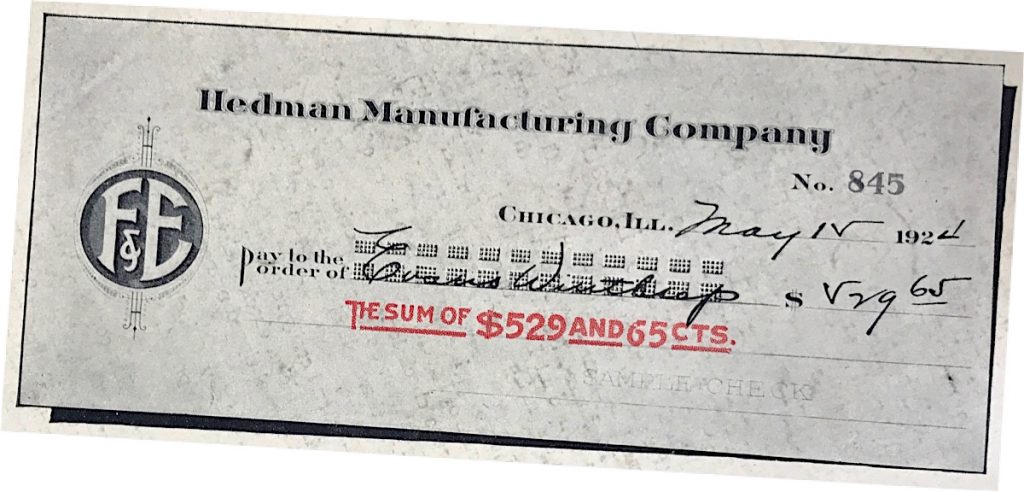

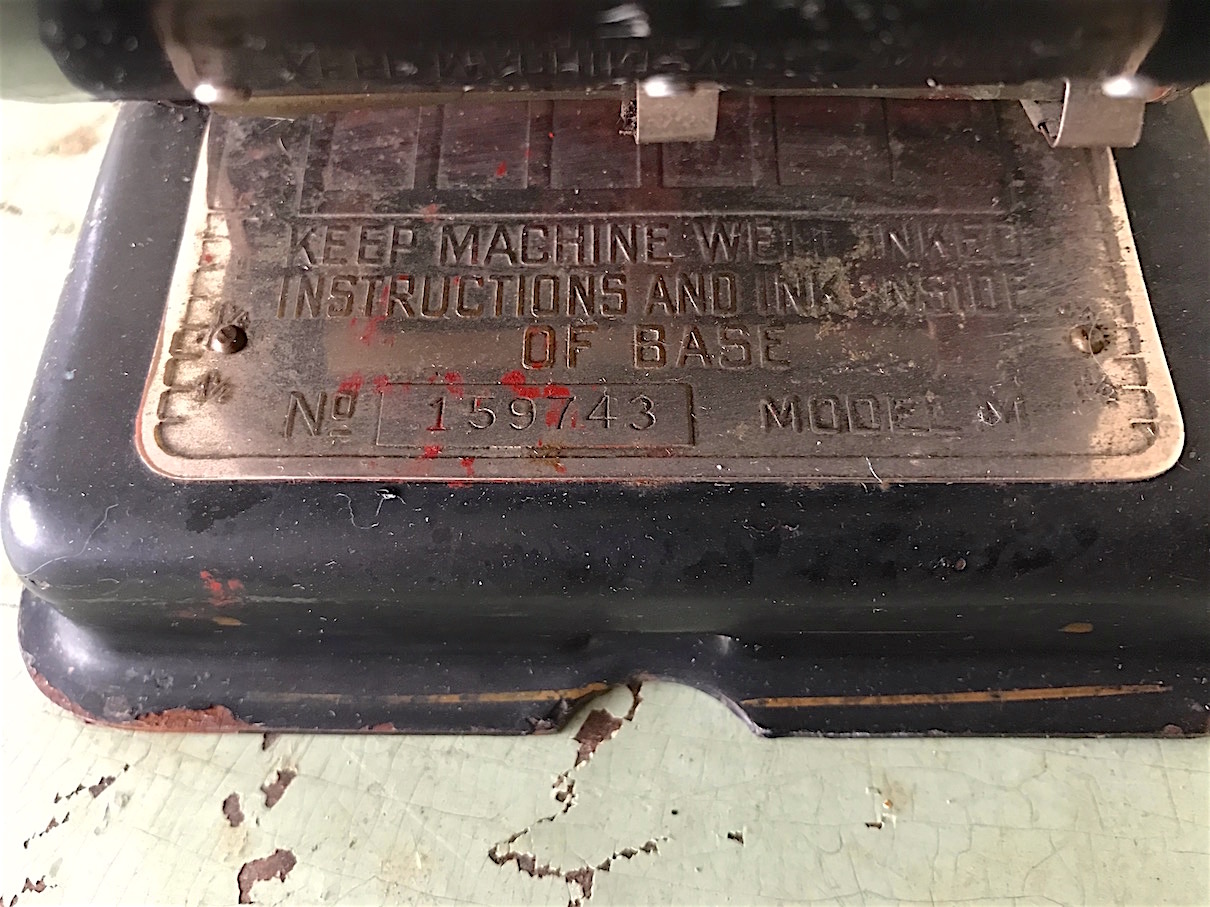

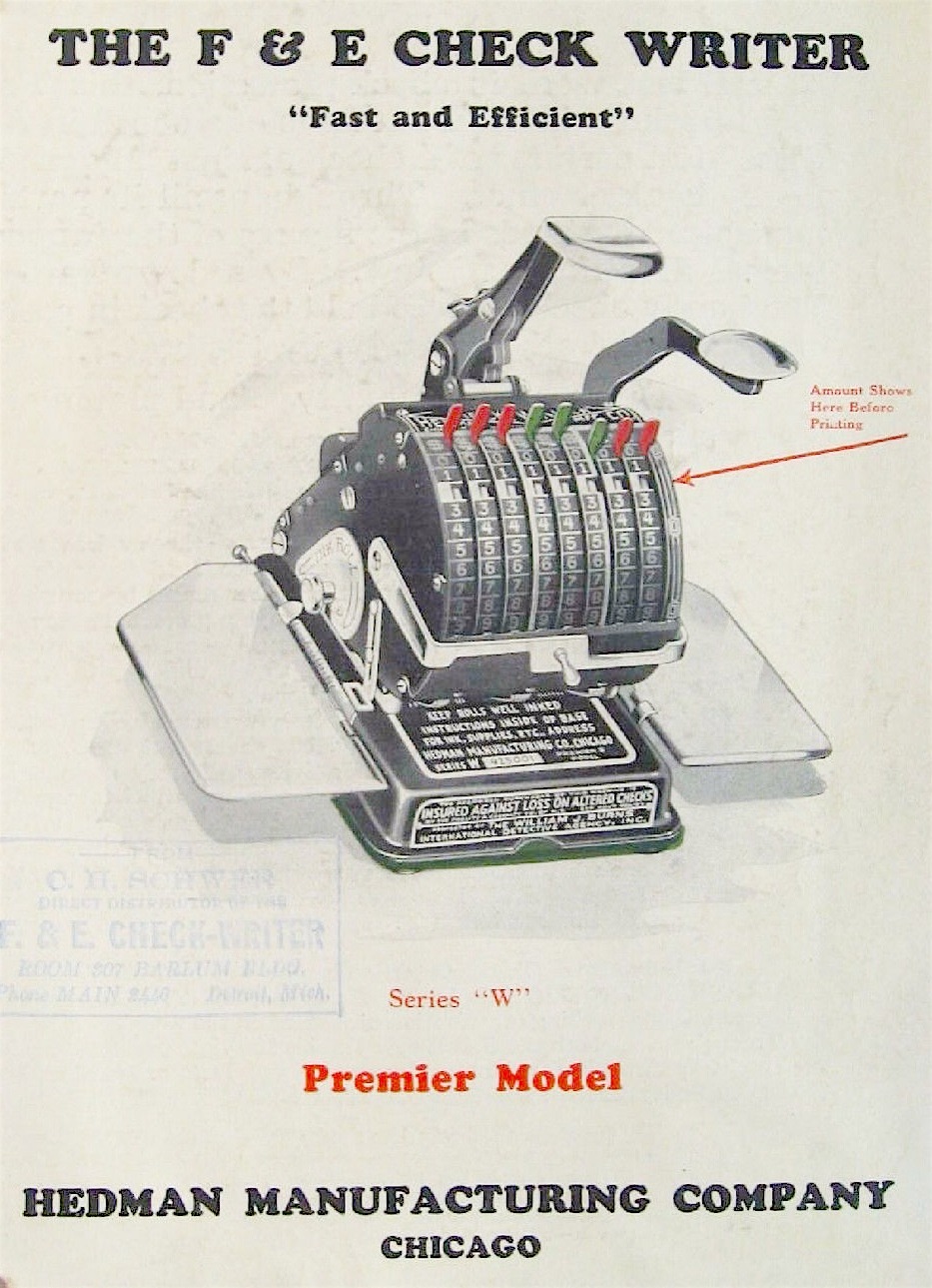

Museum Artifact: F&E Check Writer, 1920s

Made By: Hedman MFG Co., 1158 W. Armitage Ave., Chicago, IL [Lincoln Park]

First developed in 1914, the F&E Check Writer was more of a hi-tech defense weapon than a mere piece of office equipment. It was designed, as a number of other similar machines were in the early 20th century, to combat what was then considered “one of the gravest and most widespread of all menaces against our nation’s business”—check forgery.

Skilled forgers, known to swindled businessmen as “penmen,” “scratchers,” or simply “check raisers,” had mastered a wide array of methods for acquiring, editing, and cashing fraudulent checks. Since even many corporate paychecks were simply handwritten with a pen and ink during this era, all a criminally-minded fellow had to do was delicately inscribe an extra “y” to transform an eight-thousand dollar payout into EIGHTY-thousand. Incredibly, this kind of thing worked to remarkable effect, with multi-million dollar losses across the country stemming solely from the talents of weapon-less thieves.

Skilled forgers, known to swindled businessmen as “penmen,” “scratchers,” or simply “check raisers,” had mastered a wide array of methods for acquiring, editing, and cashing fraudulent checks. Since even many corporate paychecks were simply handwritten with a pen and ink during this era, all a criminally-minded fellow had to do was delicately inscribe an extra “y” to transform an eight-thousand dollar payout into EIGHTY-thousand. Incredibly, this kind of thing worked to remarkable effect, with multi-million dollar losses across the country stemming solely from the talents of weapon-less thieves.

“The growth of forgery and check alteration has been synonymous with the development of our great industrial system,” wrote Burgess Smith, a former inspector with the U.S. Bureau of Engraving, in a 1922 edition of American Industries magazine. “As checks have increased in use, forgers have increased in numbers, and as protective measures have improved in efficiency so has the forger’s’ skill. For many years the forger and his greatest foe, the designer of protective devices, fought a nip and tuck battle over many a bank account; and it was only recently that the latter won a decisive victory. This victory, it may be added, is one of science and chemistry over the cunning of the criminal.”

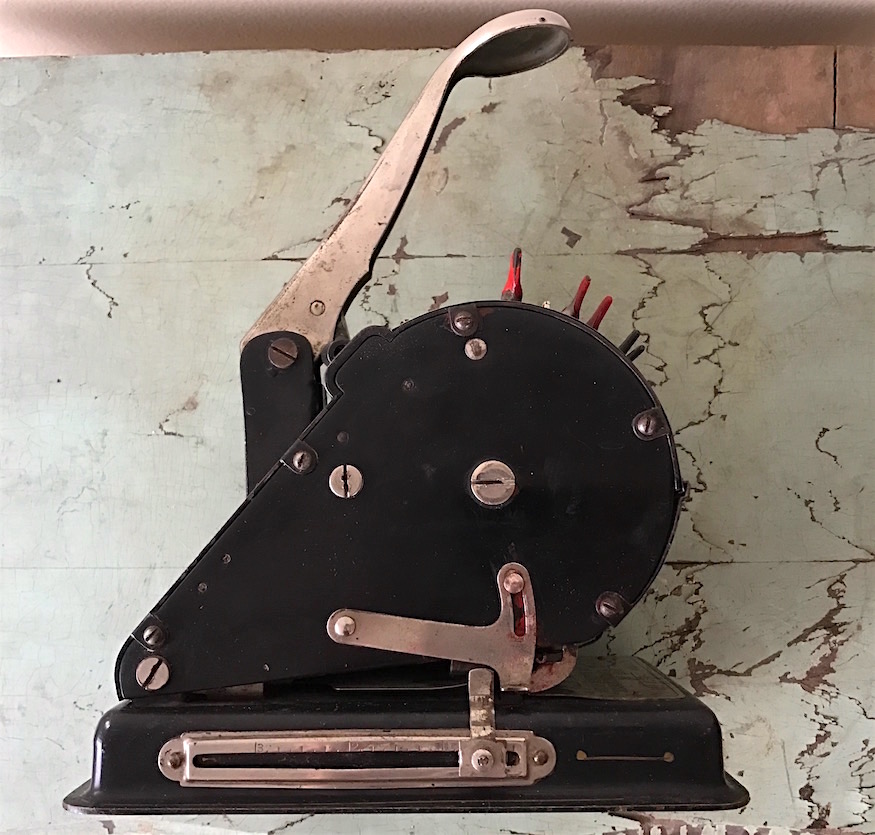

Smith is referring to the combined use of increasingly advanced “safety paper” along with fool-proof mechanical “check protector” machines like the F&E model in our collection. Unlike similar devices from earlier in the century, which used hole-punch style printing that remained vulnerable to alterations, the WWI era machines succeeded by “cutting the amount of words through and through the paper in shredded letters of two alternating colors, and at the same time, forcing an insoluble ink into these shreds under high pressure, making the fluid a part of the fibre of the document.”

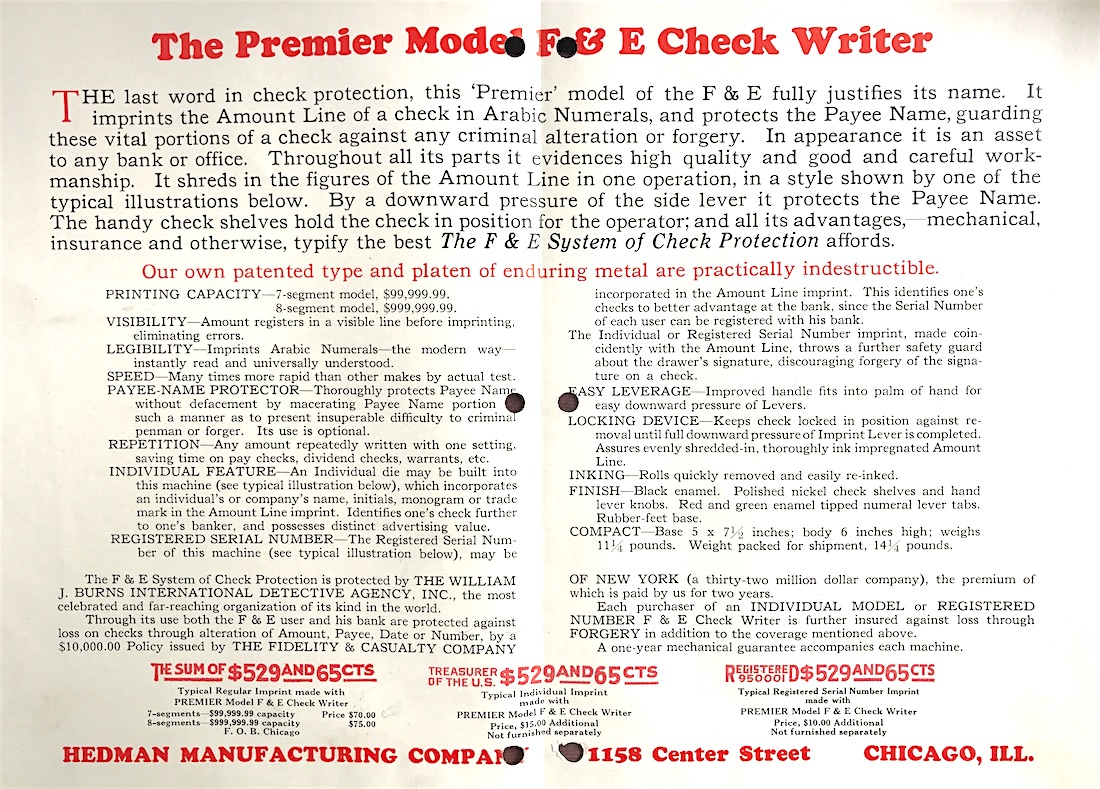

Or, as the F&E’s own advertising put it, this was “not a mere check writer, but an absolute, 100% prevention of loss through alteration of your checks.” Basically, kryptonite for those dastardly “scratchers.”

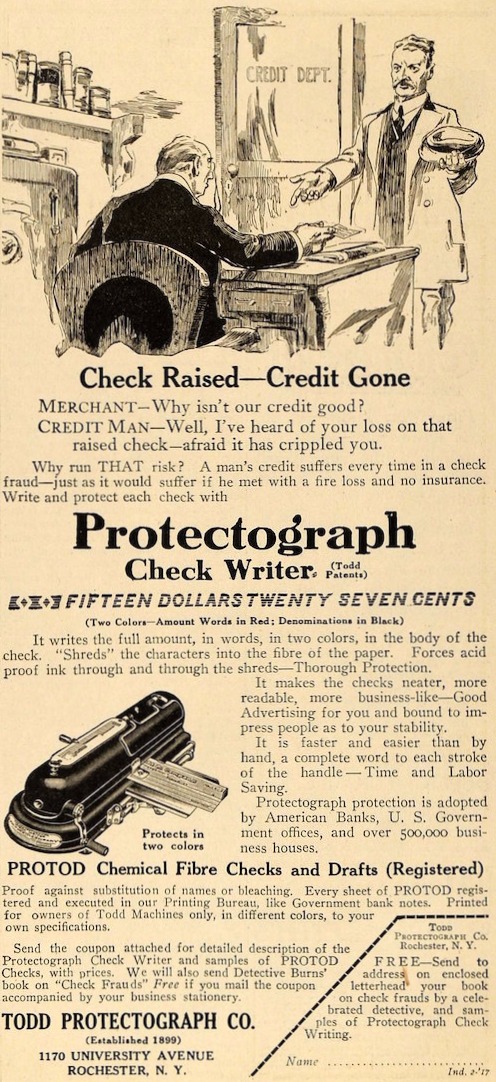

As noted, the F&E Check Writer was not the sole pioneer on this particular frontier. In fact, the machine’s similarity to a another device made by the Todd Protectograph Co. of Rochester, NY, led to several years of legal battles. In the end, though, the F&E’s advantages in cost and efficiency ensured its popularity and helped launch the fruitful business of its manufacturer, the Hedman Manufacturing Company.

Two Hedmans are Better Than One

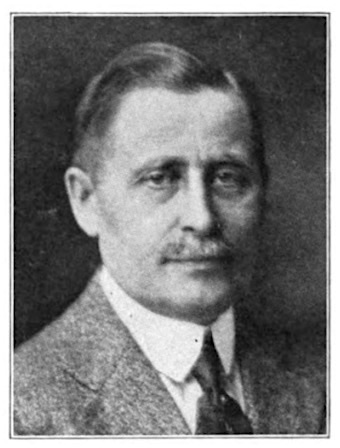

Besides helping to thwart would-be criminals with its ingenuity—Chicago’s Hedman MFG Co. was also a heartwarming father-and-son operation, organized in 1912 by a Swedish-born, 50 year-old mechanical engineer named Carl Maximus Hedman (president) and his 24 year-old son Herbert Ragnvald Hedman (secretary). The entirety of the firm’s purpose, initially, was the production of its own check protecting machine. From most accounts, the original idea for the device came from “the fertile mind” of the accomplished papa, Carl Max. The nut didn’t fall too far from the tree, however, as the ambitious young American-born Herbert—fresh out of the University of Illinois—was often given equal credit for bringing the early blueprints to fruition.

Even before the company was incorporated, the Hedman name was already well known in Chicago’s Swedish-American community, and not just among the factory crowd.

Carl Max Hedman (no relation to Max Headroom) was really a Renaissance man if there ever was one—a jack-of-all-trades and spitfire type of personality who earned friends easily with his “sunny disposition” and “excellent voice.” According to a 1915 article in the Swedish-language publication Svenska Tribunen-Nyheter, Carl could carry a tune with the same aplomb he put into designing complex machinery.

Carl Max Hedman (no relation to Max Headroom) was really a Renaissance man if there ever was one—a jack-of-all-trades and spitfire type of personality who earned friends easily with his “sunny disposition” and “excellent voice.” According to a 1915 article in the Swedish-language publication Svenska Tribunen-Nyheter, Carl could carry a tune with the same aplomb he put into designing complex machinery.

“[Hedman] was in demand everywhere,” the translated article says of Carl’s younger days.“He became a member of the Swedish Glee Club, the leading Swedish singing society at that time, and he was also much in demand for lovers’ roles in the then existing Swedish Theater Company. Many of us remember him as ‘Eric’ in ‘The Varmlanders’ and as ‘Passepartout’ in ‘Around the World in Eighty Days;’ his portrayal of many other characters also lingers in our memories. He was considered the best Swedish amateur actor in Chicago at that time. The theater company traveled about the country a good deal, and Hedman always went along on these jaunts. He thus acquired a large circle of friends and admirers outside of the city. Wherever he went everybody liked ‘Little Maxie,’ the pet name by which he is still known among his friends.”

Born in the province of Norrbotten, Sweden, in 1862, “Little Maxie” Hedman studied at technical schools in Stockholm and Copenhagen before coming to Chicago at the age of 23. His advanced training quickly earned him work with the Knapp Electrical Co., Western Electric Co., American Electric Co., and finally the Stromberg-Carlson Telephone Company, where he moved up the ranks to become superintendent of the Chicago plant by the age of 40. He’d mostly given up the song-and-dance by then, but in a time when Swedes were widely considered the world’s foremost experts on telecommunications, Carl Hedman had managed to become one of the leading Swedish telephone men in America.

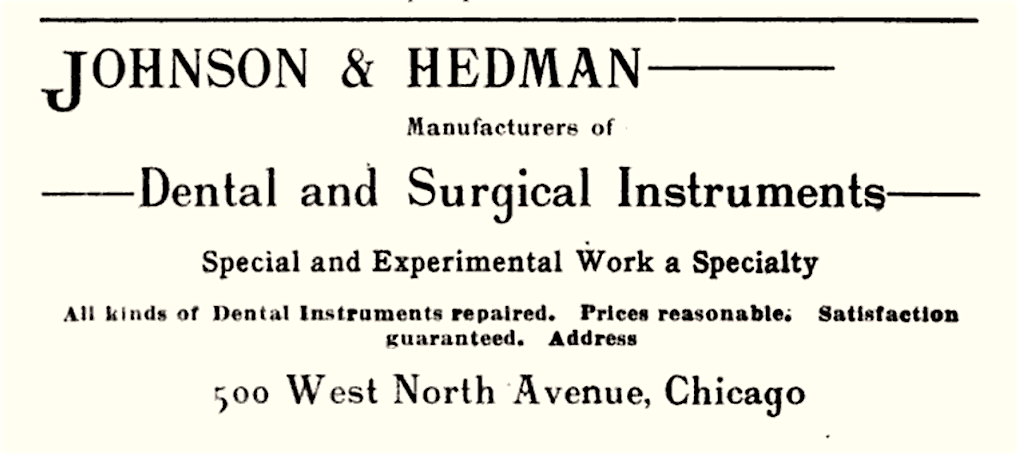

And yet, even in a position of prestige, Hedman wasn’t content to let his pursuits plateau. So, by the end of 1902, he’d left his post at Stromberg-Carlson to start a new firm of his own with a Norwegian business partner named Johnson. Forgoing telephones entirely, the Johnson & Hedman MFG Co. was focused instead on dentistry instruments. It was a less sexy field, perhaps, but the company did good business for a solid 10 years before Hedman sold its stock to make his jump into another completely different arena—check protectors.

In retrospect, it sounds like Carl Hedman was just running wildly from one creative whim to another. But it’s also quite plausible that he’d encountered his own frustrations with check fraud as a longtime business owner, and had gradually put his considerable mechanical skills into the challenge of solving the problem.

Hedman not only had some new ideas on methods for deterring forgers, but he also had some valuable industry connections that could help him design a cheap but durable device that would be marketable to a larger customer base than some of the existing options already on the market.

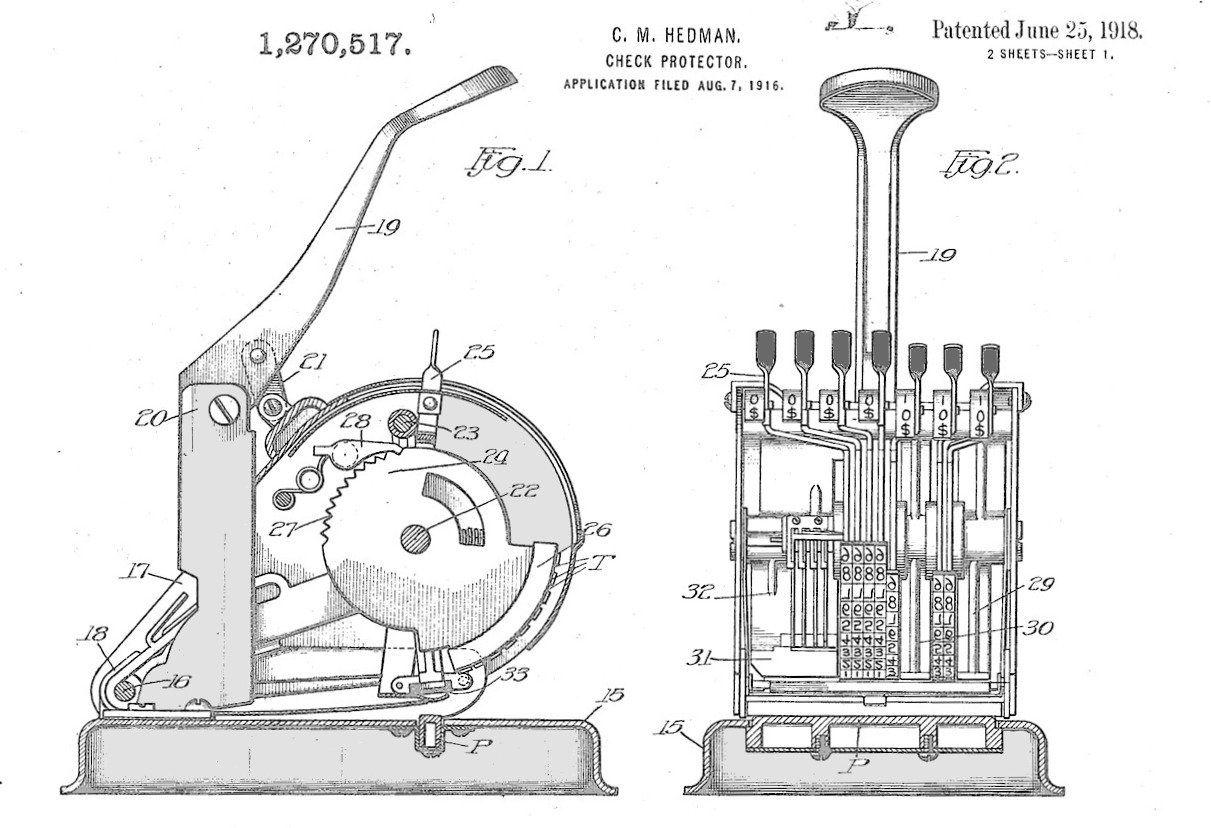

[Patent drawing of one of Carl Max Hedman’s early check protectors]

[Patent drawing of one of Carl Max Hedman’s early check protectors]

Early on, Carl turned to a fellow Chicago Swede and former Stromberg-Carlson co-worker John S. Gullborg, who’d recently made a small fortune developing a new type of automatic die-casting machine. With this in mind, Hedman decided to use “the finest cold rolled steel” to construct his check writers.

“The type is steel die cast of a hard composition metal,” an article in The Bankers Magazine later reported, “which will wear indefinitely even when subjected to the hardest usage.” This gave Hedman’s device a “decided advantage over over cast iron, which is prone to crack or break.”

“The type is steel die cast of a hard composition metal,” an article in The Bankers Magazine later reported, “which will wear indefinitely even when subjected to the hardest usage.” This gave Hedman’s device a “decided advantage over over cast iron, which is prone to crack or break.”

The efficient manufacturing process also allowed Hedman to price his machine at a “moderate cost” of just $20, “bringing it within the requirements of many banks and mercantile establishments that did not feel warranted in making the larger outlay for some of the high-priced but no more efficient check protectors.”

Perhaps returning a favor, Carl Hedman would go into business with John S. Gullborg in a more official capacity a few years later, serving as VP of Gullborg’s Alemite Metal Company while simultaneously still running the Hedman MFG Co. Carl would remain in leadership roles with both companies until his death in 1924.

Herbie Fully Loaded

While Carl Max Hedman had old pros like Gullborg to bounce ideas off of, he also seemed to have no hesitation in giving his son Herbert a central and active role in bringing their check writer from the design stage to the marketplace.

“Herbie Hedman (class of ’12) has cast his talents into the check protector business in Chicago,” the University of Illinois’s Alumni Quarterly reported in 1916. “Herbie’s protector seems to be the best check padlock ever made, and it sells for a mere picayune.”

“Herbie Hedman (class of ’12) has cast his talents into the check protector business in Chicago,” the University of Illinois’s Alumni Quarterly reported in 1916. “Herbie’s protector seems to be the best check padlock ever made, and it sells for a mere picayune.”

If “Herbie” Hedman was merely riding his father’s coattails, he certainly wasn’t going to correct his alumni newsletter for presuming otherwise.

Born in Chicago in 1888, Herbert R. Hedman was raised with the same dual appreciation for industry and art as his father. Later in life, he’d funnel a great deal of his personal fortune into funding local artists, including the Swedish-American sculptor Carl Hallsthammar. He also would help establish one of the earliest commercial television companies in America with the Western Television Corp.—which was based out of the Hedman Company building in the early 1930s.

It was the early days of the Hedman MFG Co., though, that gave Herbert his introduction to big business, and there were plenty of lessons to learn. One of the first biggies involved finding a worthy distribution chain for his dad’s check writer. It was a quest that quickly led the Hedmans into a collision course with another duo—two men so well acquainted with fighting check fraud that they seemed to be ironically willing to dabble in a little fraud themselves.

The F and E in F & E

Early in the set-up phase of their business, Herbert and his father were approached by two Midwest representatives of the Todd Protectograph Company of Rochester, New York—one of the best known check writer manufacturers in the field. These would-be competitors had caught wind of the new Chicago machine and eagerly offered to buy the product outright before it hit the market, presumably so the Todd Company could produce it going forward. When the Hedmans balked at the suggestion, the two visiting agents surprised them with an alternative idea.

Early in the set-up phase of their business, Herbert and his father were approached by two Midwest representatives of the Todd Protectograph Company of Rochester, New York—one of the best known check writer manufacturers in the field. These would-be competitors had caught wind of the new Chicago machine and eagerly offered to buy the product outright before it hit the market, presumably so the Todd Company could produce it going forward. When the Hedmans balked at the suggestion, the two visiting agents surprised them with an alternative idea.

“You can make the product yourselves here in Chicago,” the men said, “and we’ll independently distribute them for you, using our established networks, separate from the Todd business.”

“Isn’t that a conflict of interest, though?” young Herbert asked.

“Only if it’s a conflict of interest for Woolworth’s to sell different brands of candy bars,” they said—or probably something to that effect.

Basically, the two agents—Douglas F. Fesler and Winthrop O. Evans—were smart enough to know that the Hedman machine was the next big thing. And while they could have terminated their contract with the Todd Company and moved on, they elected instead to keep their old gig while secretly turning most of their attention to the new one. As if to celebrate their own audacity, Fesler and Evans also somehow got the Hedmans to call their new device the “F&E Check Writer,” named for two sales agents who were simultaneously on the payroll of a leading competitor.

Not surprisingly, this effed up situation eventually led to a lawsuit, as a furious G.W. Todd and his lawyers came after Hedman with accusations of patent infringement and unfair competition. Although the case of Todd Protectograph Co. vs. Hedman MFG Co. didn’t actually reach a district court until 1919, the trial saw Fesler and Evans brutally raked over the coals for their disloyalty.

“The testimony shows,” according to a synopsis in the Trademark Reporter, “that, while Fesler and Evans were important and trusted agents of plaintiff [Todd], they took up the Hedman machine (after first trying to sell it for a fair price to plaintiff), kept their connection with it a secret as long as possible, leased a building for manufacture and office purposes, and got as far along as possible to make and sell the device, meanwhile continuing in plaintiff’s service. While owing the utmost fealty to plaintiff, and making more than the usual number of sales of the Todd machine, they used what time they could to make all preparations for their own plans, and alienating some of the Todd agents. They apparently thought they owed plaintiff no duty beyond keeping up the normal amount of sales, and that while they were thus serving two masters they were free to conceal the situation. . .”

To make matters worse, Mr. F. and Mr. E. had also sold a large number of additional Todd machines (many of them in used condition) out of a fake Chicago storefront without the Todd Company’s knowledge—often falsely advertising the devices as brand new.

[D.F. Fesler and W.O. Evans ran ads like this selling Protectographs from the “Check Writer Emporium” on Franklin St., a company and office that never existed]

[D.F. Fesler and W.O. Evans ran ads like this selling Protectographs from the “Check Writer Emporium” on Franklin St., a company and office that never existed]

The pile of evidence led to a judge’s decision in Todd’s favor, but a long drawn-out appeal by the Hedman MFG Co. took the case to a U.S. Circuit Court Judge, who found that the Todd Company was “likewise guilty of its own unfair trade practices,” therefore reversing the decision.

In some ways, the point was already moot. The F&E Check Writer had long since taken a giant bite out of Todd’s market share (with more than 300,000 sold by 1921), and as technology continued to evolve, both companies were scurrying to move on from the older patents anyway. The big winners, really, were Fesler and Evans, who escaped their deceit scott free, and were actually rewarded with larger roles on the board of the Hedman Company (Fesler joined the upper ranks of the Alemite Metals Co., as well). The F&E brand name was left similarly unscathed, and would go on to survive in the industry in various forms into the 21st century.

In some ways, the point was already moot. The F&E Check Writer had long since taken a giant bite out of Todd’s market share (with more than 300,000 sold by 1921), and as technology continued to evolve, both companies were scurrying to move on from the older patents anyway. The big winners, really, were Fesler and Evans, who escaped their deceit scott free, and were actually rewarded with larger roles on the board of the Hedman Company (Fesler joined the upper ranks of the Alemite Metals Co., as well). The F&E brand name was left similarly unscathed, and would go on to survive in the industry in various forms into the 21st century.

So, did Carl and Herbert Hedman knowingly form an unholy alliance with the F&E boys as part of a conspiracy to build their stock by simultaneously damaging a competitor’s? Or was the papa-and-son business merely along for the ride, putting their faith in two experienced agents without ever realizing the questionable ethical ramifications? Well, since nobody involved is still around to tell the tale, we’ll likely never know.

“There’s Safety in Numbers”

Fair or not, with Fesler and Evans in their corner, the Hedman MFG Co. managed to sell its check writer, along with a “signature protector” and some other related devices, to a Who’s Who of hot shot clients: Standard Oil, Coca Cola, Quaker Oats, B.F. Goodrich, U.S. Steel, and many departments of the U.S. Government. In advertisements, the company credited its machine’s success on seven points of distinction:

Fair or not, with Fesler and Evans in their corner, the Hedman MFG Co. managed to sell its check writer, along with a “signature protector” and some other related devices, to a Who’s Who of hot shot clients: Standard Oil, Coca Cola, Quaker Oats, B.F. Goodrich, U.S. Steel, and many departments of the U.S. Government. In advertisements, the company credited its machine’s success on seven points of distinction:

1 – The F&E writes Arabic Numerals—the “universal language”—as used on A.B.A. Travelers checks. More quickly and accurately read than words.

2 – Writing in figures, the F&E writes ANY amount in one line, preventing dangerous double line checks.

3 – The F&E Individual Imprint gives advertising value to your check and prevents successful forgery.

4 – The F&E is two to four times as fast as other machines—proved by actual test.

5 – The F&E registers the amount before writing, eliminating errors.

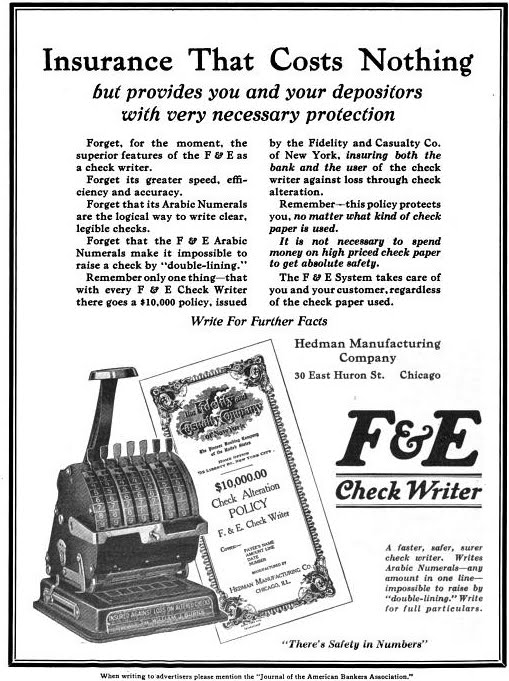

6 – Each F&E Check Writer is accompanied by a $10,000 policy issued by The Fidelity & Casualty Co. of New York (a $20,000,000 corporation), insuring you and your bank against loss through alteration of the amount, payee, date, or number, without requiring the use of special check paper.

7 – Users of the F&E are protected by an exclusive arrangement with The William J. Burns International Detective Agency, Inc.

Hedman’s rapid growth during those contentious years before and after World War I also forced several changes of scenery.

Originally organized at the corner of North Avenue and Milwaukee, the firm moved on to a facility at 123 N. Jefferson St., then a larger plant at 323 W. Erie St. with offices at 10-28 E. Huron Street. By 1924, ten years after the company’s incorporation and months before Carl’s death, ground was broken on an exclusive new three-story Hedman factory building at 1158 Center Street—known today as West Armitage Avenue. The company would remain in that same headquarters for the next 70 years.

[Former location of the Hedman Co. headquarters, 1158 W. Armitage Ave.]

[Former location of the Hedman Co. headquarters, 1158 W. Armitage Ave.]

“Credit is due Herbert Hedman for a considerable part of the success the firm has enjoyed,” read a 1931 profile in The Swedish Element in America. “Since 1924, when his father died, he has been the president of the company. He has bought the shares of his partners, and is now the sole owner of the business.”

While the Depression certainly challenged the Hedman Company as it did everyone else, the concerns of the times only increased the value of instruments that could protect a person’s money. Behind Herbert’s leadership, Hedman outlasted most of its earlier competitors, including Chicago-based manufacturers like the Checkometer Company, National Checkwriter Company, Wright Co., and Crescent Check Writer Co. The F&E Lightning Check Writer, an update to the model in our collection, was still in wide circulation and regarded among the best machines in the industry.

At the same time, Herbert Hedman—like his father—always kept an eye out for new horizons. This soon led to a partnership with Stenographic Machines, Inc., in 1939—a ten-year arrangement that made the Stenograph the gold standard in shorthand typing machines.

We have a 1940s era Hedman Stenograph in the museum collection, and you can get more info on the story of Stenograph Machines, Inc. by clicking the image below.

A Less Than Clear Conclusion

Into the ‘50s and ‘60s, as Chicago’s Paymaster Corp. emerged as the new leader in the check writer business, the Hedman Company diversified and carried forward, still producing new series of machines in partnership with the F&E Checkprotector Co., as well as what you might call cool “expansion packs” like the Royal Companion “Check-O-Meter”; an electronic check signer and dater that worked in tandem with the F&E machines.

The business survived the death of its longtime leader Herbert Hedman in 1970, and remained at its Armitage headquarters until the 1990s, when the offices finally moved to Elk Grove Village.

The official Hedman Company website was last updated in 2004, still touting the exploits of Carl and Herbert Hedman and their 90 year legacy. Unfortunately, no 100 year anniversary party would be in the cards. Through some order of events, the Hedman Co. disappeared by around 2011, likely either dissolved or bought out by a bigger entity. Its sister company, F&E, suffered a stranger fate, as the trademarked brand name seemed to pass out of copyright, allowing dozens of companies across the country to promote their services with the recognized F&E banner. If you can make any clearer sense out of Hedman and F&E 21st century status, I encourage you to do so below.

“The forger or check-raiser is no longer a danger signal for those who properly protect their checks. And proper protection is indeed simple. It involves using the best safety-paper available together with the modern check writing machines that shred the amounts in colors and then exercising care in handling your checks, that’s all. Where this method of protection been adopted, to date, there has not been a single case of loss from forgery or alteration.”

–Burgess Smith, 1922

SOURCES:

“Carl Max Hedman – Noble Swedish Businessman of Chicago” – Svenska Tribunen-Nyheter — September 21, 1915, Newberry Library

“Todd Protectograph Co. vs Hedman MFG Co.” – The Trade-Mark Reporter, Vol. 9, 1920

“The Check Raising Menace” by C.E. Wandel, Live Articles on Suretyship No. 2, 1918

“New Home of Alemite Metals Co.” – The National Corporation Reporter, Vol. 52, 1918

The Alumni Quarterly and Fortnightly Notes, Vol. 2 – University of Illinois-Champaign, 1916

The Swedish Element in Illinois: Survey of the Past Seven Decades, by Ernst W. Olson, 1917

The Swedish Element in America ed. by Erik G. Westman, 1931

The Bankers Magazine, July 1915

Bank Management, Vol. 66, 1990

“John S. Gullborg” – Manufacturing and Wholesale Industries of Chicago, Vol. 3, 1918

“$35,000,000 Yearly to Check Raisers” by Burgess Smith, American Industries, Vol. 22, 1922

I am trying to find information on a Lightning F and E check Writer, sold and distributed by Check Writer Company Inc. in New York. There is a serial number on the machine. Is there any place to research serial numbers for these machines?

We would like information on the check writer, Hedman company, electric, sign-0- meter and dater . It is also called a sign -O-meter. Thank-you It works great – the repair person said he never saw a check writer like this one before.

Does anybody know what years the MODEL R Hedman F & E Checkwriter was manufactured? Thanks!

Well,

I was trained by a Hedman factory technician and his trainee in the mid seventies.

We ran the F&E distributorship in the San Francisco bay area for years. The unfortunate part of the story was omitted…the demise of the Hedman Company was brought on by (in my opinion) evil people. Roland Lindburg and Arnold Wagers with their nasty lawyers went after all of the successful dealers and destroyed a once great company.

What kind of ink do these machines use ? I have an F&E XL. ( Hederman mfg co) also is the space between the amount and the payee ( perforation) line adjustable ?

Does anyone know where to find an owner’s manual for a Hedmond Model 500? I would like to learn how to service a check writer that has been in my family for many years.

I’m doing family research on Walter A. Seymour (1874-1945). His obituary says he was a salesman for the Hedman company. Would he have traveled around the country selling the check writing machines? How extensive was their marketing in the US? Could Walter have traveled to Jackson, Mississippi, as a salesman, for example? I’m trying to pin down his whereabouts before WW I. It’s apparent he worked for the company most of his life as a salesman. Wouldn’t he have been a traveling salesman, maybe traveling by train or automobile, staying in hotels?

Hi Arlan. Yes, Hedman had regional salesmen doing what you describe. And because they made well known office products, it would have been an extensive network of salesmen likely going to offices and knocking on doors. –Made in Chicago Museum

I have a Hedman company check writer machine to sell, any body interested ?

Located in France.

I Have a Hedman 2100 check printer that works well but low on ink and don’t know how to fix it. Can you service it?

Sorry but no. This is a museum about Chicago history, we’re not affiliated with the Hedman brands or any other manufacturer.

About 25 years ago I picked up a Checkwriter at a local garbage dump

It’s a W series 750980 can you date this and does it have any value or interest for museum?

Hi my name is Andy Tucker and i have a old lightning check writer that i have not been able to find a picture of one like mine anywhere. It’s a 500 series and the model number is 1045096 or the last number might be a 8 i can’t really tell. I was just wondering what the value of it was. Thank you for your time looking forward to hearing from you.