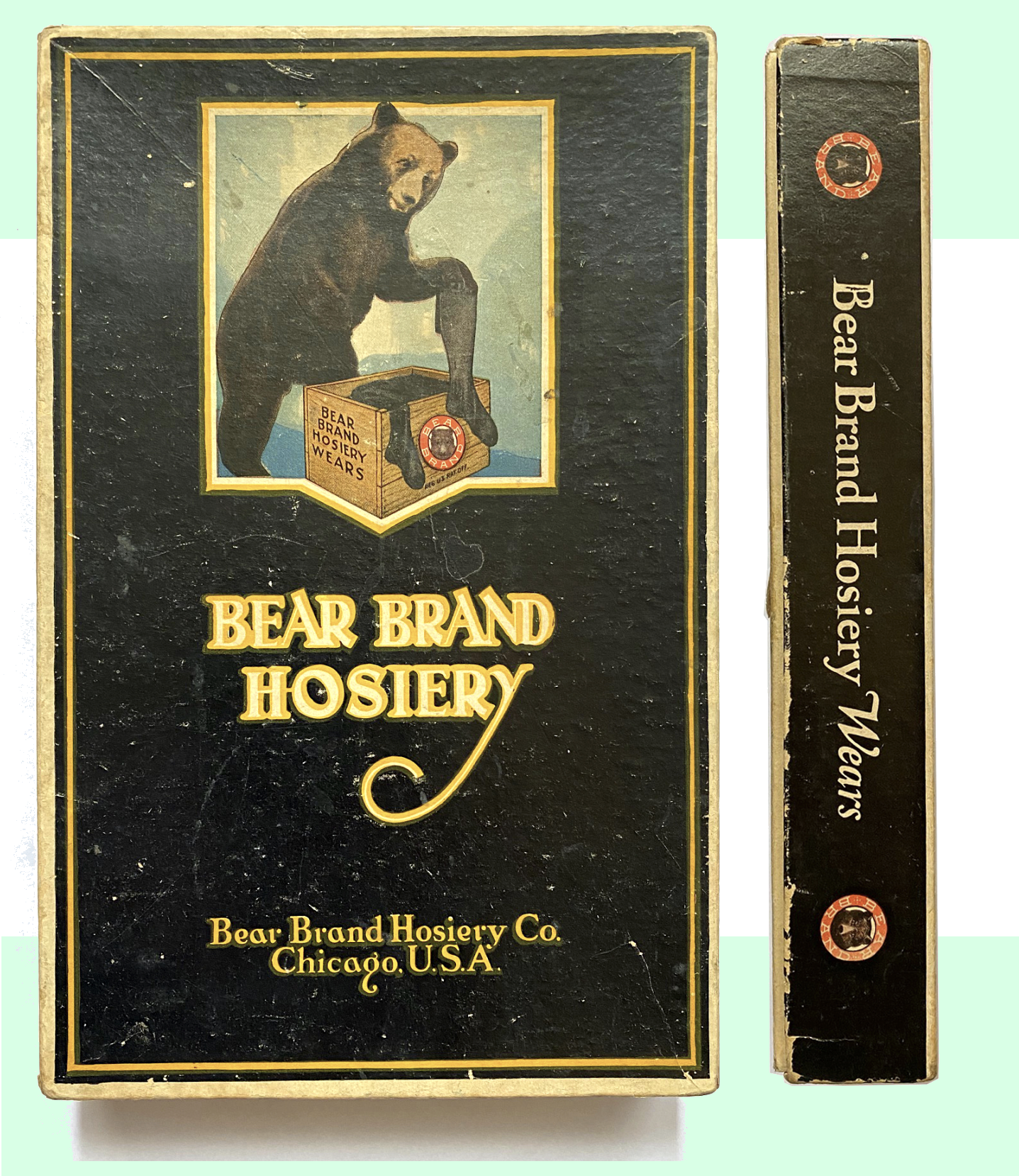

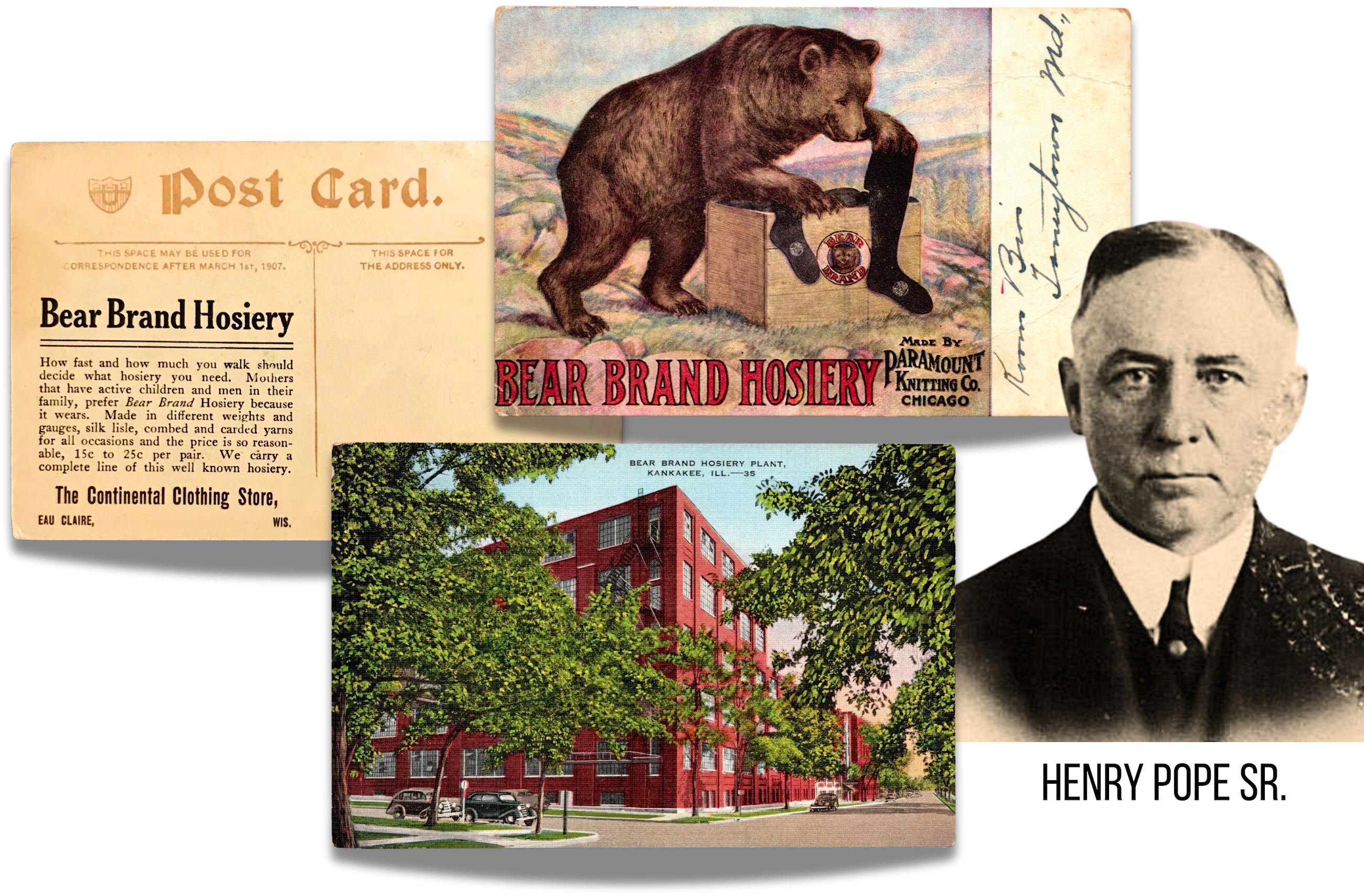

Museum Artifact: Bear Brand Hosiery Box – Women’s Hose 103 Biscayne, c. 1920s

Made By: Bear Brand Hosiery Company (formerly Paramount Knitting Co.), 337 W. Madison St., Chicago, IL [Multiple Factories – Including Kankakee, IL]

“I believe that hosiery is a very important factor in human comfort. The manufacture and sale of hosiery is a game worthy of the best interests and best efforts of any man.” –Henry Pope, president of Bear Brand Hosiery, 1919

Socks were getting something of a bad wrap in Chicago in 1919—this being the year of the infamous “Black Sox” gambling scandal, in which Shoeless Joe Jackson and seven of his Chicago White Sox teammates threw the World Series and were subsequently banned from baseball for life. A few miles from Comiskey Park, however, at the downtown offices of the Paramount Knitting Company, the outlook was decidedly more optimistic.

Socks were getting something of a bad wrap in Chicago in 1919—this being the year of the infamous “Black Sox” gambling scandal, in which Shoeless Joe Jackson and seven of his Chicago White Sox teammates threw the World Series and were subsequently banned from baseball for life. A few miles from Comiskey Park, however, at the downtown offices of the Paramount Knitting Company, the outlook was decidedly more optimistic.

“Out of the welter of war has come an opportunity for America to dominate the world so far as hosiery is concerned,” Henry Pope told the trade magazine The Underwear and Hosiery Review that year. “American hosiery the world over! That is a dream that can be made to come true if America goes into the world markets with an honest purpose to deliver honest goods at an honest profit.”

Pope had good reason for speaking in bombastic, senatorial platitudes. At the age of 50, he’d spent his entire life in the sock game, producing the hosiery itself as well as many of the new machines required for its high-volume manufacture. His success was evident in his ownership of six mills by 1920; the flagship operating 60 miles south of Chicago in Kankakee, Illinois, with five more satellite factories up in Wisconsin, employing more than 2,000 workers in total. Pope’s company, which he’d founded in 1893, was best known for its “Bear Brand” line, and by 1922—the same year the local pro football team changed its name from the Staleys to the Bears—Paramount Knitting officially announced its reincorporation as the Bear Brand Hosiery Company, with its world headquarters occupying the tenth floor of Chicago’s Hunter Building at 337 W. Madison Street (an early skyscraper that has long since been demolished).

A century onward, one’s first impression of this enterprise is, unavoidably, the mascot—not the typical smiling cartoon spokes-animal, but rather a fairly realistic depiction of an actual grizzly bear, bemusedly investigating a crate of Bear Brand stockings as if it were a disappointing picnic basket. The bear never wears the socks. The subliminal message seems to be, I suppose, that these socks are tough like their namesake beast. Over time, though, as the original apathetic and naturalistic bear mascot gave way to more dancing teddies and fully clothed anthropomorphized cubs, the whole concept got lost a bit.

[Left: Bear Brand salesmen, half of them dressed in bear suits and chained up like prisoners (???), promote their product, c. 1910s. Right: A promotional Bear Brand Hosiery teddy bear, 9″ in height, c. 1920s]

History of Bear Brand Hosiery, Part I: Franz & Pope

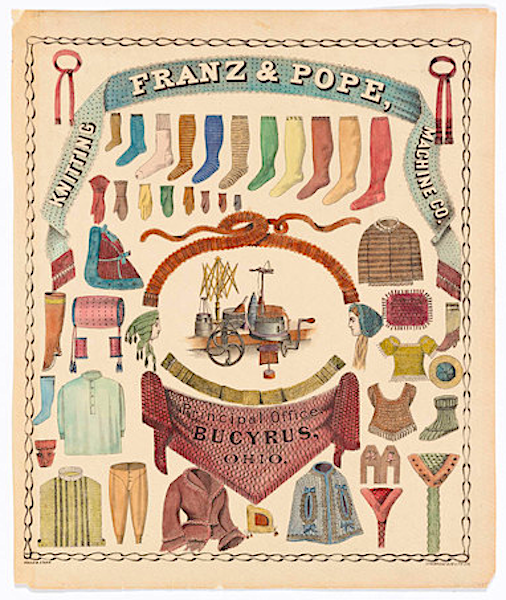

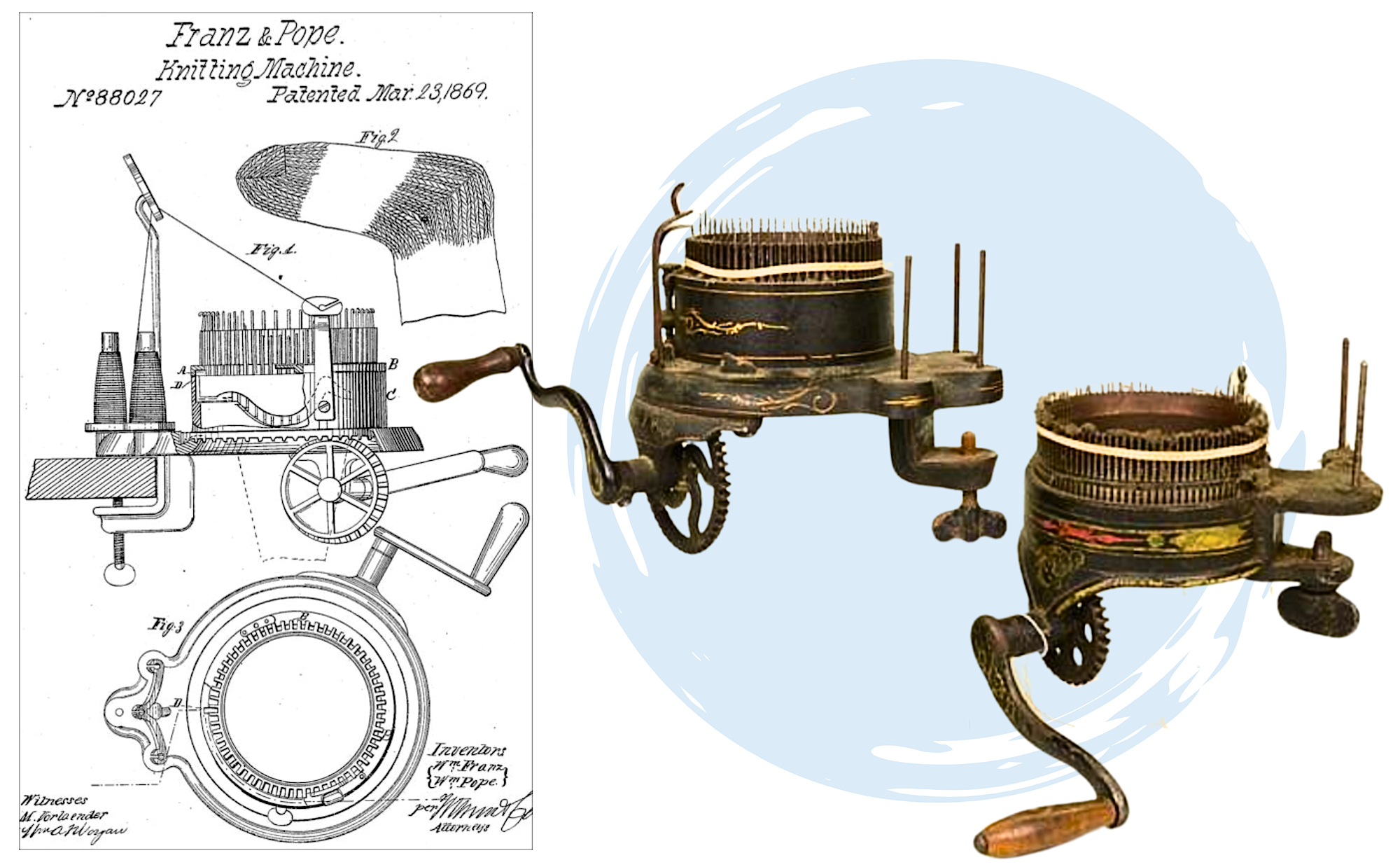

Henry J. Pope was born in Crestline, Ohio, in 1868, the fifth of seven kids raised by smalltown doctor William Pope and his wife Cornelia. When Henry was a small child, his father—perhaps bored by the limitations of practicing medicine in 1870s rural Ohio—took on a new hobby, co-inventing an automatic knitting machine with a local jeweler named William Franz. The duo soon abandoned their old lines of work to focus on promoting their new business, the Franz & Pope Manufacturing Company. Accordingly, the Pope family moved from Crestline to Bucyrus, Ohio, where Franz & Pope set up its first plant in the early 1870s.

By most accounts, the Franz-Pope knitting machine was an instant hit, as company salesmen would drag the devices by train to various exhibitions of the latest new pre-electricity tech gadgets, drawing large crowds of impressed onlookers. After one of these events in Buffalo, New York, in 1873, a reporter for the Buffalo Daily Express described his own awe at the invention.

By most accounts, the Franz-Pope knitting machine was an instant hit, as company salesmen would drag the devices by train to various exhibitions of the latest new pre-electricity tech gadgets, drawing large crowds of impressed onlookers. After one of these events in Buffalo, New York, in 1873, a reporter for the Buffalo Daily Express described his own awe at the invention.

“The first time we saw the Franz & Pope Knitting Machine, we stood half an hour watching the little wonder reel off stockings at the rate of one in seven minutes, and we won’t swear to it that our eyes didn’t stick out so one might hang his hat on them. . . . When you look at the machine, the simplicity of it strikes you forcibly. It runs very smoothly and easily, and you can work the crank either way at pleasure. We don’t wonder the mothers of families crowd about it. They can make all their family’s underclothes, stockings, sacks, bed quilts, anything, in fact, that can be knit by hand, in a twinkling of an eye almost, by a simple twist of the wrist. Of course they want one.”

Back in Bucyrus, young Henry Pope was clearly influenced by his father’s ambition and local acclaim, and quickly developed a similar, mildly demented degree of self confidence. As later retold in that 1919 profile in the Underwear and Hosiery Review, Henry “came home from school one day, bringing with him a stray dog that he had picked up along the road. Questioned as to the reason for the canine annexation, the lad told his parents that he was going to make the dog into a goat and drive him hitched to the wagon. The days which followed proved very trying for the dog, but young Pope transformed him into an animal possessing all the qualities of the goat except the odor, and drove him triumphantly hitched to a little red wagon, as per his declared program.”

Finishing high school at the age of 15, the ever-determined Henry immediately hit the road as a sales agent for Franz & Pope, introducing would-be buyers not only to the knitting machine itself, but a full line of sample knit products created on it. What good was an efficient device, after all, if it spun an inferior stocking?

[Franz & Pope’s circular knitting machine, an industry leader through much of the late 1800s]

By 1890, then, a 21-year-old Henry Pope already had an encyclopedic knowledge of all things socks: how they were made, what made one better than another, and what separated his family’s machine and methods from that of their many competitors; half of whom had been sued for patent infringement. Those legal battles, and the need to continuously update and upgrade elements of the knitting machine’s design, had left Franz & Pope in a bit of a precarious position—successful, but not wildly profitable. Then, in September of 1890, William Pope fell ill and died at his home in Bucyrus, aged 65, suddenly leaving the business in the hands of his baby-faced youngest son.

Franz & Pope had about 100 employees in Bucyrus at this point, but as debts mounted during an overall economic downturn over the next two years, young Henry Pope made the difficult but ultimately wise decision to seek greener pastures. He became a majority stockholder in a new business, based in Chicago, called the Paramount Knitting Company, which went into operation primarily to produce, box, and sell stockings, rather than sock-knitting machinery.

“With a breadth of vision which has been one of the important elements of his success,” Underwear and Hosier Review reported several decades later, “[Henry] Pope foresaw the day when knitting, as a fireside industry, would cease and when the world would look to hosiery manufacturers for the product of their machines.”

“With a breadth of vision which has been one of the important elements of his success,” Underwear and Hosier Review reported several decades later, “[Henry] Pope foresaw the day when knitting, as a fireside industry, would cease and when the world would look to hosiery manufacturers for the product of their machines.”

In 1895, Pope bid Ohio adieu and got to work at Paramount Knitting’s new Chicago office at 355 Dearborn. He didn’t have the capital or the square footage to hire a workforce, nor did he have enough contracts to sell off the remaining stock of Franz & Pope knitting machines. What he did have was a master plan for solving both of those problems. And for a man who would later be hailed for his “high ethical standards,” this part of the story is what we might call “evidence to the contrary.”

II. Paramount Goes to Prison

The use and/or exploitation of incarcerated men and women as unpaid labor is still a topic of some debate and controversy in the 21st century. Back in the 1890s, the issue was already a lightning rod, albeit with a bit less concern for the human rights of the prisoners themselves. The political outrage over the practice was stirred mainly by America’s rising labor unions, who quite rightly saw prisoner labor as a direct threat to the livelihoods of thousands of law-abiding factory workers.

Henry Pope, whether due to youthful naivety, financial desperation, or cutthroat tactical shamelessness, put himself and his brand new knitwear business at the center of this political firestorm, working out a deal with the governors of Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin to allow for the establishment of new knitting factories—equipped with Franz & Pope machines—inside at least half-a-dozen state prisons, including Old Joliet State Pen.

Henry Pope, whether due to youthful naivety, financial desperation, or cutthroat tactical shamelessness, put himself and his brand new knitwear business at the center of this political firestorm, working out a deal with the governors of Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin to allow for the establishment of new knitting factories—equipped with Franz & Pope machines—inside at least half-a-dozen state prisons, including Old Joliet State Pen.

The Chicago Tribune, reporting on this phenomenon in 1896, described Henry Pope as a mysterious grifter from Ohio. “He was not wealthy, but controlled a valuable patent. Just how he managed to convince Governor Altgeld that the use of the newest labor-saving machinery would tend to restrict the competition of convicts with free labor perhaps no one but he and the Governor could tell. [Pope] was comparatively a stranger here, but he secured his contracts.”

Those contracts, by just about any measure, were wildly lopsided in Pope’s favor, and they basically built the groundwork for the future success of Paramount Knitting and Bear Brand Hosiery. In the Illinois deal, Pope agreed to pay the state 20 cents per day for each prisoner in the knitting plant. In return, according to the Tribune report of 1896, “The State furnishes the buildings in which the work is done, lights and heats them, furnishes store-room for the raw material, and also for the finished products; feeds, clothes and lodges the laborers, and allows the company sixty days time in which to pay the 20 cents.”

[The shoe factory at Old Joliet Prison, pictured above on the left, operated in the 1890s at the same time as the Paramount Knitting Shop in the same penitentiary. The shoe operation was contracted out by the firm of Selz, Schwab & Co.]

The agreement also stated that Paramount Knitting could select its own superintendent for each facility—Henry’s older brother was installed at the prison in Waupun, Wisconsin—and that all repairs of knitting machines had to be handled by Franz & Pope; a massive inconvenience and added expense for tax payers.

Despite the massive profits Pope raked in from these deals, little of the benefit seemed to go back to the Franz & Pope plant back in Ohio. Instead, Henry concerned himself with using his gains to build up the reputation of the Paramount Knitting Co. in Chicago, which was soon providing stockings to some of that city’s biggest mail order houses and department stores. By 1897, the Franz & Pope Works in Bucyrus, OH, had shut down and the stock sold off. Henry Pope had killed his father’s business with an eye for building something more sustainable. His use of prisoners as his primary workforce, however, wasn’t going to remain a viable part of that strategy.

It wasn’t that Pope had decided that the use of prison labor was unethical, or that he’d come around to the arguments of labor unions. Basically, when his contracts were up for review toward the end of the century, most of the cooperating states realized they’d been bamboozled, and the majority of the penitentiary deals were not renewed (Waupun State Pen in Wisconsin being a notable exception). Paramount Knitting would have to do things the old fashioned way and start hiring its workers from the general populous.

III. Yes We Kankakee

“Bear Brand Hosiery is made from yarn spun in the mills of the Paramount Knitting Co., from fine, long staple American cotton that is given the Bear Brand twist to stand the hardest usage. Each pair is accurately sized by being knit on different diameter machines, which ensures perfect fit. . . . They will out-wear two pairs of ordinary hose and will cost you less money.” —newspaper ad for Bear Brand Hosiery, 1911

In 1901, a 33-year-old Henry Pope, now flush with cash, set about choosing a new site to serve as Paramount Knitting’s flagship factory complex. He landed on the town of Kankakee, Illinois, and within a year, had made his new plant the top employer in that town, putting 800 locals to work; with no requirement of a criminal record.

In 1901, a 33-year-old Henry Pope, now flush with cash, set about choosing a new site to serve as Paramount Knitting’s flagship factory complex. He landed on the town of Kankakee, Illinois, and within a year, had made his new plant the top employer in that town, putting 800 locals to work; with no requirement of a criminal record.

Henry installed another of his brothers, Frank Pope, as the superintendent of the Kankakee Works, while brother William took over a new, non-prison plant in Hartford, Wisconsin.

Over the next decade, Paramount’s headquarters remained in Chicago while the Kankakee facility was repeatedly expanded. The company had established a recognizable trademark, Bear Brand hosiery, and could now market more directly to consumers, as retail shops across the country touted the “whole bear family” of stockings produced in the Paramount works. Their target audience was a new generation of Americans who thought of socks as something more likely to be purchased in a store than knitted at home. A colorful mascot and modern boxed packaging was helpful in getting across that idea; delivering a simple pair of stockings in the same fashion as a nice pair of gloves.

There were, naturally, numerous sub-categories of Bear Brand socks, as well, offering up a variety of options depending on the wearer and their specific needs. A 1909 newspaper ad includes mentions of Moccasin Men’s Half Hose (“a fine gauge combed yarn stocking that ensures perfect ease and comfort”), Bear Skin Hose (“the best medium weight stocking ever made to stand the wear and tear required of children’s hosiery”), The Record Sock (“perfect for wear, fit and comfort”), Two-Step Hose (“nothing finer in children’s hosiery”), and Base Ball: The Popular Stocking (“a pennant winner every season of the year”).

Bear Brand advertising usually spoke to “mothers” and “wives” as the expected purchaser of these goods, but they were rarely the intended wearer. Durable socks, it was supposed, were not the personal concern of a lady.

During World War I, the Paramount Knitting mills were put into partial government service, producing socks and eventually a new type of reusable, knitted surgical gauze for the soldiers overseas. Henry Pope, well established as a first class political operator, also managed to get himself a seat on the Council of National Defense, chairing a committee concerned with knitted goods. The sorry state of Europe, he believed, could work to his own benefit in peacetime, as he believed American sock exports could open up a whole new potential industry.

By 1919, with the war just concluded, Pope had 2,000 employees—most of them in Kankakee, with a smaller portion at mills in Beaver Dam and Waupun, Wisconsin. Paramount was now able to produce up to “7,500 dozens of hosiery daily,” according to the Underwear and Hosiery Review, which is another way, we think, of saying 45,000 pairs of socks per day.

By 1919, with the war just concluded, Pope had 2,000 employees—most of them in Kankakee, with a smaller portion at mills in Beaver Dam and Waupun, Wisconsin. Paramount was now able to produce up to “7,500 dozens of hosiery daily,” according to the Underwear and Hosiery Review, which is another way, we think, of saying 45,000 pairs of socks per day.

“As the Paramount company has progressed and prospered, Mr. Pope has not been content to sit idly by and enjoy the fruit of his success,” that same magazine reported. “He is too brimful of energy and enthusiasm to be idle for a minute. He is constantly looking around for new ideas and new methods not only for improving his own business, but for improving the industry in general.. . . He never hesitates, but is a man of action.

“All these years he has been making dogs into goats,” the article continued, calling back to that childhood story of Henry’s adopted pooch, “and there is nothing he enjoys more than a perplexing problem that seemingly defies solution. Mr. Pope is not, however, a driving man. He succeeds because he is able to win the cooperation, friendly, interested cooperation, of those with whom he is associated in business. One reason for the splendid spirit of cooperation which he receives is that he is a most democratic man. His private office stands wide open. The humblest employee is always sure of a hearing. He is never too busy to be friendly and courteous.”

[Bear Brand postcard, c. 1910; postcard of the Kankakee works, c. 1930s; Henry Pope, c. 1920s]

IV. Reinforced Heels, Polio Braces, and Busted Unions

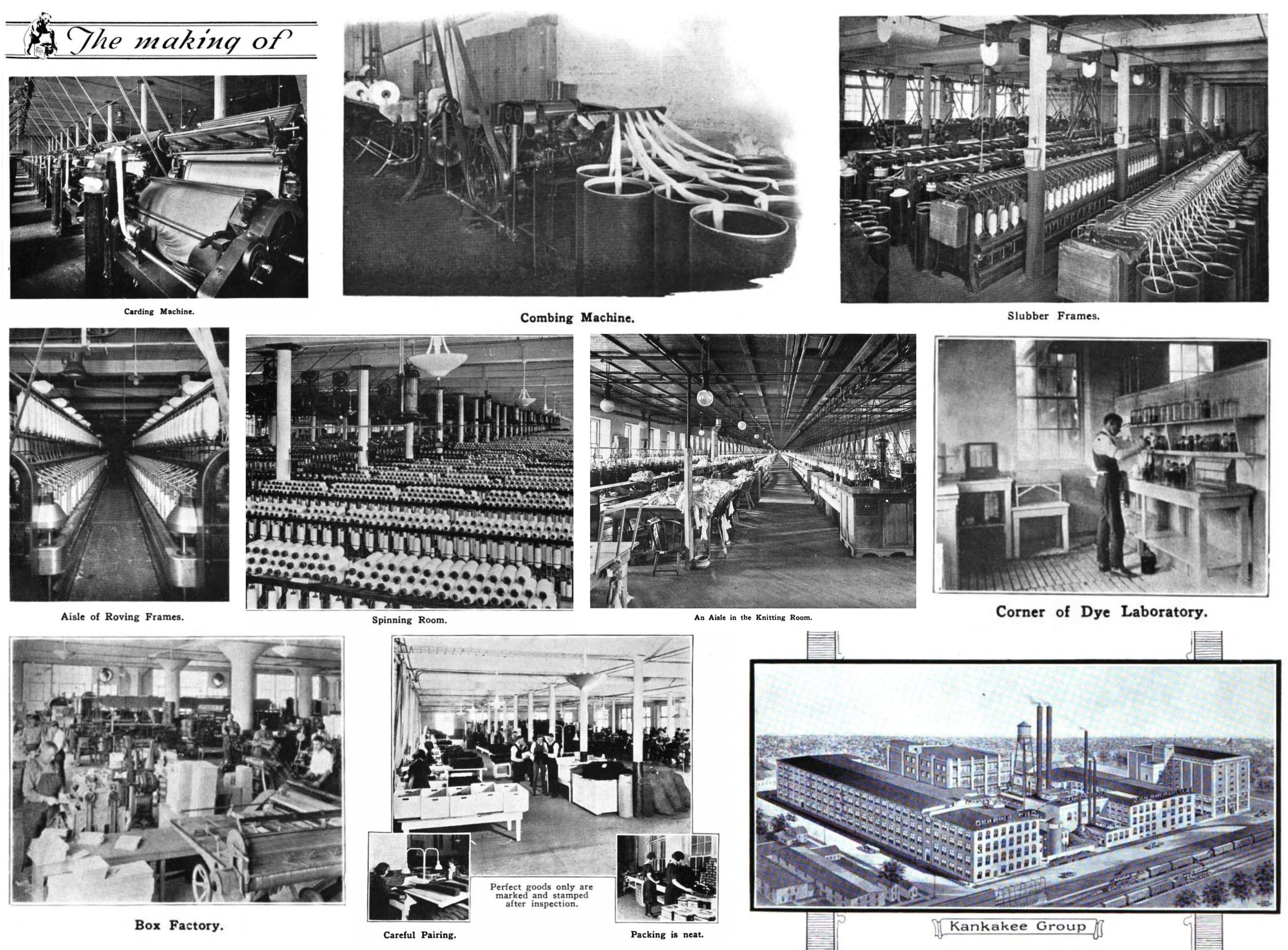

“The automatic machines used in knitting Bear Brand Hosiery are the finest and most improved known to the textile industry They draw the yarn in at the ankle, thus ensuring perfect fit and shape to the leg. They also throw in extra yarn automatically at the knee, the heel and toe, all points where ample reinforcement is vital. An experienced operator can tell from the sound alone just what part of the stocking a machine is knitting.” —The Making of World Famous Hosiery, published by the Bear Brand Hosiery Co., 1923

Just shy of the 30th anniversary of the Paramount Knitting Company, in 1922, the business was reorganized under the name of its long-running flagship product. The Bear Brand Hosiery Company was now among the largest family-owned businesses in America. And while it was still headquartered in Chicago as it had been since its inception, occupying a whole floor of the Hunter Building at Madison and Market Street, the undisputed “home” of the business was certainly Kankakee, where the sprawling Bear Brand factory was the hub of the town and a source of pride.

Just shy of the 30th anniversary of the Paramount Knitting Company, in 1922, the business was reorganized under the name of its long-running flagship product. The Bear Brand Hosiery Company was now among the largest family-owned businesses in America. And while it was still headquartered in Chicago as it had been since its inception, occupying a whole floor of the Hunter Building at Madison and Market Street, the undisputed “home” of the business was certainly Kankakee, where the sprawling Bear Brand factory was the hub of the town and a source of pride.

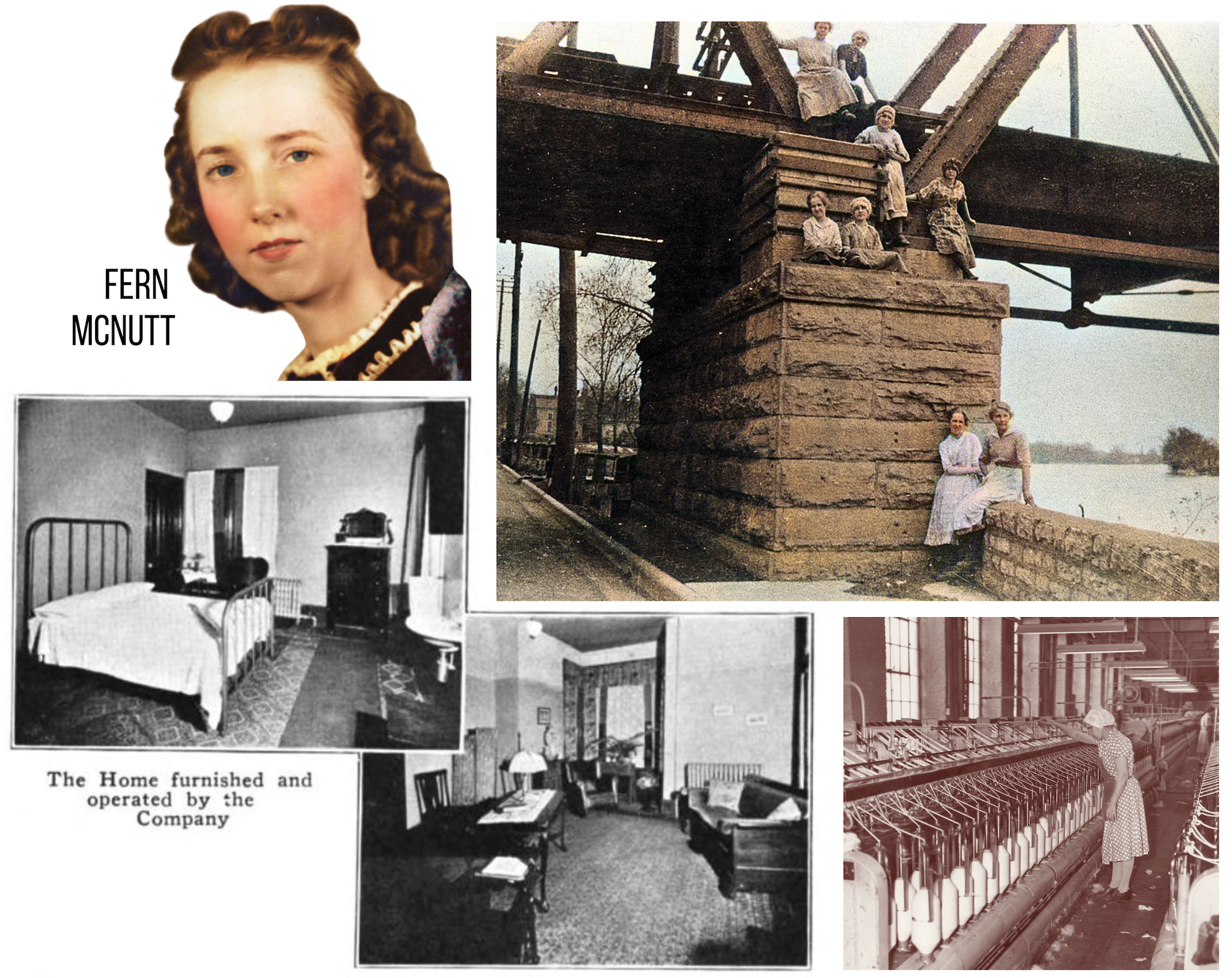

For hundreds of women and girls, in particular, it was an opportunity to earn a living and develop a sense of independence. One such example, a Kankaee girl named Fern Swanson, left school to start work at the Bear Brand mill in 1929, when she was just 15. In the ensuing years of the Great Depression, Fern (who became Fern McNutt after marrying in 1941) “always handed over her entire paycheck to her mom to help the family,” according to a story shared by her grandchildren following Fern’s death in 2010. “From the very beginning, Fern was a diligent worker. It created a strong work ethic in her that continued her whole life through.”

Bear Brand employed many girls just like Fern, and had a responsibility to give them a decent working experience, if only for the convenience of worker retention.

“The question of sanitation and physical care is well met,” the company boasted of its own facilities in 1923, “since the contented, healthy worker is the one who maintains production.”

[With hundreds of women working at Bear Brand’s Kankakee Works in the 1920s, the company had to provide boarding options for many of its employees who’d come from other towns. In the above right image, a group of women take a break between shifts at the Kankakee & Seneca Railroad Bridge]

A boarding house was built on-site for girls who traveled far from home to work at the plant, and there was also access to a cafeteria and womens-only restrooms. The male employees were given first dibs at moving up the corporate ladder, of course, but any employee with three years experience could take part in Bear Brand’s Savings and Profit Sharing Pension Fund . . . so long as you were earning your keep.

“No man loses his identity in the Bear Brand mills,” the company claimed in its 1923 promotional booklet The Making of World Famous Hosiery, “but he is continually under a personal scrutiny, with the view that he is placed where he can do his best work, and develop his particular abilities to the advantage of himself, and consequently, the company.”

Sock Production Inside the Kankakee Works, 1923

The actual progressiveness of Bear Brand’s mills during the Henry Pope era leaves a lot to be desired, and not just from a distant 21st century perspective. The company took plenty of heat for continuing to exploit prison labor in Waupun, Wisconsin, well into the 1930s. And labor disputes were not uncommon in Kankakee and across the company’s Midwestern network, as Henry Pope made clear his diametric opposition to collective bargaining and of new labor laws that limited the number of hours his female employees could work in a day. Throughout the 1920s, many Bear Brand workers were asked to put in double shifts—often stretching from 6am to 11pm—and when such hours were ruled illegal in Wisconsin, Pope threatened to shut down his plants in the state.

During the Great Depression, an aging Pope—now in his 60s—was similarly enraged by the works programs introduced by President Franklin Roosevelt, believing FDR and his cronies were trying to “overthrow the American social order.” When 300 workers at the Bear Brand plant in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin, went on strike, Pope was ordered by the government to meet their demands and pay the new federally mandated minimum wage. Pope responded by shutting down the factory and penning a vicious response to Roosevelt’s department of labor. “For your information the Bear Brand Company no longer operates a plant at Beaver Dam and employs no hosiery workers there,” Pope wrote. “Its plant was forced to go out of business on account of uncontrollable public riots.”

Officials of the Hosiery Workers Union responded that this so-called riot was “non-existent except in Pope’s mind.”

Henry Pope’s hatred for labor unions, and particularly his paranoid views about President Roosevelt’s policies, are all the more disappointing when one considers that Pope, just a few years prior, had befriended FDR after a very personal shared experience.

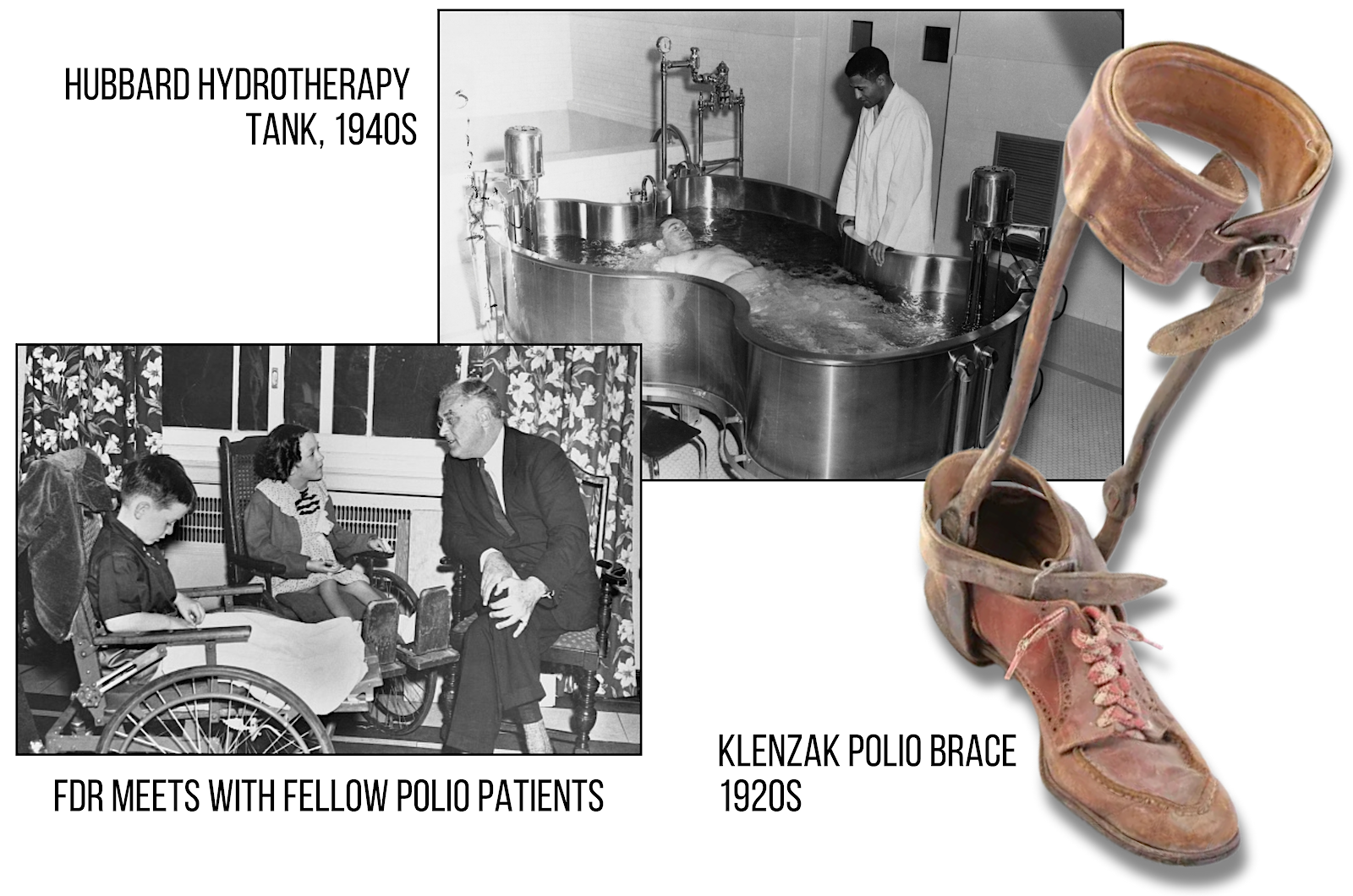

Pope’s adult daughter Margaret had contracted polio in the early 1920s, and at a specialist hospital in Boston, they met a 39 year-old Franklin Roosevelt going through the same physical therapy treatment for his own condition. Despite having zero overlap in their politics, a bond was formed between the two men nonetheless, and it remained intact as Henry Pope–to his credit—put a considerable amount of his own work into the improvement of treatments and mobility aids for polio victims.

During the ‘20s, Pope recruited a machinist named John Klenzak, an employee of one of Bear Brand’s subsidiary companies—the Paramount Textile Machinery Company—to experiment with new types of leg braces. Klenzak eventually designed a lightweight brace made from hollow steel tubing, known as the Klenzak Brace, which was widely adopted across the country. Another Pope employee, Carl Hubbard, invented the Hubbard Tank as an early hydrotherapy solution for polio sufferers.

In 1926, Pope even joined forces with Roosevelt and several other investors to purchase the Warm Springs hydrotherapy resort in Georgia, which they supported with the creation of the nonprofit Warm Springs Foundation. Later, in 1934, Henry established the Pope Foundation as another nonprofit dedicated to “the alleviation of human suffering and disease.” There was, clearly, a beating heart of empathy in the man, even if his employees may not have missed him much upon his retirement in 1936.

[Bear Brand advertisements in a 1936 of the Nathan Shure Co. catalog]

V. The New Pope

Henry Pope, Jr. (1903-1991) took over the Bear Brand presidency in 1936, which now had additional mills operating in Gary, Indiana, and Henderson, Kentucky, as well as an international sister site in Liverpool, England. Pope Jr., like his dad before him, had grown up in the sock and stocking business and lived and breathed it with a similar no-compromise policy. He was also similarly put in charge of the family business at a relatively young age (33). Bear Brand, however, was light years beyond the small potatoes Franz & Pope operation that Henry Sr. had inherited back in the 1890s.

Pope Jr. had hundreds of employees rather than dozens, and immediately had to navigate a major economic depression and, shortly thereafter, another world war. The deaths of his uncle Frank Pope (1942), Bear Brand’s vice president J. H. Kelly (1944), and his father Henry Sr. (1947) around this same period also left the post-war fate of the family business firmly in Junior’s hands.

Pope Jr. had hundreds of employees rather than dozens, and immediately had to navigate a major economic depression and, shortly thereafter, another world war. The deaths of his uncle Frank Pope (1942), Bear Brand’s vice president J. H. Kelly (1944), and his father Henry Sr. (1947) around this same period also left the post-war fate of the family business firmly in Junior’s hands.

Over time, it became clear that the new Pope was a loyal acolyte of the old one, and followed many of the same policies, including numerous examples of trying to break up union organizers among the company’s ranks. He also had the same knack for gaining favor with political influencers, earning himself an appointment as the director of the Illinois OPA (Office of Price Administration) during World War II, followed by a term as president of the Illinois Manufacturers Association in the 1950s.

Women’s hosiery was now a bigger part of the Bear Brand business, and in the years after the war, the network of Bear Brand mills expanded to seven, with 1,700 people employed across facilities in Paxton, Illinois; Kearney, Nebraska; Siloam Springs, Arkansas; and Fayetteville, Arkansas; to go along with the plants in Gary, Henderson, and Kankakee. Bear Brand was no longer at the forefront of innovation when it came to machining, however, and Henry Pope, Jr., was well aware of what falling too far behind could mean as the industry evolved.

Speaking to the local newspaper in Kearney in 1958, Pope acknowledged that “the next four years will see a continual readjustment in our industry as the population reacts to stretch socks and other longer wearing products. We are gearing our sales and manufacturing organization to the specific challenge of these next four years, and stressing product and new revolutionary merchandising techniques that will assist Bear Brand to sell more goods to more and more of America’s growing population. And behind all of our programming is the prime concern for maintaining our high quality standards that have been the greatest reason why we have been able to maintain our success for 65 years.”

Looking at how things played out in the 1960s, it doesn’t appear that Bear Brand’s “revolutionary” game plan entirely paid off. In quick succession, the company’s satellite plants began to close, starting with Kearney, which shut down in 1960 just two years into the “four year plan.” Paxton followed in 1963, then Gary in ‘65. The people of Kankakee now anticipated the worst. From the Chicago office at 131 S. Wabash Avenue, stockholders discussed the uncomfortable subjects of consolidation and future leadership.

The decision, which was a familiar one for many manufacturers of this period, was to head south, where non-union labor was cheaper and regulations were less restrictive. Along with the existing mills in Fayetteville and Siloam Springs, two additional Arkansas facilities opened in Bentonville and Rogers in the mid 1960s. By 1968, hundreds of machines were moved out of the Kankakee Works and transported down South, and by the end of the decade, the majority of the Kankakee complex had already been unceremoniously demolished.

[Demolition of Bear Brand’s Kankakee Works, 1969]

Despite appearances, though, Bear Brand wasn’t dead yet. In Arkansas, with Henry Pope, Jr. still serving as company chairman, the firm shifted even more of its production and marketing towards the women’s pantyhose market.

At Bear Brand’s national sales meeting at the Fayetteville Holiday Inn in 1970, guests were treated to a “psychedelic, choreographed fashion show” emphasizing the “hosiery needs of the liberated woman,” the Northwest Arkansas Times reported. New hosiery styles on display included “those for the woman with a generous figure, thigh-high styles for future fashion in longuette (mid-length) dresses, an over-the-calf style for wearing with pants suits, styles for the young or early teen petite figure, and a nude pantyhose with only the waistband unconcealed.”

In 1971, the Bear Brand board elected 50-year-old Allen J. Buckreus as the new company president—the first non-Pope in the role. Buckreus’s own father had managed Bear Brand’s Gary plant for many years, so a certain legacy was still in tact. “While the hosiery industry, like all other industries in the country, is feeling some of the adverse effects of the general economy,” Buckreus told workers at a company event that year, “Bear Brand is stronger than it has ever been in its industry. Bear Brand has new mills, new machines, and the highest skilled people making hosiery anywhere in the country.”

In 1971, the Bear Brand board elected 50-year-old Allen J. Buckreus as the new company president—the first non-Pope in the role. Buckreus’s own father had managed Bear Brand’s Gary plant for many years, so a certain legacy was still in tact. “While the hosiery industry, like all other industries in the country, is feeling some of the adverse effects of the general economy,” Buckreus told workers at a company event that year, “Bear Brand is stronger than it has ever been in its industry. Bear Brand has new mills, new machines, and the highest skilled people making hosiery anywhere in the country.”

Throughout the 1970s, the company’s corporate headquarters remained in Chicago, at 205 West Monroe St., while production was wholly centered in Arkansas. With growing competition from cheaply-made imports, though, any hope of a new golden era gradually diminished as the decade unfolded. Each of the four Arkansas mills closed just as the Midwestern plants had, and by the time of Henry Pope Jr.’s death in 1991, Bear Brand had vanished from the marketplace, just shy of its 100th anniversary.

Sources:

“The Franz & Pope Knitter Abroad” – Telegraph-Forum (Bucyrus, OH), Nov 29, 1873

“Embarrassed: The Franz & Pope Knitting Machine Co. Placed in Serious Financial Straits” – Telegraph-Forum (Bucyrus, OH), Dec 20, 1895

“Driving Out Free Labor” – Chicago Tribune, Oct 4, 1896

“Henry Pop, President of Paramount Knitting . . .” – Waupun Times, Sept 5, 1899

“President Pope of the Paramount” – Waupun Leader-News / Underwear & Hosiery Review, July 4, 1919

The Making of World Famous Hosiery – Bear Brand Hosiery Co., 1923

“Death of ‘Biddy’ Pope Recalls Some Early Crestline History” – Crestline Advocate (OH), Jan 22, 1925

“Union Men to Attend Mass Meeting Tonight” – Green Bay Press-Gazette, July 21, 1926

“Bear Brand Hosiery Co. Beat Women’s Eight-Hour Bill” – The Unionist (Omaha, NE), Aug 14, 1931

“Hosiery Factory Closes Down” – Oregon Labor Press, May 18, 1934

“Henry Pope Sr. Dies, Noted as Philanthropist” – Chicago Tribune, Jan 8, 1947

“Bear Brand Hosiery Marking Its 65th Year” – Kearney Hub, Jan 25, 1958

“Fashion Show is Feature of Sales Meeting” – Northwest Arkansas Times, June 3, 1970

“263 Employes Attend Bear Brand Dinner” – Northwest Arkansas Times, May 22, 1971

“Buckreus New President of Bear Brand” – Northwest Arkansas Times, Dec 23, 1971

“Henry Pope, 88, Head of Hosiery Firm (obit)” – Chicago Tribune, Aug 22, 1991

“Rise and Fall of Bear Brand” – The Times (Hammond, IN), Feb 13, 2022

I have original photos from the early 1900s of store fronts of Bear Brand hosiery’s . Any interest?

My great grandfather was Henry Pope (grandmother was Margaret Pope – the one who got polio & who the brace was invented for) and I came across this as I was digging around for family history. The only memorabilia I have is a small framed advertisement for Bear Brand Hosiery

I worked at Bear Brand Hosiery in Chicago. My job was to separate the carbon paper from the green lined computer paper. It was my second job and I was 16 years old. It was 1969 and I remember wearing pantyhose for the first time.

If you have any vintage Paramount Knitting Company or Bear Brand Hosiery boxes, socks, post cards, photographs, advertisement, marketing material, please contact me at bearbrandhosiery@gmail.com. Check out our Facebook Page at https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100063646717082

I found a Super Soft (TM) Bear Brand box of Pantyhose in a San Carlos, CA, thrift store. Looks to be high quality compared to the hose I remember from the 1980s. I’m glad I don’t have to wear pantyhose anymore. Never opened. I’ll be selling them on eBay. I wish I could post a picture here. It’s a very retro but also kind of generic-looking package.

While going through my parents items, I found a Bear Brand Hosiey box (in extra fine condition). It once contained 6 pair “Royal Canadian” Asst’d size 10 1/2. The picture on the box is a bear standing over a box of hosiery with labled “BEAR BRAND HOSIERY WEARS”. On the bottom of the box is a stamp with “569G236” on it. What can anyone tell me about the contents and/or date it was used? Thank you. Ted Kadlecek, Rocky Ford, CO 81067

While cleaning out our parents home I came across a

Bear Brand Hosiery walking Bear card, The legs move…..Can anyone tell me anything about this?

I found a yellow post card size with 5 brown bear punch outs, indicating Daddy Bear and 4 small bears. Bottom left of card, 1937 Bear Brand Hosiery Co.

On opposite side of card, an interesting statement, “Boys and girls would be gay Wear BEAR BRAND HOSE for school or play!

Good condition! Anyone interested in purchasing this card?

I just found a lid from a “Bear Brand Hosiery Wears” box, and wondered if the company is still

in business.