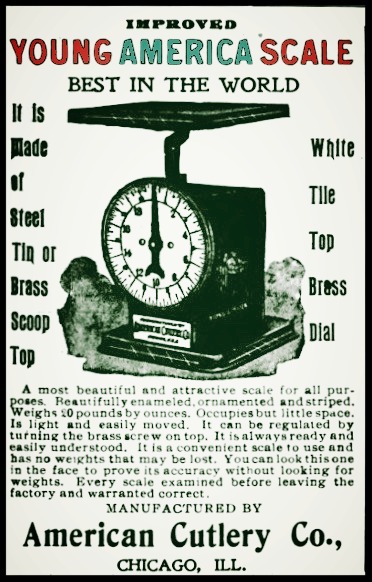

Museum Artifact: Kitchen Scale, c. 1900s

Made by: American Cutlery Co., 732-764 Mather St. (W Lexington St.), Chicago, IL [University Village]

If it seems like this turn-of-the-century kitchen scale reveals just a little bit more grace and attention-to-detail than the other dozen or so scales in our museum collection, consider it a lasting testament to the high standards of the American Cutlery Company.

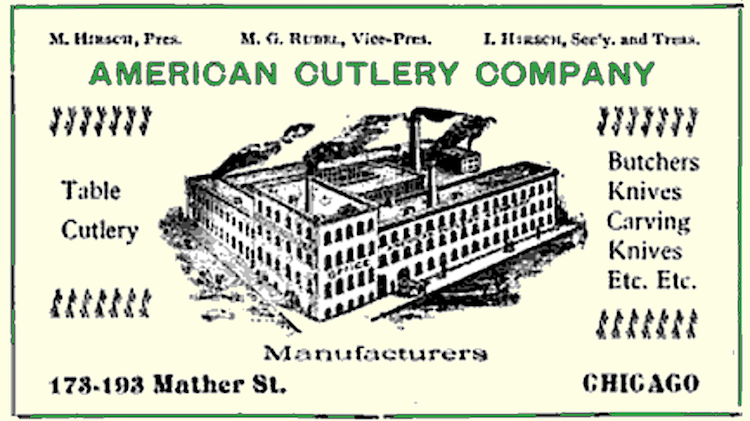

As the name suggests, weights and measures were not the original focus of this long lost Chicago institution. Way back in 1865, a pair of Jewish immigrants from Germany—Meyer Hirsch and his brother-in-law Moses Rubel—quit their jobs as Chicago cattle dealers (a reasonable urban profession at the time) to pursue a shared interest in the art of Bavarian cutlery. With the Civil War ending, many survivors from the East were flocking to the trade capitals of the West, and Hirsch and Rubel—even as marginalized outsiders—saw a uniquely wide-open opportunity to start forging steel for an exploding marketplace.

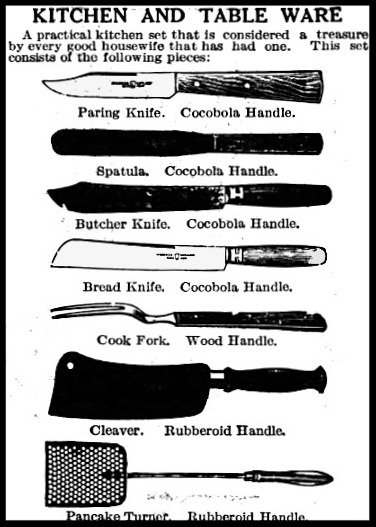

There were a few early incarnations of the business (Simon, Hirsch & Co. in the 1860s, Chicago Cutlery Co. in the 1870s) before it was organized as the American Cutlery Company around 1878, with Meyer Hirsch [pictured] as president and Moses Rubel as secretary. A West Loop factory was established on Mather Street, between Desplaines St. and Halsted, and ACCo would keep its foothold there for decades, surviving a series of calamities to emerge as one of the country’s leading suppliers of steel dinner knives, bread knives, carving knives, paring knives, butcher knives, pocket knives, and some truly top notch trench knives. I would say “knives” a few more times, but I think the page is now sufficiently optimized for that keyword.

American Cutlery goods were all “made of the highest grade of Crucible Steel,” according to a 1905 advertisement for one of the company’s distributors. “All of the blades are hand forged and evenly tempered by the latest improved process.” They represented “the very best quality and workmanship the American Cutlery Co. knows how to turn out. The size, shape and handiness of these can not be improved, and even the handles are made to last a great many years.”

Factory Life

The high esteem and reputation of American Cutlery’s products was a reflection of its growing workforce. In typical German fashion, however, achieving perfection required running a very tight ship.

According to the 1988 book German Workers in Chicago, the Mather St. factory was on the cutting edge of modern industrial efficiency in the late 1800s:

“Operating with steam power, the firm was one of the larger plants in this branch of metal work, employing over ninety men, eight women, and twenty-seven children in 1880.”

Both skilled and unskilled workers were organized into regiments, overseen by foremen, and brutally kept on task every minute of the day. Hirsch and Rubel even instituted a list of 12 behavioral guidelines for their workers, with the violation of any one of them potentially resulting in termination.

Regulations for All Workers at the American Cutlery Company, 1880

Regulations for All Workers at the American Cutlery Company, 1880

1. All workers must be ready to start work when the whistle blows in the morning and after lunch.

2. No one may stop work before the whistle blows.

3. Any worker found bringing intoxicating beverages into the factory will be dismissed immediately.

4. Smoking, swearing, and disorderly behavior are absolutely forbidden.

5. Visitors will not be be admitted without a pass from the office.

6. Speaking or walking around in the factory is forbidden, unless required by the job or, in specific cases, absolutely necessary.

7. If a worker wants to leave the job for a while, he should apply to his foreman in the form of a letter and turn the letter in to the office.

8. Each worker must see to the maintenance of the tools he uses and keep them in their proper place.

9. Our workers will be paid each Monday for the previous week.

10. If tools are damaged through negligence, their value will be deducted from the wages of the worker who broke them or let them be broken.

11. If a worker wants to stop working for the Company, he must give a week’s notice or lose the security deposit he was required to make.

12. Each worker must deposit a week’s wages with the Company as security in case he violates Paragraph 8, 10, or 11.

Some of those rules are logical, but many are emblematic of a time period in which “worker’s rights” were respected on about the same level as those of women and African-Americans (both of whom were also part of this workforce).

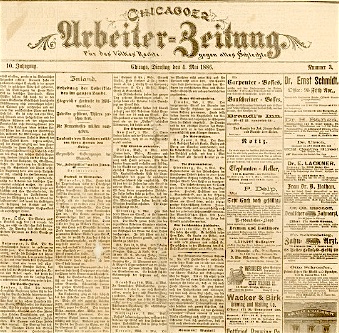

In response, Chicago’s radical German language newspaper, the Chicagoer Arbeiter-Zeitung, published an article in 1881 called “A Word of Warning to the German Unions,” in which the writer referred to American Cutlery’s regulations as an illustration of “how absolutely necessary close union organization has become in Chicago.

In response, Chicago’s radical German language newspaper, the Chicagoer Arbeiter-Zeitung, published an article in 1881 called “A Word of Warning to the German Unions,” in which the writer referred to American Cutlery’s regulations as an illustration of “how absolutely necessary close union organization has become in Chicago.

“Only the lethargy of the workers could have emboldened the exploiters to go as far as to forbid the factory workers to speak, smoke, drink, swear, and various other things which are absolutely none of their business; the exploiter can only demand the stipulated amount of work. What, then, is the difference between the freedom of the ‘free’ worker in the factory and the convict in prison?”

By the turn of the century, American Cutlery’s workforce had grown to over 500, but the strength of the unions had grown along with it. Labor disputes and negotiations of factory policy—as in most Chicago plants of the era—would become a constant issue throughout the company’s history.

Where There’s Smoke. . .

At the risk of going with a lazy cliché, the American Cutlery Company was—much like its fine utensils—forged in fire. This included not only heated labor battles, but literal infernos.

Starting with the Great Chicago Fire just six years into the company’s existence, the vulnerable Mather Street manufacturing plant would become a bit of a hot spot (another bad pun) for blazes in the decades ahead. Such were the consequences of melting tons of metal in close quarters.

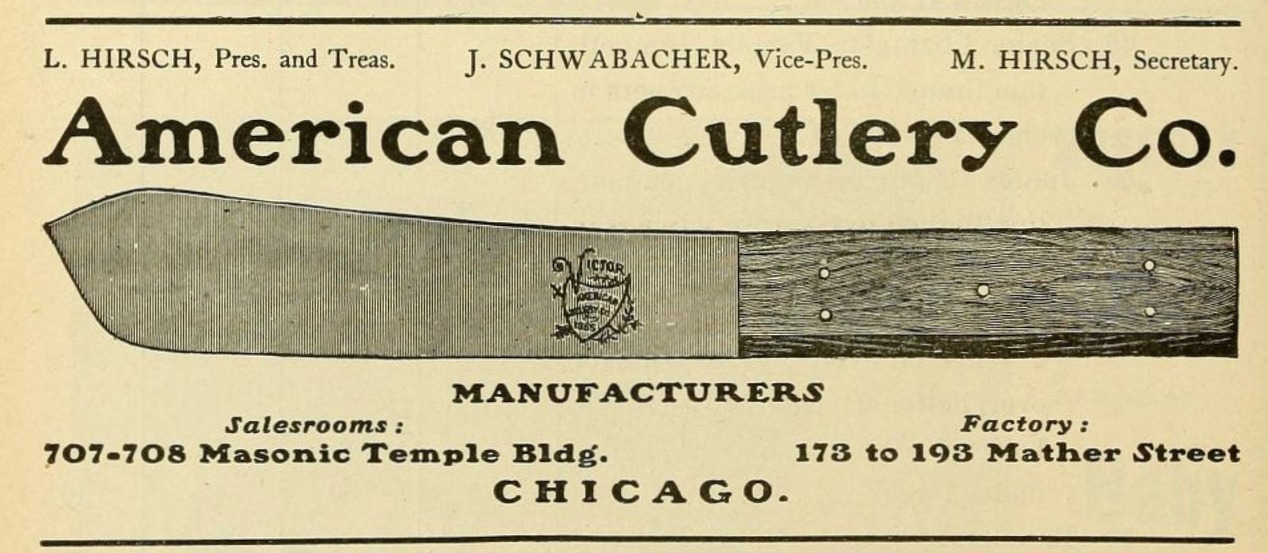

[1904 advertisement for the American Cutlery Co.]

[1904 advertisement for the American Cutlery Co.]

“Twelve hundred dozen knives and forks are made [at the American Cutlery factory] per day,” according to an 1891 article in Chicago and Its Resources, “and two 300 horse-power engines and boilers are required to furnish power. The establishment has twice been burned out, and phoenix-like has arisen from the ashes greater than ever.”

More phoenixing would be required in August of 1898, after a 17 year-old employee, John Wolf, accidentally ignited his clothes while lighting a gas furnace. Fortunately, an employee named Michael Schwartz saved Wolf’s life by wrapping his coat around him and tapping out the flames. The damage to the building, however, totaled $75,000, which is something like a few million dollars by today’s standards.

Eight years later, in 1906, American Cutlery had moved its corporate offices to the seventh floor of the Masonic Temple Building, but the newly expanded, six-story Mather Street factory was still its production center. To the surprise of no one, it caught fire again, this time from an unknown mishap in the grinding room. Dozens of Chicago firefighters rushed in to keep the flames contained, but the damage was even more costly than before, with a price tag topping $400,000 (more than $10 million after inflation).

Eight years later, in 1906, American Cutlery had moved its corporate offices to the seventh floor of the Masonic Temple Building, but the newly expanded, six-story Mather Street factory was still its production center. To the surprise of no one, it caught fire again, this time from an unknown mishap in the grinding room. Dozens of Chicago firefighters rushed in to keep the flames contained, but the damage was even more costly than before, with a price tag topping $400,000 (more than $10 million after inflation).

By this point, it was Isaac Hirsch, son of the company founder Meyer Hirsch, who was sitting in the president’s chair. He talked to the Chicago Tribune in the aftermath of the fire:

“We had the best equipped plant in America, and everything is a loss,” Hirsch said, taking stock of his 112,000 sq. ft. factory. “Our warehouse was filled with goods which were to have been shipped within the next week. The burned buildings will be replaced by new ones as soon as possible.”

And indeed, the American Cutlery Company phoenixed its way back yet again.

“Always In the Weigh”

In the early years of the 20th century, the second generation of American Cutlery—led by Isaac Hirsch and his brothers Moses (vice president) and Henry (secretary)—began strategically expanding the company’s range of products. With knife sales slowing as cheaper, foreign imports entered the market, additional forms of revenue would be needed to remain competitive.

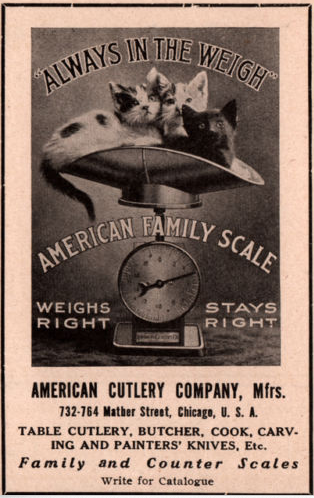

And so began the manufacturing of the “American Family Scale,” an instant competitor with Chicago’s other noted kitchen scale producers, including Triner, Hanson, and Pelouze.

And so began the manufacturing of the “American Family Scale,” an instant competitor with Chicago’s other noted kitchen scale producers, including Triner, Hanson, and Pelouze.

The latter firm, a long since established giant of the weights and measures, took particular umbrage at American Cutlery’s unwelcome entrance into their field. In 1900, the Pelouze Scale & MFG Co. challenged that the American Family Scale was, in fact, infringing on one of Pelouze’s own patents—an 1896 design by E. N. Gilfillan, No. 25,327. It was a defining early moment in the Hirsch Brothers’ big push into the scale business, and it ended with a resounding victory.

In fact, it was the federal judge Peter Grosscup—better for known using a judicial injunction against workers during the Pullman Strike a few years earlier—who delivered the opinion of the court in American Cutlery’s favor. His wordy “definition of design” would be referenced in court cases for decades to come.

“The essence of a design resides not in the elements individually,” Grosscup said, “nor in their method of arrangement, but in the tout ensemble—in that indefinable whole that awakens some sensation in the observer’s mind. . . . Whatever the impression, there is attached, to the object observed, a sense of uniqueness and character.”

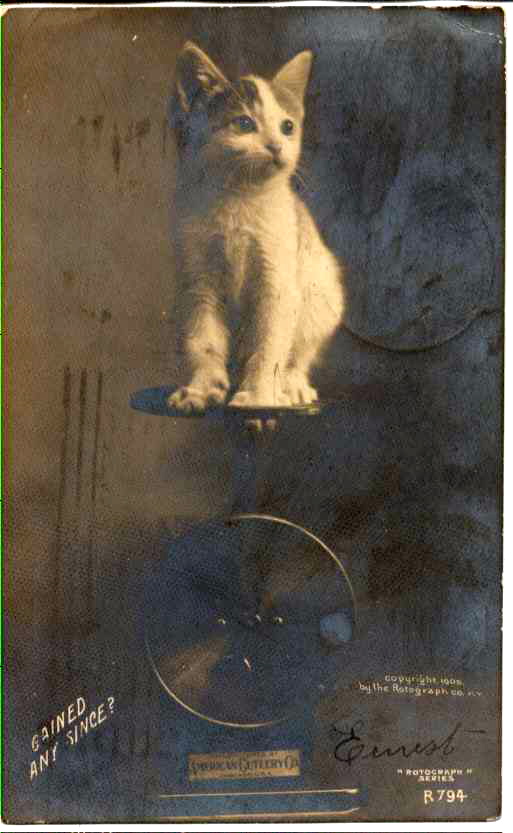

He was right, American Family Scales did have a distinct character all their own. They were made from quality steel just like the company’s cutlery, and were precision-reliable in terms of measurements (of kittens, at least). The brand would become so popular, in fact, that it would eventually spin-off into its own entity—the American Family Scale Company—with Moses Hirsch as its president.

The Final Cuts

Even as the scale business picked up, however, things weren’t improving in the old knife department. After one of the later rebuilds of the Mather Street factory, sales of the flagship product continued in a downward direction. In 1912, Moses Hirsch sent a letter to all dealers of American Cutlery products, warning of imminent price increases. He cited “the continual advance in the cost of materials and higher wages for labor,” and also suggested that the kitchen scale business was proving costlier, too, due to “many recent requirements of the various State Commissioners of Weights & Measures.”

Fortunately—kind of—World War I began shortly thereafter, effectively shutting down German import competition and getting American Cutlery back on track for a while. In 1920, the company was reorganized with Moses Hirsch elevated to president and treasurer and Henry Hirsch to VP. Isaac Hirsch was nearing retirement and took a secondary role, but there was young blood in the form of new company secretary Lawrence H. Powell; nephew of the Hirsch brothers and son of Meyer’s eldest daughter Bertha Hirsch Powell.

Fortunately—kind of—World War I began shortly thereafter, effectively shutting down German import competition and getting American Cutlery back on track for a while. In 1920, the company was reorganized with Moses Hirsch elevated to president and treasurer and Henry Hirsch to VP. Isaac Hirsch was nearing retirement and took a secondary role, but there was young blood in the form of new company secretary Lawrence H. Powell; nephew of the Hirsch brothers and son of Meyer’s eldest daughter Bertha Hirsch Powell.

That same year, an article in the American Cutler magazine (no relation) noted that the American Cutlery Company “has had a steady normal growth from a small beginning until it now claims to be the second largest cutlery manufacturing company in the United States, and their product is known all over the world.

“The company enjoys a large trade with the hardware jobbers in the United States and Canada as well as lines of hardware specialties, household and beam scales. Their export business is reaching out and they are now represented through sales agents in almost all countries of the globe.

“The management of the new organization anticipate a steady growth and expect to enjoy an increased prestige by their progressive methods of manufacture, as it is their intention to increase their facilities by the installation of the most up to date cutlery equipment.”

In October of 1922, vice president Henry Hirsch traveled to New York to appoint a new manager for American Cutlery’s east coast office and to preach the company’s positive new gospel.

“There is a more optimistic tone throughout the entire trade,” he told The American Cutler magazine, “and both retailers and jobbers are more ready to buy than they have been for many months. Stocks are low in all sections, and we anticipate an early resumption of ordering in larger quantities. The trade has had its fill of cheap prices and inferior quality in imported goods. Dealers have more confidence in the future and are anticipating a healthy fall business in all lines of cutlery.”

“There is a more optimistic tone throughout the entire trade,” he told The American Cutler magazine, “and both retailers and jobbers are more ready to buy than they have been for many months. Stocks are low in all sections, and we anticipate an early resumption of ordering in larger quantities. The trade has had its fill of cheap prices and inferior quality in imported goods. Dealers have more confidence in the future and are anticipating a healthy fall business in all lines of cutlery.”

Just days after making that statement, Henry Hirsch died suddenly of heart failure at New York’s Hotel Claridge. He was 57. Within a year, his older brother Isaac died, as well, leaving Moses Hirsch in charge of the entire operation.

Generally, you might expect that the Moses, now approaching 60 himself, would stick to what he knew best and try to keep the cutlery business going, while perhaps putting his young nephew Lawrence Powell in charge of the upstart kitchen scale business. Instead, things developed in the opposite manner.

Lawrence Powell organized his own cutlery enterprise, the American Stainless Knife Company, and purchased American Cutlery from his uncle in 1928, likely right before the market crash of ’29 would have sent it under anyway. In turn, for the next 23 years, Moses Hirsch served as the hard-working chief of the now independent American Family Scale Company. The kitchen scales that had once been a side hustle for the Hirsch family wound up being their longer lasting legacy in the 20th century, with AFSCo. remaining in business into the 1980s.

Meanwhile, the old American Cutlery factory on Mather Street—and Mather Street itself—were finally consumed for good, as Interstate 90 arrived in the 1950s, destroying everything in its path.

[1905 Postcard featuring what appears to be our exact model of American Cutlery Scale]

[1905 Postcard featuring what appears to be our exact model of American Cutlery Scale]

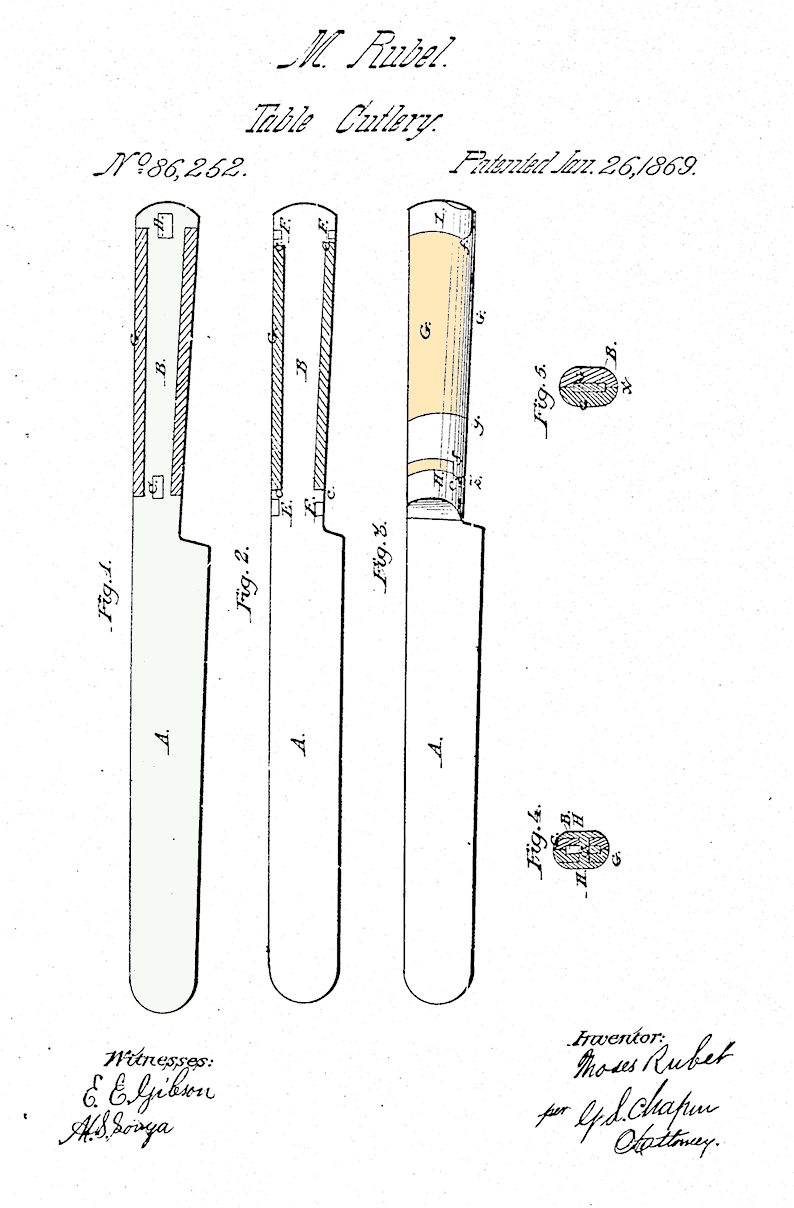

[Moses Rubel patent drawing for “table cutlery,” 1869]

[Moses Rubel patent drawing for “table cutlery,” 1869]

Sources:

Chicago and Its Resources Twenty Years After: 1871-1891, by Royal L. La Touche

“Chicago Cutlery Official Dead,” The Hardware Review, December 1922

“Moses Rubel,” Chicago Tribune, March 12, 1886

Iron Trade Review, Jan 10, 1918

Table Talk, vol. 30, no. 3, March 1915

American Cutler, Jan 1920, Feb 1922

“American Cutlery Co” – The InterOcean, May 4, 1902

German Workers in Chicago, by Hartmut Keil and John B. Jentz, 1988

United States Circuit Court of Appeals Reports, 1901

National Knife Collectors Association Gazette, Vol 6, Issue 10

Patent Interference Practice Handbook, by Jerome Rosenstock

Hardware Age, Vol. 122, 1928

Archived Reader Comments:

“The historical society museum I am curator for here in Vermont just had a bread maker donated to us, made by American Cutlery Company when it was at 732-764 Mather St. The latest patent listed on it is Dec 25, 1906. So any idea what date it might be? It’s called the Majestic Bread Maker, No. 40, and it seems to have all its parts.” —Elizabeth, 2019

“I am Isaac Hirsch’s granddaughter. My father Edwin W. Hirsch, 1904-91, was the child of Isaac’s second marriage– to Florence Waixel, whose father founded the Morris and Waixel Packing Co. I would love to know where you found this information– it’s wonderful and more than I and my siblings ever knew! Please contact me.” —Susan Hirsch Schwartz, 2018

“I am Moses Hirsch’s grandson and knew your father a little. I have been working on a family history and also looking for Hirsch photos of which I have none. I do however, have a portrait of our great grandfather Meyer Hirsch.” —William Gould, 2018

I have a counter top beam scale .it has a platform 9.5″ x12.5″ also has dry goods pan on top there is no model numbers on it any where. it missing parts underneath that holds balance arms .any drawings of it would help. thanks Reed

Hello there my name is Ron Sigafoos, I have an American cutlery butcher knife, which has a14inch blade & a 6 inch rosewood handle. It came with a cardboard sheath with the address written all over it at the butcher shop where it was used. Which is not there anymore. Just wondered more about the knife. 3/29/2024

I have a scale like the one’s in the pictures above only on the name plate it reads ARIOSA COFFEE FOR 30 YEARS THE STANDARD. Could anyone tell me what the value would be?

What is “RUBEL’S PAT.” and the dates?

I recently acquired a scale that is the same as the one pictured above. I am looking to send to an auction house. But, I cant find any good resources. Any ideas of value? Collectors?

I have a 3 piece carving set with American Cutlery Company marking on blade. I can not tell whether the handles are bone, antler or ivory. There is a sterling silvery band with a design.

How can I identify the style and age?

I have a 6 pc steak knife set with pearl handle and the blades are imprinted with 1865. I don’t know what the blades are made of. Can you tell me?

I would love to see a picture of what you have there. I am doing research on knives from the Pre Chicago cutlery days and would be glad to share and info on these American cutlery knives if i can with you. I am an avid knife collector and I just find this hobby so rewarding especially when I see something old that has been kept and cared for knowing how special they are as well to someone else and hearing the lineage and stories are so interesting. If you would Please and thanks.

Jason

Hello, please post a picture. I am an avid knife collector and would love to see what you have there. Who knows maybe I’ll come across what you are looking for. I have been doing research on pre Chicago cutlery information and just seeing what you got there will help me to look in my travels. I would appreciate it immensely.

Thank you, Jason

I have a carving set with the antler handles but it is missing the sharpening tool. This is marked American Cutlery Company 1955. If anyone has the sharpener to this set I would be interested in getting one.

i found a victor 14 inch wire handled bread knife blade is 9 1/2 inches blade width is 1 1/4′.

has a dfjn stamped by usa..wondering when american cutlery co. started victor brand. and about how old do you think it is. matter of fact there was a stamping problem on mine the capital v is missing. Thank you very much have a day. Craig Yerke of PA.

I have about 7 Chicago Cutlery knives labeled ACR followed by a number. They are the bio-curve handles.

Does anyone know any history about the ACR series.

I would Love to see a photo of your collection. I too am a collector and am very intrigued to see the antiques and just learn more about what knives are of there that so I may find or help me to see what to look for anyway. I hope you know what a treasured Items you have there. I own a Bio-curve set of Chicago cutlery NSA Certified with Poly Handles. It would be cool to see what you have there. Perhaps I may be able to do some research to share with you.

Please and Thanks,

Jason Saltzman

I recently got a set of knives from a yard sale and im trying to figure out what year they are from. They are from the American cutlery company. The logo on the knives just says american (trash can shape design) cutlery and then underneath company with the p in the design. They are fruit knives with a mother of pearl handle and sterling silver blade and middle part. I could email a picture to yall if you would like, do you happen to have any more information on these? I also loved this page because i learned so much about this company and found it very intriguing 10/10 job.

Trademark 1892

Cf Library of Congress

https://www.loc.gov/resource/trmk.1t18795/

In the late 1800’s, two of my great-uncles were employed at the Norwich Cutlery Works in Norwich, CT. Both of them died young and both of their wives died young of a “lingering sickness lasting some years”. Could those Uncles have been bringing a hazardous material home from the cutlery that my aunts were also exposed to while washing their work clothes?

I am interested in seeing a photo of your knife. I am a collector of Chicago Cutlery and I am putting together the history of the pre company lineage. Plus it is so cool learning about the antiques I believe that it will help me while I’m looking for these Treasures.

Please and ThankYou,

Jason

I have a ‘parang’ shaped knife with a 3 quarter tang wood handle labeled American Cutlery with “1865” logo in between the words American and Cutlery. Any insights? I have looked online, and have only seen pictures of a normal ‘square’ style butcher knife by this company; have yet to find a pic of the ‘parang’ style I own, or any information about it. Any thoughts?

Hi, I was the person who was sales manager of American Family Scale in 1967-71 after which I was president. We introduced avocado, and then harvest gold kitchen scales in the time frame noted below:

Mix-or-Match Colors [introduced in 1955] gave way to Coppertone (1964), Avocado (1966) and Harvest Gold (1968) — all of which were darkened around the front edges of the appliances. These new colors went hand-in-hand with the Danish modern look of the late 1960s. During this time, color remained a critical factor for fashion-conscious …

These were later followed by chocolate brown – anything we could do to keep scales on the shelf

What year were the avocado green scales produced

I have a 1865 barber blade shaver inscription on the blade R-E-X and engraved inside the wooden handle H.E in red. Do you know if it’s worth still in the actual box container.

I’m interested in seeing a picture of your set of knives i am a knife collector putting together a documentary of a complete history of before Chicago cutlery and to present day production.

Please and ThankYou,

Jason S.

Hi there. I am trying to date a set of ten knives and a carving set made by American Cutlery Company. The handles are mother of pearl and the band is marked sterling.

Yes i have the same ones! Im trying to find out more about mine too.

have 3 pcs of american cutlery stag/silver.carving set. knife reads american cutlery 1865. any ideas as to when this style of ware was popular. would love to know the age of this stuff. i love history and live south of chi town. thanks

We have a carving knife with a gorgeous red stag handle and engravings of aquatic scenes with a frog on one side and and a turtle on the other side in a silver band where the blade meets the handle. One side of the blade is stamped with:

“AMERICAN CUTLERY

COMPANY”

with 1865 slanted above the P contained in what looks a bit like a keystone. Any ideas as to when it was made? Thanks for any info you might be able to provide!

yes……thats the same markings i have. would love to know what im holding.

Recently found a large butcher knife (10 &1/4″ long blade) that has stamped with an eagle and shield and below on a banner, “American Cutlery Co.” Your thoughts?

There were knives, forks and spoons used by the Army in WWI that were marked ACC and knives in WWII also marked ACC, were these made by American Cutlery Company? There was also Aerial Cutlery Company and some collector’s claim ACC was the AERIAL logo, can anyone verify this or have any information that can verify this?