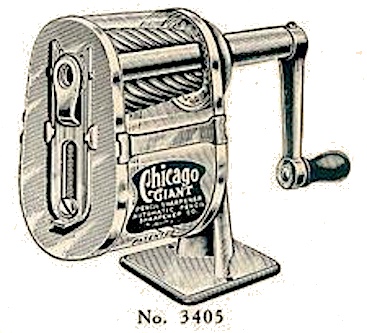

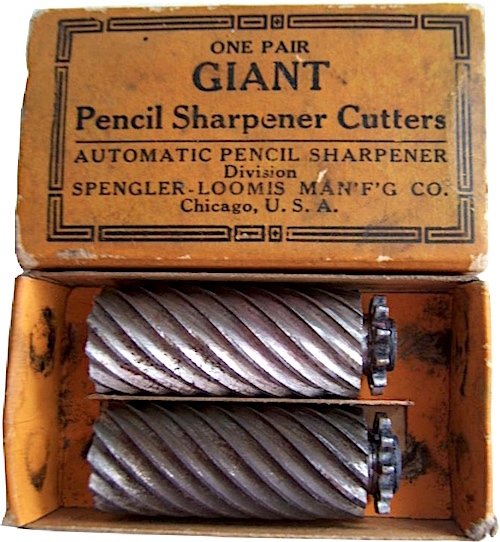

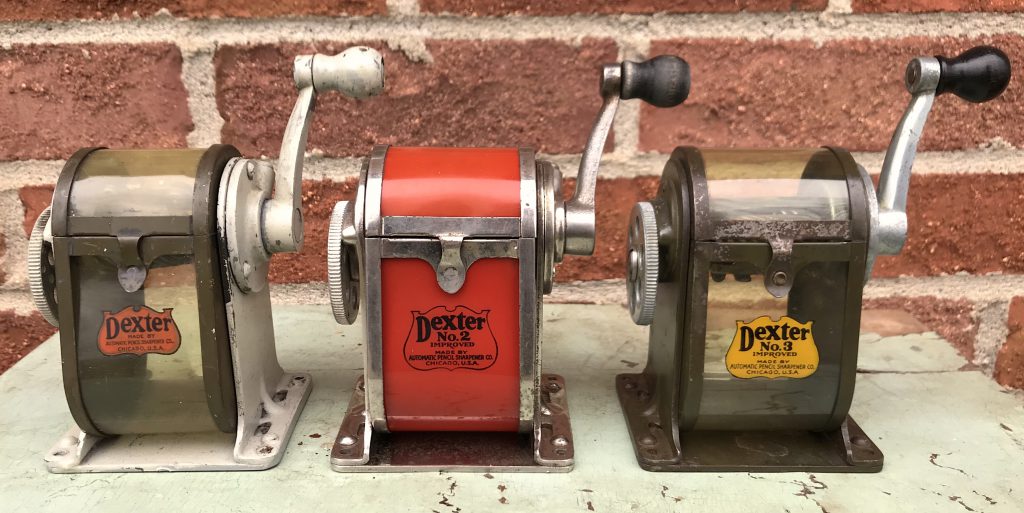

Museum Artifacts: (1) “U.S. Automatic” Pencil Sharpener, 1908; (1) “Giant,” (1) ‘Gem,” (2) “Chicago” (1920s), and (4) “Dexter” sharpeners, 1930s

Made By: Automatic Pencil Sharpener Co. / Spengler-Loomis MFG Co., 58 E. Washington St., Chicago, IL [Downtown/The Loop]. Factory: 2415 Kishwaukee Street, Rockford, IL.

For many of us, the sight of an old desk-mounted, mechanical pencil sharpener brings back some sensory-charged childhood memories—the thrilling turn of the crank, the low roar of rotating metal, the confusingly alluring scent of fresh cedar shavings.

For many of us, the sight of an old desk-mounted, mechanical pencil sharpener brings back some sensory-charged childhood memories—the thrilling turn of the crank, the low roar of rotating metal, the confusingly alluring scent of fresh cedar shavings.

Maybe you were a kid in the 1930s, or, more likely, you attended a cash-strapped public school that was still using the same classroom supplies 50 years later. Either way, the odds are good that you encountered one of these durable devices made by the Automatic Pencil Sharpener Company, aka APSCO—a brand so prominent, it was like the No. 2 Pencil of pencil sharpeners.

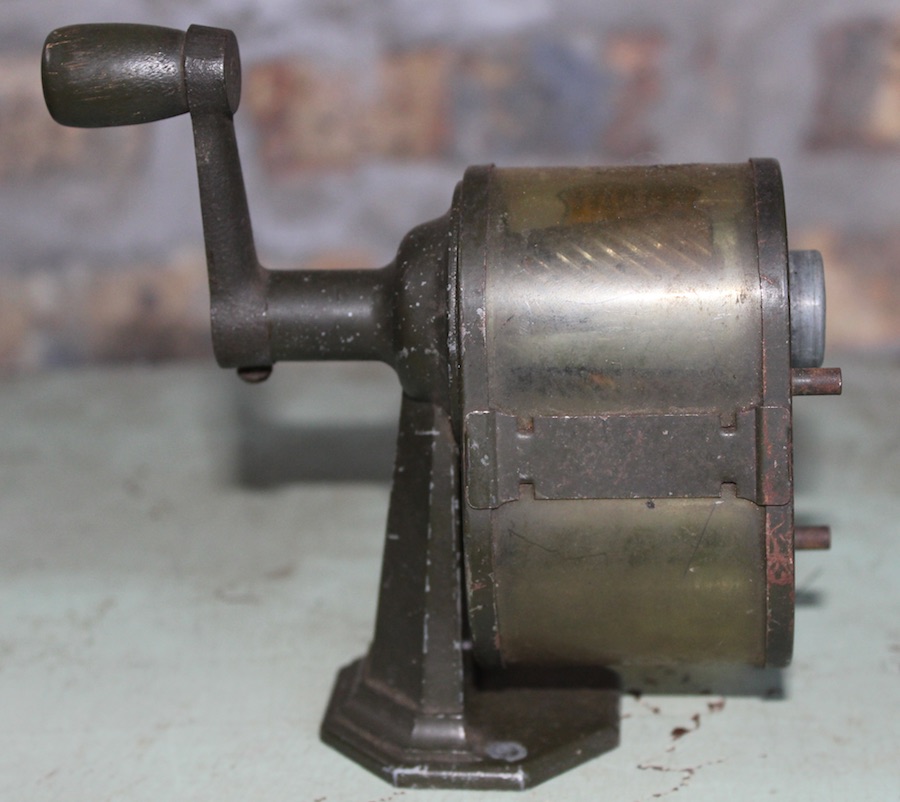

The Made In Chicago Museum currently has 9 different APSCO sharpeners in our collection, including the popular “Giant” brand featured on this page, as well as an early “U.S. Automatic, a “Gem,” a pair of iconic “Chicago” models, and a gaggle of classy looking “Dexters.” The patent date on our featured “Giant” here is 1921, lining it up with one of the more dramatic and controversial periods in APSCO’s history.

Drama? Controversy? Pencil sharpeners? But of course!

[APSCO pencil sharpeners in our collection include the original U.S. Automatic, the Giant, the Chicago, Chicago No. 2, Gem, and Dexter No 1, 2 and 3.]

The Origin Story

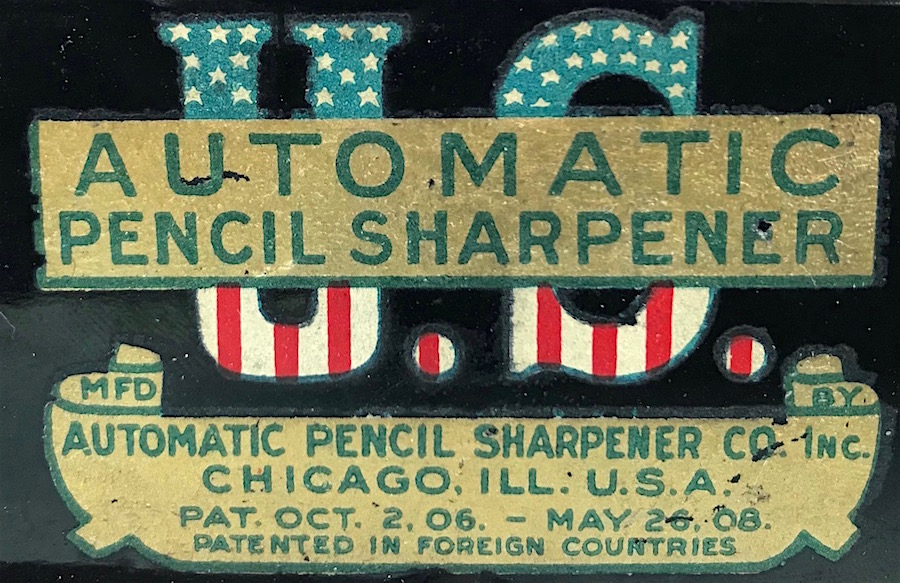

For most of its existence, the Automatic Pencil Sharpener Company was owned and operated by the Spengler-Loomis MFG Co. of Chicago, but there was a bit of an awkward courtship period beforehand. In its earliest incarnation, in fact, around 1905, APSCO’s home office was located in New York City, on Broadway, no less. Here, it promoted its first marquee product, the U.S. Automatic Pencil Sharpener—a hand-cranked, fearsome-looking beast with three rotating blades. We have one of these models in the museum collection, with a patent date of 1908, if you care to see it a bit more up close.

“It don’t grind, it cuts,” one 1905 advertisement claimed, and though not grammatically correct in any era, the message was received. The U.S. Automatic sharpener—which was actually designed and patented by the Chicago inventor Essington N. Gilfillan—became a huge seller for its New York investors. In an era when most folks were still whittling their writing sticks with a pocket knife, this was the next logical evolution.

“It don’t grind, it cuts,” one 1905 advertisement claimed, and though not grammatically correct in any era, the message was received. The U.S. Automatic sharpener—which was actually designed and patented by the Chicago inventor Essington N. Gilfillan—became a huge seller for its New York investors. In an era when most folks were still whittling their writing sticks with a pocket knife, this was the next logical evolution.

The Spengler-Loomis MFG Company wouldn’t officially buy out APSCO and move it to Chicago until 1911, but the two key players in that takeover—Charles C. Spengler and Edwin C. Loomis—were loosely involved in the business almost from the outset.

Loomis was a western sales rep for the Automatic Pencil Sharpener Co., and had been pushing its products from his Chicago office for years. Spengler, meanwhile, was the “talent,” as they say.

An experienced mechanical engineer, the Swiss-born Chuck Spengler came to the U.S. in 1884, at the age of 25, and soon launched a successful machining and repair shop with his brother George in the town of Rockford, Illinois, about 80 miles west of Chicago. He spent a lot of his free time designing random gadgets, and earned patents for many of them, including a coin-changer, a locking mechanism, several types of garment clips, and a couple innovative new breeds of mechanical pencil sharpeners.

An experienced mechanical engineer, the Swiss-born Chuck Spengler came to the U.S. in 1884, at the age of 25, and soon launched a successful machining and repair shop with his brother George in the town of Rockford, Illinois, about 80 miles west of Chicago. He spent a lot of his free time designing random gadgets, and earned patents for many of them, including a coin-changer, a locking mechanism, several types of garment clips, and a couple innovative new breeds of mechanical pencil sharpeners.

The short-lived “Spengler Brothers, Inc.” started manufacturing its new sharpeners in Rockford around the turn of the century, and—feeling assured of their mastery of the art—proceeded to buy out similar patents from other companies in the years that followed. Their efforts caught the attention of E. C. Loomis and APSCO, and a deal was soon struck, with Charles Spengler taking over leadership of the design and manufacturing of the U.S. Automatic sharpener—essentially fine-tuning Gilfillan’s original work.

In 1910, new buddies Loomis and Spengler organized their own business in Chicago—the Spengler Specialties Co.—which would soon be re-named the Spengler-Loomis Manufacturing Company. A year later, they managed to tow in their cash cow.

“E. C. Loomis, who has always been largely interested in the Automatic Pencil Sharpener Co., is now president,” the American Stationer reported in 1911. “He, together with Charles C. Spengler, of the Spengler Brothers Company of Rockford, Ill., and Mr. Elmer H. Adams, of Chicago, senior member of the legal firm of Adams, Bobb & Adams, has bought the entire interests of the former New York stockholders.

“. . . The association of Mr. Spengler with the company gives it a mechanical engineer than whom there is no better. With Mr. Spengler at the head of the mechanical department, Mr. Adams, one of Chicago’s foremost attorneys, and Mr. Loomis in charge of sales, the company will continue its position as the leading manufacturer of pencil sharpeners.”

Cranking Out the Product

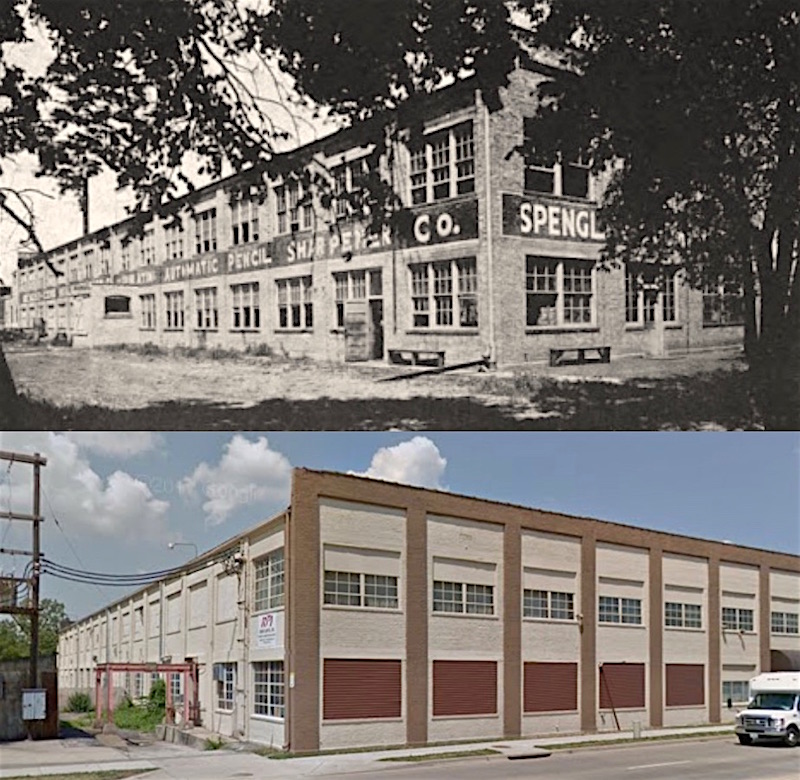

The Automatic Pencil Sharpener Company started its Chicago era at 35 E. Randolph Street, but in 1913, a new factory space was commissioned in Spengler’s adopted hometown of Rockford—where land was substantially cheaper and railroad access was still optimal. The APSCO and Spengler-Loomis corporate headquarters, meanwhile, remained in Chicago, with offices in the Garland Building on Wabash and another at 58 E. Washington Street.

The state-of-the-art Rockford factory, completed in 1914 and located at 2415 Kishwaukee Street, covered 26,000 square feet, with upwards of 150 employees soon working to produce half a million pencil sharpeners per year. It’s here where our jolly green “Giant” sharpener was born—originally designed as merely a bigger version of the flagship “Chicago” model.

[The former APSCO factory in Rockford, then and now]

[The former APSCO factory in Rockford, then and now]

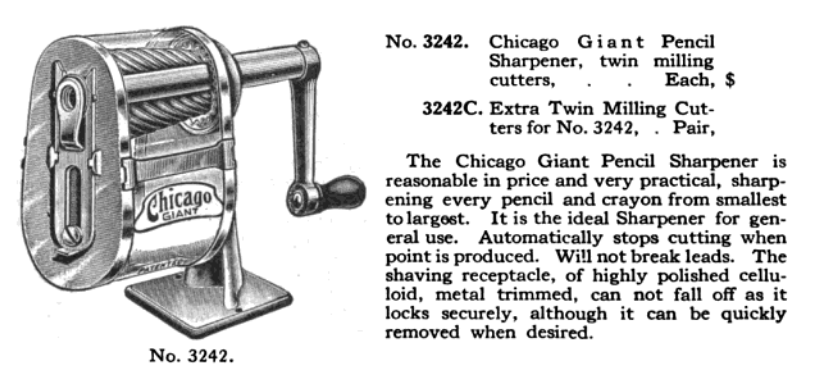

By the early 1920s, there were more than a dozen other APSCO models being produced, including the aforementioned “Gem,” as well as the “Dexter” (named for Loomis’s son), “Wizard,” “Junior,” “Dandy,” and, of course, the “Ideal-Dandy Climax”—which sounds like Jay Gatsby describing a satisfying sexual experience.

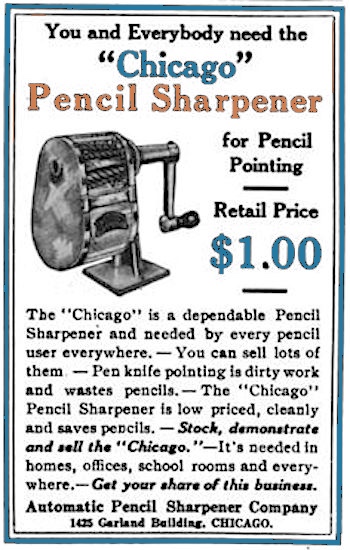

Each design had a different set of quirks and its own price point, but the strategy was always to undercut the competition. The most popular example of this was the original “Chicago” sharpener, which debuted in 1915 and was promoted as “a low priced machine of extraordinary value.” It was probably Chuck Spengler’s simplest design—using two replaceable milling cutters of tool steel and a detachable metallic or transparent chip casing—but it would influence most of the mechanical sharpeners of the next half century. To the buying public, meanwhile, the friendly $1.00 price tag was the real breakthrough.

“Placed on the market some few months ago, at what was considered a ridiculously low price ($1.00), the Chicago Pencil Sharpener sprung into instant favor . . . and has proven its worth,” hailed one 1915 review in the The Dry Goods Reporter.

“Placed on the market some few months ago, at what was considered a ridiculously low price ($1.00), the Chicago Pencil Sharpener sprung into instant favor . . . and has proven its worth,” hailed one 1915 review in the The Dry Goods Reporter.

APSCO purchased loads of advertisements in similar publications, encouraging salesman in the stationery trade to get in on this game-changing product.

“Your First Opportunity to Sell a Good Pencil Sharpener for $1.00—Do you realize what this means? Everybody everywhere a likely customer. Every home needs it. Every office cannot get along without one. . . . The time is NOW for Dry Goods and Department Stores to push the Chicago Sharpener.”

When E. C. Loomis and his sales manager R. M. Decker made a pitch, they seemed to swing for the fences (to mix baseball metaphors). “This little machine,” another ad claimed, “has silenced the oft-repeated cry of the children, ‘Daddy, sharpen my pencil!’ It has confined the butcher knife to its legitimate business, and saved the nerves and patience of parents. . . . It is as necessary as the telephone or sewing machine.”

Yes, the time had finally come for the children of America to pull themselves up by the boot straps, handle their own pencil sharpening business, and leave their fathers alone to drink irresponsibly and mumble about the suffragettes.

In my elementary school days, it was always one kid’s responsibility to dump out the class’s lone pencil sharpener receptacle at the end of each day (again, this was in the 1980s and ‘90s, not ancient times). Every once in awhile, a poor soul would spill the whole mess on the floor, revealing the frightening magnitude of fallen timber required to get us all through a few hours of division problems and notepad doodles.

There was also that frustrating phenomenon of proudly sharpening your pencil to a perfect razor sharp point, only to watch it shatter halfway through the first flamboyant gesticulation of a cursive “Q.” No machine was infallible.

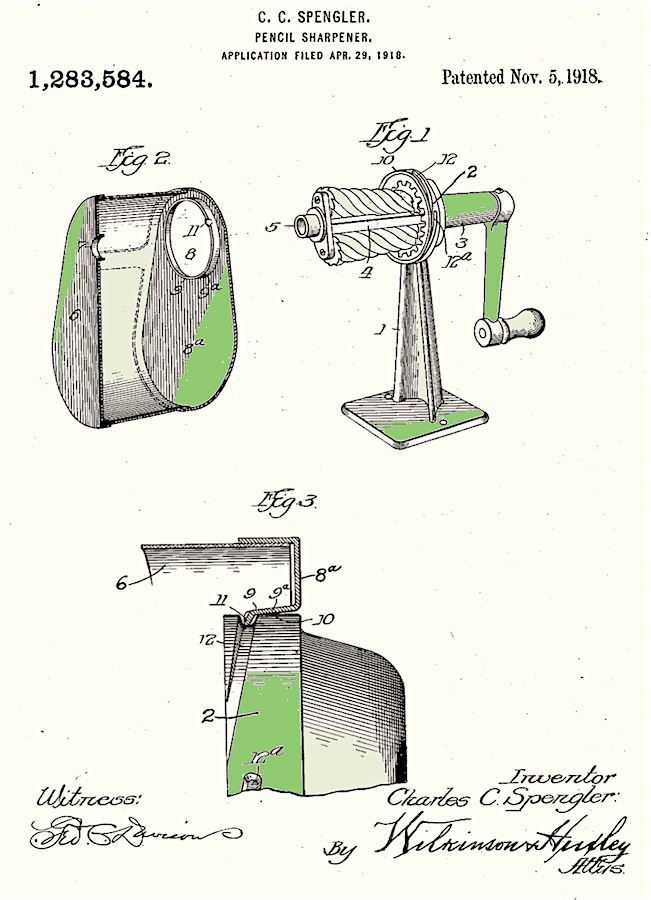

[1918 Charles Spengler patent utilized in the Chicago “Giant” sharpener design]

[1918 Charles Spengler patent utilized in the Chicago “Giant” sharpener design]

Rougher Edges

In many ways, APSCO seemed like the perfect American success story—a mechanical genius, a wiley salesman, and an affordable product lead to rising sales and legions of satisfied customers. They were the largest producer of pencil sharpeners in the world, and exported to the entire globe accordingly. But as noted in the introduction, the years surrounding the creation of our Giant sharpener were tumultuous in other respects.

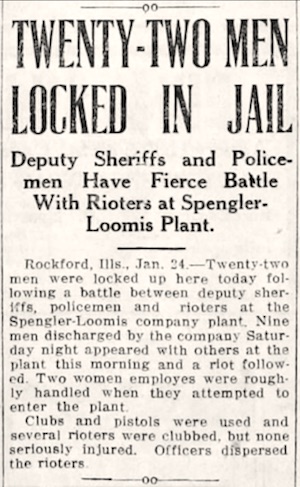

Just a couple years into the existence of Spengler-Loomis’s Rockford factory, with demand for the Chicago sharpener on the rise, the company experienced the first of many labor disputes with its growing workforce.

When a group of nine unionizing troublemakers were handed their walking papers on a cold winter’s day in 1916, things turned violent, as the men returned to the APSCO plant the next morning with some extra “friends” and some bad intentions. The ensuing riot led to twenty-two arrests and a full team of policemen taking batons to the crowd.

When a group of nine unionizing troublemakers were handed their walking papers on a cold winter’s day in 1916, things turned violent, as the men returned to the APSCO plant the next morning with some extra “friends” and some bad intentions. The ensuing riot led to twenty-two arrests and a full team of policemen taking batons to the crowd.

To make matters more complicated, World War I was underway, and much of the production at the Spengler-Loomis plant was shifting into government contract work. Along with pencil sharpeners, the plant normally manufactured trunk hardware, stamping tools, sugar dispensers, and a line of stove-top ovens, to name a few. Now they were slowed by metal rationing and increasingly paranoid about losing market share to the mounting hoards of patent thieves. There were wolves at the door.

When the real war ended, Loomis and Spengler began a legal one. They took action against competitors like the Stewart MFG Co. over subtle pencil sharpener design elements, and also went to the mat when accused of the same offenses by an elite rival like the Boston Pencil Pointer Company.

In 1920, the Boston company successfully got an injunction filed against APSCO for supposedly stealing their design of a “chip receptacle having non-transparent ends and a transparent body portion extending all the way around the receptacle.” Furious at the ruling, E.C. Loomis took out full page ads in several 1921 issues of Geyer’s Stationer and Office Appliances to debunk these claims and ease the minds of his customers within the trade.

“Before Jumping at Any Conclusions…” was the bold-faced title, and it was followed by a guarantee that “we are not infringing a pencil sharpener patent owned by anyone.

“Before Jumping at Any Conclusions…” was the bold-faced title, and it was followed by a guarantee that “we are not infringing a pencil sharpener patent owned by anyone.

“Do not allow any responsible or irresponsible representative of any manufacturer of pencil sharpeners to cause you one moment’s concern over any patent litigation,” Loomis wrote. “This is no funeral of yours. It is our party.”

Indeed, the APSCO president knew a thing or two about partying. Back in 1919, a recap of the Chicago Stationer Association’s Banquet & Ball in the pages of Geyer’s Stationer specifically describes Mr. Loomis as having “danced himself into such a state of exhaustion that he has gone to Florida for a few weeks to recuperate.” He was not an unconfident person.

And sure enough, by the autumn of 1921, Loomis was dancing again. APSCO won an appeal against the Boston Pencil Pointer Co., reversing the original decision and granting Spengler-Loomis the right to make its transparent receptacle again—which they would do on future designs like that of our Giant sharpener.

The Rockford Files

The Automatic Pencil Sharpener Company would remain an industrial pillar in Rockford for another 60 years, surviving the Depression, another world war, and the demise of the Spengler-Loomis MFG Co. some time in the 1950s. It would carry on under the ownership of Maple Industries in the 1960s and Berol Corp. (formerly the Eagle Pencil Co.) in the ‘70s and ‘80s.

APSCO Products, Inc., as it came to be known, was never able to compete in the electric pencil sharpener game quite the same way it had in the old mechanical days. The company that had defined a specific style of universally appreciated tool was now seemingly obsolete—even if many school systems hadn’t gotten the memo.

Click any of our other museum artifacts below for more:

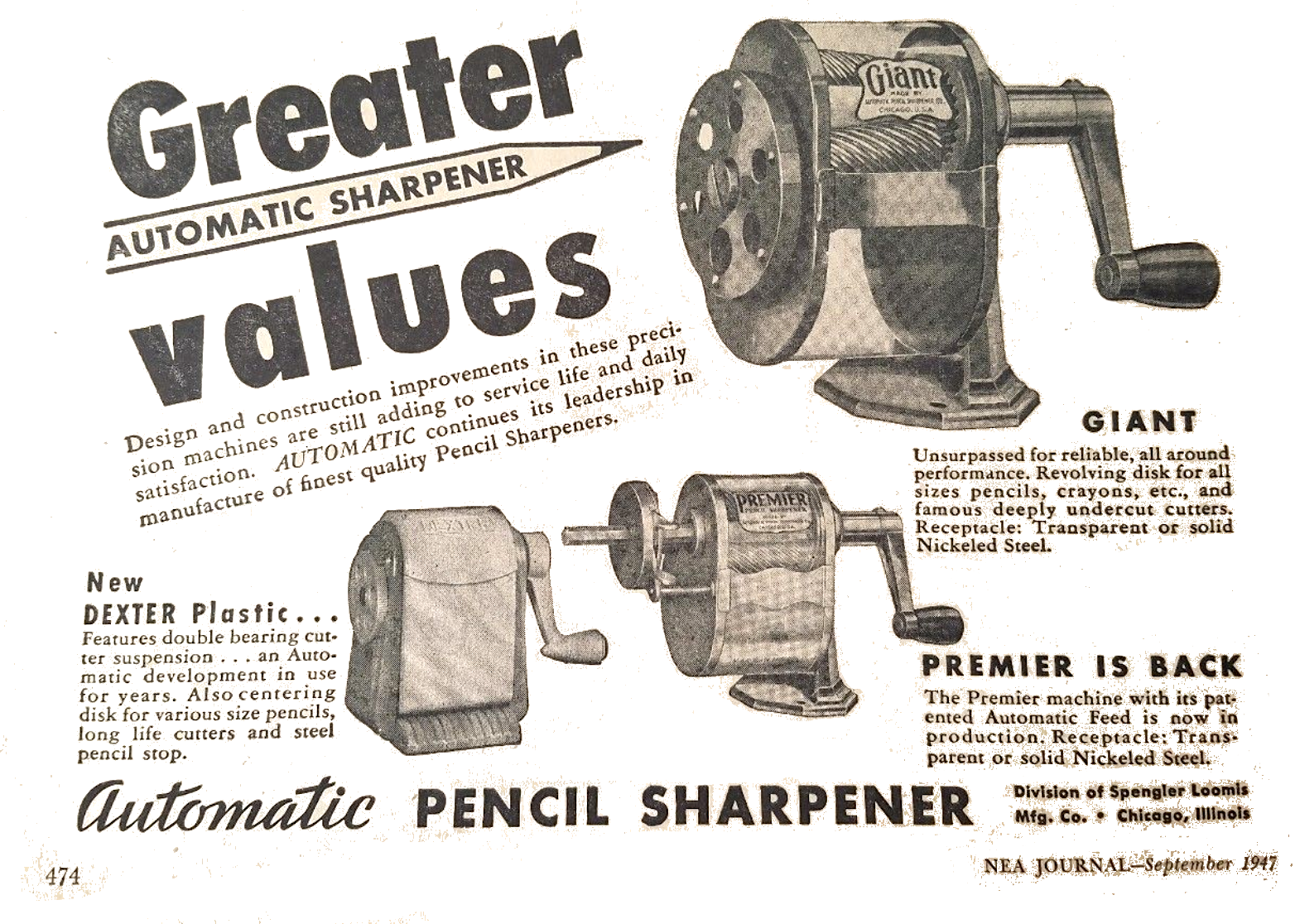

[Advertisement for the Giant from 1947, just before APSCO changed its logo and designs]

[Advertisement for the Giant from 1947, just before APSCO changed its logo and designs]

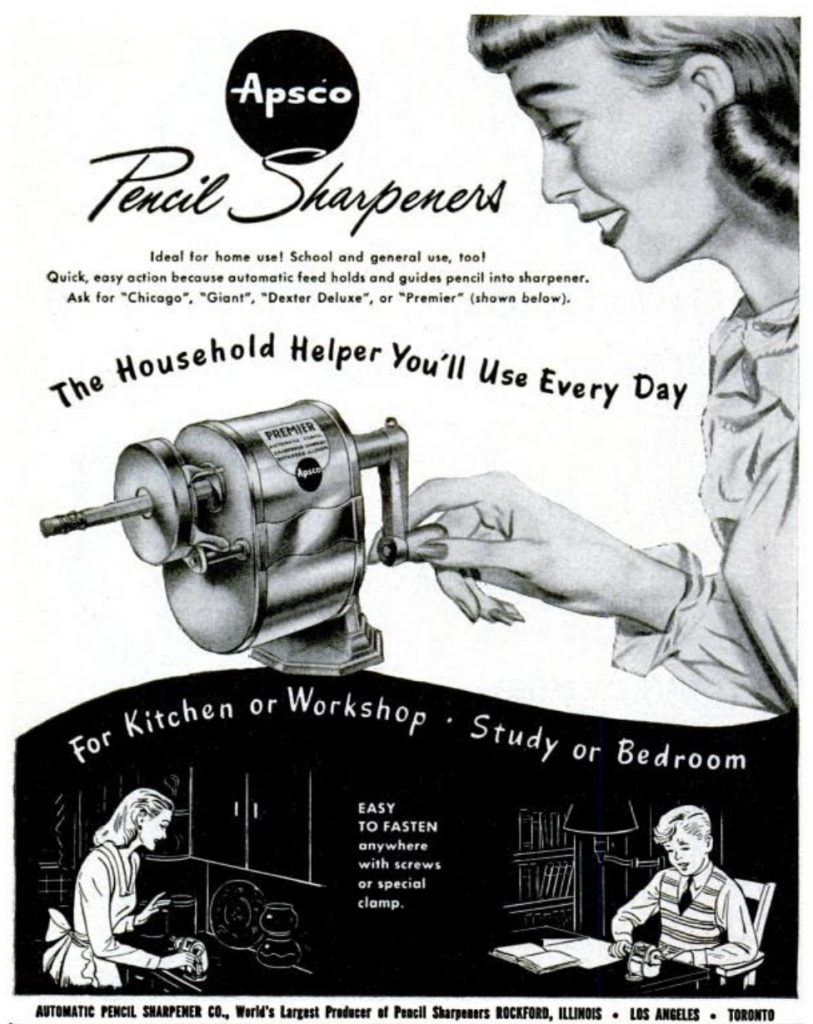

[Automatic Pencil Sharpener abandoned its longtime aesthetic for a whole new look in the late 1940s, and also adopted the “APSCO” nickname as its primary identity]

[Automatic Pencil Sharpener abandoned its longtime aesthetic for a whole new look in the late 1940s, and also adopted the “APSCO” nickname as its primary identity]

Sources:

The Rock River Valley: Its History, Tradition, Legends and Charms, Vol. II, 1926

“Pencil Sharpener” – Spengler Brothers, U.S. Patent 1,197,157 (1916)

“American Pencil Sharpener Co.” – American Stationer, Vol. 69, 1911

“The A.P.S. Company’s New Factory” – American Stationer, Vol. 76, 1914

“Concerning the Pencil Sharpener Litigation” – American Stationer & Office Outfitter, Vol. 90, 1922

Historic Encyclopedia of Illinois & History of Winnebago County, Vol. II, 1916

Archived Reader Comments:

“I just bought an APSCO Giant at a Goodwill for $2. It is a remarkable piece of engineering, typical of American manufacturing as it once was, flawed by the misperception that if you built something to last forever, you’d also be building a brand that would last forever. “Planned Obsolescence,” however effective it may be, was the polar opposite of APSCO’s company spirit. I screwed this worn-but-functionally-perfect relic onto the wall and it chewed a geometrically perfect point onto a couple of my drawing pencils. It even seems to self-lubricate with powdered graphite! I wish we still built things to last forever. It was an admirable company philosophy, even if it proved fatal. Thanks for this highly-satisfying Google search result!” —Alan Erickson, 2018

I have just purchased a MIB

“Bridge” pencils sharpener.

It is mint condition, green; great box with symbols of the suits.

Has the original clamp also.

What can you tell me about it?

Regards

We have the 1905 version in our collection of things.

HI Is The Dexter Draftsman Pencil Sharper, For Drafting pencils Only ? Thanks

I’ve been searching for a month now, and sadly CANNOT find a manually operated, US made pencil sharpener. I DO have a small 1″ x 1″ “hand-held, hand-operated, manual mode hard plastic frame” that holds two tiny little razor blades. It’s a “two-holer.” One large & one small small opening for various sized pencils. This “device” alleges to be a pencil sharpener, but it is NOT.

I have one of these sharpeners from my father. I have pics of it. Have had it for years. Still works fine. What is its value?

I have an APSCO CHicago model with the transparent receptacle (cracked in one location). The most recent patent date is Sept. 13, 1921. I know exactly where it was used and by whom. Anything special about this apsco, or is it quite generic?

I have a Apscomatic Model ES-1 electric pencil sharpener. I’m trying to get information about it ans can’t find much of anything on the internet. Can you provide me with some info and the value of this pencil sharpener?

I have the same model and I can’t find anything either. I’d really just like to refurbish it and replace the blades on the inside. Did you find any info?

My “Giant” is from the 1930’s,works fine.

Bought a house, and found a pencil sharpener left behind. It’s made of steel and cast iron base. It has a Chicago and Apsco logo on case. Not sure how old but it appears to be made in the late 60s early 70s. How can I forward a photo of it for an assessment, thanks and God bless. Joe

I just purchased a Berol Chicago Apsco pencil sharpener.I cannot find a date on the sharpener and I have only found one number on the box. I don’t believe the number is a model number it’s a restocking number. Could anyone help me out for an approximate age on it? Thank you.

I decided–a few years ago–to get one of the sharpeners that I remembered from 1st grade–off of eBay. I am now the proud owner of a Dexter Super 10…

But I was wondering if anybody knows the era of these machines. I remembered two different models–that were in every classroom in my elementary school. The Super 10 was one, and the other looked like a 60s/70s brown plastic version of what is seen above–in the Chicago.

Are there any other references for identifying these models?

And my Super 10 is still working great! The cutter assembly appears that it will happily sharpen pencils for another 50 years!

I am considering buying the APSCO “Midget.” It is yellow in color with the clear container which I love. I was wondering if anyone knew any history on this piece? When it was built? Why they decided to go with a smaller version?

I have one of these sharpeners with 5 cutting blades. I have pics of it. Have had it for years. Still works fine. What is its value?

Just found a No.4 B.D. clip in my great grandmother’s desk from th 1930’s. I was surprised to see the co. Is still around.

It was the Number 4 B.D. clip that led me to this website. I’ve been using one or two of them for decades. It was among the office items I inherited from my mother.

There are actually different models for the U.S. Automatic Pencil Sharpener. The one you have pictured is from Chicago, Illinois and is from 1911 and has slight variations from the 1907 model which is from Crosby Street, New York(written on the label). The older model has a shorter neck stem and the newer model has a longer neck stem usually with 3 metal prongs(shown in picture) attached that helps support the pencil better when in use. The color of the label for the new model is more of a baby blue and brighter red, but the older model has a darker shade of blue and red for it’s label. Even the blades have different variations as well. The older blades has just the two holes and is a bit wider height-wise and have more of a curve than the new blades. The new blades have 3 holes and is flatten down more with the heels of the blades shaven down. If you compare them side by side you can see difference but barely. Also, you can use the old blades with the newer model and vice versa. Anyways I really appreciate you making this article and like they say “They don’t make them like they used to..”

I just restored a Chicago sharpener that my dad had sitting in the garage for as long as I can remember… Thanks to your website I now know the history behind it.

Thank You,

Alex

Very informative piece of our history, thank you! I am trying to figure out the timelines of these sharpeners. I have a collection and still cannot find info with correct chronology. For example, you show a Dexter (no 1) with 6 hole sizes. I believe the no 1 had a single hole. Also the one shown is painted beige. I have a rusty beige but also a plated version. I have two Ideal models, one is a 1906 (clear) and another 1919 that is green. The Dexter Draftsman, Ideal, and no 1 all measure 2.0″ wide at shavings frame. All others are 2 3/16″ which leads me to believe they were produced later. It is nearly impossible to find any information. Your help would be much appreciated. I can send pictures of my collection if that would help.