Museum Artifact: McLaughlin’s Imperial Mocha & Java Coffee Tin, c. 1900s, + 19 McLaughlin XXXX Coffee Trade Cards, 1890s

Made By: W. F. McLaughlin & Co., State Street and South Water Street., Chicago, IL [River North]

“Tastes Good—Always. You get the extra good quality in this coffee because it is imported direct and sold direct to retail dealers by W. F. McLaughlin & Co., the largest exclusive coffee roasters in the world.” —advertisement for McLaughlin’s XXXX Coffee, 1906

When the National Dairy Products Corporation purchased all the assets of Chicago’s W. F. McLaughlin & Company in 1967, it marked the end of one of America’s last great independent coffee dealers. At that point, the century-old, family-owned McLaughlin business and its flagship “Manor House” brand had already shrunk to a regional four-state market in the Midwest, where it was still rapidly losing ground—and grounds—to longtime grocery aisle rivals Maxwell House (owned by General Foods) and Folgers (owned by Procter and Gamble). In the new age of the super-conglomerate, there was simply no chance of getting by on reputation alone.

When the National Dairy Products Corporation purchased all the assets of Chicago’s W. F. McLaughlin & Company in 1967, it marked the end of one of America’s last great independent coffee dealers. At that point, the century-old, family-owned McLaughlin business and its flagship “Manor House” brand had already shrunk to a regional four-state market in the Midwest, where it was still rapidly losing ground—and grounds—to longtime grocery aisle rivals Maxwell House (owned by General Foods) and Folgers (owned by Procter and Gamble). In the new age of the super-conglomerate, there was simply no chance of getting by on reputation alone.

That being said, if you think the story of the McLaughlins is merely that of the rise and fall of a coffee company, you’d be sorely mistaken. Coffee, in some ways, barely even amounts to a literal or proverbial hill of beans with this family.

While most of the old Chicago businesses we discuss in this museum have a “back-story,” W.F. McLaughlin & Co. has more of a dark romantic saga—like a Hemingway novel adapted into a Scorsese movie. It’s got everything you could want in a modern American folktale: an Irish immigrant with a dream, a great fire, betrayal and power grabs, 1920s urban playboys, ballroom dancing, hockey fights, car crashes, fuzzy animals, romance on the high seas, swashbuckling . . . Okay, maybe not swashbuckling, but nothing else there was hyperbole.

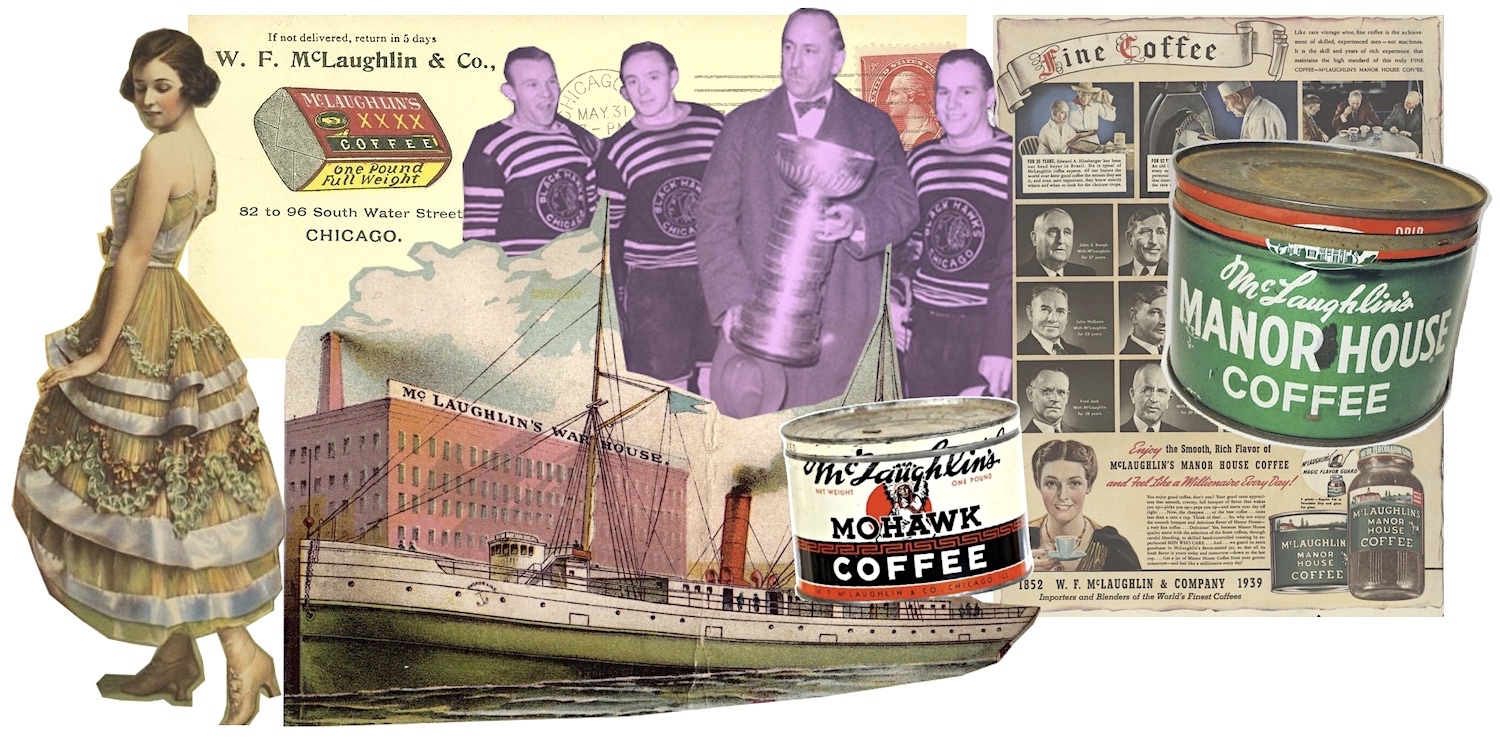

[Scenes from the McLaughlin saga]

History of W. F. McLaughlin & Co., Part I: An Irishman and a Wheelbarrow

Fortunately, to help bring the technicolor McLaughlin tale into focus, the Made in Chicago Museum is grateful to have the assistance of a uniquely qualified expert.

Dr. Castle McLaughlin is not only a noted author of American history and a museum curator at Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, she’s also the great-granddaughter of William F. McLaughlin (founder of McLaughlin & Co.), granddaughter of Frederic McLaughlin (founder of the Chicago Blackhawks NHL franchise), and daughter to William Foote McLaughlin—a man who dedicated countless hours to preserving the history of his family’s business long after National Dairy / Kraft Foods had tossed out most of the original documents pertaining to it.

“The larger company, W.F. McLaughlin and Co., was generally known to the public as McLaughlin’s Manor House Coffee,” Dr. McLaughlin explains. “William Francis McLaughlin [b. 1827] came from Cloneybacon House in county Laois, Ireland, and that inspired the brand name. He was from a well-to-do family and a college graduate, but started from the bottom in Chicago, first selling coffee beans from a wheelbarrow and then a wagon. He eventually owned several mansions on Rush Street and the family had several estates in Lake Forest. His children all lived in Lake Forest, which is where my father was born.”

“The larger company, W.F. McLaughlin and Co., was generally known to the public as McLaughlin’s Manor House Coffee,” Dr. McLaughlin explains. “William Francis McLaughlin [b. 1827] came from Cloneybacon House in county Laois, Ireland, and that inspired the brand name. He was from a well-to-do family and a college graduate, but started from the bottom in Chicago, first selling coffee beans from a wheelbarrow and then a wagon. He eventually owned several mansions on Rush Street and the family had several estates in Lake Forest. His children all lived in Lake Forest, which is where my father was born.”

From the looks of it, the Irish origins of the “Manor House” name never quite settled into common knowledge. In a 1952 Chicago Tribune article covering the 100th anniversary of McLaughlin’s coffee, the oldest living employee of the company, 80 year-old E.B. Blair, was asked if he knew where the name came from. Blair, who’d worked alongside W.F. McLaughlin himself in the 1890s, didn’t have a clue. Or maybe, just possibly, it had slipped his mind.

So how exactly did William F. McLaughlin go from the bean wagon to the penthouse in his adopted homeland? Well, the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 destroyed just about all the records from the early days of his business, making even the official establishment date of 1852 more of a loose approximation. But we do know that, dating back at least to the 1860s, McLaughlin ran a store on South Water Street with a business partner, Richard B. Woolford, in which they specialized in teas, coffees, spices, and other wholesale goods. You can find one mention of the business in the November 1, 1869 edition of the Tribune, reporting a small fire that broke out “at the coffee and spice store of McLaughlin & Woolford, No. 119 South Water Street. A lot of peas that were being roasted got too hot and burned. Beyond the loss of peas, there was no damage. The cry was ‘peas, peas! And there was no peas.'” And yes, that’s an intentional comedic pun and a biblical reference . . . the best of Victorian humor.

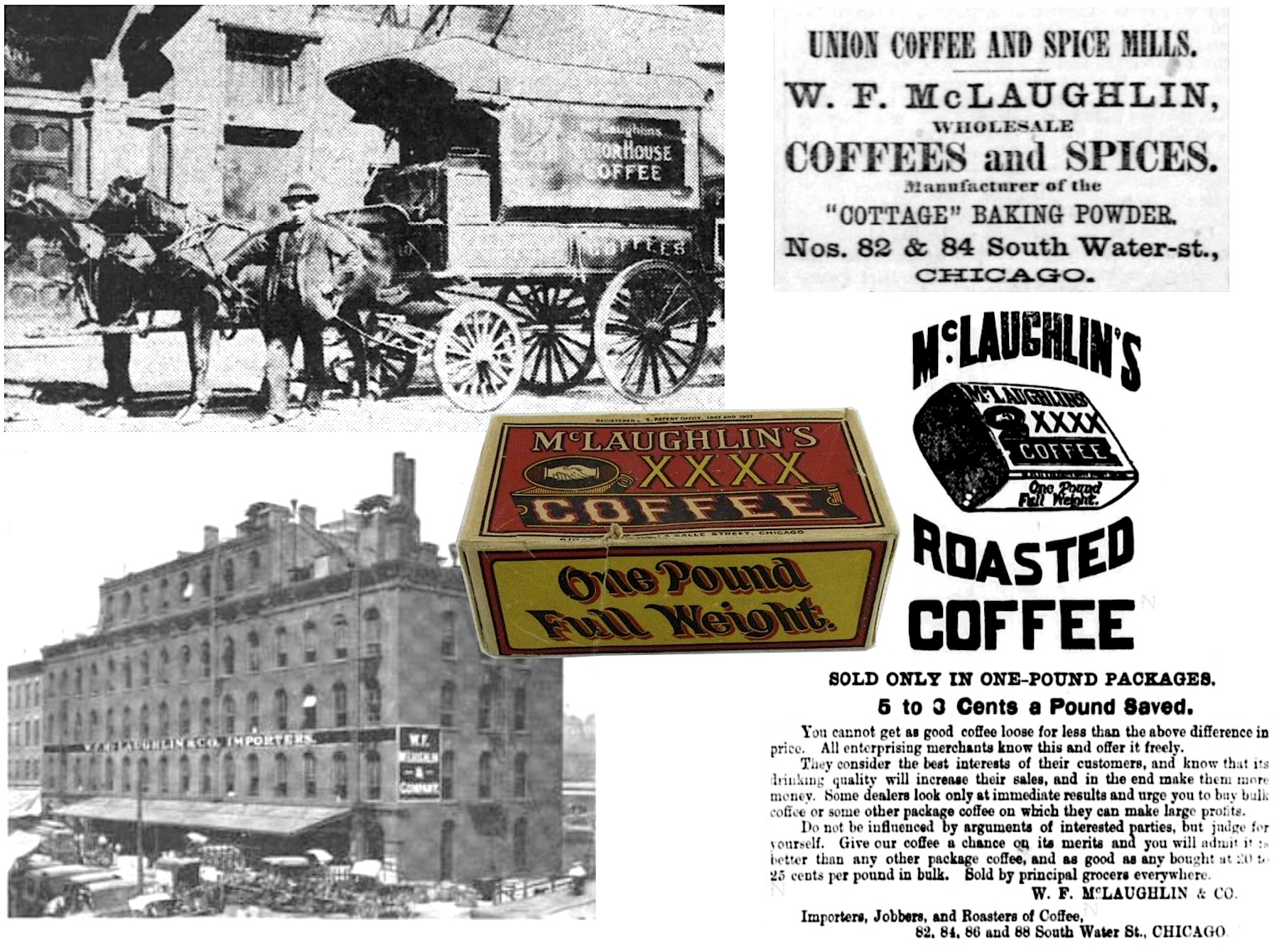

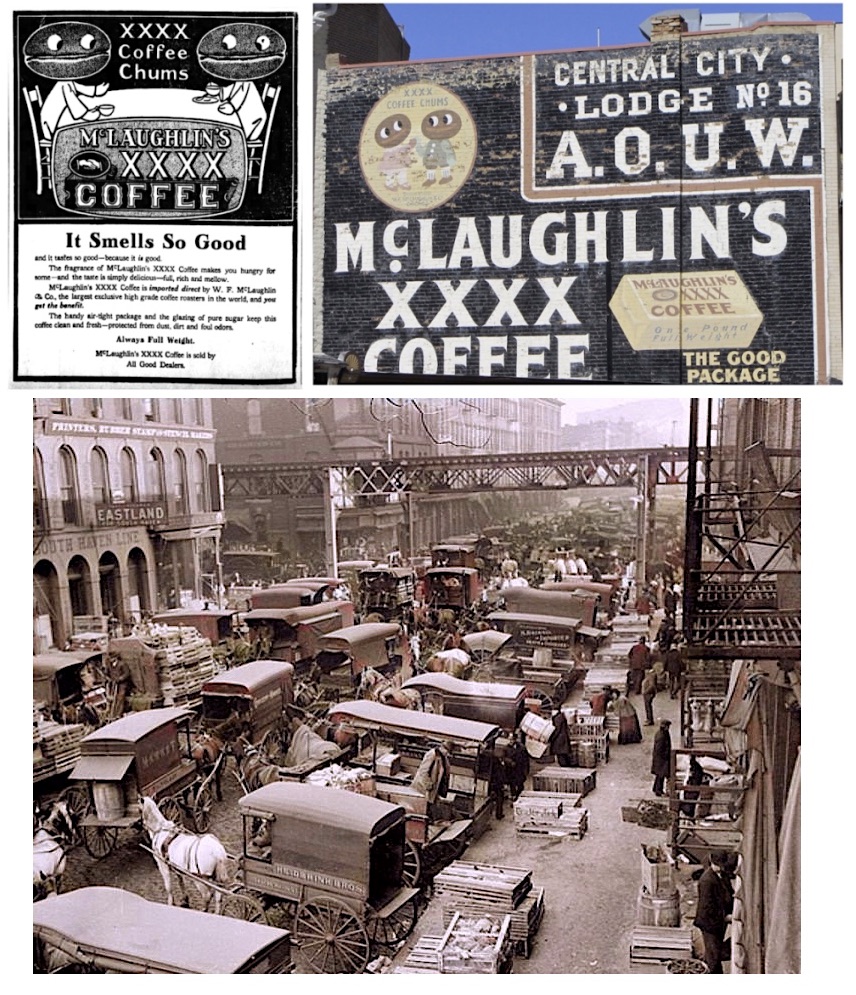

[Top left: McLaughlin delivery wagon, c. 1890s. Top Right: McLaughlin ad from 1877. Bottom Left: The McLaughlin building at 82-96 South Water Street, c. 1900. Bottom Right: XXXX Coffee ad from 1887]

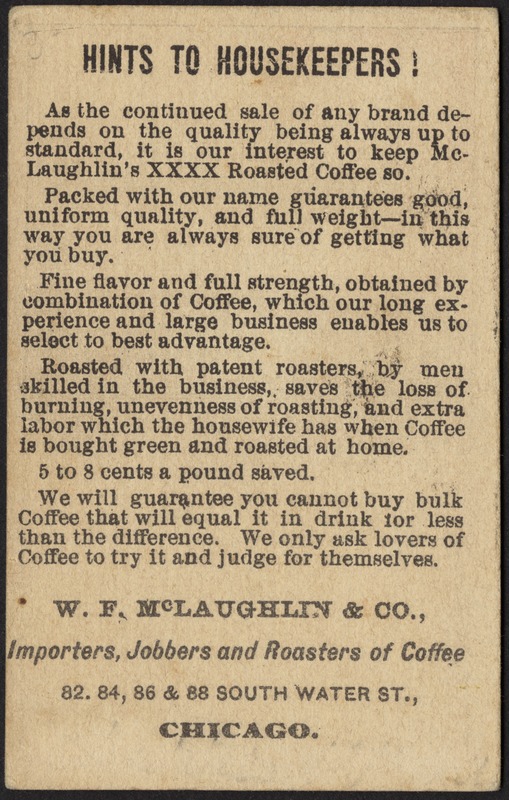

McLaughlin parted ways with Woolford just before the Great Fire and ultimately rebuilt afterwards as W. F. McLaughlin & Co., located at 82-84 South Water Street. The firm’s big breakthrough didn’t really come until around 1881, however, when it introduced its “XXXX” brand of pre-roasted coffee. While virtually all of his competitors were selling raw or green coffee beans in bulk for customers to roast in their own ovens, McLaughlin realized he could stand out by roasting and packing the beans prior to distribution. The only other company that jumped on this concept early on, Arbuckles, became the only coffeemakers to outsell McLaughlin in the years ahead.

The use of the four X’s in the brand name, incidentally, didn’t represent a placeholder, a curse word, or four kisses. Most likely, it was a concept borrowed from an old brewing tradition, in which a number of X’s, from 1 to 4, indicated the relative strength and/or quality of an ale.

According to Castle McLaughlin, once XXXX Coffee became popular with grocers and their customers locally, its larger success “was really predicated on the expansion of markets made possible by the transcontinental railroad. In the late 19th century, the company also owned several coffee plantations in South America, which gave them a direct route to the marketplace. . . . At one time the company was the 2nd largest in the U.S., next to Arbuckles.“

According to Castle McLaughlin, once XXXX Coffee became popular with grocers and their customers locally, its larger success “was really predicated on the expansion of markets made possible by the transcontinental railroad. In the late 19th century, the company also owned several coffee plantations in South America, which gave them a direct route to the marketplace. . . . At one time the company was the 2nd largest in the U.S., next to Arbuckles.“

Indeed, while they proudly marketed XXXX as the “Best Coffee on Earth,” McLaughlin really got ahead by selling its product for a cheaper price than the competition, made possible by establishing its own plantations in the Brazilian cities of Santos and Rio de Janeiro.

“We buy all our XXXX Coffee from the coffee planters direct,” read a company trade card from 1892, “thereby saving the importers, jobbers and commission men’s profits. We give all this saving to the consumer, and say without any fear of contradiction that we are putting up coffee from 5 to 10 cents a pound finer quality than any other package or loose coffee on the market. The immense success of XXXX Coffee proves that our policy of giving the consumer the cheapest coffee for the money and selling an immense quantity, is the best.”

As mentioned, the words above were originally printed on the back of a collectable picture card; an example of McLaughlin & Company’s use of advertising “premiums.” These were essentially bonus gifts that either came with a package of XXXX Coffee, or could be acquired by mailing in pieces of McLaughlin wrappers as a proof of purchase.

Enticing customers with premiums was a pretty common practice of the late Victorian period (Wrigley chewing gum famously began as a premium product tossed in with William Wrigley’s soap), but McLaughlin was particularly aggressive in this area. The company offered many dozens of different prizes to loyal XXXX drinkers; higher-end premiums like silverware and pocketbooks required a large collection of wrappers to collect on, but promotional items like trade cards were easier to get, and did the extra service of advertising the company. McLaughlin’s cards of the 1880s and ’90s—of which we have a small collection in our museum—were produced in vast quantities, and usually featured either images of adorable children, scenes from “exotic” locations around the world, or a sometimes racially insensitive combination of the two. Most of our collection was kindly donated by a patron named Ladema Gore, whose grandmother had originally owned them.

McLaughlin Trade Cards, c. 1885-1895, from our Museum Collection

Click Below to See More

Interestingly, despite producing trade cards celebrating the innocence of childhood, W. F. McLaughlin was not above the trends of the day in terms of employing child labor. In the late 1890s, they were actually adding to their underaged workforce rather than reducing it. Of the 310 people employed at the Chicago warehouse in 1895, a Factory Inspector’s report noted that 107 were children; up from 87 the previous year. “At McLaughlin’s coffee factory,” the report added, “whenever any order requires it, boys pack coffee until 10 or 11 o’clock at night.” That’s not even making any count, of course, of the ages or hours clocked by the people the company had on the payroll in Brazil.

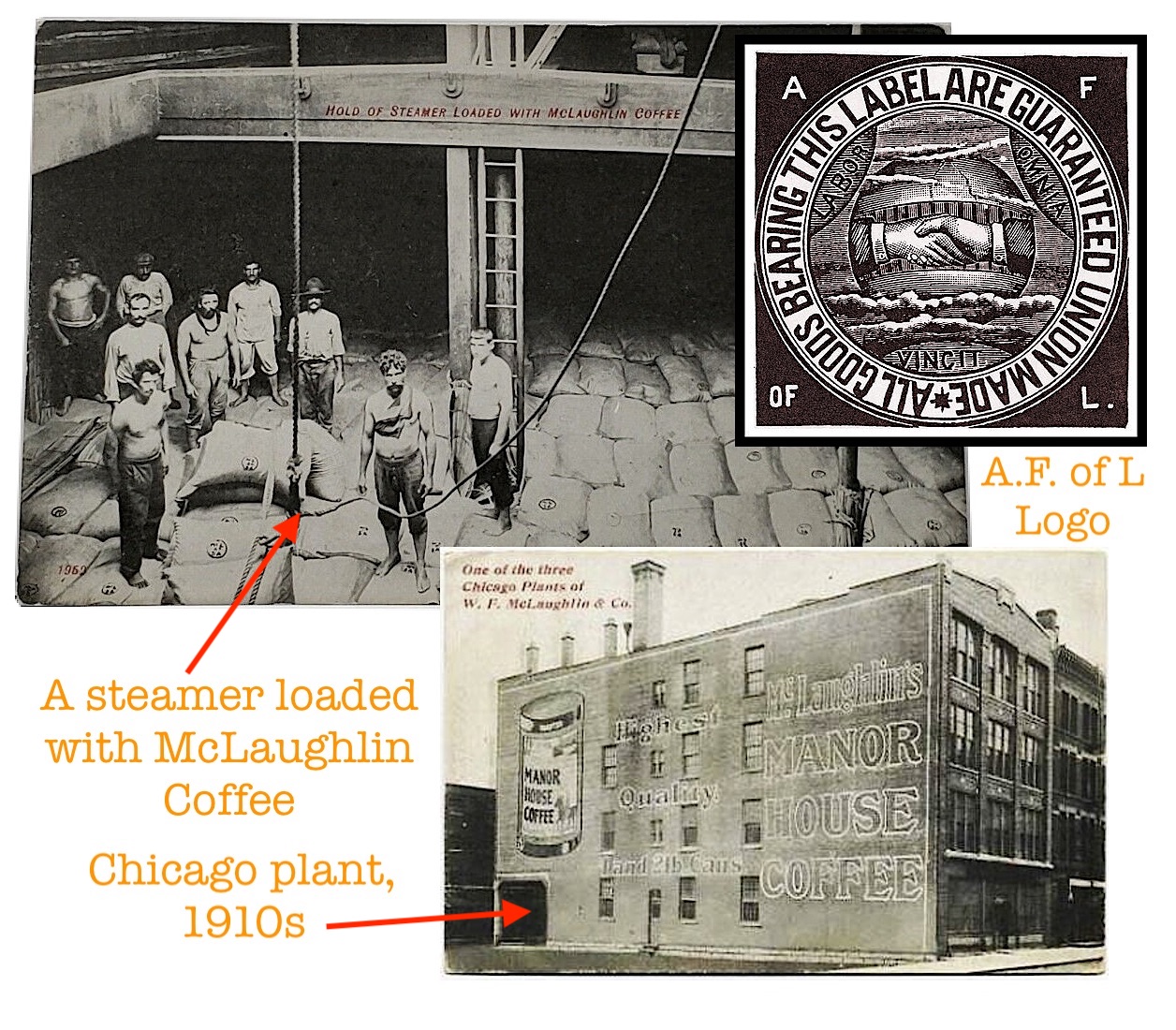

As late as 1903, McLaughlin still had over 40 kids under the age of 16 working at the Chicago plant, but oddly enough, there were simultaneous indications that the company was actually on the progressive side when it came to other labor issues. As an example, when the upstart United Coffee Roasters and Helpers Union was formed under the banner of the American Federation of Labor in 1903, the new organization demanded that all coffee wholesalers establish a firm nine-hour workday, hire only union workers, and start putting the A. F. of L. label on their products. Apparently, W. F. McLaughlin was the one and only such business to accept these terms, earning the firm some street cred among turn-of-the-century unionists.

“There is no better coffee grown than that roasted by McLaughlin & Co.,” a Kansas newspaper called The Labor Champion announced that year, “and it is the business of organized labor everywhere to buy their product, and to turn down emphatically the product from firms that will not recognize the union label.”

“There is no better coffee grown than that roasted by McLaughlin & Co.,” a Kansas newspaper called The Labor Champion announced that year, “and it is the business of organized labor everywhere to buy their product, and to turn down emphatically the product from firms that will not recognize the union label.”

It’s possible that George D. McLaughlin (b. 1864)—William’s eldest son—was responsible for this pro-union stance. He had already largely stepped into his father’s shoes, and after William’s death from pneumonia in 1905, the family business was officially George’s to lead.

There were plenty of reasons for optimism, too. In the 1910s, McLaughlin’s Coffee had as many as three separate plants in Chicago, with the main hub still on South Water Street. There, new goods were brought in via the river, packaged inside the factory (sometimes into beautiful green tins like the “Imperial Mocha & Java” in our collection), then brought out the other side to the South Water Street market, where closely packed horse-drawn wagons and early automobiles created a chaotic combination of noises and smells. As Castle McLaughlin tells us, however, this era was quickly nearing its end. With the onset of World War I, McLaughlin’s valuable South American properties were suddenly closed off, putting them more on an even footing with everyone else, if not at a disadvantage. “After that,” Dr. McLaughlin says, “the company concentrated on the regional market rather than competing nationally.”

[Top Left: McLaughlin’s ad from 1906 featuring mascots known as the “XXXX Coffee Chums.” Top Right: A surviving ghost sign on the side of a building in Central City, Colorado, photographed in 2012 by Patricia Henschen. Bottom: A typical day on Chicago’s South Water Street market, 1910s]

II. Fred & Irene

Just months after the end of WWI, in 1919, McLaughlin & Co. consolidated its operations and moved into an eight-story plant at 610-620 N. LaSalle Street in River North (former home of the Chicago Flexible Shaft Co.), where a couple hundred employees handled the roasting, processing, packing, and taste-testing of the company’s dozen or more different coffee brands. This same building was later converted into a Mages Sporting Goods mega-store, which in turn became a Sports Authority storefront until its closure in 2016.

Part of the new Manor House management team was George McLaughlin’s little brother Frederic (b. 1877), who was back from serving in the war and ready again to serve as secretary-treasurer of the company. At 42, Fred was no spring chicken, but he certainly had a certain reputation around town.

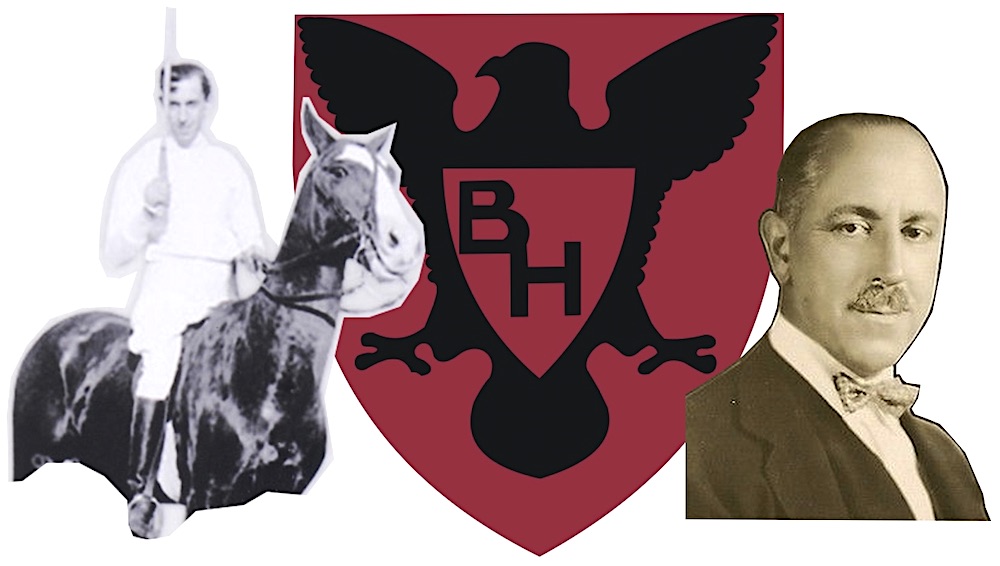

“Frederic was the youngest of eight surviving children,” Castle McLaughlin says of her grandfather, “and he was considered one of the most eligible bachelors in Chicago. He was primarily known as a crack polo player, and was captain of the national polo team at the Panama Expo in 1915. [In the early 1920s], he had a famous bachelor apartment in the old brick coffee company warehouse along the river—the building is still standing. It apparently had 25-foot ceilings and windows with velvet curtains. During a family reunion in 2011, we took one of those architectural boat tours and the guide pointed out the building so it is still known and remembered.”

Along with being a polo-playing playboy, Frederic McLaughlin was also a Harvard graduate and a respected military man. He’d earned the rank of Major while serving with the 86th Infantry “Black Hawk” Division in the 333rd Machine Gun Battalion. Longtime Chicagoans and/or fans of professional ice hockey will no doubt guess why this winds up being significant.

[From left: Frederic McLaughlin in polo mode, early 1900s; logo of the 86th Infantry “Black Hawk” division from World War I; Frederic McLaughlin in the 1920s]

In June of 1926, Frederic—who knew about as much about hockey as a hockey player knows about polo—decided to put his ample funds and free time toward the purchase of a new expansion franchise in the National Hockey League. He dubbed the club the Chicago Blackhawks in honor of his old military unit.

From the beginning, McLaughlin was a hands-on team owner, constantly fidgeting with the club’s roster and hiring and firing coaches like a proto George Steinbrenner. He made a point of trying to sign American players over Canadians—putting patriotism above wisdom in some cases—and supposedly hired one of his coaches, Godfrey Matheson, solely because he had a good conversation with him on a train (Matheson was eventually fired after two games). The legendary Toronto Maple Leafs owner Conn Smythe (1895-1980) assessed Fred McLaughlin as such: “Where hockey was concerned, Major McLaughlin was the strangest bird and, yes, perhaps the biggest nut I met in my entire life.”

[Blackhawks owner / coffee mogul Frederic McLaughlin holds the Stanley Cup in 1934]

[Blackhawks owner / coffee mogul Frederic McLaughlin holds the Stanley Cup in 1934]

While he might not have been widely respected within the game, Frederic McLaughlin ultimately got results. The Blackhawks had their first winning season in 1929-30, and made it all the way to the Stanley Cup Finals in 1931, losing to the Montreal Canadiens. That same year, 67 year-old George McLaughlin was killed in a car crash caused by a drunk driver, abruptly putting his grieving brother Fred in charge of both the Hawks and the family coffee business . . . right at the start of the Great Depression, no less.

In many ways, Frederic did an admirable job keeping both enterprises on the right track. Chicago won its first two Stanley Cup titles in 1934 and 1938, and McLaughlin’s Manor House coffee remained a Midwestern staple, familiar even to non-joe drinkers thanks to radio program sponsorships, illuminated billboards, and full-page newspaper ads.

In one ad from 1940, a grinning husband turns to his wife after she pours him a cup. “I was sure lucky the day I married you,” he says, “this coffee beats anything I ever drink.” The ad copy continues from there: “To win praise like this from your husband, guests and friends, serve McLaughlin’s Manor House Coffee! Blended of choice coffees so rare we can supply it to only a limited market in and near Chicago! Roasted as only the McLaughlin craftsmen, with nearly a century of experience to guide them, know how! For keener coffee enjoyment every time, try McLaughlin’s Manor House Coffee now!”

In one ad from 1940, a grinning husband turns to his wife after she pours him a cup. “I was sure lucky the day I married you,” he says, “this coffee beats anything I ever drink.” The ad copy continues from there: “To win praise like this from your husband, guests and friends, serve McLaughlin’s Manor House Coffee! Blended of choice coffees so rare we can supply it to only a limited market in and near Chicago! Roasted as only the McLaughlin craftsmen, with nearly a century of experience to guide them, know how! For keener coffee enjoyment every time, try McLaughlin’s Manor House Coffee now!”

While McLaughlin ads were giving women tips on how to win their husband’s praise, Frederic McLaughlin’s own marriage was a far cry from this sort of quaint subservient dynamic. In fact, to many Chicagoans and people around the world, the most notable thing about Fred wasn’t Manor House Coffee or even the Chicago Blackhawks; it was his wife. After all, when you’re hitched to a celebrity and personality on the level of Irene Castle, it’s hard to cast your own shadow.

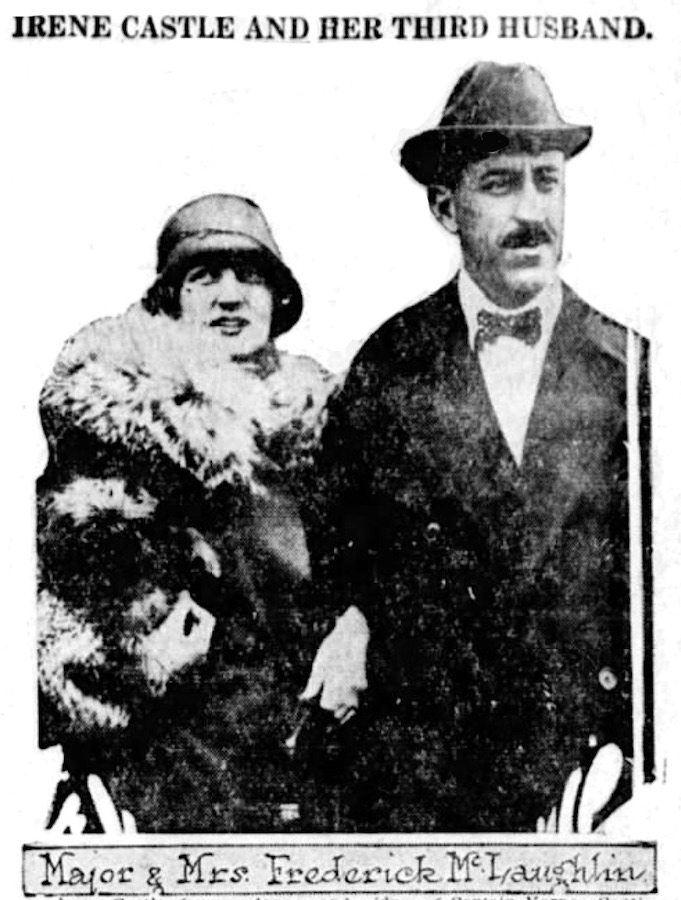

It was way back in 1923 that Frederic McLaughlin—once the happy bachelor wholesaler—made headlines by becoming the unlikely third husband of one of the world’s most renowned ballroom dancers and fashion icons; the pioneering flapper girl who personally popularized the bob hairdo and was routinely called “the best dressed woman in the world.” Now 30 years of age, Irene Castle (born Irene Foote in 1893) was 16 years Fred’s junior—but she was already more than a tad world-weary.

In her 1958 memoir Castles in the Air, Irene described the night she first met Frederic. She was performing in Chicago, and he had requested—through the appropriate rich people channels—that she attend a very intimate dinner party at his apartment.

“The chauffeured limousine called for us at the theater, and we drove a short distance to a two-story building facing the river on the Loop side of the bridge on Michigan Avenue. We went up a long flight of stairs into the most beautiful bachelor apartment I had ever seen. The living room was 60 feet long, with a raised dais, at one end, which held two grand pianos.

“But what I remember best about that evening was Frederic McLaughlin, our host. When we came in he walked down that long room to take my hand. From that moment on, he dominated the evening. Little did I know how he was to dominate my life.

“He was not handsome. He had a long face and rather a flat head at the back. He had a high forehead with thinning hair and a weak chin and a mustache. He was nearly 16 years older than I. But he was a man of great distinction, and although he was only 6 foot 2, he seemed much taller.

“Following the dinner, Frederic announced his intentions of seriously pursuing me. I was forced to step on his intentions. I rarely had free time when I was dancing and much of the time I was too tired to see anyone.

“He took me home that night and on the way to the hotel he tried to kiss me. I blushed and dodged.”

Only 6-foot-2? Geez. Anyway, Irene wasn’t really looking for the love of her life. In truth, she’d already had that. Back in the 1910s, she and her first husband Vernon Castle became a phenomenon of modern dance, both on Broadway and in early silent films, particularly for their mastery of the foxtrot and the so-called “Castle Walk.”

[Irene and Vernon Castle performing in the 1915 silent film The Whirl of Life]

In 1918, 30 year-old Vernon Castle was killed in a plane crash; a tragedy retold in the 1939 Fred Astaire & Ginger Rogers film The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle. After that, a devastated Irene carried on as a solo act, and eventually married the well-to-do Robert Treman of Ithaca, NY, who invested much of her income and lost it in the stock market. She parted ways with him swiftly, but wasn’t technically divorced yet when she found her way into Frederic McLaughlin’s complicated Windy City world.

“My relationship with Frederic McLaughlin started perhaps as a flirtation,” she wrote in her memoir. “I was flattered by his attentions. He was charming, but I was a little scared of him. Robert Treman had been a gentle wooer, of the old romantic school. Frederic was the cave man type and a man of sudden and irrevocable decisions. He had decided he was going to have me, and as far as he was concerned, that was that.”

Irene actually was quite against the prospect of ever marrying Frederic, even after her divorce from Robert Treman was granted. But Fred dogged her tirelessly across the country in a courtship that spoke to some level of spoiled privilege. Still, like the aroma of a fresh cup of McLaughlin’s coffee in the morning, Irene kept getting drawn back in.

In 1923, she agreed to set a wedding date, then almost immediately regretted it, and set forth on a plan to cancel the engagement on the day of the wedding, like a Jazz Age version of a Julia Roberts movie (which, by the way, is a slam dunk Hollywood pitch). Irene was finally forced to confront Frederic face to face.

“I was no match for him. The Irish are clever. He started by putting me on the defensive.

“‘I thought you were a good sport,’ he said, ‘and no good sport would do a thing like this.’

“‘I don’t see that sportsmanship has anything to do with it,’ I said. ‘I wouldn’t marry anybody just to keep them from thinking I wasn’t a good sport.’

“‘Have you ever thought how this is going to make me look?’ he said.

“‘Well, nobody knows about it,’ I said. ‘You’ve been so careful to keep it from everybody.’

“He advanced 8 or 10 reasons why I was in too deep to get out of it. I gave him 20 reasons why I shouldn’t marry him.

“When all else failed, Frederic turned to an Irishman’s last resort—tears. I don’t mean he sobbed out loud or threw himself on the floor crying buckets. This was a manly display. He stood erect, but tears welled up in his eyes and threatened to spill over. I have never been able to see a man cry. I gave in.”

[Irene Castle and Frederic McLaughlin wedded “bliss,” 1923]

What started as a dark comedy, however, was sometimes just plain dark. For their honeymoon, the new couple took a ship across the Pacific to tour Japan and China. Frederic was seasick most of the way, and at two different points in the tour, turned to violence when arguing with his wife.

“I walked over in his general direction, and the next thing I knew I was lying on the floor,” Irene wrote. “I hadn’t fallen. I had been felled with a neat right cross. It was my first acquaintance with his ungovernable temper.

“I overlooked it after pouting a while. He was just seasick, I told myself. He didn’t know what he was doing.

“These stormy episodes did nothing to convince me I had made a right choice. From the distance of a few hours I could always look back and feel sorry for him because the last thing he wanted to do was to alienate me. He just couldn’t help it. He was his own worst enemy, and he took offense so easily. Once he had punched somebody, he was dreadfully embarrassed, and this only made him madder.”

Improbably, the rocky marriage lasted 20 years, all the way up to Frederic’s death in 1944. To her credit, however, Irene Castle always found plenty of positive ways to direct her time and energy. Though she gave up her dancing career to raise two children, she was still an active socialite and contributed a great deal to the community as well as the worlds of art and fashion. She is even credited with creating the original design for the Blackhawks logo that’s still essentially in use 90 years later.

Irene also turned her attention to one of her life’s greatest loves—the care of animals.

Irene also turned her attention to one of her life’s greatest loves—the care of animals.

“Irene would most like to be remembered for Orphans of the Storm,” her granddaughter says. “That’s the animal shelter she started [in Deerfield, IL] and which is still in operation. She was an avid crusader for animal rights.”

Irene married again after Frederic’s death, but after her own death at age 75 in 1969, she was interred with her first love, Vernon Castle.

Meanwhile, in the wake of Frederic’s passing in 1944, his nephews Herbert P. McLaughlin (1904-1967) and George F. McLaughlin (1901-1971)—both sons of the departed George D.—took over the family coffee business, lifting it to some of its loftier financial heights in the 1950s, when Manor House sponsored early local TV programs like Studs Terkel’s landmark show, Studs’s Place. Herbert was still serving as company chairman at the time of his death in 1967, which seemed to set the stage for the sale of the business to National Dairy just months later.

The two surviving children of Frederic McLaughlin and Irene Castle—Barbara and William Foote McLaughlin—both went on to successful careers of their own. The latter, in the stylish manner of family tradition, raced sports cars for a time in the mid ‘60s, and was involved with W. F. McLaughlin & Co. up until its sale. He later worked in real estate management in the South, but continued to preserve the legacy of his namesake grandfather’s coffee company and his mother’s animal shelter. William’s daughter Castle, named for her grandmother, is carrying that torch while also pursuing her own areas of historical interest. She has published several books on the American West, most recently A Lakota War Book from the Little Bighorn: The Pictographic “Autobiography of Half Moon“.

Coffee is always helpful for historical research of any sort. Unfortunately, I will never know if the taste of McLaughlin’s Manor House, or the Imperial Mocha and Java, live up to that supposed XXXX level of quality. Our tin, sadly, is an empty one, and no further orders are being taken.

Sources:

Castles in the Air, by Irene Castle

Chicago Stadium, by Paul Michael Peterson

“Help Our Friends” – The Labor Champion (Topeka, Kansas), Oct 16, 1903

“McLaughlins of Chicago Fill Coffee Cups for a Century” – Chicago Tribune, April 7, 1952

“William F. McLaughlin Dead” – Chicago Tribune, Feb 2, 1905

“G. McLaughlin Dies in Headon Auto Smashup” – Chicago Tribune, June 9, 1931

“Famous Dancer Again is Bride” – The Dispatch, Nov 30, 1923

Archived Reader Comments:

“Thoroughly enjoyable read. W.F. McLaughlin was my father’s name. I believe I’m the great grandson of the founder, though that link was severed by divorce in the 1930’s. No coffee dynasty money for me!” –Brendan McLaughlin, 2020

“My great great grandfather was Andrew McLaughlin (San Francisco), brother of W.F. McLaughlin… as for never having a chance to taste the coffee, I have a sealed can still full of coffee granules so there’s a chance! ” —Shay Miller, 2019

“Astonished! My family has a few collectibles from this company. I wish there was more information out there, I’d love to find out if im related!! ” —Brett Ashley McLaughlin, 2018

“Hi…great read..i was surprised to read the family came from Co. Laois in Ireland as the McLaughlin is from Co.Donegal in Ireland…” —Vinnie McLaughlin, 2018

“Am looking for TV commercials featuring the coffee. Please notify me at mmclaughlin@mail.com, thanks.” —M. McLaughlin, 2017

This coffee brand was well known in the Indianapolis area during the early to mid-1960s because of commercials that ran frequently on Indy TV stations.

What I remember most is the jingle at the end of the ads: “McLaughlin’s Instant Manor House Coffee.” I could still sing the tune today!

Always wondered why I never saw (or heard) those commercials after the late 1960s.

I have two paintings from my mother’s estate. “Girl and Birds” and “Child in Vineyard.”

Copyright 1900 by W.F. McLaughlin & Co. Chicago, ILL. Also says American Lithographic Company of New York. Can you help me with any information to find out more on these paintings.

I have a framed copy of Girl And Birds from the homesteaded Wisconsin farm where I grew up. Would like to know more about it. Says it was painted in 1877 and copy righted byMcLaughlin Co. in 1900.

My grandmother always would sing “Today is Tuesday, go to market day, time to buy McLaughlins manor house coffee. Was that a jingle or did she make that up?

I would love to be in touch with Castle McLaughlin. I was friends with her dad and stepmother, Dorothy, when they lived at Kiawah Island, SC. I have many stories, particularly about the bust Bill referred to as “Mother”. ejogier@gmail.com

I have a print of Kaiser Wilhelm II. It was printed by W.F. McLaughlin in Chicago and designed by Shober & Carqueville in Chicago as well. Is there any more information I can get on this piece?

I just purchased a large WF McLaughlin Co Shipping crate (wooden) minus the lid the crate was shipped from Chicago to Bonaparte Ia written in the box ink on the side

I am glad I found this site, as I have been curious about Manor house coffee for some time. I worked for Kraft Foods for 40 years. I remember seeing several pallets of Manor House Coffee in our warehouse in the 1970’s. I wondered how Kraft would have this coffee brand. Now seeing that it was sold to National Dairy after the family got out of the business explains it. National Dairy changed its name to Kraftco, then Kraft Foods during the 60’s and 70’s.

The Major hired ‘The First’ Native American in the NHL.

Think the Wirtz clan should rename the team the ‘Chippewa’

My dad, Art Kastensen, was a route salesman for Manor House coffee for about 10 years. He retired in 1965 and passed away in 1967. I have many memories of that time and a few pictures of company meetings, advertisements etc. Alas my favorite red plastic coffee measure is gone. Thank you for the article.

We have a green enamelware Coffee Dripolator and under the lid it says “For best results use only Mclaughlin’s Manor House Coffee. That is what led me to your article. I enjoyed it very much!

Thank you for the article, and all the information.

As a child I lived in a previous McLaughlin house on Edgewood Road in Lake Forest, Late 1950’s through 1965. I remember that “old man McLaughlin,” who sold his Edgewood house to my parents, had moved to a big white house near town on East Westminster in those days, across the street from the Episcopal Church of The Holy Spirit.

Hi,

Thanks for sharing this piece of Chicago history. My dad, Aleck Johnsen, was the brother of a service person Alice Joesel (mostly deaf) and her husband Richard, was the Major’s chauffeur. While they have passed, my dad is doing well at 96 still driving, and with fond memories of his time visiting while his sibling was in their service.

He played tennis with the children at the estate when visiting. And, grew up to be very successful business man in the grocery business.

My Aunt Alice and Uncle Richard had a few stories, like the fire at the rescue. And a pseudo kidnapping. Like to confirm if these stories are true.

If you’d like to chat, feel free to email me.

My grandfather was in Major Frederic’s 333rd Machine Gun Battalion during World War 1 and my mother told me that her father insisted that grandma only buy McLaughlin coffee because he served under his command. She also said the coffee cans had “333” printed on the label.

Do you have any knowledge if this is true or not?

I collect all sort of playing cards. I found a picture of W.F. Mclaughlin and behind his picture was a card from your coffee company. On it it has a black man, with his wife and child and a chicken. I’m looking for my cans of coffee of course emptied. I’d like to have someone from W.F. McLaughlins family call me.

I enjoyed reading this article. I was investigating the company to see if it still existed as I have what I believe to be prints of fairies which were used as a giveaway in a annual named Chatterbox in 1866 and 1888. I have found a basic image of the prints which were used in the McLaughlin Coffee ads, but the images I have are more detailed.

I want to sell the prints I have and trying to decide it I can print and sell them myself, of if I should sell the originals if there is any interest in them.

I have an early coffee tin from W.F. Mc Laughlin & Co. Black paper Label with gold/black lettering. Wondering it’s worth.

My father in law lived in the McLaughlin home in 1100 block of Green Bay Rd in Lake Forest back in the 70’s so I got to visit. It was a very gracious home built in 1900 I believe.