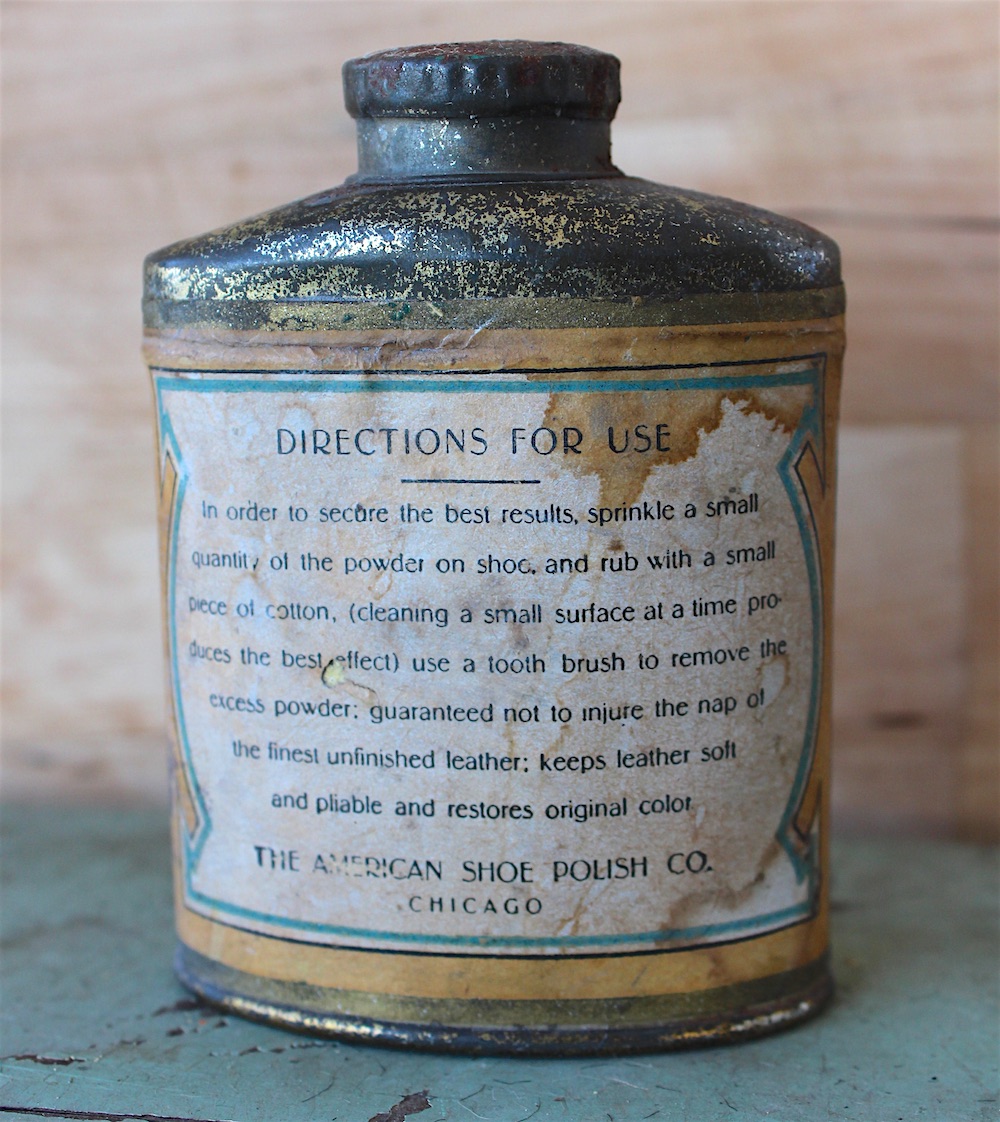

Museum Artifact: Eagle Brand Suede Powder, c. 1920

Made by: American Shoe Polish Co., 1956 S. Troy Street, Chicago, IL [North Lawndale]

“Wherever footwear is worn and shoes are shined, the American Shoe Polish Company, of Chicago, have made their ‘Eagle Brand’ dressings known”—this according to a 1913 article in that much beloved periodical, Shoe and Leather Facts.

“Through a harmonious co-operation between the manufacturing and selling forces, a line of products of unmistakable merit have been marketed under this well known brand and year after year has marked the forward progress of this company.”

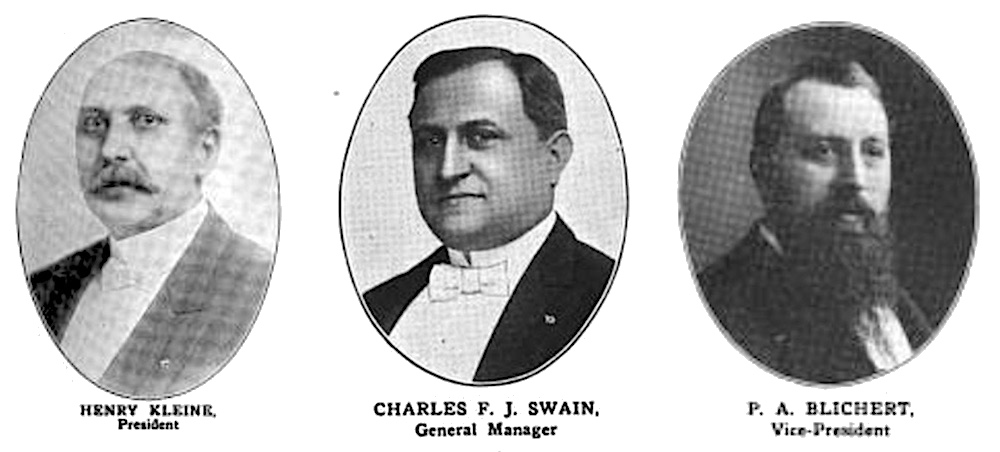

The American Shoe Polish Co. was certainly the result of a convenient confluence of talent and timing. Founded right at the dawning of the 20th century, the business was a tight-knit family affair, led by experienced shoe merchant Henry Kleine (president) and his ambitious son-in-law Charles F. J. Swain (manager and secretary).

The American Shoe Polish Co. was certainly the result of a convenient confluence of talent and timing. Founded right at the dawning of the 20th century, the business was a tight-knit family affair, led by experienced shoe merchant Henry Kleine (president) and his ambitious son-in-law Charles F. J. Swain (manager and secretary).

Kleine [born Heinrich Leopald Kleine] was a product of the old country, arriving in the U.S. from Prussia as a child in the 1860s. By 1876, he was already in the leather shoe business, just as mass production was making this classy footwear available to a wider portion of the public. His company, Henry Kleine & Co., would remain a familiar name in the marketplace well into the 1920s, running independently from the American Shoe Polish Co.

Charles Swain was born and raised in Dayton, Ohio, but headed west like so many other young men in the 1890s, looking for a new opportunity in the rapidly expanding centralized metropolis of Chicago. He was a fairly reserved, “stiff upper lip” sort of fella, but managed enough charm to woo and marry Lillian Kleine in 1899. From there, he moved in with the whole Kleine family at Henry’s cushy Lincoln Park apartment (present-day 2551 N. Clark St.), and went to work on managing a new business. Swain was 28 years old, living with and working for his fearsome-looking German father-in-law. One can presume there were some sleepless nights.

The final key player in this profitable polishing enterprise was a Danish immigrant named Peter A. Blichert—master of the shoe polish arts, head of the P.A. Blichert MFG Co., and new Vice President of the American Shoe Polish Co. If Kleine had the business savvy and Swain delivered the youthful drive, Blichert owned the secret formula to success. Literally—he created the product.

“With possibly few exceptions, [Mr. Blichert] is the best-known manufacturer of shoe polishes in this country,” claimed the folks at Shoe and Leather Facts. “He began making these goods in his native country, Denmark, many years ago, and soon after his arrival in the United States resumed the manufacture of shoe polish here. He has been interested and associated with The American Shoe Polish Company almost from its very beginning in the important position he has filled since that time.”

Henry Kleine had worked with Blichert in the past, as their industrial interests routinely overlapped. Now, the goal was to join forces to gain a foothold—pun intended—in the quickly emerging shine industry. Since Kleine had seen the benefits of getting ahead of the curve with his leather shoe outlet, he believed he could make lightning strike twice by pivoting toward this closely related field.

[“Shoeshine Boy,” an 1891 painting by Karl Witkowski]

[“Shoeshine Boy,” an 1891 painting by Karl Witkowski]

Shoe polish was far from a new concept in 1900, but the idea of buying the product as a packaged cosmetic—something to use repeatedly at home rather than just paying a shoeshine boy on a street corner—was still quite novel to many people. One 25-cent jar could supposedly deliver 80 separate shines; a pretty fine investment by anyone’s standards.

Kleine, Blichert, and Swain had a few established competitors when they launched the American Shoe Polish Co.—Whittemore out of Boston, Griffin MFG Co. out of New York, and the Nugget brand out of England, to name a few. Still, the ASPCo had a couple immediate advantages over most of its rivals. One was the close proximity of Chicago’s Union Stock Yards, creating easy and essentially unlimited access to the tallow, or animal fat, often utilized in early shoe polish formulas. Second, and no less important, was Henry Kleine’s deep-rooted connections in the shoe retailer’s business.

Kleine, Blichert, and Swain had a few established competitors when they launched the American Shoe Polish Co.—Whittemore out of Boston, Griffin MFG Co. out of New York, and the Nugget brand out of England, to name a few. Still, the ASPCo had a couple immediate advantages over most of its rivals. One was the close proximity of Chicago’s Union Stock Yards, creating easy and essentially unlimited access to the tallow, or animal fat, often utilized in early shoe polish formulas. Second, and no less important, was Henry Kleine’s deep-rooted connections in the shoe retailer’s business.

For much of the early 20th century, Kleine was the president of the National Leather & Shoe Finders Association, giving him a respected national voice known to hundreds if not thousands of shoe dealers. This gave ASPCo an avenue to sell its polish products by essentially using existing retailers as its ambassadors to the general public. Next came the branding . . .

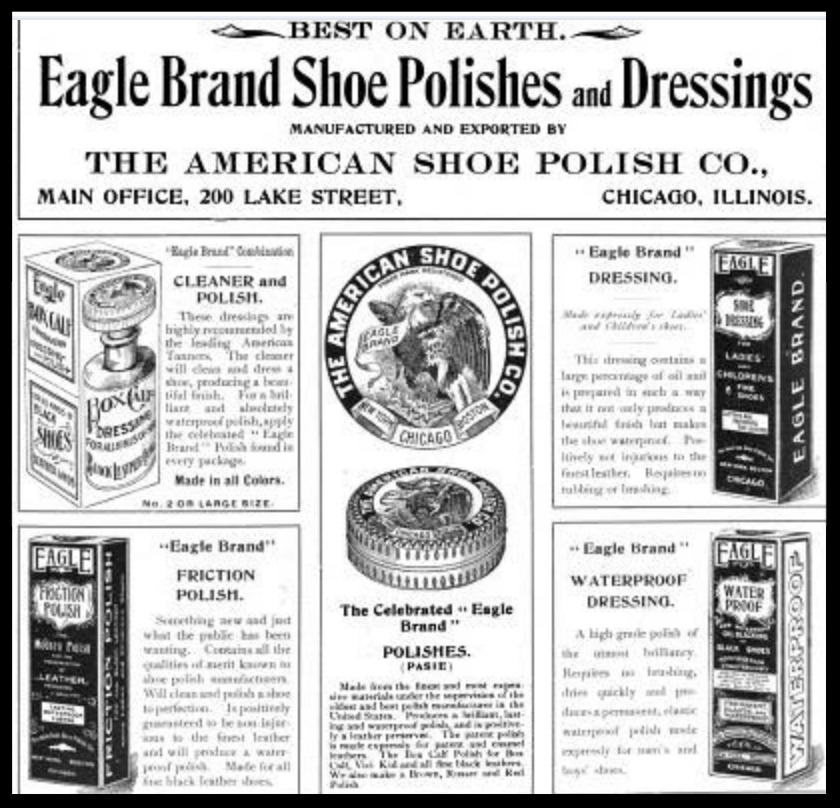

Henry Kleine’s early passion for shiny boots may have been influenced by his upbringing and the German attention to detail, but when creating a brand name, he made sure to emphasize the “American” in the American Shoe Polish Company. The “Eagle Brand” and associated flying eagle logo were tied to just about every ASPCo product over the company’s 30 year run, including the Eagle Brand Suede Powder tin in our museum collection.

Was it the most original concept of all time? Maybe not (I think we must have about a dozen other eagle logos represented in the museum). But it proved to be an effective mascot nonetheless.

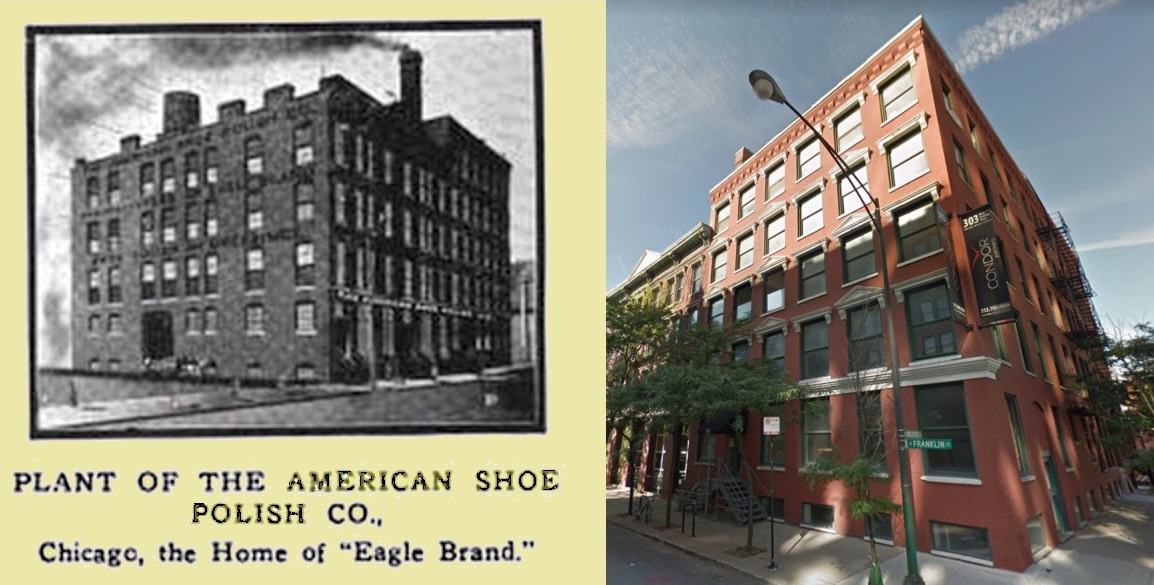

Initially operating out of a central office at 200 E. Lake Street, the American Shoe Polish Company soon moved into its own large-scale production plant at 220-230 N. Franklin St., which became 814-820 N. Franklin St. after the street number changes of 1909 and 1911.

In 1906, there were 17 workers employed in the factory; nine men and eight women. That number jumped to 25 by 1908 and 30 by 1914, with women making up about two-thirds of the work force. This doesn’t take into account the additional skilled salesmen the company employed across the country.

“The American Shoe Polish Company does not boast a large corps of representatives,” Shoe and Leather Facts reported in 1913, “but in that they are all trained men, familiar with the shoe polish business from A to Z, and among the best known and most popular salesmen in the trade, they take considerable pride.”

[Then and Now: The American Shoe Polish Co. plant at 814-820 N. Franklin Street]

[Then and Now: The American Shoe Polish Co. plant at 814-820 N. Franklin Street]

Within its first five years of existence, the American Shoe Polish Co. had not only become a major player on the national scene, but had international cache, as well. Blichert rolled out new variations of cleaners, powders, dressings, and specialty polishes, while Swain managed their production and Kleine pulled the necessary strings. The marketing was bold to the point of cockiness, specifically with campaigns geared at the industry insiders; the retailers, cobblers, and “shoe finders”—the specialists who helped contribute parts, components and accessories to the footwear field.

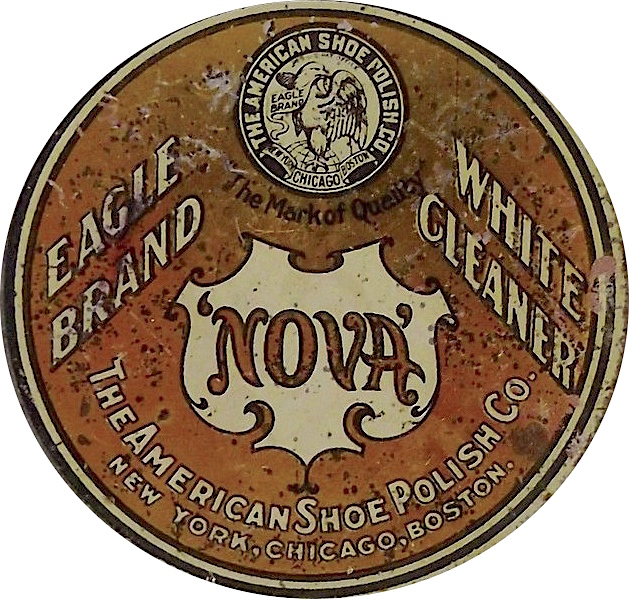

Every Eagle Brand product was pushed to this clientele as a groundbreaking revelation, from the Bestola shoe cream (“All who try it say it is the finest shoe polish they ever used”) to the Nova cleaner (“It looks different and better, it smells different and better, and it works different and better”).

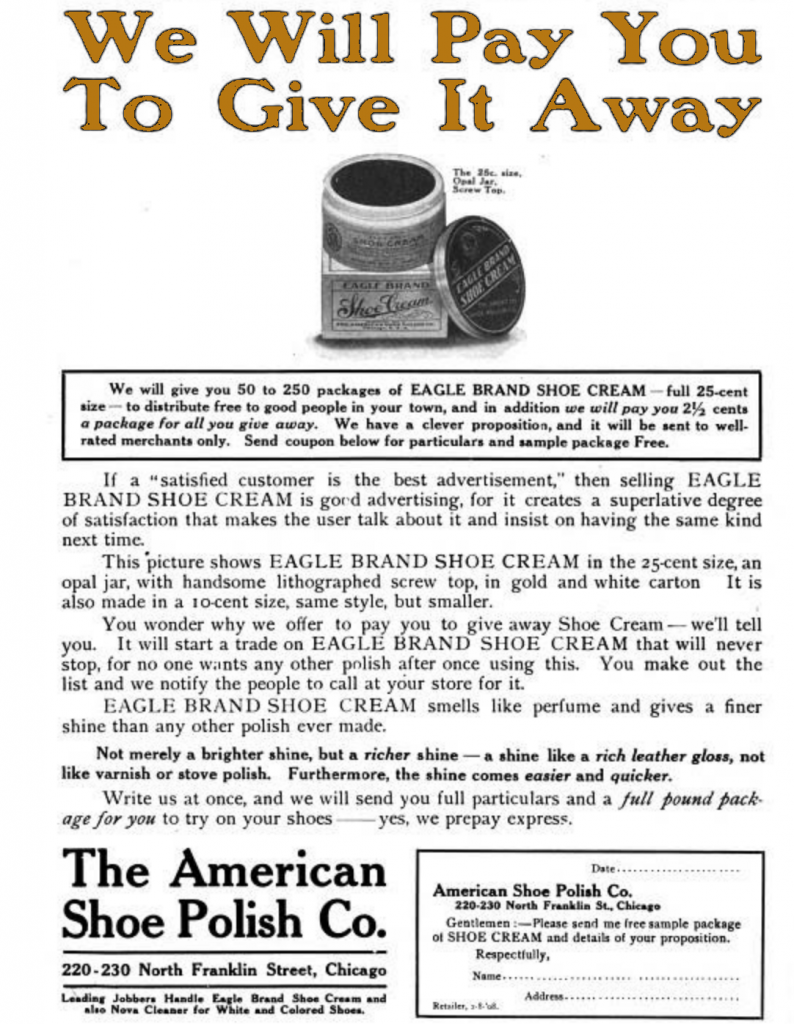

I suppose hyperbole is the standard procedure in any era of advertising, but ASPCo also put their proverbial money where their mouth was, using “give-away” promotions to virally spread the Eagle Brand legend.

“We Will Pay You to Give It Away,” read one advertising headline in an industry magazine called The Shoe Retailer. “We will give you 50 to 250 packages of EAGLE BRAND SHOE CREAM—full 25-cent size—to distribute free to good people in your town, and in addition we will pay you 2-1/2 cents a package for all you give away. . . . You wonder why we offer to pay you to give away Shoe Cream—we’ll tell you. It will start a trade on EAGLE BRAND SHOE CREAM that will never stop, for no one wants any other polish after using this.

“EAGLE BRAND SHOE CREAM smells like perfume and gives a finer shine than any other polish ever made. Not merely a brighter shine, but a richer shine—a shine like a rich leather gloss, not like varnish or stove polish. Furthermore, the shine comes easier and quicker.”

Another ad in the same 1907 campaign claimed “for years there was an insistent demand for a shoe polish that did not contain turpentine. We worked on it for years and two years ago we at last succeeded in perfecting it to our satisfaction, and called the product EAGLE BRAND SHOE CREAM. …Turpentine has no pleasant odor—EAGLE BRAND SHOE CREAM smells like violets. But even if this were not so, EAGLE BRAND SHOE CREAM would be a big success—for it gives a finer shine than any polish ever made.”

Hmm, but I thought they said “Bestola” gave the finest shine ever? Oh well, the important thing is that shoe salesmen were taking the bait, and times were good over at the Franklin Street offices.

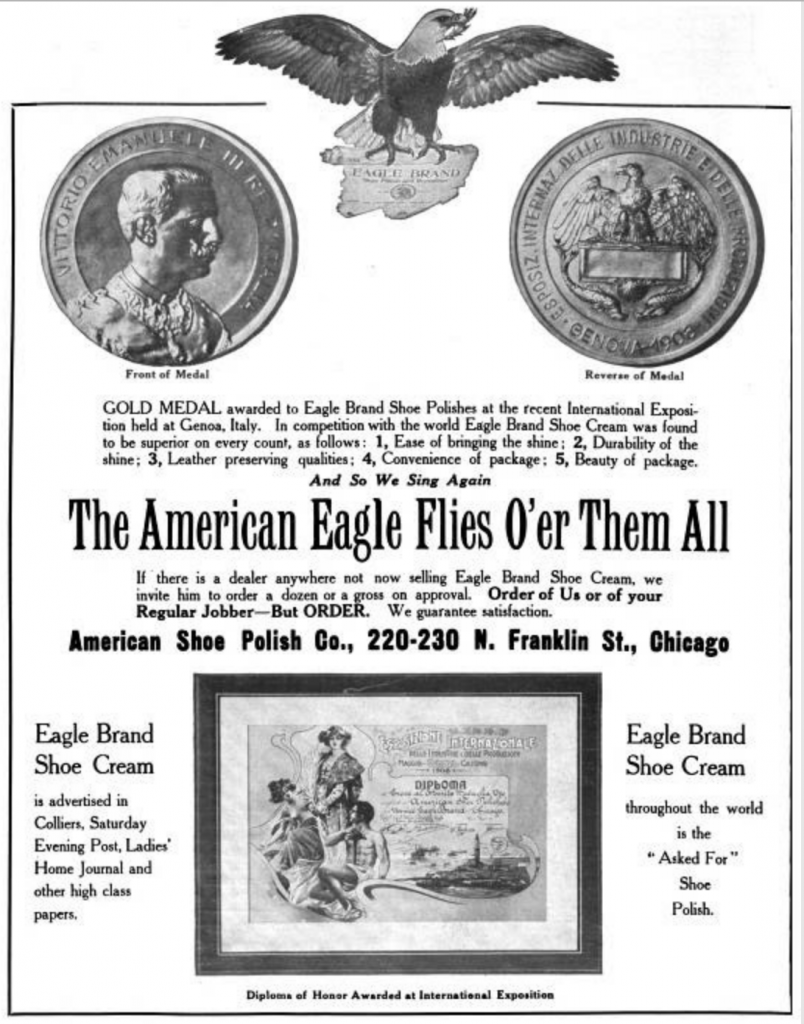

[A 1908 ad notes ASPCo’s success at an International Exposition in Italy]

[A 1908 ad notes ASPCo’s success at an International Exposition in Italy]

Maybe the best window into these fruitful days can be found in a small news blurb from that aforementioned 1907 issue of The Shoe Retailer.

The 25,000 Order

“When the American Shoe Polish Co. was founded some years ago, the founders agreed that when they had filled their 25,000th order, there would be a nice, quiet little celebration. This happy event occurred on January 3—that is, the 25,000th order was filled on that day. Noting the number on the order, and remembering the agreement, Manager Swain immediately reserved two boxes at the Illinois Theatre, Chicago, for Saturday night, January 6. The frisky Fritzi Scheff, in “Mlle Modiste,” was the attraction, and after the final curtain the happy party wended their way to the Tin Top Inn, where a sumptuous midnight supper was well taken care of.

“After a feast of impromptu speeches, and a flow of good spirits, carriages were called and the members of the company were taken home. Those present were: Henry Kleine, president, and wife; P. A. Blichert, vice-president, and wife; Chas. Swain, secretary and manager, and wife; C. F. Powers, assistant superintendent, and wife; E. S. Braymer, sales manager, and wife; the Misses Jones and Bigelow, cashiers.”

The Illinois Theatre was shut down for good during the Great Depression, but the Tin Top Inn is still in business, and the vocal stylings of the “frisky Fritzi Scheff” live on in digital form, helping us recreate a bit of that 1907 office party vibe here in the 21st century. Pass the champagne, Heinrich!

By 1911, an article in Dun’s Review cited the American Shoe Polish Company, now more than a decade old, as having “a trade that includes every country in the world” and a type of dressing for “every kind of shoe.”

“Besides the Eagle Brand paste polish, the firm make an Eagle Brand ‘Bestola’ shoe cream which they state will polish any leather made; the Eagle Brand royal black polish for dyeing and shining the shoe at the same time; also a variety of Eagle Brand combinations which include bottle of dressing and box of polish in different sizes and in all colors. Another specialty is the Eagle Brand ‘Dainty White’ for cleaning white canvas shoes and other articles made of that material. Still another specialty is the Eagle Brand ‘Nova,’ a cleaner made in sixteen colors and shades for cleaning or restoring color to canvas or leather. …This firm also make special patent leather dressing, dull leather dressing, suede dressing and dressings for bronze leather, ladies and children’s shoes, and for heels and soles, together with ‘Eagle Brand’ water-proof dressing, Eagle Brand friction polish, and Eagle Brand blacking, put up in five-pound pails for those who use this preparation in large quantities.”

At a convention of the National Leather and Shoe Finders’ Association in 1914, Henry Kleine told his cohorts that “Business is good now and it is going to be much better in a few weeks. The country looks great, and President Wilson is doing well in having talks with men of affairs.”

Like many of Chicago’s German businessmen of the era, Kleine was likely feeling a bit of growing discomfort related to the escalating conflict overseas, and the potential for American involvement. Nonetheless, ASPCo carried on with confidence, thanks in no small part to its manager Charles Swain, by now an old pro in his own right.

“Mr. Swain—known to nearly everyone in the findings trade as ‘Jim’—spends the greater part of his time at the home office,” wrote Shoe and Leather Facts [we will likely never known where that ‘Jim’ business came from]. “He is not a good booster for his own business—preferring instead to let ‘Eagle Brand’ products talk for themselves. As a character to interview, our representative says [Swain] is about as tough a proposition as he ever encountered, but, he added to his report: ‘He sure does know the shoe polish business and has the affairs of his company at his fingertips.’” [Photo: Charles and Lillian Swain, c. 1920]

“Mr. Swain—known to nearly everyone in the findings trade as ‘Jim’—spends the greater part of his time at the home office,” wrote Shoe and Leather Facts [we will likely never known where that ‘Jim’ business came from]. “He is not a good booster for his own business—preferring instead to let ‘Eagle Brand’ products talk for themselves. As a character to interview, our representative says [Swain] is about as tough a proposition as he ever encountered, but, he added to his report: ‘He sure does know the shoe polish business and has the affairs of his company at his fingertips.’” [Photo: Charles and Lillian Swain, c. 1920]

Coming up in the business world during the Teddy Roosevelt administration, it only makes sense that Swain adopted a “speak softly and carry a big stick” approach to his work.

Swain also acquired some additional help during the 1910s when a man named Otto F. Scholz joined the team as the new company secretary. Scholz had actually followed a very similar path into the business as Swain—more precisely, he married Henry Kleine’s other daughter Bertha in 1910.

The American Shoe Polish Co. carried on into and through World War I, enjoying the benefits of America’s renewed call for shiny boots, but also bending a bit against a growing roster of competitors.

Many of the firm’s new rivals were locally grown, as Chicago was fast emerging as the hub of the modern shine biz. There was the Dri-Seal Products Co. on West Kinzie; the Oil Filler MFG Co. at 1250 S. Fairfield Ave.; I. D. Smith & Co. at 2731 Quinn Street; Sunrise Shoe Polish Co. at 620 Blue Island Ave., and a couple of older but still relevant operations—Frick’s Shoe Polish Co. (124 W. Kinzie St.) and Martin & Martin (3017 Carroll Ave.), makers of E-Z Polish.

As a 1915 issue of Boot and Shoe Recorder put it:

“The rapid strides made during the past four years by Chicago in the way of becoming a national center for the manufacture of shoe dressings has hitherto obtained little public comment, yet it is a fact that the city today ranks nearly the equal of New York City in that regard, St. Louis coming third. . . . For every concern flourishing in the city today it is safe to say that six similar ones have been founded.”

Still, there was at least no argument yet as to which firm still wore the Chi-Town crown.

“The recognized leader of this industry in Chicago is, of course, the American Shoe Polish Co., of which Charles Swain is manager, and whose dressings have for many years past been sold all over the world. This concern makes a wide variety of polishes for nearly every leather and fabric and is operated upon a broad gauge basis which unfailingly commends it to the national trade. ‘Eagle Brand’ is a familiar sight in the shoe store findings cases and in shoe shining shops wherever one may go.”

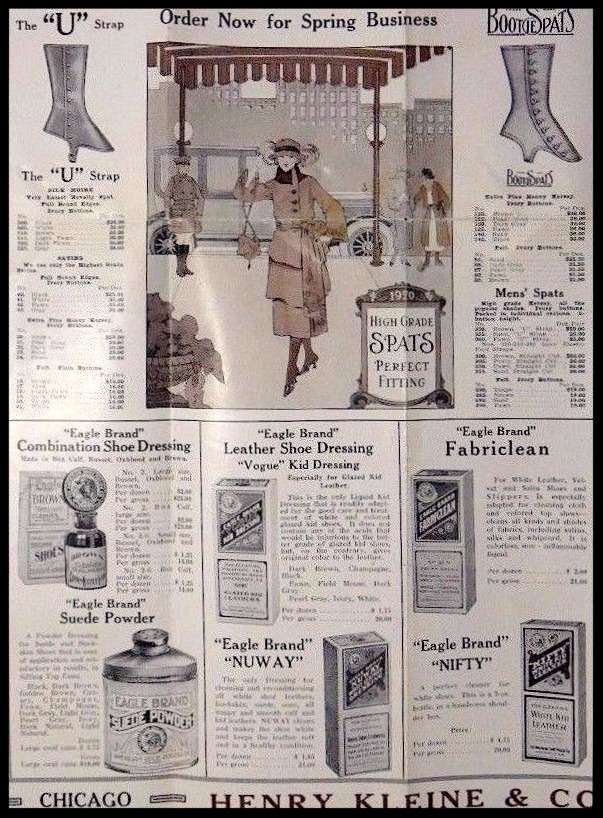

[A 1920 pamphlet for Henry Kleine & Co. includes listings for all the Eagle Brand products, including our Suede Powder; lower left corner]

[A 1920 pamphlet for Henry Kleine & Co. includes listings for all the Eagle Brand products, including our Suede Powder; lower left corner]

In 1920, Peter Blichert died, leaving ASPCo without its pioneering engineer [his son Frederick Blichert later formed the F. A. Blichert MFG Co., producing polishes in the style of his father]. The company survived the loss, still counting on the aesthetic excesses of the Roaring ‘20s to keep the Eagle Brand afloat. Somewhere along the line, though, it became clear that they’d need to expand beyond the footwear business if they wanted to compete for the long haul.

As a first step toward a new era, the main American Shoe Polish Co. plant moved to North Lawndale by the end of 1920, occupying a three-story space at 1956 South Troy Street; a building which has likely hasn’t survived, although its immediate neighboring building at 1954 S. Troy is still standing, and may or may not have been connected to the original plant.

[This building at 1954 S. Troy St. was either nextdoor or connected to the former American Shoe Polish plant at 1956 S. Troy]

[This building at 1954 S. Troy St. was either nextdoor or connected to the former American Shoe Polish plant at 1956 S. Troy]

Years later, in what might be considered phase two of the company’s soft relaunch, a decision was made to change the name of the firm to the “American Polish Company.” By dropping the “shoe” from the name, it would presumably make it easier to market the products’ other potential applications—most importantly, as it related to automobiles.

It’s unclear whether the re-branding idea came from the now elderly Henry Kleine, or if it was something pushed by the generation coming up to replace him. Either way, right about the time the name change was rolling out, Kleine died suddenly of heart failure on October 17, 1929, aged 75. One week later, the stock market crash put the future of both Henry Kleine & Co. and the American Polish Co. in considerable jeopardy.

[This ad campaign during the 1920s was ASPCo’s last before dropping the “shoe” from its name]

[This ad campaign during the 1920s was ASPCo’s last before dropping the “shoe” from its name]

Charles Swain appears to have been a working casualty of this tumultuous period. During the Depression, it was the younger Otto Scholz who took over the reins of the American Polish Company, while Swain’s 1930 census report shows him working as a “curtain salesman,” apparently out of the polish game entirely.

Swain reportedly had to have a leg amputated during this period, as well, and after his wife Lillian died in 1934, he lived out his remaining years with their adult daughter Irene at a rented apartment at 3930 N. Keeler Ave. in Irving Park. He breathed his last in 1941.

Otto Scholz Sr. died four years later, in January of 1945, and most signs of the American Polish Company seem to fade with him. Despite the explosion of interest in polish for soldiers’ boots during World War II, new brands like Shinola and Esquire had pushed the old Eagle Brand goods to the sidelines. The party was over.

Still, if you believe in an afterlife for the legends of the shoeshine trade, Fritzi Scheff is still out there somewhere, singing “Kiss Me Again” for Kleine, Swain, Blichert and an audience of dames and gents all dressed in their shiniest leather kicks.

And Now – A quick reminder of how to use your 1920 bottle of Eagle Brand Suede Powder:

“In order to secure the best results, sprinkle a small quantity of the powder on shoe and rub with a small piece of cotton, (cleaning a small surface at a time produces the best effect) use a toothbrush to remove the excess powder: guaranteed not to injure the nap of the finest unfinished leather: keeps leather soft and pliable and restores original color.”

Sources:

Shoe Retailer and Boots and Shoes Weekly – Volume 61, 1907

Shoe Retailer and Boots and Shoes Weekly, Volume 65, 1908

Shoe and Leather Facts, Vol. 33, 1913

Boot and Shoe Recorder, Vol. 67, 1915

Dun’s Review, Vol. 17, 1911

Buyers’ Guide and Industrial Directory of Chicago, 1922

The Dry Goods Reporter, Vol. 44, 1914

Archived Reader Comments:

“Thanks for this comprehensive exhibit which was so well researched and presented. My great-grandfather was P.A.Blichert and our family can now appreciate much of his past history that we were unfamiliar with, until this exhibit. As an FYI, my grandfather’s (Frederick Blichert) shoe polish business ended prematurely in 12/64. A teen-aged serial arsonist, Alan Norcutt, set fire to the building that killed a Chicago firefighter, Joseph Carone,Sr.” –Marguerite Siegei, 2018

“Wow! Thanks for this information. Frederick was married to my grandmother’s sister.” –Pat Colton, 2017

Frederick was married to my grandmother’s sister.” –Pat Colton, 2017

I found the box and can of shoe polish that was being thrown out and a garage sale.

I have pictures on my Facebook pa

Actually the building at 1956 S Troy still stands and has simply been reskinned at some point in the 1960s. The interior is still very much a vintage heavy timber structure.

Hello all. I am an archaeologist and encountered eleven Eagle Brand Shoe Cream jars in Skagway, Alaska. I am wondering when/if American Shoe Polish Co. transitioned away from the milk glass (perhaps into metal?). Basically I want to state in my report that the jar could have been manufactured between 1909 (based on the street number changes in 1909 and 1911 mentioned above) and 19__. Any help would be greatly appreciated. Thanks all.

I have seen cast iron shoe shine foot rests cast with the letters “g” and an “r” separated by a star. Any idea what the g and r stand for?