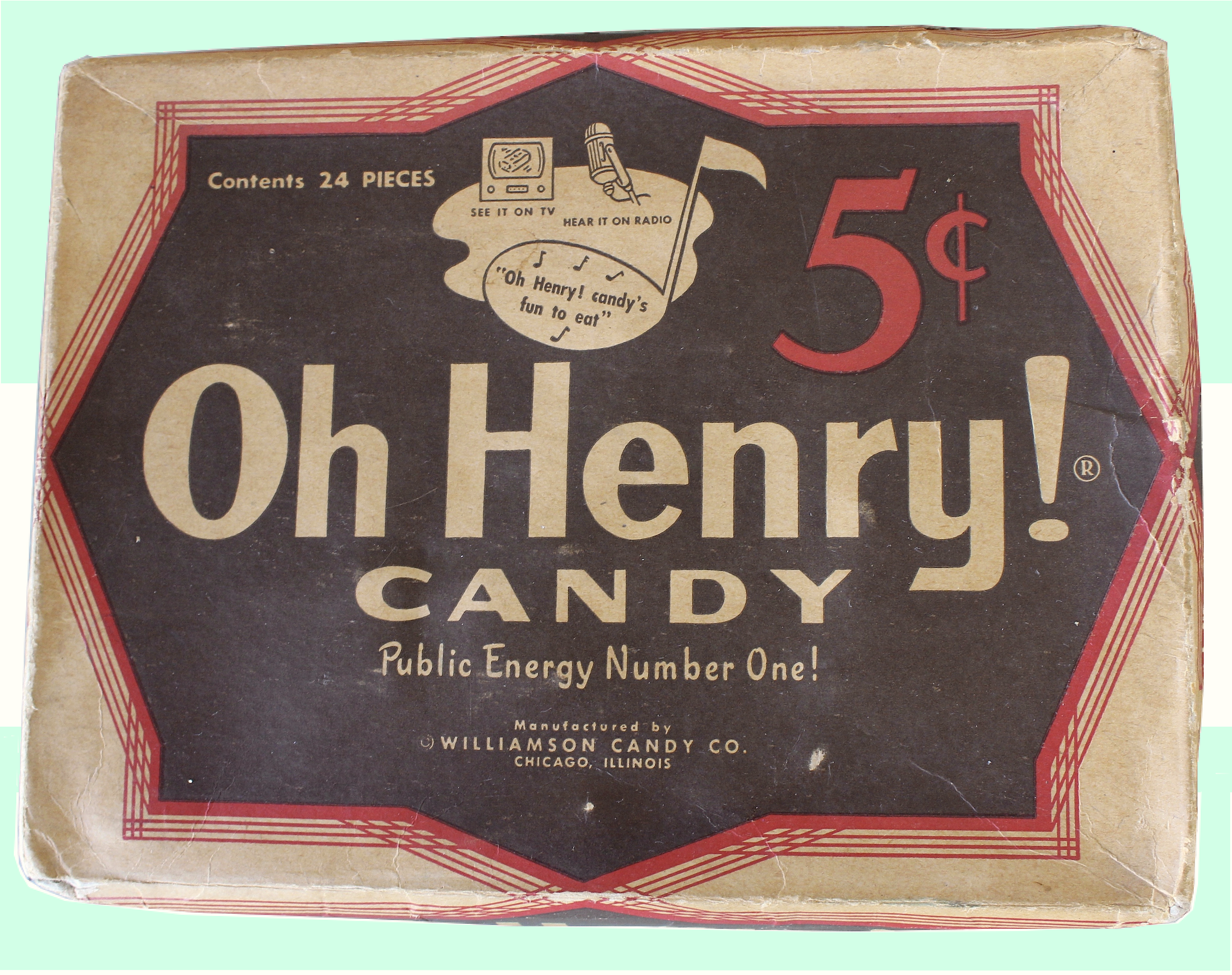

Museum Artifact: Oh Henry! Candy Bar Box, c. 1950s

Made By: Williamson Candy Company, 4701 W. Armitage Ave., Chicago, IL [Belmont Cragin]

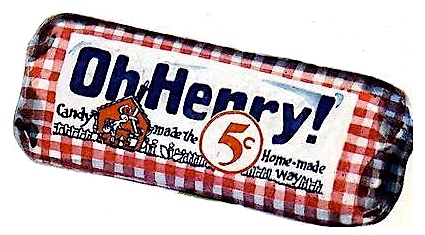

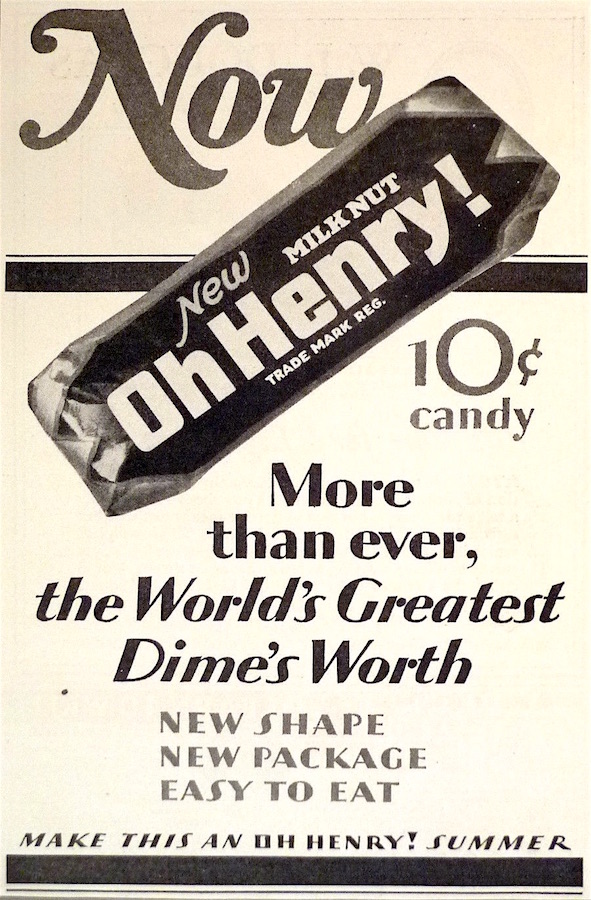

Introduced by the Williamson Candy Co. in 1920, the Oh Henry! was the first of Chicago’s holy trinity of chocolate/peanut/caramel candy bars, pre-dating the Baby Ruth (Curtiss Candy Co.) by a year* and Snickers (Mars, Inc.) by a decade. For my money, it was also the best tasting of the three, but the American public didn’t seem to agree. Sales steadily dwindled over the past few decades, and after Nestle sold the brand to the Ferrero SpA candy conglomerate in 2018, the Oh Henry! was abruptly discontinued—without so much as a tweet or a press release—just months shy of its 100th anniversary. Today, only a Canadian version of the Oh Henry—with an altogether different recipe owned by Hershey—remains on the market.

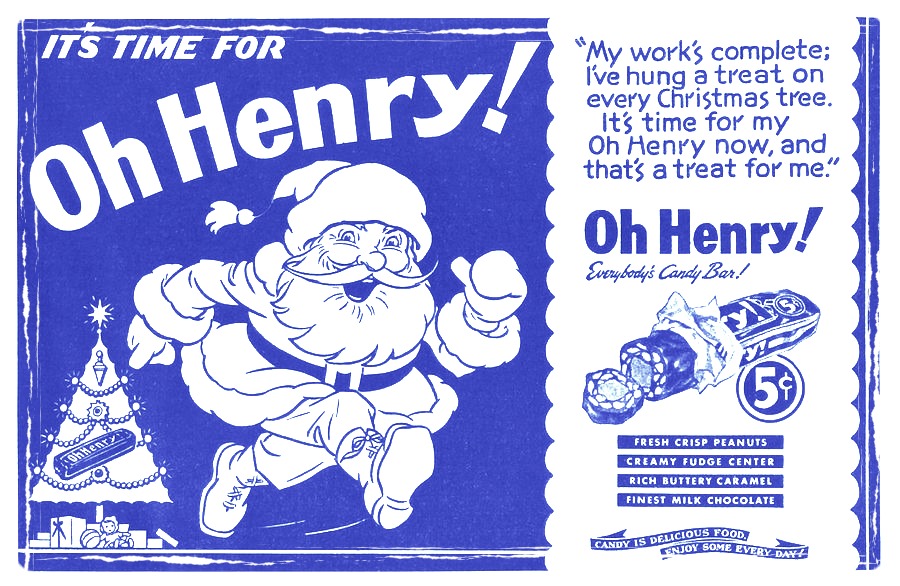

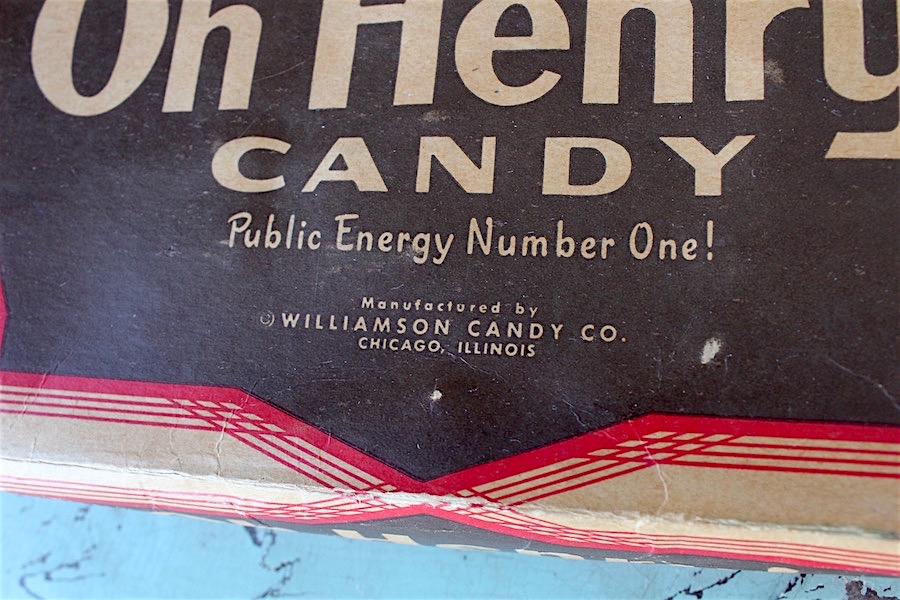

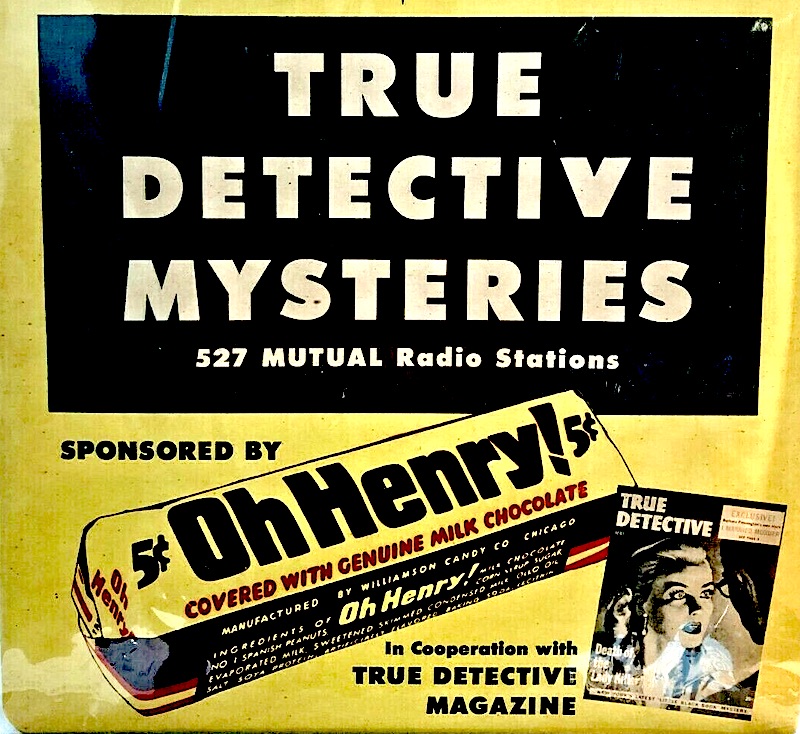

The 24-count display box from our museum collection dates from around the early 1950s, when the Chicago-made Oh Henry! was still a mainstay of the candy aisle and the self-described “Public Energy Number One!” That slogan was likely inspired by the Williamson Candy Company’s sponsorship tie-in with the True Detective Mysteries radio drama, which aired every Sunday evening at the time. Loyal listeners became quite familiar with the commercial jingle that ran before each broadcast:

[Sound of a ringing phone]

MAN’S VOICE: Hello? Hello?

WOMAN’S VOICE: Oh Henry?

MAN: Hold the phone! Hold the phone! It’s time for Oh Henry, public energy number one!

RADIO ANNOUNCER: Yes, it’s time for Oh Henry, America’s famous candy bar, to present, transcribed, True Detective Mysteries!

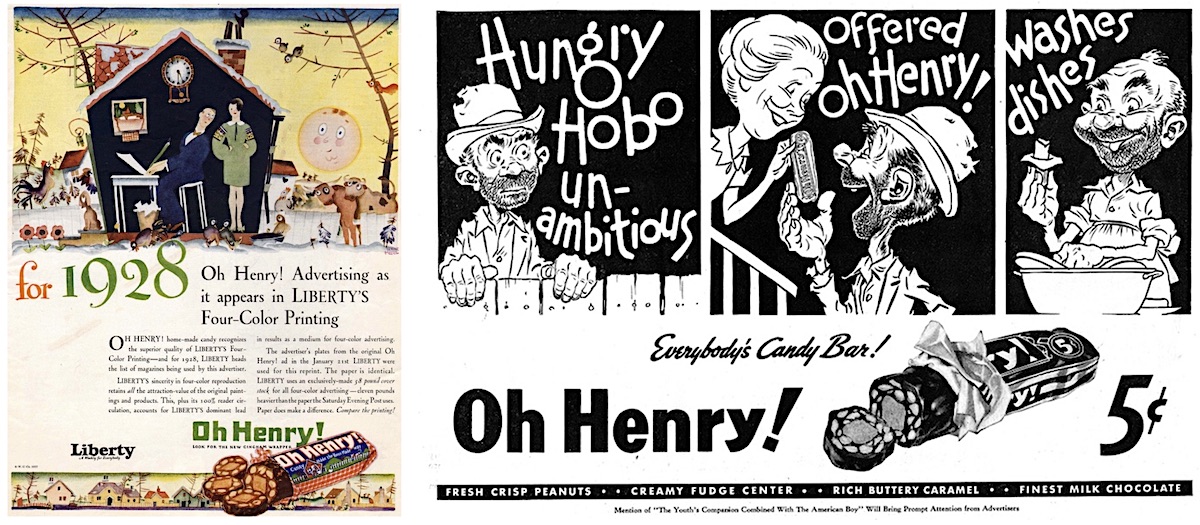

Much like radio itself, the Oh Henry! was already losing a little of its novelty by the dawning of the TV era. Distribution was still good, but compared with the sensation it had caused in the 1920s, the little bar in the yellow wrapper was now merely one of many candy bars in the crowd. Even so, Oh Henry’s creator, George H. Williamson, never lost his luster among his confectionery peers.

*Technically speaking, the Curtiss Candy Company’s “Kandy Kate” bar, which later evolved into the Baby Ruth, was on the market before the Oh Henry, but in terms of continuously operating brands, we give the crown to the latter.

[Workers gathered for a Christmas party in the Williamson Candy plant at 4701 W. Armitage Ave., 1925. This photo was donated by the family of the late Miss Frances Stencil, who was an 18 year-old employee at the plant during this time.]

History of Williamson Candy, Part I: “Candy Man of the Century”

In 1957, on the occasion of his 69th birthday, a large banquet was held at the Chicago Athletic Club in George Williamson ’s honor. Dozens of friends and colleagues from across the country came to toast a man who’d made a name for himself well beyond his one (and only) famous candy bar.

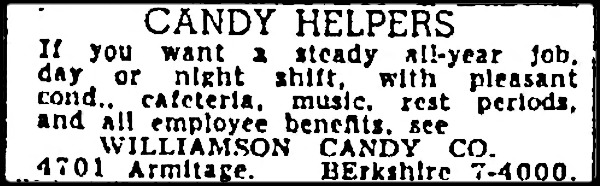

By now, Williamson [pictured here in his younger days] had served as president of both the National Confectioners Association and Illinois Manufacturers Association. He’d championed the cause of physically disabled workers while chairing the Easter Seals committee and Illinois Association for the Crippled, and he was one of the leading figures in the creation of the new lakefront convention center that would become McCormick Place. George’s pals included famous crooners (Bing Crosby) and crooks (Richard Nixon) alike, but his main factory at 4701 West Armitage Avenue seemed to reveal a fondness for his Chicago employees, as well—with wanted ads in the ’50s inviting workers to enjoy “music while you work, rest periods, cafeteria, and all benefits.”

By now, Williamson [pictured here in his younger days] had served as president of both the National Confectioners Association and Illinois Manufacturers Association. He’d championed the cause of physically disabled workers while chairing the Easter Seals committee and Illinois Association for the Crippled, and he was one of the leading figures in the creation of the new lakefront convention center that would become McCormick Place. George’s pals included famous crooners (Bing Crosby) and crooks (Richard Nixon) alike, but his main factory at 4701 West Armitage Avenue seemed to reveal a fondness for his Chicago employees, as well—with wanted ads in the ’50s inviting workers to enjoy “music while you work, rest periods, cafeteria, and all benefits.”

Williamson was hailed as the “candy man of the century” by the banquet’s attendees, and while there were certainly a few other fellas with a rightful claim to that title, few could match the charm of the self-made man.

Born in Minneapolis in 1888 and raised in Chicago, Williamson was the son of a city hall bookkeeper of Irish stock. As a teenager, young George had to start paying his own way, and he did so selling newspapers—if you’re picturing the classic flat-cap wearing newsie kid, that’s probably quite accurate.

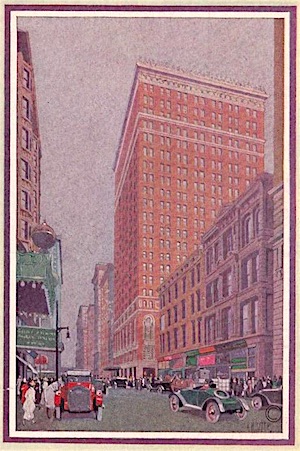

According to some accounts, Williamson eventually got a job with the Bunte Brothers candy firm, pushing their goodies around town. Over time, he became increasingly intrigued by the wonders of the confectionery business, and by the age of 26, used most of his $1,000 life savings to buy his own tiny sweet shop on Madison Street, across from the Morrison Hotel [pictured]. Weirdly, this is almost the exact same origin story ascribed to Emil Brach ten years prior, when he supposedly used his Bunte experience and $1,000 in life savings to start his first candy shop on North Avenue. Birds of a feather, I reckon. In any case, it was a humble entry into the candy trade for George Williamson.

According to some accounts, Williamson eventually got a job with the Bunte Brothers candy firm, pushing their goodies around town. Over time, he became increasingly intrigued by the wonders of the confectionery business, and by the age of 26, used most of his $1,000 life savings to buy his own tiny sweet shop on Madison Street, across from the Morrison Hotel [pictured]. Weirdly, this is almost the exact same origin story ascribed to Emil Brach ten years prior, when he supposedly used his Bunte experience and $1,000 in life savings to start his first candy shop on North Avenue. Birds of a feather, I reckon. In any case, it was a humble entry into the candy trade for George Williamson.

According to a 1925 syndicated article entitled “The Candy That Grew Up”: “Williamson was the entire staff himself. He made the candies, most of them, in a little kitchen in the rear. He was salesman through the day and janitor at night. He dressed the windows and decorated the store. But month by month the increasing sales proved that Williamson knew how to retail candy.”

With his wife May serving as vice president and Charles Croker as secretary, George organized the Williamson Candy Co. in an official capacity in 1917, and by 1920, he’d moved all his focus to manufacturing and distribution—purchasing factory space in a three-story building at 1038 North Ashland Avenue. Shortly thereafter, he abandoned all his other confections to make the massively popular Oh Henry his end all / be all product.

“In five years, the Williamson Candy Company, an Illinois corporation, has climbed to the top in the candy manufacturing business of America,” the Press Club of Chicago reported in 1922. “Its specialty, the Oh Henry! chocolate nut bar, is enjoying a wide sale because in it the company has concentrated all its efforts and because its blend comes not only of knowing candy but also people.”

[Left: 1038 N. Ashland Avenue, which served as the Williamson plant from 1920-1924. Right: Exterior of the larger factory at 4701 W. Armitage Ave., which opened in 1924 and remained the Oh Henry headquarters for many years. The building has since been demolished and replaced with a Home Depot. ]

Due to the tides of the marketplace, the Oh Henry! actually had a lower retail price in 1952 (5 cents) that it had during its initial run in the early 1920s (10 cents). Nonetheless, with less competition and strong demand, Williamson quickly outgrew its first factory and in 1924, relocated to a much larger, dedicated Oh Henry plant at 4701 W. Armitage Avenue, in the emerging industrial corridor of the Belmont Cragin neighborhood.

Running a successful business built around a single cheap, edible commodity came down to a “question of the good taste of the public and the good will of the trade,” as George Williamson once put it. But in the candy game, “taste” isn’t just about how delicious something is. It is, as the Chicago Press Club noted, about marketing to the sensibilities of your customers. And sometimes, that starts with just picking the right name.

II. So, Who the Hell Was Henry?

Along with sharing a hometown and most of the same ingredients, Oh Henry has a couple of other things in common with its longtime nemesis, the Baby Ruth. For one, they both were passed through the corporate grip of Nestle and Ferrero SpA in recent years. Secondly, both brands have pop-culturally ambiguous human names—which, in turn, have inspired a lot of revisionist mythologizing about their origins.

Along with sharing a hometown and most of the same ingredients, Oh Henry has a couple of other things in common with its longtime nemesis, the Baby Ruth. For one, they both were passed through the corporate grip of Nestle and Ferrero SpA in recent years. Secondly, both brands have pop-culturally ambiguous human names—which, in turn, have inspired a lot of revisionist mythologizing about their origins.

On the surface, the inspirations seem pretty cut and dried. “Baby Ruth” was clearly a play on “Babe Ruth”—the country’s most famous athlete at the time of the candy bar’s development. “Oh Henry,” similarly, was a tweak of “O. Henry”—one of the best selling writers of the early 20th century. And yet, thanks to America’s ever gullible faith in corporate folklore, neither of those perfectly good explanations are popularly accepted today.

As you can read about on our Curtiss Candy Company page, the makers of the Baby Ruth went to great lengths to deny any connection between their best-selling bar and the Great Bambino (almost certainly for legal reasons), claiming instead that the name was an innocent homage to a former first daughter of the United States—the dearly departed “Baby” Ruth Cleveland. The Williamson Candy Company, meanwhile, probably had fewer concerns about lawsuits coming from the estate of O. Henry (the writer, born William Sydney Porter, had died in 1910), but they certainly understood how promoting a good origin story was an important part of building a brand identity. And so, they cooked up a tale of their own.

Oh Henry Origin Story No. 1: A Boy Named Henry

One of the earliest versions I could find of the “corporate account” comes from a 1935 issue of Life magazine, published more than a decade after the Oh Henry bar’s debut. It describes an idyllic scene at George Williamson’s second candy shop at 442 N. Wells Street, circa 1919, with smiling youngsters serving as both the store’s main employees and clientele. One patron, in particular, a handsome young chap named Henry, becomes a favorite of the girls who work there, with his daily arrival “causing a sudden flurry of primping and fussing among the counter girls.”

“‘Oh, Henry!’ one of them sighed under her breath, and ‘Oh, Henry!’ the rest echoed. That was enough for Mr. Williamson. By 1924 Oh Henry! was a national catchword.”

“‘Oh, Henry!’ one of them sighed under her breath, and ‘Oh, Henry!’ the rest echoed. That was enough for Mr. Williamson. By 1924 Oh Henry! was a national catchword.”

As recently as 2017, when Oh Henry! was still part of the Nestle candy family, the corporate website basically stuck to that same 80 year-old narrative:

“Way back when, there was a little candy shop owned by George Williamson. A young fellow by the name of Henry who visited this shop on a regular basis became friendly with the young girls working there. They were soon asking favors of him, clamoring Oh Henry, will you do this?, and Oh Henry, will you do that? So often did Mr. Williamson hear the girls beseeching poor young Henry for help, that when he needed a name for a new candy bar, he called it OH HENRY! and filed a trademark application the following year.”

The story isn’t outlandish enough to dismiss outright, but the hazy details also make it impossible to substantiate. As a result, the “official” account has earned its fair share of detractors over the years, the loudest of whom can be found, weirdly enough, in a small town in Kansas.

Oh Henry Origin Story No. 2: A Guy Named (Tom) Henry

For several decades now, the most popular “alternative” Oh Henry tale has come from the owners of an old-fashioned sweet shop in Dexter, Kansas, called Henry’s Candy Co. The proprietors are direct descendants of a former Kansas candy man named Thomas Henry, and—as you’ve likely guessed—they believe he is the true namesake of the famous chocolate bar.

In the late 1910s, Tom Henry was indeed the manager of the Peerless Candy Co. in Arkansas City, Kansas (no relation to the Peerless Candy Co. of Chicago). According to legend, he invented a popular proto candy bar with chocolate and peanuts, which he called simply the “Tom Henry Bar.” It was so popular, in fact, that word of its glory reached the confectionery trade in Chicago, inspiring George Williamson to pay top dollar to buy the rights to the recipe in 1920. From there, Williamson changed the Henry Bar’s name to Oh Henry! (for some reason), thus maintaining a subtle reference to its original creator.

In the late 1910s, Tom Henry was indeed the manager of the Peerless Candy Co. in Arkansas City, Kansas (no relation to the Peerless Candy Co. of Chicago). According to legend, he invented a popular proto candy bar with chocolate and peanuts, which he called simply the “Tom Henry Bar.” It was so popular, in fact, that word of its glory reached the confectionery trade in Chicago, inspiring George Williamson to pay top dollar to buy the rights to the recipe in 1920. From there, Williamson changed the Henry Bar’s name to Oh Henry! (for some reason), thus maintaining a subtle reference to its original creator.

In recent years, countless newspaper articles and books have embraced this counter-narrative and cited the story as plain fact, but as of yet, I have encountered no hard evidence to prove that George Williamson and Tom Henry ever crossed paths, let alone cut a deal. There’s also no references to a “Tom Henry Bar” in Peerless ads of the time, nor any mentions of it in the local Arkansas City newspaper. This doesn’t mean it didn’t happen, but the entire basis for the story seems rooted in a family legend rather than any hard documentation (if you have any, please send it our way).

One of the earliest articles on the subject of Oh Henry’s origins, the aforementioned 1925 syndicated piece called “The Candy That Grew Up,” makes no mention of Tom Henry either, and indicates that George Williamson essentially acted alone.

“As more and more people came into the store, [Williamson] began to study what they liked in candy . . . the tastes they preferred . . . the quantity they bought . . . the prices they paid. He talked candy to them, learned what they liked, and why. And then, in the evenings, after he had closed the store, he used to go into the little kitchen and experiment with new candies, using the information he had gathered during the day.

“As more and more people came into the store, [Williamson] began to study what they liked in candy . . . the tastes they preferred . . . the quantity they bought . . . the prices they paid. He talked candy to them, learned what they liked, and why. And then, in the evenings, after he had closed the store, he used to go into the little kitchen and experiment with new candies, using the information he had gathered during the day.

“. . . One of the candies began to show larger orders than usual. Unsolicited orders came in from jobbers in Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin. This was the now famous Oh Henry!”

Another early article, from a 1926 piece in Modern Business, also credits Williamson: “While a clerk was doing the selling, Mr. Williamson was experimenting in the rear of the store with his kettles and it was here that the confection ‘Oh Henry!’ was worked out.”

Both of those accounts could be pure fluff, too, but nonetheless, they were at least composed just a few years after the events in question.

As for Tom Henry, he carried on with a long career in confections even after supposedly selling off his billion dollar bar. Later, his son Patrick took over the family business, opening the candy shop in Dexter in the 1950s. Today, that shop—Henry’s Candy—is still a local landmark, and it’s still run by the same family, including Tom Henry’s granddaughter and great granddaughters. Part of their claim to fame remains the family’s supposed connection to the Oh Henry bar, so much so that they sell a treat called the “Momma Henry”—based on the “original” Oh Henry recipe.

Other, Less Popular Explanations

Again, once you sift through the fun folklore, you’re generally left with the same logical conclusion—the Oh Henry was probably punnily named after the writer O. Henry. Nonetheless, there are a few other interesting, if a bit far fetched, potential sources of inspiration that line-up chronologically.

♦ There was a Broadway play in 1920 called “Oh Henry!” ♦

In the very months leading up to George Williamson’s branding of his new candy bar, there was a brand new, three-act theatrical comedy called “Oh Henry!” (complete with the exclamation point) that debuted at the Fulton Theatre in New York, with satellite productions across the country. Written by Bide Dudley—who was better known as a New York theater critic—the farce took aim at the recent passage of the 18th amendment. Unfortunately, according to a review in the New York Herald (presumably NOT written by Dudley himself), the play—“called with no explanation ‘Oh Henry’—must have given the coup de grace to every joke on the subject of prohibition. Nothing could have rendered the three acts other than abysmal in their dullness. But the direction was as inept as every other feature of the performance. . . . No playwright will ever dare attempt anything of the kind after the thick compendium of selected stupidities which the text revealed.”

In the very months leading up to George Williamson’s branding of his new candy bar, there was a brand new, three-act theatrical comedy called “Oh Henry!” (complete with the exclamation point) that debuted at the Fulton Theatre in New York, with satellite productions across the country. Written by Bide Dudley—who was better known as a New York theater critic—the farce took aim at the recent passage of the 18th amendment. Unfortunately, according to a review in the New York Herald (presumably NOT written by Dudley himself), the play—“called with no explanation ‘Oh Henry’—must have given the coup de grace to every joke on the subject of prohibition. Nothing could have rendered the three acts other than abysmal in their dullness. But the direction was as inept as every other feature of the performance. . . . No playwright will ever dare attempt anything of the kind after the thick compendium of selected stupidities which the text revealed.”

Ouch. Doesn’t sound like a blockbuster worthy of honoring on a candy wrapper.

♦ There was a silent film in 1916 called “Oh! Oh! Oh! Henery” ♦

The two-reel Thanhouser comedy starring J. C. Yorke and Frances Keyes was routinely misspelled in newspapers and on theater marquees as “Oh Oh Henry” rather than the intended H-E-N-E-R-Y. Regardless, George Williamson could have seen the flick for half the price of an Oh Henry candy bar. In 1916, Moving Picture World called it “an intensely amusing two-part comedy showing how the faithful wife is deceived, and how the jealous wife undergoes needless hours of misery through the conjurings of her imagination. This number will be much enjoyed by old and young.”

The two-reel Thanhouser comedy starring J. C. Yorke and Frances Keyes was routinely misspelled in newspapers and on theater marquees as “Oh Oh Henry” rather than the intended H-E-N-E-R-Y. Regardless, George Williamson could have seen the flick for half the price of an Oh Henry candy bar. In 1916, Moving Picture World called it “an intensely amusing two-part comedy showing how the faithful wife is deceived, and how the jealous wife undergoes needless hours of misery through the conjurings of her imagination. This number will be much enjoyed by old and young.”

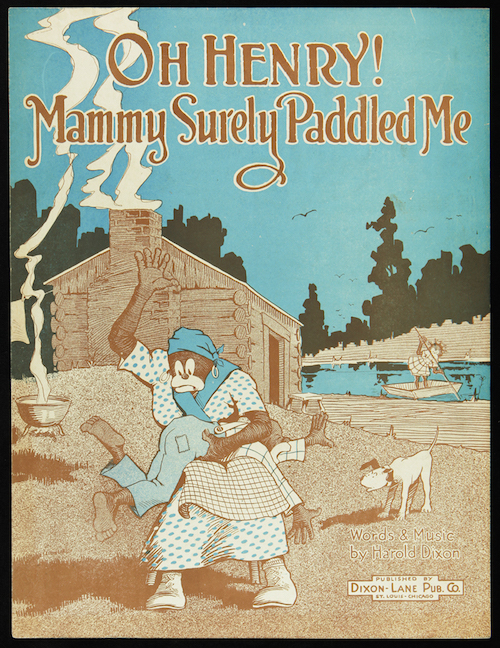

♦ There was a hit song in 1918 called “Oh Henry! Mammy Surely Paddled Me!” ♦

Harold Dixon was a Chicago-based songwriter who penned his fair share of racist tunes in the 1910s and ‘20s—those being all the rage during the period. There’s no way to know if his 1918 composition “Oh Henry! Mammy Surely Paddled Me!” ever found its way to George Williamson’s gramophone, but one can only hope it didn’t play any role in naming his favorite confection.

Harold Dixon was a Chicago-based songwriter who penned his fair share of racist tunes in the 1910s and ‘20s—those being all the rage during the period. There’s no way to know if his 1918 composition “Oh Henry! Mammy Surely Paddled Me!” ever found its way to George Williamson’s gramophone, but one can only hope it didn’t play any role in naming his favorite confection.

Incidentally, Harold Dixon had a much bigger success that same year with a World War I inspired song called “You Great Big Handsome Marine.” The first two lines of that classic were “Oh you great big handsome Marine / You are the niftiest fellow I’ve seen,” if that gives you any incite into his general oeuvre.

Incidentally, we’ve also discovered another, even earlier song, titled “Henry, Oh Henry (Your Ma Wants You),” which was published in 1912 by Aubrey Stauffer & Co. of Chicago. This tune, written by Grace LeBoy and lyrcist Gus Kahn, seems to have been less patently racist, but still thematically concerned with the apparent humor of child abuse.

♦ An old man on the internet knows where the name REALLY came from! ♦

In 2013, a visitor to the website candyblog.net dropped a potentially earth-shattering anecdote on the Oh Henry page comment board (where all hard news is born).

“I am C. Kenneth Crocker, the eldest (95+) son of Charles Henry Crocker. My father and my god parents, Mae and George Williamson, started the candy company. The stories of the naming of the bar are untrue! The bar had to be wrapped before it was named!

“My father and George were out to lunch and midway through the lunch my father called to the waiter for a refill—‘Oh Henry’ . . . ‘That’s the name of the bar,’ my father said.

“I hope this will clarify the age old story (false) about the naming of the bar.

Sincerely,

Ken Crocker”

A man named Charles Crocker was indeed the first secretary of the Williamson Candy Co., so maybe this faceless avatar on the internet really is his son and really DOES know the true, albeit kinda anti-climactic origin story. Who’s to say for sure?

[Workers at the Williamson plant move the Oh Henry’s interior buttercream mixtures from hot kettles onto large slabs for cooling, c. 1925. From Leslie Goddard’s book Chicago’s Sweet Candy History]

III. Mysteries Sell

It might be a bit contradictory to say this after spending all that time trying to unravel the Oh Henry origin riddle, but sometimes—as good marketing proves—it’s what the customer doesn’t know that interests them the most. And in the early days of the Oh Henry, mystery was certainly weaponized to help turn the candy bar from a local hit into a national brand.

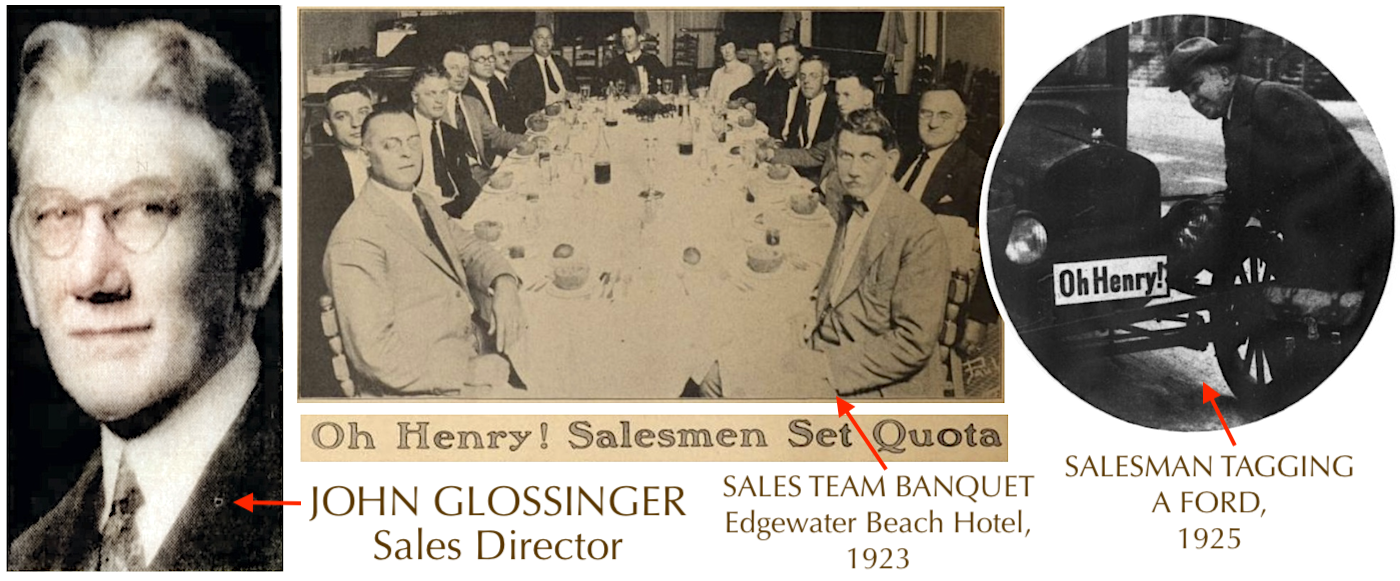

George Williamson deserves plenty of the credit, as does his wife May, who probably played a much bigger role than we’ll ever know [early ads even refer to the company as “Aunty May’s” rather than the Williamson Candy Co]. They took the initial risk of paying a major ad agency, the Fred M. Randall Company, to create a national marketing campaign for the Oh Henry!—unheard of for a candy bar in 1922. It was Williamson’s new sales manager, however—a man named John Glossinger—who might have been most responsible for the Oh Henry’s nationwide ascension.

In 1922, George and May Williamson were still living with George’s parents. The future “candy man of the century” was just 34 years old, and while his skills as a salesman were already advanced, he needed a more experienced cat from the national trade to help him manage the Oh Henry’s out-of-control growth. To this end, Williamson made an offer to John Glossinger—effectively poaching the 54 year-old sales guru from another candy maker, Philadelphia’s H. O. Wilbur & Sons.

Glossinger, a former farm boy from Xenia, Ohio, had made is name in New York’s tobacco trade for many years. He cast a long shadow, he succeeded everywhere he went, and his words carried more weight than a Scandinavian Strongman.

Just months before joining the Williamson Candy Co., Glossinger had delivered a speech at a 1922 confectioners convention in Philly, citing inefficiency and wasted expenses as the biggest problems plaguing the industry. “Manufacturer, jobber and retailer are all in business for one purpose,” he said, “that is, to make a profit. Therefore, we have a common starting point. . . . Let’s get together and bring the light of reason into our business!”

Now, tasked with bringing Oh Henry! to the wide expanse of America, Glossinger backed up his talk with walking—literally. He convinced Williamson to put boots on the ground, city by city, with a specific type of guerrilla marketing campaign that was decades ahead of its time.

“We disregard both jobber and retailer and go straight to the consumer, not with any sales appeal, but an appeal to their curiosity,” Glossinger explained in a 1925 editorial in Sales Management magazine. “There is where we register 100 percent, as every man, woman and child is curious and will give a world of free publicity if you can arouse their curiosity.”

“Our method is very simple,” Glossinger continued. “We take a plain card which has nothing on it but Oh Henry! and start our salesmen out, putting one on the front of the radiator of every Ford car they can find on the city streets. The people ask what [the card] is, but our men are instructed to give no information but simply to say, ‘Watch the newspapers.’ After we have a few thousands Fords running around the town carrying this card, everybody is guessing what it is.”

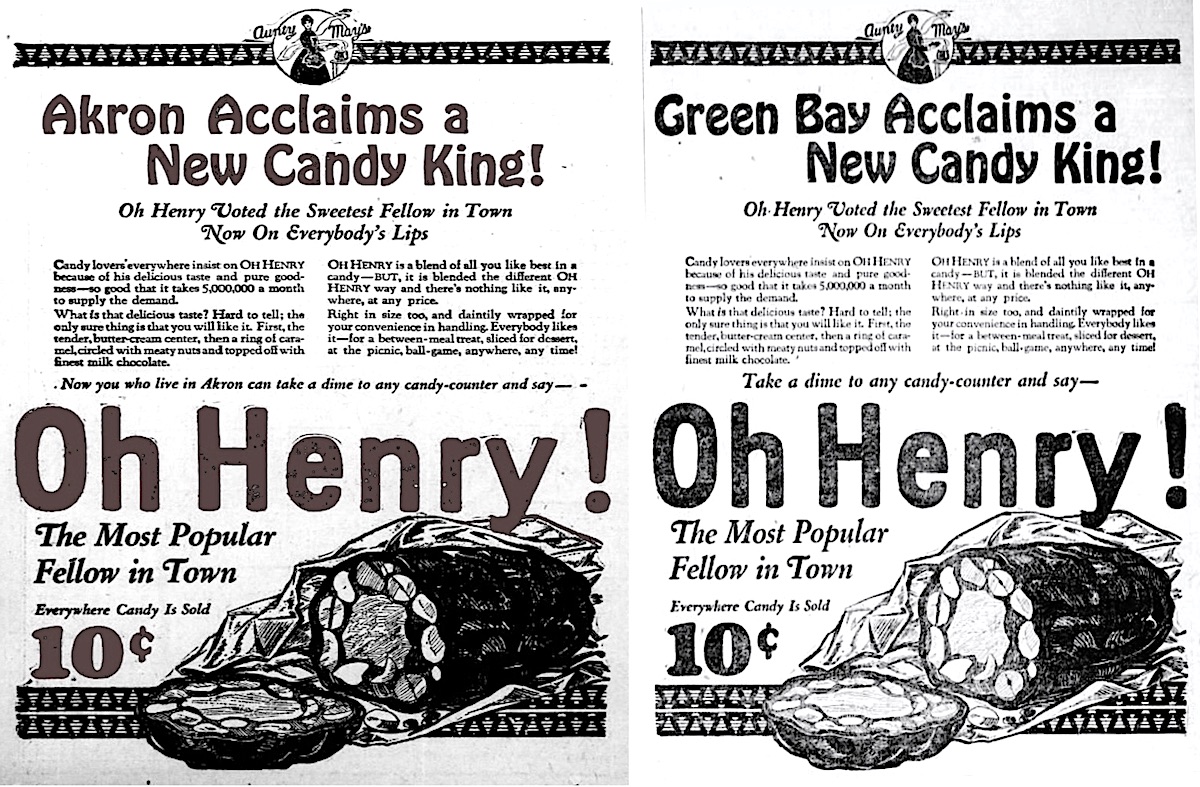

As part of the carefully planned scheme, Glossinger would start rolling out newspaper ads in the town a few days after the radiator cards appeared, gradually solving the mystery and telling the Oh Henry’s story through a local lens.

[Midwestern cities like Akron, Ohio, and Green Bay, Wisconsin, were systematically introduced to the Oh Henry in 1922 and 1923 through John Glossinger’s combo of guerrilla marketing and newspaper ads]

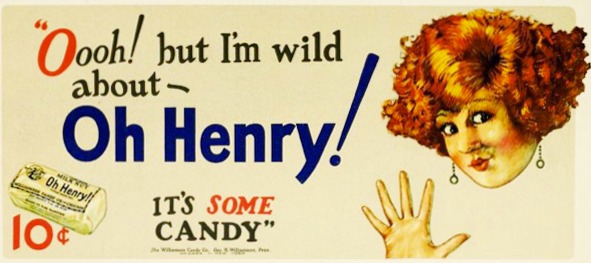

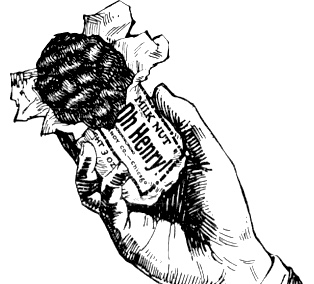

As the campaign reached new towns, people were routinely caught up in the fun, with their curiosity carrying straight on to the candy counter. It didn’t matter whether the Oh Henry bar itself originated in Chicago, New York, or Saskatchewan. But in some of the advertising, Williamson did at least boast that the bar’s “goodness, freshness and popularity keeps two Chicago factories working night and day.” Some occasional slogans popped up, as well: “a fine piece of dollar candy for a dime” and “Oh Henry – the most popular fellow in town.”

Soon, high society women were cutting up the comparatively posh 10-cent bars and serving them at fancy parties. And by end of 1922, kids thousands of miles from Chicago were begging for Oh Henry in their Christmas stockings. With another facility opened in Brooklyn, New York, Williamson was reportedly producing 5 million Oh Henry bars PER MONTH that year. The only downside of such productivity, as they would find, was the inevitable army of copycats trying to nudge their way on to the bandwagon.

[Women sorting Oh Henry chocolate through cooling machines at the rate of 18,000 bars per hour. From Leslie Goddard’s book Chicago’s Sweet Candy History]

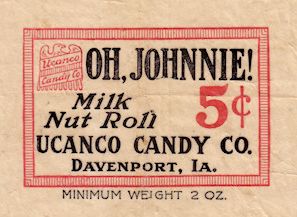

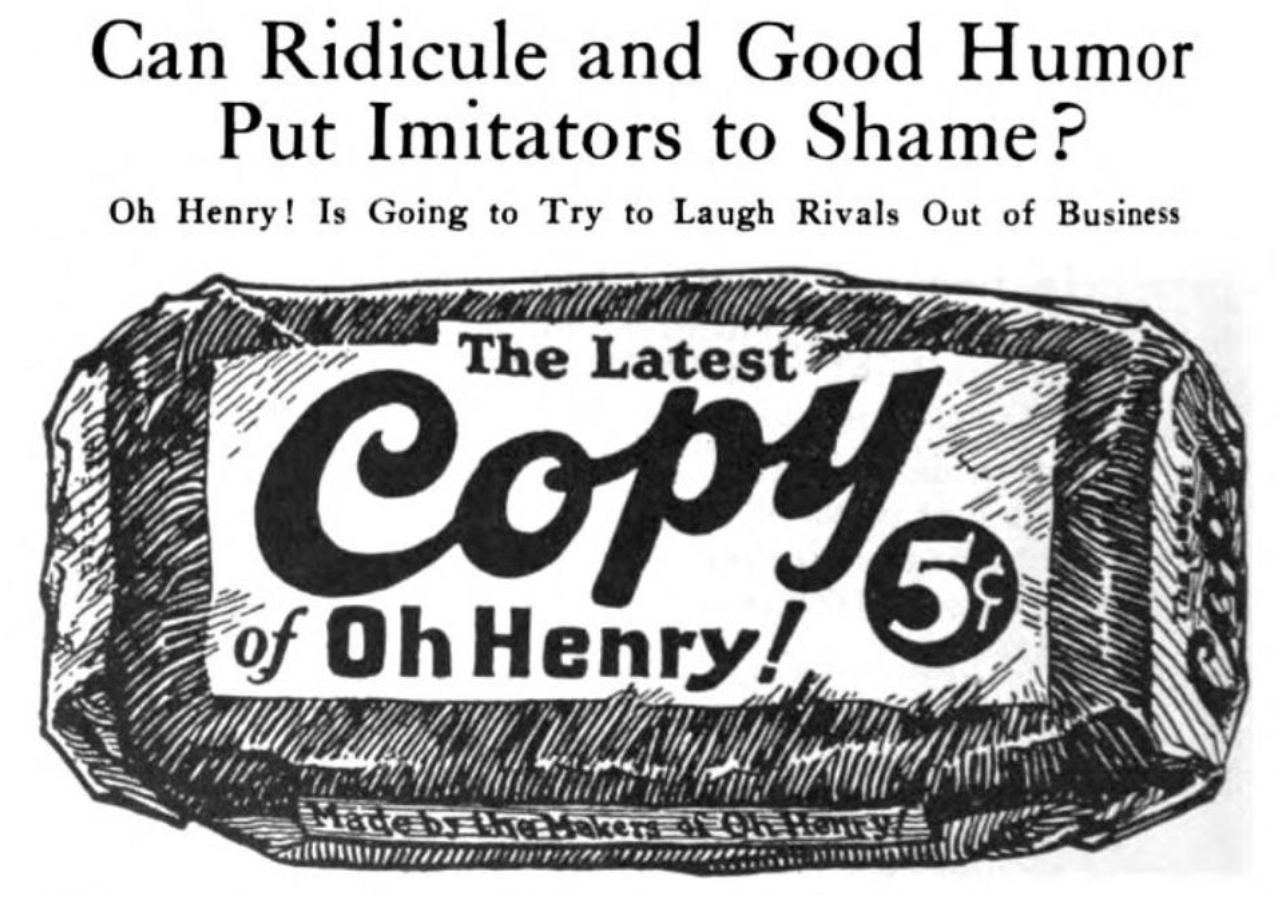

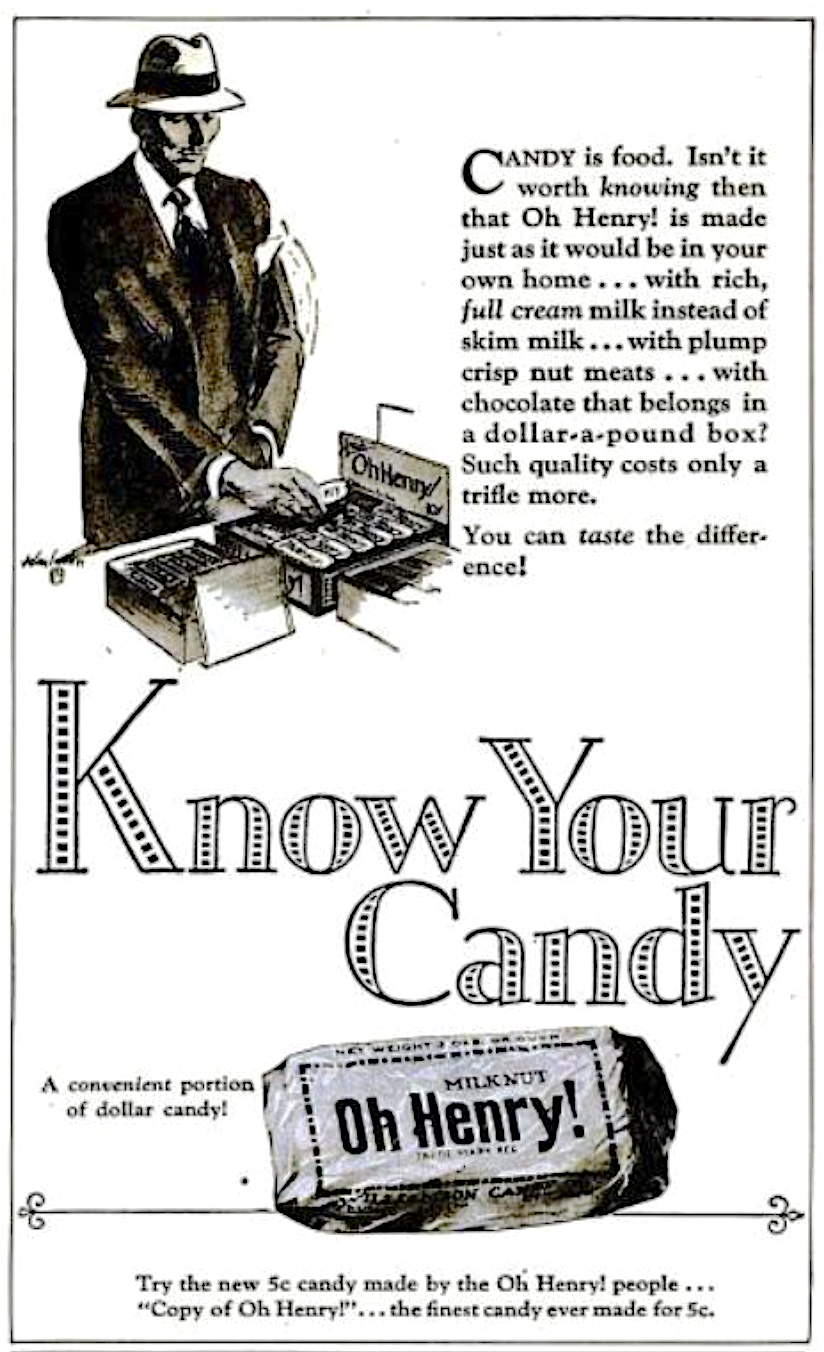

IV. “The Latest Copy of Oh Henry”

I suppose the only thing consumers like more than a mystery is, paradoxically, familiarity. And so the mid 1920s brought a boat load of new chocolate, peanut, and caramel style bars trying to cut in on Oh Henry’s turf. Some, like the Baby Ruth, became giant successes in their own right. Others, like the five-cent “Oh Johnnie!” bar (made by Iowa’s Ucanco Candy Company) wound up getting sued for trademark infringement. It was one thing to blatantly rip someone off. It was another to undercut them on price. That could NOT stand.

Williamson won its case against Ucanco, but frustration was mounting. There were far too many copycat candy makers and undercutting salesmen out there. It would be impossible to take them all on, one at a time.

Williamson won its case against Ucanco, but frustration was mounting. There were far too many copycat candy makers and undercutting salesmen out there. It would be impossible to take them all on, one at a time.

In January of 1925, John Glossinger hit the convention circuit, preaching respect and cooperation among competitors in the confectionery business. “The salesman should be the last man to cut prices,” he said. “His income, his profit depends upon what he puts in the cash register. Therefore what he cuts in prices cuts into his income. . . . Good will must be sold just as merchandise.”

The peace talks weren’t getting the job done, though. Williamson needed a more aggressive approach.

And so, in 1926, a whole bunch of stuff happened. First, the Williamson Candy Co. merged with the General Candy Company out of St. Louis, with George Williamson serving as president of the new corporation. Second, a new ad agency was brought in—Chicago’s H. W. Kastor & Son, Inc.—with the goal of helping Oh Henry! fend off its attackers. Now, with some extra spending cash and creative energy at their disposal, Williamson and Glossinger hatched a marketing strategy that would make the old Ford radiator trick seem tame by comparison. It began by applying for a trademark on a new brand of candy bar. Its name: “The Latest Copy of Oh Henry.”

[Headline from a 1926 issue of Printer’s Ink, along with a sketch of Williamson’s satirical “Latest Copy of Oh Henry!” packaging]

It was satire—a joke. And yet, like the best jokes, it went the distance. George Williamson didn’t just register and win the trademark; he legitimately had the “Copy” bar produced in his factories, shipped to dealers, and advertised in some publications. Its selling price was, hilariously, 5 cents. George was willing to undercut himself to make a point. The Copy’s wrapper even came with a special notice printed on it:

“Due to the wide spread practice of imitating Oh Henry!, we, the sole makers of that justly famous candy bar, feel that it is our duty to the candy loving public to offer the finest imitation of Oh Henry! that can be made for 5c. Hence, this ‘Copy’ bar. Of course, it’s not as good nor as large as Oh Henry!—it couldn’t be for 5c.”

To complete one of the all-time great F-U promotional gimmicks, Williamson went one step further and announced the concurrent founding of the “Confectioners’ Copy Club” in the November 1926 issue of the Confectioners Journal. The delightfully meta concept was put together in anticipation of copycats inevitably copying the “Copy” bar itself.

“Sometime ago when Oh Henry! came into prominence, there was such a rush of imitators that the candy trade, both wholesale and retail, was seriously embarrassed. Few were able to keep up with the daily growing list of imitations.

“Sometime ago when Oh Henry! came into prominence, there was such a rush of imitators that the candy trade, both wholesale and retail, was seriously embarrassed. Few were able to keep up with the daily growing list of imitations.

“To forestall this difficulty when ‘COPY’ begins to be copied, and also to engender a clubbier feeling among the manufacturers who copy ‘COPY,’ we are organizing the CONFECTIONERS’ ‘COPY’ CLUB.

“The only requisite for membership in the COPY CLUB is the manufacture of a bar similar to ‘COPY’ … From month to month the names of the duly self-elected members will be published in the roster of the COPY CLUB in these pages.

“By this means we hope to keep the candy trade posted as to who is copying ‘COPY’ so that there will be no difficulty in identifying the clever manufacturers who have had the originality to make a bar like ‘COPY.’”

If trolling was ever a thing in the 1920s, this is what it would have looked like. Williamson, having seen the Oh Henry’s No. 1 ranking usurped by the cheaper Baby Ruth and its good name tarnished by inferior mimics, absolutely put the industry on notice with a hilarious smackdown.

The ‘Copy’ experiment, while short lived, was a key step in establishing the Oh Henry as a “higher class” of candy bar—five cents more expensive than the cheapies, perhaps, but also far more versatile for the discriminating taste. It was a candy bar fit for grownups.

“Slicing Oh Henry! is a novelty in candy,” one ad read. “. . . a delightful one, too. And since Chicago women started slicing Oh Henry! a year or so ago, for teas, bridge games, Mah-Jongg and the family’s use, the novelty of this new way of serving candy has taken Oh Henry! into many, many homes.”

“Slicing Oh Henry! is a novelty in candy,” one ad read. “. . . a delightful one, too. And since Chicago women started slicing Oh Henry! a year or so ago, for teas, bridge games, Mah-Jongg and the family’s use, the novelty of this new way of serving candy has taken Oh Henry! into many, many homes.”

By the end of 1926, Williamson made its biggest play yet to that adult female demographic, releasing a recipe book with ideas for utilizing the Oh Henry bar as an ingredient in various other desserts—cakes, icings, puddings, and more. It was called “60 New Ways to Serve a Famous Candy,” and was edited down from over 8,000 recommendations mailed in by women throughout the year.

The recipe book might have been John Glossinger’s final contribution to the Oh Henry brand. He had returned to Philadelphia by 1927, hired by another firm to work his magic. He remained a creative force for decades to come, and died in 1968 at the age of 99.

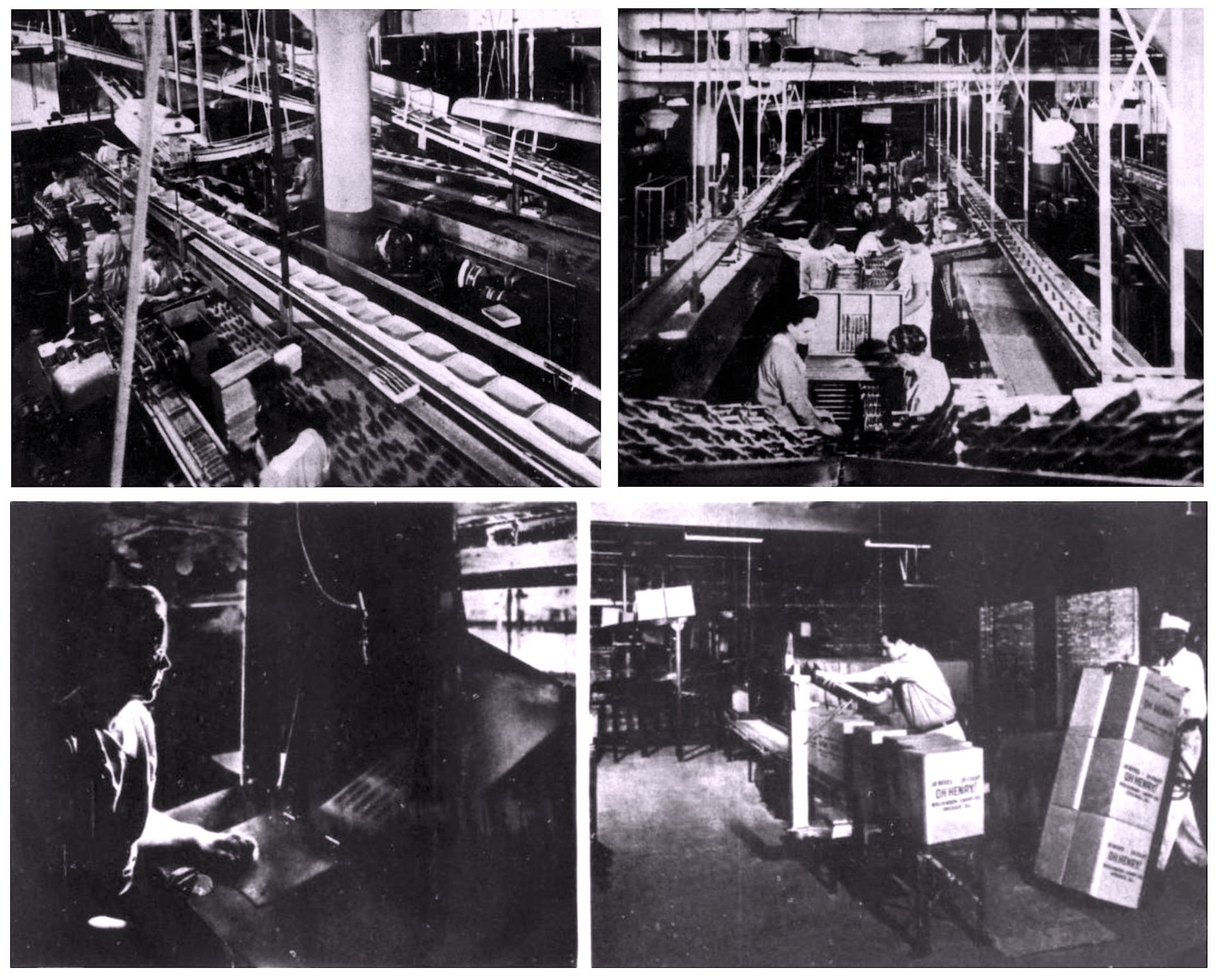

[In the packing room of the Oh Henry plant, seen here in 1925, women originally hand wrapped and packaged every bar. Each conveyer belt would carry 15 to 17 tons of candy bars into the packing room every 8-hour shift. The process was finally automated later in the 1930s and ’40s. From Leslie Goddard’s book Chicago’s Sweet Candy History.]

V. At Armitage & Cicero

By the late 1920s, Williamson Candy (now alternatively known as the General Candy Corporation) had settled into its expansive factory at 4701 W. Armitage Avenue. And while the economic collapse of the 1930s did eventually force the company to begrudgingly drop the Oh Henry’s price down to 5 cents, the Armitage plant remained a major source of jobs in the area, employing a team of more than 500 workers through most of the decade. In tough times, cheap chocolate was no less appealing to the public that it had been in the roaring ‘20s.

[The colorful optimism of a 1928 Oh Henry ad (left) gives way to an insulting depiction of a hungry hobo in 1938. No longer an upscale 10-cent bar, Oh Henry becomes “Everybody’s Candy Bar” at 5 cents]

A world war didn’t do much damage to Oh Henry! sales, either. In the early 1940s, new wrapping machines were installed in the Armitage plant, cutting paper costs by 35 percent and wrapping 100 bars per minute. This, along with the hiring of more “unconventional” workers, helped counteract the loss of materials and laborers during World War II.

“Mr. Williamson employs 20 or 30 people whom most employers would consider unemployable, paying normal wages for normal work,” the Decatur Herald reported in 1942, noting that the Oh Henry factory was uniquely “enlightened” in recognizing the value of handicapped laborers.

“Mr. Williamson employs 20 or 30 people whom most employers would consider unemployable, paying normal wages for normal work,” the Decatur Herald reported in 1942, noting that the Oh Henry factory was uniquely “enlightened” in recognizing the value of handicapped laborers.

“Mr. Williamson is not an altruist. His policy is not governed by sentiment. He does not feel that he is conferring any favor when he puts a cripple to work. The shoe, he says, is on the other foot.”

Meanwhile, as more of Williamson’s “able bodied” workers headed overseas to the battlefront, those same soldiers gradually formed a new, devoted customer base for the Oh Henry during the war years.

“Despite the personnel problem which holds back production, we are making all the candy we can,” company vice president Charles F. Scully told the Tribune in 1943. “The war has proved that candy is a food and the army is continually taking a larger portion of our production. The public is getting less, but seems to be consuming more.”

Scully, who had joined the company way back in 1921, eventually took over the presidency of Williamson Candy in 1949, with George Williamson moving into the Chairman role at age 61. Through it all, Oh Henry! had remained the company’s main noteworthy contribution, with lesser-known titles coming and going, including the Oh Mabel!, Walnut Fluff, Big Hearted Al, Air Pilot, Big Alarm, Guess What, and Amos n’ Andy bar.

In the post-war years, Scully and Williamson did their best to create a community atmosphere among the workers on Armitage, offering benefit packages and a “pleasant” working environment. Some employees were singled out for special recognition, like Bernice Zarr—who spent 20 years at the factory without ever missing a day or being late to work. Bernice had a luncheon held in her honor in 1950, and was given a watch to symbolize her accomplishment. “I’m fortunate to never tire of my job,” she said. “I never get up in the morning wishing I didn’t have to go to work that day.”

In the 1960s, the look of the typical Williamson worker began to change. Increasingly, an influx of Hispanic immigrants and poor laborers from the South came to Chicago to work at the plant—willing to take menial wages.

In the 1960s, the look of the typical Williamson worker began to change. Increasingly, an influx of Hispanic immigrants and poor laborers from the South came to Chicago to work at the plant—willing to take menial wages.

In Chad Berry’s book Southern Migrants, Northern Exiles, a West Virginian named Ozzie Stroud shared his memories of joining the Williamson plant in the late 1960s, shortly after the company was purchased by the Warner-Lambert pharmaceutical company.

“I had a sister living in Chicago at the time,” Stroud said, “and I called her and told her I was coming up. I left home with twenty dollars in my pocket.

“The first summer I went up there it was a common thing that if you wanted a job you could go to Chicago, and you could go to this one certain factory and get a job. It was the Williamson Candy Company, on the corner of Armitage and Cicero. They made O’Henry [sic] candy bars. I went out and got a job there [his task was taking the centers of the candy bar and dumping them on a conveyor belt].

[Inside the Williamson Candy plant, 1952 . . . Top Left: Packaging lines include machines that automatically wrap 100 bars per minute. Top Right: Workers had boxtops to Oh Henry boxes already auto-filled with wraps bars. Bottom Left: X-ray inspectors ensure each Oh Henry box has the proper number of bars and doesn’t contain any foreign objects. Bottom Right: Shipping department loads up boxes, each containing sixteen 24-count Oh Henry boxes, or 384 chocolate bars per shipping box; roughly 300 million per year.]

“I never will forget it. $1.53 an hour. And that was pretty good money when you figured that for a tool and die maker back then, I think the top pay was $4.00 an hour.”

The writer Berry noted that when Stroud was offered a nickel raise to move to the shipping department, he quickly realized why he was needed. “He was the only one who could read.”

Right around the same time Ozzie Stroud was working at the Williamson factory, in 1967, George H. Williamson died at the age of 79. It was certainly the end of an era. Since the business was sold to Warner-Lambert in 1965, the aging Armitage Avenue factory seemed set on a path to doom.

Right around the same time Ozzie Stroud was working at the Williamson factory, in 1967, George H. Williamson died at the age of 79. It was certainly the end of an era. Since the business was sold to Warner-Lambert in 1965, the aging Armitage Avenue factory seemed set on a path to doom.

Sure enough, Warner-Lambert soon sold Oh Henry! to Terson, Inc., which in turn, sold it off to Nestle in the 1980s (Hershey owns the rights to the bar in Canada, but as noted earlier, uses a different recipe). By then, Oh Henry’s production had already left Chicago behind.

Sadly, much like Otto Schnering and the Curtiss Candy Co., George Williamson’s decision to name his candy bar after a random character—rather than after himself like Mr. Hershey—doomed his name to obscurity. Once celebrated as the “candy man of the century,” he is now little known in Chicago or anywhere else. Sadder still, thanks to the quiet discontinuation of the bar in 2019, we all may have eaten our last Oh Henry! without realizing it.

Sources:

“‘Oh Henry’ Sad as Prohibition That Inspired It” – New York Herald, May 6, 1920

“Thomas F. Henry” – Arkansas City Daily Traveler, Dec 7, 1921

“Williamson Candy Company” – Official Reference Book – Press Club of Chicago, 1922

“Meeting Philadelphia Jobbers” – Confectioners Journal, Vol. 48, 1922

“The Oh Henry! Plan for Opening Up a New Territory,” by John Glossinger, Sales Management, Jan 10, 1925

“The Candy That Grew Up” – The Story of a Pantry Shelf: An Outline History of Grocery Specialties, 1925

“Cooperation in Candy Industry Speaker’s Topic” – Salt Lake Telegram, Jan 10, 1925

“Can the Minnows Compete with the Whales?” – Advertising and Selling Fortnightly, March 10, 1926

“Advertising Campaigns” – by Bernard Lichtenberg, Modern Business: A Series of Texts Prepared as Part of the Modern Business Course and Service, 1926

“Can Ridicule and Good Humor Put Imitators to Shame?” – Printer’s Ink, Sept 23, 1926

“Confectioners’ Copy Club” – Confectioners Journal, November 1926

“Handicapped Workers Get a Chance” – Decatur Herald, April 4, 1942

“The Peppermint Candy Cane Is Taking a Walk” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 25, 1943

“Perfect Timing: She’s Neither Late Nor Absent in 20 Years” – Chicago Tribune, Feb 2, 1950

“Packaging’s Hall of Fame: Oh Henry!” – Modern Packaging, April 1951

“Brandt, Baby Ruth Ad Genius, Retiring” – Chicago Tribune, April 2, 1964

“Candy Firm Sold to New York Drug Maker” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 30, 1965

“Williamson, Candy Maker, Dies at Age 79” – Chicago Tribune, Aug 9, 1967

“Col. Glossinger is Dead at 99” – Xenia Daily Gazette, July 24, 1968

“The Oh Henrys” – CandyBlog.net, June 4, 2008

Chicago’s Sweet Candy History, by Leslie Goddard, 2012

“Does John Glossinger Ring Any Bells?” – Xenia Daily Gazette, January 27, 2017

Candy: A Century of Panic and Pleasure, by Samira Kawash

On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio, by John Dunning

“Oh Henry!” – Nestle USA

Southern Migrants, Northern Exiles, by Chad Berry

My great uncle was James A Dickens he was the President of Williamson Candy.

I am in possession of his 30 years service Gold Watch.

The Watch is a 14 K Gold Hamilton Masterpiece with a gold mesh band.

I think it would be a great addition to the museum, the Family is asking $5200.00

Is there a group of Oh! Henry collectors, I can get a hold of? My wife and I may have to go into a senior living area. and I’d rather see my small but vintage Oh Henry things go to a collector. I’m afraid it may end up thrown out or in some garage sale- My Grandkids aren’t interested in that stuff

Hey Jeff how can I get in contact with you I would love to buy some of your collection fun fact I was born and raised in the same neighborhood that the original plant was located in and my name is also Henry

I remember the plant was located on the east side of ECKO prod. corp.

My husband and I still enjoy O Henry! chocolate bars, that are marked “Imported by Hershey Canada Inc.” We buy them at Walmart in British Columbia Canada.

Can you tell us where they are imported from, if they were discontinued in 2019? I remember them well at Halloween when they were sold in individual size wrappers.

Thank you,

Linda Shuflita

Do you use aluminum or silver to wrap the chocolate bar?

I worked in the Purchasing Dept at Williamson COmpany, My Purchasing Agent Boss at the time, Donald Jones and Sam Doles, were great to work for. It was a great Company, got my experience in Purchasing. At Christmas time all the employee’s got 2 pd OH Henry Bars, they were the best. God I miss that place, I worked there when i was 21 and stayed there till they sold the company. Best company to work for!

I had the pleasure to meet Mr. Williamson and Mr. Scully at the plant on Armitage sometime in 1955-’56-early ’57??…I had just lefft the USAF and was employed as an Asst Loan Manager for Personal Finance in June 1955 with an office located at 24 N PulaskiRd, Chicago…young Charles Scully joined Personal Finance and we, from time to time, would be on the streets collecting past due accounts…his parents, Mr & Mrs Charles Scully, lived in Oak Park and young Chuck and I, from time to time, would stop by and have lunch that Mrs. Scully prepared for us.

We paid a vist to the plant one day, Chuck and I, met up to say hello to his father and Mr Williamson was there as well…very nice man as I recall and I was also, for a youngster from Northern Wisconsin, being introduce to the big city, impressed to meet the President and Namesake of a company of which I was familiar with (“Oh Henry”)…I have lost track of young Chuck Scully over the years but have not forgotten that day.

Can I get any information on when Williamson Candy Co. manufactured Oh Henry chewing gum ?

I was wondering if there are any Williamson Candy Co. employment records still from the 1920’s and 1930’s? My great-grandfather worked there, supposedly in the office. I would love to know exactly when he was employed there and what his exact job was. His name was Grover Cleveland Haislip.

Please reference the Arkansas City Traveler of October 1931 where the Tom Henry Bar is both pictured and the Tom Henry of Peerless Candy is referenced in the ads. Proof that the TomHenry Bar was indeed in Arkansas City and the stories through the 20’s in that same paper also reference the popularity of the bar.