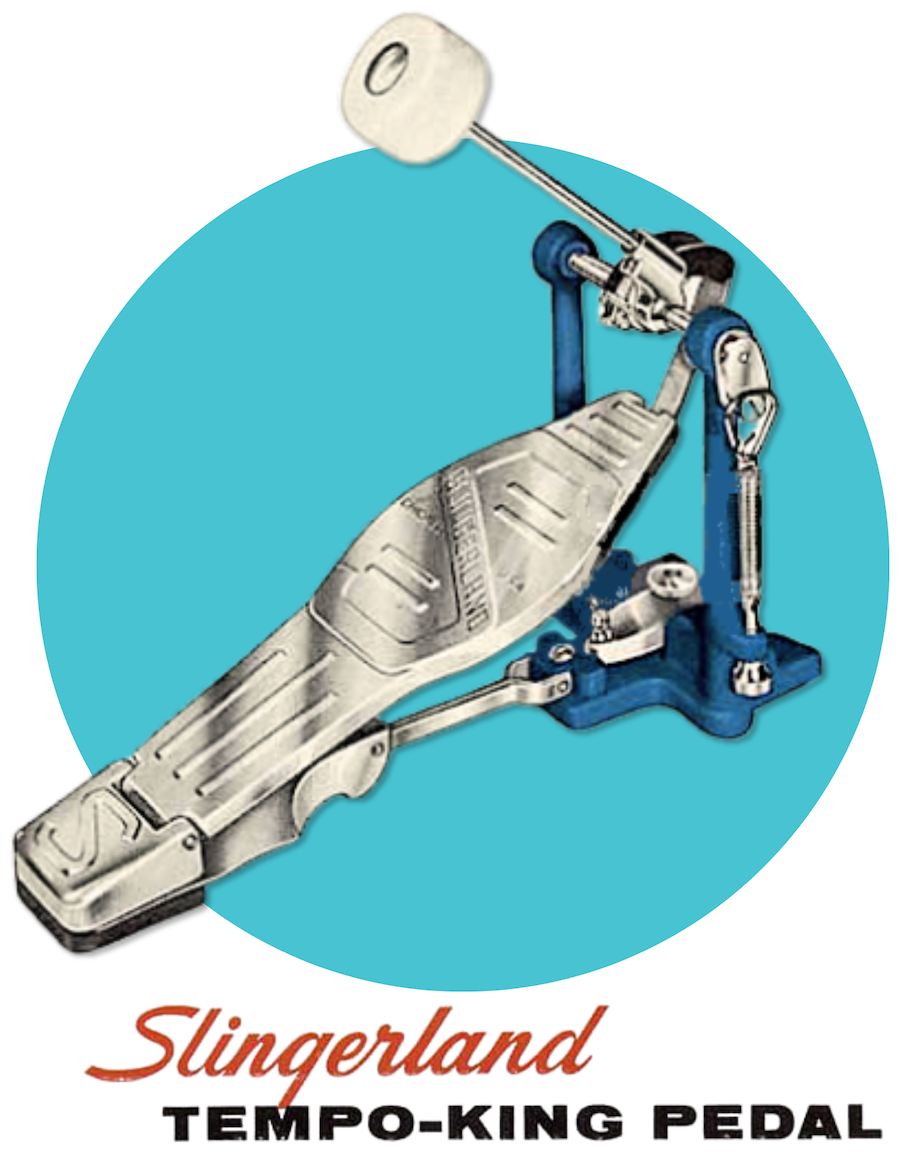

Museum Artifact: Slingerland Tempo-King Bass Drum Pedal, 1960s

Made By: Slingerland Drum Company, 6633 N. Milwaukee Ave. [Niles, IL]

“The Slingerland name is recognized the world over as the finest in drum equipment. . . . It is the only drum firm that manufactures and processes all of its own parts exclusively, which includes skilled wood-working, metal-working, plating, finishing and final assembling.” –Slingerland Drum Co. catalogue, 1964

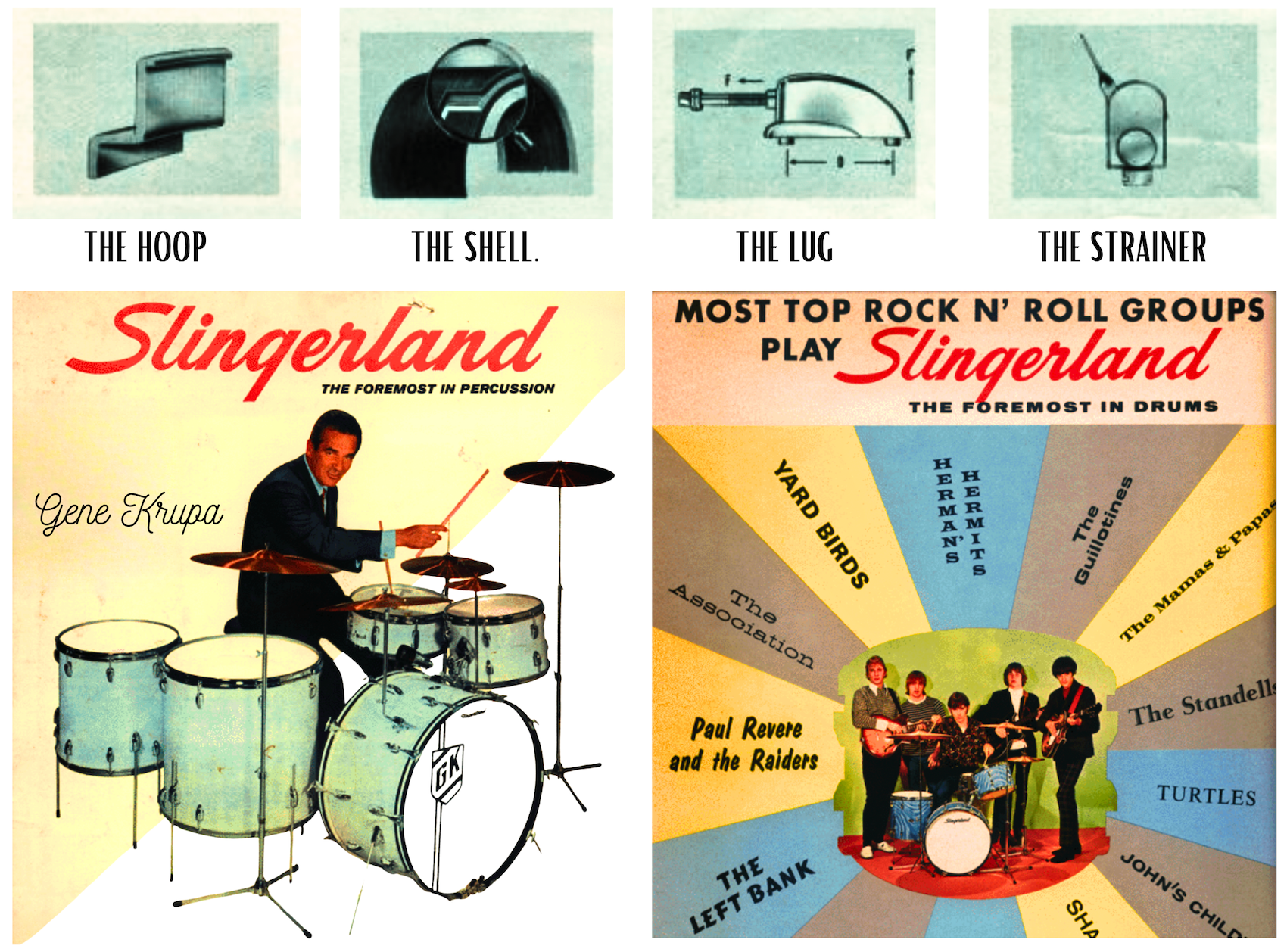

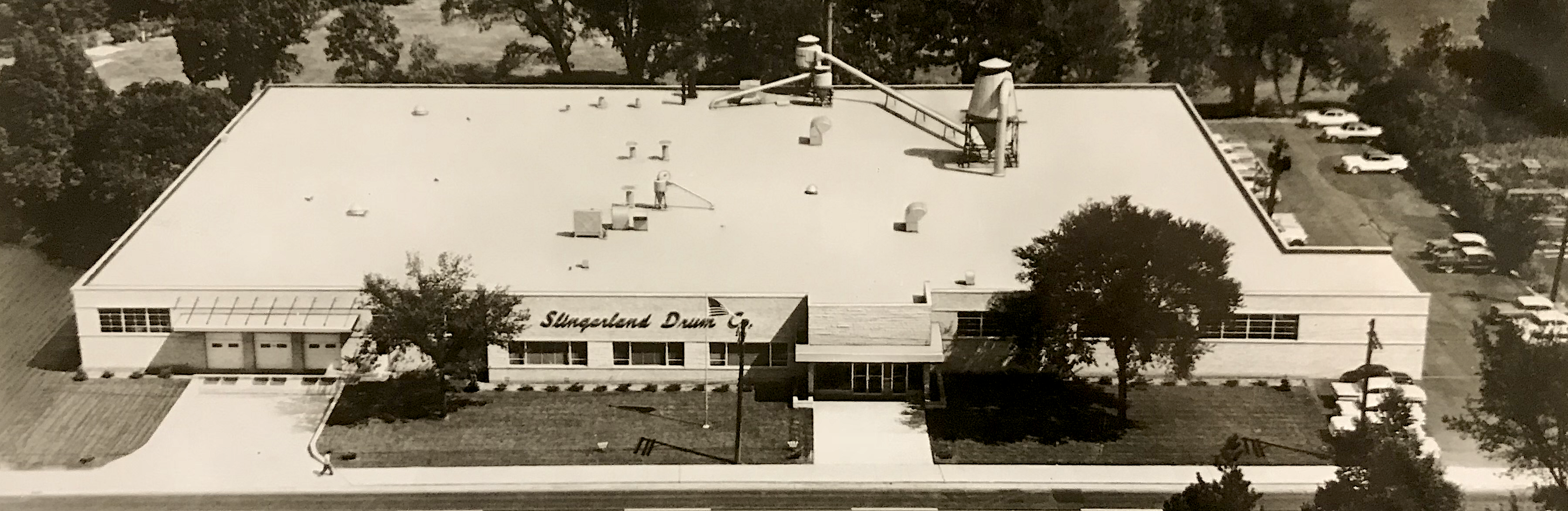

The “Tempo King” kick pedal in our museum collection debuted in the early 1960s, at a time when the Slingerland Drum Co. was reaching a commercial peak. About a half-century into its existence, the family-owned business was now—by its own calculations, at least—the “largest manufacturer of drum equipment in the world.” This was reflected in the company’s decision to leave behind its long-running Lincoln Park factory for considerably more modern digs in Niles, Illinois, just outside the Chicago city limits. From here, throughout those Swingin’ Sixties, Slingerland promotional materials touted the “Five Basic Reasons” its drums excelled beyond the competition—which primarily meant its crosstown rivals, the Ludwig Drum Co.

The “Tempo King” kick pedal in our museum collection debuted in the early 1960s, at a time when the Slingerland Drum Co. was reaching a commercial peak. About a half-century into its existence, the family-owned business was now—by its own calculations, at least—the “largest manufacturer of drum equipment in the world.” This was reflected in the company’s decision to leave behind its long-running Lincoln Park factory for considerably more modern digs in Niles, Illinois, just outside the Chicago city limits. From here, throughout those Swingin’ Sixties, Slingerland promotional materials touted the “Five Basic Reasons” its drums excelled beyond the competition—which primarily meant its crosstown rivals, the Ludwig Drum Co.

Reason Number One was “The Hoop,” a solid brass “Rim-Shot counter hoop” that was “the strongest made, guaranteeing perfect tension and sound from all Slingerland drums.” Reason No. 2 was “The Shell,” made from solid maple and “molded to a perfect circle and size in one operation.” No. 3, “The Lug,” was a special tension casing “made of a high tensile strength nonferrous alloy” for greater resistance, and No. 4, “The Strainer,” was the “strongest, smoothest, and most efficient snare strainer ever designed.” The fifth and final reason for Slingerland’s mightiness was the Niles factory itself, a brand-new 45,000 square foot facility where every step in the manufacturing process was overseen by a team of seasoned pros.

For a company that had built its reputation in the 1930s on the back of endorsements from jazz giants like Gene Krupa and Buddy Rich, the mid-t0-late 1960s also saw an opening up of the tent to musicians from the rock and pop landscape, with the 1967 Slingerland catalogue now boasting a roster of devotees that included everyone from the Yardbirds and the Mamas & the Papas to Herman’s Hermits and the Turtles. These upstart acts from the TV stages of American Bandstand were promoted right alongside the various old-school swing players still in Slingerland’s rolodex: Krupa, Rich, Tito Puente, Jimmy Campbell, etc.

To appease this broadening spectrum of musicians, Slingerland’s Tempo-King pedal was a necessary invention for the times, equipped with “twin ball bearing action” and a removable knurled screw above the spring, giving the drummer a choice of three kick settings: “left hole for hard playing, center hole for medium, and right hole for soft playing.”

“It’s no secret I prefer Slingerland,” read a 1969 testimonial from a 60-year-old Krupa, who was still arguably the world’s most famous drummer at the time. “They’ve got the sound and response I like. . . . Try Slingerland and see why they’re my drums!”

In more recent decades, it’s been hard to keep track of who’s still staking claim to the Slingerland name. Much like its old foe Ludwig, the company gradually morphed from a thriving, independent enterprise into a disembodied nostalgia brand—passed around among several of the remaining heavyweight conglomerates of the musical instrument industry.

After Slingerland’s trademarks were acquired by Drum Workshop Inc. (DW Drums) in 2019, they subsequently wound up under the bigger umbrella of DW’s parent company, the Roland Corporation (Ludwig, similarly, is now owned by Steinway). As of 2025, Roland and DW were promoting the relaunch of some classic Slingerland kit designs, keeping the legacy alive. Actual manufacturing in the Chicagoland area, however, ended a long time ago, as the former Slingerland plant in Niles was recently torn down and replaced with a new apartment complex.

[The former Slingerland Drum Co. factory at 6633 N. Milwaukee Avenue, as it looked in 1960. The building was demolished in 2024]

A History of the Slingerland Drum Co., Part I: The Conservatory

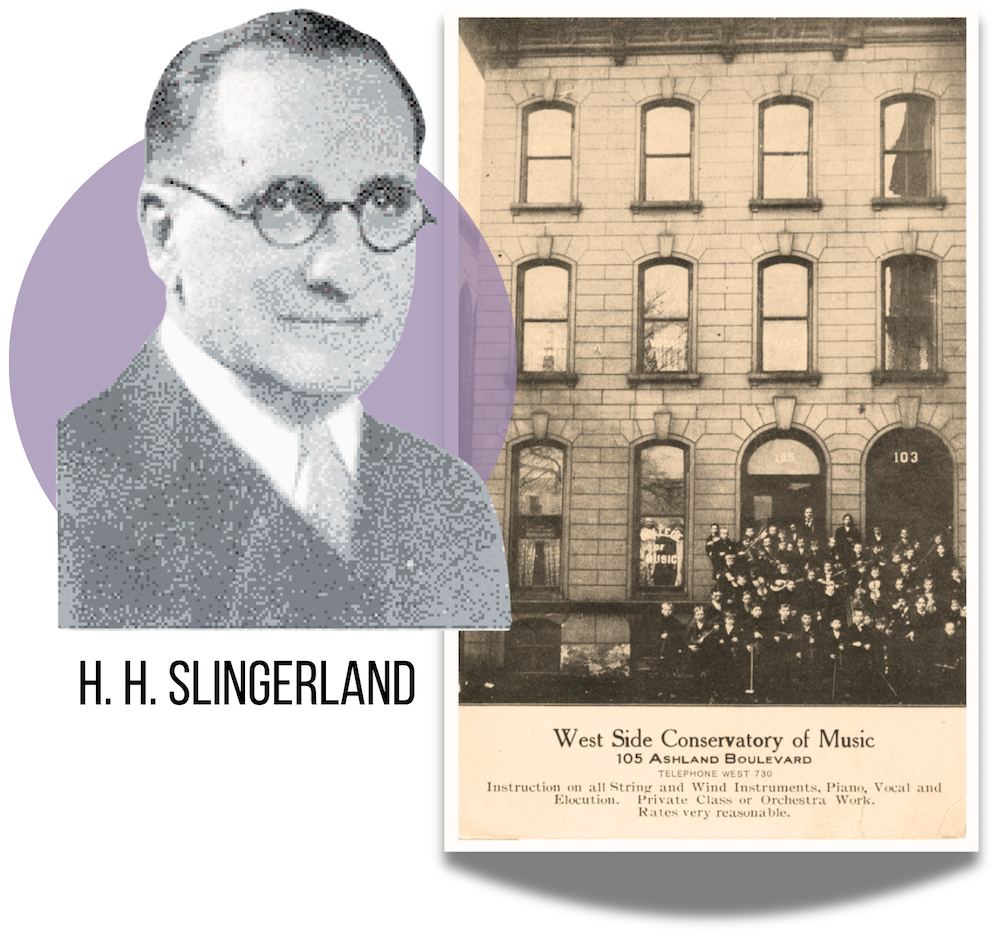

Henry Heanon Slingerland grew up on the opposite side of Lake Michigan from Chicago, near the top of the Michigan mitten in the town of Manistee. Born in 1875, he was the first of eight kids raised by Samuel and Amalia Slingerland, farmers who came into some considerable wealth thanks to a few astute real estate deals. Henry Heanon, better known as H. H., clearly picked up some of these business instincts. One of his early ventures was a Lake Michigan gambling boat he operated from Manistee. When that enterprise literally went up in flames (i.e., the boat caught fire) in 1905, H. H. started fresh in Chicago with an entirely different business idea.

Despite not having any significant training in music himself, Slingerland set about opening up a training school—not for drummers, but for children interested in the violin; an instrument that was typically considered too complex to learn in a group setting.

Despite not having any significant training in music himself, Slingerland set about opening up a training school—not for drummers, but for children interested in the violin; an instrument that was typically considered too complex to learn in a group setting.

“Mr. Slingerland decided to prove his theory that the most satisfactory training could be given in classes,” Chicago’s Inter Ocean newspaper reported in 1908. “Surrounding himself with a strong faculty who were in perfect accord with his ideas, he began the experiment. The result has been beyond his anticipations. The students in the violin department of the two conservatories are making remarkable progress. . . . Just normal children, their violin work is creating comment wherever it is known, and an occasional genius is discovered whose talent is very promising for future greatness.”

We’re not sure if any true virtuosos actually emerged from Slingerland’s West Side Conservatory of Music, as it was called, but the school at 105 Ashland certainly seemed to be drawing a lot of students. Between 1905 and 1908, according to the Inter Ocean, “Mr. Slingerland has put out to his pupils almost 10,000 violins . . . an amazing record for one music school.”

Slingerland did boast in these early years that all of his stringed instruments were special-ordered from leading manufacturers in Bavaria. This would remain the case through the early 1910s, as H. H.—now joined by his brother John—expanded his music teaching empire to include a South Side Conservatory of Music (at 6424 S. Halsted) and the Slingerland Correspondence School of Music (431 S. Wabash).

[Three of H.H.’s brothers joined his budding music education business in Chicago. The Slingerland Correspondence School of Music is advertised in 1915 (left) and 1923 (right)]

It wasn’t until World War I, when German imports were severely limited, that H. H. Slingerland was forced to consider manufacturing his own instruments to keep up with demand. There was still no beat of drums to be heard at this point, but with two more Slingerland brothers brought into the fold—Walter and Arthur—there was a concerted effort in the late 1910s and early 1920s to turn the Slingerland Correspondence School of Music into an all-in-one educational option not just for students in Chicago, but anywhere in the country. Advertisements in national magazines like McClures and Popular Mechanics now enticed readers with the offer of a FREE instrument of $20 in value—shipped via mail order straight to their home—if they signed up to receive lesson books from the Slingerland’s Chicago office. Customers could choose a violin or an array of other offerings, including guitar, ukulele, banjo, and mandolin. “Wonderful new system of teaching note music by mail,” read one 1919 ad. “Very small charge for lessons only. We guarantee success or no charge.”

Notably, the “free” instruments were only offered to the “first pupils in each locality,” meaning any future recruits would presumably be asked to pony up an extra $20. Whatever the racket was, though, it proved successful, and the Slingerland Brothers soon had no choice but to start producing their own instruments on a much larger scale.

Part II. Kings of Swing

“A large musical instrument factory, catering to the needs and requirements of the modern drummer and drum corps, is comparable to the present day symphony orchestra rendering its concert before a critical audience. The personnel of the executive and factory force is selected as precisely as qualified musicians are for the modern symphony. . . . To satisfy drummers, to be sympathetic toward their requirements, and to really wish to serve them, you must have within, an organization of men who are and who have been professionals of the highest calibre. By so doing. a common and unbreakable bond exists between drummers and factory.” –H. H. Slingerland, 1936

The Slingerland Banjo Company, as it was originally known, was properly incorporated in 1923, and a dedicated factory space was acquired around the same time at 1815 N. Orchard Street in Old Town. The “Maybell” brand of banjo was the company’s first calling-card instrument in the ‘20s, and by 1925, Slingerland advertisements in trade magazines like Etude described the Chicago firm as the “largest manufacturer of banjos in the world. Over 3,000 dealers sell them and say our line is the best.”

The Slingerland Banjo Company, as it was originally known, was properly incorporated in 1923, and a dedicated factory space was acquired around the same time at 1815 N. Orchard Street in Old Town. The “Maybell” brand of banjo was the company’s first calling-card instrument in the ‘20s, and by 1925, Slingerland advertisements in trade magazines like Etude described the Chicago firm as the “largest manufacturer of banjos in the world. Over 3,000 dealers sell them and say our line is the best.”

“At the beginning, [Slingerland] wasn’t any competition to Ludwig & Ludwig, because at first, Slingerland was a banjo and ukulele manufacturer,” William F. Ludwig, Jr., recalled to Modern Drummer magazine in 1987. “Mr. [H.H.] Slingerland was not a drummer, but he was a heck of a good businessman. . . . The banjo and ukulele craze brought great growth to the Slingerland Banjo Company. It was spurred by stars such as Rudy Vallee on the uke, and Pinketori, with the great Paul Whiteman Band of the ’20s, on banjo.”

Ludwig’s father, William Ludwig, Sr., gambled on that banjo craze himself in the 1920s, deciding to split his own company’s drum-building resources in order to start manufacturing more stringed instruments. H. H. Slingerland supposedly heard about this and reached out to Ludwig with an offer: if Ludwig stayed out of the banjo game, Slingerland wouldn’t try to compete in the drum market. Ludwig scoffed at the idea and blew off the deal, feeling like his more established business had the upper hand. The feud quickly played out to Slingerland’s benefit, however.

By 1929, with the banjo craze waning and the economy in freefall, William Ludwig, Sr., found that his decision to compete in the string instrument game had abruptly emptied his coffers. He was forced to sell Ludwig & Ludwig to the C. G. Conn Corporation of Elkhart, Indiana. This was a grand turn of events for Slingerland, which had just put out its first drum catalogue a year earlier, building its own line inside a new facility at 1325 West Belden Avenue in Lincoln Park. Now, with Conn planning to move Ludwig’s operations out of Chicago, H. H. Slingerland leapt at the chance to reap the regional benefits.

[Pages from the first Slingerland drum catalog in 1928. Slingerland acquired the Liberty Musical Instrument Co. in order to get started in the drum field, then purchased equipment from the original Ludwig & Ludwig factory to expand the enterprise in the 1930s. Part of the Slingerland plant at 1325 W. Belden Avenue is still standing today, as pictured, converted into apartments.]

“H.H. knew that a lot of [Ludwig’s] dies, fixtures, and bending machines would be for sale,” William Ludwig, Jr., told Modern Drummer, “so he had his agent go to the auction and buy it all! He moved it out of the Ludwig plant, two miles north to the Slingerland plant [on Belden Ave.].”

Most drum manufacturers were desperately trying to stay alive in the early ‘30s, not just as a consequence of the Great Depression, but also the demise of silent movies, which had utilized live percussionists to provide music in cinemas all over the world before “talkie” films made them obsolete. H. H. Slingerland, a noted gambling man going back to his riverboat days, saw the struggles of his competition only as a good omen for his own chances. And sure enough, with the aid of his brothers and a shrewd sales manager named Sam Rowland, the newly re-named Slingerland Banjo & Drum Company thrived.

“One of the greatest outstanding features of the National Music Trades Convention was the large amount of enthusiasm shown by the dealers when looking over the new SLINGERLAND Line of Professional and Amateur Drums,” read an ad in the Metronome trade magazine. “Instruments that embody the knowledge and skill of the foremost drum craftsmen and designers, they are as distinguished in appearance as they are perfect in workmanship.”

“One of the greatest outstanding features of the National Music Trades Convention was the large amount of enthusiasm shown by the dealers when looking over the new SLINGERLAND Line of Professional and Amateur Drums,” read an ad in the Metronome trade magazine. “Instruments that embody the knowledge and skill of the foremost drum craftsmen and designers, they are as distinguished in appearance as they are perfect in workmanship.”

By 1936, when American families were enjoying the escapist fare of live jazz concerts on the radio, Slingerland’s “Radio King” line of snare drums—“a model with all the refinements of the most expensive drums at the conventional cost of ordinary models”—joined a growing inventory of instruments and kits aimed at a fairly eclectic clientele: be it a high school marching band drummer or a professional nightclub musician. These drums weren’t necessarily the most innovative designs structurally (Ludwig’s lawyers were routinely shouting about patent infringement), but players liked both the performance and the price tag.

As best evidence of Slingerland’s legitimacy was its new 1936 catalog cover model and spokesman, 27-year-old Chicagoan Gene Krupa, famed drummer for the Benny Goodman Band and soon-to-be leader of his own big band orchestra.

“Want a thrill?” read a 1936 Radio King ad featuring Krupa at his kit. “How would you like to sit down behind a snare drum so responsive that you scarcely had to touch your sticks to the head? One that retains its ultra-sensitivity in even the dampest weather? There is such a snare drum! It’s the new SLINGERLAND Super Streamlined ‘Radio King.’ It has such a rich tone that it seems almost like a melody instrument. And it’s tough, too. It’ll take your most murderous rim shots. It has Streamlined Strainers and Modernistic Double Lugs. It’s a honey all right—the fastest, sweetest drum that ever backed up a rhythm section. You owe it to yourself to have your dealer show it to you.”

[Gene Krupa began endorsing Slingerland in 1936 and helped dramatically change its fortunes]

It was Krupa’s tom-toms, more than the snare, however, that changed the game.

“[Krupa] got Slingerland to make tunable toms while we were still making tacked bottom heads,” William Ludwig, Jr., later recalled. “H.H. listened to Gene. Being a part of [the Conn Corp] conglomerate, we [Ludwig & Ludwig] were slower to react.”

When Ludwig Jr. and his father saw Krupa playing a Slingerland kit with the Benny Goodman Band at Chicago’s Congress Hotel, they knew they were beaten. “We were stunned to see that the drummer was playing alone,” he said, recalling the famous, lengthy tom-tom solo on ‘Sing, Sing, Sing,’ which was played on “the first of the 16-inch toms Krupa got H. H. Slingerland to build for him with tunable heads on both sides, set on a stand. They took that act on the road and it changed everything overnight. The trend became a streamlined set of four drums, cymbals, and a cowbell. . . . Gene went straight to the top and had the greatest fame of any drummer in history.”

When Ludwig Jr. and his father saw Krupa playing a Slingerland kit with the Benny Goodman Band at Chicago’s Congress Hotel, they knew they were beaten. “We were stunned to see that the drummer was playing alone,” he said, recalling the famous, lengthy tom-tom solo on ‘Sing, Sing, Sing,’ which was played on “the first of the 16-inch toms Krupa got H. H. Slingerland to build for him with tunable heads on both sides, set on a stand. They took that act on the road and it changed everything overnight. The trend became a streamlined set of four drums, cymbals, and a cowbell. . . . Gene went straight to the top and had the greatest fame of any drummer in history.”

The endorsement from Krupa, the “King of Swing”—and his direct collaboration with Slingerland on the R&D side of things—left no doubt as to which company had taken the mantle as Chicago’s premier drum maker.

Inside Slingerland’s Chicago Factory, circa 1930

[1- Wood shop. 2. Tone flange production in the machine shop. 3. Metal working. 4. Machine shop. 5. Final drum assembly. 6. Drumstick turning.]

By the late ‘30s, the Slingerland factory on Belden Avenue had a rhythm and energy to match the swing bands it was equipping. Its instruments didn’t just have a reputation for quality, but for flare and style, with colorful pearl and antique finishes enabling customization to match each drummer’s character. “People, whether they be dancers, diners, theater goers, or regardless of their stations in life, are instinctively attracted to the drummer,” stated the company’s 1936 catalog. “He becomes the focus of all eyes, and it behooves him to create at first glance a personality that will assist him in not only selling himself but his band.”

In 1937, William Ludwig, Sr.—regretting the sale of his original business to C. G. Conn—established a new one back in Chicago, called W.F.L., and poached Slingerland’s sales guru Sam Rowland in the process. Having Ludwig back as a crosstown foe only helped keep Slingerland on its toes, however, and the company continued to push new products—not just in the percussion field, but in stringed instruments, as well.

The Songster Electric Guitar, introduced in 1939, is considered by some to be the first Spanish-neck, solid-body electric guitar ever sold, pre-dating the first Les Paul by at least a year. Despite its historical significance, though, the Songster wound up more of a brief experiment for Slingerland—the company abandoned electric instruments by the start of the 1940s.

Part III. Best Buds

“The finest drummers in the country who can afford any make or model of drums are unanimous in their belief that Slingerland makes the best drums.” —1943 advertisement

While many music instrument manufacturers had to slash their output during World War II, Slingerland did better than most—adjusting to metal rationing by introducing a wood-frame “Rolling Bomber” kit and keeping up orders for schools and marching bands as an acceptable service for the nation’s morale.

Jazz was still king during these years, of course, and Slingerland was still the dominant name among jazz’s top drummers. In a 1943 reader’s poll in Down Beat magazine, five of the top seven players in the field—Buddy Rich, Dave Tough, Jo Jones, Maurice Purtill, and Frank Carlson—were Slingerland loyalists. Gene Krupa wasn’t getting the votes from the Down Beat crowd by this point, but he was still the biggest star in the game; so much so that he eventually was able to negotiate a deal with Slingerland to collect cash royalties off every drum kit the company sold. The age of the megabucks celebrity endorsement deal had arrived.

Jazz was still king during these years, of course, and Slingerland was still the dominant name among jazz’s top drummers. In a 1943 reader’s poll in Down Beat magazine, five of the top seven players in the field—Buddy Rich, Dave Tough, Jo Jones, Maurice Purtill, and Frank Carlson—were Slingerland loyalists. Gene Krupa wasn’t getting the votes from the Down Beat crowd by this point, but he was still the biggest star in the game; so much so that he eventually was able to negotiate a deal with Slingerland to collect cash royalties off every drum kit the company sold. The age of the megabucks celebrity endorsement deal had arrived.

A new era was soon to begin in the Slingerland offices, as well. The company’s longtime leader H. H. Slingerland died in 1946, putting Walter Slingerland in the president’s seat after three decades as his brother’s right hand man. By 1952, H.H.’s son H. H. Slingerland, Jr.—better known as “Bud”—took over the presidency following Walter’s retirement (Walter Slingerland, interestingly, became one of the early developers of the suburb of Schaumburg, IL in the 1950s).

Born in 1921, Bud Slingerland grew up alongside the family business, and while—like his father—he was more interested in selling instruments than playing them, he seemed to have inherited all the necessary business instincts for success when he took the reins at the age of 31. This included a baked-in distrust, or mild disdain, for the Slingerland family’s longtime rivals, the Ludwigs, whose WFL brand was beginning to catch up with them in sales in the 1950s.

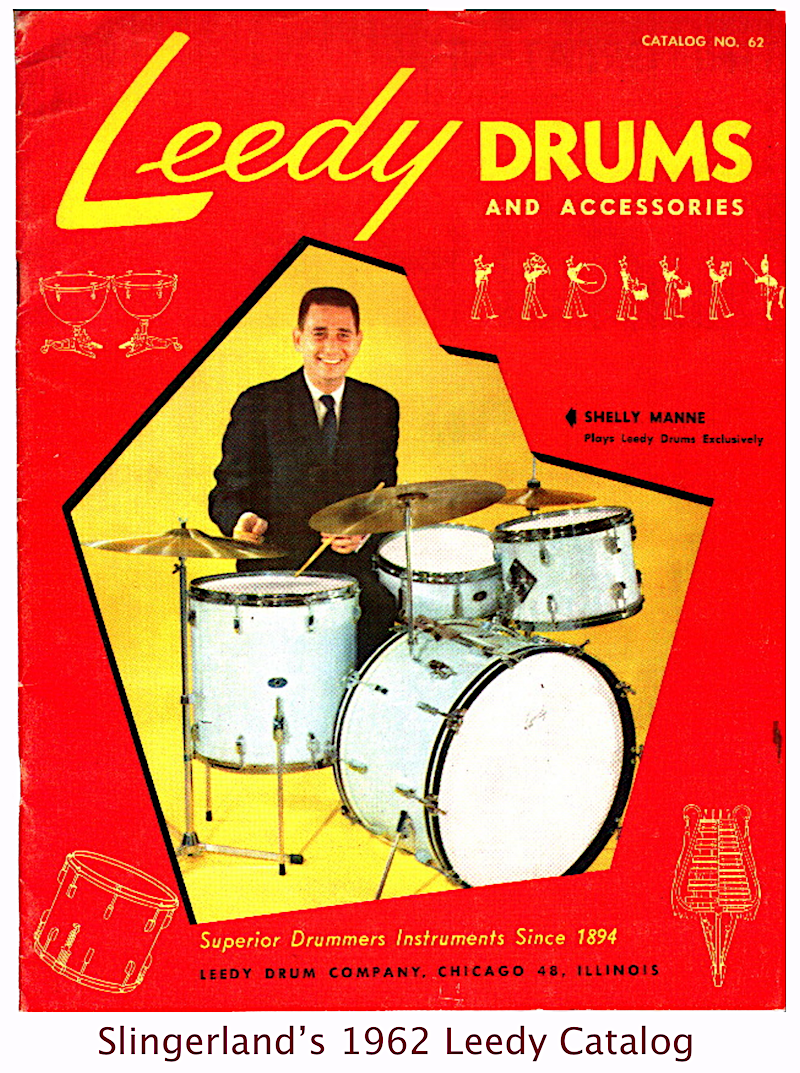

By contrast, the original Ludwig drum line, still under the ownership of the Conn Corp., was scuffling. As a consequence, in 1955, C. G. Conn made it known to the industry that both of its old percussion subsidiaries, Ludwig and Leedy, would be put up for sale, as Conn would be ending its drum-making efforts in Elkhart. Hearing this news, William Ludwig, Jr. swallowed some of his own pride and called up Bud Slingerland, suggesting they set aside their fathers’ old beef and purchase Conn’s drum inventory together, splitting the riches. Ludwig, of course, would get back the rights to his family’s original business and trademarks, while Slingerland would take over the product line of the similarly historic Leedy brand, which had its roots back in the 1890s.

Bud repeatedly traveled to Elkhart with Ludwig Jr. to negotiate the distribution of the acquired Conn stock. A successful deal was eventually reached, but in the aftermath, Slingerland made it clear to Ludwig that he didn’t necessarily wish his rival well. His stated goal, as legend has it, was to make Slingerland and Leedy the No. 1 and No. 2 names on the drum market. “Ludwig,” Bud said, “could have the third string.”

Slingerland’s vision didn’t quite play out that way in reality. Ludwig, with a helpful boost from Ringo Starr, exploded in popularity in the 1960s and ultimately became the more recognized of the two famous Chicago drum brands. Slingerland was no slouch in the ‘60s either, however, as the company’s move to its larger plant in Niles at the start of the decade led to some of the best sales numbers in its history. Its Leedy products, though, never quite gained traction, and were eventually abandoned.

Slingerland’s vision didn’t quite play out that way in reality. Ludwig, with a helpful boost from Ringo Starr, exploded in popularity in the 1960s and ultimately became the more recognized of the two famous Chicago drum brands. Slingerland was no slouch in the ‘60s either, however, as the company’s move to its larger plant in Niles at the start of the decade led to some of the best sales numbers in its history. Its Leedy products, though, never quite gained traction, and were eventually abandoned.

In terms of innovation, Slingerland never quite earned the same reverence from drum enthusiasts as Ludwig, probably because the latter was constantly suing the for former for patent infringement. No one questioned Bud Slingerland’s business acumen, but his motivations were usually more about giving the customer what they wanted, rather than imagining the thing the customer hadn’t yet realized they wanted.

“Bud was not what I would call a leader in the industry,” former associate William Connor told Slingerland historian Rob Cook in 1996. “He was a follower. If somebody came up with something new, he’d develop his version of it.”

[Views inside the new Slingerland plant at 6633 N. Milwaukee Ave. in Niles, IL, 1960s]

Part IV: Ever Changing Rhythms

“Making fine drums is an art. At Slingerland, it’s the state of the art. Because Slingerland will always be lending its ear to the greater expert on drums. The artist.” –Slingerland catalog, 1979

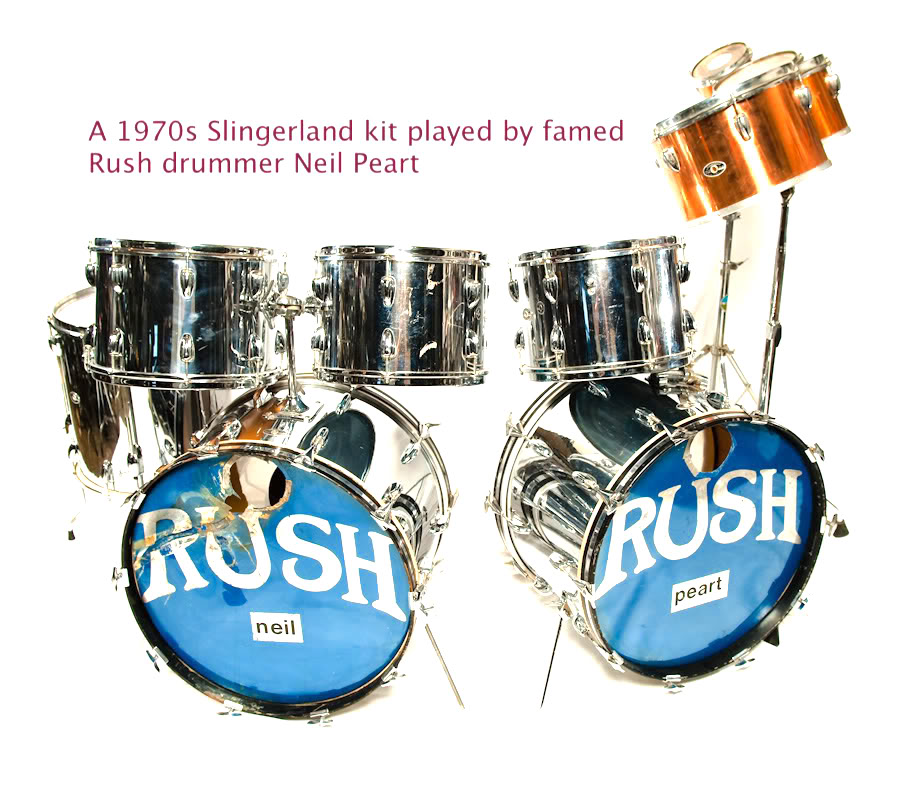

By the late 1960s, Bud Slingerland’s involvement in the day to day operations of the business had been considerably reduced; a 1991 Buddy Rich biography even refers to Bud as “the absentee owner” of the Slingerland Drum Company during this period. The man in charge, instead, was Don Osborne (b. 1928), a former well-known Chicago jazz drummer who’d joined the sales department for Slingerland in the mid ‘50s and had now risen to the role of vice president. He was joined in Niles by plant manager Bill Kelley, who later gave way to Warren Meyers in the mid 1960s. With far more actual playing know-how than Bud Slingerland, Osborne was able to keep the company on the cutting edge through the ‘60s, maintaining its jazz and drum corps following while welcoming the new legion of drummers inspired by the birth of rock n’ roll.

Naturally, with the 1970s approaching, the familiar tale of cheaper, foreign-made products blowing up the marketplace was certainly on the horizon, but whether he anticipated that doom or simply liked the idea of an early retirement, Bud Slingerland put the family business up for sale in 1970, well in advance of any downturn in its profits. He was only 48 years old at the time.

Naturally, with the 1970s approaching, the familiar tale of cheaper, foreign-made products blowing up the marketplace was certainly on the horizon, but whether he anticipated that doom or simply liked the idea of an early retirement, Bud Slingerland put the family business up for sale in 1970, well in advance of any downturn in its profits. He was only 48 years old at the time.

The eventual purchaser, the publishing conglomerate Crowell, Collier & MacMillan, seemed like an odd match perhaps, but the same growing media company had already acquired the old Conn musical instrument business a few months earlier, and so the only remaining question was whether Slingerland would retain its Chicago plant or be absorbed into Conn as Ludwig once had 40 years earlier.

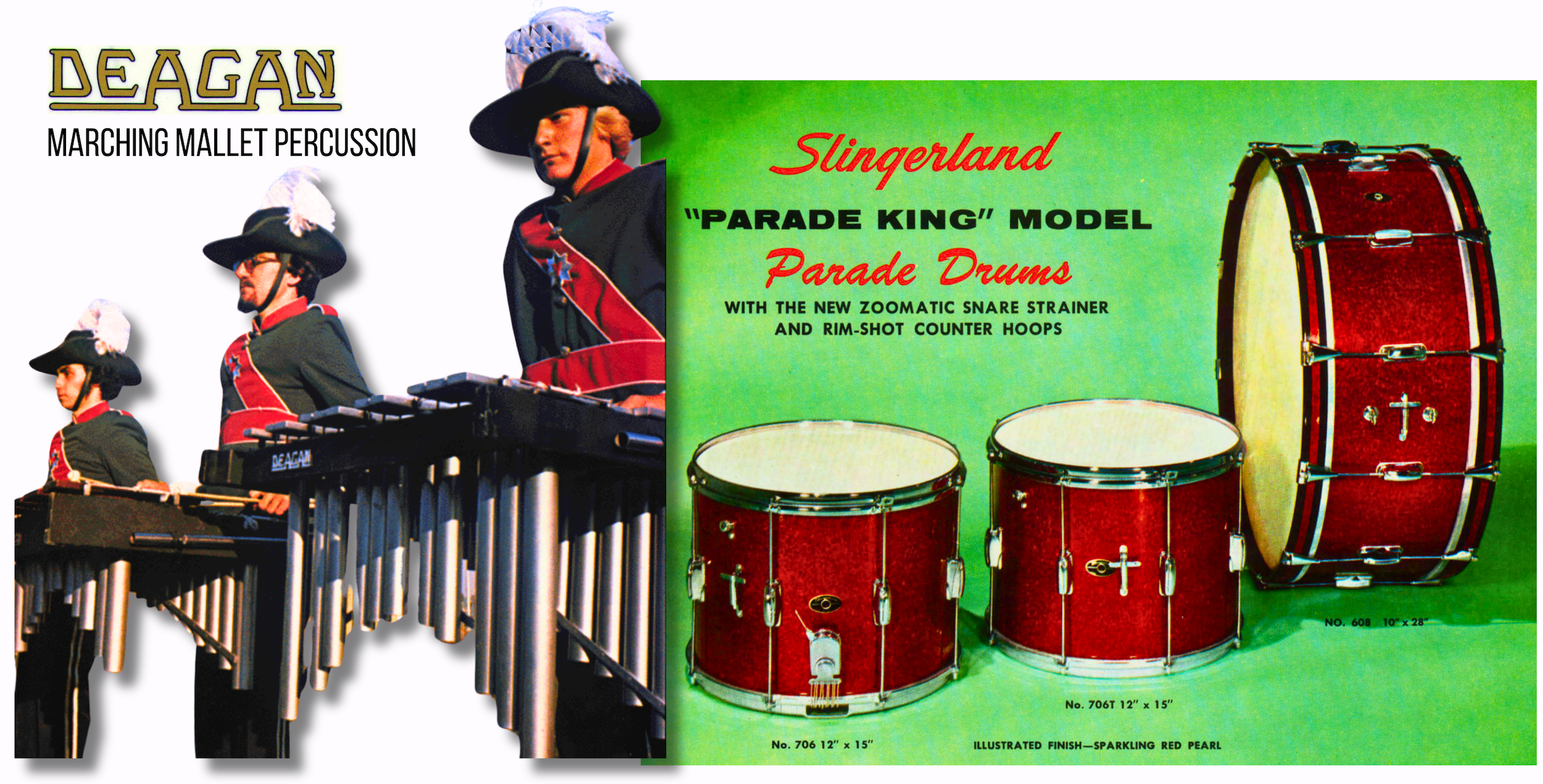

To the joy of Slingerland’s Chicagoland workforce, news came that not only would the Niles facility remain in use; it would receive a new expansion. Against all odds, that investment paid off. Despite more patent lawsuits from Ludwig, instability in Macmillan’s corporate structure, and the abrupt dismissal of Slingerland’s president Don Osborne, the company still managed to hit record sales numbers at the end of the decade. In 1977, they also acquired another Chicago percussion institution, the J. C. Deagan Company—a world leader in the manufacture of bells and mallet instruments.

By now, the drum corps / marching band markets were the biggest segment of Slingerland’s business. Maintaining that viability into the 1980s, however, would require strong leadership to fend off not just the industry’s top dog, Ludwig, but a rapidly growing influx of Japanese competition. Unfortunately, while the company still had plenty of expert salesmen and craftsmen on the payroll in Niles, the structure of the business—as one cog in the machine of an easily distracted New York conglomerate—was suboptimal.

In 1980, just a decade into its experiment in the music biz, MacMillan sold all of its musical instrument manufacturing properties—including Slingerland, Conn, and Deagan—to one man, former Conn marketing director Daniel J. Henkin, for a cool $80 million. Henkin re-organized these companies under the revived tent of C. G. Conn, Ltd., and made it known that his grand plan was to relocate all of their far-flung operations back to Elkhart, Indiana. It didn’t quite play out that way, though, and by 1984, Slingerland and the now 70,000 square foot Niles plant were sold yet again, this time to the Sanlar Corporation. By this point, there were only 60 full-time employees on the Slingerland payroll.

Within two years, the Slingerland Drum Co. had folded and the Niles plant had shut down after nearly 30 years in operation. The Chicago era of Slingerland—and its existence as a true company with ties to its roots—had concluded. As tends to happen with a much-loved trademark, though, this was far from the end of the Slingerland brand, as it has subsequently passed through a gauntlet of well-known and well-meaning owners. Gretsch gave way to Gibson, which introduced new lines of Slingerland drums in the ‘90s, but then sold off its entire stock after its own bankruptcy in the 2010s. The independent DW Drums purchased the rights to the Slingerland name from Gibson in 2019, and in 2025—with DW now owned by the Roland Corp—another Slingerland revival was announced . . . a little over 100 years after H. H. Slingerland got his first factory up and running. The new kits, presumably, will be built at DW’s plant in Oxnard, California.

Sources:

The Slingerland Book, by Rob Cook, 1996

“Violin Classes Succeed” – The Inter Ocean, Aug 23, 1908

“Slingerland Triumphs in Drum Craftsmanship” – Metronome, July 1928

“The Book Publisher Who Owns Gump’s” – San Francisco Examiner, July 7, 1978

“MacMillan Sells Musical Instruments Firms to Former Music Exec” – Chicago Tribune, Sept 9, 1980

“Modern Music Man has Real Conn Jobs for Elkhart” – Chicago Tribune, April 29, 1981

“New Owner of Niles Drum-Maker” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 23, 1984

“Reminiscing with William F. Ludwig, Jr.” – Modern Drummer, Sept 1987

Love the website. Thanks for your work.

The original Slingerland factory was at 1815 N. Orchard St. (1813-1815, to be precise.) They moved to Niles after the death of the founder (H.H. Slingerland) in the 40’s. The original factory site survives, and has been chopped up into condos. I have some old catalog ads with the address and renderings of the factory that I can e-mail you if you’d like. I also own a gorgeous May Bell Banjolele, produced by Slingerland before they got in the drum business. Happy to send you a snap of that, too. Thanks again for the great site.