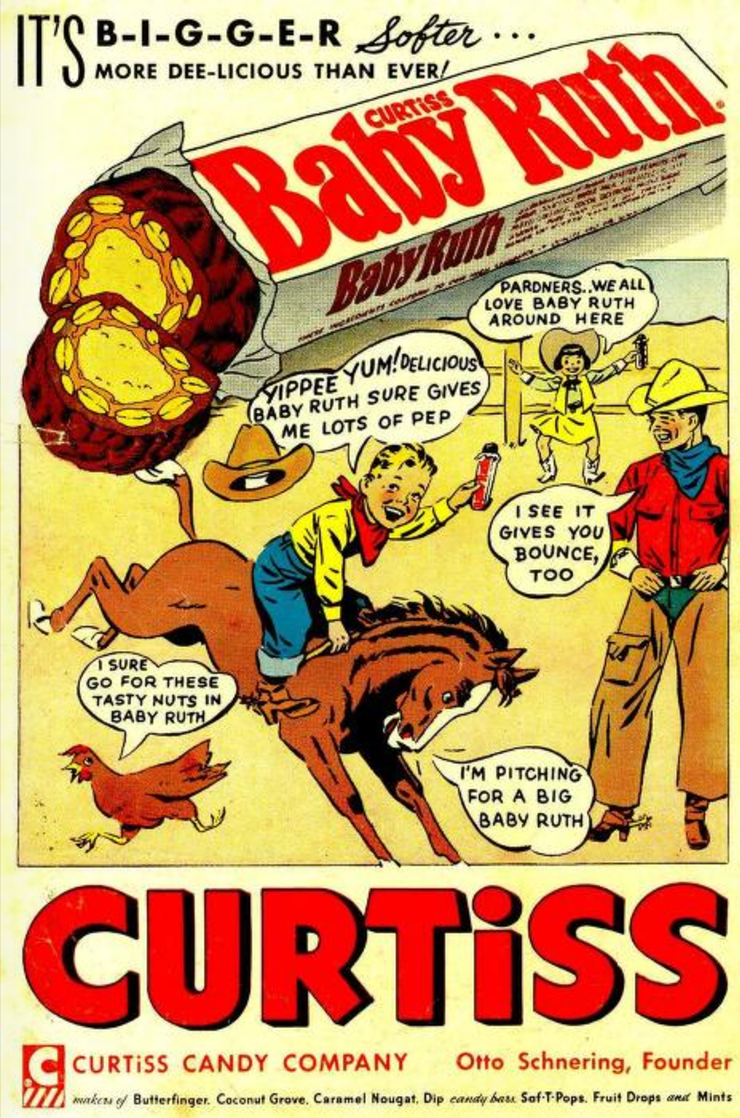

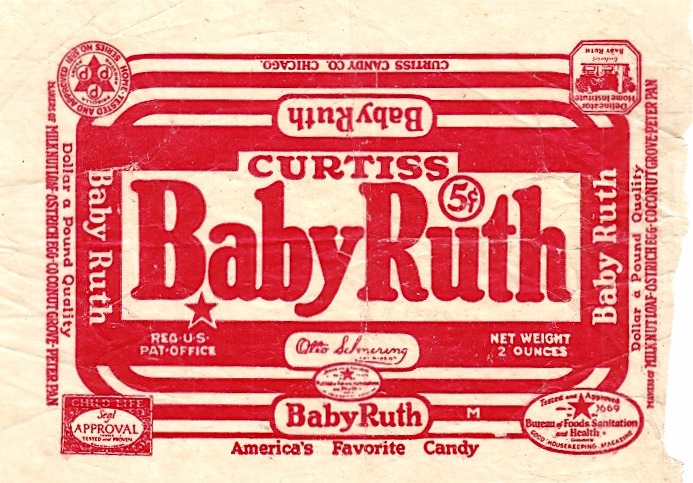

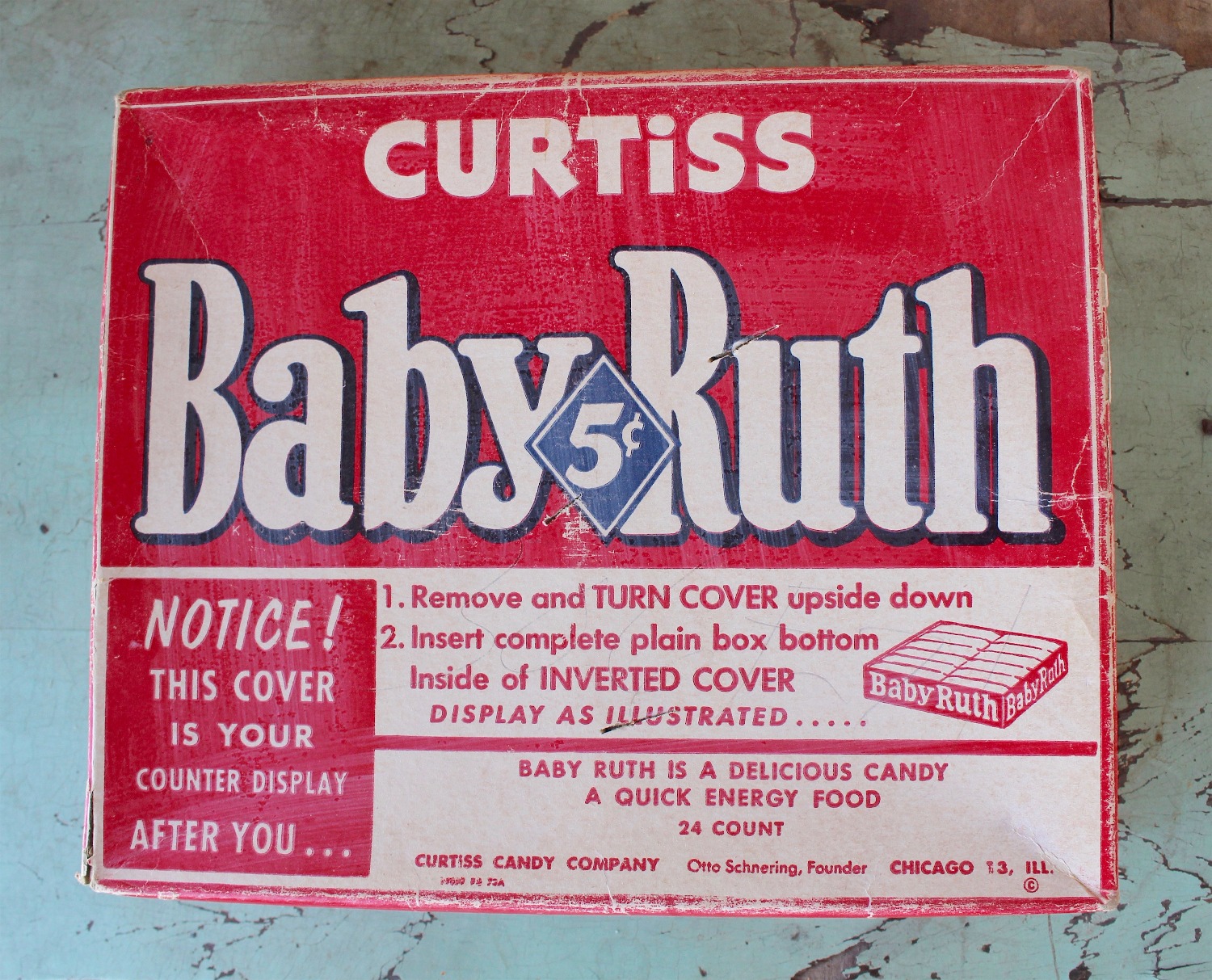

Museum Artifact: Baby Ruth Display Box, c. 1950s

Made By: Curtiss Candy Company, 337 E. Illinois St., Chicago, IL [Streeterville]

“There was never a crack in the integrity of Otto Schnering.”

In 1953—right around the same time the vintage Baby Ruth display box in our collection was made—radio host and author Henry J. Taylor went on the air and delivered a stirring speech / eulogy for the man they used to call the “Candy Bar King.” Taylor was a former business associate and longtime friend of Otto Schnering, the late founder and president of Chicago’s Curtiss Candy Company.

In the days after Schnering’s death, most journalists took note of the man’s great business savvy—his shrewd marketing campaigns, the invention of the five-cent candy bar, the wild success of the Baby Ruth brand, and the development of one of the nation’s first truly self-sufficient farm-to-factory operations. For Taylor, though, Schnering was far more than a rock star of capitalism.

In the days after Schnering’s death, most journalists took note of the man’s great business savvy—his shrewd marketing campaigns, the invention of the five-cent candy bar, the wild success of the Baby Ruth brand, and the development of one of the nation’s first truly self-sufficient farm-to-factory operations. For Taylor, though, Schnering was far more than a rock star of capitalism.

Taylor titled his radio address “Integrity: A Mighty Force,” and held up his dearly departed friend Schnering as a shining example of American exceptionalism as it related to personal character, rather than profit making. To communicate his point, he focused primarily on one incident—the financial panic of 1929—and how Schnering piloted his business through its darkest hour.

“I cannot tell you this story in an impersonal way because I lived through it,” Taylor told his listeners, recounting a Curtiss Candy Co. creditors meeting held on May 28, 1929. This was months before the famous stock market crash of Black Tuesday, but immediately after a similarly devastating crash in the world commodity markets. Because Otto Schnering had poured most of his profits right back into the operations of his company, he couldn’t pay his growing debts, and the Curtiss Candy empire was suddenly on the brink of bankruptcy.

“I myself had started a business of my own,” Taylor said, “and eventually sold large quantities of supplies to the Curtiss Candy Company. Almost everything I had was tied up in its integrity. That’s the point—it’s integrity.

The creditors’ meeting was held in the ballroom of Chicago’s Belmont Hotel—on a dull grey afternoon, as ominous outside as in the tense, packed atmosphere of that room.

Schnering was told not to come to that meeting. He was excluded, as was every member of the management team. Told to remain in the nearby main office and await the decision of bankruptcy, they were asked to wait there for news of who would succeed Schnering—take over the business built through a decade by men and women whose very success in increasing the business was about to break them, wash out their money and their hearts, and oust them from their jobs.

Up in the ballroom a decision had been reached by the creditors’ meeting. The machinery would be sold. Dismissal notices would go to all employees. Any remaining debts would be abandoned as worthless. The company was through.

Then an amazing thing happened on the floor of the meeting. A man got up and made a little speech. What he said was not remarkable. The remarkable thing is what happened all over the ballroom.

“The Curtiss business ceases to exist without Otto Schnering and his loyal team,” he said. “Any credit extended was extended to that management, not to some inexperienced committee. I have talked with Otto Schnering on this very day. Schnering said to me, ‘You know we can’t collect the amount due from our customers now. We can’t pay our bills. It may take years to pull through. But if everybody will wait and is willing to help, I can see this awful time through and I’ll dedicate my life to this job.’

“That statement,” the speaker went on, “is enough for me. The integrity of this business is the integrity of the people in it, the integrity of the management. I cast my lot with that integrity and with no other.”

The speaker got no further. There was a rumble across the floor. One man after another called “Order! Order!” Men were standing to speak in every part of the room—to speak up and stand with Otto Schnering and the integrity of the team.

The majority of the creditors voted to let Schnering stay in. It took 12 years to clear away the financial problem. Day by day, month by month, year by year, dollar by dollar. From 8 in the morning until 8 at night—10 at night, 12, 1, 2, 3. No letup, no security for Schnering and his associates. Each day simply meant a chance for those men to take each problem, hour by hour, and see it through. Never was a payroll missed—never a penny defaulted.

. . . The Curtiss Candy Company lived through everything and paid off every debt. The team won. Integrity won out—and nothing else but.”

–Henry J. Taylor

Taylor went as far as to claim that Otto Schnering had “given his life” to the challenge of serving his clients and employees faithfully, contributing to his relatively early death at the age of 62. With the addition of modern-day cynicism, there is admittedly something instantly suspicious about the notion of a truly self-sacrificing industrialist. But most accounts of Schnering paint at least a broadly similar picture of a decent man—obsessively driven, but decent nonetheless.

The Candy King once described his ongoing goal of making Curtiss “a company with a soul, having the benefits of its employees at heart,” and aside from a few grievances from the teamsters, the thousands of men and women who worked for Schnering over the decades seemed to buy in to his philosophy.

[Curtiss Candy Co. founder Otto Schnering (left) pictured with the ribbons and trophies won by the prize cattle, pigs, and sheep from the Curtiss Farms, northwest of Chicago, c. 1950]

[Curtiss Candy Co. founder Otto Schnering (left) pictured with the ribbons and trophies won by the prize cattle, pigs, and sheep from the Curtiss Farms, northwest of Chicago, c. 1950]

History of Curtiss Candy Co., Part I: Before He Was King

Otto Schnering was born in Chicago in 1891, son of a German-born father, Julius, and an American mother—Helen Curtiss—who came from a well-to-do New England family. Schnering would later name his upstart candy company after his mom, supposedly as a loving tribute. But it likely also had a lot to do with the reduced marketability of a German name like Schnering during the middle of World War I. Strategic branding, it turned out, would be a lifelong talent.

From 1909 to 1913, Otto attended the University of Chicago, earning a degree in philosophy. It’s a bit of an unorthodox educational background for a candy mogul, perhaps, but it’s not hard to see how a philosopher’s perspective contributed to Schnering’s later exploits more than a traditional business degree might have.

While at U of C, Otto also enjoyed one of his first successful forays into the world of project management, as he and a couple of his Psi Upsilon frat brothers personally led a planning and fundraising campaign to build a new chapterhouse across from the Bartlett Gymnasium. They completed most of the ambitious project during the span of their undergrad years, and the building—located at 5639 S. University Ave.—is still serving the same purpose 100 years later.

After college, Otto spent a few years as a retail manager for the George P. Bent Piano Co., makers of the “Crown” piano line. The gig also led him to his first wife, George Bent’s daughter Dorothy.

After college, Otto spent a few years as a retail manager for the George P. Bent Piano Co., makers of the “Crown” piano line. The gig also led him to his first wife, George Bent’s daughter Dorothy.

Mr. Bent passed down his knowledge of 20th century salesmanship, which nicely complemented the more traditional German business principles Otto had learned from his father—a longtime Chicago jeweler.

When the Bent Piano Company was bought out in 1916, Otto Schnering—now 25—wasted little time taking the lead in a new venture. He formed the United Sales Company for the purpose of promoting “food products and extracts” (Gas Age, vol 60)—a marketing field that offered a little more flexibility than oversized musical instruments.

As an example of his early work, Schnering devised an ad campaign for Chicago’s Sloat Baking Company, promoting its cheap macaroon-like treat, “Amerones.” Other agencies had dodged the product entirely, but Otto Schnering instantly saw a way to promote the snack as something that was new and exciting while still appealing in its familiarity—basically, it could be compared to a macaroon without being inferior in its affordability.

“By making this comparison,” Schnering told Printer’s Ink in 1917, “we simply aim to place Amerones in the reader’s mind. As soon as our advertising gets under way, this comparison will be dropped and the product will be placed on its own feet.”

“To add human interest to the copy,” Printer’s Ink noted, “[Schnering] has invented two trade characters, which will be known as the ‘Amerone Children.’ In the first full-page announcement, the children were used to introduce the product, and they will be used in other copy along similar lines.”

“To add human interest to the copy,” Printer’s Ink noted, “[Schnering] has invented two trade characters, which will be known as the ‘Amerone Children.’ In the first full-page announcement, the children were used to introduce the product, and they will be used in other copy along similar lines.”

“Let the children eat them,” urges one ad. “All children like them and they are really good for them. Give them all they want when they come home hungry from school or play.”

That’s another thing Schnering was always adept at—making snack time sound like a good fitness decision. Over the top or not, the Amerone campaign was a home run, and the industry was on notice.

During the same period, in one of those fateful, fruitful bits of company lore, an old friend of Schnering asked him to consider buying some budget-priced candymaking equipment to help a failed candyman out of a financial jam. Schnering, realizing that promoting his own food products could be considerably more cost-effective than promoting other people’s, took up the offer and went to work in the sugar snack biz.

It Takes the Kake

The Germans had a reputation as masters of the chocolatiering arts, but as to the origins of Otto Schnering’s early confection inventions . . . his formulas seemed less rooted in tradition, and more in experimentation. Mass-produced chocolate bars were a fairly recent phenomenon in America—pioneered by Pennsylvania’s Hershey Company—and the expanded potential of the multi-ingredient “candy bar” was yet to be fully explored.

Young Otto got started—again according to company myth—with nothing more than a single five-gallon kettle inside a small office in the back of a hardware store at 3256 N. Clark Street. When he upgraded to a larger office, it was still a cramped space on the second floor of a building at 3222 N. Halsted, with just four employees—all women—on staff.

Young Otto got started—again according to company myth—with nothing more than a single five-gallon kettle inside a small office in the back of a hardware store at 3256 N. Clark Street. When he upgraded to a larger office, it was still a cramped space on the second floor of a building at 3222 N. Halsted, with just four employees—all women—on staff.

Picking the right combination of ingredients was one thing; finding a customer base was something else. Fortunately, Schnering already believed he could sell ice to the Eskimos.

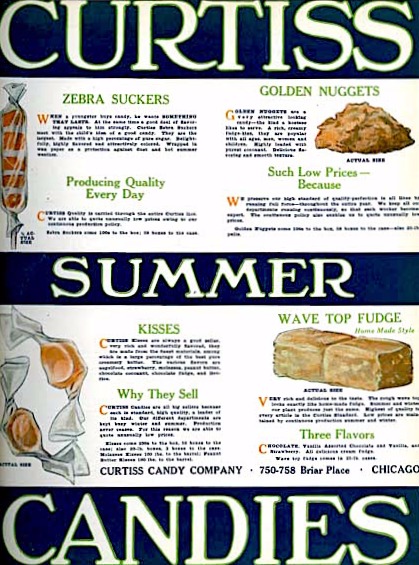

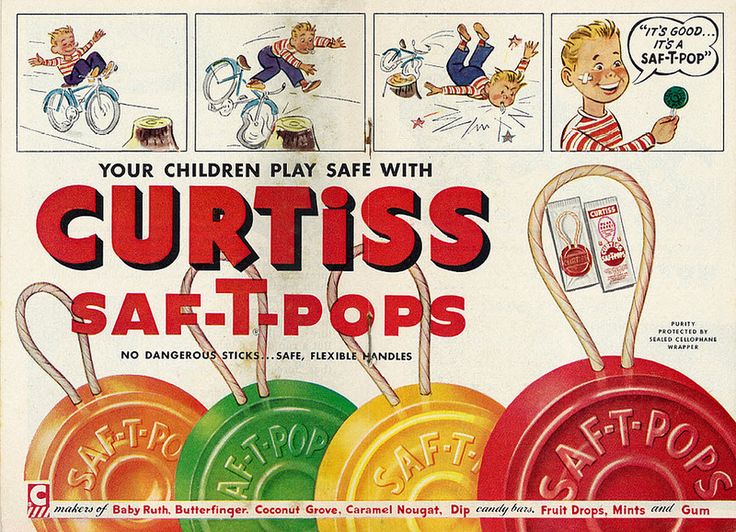

In short succession came the original line-up of Curtiss confections—the Polar Bar, the Vanilla Coconut, Jolly Jacks, Marsh-O-Nut Dipp, and the Honey Comb Chip, along with dozens of other more generic offerings—butter rolls, Italian cream fudge, zebra suckers, golden nuggets, and marshmallow bananas:

“Schoolday treats and schoolday feasts—what boy or girl fails to include Marshmallows and Bananas? Old favorites, both, and because of the attractive combination of chew-y Marshmallow and rich, delicious Banana flavor, Curtiss Marshmallow Bananas are universally popular.”

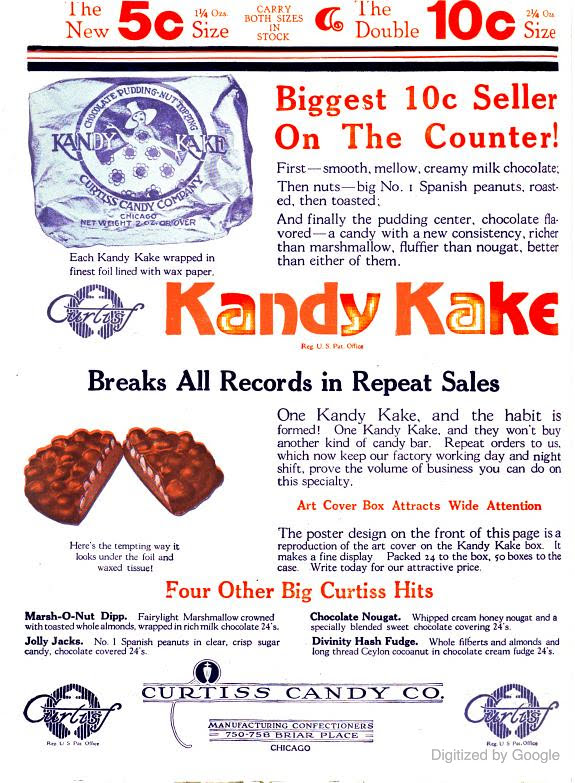

In some respects, Schnering was just throwing stuff at the wall and literally seeing what would stick. But by putting a large chunk of his profits right back into promotions, he was gradually separating himself from the legions of other upstart Chicago candy makers at the time. By 1919, Curtiss was producing its first breakout hit—the Kandy Kake—one of the country’s first widely known chocolate & peanut combination bars.

⇒ First—smooth, mellow, creamy milk chocolate.

⇒ Then nuts—big No. 1 Spanish peanuts, roasted, then toasted

⇒ And finally the pudding center, chocolate flavored—a candy with a new consistency, richer than marshmallow, fluffier than nougat, better than either of them.

⇒ One Kandy Kake, and the habit is formed!

While it was well advertised and presumably pretty tasty, the Kandy Kate’s rise was really spurred on by the return of World War I soldiers, many of whom had been introduced to the wonders of candy bars as part of their rations overseas. With demand seemingly doubling by the day, the Curtis Candy Co. ballooned rapidly to more than 125 workers in 1919 and relocated to a new three-story, 37,000 sq. foot plant in Lakeview at 750 W. Briar Place. Otto Schnering, who’d still been making many of his own candies by hand months earlier, was now a legitimate CEO. He even hired his dad as his first company treasurer.

The Briar Place plant didn’t just offer more space, it gave Schnering an opportunity to create the hyper-efficient candy-making complex of his German dreams. There were “monster peanut roasters, cooking kettles, open fire mixers, endless conveyor systems, and chocolate slab and bar breaking equipment,” Gas Age reported, “the majority of which were designed by Otto Y. Schnering, president of the company.”

How did a philosophy major also develop the mechanical genius to produce such wonders? Another mysterious element of his legend, I suppose.

The factory also became one of the biggest users of gas power in the city at the time, and kept operations going smoothly during the hot summer months with climate control and refrigeration.

“Curtiss quality in all lines carries out the Curtiss slogan: Makers of the Best,” read a 1919 ad. “This high standard never varies. Production never varies. Summer and winter our entire working force are occupied. This fact accounts for our exceptional low prices.”

Yes, the fledgling chocolate industry had generally been an autumn-to-spring game up until this point, but with the “melting conundrum” now conquered by the glorious machinery of man, the Curtiss Candy Company was seizing on a moment. And Otto Schnering still had his biggest home run swing yet to come.

II. It’s Not The Babe, It’s a Baby

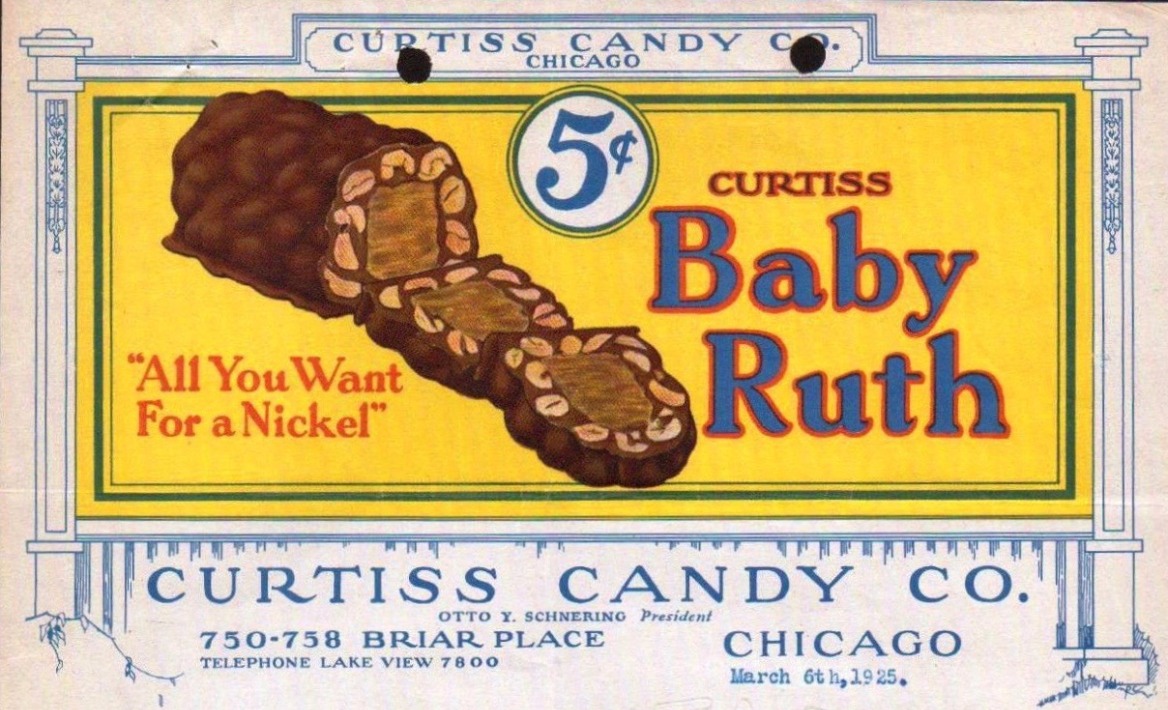

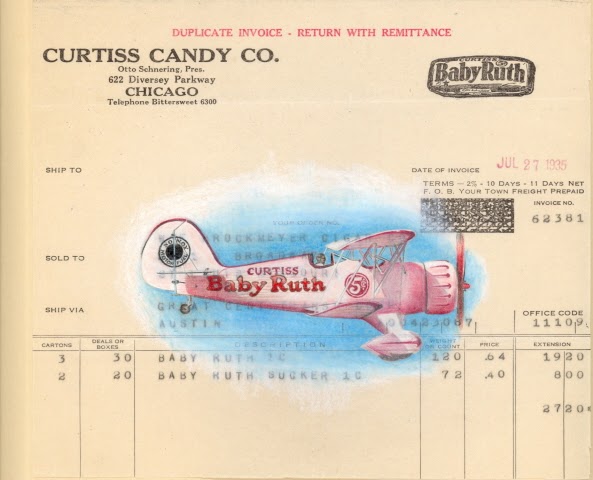

At the outset of the Prohibition era, when 10-cent candy bars ruled the marketplace as the country’s new favorite vice, Otto Schnering soon decided that undercutting the competition with a 5-cent bar could spell ultimate commercial victory. To ensure the strategy’s success, though, he wanted to feel a bit better about his flagship product.

And so, a two-part plan was developed. First, a 5-cent version of the Kandy Kake appeared as a means of testing the market. Then, for phase two, the Kandy Kake was essentially re-launched in a new form, with a longer, log-like shape and an eye-catching, red-and-white wrapper. It had a new name, too—a pop culturally familiar one at that.

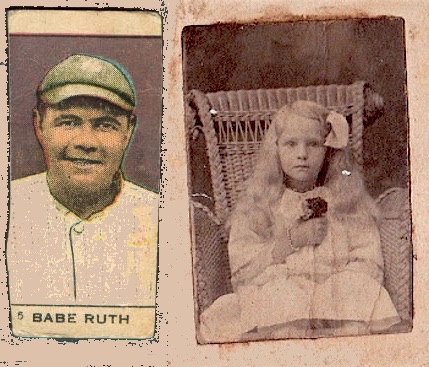

Believe it or not, candy historians are STILL debating the true origin of the name “Baby Ruth.” That’s because Otto Schnering went to his deathbed insisting that his inspiration had been the late daughter of former U.S. President Grover Cleveland. Born during Cleveland’s time in office (and just six days before Otto Schnering), Ruth Cleveland had been popularly known as “Baby Ruth” during the 1890s. She later died tragically of diphtheria in 1904 at the age of 12.

Paying tribute to the late first daughter isn’t an entirely implausible story, until you factor in the historical context of the Baby Ruth candy bar’s debut in 1921.

At a time when baseball was America’s most popular sport, George Herman “Babe” Ruth had become THE sports celebrity of the moment—a Paul Bunyan-esque folk hero in the flesh. Between 1919 and 1921, as the Curtiss team was working on its 5-cent candy bar rebranding plan, Babe Ruth evolved from a star pitcher for the Boston Red Sox into a prolific power hitting outfielder for the New York Yankees—absolutely shattering the Major League record book with 54 home runs in 1920 (no other man had ever hit more than 27) and then besting himself in 1921 with a staggering 59 deep flies. The entire country took notice, with even non-baseball fans finding it impossible to avoid Ruth’s gregarious grinning mug in every newspaper and magazine. THIS was the world into which Otto Schnering introduced his Baby Ruth candy bar.

By some accounts, the Curtiss Company had initially reached out to the Sultan of Swat directly, asking him if he’d be interested in lending his name and likeness to their new product, something Ruth did for everything from cereal to cigarettes in the ’20s. When the Babe’s asking price was too high, however, Schnering took a sideways approach, almost certainly concocting the Ruth Cleveland story as a legal loophole to capitalize on the name of the most famous man in America. Years later, when Babe Ruth actually did endorse a different candy bar under his own name, Schnering’s original scheme proved so airtight that he was able to file a copyright infringement lawsuit against the George H. Ruth Candy Co. for selling a product too similar in name to the established Baby Ruth bar. Now that’s just straight-up gangsta—in a confectionery sense.

By some accounts, the Curtiss Company had initially reached out to the Sultan of Swat directly, asking him if he’d be interested in lending his name and likeness to their new product, something Ruth did for everything from cereal to cigarettes in the ’20s. When the Babe’s asking price was too high, however, Schnering took a sideways approach, almost certainly concocting the Ruth Cleveland story as a legal loophole to capitalize on the name of the most famous man in America. Years later, when Babe Ruth actually did endorse a different candy bar under his own name, Schnering’s original scheme proved so airtight that he was able to file a copyright infringement lawsuit against the George H. Ruth Candy Co. for selling a product too similar in name to the established Baby Ruth bar. Now that’s just straight-up gangsta—in a confectionery sense.

As time passed, even the Curtiss Candy Co.’s official version of the Baby Ruth origin story started to change, as Schnering’s simple explanation took on a life of its own. In the 1950s and ‘60s, corporate histories mixed in wildly false claims—including a supposed occasion in which young Ruth Cleveland personally visited the Curtiss factory (she died 12 years before it opened). Perhaps fearing retroactive legal implications, the company continued to deny any connection between Baby Ruth and Babe Ruth, as well, claiming that the baseball star wasn’t even famous yet when the candy bar was first sold—again, blatantly untrue.

Anyway, despite all the evidence to the contrary, many books and articles on the subject still give Schnering’s Ruth Cleveland story the benefit of the doubt. Nearly 100 years on, and over 50 years since the end of the Curtiss Company itself . . . Otto’s clever marketing alibi survives.

“We named our leader Baby Ruth because that name would appeal to young and old alike,” Schnering said in 1927, noting that neither the name nor the nickel price ensured a slamdunk success. “It was freely predicted that our none-too-strong company would fall in our effort to market a bar at a nickel. More than once that prediction almost came true. [Baby Ruth] was a good piece of merchandise, but it did not sell at first. Such advertising as we were able to do for it failed to achieve any noteworthy results.” Fortunately, Schnering wasn’t deterred by a slow start out of the gates.

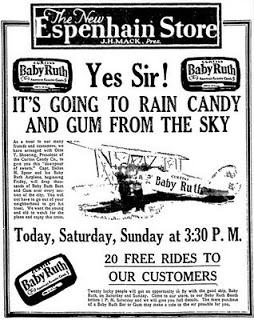

III. The Great Big Promotion in the Sky

Sometime likely in 1922, Schnering approached a local Chicago advertising executive named Eddy S. Brandt, seeking his help in creating a whole new type of promotional strategy for his prized new product.

“I have a candy bar that I want you to advertise,” Schnering said, as Brandt later remembered to the Tribune. “I think it will knock Oh Henry out of the market. It’s called Baby Ruth and I can sell it for a nickel.”

At the time, the 10-cent Oh Henry!—a chocolate-and-peanut bar produced by the Williamson Candy Co.—was the top selling candy bar in Chicago. Gold standards like the Hershey bar and upstarts like the Milky Way (by Chicago’s Mars Inc.) were also popular but priced at 10 cents, as well. Accordingly, Eddy Brandt launched the Baby Ruth’s new ad push with a proper slogan: “All You Want For a Nickel.” His agency also developed new display boxes to entice dealers to stock their countertops, and placed four-color ads in major national publications like Saturday Evening Post and Collier’s.

The first wave of the campaign proved an enormous success, and by 1924, Curtiss was moving 1.5 million units PER DAY, forcing much of the industry to change its price system to keep pace. Schnering smelled victory, but he went the extra mile to ensure it, personally joining his national sales team in its efforts to spread the Baby Ruth word, grass roots style; boots on the ground. He also doubled down with the Brandt Ad Agency, investing even more money into increasingly bombastic promotions.

[Doug Davis with one of the Baby Ruth “Flying Circus” planes, c. 1924]

[Doug Davis with one of the Baby Ruth “Flying Circus” planes, c. 1924]

The Baby Ruth logo was plastered on billboards and barns, and took on visible sponsorships at circuses, horse races, and any other gathering of eyeballs and mouths. In arguably the campaign’s most famous stunt, the noted racing pilot Doug Davis was hired to perform aerial tricks and drop parachuting Baby Ruth bars from his bi-plane over downtown Pittsburgh. The event was so successful that Schnering repeated it in dozens of other cities, organizing a “Baby Ruth Flying Circus.”

“Outside of keeping up the quality of Baby Ruth,” Schnering later told Printer’s Ink, “nothing helped us more to get a start than free deals. For a time we went through a period of feverish merchandising when it was necessary to press hard for the distribution we wanted. We used free deals and gave special and extra discounts for quantity orders. . . . They were tremendously important in our merchandising growth.”

A campaign of this magnitude was obviously not cheap. But Schnering remained devoted to his belief that his profits were better utilized when funneled back into the business, rather than padding his own coffers.

A campaign of this magnitude was obviously not cheap. But Schnering remained devoted to his belief that his profits were better utilized when funneled back into the business, rather than padding his own coffers.

By 1928, Baby Ruth was the top selling candy bar in the country, and many other candies and gums in the Curtiss arsenal carried the same Baby Ruth brand name for optimal exposure.

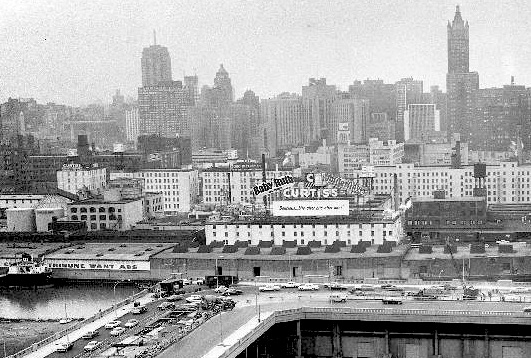

In total, the Curtiss Candy Co. now employed more than 3,000 Chicagoans along with various national salesmen and distributors. Brand new offices were purchased in Lakeview at Broadway and Diversey, and the production efforts expanded to three major factories. With the Briar Place plant pushed to its max, two additional facilities were up and running in Streeterville, at 311 and 337 E. Illinois Street, just north of the Chicago River and the Ogden Slip, and east of the Tribune Tower. In short order, large Baby Ruth and Butterfinger signs were attached to these buildings, remaining familiar sights downtown up into the 1960s.

[The Curtis Candy factories on E. Illinois St., c. 1950s]

[The Curtis Candy factories on E. Illinois St., c. 1950s]

Like most other companies riding the wave of boundless optimism in the 1920s, Curtiss seemed headed strictly in one direction. Even Otto Schnering’s personal life was on an upswing. After a difficult divorce from his first wife Dorothy during the early days of the company, he soon remarried (another Dorothy, no less) and eventually adopted his new bride’s young children as his own, welcoming them into the Curtiss hierarchy when they came of age.

Of course, as described in Henry Taylor’s radio address, more difficult times did soon arrive. But since nothing cures the blues like chocolate, a Great Depression surely was no match for the Curtiss Candy Company.

[Baby Ruth advertisement from 1939]

[Baby Ruth advertisement from 1939]

IV. “Red Blooded Fighting Men & Women”

Once Otto Schnering was given the stamp of approval by his creditors in 1929, he proved he was up to the task of paying off the company’s debts without slowing down its exponential growth. The Butterfinger bar, Curtiss’s second major candy bar smash, kept the factories firing on all cylinders even during the roughest years of the Depression.

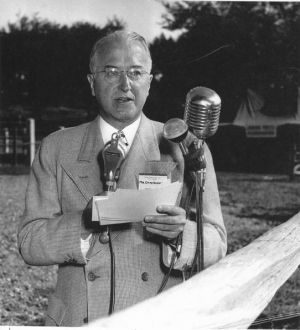

In 1933, Schnering traveled to Washington D.C. to testify during a House Committee debate on a proposed 30-hour work week—a plan that would presumably help bring more unemployed Americans back into the workforce. Schnering didn’t support the plan, and instead, took the opportunity to share his own blueprint for success—creating arguably the most political five minutes of his generally a-political career.

“I have the privilege of representing a business employing directly about 6,000 people and indirectly about 25,000 more people,” he said, adding that 5,000 new employees had been added in the past year alone, with more on the way.

“Our company is shipping between 15 million and 18 million pounds of finished products per calendar month, which give the railroads at our present rate, an annual revenue of $1,500,000, on our freight alone and approximately another $1 million in freight on raw materials. …As the business is running, the Federal Government will get a very large corporate income tax. In addition to this, several thousand employees who would be out of work and living on charity will, as a result of this successful operation, pay the Federal Government substantial income taxes.

[Otto Schnering speaking his mind]

[Otto Schnering speaking his mind]

“By now, you are wondering what business this could be which has had such a remarkable success in the past 10 months, which period is judged by experts to have been the worst 10 months in our history. This company, employing this vast army of people, is the Curtiss Candy Co. of Chicago. [you can imagine Schnering pausing here for dramatic effect]…The products that this company manufactures are sold under the brand names of Curtiss, Baby Ruth, Butterfinger, Buy Jiminy, Dip, and several others. These are all products that sell for 1 cent per package, 2 cents per package, and 5 cents per package. They are products manufactured for the masses.

“You are wondering how, during this period of extreme depression, has this company been successful, and if this company has found a formula for success in these times, what is it, and why cannot this formula be used by many enterprises.

“This unusual success is due to the following:

1. New ideas: The entering of a new price field last June—the 1-cent field. For the first time in the history of the candy business the American people were given a quality product and a generous size, wrapped exactly as 5-cent and 10-cent bars are wrapped, under known trade-mark names, for the lowest media of United States exchange—1 cent. This company entered this field knowing that all experts said that this product of unheard-of value could not be made at a profit and furthermore, that it would kill the established 5-cent business of this company. You will be interested in knowing that the results have been just the opposite in both of these regards.

The masses, both children and adults, had pennies and plenty of them and recognized that in these products they were being given products of true worth.

2. Greater values: Because of the response of the people to this new 1-cent line, we have been able to improve the quality of the 5-cent line also and to increase the size 33-1/3 percent.

Our courage in giving the consumer these outstanding values was repaid by the consumer with such a volume that what appeared to be such an impossible undertaking has been turned into a profitable one.

3. Expansion of sales activity: Furthermore, instead of intrenching and shrinking our sales force, it has been increased over 300 percent. In addition, we have increased our advertising appropriations an additional $1 million, thus helping to save from financial ruin, radio stations, magazines, printers, etc.

“Gentlemen, what industry needs today is less paternalism, less regulations, less restrictions—let each business go out today and stand on its own two feet. Is our country going to penalize a man and a company who has had the courage and willingness to work and to take a chance to help in this situation and favor the man who has marked time, intrenched and thereby increased unemployment?

“What this country needs to bring it back is more red-blooded fighting men and women, with courage, ideas, and willingness to serve through the making of new products, new values at new prices; in other words, be generous to the consumer, the great ‘boss’ of us all. More energizing and less theorizing will have to be done sooner or later by us all; so why not do it now and fight out way, as a country, out of this period of stagnation in the same way as the Curtiss Candy Co fought its way out with fully as many handicaps, if not more, than the Nation has today.”

The speech sounds a bit more Atlas Shruggy than compassionate, perhaps, but Schnering generally coupled his high expectations of people with a matching loyalty and vested interest in their happiness. This approach, in the long run, also served the company’s interests, as a happy work force meant fewer ugly labor disputes—a major concern of any Chicago business owner of the period.

[Curtiss Employee Marie Tabor working a Baby Ruth wrapping machine in 1939]

[Curtiss Employee Marie Tabor working a Baby Ruth wrapping machine in 1939]

V. The Gainfully Employed

By the 1940s, just about all Curtiss employees enjoyed paid vacations, options for pension plans and profit sharing, and company-provided health insurance and life insurance—which had not yet become a national norm. Both men’s and women’s salaries ($1.33 per hour and $0.90 per hour, respectively, in the mid 1940s) were also above the industry standard for confectionery workers—equating to about $15 per hour and $10 per hour in 2017 translation.

During World War II, Curtiss not only made treats for the troops, but also received kudos for its commitment to its employees fighting overseas.

“An example of what can be done by a company to let its men and women in the service know that they not only have something to fight for, but something to come back to, can be found in the Curtiss Candy Company of Chicago. Simply assuring the 750 employees of this firm that they will have jobs to come back to has not been enough to satisfy its founder and president, Otto Schnering. He has also made provision that certain employee benefits they have enjoyed, such as pensions, profit-sharing, and insurance plans, will still be available for their protection when they return. He also writes personal letters to them every month, and sends them boxes of the candy such as they used to help make, as well as samples of new food products developed by the company. They also get the news of the company’s activities and the activities of their fellow workers who are now in the service, through a monthly newsletter, and the firm’s 4,500 employees at home have formed ‘7 for 7’ clubs which divide employees into groups of seven and provide that each member of these groups write regularly to seven fellow employees now on the fighting front.” –Rolla Herald newspaper, Jan. 6, 1944

Otto liked to describe the Curtiss team as a family, with everyone looking after each other and doing their part. But, to make things clear, this was a capitalist family! And any sense of equal footing should not be construed as anything resembling socialism or union support. No Sir!

Accordingly, the December, 1946 issue of The International Teamster magazine went as far to call for a boycott on all Curtiss products, claiming that:

“The Curtiss Candy Company of Chicago has opened an attack on the wage scales of driver-salesmen in the food, candy and bakery industries,” and that “not a single man is employed by the company under union contract anywhere in the United States. …The action of the Curtiss Candy Company reveals a pattern of union opposition which is expected to become prevalent in the near future as many industries embark on a program of breaking unions and reducing wages. The most effective way to stop such tactics is not to patronize the products of the unfair firms. Curtiss has started the fight. Watch for Curtiss products and don’t patronize them.”

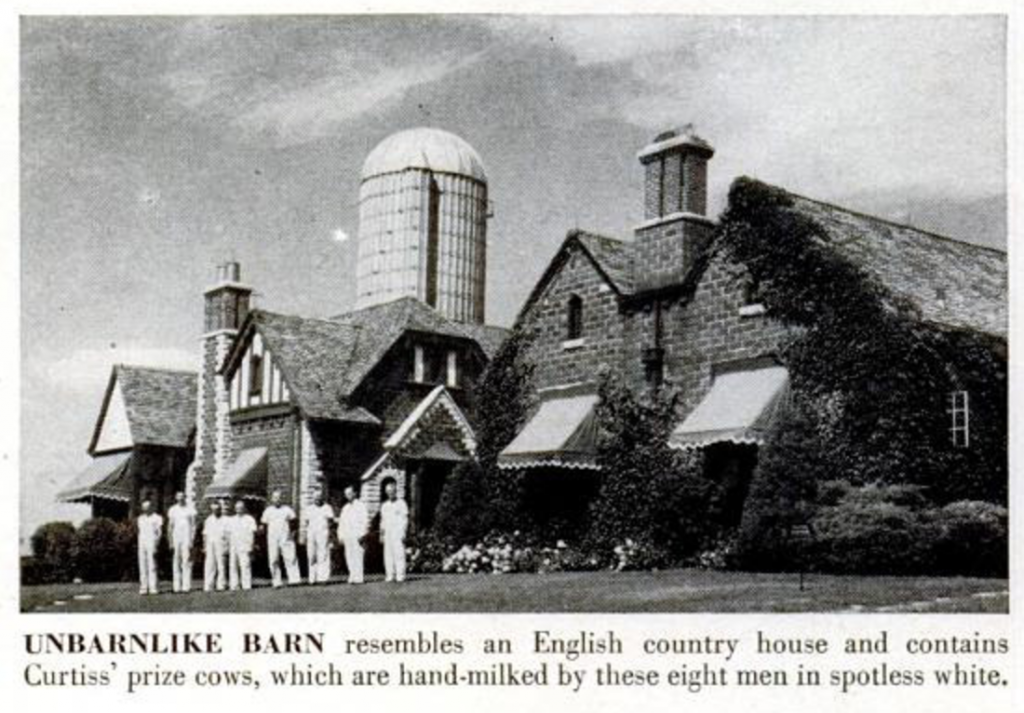

Schnering openly acknowledged his anti-union stance, preferring to emulate the “company town” dynamic with leadership paternally keeping the workers’ best interests in mind—rather than the workers representing themselves. During the 1940s, he took this concept to a whole new level, buying up several thousand acres of farmland in and around Cary, Illinois, and establishing housing for 300 men and women to help operate it. The Curtiss Farms became the main supplier of milk and other critical foodstuffs to the Curtiss Candy Co., and—because “if you’re gonna do something, you might as well do it right”—it also evolved into an award winning producer of elite show cattle, Shropshire sheep, and Yorkshire hogs.

“Self sufficiency is one of Otto Schnering’s watchwords,” Life magazine reported in a 1952 story on the farm. “The cattle earn their keep in the farm’s vast and profitable artificial insemination program. The trout are tended by grounds-keepers whose salaries are paid with revenue from the sale of trout. When Farmer Schnering surveys his domain and says, ‘Isn’t it pretty?’ Businessman Schnering happily replies, ‘Yes, and it pays for itself.’”

Schnering and his family moved into the former estate of John D. Hertz (the car rental guy) and became very hands-on in the daily operations of the Curtiss Farms. All decisions went through the family.

Early in the farm’s existence, in 1943, Schnering made headlines for agreeing to employ Japanese laborers in the middle of World War II. Perhaps feeling a kinship with the men as a German-American during the same difficult period, he told the Tribune: “These people are all master farmers. Many had their own farms on the west coast before the war. They want to work and they are good Americans.”

Schnering was consistent. If you were willing to do the work, and do it well, there was a place for you in his candyland army.

[Inside the Curtiss factory, from “Industry on Parade” news reel series, 1950s]

VI. The Factory Life

Back in the Curtiss Candy factories, the well oiled machine carried on into the final heyday of the Baby Boom years. Baby Ruth and Butterfingers, shipped in bulk out to grocery stores and candy dealers in shiny cardboard display boxes, were still produced almost entirely in Chicago.

One of the many faces in the crowd on the assembly line in 1951 was a Hungarian-born, post-war immigrant named Gabor Bethlenfalvay. In his 2011 memoir, In Search of an America: An Introvert on the Road, Bethlenfalvay—speaking of his younger self in the third person—recalls his first day on the Baby Ruth production team.

The foreman took him to his post at the business end of one stretch of the assembly line and gave him instructions, which he understood because they were accompanied by an appropriate set of hand-and-arm signals. Here is a fragment of one of the sentences that the boss barked at him, remembered to this day.

It went like this: “And then flush the mess down the sink.” The words and, then, and down he knew well enough. But flush from his readings in English literature at the AKO had two meanings: one was “to take reddish color”; the other was “to cause birds to fly up.” Mess was a group of people eating together like the officers’ mess. And sink was a very common verb, one of the mercifully few irregular ones in English grammar (sink, sank, sunk), meaning something like “move to a lower position.” As the sentence therefore presented a puzzle, he kind of shook his head, muttering to himself, “Sink? Sink?” “Yes, yes, the sink,” shouted the boss impatiently, pounding on the large, industrial-size drainage basin with his fist, “down the sink.”

To this day, I cannot imagine what the mess was that he should have flushed down that sink, for his duties were limited exclusively to handling cornstarch. But he said dutifully, “Ach so, okay, boss,” and then proceeded to start making his own money, sixty-eight cents an hour. A small step for Chicago but a giant step for him, for it was his first actual self-earned cash.

[Curtiss employees Helen Mizula and Rose Sciulara work the caramel coating station, c. 1940s]

[Curtiss employees Helen Mizula and Rose Sciulara work the caramel coating station, c. 1940s]

Working the cornstarch station, Bethlenfalvay recalled, was fairly simple:

“Take large, flat, shallow wooden trays filled with cornstarch and put them on a moving belt, making absolutely sure that there were no empty spaces left on the belt between trays. … The trick to this whole operation was that the belt, although it did not move at break-neck speed, never stopped. …In the exact time intervals that the belt moved the trays along their course, a large vat was lowered over the trays. It was filled with hot, molten caramel, and it squirted streams of this sticky goo into those grooves at precisely prescribed time intervals. Had the next tray not arrived at its correct space at the predetermined time, the goo would have been squirted onto the chains moving the belt, goobering up the gears and cogs that kept it moving and bringing the production to a sticky, sugary, and messy but otherwise blissful halt.”

This on-going challenge to avoid a caramel disaster kept Bethlenfalvay occupied, and though his mind did wander, it rarely wondered about the subject of its labors.

“It also occurs to me now [he writes], that curiosity never moved him to explore all the steps of the morphogenesis of the Baby Ruth candy bar (before and past the stage of his contribution to it) that he helped produce and dump on innocent children by the untold thousands during the two months of his stay there. Either he was too exhausted to go to the trouble or it was not interesting enough to find out.

I cannot swear to the process, but I know that I have never looked at a Baby Ruth bar since then, although I heard that they have been a consumer’s favorite since 1920. There were trays of it available without wrappings for anyone to eat to his heart’s content, but it was forbidden to take any of them out of the building. The mere smell of the stuff had become sickening to him by the third day.”

It’s no surprise that Otto Schnering encouraged his workers to snack away on their own creations. As chairman of the National Confectioners Association, he had played a leading role in promoting candy as a healthy habit, rather than a vice. Baby Ruth and Butterfinger ads, in particular, focused on the bars’ high percentage of dextrose—“the sugar your body uses directly for energy”—which also derived directly from Gabor Bethlenfalvay’s cornstarch trays.

It’s no surprise that Otto Schnering encouraged his workers to snack away on their own creations. As chairman of the National Confectioners Association, he had played a leading role in promoting candy as a healthy habit, rather than a vice. Baby Ruth and Butterfinger ads, in particular, focused on the bars’ high percentage of dextrose—“the sugar your body uses directly for energy”—which also derived directly from Gabor Bethlenfalvay’s cornstarch trays.

“You can run around the bases nearly 27 times on the food-energy contained in one bar of Baby Ruth.”

In an era when cigarettes were also being sold to kids, I suppose this isn’t the worst marketing offense one could be accused of. Still, one has to wonder—as a great supporter of children’s charities and groups like the Boy Scouts of America—if Otto Schnering truly believed in the health benefits of his own product.

VII. The Curtiss Legacy

Since Otto’s sons sold the Curtiss Candy Company to Famous Brands in 1964, the Baby Ruth candy bar has actually existed far longer in its post-Curtiss form than its original manifestation (both Baby Ruth and Butterfinger were acquired by Nestle, and more recently, the Ferrero Group). As a result, much of the American public has either forgotten or never been aware of the existence of this once central player in the candy bar revolution.

The wrecking ball erased the old Streeterville factories, and the old Curtiss Farm was sold by 1968. As the Curtiss name faded, the achievements of Otto Schnering followed suit, despite the best hopes of people like Henry J. Taylor:

“The years since this episode make much of it seem distant. And now my dear friend is dead. But the time that has passed has not changed the importance of such a performance. For there is never any change in honest principles. The good that men can do today by the example of integrity is the greatest good that can be done.”

[Otto and Dorothy Schnering, c. 1950]

[Otto and Dorothy Schnering, c. 1950]

[The Curtiss offices at Broadway and Diversey Pkwy]

[The Curtiss offices at Broadway and Diversey Pkwy]

[Curtiss factory at 337 E. Illinois St. in Streeterville, 1960s]

[Curtiss factory at 337 E. Illinois St. in Streeterville, 1960s]

Sources:

“Otto Y. Schnering” (Immigrant Entrepreneurship) by Samantha Chmelik, 2012

Chicago’s Sweet Candy History, by Leslie Goddard

Curtiss Farm – Dairy Agenda Today

“Baby Ruths, Butterfingers, and Stud Bulls” by Jeff Ruetsche

“The Farm That Baby Ruth Built,” Life Magazine, September 1, 1952

“Curtiss Candy Company Fights Teamster Unions,” International Teamster, Dec. 1946

In Search of an America: An Introvert on the Road, by Gabor Bethlenfalvay

“Brandt, Baby Ruth Ad Genius, Retiring” – Chicago Tribune, April 2, 1964

“Candy Makers Know Value of a Brand Name,” Chicago Tribune, Dec 9, 1951

Gas Age – Record, vol. 60, 1927

Printer’s Ink, vol. 100, 1917

“Home Sweet Home,” Rolla Herald, Jan 6, 1944

Congressional Record – House Committee: “Thirty Hour Week Bill,” 1933

When It’s Your Turn to Speak, by Orvin Larson

“The First Chapter-House Built in Chicago,” University of Chicago Magazine, vol. 10, 1917

Archived Reader Comments:

“My Dad worked for Curtiss management until it was sold to ‘amous Brands. He started with Curtiss in 1926. Have pictures of the fire at Streeterville factory with my Dad examining the structure. My Dad’s name was John Carl Otto.” —Gail (Otto) Heeres, 2020

“My mom wrapped Baby Ruths; she was born 1921  ” —Edward Vymola, 2019

” —Edward Vymola, 2019

“I remember the Butterfinger billboard on the Tri-State, near O’Hare, with its humorous weekly saying posted, facing the freeway.” —Steve Pellini, 2019

I just picked up a I believe 1947 to 1950 Chevrolet panel wagon has curtiss candy company logo on the doors

My Dad, Bruno Romano started back in the 40’s he was only 15 or 16. My Aunt got him a job there. He had 50 years or more when he retired. How excited us kids were at Xmas when a huge box came with all kinds of candy. My Dad got rings for his time there. He retired at 65 worked downtown build but they moved to Franklin Park. He never drove but guys picked him up who worked with him. Gee my sister, brother and I were lucky our Mom worked for Lenell Cookies. This article brings tears to my eyes. How my Dad always talked about work. He did miss them working on Illinois st in Chicago because he like going on the bus along the lake. Thank you for the wonderful memories.

I recently found a text book wrapped in a baby Ruth book cover from 1919. I can’t find anything like it and am trying to figure out how much it’s worth.

My brother has restored my uncle’s 1958 3800 Chevrolet Curtis Candy Company Truck after it had been in a barn for over 40 years..it had around 350,000 miles on it when parked.

The body is rusted and he would like to paint it the original color but does not have a picture of one…if anyone does…please send it to me.

Would anyone have pictures of the original Curtiss candy wagon? Not the pony wagons, we just purchased the big wagon from Larsen Clydesdales and we want to have it restored back to the original state. We think it was Robin egg blue when the black Clydesdales pulled it in Chicago in the 1940’s . Please help if you can this is a great piece of history!! Thank you !

Ms Wetterau, Did you ever come across any photos? I have an old photo but it was the pony hitch and it was a black and white photo. If you have any, could you email me copies? My dad drove the pony hitch for a time and he would often tell us about his days of hauling it around to the shows and rodeos and parades but I have only the one photo of it and I would love to see more. Hope you were able to find some too.

Thank you

Lorye

wells.ranch@hotmail.com

I have a plastic Curt Curtiss cowboy figure that looks like it might have fit over candy 5 in tall 3 in wide. Vintage, can anyone tell me what it could be, definitely vintage, looks like it might have fit over candy or lollipop.

any information helpful. thanks,

I would like to know what the JOLLY JACK Candy Bar was made of. The BIG three were always advertised together – Baby Ruth Butterfinger & Jolly Jack. But no one described or showed a cross section.

Thanks

Is there any way to find out if Curtiss was the candy company my mom worked for?

I have a Baby Ruth Candy wrapper with the “1c” mark in the center of the diamond where all the others have the 5c mark. There is also this quote printed on the wrapper “JACKIE COOPER star of the Metro-Goldwyn-lviayer’s picture “Treasure Island” discovers now treasure in CURTISS’ BABY RUTH BAR”. There is also a shield emblem with the words “ACCEPTED by the AMERICAN MEDICAL ASSN.. Also says A Curtiss Product and has the name BUDDIES in a circle placed between the Trade Mark Reg. and U. S. Patent Off. CURTISS CANDY CO> Otto Schnering, President, Chicago, Ill. U. S. A. Made by the Makers of Butterfinger

I have a post card dated 1929 thanking my grandfather for being a customer of Baby Ruth chewing gum. It looks like mail ed yesterday.

while not a regular candy consumer, my memories of Curtiss Candy was the regular visits of Martin Dabbiltt, our Curtiss inseminator, i was raised on and now operate a Dairy farm of my youth. My dad was an avid fan of Curtiss Bulls.This clip shows how good the dairy herd was, Curtiss was and still is a legend.

Tony my Dad got the watch also. It’s engraved on the back. So nice to have my Dad started Curtis at 15 retired at 65. Many years .

my grandfather worked at Curtis for over 50 years my grandmother gave me his gold pocket watch when he passed , he got from Otto Schnering and Otto even signed it !

can you please reproduce the original “Bubble Chum Gum” with it’s powder coating. It was 1 cent for 5 sticks but i know i am not alone when we would pay much much more for it today. it’s from the 1970’s. nobody sells it, cant find it so i am asking curtiss candy co.

Would anyone happen to have a picture of the plant in Franklin Park? would love one from the Curtiss days but even one from the 80’s/90’s would be great. My father worked as an accountant there for years, from the 70’s through the early 2000’s.

My father and his two brothers went to work for Curtis candy on briar Street in the late 40s. In the meantime my mother and her two sisters also got jobs around the same time. To make a long story short Three Brothers married three sisters! Three Middleton Brothers married three Kirk sisters. Anyway they always had great stories about working there going bowling seeing a movie downtown etc.

My grandfather, Burke L Jones, Arkansas, worked for Curtis Candy Co and I ran across several old pictures of him, others and some of either meetings or shows. I’d love to share!!

Laura Simmons Martin, Memphis

Thanks, Laura. Feel free to email us at contact@madeinchicagomuseum.com if you’d like to share those pictures!

As to the comment: “I remember the Butterfinger billboard on the Tri-State, near O’Hare, with its humorous weekly saying posted, facing the freeway.” —Steve Pellini, 2019

In the early/mid 1960’s, the Curtis Candy Company factory was built at 3401 Mt. Prospect Rd. in Franklin Park. We used to ride our bikes in the dirt by the construction sight (before anybody heard of the term BMX). The sign for the factory indeed was close to I-294 where it jogs around the old Milwaukee Road Bensenville Yard (that stretched all the way into Franklin Park). When it was completed and operational, the smell was wonderful.

Hi Lisa was just checking to see if you still have the jacket for sale and if so can you provide some pics. Thx

David

I have a vintage Baby Ruth vendor jacket in very good condition that I am ready to sell. It was just appraised at $600-$800. If you know of someone interested, please let me know.

Thank you!

I have a picture of the Curtiss Wagon with ponies pulling it. It looks to be at some outdoor event. My grandfather worked for Dicksfield farm in Gurnee, IL. The farm raised and showed horses. This picture was in his album. If anyone wants to see

it, let me know. tcslane154@gmail.com

Cindy

Do you have a old photo of “Royal Flush” candy bar ?

I don’t see a mention of the Curtiss pony and wagon team which performed at horse shows, rodeos, store openings and promotional events. My father staged a photo event of the horses checking in to the famous Rice Hotel in Houston. Photos were of the ponies standing at the front desk, getting on an elevator and standing in a room. It made the city newspapers. Ponies were named after seven dwarfs iirc. My father started working for Curtiss in the 1930s as a salesman in Milwaukee where he had moved looking for work. He worked the bars and stores. Eventually he returned to Texas becoming a district manager over several states. Curtiss had an office and warehouse in Houston. After that was closed, he worked out of Dallas where Curtiss had a small candy factory. He remained with Curtiss until Curtiss was sold and the new owners eliminated some upper management staff. I still have lots of his photos from the time. I also remember a promotion where a large Baby Ruth candy Bar, about 2 or 3 feet long and maybe a foot in diameter toured grocery stores where customers would submit their guesses as to how many peanuts were inside. I don’t remember the prize.

Hello Mr Crook, If you have any of those pictures of the pony hitch I would love to have a copy of them. My Dad was one of the drivers of that hitch for a time being and he always talked about it but we had only one grainy picture until recently I saw another one where the hitch was standing next to the Anheuser Busch Clydesdale’s in the Freeman Coliseum in San Antonio Texas and it sparked my interest in finding more info. Reading your comment was so special, I can’t imagine all of that! Hope you see this!

wells.ranch@hotmail.com

I have recently come across a cotton sack with red writing, which states, “Curtiss Baby Ruth 5 cents.” I would like to know what year these were manufactured.

I was raised in a Baptist Children’s home in Thomasville, NC. In the early 60’s one of the kids sent a letter to the Curtiss Candy Co. telling them how much he liked Baby Ruth candy bars. He was obviously trying to score a free candy bar. His plan worked, Curtiss sent us a 100 lb Baby Ruth candy bar. They put this huge candy.bar into cold storage and us Boy Scouts chopped this candy bar into small pieces and put it into.gallon paper buckets and we distributed the buckets to all the cottages. 350 – 400 kids ate off this one candy bar. I do have a photo of this candy bar.