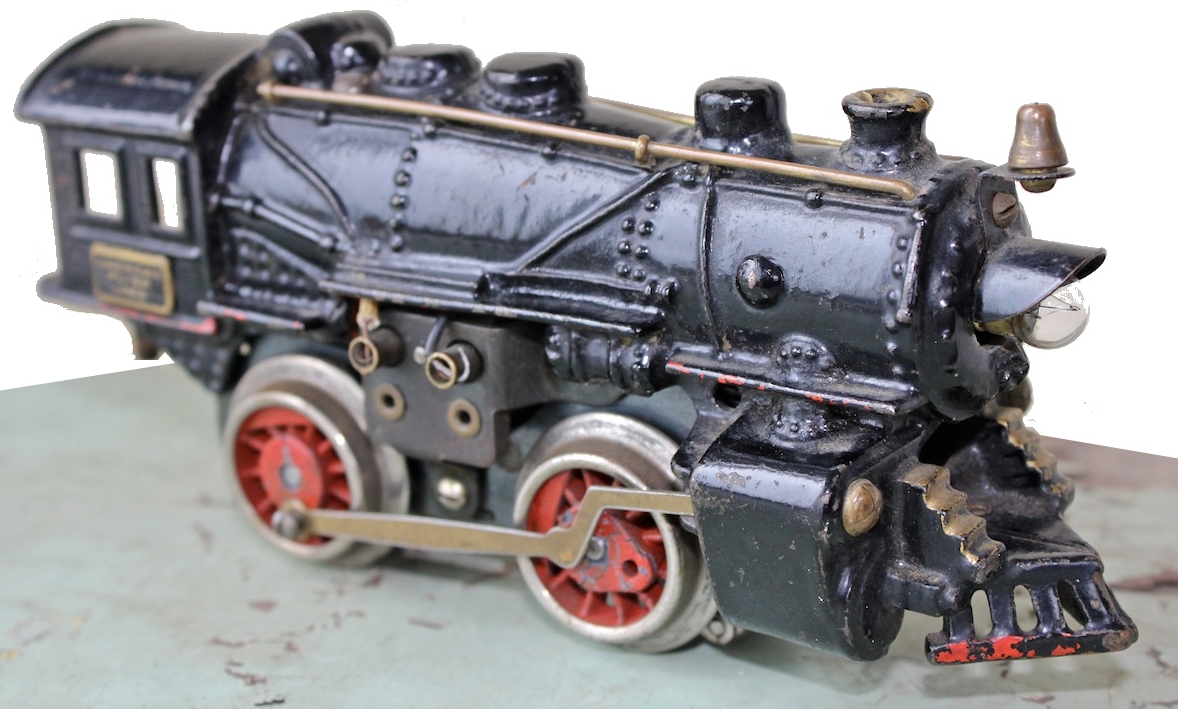

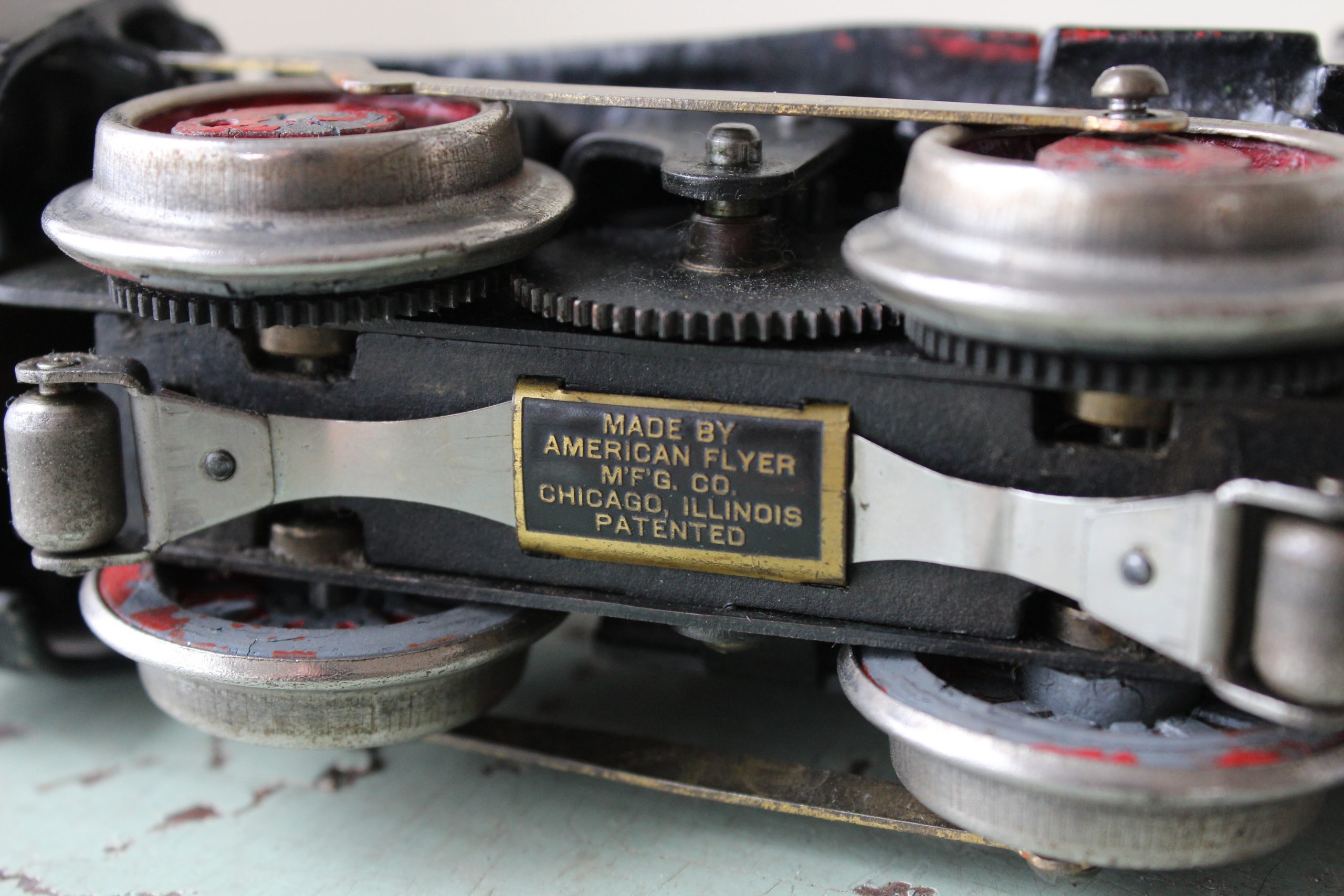

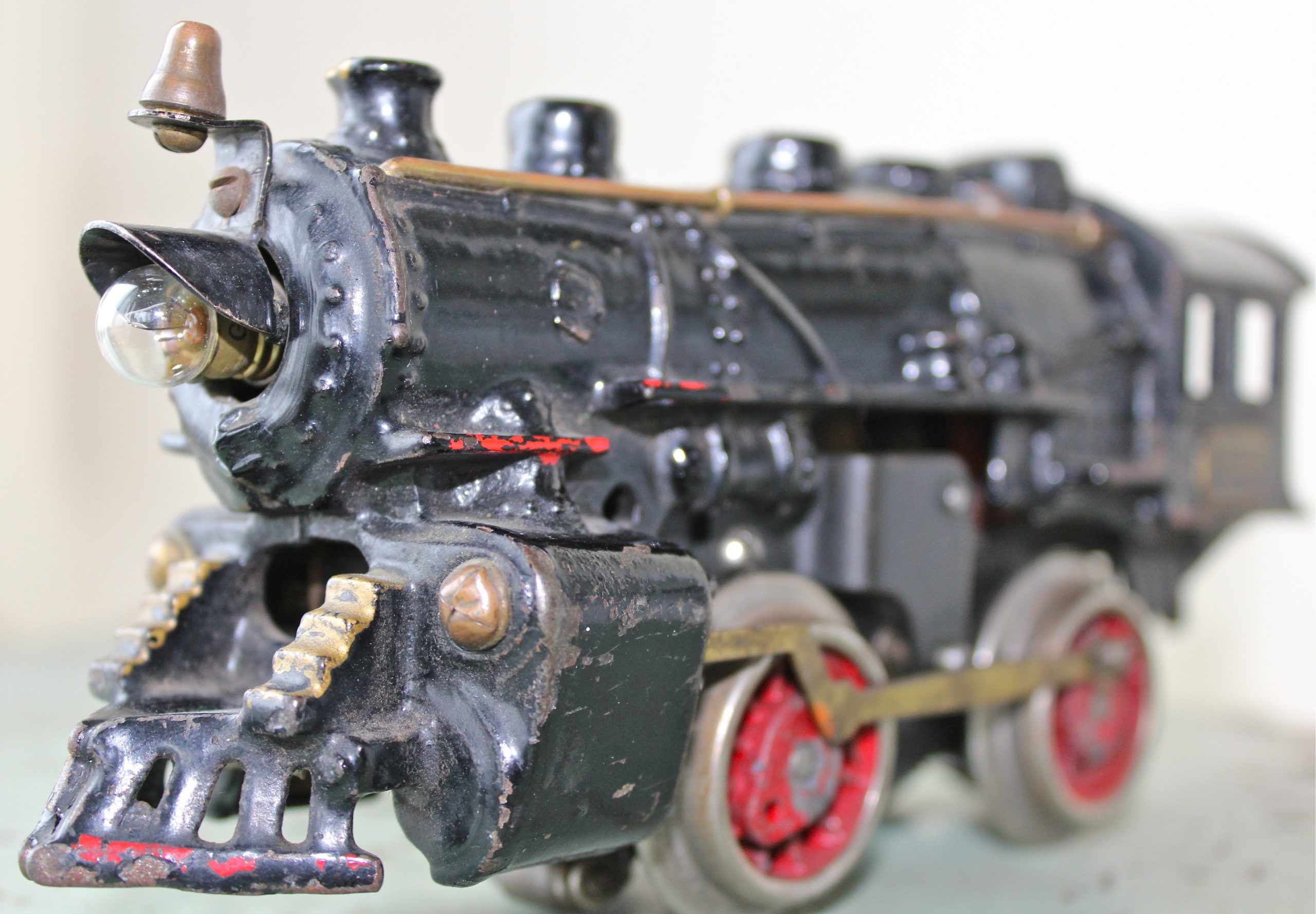

Museum Artifact: Wide Gauge “Pocahontas” Electric Model Train Set with No. 4637 “Shasta” Locomotive, c. 1928, and O-Gauge Cast Iron Locomotive No. 3195, c. 1930.

Made by: American Flyer MFG Co., 2229 S. Halsted St., Chicago, IL [Pilsen]

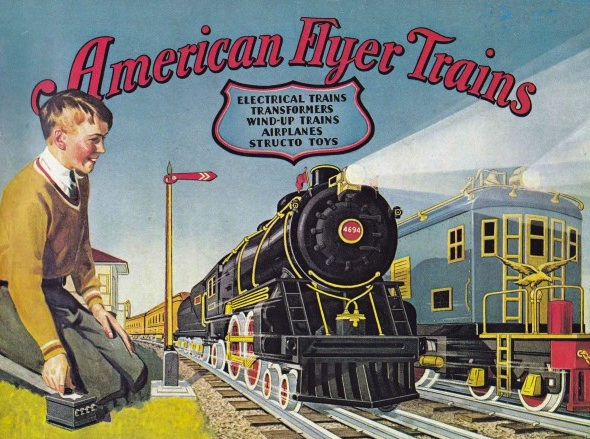

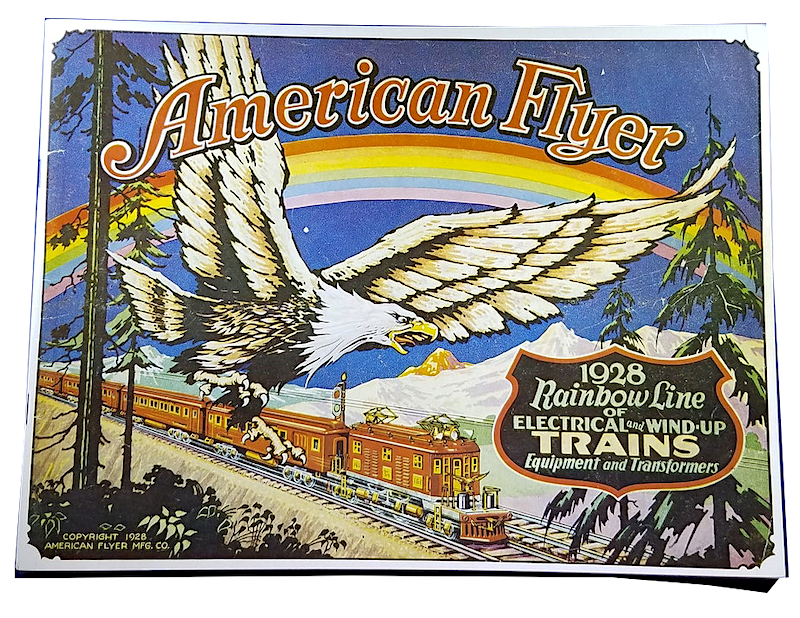

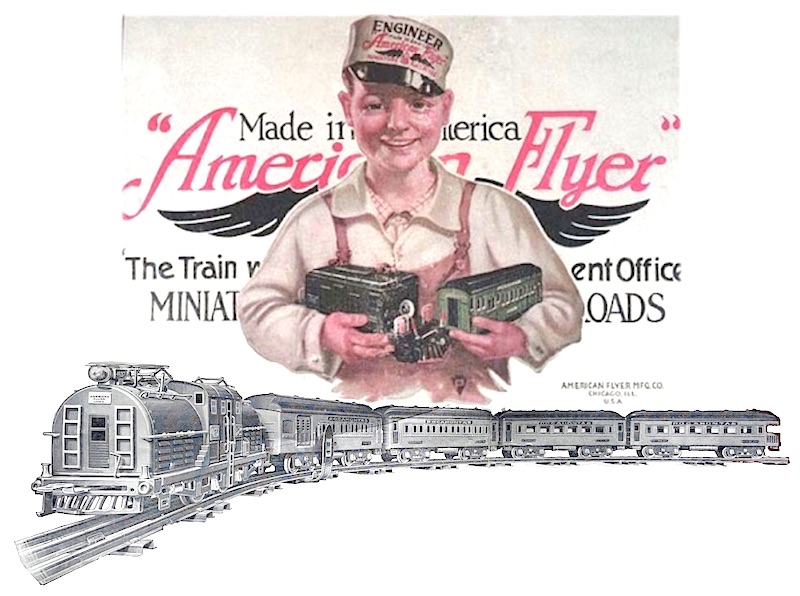

“Just Like Real Trains: The new 1928 American Flyer Rainbow Line radiates an atmosphere of supreme quality. Its exquisite beauty, realistic design, and skillful workmanship will instantly capture your admiration. Compare them with the real thing—their brilliant colors, their size*, their fun-making features, and their performance. Yes, indeed, they are Model Trains!” —American Flyer promotional pamphlet, 1928

The marketing team might have gotten a little overzealous asking customers to compare the actual “size” of a 14-inch toy passenger car to that of a “real” 74-foot Pullman coach, but otherwise, the crux of their sales pitch still holds up.

By any reasonable assessment, the pre-WWII electric train sets produced in Chicago by the American Flyer Manufacturing Company are absolute marvels of miniature engineering, built from heavy cast iron and pressed metal, and tricked out with all the literal bells and whistles—inspired directly by the iconic full-size designs of America’s last great railroading epoch.

By any reasonable assessment, the pre-WWII electric train sets produced in Chicago by the American Flyer Manufacturing Company are absolute marvels of miniature engineering, built from heavy cast iron and pressed metal, and tricked out with all the literal bells and whistles—inspired directly by the iconic full-size designs of America’s last great railroading epoch.

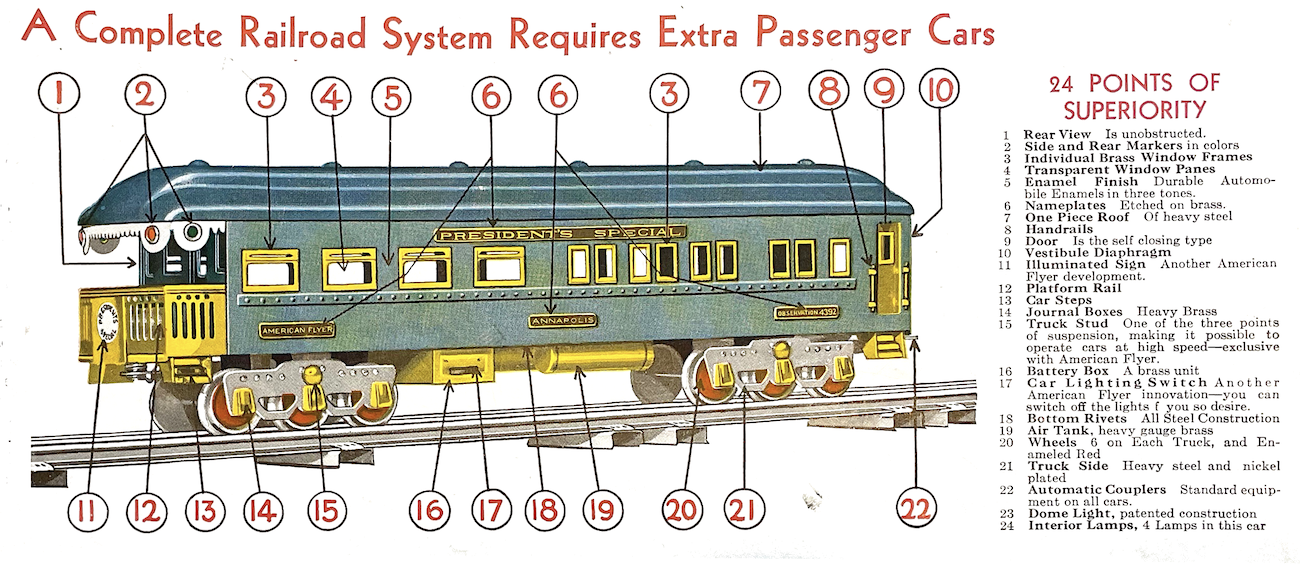

The 1928 “Pocahontas” set in our museum collection, kindly donated by the William Kirsch family, is a great example of the company at its ambitious peak, just before the onset of the Great Depression. The extra-large, wide gauge (aka standard gauge) set features a hefty 0-4-0 St. Paul-style “Shasta” locomotive, “gigantic in appearance and powerful enough to pull the four 14″ cars (Club, Pullman, Diner, and Observation) at a very high rate of speed,” according to the pamphlet that came with it. The loco and cars measure a whopping 6’7″ in length when coupled, and are “beautifully finished in a very attractive color combination of elegant green and rookie tan . . . with a dazzling display of solid brass trim.”

[Components and accessories from the 1928 American Flyer “Pocahontas” set in our museum collection. Items courtesy of the William Kirsch family.]

Like all AF sets, the Pocahontas was promoted as “The Toy for the Boy,” but the focus on detail—including authentic Pullman design features, multi-directional lighting, automatic locomotive bell, opening doors, and remote operated reverse feature—suggests that the company already anticipated an emerging market of grown-up model train enthusiasts . . . a demographic which now helps to keep remarkable relics like these from disappearing entirely. [They’re also the reason Lionel Trains produced a complete reproduction of the Pocahontas set in 2012].

In terms of financial success, the golden age of American Flyer arguably doesn’t start until 10 years after the Pocahontas, in 1938, when the famed toy magnate A. C. Gilbert bought the struggling company and moved it from Chicago to New Haven, Connecticut. Gilbert, a former Olympic pole vaulter and professional magician, had made his toy-making fortune as the inventor of the Erector Set back in the 1910s. Now, as the new boss of American Flyer, the distinguished Renaissance Man would help roll out many of the brand’s most popular designs during the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s. Collectors call it the “post-war era,” but unfortunately for our purposes, it could also be called “post-Chicago.”

We’ll leave it to the Made-in-New-Haven Museum to tell the tale of A. C. Gilbert’s American Flyer. Our focus, instead, will stay on the first 30 years, aka “Pre-War,” when a humble Chicago company helped plot the course of the 20th century model train phenomenon.

[The No. 3195 locomotive is also part of our museum collection, introduced in 1930. A much smaller O-gauge model (rather than wide gauge), this was one of the last cast iron models American Flyer made before shifting to cheaper materials and ultimately leaving Chicago for Connecticut]

History of American Flyer, Part I: Pre-War (as in, World War I)

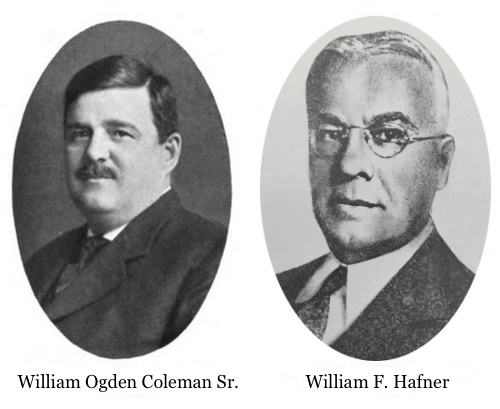

The Chicago portion of the American Flyer saga begins with a toymaker named William Hafner. For the first decade of the 20th century, Hafner was trying to carve a niche for himself as a builder of miniature clockwork / wind-up automobiles and trains, first under the Toy Auto Company name, then the W. F. Hafner Company, both at 9 South Canal Street. He was consistently outclassed, however, by imported German models and the top American competitor—the Ives Manufacturing Company of Connecticut.

In 1907, hoping to step up his game, Hafner partnered with a well-to-do friend named William Ogden Coleman—president of the Burley & Tyrrell Co., a china and glassware importer. According to some versions of the tale, Hafner may have owed Coleman some money from earlier unknown dealings, and rather than funnel his meager train earnings into debt repayment, he proposed a new arrangement.

In 1907, hoping to step up his game, Hafner partnered with a well-to-do friend named William Ogden Coleman—president of the Burley & Tyrrell Co., a china and glassware importer. According to some versions of the tale, Hafner may have owed Coleman some money from earlier unknown dealings, and rather than funnel his meager train earnings into debt repayment, he proposed a new arrangement.

Going forward, Hafner would give Coleman a controlling interest in his toy line, if Coleman merely lent him some manufacturing space. “Once I get production up, I can get distribution from Montgomery Ward, and we’ll be off and running!”

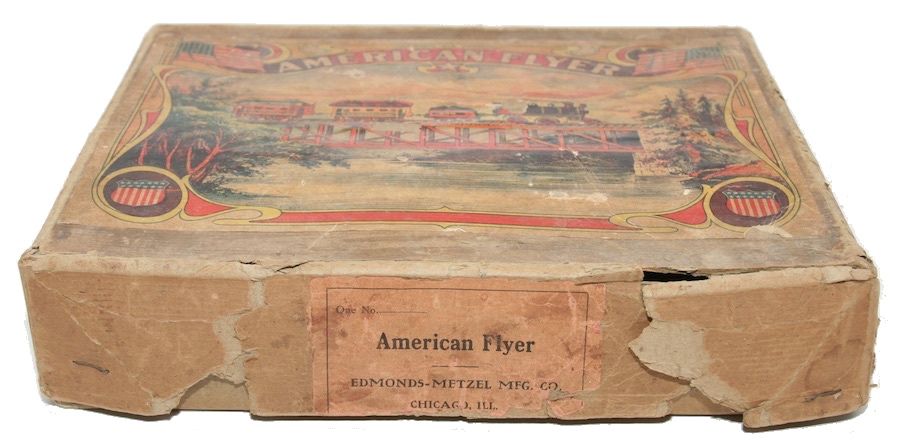

Maybe it wasn’t the most wildly convincing proposal in the world, but timing wise, it was fortuitous. A year or two earlier, W. O. Coleman had acquired a small, underperforming Chicago hardware business, the Edmonds-Metzel MFG Co., which had an established factory at what is now 2609 W. Wilcox Avenue. It wouldn’t require much effort to add a small toy production line to the plant.

[1905 ad for the Edmonds-Metzel MFG Co., which would later birth American Flyer]

[1905 ad for the Edmonds-Metzel MFG Co., which would later birth American Flyer]

Coleman, himself, had no interest or time to commit to toy trains, but he was willing to take on Hafner as a low risk / high reward investment. He was basically telling Hafner, “I’m gonna leave you to it. Show me what you can do.”

Once the ink had dried, a decision was also reached to re-brand the model trains, not under the established Hafner name, but with an identity more befitting the times; something patriotic and appealing to a target demographic of ambitious young boys.

And so the “American Flyer” line was born, initially as a brand only, with production still credited to the Edmonds-Metzel MFG Company. It didn’t take long, however, for Hafner’s little toy operation to start eclipsing the primary hardware business going on around it.

[A rare 1908 American Flyer train set still showing the Edmonds-Metzel MFG Co. name; image courtesy of the Fairchild Collection]

[A rare 1908 American Flyer train set still showing the Edmonds-Metzel MFG Co. name; image courtesy of the Fairchild Collection]

“The best Christmas present for the children is an American Flyer miniature train,” claimed a 1910 advertisement in the Saturday Evening Post. “American Flyer engines are cast iron—not tin—and are modeled after the big engines you see on the most up-to-date railroads. The best quality springs, not the breakable kind, are used and they will stand the roughest kind of usage. . . The cars are all American models, beautifully painted and decorated in bright colors baked on so hard that even the baby can’t get them off.”

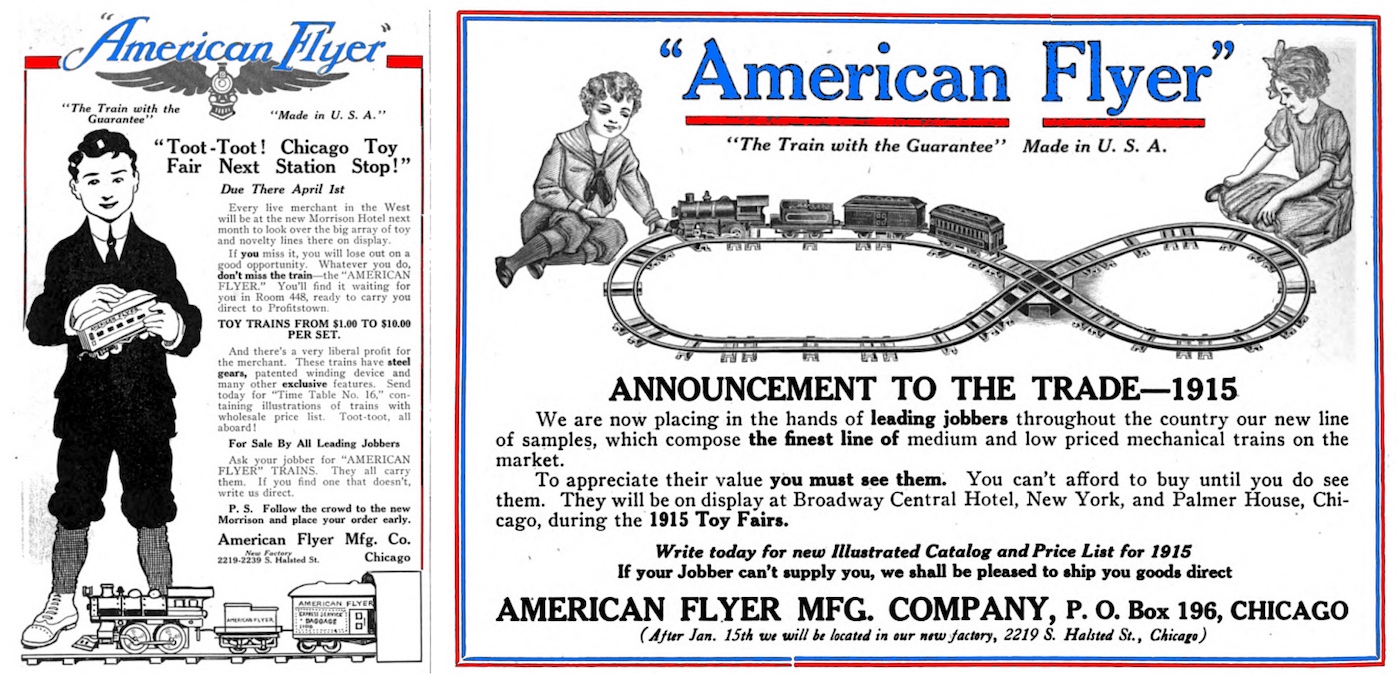

There were only about a dozen workers assembling the entire American Flyer line-up in 1910, but William Hafner was delivering on his promise, as listings in the mail order catalogs of Montgomery Ward (among others) enabled AF’s budget-priced “O-gauge” train sets to make up ground on the industry leader, Ives, and an emerging competitor, Lionel.

During this same period, a fire at the Edmonds-Metzel plant had forced William Coleman to re-assess his various properties, and the decision was made to scrap the old hardware business entirely. Moving into to a shared plant at 1920 West Kinzie Street, the train operation was officially re-organized as the American Flyer Manufacturing Company in 1910, with Hafner as vice president and Coleman as president.

During this same period, a fire at the Edmonds-Metzel plant had forced William Coleman to re-assess his various properties, and the decision was made to scrap the old hardware business entirely. Moving into to a shared plant at 1920 West Kinzie Street, the train operation was officially re-organized as the American Flyer Manufacturing Company in 1910, with Hafner as vice president and Coleman as president.

Within another few years, American Flyer was already outgrowing the Kinzie plant and looking to expand significantly. Sales were strong and competing German imports were weakening as the Great War began overseas. Hafner and Coleman should have been enjoying the spoils of their profitable partnership. But, as often happens in these situations, fast success only seemed to escalate the disharmony within the company hierarchy, as the usual mix of pride, greed, and philosophical differences gradually poisoned the stew.

As the owner of the business, William Ogden Coleman was the biggest beneficiary of its ascendence. “And why not?” he might have said. “I had the wisdom to make the investment.”

William Hafner, meanwhile, was still the architect of the American Flyer brand, and as such, may have begun to see Mr. Coleman as more of hindrance than a help as time went on. Beyond serving as the company’s creative force, Hafner supposedly wanted more say in how it was operated and, understandably, a bigger salary to go with it. A classic power play was afoot.

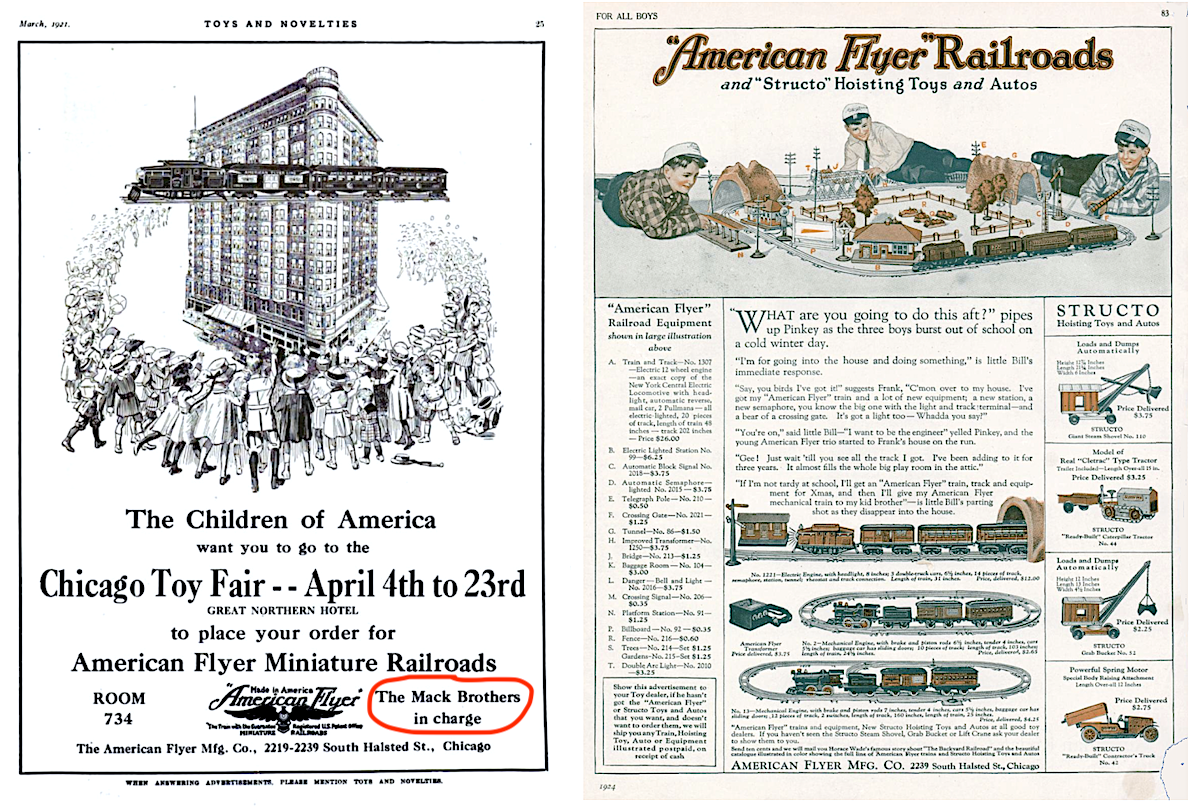

[American Flyer ads promoting appearances and upcoming toy fairs in 1915, the company’s first year without co-founder William Hafner]

[American Flyer ads promoting appearances and upcoming toy fairs in 1915, the company’s first year without co-founder William Hafner]

II. Split Switch

If toy train A is traveling east at 60 mph, and toy train B is traveling west at 45 mph, how much money will toy train A be willing to share with toy train B when their business partnership becomes successful? The answer: Not enough.

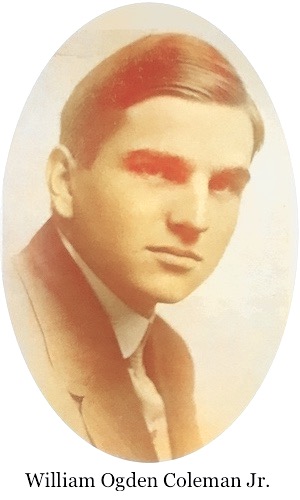

When Coleman balked at giving Hafner a bigger share of the company—and instead seemed to be considering his son, William Ogden Coleman Jr., for a leadership position—an annoyed Hafner took drastic action. He cut bait entirely and went back to the independent ranks, starting up his own toy train company while leaving all his old designs and patents behind.

When Coleman balked at giving Hafner a bigger share of the company—and instead seemed to be considering his son, William Ogden Coleman Jr., for a leadership position—an annoyed Hafner took drastic action. He cut bait entirely and went back to the independent ranks, starting up his own toy train company while leaving all his old designs and patents behind.

The Hafner Manufacturing Co. launched in 1914 and would survive until 1951—but it was always a bit of an also-ran in the industry, sticking with the same basic clockwork designs at cheap prices.

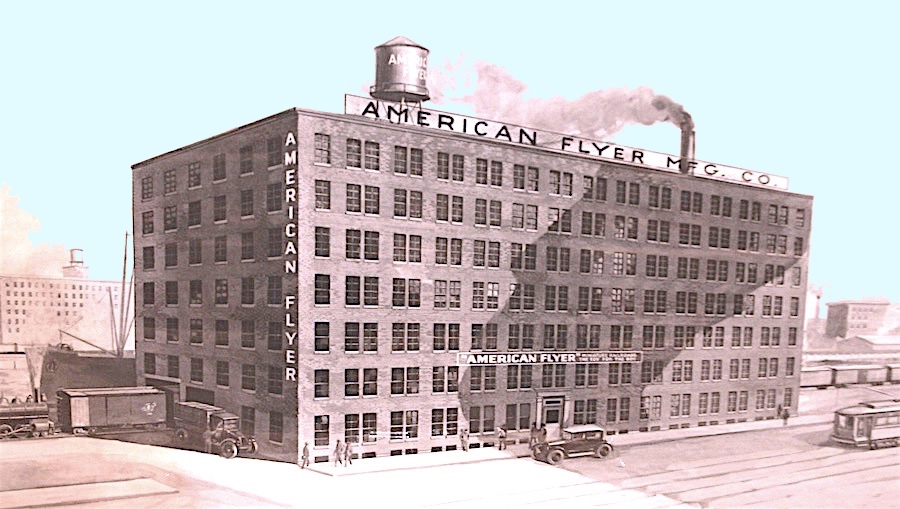

From the looks of it, the Coleman-Hafner break-up played out much like a real divorce, as Coleman moved American Flyer to a glorious new seven-story factory at 2229 S. Halsted Street in Pilsen [pictured below], while leaving Hafner the keys to their old home. For its first few years, Hafner MFG was listed at 400 N. Lincoln St., which is modern day Wolcott Ave, on the intersection of Kinzie Street—i.e., the former American Flyer plant.

[Above: Artist rendering of the American Flyer factory in Pilsen, 2229 S. Halsted Street, which opened in January of 1915. Courtesy of Fairchild Collection. Below: Employees standing outside the same plant, c. 1920.]

Just four years after that drama played out, William Ogden Coleman, Sr. died of a heart attack at 54, putting the company in the hands of his 26 year-old son W. O. Coleman, Jr.—who’d already been serving as American Flyer’s president since graduating college.

Junior preferred the mechanics of the model train business to the relative dullness of his dad’s chinaware company anyway, and as a result, Burley and Tyrrell was promptly sold off to Albert Pick & Co., leaving American Flyer as the new central focus of the Coleman family business.

Junior preferred the mechanics of the model train business to the relative dullness of his dad’s chinaware company anyway, and as a result, Burley and Tyrrell was promptly sold off to Albert Pick & Co., leaving American Flyer as the new central focus of the Coleman family business.

Coleman, Jr., while green, was a well liked young executive who immediately ushered in American Flyer’s entry into the electric railroad era in 1918. This was an enormous shift in the industry for obvious reasons, as child conductors (the ones from wealthy enough families, at least) could now watch their choo-choos tear around the track for hours without having to stop and re-wind them. For Coleman, there was a higher, patriotic purpose to this increasing realism.

“The manufacturer in America is cooperating with all other educational means and institutions in developing the peculiar bent of youth toward some science or profession,” he told Fort Dearborn Magazine in 1920. “No foreign manufacturer can do this for us, because behind the success of the toy lies the psychology of the American boy.”

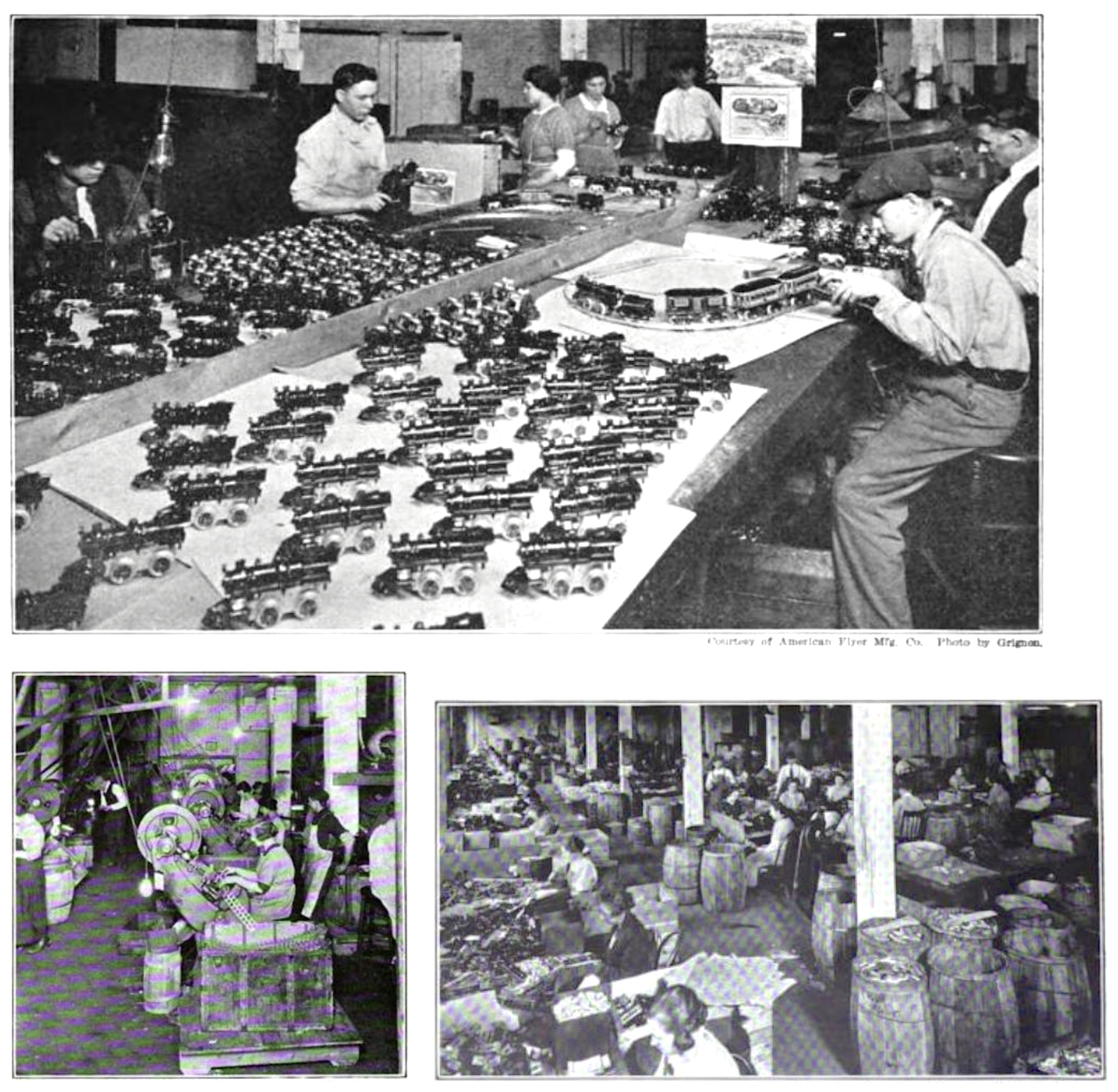

By the holiday season of 1920, with demand growing and machine automation improving efficiency, the Halsted factory was the world’s biggest producer of model trains, completing 6,000 complete sets per day, along with 5,000 sections of track.

“As the miniature cars take shape before one’s eyes,” Fort Dearborn Magazine recounted after touring the plant, “it is amusing to note the professional air which they wear, labeled as they are with the names of the great railway systems of America, the express companies, and in some cases even with the names of the great packing plants using cattle cars or refrigerating cars. Pullman sleepers are of course in evidence, as are also freight cars, coal tenders, etc. In short, almost all kinds of rolling stock are represented.”

Along with a team of increasingly skilled electricians and engineers, William Coleman, Jr., was aided by some other capable leaders during these years, including his cousin / superintendent Harry Becker and a couple ace sales managers named Roy and Herman Mack.

[Inside the American Flyer factory, 1920. Top: Testing out new engines. Bottom Left: Machining car wheels from strips of steel. Bottom Right: Assembly room.]

III. “The Mack Brothers In Charge”

Just about any version you find of the American Flyer story includes the names of William Ogden Coleman (father and son), William Hafner, and A.C. Gilbert. But the Mack Brothers, for whatever reason, are rarely discussed in any detail. You can only find hints of just how significant they were in keeping the company afloat and moving forward in the years following the double-whammy of Hafner’s departure and Coleman Sr.’s death.

Herman F. Mack (1872-1957) and his little brother Roy (1885-1945) were first generation Americans of German stock. They were both born in Appleton, Wisconsin, with the original surname “Knitt.” After Herman moved to Chicago and got work in a bicycle factory in the 1890s, he met and married a gal named Mary Mack, and for unknown reasons, eventually adopted her last name in place of his own in the 1910s. Maybe he was super progressive, or more likely, as a traveling salesman during World War I, he found it beneficial to conceal his German roots (he was NOT, incidentally, the same Herman Mack who ran the Lexington Hotel in Chicago during this same period).

Herman F. Mack (1872-1957) and his little brother Roy (1885-1945) were first generation Americans of German stock. They were both born in Appleton, Wisconsin, with the original surname “Knitt.” After Herman moved to Chicago and got work in a bicycle factory in the 1890s, he met and married a gal named Mary Mack, and for unknown reasons, eventually adopted her last name in place of his own in the 1910s. Maybe he was super progressive, or more likely, as a traveling salesman during World War I, he found it beneficial to conceal his German roots (he was NOT, incidentally, the same Herman Mack who ran the Lexington Hotel in Chicago during this same period).

When kid brother Roy moved to the city and joined Herman, he dutifully changed his name, as well, and the “Mack Brothers” were soon employed as William Coleman Jr.’s trusted sales department heads, and ostensibly the public faces of the American Flyer brand during its best years in Chicago.

Besides traveling around the world as AF ambassadors in the ’20s, the Macks also represented the company at numerous stateside toy fairs and conventions, often meeting directly with rowdy crowds of train-obsessed railway children. Advertisements for these events would routinely say, quite directly: “As usual, the Mack Brothers will be in charge.” A 1921 ad in the brothers’ hometown paper, the Appleton Post-Crescent, suggests even greater involvement in the product: “It might interest you to know that these, America’s best toy trains, are made by a former Appleton man, Mr. Herman Mack.”

[Left: 1921 ad for “American Flyer Miniature Railroads” at the Chicago Toy Fair, with “the Mack Brothers in charge.” Right: 1924 ad showing American Flyer cross-selling its trains with hoisting toys and cars made by the Structo Toy Co. of Freeport, IL]

The Macks had some good fortune on their side; showing off new electric trains and taking over marketshare in a post-war bull market wasn’t too much of a chore. But they eclipsed expectations, nonetheless. In the ’20s, American Flyer routinely sold over half a million trains per year, and the Pilsen factory grew to employ over 150 workers.

By now, the company’s fiercest foe was Lionel Trains out of New York, and various strategies were taken to try and compete with them. In 1923, for example, Coleman and the Macks worked out a sort of alliance with the Structo Toy Company of Freeport, Illinois, becoming a distributor for Structo’s metal construction toys and automobiles, which were then promoted as complementary pieces to American Flyer railroad set-ups. It was a smart way to diversify the product line without having to expand manufacturing capabilities.

Two years later, as a direct answer to Lionel’s popular oversized “standard gauge” trains, AF debuted its own “wide gauge” line, and by 1928, they’d scrapped lithography to go with embossed, individually painted train cars with brass detailing. Despite the greater expenses this created on the front end, all of the American Flyer train sets in the so-called “Rainbow Line”—including the Pocahontas, Mountaineer, Statesman, Merchant, Ambassador, and elite President’s Special—ranged from about $25 to $75 in price; still well below that of Lionel’s comparable offerings.

Two years later, as a direct answer to Lionel’s popular oversized “standard gauge” trains, AF debuted its own “wide gauge” line, and by 1928, they’d scrapped lithography to go with embossed, individually painted train cars with brass detailing. Despite the greater expenses this created on the front end, all of the American Flyer train sets in the so-called “Rainbow Line”—including the Pocahontas, Mountaineer, Statesman, Merchant, Ambassador, and elite President’s Special—ranged from about $25 to $75 in price; still well below that of Lionel’s comparable offerings.

Interestingly, during this same period, from 1928 to 1930, American Flyer also joined forces with Lionel for a fleeting moment, as the two companies agreed to co-scavenge the bankrupt Ives MFG Co.—the fallen, former giant of the industry—and split ownership of its remaining inventory.

With the collapse of the stock market, however, such honor among thieves was quickly out the window.

[Anatomy of an American Flyer “President’s Special” passenger car, from the 1934 catalog]

The “Toy for the Boy” Grows Up

Sales had already started to slow at American Flyer during the Ives take-over, and as the Depression set in, W.O. Coleman, Jr. was forced to make sweeping cuts to staff and materials. As a particular blow, the Mack Brothers were either let go or jumped ship, eventually landing with the Hafner MFG Co., to add insult to injury (weirdly, a company called “Mack Brothers” also surfaced at 2041 W. Chicago Avenue and would go on to offer repair services on model railroads and other electronics for decades, but it was led by a John Edward Mack, no relation). American Flyer was also forced to sell its Ives holdings to Lionel, sending Coleman back to the drawing board as the 1930s loomed.

To expand sales, American Flyer could have gone back to targeting both girls and boys, as they’d done when Hafner was still on the team. But rather than imagine any young lady taking interest in anything transport oriented, the company only offered them a couple of odd, unrelated products in the catalog: a mini typewriter and a “practical working loom.” With the gals thus taken care of, the design team looked at the company’s 20-year history and decided its best new audience would be the men who already grew up playing with toy trains . . . i.e., the boys of the past.

To expand sales, American Flyer could have gone back to targeting both girls and boys, as they’d done when Hafner was still on the team. But rather than imagine any young lady taking interest in anything transport oriented, the company only offered them a couple of odd, unrelated products in the catalog: a mini typewriter and a “practical working loom.” With the gals thus taken care of, the design team looked at the company’s 20-year history and decided its best new audience would be the men who already grew up playing with toy trains . . . i.e., the boys of the past.

“Let your Dad, or your Uncle, in on your plans,” the 1933 catalog suggested to its young readers. “Show them this catalog, and the illustration of the model you desire. They’ll have as much fun running the train as you will.”

The 1935 catalog went further: “Many boys who are now grown up received their first lessons in management, electricity, engineering, and resourcefulness through the operation of their American Flyer trains. That’s why it’s so important that you should have the most advanced and best equipped train made.”

With this shift to a wider, slightly more adult audience in the ’30s, realism was more important than ever, with nostalgia not far behind.

Locomotive model No. 3195, as seen in our museum collection, was a good example of this retro campaign. Introduced in 1930, it was American Flyer’s first proper steam engine in six years, and it holds up today as a premium O-gauge (aka narrow gauge) model, made of heavy-duty cast-iron rather than zinc die-cast. Compared to some of the other budget priced O-gauge lines, it’s more like a little work of art than a mere toy—harking back in a way to William Hafner’s earliest locomotive designs. With a ringing bell, functioning headlight, and remote control, though, it was still vibrant and noisy enough to impress the kids of the “modern age.”

[There’s something inherently sad about a solitary steam engine—even a toy one. With no tender, it has no imaginary fuel, and with no boxcars, it serves no imaginary purpose. Our particular locomotive doesn’t even have a lonesome whistle to blow.]

Designs like the #3195 really did come along at an undeniable crossroads (pun intended) in American Flyer’s history. On one hand, it was a return to form—steam, cast-iron, weighty, and sophisticated. On the other, it was the last gasp of a bygone era. By 1932, AF had abandoned cast iron for good and transitioned fully to cheaper sheet metal and die-casting.

Stylistically, the company also responded to the country’s growing fascination with new “Streamliner” trains (like the famed California Zephyr) by focusing almost all their attention on that trend in the midst of the Depression.

In 1936, American Flyer’s general manager James E. Cuff told the Tribune that “installation of streamliners by the railroads has resulted in a sharp revival of interest in model trains,” and that streamliner sales now accounted for 90% of AF’s business, with old style steam locos pushed to the back room. Sales were good, but on the down side, the company had to invest in the installation of new equipment to manufacture the new deco-tastic trains. In the economic realities of the time, it was a death blow disguised as a comeback.

By 1938, Coleman, Jr. had finally seen enough. He sold the business to A.C. Gilbert and closed the Pilsen factory for good.

That once bustling North Side plant, which you might call a miniature version of the old Pullman Works down on the South Side, is still standing today, just off the Dan Ryan Expressway. Its seven story height, however, has since been reduced to just three after taking on fire damage in the 1950s. The building was purchased by a real estate firm in 2009 for just $2.6 million, then sold in 2017 to SEIU Healthcare for a sweet $17.7 million. It’s highly unlikely, after 80 years, that any recognizable remnants of the old American Flyer operation have been preserved therein.

[The former American Flyer plant at 2229 S. Halsted St., still standing, though at half the original height]

[The former American Flyer plant at 2229 S. Halsted St., still standing, though at half the original height]

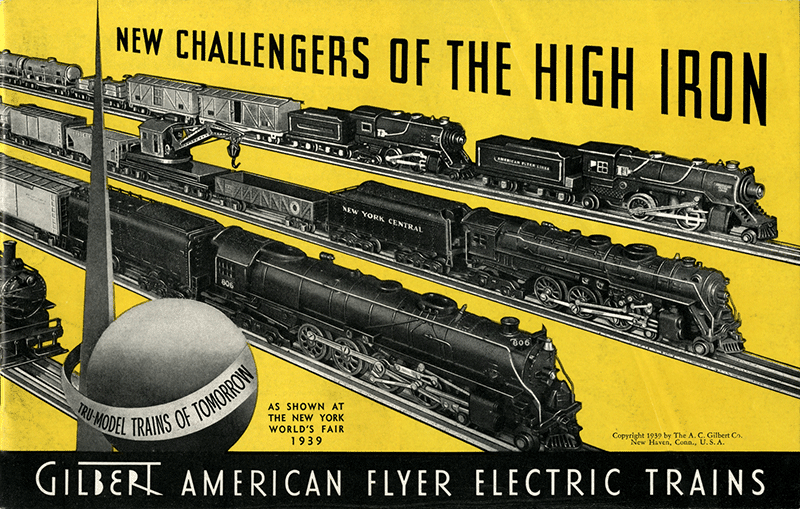

[Early Gilbert era American Flyer ad one year after move to New Haven, CT, 1939]

Sources:

“The Colemans and American Flyer,” by Hilly Lazarus, 1985

“Chicago as a Maker of Christmas Toys” – Fort Dearborn Magazine, Dec 1920

American Flyer catalogs: 1933, 1935, 1936

“New Trains Lead in Demand for Christmas Toys” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 14, 1936

Archived Reader Comments:

“The photo of the locomotives being assembled is not in Chicago but rather after A.C. Gilbert shifted production to New Haven. The 3/16” Scale Atlantic locomotives may have been designed in Chicago but they were tooled and produced in New Haven. They were at first three rail “O” gauge and after the war they were modified for two rail “S” Scale gauge.” —Charles Vik, 2019

“As someone who knows this stuff like the palm of my hand, this article is astonishingly accurate.

What is standard in such journalism is usually. flowery irrelevance: the writer attempting to showcase their “skill” at the expense of the story. This was well done. One thing that I would add is that to the advanced collector, the most desirable of all Flyer trains are the earliest Chicago, or “Metzel”, trains, not the stuff that came after.” —Umoja, 2019

Hello:

I am looking to sell or find a good home for a few pre-war American Flyer train cars and track pieces.

They have been in the family for a long time.

I live in Schaumburg, IL

(1) 1686 STREAMLINED 2-4-4 LOCOMOTIVE

(1) 1686 STREAMLINED TENDER + CARTON

(1) 3207 GONDOLA + CARTON

(1) 3208 FREIGHT CAR + CARTON

(1) 3211 CABOOSE + CARTON

(16 PIECES) STRAIGHT TRACK

(22 PIECES) CURVED TRACK

Please let me know, thanks.

I have multiple box cars and 1 caboose plus accessories. It’s American flyer presidential series that has been in my family for over 50 years. How do I sell and get the best price?

I would be interested call me at 703-314-9675 or email justinp1821@gmail.com

Wow…What a find! I just was gifted a pre war American Flyer train with cars. To me it looks like it’s in serviceable condition but I just contacted Hennings yesterday ( I didn’t know they existed before yesterday) and I’ll be driving there on Tuesday to get the engine in workable shape including some needed remanufactured parts. The engine alone without the coal tender is 11 lbs!

I will be reading carefully through this entire article. This is not just the history of a great American company, it’s part of our American History!

I have a complete set pre war in individual boxes with tissue paper. The entire set is in its original box.

Would you be interested in selling. Thx ! Let me know. 480 444-9139. Gimme a jingle let’s talk!

I am trying to find an all original set box and/or original eagle for my prewar 1929 American Flyer President’s Special that I recently purchased. Please let me know if you know of either of these for sale.

Hi I found this tin sign in a old house I was cleaning out but can’t seem to find any information on it. Can you offer any insight on this and or maybe what the value of it is. Thank you

To answer the I W Weiss comment, Hennings Trains in Lansdale, PA (AKA Model Engineering Works) makes reproduction wheels for the steam engines. I believe they may be able to service the engines also.

Fascinating history / great article about Chicago’s American Flyer trains!

In my own train collection, the cast-metal components of nickel-rimmed O-gauge American Flyer locomotive drive wheels have become corroded, cracked, and swollen with eight decades of aging. The motor on this locomotive is “like-new”.

Can you recommend any manufacturers or service shops that can replace these wheels and mount them on the original steel axles?

Thank you

Hello. Is anyone making the rods, for the driving wheels for a pre-war #3195 engine? Thanks

Side rods source:Suggest you try HenningsTrains.com, Landsdale PA, since they acquired rights to now closed MEW (Model Engineering Works) parts manufacturing. Hennings are a good bunch to work with, now mostly online sales due virus, but in business 80 years..

I found a small engine on the side it says American five any info on year and parts