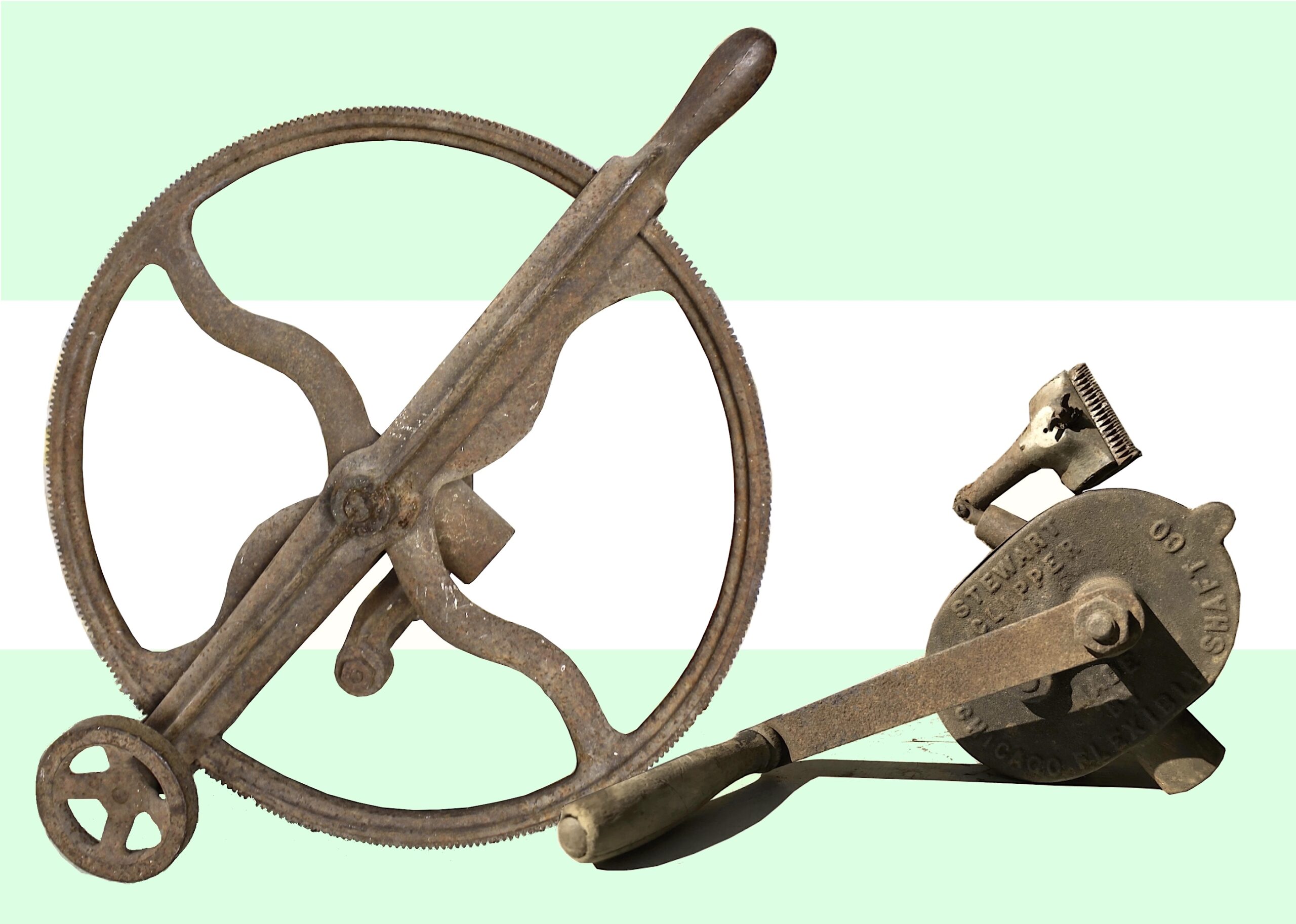

Museum Artifacts: Chicago Clipper (c. 1902), Stewart Clipper (c. 1910), Stewart Carriage Heater (c. 1908), and Rain King Sprinkler (c. 1920)

Made By: Chicago Flexible Shaft Co., LaSalle Ave. and Ontario St., Chicago, IL [River North]

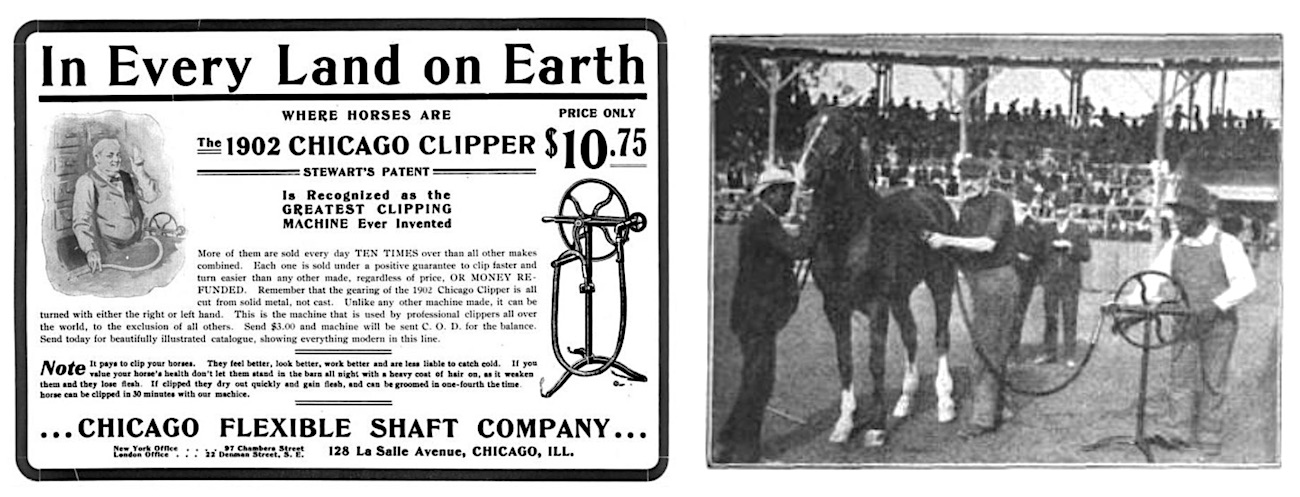

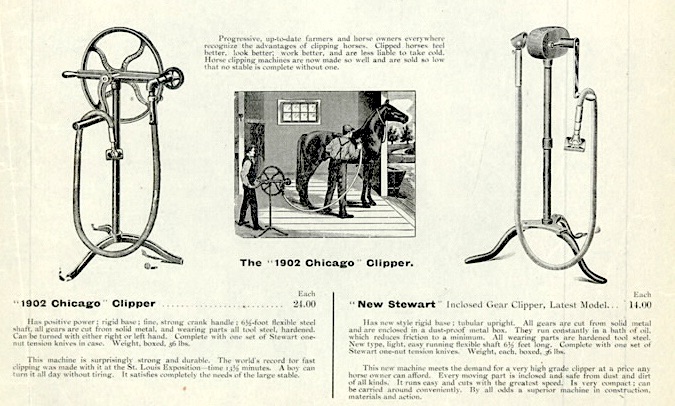

Don’t be fooled by the rusty and rustic-looking artifacts pictured above. When the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company introduced its line of hand-cranked horse clippers and sheep shearers at the end of the 19th century, they were literally and figuratively on the cutting edge of the industry; turbocharging barnyard makeovers in every town from Horseheads, New York to Hungry Horse, Montana. “The Chicago Clipper has made it possible to clip a horse completely in 14 minutes, the world’s record,” one newspaper reported in 1898, referring to the big gear-shaped device in our museum collection.

In due course, of course, smaller electric models sent these heavyweight machines out to pasture, but by that point, the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company had already lived up to its name and adapted—shedding its rural roots to make snazzy automobile accessories and kitchen appliances for America’s new urban modernia. If you’ve never heard of the business, it might be because it essentially “spun off” into two of the most successful appliance manufacturers of the 20th century, the Sunbeam Corporation (best known for toasters and mixers) and the Stewart-Warner Corporation (best known for speedometers)—each of which employed upwards of 4,000 workers in Chicago by the 1950s, earning them their own separate pages on this website.

In due course, of course, smaller electric models sent these heavyweight machines out to pasture, but by that point, the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company had already lived up to its name and adapted—shedding its rural roots to make snazzy automobile accessories and kitchen appliances for America’s new urban modernia. If you’ve never heard of the business, it might be because it essentially “spun off” into two of the most successful appliance manufacturers of the 20th century, the Sunbeam Corporation (best known for toasters and mixers) and the Stewart-Warner Corporation (best known for speedometers)—each of which employed upwards of 4,000 workers in Chicago by the 1950s, earning them their own separate pages on this website.

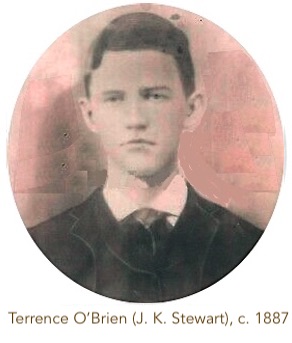

This leaves quite the legacy for the man credited as the “founder” of all three of these companies—a true man of mystery, I might add. Because while every history written about Chicago Flexible Shaft, Sunbeam, and Stewart-Warner will note the contributions of John K. Stewart, a closer look reveals that no such person actually existed . . . technically speaking.

Like a real-life version of the TV character Don Draper, John K. Stewart was actually an invented identity, created and curated by a man hoping to cut ties with his past. For over 20 years, Stewart went to great lengths to keep this secret, even as his success in business made him a well known multi-millionaire. His surviving parents and siblings back home heard nothing of his success, while his wife and children knew nothing, it seems, of his old life [Stewart even lied on passports and government documents about his name and place of birth]. It was only in 1921, five years after his death, that legal squabbles over his $7 million estate finally revealed Stewart’s humble origins, as well as the inspiration for his first enterprise. “Speedometer King was Really Terrence O’Brien, One-Time Clipper of Horses,” read the headlines in papers across the country. Which brings us right back around to the beginning . . .

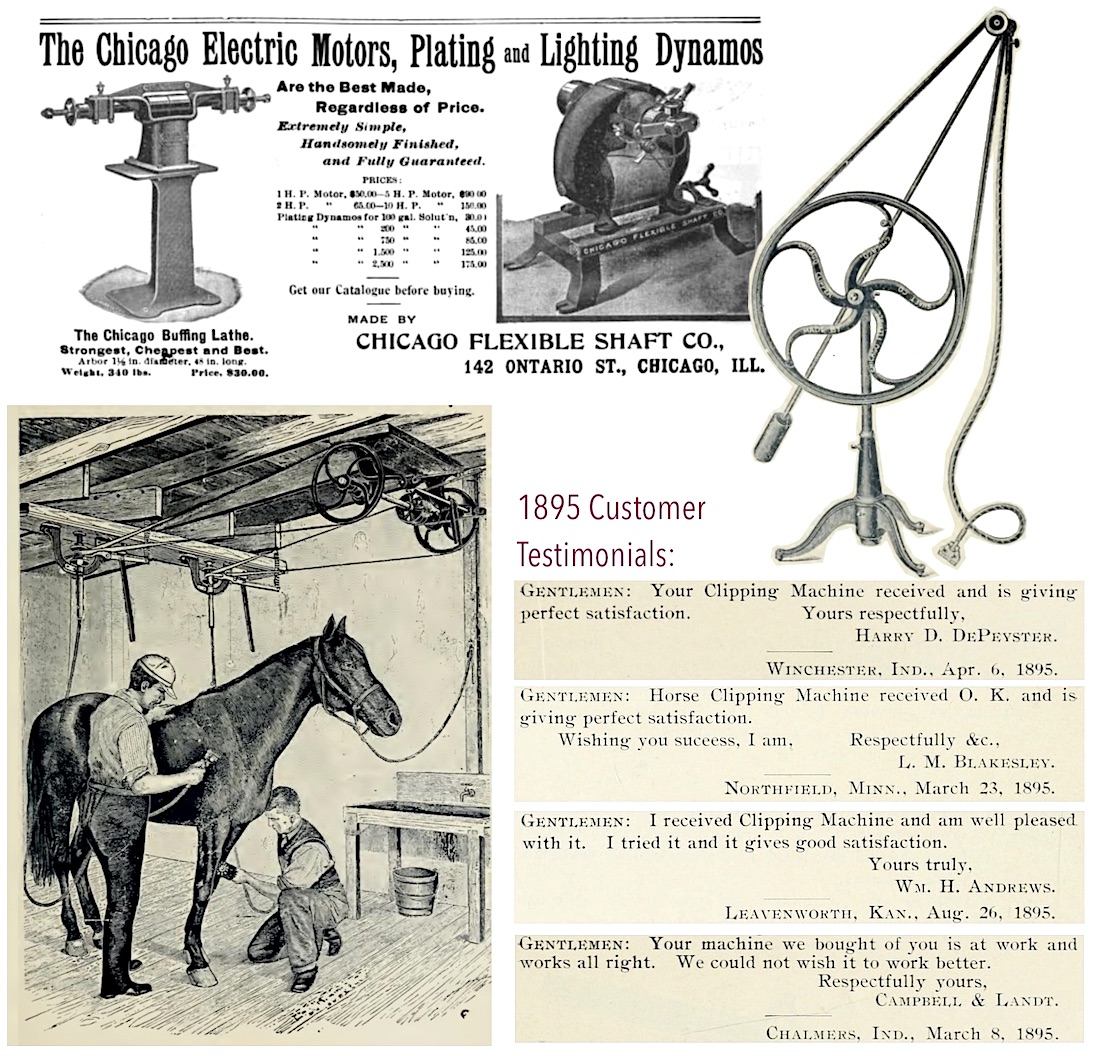

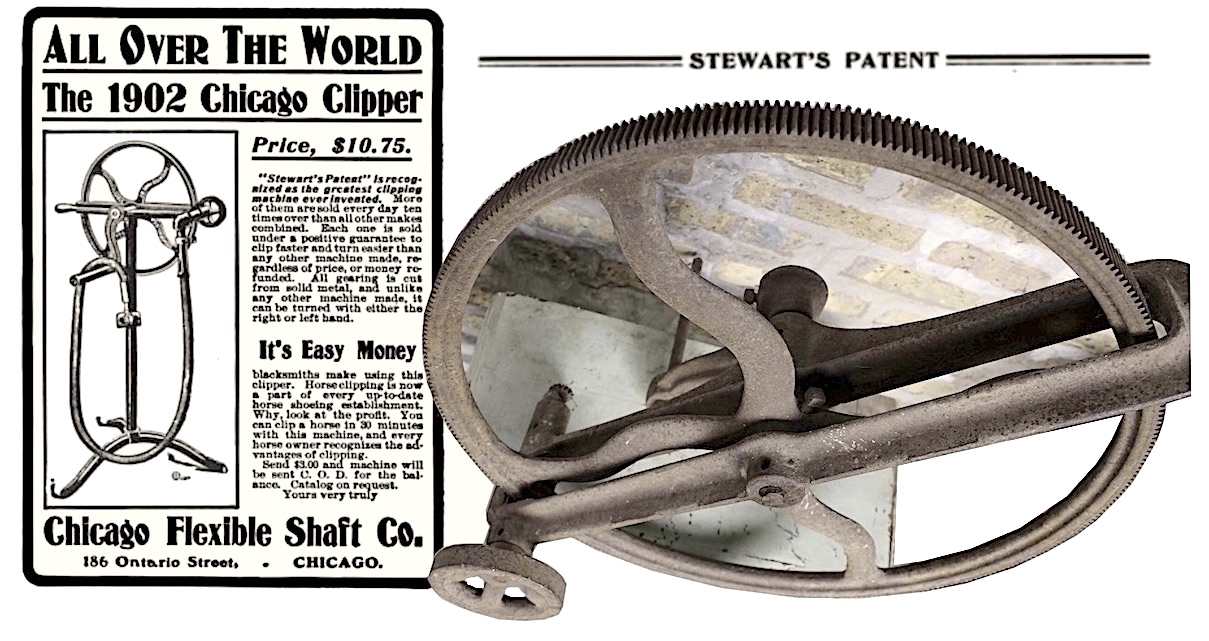

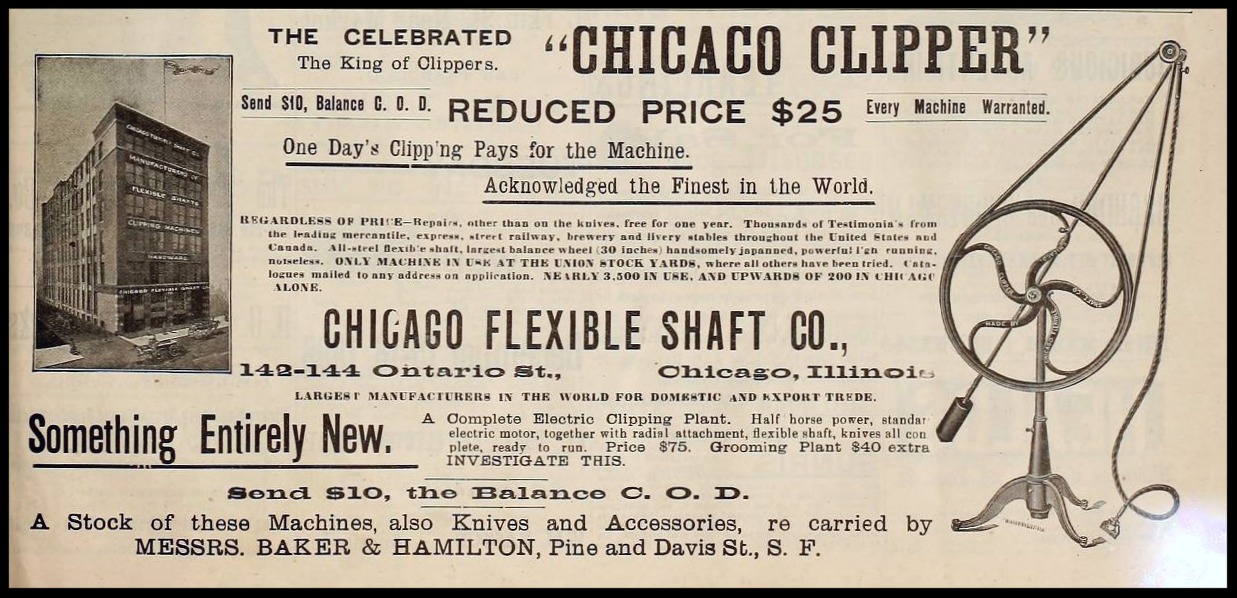

[Early advertisements, circa 1905, for the two Chicago Flexible Shaft clippers in our museum collection, the Chicago Clipper (top left) and the Stewart No. 1 Clipper (top right)]

History of the Chicago Flexible Shaft Co., Part I: “Stewart” & “Clark”

John K. Stewart was born Terrence O’Brien (spellings vary depending on the source) in Nashua, New Hampshire, 1869. He was the fourth child of Irish immigrants Terrence Sr. and Mary O’Brien, and grew up in a strict working class household. While his older brothers generally did as they were told, “Terrence was a trifle unruly,” according to a posthumous feature in the St. Louis Post Dispatch. “He had a bump of curiosity and independence, and this caused frequent clashes with his father.”

After high school, Terrence Jr. went to work at the local plant of the American Shearer Company, where his father was also employed. This job gave him an education on the mechanics of horse and sheep clippers, but also may have provided the impetus for his exodus from Nashua. According to legend, the rebellious teen abruptly quit his job one fateful day after the foreman ordered him to stop whistling as he worked. Unsurprisingly, his father was furious about this, and the ensuing family fight was heated enough that Terrence Jr. decided to “leave it all behind,” as they say. There would be some speculation years later that the falling out had a religious element to it, as well, as John K. Stewart was firmly agnostic and disenchanted with his family’s fundamentalism.

After high school, Terrence Jr. went to work at the local plant of the American Shearer Company, where his father was also employed. This job gave him an education on the mechanics of horse and sheep clippers, but also may have provided the impetus for his exodus from Nashua. According to legend, the rebellious teen abruptly quit his job one fateful day after the foreman ordered him to stop whistling as he worked. Unsurprisingly, his father was furious about this, and the ensuing family fight was heated enough that Terrence Jr. decided to “leave it all behind,” as they say. There would be some speculation years later that the falling out had a religious element to it, as well, as John K. Stewart was firmly agnostic and disenchanted with his family’s fundamentalism.

And so, joined by a childhood friend named Thomas Conlon, young Mr. O’Brien set off for Boston, where “his familiarity with shearing instruments caused them to get a job clipping horses. It was humdrum work for the young adventurers,” according to the Post-Dispatch, “but Terrence varied it by inventing a flexible shaft for his clipper, which was so successful that he obtained a patent on it.”

Patent or not, financial stability was not immediately forthcoming, and by the time O’Brien and Conlon arrived in Chicago in about 1890, they elected to truly start fresh—not just with a new business venture, but new identities. O’Brien became John K. Stewart (partially inspired, supposedly, by a racehorse called “John K”) and Conlon became Thomas J. Clark.

“Clark and Stewart arrived in Chicago with big ideas and precious few dollars,” according to a 1916 feature in the American Sheep Breeder magazine. “They rented a small vacant store room in a dead district on South State Street and started the manufacture of horse clippers, with machinery equipment that would draw a smile today.”

[Besides clippers, Chicago Flexible Shaft also made buffing lathes, electric motors, plating and lighting dynamos, as noted in the 1895 ad above. Some customer testimonials for the company’s early clippers, also from 1895, showcase the VERY tempered enthusiasm of the typical 19th century Midwestern farmer]

Caught up in the inventive spirit of the “Gays ’90s” and the Columbian Exposition, Stewart and Clark absorbed every new development in the animal clipping arts, refining their own designs in the process. “It took considerable evolving to perfect their first machine,” claimed the editor of American Sheep Breeder, who had known the duo back in those early days, “but they stuck to it like a dog to a root.”

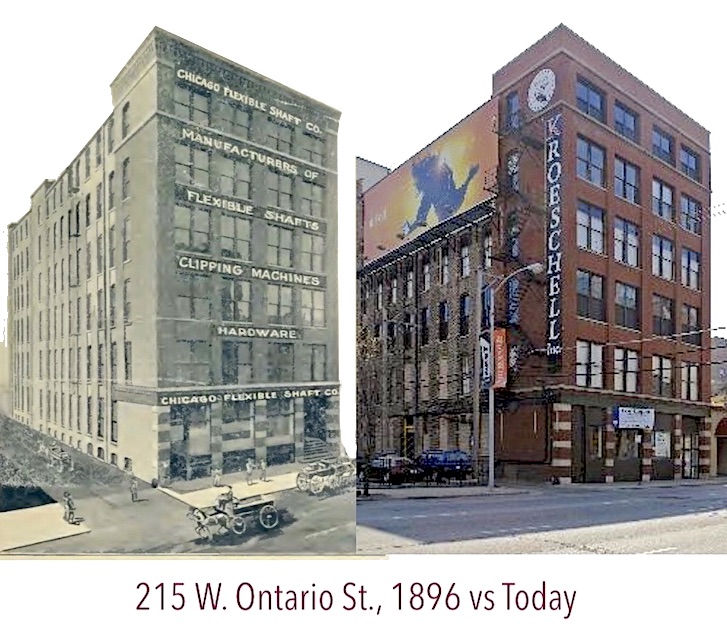

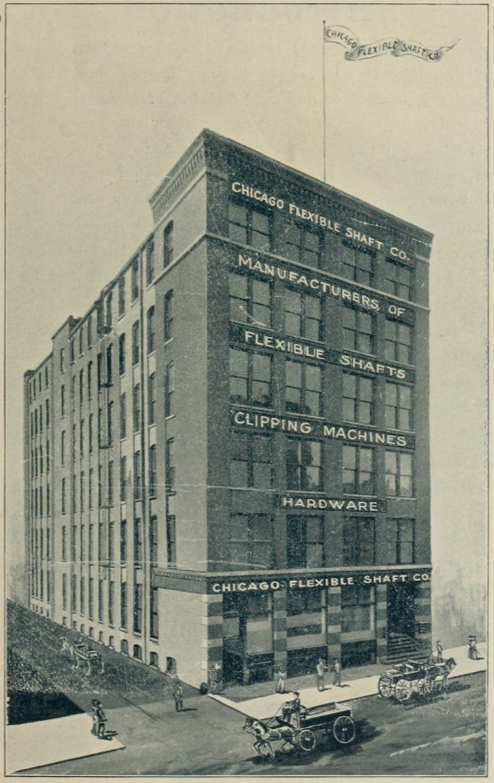

The fledgling Chicago Flexible Shaft Company had a room on Canal Street in 1894, employing 20 people, but orders were coming in fast enough that two additional facilities were acquired by the following year; one at 215 W. Huron Street (then known as 160 Huron) and another at 215 W. Ontario Street (then known as 142 Ontario). Both of those buildings are still standing today, with the former six-story Flexible Shaft headquarters on Ontario pictured below.

Still just 26 years old, John Stewart was the central brains of the CFS operation, serving as inventor and mechanic, while Clark was more of the “office man,” no easy task in its own right. For several years, the rapidly growing business walked a financial tightrope, going into debt to pay its rent, buy advertising, and keep their prices lower than the competition. By the time the company was officially incorporated in 1897, however, momentum had moved decidedly in one direction, spearheaded by the arrival of the company’s newest “Chicago Clipper.”

Still just 26 years old, John Stewart was the central brains of the CFS operation, serving as inventor and mechanic, while Clark was more of the “office man,” no easy task in its own right. For several years, the rapidly growing business walked a financial tightrope, going into debt to pay its rent, buy advertising, and keep their prices lower than the competition. By the time the company was officially incorporated in 1897, however, momentum had moved decidedly in one direction, spearheaded by the arrival of the company’s newest “Chicago Clipper.”

“The Chicago Flexible Shaft Co. have recently placed on the market the New ’98 Chicago Clipper, price $12.75, which has practically revolutionized the horse clipping business,” reported the Blacksmith and Wheelwright in December of 1897. “The machine is made on the same principle as the chainless bicycle, and is destined to supersede all old style two-hand horse clippers, and also the old-fashioned, high-priced belt machines.”

[While the Chicago Clipper was introduced in the mid 1890s, the model in our collection seems most akin to the “celebrated” 1902 edition, advertised above. Sadly, our artifact lacks the actual blade, not to mention the all-important flexible shaft itself]

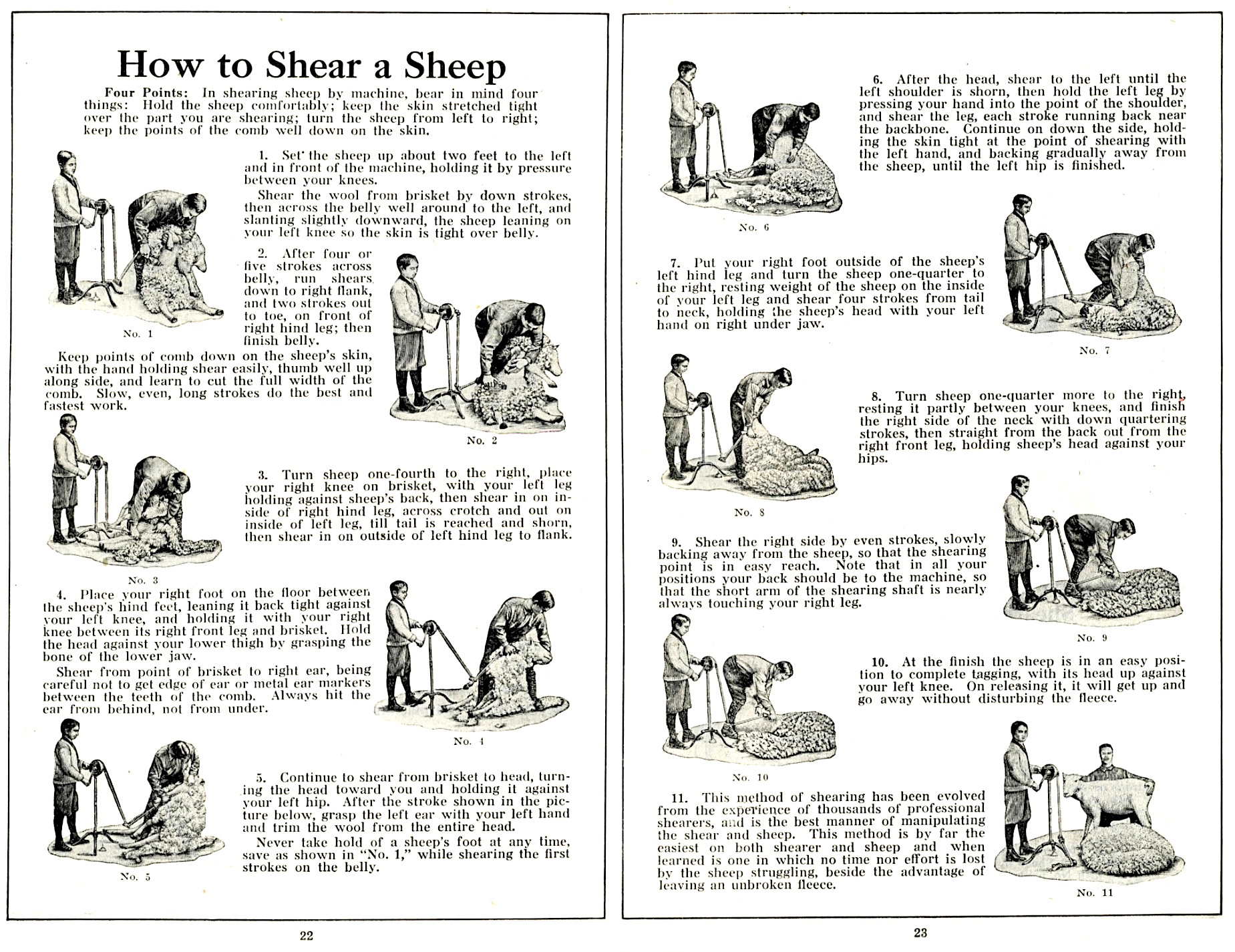

The Chicago Clipper, as evidenced by the example in our collection, was not exactly “portable” in the modern sense. The 18″ diameter crank gear alone—cut from solid metal rather than cast—weighs about 30 LBS, and that’s without the stand it likely originally sat atop. Still, it was a game changer, not only preventing the common problem of hair clogging, but also dramatically reducing the time and labor required to do the job. The operator simply needed to turn the crank, and the teeth on the edge of the gear would then “engage with a small hardened steel pinion,” according to a 1902 article in Iron Age magazine, “which in turn transmits the power to the flexible shaft and knives. …The clipper is alluded to as free turning, fast cutting, simple, and as permitting the clipping of a horse in less than 30 minutes. …It requires no experience to operate, and a small boy can turn the crank all day without tiring.”

John K. Stewart was surely pleased to no longer be the poor boy turning a crank all day for a meager wage. He and his buddy Tom Clark were well on their way to becoming very rich men, and the New England boys known as O’Brien and Conlon were all but forgotten.

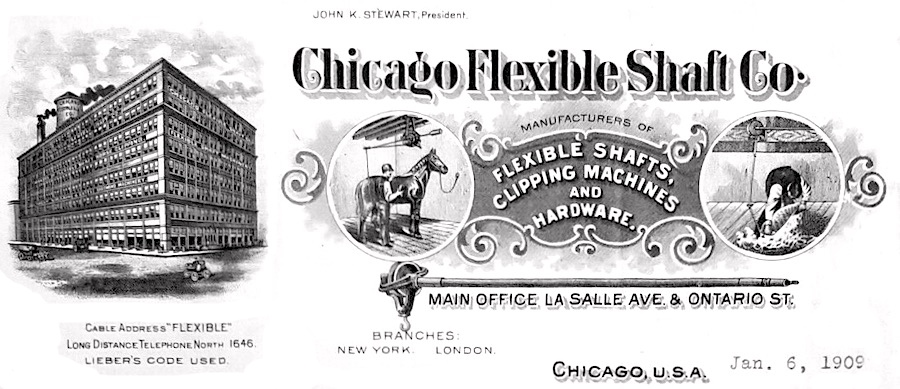

[Letterhead from 1909 shows the Chicago Flexible Shaft complex at the corner of LaSalle and Ontario, about a block from their previous building. This location appears to have been torn down and replaced with a newer building in the 1920s, which is still standing as 620 N. LaSalle]

Part II. A Horse of a Different Color

As the 20th century began, the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company had already become the self-described “largest makers of Flexible Shafts in the world,” and no competitors could really make a case against them. More than just a sheep and pony operation, the company’s patented eponymous products could be easily adapted for a myriad of other uses, creating new clientele in loads of industries: “ship yards, railroads, machine shops, foundries, glass works, and thousands of other manufacturers.” All that production required yet another expansion of factory space, as CFS migrated down the street to an even larger complex at the corner of Ontario and LaSalle (the original building is no longer there, but its replacement, built in the 1920s, is now known as 620 LaSalle).

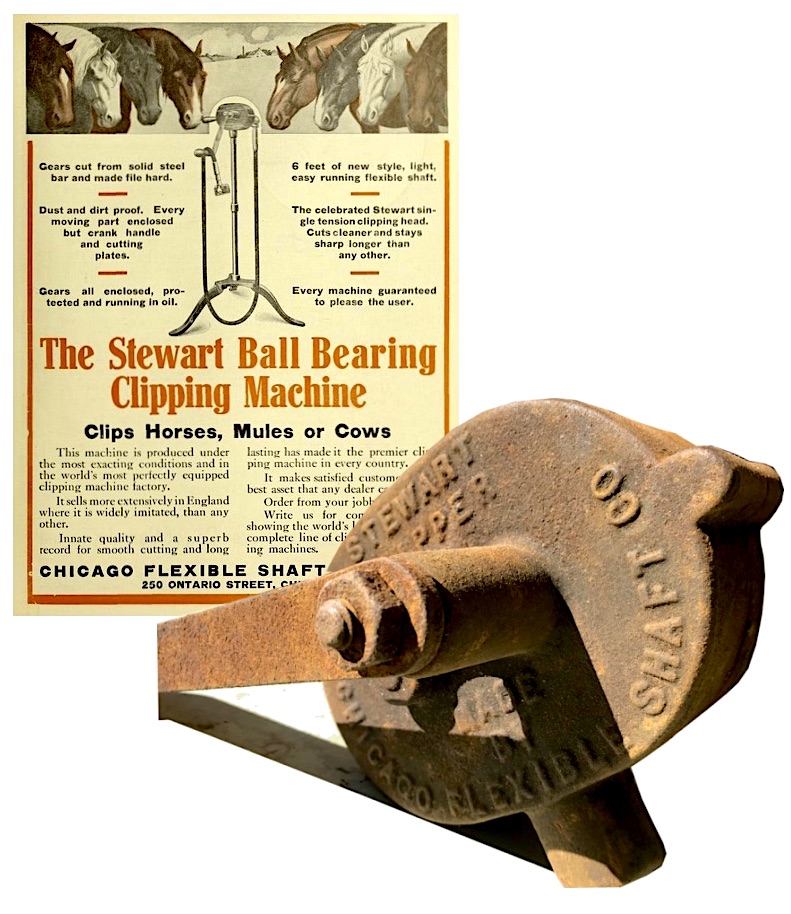

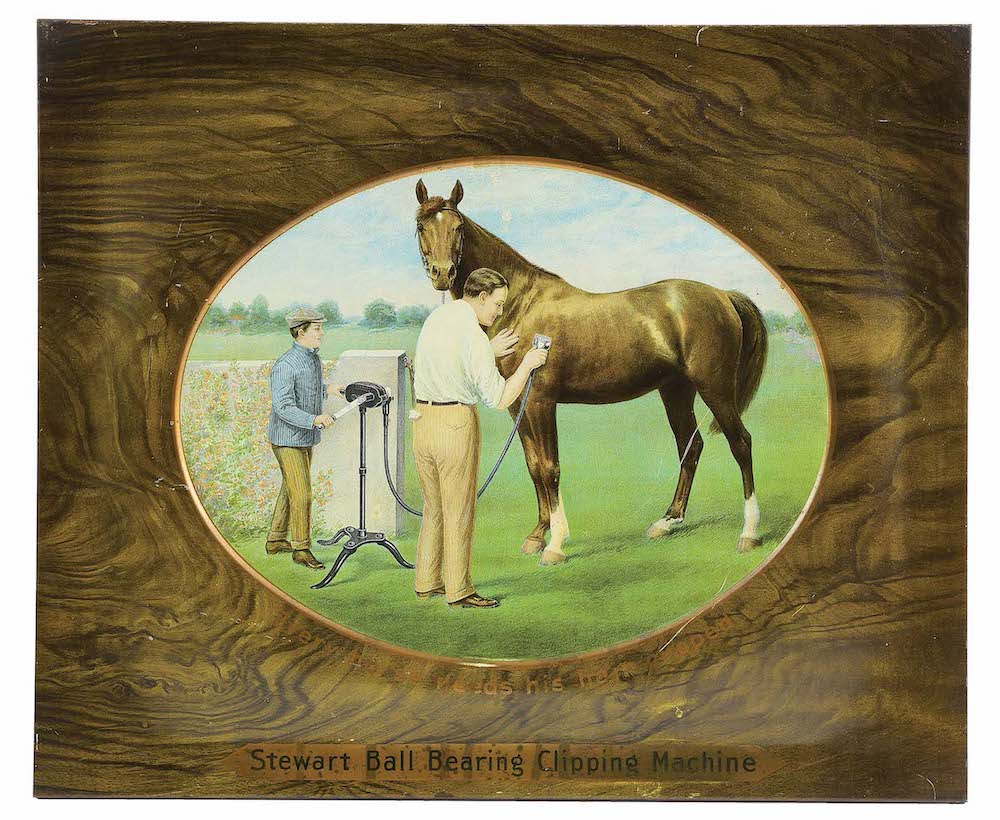

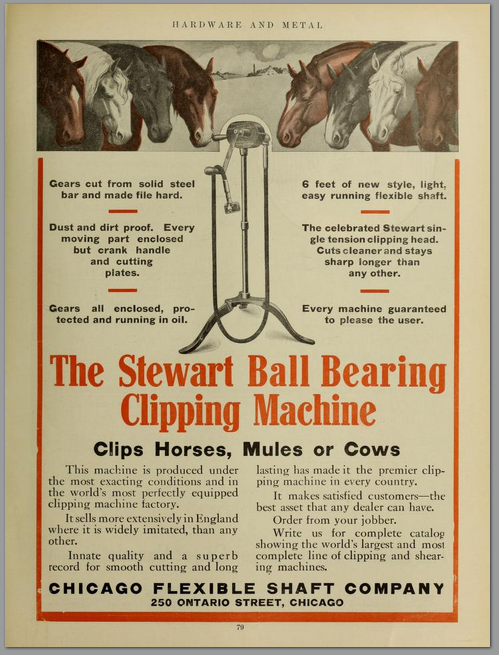

With his attention rapidly moving to new horizons like furnaces and auto accessories, John K. Stewart’s last great contribution to the clipping business was arguably the Stewart Ball Bearing Clipping Machine, which eclipsed the Chicago Clipper as the company’s top seller by 1908 [we believe the Stewart Clipper in our collection is a No. 1, but there were many numbered variations in the years before WWI]. This device was considerably smaller and came at a cheaper price tag, but it was advertised as “the surest, truest clipping machine ever devised. So good is it made in every respect that we unqualifiedly GUARANTEE it for 25 years.”

With his attention rapidly moving to new horizons like furnaces and auto accessories, John K. Stewart’s last great contribution to the clipping business was arguably the Stewart Ball Bearing Clipping Machine, which eclipsed the Chicago Clipper as the company’s top seller by 1908 [we believe the Stewart Clipper in our collection is a No. 1, but there were many numbered variations in the years before WWI]. This device was considerably smaller and came at a cheaper price tag, but it was advertised as “the surest, truest clipping machine ever devised. So good is it made in every respect that we unqualifiedly GUARANTEE it for 25 years.”

The Stewart Clipper took John K.’s self-given name across the Seven Seas to new customers as far away as Australia, South America, and South Africa. Key to that distribution was Stewart and Clark’s partnership with investors from a British firm known as William Cooper & Nephews—a well known manufacturer of barnyard pesticides. Since Cooper already produced the world’s No. 1 sheep dip, the marriage with the world’s top sheep and horse shearing business was logical and instantly lucrative. Together, they formed a subsidiary called the “Cooper-Stewart Sheep Shearing Machinery Company,” which not only proved a challenging tongue twister for salesmen to say, but also helped propel both businesses to massive profits on a global scale.

[Two men using an original Stewart No. 7 Clipper to shear a sheep in 2014]

At this point, Stewart and Clark—both now approaching 40—could easily have basked in their well-earned fortunes and given their weary brains a break. Instead, the two patent-hungry mavericks set their sights on a new industrial frontier, trading the farm field for the open road.

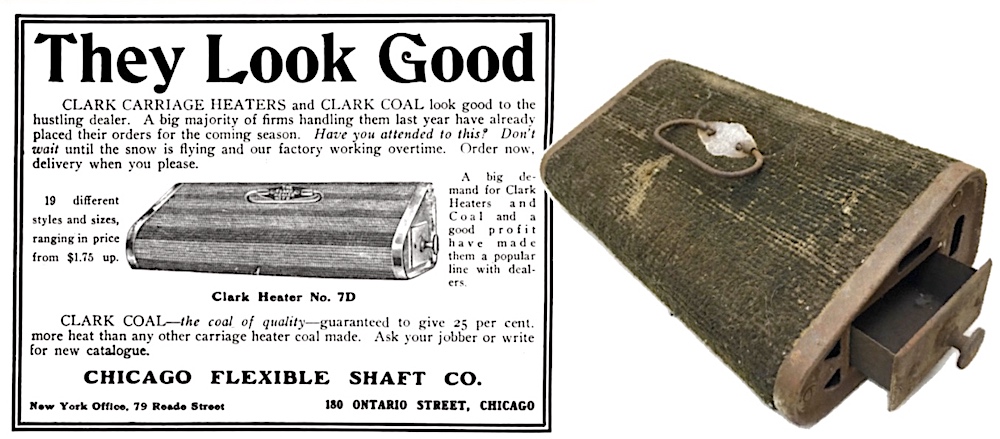

In 1905, they established the Sterk MFG Co. (a clumsy combination of their names, mercifully rebranded as the Stewart & Clark MFG Co. shortly thereafter), which soon opened its own plant at 1906 W. Diversey Blvd. in Lake View. The new company focused mainly on the production of parts and accessories for “horseless carriages”—using base materials directly from the Flexible Shaft Company to save on production costs. They produced various designs of early car horns, speedometers, and even miniature coal-burning foot heaters designed for winter driving. The latter, known as the Clark Carriage Heater, is another artifact represented in our museum collection.

[The Clark Carriage Heater in our collection is the No 7D model, as shown in this 1907 advertisement]

Some of the Sterk products were distributed in collaboration with the Chicago Flexible Shaft Co., but with William Cooper & Nephews now owning half of that company, the Brits and Yanks weren’t always on the same page in terms of the automobile’s role in CFS’s future. In particular, Stewart & Clark saw their new speedometer as the next great innovation for the automotive age. The design applied Stewart’s flexible shaft “as a connecting link between a gear on the front axle and the dash” of a vehicle, and early indications for its potential were off the charts. Unfortunately, Thomas Clark never got to see this dream realized.

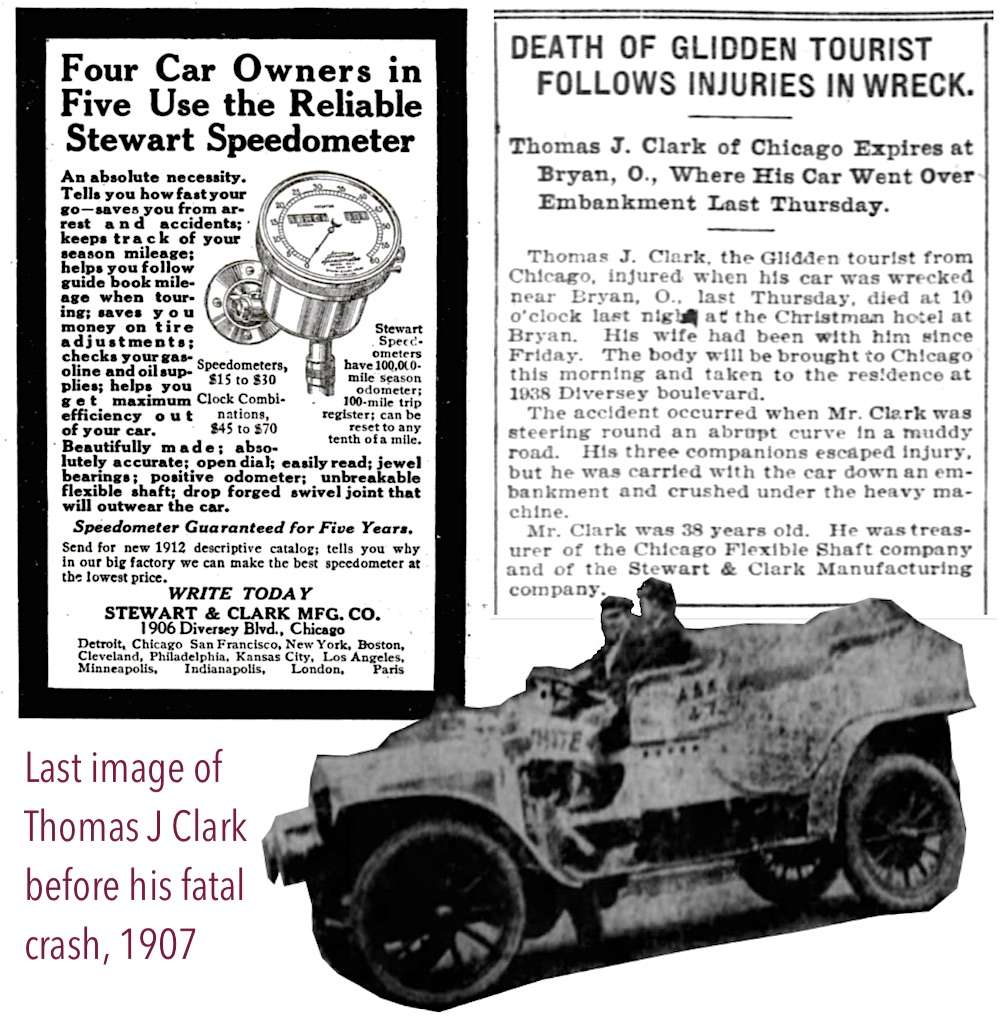

In the summer of 1907, the ever adventurous Clark signed up to race in the “Glidden Tour,” an American Automobile Association promotional, rally-style event. He was there specifically to showcase the Stewart & Clark speedometer, but while driving on a muddy road near Bryan , Ohio, his Packard spun out and crashed into a ditch. Initially, reports suggested that the injured Clark would survive his injuries, but his return to Chicago would prove to be a funeral procession.

John Stewart had been in lockstep with his friend Tom for over 20 years, going back to their childhood days in New Hampshire as O’Brien and Conlon. Now he would have to soldier on solo. It was a major turning point in the history of several influential Chicago businesses.

A year after Clark’s death, Stewart successfully sold the Stewart & Clark speedometer to the Ford Motor Company for use in the first Model T—a deal that would considerably dwarf even the success of his sheep-shearing empire.

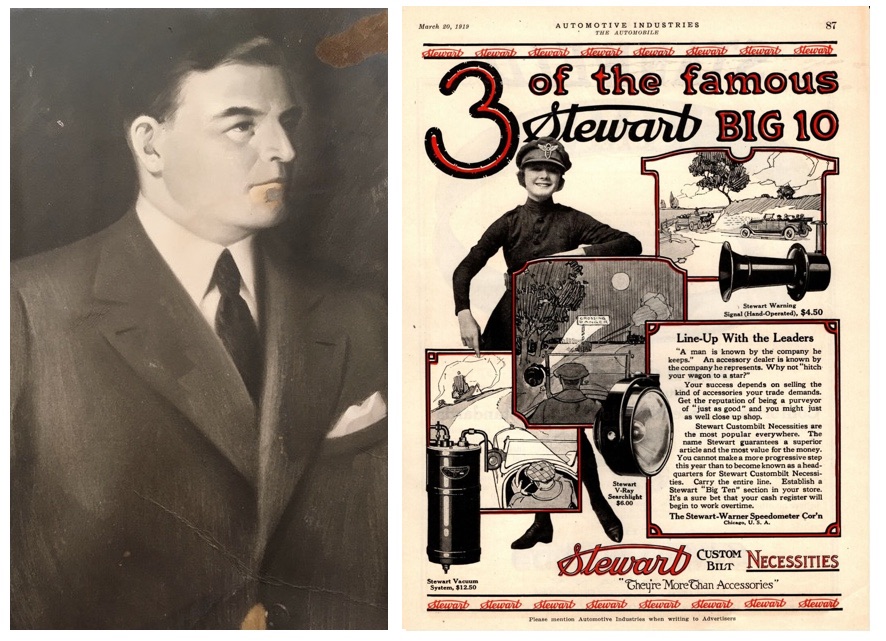

By no coincidence, Stewart decided to sell his remaining 50% ownership of the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company to Cooper & Nephews by the end of 1908. Taking some of that cash, he eventually purchased his biggest rival in the speedometer business, the Warner Instrument Company, and merged it with Stewart & Clark in 1912, forming what would become the Stewart-Warner Corporation—another one of the giants of 20th century Chicago industry. For his own amusement, Stewart also ran the J.K. Stewart Manufacturing Company and Stewart Phonograph Company up until his own untimely death in 1916.

[Left: John K. Stewart, circa 1910; image donated by Stewart’s great-grandson R. Stewart Honeyman, Jr.. Right: 1919 advertisement for the Stewart auto accessory line of the Stewart-Warner Co.]

Part III. The Sunbeam Also Rises

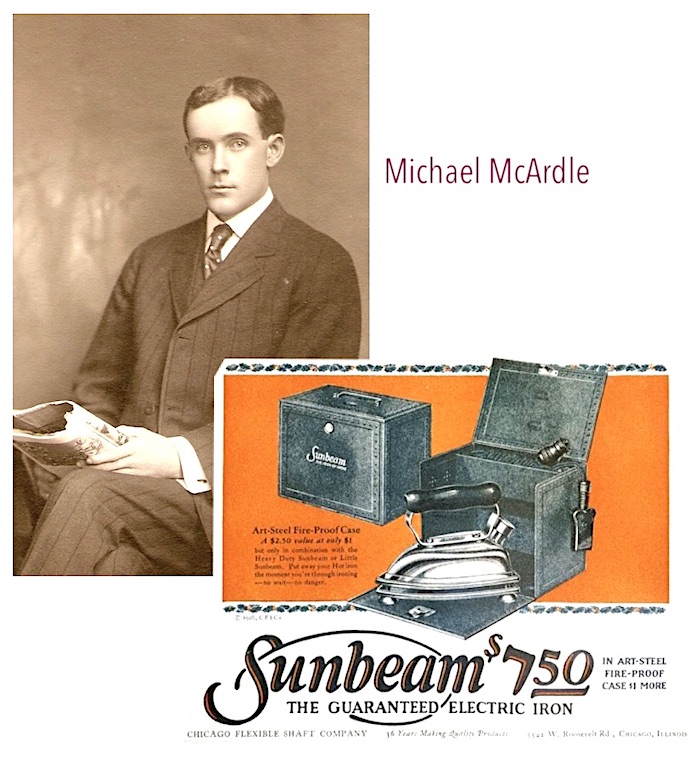

John Stewart’s departure from the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company could have spelled doom for its hopes of future innovation. But fortunately, his influence was still tangible. While Charles Timson of Cooper & Nephews took over the presidency of the company, there was fresh creative energy in the business, including John Stewart’s own nephew Leander H. LaChance and a standout salesman named Michael McArdle.

McArdle (b. 1874) had a law degree from the University of Wisconsin, and his talents of persuasion made him an effective advertising manager for Chicago Flexible Shaft for ten years. More than that, though, he proved himself a highly skilled engineer and product designer, helping to develop many of the new appliances that propelled the company into a second wave of success post-Stewart.

McArdle (b. 1874) had a law degree from the University of Wisconsin, and his talents of persuasion made him an effective advertising manager for Chicago Flexible Shaft for ten years. More than that, though, he proved himself a highly skilled engineer and product designer, helping to develop many of the new appliances that propelled the company into a second wave of success post-Stewart.

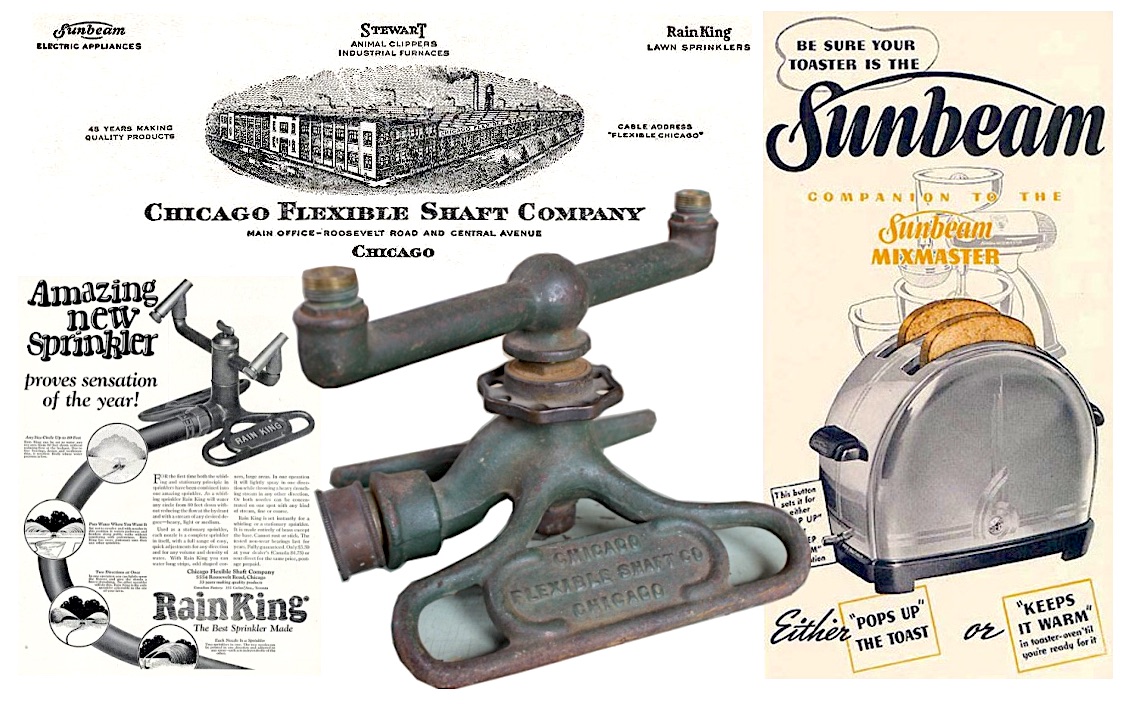

Starting in 1910 with the debut of the “Princess” electric flat iron, there was an aggressive push into mainstream products for commercial home use. Within a decade, this had grown to include toasters, grills, lawn sprinklers, and electric hair clippers . . . for human heads. By the time the company left its LaSalle Street HQ for a modern, sprawling plant at 5600 W. Roosevelt Road, they started using a more consistent brand name for many of these products . . . Sunbeam [supposedly standing for “SUN + “Best Electronic Appliances Made”].

Michael McArdle was named president of Chicago Flexible Shaft in 1927, and was joined by another prolific inventor and Renaissance man in the form of a Swedish engineer named Ivar Jepson. It was his arrival that launched the Sunbeam brand into national recognition, as a company once associated with animal grooming gradually shed its old image entirely, focusing on the shiny new gadgets of the modern age.

[Top: Depiction of the factory at 5600 W. Roosevelt, 1930 (the building has since been demolished); Bottom Left: 1923 ad for a Rain King sprinkler; Bottom Center: A 1920s Rain King sprinkler from our museum collection; Right: Ad for the Sunbeam Toaster, c. 1930s]

Following the death of Michael McArdle in 1935, new company president Horace Caldwell Wright faced the typical challenges of the Great Depression, combined with back-and-forth labor skirmishes (Chicago Flexible Shaft was sometimes accused of being anti-union, while at other times, union leaders within the company were accused of pushing Communist agendas). Nonetheless, Wright remained so confident in the desirability of Sunbeam products that he bought out the remaining shares still owned by William Cooper & Nephews, giving him full controlling interest in the business moving forward. From there, Wright continued to encourage Jepson and his engineering team—including George Scharfenberg and Ludvik Joseph Koci—to take big swings creatively, incorporating the streamlined trends of the ’30s into everything from electric razors to the hugely successful “Mixmaster” kitchen mixer. The company even outsourced design ideas to Chicago artists like Alfonso Iannelli, who’d worked with Frank Lloyd Wright and helped create many of the exhibitions of the 1933 World’s Fair—for Chicago Flexible Shaft, he provided a new look for the “Coffeemaster.”

Year by year, Sunbeam’s name recognition as a trusted brand had not only buried that of the Chicago Flexible Company itself, but essentially rendered it a silly relic of a bygone age by comparison. As such, in 1946, Horace Caldwell Wright (now serving as CEO) stuck the final fork in the full evolution of the business, celebrating the dawning of post-war America by re-naming the 50 year-old company the “Sunbeam Corporation.” The Chicago Flexible Shaft Company was officially no more.

Year by year, Sunbeam’s name recognition as a trusted brand had not only buried that of the Chicago Flexible Company itself, but essentially rendered it a silly relic of a bygone age by comparison. As such, in 1946, Horace Caldwell Wright (now serving as CEO) stuck the final fork in the full evolution of the business, celebrating the dawning of post-war America by re-naming the 50 year-old company the “Sunbeam Corporation.” The Chicago Flexible Shaft Company was officially no more.

Like its founder once did so many years ago, Sunbeam had given itself a new identity, and it seemed a wise move. The company employed roughly 2,500 people at its Roosevelt plant at the time of the change. By the 1970s, that number had ballooned to 30,000 workers around the world. Sunbeam ultimately exited Chicago altogether, like so many others, after a buyout in the early 1980s, and its products have bounced around among larger corporate owners ever since, most recently Newell Brands.

For a whole lot more on the company’s story in the decades after World War II, you can check out our Sunbeam Corporation history page here. If you’d rather catch up with John K. Stewart’s alternate legacy with the Stewart-Warner Corp., there’s plenty to unpack there, as well.

Sources:

“A Money Maker for Blacksmith Shops” – The Blacksmith and Wheelwright, Dec 1897

“A New Clipping Machine” – Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Nov 13, 1898

“A New World’s Record” – The Horse Review, Jan 17, 1905

“The Practice of Clipping Horses . . . ” – Holstein-Friesian Register, April 15, 1905

“How Some of the Glidden Tourists Look” – Times Recorder (Zanesville, OH), July 16, 1907

“Death of Glidden Tourist Follows Injuries in Wreck” – Chicago Tribune, July 16, 1907

“The Late John K. Stewart” – American Sheep Breeder, June 1916

“Tells Why John K. Stewart Left Home and Changed Name” – St. Louis Post Dispatch, Nov 21, 1921

“Strange Story of Terrence O’Brien, Factory Hand Who Became Stewart, Speedometer King” – St. Louis Post Dispatch, Dec 11, 1921

“Mrs. Honeyman Wins Fight to Control Estate” – Chicago Tribune, Jan 17, 1922

“O’Briens Lose Part in Stewart Fortune” – Boston Globe, June 1, 1923

“Huge Sunbeam Corporation Started Out Making Horse-Shearing Machine” – Scott County Times (Mississippi), April 3, 1963

“Michael McArdle: Baileys Harbor’s Benefactor” – Door County Pulse, Sept 1, 2012

I have a Stewart Handy Worker. It is mostly complete. Any info greatly appreciated.

A strong handsome gentleman in his earlier years became so expert at his chosen profession of shearing sheep, that he soon became widely known. ln July of 1929 the Flexible Shaft Company of Chicago, sponsored a national sheep shearing contest. This was held in Great Falls, Montana, and was the first of its kind ever held. It soon took on worldwide prominence as contestants gathered from all over the world, even from as far off as Australia. Well, to make a long story short, my great grandfather, Soren Otto Sorensen entered the contest. History records the rest. Let me share some excerpts from one of the numerous newspaper articles that were written.

“Mr. Soren 0. Sorensen, who last Thursday, won the Sheep Shearing Championship of the United States, has now returned home and is receiving congratulation from his many friends. Shearing 100 sheep in 3 hours, 38 minutes, Mr. Sorensen, of Ephriam, Utah, was declared National Champion in the contest held Wednesday and Thursday. Mr. Sorensen also placed first in three other features. Taking 29 minutes and 52 seconds to shear 10 sheep and shearing 27 animals in one hour.”

I would love more information, photos, newspaper articles, etc. regarding this event. What did the equipment look like that he would have used? Would you still have his application in your archives? Newspaper articles have been lost to our family; do you have them in your archives? I appreciate any correspondence from you.

Hello,

According to a newspaper source, Chicago Flexible Shaft Company operated a small factory on South First Street in West Dundee, IL in the 1890s to around 1900 when it was sold to Cutter and Crossette, a shirt factory out of Chicago and Elgin (it may have been a shoe factory before Chicago Flexible Shaft). Do you have any information on this factory? Thank you!

Edward Bates, Historian and Teacher

College of DuPage

I have a Stewart INDUSTRIAL FURNACE size #3 type HS

serial # 18663 fuel gas

made by chicago flexible shaft company

chicago USA

what can you tell me about my forge.history

I have a sheep shearing machine.

The placard reads:

THE

STEWART

BALL G. CARING

No. 9

SHEEP

SHEARING

MACHINE

MADE BY

CHICAGO

FLEXIBLE

SHIFT CO.

CHICAGO

U.S.A.

PATENTED

UNITED STATES

AND

GREAT BRITAIN

It’s in great condition, has the sheers, & works too.

I’ve been researching everything about this item, & the ones I’ve seen, are not as well preserved as mine.

I would like to know in what year was it made?

And how much could this be worth?

Thank you!

I have a Stewart Flexible Shaft horse clipper (ball bearing no 1)

What’s is value in Canadian money

I found a old sheep shering hand crank cutters idk what the price is on something like this

I believe I have an item of interest regarding Chicago Flexible Shaft Co. Going thru my ancestors belongings, I found a two-sided window poster advertisement. Dimensions are roughly 5×3 ft., est. year 1902, one side in full color reads atop in blue:

CLIP YOUR HORSES

-section containing a painting of a child operating the clipper, prices,

company info, etc.

B&W side:

THE 1902 CHICAGO

-contains descriptions and prices of 4-5 different models //

It is very old, in almost perfect condition, unfaded colors, has been folded up like a road map for 70+ years.

I’m not sure what to do with this item, as it seems very collectible, as well as fit for a museum. The age and quality of color/paper alone is a wonder. Preservation is a main concern. Any help or info on what can be done with this would be appreciated.

Jared, please feel free to email us at contact@madeinchicagomuseum.com with a few photos of the poster and we can discuss further.

Hi

I am just going to dispose of an old drag lure. The main mechanism was made from an old Stewart Clipper made by Chicago Flexible Shaft Co. Is it worth saving?

I live in Australia