing department where the necessary machining is done on the goods, and polishing and buffing and plating perhaps, and the finished product is sold to the customers. … I think cast brass is made exactly the same as it was a thousand years ago. The brass is cast in sand from metal or wooden patterns which have first made the depressions in the sand. The metals, copper, tin, lead, etc., are mixed in a plumbago crucible, and in the molten state poured into the sand mold. But there are a few changes in that part of the castings. Machinery has entered in a little bit in some cases, and a little bit in the handling of the patterns, relieving the operator of considerable hand work.”

On Turner’s customer base:

“We spread pretty largely over the whole field that uses brass. We have lines of stuff that go to electric light companies all over the United States; they are repair parts that go to people who run electric lamps and dynamos and things of that sort. We have a line of stuff, a very small line, but it goes generally to piano people and furniture people, and the jobbing hardware trade—a little line that goes to the pump and windmill people. We have a line that goes to machinery manufacturers. We have on our list something over 2,700 customers.”

On the company’s size and value:

“We carry $75,000 fire insurance. It would be a difficult thing to say exactly what a plant, having run as long as ours, is worth. The plant would be worth perhaps not more than $75,000, if split up and disposed of piecemeal. We believe that our plant is worth about the same amount of money as our good will, as the reputation we have, having been in business a long time and being the largest concern in our special line in the United States, so far as we know. Our special line is making largely special brass work to order; not shelf goods and not shop goods, but largely to order. We were employing 150 people. We have sometimes run up as high as 200, but our facilities only allow us to work about 150, and to increase over that means running an extra shift—a night force. It is very difficult to make a night shift profitable, so we have latterly confined ourselves to a day shift.”

On worker pay:

“The hours were 10 and up, five days in the week, an average of 60 hours in the week, Saturday being a short day. The wages have run—nearly one-half our force are under 21 years of age, and the average is $10.68 for 60 hours labor. A year ago it was $10.34; two years ago at the same time it was $10.09.”

On the types of workers Turner employed:

“Men and boys. We employ no female help excepting office help. The boys are almost invariably born in this country, but frequently of foreign parents; the workmen are perhaps half and half, I should think. A good many of them are skilled. We frequently get very valuable workmen among the Swedes. I think the imported Swede is a better workman than any other; sometimes a German who has learned his trade in the old country.

“My connection with the men is very close. I know half of them by name. Many of them are individuals who came to us as errand boys and have been in the factory and learned their trade there, in one way and another, and many of them are now journeymen that were errand boys; so I know them. I take a great deal of interest in them, and we have been very fortunate in having very pleasant relations. There never has been a question. If anybody in the factory believes that he is not fairly treated in the matter of labor, in the matter of wages, he will make his request, and usually has an interview with me. I have no door to my office, and any workman can come at any time, even in his working hours, and have an interview. There never has been any question at all raised about that or hours. The men pretty thoroughly understand that if they wanted shorter hours they could have them, but only with the pay of shorter hours. There never has been, as I say, any request at all by the business agents. Having so many departments, it has been necessary to be interviewed by a number of business agents. There is a business agent for the molders—the brass molders’ union; there is another for the polishers’ union, and there is another for the finishers’ union; and in addition to them would be the business agent for the machinists. We run but few machines, but we do run a few. We have a half dozen to a dozen men who are simply tool makers and die makers or something of that kind.”

“My connection with the men is very close. I know half of them by name. Many of them are individuals who came to us as errand boys and have been in the factory and learned their trade there, in one way and another, and many of them are now journeymen that were errand boys; so I know them. I take a great deal of interest in them, and we have been very fortunate in having very pleasant relations. There never has been a question. If anybody in the factory believes that he is not fairly treated in the matter of labor, in the matter of wages, he will make his request, and usually has an interview with me. I have no door to my office, and any workman can come at any time, even in his working hours, and have an interview. There never has been any question at all raised about that or hours. The men pretty thoroughly understand that if they wanted shorter hours they could have them, but only with the pay of shorter hours. There never has been, as I say, any request at all by the business agents. Having so many departments, it has been necessary to be interviewed by a number of business agents. There is a business agent for the molders—the brass molders’ union; there is another for the polishers’ union, and there is another for the finishers’ union; and in addition to them would be the business agent for the machinists. We run but few machines, but we do run a few. We have a half dozen to a dozen men who are simply tool makers and die makers or something of that kind.”

On union labor:

“It has never been our custom to inquire of a workman whether he was a union man or not. Some of the best men we have are union men, and some of the other best men we have are not union men. It does not seem to make any difference; that is, there is no way to tell whether a man is a union man or not unless we ask him the question and he tells the truth. When the union is strong, he is very apt to tell the truth, but when the union is weak, when it is growing, or when he feels that there is a prejudice, he has a temptation to say the other thing.”

On the on-going Turner Brass Works strike of 1900 (one of many machinist strikes in Chicago at the time):

On the on-going Turner Brass Works strike of 1900 (one of many machinist strikes in Chicago at the time):

“Two weeks ago to-day, at noon, 23 men went out on a strike at the call of the business agent or walking delegate. That afternoon, perhaps, half a dozen more boys or men went out. In the morning a good many of the men did not appear. Some of them, perhaps, did not make any effort to appear at the factory and some of them were stopped on the outside of the factory and persuaded not to come in.

“At noon—it happens in our locality that there is a saloon on each side of our front door and several within a block or two, saloons and lunch places—our men go out to lunch very largely and when the men went out to lunch a good many of them did not come back. Then the next morning there were fewer men at the factory, until, on Saturday morning, out of 150, there were just 13 that worked. I interviewed the 13 individually, one by one, and asked them whether they desired to continue work or whether they preferred to lay off until the trouble had blown over. The reply was with 11 of the men that they would prefer to discontinue work until it was more comfortable, that they were in fear somewhat, and that they were certainly very uncomfortable; so we decided to close the factory. …I called the men all together at their regular time for being paid off and I talked with them. As I say, there were only 23 union men that went out. The rest of the men were persuaded—I think 121; so that would make a total of 144 altogether that day that did not work. Nearly four times as many were persuaded not to work as belonged to the union, I suppose. In the talk I had with them there was a spokesman for the strikers, and I was advised that there were 49 members of the union and not 23. This was from Tuesday until Saturday, so I believe that the union doubled in our force— doubled its membership between Tuesday and Saturday. If there has been no change since, one-third of our workmen are members of the union.”

On the union strong-arming non-union members:

“It is coercion and terror finally. It started in the cases that I know by simple persuasion, by the use of the term -‘scab:’ you are a scab; and pretty soon it got to be so that a man was threatened. In a dozen cases of ours the men told me that they were threatened that their heads would be smashed.”

Questioner: Well, right there, don’t you think it sounds a little bit ridiculous, the idea that 21 men could overawe 121 nonunion men by such methods as you speak of?—

“In a body, yes. But you must understand that 23 union men could surround 1 nonunion man and persuade him, and they then could surround another and then another; and that was the tactics followed; 6 or 8 or 10 union men were on the lookout for 1 nonunion man.”

[A Turner Brass employee, circa 1940s. No women worked at the Chicago-era plant]

[A Turner Brass employee, circa 1940s. No women worked at the Chicago-era plant]

On the life of a brass worker:

“The most of them, I think, realize that it is largely supply and demand. Brass workers are pretty thoroughly employed in Chicago, but there is no great dearth, and these men, I think, realize that the supply and the demand are about the same. We feel that $2.50 a day is a fair average compensation for such services as they can offer. We do not feel that the trade is poorly paid, because our men work 300 days in the year. The income is $750 a year [ed. That’s roughly $19,000 a year by 2016 standards]. There has been a good deal of talk in Chicago that the bricklayer had §4.00 a day. We believe the brass-worker is better paid at $2.50 than the bricklayer at $4 a day.

Our men may live as near the factory as they choose; they may save car fare; they may save time to and from work; they have comfortable surroundings during all sorts of weather; they have the convenience of going out to their lunch in the near neighborhood or bringing their lunch and eating it comfortably; they have steady work and money every Saturday without going for it. On the other hand, the bricklayer may be at work to-day in one section of the city and the next week in another section. He may have to pay 2 or even 3 car fares to go to his work or to come back. It may be necessary for him to spend an hour and a half in getting to his work, and the same in coming back. He is exposed to the elements. He is on an uncertain footing, a bad platform, and with all sorts of laborers around him. He works in a little place, and the bricklayers on each side of him are rushing the work and he must rush; he has no choice in the matter. If he chooses to work a little slower, he can not do it, because he must keep up his end—keep up his stint. With the brass workers there is usually a chance to do the other thing if they choose; not to loaf, but to change at times, to rest or work slower.

Our men may live as near the factory as they choose; they may save car fare; they may save time to and from work; they have comfortable surroundings during all sorts of weather; they have the convenience of going out to their lunch in the near neighborhood or bringing their lunch and eating it comfortably; they have steady work and money every Saturday without going for it. On the other hand, the bricklayer may be at work to-day in one section of the city and the next week in another section. He may have to pay 2 or even 3 car fares to go to his work or to come back. It may be necessary for him to spend an hour and a half in getting to his work, and the same in coming back. He is exposed to the elements. He is on an uncertain footing, a bad platform, and with all sorts of laborers around him. He works in a little place, and the bricklayers on each side of him are rushing the work and he must rush; he has no choice in the matter. If he chooses to work a little slower, he can not do it, because he must keep up his end—keep up his stint. With the brass workers there is usually a chance to do the other thing if they choose; not to loaf, but to change at times, to rest or work slower.

On Chicago as a manufacturing center:

“With the labor subject settled. I think it is the best point for our line that there is. We are near the source of production of copper, which enters so largely into our business, and Chicago is advantageously situated for shipping. This strike which we have had has set us to thinking very seriously whether it would be possible for us to more satisfactorily conduct our business outside of Chicago in a smaller place; but we are met then with the difficulty of getting skilled labor.”

*****

In retrospect, it seems like Rountree is foreshadowing the company’s eventual move to Sycamore when he mentions the possible labor advantages of relocating to a “smaller place.” He wouldn’t be involved in that eventual decision, however.

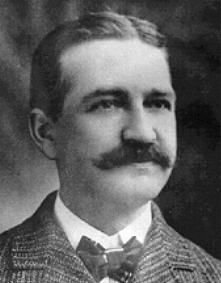

By 1904, shortly after acquiring the patents from the White MFG Co., Harrison Rountree moved on to other ventures, including handling much of the fluctuating estate of L. Frank Baum. Thomas Ferris, a longtime executive with the business, ascended to the company presidency. Shortly thereafter, Charles C. Reckitt [pictured] stepped into the role, moving much of the company’s focus more into auto parts, and moving its factory officially out of Chicago and into its new and final headquarters in Sycamore.

Of course, through it all, brass blow torches always remained part of the equation.

“All of the blow torches put out by the Turner Works are unexcelled for tool room purposes,” quotes the Manufacturing and Wholesale Industries of Chicago, 1919, “being quick in operation, convenient and economical. They are extensively used by machinists, toolmakers, and bicycle manufacturers, and in repair work, for annealing, heating tools, hardening and brazing articles that require great heating power.”

As noted, Turner’s second chapter proved even more fruitful than its first, as the Sycamore factory was a major local employer for 90 years. In the late 1920s, the ascension of John Slezak to company president helped give Turner Brass stable and forward-thinking leadership through the Depression and World War II. In 1959, the business was reincorporated as the Turner Corporation, and in the early 1980s, it was purchased by Cooper Tools, which announced the closure of the Sycamore plant in 1999.

As noted, Turner’s second chapter proved even more fruitful than its first, as the Sycamore factory was a major local employer for 90 years. In the late 1920s, the ascension of John Slezak to company president helped give Turner Brass stable and forward-thinking leadership through the Depression and World War II. In 1959, the business was reincorporated as the Turner Corporation, and in the early 1980s, it was purchased by Cooper Tools, which announced the closure of the Sycamore plant in 1999.

Despite a 120 year history of success and a sterling reputation for quality, the Turner Brass Works has faded into obscurity in the 21st century Its trademarked “Hot Blast” is now merely but another blast from the past—a potential fire hazard with a nice patina—in the Made In Chicago Museum.

[Dorothy Rountree, daughter of the Turner Brass president and possible partial-inspiration for L. Frank Baum’s character of Dorothy in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz]

[Dorothy Rountree, daughter of the Turner Brass president and possible partial-inspiration for L. Frank Baum’s character of Dorothy in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz]

Sources:

Chicago Labor Disputes of 1900, Vol. VIII of the Commission’s Reports

The Torch: Newsletter of Blow Torch Collectors Assoc., #59

Western Electrician, Vol. 35, 1904

“Great Things From Small Beginnings” – Chicago Daily Tribune, October 10, 1904

Manufacturing and Wholesale Industries of Chicago, 1919

“Sycamore Plant Sold” – DeKalb Daily Chronicle, Jan 15, 1921

L. Frank Baum: Creator of Oz, by Katharine M. Rogers

Metropolitan, Vol. 11, 1900

The Inter Ocean, December 9, 1898

Archived Reader Comments:

“Turner Brass Works also made pressure gasoline lanterns and stoves. Although most were branded as Turners, a good number of them were rebranded for Spiegel and Sears.” —Bill Sheehy, 2019

I have a Turner brazing torch with a wooden

Handle, on top of the pressure plunger it says “ Turner Brazing Torch Sycamore Ill. “

On the side of the pressure plunger it says “otto Bernz Newark N.J. “ as well as “patappldfor” does that give any indication when it was made?

Turner Brass made more than torches. I own an Arc gas light from them Chicago factory. They also made camping equipment (gas stoves, lanterns etc) out of sycamore, some were badged under their name, some under J & S auto, some under Western auto? I think.

Did Turner or White make “Old Reliable” soldering irons?

I have a Turner LP-666 propane torch. I need a operators manual with parts list and I haven’t be able to locate one. Can you help me locate a manual? Thank you.

I recently purchased a Turner brass works torch I can’t find anything about it would love to know what I have looking for anyone who might know what I got???

Just to add. Anaconda wire company was here which my grandpa ran. The aerosol spray pint was invented here along with electrical wire nuts ideal industries

Lot of history I have and need to make sure it gets put on paper

My name is Eric Mathey! I was born and raised in the the town of Sycamore. John Barris my uncle worked for turner brass as we called it and for cooper tools. I have many items that were made there, including the torches they made for the 1984 summer olympics that was lit on the east coast forgive me for where it started. But joggers ran across the United States with it lit to start the ceremony. He was one of the runners and we have it. Crazy I grew up on Rowantree rd and the original owner last name is Rountree more to come

I have a turner brass works torch I can not see any markings on it but it looks very old I would like to know more about it I can send pictures of it if wanted

What year was the solid bronze lion or solid brass lion made? I have one would anyone know the value .my mom and part of her family worked there from the 1930s.very valued employee.she was there for the Olympic games torches being made and prodyced.

Hello. I acquired a propane forge the other day that screws directly to the top of a propane tank. The only thing cast into it is LP 307 R. The tank itself say manufactured for Turner Corp Sycamore Illinois. I have not been able to find anything on the internet about it. I have no desire to use it, but would like to find out any information about it that I can. I’m hoping someone on here can point me in the right direction. Thank you.

I have a Turner Brassworks blowtorch that my Dad had when I was just a kid. I THINK it’s from the 1940’s but could be wrong. I’ve searched the internet and haven’t found one like it at all. I’ve seen several that are similar, but mine has two adjusting knobs on the back of the assembly instead of one. If I were to send you a photo, could you possibly tell me what era it came from? I’m the last of 7 children and was born in 1956. My oldest brother was born in 1940, so it has to fall somewhere between us. Thanks. You guys made an awesome blowtorch. My father and uncle both used this one to melt lead and pour sinkers for fishing.

Midway through the above article is a headline about the strike of 1900. A torch is pictured there where the burner tube is connected to the side of the tank near the top. Can you tell me more about that torch. I have one identical to it and it has Turner #2 on the burner. I can’t any reference to to that torch and would like to know more.

Shoot me a message on Facebook David Troani. Profile pic is my my dog. I’ve been collecting for quite a while now and know most of other. Big collector’s when it comes to torches. I’d like to see pics of the torch you have. If need be I’ll forward them to the collector groups. Thanks-Dave Troani