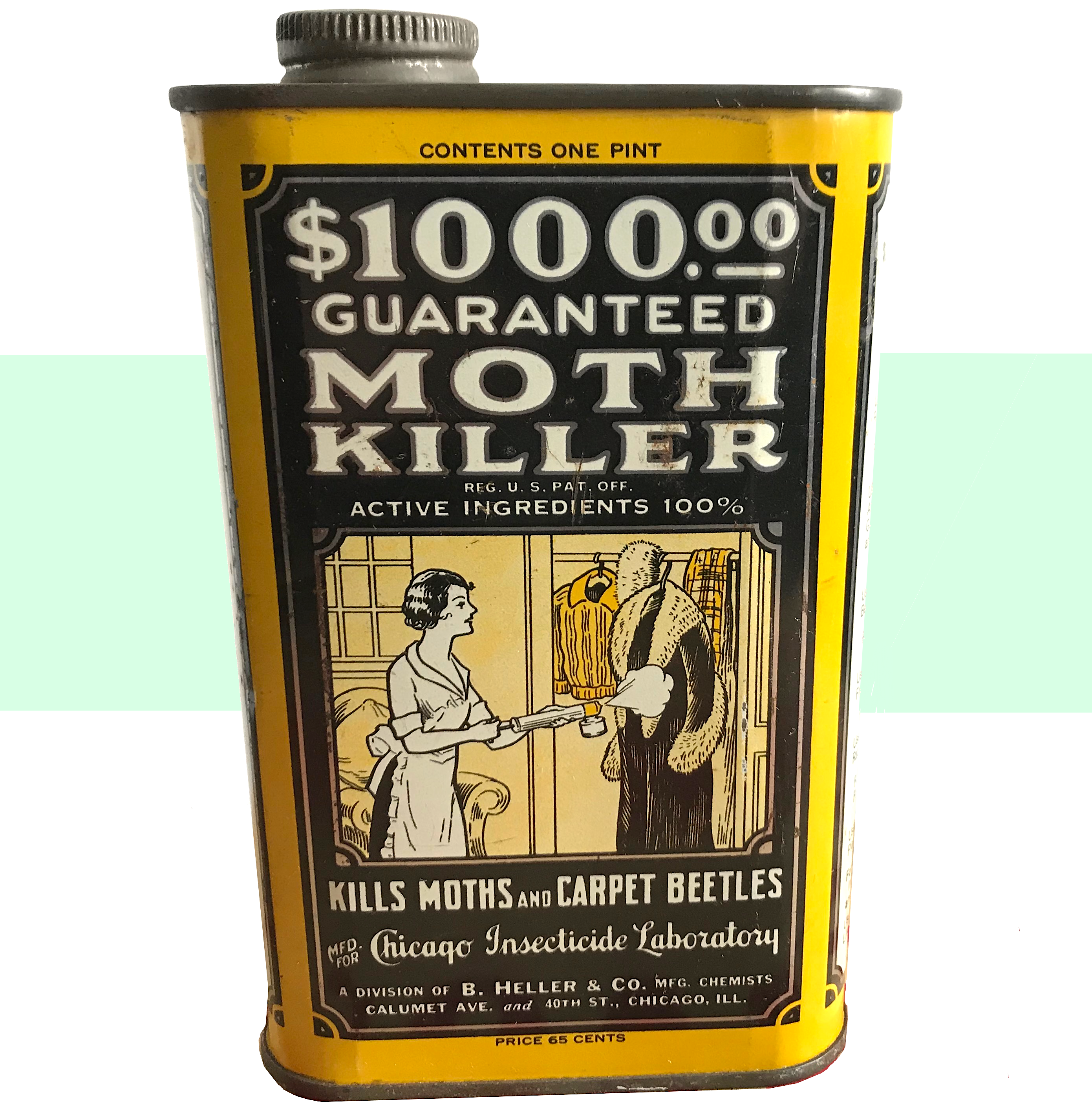

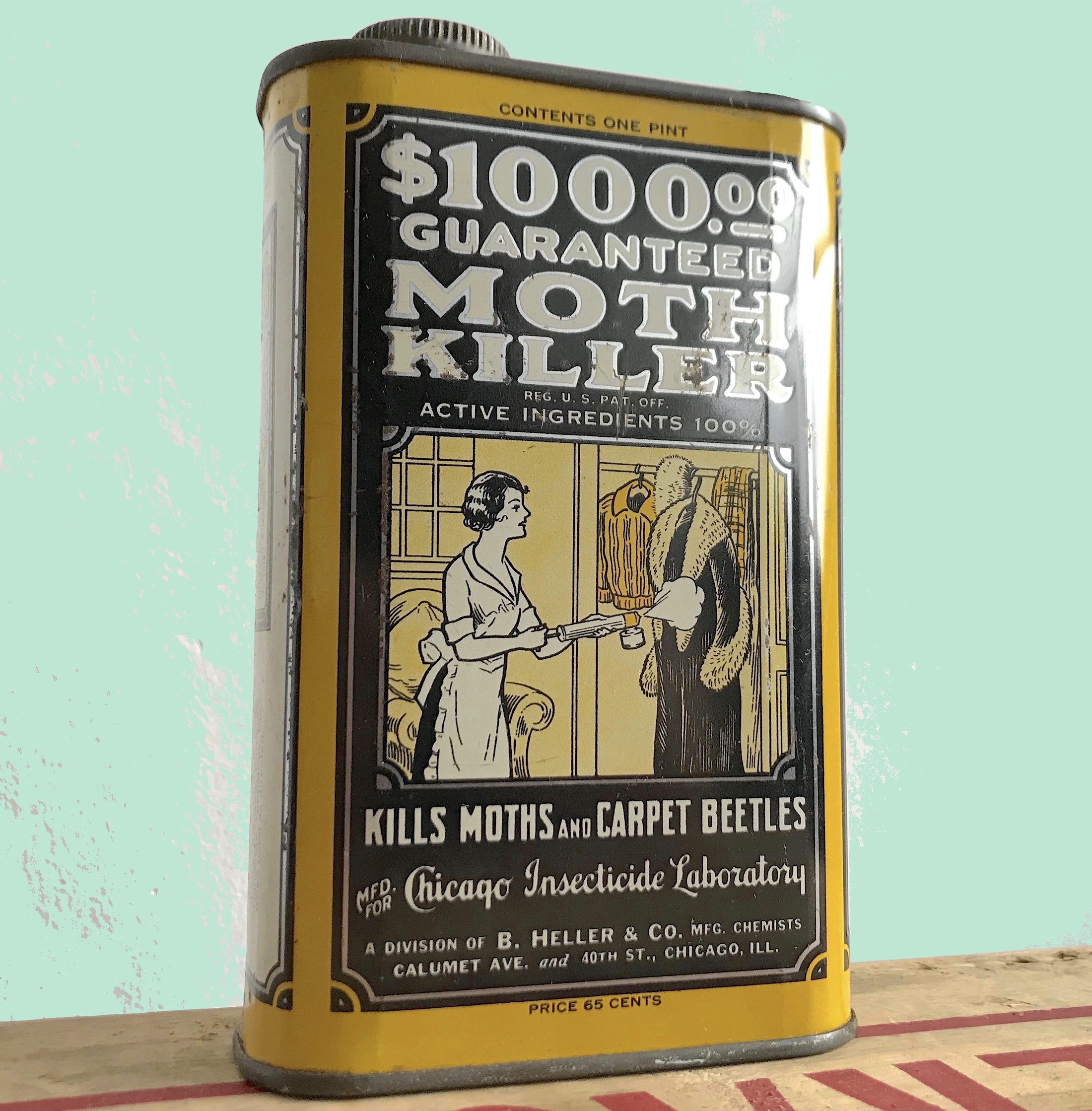

Museum Artifact: $1000 Guaranteed Moth Killer, 1928

Made By: B. Heller & Co. / Chicago Insecticide Laboratory, S. Calumet Ave. and E. 40th St., Chicago, IL [Bronzeville]

“We guarantee that $1,000.00 Guaranteed Moth Killer will kill clothes moths—and carpet beetles and their eggs and larvae—when it is thoroughly sprayed upon them, and agree to forfeit $1,000.00 to anyone proving to us that it cannot do this.” —Chicago Insecticide Company, division of B. Heller & Co., 1927

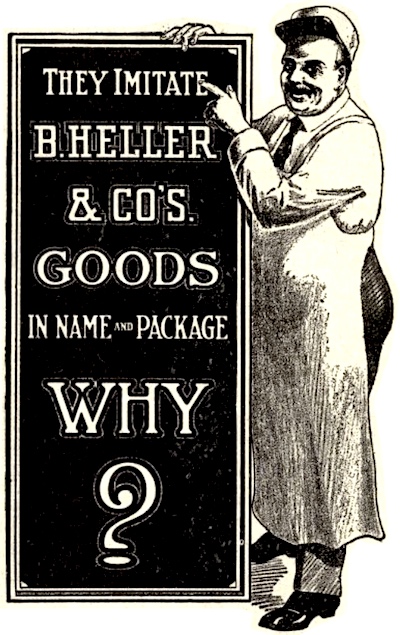

It’s highly unlikely that Benjamin Heller ever paid a cent to a dissatisfied moth hunter, let alone a cool grand, but he certainly understood how to grab someone’s attention with a striking label and a marketing gimmick.

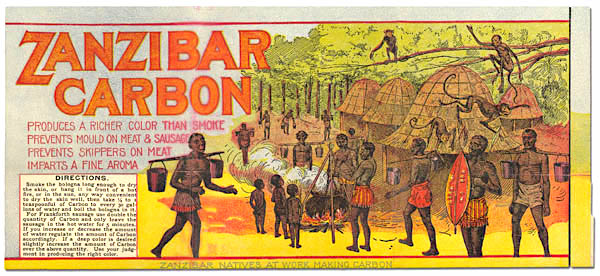

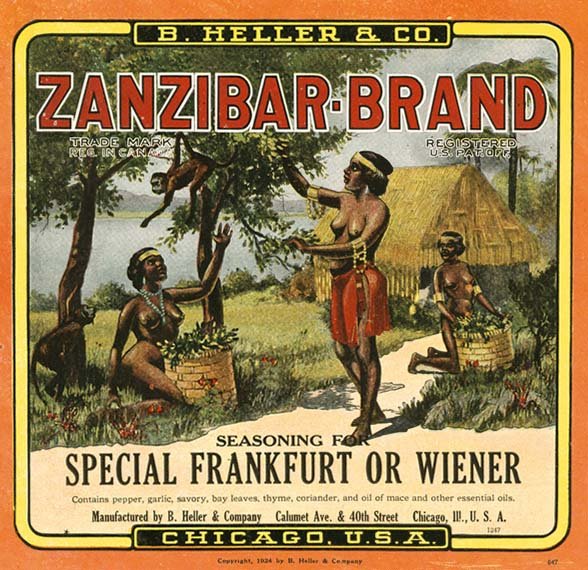

Heller’s chemical manufacturing business, B. Heller & Co., was founded in Chicago in 1894, and originally focused on selling additives to the butcher’s trade during the dark ages of the Union Stockyards. Once it crossed the 20th century threshold, however, the family-run firm quickly diversified its interests, offering an exponentially enlarging line-up of colorful products all cooked up in the mysterious Heller labs. These included the “Zanzibar” line of seasonings and preservatives (famed for its unfortunate depiction of topless African tribal women on the packaging), as well as “OZO” cleaning products, “VanHeller” food flavorings, “Bull-Meat Brand” flour, and the “1,000.00 Guaranteed” label—which was slapped on everything from vanilla bean extracts to insecticides like the Moth Killer currently residing in our museum collection.

Heller’s chemical manufacturing business, B. Heller & Co., was founded in Chicago in 1894, and originally focused on selling additives to the butcher’s trade during the dark ages of the Union Stockyards. Once it crossed the 20th century threshold, however, the family-run firm quickly diversified its interests, offering an exponentially enlarging line-up of colorful products all cooked up in the mysterious Heller labs. These included the “Zanzibar” line of seasonings and preservatives (famed for its unfortunate depiction of topless African tribal women on the packaging), as well as “OZO” cleaning products, “VanHeller” food flavorings, “Bull-Meat Brand” flour, and the “1,000.00 Guaranteed” label—which was slapped on everything from vanilla bean extracts to insecticides like the Moth Killer currently residing in our museum collection.

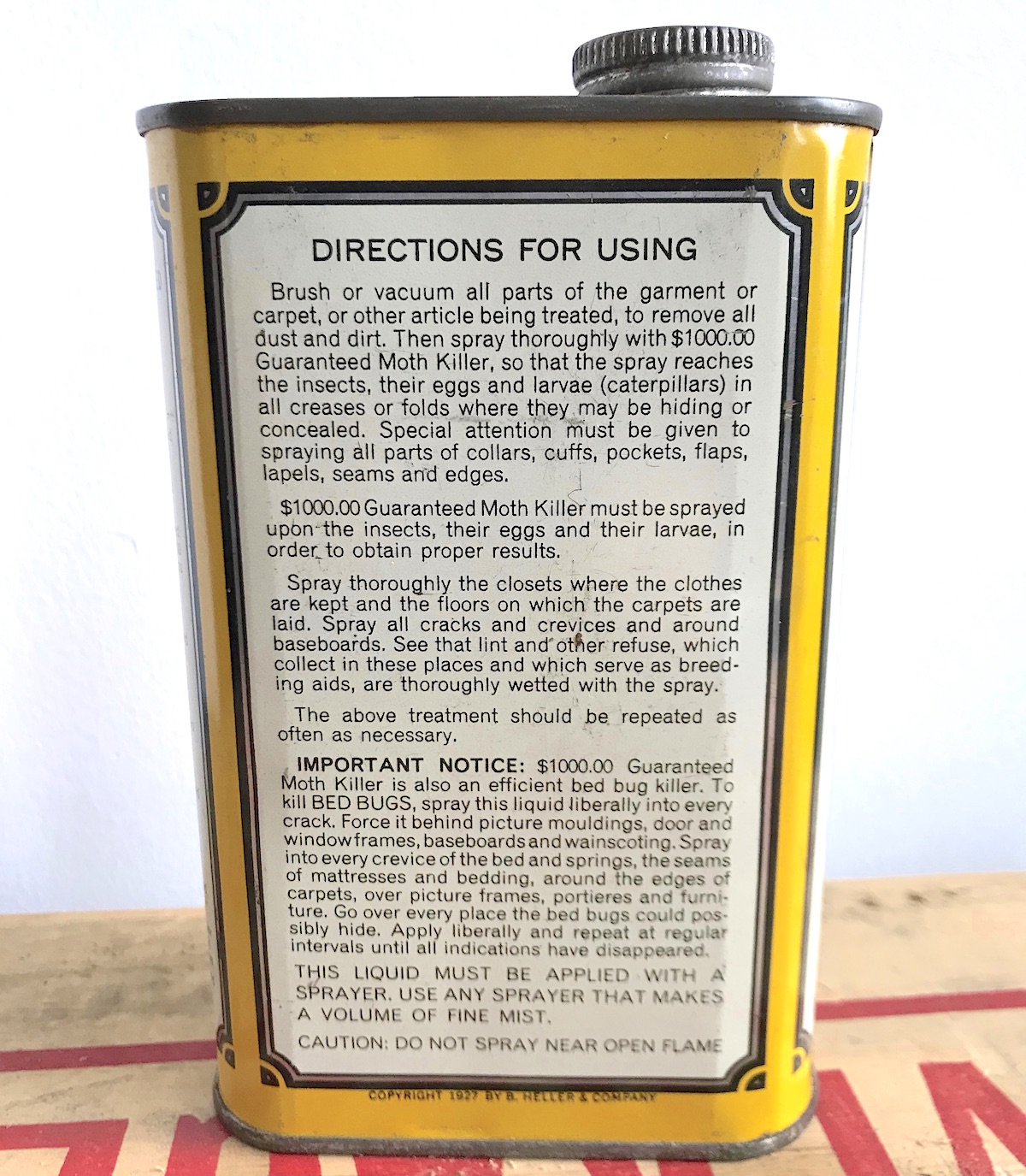

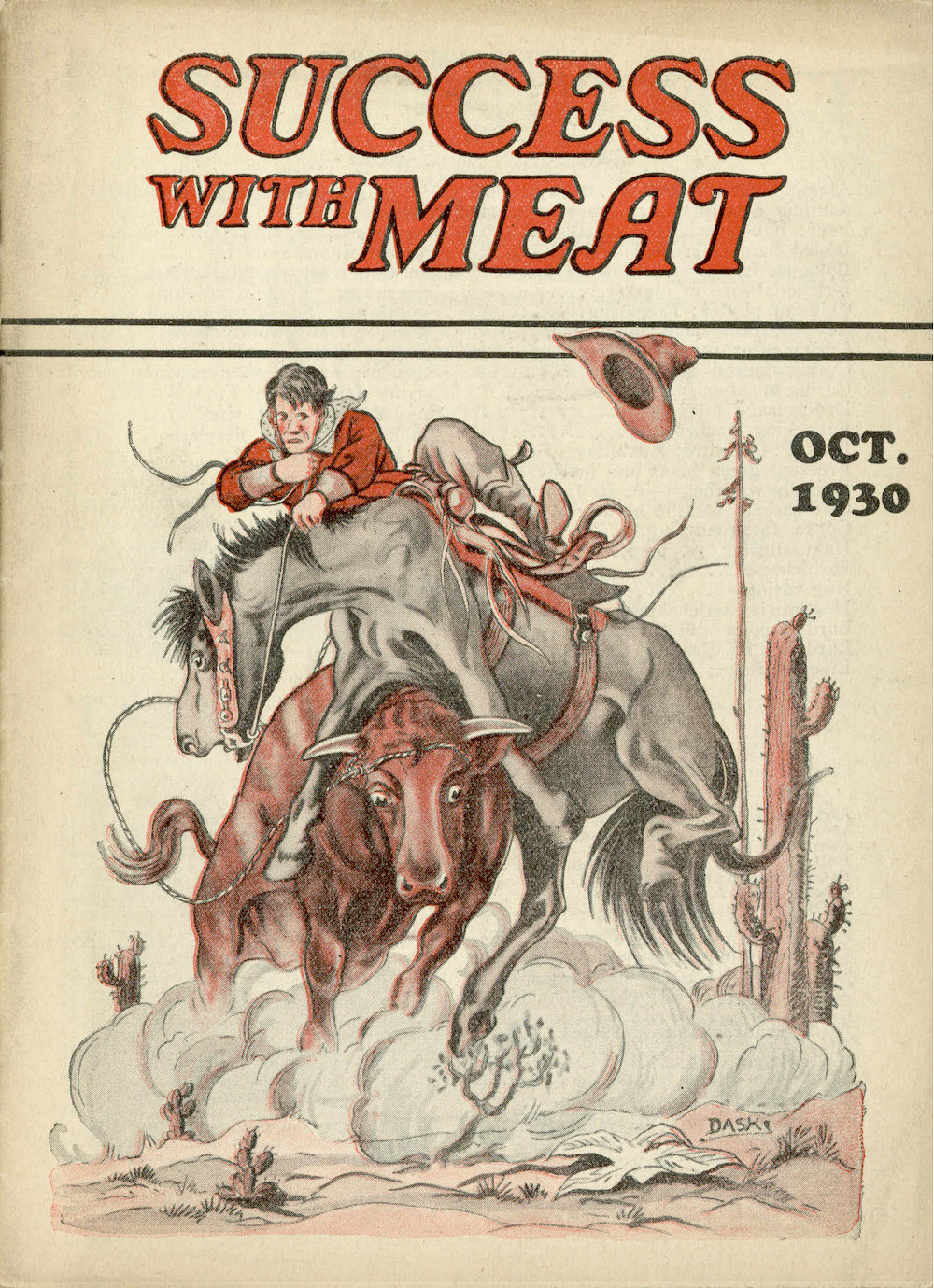

Along with eye-catching graphics, Heller products usually packed plenty of reading material on to their labels. Our lovely black-and-gold Moth Killer tin basically functions like a promotional pamphlet unto itself, covering everything from the aforementioned “$1,000.00 Guaranty” to detailed instructions for effective moth murder; bonus tips for bombing bed bugs; cross-promotions for several other Heller critter killers; a full list of acceptable fabrics for spraying (furs, woolen and silk garments, worsteds, rugs, carpets, pelts, robes, blankets, portieres, hangings, tapestries, etc.); the complete Heller factory address (Calumet and 40th St., Chicago, ILL); and numerical indications of the container’s volume (1 pint), price (65 cents), and percentage of “active ingredients” (100%).

Just about the only details NOT included on the can, amusingly, are the actual names of those active ingredients.

Today, any consumer pesticide container is required by law to include a standardized litany of warnings related to any hazardous contents therein—including all the potentially gruesome health risks they could pose to you, your pets, your children, and the very world as we know it. In Benjamin Heller’s day, by contrast, pesticides didn’t even require labels—at all—until the Insecticide Act of 1910. Later, in 1927, the Caustic Poison Act finally forced companies to list any dangerous chemicals on their labels, as well as antidotes / treatments for anyone put into contact with the bad stuff. Since our (thankfully empty) can of Moth Killer has a 1927 copyright, it must have gotten in just under the wire of the new law, and thus offers us zero insight into what its magical bug murder formula might have contained. A basic caution about not spraying “near open flame” is the full extent of the safety language here.

As regulations continued to improve over the decades, B. Heller & Co. did eventually fall in line, settling into a long existence as a seasonings producer for the food-service industry, with several generations of the Heller family carrying the baton. Like a lot of perfectly legitimate food and drug companies of the 20th century, though, this business was built on an ethically ambiguous foundation, as bold marketing and pretty packaging often shrouded some pretty shoddy science underneath.

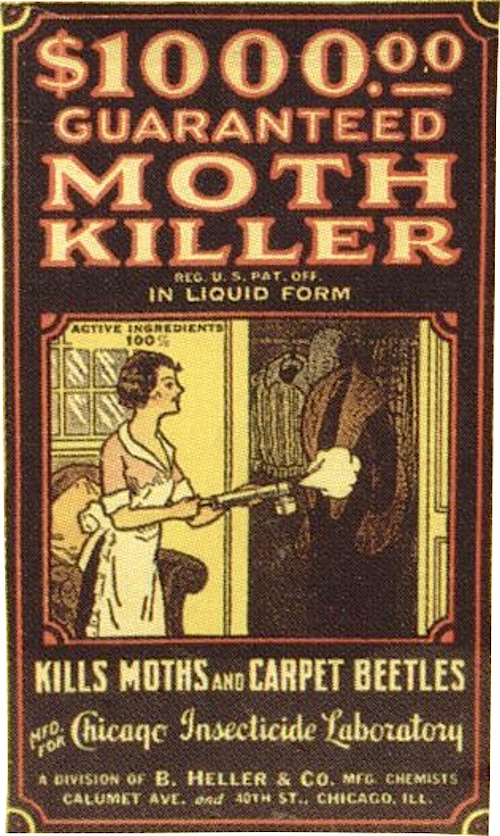

[Original advertising mock-ups for some B. Heller & Co. packaging, 1920s]

[Original advertising mock-ups for some B. Heller & Co. packaging, 1920s]

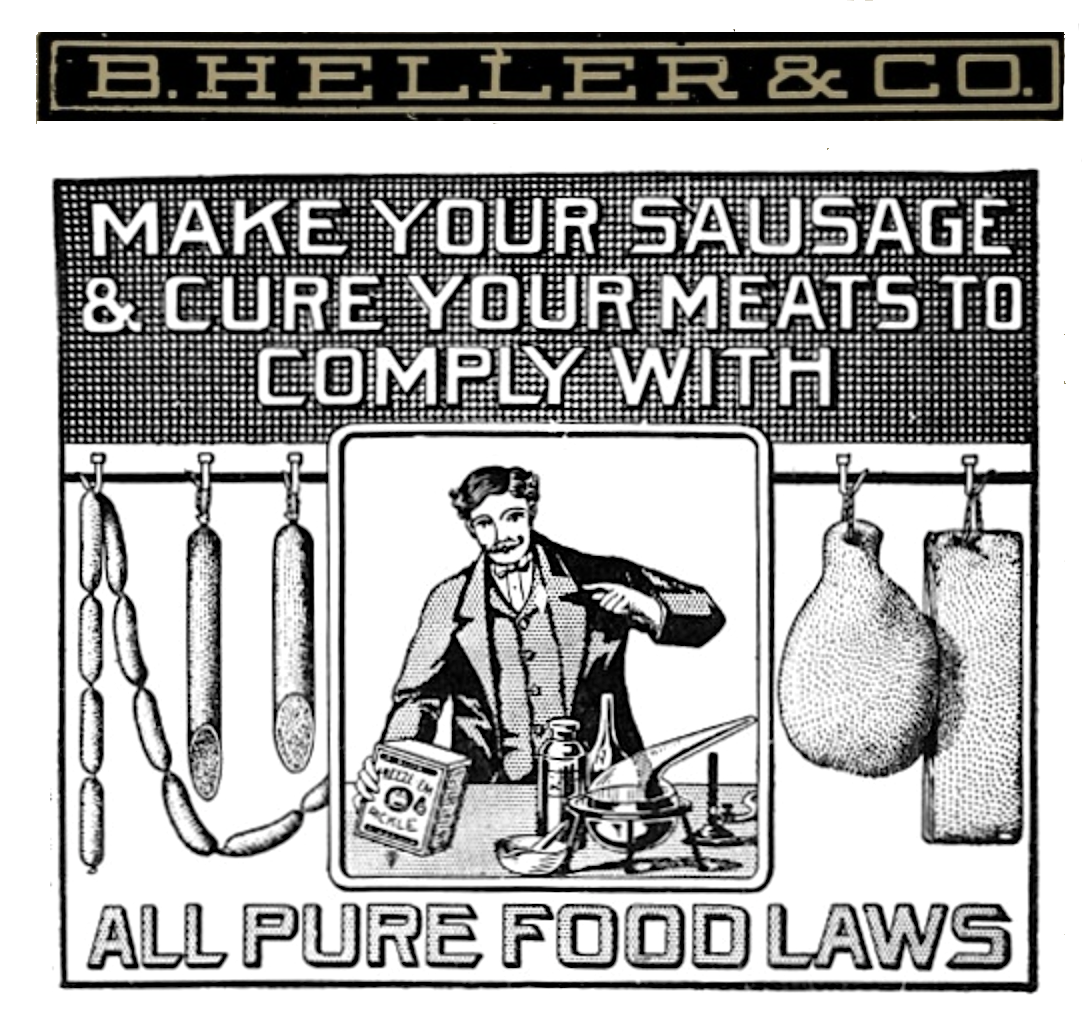

History of B. Heller & Co., Part I. Sausage Folks

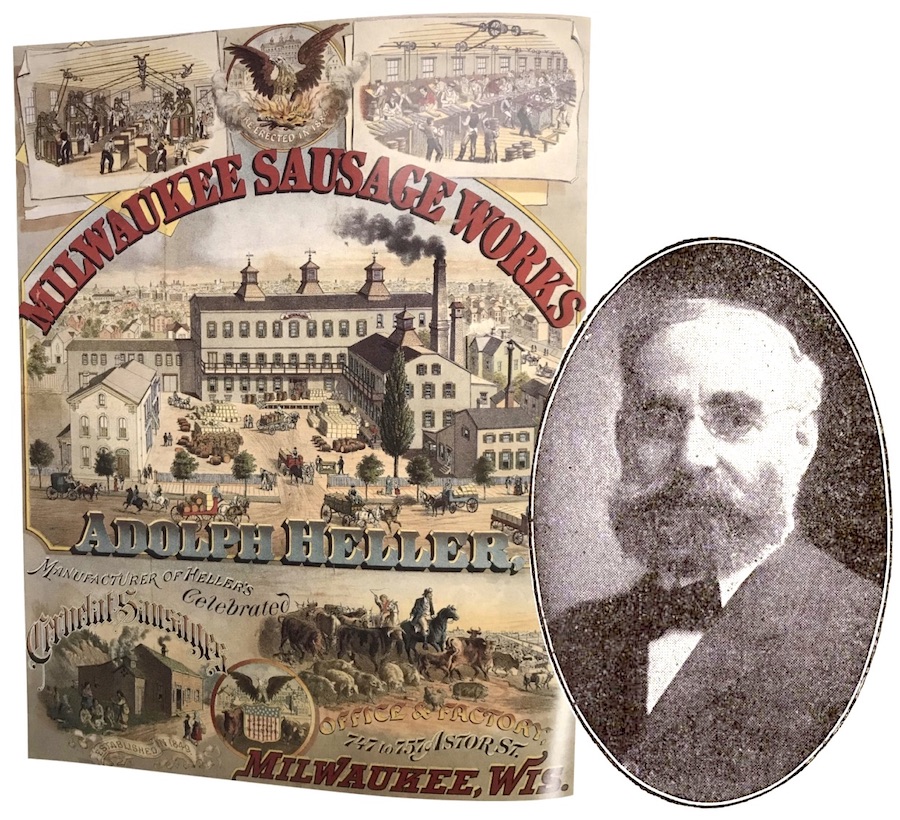

No one could question Benjamin Heller’s background when it came to the craft of meat preparation. His family included a long line of Bavarian and Bohemian butchers, with grandfather Bernhard Heller first taking the tradition to the New World when he moved to Milwaukee in 1848. From there, Benjamin’s dad Adolph Heller and his mother Bertha Frank (daughter of a leading Bavarian sausage factory owner) turned the family wholesale butcher business into the Milwaukee Sausage Works: one of the Midwest’s top producers of summer sausages.

That business relocated to Nebraska City in 1886, then on to Sioux City, Iowa, where Benjamin and several of his brothers joined their father, forming A. Heller & Sons.

“Adolph Heller was a scientific and practical butcher and packer, and a practical sausage manufacturer,” according to a pamphlet later released by B. Heller & Co. “He studied the causes of failure in the handling of meats, with the aim of always producing the best and most uniform products that could be made. He was so successful in his business that his products were known and recognized as the best.”

It’s hard to fact-check such claims after 130 years, but it’s safe to say that no amount of esteem was going to be enough to keep the Heller family competitive against the rise of the supergiants of the meat packing industry, including Chicago’s Armour & Co. and Swift & Co. With the railroad creating new distribution tentacles for the big boys, smaller operations were collapsing one after another in the 1890s. Adolph Heller might have been in denial when it came to this new reality, but his eldest son Benjamin seemed keenly aware that survival would require adaptation.

Ben’s first shot at a new venture came in 1893 when, at the age of 25, he attended the famed World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago and—like so many others—caught a wave of inspiration. Some of the vendors at the fair were serving small sausages on a bread roll, promoted as “frankforts” or “wieners”—and Heller rightfully saw a new sensation in the making. Upon returning to Sioux City, he started up one of the first frankfurter concessions in Iowa—despite the doubts of his perplexed papa—and made a nice profit from it.

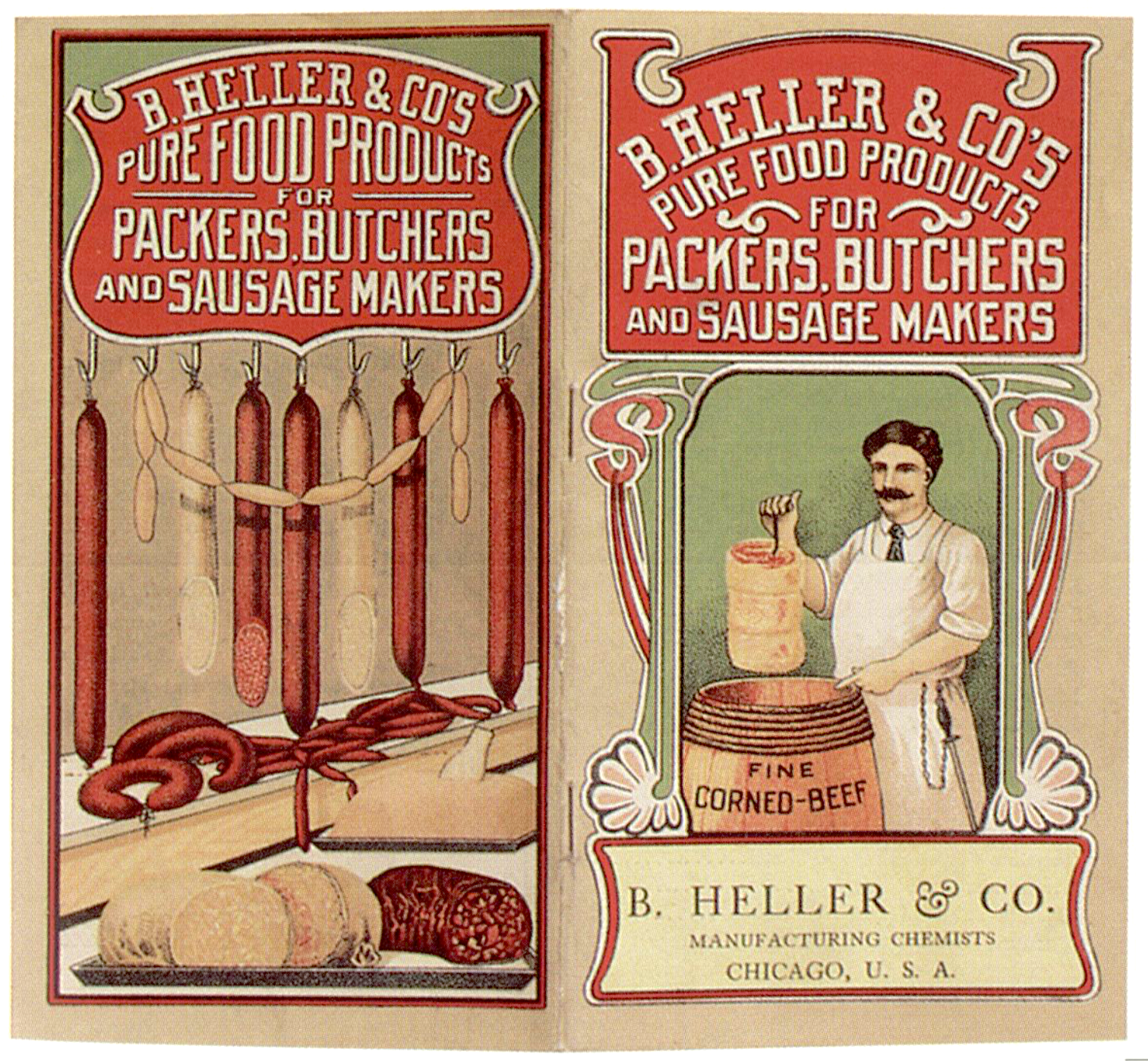

By the following year, with A. Heller & Sons still on a downward spiral, Benjamin officially broke out on his own, using some of his hot dog cash—and some insider research on modern meat preservation science—to start a new enterprise. It was aimed not at competing with the Swifts and Armours of the world, but at piggybacking off of them, in a way (sausage pun intended). If the butchers of America wanted to procure their meats at low cost from the supergiant packing firms, that was fine. But if they also wanted that meat to somehow last longer, look more appetizing, and ultimately taste better than the identical meat coming out of other butcher shops in town . . . that’s where B. Heller & Company would be more than happy to step in.

II. The Exotic Sciences

Returning to the city that had inspired him, Ben Heller set up his first office at 199 S. Canal Street in Chicago in 1894, advertising his humble new business as “B. Heller & Co., Butcher’s Specialties.” This later evolved into the more sophisticated sounding: “B. Heller & Co., Manufacturing Chemists.”

According to his granddaughter Sally Loeb, it was a DIY effort in the truest sense, as Ben supposedly lived in a Chicago boarding house that first year, and would have to get up in the middle of the night, mix his formulas in the bath tub, then clean the tub thoroughly so the other boarders were none the wiser. Things would eventually get more sophisticated on that front, too, as Heller wound up living in a Hyde Park mansion before it was all over.

According to his granddaughter Sally Loeb, it was a DIY effort in the truest sense, as Ben supposedly lived in a Chicago boarding house that first year, and would have to get up in the middle of the night, mix his formulas in the bath tub, then clean the tub thoroughly so the other boarders were none the wiser. Things would eventually get more sophisticated on that front, too, as Heller wound up living in a Hyde Park mansion before it was all over.

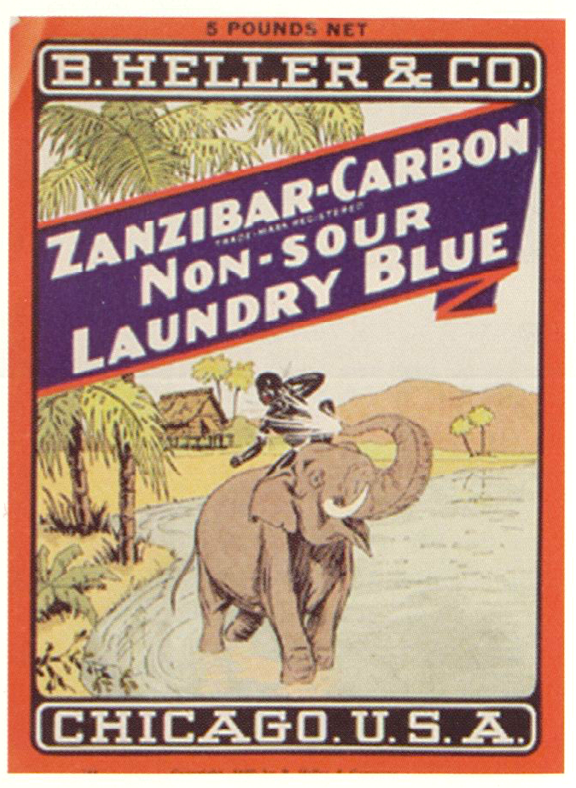

In the beginning, the whole enterprise really hinged on one product, which Heller developed and brought with him from Iowa. It was called “Zanzibar Carbon,” a dry mixture that butchers could dilute in water (one teaspoon to every 30 gallons) and then boil sausages in. Beyond a mere preservative, this odd little potion was said to “produce a richer color than smoke, prevent mould on meat and sausage, prevent skippers on meat, and impart a fine aroma.” That sales pitch, combined with the unusual product name and packaging, usually made an impression.

Heller had selected the name “Zanzibar”—a region now part of the African country of Tanzania—merely as a ploy to make his preservative sound more exotic and exciting, while still also vaguely natural and “of the earth.” The accompanying artwork depicting half-naked African tribesmen and women, usually in the act of either gathering food or hunting wild beasts, further gave the impression that the ingredients might have been imported directly from Zanzibar itself. They were not—and in fact—a later study by the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station found that Zanzibar Carbon was made almost entirely out of common salt and a brown coal tar dye. Not so exotic after all.

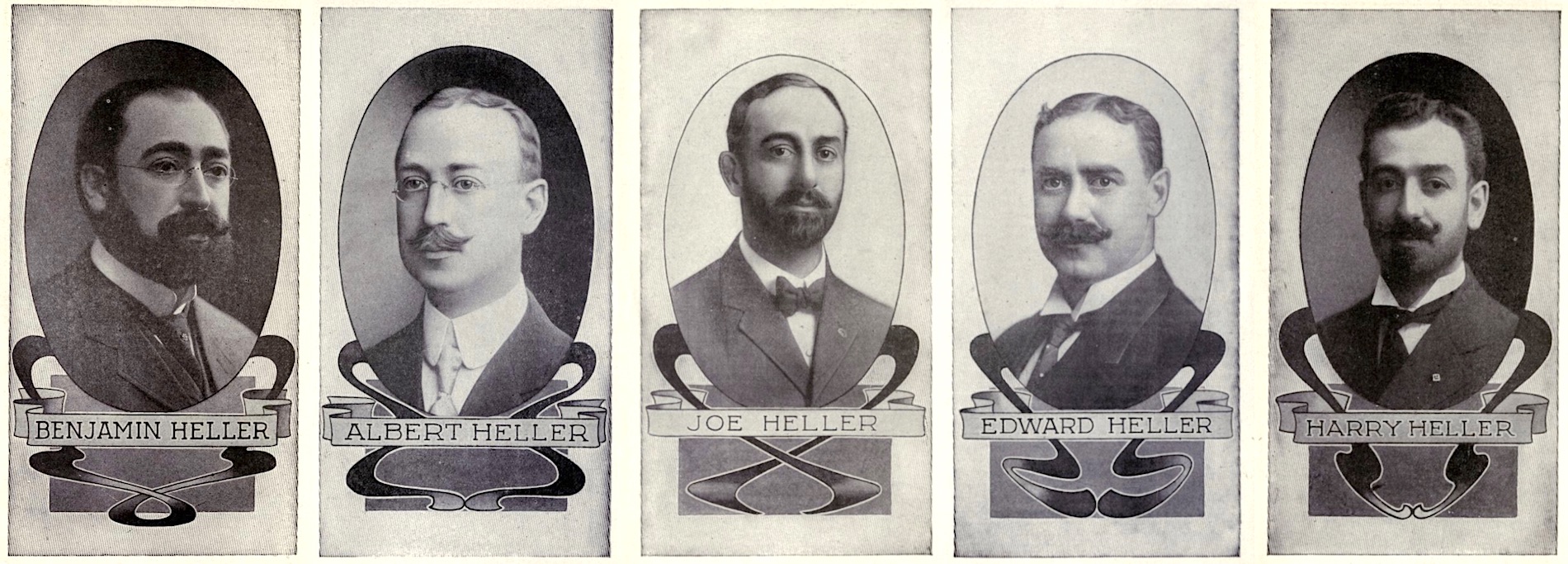

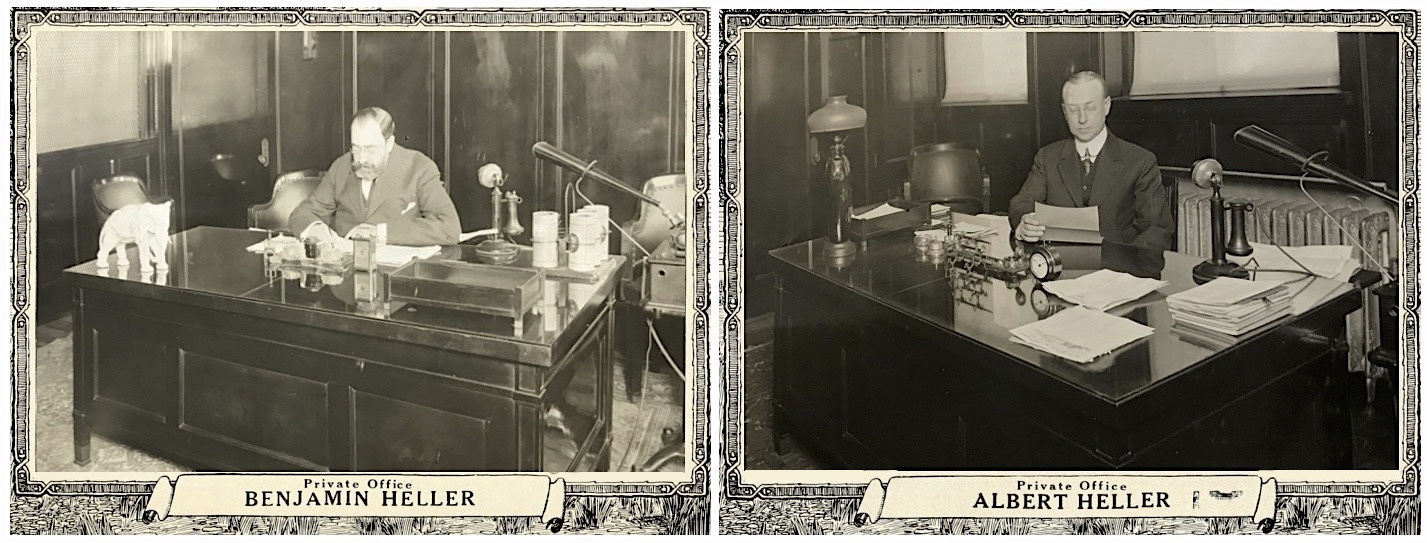

In the meantime, though, the product was a huge success, and within a couple years, Benjamin was doing well enough that his brothers—first Harry, then Albert, Edward and Joe—all joined him in Chicago, establishing a larger headquarters at South Jefferson Street, between Harrison and Van Buren.

Albert Heller, just two years younger than Benjamin, became something of a yin to his yang; an introvert who was more than happy to manage the dull day-to-day bookkeeping and correspondence in the office—freeing Ben to ride the rails and sell sell sell. “Anyone seeing them together would never surmise they are brothers,” the company’s magazine later noted. “Yet that they are chips off the old block is apparent when one enters into conversation with them. Albert is a good listener, a good writer, and when he talks, he always says something.”

As for the younger Heller brothers, Benjamin set about training them as expert salesmen in his own image. In one instructional letter he wrote to Ed, he explained that a sale often starts with a simple observation. “I can walk into a shop and notice that a man is making his own bologna and uses no color—you can always tell by the appearance of his goods.” From there, rather than immediately introducing himself as a businessman selling a product, he’d pose more as a mysteriously well-informed passerby—peaking the butcher’s curiosity before finally unveiling the goods in question.

Persistence was also a big part of the playbook. “If you don’t get through a town in one day,” Ben told Ed, “stay there two. Take all the time you need to work a town and work it.”

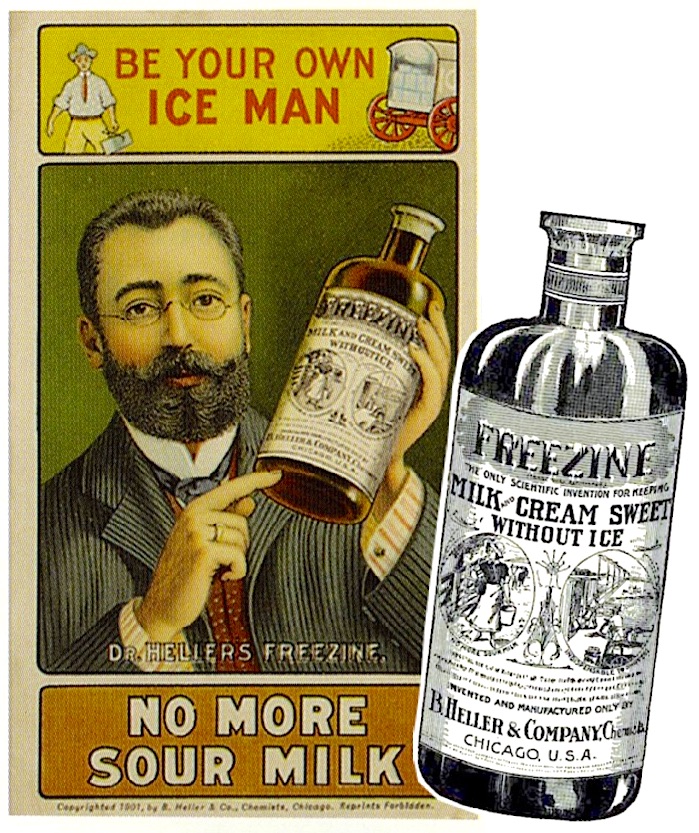

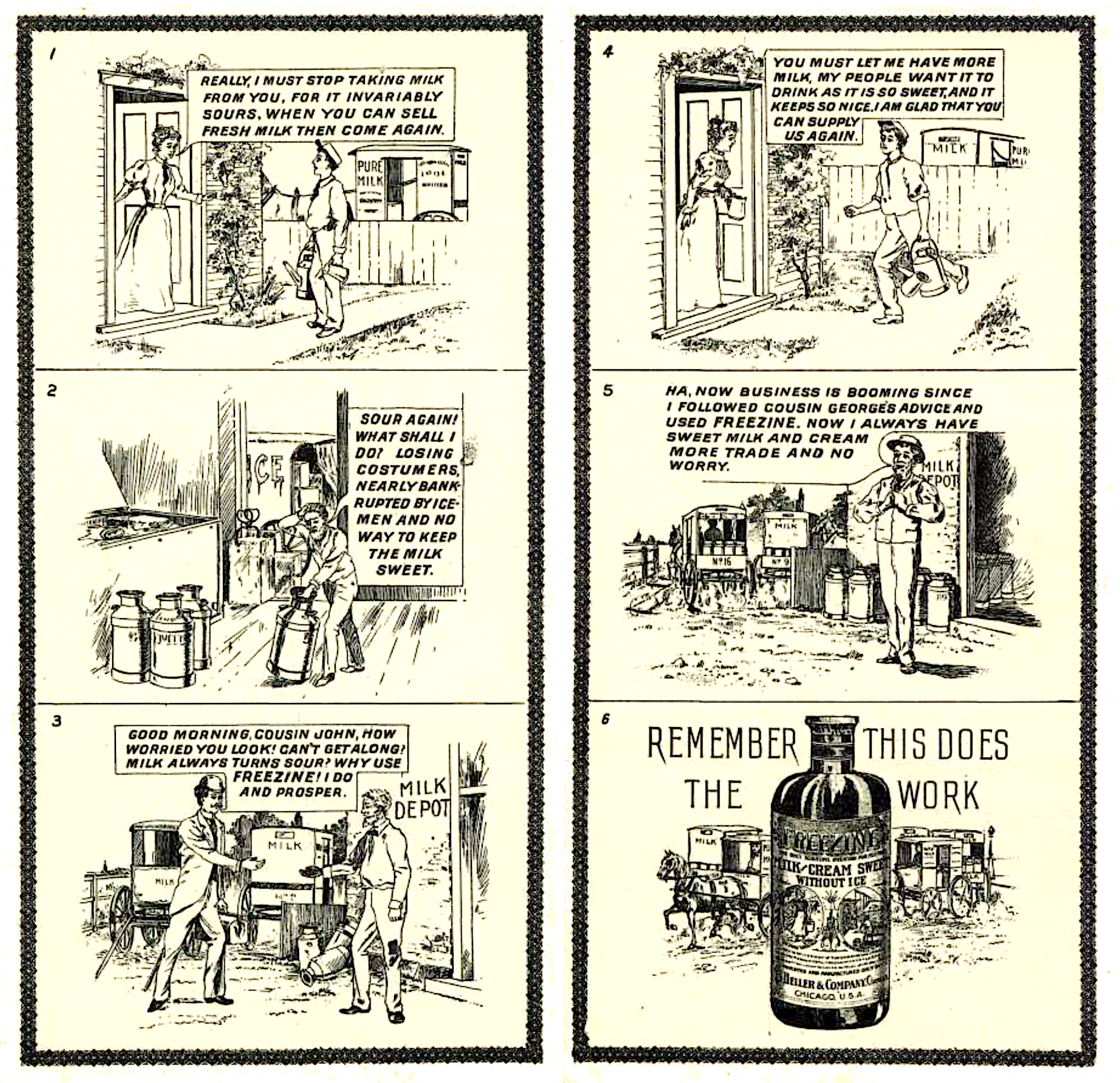

By 1900, these tactics helped the business grow from Ben Heller’s original $500 investment to $60,000. Another big boost came from a new product called Freezine—marketed to dairymen as a way to preserve milk without the need of refrigeration.

“The advantages gained by using FREEZINE,” according to a turn-of-the-century Heller sales pamphlet, “are that the Milk and Cream will remain perfectly sweet and fresh regardless of the temperature of the room they are kept in.”

“The advantages gained by using FREEZINE,” according to a turn-of-the-century Heller sales pamphlet, “are that the Milk and Cream will remain perfectly sweet and fresh regardless of the temperature of the room they are kept in.”

Better still, “Freezine does not affect the appearance, color or taste of milk,” and “is perfectly harmless and not injurious to the human system, as it freezes the bacteria and evaporates quickly, leaving the milk in a perfectly healthy condition.”

Much like Zanzibar Carbon, though, Freezine soon came under severe scrutiny. In these days before milk pasteurization and electric refrigeration had become the industry standard, Heller and other companies started borrowing a key ingredient from embalming fluid—formaldehyde—to boost the shelf-life of a pint of milk. It wasn’t something they tried to deny, either—Albert Heller went as far as happily testifying before Congress in 1899, claiming that the 6% formaldehyde solution in Freezine was not only “perfectly harmless,” but “positively healthful, especially for infants who are troubled with fermentation of the stomach.”

Members of the Chicago Medical Society did not agree. At a meeting in 1900, city health commissioner Dr. A. R. Reynolds addressed the reports of more than 1,000 infant deaths in Chicago potentially linked to so-called “doctored milk.”

“If this is true even to the extent of one-tenth of one percent,” Reynolds said, “it is a matter that cannot receive too early attention. Experiments made abroad seem to indicate that formaldehyde and boric acid, the substances usually employed, are prejudicial to health, if taken even in small quantities.”

[A comic strip from a B. Heller & Co. pamphlet for Freezine: ‘A Wonderful Invention for Keeping Milk and Cream.” c. 1900]

[A comic strip from a B. Heller & Co. pamphlet for Freezine: ‘A Wonderful Invention for Keeping Milk and Cream.” c. 1900]

The Dairy and Food Commission of Michigan went a step further, informing that state’s dairy trade that “the use of formaldehyde, sold as it is under the name of ‘Freezine,’ is injurious to health and makes them liable to heavy penalties. All persons found using formaldehyde, boracic acid or other preservatives in milk or cream sold for consumption in Michigan cities and villages will be vigorously prosecuted. No more nefarious practice can be employed than to threaten American child-life by the addition of poisonous acid preservatives to the food upon which nature intended young life to subsist.”

It wasn’t until 1906, with the passing of the U. S. Pure Food and Drug Act, that all states were forced to crack down on formaldehyde’s use in milk. Overnight, Freezine was off the market, as were several other staples of B. Heller & Co’s early development, including Zanzibar Carbon. If the company wanted to continue its upward trajectory, it would somehow have to find a way to make metaphorical lemonade out of a basketful of illegal and potentially poisonous lemons.

III. A Pure Reboot

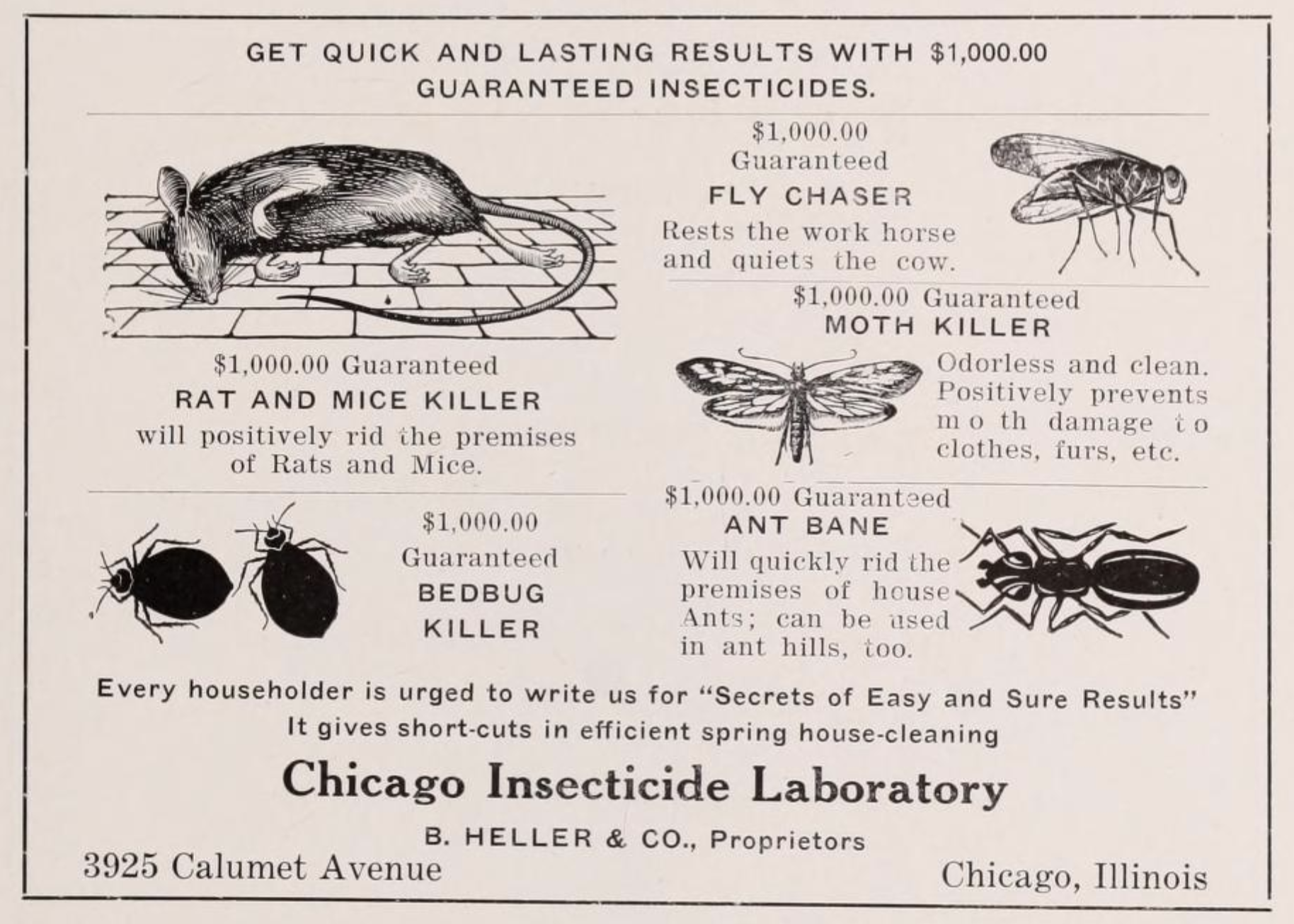

In 1905, just before the new food safety laws went into effect, Benjamin Heller started the publication of his own in-house magazine, originally called The Scientific Meat Industry, and later re-named Success With Meat. It was partially a legitimate journal for the butcher’s trade, and part propaganda material for Heller products. Okay, mostly the latter. But because Heller & Co. had successfully established a reputation as men of science for the past decade, they were quickly able to change the narrative to their advantage after the big changes of Teddy Roosevelt’s “Pure Food” campaign.

Heller’s magazine, as well as its widely distributed guidebooks, such as The Secrets of Meat Curing and Sausage Making, were fully updated to re-frame Heller not as a perpetrator of dangerous chemical preservative offenses, but as a true authority on how to work around the new government restrictions—kind of like Evel Knievel putting out a pamphlet on safe driving tips.

“The enactment of the National Pure Food Law, the National Meat Inspection Law and the various State Pure Food Laws had made a great change in the Butcher, Packing and Sausage Making Business,” Heller noted in the introduction to the 1908 edition of Secrets of Meat Curing. “The firm of B. Heller & Co. anticipated the enactment of these laws, and already had completed investigations which enabled them to assist packers, butchers and sausage makers at once by giving them curing agents which were free from the Antiseptic Preservatives which these laws prohibited, and yet would produce cured meats, sausage, etc., of the highest quality without the use of the Antiseptic Agents. The underlying principles of handling meats and making sausage with the antiseptic agents and without them are very different, and it became absolutely necessary that the firm of B. Heller & Co. should furnish their friends and customers such information as would enable them to cure their meats and make their sausage so as not to incur losses from goods that would not keep, and to turn out goods of fine quality and appearance.”

“The enactment of the National Pure Food Law, the National Meat Inspection Law and the various State Pure Food Laws had made a great change in the Butcher, Packing and Sausage Making Business,” Heller noted in the introduction to the 1908 edition of Secrets of Meat Curing. “The firm of B. Heller & Co. anticipated the enactment of these laws, and already had completed investigations which enabled them to assist packers, butchers and sausage makers at once by giving them curing agents which were free from the Antiseptic Preservatives which these laws prohibited, and yet would produce cured meats, sausage, etc., of the highest quality without the use of the Antiseptic Agents. The underlying principles of handling meats and making sausage with the antiseptic agents and without them are very different, and it became absolutely necessary that the firm of B. Heller & Co. should furnish their friends and customers such information as would enable them to cure their meats and make their sausage so as not to incur losses from goods that would not keep, and to turn out goods of fine quality and appearance.”

It was a marketing pivot for the ages—an impressive bit of spin that actually made Heller’s services MORE in demand after the pure food laws than they were before.

As part of the same strategy, Ben Heller cut ties with many of the independent regional salesmen, or “jobbers,” who’d previously represented his business. Instead, he sought to build a team consisting entirely of his own men—meticulously trained to promote Heller products with true expertise and minimized self interest. In turn, in order to afford this sort of national sales force, the Heller line of products was dramatically expanded, with particular breakthroughs in sanitary cleaning products, ice cream and baking goods, and insecticides.

The latter department was led by a man named Frank Austin Martin, who was hired away from a competitor in 1903, and brought a particular understanding of bug-killing chemicals to the table. Since butchers were already keenly interested in eliminating pests, cross-promotions to established clients created a good launching point for Heller insecticides.

By 1910, the Heller stockroom on Jefferson Street was being pushed to its limits, stacked with a massive range of products all decorated with their own labels straight from the company’s overworked art department.

There was the new meat curing preparation “Freeze-Em Pickle,” the binder and absorbent “Bull Meat Brand Flour,” “Improved Zanzibar Carbon” (now with vegetable coloring permitted by the government), “Vacuum Brand Garlic,” “OZO Washing Compound,” “Konservirungs-Salt,” “Tanaline” for tanning skins, “Royal Metal Polish,” and the pest killers “Rat Bane” and “Ant Bane”—promoted as a “pleasant suicide” for the two creatures.

There was the new meat curing preparation “Freeze-Em Pickle,” the binder and absorbent “Bull Meat Brand Flour,” “Improved Zanzibar Carbon” (now with vegetable coloring permitted by the government), “Vacuum Brand Garlic,” “OZO Washing Compound,” “Konservirungs-Salt,” “Tanaline” for tanning skins, “Royal Metal Polish,” and the pest killers “Rat Bane” and “Ant Bane”—promoted as a “pleasant suicide” for the two creatures.

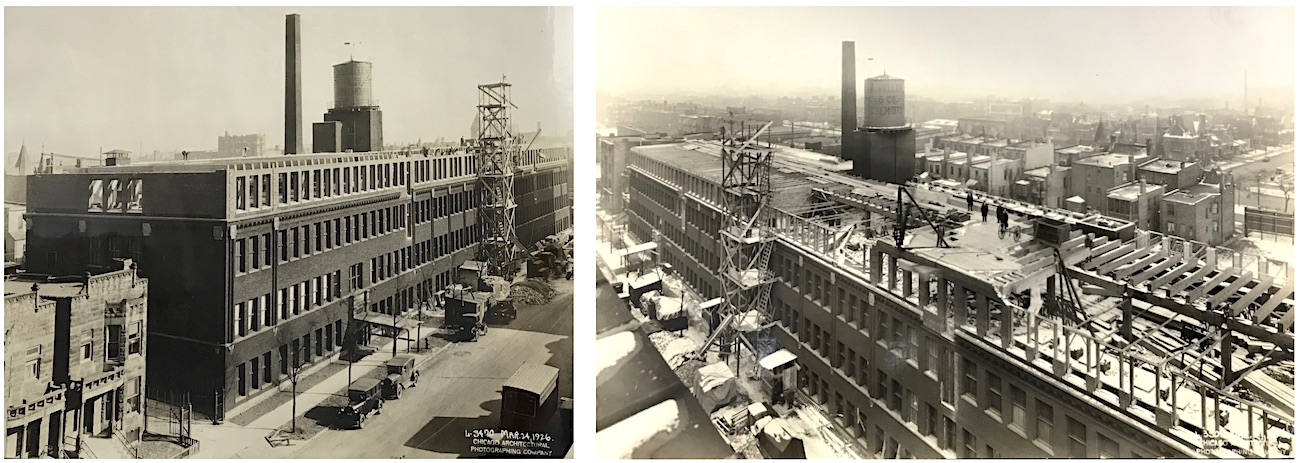

It was clear that a larger headquarters was needed, and while office manager Albert Heller suggested building a new plant on a developing section of downtown now known as Streeterville, Benjamin overruled, selecting a property at Calumet Avenue and 40th Street in Bronzeville. This new facility, opened in 1912, would remain Heller’s home base—for better or worse—for the next 66 years.

[The Heller factory at 3925 Calumet Avenue in Bronzeville, as seen in its original 1912 construction (above) and in the process of expanding from 3 stories to 5 stories in 1926]

[The Heller factory at 3925 Calumet Avenue in Bronzeville, as seen in its original 1912 construction (above) and in the process of expanding from 3 stories to 5 stories in 1926]

IV. Calumet Avenue and the Chicago Insecticide Laboratory

The original Calumet Avenue plant stood three stories, with 75,000 square feet of space for Heller’s offices, publishing press, machining, warehousing, and chemical labs. One segment of those labs—the one concerned with critter death—got its own subsidiary designation as the Chicago Insecticide Laboratory, as seen on the Moth Killer can in our museum collection.

The Heller brothers also had large mills installed for grinding peppers, sage, cloves, and other herbs and spices, which were then mixed into seasonings for butcher-prepared sausages.

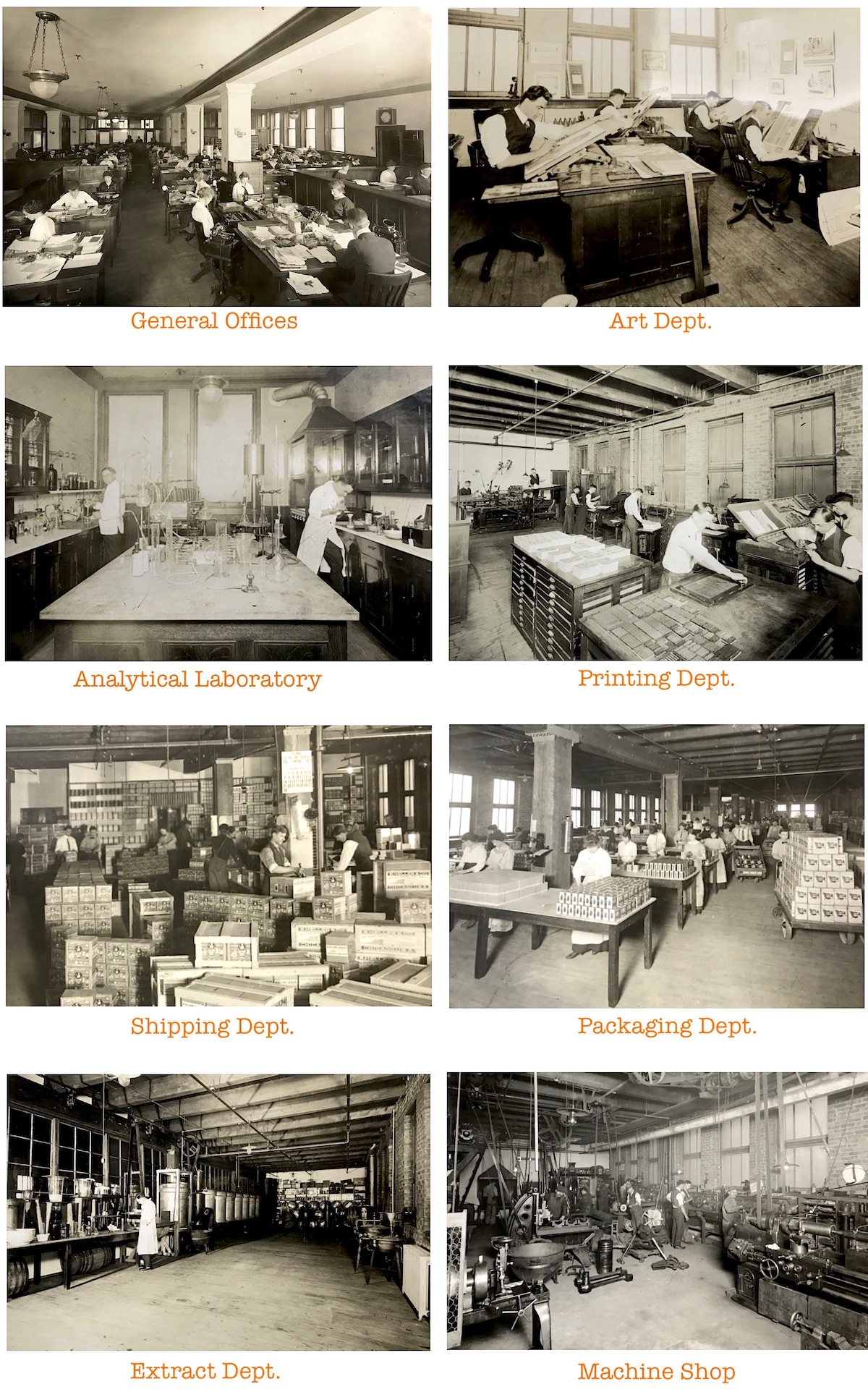

After World War I they added two more stories to the plant, expanding its capacity to 135,000 square feet, largely with the goal of breaking into the consumer market for the first time. The photos below show various areas of the factory and many of its roughly 200 employees, as they looked in the mid 1920s.

Inside the B. Heller & Company Factory, circa 1926

As the photos would indicate, Heller had a largely white workforce in the 1920s, but as the surrounding neighborhood of Bronzeville continued to emerge as the epicenter of African-American culture in the city, the company began to reflect its community more accurately. Black workers weren’t just hired for the warehouse and manufacturing positions, either—Heller, to its credit, took some progressive strides for its day, giving key laboratory jobs to accomplished African-American chemists like Thomas B. Mayo and J. L. Morgan—who were also proud delegates of the National Association of Colored Engineers and Architects in the 1930s. Mayo would eventually ascend to the role of Chief Chemist with Heller in the ’40s, before leaving to start his own chemical manufacturing firm, the M&W MFG Co., in 1950.

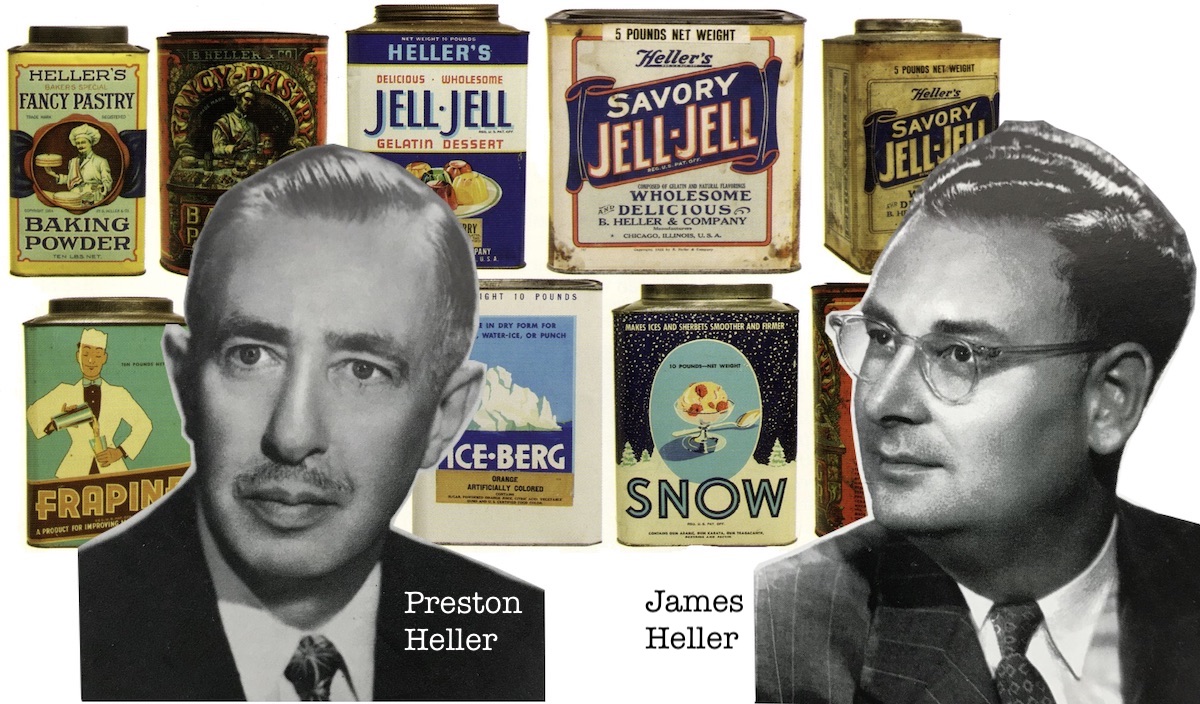

Thomas Mayo spent most of his years with B. Heller & Co. working not under B. Heller himself, but the second generation of the family—Benjamin’s son Preston Heller (1902-1954) and Albert’s kid James Heller (1916-1995)—both of whom took on critical roles in the day-to-day running of the business after Ben Heller’s death in 1933.

James, who came aboard as a teenager shortly after the stock market crash of ‘29, had the unenviable task of being the company’s primary bill collector in the midst of the Depression. His older cousin Preston, meanwhile—being Benjamin’s son and next-in-line to the “throne”—had already been working at the Calumet Avenue offices since 1923, spending much of his time making sure Heller products were still adhering to every new government safety policy; including the long overdue inclusion of ingredients on labels after 1927.

Total transparency was never a principle that B. Heller & Co. generally subscribed to voluntarily. Dating way back to the original Zanzibar Carbon, Ben Heller felt that revealing the inner workings of his business would not only generate skepticism and criticism from the scientific community, but also potential theft and copycatism from would-be competitors in the trade. His son Preston seemed to feel much the same in 1934, when he testified before the U.S. Senate Committee on Education & Labor, condemning the “sneaky” labor union organizers who were getting unauthorized access to his Chicago factory.

“Because of the secretive nature of our formulae and processes,” he explained, “we have adopted a rigid rule excluding everyone—even our own salesmen and customers—from our plant.”

Preston Heller’s testimony—given when he was still just 32 years old— came at a very tumultuous time in the company’s history. Not only had his father just died the year prior, but profits were plummeting as the country slogged through Year 5 of the Depression. Impressively, the factory had managed to keep just about all of its 200-person workforce on the books, but CEO Albert Heller was forced to cut their wages by 10% and end production of the long-running company magazine, Success With Meat. All hopes of breaking into the consumer market were abandoned, as well, as the necessary production and sales force couldn’t be maintained. Perhaps the biggest threat the company perceived to its sustainability, though, was the proposed National Labor Relations Act, aka the “Wagner Act”—which would greatly improve negotiating rights for trade unions. Many conservatives at the time felt the Wagner Act would doom small businesses across the country once and for all, which is why Preston Heller headed to D.C. to state his company’s strong opposition to the legislation.

Preston Heller’s testimony—given when he was still just 32 years old— came at a very tumultuous time in the company’s history. Not only had his father just died the year prior, but profits were plummeting as the country slogged through Year 5 of the Depression. Impressively, the factory had managed to keep just about all of its 200-person workforce on the books, but CEO Albert Heller was forced to cut their wages by 10% and end production of the long-running company magazine, Success With Meat. All hopes of breaking into the consumer market were abandoned, as well, as the necessary production and sales force couldn’t be maintained. Perhaps the biggest threat the company perceived to its sustainability, though, was the proposed National Labor Relations Act, aka the “Wagner Act”—which would greatly improve negotiating rights for trade unions. Many conservatives at the time felt the Wagner Act would doom small businesses across the country once and for all, which is why Preston Heller headed to D.C. to state his company’s strong opposition to the legislation.

As he and his uncle Albert saw it, giving unions more power would undermine all the good things that small businesses were already doing for their employees. In the 40-year history of B. Heller & Co., Preston claimed, “we never had a labor dispute, either with our own people or with outside organizers . . . Every man and woman in our employ knew he or she had always received a square deal, and could talk to us about wages or any other problem at any time. They had no desire to be dominated by a union which would cost them heavily for dues, and possibly call them out on strike because some other institution might be having a dispute.

“Our concern functions like a team,” he continued. “We pull together, not in two diverging, selfish directions.”

Unfortunately, and unsurprisingly, none of Heller’s employees were invited to testify on their own behalf. The National Labor Relations Act passed and became law in 1935 anyway, and while it may not have made life easier for the Heller family, the business did manage to carry on.

V. Heller Seasonings & Ingredients, Inc.

From the mid 1930s through to the last months of World War II, B. Heller & Co. was guided mainly by an outsider, A. J. Campbell, who took the reins entirely when Albert Heller retired and the youngsters Preston and James were called to military duty. Campbell brought stability to the business at the end of the Depression and made the best of another difficult situation during the war, when rationing not only limited the company’s access to spices and other ingredients, but also cut into the salesmen’s ability to get enough gas in their cars to drive from one city to the next.

When Campbell died suddenly in 1945, Preston and James returned from their service to find the entire landscape of their industry changed yet again. Increasing competition in peacetime was one obstacle, as anticipated, but new technology born from wartime innovation was also causing some quakes.

Heller’s laundry “bluing” products, for example—a small but significant part of the business for decades—was rendered obsolete by new, better methods. The insecticide industry was radically evolving, too, and Heller’s labs couldn’t compete making the industrial strength military bug bombs and aerosol cans that larger manufacturers were now bringing to consumers. The Chicago Insecticide Laboratory, incidentally, had already ceased to exist during the Depression, and by the 1960s, most of Heller’s remaining insecticide lines were gradually discontinued.

Heller’s laundry “bluing” products, for example—a small but significant part of the business for decades—was rendered obsolete by new, better methods. The insecticide industry was radically evolving, too, and Heller’s labs couldn’t compete making the industrial strength military bug bombs and aerosol cans that larger manufacturers were now bringing to consumers. The Chicago Insecticide Laboratory, incidentally, had already ceased to exist during the Depression, and by the 1960s, most of Heller’s remaining insecticide lines were gradually discontinued.

Much like Benjamin Heller back in 1893, Preston and James Heller were wise enough to understand that nothing would change for the business unless the business changed entirely. Toward that end, they recruited respected management engineer Norman Schreiber from the Elgin Watch Company, and let him lead a new campaign to tighten up the ship and redefine the Heller brand based on its strengths.

In the ‘50s, Heller & Co. got back to its roots in some respects, focusing on seasonings and supplies for small and mid-size meat processors. But they also jumped more aggressively into the consulting game, turning their “seasoned” experts and respected salesmen into agents—offering that wisdom as an asset unto itself. One such specialist in the Chicago region, Charlie Deitchel, joined Heller in 1951 and supposedly helped quadruple the company’s revenue in the local market over the next 20 years. Despite the consolidation in products in the ‘50s, there were still over 200 men and women on the company payroll, showing the business’s steady consistency, if not earth-shattering growth.

By 1960, Norman Schreiber had departed the business, and Albert Heller and Preston Heller had both departed this mortal coil—the latter at the young age of 52. This left James Heller as company chairman, a position he would hold for 30 years.

By 1960, Norman Schreiber had departed the business, and Albert Heller and Preston Heller had both departed this mortal coil—the latter at the young age of 52. This left James Heller as company chairman, a position he would hold for 30 years.

Under James’s watch, Heller & Co. started developing partnerships with larger producers like Johnsonville Brats; took a controlling interest in another meat producer, J. A. Jenks Co.; and opened up its first west coast facility in Pleasanton, California. The company also finally said farewell to its dilapidated building in Bronzeville, which—being in a neighborhood that had turned rough—didn’t even have value as a teardown property. A few fires in the 1980s eventually did it in.

With James’s son John Heller now on a team that included president Hugo Wistreich and VP John Hornor, the company moved in 1978 to a new spacious facility at 6363 W. 73rd Street in Bedford Park. Five years later, the business was officially renamed Heller Seasonings and Ingredients, Inc., and in 1984, a 69 year-old James Heller handed off the chairmanship to his 34 year-old son.

[Former Heller Seasonings plant at 6363 W. 73rd Street, just south of Midway Airport]

[Former Heller Seasonings plant at 6363 W. 73rd Street, just south of Midway Airport]

“We’re in the business of helping food processors of all kinds make their products look, taste and smell better,” John Heller said in 1992, summarizing the company mission statement as it approached its 100th anniversary. As noted in the company’s centennial anniversary book, Well Seasoned, that description just as easily could have been uttered by Benjamin Heller himself way back in 1894.

In the same book, 77 year-old James Heller was asked for his vision of Heller Seasonings heading into the future. “I think John and I agree that success in the next hundred years will depend on continuing to meet the needs of our customers,” he said, “so that our counterparts in 2093 can look back with satisfaction on Heller’s second century.”

That next centennial, sad to say, will not be forthcoming. James Heller died in 1995, and in 2003, a Chicago competitor called Newly Weds Foods acquired Heller Seasonings, seemingly absorbing its life force. The Bedford Park plant has since closed and—as best we can tell—the Heller name is no longer in use within the industry. The “$1,000 Guarantee,” one must also presume, has officially expired.

Sources:

Well Seasoned: A Centennial History of Heller Seasonings & Ingredients, Inc., by Terry Fife and Jay Pridmore, 1992

“Adulteration of Food Products” – Industrial Commission in Accordance with the Resolution of the Senate, December 6, 1900

“Formaldehyde and Milk” – Journal of the American Medical Association, June 9, 1900

“The 19th-Century Fight Against Bacteria-Ridden Milk Preserved With Embalming Fluid” – by Deborah Blum, Smithsonian Magazine, Oct 5, 2018

“Zanzibar Carbon” – The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, 1900

Heller’s Guide for Ice Cream Makers, 6th edition, 1918

“Benj. Heller, Chemical Manufacturer, 64, Buried” – Chicago Tribune, May 27, 1933

“To Create a National Labor Board” – Hearings Before the Committee On Education and Labor, U. S. Senate, 1934

Secrets of Meat Curing and Sausage Making, 1908, 1918

“Preston B. Heller” (obit) – Chicago Tribune, Jan 8, 1954

“Thomas B. Mayo” (obit) – Chicago Tribune, March 9, 1966

“Benjamin Heller” – Encyclopedia of Bohemian and Czech-American Biography, Vol. 1

“Killer Collectibles” by May Berenbaum, American Entomologist, Winter 2001

“B. Heller & Co.” – Past Times (Antique Advertising Association of America), Vol 10, No. 4, 2001

“James R. Heller” (obit) – Chicago Tribune, Feb 12, 1995

I have a 200 lbs barrel that was used to hold Zanzibar brand pure cocoa. It is in good shape and has all labels. Where can I sell it at?

I have seen all of these products at the home of Mr James Heller summer home my father used to caretake for Mr Albert Heller back in the fortys I have heard a lot of great stories about the Heller family first hand = great family !! I also have had the great pleasure to have known Mr James and his wife Beth Heller Many times in northern wi , great history!!

What is equivalent to Hellers sausage seasoning today?

I am the granddaughter of Benjamin Heller. Benita was my mother and Preston was her brother. My husband Herbert A Loeb lll and I use to go to lots of antique shows and collect a variety of vintage advertising and containers from different company’s. I still have many B Heller & Co containers that we found over the years of collecting antiques and a large variety of beautiful and colorful unused labels that I acquired from the family and framed. I am will to part with some of these things, if anybody would like to add to there own advertising collections. Here is my email address:halsll@comcast.net. Please fell free to contact me with any questions you might have. Sally

Interesting! Now I know the facts of my 1000$ dollar guarantee bedbug killer!

I have a $ 1,000 guarantee can of Ant Killer never been open. I am now taking all offers who want to buy it.

I have a can of 1000.oo guaranteed roach killer never opened anyone interested?

where can I get Zanza Bar salami seasoning, in a 1 pound package ? I have used Heller products for many years,.

Tengo dos botellas de freezine cerradas y en perfecto estado, son del 1901. Las vendo escucho ofertas