Museum Artifact: “Little Giant” Ratcheting Screw Jack, c. 1917

Made By: William E. Pratt Manufacturing Co., 35 W. Lake St., & 190 N. State St., Chicago, IL [Downtown / The Loop], Foundry in Joliet, IL

On the great Venn diagram of Chicago industry, at the sliver-sized intersection of Model T Fords, decoy ducks, and the atomic bomb, you can find the unique domain of the Wm. E. Pratt MFG Co.

The artifact in our museum collection, a World War I era “Little Giant” screw jack, was introduced about 20 years after the company was founded, and represents Pratt’s best effort yet to make a name for itself in the booming automotive industry. Their focus wasn’t exclusively on car jacks at the time, but it was certainly a good genre to break into. After all, if there was one thing you could count on in the early days of the automobile, it was breakdowns and accidents—busted axles, shredded tires, smoke billowing from one place or another. Nobody knew what they were doing, and everybody needed a capable, portable jack.

The artifact in our museum collection, a World War I era “Little Giant” screw jack, was introduced about 20 years after the company was founded, and represents Pratt’s best effort yet to make a name for itself in the booming automotive industry. Their focus wasn’t exclusively on car jacks at the time, but it was certainly a good genre to break into. After all, if there was one thing you could count on in the early days of the automobile, it was breakdowns and accidents—busted axles, shredded tires, smoke billowing from one place or another. Nobody knew what they were doing, and everybody needed a capable, portable jack.

In 1915, my favorite magazine, The Horseless Age, described the arrival of the new “Little Giant.”

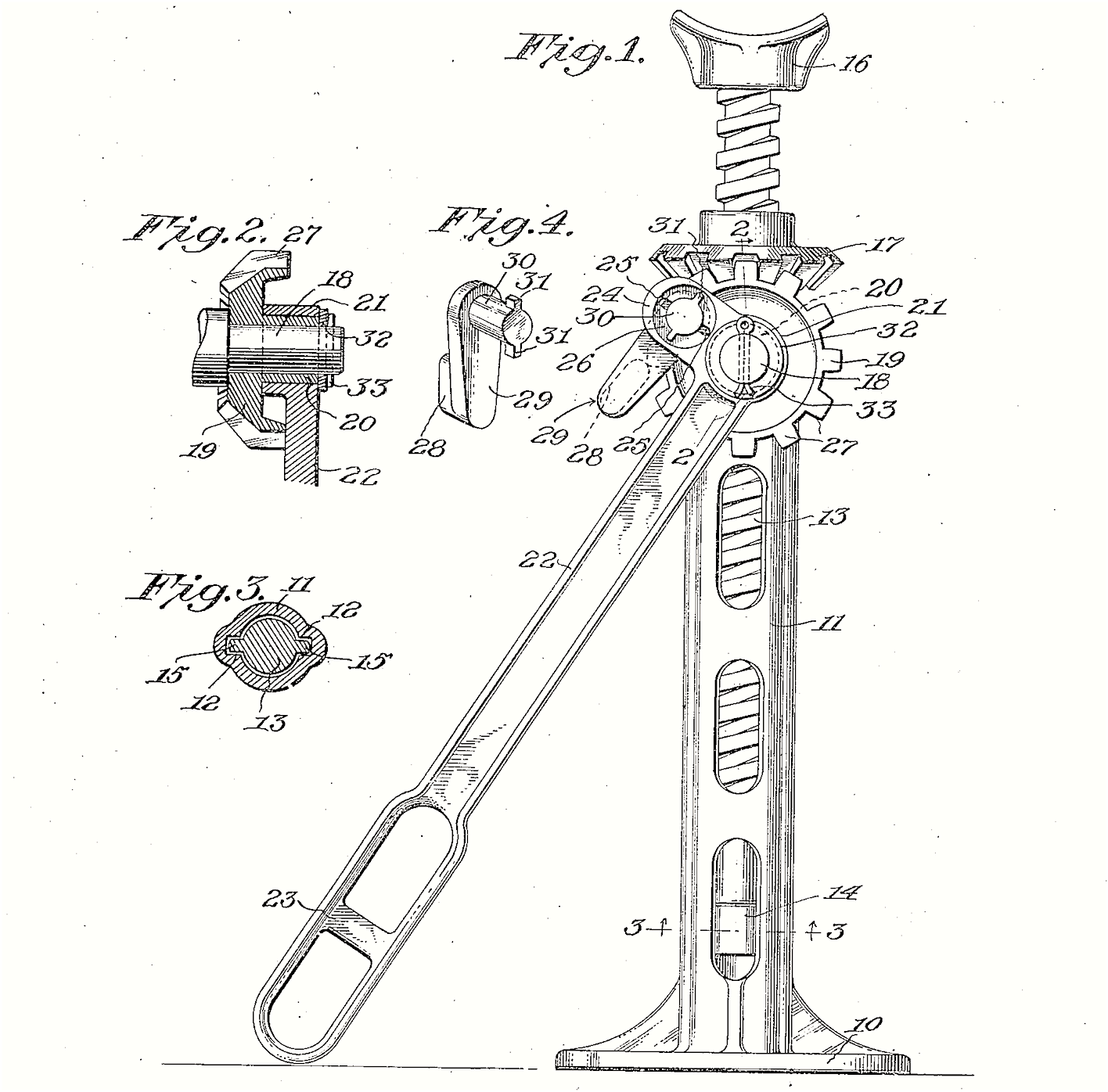

“William E. Pratt MFG Co., 35 West Lake street, Chicago, Ill., has brought out a quick-acting screw jack, which is made of malleable iron and a cut thread steel screw, requiring only a single turn of the pawl to raise or lower. This jack has a raise of six inches, weighs four pounds and is listed at $1.00.”

“This device was designed to be light in weight,” according to another assessment that same year in the Automobile Journal, “but it is stated that it will easily raise a motor car of medium weight. The Little Giant is claimed to be an advantage over many of the heavier jacks in that it will accomplish the same amount of work with a smaller amount of effort, and also that it is more convenient to carry in the car.”

“The Little Giant jack utilizes the principle of the screw in a different manner [than most other jacks],” Motor World added. “The central threaded member is raised or lowered by the rotation of the horizontal gear wheel and a common ratchet stop determines the direction of rotation of the actuating gear attached to the lever.”

“The Little Giant jack utilizes the principle of the screw in a different manner [than most other jacks],” Motor World added. “The central threaded member is raised or lowered by the rotation of the horizontal gear wheel and a common ratchet stop determines the direction of rotation of the actuating gear attached to the lever.”

These little puppies could supposedly hold up to 4,000 LBS, and the proof of their lasting durability seems to be evident by the number of original Little Giants still floating around auction sites and antique shops 100 years later.

For most people who still recognize the W. E. Pratt name, however, it’s not usually automotive accessories that come to mind.

Origins

Like most of the iron foundries of its day, the Pratt Manufacturing Company didn’t restrict its output by sticking to any single type of product. If something could be forged en masse and sold in bulk, they were willing to make it. Described in 1902 as “large manufacturers of malleable iron castings and hardware specialties,” Pratt’s early catalogs included “hog rings and ringers, cattle dehorners, broom and tool hangers, wire mats, bird cage hooks, trouser hangers, husking pins, post augers, weaners [i.e., calf pacifiers], and numerous other goods.” This versatility was, in many respects, a reflection of the company’s founder and president, William Edward Pratt.

Like most of the iron foundries of its day, the Pratt Manufacturing Company didn’t restrict its output by sticking to any single type of product. If something could be forged en masse and sold in bulk, they were willing to make it. Described in 1902 as “large manufacturers of malleable iron castings and hardware specialties,” Pratt’s early catalogs included “hog rings and ringers, cattle dehorners, broom and tool hangers, wire mats, bird cage hooks, trouser hangers, husking pins, post augers, weaners [i.e., calf pacifiers], and numerous other goods.” This versatility was, in many respects, a reflection of the company’s founder and president, William Edward Pratt.

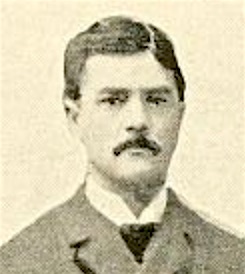

Born in Rhode Island in 1870, William spent most of his youth in Chicago after his father Nelson D. Pratt—a former New York telegraph operator during the Civil War—came West for new business opportunities in the wire trade. Nelson became a “prominent figure” in that industry, according to his 1914 obituary, and it gave William a pretty cush upbringing.

As a student at Lake Forest College in the early 1890s, William Pratt was the big man on campus. There was seemingly no activity in which he wasn’t a standout participant—he ran track, managed the baseball team, played guitar in a concert band, sang in the choir, led bird studies with ornithological groups, and became an officer in various other student organizations. He’d remain devoted to his school for decades after, too, serving as president of the alumni committee for a time.

After graduating in 1892, Pratt wasted zero time jumping into the ranks of Chicago business owners. Possibly utilizing some of his dad’s connections, he organized the W. E. Pratt MFG Co. in 1893 at the age of just 23.

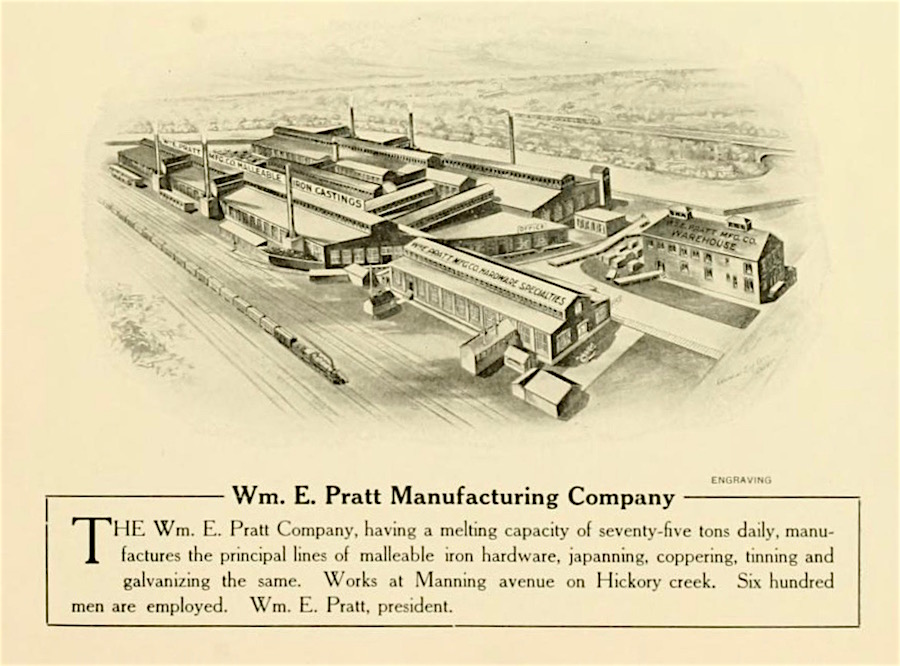

It was a general hardware manufacturing company at first, but by the early 1900s, Pratt had a major foundry plant in the steel-town suburb of Joliet, Illinois, as well as a main office in downtown Chicago at 35 Lake Street. In 1906, the Joliet works were melting about 60 tons of iron per day. And by 1908, the expanded plant included “300 molders, with capacity close to 10,000 tons of castings per year.”

[Image of the Pratt foundry in Joliet, IL, 1909]

[Image of the Pratt foundry in Joliet, IL, 1909]

High on the Hog

The aforementioned doo-dads that the factory produced, which also included stuff like copper blind staples, wire mousetraps, and cowbells, mostly served a rural clientele. Even after Pratt’s success with automotive accessories, the company continued to produce many of those original items, which had gained a very loyal following.

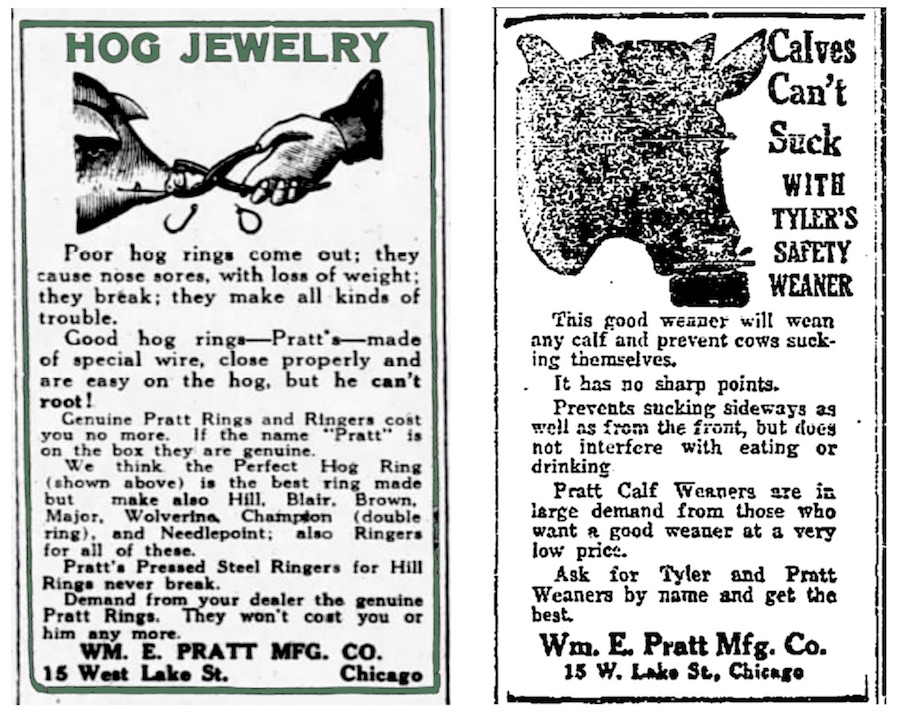

Pratt’s Hog Rings, aka “Hog Jewelry,” for example, were widely promoted through the 1920s, and included a range of popular brands: Hill, Blair, Brown, Major, Wolverine, Champion, and Needlepoint. They basically dominated this highly specialized industry. “If the name ‘Pratt’ is on the box, they are genuine.”

[A pair of 1924 newspaper ads for Pratt Hog Rings and Tyler Safety Weaners]

[A pair of 1924 newspaper ads for Pratt Hog Rings and Tyler Safety Weaners]

If you’re not an old timey farmer yourself, by the way, a hog ring was a metal implement you’d attach through a pig’s snout to prevent it from rooting in the dirt. It was inhumane by nature, since the goal was to make the hog’s nose hurt too much to utilize. The practice has pretty well gone instinct in modern farming, thankfully. But many older folks will still remember W. E. Pratt largely through its association with these barnyard accessories.

Duck Man

By 1917, The Horseless Age noted that Pratt was now making “a complete line of screw jacks, automatic lifting jacks, turntable jacks, tire savers, and three-wheel garage jacks. . . . A special type of Pratt jack is equipped for pulling and emergency lifting purposes, being fitted with a strong chain which will pull the cart out of the deepest mudhole, while the chain alone can be used as a tow chain.”

With the added auto part production proving fruitful, the W. E. Pratt MFG Co. was really in its golden age. In the 1920s, the company’s Chicago offices moved down the street to a new building at 190 N. State Street (pictured below), above the State-Lake Theater (now the ABC7 TV studios) and across the street from the brand new Chicago Theater.

[The W. E. Pratt MFG Co. offices were located here at 190 N. State St. in the 1920s]

[The W. E. Pratt MFG Co. offices were located here at 190 N. State St. in the 1920s]

William Pratt could have spent his days in his office there, enjoying life as one of the iron tycoons in a concrete jungle. But as evidenced by his younger days at Lake Forest College, he was more of an outdoorsman by heart.

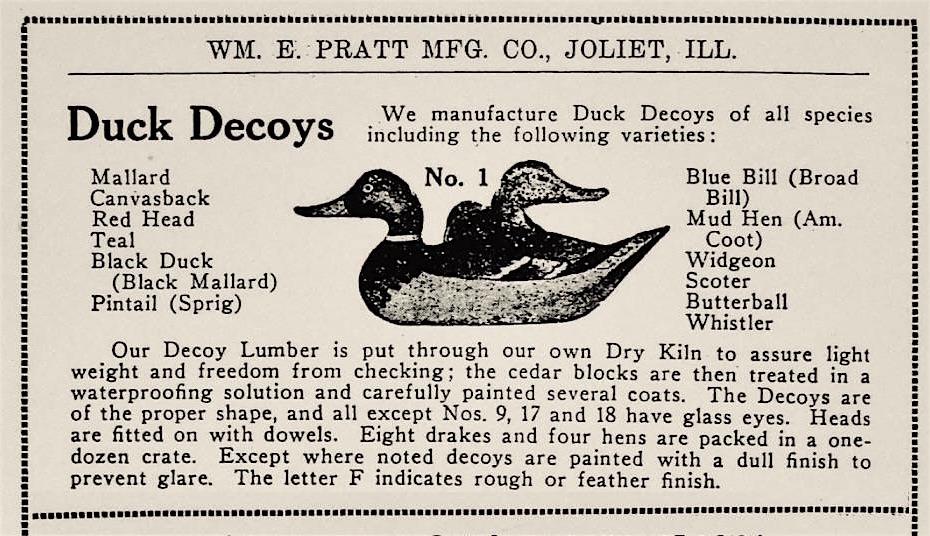

Thus, in the early 1920s, Pratt shifted much of his focus to . . . ducks. No, not ducts. DUCKS. Specifically, decoy ducks—the wooden, meticulously painted hunting props that have since evolved into wildly popular collectibles. The ones that render clones of popular North American species like the Blue Wing Teal and the Bufflehead.

The Pratt plant, to the likely confusion of some, started its own duck wing in 1921, and by 1924, Mr. Pratt had purchased the popular Mason line of decoys (out of Detroit), giving him an inside track on a new duck dynasty.

The Pratt plant, to the likely confusion of some, started its own duck wing in 1921, and by 1924, Mr. Pratt had purchased the popular Mason line of decoys (out of Detroit), giving him an inside track on a new duck dynasty.

Unfortunately, despite W.E.’s passion for decoys, he seemed more willing to cut corners when it came to their manufacture. Most of today’s duck decoy experts (again, there are way more than you would possibly believe) note that Pratt’s attempts to recreate the high-quality Mason production line resulted in far inferior ducks—with rushed painting and weak sanding and finishing practices. Pratt ducks were also marketed under several different manufacturing names, probably so Pratt could better track where its orders were coming from

Lower quality or not, the duck decoys proved to be yet another successful gamble, selling like gangbusters via Chicago-based mail order catalogs like Sears Roebuck and Montgomery Ward.

Radioactive

It took the Great Depression to finally slow the development of the W. E. Pratt MFG Co. In his later years, William Pratt was still coming into the Joliet plant on a regular basis, overseeing his creation. His health began to fail in the fall of 1935, however, and he died the following March at age 66.

William’s widow Clara Lord Pratt dutifully and effectively took over the company presidency for a time, but she soon elected to sell the business and the Joliet works to the Joslyn Manufacturing and Supply Co. Joslyn, in turn, unloaded the decoy duck portion of the business on the Animal Trap Company of America. The Joliet plant went back to focusing on hardware stuffs, while the Pratt name lived on for years as a division of both Joslyn and Animal Trap.

Which brings us to the Manhattan Project.

Which brings us to the Manhattan Project.

Huh?

Well, in 2001—according to the Chicago Tribune—the U.S. government released a list of over 300 “mills, factories and research institutions that it believes may have exposed workers to toxic and radioactive materials during nuclear weapons production or in work for the Department of Energy.” A whopping 24 of these facilities were in the Chicago area, and the Pratt plant in Joliet was one of them.

The University of Chicago had been one of the major players in nuclear research during the war years, and, as the Tribune recounts: “In spring 1943, Pratt and its parent company, Joslyn Manufacturing and Supply Co., began machining uranium slugs for the first reactors built at the U. of C. In 1944, Pratt also machined uranium rods for the Metallurgical Laboratory.”

The larger goal, supposedly, was to figure out how uranium metal could be handled in turret lathes and automatic screw machines.

So, were Pratt employees unknowingly subjected to potentially dangerous levels of radiation over the three-year course of this work? Eh, probably. It took over 40 years for actual radiological tests to be done on the original facility, and by then, it tested at “below instant death levels” (paraphrasing). Still, if you were a longtime Joliet employee who’d gone from the car jack line to the mallard line to the uranium line… you certainly must have had some bizarre stories to tell.

Sources:

“Little Giant Screw Jack” – The Horseless Age, Vol. 36, 1915

“Power of Screw of Great Utility” – Motor World, May 8, 1913

“No Rooting, Period” – FarmCollector.com, October 2002

“W. E. Pratt Dies; Wealthy Joliet Manufacturer” – Chicago Tribune, March 26, 1936

“W.E. Pratt Manufacturing Company” – Waste Lands: America’s Forgotten Nuclear Legacy, Wall Street Journal, 2013

Who owns that stunning Blue Wing Teal hen that was used earlier in this article? I would love to own that.

Frank Fiske

Baltimore

My name is Jeffrey Pratt Andrews, am a decedent of Wiilam E.

I have two jacks and a bottle opener! I’d love another bottle opener.

My cousin Willim Pratt Andrews also have a bottle opener.

Hi Kristin! Kristin Flynn is my first cousin.

RE: Kristin Flynn

William E. Pratt was also my paternal great grandfather. It would appear that we are related. I don’t have any of the tire jacks but I have collected some of his duck decoys over the years.

I believe my great grandfather may have worked at the foundry in Joliet in the early 1900’s – 1910. Does anyone think the museum might still have employment records from back then?

Unfortunately our museum doesn’t have documents of that nature, Susan. It could be worth trying the Chicago History Museum or Chicago Public Library. –Made In Chicago Museum

I have a jack like the one in the picture in mint condition I would like to know how much is it worth

Sold one recently for 75$

I HAVE 2 OF THESE JACKS LOOKING TO SELL BOTH ,

I found a Jack like this one in old house. works what is it worth?

William E. Pratt was my paternal great grandfather. (My father and bother are both William Pratt Andrews). Interesting article. Thanks for sharing! I don’t suppose you would have any idea where I could find any antique parts that were manufactured by his company. That would be so cool!

Pratt items are actually quite easy to find on eBay, including tire jacks like the one in our collection. It would be great to have one back in your own family collection. 🙂