Museum Artifact: Stereoscope w/ “World Series” Stereoview Cards c. 1905

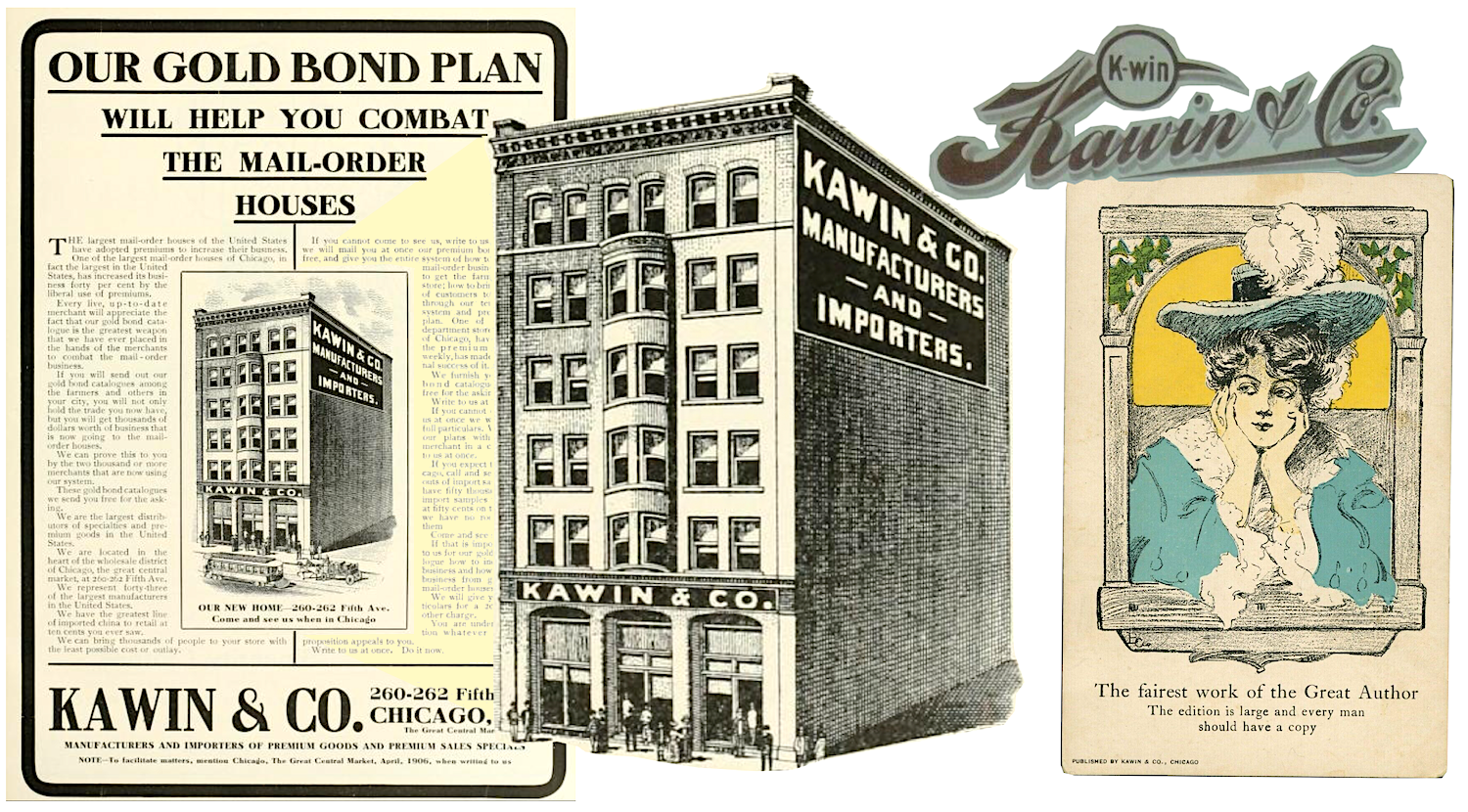

Made By: Kawin & Company, 260-262 Fifth Avenue (850 N. Wells St.), Chicago, IL [Near North Side]

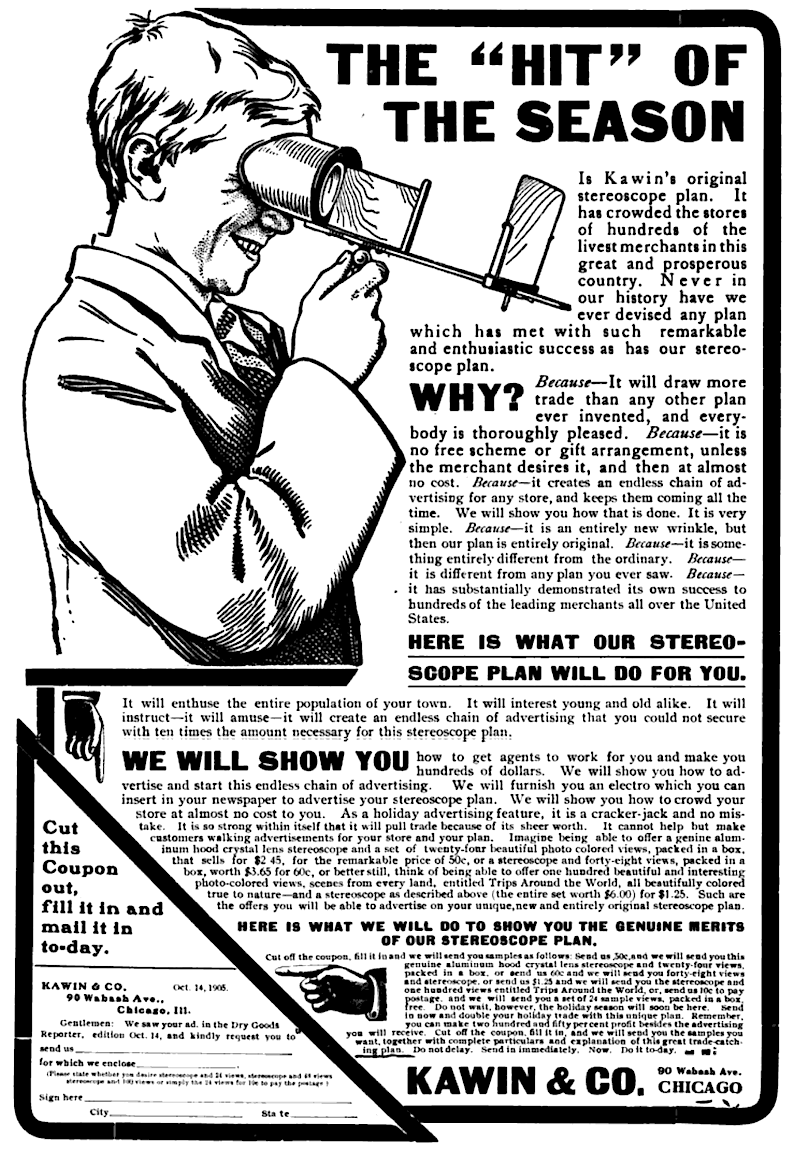

“Kawin’s original stereoscope plan has crowded the stores of hundreds of the livest merchants in this great and prosperous country . . . Send us $1.25 and we will send you this genuine aluminum hood crystal lens stereoscope and a set of one hundred beautiful and interesting photo-colored views, scenes from every land . . . It will enthuse the entire population of your town, young and old alike.” —Kawin & Co. ad in the Dry Goods Reporter, 1905

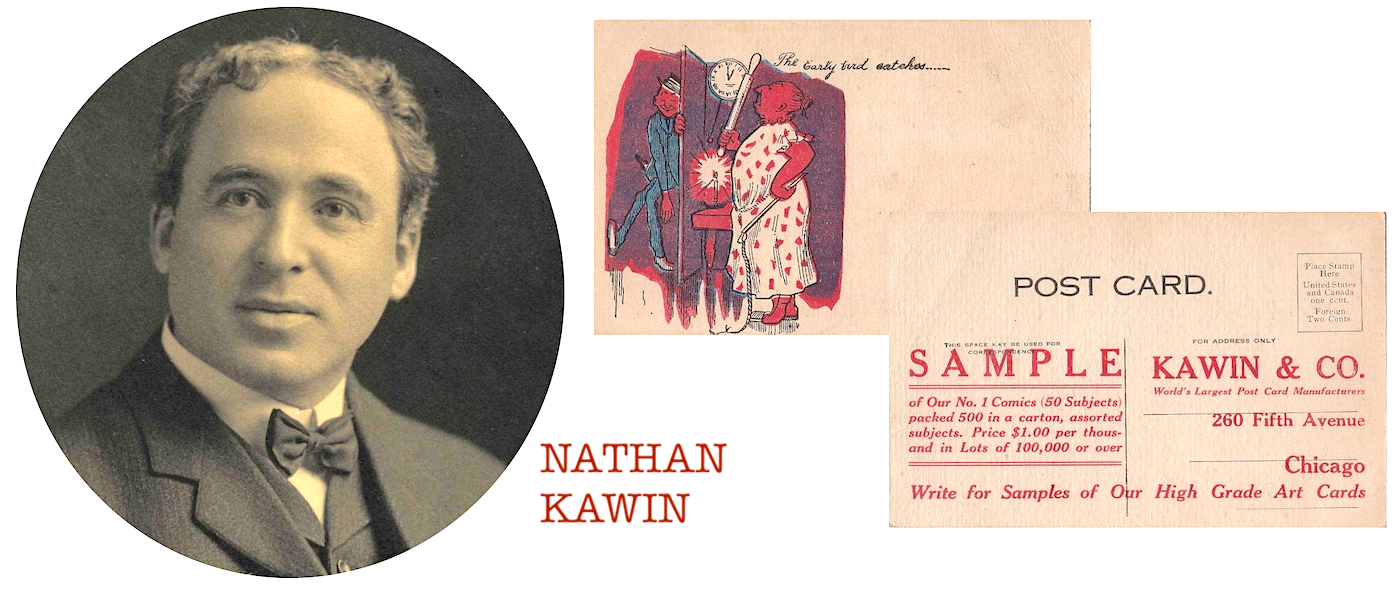

Kawin & Company existed in a crevice of early 20th century commerce that usually went unseen by the general public. The firm—presided over by Lithuanian-Jewish immigrant Nathan L. Kawin (pronounced “KAY-WIN”)—imported, warehoused, and sometimes manufactured a wide variety of “premiums,” i.e. small novelty goods designed to help retailers lure customers into making larger repeat purchases.

Kawin & Company existed in a crevice of early 20th century commerce that usually went unseen by the general public. The firm—presided over by Lithuanian-Jewish immigrant Nathan L. Kawin (pronounced “KAY-WIN”)—imported, warehoused, and sometimes manufactured a wide variety of “premiums,” i.e. small novelty goods designed to help retailers lure customers into making larger repeat purchases.

Under this business model, Kawin’s salesmen were dispersed across the country on two primary fronts: (1) finding manufacturers willing to supply premium products and (2) recruiting merchants interested in long term relationships. Both groups were promised big benefits—manufacturers got a steady nationwide distribution line, and retailers had a new way to hook shoppers into returning to their stores. The key to the premium, after all, was that it functioned like a carrot-on-a-stick for the shopper—a “free prize” they could “win” if they spent a certain amount of money at an establishment. Often, the most effective premiums were grouped into sets, such as glassware or trading cards; if a customer had collected half a set, they couldn’t help but return to the same shop in the goal of completing the collection.

There was an art to maximizing the profit potentials of these products, and Kawin’s catalog made a point of pairing its goods with a full set of matching schemes—or plans (Nathan Kawin hated the “S” word)—for cashing in.

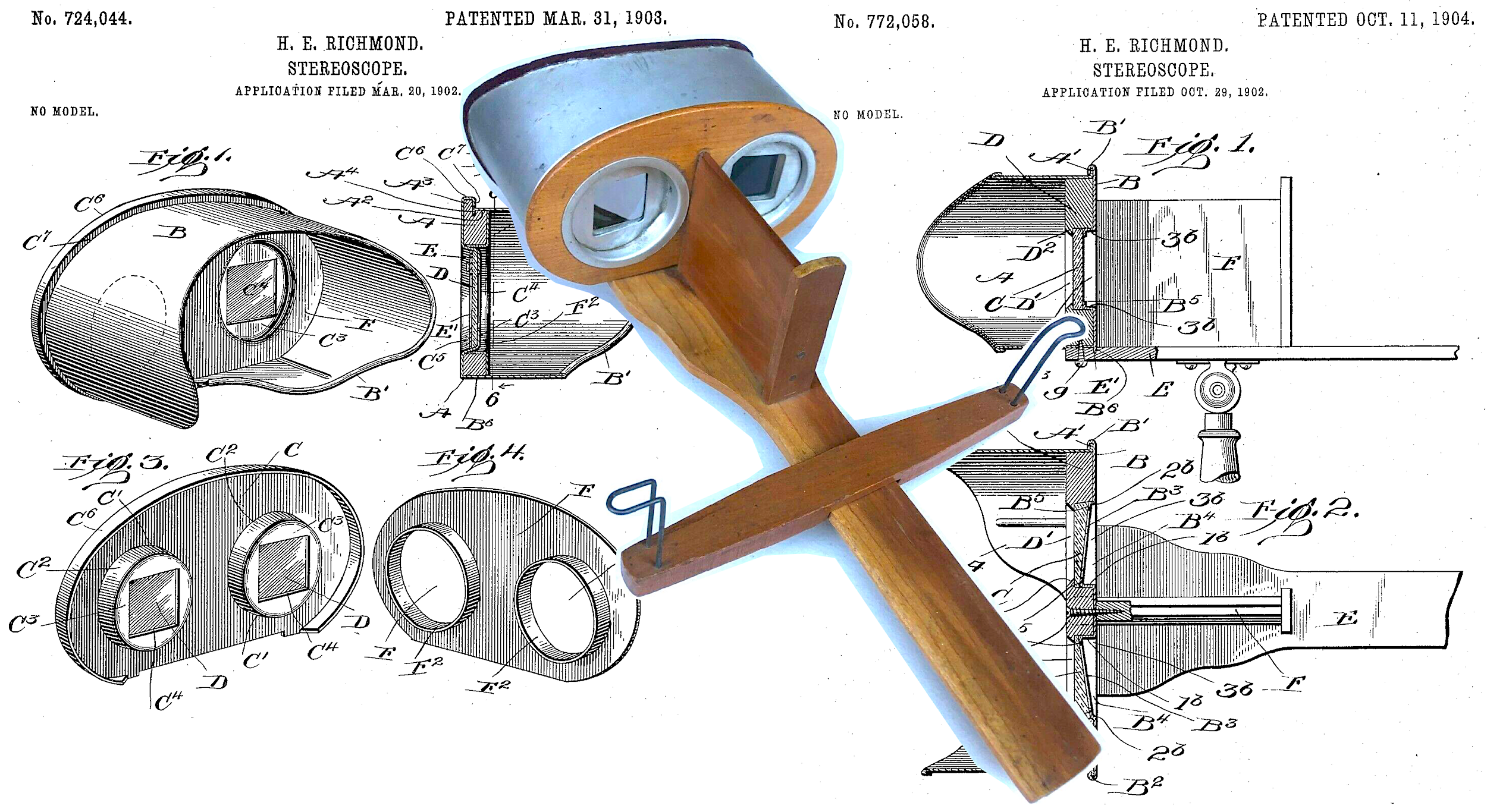

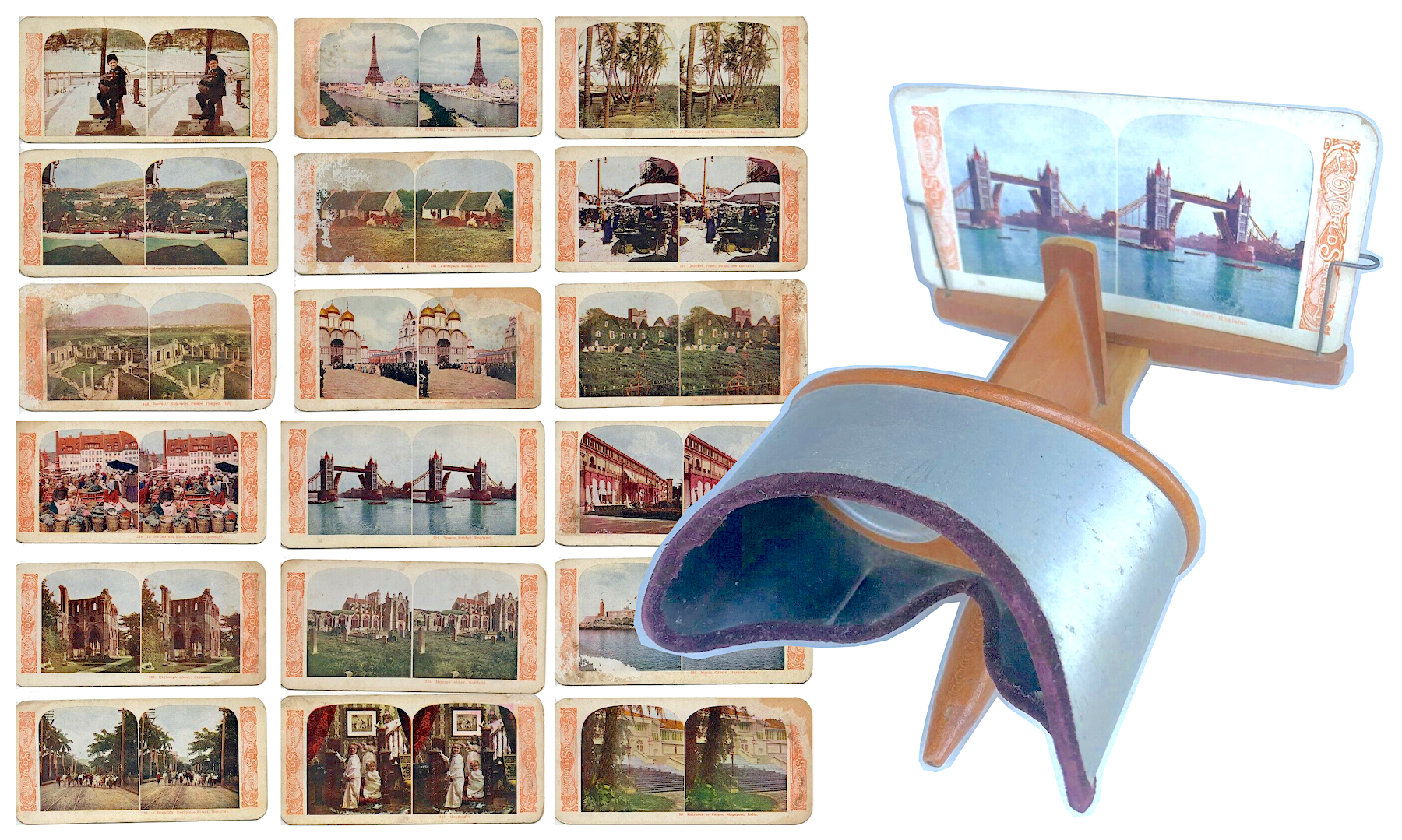

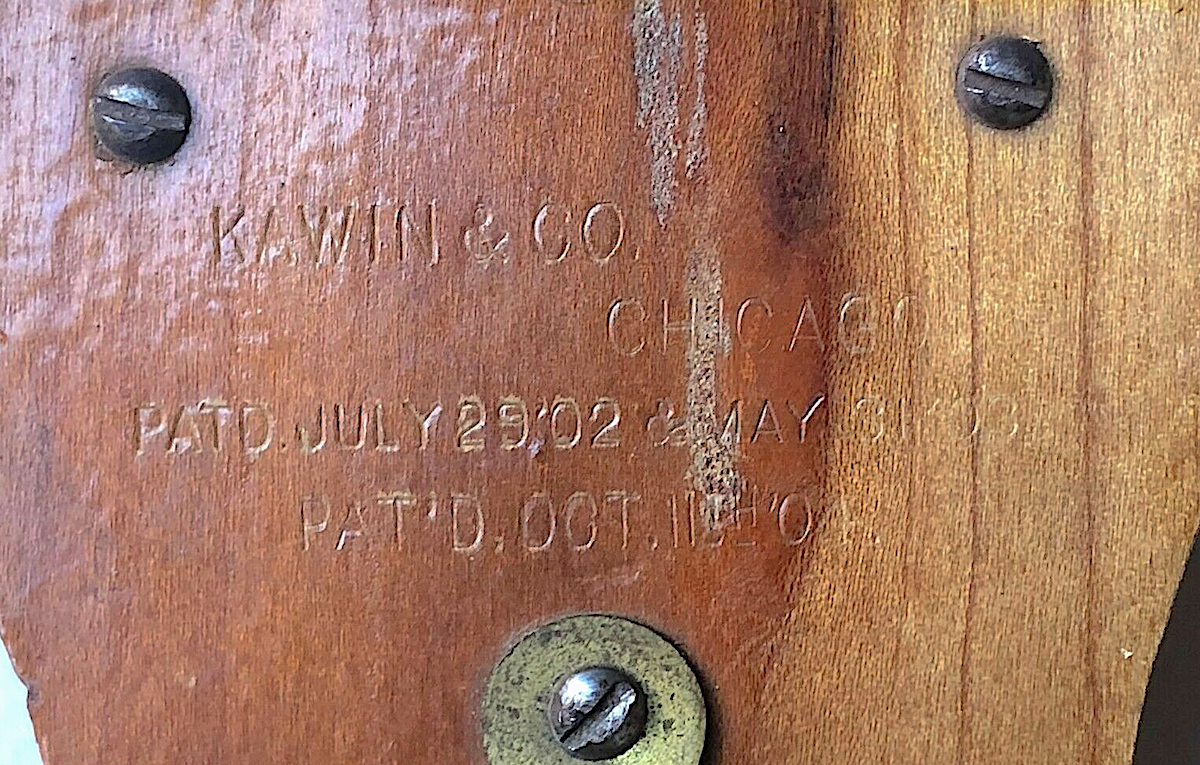

The stereoscope and accompanying stereoview cards in our museum collection provide a good example of a classic Kawin & Company premium operation. These items were almost certainly NOT manufactured in-house. Instead, the stereoscope itself is marked with a patent stamp of October 11, 1904, tying it to a design by Henry E. Richmond and the Underwood & Underwood Company of Arlington, New Jersey. Underwood was also one of the world’s leading publishers of stereograph card sets (25,000 per day in 1901), but the 1905 “World Series” set of travel cards in our collection are actually credited to another big player in the field, the H.C. White Company of New York.

[The Kawin & Co. stereoscope in our museum collection, pictured center, includes etched patent dates of 1903 and 1904, referring to the patent designs above by Henry E. Richmond, which were assigned to the firm of Underwood & Underwood, Kawin’s supplier.]

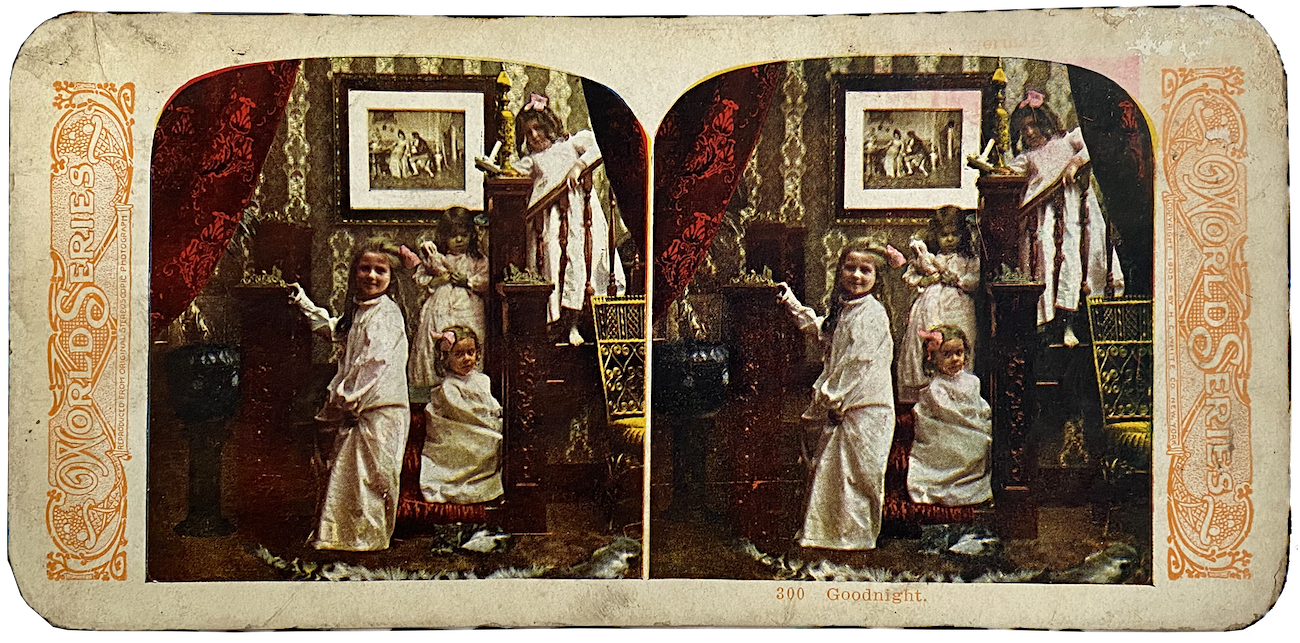

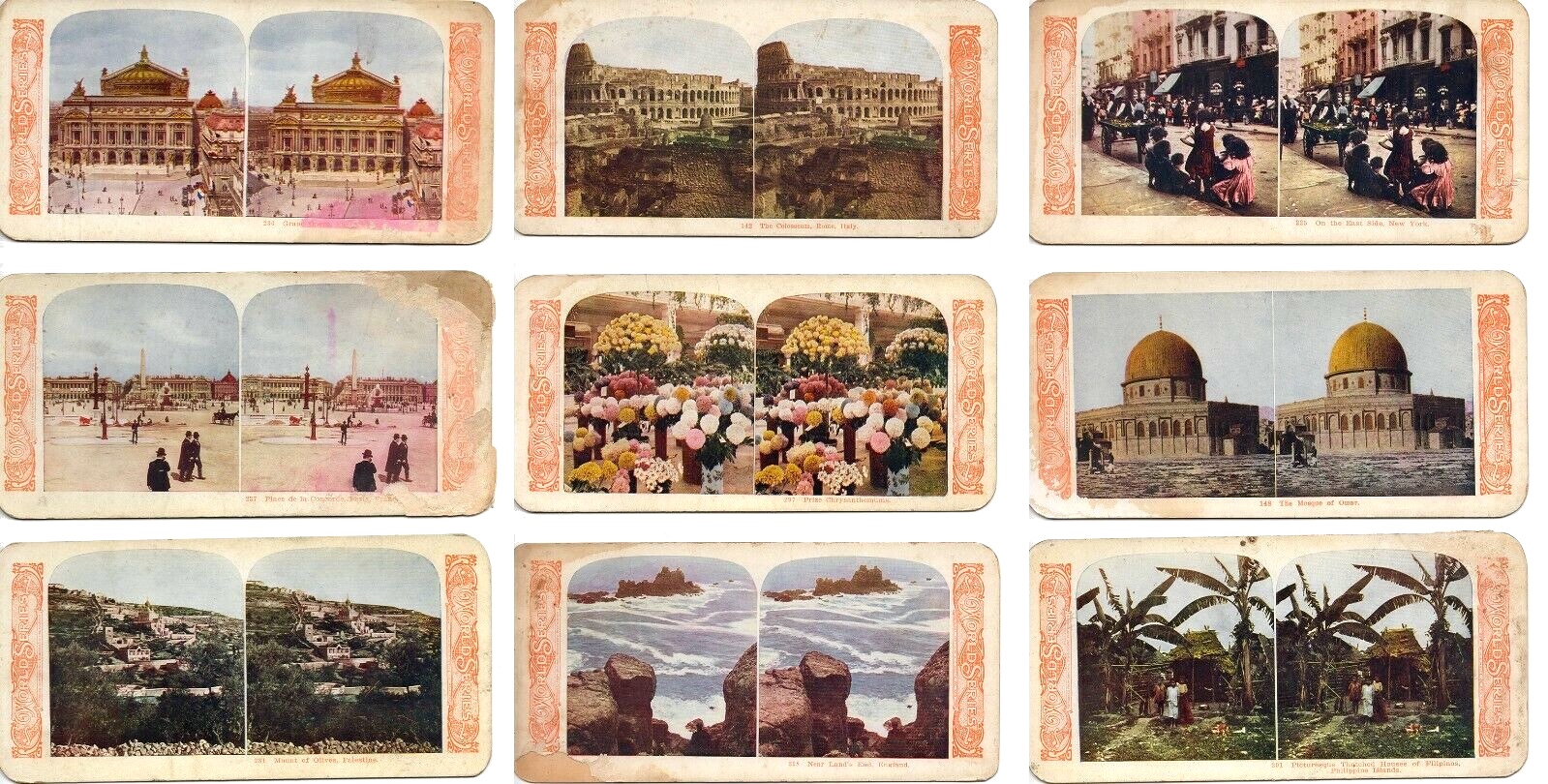

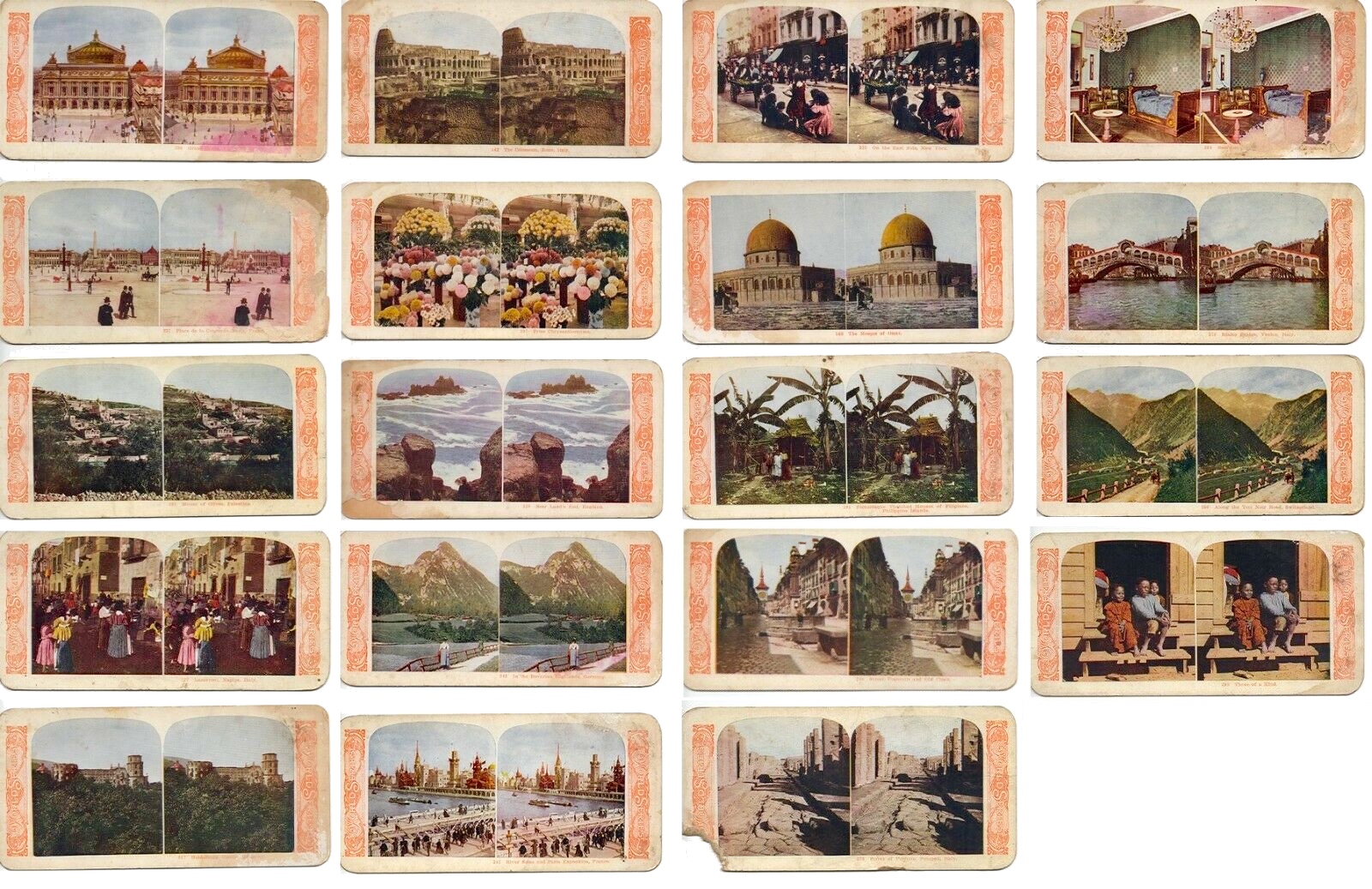

Each stereoview card features two nearly identical, side-by-side photographic images—captured from slightly different angles at slightly different moments—and printed on a thick cardboard slide. When this card is placed in the protruding display stand connected to the stereoscope viewfinder, and the user peers through the eyeholes to observe it, the effect is a sort of 3-D virtual reality experience, as the two pictures merge into a single image with an added sense of depth.

This humble special effect is still kinda cool even by today’s standards, so in a world not yet overrun with moving pictures, stereoscopes were understandably all the rage for quite a few years as the perfect parlor room distraction. There was no modern electric or motorized element to it either. The 1904 model that Kawin sold was really quite similar to designs dating all the way back to the 1860s. But thanks to wider availability through big mail order houses like Sears Roebuck and Montgomery Ward, the demand for new stereoscope sets was hitting its apex at the turn of the century.

Nathan Kawin’s novel idea was to take this already popular product and make it available directly to local independent merchants, essentially as a way to undercut the mail order behemoths that were taking over the marketplace. Rather than writing in to Sears for a new set of stereoviews, customers could go to their neighborhood shopkeeper every month and get the latest cards as a bonus just for buying their usual groceries, medicines, or cigarettes.

Nathan Kawin’s novel idea was to take this already popular product and make it available directly to local independent merchants, essentially as a way to undercut the mail order behemoths that were taking over the marketplace. Rather than writing in to Sears for a new set of stereoviews, customers could go to their neighborhood shopkeeper every month and get the latest cards as a bonus just for buying their usual groceries, medicines, or cigarettes.

“Never in our history have we ever devised any plan which has met with such remarkable and enthusiastic success as has our stereoscope plan,” read a 1905 Kawin advertisement aimed at retail merchants. “It will draw more trade than any other plan ever invented, and everybody is thoroughly pleased. . . . It creates an endless chain of advertising for any store, and keeps them coming all the time. We will show you how it is done. It is very simple.”

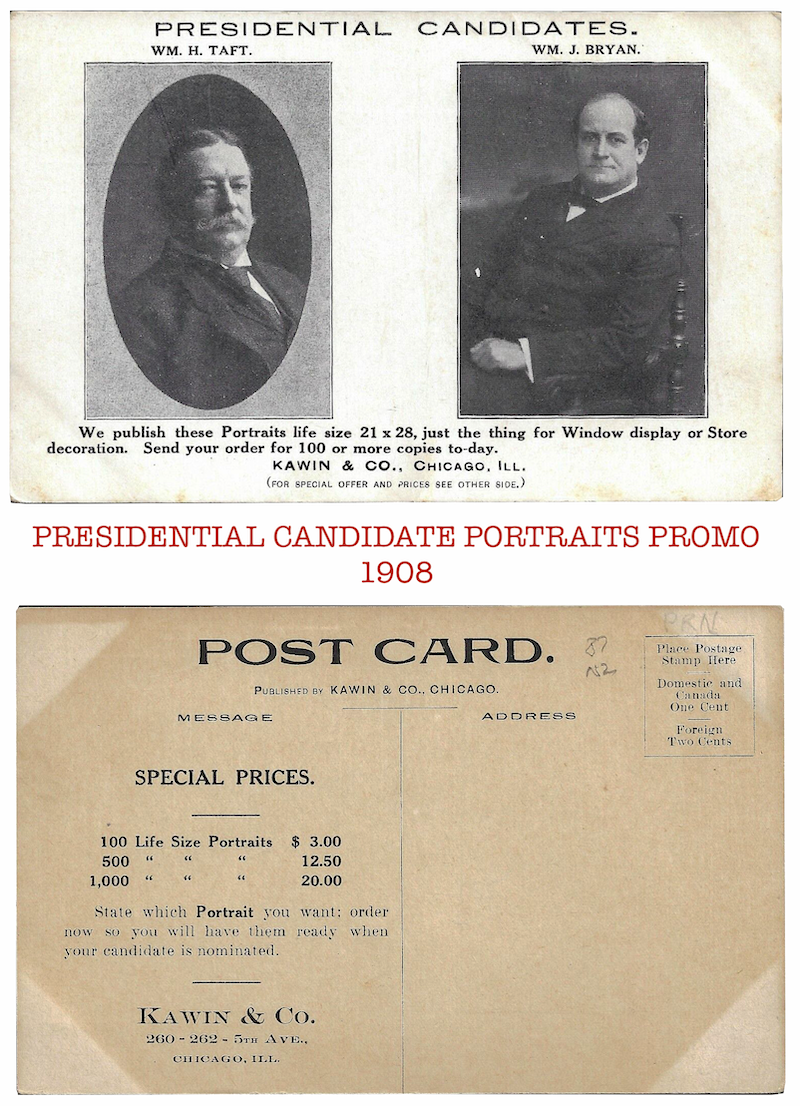

Kawin & Company promoted plenty of different products over its 30+ years in business, from chinaware to postcards, vacuum cleaners to talking machines. But the general sales message—and rampant hyperbole—were fairly consistent.

[World Series stereograph card #300, “Goodnight,” from our museum collection. Published by the H.C. White Company, 1905. Other editions of the World Series cards feature the Kawin & Co. name as publishers.]

History of Kawin & Co., Part I: The Peoria Man

As best we can tell from census records, Nathan Kawin was born in 1860 and grew up in Vilkaviškis, Lithuania—a small, primarily Jewish town that repeatedly changed hands over the course of his life, from Prussian to Polish to Russian and ultimately German control. As no coincidence, the Kawin family—hoping for stability in a faraway land—got out while the getting was good. They boarded a ship for America in 1871, when Nathan was 10, and by 1880, the family had settled in Peoria, Illinois, a fast growing western town of about 30,000 at the time.

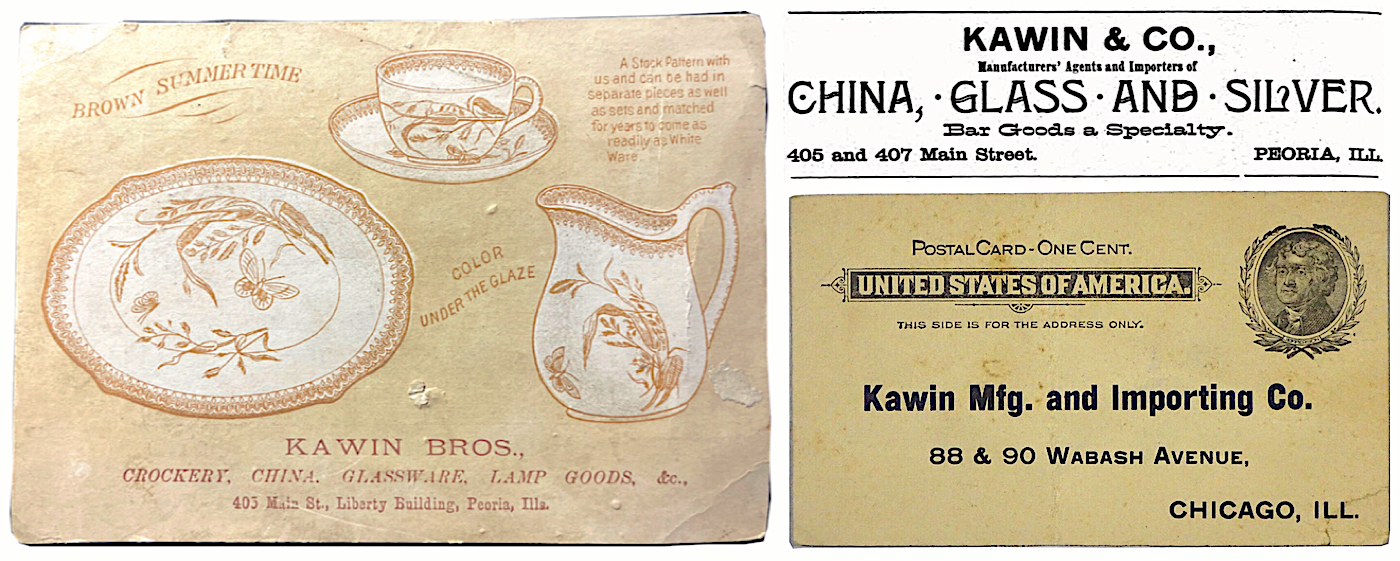

As the oldest of seven siblings, the Yiddish-speaking Nathan Kawin was determined to outdo his grocer father and find a fortune for himself and his family in America. By the age of 20, he was already operating his own business at 405 Main Street in Peoria, selling imported “china, glass, and queensware.” That business became Kawin Bros. in the mid 1880s, with younger brother Jacob on board, and “dry goods, notions, and house furnishing goods” as the trade. They described themselves in an 1885 advertisement as “The Only True Bargain House in Peoria.”

As the oldest of seven siblings, the Yiddish-speaking Nathan Kawin was determined to outdo his grocer father and find a fortune for himself and his family in America. By the age of 20, he was already operating his own business at 405 Main Street in Peoria, selling imported “china, glass, and queensware.” That business became Kawin Bros. in the mid 1880s, with younger brother Jacob on board, and “dry goods, notions, and house furnishing goods” as the trade. They described themselves in an 1885 advertisement as “The Only True Bargain House in Peoria.”

The name Kawin & Company was officially in use by 1889, with Nathan as manager, and over the next decade, more of his brothers—including Moses, Pincus, and David—worked for him as salesmen (former business partner Jacob Kawin, sadly, died in 1897 at just 34, while youngest brother Charles became a successful chemist in Chicago).

It wasn’t until around 1900, when Nathan was nearly 40, that he and his wife Lottie—two daughters in tow—finally opted for a move to Chicago themselves. The goal, it seemed, was to take the old family business to the next level.

[Left: Promotional postcard/calendar for Kawin Bros. during its Peoria era, c. 1885. Top Right: Peoria Business Directory ad, 1889. Bottom Right: 1901 ad for the Kawin MFG & Importing Co., now located at 90 Wabash Ave. in Chicago]

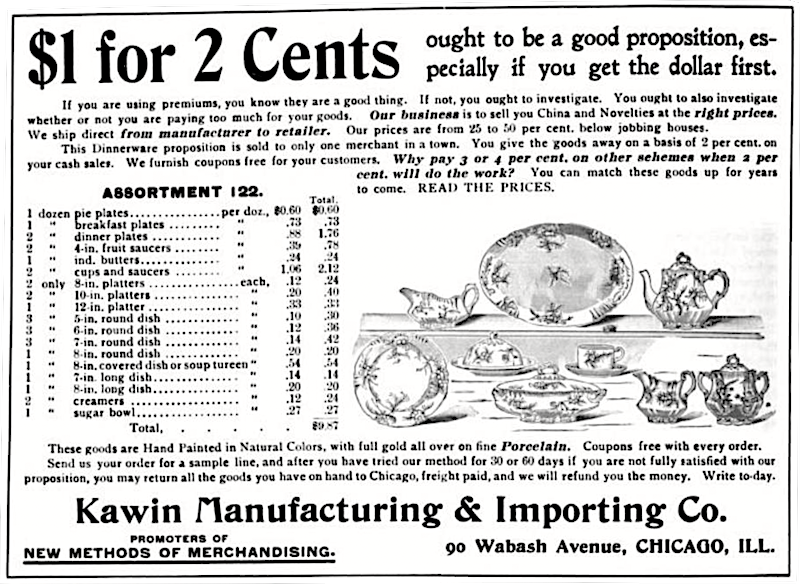

By 1901, Kawin’s big, bold premium promotion machine had kicked into gear. From an office at 90 Wabash Avenue, Nathan established the Kawin Manufacturing and Importing Company as his new venture, with 25 workers on site and many more salesmen in regular recruitment. The company’s speciality, as ever, was chinaware, in the form of dishes, saucers, cups, etc. But advertisements in 1901 are quite pointed in defining the business not merely as a wholesale house, but as “promoters of new methods of merchandising.”

“If you are using premiums, you know they are a good thing,” claimed an ad in the Dry Goods Reporter. “If not, you ought to investigate.”

Another early ad, promoting a $5 dinner set offered to merchants at half that price, takes a uniquely conversational tone.

“This may seem strange,” it reads, “but we can prove it if you will send us a sample order. We consider this dinner set the best value that ever was offered to the trade. It will retail at $5.00, but if you want a little excitement in your store, advertise it for $3.95. You will have more people call on you for this article than anything else you ever had in your store and at the same time you will be making a fair margin.”

“This may seem strange,” it reads, “but we can prove it if you will send us a sample order. We consider this dinner set the best value that ever was offered to the trade. It will retail at $5.00, but if you want a little excitement in your store, advertise it for $3.95. You will have more people call on you for this article than anything else you ever had in your store and at the same time you will be making a fair margin.”

Sometimes, Kawin’s copywriters seem unable to control their enthusiasm, referring to their premium deals as “The Greatest Advertising Proposition Ever Placed Before American People.” Plenty of merchants understandably rolled their eyes, but others believed the hype.

In a 1906 advertisement, the re-re-named Kawin & Company now claimed to have more than 2,000 merchants partnering with them, as well as 43 manufacturers. Their shared enemies were the mail order houses—led by Sears and Ward’s—which had already used premiums, in part, to build their own merchandising empires. By this point, Kawin & Co. had its own dedicated building at 260-262 Fifth Avenue (roughly 850 N. Wells St. in today’s street numbering), and promoted itself as “the largest distributors of specialties and premium goods in the United States.”

Those specialties had now gone beyond china and glassware into other trendier novelties, including calendars, postcards, and a little piece of magic called the stereoscope.

[Left: 1906 ad featuring a sketch of Kawin & Co.’s new building at 260-262 Fifth Avenue, what would now be approx. 850 N. Wells Street. Right: Kawin postcard, c. 1906]

II. The Premium Man

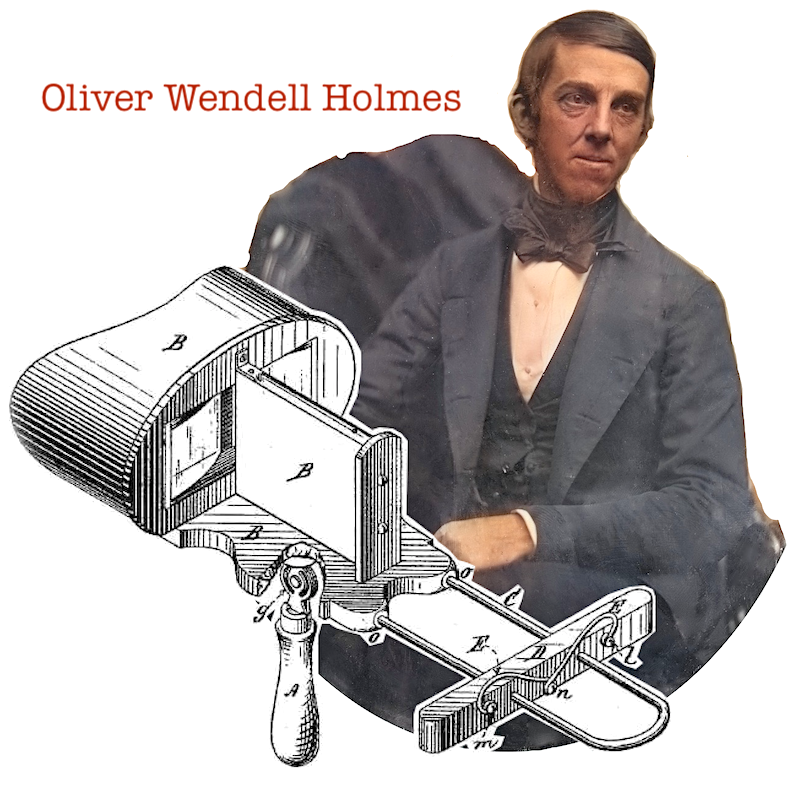

One of the early champions of the handheld stereoscope in America was the famed poet, physician, and overall brainiac Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. In 1859, Holmes made some improvements on the technology and introduced the style of American stereoscope that would remain in popular use for the next 50 years. Rather than patenting this invention, he also made it freely available to all manufacturers, believing it was for the greater good. As he would explain in an essay published that year in The Atlantic, Holmes saw the stereoscope as a world-changing instrument; one that would render all real-life landmarks obsolete once they could all be visited virtually.

“Form is henceforth divorced from matter,” he wrote. “In fact, matter as a visible object is of no great use any longer, except as the mould on which form is shaped. Give us a few negatives of a thing worth seeing, taken from different points of view, and that is all we want of it. . . . Matter in large masses must always be fixed and dear; form is cheap and transportable. We have got the fruit of creation now, and need not trouble ourselves with the core. Every conceivable object of Nature and Art will soon scale off its surface for us. Men will hunt all curious, beautiful, grand objects, as they hunt the cattle in South America, for their skins, and leave the carcasses as of little worth.”

“Form is henceforth divorced from matter,” he wrote. “In fact, matter as a visible object is of no great use any longer, except as the mould on which form is shaped. Give us a few negatives of a thing worth seeing, taken from different points of view, and that is all we want of it. . . . Matter in large masses must always be fixed and dear; form is cheap and transportable. We have got the fruit of creation now, and need not trouble ourselves with the core. Every conceivable object of Nature and Art will soon scale off its surface for us. Men will hunt all curious, beautiful, grand objects, as they hunt the cattle in South America, for their skins, and leave the carcasses as of little worth.”

Holmes was at least partially right. Photography—whether for the purpose of stereographs, postcards, or, eventually, motion pictures—would send many men to the ends of the earth and give many more men an excuse for staying at home. From a 21st century perspective, though, it’s difficult to grasp just how awestruck the Victorians would have been with something as seemingly “basic” as a postcard on a stick.

It wasn’t a short-lived fad, either. Over 40 years after Holmes’ article, in 1905, Kawin & Co. arranged a deal with Underwood & Underwood to start distributing their stereoscopes and stereoview cards as premiums. The Holmes-style viewfinder had already been included in Sears catalogs to great success, so this was more of a catch-up strategy than a visionary one, no pun intended.

While Kawin ads of this period would briefly mention the appealing qualities of the stereoscope itself, and the ability to see great sites of the world as if you were there, the greater focus was on explaining the selling strategy to the merchants of America.

“Our stereoscope plan is so strong within itself that it will pull trade because of its sheer worth. It cannot help but make customers walking advertisements for your store and your plan,” one ad read.

“Our stereoscope plan is so strong within itself that it will pull trade because of its sheer worth. It cannot help but make customers walking advertisements for your store and your plan,” one ad read.

“Write to us at once,” read another, “and we will mail you at once our premium bond catalogue free, and give you the entire system of how to combat the mail-order business, and how to get the farmers to your store; how to bring thousands of customers to your store through our premium sales plan.”

The word “PLAN” was a favorite of Nathan Kawin, even if other less appealing nouns were often used by critics.

“A trade plan is not a ‘scheme,’ so to speak,” Kawin personally protested in a 1906 interview with Glass and Pottery World magazine (in a segment titled, “Kawin, the Premium Man”).

“A scheme is a definite outlined way in which a man or party may be hoodwinked or induced through some means or other to buy or take that which he does not want. In other words, the inducement is so attractive that the buyer loses all sight of the goods he is getting. I never attempt to do any business with merchants who do not sell good goods to their trade. . . . I like to make acquaintances with prosperous dealers who command the respect of their community and who are prospering through the good qualities of the merchandise they sell.”

From Kawin’s point of view, his company’s role was to help one upstanding merchant get a leg up on his equally upstanding competitors. That’s where the inducement of the premium came in. “Offer a certain class of customer something worthwhile, something to make it an object for them to trade at your store, and you have their trade.”

Nathan Kawin seemed more than proud to be a spokesman not just for his own company, but for the entire premium industry.

“The prosperous merchant,” he said, “is that merchant who hustles in every way to get the biggest trade in his community. People used to raise objections to premiums and plans for inducing trade. Probably they had a right in those days, but the times have changed now, and merchants hold their trade by giving reliable merchandise and doing everything in their power to keep an aroused interest in their store.”

Sometimes, in Kawin’s own effort to “hustle” for business, he got himself in hot water. In a particularly extreme case in 1908, he was arrested after Chicago police confiscated more than 500,000 “improper” postcards and stereoviews from the Fifth Avenue offices. Kawin was eventually acquitted after explaining that he’d acquired 2.5 million cards from a bankrupt competitor and had no idea so many of them included “questionable” content (presumably scantily clad ladies). True or not, the jury bought it.

Later that year, Kawin & Company was officially incorporated at a capital stock of $50,000. Joining Nathan as incorporators were his brother Pincus Kawin and an attorney, Ernest Kusswurm.

Later that year, Kawin & Company was officially incorporated at a capital stock of $50,000. Joining Nathan as incorporators were his brother Pincus Kawin and an attorney, Ernest Kusswurm.

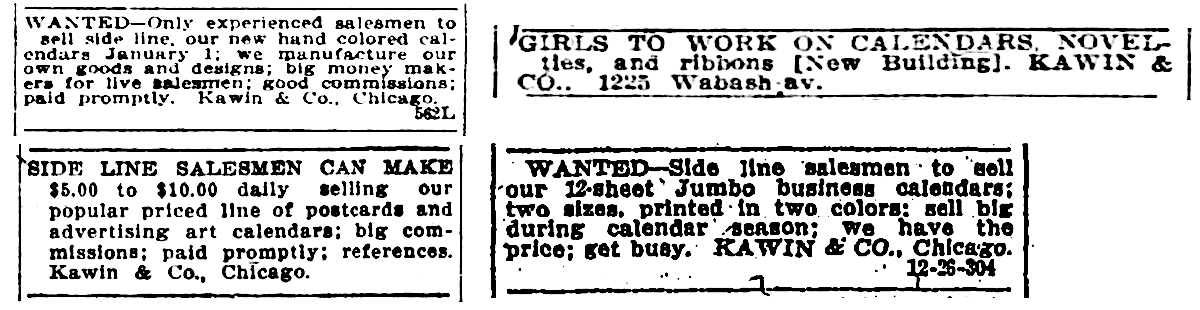

The company moved to a factory space at 1225 S. Wabash Avenue by 1910; losing its dedicated building suggests a possible slow down in business. In 1911, they were hit with a lawsuit by their biggest postcard supplier, the American Colortype Company, for allegedly failing to pay for a massive shipment of Christmas cards that Kawin claimed had been delivered too close to the holiday.

Kawin might have been snakebit by that incident. In newspaper ads seeking factory workers in 1913, the company now claimed to “manufacture our own goods and designs,” led by a line of “hand colored calendars.”

The DIY strategy might have been better for avoiding lawsuits and indecency arrests, but it wasn’t so great for keeping the warehouse stocked. With competition extremely fierce on all fronts, Kawin & Company stumbled through the mid 1910s and were unceremoniously swept off the map by the end of World War I.

[“Wanted” ads like these ran in regional newspapers across the U.S. in the early to mid 1910s, as Kawin & Co. focused on selling its postcards and advertising calendars. The 1911 ad at the top right is seeking girls to work in the Chicago factory at its new location, 1225 Wabash Avenue]

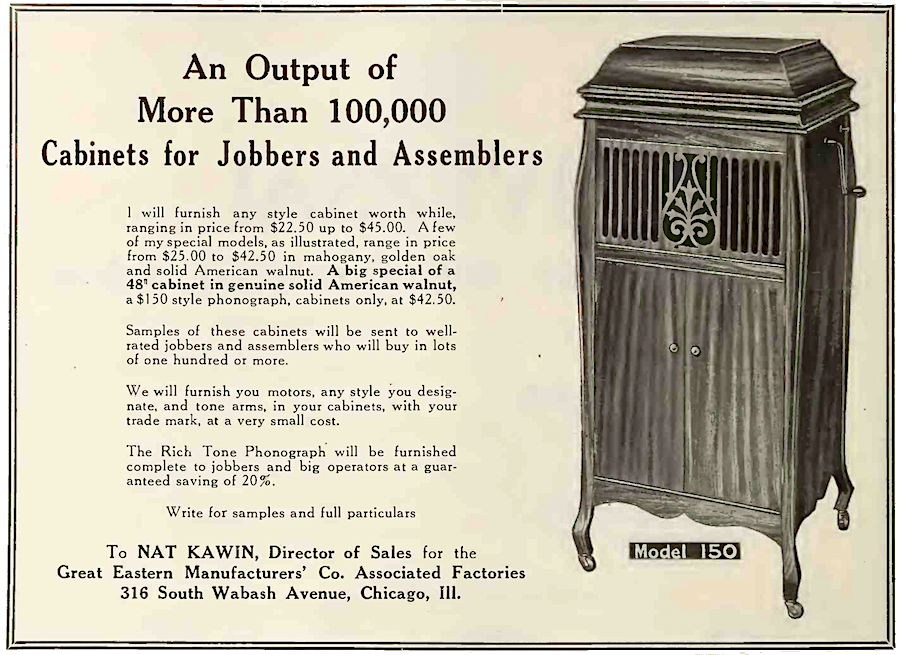

III. The Phonograph Man

Despite these setbacks, Nathan Kawin—ever observant of the new trends—wasn’t interested in an early retirement. In 1917, just shy of his 60th birthday, he became a shareholder in the Great Eastern Phonograph Company of New York (aka the Great Eastern Manufacturers Co.) along with a partner, Samuel Lanski. He also purchased the Firestone Phonograph Co., an upstart Chicago manufacturer. From an office at 316 S. Wabash Ave., Kawin tried to get his talking machine business off the ground over the next few years.

“My factories make the three biggest value cabinet phonographs,” he claimed in a tiny 1920 newspaper blurb, which identified himself as “NAT KAWIN, The Phonograph Man.”

“My factories make the three biggest value cabinet phonographs,” he claimed in a tiny 1920 newspaper blurb, which identified himself as “NAT KAWIN, The Phonograph Man.”

“I will furnish any style cabinet worth while,” read another 1920 ad in the Talking Machine World. “Samples of these cabinets will be sent to well-rated jobbers and assemblers who will buy in lots of one hundred or more.”

Nathan Kawin was correct about the phonograph boom of the ‘20s; he and Lanski just didn’t have the resources to compete with the hundreds of other companies jumping into the marketplace. Great Eastern went bankrupt by July of 1921.

Nathan continued working in advertising into his later years, and died in 1935 at the age of 74. He and his wife Lottie had two daughters who went on to successful careers as independent, unmarried women; Irene Kawin was a social worker who became Cook County’s chief deputy probation officer, while Ethel Kawin graduated from the University of Chicago and established herself as a leading child psychologist. Charles Kawin, one of Nathan’s younger brothers, also enjoyed considerable success as an industrial chemist and foundry consultant, presiding over the Charles C. Kawin Company for nearly 50 years up until his death in 1957.

Sources:

“The Stereoscope and the Stereograph,” by Oliver Wendell Holmes – The Atlantic, June 1859

“Kawin, the Premium Man” – Glass and Pottery World, July 1906

“Nathan Kawin Arraigned for Holding Improper Cards” – Chicago Tribune, Jan 22, 1908

“Owner Free: Destroy Cards – Nathan Kawin Acquitted” – Chicago Tribune, Feb 16, 1908

“New Incorporations” – Chicago Tribune, Feb 22, 1908

“Kawin & Co. vs American Colortype Co.” – Circuit Court of Appeals, 7th Circuit, April 10, 1917

“Nat Kawin Buys the Firestone Co.” – The Music Trades, Aug 9, 1919

“Nat Kawin, The Phonograph Man” – The Commercial Appeal, Dec 12, 1920

“Edwin D. Buell, Trustee of Great Eastern Manufacturers Company, Bankrupt, Appellee, v. Samuel Lanski and Nathan Kawin, Appellants” – Appellate Courts of Illinois, March 1924

“Nathan Kawin” [obit] – Chicago Tribune, May 30, 1935

“A Ring Find with a Twist” – TheRingfinders.com

I came across two of these view finder’s and I have hundreds of cards to go with them. My question is where should I post them for sale and at what price? They both are in great shape as well are the he cards. I have no desire to hold on to these. Thank you, Heath