Museum Artifact: The Universal No. 134 Washboard, c. 1920s

Made By: National Washboard Co., 72 W. Adams Street, Chicago, IL [Downtown / The Loop]

Long before “upcycling” and “repurposing” became part of the antiquing lexicon, it was the washboard that practically invented re-invention—evolving from a contrivance of laborious laundering practices into a peppy and versatile musical instrument.

The artifact in our own museum collection, the National Washboard Company’s No. 134, aka “The Universal,” seems to have been particularly well suited for both business and pleasure. Stamped with a patent date of 1918 [the newspaper ad here was printed in 1920], this 26″ x 14″ board was a larger version of National’s “Zinc King No. 703″—a vintage model that folk musician David Holt has called “the Stradivarius of musical washboards.” Another washboard expert, Scott Miller of St. Louis’s Bone Dry Musical Instrument Company, has praised The Universal for its own special sonic capacity.

The artifact in our own museum collection, the National Washboard Company’s No. 134, aka “The Universal,” seems to have been particularly well suited for both business and pleasure. Stamped with a patent date of 1918 [the newspaper ad here was printed in 1920], this 26″ x 14″ board was a larger version of National’s “Zinc King No. 703″—a vintage model that folk musician David Holt has called “the Stradivarius of musical washboards.” Another washboard expert, Scott Miller of St. Louis’s Bone Dry Musical Instrument Company, has praised The Universal for its own special sonic capacity.

“The metal rub surface [on the Universal No. 134] is basically a big flat corrugated zinc-coated tin can,” Miller writes at BoneDryMusic.com. “Serious players really like that great playing surface because of the relatively soft tone and full, rich, euphonious sound it delivers. Unlike other boards that are shrill or ringy, the timbre is relatively mellow and understated (at least for a washboard). . . . The three wooden panels on the backside also form an enclosure behind the zinc rubbing surface. This creates a resonating chamber that adds tonal depth and helps drive the sound – kind of like a drum.”

Such glowing praise makes it seem like washboard designers were actually thinking about “tone” and “timbre” 100 years ago. But alas, it all appears to have been a happy accident. Back then, a washboard was merely an appliance—a simple necessity of day to day life—and one company made more of them than anybody else.

Back in the Day . . .

From the late 1800s through the 1950s, washboards could be found in just about every basement, kitchen, or makeshift laundry nook in the country. Used mostly by women working over a water basin, the boards became ubiquitous background accessories of blue-collar American home life—showcasing one’s determination (or resignation) to sweat and sacrifice for the simplest of achievements. Even when mechanical wringers and electric washing machines became more widely available in the 1920s, they weren’t viable options for most families—even less so during the subsequent Depression years. Rather than having a solution for cleaning clothes, there was a task, and a universal tool that came with it

The standard design of a wood framed washboard with a grooved metal cleaning surface (copper, brass, or zinc) was fairly unique to the United States initially, and the majority of the manufacturing wound up centered in the Midwest. The industry leader, and the maker of our Universal washboard, was technically headquartered in Chicago. But the actual power structure of the National Washboard Company is a bit more complicated than that.

[National Washboard newspaper ad from the 1920s]

[National Washboard newspaper ad from the 1920s]

A 1914 U.S. Patent office document explains the set-up like so:

“Be it known that NATIONAL WASHBOARD COMPANY, a corporation duly organized under the laws of the State of West Virginia, and located in Chicago, Cook county, State of Illinois, 1714 Commercial National Bank Building, and doing business at Saginaw, Saginaw county, State of Michigan, and at Memphis, Shelby county, State of Tennessee, has adopted for its use the trade-mark shown in the accompanying drawing, for 4; washboards, in Class 24.”

So basically, we’re dealing with a Chicago-based West Virginia corporation operating out of Michigan and Memphis. . . . Confused? Join the club, buddy.

To properly unpack this mess and figure out the true origins of the National Washboard Company, we’re pretty much on our own, as very little has ever been written about the business outside of dubious blurbs in out-of-print antique guides. Fortunately, though, after a few years of sporadic digging, I have been able to unearth three pretty clear starting points for the business, all of which correspond to the three cities most often stamped on the back of National washboards: Chicago, Memphis and Saginaw. Do bear with me as I bring the pieces together . . .

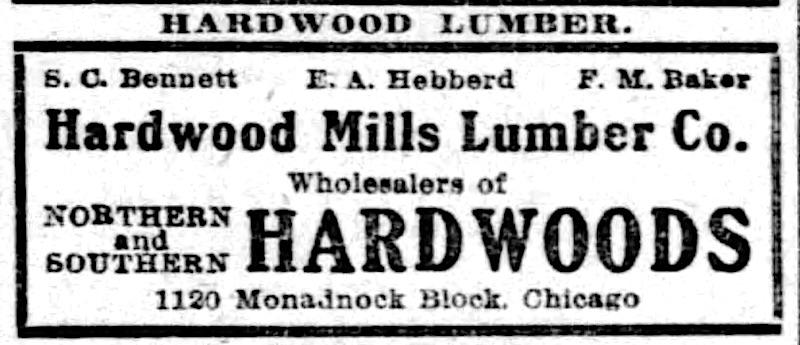

Company Origin No. 1: Hardwood Mills Lumber Co. (Chicago)

Thanks to the Chicago Tribune archives, we do at least know that the National Washboard Company was first incorporated locally in 1903, with just $5,000 in capital, by Edward A. Hebberd, S. C. Bennett, and Arthur W. Underwood. At this time, Hebberd and Bennett were also the top executives at a company called the Hardwood Mills Lumber Co., a “wholesaler of northern and southern hardwoods” headquartered in the Monadnock Building downtown. The logical conclusion, then, is that the Hardwood Mills Lumber Co. probably started distributing washboards around the turn of the century, and did well enough with them to warrant launching a subsidiary business.

Thanks to the Chicago Tribune archives, we do at least know that the National Washboard Company was first incorporated locally in 1903, with just $5,000 in capital, by Edward A. Hebberd, S. C. Bennett, and Arthur W. Underwood. At this time, Hebberd and Bennett were also the top executives at a company called the Hardwood Mills Lumber Co., a “wholesaler of northern and southern hardwoods” headquartered in the Monadnock Building downtown. The logical conclusion, then, is that the Hardwood Mills Lumber Co. probably started distributing washboards around the turn of the century, and did well enough with them to warrant launching a subsidiary business.

In the 1905 Directory of Directors in the City of Chicago, Hebberd is still listed as National Washboard’s president, with Bennett as treasurer and C. T. Brandon as secretary. The company office is also listed at the same Monadnock address as Hardwood Mills for that year, but with a separate dedicated factory space at 283 N. Green Street, employing 20 men.

Hopefully you’re not getting too attached to our lumbermen protagonists at this point, because this is essentially where they bid us adieu.

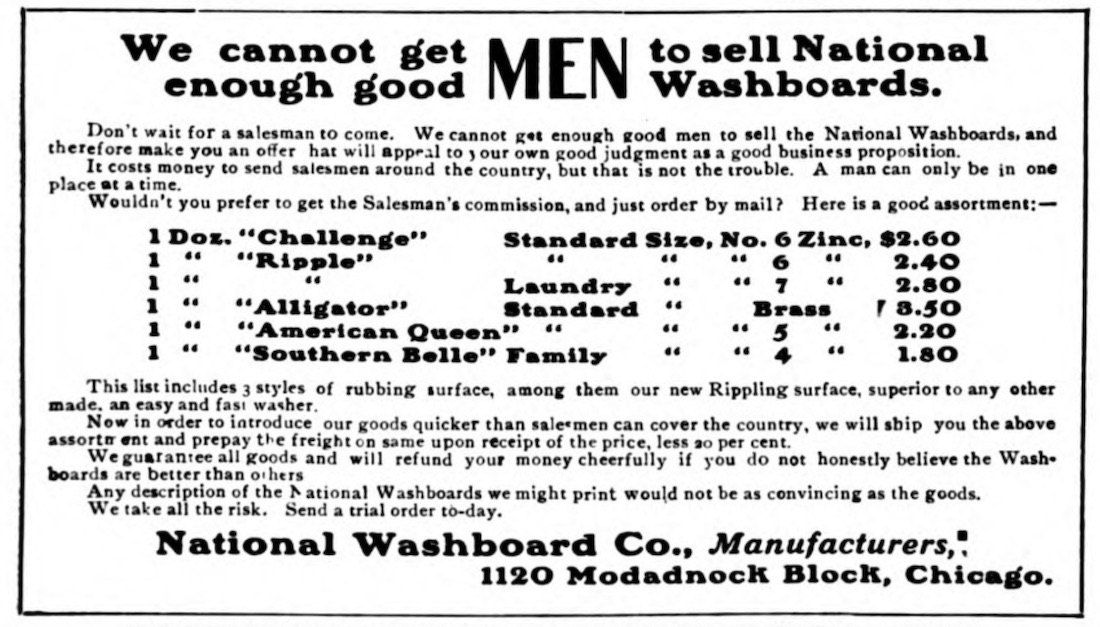

[1904 advertisement for the original National Washboard Co., offering zinc and brass models with names including “Challenge,” “Ripple,” “Alligator,” “American Queen,” and “Southern Belle.”]

[1904 advertisement for the original National Washboard Co., offering zinc and brass models with names including “Challenge,” “Ripple,” “Alligator,” “American Queen,” and “Southern Belle.”]

Within just two years, the entire power dynamic at the National Washboard Co. changed dramatically. The business got its West Virginia incorporation in 1907 along with a new set of stockholders, all of them based in Chicago: Matt B. Pittman, Walter H. Jacobs, Frank N. Burns, Edward C. Maher, and Frederick C. Hack. By 1908, the Certified List of Illinois Corporations notes a new HQ for the company (unit 1722 of the brand new Commercial Bank Building), and all new leadership in the National Washboard boardroom (or “washboardroom”): including Henry J. Gilbert, of the Saginaw MFG Co., as president, and Edward M. Kemp and William J. Donahue, both of the Wabash Screen Door Co., as VP and secretary, respectively.

Within the industry, this surprising combination of characters would have looked like quite the unholy alliance. It also turned National Washboard from a small Chicago start-up to a legitimately national organization overnight.

Company Origin No. 2: Wabash Screen Door Co. [Memphis]

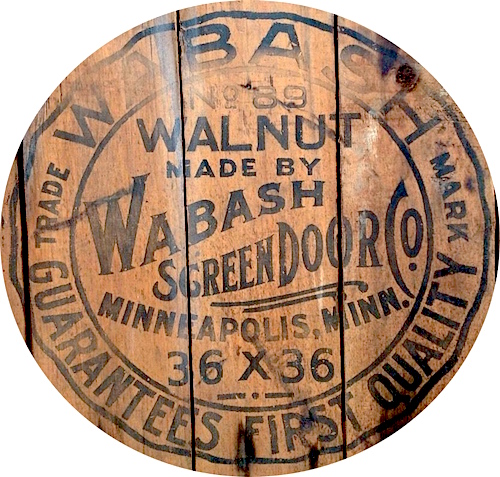

From 1907 onward, the National Washboard Company operated as a division of the Wabash Screen Door Co., aka Wabash, Inc. And while Wabash did, as you might expect, have a home office in Chicago, the company’s name wasn’t actually a reference to the famed Chicago street. Instead, it had earned its identity from the small town of Wabash, Indiana, about a three hours drive east. That’s where a 19 year-old wunderkind named Edward M. Kemp first launched his screen door manufacturing business in 1884, originally dubbing it the Wabash Wood Novelty Works.

From 1907 onward, the National Washboard Company operated as a division of the Wabash Screen Door Co., aka Wabash, Inc. And while Wabash did, as you might expect, have a home office in Chicago, the company’s name wasn’t actually a reference to the famed Chicago street. Instead, it had earned its identity from the small town of Wabash, Indiana, about a three hours drive east. That’s where a 19 year-old wunderkind named Edward M. Kemp first launched his screen door manufacturing business in 1884, originally dubbing it the Wabash Wood Novelty Works.

The company remained in Indiana until 1891, then relocated to Rhinelander, Wisconsin, where more effort was put into adding stove boards and washboards to the catalog. Kemp moved the corporate offices to Chicago in 1900, and when the Wisconsin plant burned down a year later, manufacturing was focused in two other factories: one in Minneapolis (for the doors and such), and a new facility in Memphis, Tennessee, dedicated to washboard making.

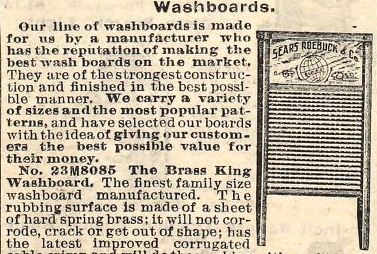

The “Wabash Chief” brand of washboards that came out of Memphis soon became big sellers through mail order companies like Sears-Roebuck, giving Kemp the capital to eventually go out and buy the National Washboard Company and other competitors.

[1904 ad for Wabash washboards of Memphis, before they acquired the National Washboard Co.]

[1904 ad for Wabash washboards of Memphis, before they acquired the National Washboard Co.]

Kemp himself did double duty as National Washboard’s vice president, working out of Chicago while ramping up his Memphis plant to keep up with growing demand. This dynamic carried on for many years, explaining why the 1920s “Universal” washboard in our collection has the cities of Memphis (where it was made) and Chicago (the sales headquarters) stamped on the back of the board.

When Kemp died unexpectedly in 1916 at the age of 51, his successors William Donahue and Harvey R. Weesner took larger leadership roles at both Wabash, Inc. and National Washboard.

From there, the Donahue family remained tightly associated with the National Washboard Co. all the way into the 1970s, with William’s son Elmer W. “Jiggs” Donahue still serving as president and heading the surviving Memphis plant during the company’s final days.

Company Origin No. 3: Saginaw MFG Co. [Saginaw]

While the museum’s “Universal” washboard only lists Chicago and Memphis on the back, a larger number of the old models also mention a third city: Saginaw, Michigan. With this third piece of the puzzle, we start to realize that the National Washboard Company really was something more like an early conglomerate, bringing together two of the largest—if not the largest—washboard manufacturers in the world.

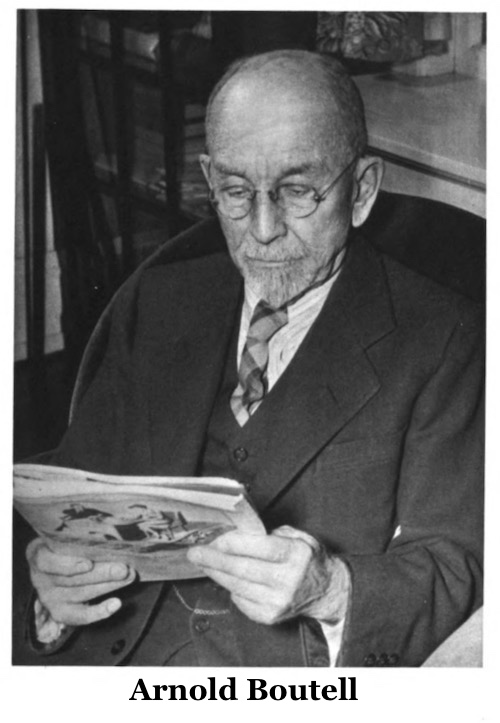

The Saginaw story centers around two men: a talented mechanical engineer from Ohio named Henry J. Gilbert (1856-1929), and a self proclaimed “man of action” and civil servant from Chicago named Arnold Boutell (1869-1947).

The Saginaw story centers around two men: a talented mechanical engineer from Ohio named Henry J. Gilbert (1856-1929), and a self proclaimed “man of action” and civil servant from Chicago named Arnold Boutell (1869-1947).

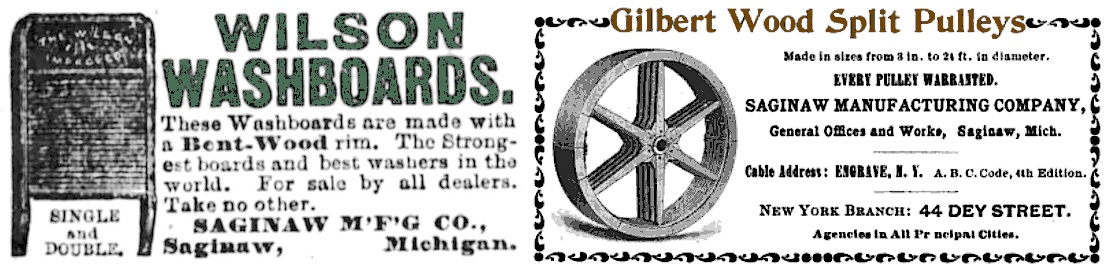

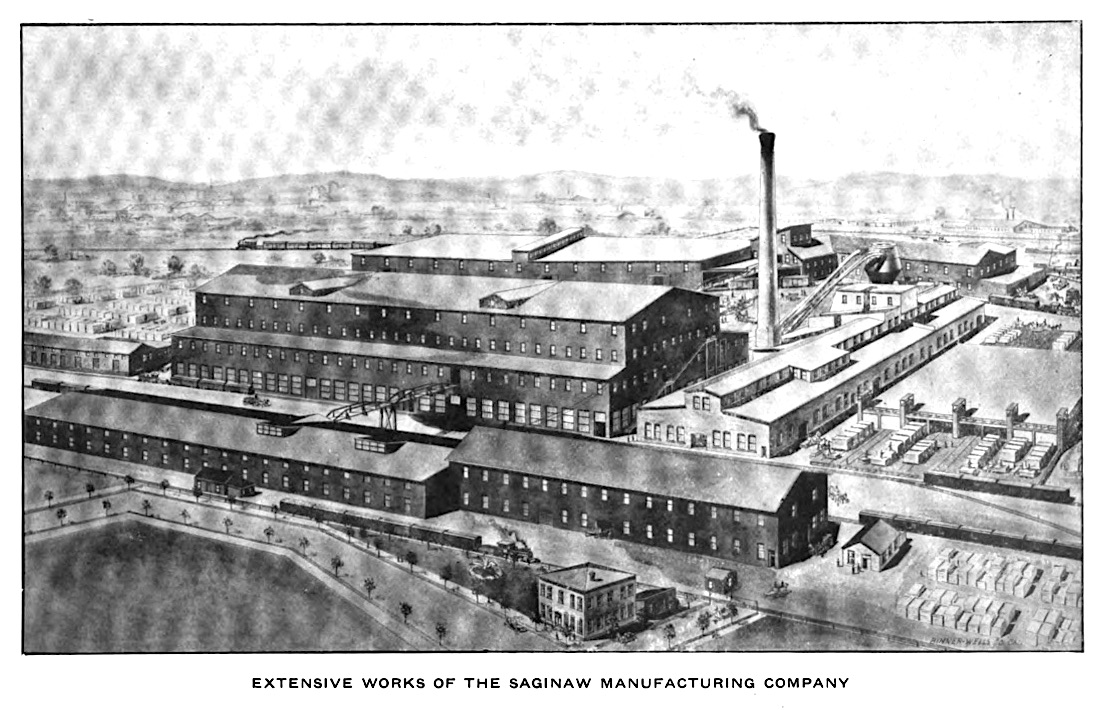

In the late 1880s, both men gained employment with the Saginaw MFG Company, a growing firm specializing in the production of barrels, boxes, step ladders, tobacco drums, and at least one patented style of zinc washboard, known as the “Wilson Washboard.” By 1892, however, it was Gilbert’s new invention, the”Gilbert Wood Split Pulley” system, that was turning much of the profit.

That year, at age 36, Gilbert’s success got him elevated to the role of VP/General Manager, and a 23 year-old Boutell—who’d made a good impression of his own as a clerk—became the secretary/treasurer. Together, Gilbert and Boutell—along with a team of 400 workers—re-focused the business for a new era, consolidating the Saginaw MFG Co’s output down to its two leading products: the pulleys and the washboards. A 40-year business partnership was underway.

[Early Saginaw MFG Co. ads feature a Wilson Washboard,1887, and Gilbert Wood Split, 1890s]

[Early Saginaw MFG Co. ads feature a Wilson Washboard,1887, and Gilbert Wood Split, 1890s]

At the turn of the century, the vast majority of new American washboards were either coming out of Gilbert and Boutell’s Saginaw Works or the Memphis factory of their rivals, the Wabash Screen Door Co. This went on for a few years until some unknown opportunist proposed a friendly new arrangement; a way to bridge the production coming out of the two plants. One can imagine Gilbert and Boutell taking the train down to Chicago and meeting with Edward Kemp and William Donahue—maybe Edward Hebberd, too—to discuss terms. Eventually, a deal was worked out . . . although I’ve yet to find a concrete document or article on the details.

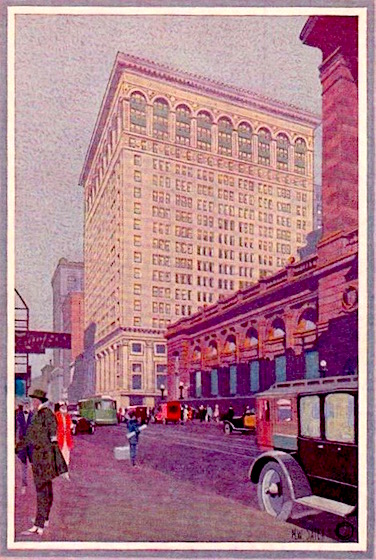

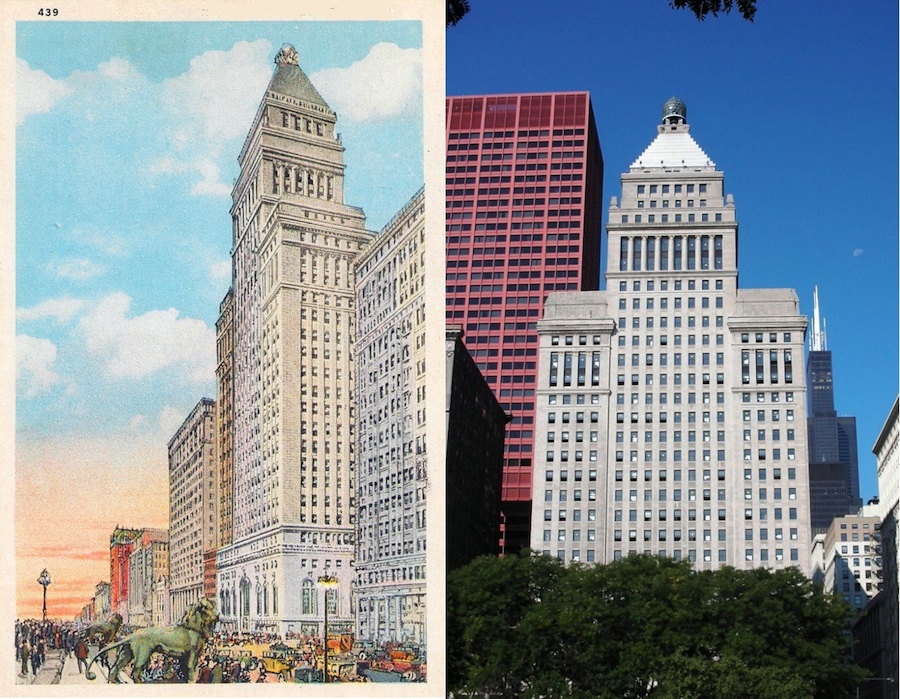

Either way, it was Chicago—the epicenter of trade—that was chosen as the perfect sales hub between Saginaw to the north and Memphis to the south. And it was the established National Washboard Company that offered a useful starting point to build from. [pictured, the original Commercial National Bank Building in Chicago, built in 1906, which became the home of National Washboard’s new HQ in 1907/08. It’s known today as the Edison Building, 72 W. Adams Street]

Either way, it was Chicago—the epicenter of trade—that was chosen as the perfect sales hub between Saginaw to the north and Memphis to the south. And it was the established National Washboard Company that offered a useful starting point to build from. [pictured, the original Commercial National Bank Building in Chicago, built in 1906, which became the home of National Washboard’s new HQ in 1907/08. It’s known today as the Edison Building, 72 W. Adams Street]

It’s hard to say whether Saginaw or Memphis had more financial sway at the time, but it was notably Henry Gilbert who was installed as the first president of the new National Washboard Company; a position he would continue to hold for more than 20 years while working remotely from his home-base in Saginaw. Boutell, meanwhile, became secretary of National Washboard after Edward Kemp’s death, and would take over the chairmanship of the Saginaw MFG Co. after Gilbert’s death in 1929 (Boutell also served on Saginaw’s city council and became something of a local celebrity).

As to whether the greater number of National washboards were being produced in Saginaw or Memphis, a 1918 book titled The History of Saginaw County, Michigan offers one, perhaps slightly biased opinion.

“In the manufacture of wash boards, this Company [Saginaw MFG Co.] is the largest producer in the world, the average daily output of various sizes being 125,000.”

That statistic sounds a bit bonkers, but one look at the factory below, as it looked in 1918, and it seems plausible.

From “Reliable” to “Regal”

So, to summarize then, the National Washboard Company was really a conglomeration of three businesses, from three cities, coming together to corner the market on America’s mail-order washboard trend. To funnel enough product to the Chicago warehouses of Sears-Roebuck and Montgomery Ward, these companies formed what we might call a “supergroup” in rock n’ roll terms—a veritable “Traveling Wilburys” of laundry scrubbing.

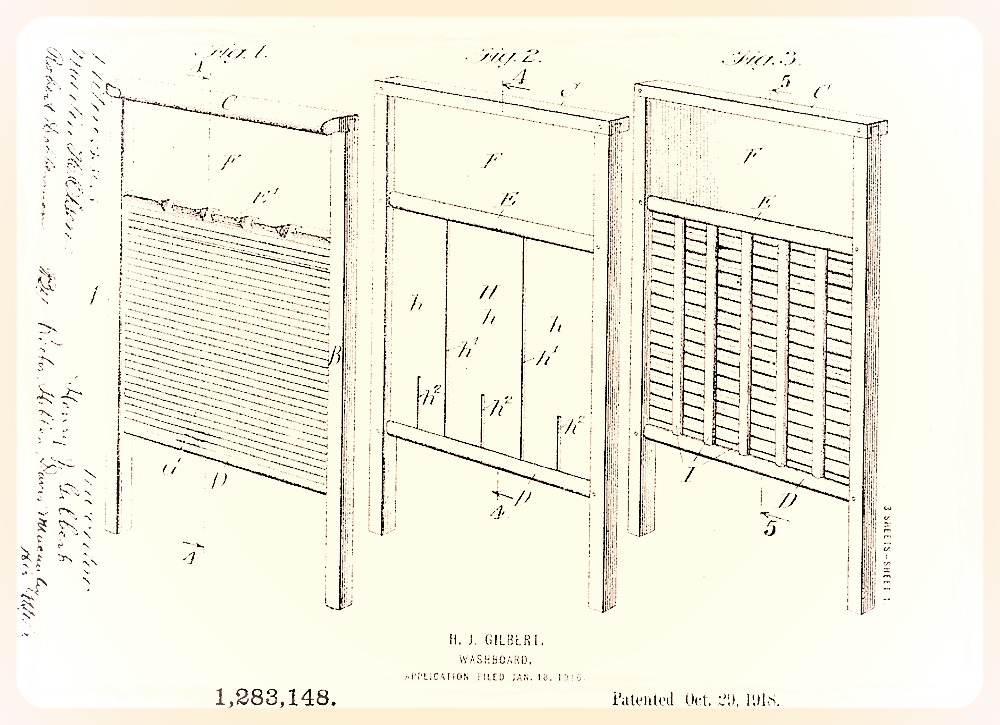

And while it’s hard to pick a single “frontman” in such instances, there seems little doubt that Henry Gilbert was the guy playing the biggest role in designing and innovating the company’s products, as there are numerous patents he collected under the National Washboard Company banner in the early 20th century (to go along with more than 50 patents he held in other fields). Gilbert’s “soap saver” washboards, in particular, were early cash cows, and though Saginaw isn’t stamped on the back of our Universal washboard, its U.S. patent number, #1,283,148, is credited to Mr. Gilbert, as well; dating back to 1918.

[Henry Gilbert’s 1918 washboard patent, the same patent noted on the Universal No. 134]

[Henry Gilbert’s 1918 washboard patent, the same patent noted on the Universal No. 134]

The years after World War I also saw the entry of Henry Gilbert’s sons, Charles T. and Harwood J. Gilbert, into leadership positions with the company. By this point, National Washboard was supposedly producing millions of boards each year. Most were just two standard sizes, small or large, but the Chicago office continued branding them with dozens of unique trademarks and logos—from “Reliable” to “Regal”—creating perhaps a false sense of competition within what was very nearly a monopolized marketplace.

Other popular NWC brands included the “Atlantic,” “Invincible,” “Junior,” “Jewel,” “The Chief,” and “the King,” to name just a handful. The artwork was fairly typical of the time period, and probably wasn’t given a great deal of concern. But decades later, all these various logos helped create a collector’s market for people attracted by the washboard’s distinctive “Americana” decor.

For the Poor

Since Chicago was no longer involved in the manufacturing end of National’s business, the company’s Windy City headquarters was always just a snazzy office space: starting with the Edison Building (72 W. Adams), then on to 111. W. Washington Street, among others. In the 1930s, they relocated to the Metropolitan Tower at 310 S. Michigan Ave, the first 30+ story building in the city. Business was good, despite the country’s economic downturn.

It’s not a sexy thing to tout about one’s business, but as one member of the Donahue family bluntly explained during another surprising sales spike in the early 1970s, “I guess there is just no decrease in the number of poor people.”

Right up to the end, the leaders of America’s washboard industry clearly saw their product as a tool of the poor—something obsolete to the middle and upper classes in the era of the washing machine, but an “old reliable” for everyone else.

[The Metropolitan Tower at 310 S. Michigan Ave, then and now; former home of National Washboard’s Chicago offices]

[The Metropolitan Tower at 310 S. Michigan Ave, then and now; former home of National Washboard’s Chicago offices]

And indeed, since washboards were the cleansing weapons of the working class, and uniquely affordable, sales only upticked during dark times (sales of electric washing machines, by contrast, were cut nearly in half in the early ’30s compared to the late ’20s). Even during World War II, when metal shortages forced the National Washboard Co. to shift from its usual metal plating to a far less agreeable glass, sales remained on course—for a while. As with anything, though, sea changes in technology will have a way of catching up to you.

In 1946, Harwood Gilbert died in in a freak hunting accident, and the next company president, Henry Mead Hammond, died from non-hunting related causes just two years later. These losses coincided roughly with the explosion of the modern American kitchen and the second wave of electric washing machines. The washboard’s transition to “old-fashioned relic” status was swift and complete.

In response, Henry Gilbert’s surviving son Charles decided to close the Saginaw Manufacturing Company’s washboard operations entirely, leaving Memphis as the company’s sole manufacturing center.

In the 1950s, all remaining Gilbert family connections to the business were severed (Charles wound up becoming a successful toy manufacturer), but the Donahues’ Memphis facility continued to produce boards under the old National brand name, utilizing a staff of just 20 workers in the 1960s to keep the business afloat. Some of their customers during these years weren’t even interested in a practical tool for cleaning their clothes anymore. A brief spike in sales came from an unlikely new clientele.

A Rhythmic Resurrection

In the midst of this yada-yada rise and fall of a laundry empire, something unexpected was indeed happening. Somewhere along the line, somebody (or more likely, somebodies) realized that the corrugated metal on a washboard doubled as a fine sounding rhythmic percussion instrument. From African roots music to Appalachian folk, Creole zydeco, and the jug band craze, performers across the country were putting their mama’s old washboards to new use, often employing thimbles, sticks, or spoons as scraping elements. Some even strapped the boards to their chests to free up their range of motion.

The washboard, symbol of the burdens of working class life, was now a sought-after medium for artistic expression. Even when it became obsolete for its original purpose, it maintained its pop culture relevance.

[Early zydeco musicians, one playing the washboard]

[Early zydeco musicians, one playing the washboard]

As more people picked up the washboard for its new purpose, inevitable assessments were made within the community, judging which of the many hundreds of styles in circulation produced the best sound and feel.

As noted, our old family-size Universal was one of the lucky models that found new life. While the majority of these vintage designs are still left collecting dust in attics, basements, and junk shops, there are musicians with discriminating taste always on the look out to salvage one.

As noted, our old family-size Universal was one of the lucky models that found new life. While the majority of these vintage designs are still left collecting dust in attics, basements, and junk shops, there are musicians with discriminating taste always on the look out to salvage one.

[Pictured: Musician Carolyn Newberger playing a National Washboard Co. board with spoons]

Maybe Henry Gilbert wasn’t thinking about cool resonance or a kickass Emmett Otter jug band jam session when he was building his first washboards 125 years ago. But then again, if he cared enough about laundry to make a tool with this sort of musical precision, who’s to say he wasn’t a great artist in his own right?

Today, there is only one original washboard manufacturing plant still in business in the United States, and the Columbus Washboard Co. in Ohio is really more of a museum than a full-fledged factory. Still, considering the millions of boards that companies like National Washboard put out into the world during its 70-year run, there won’t likely be a shortage of these things available to the poor folks, folk musicians, and vintage decor hounds who seek them. There’s probably one somewhere in your basement right now.

[Ad for National’s Brass King Washboard in a vintage Sears catalog]

[Ad for National’s Brass King Washboard in a vintage Sears catalog]

Sources:

Tuscaloosa News, Dec 26, 1971: “The Washboard a Forgotten Item”

“New Incorporations” – Chicago Tribune, December 23, 1903

Directory of Directors in the City of Chicago, 1905

‘Arnold Boutell” – Encyclopedia of American Biography, 1952

1918 Henry J. Gilbert Patent for “Washboard”

“For Better or Worse, Washboard Sales Rising” – The Tennessean, April 17, 1971

Who’s Who In Chicago, by John William Leonard, 1917

“Edward Kemp Obituary” – The American Artisan and Hardware Record: 1916, Volume 71

History of Minneapolis, Gateway to the Northwest, the S J Clarke Publishing Co, 1923

History of Saginaw County, Michigan, by James Cooke Mills, 1918

Bone Dry Music: Universal No. 134

Archived Reader Comments

“I guess my great grandparents were co-founders of this company…..my father told me their last name was Meade or Mead something like that…..my parents always had a few Chicago Washboards around the house but over the years they disappeared.” —Ryan H., 2020

“I have a NATIONAL WASHBOARD no.512. The back is faded but it reads: USE THIS WASHBOARD. MADE OF MATERIALS NOT NEEDED IN THE WAR EFFORT AND HELP WIN THE WAR” —Richard Rand, 2019

“Great story and history, I’m hooked now I have to check out more, thanks  ” —Judy, 2019

” —Judy, 2019

I have my grandma’s washboard. It is printed ” National Washboard Co. No 510 TRADE MARKS REG.U.S.PAT.OFF. MADE IN U.S.A. CHICAGO , SAGINAW, MEMPHIS . I am interested in learning where and when it was made and what the number 510 means. It is in pretty good condition. Wondering what value it would have. Thank you so much.

Hello I have a national washboard no.1

I was wondering the value of it

I have a Nation Washboard number 863. Just look for an approx yr made plz. Thank you!

I have a national washboard co. No. 116 that is solid wood and has written on the back–use this washboard made of materials not needed for defense, and help win the war. Does anyone know when this was made, and does it have any value?

I have a Federal Wash Board Jiffy F-142 from Tiffin Ohio.do you have any info on this or the company?

I have a National Washboard Co. VIM 9-7-15 National #183 Washboard, it’s

26 x 3.5 x 2.25 in size. Mostly metal as others described their washboards; but

framed in wood with a bit of a wood shelf on top. I’m reselling mine in my shop

… but love all the history you shared about the washboards and about the company…

love the Chicago history. Thanks so much!

PS. My website is dated, and needs updating, but my shop is in the Jackson Square Mall now…in LaGrange…website info does lead folks there. On IG I am @merrymemoryco.

I have a Naiad 725. Could you tell me the manufacture date range for them?

I have a washboard that says Dandy-line No 33 Manufactured by the Eastern Woodworking Corp, PHILA. 43 PENNA…I cannot find any Dandy-line washboards on line and would like more info on it. I purchased it in NJ about 30 years ago at a garage sale.

I have a 801 that has Memphis, Chicago and Saginaw in this order. It has been well used. It in fair to good condition. Would like to know how old it could be. I think my mom has it for 50 plus years, but not sure. Can you tell me how old it could be. She use to wash and iron for a living.

I worked in the Memphis plant in the 60’s I just purchased an 860 and wondered if u could share any information on it. Can u tell me when the Memphis plant closed

I have my grandmothers washboard. It is The Brass King no. 1801 made by National Washboard Company. It lists the three towns where the manufacturing plants existed. It has spent the last 70 years on an Island on West Grand Lake in Maine. I believe it was used in there house in Grand Lake Stream before it had electricity and then taken to the camp once they had power. I also have the hand run ringer she would attach to a washtub by clamps. The copper side is in perfect condition the side made for has some rust. The copper side says it is for “Use this side for heavy and coarse fabrics. Use the other side for fine and delicate fabrics”.

I have found a metal washboard number 709 any idea when it was made

I have my husbands great aunts dashboards and cannot find anything about them online. Would like to know when they were made and where I would find the value.

One is wood with glass and the verbiage says: Columbia Washboards are constructed from the best quality of the most durable materials available for best results rub lightly or heavily according to the fabric.

Second one is wood and metal and it says Little Colleen use this side of fine fabrics.

Third one is wood and glass and says National Washboard Co No 1 Trade Marks Reg. US pat.Off. Memphis, Chicago, Saginaw.

Even during World War II, when metal shortages forced the National Washboard Co. to shift from its usual metal plating to a far less agreeable glass, sales remained on course—for a while. As with anything, though, sea changes in technology will have a way of catching up to you.

What makes glass “far less agreeable”?

I found The Silver King washboard, stamped with National Washboard Co., No. 824, on

and also noted as being “Soap Saving, Sanitary, and having a Front Drain”. It is exactly

the same as the drawing by Henry Gilbert, patented 1918, shown in the above article.

The washboard was in an old shed on my husband’s family farm, near Jasper, MN.

I am sure his grandmother bought The Silver King, the largest of washboards as she

did wash for a family of eleven children. She and her husband arrived at the homestead

in 1900, October 1st. My husband’s father was born the next day, child # 6.

found an old wooden washboard with a pic of an indian chief on it #686 saginaw michigan can’t find anything about it. thanks for helping

I have a national washboard co #32. When was it made and how much is it worth

I have a national washboard # 28 can you tell me approximately the date it was manufactured?

My grandfather and father ran the company till the mid 7o’s till it closed

I have National Washboard #12 and can find no information with that number on it. Trying to find our value. Can you help me. Thanks.

I have a National Washboard No 502 “Red Star Top Notch Zinc” with the sanitary Front drain. I cannot find out any information on it. Can you help me identify it, maybe the time period for it?

I have a no.1 and I’m unable to locate one on the internet.

Hello. . . I have a 1801 board, is it unusual?

Thanks. B2

https://photos.app.goo.gl/5LrazYCRMJZkgSVh9

I just bout this one for $10.00. would love to know what time frame or year it was made.

I picked up a very old wooden and glass washboard from an estate sale Writing is hard to make out at first I thought is said RIVAL but now wondering if it says Regal Was there a board with name Rival on top and if so where was it made Writting is sooooo faded on piece Or could I be reading it wrong and it says REGAL any infor would be appreciated

lchiasson2@hotmail.com

I just was given an old washboard from a friend that is from National Washboards but it is metal on the top front and back with holes in the front. In fact the whole front is metal. The holes in the front allows the extra water to go through and down the front I guess. There is a ledge for the soap I guess right under the holes.

Do you have an age on this one or any other information on it?

I have a washboard from.national wash board company no 19. What is it worth

I have a National washboard #511. Washboard is glass. About how much are they worth??

I have a 510 Chicago, Saginaw, Memphis. What does the # mean?

I have a 801 with patent number on it. Really in good shape.

Can you tell me about it?

We have a 134. What year was it manufactured?

I have a National Washboard that has the # 815, it says invincible, and coated steel. It is 15 3/4″ High and 7 1/4″ wide. I would like to know how much it is worth. It is not in too good of shape. where it say invincible.

I have a washboard that is called Silver Beam, a White Wood Product. It states Western Washboard sales along the rim. Was this washboard made by National Washboard Company? And when?

What significance has the number on each washboard?

What do the numbers mean on the wash boards?

We have my moms washboard that says national 824 its rusted and cant find one anywhere.😔