Museum Artifact: Hansen Tacker / Stapler, c. 1940s

Made by: A. L. Hansen MFG Co., 5037 N. Ravenswood Ave., Chicago, IL [Ravenswood]

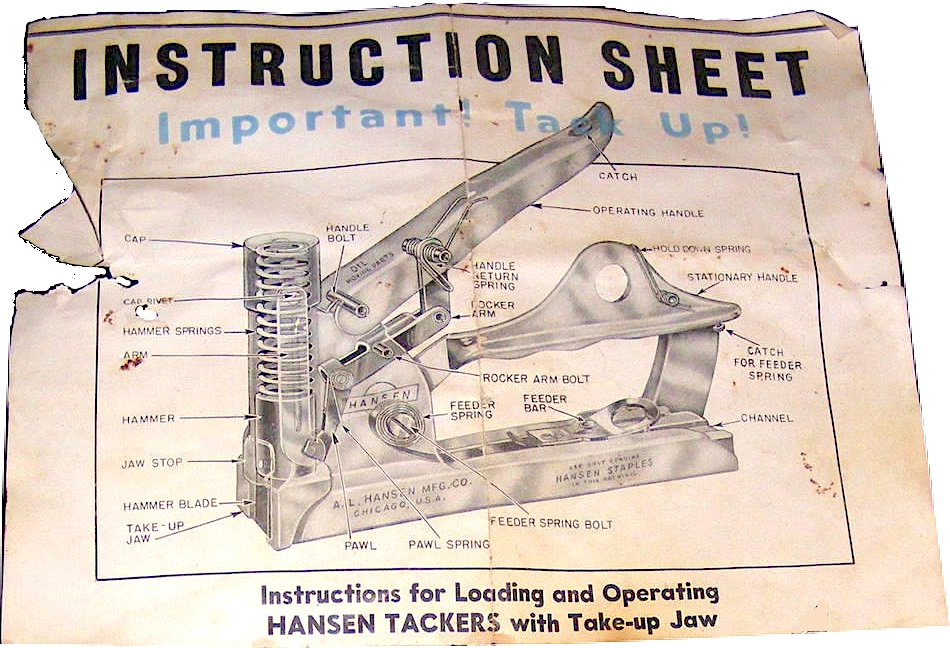

The vintage Hansen Tacker pictured above looks and functions much like the manual staple guns of today—it’s spring-loaded, uses tough wire staples (also made by Hansen), and has an upturned squeeze-trigger handle for one-handed efficiency. It was used for the same sorts of handyman tasks, too: “mounting insulation, tacking screens, ceiling tile, metal lath, displays, tags, signs, etc.”—according to a 1949 ad.

For all intents and purposes, the Hansen Tacker is a staple gun, and with its original patent dating back to 1932, it’s arguably right there among the first of its kind in the world. And yet, on the rare occurrences when this very random topic comes up, most of the credit for the invention of the staple gun goes not to Augie L. Hansen, but to either Albert Juilfs (for a 1948 invention) or Morris Abrams (for the T50 tacker in 1952). Probably by no coincidence, both Juilfs and Abrams were the founders of major corporations that still exist today—Senco Products and Arrow Fastener Co., respectively—so their corporate legacies have likely been carefully curated in the years since.

For all intents and purposes, the Hansen Tacker is a staple gun, and with its original patent dating back to 1932, it’s arguably right there among the first of its kind in the world. And yet, on the rare occurrences when this very random topic comes up, most of the credit for the invention of the staple gun goes not to Augie L. Hansen, but to either Albert Juilfs (for a 1948 invention) or Morris Abrams (for the T50 tacker in 1952). Probably by no coincidence, both Juilfs and Abrams were the founders of major corporations that still exist today—Senco Products and Arrow Fastener Co., respectively—so their corporate legacies have likely been carefully curated in the years since.

But then again, the A. L. Hansen Manufacturing Co. (now known as Hansen International) is still in business, too—approaching its 100th anniversary, no less—so why no love for our boy Augie? Maybe it all just boils down more to a matter of semantics. Is a hand tacker with a spring really a staple gun? And if it’s just a stapler in the traditional sense, is it really even a tacker? Are you still with me? . . . Let’s move on to the company history!

History of the A. L. Hansen MFG Co.

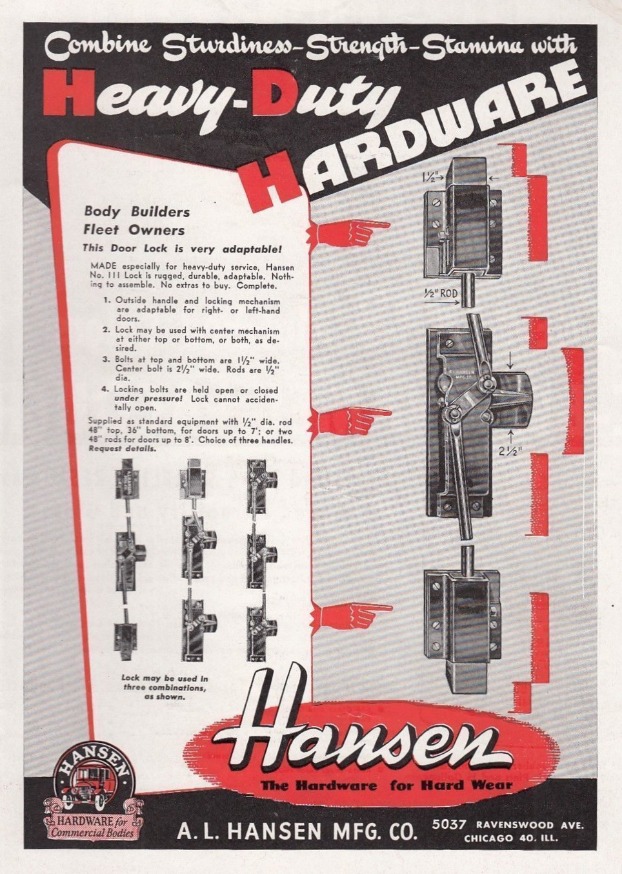

“Hardware for Hard Wear.” That slogan has been part of the Hansen identity for decades, and it certainly suits a business that’s specialized in stuff like metal locks, handles and hinges. The tackers and staplers, while probably the most visible products the company ever made for mainstream commercial use, were never completely vital to its survival. From the beginning, way back in 1920, they were diversified in their offerings.

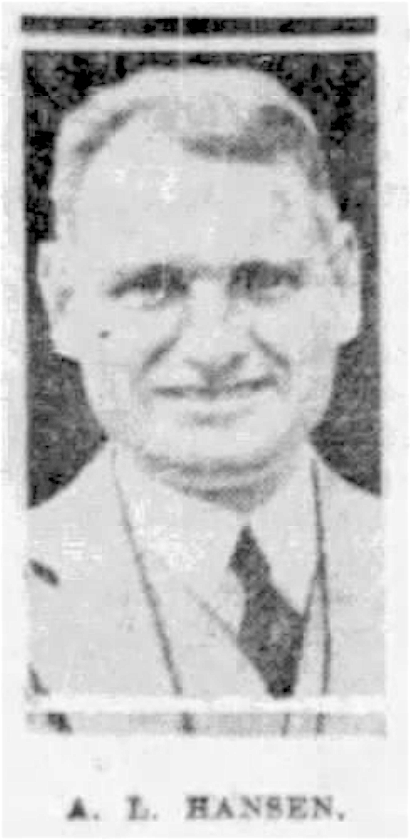

A big reason for this was founder Augie L. Hansen. Like many of the manufacturing entrepreneurs of his era, he was an ambitious immigrant with an inexhaustible motor. In terms of pure creative vision and versatility of skills, however, he was probably even a few steps ahead of his cleverest rivals.

A big reason for this was founder Augie L. Hansen. Like many of the manufacturing entrepreneurs of his era, he was an ambitious immigrant with an inexhaustible motor. In terms of pure creative vision and versatility of skills, however, he was probably even a few steps ahead of his cleverest rivals.

Born in Copenhagen, Denmark, in 1879, Hansen came to Chicago with his family at the age of eight, and his boundless curiosity and passion for tinkering turned him into something of a child prodigy. He collected his first patent at age 11, and by 15, was gainfully employed at the timekeepers office of the Western Electric Company. When his employers saw how eager he was to stay on after-hours to work on his own inventions, they did the smart thing and moved him to the machine shop as a first class mechanic.

In his 20s, Hansen expanded his trade knowledge at factories in New York and Connecticut, racking up a laundry list of new patents, then returned to Chicago for a superintendent job at the Acorn Brass Manufacturing Company and an eventual chief engineer position with the Justrite Manufacturing Co.

There wasn’t necessarily a pattern to the products Hansen invented and developed. He just had that unteachable knack for problem-solving and envisioning the machinations of that which did not yet exist. Among his creations: the “DryLite” carbide lamp (an important development for the mining industry), tetra-chloride fire extinguisher, foot pedal trash cans (!), and the Wrigley revolving gum display stand, just to name a few. His total portfolio of patents would eventually reach more than 200.

The Hansen Tacker in our museum collection was another Augie original, although he technically started from a template developed by one of his own employees, Hugo J. Baur.

The Hansen Tacker in our museum collection was another Augie original, although he technically started from a template developed by one of his own employees, Hugo J. Baur.

In 1932, Baur had applied for a patent, under the A.L. Hansen MFG. Co. banner, for an “improved stapling machine, in the nature of a small hand tool, which is designed to be both held and operated with the same hand.” The patent was approved in 1934, the same year Popular Science magazine ran a blurb about the rise of new “staple hammer” devices.

“A new rapid-fire staple hammer looks and works like an automatic pistol,” the article read. “With the grip of the device held in one hand, the trigger is pressed to drive the staple into place. The pressure releases a spring-loaded plunger in the device which drives the staple home at one blow. The tacks come in continuous clips of fifty.”

Taking charge of the project, Augie Hansen spent much of the next decade repeatedly refining and improving the design, usually with the goal of stopping the one problem that still plagues these devices to this day: staple jams.

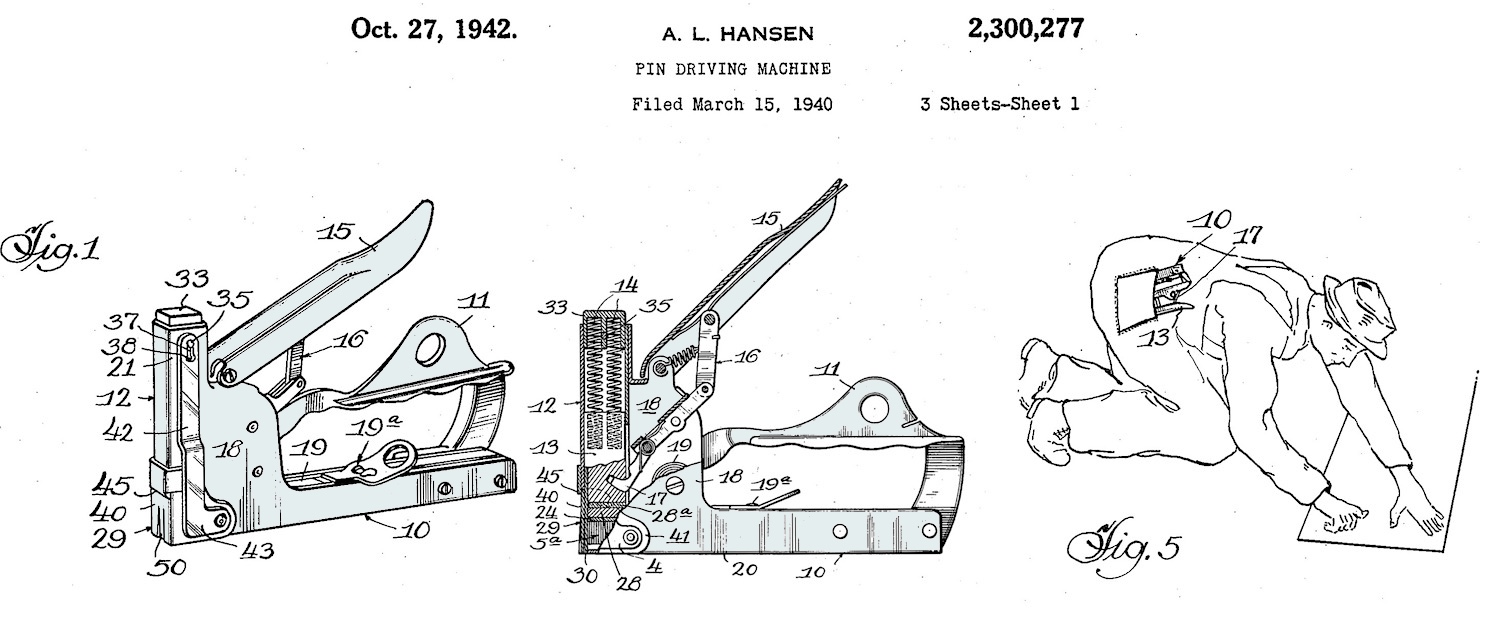

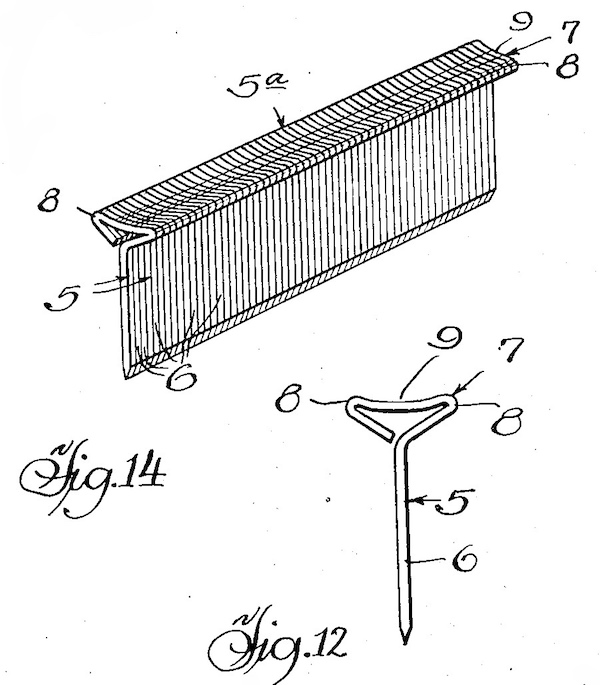

[Augie Hansen’s “Pin Driving Machine” patent was a slightly new take on his “Stapling and Tacking Machine,” and was approved for a U.S. patent in 1942]

[Augie Hansen’s “Pin Driving Machine” patent was a slightly new take on his “Stapling and Tacking Machine,” and was approved for a U.S. patent in 1942]

The vast majority of Hansen Tackers manufactured from the 1930s onward were designed to be loaded with traditional U-shaped wire staples, which were only considered “tack points” in the loosest definition of the word.

We have a 5,000-count box of Hansen’s own Blue-Line tack points in our museum collection, pictured below, likely dating from the 1940s. As you can see, they don’t look all that different from the style you’d use in a school stapler, but they were built for considerably more demanding jobs. Available in dozens of different sizes, they were also “specially designed” for use with Hansen Tackers, as noted by the warning language etched into the metal of each tacker: “For Best Results, Use Hansen Staples.”

[A vintage 5,000-count box of Hansen “Blue-Line” Tack Points, also part of the museum collection]

[A vintage 5,000-count box of Hansen “Blue-Line” Tack Points, also part of the museum collection]

Augie Hansen was never completely satisfied with the performance of traditional staples, however—even his own Blue-Line series. The legs could easily pinch either during manufacturing or when being inserted into the magazine of the tacker, and this routinely led to the aforementioned clogs, followed by frustrated customers cursing the Hansen name.

And so, by 1940, Hansen made some adaptations that inspired a new patent application for both an updated machine and an original style of staple/tack/pin—with a “single shank and a novel form of collapsible head, especially adapted for use with a pin-driving machine.”

“Among the advantages of my novel form of pin-driving machine as compared to a staple-driving machine of the kind now so commonly used,” Hansen explained, “are the much greater number of uses to which a pin-or tack fastening device can be applied and adapted, and the fact that the machine itself can be made much lighter and will operate much easier than staple-driving machines of comparable effectiveness. A single-shank pin requires only about one-half the power that is needed to drive a double-shank staple of the same size. In practice this means that the driving springs need only have a fraction of the strength heretofore employed in staple-driving machines, and that the machine requires correspondingly less manual power for its operation.”

“Among the advantages of my novel form of pin-driving machine as compared to a staple-driving machine of the kind now so commonly used,” Hansen explained, “are the much greater number of uses to which a pin-or tack fastening device can be applied and adapted, and the fact that the machine itself can be made much lighter and will operate much easier than staple-driving machines of comparable effectiveness. A single-shank pin requires only about one-half the power that is needed to drive a double-shank staple of the same size. In practice this means that the driving springs need only have a fraction of the strength heretofore employed in staple-driving machines, and that the machine requires correspondingly less manual power for its operation.”

The single-shank pin became a new staple (pun intended) of Hansen’s arsenal, but it never overtook the old U-shaped style for most jobs. This was hardly a defeat for its inventor, however. After all, Augie Hansen didn’t wind up with 200 patents by mastering every design on the first try. His drive to continuously improve and try new methods and means—fruitful or not—was what ultimately set him apart.

[1949 Hansen advertisement]

[1949 Hansen advertisement]

From Idea Man to Business Leader

The evolution of the Hansen Tacker is pretty emblematic of Augie Hansen’s consistent dedication to his original passion—mechanical engineering. During the Great Depression, he was approaching retirement age, and he had two sons, William and John, ready to run the business. The opportunity was there to take a step back or simply stick with the basics of what had worked in the past—to keep risks to a minimum. But such an approach wasn’t in Hansen’s nature. He was too fond of a challenge.

Back during the 1910s, even before he had his own business, Hansen’s reputation had made him highly sought after as a free agent consultant, helping manufacturers fine-tune their ideas, and business owners like William Wrigley better market their products. When World War I broke out,

Back during the 1910s, even before he had his own business, Hansen’s reputation had made him highly sought after as a free agent consultant, helping manufacturers fine-tune their ideas, and business owners like William Wrigley better market their products. When World War I broke out,

Thomas Edison had personally called on Augie to work with him at the War Department, recognizing an innovative young buck when he saw one. Hansen, of course, happily obliged.

When the war ended, there were no shortage of positions offered to Hansen at other companies, but he chose the riskier route again, purchasing a two-story factory at the northeast corner of West Ravenswood and Winnemac Avenue for $27,500 (about $330,000 in today’s money), and launching the Augie L. Hansen Manufacturing Company. Hansen’s original business partner and company treasurer was a patent attorney named James R. Offield, who also happened to be William Wrigley’s son-in-law.

[This building at W. Ravenswood and Winnemac Ave. was home to the A. L. Hansen MFG Co. from 1920 to 1966. It was expanded from its original two-story size to three stories in 1929.]

[This building at W. Ravenswood and Winnemac Ave. was home to the A. L. Hansen MFG Co. from 1920 to 1966. It was expanded from its original two-story size to three stories in 1929.]

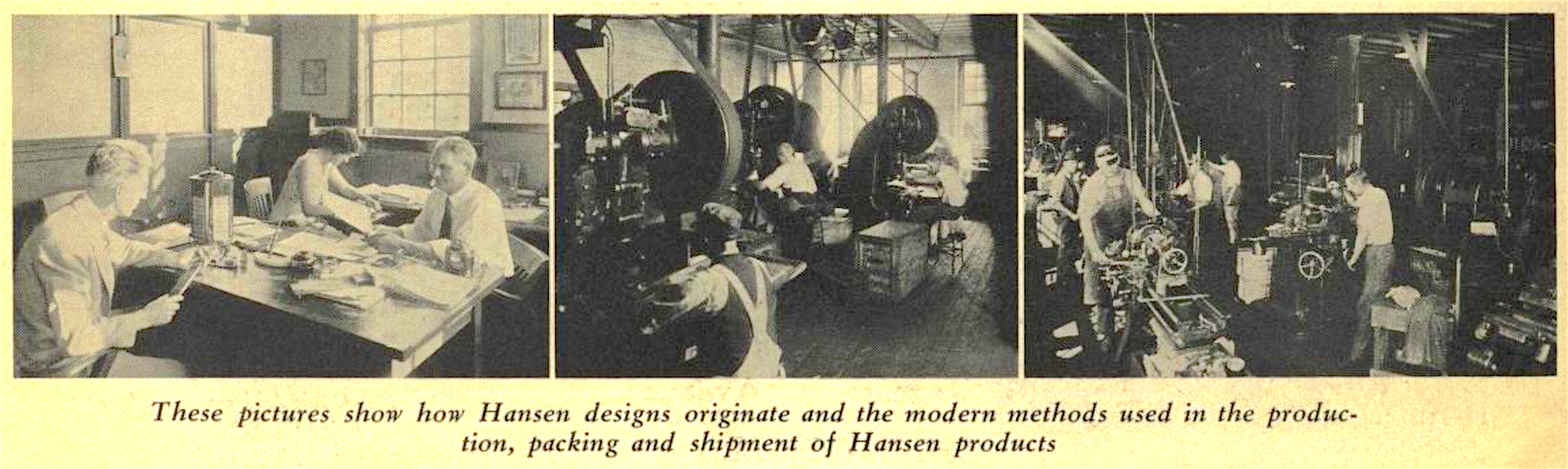

It’s not clear if Mr. Wrigley assisted Hansen and Offield with an influx of chewing gum cash, but through some means or another, the fledgling company was able to bring 100 workers into its employ, specializing in “the manufacture and merchandising of patented metal specialties,” according to a Tribune report on August 1, 1920. That work would include an increasing focus on automotive parts in the years that followed, particularly specialty components for a new truck-based shipping industry emerging on America’s developing highway system.

Reflecting its owner’s knack for perfecting the right hardware for any niche need, the Ravenswood factory produced everything from door hinges and adjustable corner braces to locking mechanisms for windows, refrigerators, and early truck cabs. “Hansen Hardware is noted for its simplicity of design, dependable operation and exceptional durability,” the company’s 1932 catalog declared. “If it’s Hansen, it’s modern!”

[Above: Inside the Ravenswood factory, 1932. Below: An early Hansen classified ad seeking assemblers and solderers, 1923]

[Above: Inside the Ravenswood factory, 1932. Below: An early Hansen classified ad seeking assemblers and solderers, 1923]

When the Great Depression hit, Hansen stayed above water largely by diving into projects like the tacker and other new devices outside the established wheelhouse. The company’s success in those efforts got Augie Hansen his own profile feature in the Tribune in 1932, in which he was heralded as one of the local business leaders defeating the economic slump of the period “by inventing new business.”

“Others have pointed to the fact that we have been pulled out of slumps, once by the invention of the automobile and again by the radio,” Hansen told the Tribune’s Oney Fred Sweet. “Inventions—and I believe it will be simple ones—will come to our aid again. We may not all be inventors, but it behooves us to think along new lines, forget precedents that keep us inert, and study demands. Rather than complain about being leaderless, it is up to us all to be leaders in the best way we know how.”

Did you expect a Danish stapler inventor from the 1930s to inspire the daylights out of you? Well I guess you should have!

Did you expect a Danish stapler inventor from the 1930s to inspire the daylights out of you? Well I guess you should have!

The article goes on to state that Hansen—despite his reputation as a patent collector—had a distaste for the cliché of the eccentric, singularly focused inventor. Or, as he put it, “the dreamy mechanic toiling on a patent which he hopes will make him rich overnight.”

“The depression of 1893 left a lasting impression on me,” Hansen explained. “I was a lad at the time, but in the midst of our prosperity [in the 1920s] I was aware that such a period might again occur. When I saw the present slump coming, I decided it was time to be all the more on my toes. Surely it wasn’t a time to lay down, but a time to think of something new. Don’t think we have not had disappointments. Who hasn’t? But there will always be a demand for things that are better than they have been before.”

Augie seemed to put his money where his mouth was three years later, when the A.L. Hansen MFG Co. became the first major Chicago business to independently increase worker wages after the end of the National Recovery Act in 1935. All employees at the Ravenswood factory enjoyed a 5% pay spike, as a 56 year-old Hansen explained to reporters, “Now is the time for manufacturers to demonstrate what they can do with government interference removed.”

Augie’s sons William Hansen and John Hansen eventually took over control of the day-to-day operations of the family business after World War II, as the trucking accessory department became the major money maker.

Augie’s sons William Hansen and John Hansen eventually took over control of the day-to-day operations of the family business after World War II, as the trucking accessory department became the major money maker.

After Augie’s death in 1965 at the age of 86, the Ravenswood chapter closed with him. Ground was broken on a new factory in suburban Gurnee, Illinois, and the company was relocated there by 1967.

In 1974, the A.L. Hansen Manufacturing Company became a subsidiary of Illinois Central Industries (aka I.C. Industries and later to become Whitman Corp), a former railroad company that was now a major auto parts maker, as well as a giant soft drink bottling and heating/cooling juggernaut.

As of 2015, A.L. Hansen was still in operation, producing its usual batches of locks, bolts, handles, hinges and latches out of a facility in Waukegan, Illinois. Augie’s grandsons Bill and Justin Hansen were carrying on the tradition as the third generation leaders of the old family business.

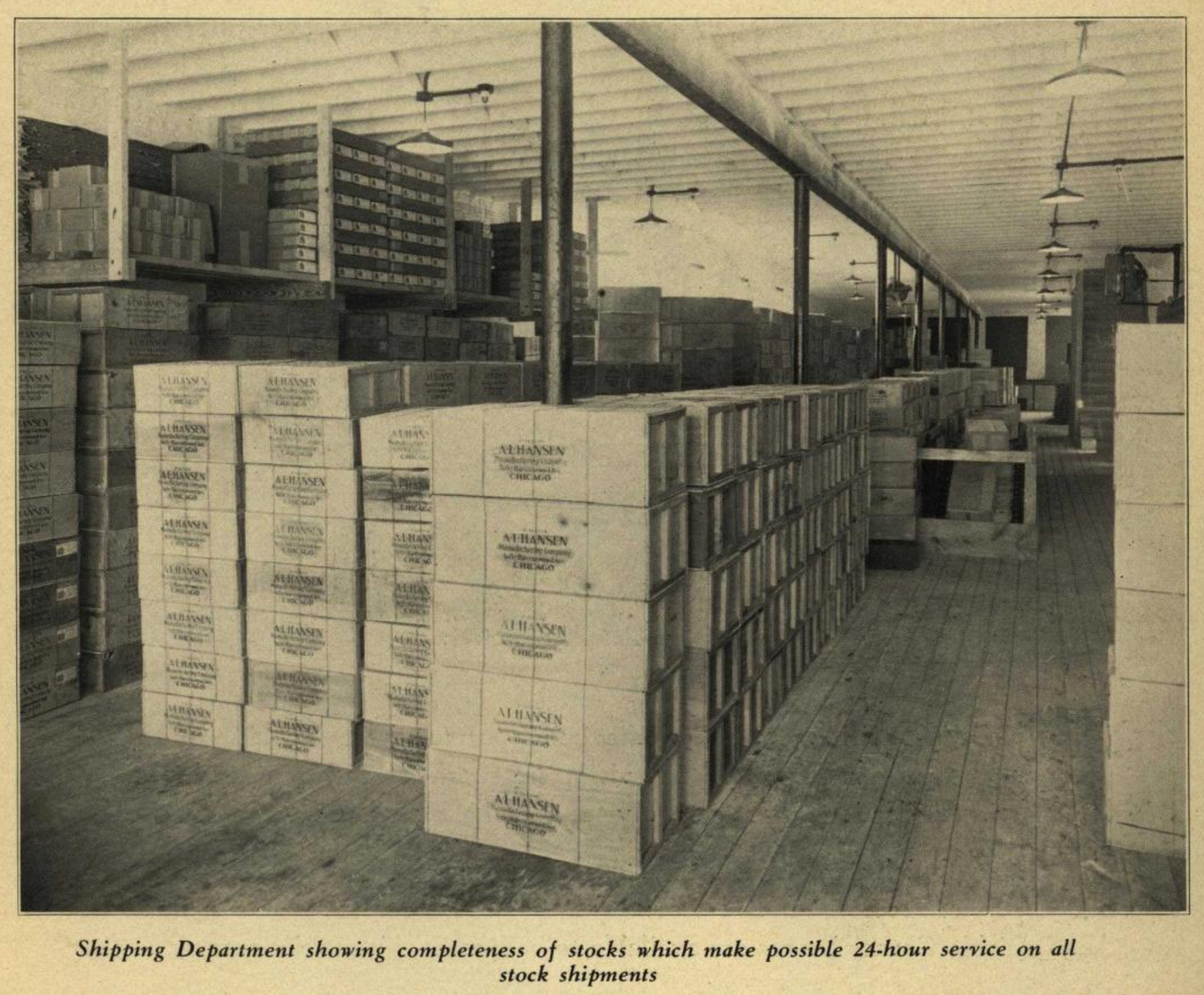

[Old shipping department inside the Ravenswood plant, 1932]

[Old shipping department inside the Ravenswood plant, 1932]

Sources:

“Augie L. Hansen” – Manufacturing and Wholesale Industries of Chicago, 1918

“Defeats Slump By Inventing New Business” – Chicago Tribune, Jan 3, 1932

“Hammer for Staples is Like Pistol” – Popular Science, November 1934

“A L Hansen MFG Increases Wages” – The Times (Hammond, Indiana), June 14, 1935

“Ravenswood District to Get Specialties Plant” – Chicago Tribune, Aug 1, 1920

“Let Contracts for Annex to Hansen MFG Co. Plant” – Chicago Tribune, June 2, 1929

“Augie Hansen, Industrialist, Dies at Age 86” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 6, 1965

We are looking for number 33 and 34 staples for the No 3 Hansen heavy duty stapler.

Where can I get A.J.Hansen Kling-Tite #3 staples ?

I have one in good condition

How much is it worth ?

I have a box of Hanson staples No 34 – 1/4″ tack point. The box looks very similar to the one pictured on this web site with one distinct difference that I can see. My box says “genuine” and not “blue-line” after the number 5000. The address on the box is the 5037 Ravenswood Chicago address. Can you tell me what the difference may be between the 2 staples. Thank you.

I was given one of these staplers and am looking for staples. It says on stapler to use #3 and #4 staples. Are these still available?

My dad used a #3 gun when he worked for Kraft Foods. I have several of them. I have misplaced the staples.Where can I buy the correct staples? Will Bostich or Arrow brands work?

Does anybody know where I can find instructions on how to load this tracker. TYIA

Hi I inherited a Hansen staple gun and it has 363569 on it and states only use Hansen staples? Where can I get some?

Thanks,

Beth Rist

337-309-5583

I just got home from a garage sale (7/17/21) and got one of these “Hansen Tackers” out of the $1 box. It seems to be workable, but I too need staples. It says, ” Use only Genuine Hansen Staples No 43 & 44″. The serial or model number(?) on one side is 440364, with patents from Oct. 30, 1934, July 2, 1940 & July 9,1940 (Other Pats Pending, lol).

Fred I have had the No.4 staple gun for 20years and a box of Arrow staples No.605 wide crown heavy duty 5/16” (8mm) which work great and am looking for another box, which I think I found on amazon. If you find this description it should be correct, I am ordering some for myself now. can’t find at Home Depot.

I have one of these staple guns. Can I still get staples?

Have a 1940 patn’d Tacker gun

Any other staple brand/size work?

Cannot get normal staples to work

Where can I buy #2 staples for vintage staple gun

Can you find modern staples for this staple gun today?