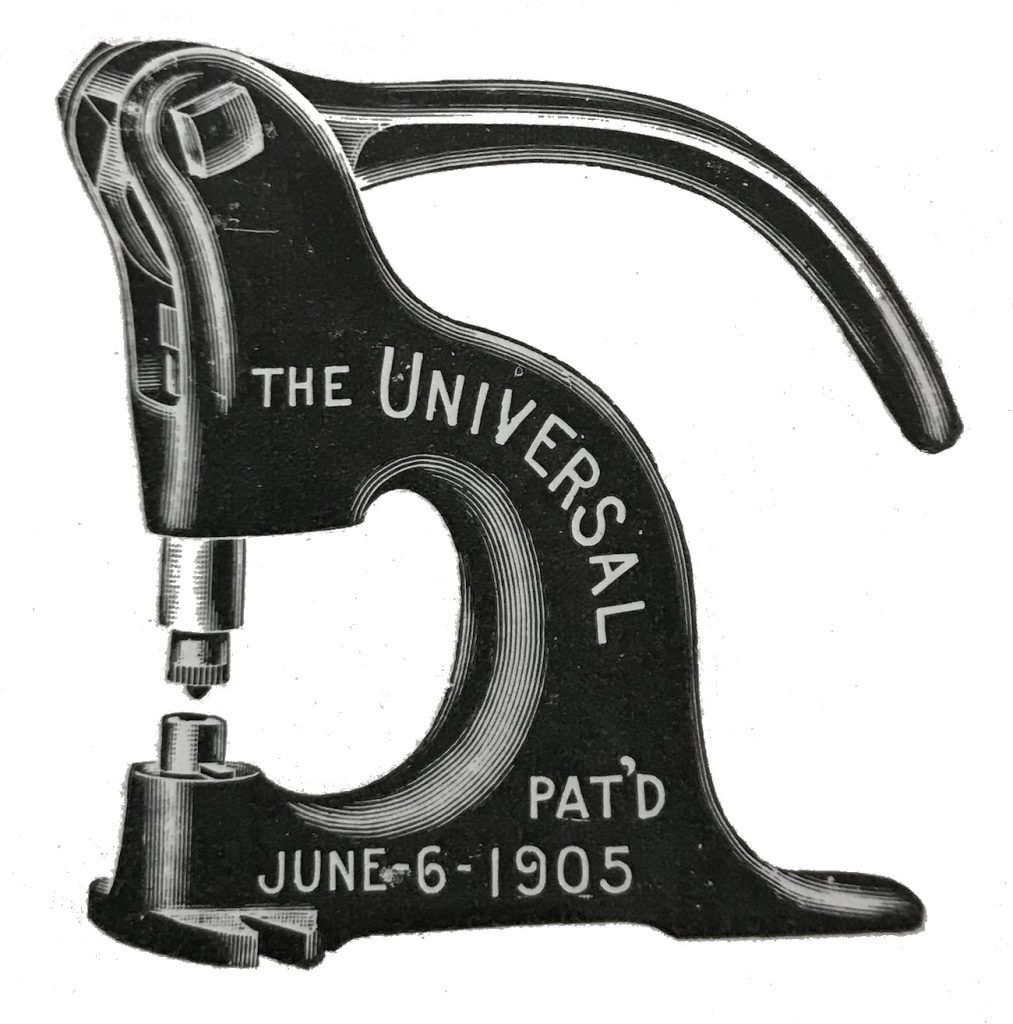

Museum Artifact: “The Universal” Cast Iron Rivet Setter, c. 1910s

Made By: F. H. Smith MFG Co., 3017-47 W. Carroll Ave, Chicago, IL [East Garfield Park]

Half a century before Rosie the Riveter turned a once tedious trade into a patriotic call-to-arms, Chicago inventor and businessman Fred Herbert Smith was already ahead of the curve, if only lacking in proto-feminist iconography.

Smith (1858-1908) grew up near Boston, Mass, and was already a seasoned mechanic and watch-maker when he made his way west to Chicago in the summer of 1892. That year, at age 34, he established the Chicago Manufacturing & Optical Company with fellow inventor / tinkerer Henry C. Pomeroy. The firm was mainly a smalltime wholesaler of optical accessories in its early years, operating out of an office at 18-30 West Randolph Street. By the turn of the century, though, Smith had steered the business into more manufacturing work, making not only vision related doo-dads, but a wide range of scientific instruments and its own line of riveting, punching, stamping, and fastening machines—mostly for smaller leather and textile work.

Smith (1858-1908) grew up near Boston, Mass, and was already a seasoned mechanic and watch-maker when he made his way west to Chicago in the summer of 1892. That year, at age 34, he established the Chicago Manufacturing & Optical Company with fellow inventor / tinkerer Henry C. Pomeroy. The firm was mainly a smalltime wholesaler of optical accessories in its early years, operating out of an office at 18-30 West Randolph Street. By the turn of the century, though, Smith had steered the business into more manufacturing work, making not only vision related doo-dads, but a wide range of scientific instruments and its own line of riveting, punching, stamping, and fastening machines—mostly for smaller leather and textile work.

In 1901, as co-founder Pomeroy turned his attention to a separate sister business (the Abbott Machine Company), Smith incorporated Chicago MFG & Optical under a new name—the F. H. Smith Manufacturing Company—and it would remain as such for the next 100 years, with several of Fred’s descendants keeping his legacy alive even after the business left the city for the burbs (first Downers Grove, then Addison, IL).

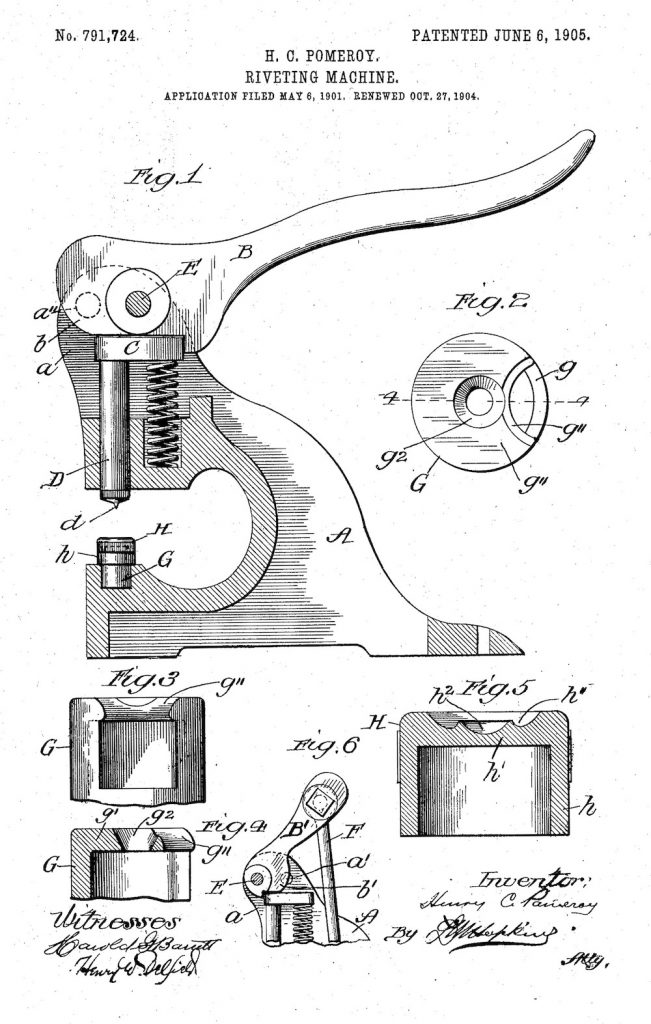

The artifact in our museum collection is, of course, a proud entry from Smith’s early Chicago years; a “Universal” riveting machine sporting a clear patent date of June 6, 1905. In some ways, the item represents the transition of the company from optical supplies to “high-grade specialties.” H. C. Pomeroy applied for the original patent shortly before leaving the firm, so by the time the U.S. Patent Office finally approved it (No. 791,724) in the summer of 1905, it retroactively fell under the banner of the F. H. Smith MFG Company. Fred Smith had invented a few similar devices in his own right, but Pomeroy’s patents are often the ones you’ll see floating around most often in antique shops, suggesting they were likely the company’s better sellers in the years prior to World War I.

[The patent drawing for our Universal Riveting Machine, developed in 1901 by Henry Pomeroy and Fred Smith, and approved in 1905]

[The patent drawing for our Universal Riveting Machine, developed in 1901 by Henry Pomeroy and Fred Smith, and approved in 1905]

Universal Appeal

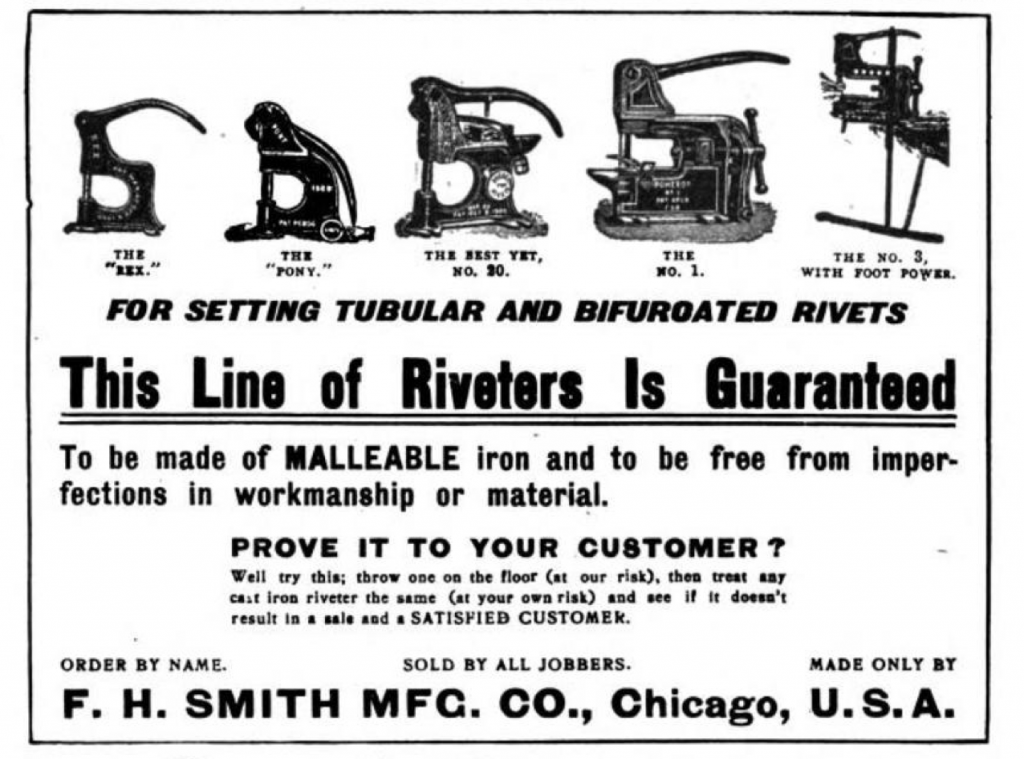

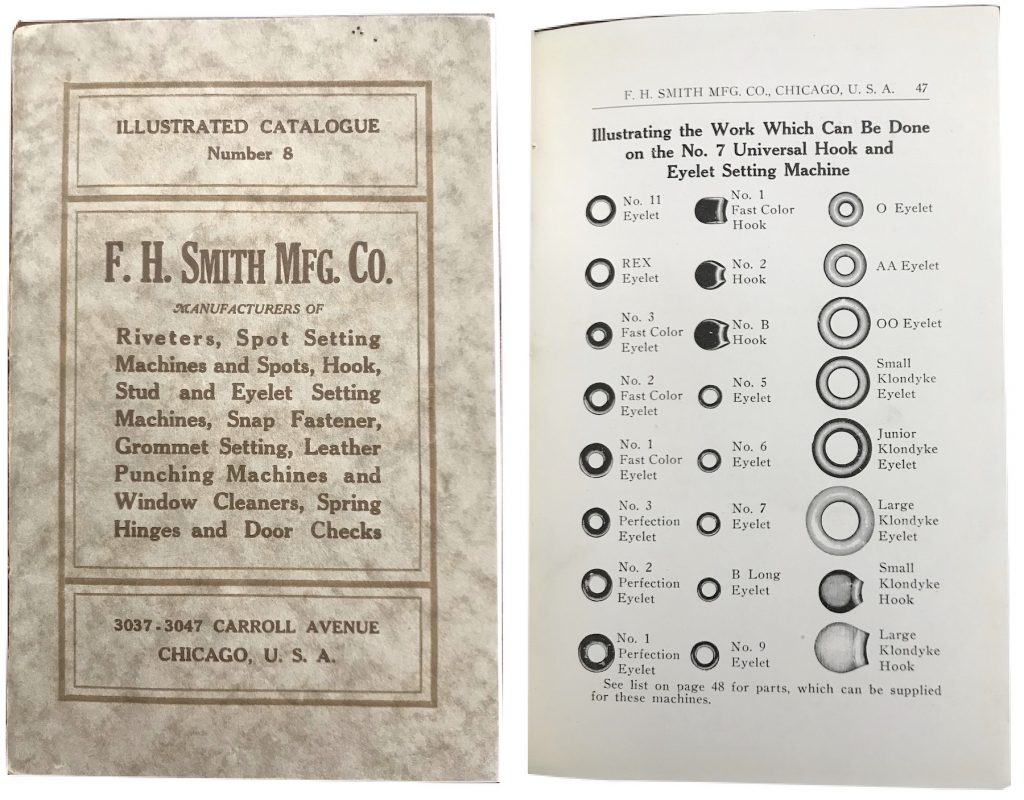

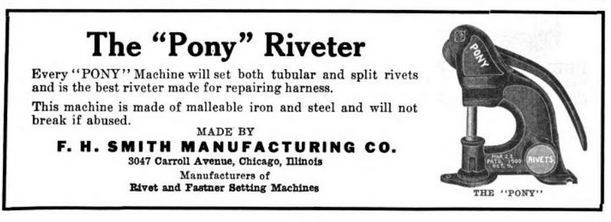

If we’re being highly technical (which we bloody well should be, I suppose), the Universal rivet setter was actually identified in a subsequent F. H. Smith catalog (circa 1915) as a “Lacing Hook, Stud and Eyelet Setting Machine,” distinguishing its intended purpose a wee bit from other very similar Smith products, such as the “Victor,” the “No. 99,” the “Pony,” and a couple alternative Universal riveters specialized for “fastener setting” and “grommet setting,” respectively.

“These machines are neatly finished in two coats of black japan with gilt letters and make an attractive store fixture,” the Smith catalog said of our Universal model.

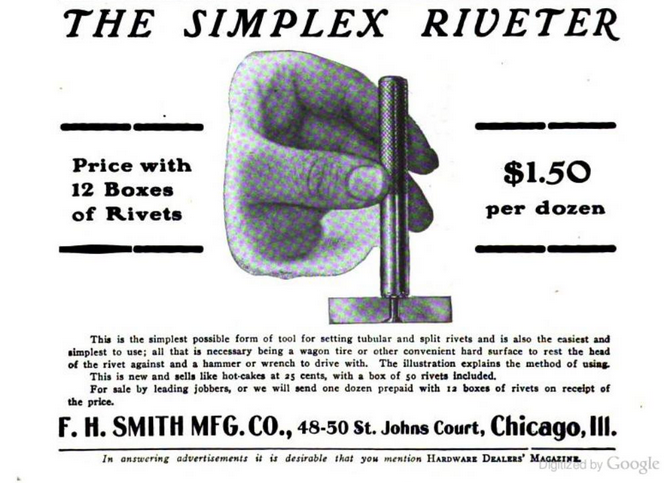

[1907 advertisement for F.H. Smith in Hardware Dealers Magazine]

[1907 advertisement for F.H. Smith in Hardware Dealers Magazine]

The key replaceable components of Smith’s early rivet setters were the “pocket ” (the lower piece that holds the hook or eyelet) and the “point” (upper piece that screws into the plunger). Different pockets and points would be needed for setting different hooks and eyelets, so you could purchase those from F. H. Smith, as well, usually for 20 or 30 cents each.

“I am aware that it is not broadly new to provide a machine with removable tools of various styles and intended for various purposes,” Henry Pomeroy wrote in his original patent application, “but, so far as I am aware, I am the first to provide a riveting machine with a permanent post adapted for setting lacing hooks and with removable caps adapted to be placed upon and supported by said post, and variously fashioned for setting other devices.”

[Cover page from F.H. Smith catalogue No. 8, and a page from inside, featuring hardware compatible with the Universal Riveter]

[Cover page from F.H. Smith catalogue No. 8, and a page from inside, featuring hardware compatible with the Universal Riveter]

Pomeroy and Smith’s turn-of-the-century innovations remained the gold standard for small leather / textile riveting right up until pneumatic hammers and rivet guns rendered them mostly obsolete, outside of traditionalist cobbler shops.

F. H. Smith & the Deadly Moose Hunt That Wasn’t

While we could go into greater detail about the ins and outs of riveting—which would be riveting, for sure—the continuing adventures of Fred H. Smith offer quite a bit more entertainment.

According to the Manufacturing & Wholesale Industries of Chicago, Smith was someone who’d “gained a secure place as one of the able and progressive captains of industry in Chicago” at the beginning of the 20th century. “Mr. Smith was a man of sterling character and admirable constructive and executive ability, his energy and progressiveness having been potent in laying a firm foundation for the business.”

If there was one event that could best encapsulate Fred Smith’s “sterling character” and his next-level loyalty to his colleagues, it absolutely has to be the crazy Moose Hunting Miracle of 1906.

During this period, Smith was sharing his West Randolph Street plant with old chum Henry Pomeroy, whose Abbott Machine Company was making its perforators and check protectors in the same complex. Fred was also doing double duty, serving as Abbott’s secretary-treasurer and making himself some new pals in the process.

During this period, Smith was sharing his West Randolph Street plant with old chum Henry Pomeroy, whose Abbott Machine Company was making its perforators and check protectors in the same complex. Fred was also doing double duty, serving as Abbott’s secretary-treasurer and making himself some new pals in the process.

In November of ’06, Smith and two of these gents—Abbott’s vice president J. S. Lincoln and a salesman named D. R. Caldwell—made plans to take an extended moose hunting trip up north to Grand Marais, Minnesota, along Lake Superior. The weather was supposed to be quite pleasant, and Fred was excited to hit the road. Unfortunately, as the papers later reported it, “at the last minute, Smith was prevented from going” on the trip—probably due to an overabundance of rivet-related responsibilities. You can likely anticipate what unfolded next.

Leaving Fred behind in Chicago, Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Caldwell went in search of moose on their own, but soon found themselves caught up in a severe Minnesota snowstorm. When the weather cleared, the men had vanished, and more than a week’s worth of search parties came up empty trying to locate them.

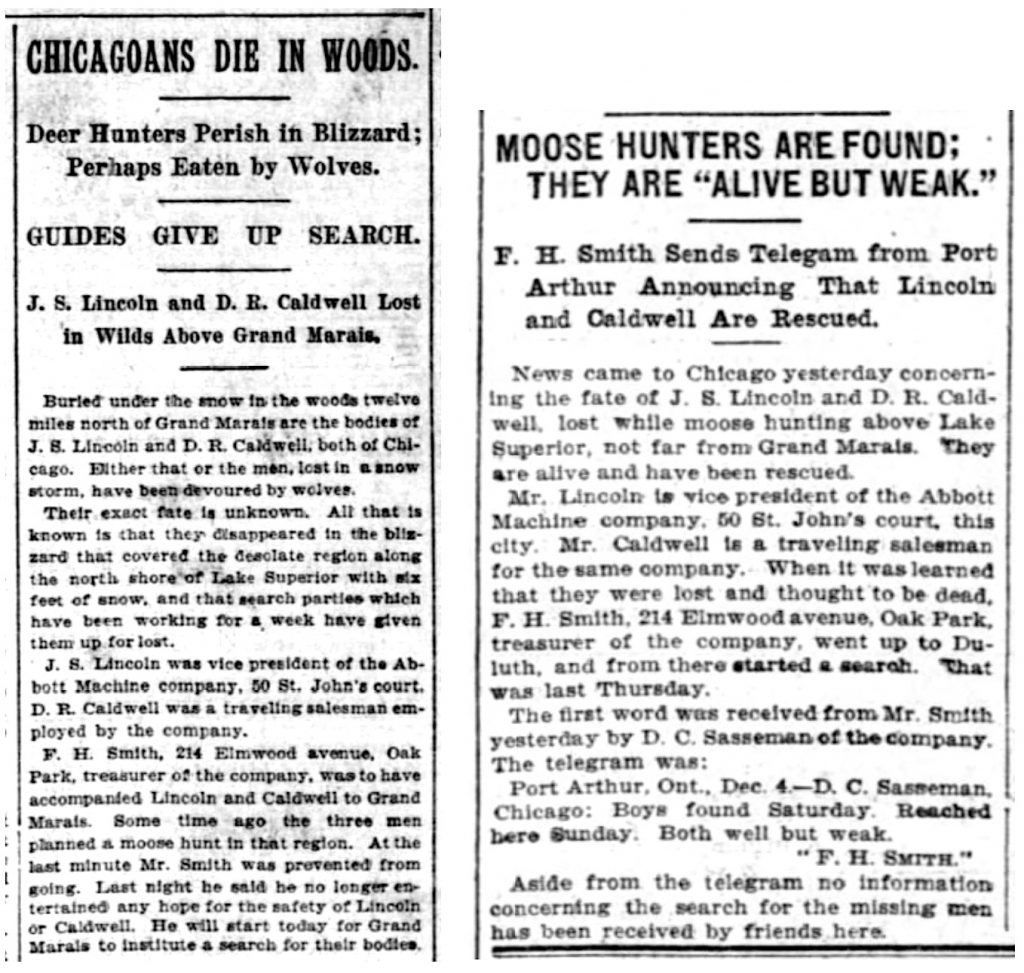

Finally, on November 28, the day before Thanksgiving, the Chicago Tribune felt justified in publishing a rather brutally presumptuous report about the fate of the two men.

“Chicagoans Die In Woods,” read the headline. “Buried under snow in the woods twelve miles north of Grand Marais are the bodies of J. S. Lincoln and D. R. Caldwell, both of Chicago. Either that or the men, lost in the snow storm, have been devoured by wolves.”

In the same article, F. H. Smith—the man whom fate had spared—acknowledged that “he no longer entertained any hope for the safety of Lincoln or Caldwell,” but that he would still “start today for Grand Marais” to institute his own personal search for their bodies. Admirable as this may have been—and befitting of a “man’s man” in the age of Teddy Roosevelt—it probably wasn’t a mission that sat well with Fred’s wife, his four kids, or his numerous business associates. As he set off for the wild country of the Great Lakes that Thanksgiving weekend, though, Smith was about to turn a twist of fate right back in on itself.

[The contrasting reports of the Moose Hunt Misadventure as printed in the Chicago Tribune on November 28, 1906 (left) and December 5, 1906 (right)]

[The contrasting reports of the Moose Hunt Misadventure as printed in the Chicago Tribune on November 28, 1906 (left) and December 5, 1906 (right)]

After a few days of unnerving silence, Fred Smith finally sent a telegram on December 4th from Port Arthur, Ontario, to the F. H. Smith MFG Co. offices in Chicago, where his vice president David C. Sasseman received it with a gasp.

“Boys found Saturday [stop]. Reached here Sunday [stop]. Both well but weak. –F. H. Smith.”

Yes, rather than being eaten by wolves, good old Caldwell and Lincoln were now “eating like wolves” in a belated Thanksgiving feast after a storybook rescue led by your riveting Mr. Smith. “They were a weak and hungry looking pair when they arrived [back in Grand Marais], I’ll tell you,” Smith recounted to the press. “Both men had lost about forty pounds of flesh as a result of their hardships.”

In keeping with his rep, Fred Smith was quick to deflect any praise for his noble efforts to find his lost friends, giving the credit instead to his crew. “Axel Berglund, our Norwegian guide and head of the searching party, simply is a wonder of the woods,” he said. “I could never say too much in praise of his ability as a guide and a woodsman. His partner, Gustav Peterson, and the three Indians who made up the searchers, also deserve great credit for their persistent work.”

In keeping with his rep, Fred Smith was quick to deflect any praise for his noble efforts to find his lost friends, giving the credit instead to his crew. “Axel Berglund, our Norwegian guide and head of the searching party, simply is a wonder of the woods,” he said. “I could never say too much in praise of his ability as a guide and a woodsman. His partner, Gustav Peterson, and the three Indians who made up the searchers, also deserve great credit for their persistent work.”

I suppose you could say Lincoln and Caldwell were the real heroes of this tale, having somehow managed to survive in waist-high snowdrifts with minimal food or clothing for two weeks. But without F. H. Smith’s insistence on tracking them down, their story likely would have gone untold, or worse yet, remembered only as a moose-related morality tale.

From Ice to Fire

It’s hard to say if Fred Smith’s own employees saw him as a heroic figure. There were occasional tensions with workers’ unions, including an attempted machinists’ strike in 1904 when Smith started requiring men to 9.5 hours per day rather than the agreed upon 9. Overall, though, F. H. seemed to be a democratic collaborator with his fellow mechanics.

After H. C. Pomeroy, company VP David C. Sasseman emerged as Smith’s new righthand man, working with him on various product designs (including a shared patent on a “knife sharpener” in 1903), while also pushing the company into new territory. This included a brief but profitable foray into “fire department equipment.”

After H. C. Pomeroy, company VP David C. Sasseman emerged as Smith’s new righthand man, working with him on various product designs (including a shared patent on a “knife sharpener” in 1903), while also pushing the company into new territory. This included a brief but profitable foray into “fire department equipment.”

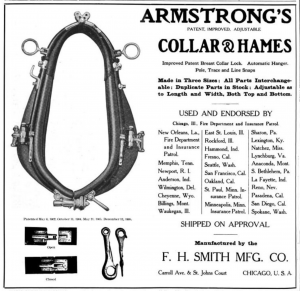

In the early 1900s, mind you, horse-drawn fire engines were still the norm, so F. H. Smith was mainly specializing in making “hames and collars” and other necessities of the equine fire brigades, most famously the popular Armstrong and Larsen brands.

“The superiority and general efficiency of the fire-department equipments manufactured by the company is best attested by the fact that these products are used by some of the largest and most important municipal fire departments, including that of Chicago.”–Manufacturing & Wholesale Industries of Chicago, 1918

Sadly, while still in the prime of his career, Fred H. Smith died unexpectedly in 1908. He was only 50 years old, and just two years removed from the Moose Miracle and the birth of his youngest son, Kenneth. With eldest son Russell G. Smith still just a teenager, as well, it fell on Sasseman to lead the company into its second decade, and the experienced engineer proved well up to the task.

Between 1908 and 1918, Sasseman doubled the value of the company, increased the workforce to more than 100 men and women (“most of which are highly skilled artisans”), relocated the manufacturing to a new plant in East Garfield Park at 3037-3047 West Carroll Avenue—”one of the handsome industrial buildings of Chicago.” F. H. Smith occupied the basement and first two floors of the building.

[The former F. H. Smith MFG Co. factory at 3037 W. Carroll Avenue, 1915 and 2018. Close-up of the doorway below.]

[The former F. H. Smith MFG Co. factory at 3037 W. Carroll Avenue, 1915 and 2018. Close-up of the doorway below.]

F. H. Smith’s granddaughter, Claire Roth, whom I was able to contact via Facebook, remembers the company occupying the Garfield Park factory when she was a child, and added this personal bit to the story:

“At the Carroll Avenue address, the top floor was occupied by Charles Frederick Stein, a piano maker,” she says. “We have one of his pianos in the family to this day.”

Another lasting artifact of that era: the F. H. Smith MFG Co. name still etched above the door at 3037 W. Carroll Avenue, despite the fact that the family moved the business to Downers Grove shortly after World War II.

Over time, several of Fred Smith’s descendants would take on leadership roles with the company. Daughter Marion Smith / Wardle (1885-1935) served as secretary in the ’20s and ’30s; son Russell G. Smith (1889-1957) was a longtime president; his younger brother Kenneth N. Smith (1906-1974) was VP; and grandson Fred H. Wardle (1916-2005) ran the business in its later years after it moved to Addison in the 1960s. Another grandson, Russell’s kid Douglas E. Smith, worked briefly for the family business, but was killed fighting the Germans in 1945, age 22.

[F. H. Smith’s former plant at 1022 National Avenue in Addison, IL, in use from the early 1960s to at least the late 1990s]

[F. H. Smith’s former plant at 1022 National Avenue in Addison, IL, in use from the early 1960s to at least the late 1990s]

No matter who was in charge, the F. H. Smith MFG Co. continued to evolve as most of its earlier marquee products moved into history’s dust bin. By the ’20s, they’d already become specialists in automatic screw machine products, and Russell G. Smith in particular became one of the original founders of the Screw Machine Products Association (alongside Walter Ware of Ware Bros. and John McDonough of Sherman-Klove, among others). By the ’50s, there was progress into more electrical appliances, including a fuse coupling for preventing electrical fires.

The Addison plant appears to have remained open into the late 1990s, but all traces of the F. H. Smith MFG Co. now appear to have vanished for good. So much so that not even Fred Smith, a Norwegian guide, and three Native American trackers are likely to bring it back alive.

Sources:

“Area Business & Industry: F. H. Smith MFG Co.” – Daily Herald, Sept 27, 1962

“A Strike of Machinists . . . ” – The Inter Ocean, Nov 30, 1904

“Hardship Endured by Lost Hunters” – Quad City Times (Davenport, IA), Dec 7, 1906

“Win Life Fight After Hope Dies” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 7, 1905

F.H. Smith MFG Co. Illustrated Catalogue No. 8, circa 1915

Manufacturing & Wholesale Industries of Chicago, Vol. 3, 1918

“Chicagoans Die in Woods” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 28, 1906

“Moose Hunters Are Found; They Are Alive But Weak” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 5, 1906

Russell G. Smith obit – Chicago Tribune, Nov 2, 1957

Kenneth N. Smith obit – Chicago Tribune, June 28, 1974

U.S. Patent 791,724A, June 6, 1905

Archived Reader Comments:

“Great post! Thank you for your research. What a ‘riveting’ tale. I bought a REX no.27 off of ebay and am in the process of restoring it for my youtube channel and your article will prove invaluable.” —Damien E., 2020

“We have a rex version model d. Very cool history, it was on my grandfather’s things looks new still has set up paper. Would like a bit more history on material and clothing made with it.  ” —Angelica, 2019

” —Angelica, 2019

“My grandfather was a shoemaker / cobbler. I have the riviter, a lot of different rivits, other cobbling tools. I have the original shoemaker nail cup “cast iron” all the nails taps plastic and metal. Shoe navel with four shoes along with shoe stretchers. Almost the whole business.” —Theresa Kohler, 2018

Can we still get replacement dyes for the riveter. Mainly the boothook setter set..

I’m looking for adapters for installing regular rivets and nipple rivets. Thank you

I am intrested in accessories for the pony,,??

Hi there this is very interesting piece. My boyfriend and I were digging thru a bag of tools and we located this piece it’s I believe a riveter from the F.H Smith MFG CO. Chicago USA. I would post a picture but there is nowhere to put it lol. Where would one sell this piece? Where can I find someone who is interested in this piece? Please let me know something

This building is now the Albany Carroll Arts Building with over 70 artists and artisans working in metal, wood, canvas, glass and murals

I sold my shoe repair equipment I had for 40 yrs. and I miss being able to set eyelets in my boots. I sold this piece with my business. I am looking for one just to use for my personal use on my boots and shoes. Is it still available?

I have one of these but it didn’t have the attachments for the rivits. Are they still available?