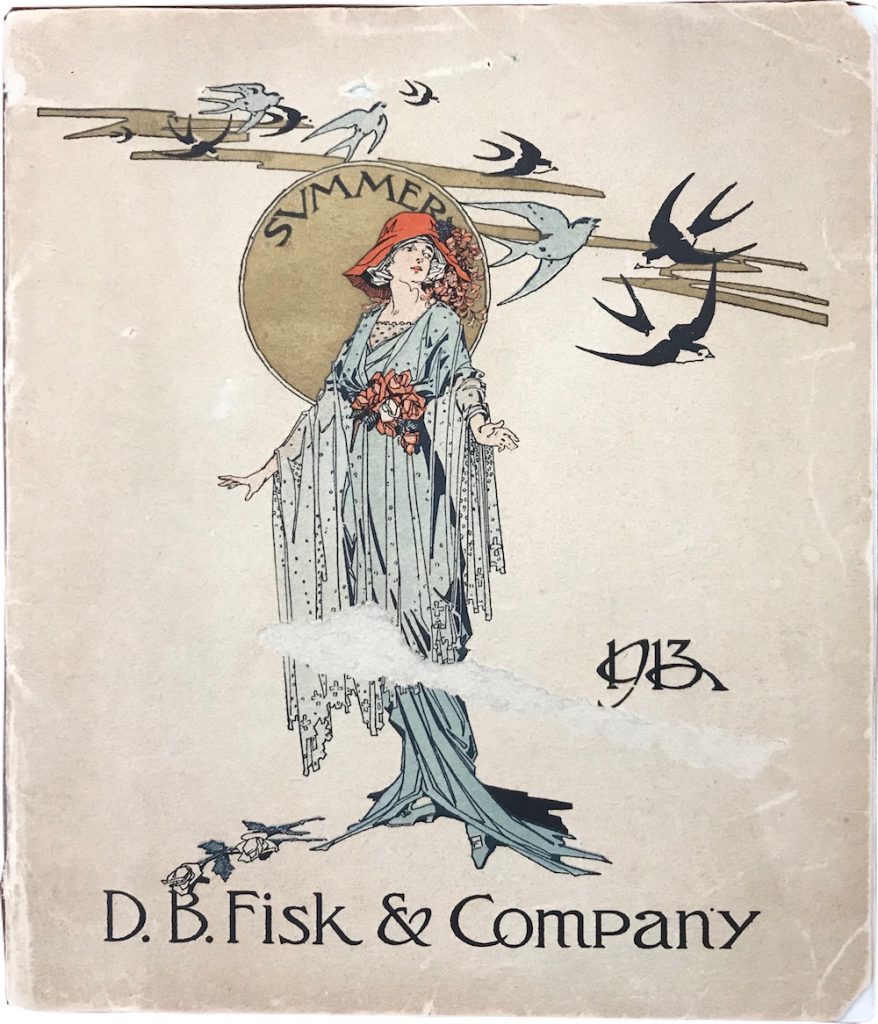

Museum Artifact: Woman’s Hat, aka Fiskhat, c. 1920s

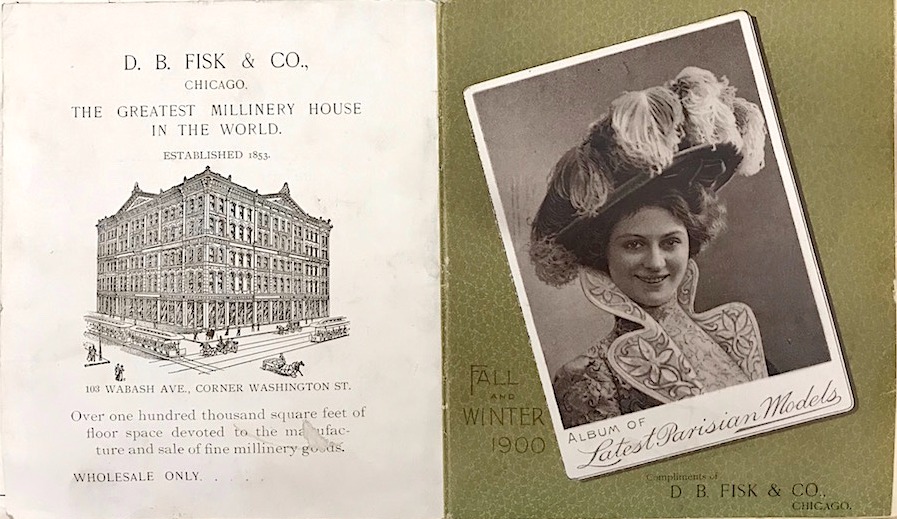

Made By: D.B. Fisk & Co., 225 N. Wabash Ave., Chicago, IL [Downtown / The Loop]

The slow death of the millinery trade in America is usually attributed to a simple change in fashion trends—something about the 1960s cultural revolution vs. the puritan formalism of the hat. In truth, though, women’s headwear didn’t just fall out of favor in the late 20th century; it was directly vanquished by the rise of the modern haircare industry. It’s no coincidence that the first commercial hair sprays and rinse-out conditioners came along just before the chapeau bowed out.

And so, for a trade that had once hunted the Carolina Parakeet into extinction for its colorful plumage, the chickens came home to roost. Hats haven’t ceased to exist, of course, but they’ve suffered perhaps a fate even worse—quirky novelty status.

And so, for a trade that had once hunted the Carolina Parakeet into extinction for its colorful plumage, the chickens came home to roost. Hats haven’t ceased to exist, of course, but they’ve suffered perhaps a fate even worse—quirky novelty status.

With this in mind, a long forgotten company like Chicago’s D. B. Fisk & Co. really represents the last great armada on the losing side of a war—a war for the pocketbooks of American women. That doesn’t sound like a particularly noble cause, I suppose, but Fisk—being a sophisticated enterprise of the Victorian age—made a genuine artform out of their efforts. They also employed several generations of skilled workers and salespeople—most of them women.

Fashion for the West

“Conspicuous among the merchants who have given character and fame to Chicago,” Harper’s Bazar reported in 1873, “is the well-known firm of D. B. Fisk & Co., importers and manufacturers of, and wholesale dealers in, millinery and straw goods, ladies’ furnishing and fancy goods.

“. . . Their stock is the most extensive and complete to be found in the country, and as they always keep the best class of goods, both as respects quality and style, their house, for a long time, has been the headquarters of Fashion for the West.”

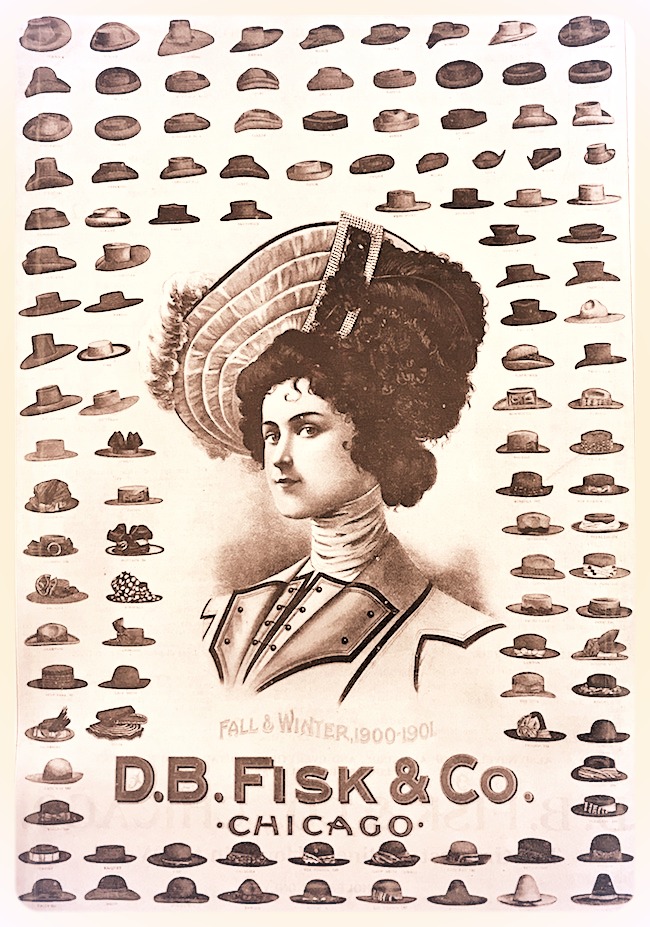

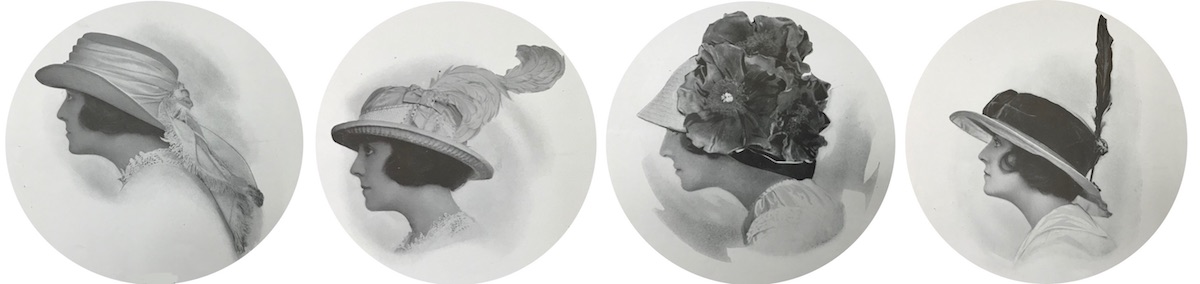

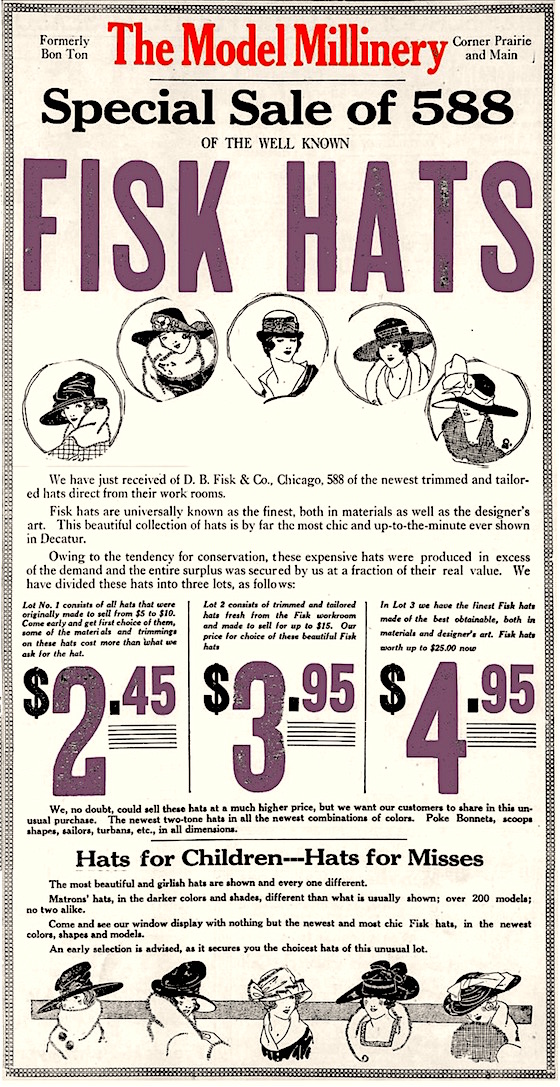

[Styles from the 1900 Fisk catalog]

[Styles from the 1900 Fisk catalog]

From the perspective of someone in 1873, anything existing in Chicago “for a long time” carried particular weight. Not only was D. B. Fisk one of the pioneering mercantile institutions of the city (the company was founded in 1853, just 16 years after Chicago was incorporated), but it was also one of the quickest to rebound from the catastrophic Great Fire of 1871.

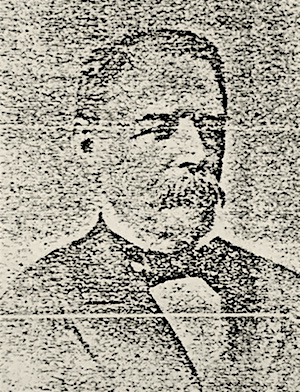

Both the firm’s initial success and its post-fire perseverance reflect kindly on its founder and namesake, David Brainerd Fisk.

Born in Upton, Massachusetts, in 1817, Fisk got his early retail training at his father’s general store, and eventually ran the shop himself while also serving as the town postmaster. It wasn’t until he was 36 years old—and married with two kids—that David made the impressively bold decision to pick up stakes and head west.

Born in Upton, Massachusetts, in 1817, Fisk got his early retail training at his father’s general store, and eventually ran the shop himself while also serving as the town postmaster. It wasn’t until he was 36 years old—and married with two kids—that David made the impressively bold decision to pick up stakes and head west.

The first D. B. Fisk & Co. shop, located at Wells Street between South Water and Lake Street, opened in 1853 as the only millinery house in Chicago and the first of its kind west of the Alleghenies. Depending on how you look at it, starting the business was either a risky gambit or a slam dunk no-brainer. Sure, there was no precedent for such an operation in these parts, but at the same time, Chicago’s population was booming, and fortune seekers were bringing their families with them to the shores of Lake Michigan. Families meant women, and women—with few exceptions—wore fancy hats. If anything, Fisk wasn’t so much gutsy as he was opportunistic.

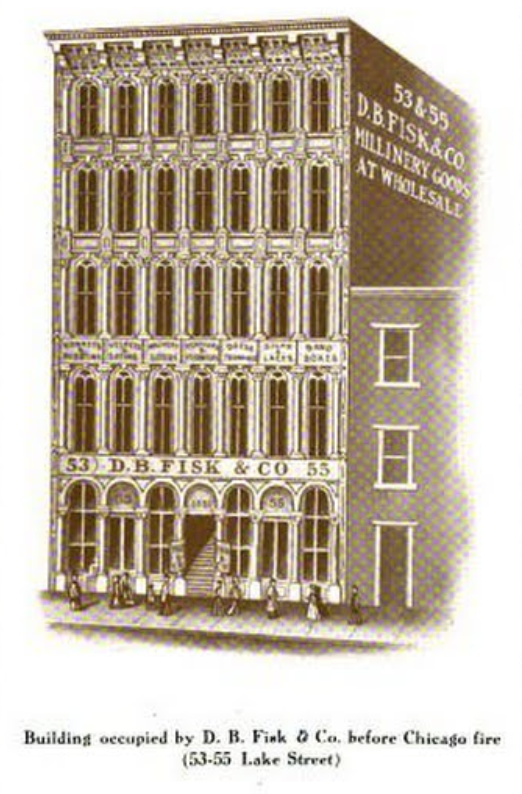

By 1859, David Fisk—in partnership with his son Daniel M. Fisk and a fellow hatman named John E. L. Frasher—incorporated Fisk & Co. at its new headquarters: 53-55 Lake Street. This is where the company really grew into one of the city’s major fashion houses.

“Standing prominently at the head of its department of trade, and indisputably the largest house of its class on this continent, is the firm of D. B. Fisk & Co., wholesale millinery,” Alfred T. Andreas wrote in his History of Chicago: From 1857 Until the Fire of 1871. “Its history from its founding here to the present time forms not only a forcible illustration of that growth and development which has characterized the trade and commerce of Chicago from then until now, but it shows how much can be accomplished by intelligent, persistent, and well directed effort.”

“Standing prominently at the head of its department of trade, and indisputably the largest house of its class on this continent, is the firm of D. B. Fisk & Co., wholesale millinery,” Alfred T. Andreas wrote in his History of Chicago: From 1857 Until the Fire of 1871. “Its history from its founding here to the present time forms not only a forcible illustration of that growth and development which has characterized the trade and commerce of Chicago from then until now, but it shows how much can be accomplished by intelligent, persistent, and well directed effort.”

Fisk hadn’t remained Chicago’s lone milliner for long. Seeing the company’s success as both a manufacturer and storefront, a gaggle of local competitors sprung up fairly quickly—Gage Brothers, Webster Brothers, Keith Brothers (I guess male siblings really had a leg up in the hat game back then). But none could match the size or success of the original.

Then came disaster.

“It Was Literally Raining Fire”

The might of D. B. Fisk & Co.’s downtown headquarters—as with all its neighbors—offered no resistance to the undiscriminating fury of the conflagration that consumed the city on the night of October 8th, 1871. Eighteen years of work was reduced to kindling in minutes, and David Fisk, now aged 54, was—like so many others—standing at a crossroads.

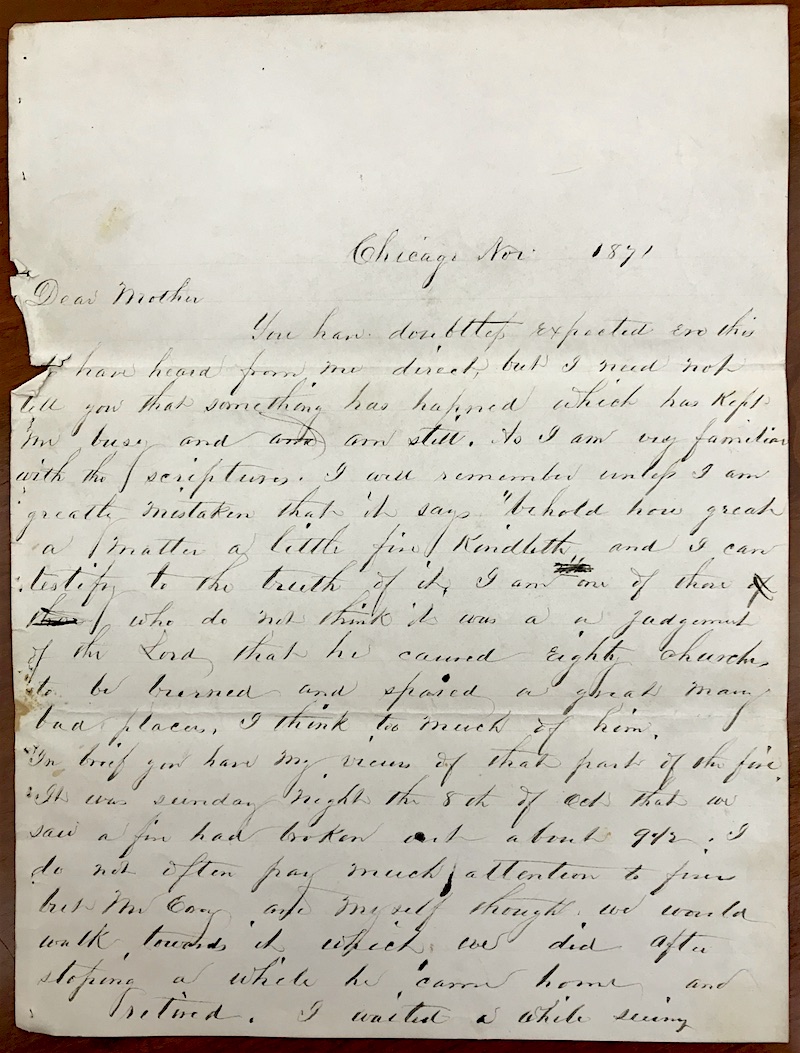

“You have doubtless expected ere this to have heard from me direct,” Fisk wrote his mother a month after the fire, “but I need not tell you that something happened which has kept me busy, and am still. As I am very familiar with the scriptures, I well remember, unless I am greatly mistaken, that it says ‘Behold how great a matter a little fire kindleth,’ and I can testify to the truth of it.”

“You have doubtless expected ere this to have heard from me direct,” Fisk wrote his mother a month after the fire, “but I need not tell you that something happened which has kept me busy, and am still. As I am very familiar with the scriptures, I well remember, unless I am greatly mistaken, that it says ‘Behold how great a matter a little fire kindleth,’ and I can testify to the truth of it.”

Even after insurance, Fisk guessed that he lost $100,000 in damages (many multi millions in modern money), but the greater damage may have been done to his psyche.

“It was literally raining fire,” Fisk wrote, recounting the mad dash he and several clerks made to save valuable goods from the store via horse-drawn wagons. “Streets were as light as day, buildings falling with terrific crash, flames spreading from street to street; men, women and children hurrying to and fro, horses running away, wagons smashed with loads of goods amounting to fabulous sums and burned in the streets. Thieves so anxious for plunder that many forgot their safety and were happily burned in the flames.

“Once when I was driving a load of velvets, some of the boxes fell off. Instantly a woman came up and grabbed two boxes of velvet and started to run with them. I put my hand to my pocket as if to draw a revolver (though I had none) and threatened her with instant death if she did not at once drop them, which she did and saved me the velvets if she didn’t her life. Henry said it made him think of war times.

“On we drove with loads of goods, shouting to clear the way and never minding who was disabled or was run over. Everyone had to take his own chances. It was life or death to all, poverty to all who were in the streets. No such scene was ever witnessed since the world was made.”

[“Memories of the Chicago Fire in 1871,” painting by Julia Lemos, 1912]

[“Memories of the Chicago Fire in 1871,” painting by Julia Lemos, 1912]

Earlier that evening, when Fisk had seen the fire from a distance, he’d calculated in his head a charitable contribution he’d happily make the next day to help those affected. By midnight, his calculations had shifted to his own survival, and trying to maintain some remnant of the life and business he’d built.

“At every load I took to the house, while it was being taken off, I took a little whiskey to nerve me up so that I could run all risks without fear. I stuck to driving away with the goods until the last moment, when our beautiful store was on fire, and I was not allowed to go near it. For five minutes or so, as I could see the flames rushing out of the large windows and licking up all, I felt terribly of course. Our books were taken out of the safe and saved by one of our clerks and that was one thing which saved me from being a recipient of the best charity the world ever bestowed. After our store was burned, which was about 3 o’clock in the morning, and as daylight appeared, I was negotiating for another place of business with others who had been spared, but before 10 o’clock their premises had been burned, and they too were as bad off as we.”

“ . . . The scenes which were witnessed will never be forgotten. Our home was saved and we are well off in comparison to some who were very rich before the fire. . . . [The business] is now located in a small place but we are doing well and in time shall be back in a larger and better store, and in time Chicago will be better off than ever. When I come on this winter I hope to see you and find you comfortable, and I will tell you what I can’t write.

“With love to all, and also a pleasant Thanksgiving, which I hope to have.

I am Your Son,

D. B.”

[The ruins of the D. B. Fisk building on Lake Street, with a sign directing passersby to Fisk’s temporary new location on W. Washington St.]

[The ruins of the D. B. Fisk building on Lake Street, with a sign directing passersby to Fisk’s temporary new location on W. Washington St.]

The Phoenix

As mentioned in his letter, Fisk wasted little time setting up a temporary new headquarters for D. B. Fisk & Co., located inside a surviving building at the corner of W. Washington and Clinton Street. Within a week after the fire, their doors were open, and orders were being taken. And less than two years later, a massive new five-story complex—far bigger than the one lost in the fire—opened at Wabash Avenue and Washington St.

Saving the company books had been one lifesaver for Fisk & Co., and a fairly good insurance package was another. But for many people—clients, customers, and employees alike—the leadership and reputation of David Fisk himself were paramount in the firm’s re-establishment.

Saving the company books had been one lifesaver for Fisk & Co., and a fairly good insurance package was another. But for many people—clients, customers, and employees alike—the leadership and reputation of David Fisk himself were paramount in the firm’s re-establishment.

“The personality of D. B. Fisk had much to do with the success of the business,” according to a 1915 edition of The American Angler. “His sagacity as a merchandise man, his ability as a buyer, his taste and judgment were all of high order. He was exceedingly pleasing and throughout his career made a special effort to meet and personally know every customer of the firm.”

An obituary in the Inter-Ocean newspaper following Fisk’s death in 1891 further paints a picture of a millionaire who didn’t act or live like one.

“Mr. Fisk was not a society man, although he was a member of the Chicago, Calumet, and Washington Park Clubs. He was fond of his family and was usually to be found at home in the evening. . . . He was regarded as one of the most honest and straightforward men Chicago has known. ‘His word was as good as his bond’ was truly said of him.”

“Mr. Fisk was not a society man, although he was a member of the Chicago, Calumet, and Washington Park Clubs. He was fond of his family and was usually to be found at home in the evening. . . . He was regarded as one of the most honest and straightforward men Chicago has known. ‘His word was as good as his bond’ was truly said of him.”

A family history of the Fisks notes that D. B. had “never known a sick day until about three weeks before his death [from bronchitis].” The man was dedicated to his work, and he earned that dedication back from the hat makers and hat wearers of his era.

“What the name of Marshall Field is to the dry-goods trade, the name of D. B. Fisk is to the millinery trade,” Josiah Seymour Currey wrote in his Chicago: Its History and Its Builders. “There remains as a monument to his activity and enterprise the large wholesale establishment which he founded and conducted.”

Wabash & Washington

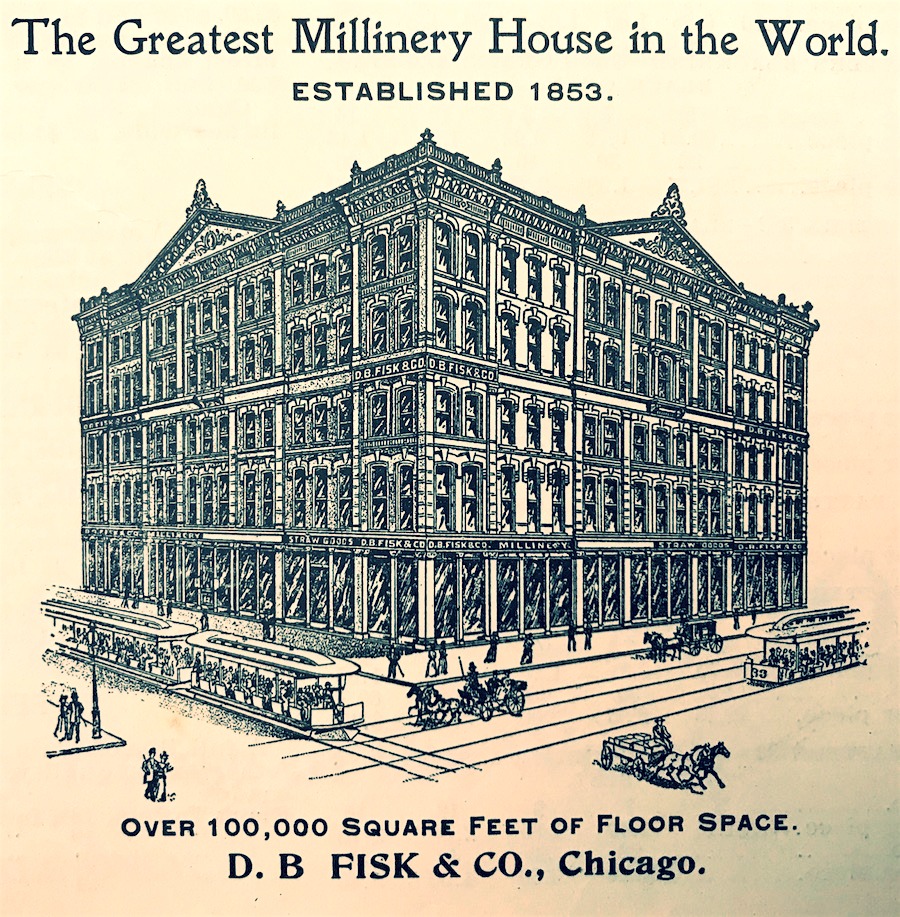

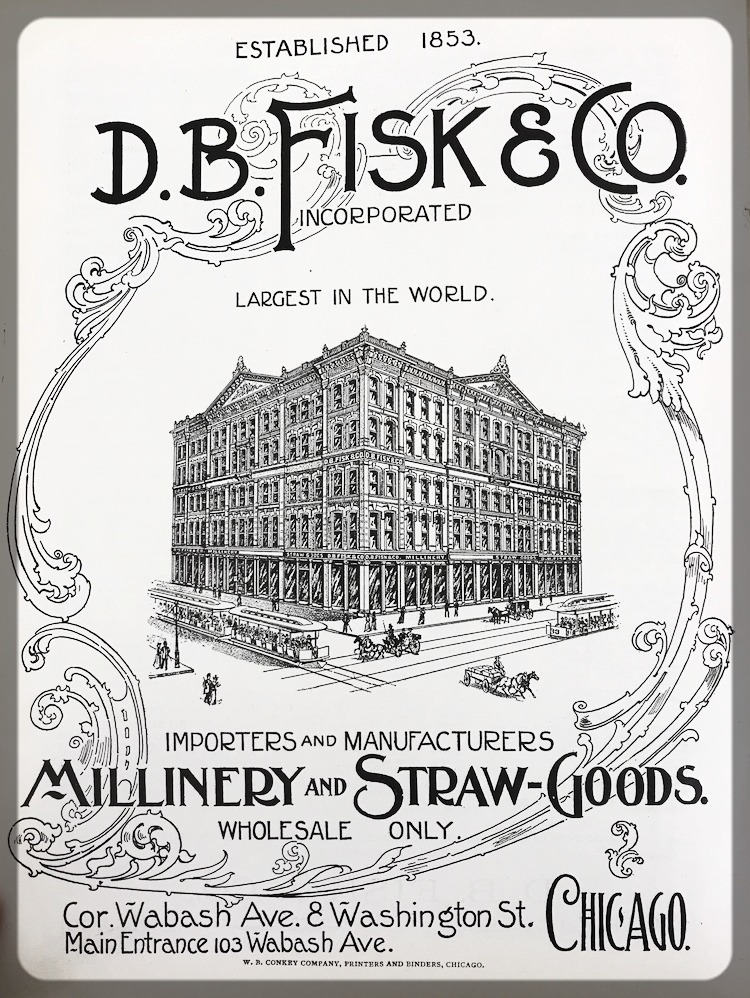

D. B. Fisk & Co. existed for nearly 100 years in total, and nearly half of that time was spent at its 130,000 square foot home at Wabash and Washington Street—a custom-made fortress equipped for manufacturing, warehousing, design, and the very best in personalized, upscale sales.

The store was in a high traffic, central location—later purchased by Marshall Field & Co. and added to its famous annex.

“The premises consist of six floors,” Harper’s Bazar reported shortly after the store opened in 1873, “finished from basement to roof in the most substantial and elegant manner, heated by steam and furnished with elevators for freight and passengers, and every modern convenience, so that the whole business can be transacted more easily than if the space was all on one floor. The Offices, Ladies’ Parlor and Toilet Rooms, on the main floor, are of black walnut and ebony, with rich carvings and plate-glass; and the grand massive stairway to the second floor challenges admiration.

“The premises consist of six floors,” Harper’s Bazar reported shortly after the store opened in 1873, “finished from basement to roof in the most substantial and elegant manner, heated by steam and furnished with elevators for freight and passengers, and every modern convenience, so that the whole business can be transacted more easily than if the space was all on one floor. The Offices, Ladies’ Parlor and Toilet Rooms, on the main floor, are of black walnut and ebony, with rich carvings and plate-glass; and the grand massive stairway to the second floor challenges admiration.

“Superbly lighted throughout, the panes of French plate glass on the main floor being seven feet wide and 15 feet high, so that not only is there ample room for the display of their immense stock, but every floor is so fully lighted that all their goods are shown to the best advantage for purchasers.

“No expense or labor has been spared to combine Use with Beauty, and make the whole a perfect temple of art. Every accommodation and comfort are afforded to customers which an intelligent appreciation of their wants, prompted by a liberal hand, could provide.”

Twenty years later, King’s Handbook of the United States, a tourist’s guide, singled out Fisk’s store as a must-see Chicago landmark: “Their emporium covers six large and well lighted floors, each nearly half an acre in area with artistic displays of costly ribbons and feathers, beautiful flowers, fine straw goods, and other attractive articles from their own factory, as well as from the most famous manufactories in Europe and elsewhere.”

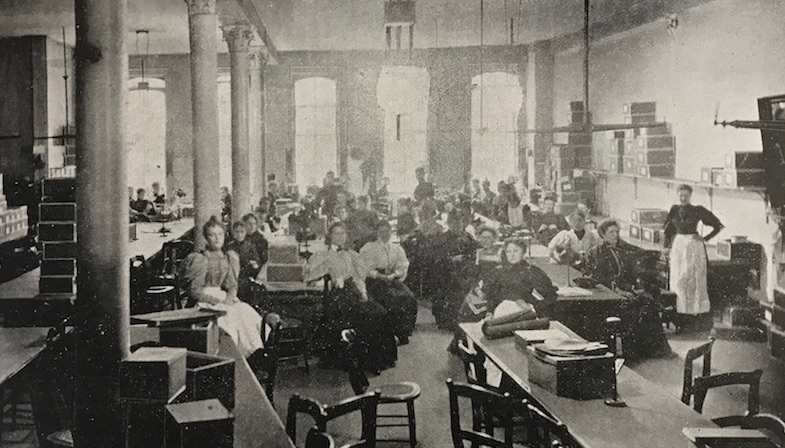

[The trimming department, located on the top floor of the Fisk building, c. 1896]

[The trimming department, located on the top floor of the Fisk building, c. 1896]

While departments occasionally were re-organized over the years, the building generally always featured sales space on the main, second, and third floors, with endless displays of hats and all related accoutrement: ribbons, velvets, silks, veilings, laces, flowers, feathers, etc. The basement was the shipping center and housed the steam engines and boilers; the fourth floor was for receiving, distributing, and duplicate storage; and the top floor housed the manufacturing departments.

In 1898, the Factory Inspector of Illinois reported that D. B. Fisk & Co. had an active employee count of 465. Breaking down that total, there were:

⇒ 310 female workers over the age of 16

⇒ 147 male workers over the age of 16

⇒ 5 girls (under 16)

⇒ 3 boys (under 16)

This was no novelty “hat shop.” This was a major department store, factory, and distribution center wrapped in one, with a deep crew of sales agents and expert millinery masters designing and constructing the latest trends.

“The Monitor of Fashion”

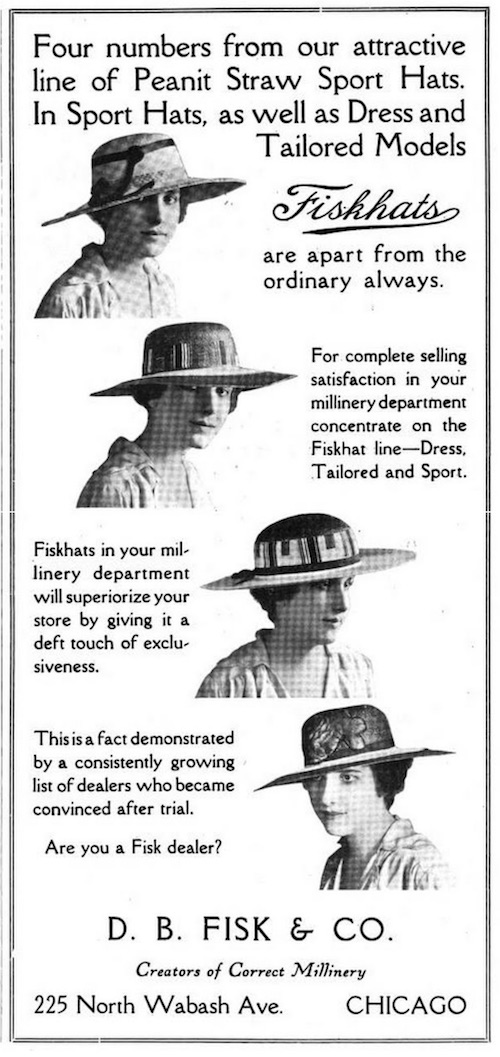

In the hat game, keeping up with that aforementioned trendiness was no easy task. Fisk & Co. didn’t just need to convince the general public they were cutting edge. As a wholesaler, the company’s real bread-and-butter clientele was other merchants—smalltime hat salesman from all over the country who needed to stock their own shops. Many of these dealers, through their own biases, remained stubbornly unwilling to look to Chicago as a monitor of fashion.

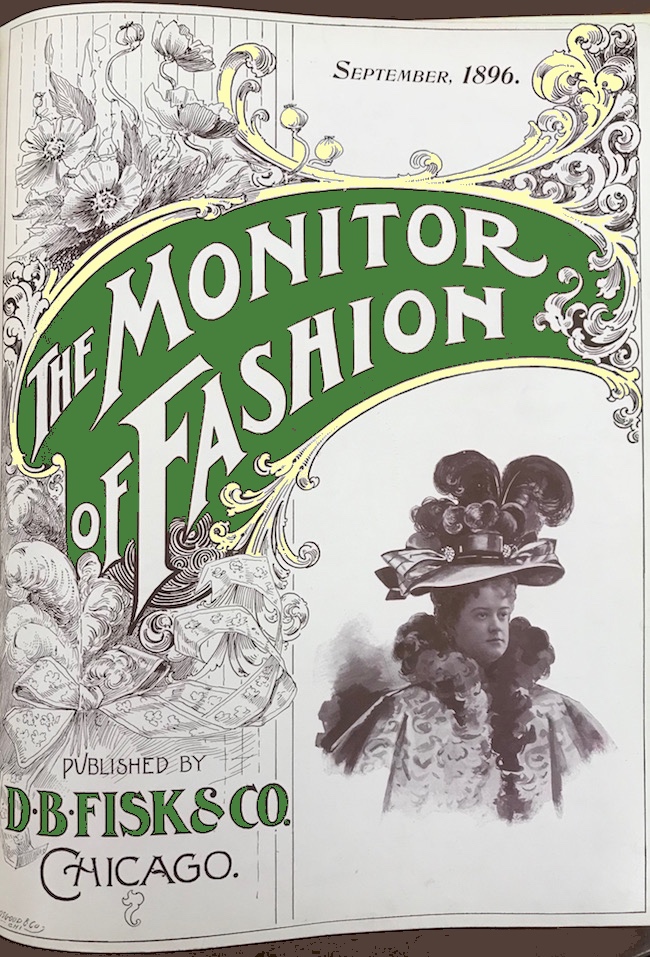

In response, D. B. Fisk & Co. began promoting its wares through its own monthly magazine, titled the Monitor of Fashion (For the Millinery Trade). In the September 1896 issue of that publication, they took a pretty direct approach to the haters.

In response, D. B. Fisk & Co. began promoting its wares through its own monthly magazine, titled the Monitor of Fashion (For the Millinery Trade). In the September 1896 issue of that publication, they took a pretty direct approach to the haters.

“All dealers want the best goods, the newest ideas and most fertile suggestions, the largest and best assortment from which to make selections, and all at the lowest possible prices. In order to get these things you must go where they are. If you don’t know where that is by this time, drop in at 103 Wabash Avenue any day, and we’ll show you.”

Impressive gusto!

In that same issue, Fisk’s editorial board made a point of painting themselves equally as originators and capable followers of any and all things fashionable.

“Two things are necessary to success in the millinery business. No amount of capital, no host of friends will make up for the lack of these two. The first is: A quick, intuitive comprehension of the best way to use and adapt an idea. The second is: Ideas for use and adaptation. All good milliners have the first. And D. B. Fisk & Co. make a business of furnishing the second.

“. . . While not neglecting the staple and regular lines, we aim to show as many new ideas as seem specially desirable for easy adaptation. . . . We are closely in touch, however, with the great fashion centers, and are constantly in receipt of fresh advices from Paris and London regarding new and attractive things.”

Most of the time, these “new and attractive things” look objectively over-the-top or downright absurd by modern standards. A woman’s hat couldn’t be a mere accessory back in the day. It had to be a statement—be it of social status, personality, vitality, you name it. Minimalism was a non-starter. In its place, an explosion of bobs, fluffs, ruffles and ribbons. And sometimes, dead birds.

“The abundance of trimming, and harmonious coloring, with much latitude in regard to hat shapes, are the leading characteristics of the new season’s millinery,” the Monitor of Fashion reported in October of 1896. “When particularizing as to trimmings, feathers claim first place. Plumage of various birds, natural and manufactured, with the graceful paradise as the novelty of the season, is a leading feature. Birds of all kinds and all countries have sacrificed their plumage. . . . Unnatural creations with wings of one kind and head of another seek for favor, along with birds that look as if they had perched, saucily for the moment, upon a lady’s bonnet.”

Of course, the Carolina Parakeet—America’s lone parrot species prior to its expiration in 1908—might quibble with the idea that it “sacrificed” its plumage for Lady Matilda’s dinner party hat. But you get the point. Fashion, for all its reliance on change, never ceases to do what fashion always does.

How a Hat Was Made

The Monitor of Fashion magazine was produced during arguably the golden age of D. B. Fisk & Co., as the firm rode the wave from the Columbian Exposition of 1893 into the first decade of the 20th century. These were also the years immediately after David Fisk’s death, and might have played out quite differently if not for the return of Fisk’s longtime business partner John Frasher, who, at age 61, agreed to come out of retirement to serve as the company president (David’s son Daniel had relocated to New York).

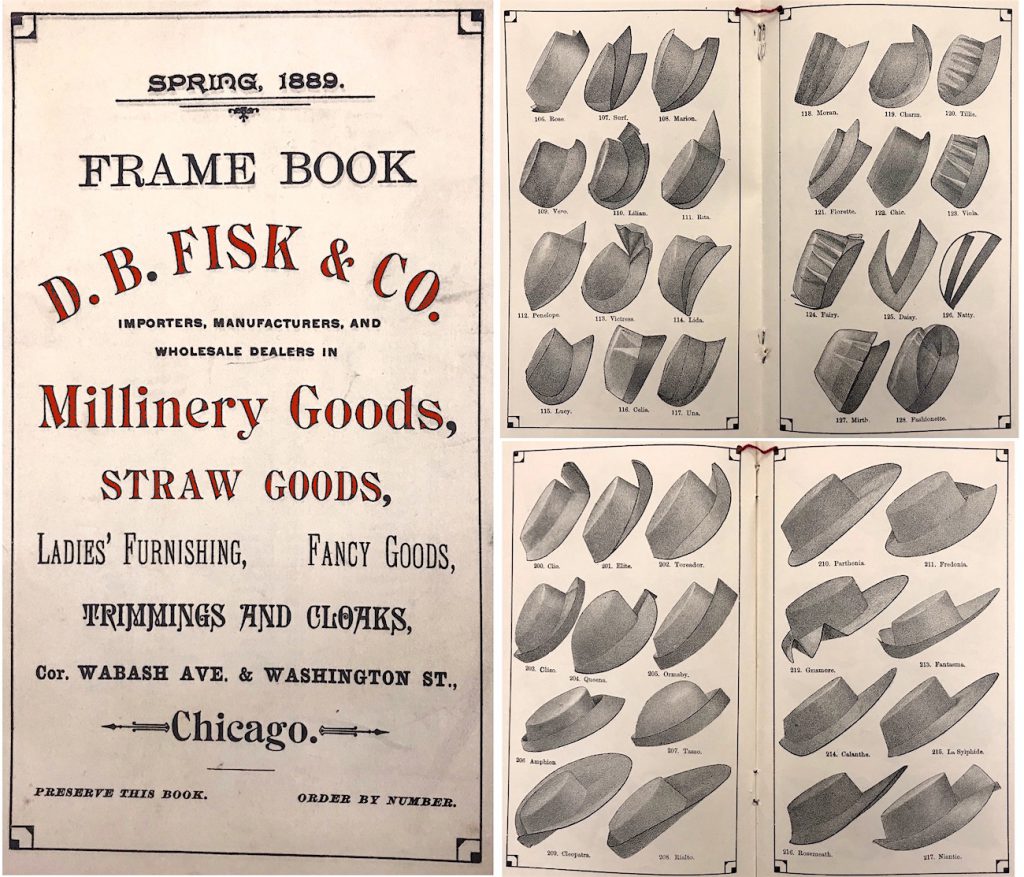

Being of the “old school,” Frasher ran the business much as Fisk had. Regardless of fashion trends, the manufacturing process for each hat followed a strict, traditional methodology, going through numerous pairs of hands and several clunky Victorian machines en route to official hatitude. It’s worth noting that a lot of the hats Fisk sold were just the products of a base mold, with no further adornment. Milliners would buy these in bulk and add their own feathers and bows. The actual construction of the hat itself, then, was as important to Fisk’s business as its attention to trends.

Being of the “old school,” Frasher ran the business much as Fisk had. Regardless of fashion trends, the manufacturing process for each hat followed a strict, traditional methodology, going through numerous pairs of hands and several clunky Victorian machines en route to official hatitude. It’s worth noting that a lot of the hats Fisk sold were just the products of a base mold, with no further adornment. Milliners would buy these in bulk and add their own feathers and bows. The actual construction of the hat itself, then, was as important to Fisk’s business as its attention to trends.

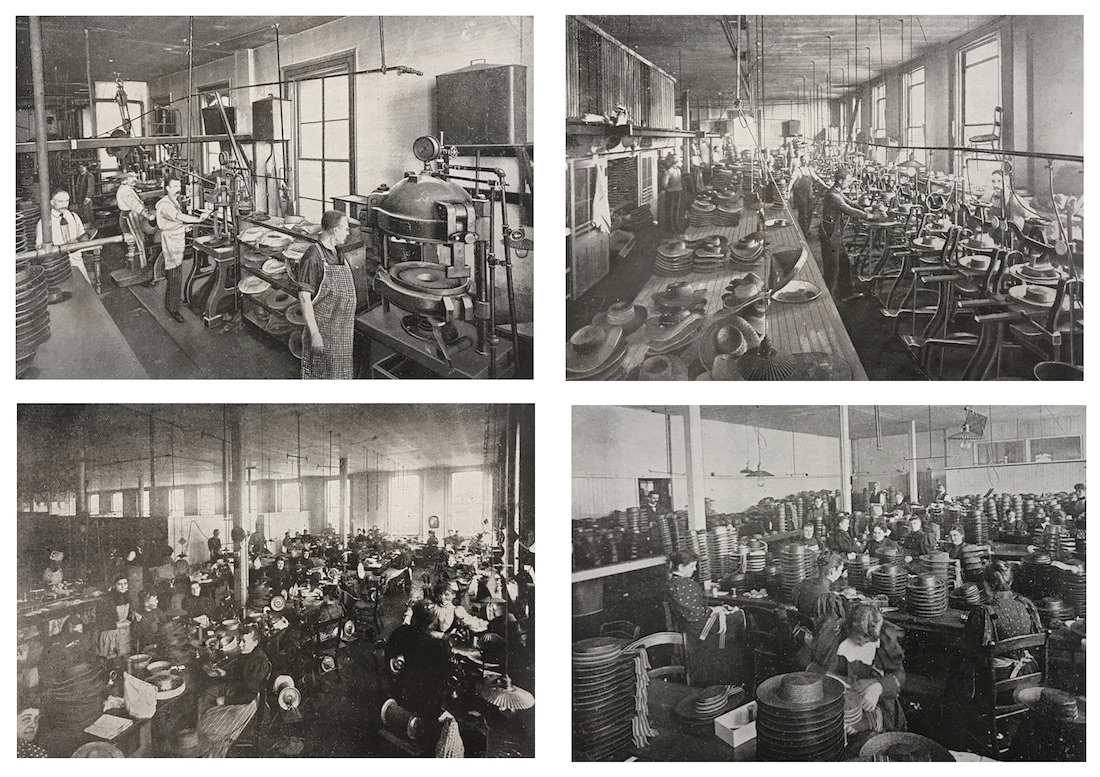

“It will certainly be of some interest to the general public,” the Monitor of Fashion reported in 1898, “and perhaps more especially to the millinery circles, to know that on the top floor of D. B. Fisk & Co.’s great millinery establishment there is a hat factory complete in all its appointments; and in which are employed a large and competent staff of operators, who each season turn out hundreds of every possible and conceivable style of hats for the house and its customers. The entire top floor of the building is occupied by this factory, as is also the roof, which serves in the capacity of dyeing and bleaching department.”

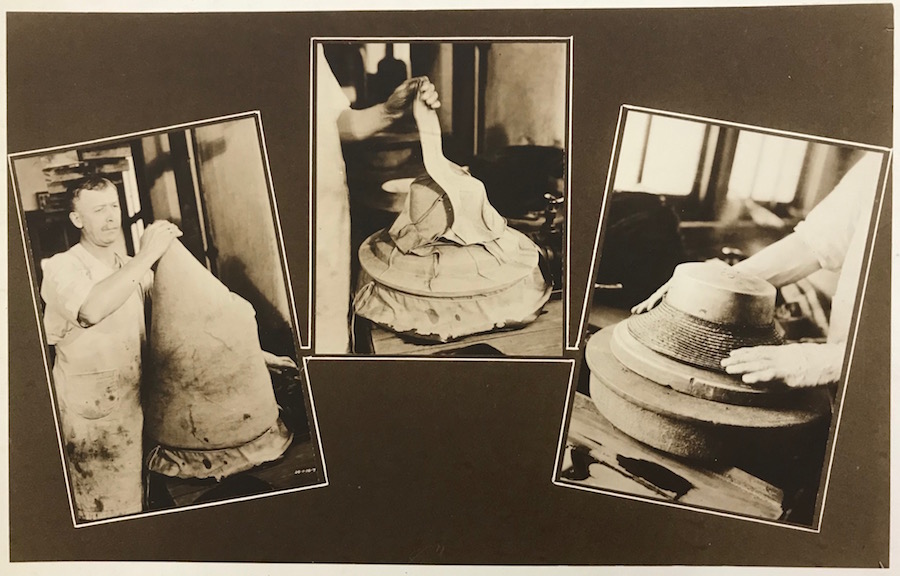

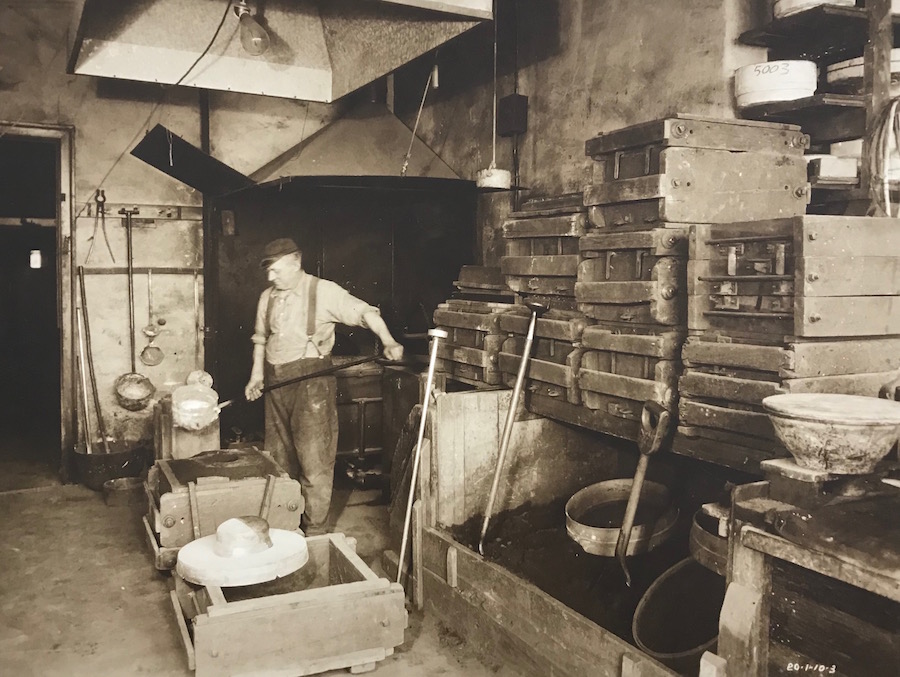

[Creation of a hat mold at D. B. Fisk factory]

[Creation of a hat mold at D. B. Fisk factory]

The “evolution of a hat,” as the company called it, generally involved the following steps:

Block Making: Before any of the actual materials of the hat get involved, specialists in the factory were tasked with creating original molds by carving shapes out of plaster, then varnishing them. From these molds, metal casts were made and sent along to the sizing and pressing department.

Preparation of Straw Braids: Meanwhile, the raw materials of the hat—largely imported from Europe—were unbunched and sorted out of giant bales in a variety of forms (plain braided straw, chips, cotton-lace, etc.). Workers then used dyeing vats to add the desired color, and moved the straw up on the roof to dry.

Sewing Straw: Once dyed and dried, the braids were taken to the sewing department in the front portion of the factory. Here, each operator (most of them women) had her own electric sewing machine, by which she would sew the strips of straw braids together over a plaster mold. Even with the aid of increasingly advanced sewing machines, this was an arduous process requiring a firm but delicate hand.

Sizing and Pressing: For sizing, the hat was soaked in glue, to give it stiffness, then drained and dried again. This made the thing downright brittle, so a steaming process was next used to soften up the materials before using a blocking machine with the metal cast created earlier. After that, the hat would go into a hydraulic press with a pressure of about 400 LBS to the square inch. This solidified the desired shape with a proper bit of flexibility.

Finishing: A complete varnishing came next, giving the newborn hat its necessary “gloss and luster.” Then it was off for the final finishing, so to speak, as tips and sweatbands were sewn in by hand. After a final inspection, the hat was sent away to become a pretty thing—either by in-house milliners or a third party dealer.

Frasher was so confident in the company’s hat-making operation that he happily invited anyone in the industry to visit the factory and see his workers in action.

[Clockwise from top left: Hydraulic presses, more pressing, finishing department, sewing department, 1890s]

[Clockwise from top left: Hydraulic presses, more pressing, finishing department, sewing department, 1890s]

High Rising

John Frasher retired for a second time in 1905, and D. B. Fisk & Co. entered into a new era.

“This great house, established in 1853, is now in its fifty-fourth year,” the Illustrated Milliner reported in 1906, “and it is, if possible, more active in the pursuit of business than ever before in its history. . . . Under the influence of the youthful fire and enthusiasm of the new officers, the entire force, down to the youngest stockboy, is imbued with the spirit of progress that has for its object the material increase of the present mammoth business, long known as the Greatest Millinery House in the World.”

The “New D. B. Fisk & Co.,” as locals called it, was initially led by a young hatman named James O’Meara, with Frasher’s son Edward serving as VP. After just two years, however, a power shake-up led to 39 year-old Robert H. Harvey—husband of D. B. Fisk’s granddaughter Bertha Botsford—taking over the presidency. Harvey was actually a graduate of the Northwestern Medical School and a former house physician at Mercy Hospital. As of 1907, though, he was suddenly the king of the millinery world.

The “New D. B. Fisk & Co.,” as locals called it, was initially led by a young hatman named James O’Meara, with Frasher’s son Edward serving as VP. After just two years, however, a power shake-up led to 39 year-old Robert H. Harvey—husband of D. B. Fisk’s granddaughter Bertha Botsford—taking over the presidency. Harvey was actually a graduate of the Northwestern Medical School and a former house physician at Mercy Hospital. As of 1907, though, he was suddenly the king of the millinery world.

“Dr. Harvey is a forceful, outspoken character,” the American Angler noted in 1915, “not given to temporizing or to concealing his opinions. Trained to quickly diagnose a condition and to apply corrective remedies, his mind acts in the same decisive way in business matters as it formerly did in the medical profession. A quick, reflective mind, coordinating circumstances and weighing effects by their various causes, makes immediate action possible with him. . . . As a financier as well as an executive, Dr. Harvey has demonstrated that he has unusual ability. The splendid new building occupied by D. B. Fisk & Co. today is a concrete evidence of his energy and inspiration.”

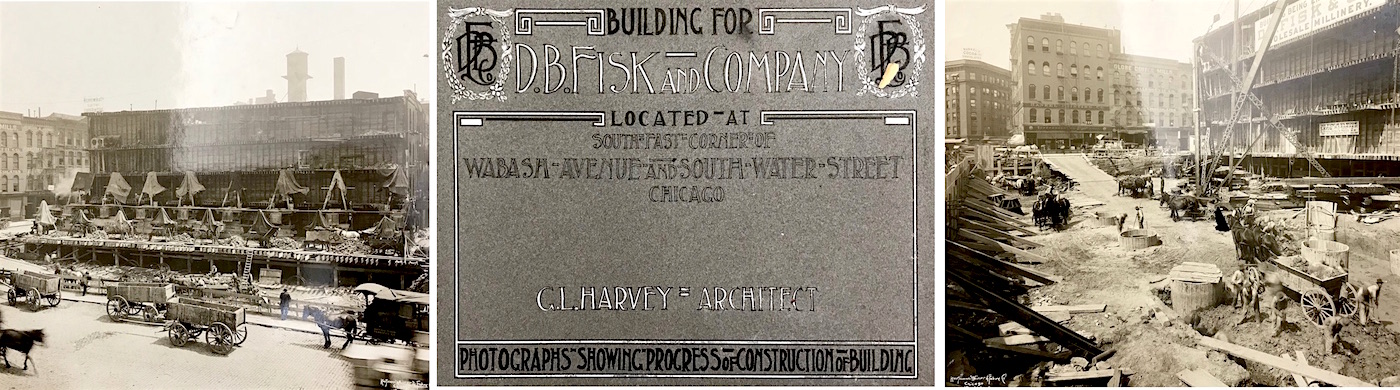

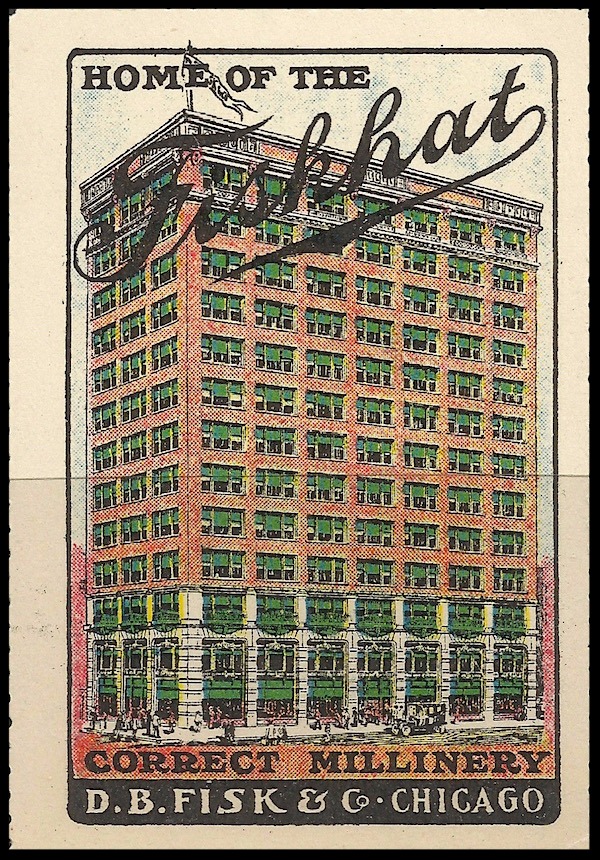

The building referenced above was Fisk & Co.’s last and greatest headquarters, a ridiculous 13-story high-rise at 225 N. Wabash Avenue. It was largely paid for by the estate of Marshall Field, who had wanted the old Fisk building to add on to his department store annex. Dr. Harvey, having less nostalgic ties to the old house, jumped at the chance to move Fisk into the modern age.

[The new Fisk building at 225 N. Wabash, under construction in 1912]

[The new Fisk building at 225 N. Wabash, under construction in 1912]

The American Angler described the new Fisk tower as “embodying the most modern ideas in architecture as applied to a mercantile building. . . . In planning the building, long and careful study was made of the special needs of the millinery business. It is one of the most complete buildings, from sub-cellar to roof, that has ever been put up for mercantile purposes.”

By any measure, 225 N. Wabash was pure 20th century Chicago. Designed from steel, tile, concrete and brick by architect George L. Harvey, it included a complete ventilation system, sprinkler systems and fireproof materials, an in-house electrical power plant, modern elevators, and seemingly endless space for every segment of the business.

By any measure, 225 N. Wabash was pure 20th century Chicago. Designed from steel, tile, concrete and brick by architect George L. Harvey, it included a complete ventilation system, sprinkler systems and fireproof materials, an in-house electrical power plant, modern elevators, and seemingly endless space for every segment of the business.

First Floor: Offices, Customer Rest Rooms and Writing Rooms (“the woodwork and furnishings of this floor are of Circassian walnut, harmonizing with the French grey used throughout”).

2nd Floor to 8th Floor: Sales Departments

9th Floor and 10th Floor: Manufacturing

11th Floor: Printing Office, Lunch Room & Assembling Room

12th Floor: Tailored Hat Department

13th Floor: Party Room (unconfirmed)

[Sales floor of the Fisk Building at 225 N. Wabash]

[Sales floor of the Fisk Building at 225 N. Wabash]

More than 100 years after its opening day on January 1, 1913, the building at 225 N. Wabash is still standing, though it is largely unrecognizable. It was occupied by the Oxford House Hotel from the 1950s to the 1990s, and was systematically stripped of most of its original ornamentation (the mid-century was as brutal on frilly architecture as it was on frilly hats). In the late 1990s, the building was renovated again and eventually converted to its present form as the Hotel Monaco—a fairly nondescript rectangle across the river from the Trump Tower.

[Above: The D. B. Fisk Building in 1915, and its conversion to the Hotel Monaco in 2017. Below: A surviving “ghost sign” on the back of the Hotel Monaco, still visible from E. Wacker Pl. The sign reads, “D. B. Fisk & Co.: MANUFACTURE & IMPORTERS OF WHOLESALE MILLINERY.” The script-style word “Fiskhat” is also still seen.]

Hats Off To You

In the 1920s, when the fairly simple blue “Fiskhat” from our museum collection was likely made, D. B. Fisk & Co. was only a decade into its lease at 225 N. Wabash, and business was better than ever—not just for the company, but the whole industry. Dr. Harvey even penned his own article in the pages of Chicago Commerce magazine in 1920, titled, “Why Chicago Is the Largest Millinery Jobbing City in the World.”

Along with pointing out the obvious—Chicago’s central location and transportation superiority—Harvey credited the circumstances brought about by World War I for improving the city’s status on the world stage… of hats.

“The great war,” he wrote, “with its resulting restrictions of shipping and travel, did much to assist in making the millinery buyers of this country realize the advantage of centering their buying in Chicago. They have found not only the physical advantages, but also that the newest styles were shown in Chicago as soon as they were in the eastern markets.”

With all arrows pointing up, up, up, there seemed no indication that Fisk & Co. was headed for trouble. The business had proven tough enough to handle a great fire, power shake-ups, and major changes of scenery. But an impending stock market collapse was apparently another matter entirely.

With all arrows pointing up, up, up, there seemed no indication that Fisk & Co. was headed for trouble. The business had proven tough enough to handle a great fire, power shake-ups, and major changes of scenery. But an impending stock market collapse was apparently another matter entirely.

On November 3, 1931, just two years after Black Tuesday, the Tribune ran a blurb with the headline, D. B. Fisk & Co. Plan to Quit Millinery Business:

“D. B. Fisk & Co., 225 North Wabash Avenue, wholesale milliners since 1853, will cease active operations, according to an announcement made yesterday. Officials declined to state the reasons for suspension of the business. The offices will remain open temporarily to clear existing stock and to straighten accounts.”

We’re not really privy to the details of just how damaging the market crash was to Fisk’s business, or how that damage manifested itself. On the most obvious level, a lot fewer people were going out and purchasing stylish hats in 1930 vs. 1929. And while one might presume a giant industry leader could handle these losses better than a small mom-and-pop shop, Fisk’s overhead was beyond enormous—and this made them only as invulnerable as the Titanic.

Surrender to the Depression was not absolute, however. In 1932, Fisk & Co. gave up its high-rise building, but re-organized as a much smaller company, with former vice president Joseph C. Beckmann taking over as president, and Robert Harvey, now 64, serving as an advisor. The company endured a humbling move down the street into just one floor of the Kodak Building at 133 North Wabash. They shrunk their circulation mostly to the Midwest, and cut staff down to a manageable core group. It was D. B. Fisk & Co. in name only.

Nonetheless, the new business did carry on, with some production still in evidence after World War II. By the 1950s, however, just as women started shampooing their hair more than once a month, the well began to dry up. Demand for the once legendary Fiskhats had quieted to a murmur, and the firm—at a time the greatest perhaps on the planet—disappeared for good.

Sources:

“Rebuilt Chicago: D. B. Fisk & Co.’s New Store” – Harper’s Bazar, April 19, 1873

Monitor of Fashion, 1896: March, September, October

D. B. Fisk & Company, 1913 Catalog

D. B. Fisk & Co., 1900 Catalog

David B. Fisk Letter to Mother, November 1871 (Chicago History Museum collection)

Chicago: Its History and Its Builders, Vol. 5, by Josiah Seymour Currey, 1912

King’s Handbook of the United States, by Moses Foster Sweetser, 1893

“D. B. Fisk & Co. Quit Business, Form New Firm,” Chicago Tribune, Jan. 9, 1932

“Why Chicago Is the Largest Millinery Jobbing City in the World,” by Dr. Robert Harvey, Chicago Commerce, Vol. 16, 1920

The American Angler, Vol. 3-4, 1915

“Death of D. B. Fisk” – Daily Inter Ocean, July 30, 1891

Fiske and Fisk Family: Being the Record of the Descendants, by Frederick Clifton Pierece, 1896

History of Chicago: From 1857 Until the Fire of 1871, by A. T. Andreas, 1885

A History of Chicago, Volume III: The Rise of a Modern City, 1871-1893, by Bessie Louise Pierce

Origin, Growth, and Usefulness of the Chicago Board of Trade: Its Leading Members, and Representative Business Men in Other Branches of Trade, 1885

Millinery Trade Review, Vol. 31, 1906

The Illustrated Milliner, Vol. 7, 1906

Annual Report of the Factory Inspector of Illinois: 1897-1898

“A Loop Hotel That’s More Than Just a Place to Hang Your Hat,” ChicagoArchitecture.org

Archived Reader Comments:

“What a great story. My grandfather was Joseph C Beckmann who purchased and operated D B Fisk into the 1950’s. “–Louis Holian, 2020

“–Louis Holian, 2020

“My grandmother worked there for 1 or 2 pennies a hat…my dad was born 1927, when she worked there…” —Gail, 2019

“Terrific and very informative article. Obviously I need to visit the museum! ” —I Sholder, 2019

” —I Sholder, 2019

“I am impressed! While I research Chicago millinery, I have done little about Fisk. Sort of got caught up in the world of Sarah Gale the first Chicago milliner, here in 1835, and a few dozen others. Thrilled to see the letter about the fire DB wrote to his mother. It is a gem of a thing in that small amount of Fisk material in the CHM Research Center. The 1860 census has DB’s worth as $12K in real estate, and $10K in personal estate. He prospered over the next decade. In 1870 it was $50K in real estate and $100K in personal estate, according to the census. The fire rebuild would have significantly tapped into his savings, but it paid off nicely.” —Mary Robak, 2019

I am researching the life and times of Madam Seay of Seay Millinery 3641 State Street, Chicago. Mrs. Frank Seay aka Maude Mae Seay was the prosperous designer and owner of Seay millinery. Madam Seay learned the Millinery trade at Griffith’s “Importer of Millinery.” She established Seay Millinery in 1908. She married Frank Seay in 1902 and divorced him in 1909, retaining the attorney Beauregard Fitzhugh Mosely of the Leland Giants. She sold the business to Mayme Clinkscale in 1914/1915, who established the Style Shop.

I’m looking for the name of a hat factory that was located at 4315 S. Wabash, Chicago. It is now the First Deliverance Church. Does anyone know anything? Also, how many hat factories were located in Chicago.

Thanks

There was a street named Fisk Street that was essentially taken over by the construction and running of Commonwealth Edison generating plant starting in 1903 at 1111w Cermack Road. Was the street named after D B Fisk?

It would be fun to add onto the history of this article that the memory of Fisk & Co was eventually honored by the Hotel Monaco! The hotel created a brand new restaurant concept and redid their entire restaurant- and stylized their logo, fashion and decor, even naming some areas of their rooms to honor the history of Fisk.

The restaurant is actually called Fisk & Co!!!

The logo is a cat – eating a fish – wearing a Fisk hat.

Fisk also means fish in Swedish, and several other languages. Which is why seafood is one of the restaurants specialties. They also call their main event space “the millinery.”

The Hotel Monaco was recently sold to a hotel company that is from outside the US. This restaurant will only be around for the rest of 2022- early 2023.

Its very likely that this will be the last time Fisk & Cos memory will be shown in large lettering on 225 N Wabash to honor the buildings history!

Please see it while you can and add the end od the story to this article!

I have a wood Hat Block stamped;

____MILLER SCHOOL OF MILLINERY

225 N. Wabash Ave.

Chicago, 1, Ill.

Could you ell me what years this would be from?

the name before Miller is not readable.

I have a fisk hat not sure how old perfect mint condition in box like to have more info on it

I found a very old sewing machine that says “Fisks Special” on the side. Any ideas about this?

The thick-billed parrot was also found in the southwestern United States.

So the Carolina parakeet was not the only parrot native to that country.

Thick-bills died out in the U.S in 1935, but still survive south of the border in Mexico. They are now endangered there as well.

A reintroduction attempt happened in the 80’s and 90’s in Arizona, but failed, due to multiple factors.