Museum Artifact: Glass Carafe and Warmer, 1950s

Made By: Inland Glass Works (aka Inland Glass Co.), div. of Club Aluminum Products Co. 6101 W. 65th Street, Chicago, IL [Clearing]

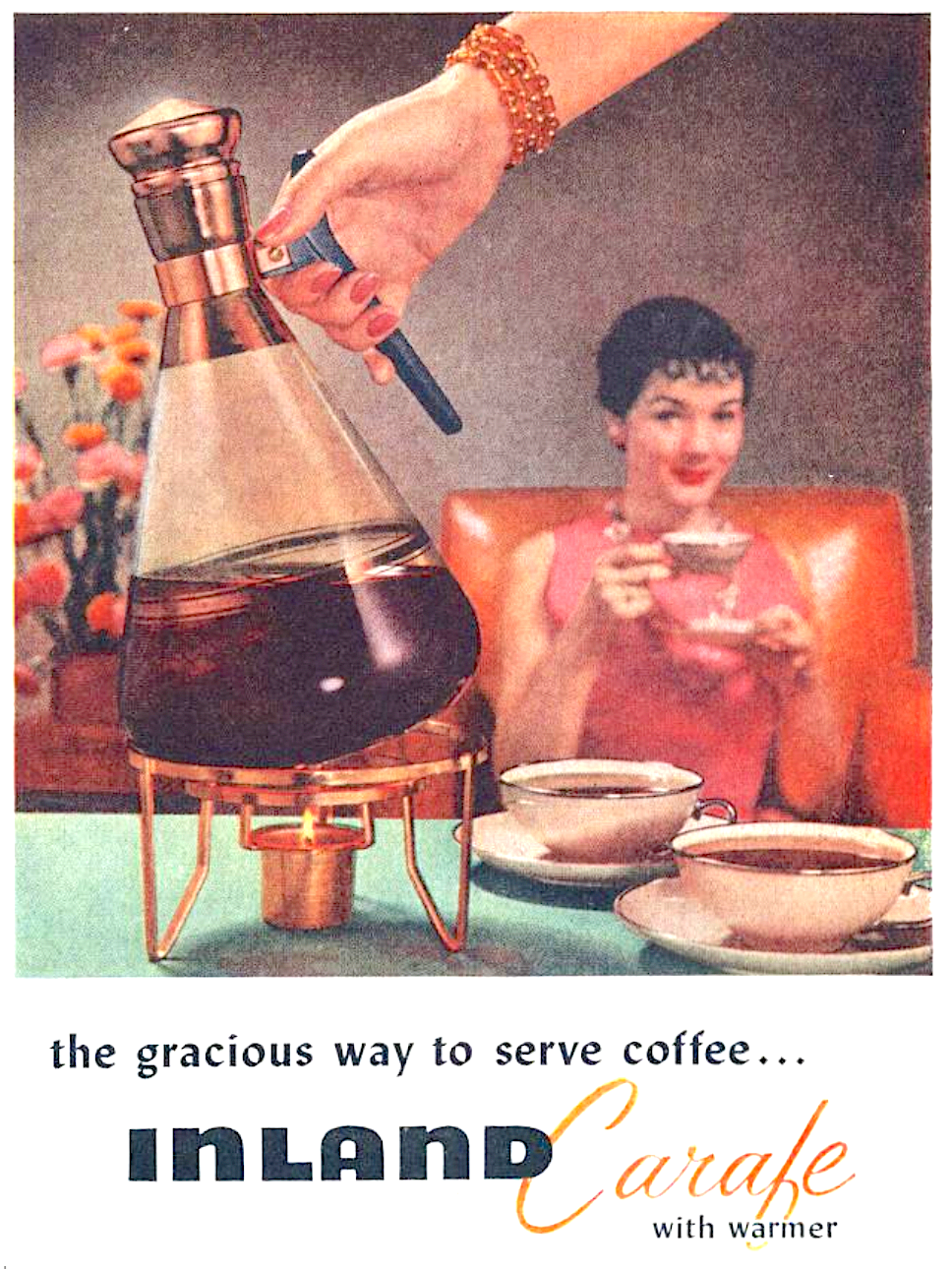

“Center of attention . . . your fashionable INLAND Carafe! Family and guests will love the scintillating beauty of this hand-blown glass server, smartly trimmed in either gleaming copper or platinum. Matching tripod candle warmer adds charm, keeps coffee piping hot. Perfect for buffet suppers, informal entertaining, casual living.” —Inland Glass advertisement, 1955

The Space Age carafes produced by the Inland Glass Works during the 1950s probably represent the company’s only lasting, widely recognized contribution to American glass manufacturing. It feels like short shrift, though, to reduce this business to one-note or footnote status. In Chicago, where glassmaking was never the industry du jour, Inland briefly gave the city its best hope at competing on the national stage—throwing its proverbial stones at the big glass houses of the East.

The Space Age carafes produced by the Inland Glass Works during the 1950s probably represent the company’s only lasting, widely recognized contribution to American glass manufacturing. It feels like short shrift, though, to reduce this business to one-note or footnote status. In Chicago, where glassmaking was never the industry du jour, Inland briefly gave the city its best hope at competing on the national stage—throwing its proverbial stones at the big glass houses of the East.

It didn’t exactly begin with a humble glass blower and a dream, either. Founded in 1922, Inland Glass was a bold, blatant, and immediate swing for the fences—financed by a unique partnership of established Chicago tycoons, including the company’s first president Joseph B. Weaver (Pullman Company) and fellow board members John T. Pirie (Carson, Pirie, Scott & Co.), Laurence Armour (Armour & Co.), Robert P. Lamont (American Steel), and Philip K. Wrigley (Wrigley Co.).

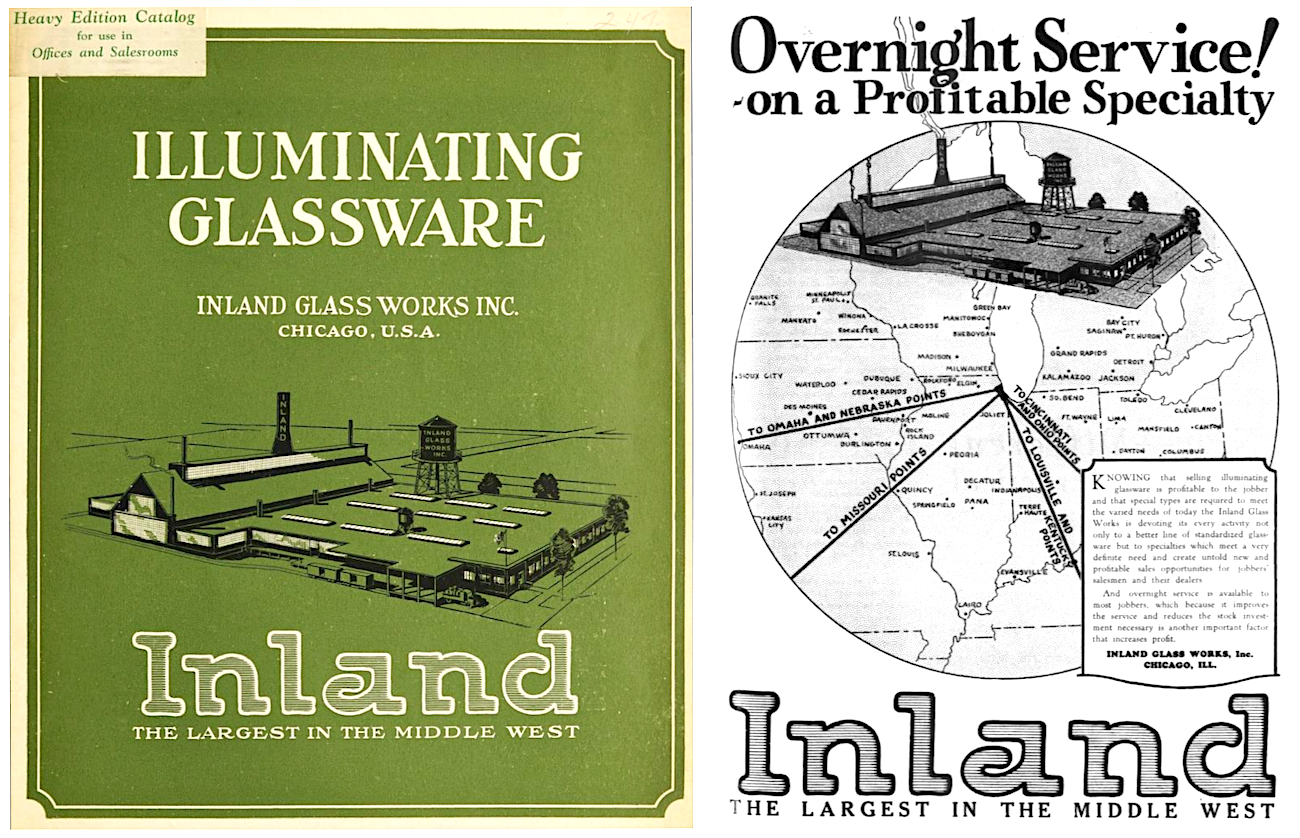

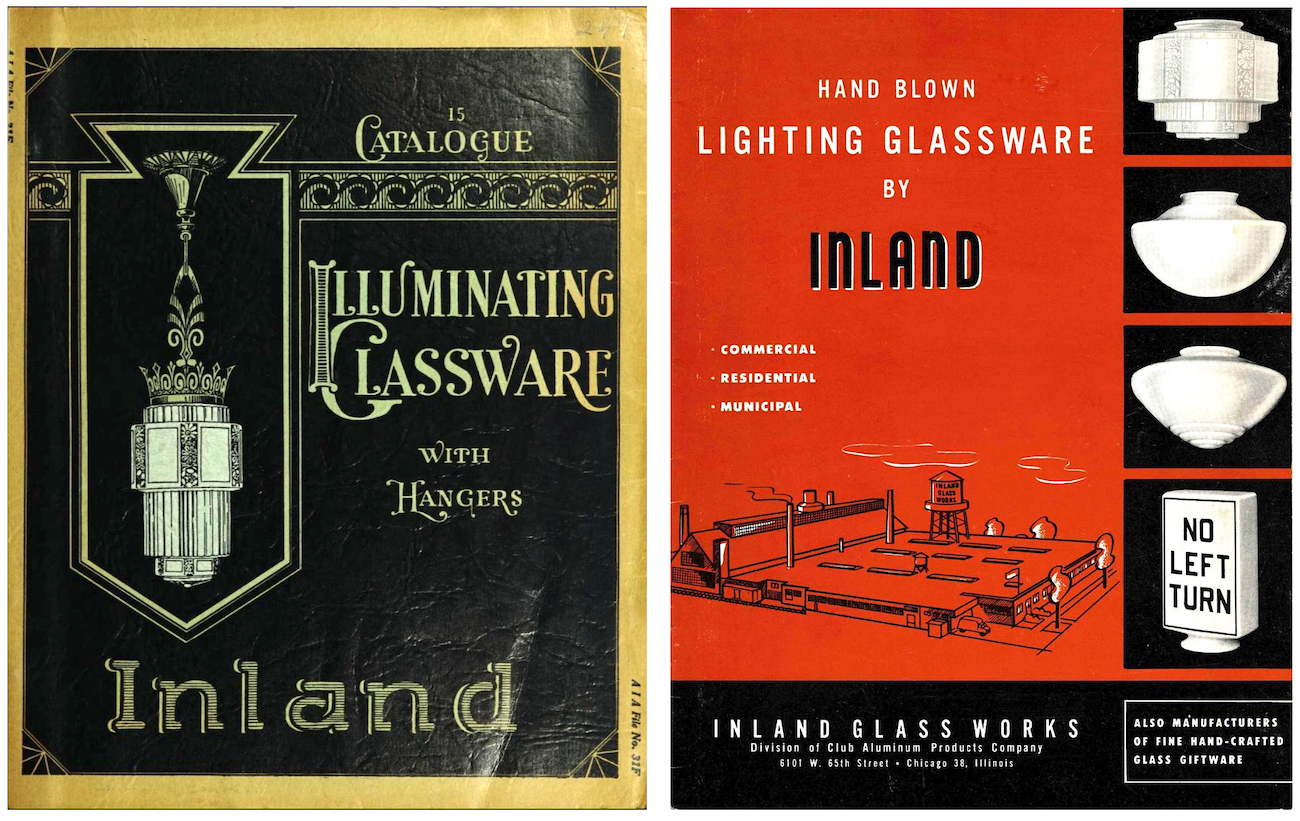

With that hefty backing and a state-of-the-art new factory in the city’s Clearing Industrial District, the Inland Glass Company arrived to much fanfare, both locally and across the national glass marketplace. Originally focused on lighting fixtures (“illuminating glass”), the firm eventually moved into kitchenware in the 1930s, and while sales were reasonable, it’s safe to say that they never quite lived up to the expectations of the company’s founders (i.e., total world domination). After it was acquired by Chicago’s Club Aluminum Products Co. in 1951, the business did enjoy a carafe-led spike in notoriety, but by the mid ’60s, the factory was permanently shut down . . . not with a crashing sound, as one might expect from a glass works, but a mere murmur, like a slow return to it products’ earthly origins.

For a little while there, though, the Inland Glass Company ably reflected the skill of its workforce, pushing forward new methods of commercial glass production and making some memorable contributions to the look of mid-century kitchenalia.

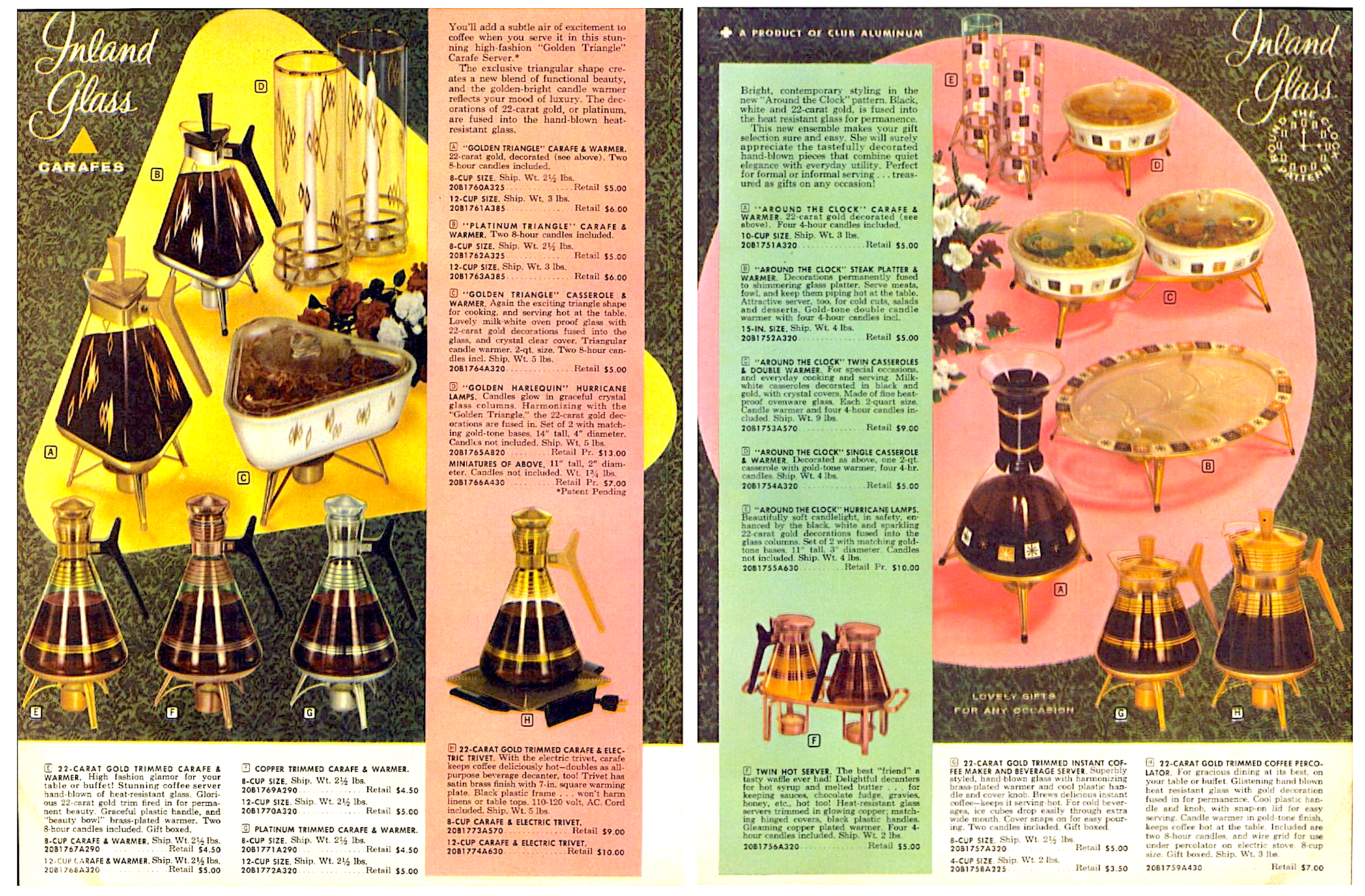

[1960 magazine ad for Inland Glass carafes and serving trays]

History of the Inland Glass Works, Part I: A Glassmaking Dream Team

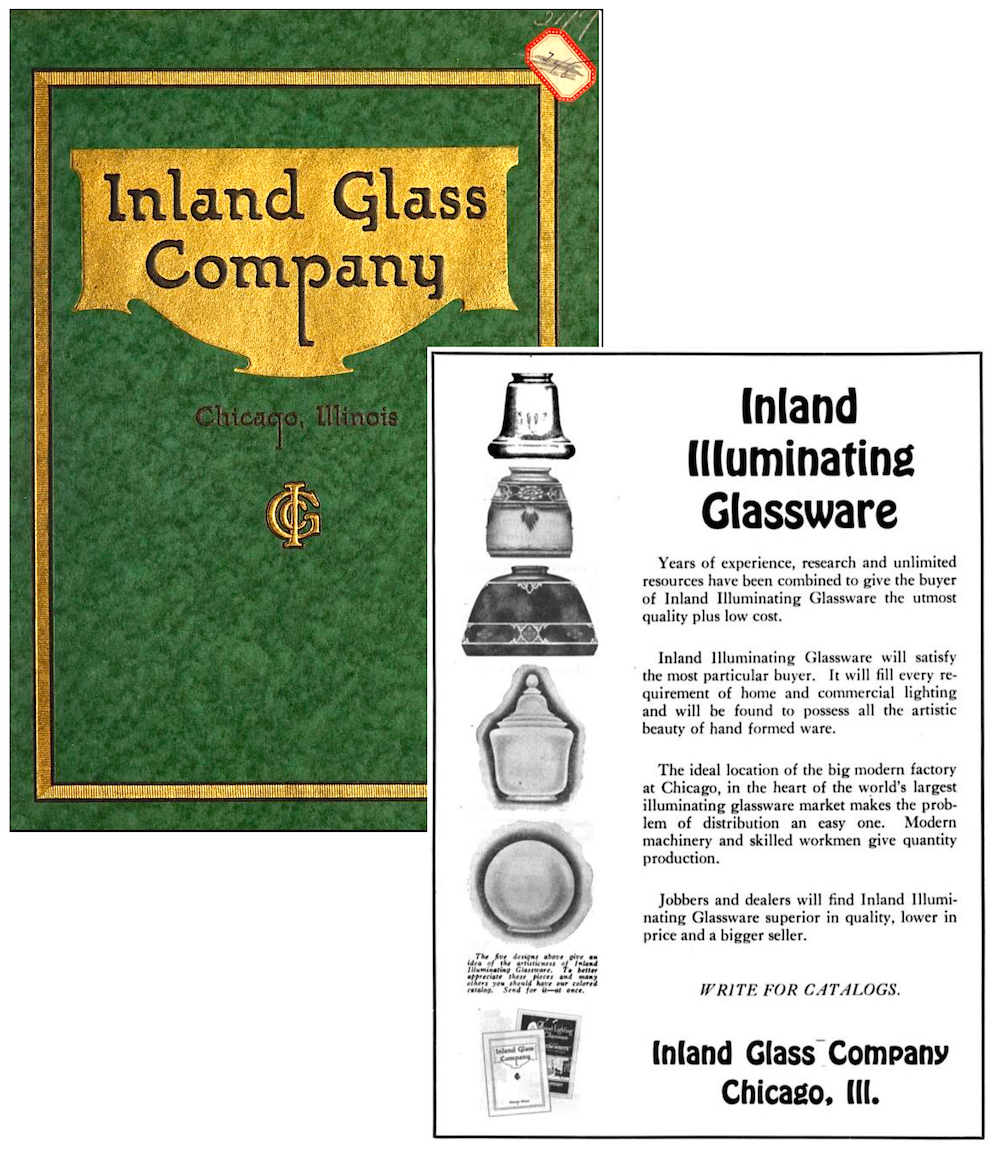

“As Chicago grows, the diversity of its industrial enterprises increases. The latest important addition is the Inland Glass Company, a new concern formed to produce illuminating glassware and located at 6101 W. 65th Street.” —Chicago Commerce, March 1923

Incorporated for $750,000 (equivalent to about $13 million in 2023), the Inland Glass Company broke ground on its $500,000 ($9 million) factory in September of 1922 and started rolling out product just five months later. The Chicago Tribune described the new firm as “the only one of its kind west of Pittsburgh,” but since Ohio was already home to a half dozen famed glassware companies by this point, we’ll assume this claim was specific to the wide-scale production of glass lighting fixtures, which was Inland’s primary focus upon its launch.

Incorporated for $750,000 (equivalent to about $13 million in 2023), the Inland Glass Company broke ground on its $500,000 ($9 million) factory in September of 1922 and started rolling out product just five months later. The Chicago Tribune described the new firm as “the only one of its kind west of Pittsburgh,” but since Ohio was already home to a half dozen famed glassware companies by this point, we’ll assume this claim was specific to the wide-scale production of glass lighting fixtures, which was Inland’s primary focus upon its launch.

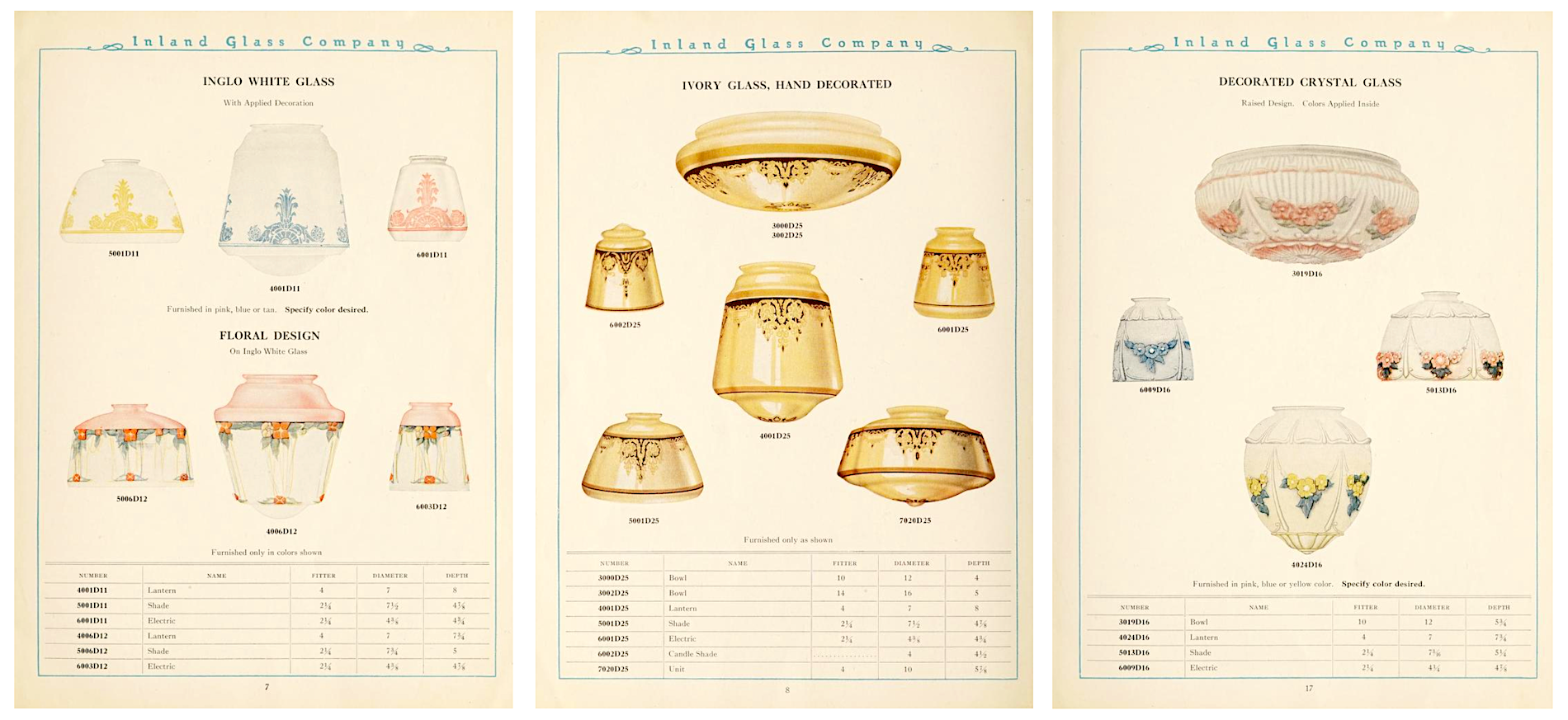

“We believe we have succeeded in creating a line of glassware which will satisfy the most particular buyers,” the company announced in the introduction to one of its first catalogs, “. . . a line of glassware that will suit every requirement for commercial use and for home lighting, rich in artistic detail, and in keeping with the more advanced modes of interior decoration.

“No expense has been spared to present to the trade a quality of glass that will render the utmost in beauty and efficiency.”

[Images from Inland Glass’s second catalog, 1923]

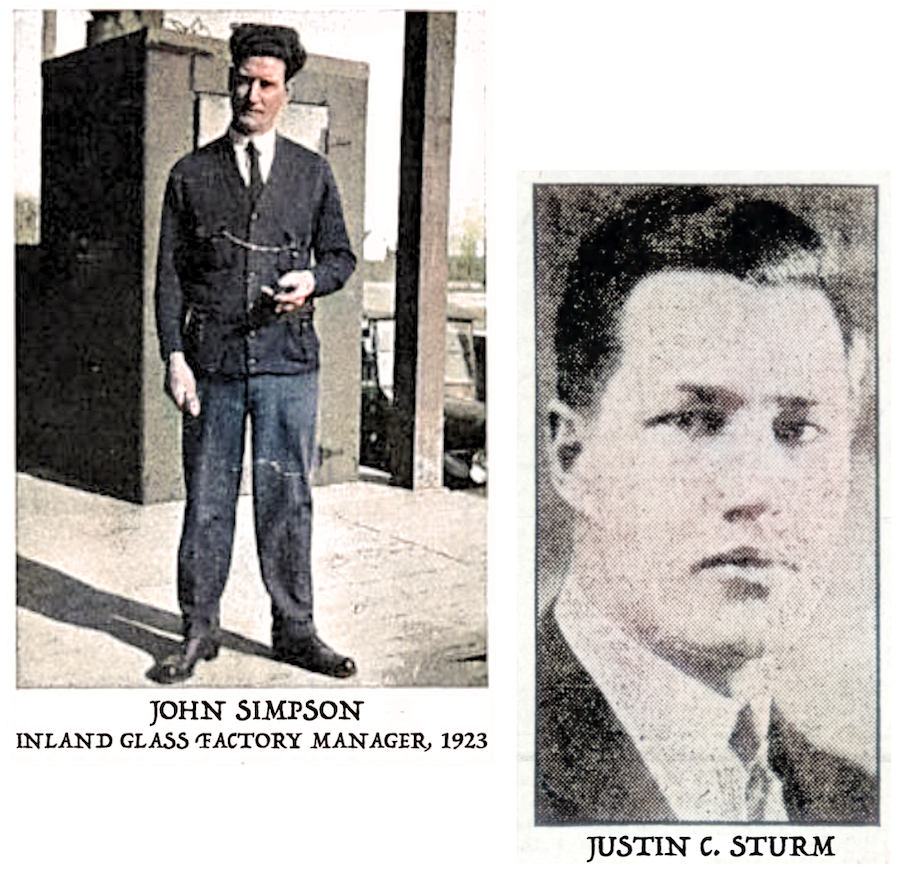

Inland’s cigar-chomping investors poured much of their money into new machinery. “We have replaced,” they noted in their catalog, “to a great extent, the old methods of hand manufacture with the more exacting and scientific automatic methods.” To their credit, though, they also recognized the importance of seasoned leadership, and made a point of poaching talent from some of the leading glass companies in Ohio and Pennsylvania. Among these five-star recruits were Inland’s original superintendent Ernest Vogel, general manager Fred W. Stewart, designer Florence L. Grant, and factory manager John A. Simpson.

Another notable early employee with the firm was a young engineer named Justin Cornelius Sturm, son-in-law to Chicago’s powerful McCormick family and later a well regarded artist and sculptor. Sturm’s son, Alexander McCormick Sturm, would go on to marry Teddy Roosevelt’s granddaughter in the 1940s and co-found what is now one of the country’s largest firearm manufacturing companies (Sturm-Ruger). This isn’t wildly relevant, perhaps, but it offers a sense of the type of folks you might meet in a glass factory fully funded by some of Chicago’s wealthiest men.

“The company could not have selected any better men for the positions and the company is to be congratulated,” praised the American Flint, the magazine of the Glass Workers Union, in 1923. “These men have the practical knowledge and experience; they know the needs of the workers and the facilities required.

“The company could not have selected any better men for the positions and the company is to be congratulated,” praised the American Flint, the magazine of the Glass Workers Union, in 1923. “These men have the practical knowledge and experience; they know the needs of the workers and the facilities required.

“Everything is being done to make the work easier for the men and conditions at this plant surpass any that the writer has ever seen in any glass plant in the United States or Canada.”

As with many of the new factory buildings popping up in Chicago during the Roaring ‘20s, the Inland Glass Works embraced the novel concept of worker comfort as a means of retaining skilled employees. The plant included showers, lockers, natural light, and plenty of space between departments.

“The workmen enjoy working in this plant, and the treatment accorded to them by the management is surely appreciated,” the American Flint reported. “They are endeavoring to show that appreciation by service to the concern.”

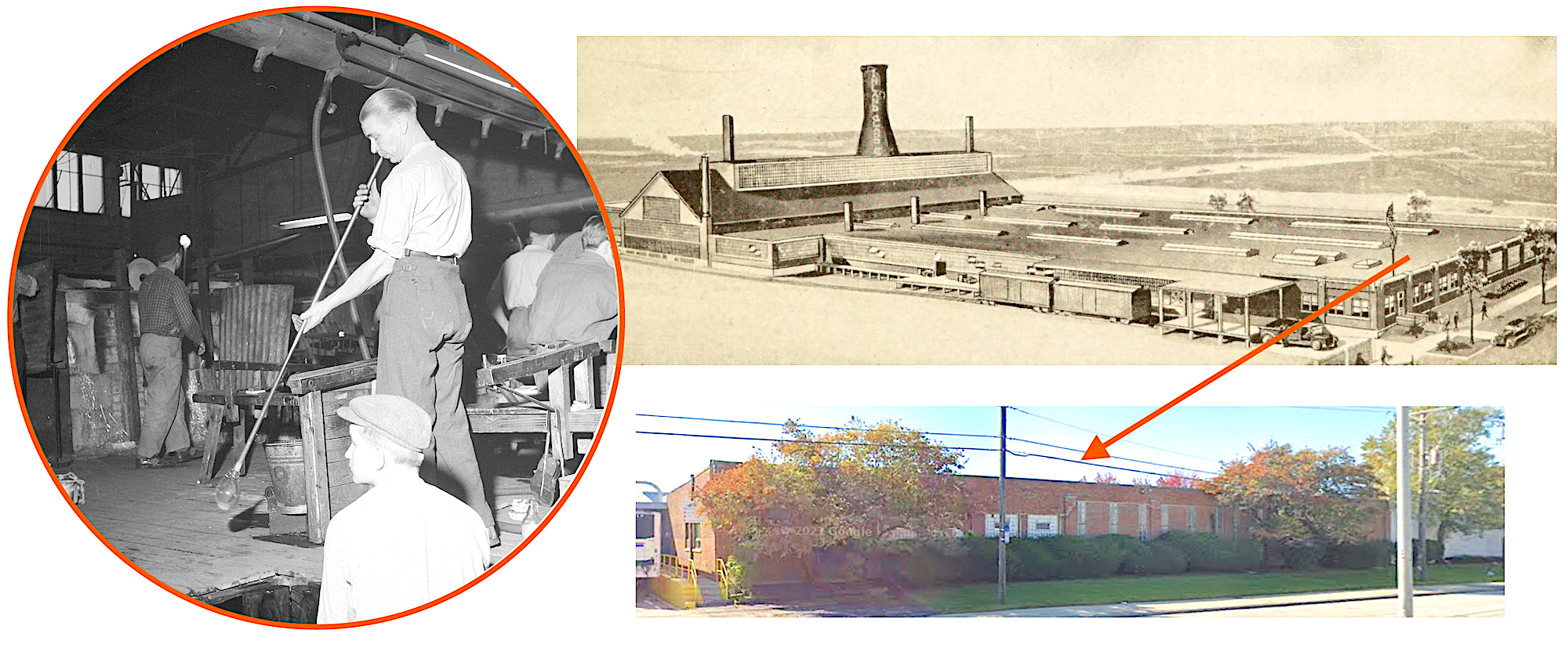

[Left: This photo is NOT from the Inland Glass plant, but a Finnish glass works of the same period, c. 1920s, showing old methods combined with new industrial capabilities. Right: Sketch of the Inland Glass plant at 6101 W. 65th Street in what is now Bedford Park, 1923. Some parts of the complex are still standing today, as seen in the 2019 photo.]

At a banquet toasting the opening of the plant in the spring of 1923, factory manager John Simpson told a gathering of recently transplanted union workers that he had selected each of them from a pool of 300 applicants because he “recognized their ability as workmen,” but also added that “we must have men that are reliable and dependable.”

Superintendent Vogel added that “nothing would be left undone to make conditions pleasant for the workmen, and hoped that the spirit of co-operation would be manifested towards the company by the men.”

Vogel was applauded by the workers that night, but the good vibes didn’t last very long. After a seemingly disappointing first year, amid pressure from the board, Vogel was pushed to hand in his resignation, and several of his allies followed. A new superintendent, Cornelius J. Nolan, was brought in from the Libbey Glass Co. in Toledo, Ohio, and immediately got things back on track, expanding the plant’s production by more than 50 percent. Unfortunately, a sudden illness led to Nolan’s death in 1926 at just 58 years of age.

Vogel was applauded by the workers that night, but the good vibes didn’t last very long. After a seemingly disappointing first year, amid pressure from the board, Vogel was pushed to hand in his resignation, and several of his allies followed. A new superintendent, Cornelius J. Nolan, was brought in from the Libbey Glass Co. in Toledo, Ohio, and immediately got things back on track, expanding the plant’s production by more than 50 percent. Unfortunately, a sudden illness led to Nolan’s death in 1926 at just 58 years of age.

This seemed to be the final straw for Inland’s original investors. Feeling like they’d never see the returns they’d hoped for, they began looking for a way to unload the business, and eventually found a buyer in the form of George L. Chamberlain, president of a Chicago electrical contracting firm known, rather boldly, as the U.S.A. Company.

By the end of 1928, Chamberlain had completely re-organized the business, installing veteran employee Joseph H. Allen as its new president and relaunching the company as the Inland Glass Works, Inc., a division of Chamberlain, Inc.

Stability was never the calling card of this firm, and the early years of the Chamberlain era wouldn’t change that narrative.

[1928 Inland Glass catalog and advertisement]

II: A Division of Chamberlain, Inc.

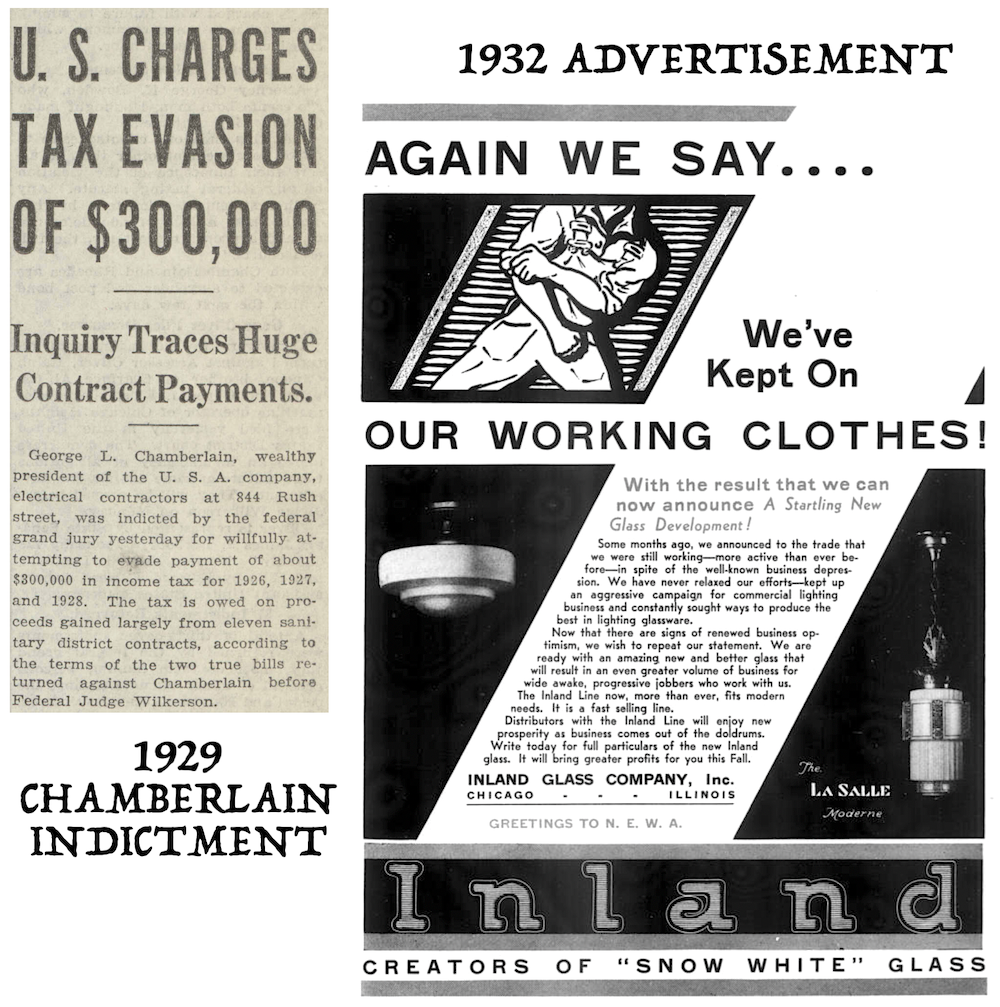

Almost from the moment he took over the Inland Glass Works, George Chamberlain was in hot water, both financially and legally. First came the stock market crash of 1929, then—just months later—a pesky indictment for tax evasion. It seems that Chamberlain’s U.S.A. Company had bribed some of Chicago’s notoriously ethical city officials to win a lucrative contract installing ornamental street lights on McCormick Blvd., then didn’t properly reports his earnings on the deal.

Chamberlain battled the charges in court for the next five years, and eventually came to a settlement, but the distraction did no favors to his new glass manufacturing acquisition, nor did the sad state of the U.S. economy. All one could do was put on a brave face.

Chamberlain battled the charges in court for the next five years, and eventually came to a settlement, but the distraction did no favors to his new glass manufacturing acquisition, nor did the sad state of the U.S. economy. All one could do was put on a brave face.

“Some months ago, we announced to the trade that we were still working–more active than ever before–in spite of the well-known business depression,” read a 1932 Inland Glass advertisement. “We have never relaxed our efforts–kept up an aggressive campaign for commercial lighting business and constantly sought ways to produce the best in lighting glassware. Now that there are signs of renewed business optimism, we wish to repeat our statement. We are ready with an amazing new and better glass that will result in an even greater volume of business for wide awake, progressive jobbers who work with us. The Inland Line now, more than ever, fits modern needs.”

By the latter half of the 1930s, though, Inland could no longer rely on just being an “illuminating glass” business. Survival required diversification, and the factory soon pushed more lines, particularly heat-proof glass for coffee brewers and servers. A sales and display office was established in the Merchandise Mart, Chamberlain’s executive offices were set up at 841 N. Wabash Avenue, and more investments were put into the 65th Street factory.

“At the present time the factory is busy getting out orders for coffee brewers, percolators, and chemical glass,” veteran employee Emil Nelson wrote to the American Flint in 1938. “The Factory Department consists of eight day tanks and two continuous tanks from which pressed and blown ware is made. Day by day we can see new improvements and equipment being installed, and within the past year this company has spent well over $100,000 on such improvements.”

“At the present time the factory is busy getting out orders for coffee brewers, percolators, and chemical glass,” veteran employee Emil Nelson wrote to the American Flint in 1938. “The Factory Department consists of eight day tanks and two continuous tanks from which pressed and blown ware is made. Day by day we can see new improvements and equipment being installed, and within the past year this company has spent well over $100,000 on such improvements.”

New efforts were also made to connect with the community, as Inland would send out some of its skilled glass blowers for promotional demonstrations at stores, conventions, and festivals.

During one such demonstration at Cicero Stadium in 1938, “the expert glass blower from the Inland Glass company [Oscar Anderson] built up a steady clientele of watchers at his booth,” according to the Berwyn News. “Tricks that he does with his tube, molten glass, and blue flame are little short of miraculous and never fail to impress the visitor. Beautiful glass ornaments and miniature oddities are among the articles he creates before the eyes of amazed onlookers.”

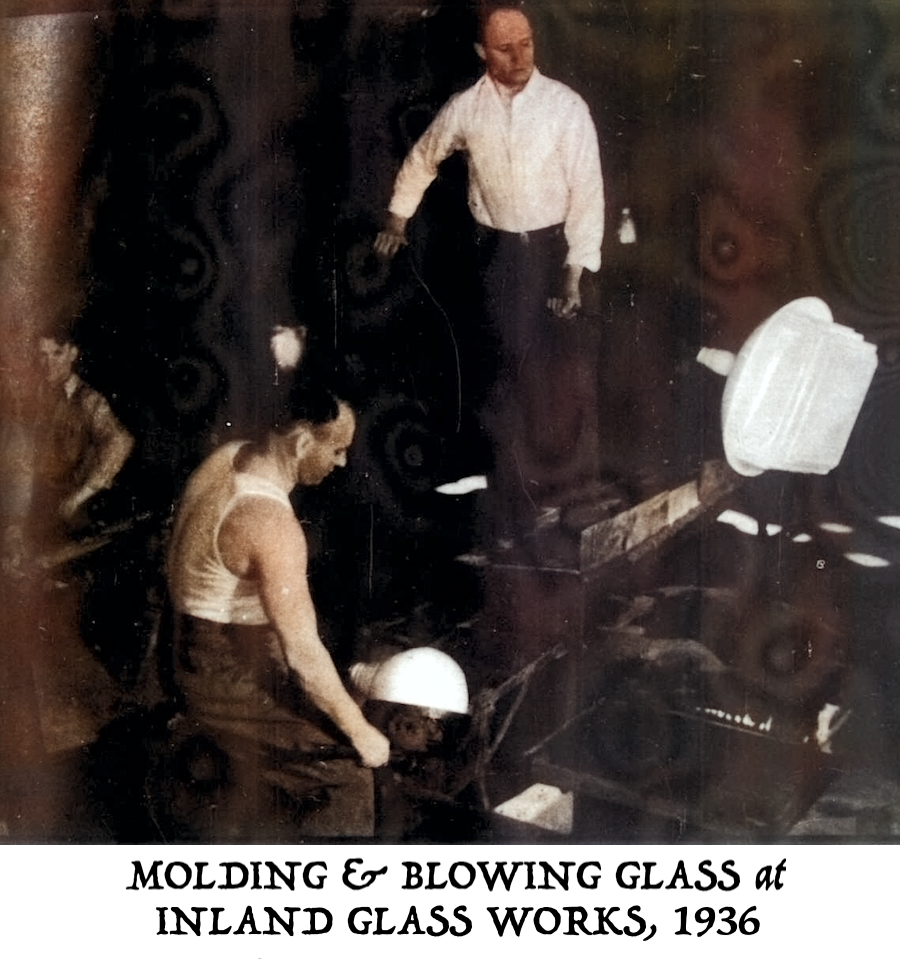

[Inland Glass employees Oscar Anderson (left) and Emil Nelson run a glass blowing demonstration during Chicago’s Blue Flame Exhibition in Cicero Stadium, October 1938. Smaller glass novelties made during these shows were then made available to spectators as keepsakes.]

Even as its catalog evolved, Inland Glass maintained its association with beautiful, decorative glass, rather than the practical, utilitarian type. During World War II, however, staying in business meant ensuring that one’s products were necessities of daily American life, as opposed to luxuries.

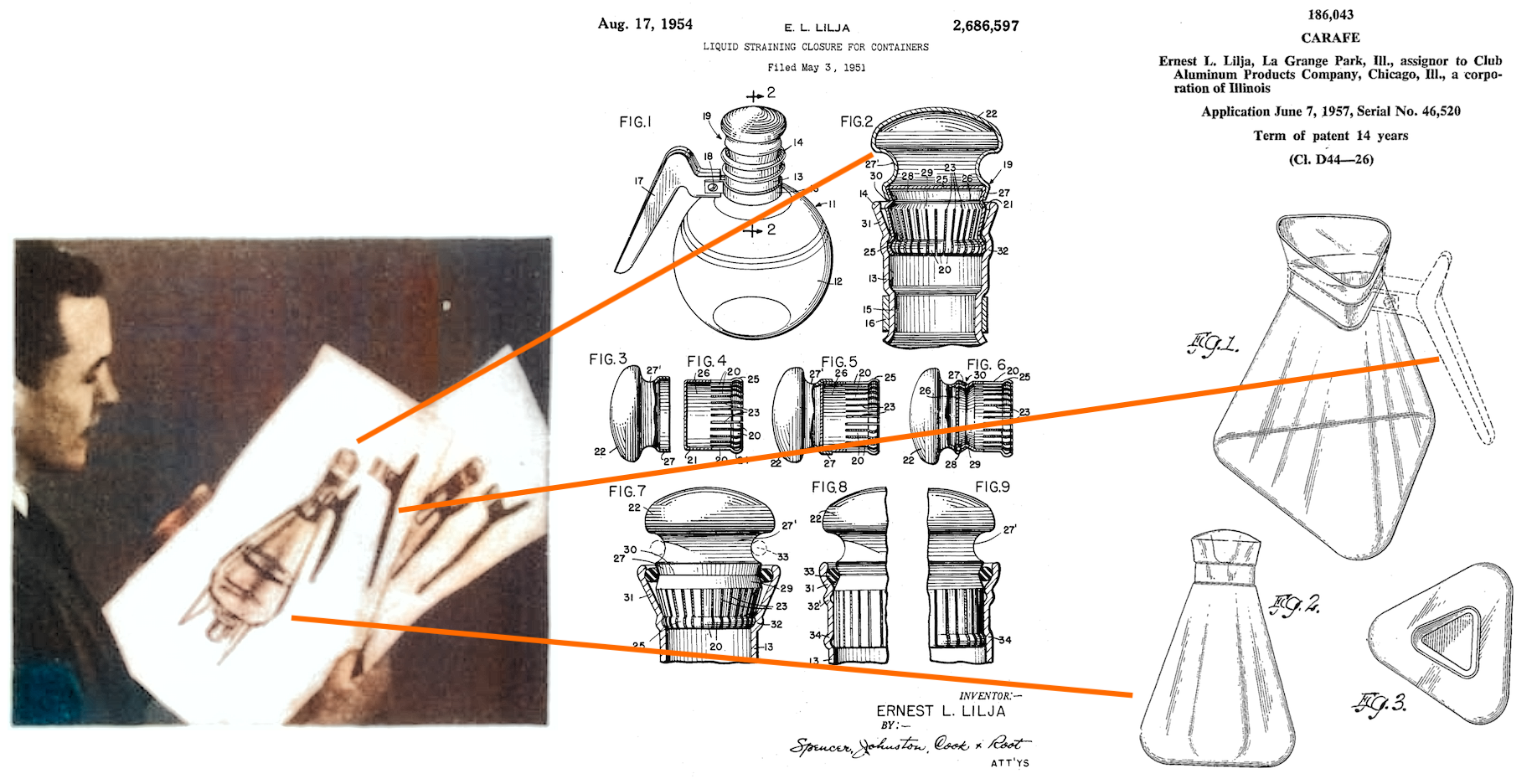

Product developers John G. Francis and Ernest L. Lilja collected a handful of patents for Inland Glass in the 1940s, mostly based around adapting “laboratory glass” into heat-resistant vehicles for coffee and tea. They marketed these products as “hand blown Triple XXX heatproof glass,” which makes it sound perhaps a little more exciting than it actually was.

Lilja, who joined Inland Glass in 1933 and became its general manager in 1947, is the man most associated with Inland’s successful foray into stylish carafes in the post-war years. It was his work, in fact, that likely kept the company appealing enough for another investor to take interest.

[A pair of Ernest Lilja patents that contributed to Inland Glass’s popular line of carafes in the 1950s]

III. A Division of Club Aluminum

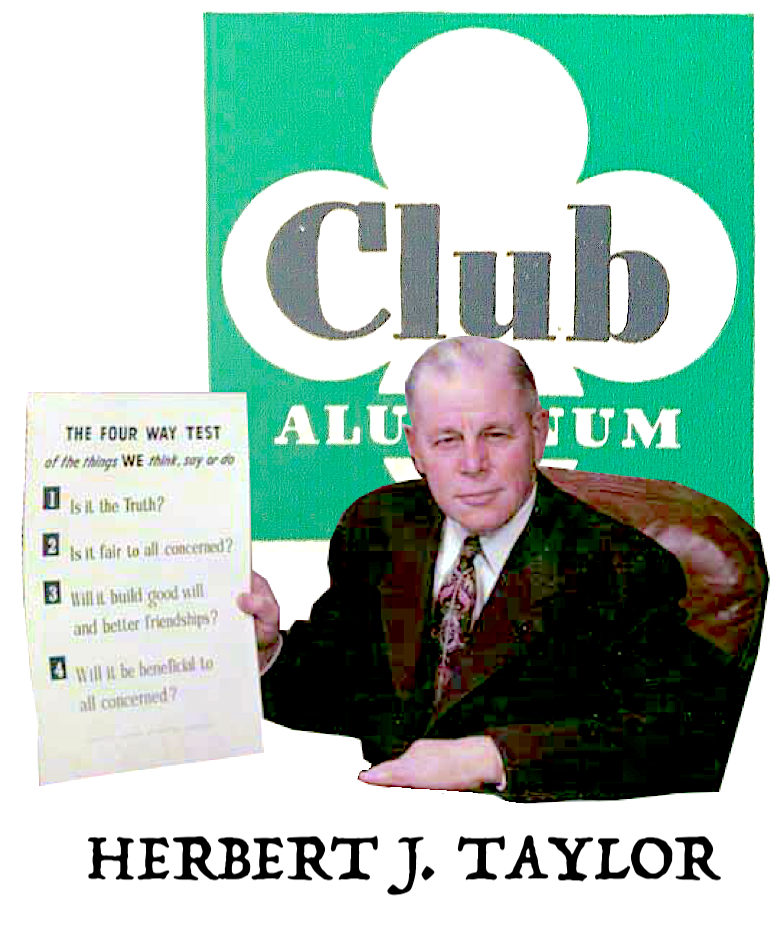

In 1951, Chamberlain, Inc., sold the Inland Glass Works and its Chicago factory to the Club Aluminum Products Company—a Chicago-based housewares manufacturer. Club Aluminum’s chief executive, Herbert J. Taylor, was something of a celebrity among businessmen of the period. Along with saving Club Aluminum from bankruptcy in the 1930s and turning it into a successful national brand, he was also a director of Rotary International and a major spokesman for the application of Christian values in business. Taylor’s “Four-Way Test” for applying ethics to business decisions was adopted by Rotary and was highly influential for years. The “test” involved asking one’s self the following questions:

1. Is it the truth? 2. Is it fair to all concerned? 3. Will it build goodwill and better friendships? 4. Will it be beneficial to all concerned?

Taylor, despite his emphasis on goodwill, was not a fan of worker’s unions, and acquiring Inland Glass meant having to deal with the demands of several such organizations. “Most strikes and lockouts and industrial strife,” he once said, “can be traced directly to selfishness, insincerity, unfair dealings, or fear or lack of friendship among the men concerned.” To avoid such issues with Inland, he naturally applied his Four-Way Test into negotiations with the glass workers. Most employees kept their jobs after the 1951 sale, and general manager Ernest Lilja became vice president of what was now Club Aluminum’s official “glass division.”

Taylor, despite his emphasis on goodwill, was not a fan of worker’s unions, and acquiring Inland Glass meant having to deal with the demands of several such organizations. “Most strikes and lockouts and industrial strife,” he once said, “can be traced directly to selfishness, insincerity, unfair dealings, or fear or lack of friendship among the men concerned.” To avoid such issues with Inland, he naturally applied his Four-Way Test into negotiations with the glass workers. Most employees kept their jobs after the 1951 sale, and general manager Ernest Lilja became vice president of what was now Club Aluminum’s official “glass division.”

“Taylor also responded to the union demands for improved working conditions,” according to the 1990 Taylor biography God’s Man in the Marketplace. “The presence of ‘the Test’ in contract negotiations made it difficult for the management to ignore their requests.”

Once again, the Inland Glass Works began a new era, and like many housewares businesses of the 1950s, their products increasingly reflected the optimism of the age. Lilja’s carafes felt hyper modern and vaguely scientific and with their combination of narrowing lab glass and tripodal heat stands, but they also included sleek lines, copper accents, and a phenolic, flame-resistant plastic handle, all of which made them quite the nifty addition to a suburban middle class dinner party.

“Inland Carafes for Gracious Serving,” reads the tag to the carafe in our museum collection. “All of the skills of Old World glass blowing are combined in this Carafe of modern design. It is hand blown from Inland’s famous Triple XXX heatproof glass. The decorations have been fired into the glass to provide permanent lustre under constant use.”

In the early 1960s, Inland Glass briefly produced a line of “Renaissance” themed serving accessories, featuring quite lovely looking stained glass panels fired into the exterior. These products, like the ‘50s carafes, are still quite popular among collectors today. Unfortunately, they also mark something of a grand finale for the Inland Glass Works.

In the early 1960s, Inland Glass briefly produced a line of “Renaissance” themed serving accessories, featuring quite lovely looking stained glass panels fired into the exterior. These products, like the ‘50s carafes, are still quite popular among collectors today. Unfortunately, they also mark something of a grand finale for the Inland Glass Works.

“Work is very slow here and it doesn’t look as if it will improve in the near future,” Inland employee Lillian Johnson reported to the American Flint magazine in 1961, speaking on behalf of Glass Workers Union Local No 516. She was quite correct. Competition from mass-produced machined glass—not to mention plastics and stainless steel—was rapidly reducing Inland’s product to the tiniest of niches.

After about 40 years in business, and plenty of restructuring and turmoil, Chicago’s great glass hope was officially liquidated by Club Aluminum in 1963. According to legend, Herbert Taylor at least remained true to his Four Way Test when he dropped the ax. He made sure every employee of Inland Glass had found work elsewhere before he shut down the plant for good.

[An Inland Glass carafe making a cameo in the first season of Twin Peaks, courtesy of twinpeaksblog.com]

Sources:

“Latest News of Chicago Industrial Development Plans” – Chicago Commerce, March 10, 1923

“Glass Industry in West Started by Chicago Men” – Chicago Tribune, March 25, 1923

“Chicago, ILL” – The American Flint, May 1923

“Many Changes at Inland Glass Plant” – Ceramic Industry, Nov 1924

“The Stockholders of the Inland Glass Co. . .” – Ceramic Industry, March 1925

“C. J. Nolan” [obit] – Ceramic Industry, December 1926

“Asks Subpoena for Records in Sanitary Quiz” – Chicago Tribune, Feb 8, 1930

“U.S. Dismisses Tax Evasion Indictment Against Chamberlain” – Chicago Tribune, Sept 20, 1935

“Chicago, ILL” [by Emil Nelson] – The American Flint, Vol. 26, 1938

“Glass Blowing” – The American Flint, Vol. 27, Dec 1938

“Inland Glass Works Sold” – Ceramic Bulletin, Vol. 3o, No. 7, 1951

“Club Aluminum Elects; Taylor Heads Board” – Hardware Age, Jan 1952

“How Handles of Resinox Phenolic Plastics are High Styling Inland Carafes” – Machine Design, April 1956

“Work is Very Slow . . . ” – The American Flint, Vol. 51, 1961

God’s Man in the Marketplace: The Story of Herbert J. Taylor, by Paul H., Heidebrecht, 1990

Can anyone verify if any of the round milk glass casseroles with the star pattern around the sides came with a milk glass lid also. I’m seeing mostly clear glass lids on eBay listings and only two milk glass lids. I’m wondering if folks are replacing lids with fire king lids for example?

Thank you 😌

I went to a church rummage sale yesterday paid $3 for the starburst casserole with the lid. Was clueless about this Inland Glass before 6/23/25. Come to think of it I am sure I have the round carafe somewhere in a box in the garage. Love good classical design things.

I was just gifted a Carafe like the first one pictured in this article. Still has the original tag on it. I am so excited. I’m having a hard time, because I like using my ‘antiques’ in everyday to bring history and simplicity back to life!!

I have a triangular casserole with golden crowns on it. I would like to know the name of this pattern and when it was produced.

Where can I find more information about the Inland Glass Company itself? I’ve been unable to find anything. Thanks.