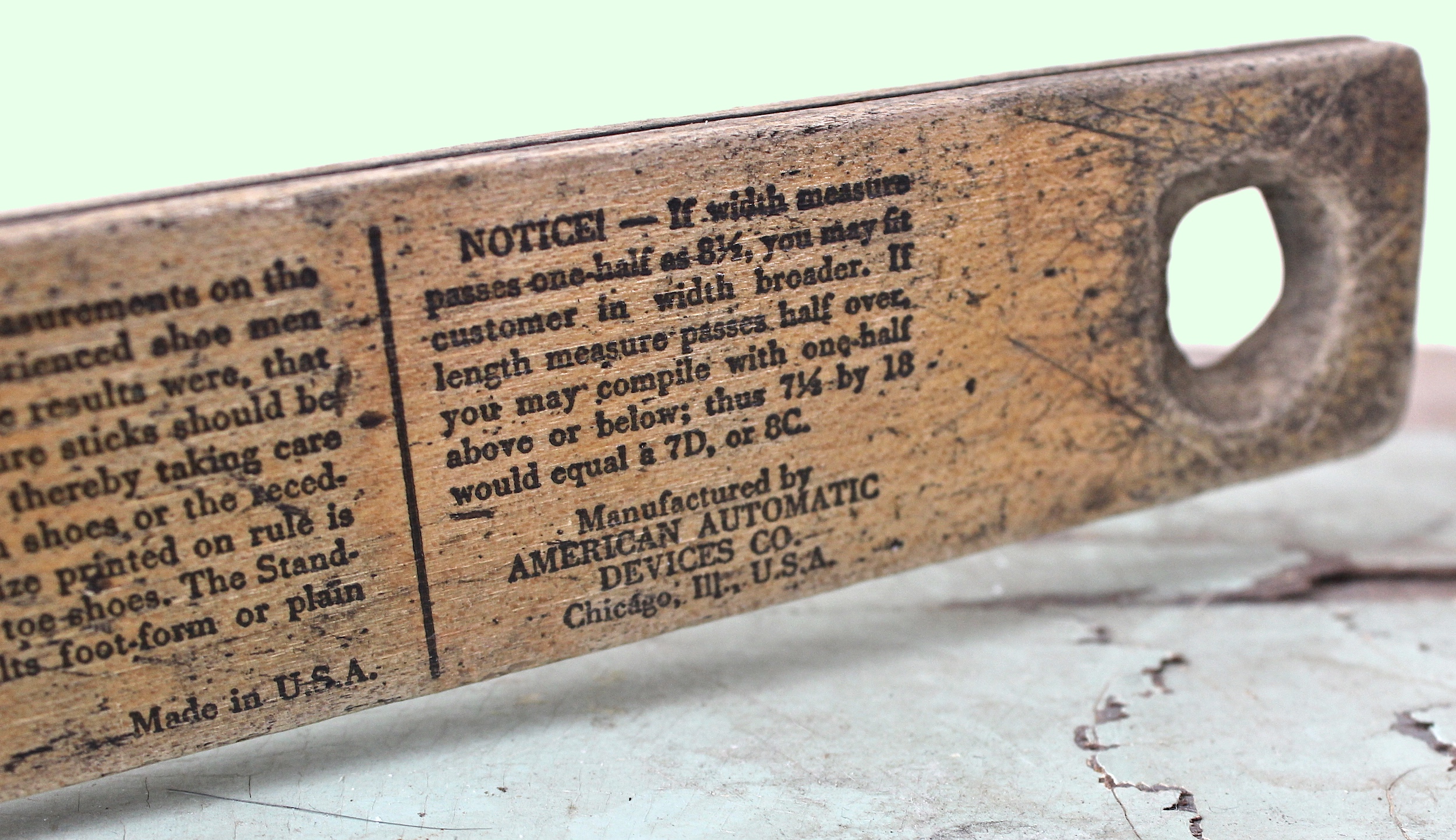

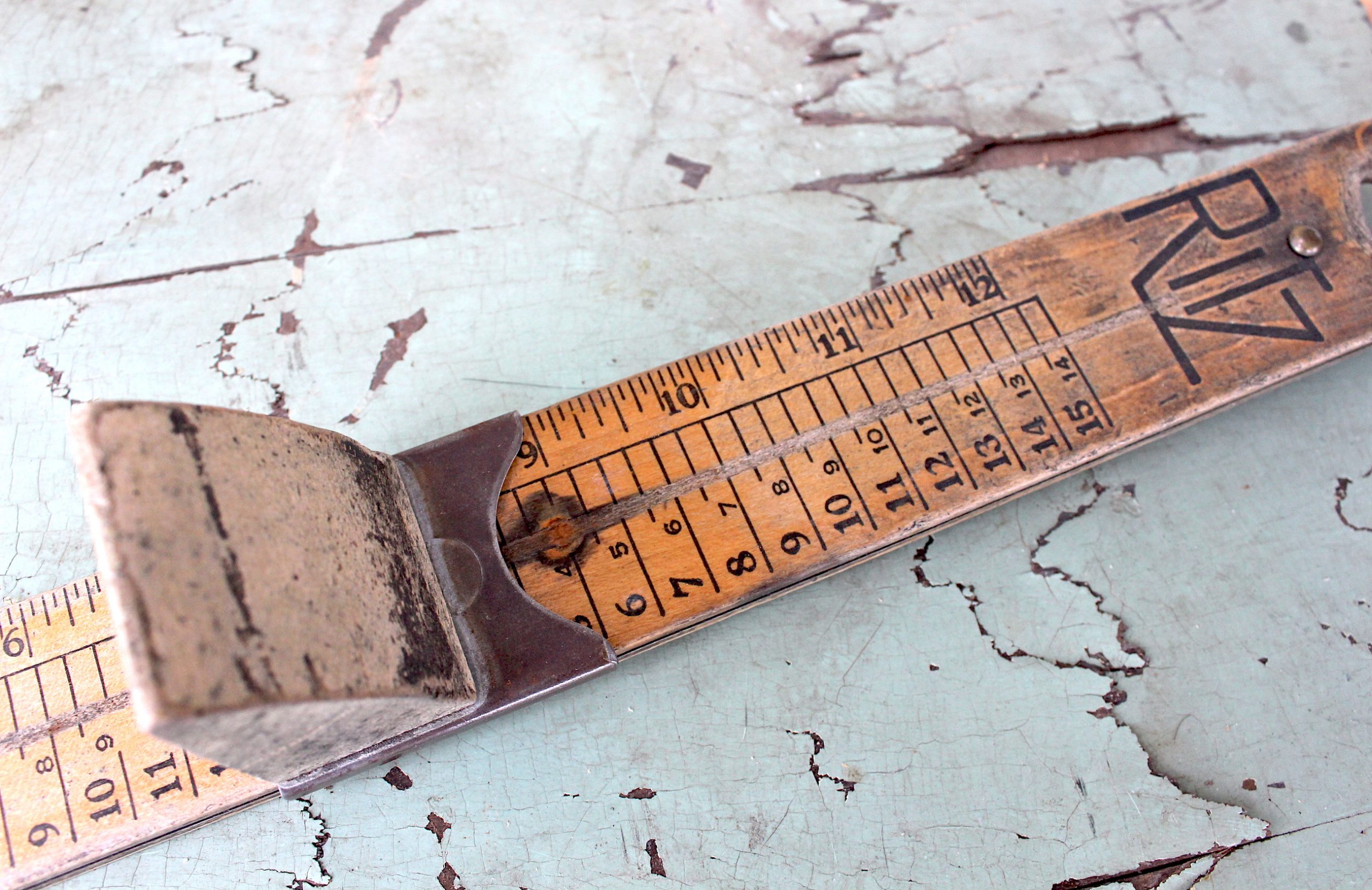

Museum Artifact: Ritz Stick Foot Measure, c. 1920s

Made by: American Automatic Devices Co. / King Bee MFG Co, 500-530 S. Throop St., Chicago, IL [Near West Side]

When a stick of any kind becomes culturally relevant enough to have its own name, we tend to ascribe it a simple, self-descriptive one: match stick, hockey stick, joy stick. A rare exception is the Ritz Stick, a 100 year-old device that’s still manufactured to this day, and is named not for its purpose (measuring feet), but for the fellow who invented it.

The “Ritz” in Ritz Stick is Oliver Cornelius Ritz-Woller, founder of Chicago’s American Automatic Devices Company. Oliver Cornelius Ritz-Woller. . . the name basically immortalizes itself, doesn’t it? Still, to Oliver’s credit, he didn’t coast through life on the strength of his cool-sounding moniker alone. He was—like so many other business owners in the Made-In-Chicago Museum—an idea man.

Getting His Feet Wet (and Properly Sized)

Ritz-Woller was born in Jacksonville, Florida, in 1882—the son of German immigrants and the youngest of four kids. His father died when he was a teenager, so it was his big brother Alex—ten years his senior—who took on the mentor role in the years ahead. Alex was a shoe merchant in Jacksonville, and a fairly successful one. After Oliver graduated from Stetson University, he joined the family business, which was rechristened “Ritzwoller Bros.”

That could have been the end of the story right there. As businesses go, selling shoes is a fairly stable one, since people tend to keep needing new ones. And having Alex handle most of the business end of things was all well and good. For Oliver, though, there were distractions and daydreams. In particular, he had a passion for the brand new industry of the automobile, and saw opportunities to use his education to break into that field.

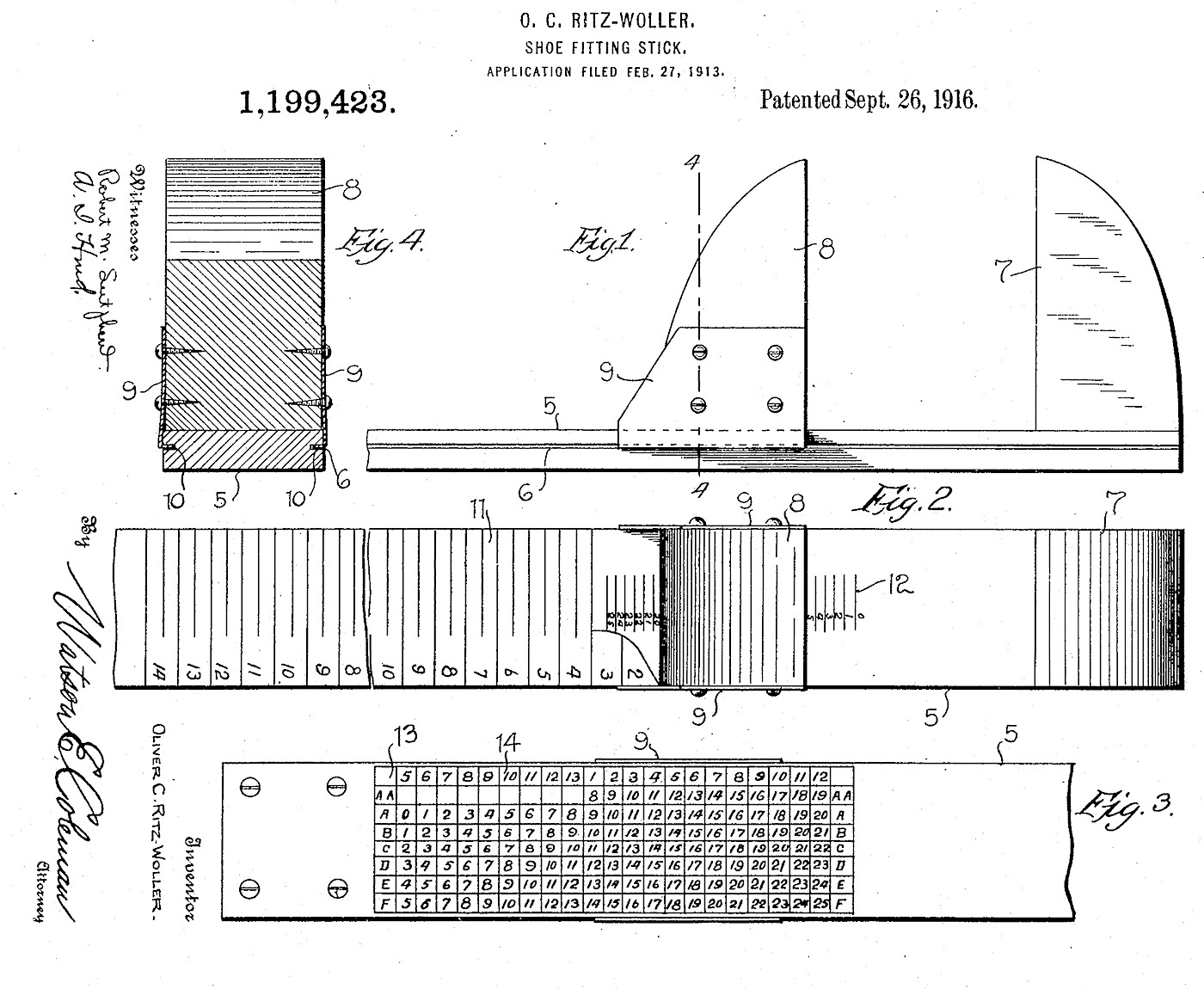

In 1913, a little after turning 30, he applied for patents on a few different automotive devices, including a fluid gauge and a gasoline-feed system. While he was at it, on a lark perhaps, he took a shot at patenting a handy tool he’d crafted for the Ritzwoller Brothers shoe shop, too. It was a custom measuring device he called a “Shoe Fitting Stick.”

“This invention relates to an improved shoe fitting stick such as is employed by a shoe salesman in fitting shoes,” he wrote in his application, “and has for its primary object to provide a device of this character whereby the proper width as well as the necessary length shoe may be very quickly and accurately ascertained.”

The Ritz Stick, as it’s manufactured and sold now in the 21st century by the Woodrow Engineering Company, is in most respects the same design Ritz-Woller described in such exhilarating detail a century ago: “a fixed heel block and a longitudinally slidable toe block; said latter block in the present construction, being also adapted for engagement with one side of the ball of the foot when the foot is disposed across the stick and against the heel block; said stick being provided upon its upper surface with a length scale and a width scale, and upon its reverse side with a chart whereby the last width may be computed in accordance with the length measurement.”

Yup, that’s a Ritz Stick.

“Necessities of Merit”

Once Oliver C. Ritz-Woller established himself as an inventor, things changed quickly in his life. The Ritzwoller Brothers shoe operation was retired by the end of 1913, and Oliver left Jacksonville entirely, seeking to turn his patents into profits in Chicago. He was still a single fella and was heading north for a new start.

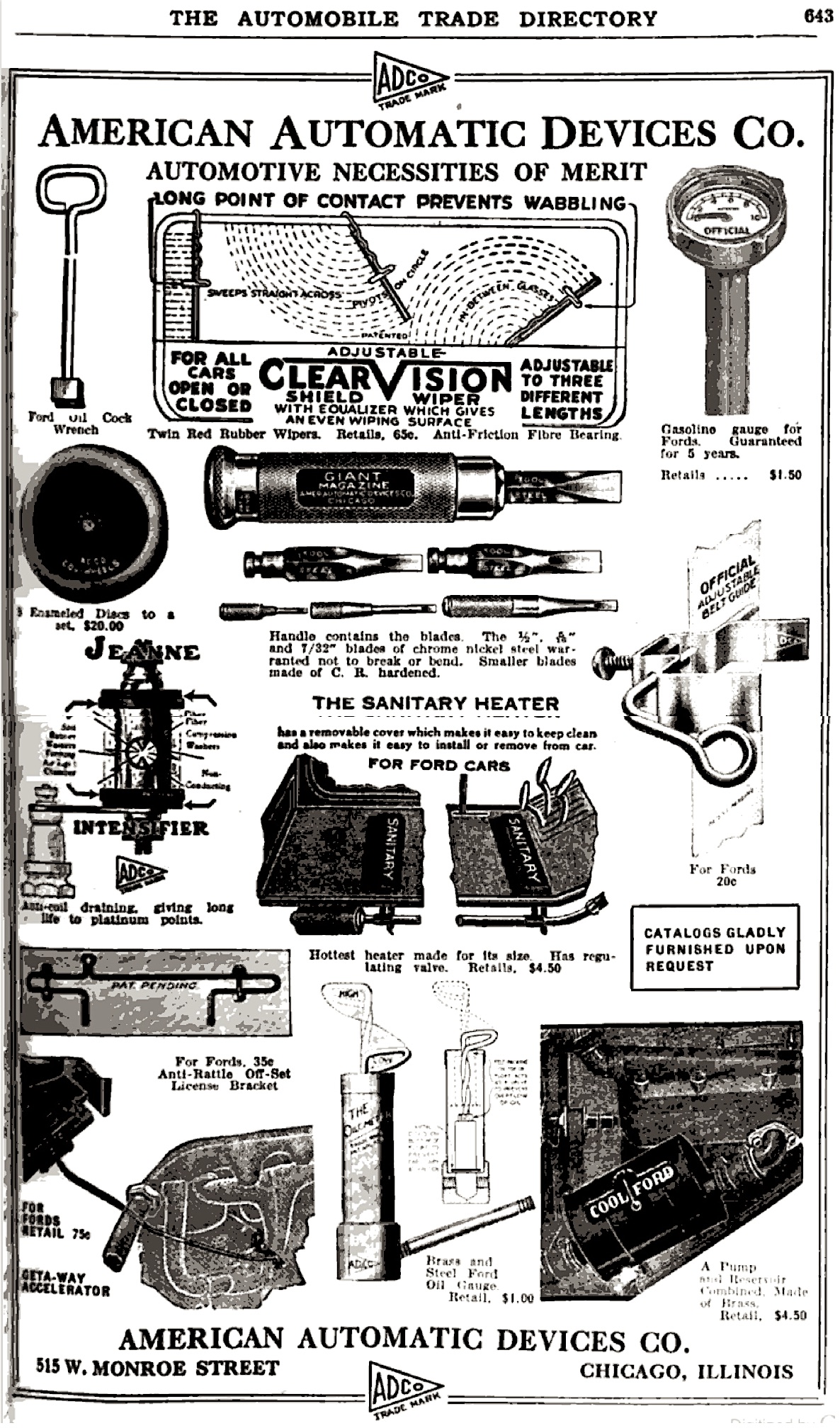

By 1914, official patents were issued for his early automotive accessories, and in 1916, the Shoe Fitting Stick was legally recognized, as well. Oliver Ritz-Woller was in business. He purchased space in the Rand McNally Building to go with his personal office at 536 S. Clark St., and a plant was organized at 3264 W. Grand Avenue. Ritz-Woller called his first venture the Oliver C. Ritz-Woller Company (est. 1915) and followed it quickly with the American Automatic Device & Novelty Co., later shortened to American Automatic Devices Co.

By 1914, official patents were issued for his early automotive accessories, and in 1916, the Shoe Fitting Stick was legally recognized, as well. Oliver Ritz-Woller was in business. He purchased space in the Rand McNally Building to go with his personal office at 536 S. Clark St., and a plant was organized at 3264 W. Grand Avenue. Ritz-Woller called his first venture the Oliver C. Ritz-Woller Company (est. 1915) and followed it quickly with the American Automatic Device & Novelty Co., later shortened to American Automatic Devices Co.

The next few years were equally momentous. In 1918, at the age of 36, Ritz-Woller registered for military service, identifying his profession at the time as “manufacturer of metal goods.” Fortunately, World War I was in its waning days, because Oliver had more appealing prospects on the homefront.

He married his first wife Jeanette a year later, and also relocated the American Automatic HQ to 515 W. Monroe Street. By the mid 1920s, with the auto parts business booming, the company found its permanent home at 500-600 S. Throop St., between Congress Parkway and Harrison. Decades later, that ground would be flattened with the coming of the Interstate 290 expansion. The University of Illinois-Chicago now occupies some of the old real estate, as well.

[American Automatic Devices factory at 500 S. Throop Street, 1924]

[American Automatic Devices factory at 500 S. Throop Street, 1924]

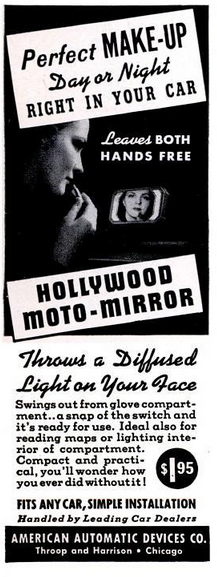

For a good 30-year period, though, that West Side factory was where Ritz-Woller turned his little ideas into grand returns. He remained a fairly significant pioneer in the field of automotive accessories, patenting an early model of windshield wipers, along with rear-view truck mirrors, license plate holders, warning lights, and step-up plates. But Oliver was just as happy to collect patents on random other hodge podgery, as well, from cigarette cases to make-up mirrors and electric irons.

Of course, the star of our show, the Ritz Stick, had become ubiquitous in shoe shops from Jacksonville to L.A.; although its marketshare would eventually be challenged by similar designs from the likes of Dr. Scholl himself, William M. Scholl (another Chicagoan), who patented a self-described “improvement” on the Ritz Stick in 1935. Such were the occasional pitfalls of running a highly diversified business; Ritz-Woller couldn’t always keep all his proverbial plates spinning at once, and competition—whether from footcare moguls or car parts manufacturers—was always on his heels.

Of course, the star of our show, the Ritz Stick, had become ubiquitous in shoe shops from Jacksonville to L.A.; although its marketshare would eventually be challenged by similar designs from the likes of Dr. Scholl himself, William M. Scholl (another Chicagoan), who patented a self-described “improvement” on the Ritz Stick in 1935. Such were the occasional pitfalls of running a highly diversified business; Ritz-Woller couldn’t always keep all his proverbial plates spinning at once, and competition—whether from footcare moguls or car parts manufacturers—was always on his heels.

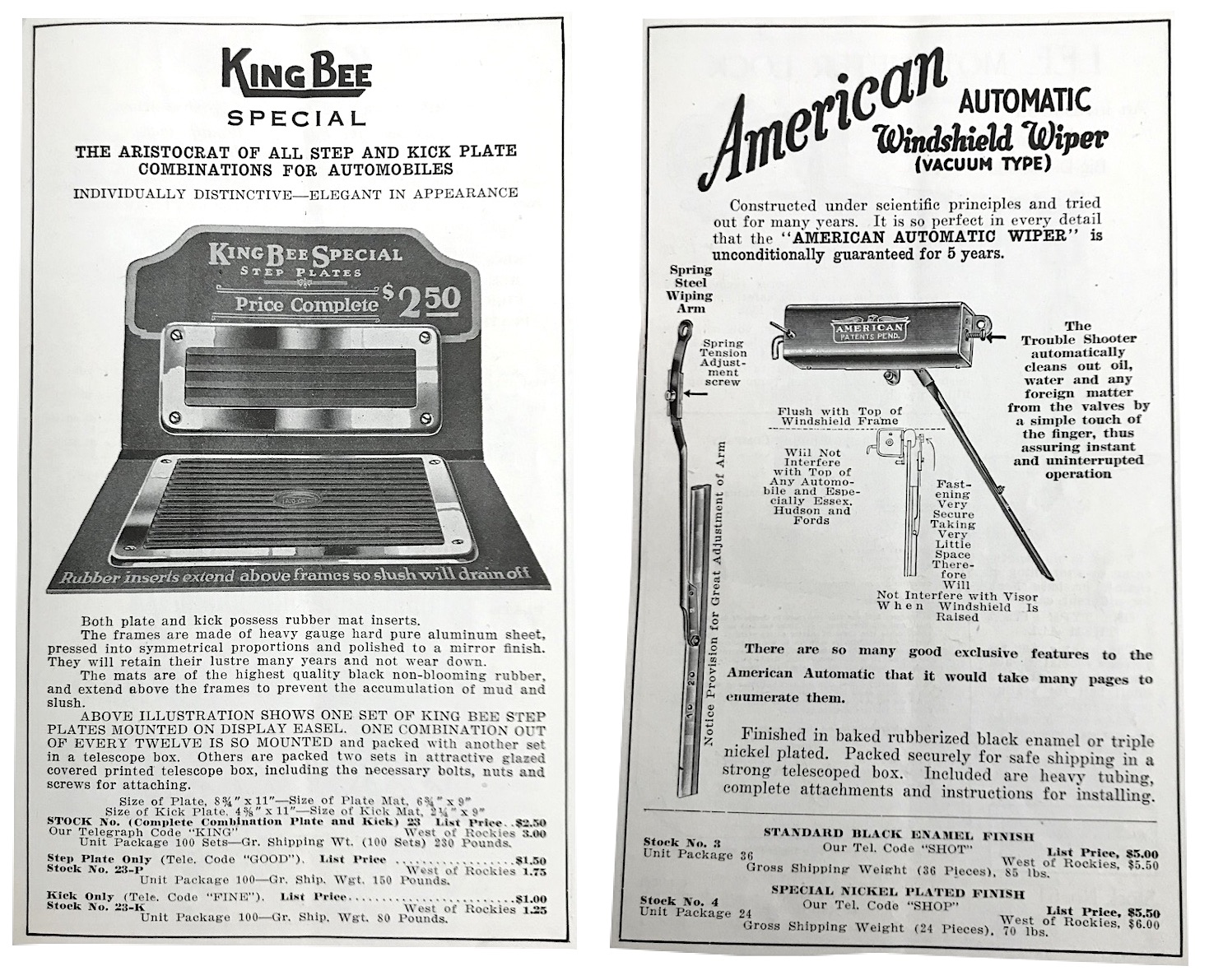

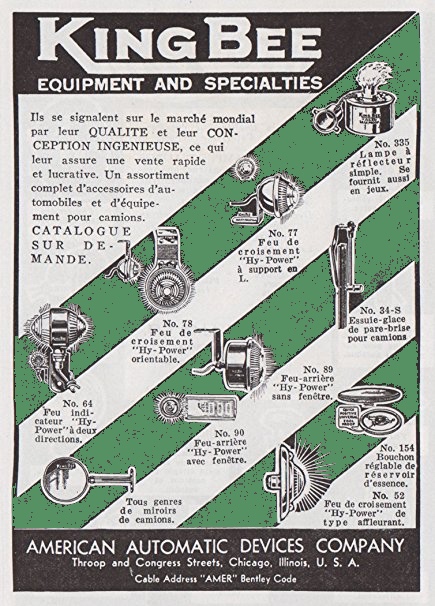

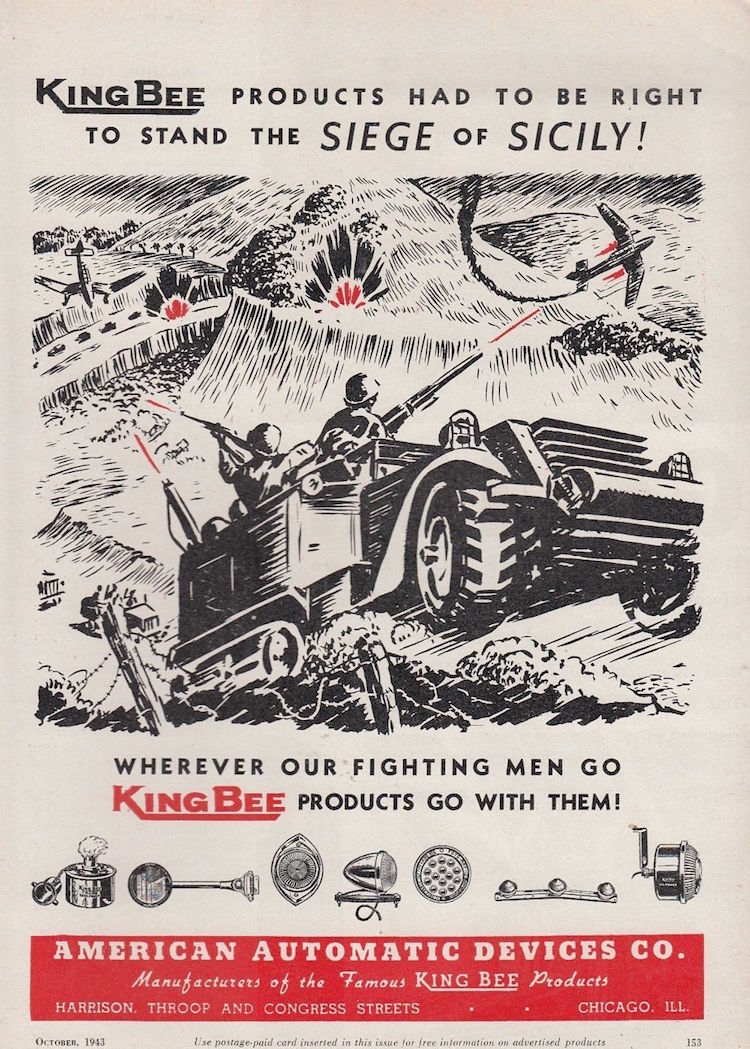

Perhaps a bit overwhelmed, Ritz-Woller divided American Automatic Devices into a few subsidiaries, including King Bee Manufacturing (focused on automotive) and the R-E Electric MFG Co. All operations were headquartered at the Throop Street plant, and by the company’s industrial peak in the mid 1940s, it employed over 200 workers.

Again, this would have been a fine place to end the story. Oliver Ritz-Woller was approaching his retirement years (he married twice more after the age of 60), his company was chugging along, and America was rejoicing in the bliss of victory in World War II. It was right at this moment, though, that our happy tale takes a surprisingly nasty turn.

[Pages from American Automatic Devices’ 1924 catalog, showing the King Bee brand name already in use on its popular step plates]

[Pages from American Automatic Devices’ 1924 catalog, showing the King Bee brand name already in use on its popular step plates]

STRIKE!

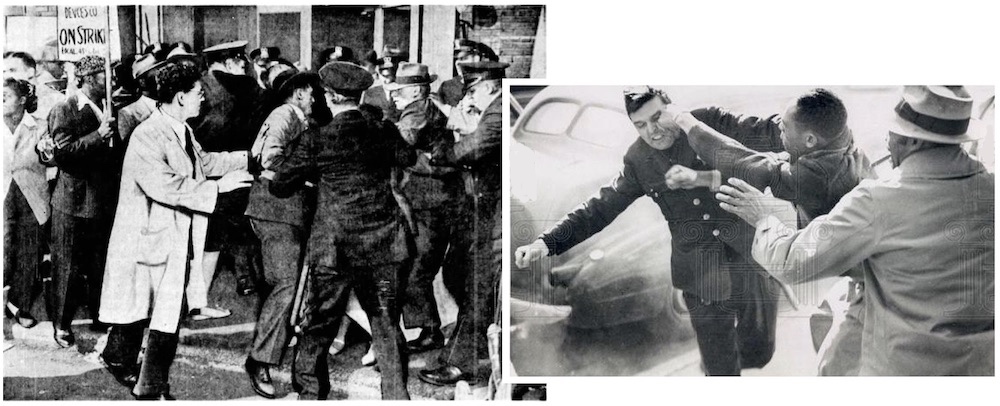

In August of 1946, 127 employees of American Automatic Devices—all members of United Auto Workers local 453—went on strike. They were demanding a pay increase of 18.5 cents per hour, and the company wouldn’t go above 10. By October, the number of striking employees had decreased, but the remaining picketers outside the factory had been joined by throngs of UAW supporters with no direct connection to American Automatic Devices Co.

Soon, the situation escalated into several days of violent clashes. Some non-union employees of American Automatic, including several women, claimed they were hassled and even physically attacked by picketers. This led to the arrival of several dozen police on the scene. And from there, we’re left to sift through news reports of a 70-year old incident with two very different accounts of what happened.

[Helen Mateja and Juanita Pulido, both employees of American Automatic Devices, claimed they were attacked by Union picketers outside the plant]

[Helen Mateja and Juanita Pulido, both employees of American Automatic Devices, claimed they were attacked by Union picketers outside the plant]

On October 4, 1946, the home of the Ritz Stick was encircled by men with a far more archaic device, the nightstick. Chicago police resorted to using these weapons on more than 20 union picketers, many of them African-American. Three men wound up in the hospital (and also under arrest). According to the Chicago Tribune, it was the first time police had been permitted to use their clubs in a labor dispute since before the war.

The official police story was that the UAW Union had sent “sluggers” to the picket line—none of whom were American Automatic Devices Co. employees—for the sole purpose of starting a rumble.

“These men were not workers,” police captain George Barnes told the Tribune. “When my men are pitted against sluggers they’re going to fight the way they did today. These are deliberate and planned attacks to make trouble—and trouble is what they’re going to get.”

[UAW picketers clash with employees and police outside the American Automatic Devices Co. factory in 1946.]

[UAW picketers clash with employees and police outside the American Automatic Devices Co. factory in 1946.]

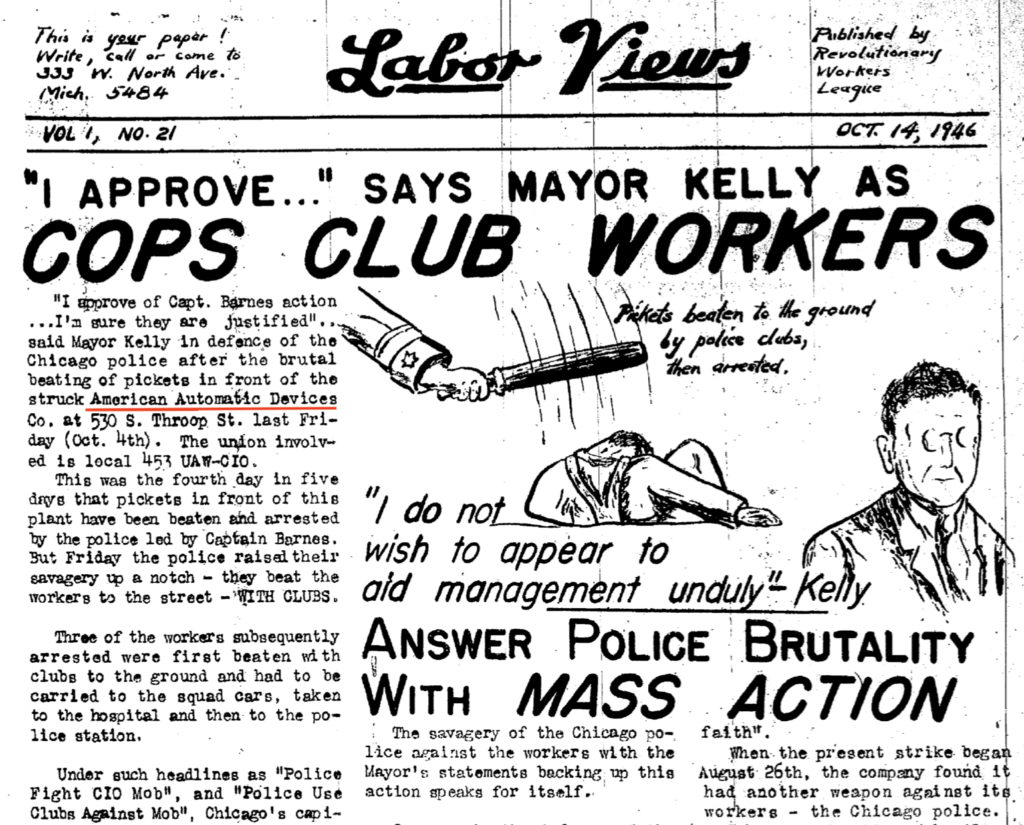

Meanwhile, the reaction to these events from the political left was something else entirely. One pro-union newsletter, “Labor Views,” called it a simple case of police brutality.

“The entire labor hierarchy in Chicago has proved itself completely bankrupt in the face of renewed brutality from Chicago police,” the newsletter claimed on its front page. “On October 4th, fifty police made an unprovoked attack with clubs on twenty pickets of UAW Local 453 in front of the American Automatic Devices Co. at 530 S. Throop St. Unarmed workers were beaten to the ground with clubs, one worker sinking to the street with his picket sign still clutched in his hands.”

One event, two versions, loads of biases on both sides. Some things never change.

There’s no record I could find of Oliver Ritz-Woller’s own opinion on all this, but his factory was forced to shut down for a time as the chaos was dealt with. The company filed an injunction, as well, to limit the number of picketers allowed outside the plant. They pitched it as a public safety issue, and the courts eventually agreed, placing a weirdly random limit of 21 picketers permitted on the location.

The company survived this brutal stretch, but times were changing anyway. Ritz-Woller had already started outsourcing some of his manufacturing. This included the iconic Ritz Stick itself, which was being contract printed by an upstart Chicago scale-ruler manufacturer, the Woodrow Engineering Co.

The Queen Bee of King Bee

In 1949, a now 67 year-old Ritz-Woller married his 47 year-old secretary, Zella Cherry Curtis. They were together for ten years, up to Oliver’s death in 1959, but few realized just how active a role Zella was playing in the day-to-day operations of the business.

During the 1950s, Ritz-Woller’s once mighty empire had been mostly centralized around the King Bee Manufacturing wing, with production moving to suburban Bellwood, IL. With her husband’s health waning, the smart, hard-nosed Zella stepped in and learned the ropes, becoming Vice President of King Bee and largely plotting its course. She had no shortage of doubters, of course, both as a result of her gender and her relationship with the boss. But this was no “dizzy dame.”

During the 1950s, Ritz-Woller’s once mighty empire had been mostly centralized around the King Bee Manufacturing wing, with production moving to suburban Bellwood, IL. With her husband’s health waning, the smart, hard-nosed Zella stepped in and learned the ropes, becoming Vice President of King Bee and largely plotting its course. She had no shortage of doubters, of course, both as a result of her gender and her relationship with the boss. But this was no “dizzy dame.”

The daughter of a Hungarian immigrant coal miner, Zella had been working since the age of 10, supporting her family and saving up cash for business college. As a kid, she made money as a “stogie roller” in a cigar factory, getting her lessons in the tough realities of factory life. She continued to clean houses while in college, and eventually had a long career as a secretary before finding her new path with Ritz-Woller and King Bee.

“When petite Zella Ritz-Woller, president of King Bee Manufacturing Company, was widowed four years ago, she stepped into her husband’s shoes,” a 1962 article in the Detroit Free Press reported. “And they were big. The million-dollar-a-year King Bee Manufacturing Company employs 60 people, and has 32 sales representatives throughout the country.”

King Bee was still a respected producer of classic American Automatic Devices like rear view mirrors, tail lights, turn signals, etc. As such, no shortage of opportunistic vultures descended on Zella’s doorstep after her husband’s death, hoping to take advantage of a novice. Again, they didn’t know who they were dealing with.

“Mrs. Ritz-Woller has just survived a fairy-tale tug-of-war for the life of her business,” the Free Press story continued. “A veritable Little Red Riding Hood, she was caught in a squeeze play for control of the firm with a pair of unscrupulous men—one a trusted employee, the other a respected competitor.

“Mrs. Ritz-Woller has just survived a fairy-tale tug-of-war for the life of her business,” the Free Press story continued. “A veritable Little Red Riding Hood, she was caught in a squeeze play for control of the firm with a pair of unscrupulous men—one a trusted employee, the other a respected competitor.

“She survived their tactics to forge merger and to undermine customer confidence because she had loyal customers and loyal employees. And because she had business know-how.

“Her most memorable moment was when she took over the firm’s presidency, having served as vice-president for 14 years.

” ‘So many people wanted me to sell, but conserve my assets,’ she said. ‘I couldn’t. I had a lot of loyal people to consider. Two days after my husband’s funeral I called a meeting of key personnel and told them everything would go on as it had.’ “

Zella Ritz-Woller eventually agreed to sell her controlling stock in King Bee, on her own terms, to the Novo Industrial Corp. in 1965. A news report identified her in the transaction as “Mrs. Oliver C. Ritz-Woller,” subtly ignoring her own 18 years with the business.

And Your Little Dog, Too

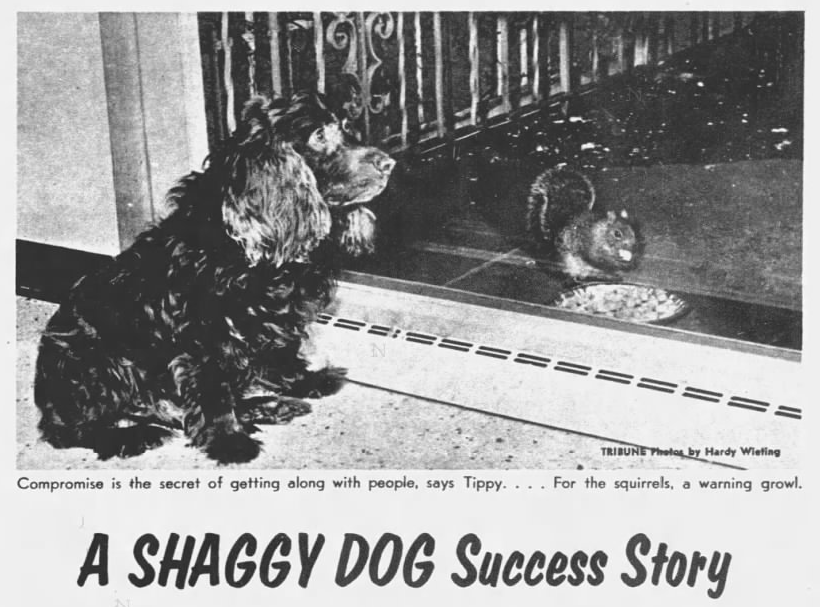

As a weird penultimate chapter in a story that has admittedly touched some discordant notes, we have the insider perspective of Oliver and Zella Ritz-Woller’s most trusted friend . . . Tippy the Dog.

Yes, in 1962—the same year Zella was getting much of her publicity for taking over the King Bee business—her pet pooch apparently “wrote” an op-ed piece for the Chicago Tribune. Why? How? I do not have any idea. Maybe the Tribune was just testing the boundaries of journalism in JFK’s America. Whatever the rationale, the article was called “A Shaggy Dog Success Story,” by Tippy, as told to Eleanor Page.

Surprisingly, the ridiculous dog essay actually has some heartwarming moments, at least for those of us familiar with Tippy’s dear departed master, Oliver C. Ritz-Woller.

“I picked up most of my business know-how from Mr. Oliver C. Ritz-Woller,” Tippy claimed, with barks presumably translated by Ms. Page. “Before he died he used to say I’d make a good salesman and he’d like to put me on the road. … Those man-to-dog talks with Mr. Ritz-Woller really paid off for me after his death when it came time to assume responsibilities. I’ve been going to the King Bee office and running the business ever since, with Mrs. Ritz-Woller’s help. Lately I’ve been letting her do more and more of the managerial work. I feel my age now and it’s about time for me to retire.”

Zella Ritz-Woller was 60 years old when this article ran, and you have to wonder if she pitched the Tribune a cute story about her pooch because—in 1962—readers might more easily accept a female CEO if they thought she was taking orders from a dog.

Alas, we’ll never known her motivations for sure, having never walked in her shoes. If we ever could walk in her shoes, however, we would certainly expect that they’d be sized correctly.

The Ritz Stick, Today

After Oliver Ritz-Woller’s death, all rights to his famous Ritz Stick patent passed over not to Zella, but to Charles A. Ball, Jr., owner of the Woodrow Engineering Company, which had been manufacturing the product for quite some time.

By the time Woodrow took over full ownership of the Ritz Stick, there was, unfortunately, considerably more competition in the shoe sizing business. The Brannock Device, a metal measuring tool developed in the 1920s and manufactured by the Brannock Device Company of Syracuse, New York, had gradually emerged as the preferred industry standard.

And yet, the appeal of the simple wooden Ritz Stick endured.

Charles Ball moved Woodrow Engineering to Door County, Wisconsin, in 1971, and his son Michael took over the business in 1986, eventually repackaging the old Ritz Stick in new ways—particularly as an affordable, customizable advertising tool for companies, be they footwear related or otherwise.

You can get your very own custom Ritz Sticks, or just some simple old-fashioned ones, by going to FootMeasure.com [a special shoutout to Michael Ball, as well, for sharing some information with the Made-In-Chicago Museum about Woodrow’s role in the history of the Ritz Stick].

[Ad from a 1921 issue of Automobile Trade Directory]

[Ad from a 1921 issue of Automobile Trade Directory]

Sources:

“Police Club 20 CIO Sluggers” – Chicago Tribune, October 5, 1946

“A Shaggy Dog Success Story” – Chicago Tribune, April 8,1962

“Four Women Executives: How They Tick,” Detroit Free Press, Sep 23, 1962

Boot and Shoe Recorder, Volume 63, 1913

“10 to Get Free Enterprise Association Awards,” Daily Press, Newport News, VA, Nov. 29, 1962

Automobile Trade Directory, Vol. 19, 1921

Archived Reader Comments:

“Fantastically written article! Not only was I educated, but, I was thoroughly entertained. Thank you. I came here looking to learn more about the Ritz Stick, and I did, plus!!” —Van Kiser, 2020

“I have a vintage bulb lighted mirror. The information on the bottom displays as US Patent 1873943 and Canadian Patent 334083. I assume this mirror was a prototype and was made by the American Automatic Device Co in Chicago.” —BH, 2020

I have a King Bee Ace Leak Proof Safety Flare. I have no use for it. You are welcome to it if you would like. Not in great shape. If you want it for free please tell me where to mail it.

Found an old red glass lens, thought it was some sort of automotive light lens. It had the name stamped in the glass and I researched and found the article. Still trying to figure out was accessory it might have been a part of.

Excellent article. I was curious about an old aluminum cigarette case I bought at a junk show. A quick search sent me to this article. Thank you.