Museum Artifact: Tintype Photo Medallion of Woman, c. 1910s

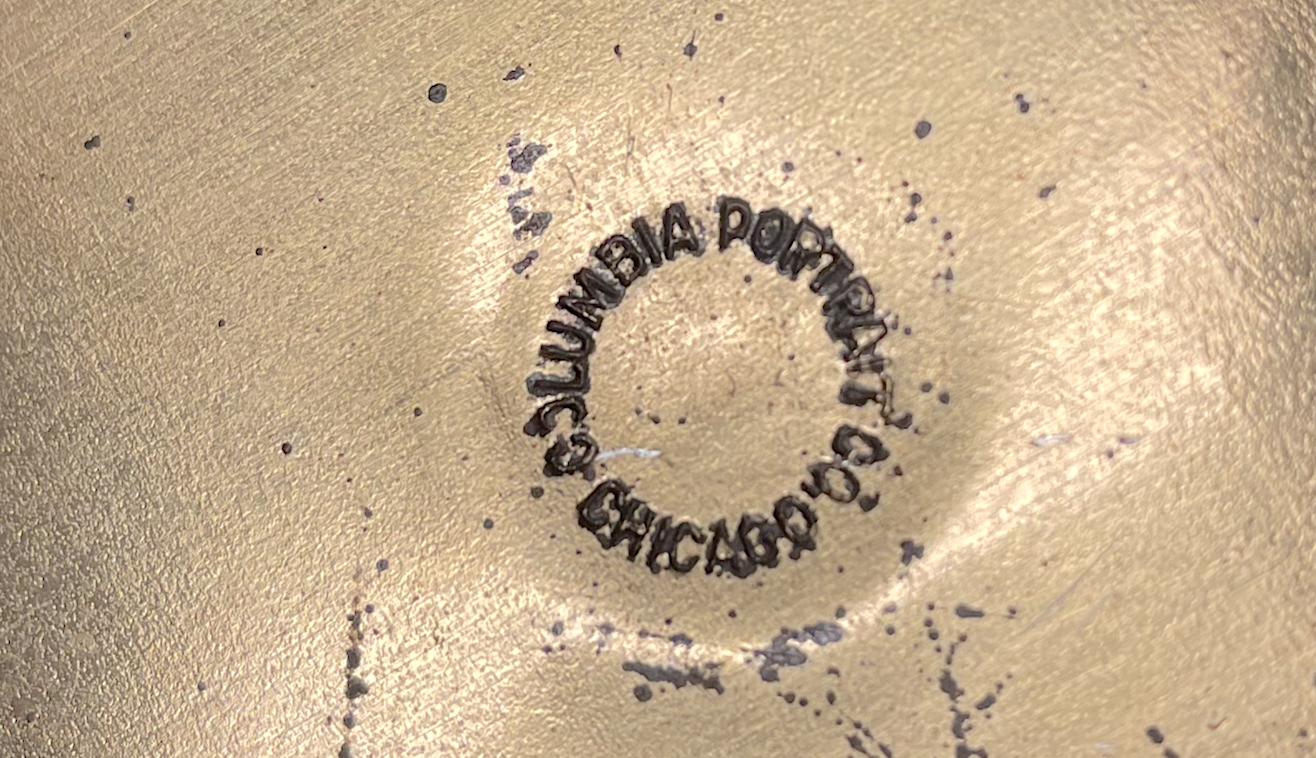

Made By: Columbia Medallion Studios / Columbia Portrait Co., 6616-6620 South Cottage Grove Ave., Chicago, IL [Woodlawn]

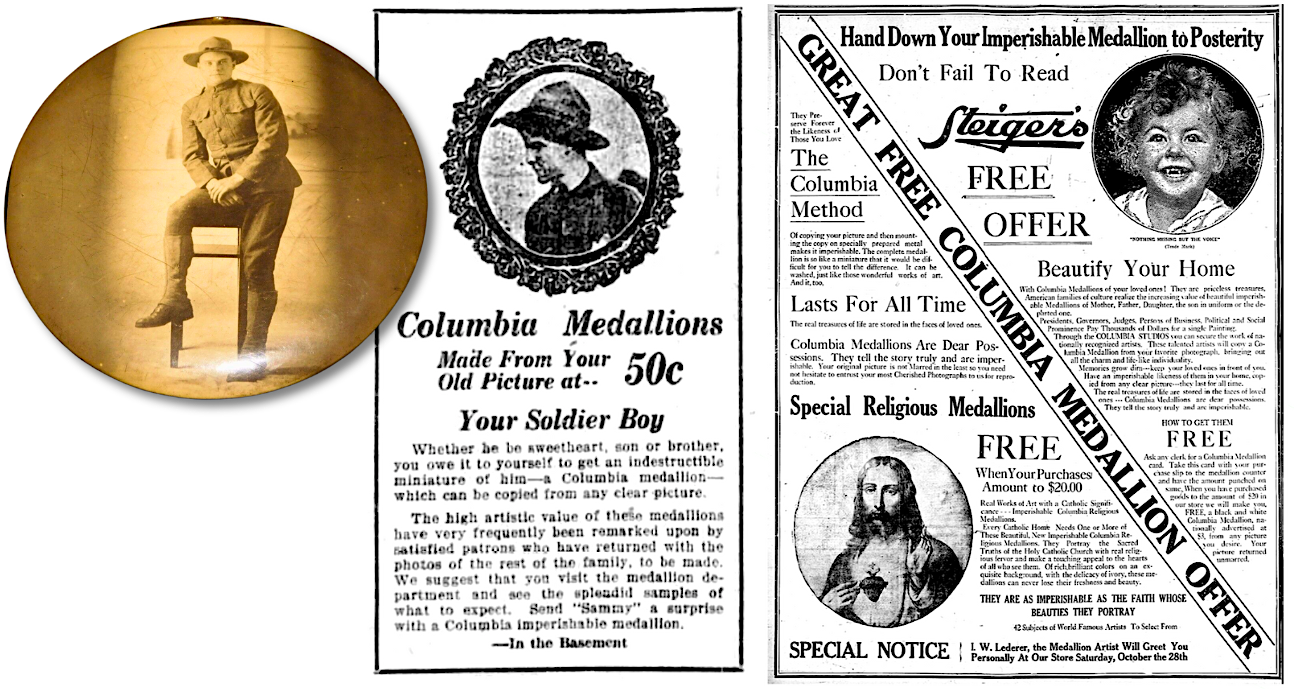

“These beautiful photo medallions are the most artistic portraits ever produced. They are mounted on non-corrosive metal specially prepared. The portrait is burnt in, same as on porcelain, and covered with heavy celluloid, making the picture strong and imperishable, preserving forever the features of those you love.” –Columbia Medallion Studios advertisement, 1913

More than 100 years ago, a young woman posed for a professional portrait in a photography studio, and in a flash of light, the camera captured something about her . . . maybe it’s the optimistic eyes of a rebellious suffragette, or the subtle smirk brought on by the comedic stylings of her photographer. In any case, somebody thought enough of the resulting image that they put the original paper photo in an envelope and mailed it to the Chicago offices of the Columbia Medallion Studios, where it was then expertly transferred onto a 6×6″ metal button; given a glazed sepia-tone finish; and finally secured into a stylish, rose gold frame. The young girl had been effectively frozen in time, her essence forever preserved.

More than 100 years ago, a young woman posed for a professional portrait in a photography studio, and in a flash of light, the camera captured something about her . . . maybe it’s the optimistic eyes of a rebellious suffragette, or the subtle smirk brought on by the comedic stylings of her photographer. In any case, somebody thought enough of the resulting image that they put the original paper photo in an envelope and mailed it to the Chicago offices of the Columbia Medallion Studios, where it was then expertly transferred onto a 6×6″ metal button; given a glazed sepia-tone finish; and finally secured into a stylish, rose gold frame. The young girl had been effectively frozen in time, her essence forever preserved.

The only problem is . . . we have no idea who she was.

Therein lies the somewhat ironic legacy of the Columbia Medallion Studios, aka the Columbia Portrait Company, a business that often promoted its services with the existentially threatening tagline: “Don’t Let Memories Grow Dim!” It was a message that resonated with an early 20th century audience that now saw photography, for the first time, as an accessible means of cataloging their lives and the people in them. Much like the businesses that started digitizing old VHS home movies in the 2000s, Columbia gave its customers a way to more confidently safeguard their fragile visual keepsakes. Rather than a piece of paper that could fade, crinkle, or fall through the proverbial cracks, the metal transfer was impervious even to fingerprint smudges; it could be cleaned with water, thrown like a frisbee . . . you name it.

A century of subsequent evidence pretty well supports the quality of Columbia’s products, as one can still find thousands of these photo “medallions” strewn across eBay and the dustier corners of antique shops; most of them in excellent condition, still displaying their subjects as vividly as they did when they were first commissioned. Unfortunately, though, the vast majority of them have also been robbed of their historical significance and emotional resonance, as Columbia’s curious disinterest in including the names or dates associated with the images have turned them collectively into traveling tributes to the anonymous. Each medallion was purchased to keep someone’s memory alive, but as it turned out, the memory itself was always dependent on the customer being around to remember it.

The same rule somewhat applies to the story of the Columbia Medallion Studios itself. While it was supposedly the world’s largest purveyor of photo medallions for the better part of three decades, the company did little to ensure its own lasting relevance, as–like a faded photo–it, too, drifted into obscurity by the 1930s. We’ve compiled what we do know about the business into a short history, which you can find right beneath this full-color 1919 Columbia advertisement.

[Columbia Medallion Studios magazine ad from 1919]

History of the Columbia Medallion Studios, Part I: Nothing Missing But the Voice

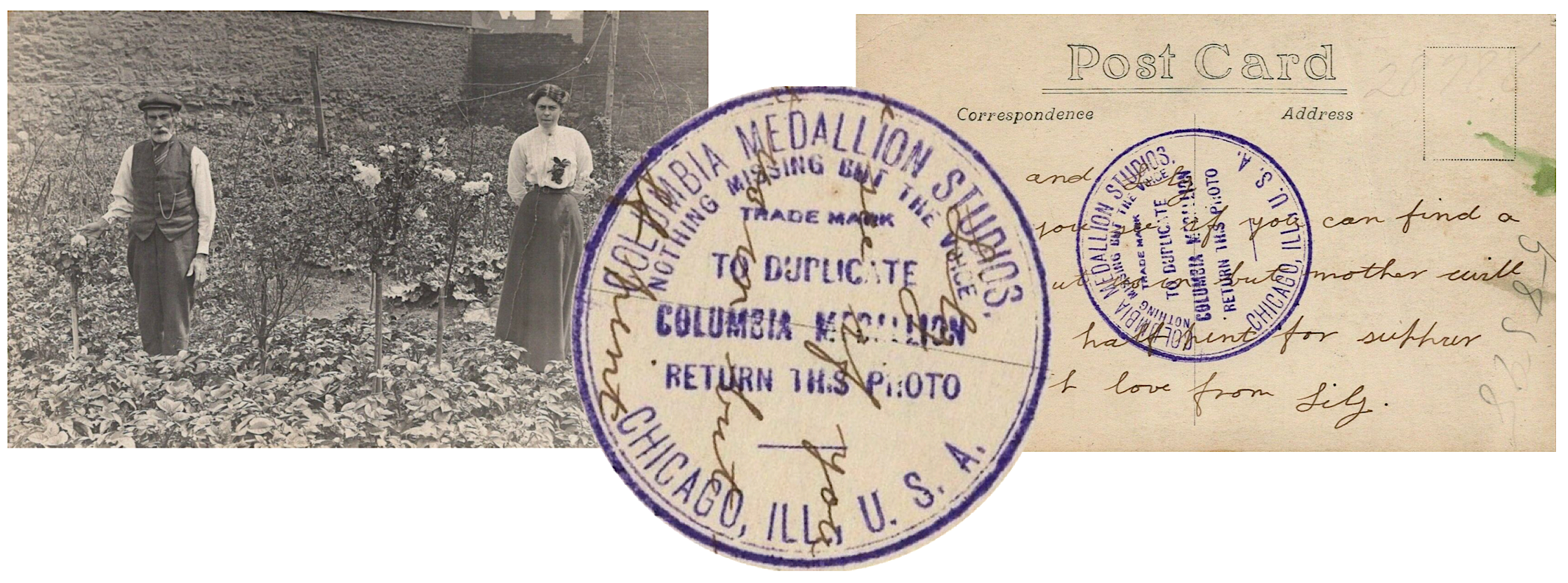

Unlike the majority of businesses profiled in the Made In Chicago Museum, the Columbia Medallion Studios offered both a product and a service. While the company did produce some pre-designed medallions with images from famous artworks or biblical scenes, most of its business flowed through the mailing department, where a steady flow of random family photos was always being filed and processed. Customers purchasing a water-color medallion would be required to note the eye and hair color of the person in their portrait, but aside from that, instructions and standards were minimal, and names, of course, were irrelevant. Hence, we have the example of another medallion from our collection: “unknown child in a garden.” Before we judge this oversight of identity too harshly, however, do stop and consider whether you’ve properly tagged yourself in every random jpeg floating through cyberspace. If not, future historical researchers may see you in a similar light to the medallion folks; facial recognition software aside.

Anyway, getting back to the literal business end of things, we can track the origins of the medallion enterprise back to 1888, when it was founded as the Columbia Portrait Company; a name it retained in an official capacity even after the “Columbia Medallion Studios” became more of its commercial identity during World War I.

Back in its earliest days, Columbia’s reputation wasn’t exactly stellar. In the famous World’s Fair summer of 1893, for example, company president “Frank Horn” was revealed to be a swindling con man named John Horner, and was forced to cough up $75 (a somewhat substantial sum for the time) to victims of his admitted crimes, which apparently included selling forgeries of other people’s artwork. Somehow or another the business survived that debacle, and by the turn of the century, a new president, H. Irving Goodrich, had semi-legitimized the operation, renting out an office above the Haymarket Theater on West Madison Street.

Then, more bad press. In the fall of 1904, a chemical explosion in the Columbia Portrait Company lab started a fire that forced a panicked audience to evacuate the theater below. Six firemen were hurt. And yet . . . the medallion business soldiered on yet again.

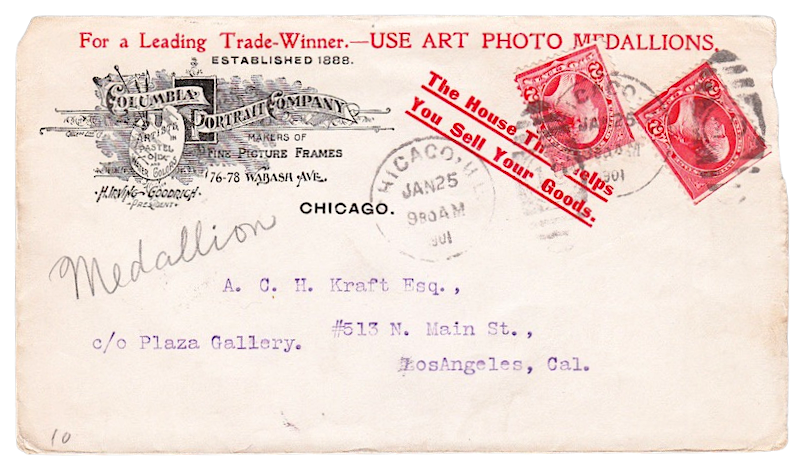

[Early letterhead for the Columbia Portrait Company, “Makers of Fine Picture Frames,” 1901]

[Early letterhead for the Columbia Portrait Company, “Makers of Fine Picture Frames,” 1901]

The company’s home office moved several times as its in-house workforce grew from less than 10 to more than 30 (they also had a small army of salesmen). Some confirmed addresses over the years include:

⇒ 76 Wabash Ave (c. 1900-1903)

⇒ 76 Wabash Ave (c. 1900-1903)

⇒ 121 / 716 W. Madison, aka Haymarket Theater Building (c. 1904-1919)

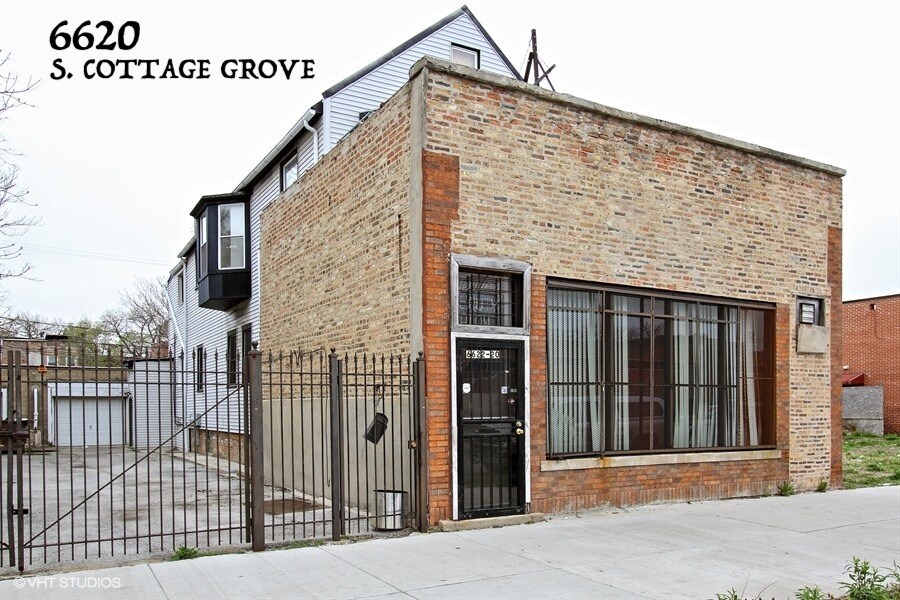

⇒ 6620 Cottage Grove Ave (1920s)

⇒ 1601 S. Michigan (1930s)

In each of these locations, the making of the medallions themselves was just one small aspect of the business, and probably the cheapest (they’re basically just oversized buttons without the pinback). Columbia made most of its profits from getting customers to upgrade to fancy frames, and likely also through special arrangements with department stores, which offered “free” medallions as shopper enticements.

Again, in the early 1900s, Columbia was trying to appeal to the first generation of Americans that had the capability of looking back nostalgically at actual photographs of their parents and grandparents . . . or of carrying around a brand new photo of their soulmate. And because these images were fragile and precious by nature, the sales pitch of seeing them transferred to a glossy bubble for posterity was not a difficult case to make.

Columbia used the slogan “Nothing Missing But the Voice,” and their ads proclaimed: “How quickly a photograph perishes. Columbia Medallions can, however, be treasured for ages. They are made from any photograph, copied on non-corrosive metal and the surface glazed. . . . You need have no hesitation in sending your most precious pictures because they will he returned in iust as good condition as we received them.”

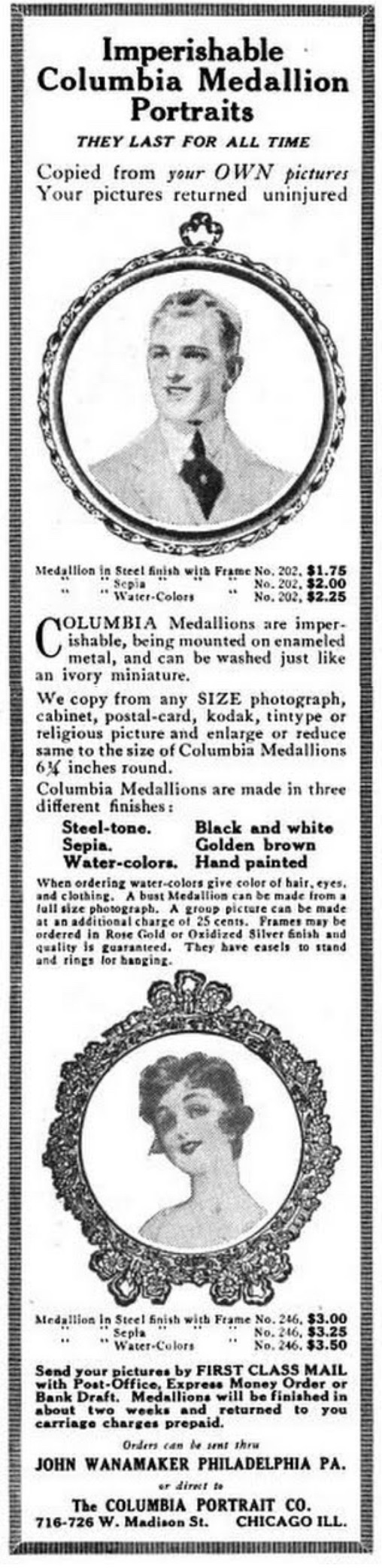

By 1917, Columbia offered three main custom finishes: Steel-Tone (black and white), Sepia (golden brown), and a hand-painted option in watercolors, where the eye and hair color could be added to a black and white image. A painted medallion, with a frame, would run you $3.50, which sounds like a sweet deal. After inflation, though, that’s roughly $80 in 2023 money. The cheapest option—steel-tone with no frame—was about half that price.

The company seemed to hit a peak in the years during and immediately after World War I. Advertisements in 1919 claimed that “more than two million Columbia Medallions” were in homes across the U.S. and Canada, and company president Izri W. Lederer seized on the obvious connection between memory preservation and wartime.

“Husbands, sons, brothers and friends who have fought ‘over there’ or who have done their part at home, deserve to be thus remembered by you and posterity,” one ad read.

[Above: Example of a postcard sent to Columbia Medallion Studios for duplication onto a medallion, later returned to the owner. Below: Medallion of a WWI soldier, a 1918 advertisement (left) and 1922 ad (right)]

II. Lederer Leads the Way

Izri Lederer (1880-1951) certainly appears to have been an interesting fellow. As head of the Columbia Medallion Studios, he was sometimes mischaracterized by lazy journalists as a “studio head,” as if he were competing directly with Louis B. Mayer and Jack Warner (Columbia Medallion had no connection, we should mention, to Columbia Pictures, the film studio that came along in the 1930s). Tellingly, Izri rarely corrected the misinformed.

It’s hard to say how much direct involvement Lederer actually had with the medallion-making process in Chicago, or how much artistic talent or technical skill he brought to the table. The man was certainly a good salesman, though, as evidenced by his dedication to the business (he made regular appearances at special medallion sales events in department stores across the continent) and his healthy bank accounts.

Living out of the swanky Edgewater Beach Hotel, Lederer poured his medallion earnings into real estate and other business investments, all while playing himself off with the media as some sort of Bohemian hepcat artiste.

“People of melancholy temperament very rarely have clear blue eyes,” Lederer told a newspaper man while on a visit to Los Angeles in 1919. The brief interview, which found syndication in regional papers across the country (many of them again mistaking Lederer for a “movie studio head”) showcased a particular talent Izri supposedly had for sizing up a photographic subject—pretty L.A. girls, specifically.

“I.W. Lederer of the Columbia Medallion Studios of Chicago,” the article began, “here analyzing the iris of all the city sirens’ eyes, says that by one look into the limpid depths of violet-grey eyes, sea-green eyes, glittering black eyes and hazel eyes, he can tell the owner’s character.”

“Violet blue eyes are loving and ardent,” Lederer proclaimed, “but impetuous and do not show a high order of intellect. A glittering black eye expresses meagre intelligence, but often physical courage. Velvety brown eyes show intense feeling and are not often to be trusted.

“. . . Gray eyes turning green in anger or excitement are signs of choleric temperament. Gray eyes are those of intellect and a well-balanced character. When the upper lid covers half or more of the pupil the indications are of a cool, deliberate character.”

We don’t know exactly what Izri Lederer’s eyeballs looked like, but a safe guess would be that they suggested the temperament of an obnoxious rich man who likes to babble about pseudoscience.

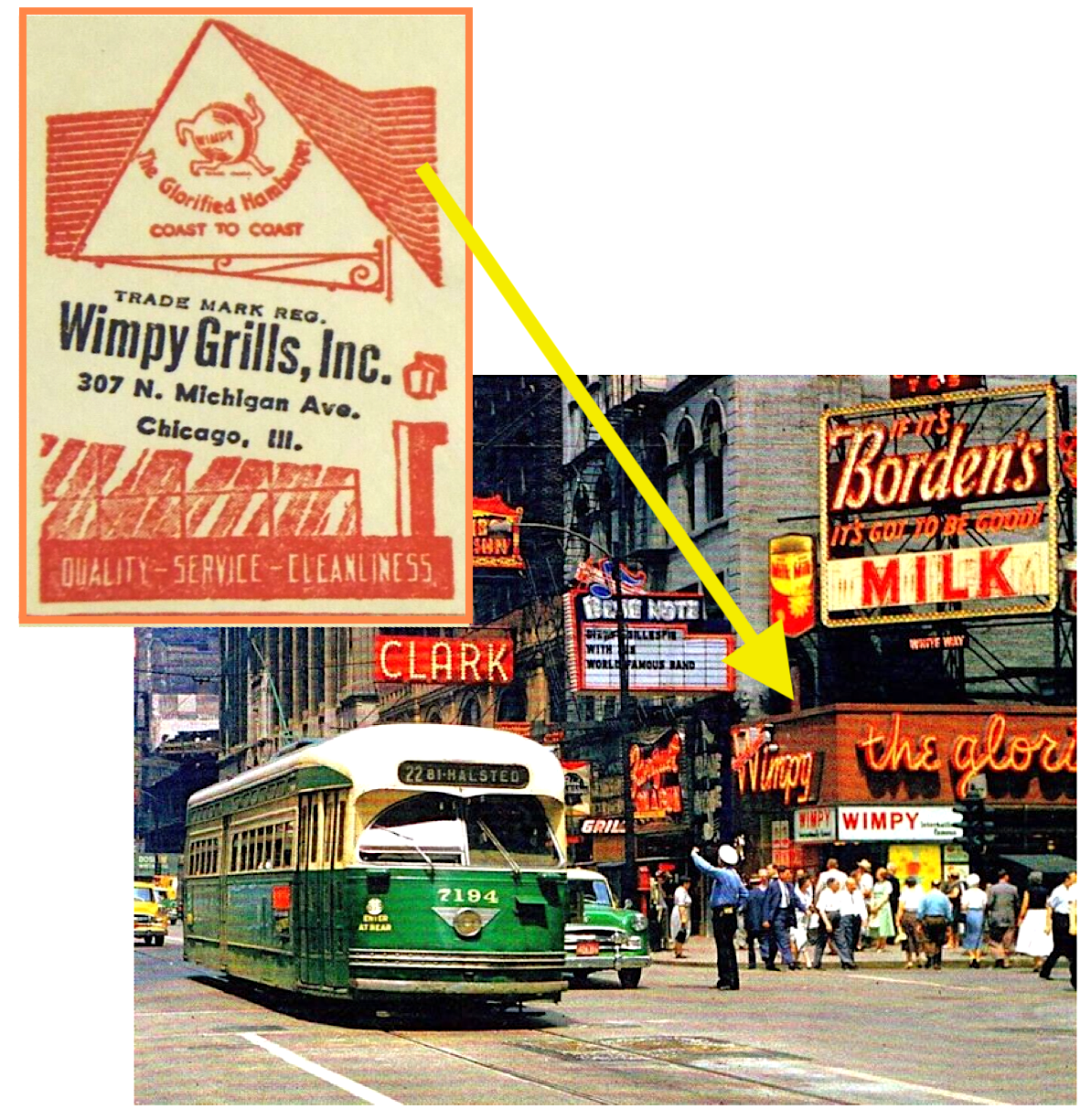

In any case, by the time the next big war rolled around, things had changed pretty dramatically for the photo medallion industry, such as it was. The Depression had cut down demand, rationing during World War II likely further tripped up production, and Izri Lederer was now pre-occupied with a new enterprise as co-founder and vice president of one of America’s first fast food burger chains, Wimpy Grills.

Maybe even more importantly, better photographic technology now existed, giving people more confidence about the quality and longevity of the pictures they took. Plus, propping up a shiny photo medallion on a decorative easel just seemed like more of a Roaring ‘20s kind of thing to do anyway. What once brought amazement was now, ultimately, old fashioned and outdated.

Maybe even more importantly, better photographic technology now existed, giving people more confidence about the quality and longevity of the pictures they took. Plus, propping up a shiny photo medallion on a decorative easel just seemed like more of a Roaring ‘20s kind of thing to do anyway. What once brought amazement was now, ultimately, old fashioned and outdated.

The Columbia Portrait Co. and Columbia Medallion Studios faded away around this point in history, leaving no trace of their records, and thus no paper trail for identifying the thousands of people they committed to immortality. If you recognize any of the faces included on this page, please let us know. Don’t let those memories grow dim!

[During the 1920s, the Columbia Medallion headquarters was listed at 6620 S. Cottage Grove Ave, which looked like this as of 2020. Presumably, the business occupied more real estate than this, meaning portions of the original building were later demolished, or the building was mainly for receiving orders, rather than production.]

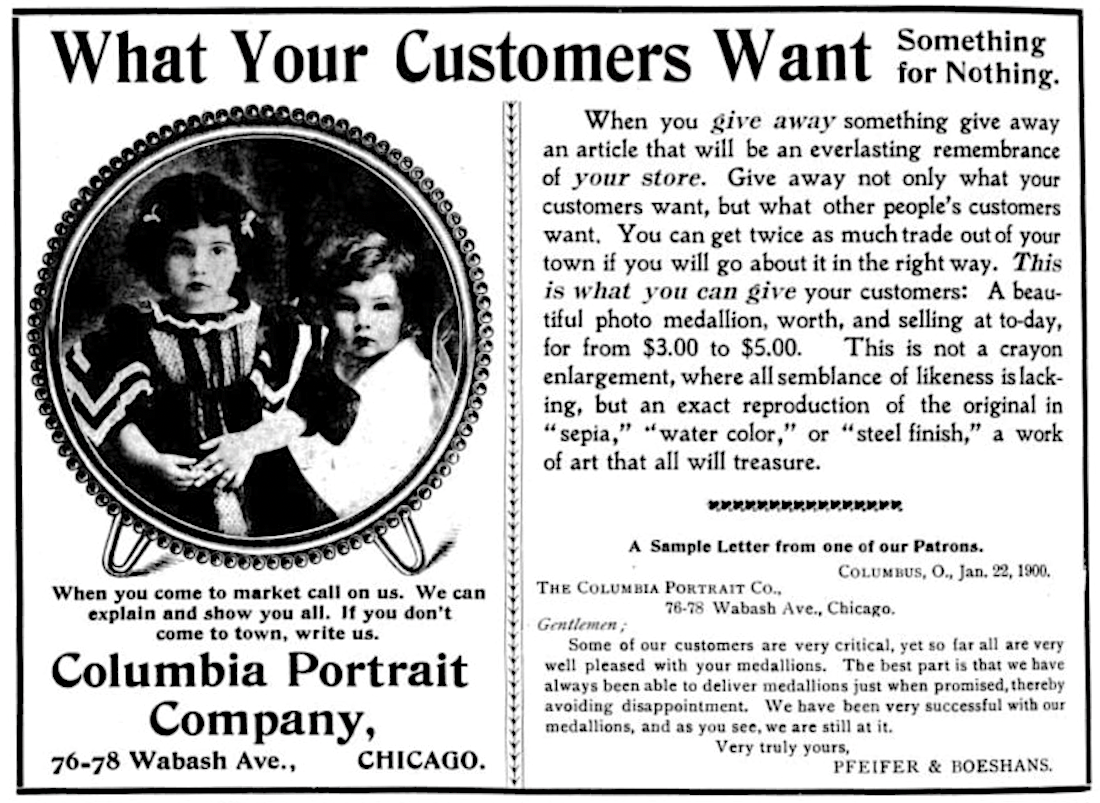

[1900 advertisement]

Sources:

“Admits Being a Swindler” – Chicago Tribune, May 6, 1893

“Eyes are Windows to Character, Says Movie Studio Head” – The Evening News (Harrisburg, PA), May 7, 1919

“Izri W. Lederer” – Chicago Tribune, December 11, 1951

“Restaurant Chain Leases Loop Site for New Building” – Chicago Tribune, April 20, 1947

“Blaze in the Haymarket Theater Building Causes Alarm” – Chicago Tribune, Oct 4, 1904

A sincere thank you to museum patron Ann De Cloux of Dubuque, Iowa, for donating the medallion of the unknown boy in the garden to our collection!

Archived Reader Comments:

“There were other long-lived companies who made these sorts of photographic medallions for use in headstones; they are quite common in the Eastern European cemeteries on the northwest side.” —Mike Gebert, 2018

My dad passed away in Quebec City, Canada in December 2023, I decided to go thru some of his stuff and discovered pictures of my great grand parents probably from around 1915 printed black and white on cardboard frame with on the back : to duplicate return this photo: Columbia medaillon studios Chicago, ILL.Unbelievable treasures we can find.

I have two round photos of Columbia made in Leipzig (Germany). Signed COLUMBIA LEIPZIG

I have a marked medallion of mother Mary I received it after my grandmother passed away. It has the exact same marking on the back. I’m wondering if there’s history behind this specific medallion?

I inherited 3 of these. I still have two of them. One is printed directly on the metal, but 2 of them

appear to have been printed on paper, and put into the metal frame. One I lost due to having it in direct sunlight. It split, and peeled away from the metal base,( my favorite one of course) so be careful how you display or store them.

Three 6” x 6” round medallions with ncovered under floorboard of 1850’s home in Excelsior Springs MO. My son is planning a trip to New York to sell them and believes them to be portraits you of Jesse James, Frank James and Martha Jane Presgrove. I am skeptical to say the least! Any suggestions on research of these medallions?

I inherited a 24″ x 28″ oval Columbia Portrait frame with rounded glass with picture of flowers. Does this have any value? If so, where could I sell it? Mona Stryker