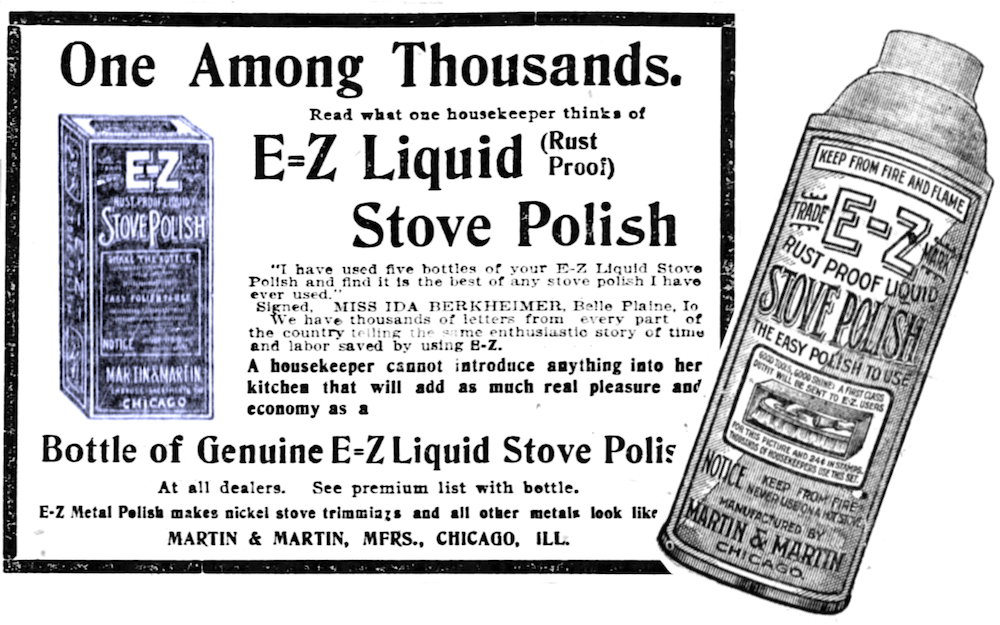

Museum Artifact: E-Z Stove Polish Bottle, c. 1910s

Made By: Martin & Martin, 3005 W. Carroll Ave., Chicago, IL [East Garfield Park]

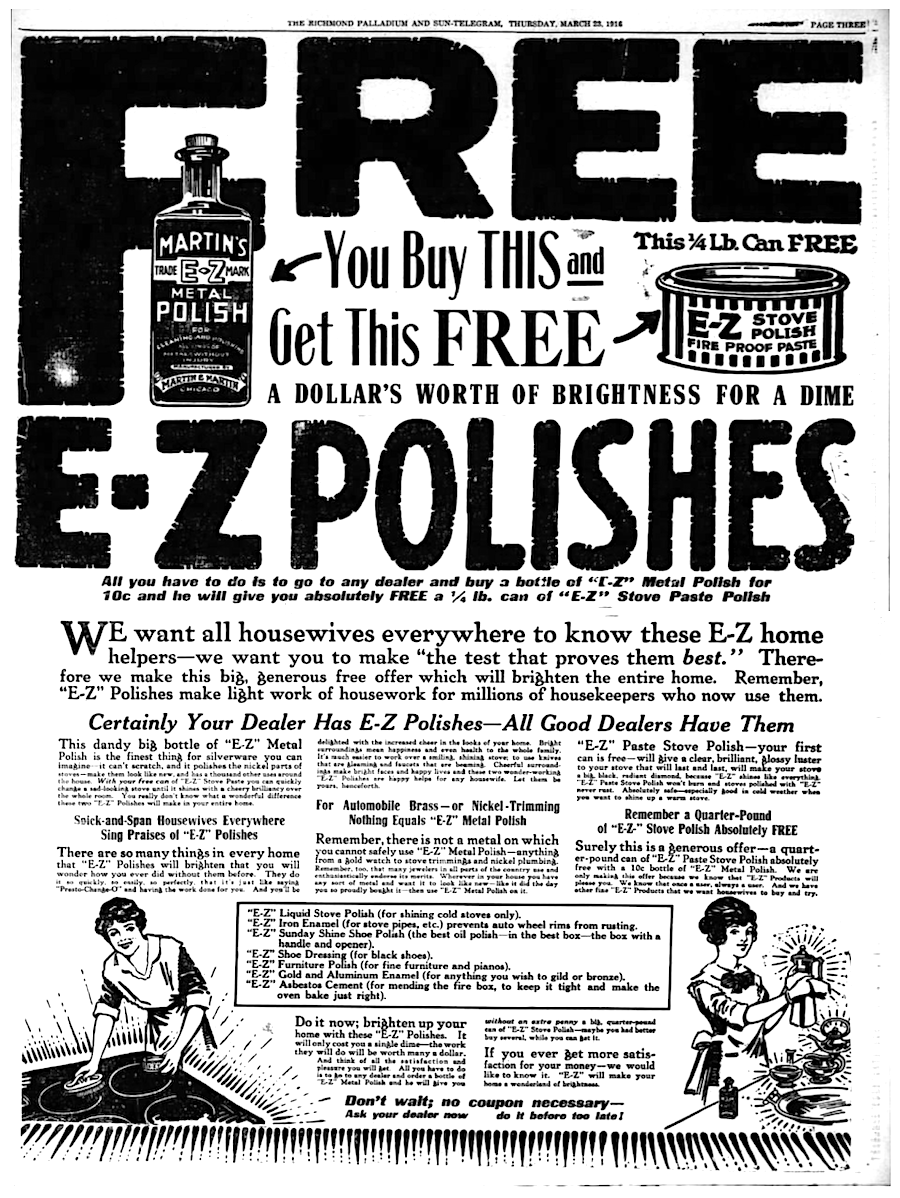

“There are so many things in every home that ‘E-Z’ Polishes will brighten that you will wonder how you ever did without them before. They do it so quickly, so easily, so perfectly, that it’s just like saying ‘Presto-Change-O’ and having the work done for you.” —E-Z Polish advertisement, 1916

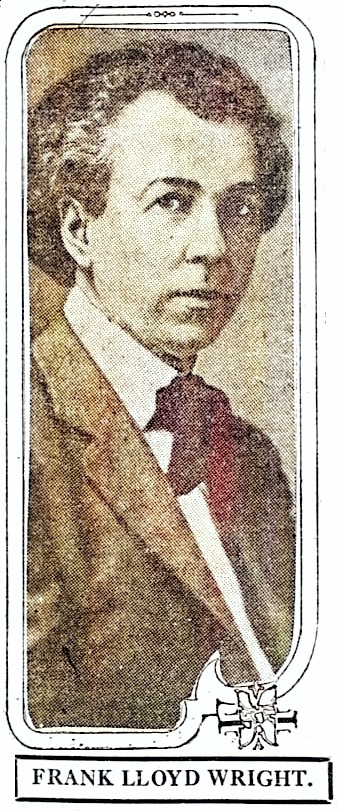

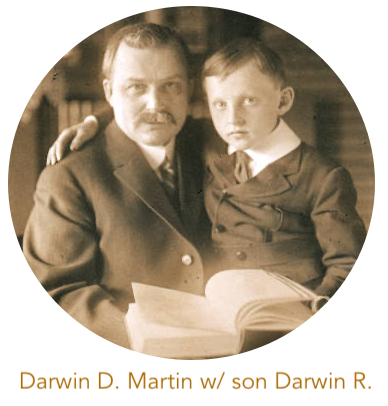

Brothers William E. and Darwin D. Martin were captains of industry in the early 1900s, but it’s not entirely disrespectful to say that they’re remembered today not for their “E-Z” line of chemical polishes, but as supporting characters in the grander life story of America’s most celebrated architect, Frank Lloyd Wright.

Brothers William E. and Darwin D. Martin were captains of industry in the early 1900s, but it’s not entirely disrespectful to say that they’re remembered today not for their “E-Z” line of chemical polishes, but as supporting characters in the grander life story of America’s most celebrated architect, Frank Lloyd Wright.

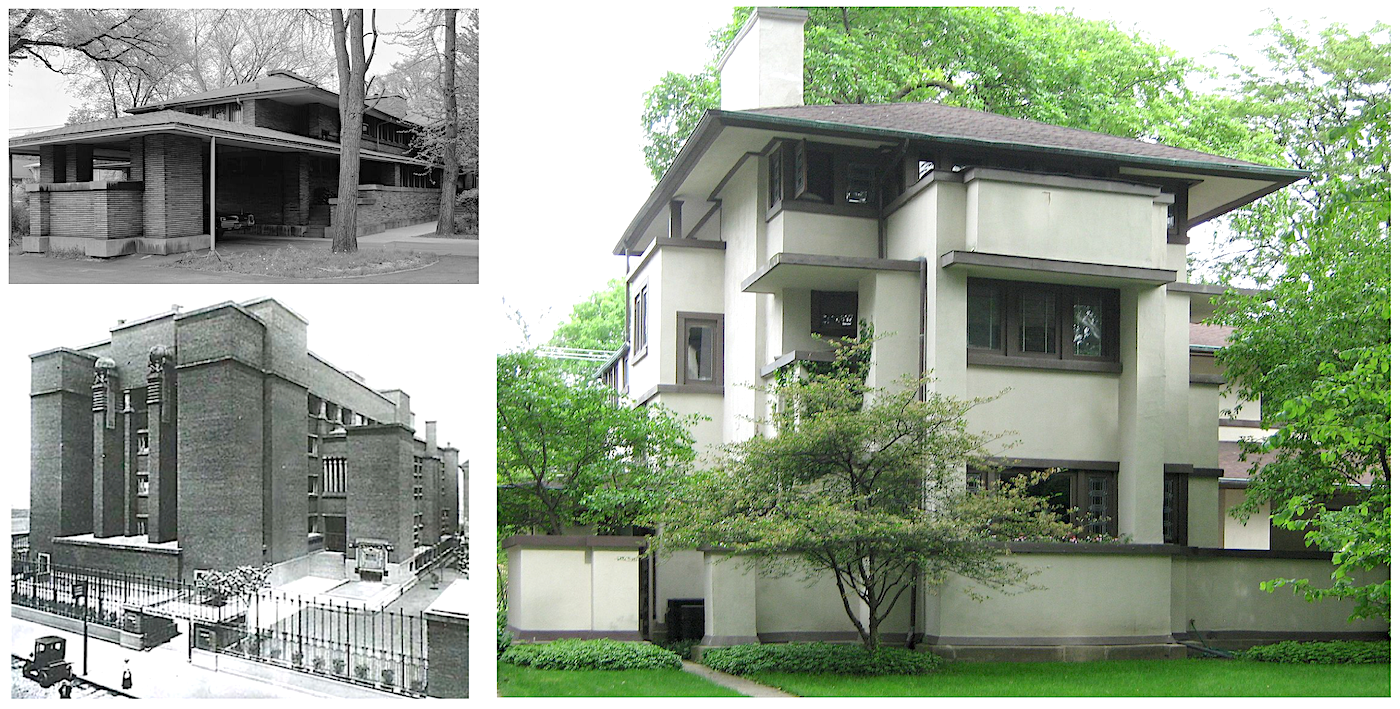

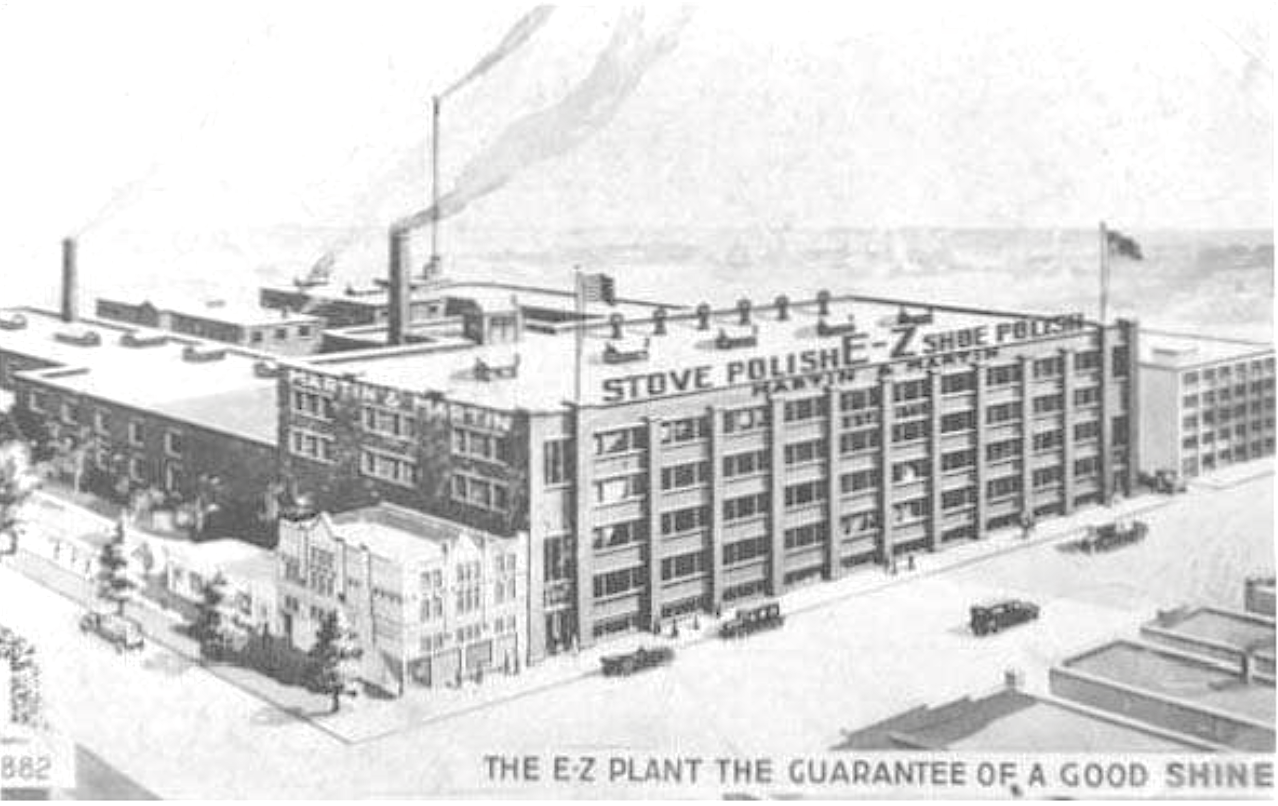

While Wright built the homes of more than a few well-to-do tycoons in the 20th century, his relationship with the Martin family went beyond a one-off contract job. The Martins were early devotees of the Prairie School and vocal believers in the genius of Wright, sending a series of high-profile commissions his way and helping him establish his national reputation. Wright built homes for both brothers (William’s in Oak Park, Illinois, and Darwin’s in Buffalo, New York), and in 1905, he started work on a new factory building for their E-Z Polish business on Chicago’s west side. That building, which is still standing today (albeit in a form the architect wouldn’t recognize), was Wright’s first and last foray into factory design. It was such an unusual project, in fact, that its connection to Wright was temporarily (or intentionally) forgotten for many years, until a researcher “rediscovered” it in the late 1930s.

By that point, the Martin Brothers weren’t around to tell the tale of the factory’s construction. But for most of their adult lives, they were easily among Frank Lloyd Wright’s closest associates and friends, staying in his orbit through the ups and downs of their mutual careers—so much so that it’s hard to separate Martin & Martin, the manufacturers, from the buildings that were built for them.

Of course, like just about everyone else who had regular dealings with the surly Mr. Wright, William and Darwin didn’t always see eye to eye with the man, nor did their loyalty necessarily yield an equal return. As a story unto themselves, though, the Martins are an intriguing pair—self-made men of the Gilded Age who celebrated their industrial success with great monuments to leisure, only to see their fortunes quickly burn away . . . not unlike the unsuspecting housewives who used E-Z Stove Polish near an active flame.

[The E-Z Polish factory at 3005 W. Carroll Avenue in Garfield Park, Chicago. On the left is a colorized version of a photo taken by Gilman Lane, circa 1940, part of the Oak Park Public Library’s collection. On the right is a 2022 view from a similar vantage point]

History of Martin & Martin, Part I: From Soap to Polish

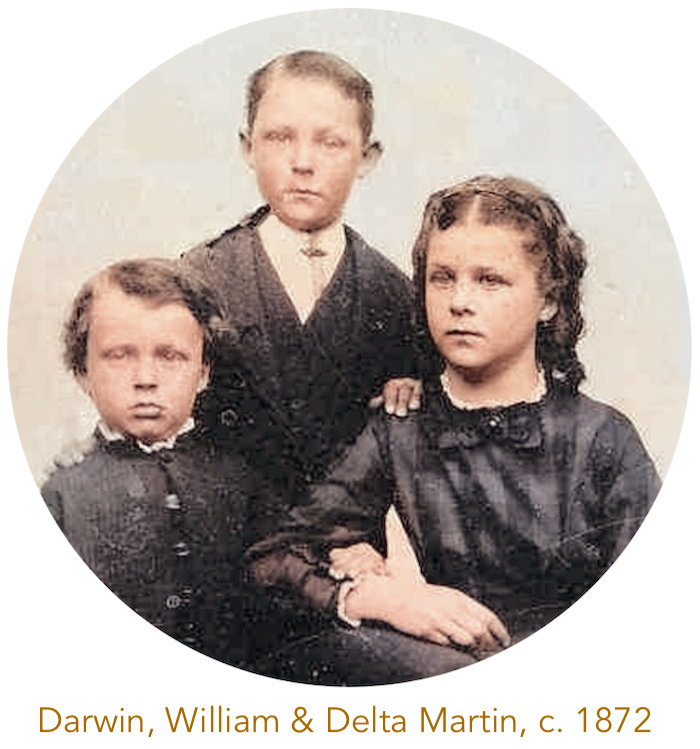

William Everett Martin (b. 1863) and Darwin Denice Martin (b. 1865) were the youngest of five siblings born to Hiram and Ana Martin in Bouckville, New York. This was in the midst of the Civil War chronologically, if a bit on the periphery of the battlegrounds geographically. Before either brother had turned 10, their mother died, leading to a permanent splintering of the family. While the three older Martin siblings all stayed behind in New York, William and Darwin headed west with their father, who remarried and wound up shuffling between several small towns in Nebraska and Iowa, working as a farmer, a cobbler, and a clothing merchant.

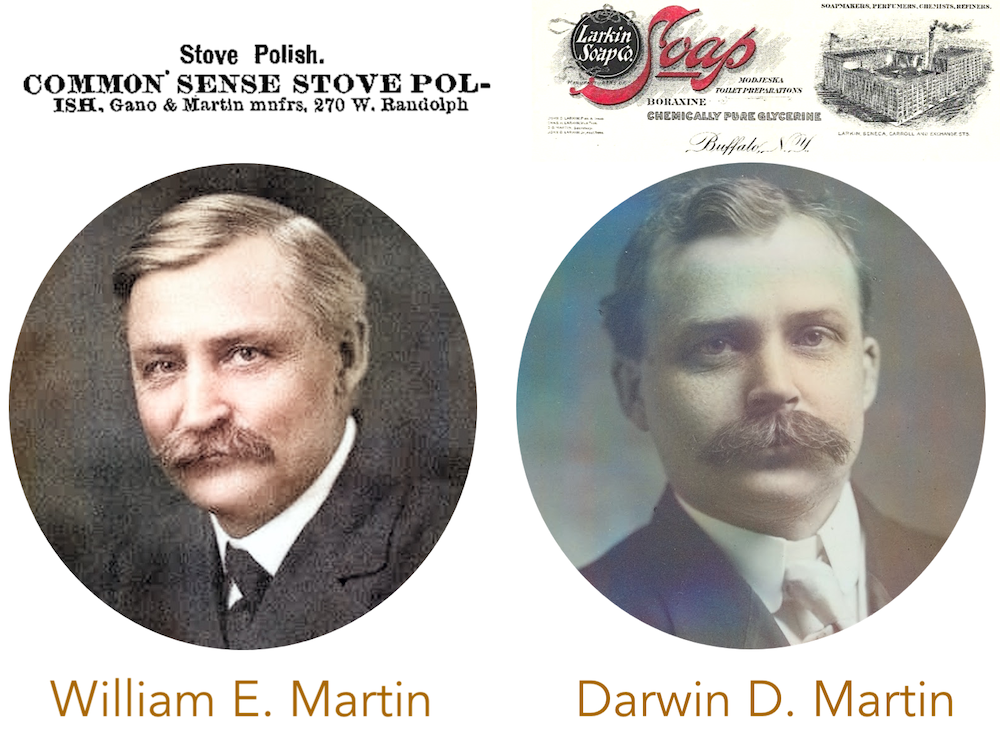

The transplanted Martin boys didn’t get along with their stepmother, nor did they enjoy the quiet life of the Great Plains. And so, by 1878, Darwin Martin—still only 13 years old— convinced his dad to let him take the train back to New York, where his eldest brother Frank got him a sales job with the Larkin Soap Company out of Buffalo. Soon, Darwin was a flatcap-wearing soap hustler on the streets of Brooklyn, proving himself a prodigy of the craft. The timing was great, too, because Larkin was rapidly evolving from a regional soap manufacturer into a major mail order catalog business, allowing Darwin to literally grow up with the firm and cash in on its success.

The transplanted Martin boys didn’t get along with their stepmother, nor did they enjoy the quiet life of the Great Plains. And so, by 1878, Darwin Martin—still only 13 years old— convinced his dad to let him take the train back to New York, where his eldest brother Frank got him a sales job with the Larkin Soap Company out of Buffalo. Soon, Darwin was a flatcap-wearing soap hustler on the streets of Brooklyn, proving himself a prodigy of the craft. The timing was great, too, because Larkin was rapidly evolving from a regional soap manufacturer into a major mail order catalog business, allowing Darwin to literally grow up with the firm and cash in on its success.

Meanwhile, back in Iowa, William Martin was carving out a path of his own. While he’d also worked briefly as a salesman for the Larkin Company—representing their Western interests—he never joined his brothers back East.

Instead, William made his way to Chicago, where—by the age of 21—he had organized a chemical polish business with a partner, Frank H. Gano, who was eight years older and experienced in the industry. That company, Gano & Martin, was succeeded in 1888 by the Common Sense Stove Polish Company, which was located at 270 W. Randolph Street, and advertised itself as “manufacturers of stove polish and shoe blacking.”

It’s not clear what led William Martin into the shine & polish biz, but he had a reputation (and an appreciation) for ingenuity across a broad spectrum of fields. According to some sources, he had personally developed the lithograph machine that was used to make the vibrant three-color labels on his products. He was also a dabbler in new transportation technology, designing his own bicycle coaster brakes and a traffic light control system. As an idea man, it’s easy to see how he’d later be impressed with the likes of Frank Lloyd Wright. In the meantime, though, William needed a series of financial backers to keep his upstart Chicago business afloat.

In the early 1890s, with Gano now out of the picture, William briefly partnered with his brother-in-law George F. Barton in this same stove polish enterprise, opening up a new headquarters at Carroll Avenue and Sacramento Avenue. The small factory required all hands on deck, including the two executives themselves. This led to a rather unfortunate incident in 1894, as William lost three fingers in a cardboard cutting machine when Barton—working on the other side of the machine— hit the switch a bit prematurely. Perhaps as no coincidence, that business partnership ended shortly thereafter.

Finally, in 1895, kid brother Darwin Martin—now secretary of the Larkin Company in Buffalo—swooped in to buy out George Barton and become an equal shareholder in his brother William’s scuffling Chicago polish business. The resulting organization, Martin & Martin, was small potatoes compared to Darwin’s other pursuits, but it found its niche at the dawn of the 20th century, thanks to its newly trademarked “E-Z” line of liquid polishes.

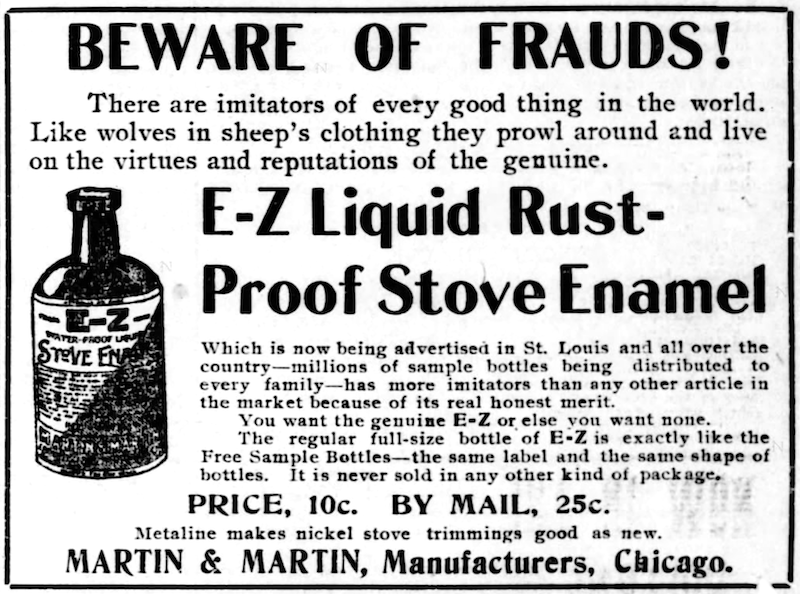

“Beware of Frauds!” shouted a 1900 newspaper ad for E-Z Liquid Rust-Proof Stove Enamel. “There are imitators of every good thing in the world. Like wolves in sheep’s clothing they prowl around and live on the virtues and reputations of the genuine. E-Z has more imitators than any other article in the market because of its real honest merit. You want the genuine E-Z or else you want none.”

“Beware of Frauds!” shouted a 1900 newspaper ad for E-Z Liquid Rust-Proof Stove Enamel. “There are imitators of every good thing in the world. Like wolves in sheep’s clothing they prowl around and live on the virtues and reputations of the genuine. E-Z has more imitators than any other article in the market because of its real honest merit. You want the genuine E-Z or else you want none.”

Nationwide promotions like this were devised with the help of Chicago’s Mahin Advertising Company, which William Martin personally praised in 1900, claiming that, “Now, after nearly 17 years in business, we feel that we only really began business last fall, when we became associated with Mahin.”

One of Mahin’s tactics was to publish personal testimonials supposedly sent in to Martin & Martin’s offices by satisfied customers, such as Miss Isa Berkheimer of Belle Plaine, Iowa, who wrote in 1902: “I have used five bottles of your E-Z Liquid Stove Polish and find it is the best of any stove polish I have ever used.”

The newspaper-centric marketing scheme proved fruitful, and allowed William Martin to ramp up production. The business grew from 12 workers to 21 between 1896 and 1901, and shortly thereafter, plans were underway for a new factory building on the existing location.

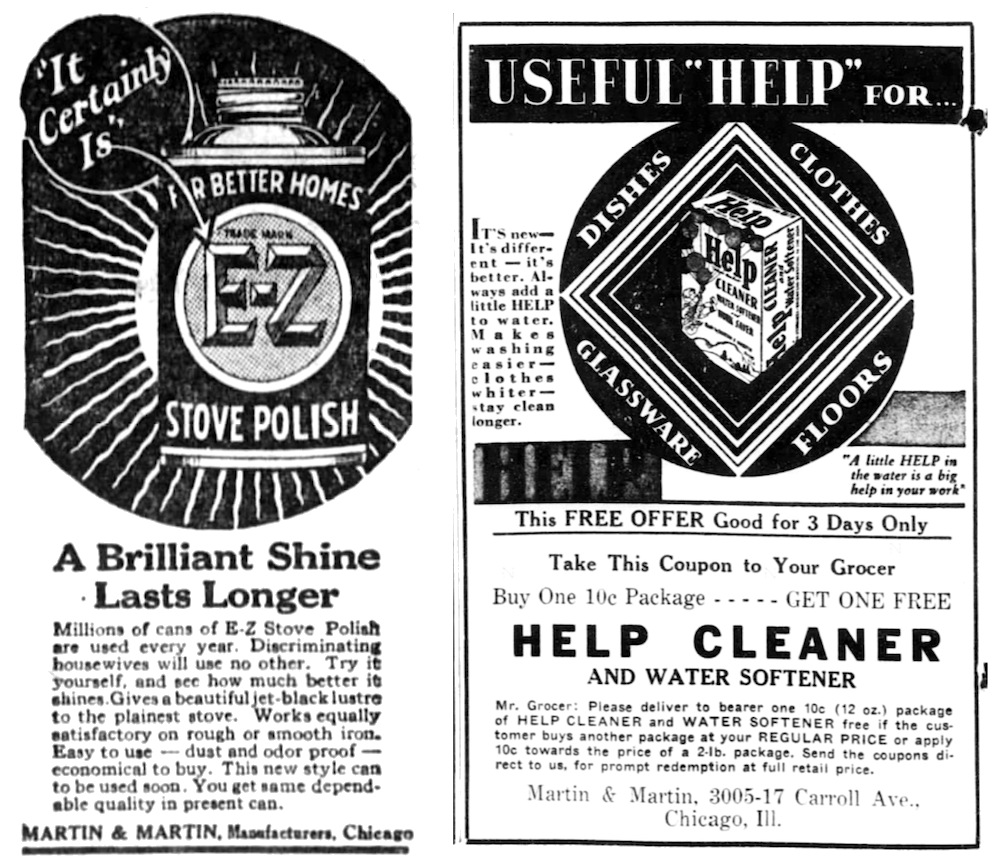

[Ads for Martin & Martin’s E-Z Stove Polish, from 1902 (left) and 1906]

II. When Wright Goes Wrong

“Dear Dar,” William Martin wrote his brother in a 1902 letter that’s often been republished in architectural history books. “I have been—seen—talked to, admired, one of nature’s noblemen—Mr. Frank Lloyd Wright. He is an athletic-looking young man of medium build, black hair (bushy, not long) about 32 years old. A splendid type of manhood. He is not a freak—not a ‘crank’—highly educated and polished, but no dude—a straightforward businesslike man—with high ideals.

“. . . You will fall in love with him—in 10 minutes conversation. . . . An office such as Wright can build will be talked about all over the country. It would be an ad that money spent in any other way cannot buy. I am not too enthusiastic in this— he is pure gold.”

“. . . You will fall in love with him—in 10 minutes conversation. . . . An office such as Wright can build will be talked about all over the country. It would be an ad that money spent in any other way cannot buy. I am not too enthusiastic in this— he is pure gold.”

William Martin had first arranged to meet with Frank Lloyd Wright to see if the young up-and-coming architect might design a new home for William and his wife Winifred in Oak Park, Illinois. The meeting went so well, though, that William eagerly started brainstorming other projects Wright might tackle. This would soon include his brother Darwin Martin’s house in Buffalo, a new Larkin office building in the same city, and finally a new E-Z Polish factory in Chicago.

While all of these projects came to pass, however, they weren’t without stumbling blocks, disputes, delays, and money shortages—all quite typical, by most accounts, of the Frank Wright experience.

By the time work had begun on the E-Z plant, in fact, William Martin’s original intoxication with Wright was already giving way to a growing agitation.

“Certainly, if Wright’s plans appear to be queer, his business methods are more so,” he wrote to Darwin in 1904. “Probably his loose methods are a mere indication of his great genius—because if a man is a genius, he must be a little off in other respects (?). I have fully concluded that while I thoroughly appreciate his plans and ideas, I would not give two cents for his superintendence of a job. As a matter of fact, the superintendence ought to be on his part of the work, to get him to do the right thing at the right time.”

Shortly after Darwin Martin read that assessment from his brother, he received a separate letter from Wright himself, which read:

“If the making of plans were as simple and as quickly to be performed as you think, I for one should be glad. . . . You fellows down there put a Chicagoan to shame in your get-there-gait, but he persuaded that the best results in buildings don’t come with that gait . . .”

[A few of the buildings Frank Lloyd Wright designed for the Martin Brothers over a three year span. Top Left: Darwin Martin House in Buffalo (1905); Bottom Left: Larkin Admin Building, Buffalo (1906, demolished in 1950); Right: William E. Martin House in Oak Park, IL (1903, current image courtesy of William Martin House). The E-Z Polish factory building was also under development during this same period.]

While Frank Wright had made an obsession out of every detail of Darwin Martin’s dream home in Buffalo, the concurrent E-Z factory project in Chicago was mostly left to Wright’s other associates to handle. This was a bit of a gut punch for William Martin, who had been Wright’s first real super fan, and had even lent him substantial sums of money when the architect was in over his head. From the beginning, the E-Z plant ran into major logistical issues, but its designer responded to queries slowly and with a cold disinterest, saying he’d be just as happy to exit the project entirely. William was now in full indignation mode.

“If you or the Larkin Co. owe Frank Lloyd Wright any money, please refuse to pay until you have heard further from me,” William wrote Darwin—a total reversal in tone from that original gushing letter from a few years prior. “He has served me a dirty, mean trick, for which he ought to pay, but it would be useless to sue him unless there is something due him in Buffalo, as he is not worth a dollar and probably never will be. At this writing, I can only say that he is not a man that I would ever have any dealings with.”

Poor Darwin Martin, who had fallen under the spell of Wright even more than his brother ever had, was stuck in the middle of this feud.

Poor Darwin Martin, who had fallen under the spell of Wright even more than his brother ever had, was stuck in the middle of this feud.

“Your brother gives me a character blacker than the ace of spades and far less symmetrical,” Wright wrote to Darwin in the midst of the drama.

A few days later, Darwin heard from William again: “Mr. Wright knows that our friendship has been dissolved until he sees fit to apologize for his insult and the trouble he unnecessarily caused me. . . . Better take warning and be very careful in your dealings with him. If he is sane, he is dangerous.”

Impressively, Darwin Martin finally stepped in between his pal Frank and his brother William, penning a letter jointly to the pair of them, with the goal of easing tensions and getting the E-Z Polish plant built.

“Dear Brothers,” the letter began, showing just how highly Darwin thought of Wright. “. . . If I were only wise enough to rise to the occasion, there are enough nice things said by each of you of the other to make all as merry as a marriage bell, but I know no better than to just say to you that if I had you both in the woods of Oak Park I would bump your heads together a few. But my wife says I cannot drive out our boy’s faults by licking him.

“. . . Mr. Wright knew, at least in advance of any connection with the factory building for W.E.M., of the latter’s weakness and intemperate temper and knows, too, and deplores as much as any of us (probably more—it hits him harder) his own lack of the faculty to consummate and so he hasn’t much right to explode when the medicine coming to him is administered by a man too intemperate to pour it in the sewer—where all medicine belongs.

“. . . Mr. Wright knew, at least in advance of any connection with the factory building for W.E.M., of the latter’s weakness and intemperate temper and knows, too, and deplores as much as any of us (probably more—it hits him harder) his own lack of the faculty to consummate and so he hasn’t much right to explode when the medicine coming to him is administered by a man too intemperate to pour it in the sewer—where all medicine belongs.

“You both know as well as I each other’s good qualities and your individual loss by allowing the other’s weakness to blot out and deny you access to the greatly predominating good, and I trust that ere this letter reaches you that good will have demonstrated its supremacy.”

Darwin, quite the diplomat and wordsmith, seemed to achieve his goal and stamp out the fire between his two hot-headed compatriots. The E-Z Polish factory, while greatly simplified from Wright’s original designs, was completed by 1906. The two-story building was somewhat unique for its era in its liberal use of reinforced concrete, but according to the Wright Library online, “the quality of the brickwork would not seem to pass Wright’s standards,” suggesting the project was largely under the management of his selected contractor Paul Mueller.

Over 50 workers were employed in the building when it opened, and in 1913, two additional stories were added, along with an entranceway sign featuring Wright’s original design of the Martin & Martin logo.

[There are no photographs of the E-Z Polish factory in its original two-story form, but these photos taken by Grant Manson in the 1940s show the impressive Martin & Martin signage on the expanded four-story structure, along with Frank Lloyd Wright’s personally designed company logo above the entranceway. The building had seen better days by this point and was up for sale. Courtesy of the Oak Park Public Library and the Wright Library]

In the aftermath of the factory’s construction, William Martin appears to have reconciled with Wright, although the rest of the American public soon developed similar doubts about the genius’s character and behavior.

According to Wright biographer Patrick F. Cannon, “For all these frustrations, the Martin brothers remained remarkably loyal to their architect. Both lent him money at various times and supported him in other ways. William—despite his sympathy with Wright’s long-suffering wife Catherine—even agreed to pick up Wright’s luggage upon his 1910 return from Europe, where his liaison with Mamah Cheney had scandalized Oak Park and become fodder for the Chicago papers.”

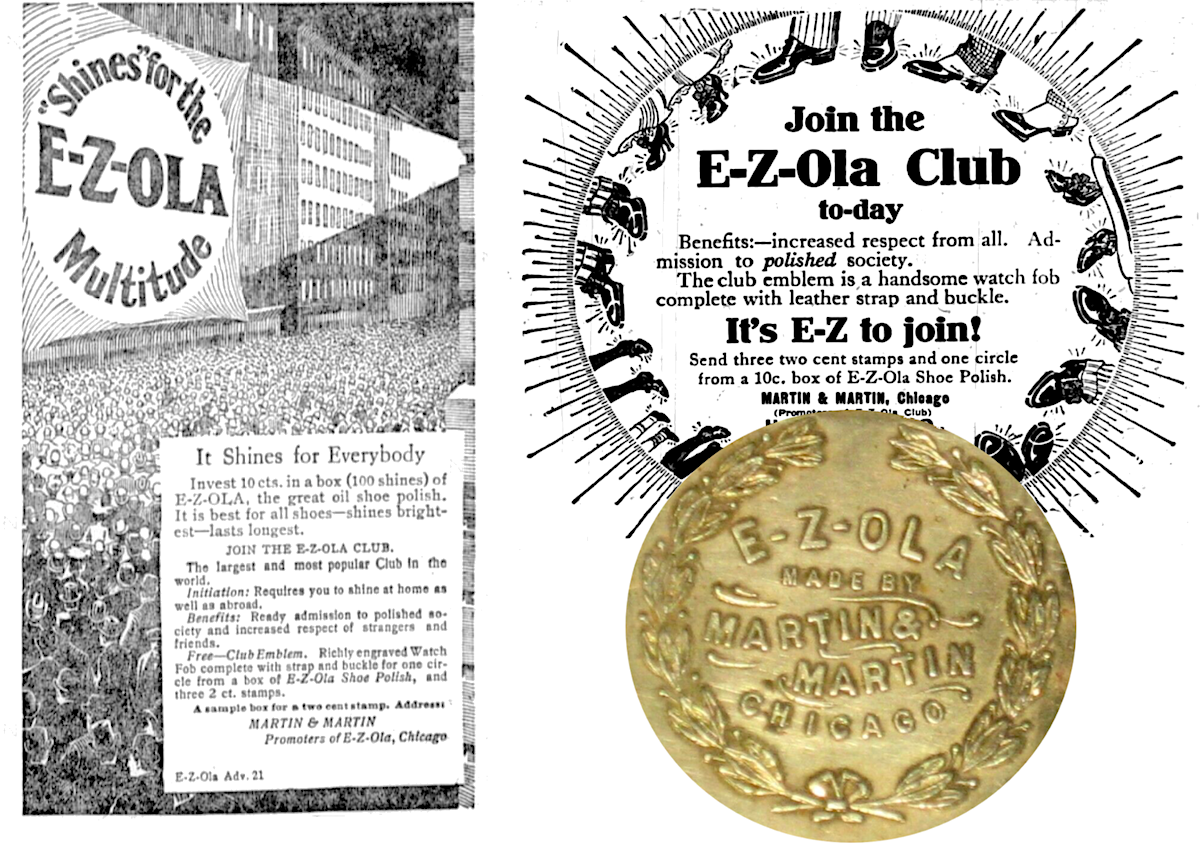

[Around the time their new factory opened in 1906, Martin & Martin were heavily promoting their new “E-Z-OLA” shoe polish, inviting customers to join the “E-Z-OLA Club” and handing out fancy promotional medallions to some of those who did]

III. Keep Free From Fire

The 1910s were probably the peak years for the E-Z Polish brands, based on the widespread advertising campaigns of the period and the expansion of the plant at 3005 W. Carroll Avenue. By 1916, the E-Z name was associated with stove polish, iron enamel (which could help prevent rusty automobile wheels), shoe polish, furniture polish, gold and aluminum enamel (for gilding and bronzing things), and asbestos cement—yup, good old asbestos—for mending a stove’s fire box.

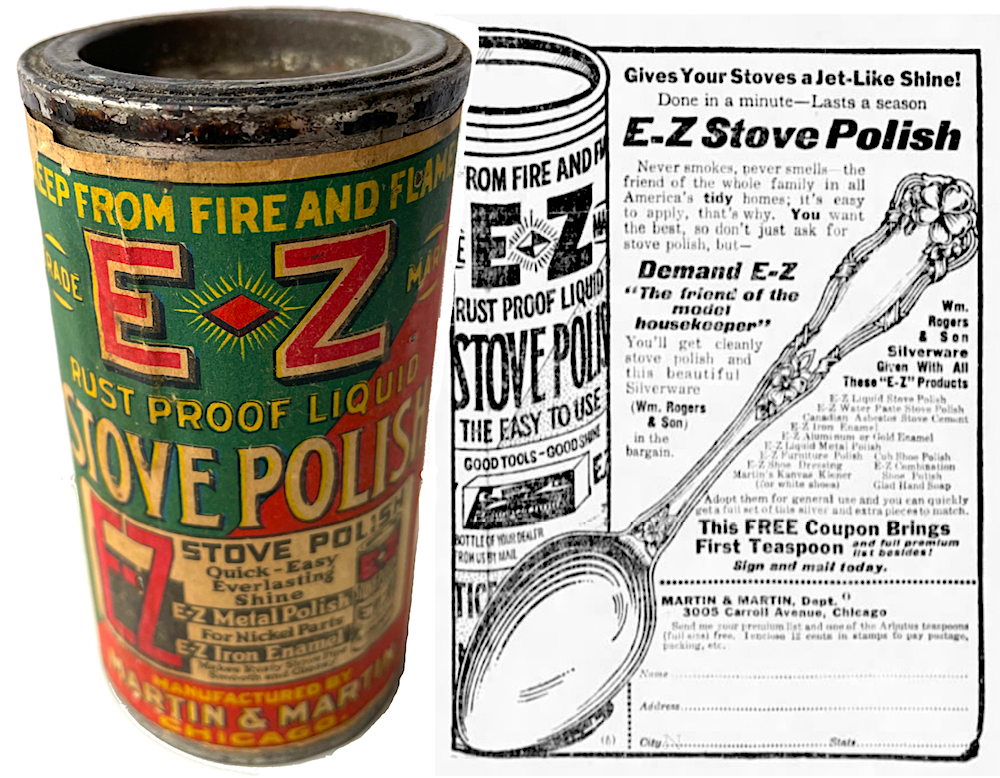

The specific bottle in our museum collection, E-Z Rust Proof Liquid Stove Polish, was touted in one 1912 ad as creating a “jet-like shine.”

“Never smokes, never smells—the friend of the whole family in all America’s tidy homes; it’s easy to apply, that’s why. You want the best, so don’t just ask for stove polish, but demand E-Z—‘the friend of the model housekeeper.”

“Never smokes, never smells—the friend of the whole family in all America’s tidy homes; it’s easy to apply, that’s why. You want the best, so don’t just ask for stove polish, but demand E-Z—‘the friend of the model housekeeper.”

E-Z might have been a friend, but it could quickly become a foe with drastic consequences if not used properly. You’ll notice a bold warning at the top of the label on the Stove Polish container in our collection: “KEEP FROM FIRE AND FLAME.” Well there was a good reason for that. E-Z Stove Polish contained gasoline, which has never historically paired well with open flames. As such, newspaper reports of the 1900s and 1910s find plenty of examples of people—usually young women—who thought they were safely cleaning their stoves but suffered terrible injuries or worse.

In 1908 alone, there was Mrs. Collison of Dexter, Kansas, who was “burned to death while blacking the stove with some E-Z stove polish while it was yet a little too warm”; 12 year-old Mary Dombrowsky of Saint Joseph, Michigan, who was “severely burned while applying some E-Z stove polish to a stove [she thought the fire was out but the stove was still warm, and as the polish was put on an explosion followed]”; and Mrs. Rozalia Pusklin of Chicago, also “fatally burned when the gas arising from the benzine in the liquid became ignited.”

After the latter incident, Retailer’s Journal reported that “the coroner’s jury brought in a verdict stating in terms that Mrs. Pusklin died from injuries sustained while using ‘E-Z’ stove polish, as a result of the ignition of the compound of which it is made.

[Despite the warnings on the label, some people who used E-Z Stove Polish didn’t realize the true danger of using the product before their stove was fully flame free]

“What a commentary upon the greed for money,” the Journal added, “that puts into the hands of the innocent, the careless, perhaps the ignorant, as a common household necessity, the means of taking life in the most horrible way and perhaps of starting a conflagration that might involve a whole city! The Chicago fire of 1871 was started from less cause.”

Needless to say, stories like this weren’t great for public relations, but it wasn’t a phenomenon unique to Martin & Martin either; most of their competitors in the chemical stove polish world were piling up unsuspecting victims, as well, so the sales impact was perhaps minimal . . . brutal as it may sound.

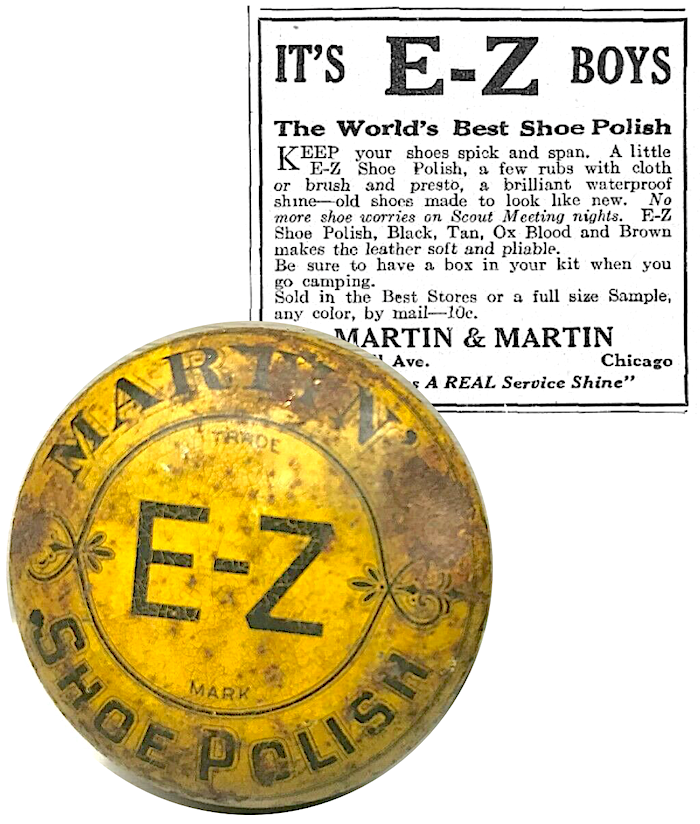

Still, there were clearly less dangerous and less combustible forms of polishes to produce, and Martin & Martin did start to emphasize these more through World War I and into the 1920s. E-Z Stove Polish was re-packaged to men as a good rust-preventative graphite paint solution for automobile wheels, and young boys became an unlikely target audience, too, as ads for E-Z Shoe Polish routinely ran in post-war issues of Boy’s Life magazine.

“It’s E-Z, Boys. Keep your shoes spick and span,” read one 1919 ad. “A little E-Z Shoe Polish, a few rubs with cloth or brush and presto, a brilliant waterproof shine—old shoes made to look like new. No more shoe worries on Scout Meeting nights.”

“It’s E-Z, Boys. Keep your shoes spick and span,” read one 1919 ad. “A little E-Z Shoe Polish, a few rubs with cloth or brush and presto, a brilliant waterproof shine—old shoes made to look like new. No more shoe worries on Scout Meeting nights.”

I would have thought a Boy Scout in 1919 might have been more concerned with the Spanish flu than whether his shoes were shiny, but sources of anxiety are hard to predict from one generation to the next.

In any case, by the late 1920s, we start to see a noticeable drop off in the national promotion of E-Z products and Martin & Martin (although a wholly different business of the same name, Martin & Martin Shoes, did do loads of regional advertising during this period). Information is scant on what was going on behind the scenes, but we do know that the E-Z factory soon had several other tenants, including the Metal Lithographing and Coating Corp., which operated out of the plant from 1919 to 1936. William Martin, now well into his 60s, had his son Everett K. Martin (b. 1900) in line to carry on the business, and by the 1930s, they also had a knew primary product in development: “Help Cleaner.”

“It’s new—it’s different—it’s better,” read a 1934 ad for the all-purpose cleaner and water softener. “Always add a little HELP to water. Makes washing easier—clothes whiter—stay clean longer.”

[Left: 1924 ad for E-Z Stove Polish, which slowly faded out of use by the 1930s. Right: 1934 ad for Help Cleaner and Water Softener, Martin & Martin’s new flagship product during the Depression.]

In the midst of the Depression, it was probably Martin & Martin, Inc., that actually needed Help. The stock market crash had devastated both brothers, particularly Darwin, who lost the entire fortune he’d earned at the Larkin Company. Darwin had supposedly loaned over $70,000 to his pal Frank Lloyd Wright in the years prior, and had also commissioned another of the architect’s famous works; a Lake Erie summer home called Graycliff. When fortune turned, though, Wright never repaid his debts, and when Darwin finally died of a stroke in 1935, there wasn’t enough money left in his estate to build the mausoleum Wright had designed for him. It wasn’t until nearly 70 years later, in 2004, that former Wright apprentice Anthony Puttman finally built Darwin’s mausoleum from the original plans (“Blue Sky Mausoleum” in Forest Lawn Cemetery, Buffalo).

William E. Martin and his wife Winifred were still living in their Wright-built Oak Park home through the ‘30s, but after dying within a few months of each other in 1938, the fate of Martin & Martin, Inc., was left fully in the hands of their son Everett.

Everett Martin gave it a go—the family business continued through World War II, seemingly focused mainly on Help Cleaner and similar chemical products. The company occupied only the second floor of the old factory at 3005 W. Carroll Avenue, and by 1948 had reorganized as the Great Lakes Chemical Company. That year, Everett Martin was also cited and fined for storing flammable liquids in the factory “without a license.” Even after 70 years, the business seemed less than concerned with optimal safety protocols.

Everett Martin gave it a go—the family business continued through World War II, seemingly focused mainly on Help Cleaner and similar chemical products. The company occupied only the second floor of the old factory at 3005 W. Carroll Avenue, and by 1948 had reorganized as the Great Lakes Chemical Company. That year, Everett Martin was also cited and fined for storing flammable liquids in the factory “without a license.” Even after 70 years, the business seemed less than concerned with optimal safety protocols.

It’s unclear when Martin & Martin / Great Lakes Chemical officially folded, but the former E-Z factory building was primarily the HQ of the Universal Foods Corp. by 1950. Everett Martin died in 1984.

Today, the former Martin & Martin building is still standing in Garfield Park. In recent years, it’s been used as a rehearsal space for local musicians, under the name of “Wright on Carroll.” While some hints of its architectural significance exist, the building is mostly a ghost of a bygone era. But 120 years ago, it’s where Frank Lloyd Wright nearly drove William Martin out of his head with rage, and thousands of bottles of potentially deadly stove polish were produced. There was nothing E-Z about it.

Sources:

“The Common Sense Stove Polish Company . . . ” – The Iron Age, Vol. 42, 1888

“William E. Martin” [obit] – Chicago Tribune, Sept 29, 1938

“William E. Martin House” by Jack Lesniak, 2000

“E-Z Polish Factory” – The Wright Library

Many Masks: A Life of Frank Lloyd Wright, by Brendan Gill, 1998

Hometown Architect: The Complete Buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright in Oak Park and River Forest, Illinois, by Patrick F. Cannon, 2006

Please note that contrary to popular belief, and despite William Martin’s repeated pleas, Darwin Martin was never a partner in the Martin & Martin company. The second Martin was in fact William and Darwin’s older brother Louis Frank Martin (1852-1927), known as Frank, with whom William formed a short-lived partnership in January 1894. Please see my history of the Martin & Martin Building in OA+D, the Journal of Organic Architecture and Design, v. 12, n. 2 (2024). https://store.oadarchives.org/product/journal-oa-d-v12-n2

Of possible interest?

Global web icon

University at Buffalo Libraries

https://digital.lib.buffalo.edu/items/show/5578

Darwin M. Foster (center) surrounded by group of children and …

WEB“Darwin M. Foster (center) surrounded by group of children and adults at picnic on Graycliff lawn,” Digital Collections – University at Buffalo Libraries, accessed August 4, 2024, …

I am William Martin’s granddaughter. It was thrilled to see this article and that you had a museum. I may have some things you would like. I have an ink Drawing of the original EZ Stove Polish Facrory from 1882, and a little bottle that was used for the stove polish. I would love to hear from you.

As a child, I often played at 636 East Ave. I am the daughter of Everett Kirby Martin. I had one older brother Everett, Gray Martin, who was a very successful journalist and was bureau chief for Time magazine in Vietnam during the war and finished his career as south American correspondent for the Wall Street Journal. My parents lived in an apartment in the house when Everett was born. He passed away several years ago. My younger sister, Janna, Martin Ossleifson Was a well-known educator in Our Boston area. She passed away a year ago.