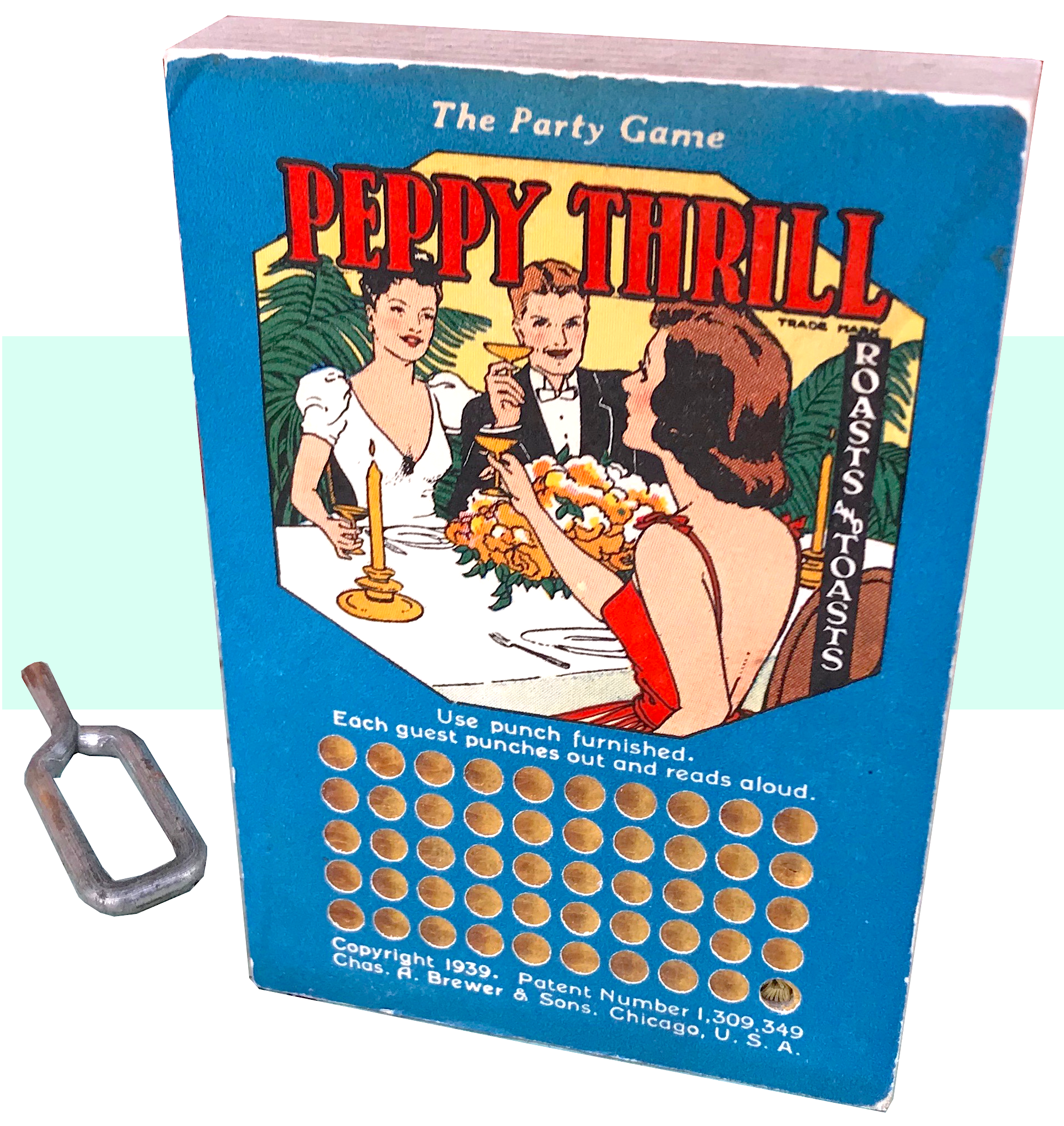

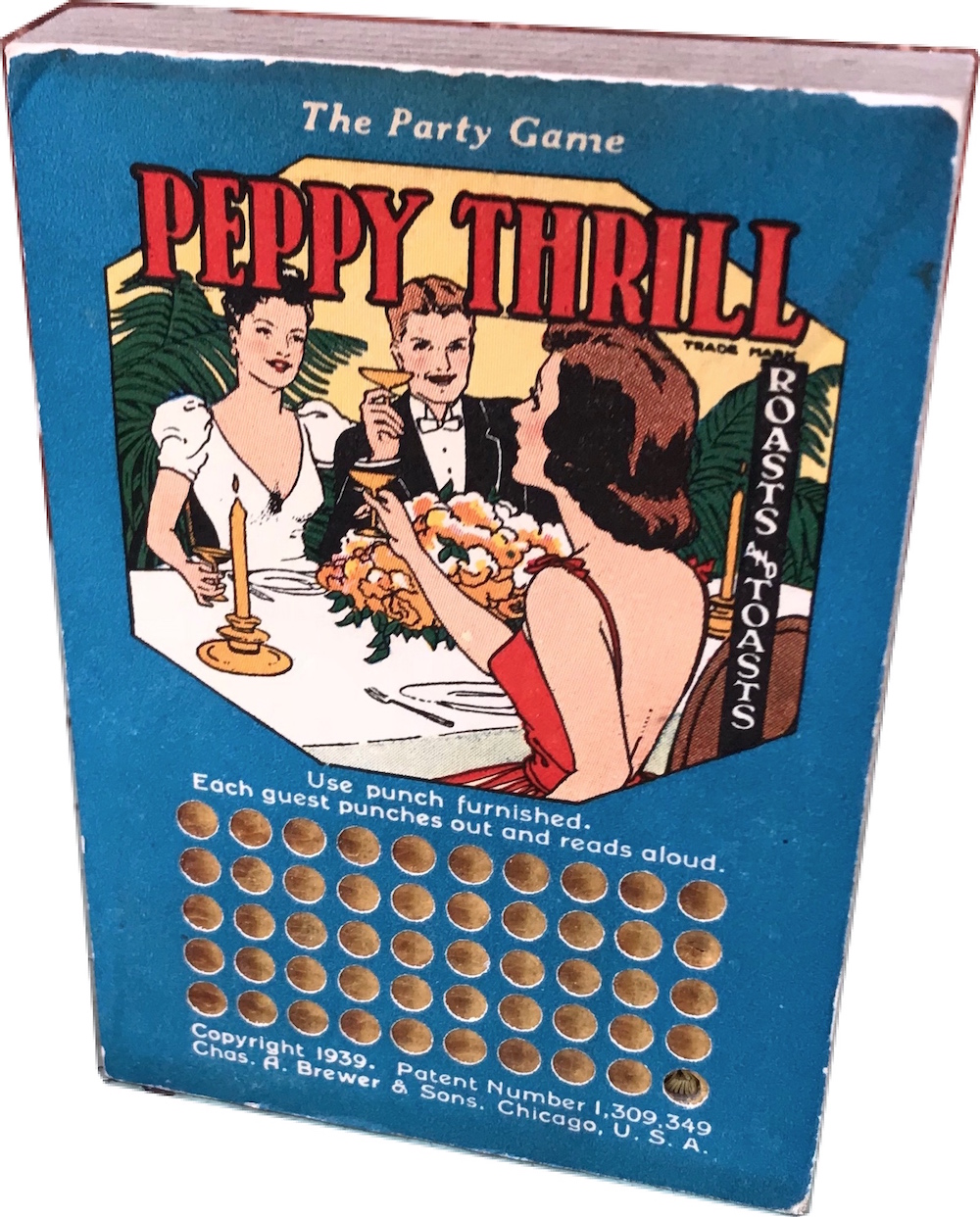

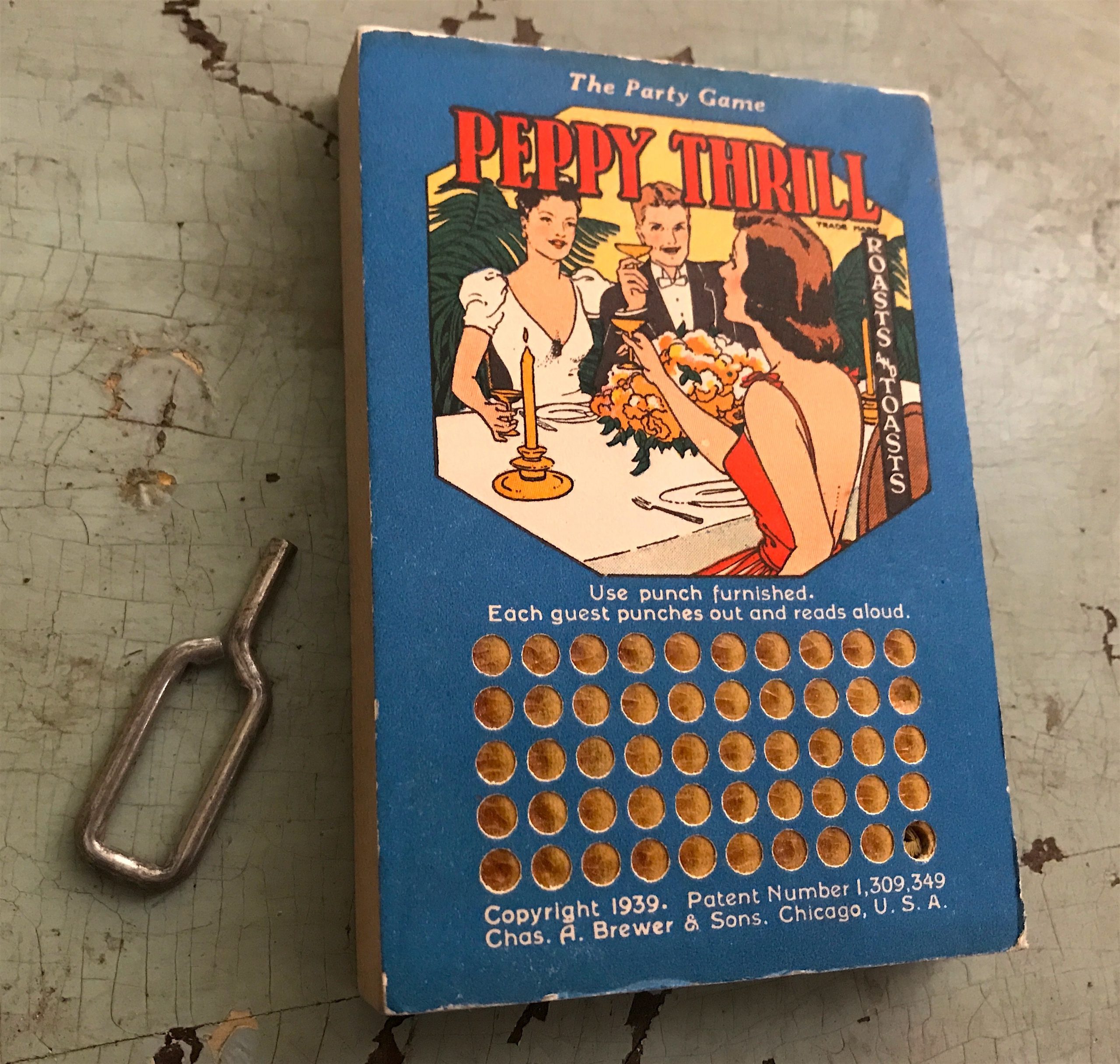

Museum Artifact: Peppy Thrill Punch Board Game, 1939

Made By: Chas. A. Brewer & Sons, 6320 S. Harvard Avenue, Chicago, IL [Englewood]

“One out of every three adults plays a punchboard or slot machine. More people do this than play church lotteries, the horses, and numbers games—all three combined.” —Samuel Lubell, Saturday Evening Post, 1939

Produced the very same year as the article quoted above, this palm-sized “Peppy Thrill” punchboard takes us back to the pre-war apex of America’s perforated gambling obsession—when an estimated 50 million of these colorful cardboard games were sold in a single calendar year alone. They were, in some respects, the scratch-off lottery tickets of their day—albeit dangerously unregulated and routinely connected with organized crime (rather than just the dis-organized crime of state lotto commissions).

Whether used as trade stimulators by shopkeepers, grifting tools by gangsters, or—as in the case of Peppy Thrill—as a supposedly innocent dinner party game for “roasts and toasts,” punchboards (aka sales-boards or push cards) were as ingrained into the culture as fedoras and cigarettes. And nobody made more of them than the Chicago company Chas. A. Brewer & Sons.

History of Chas. A. Brewer & Sons, Part I: “First In The Business”

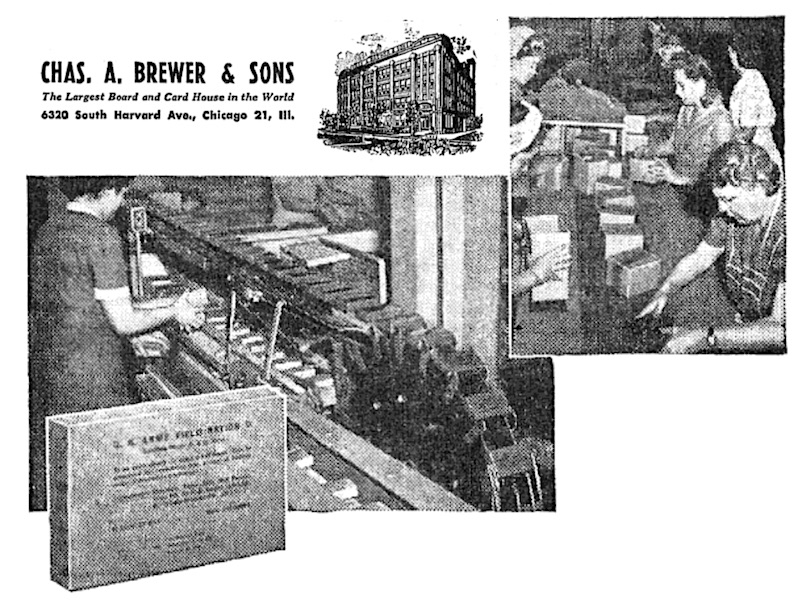

Not only did Charles Brewer manage the “The Largest Board and Card House in the World,” he was also widely recognized as the father of the entire punchboard industry.

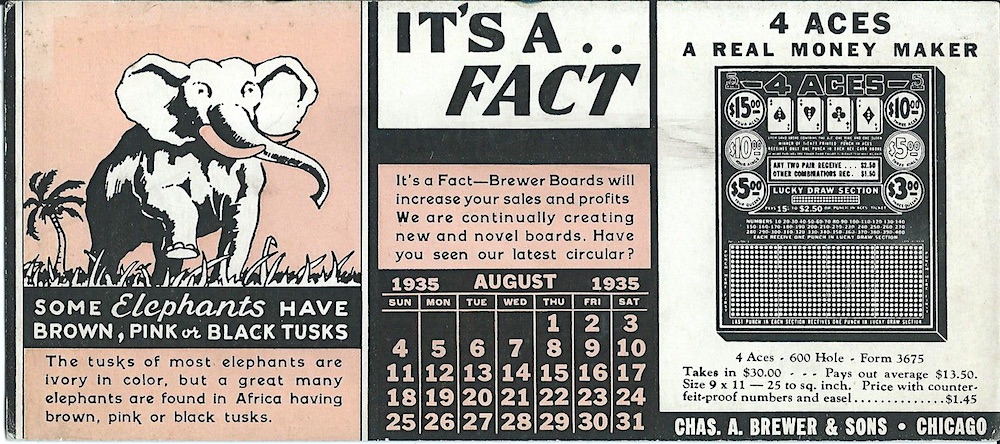

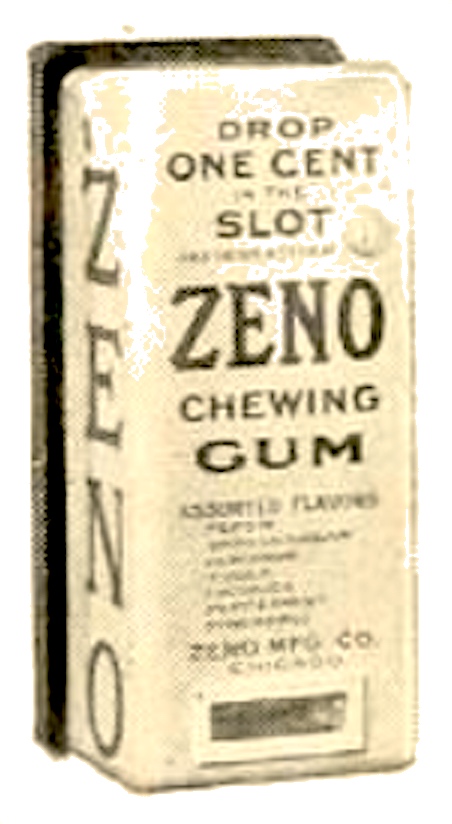

Born in Ohio during the Civil War, Brewer was indoctrinated into the world of industrial management through the exploits of his immediate family members. His father Nelson C. Brewer was GM of Cleveland’s Rubber Paint Company, and older brother William N. Brewer became one of the organizers of the Zeno Gum company. In the 1890s, Charles moved west to work as a salesman for Zeno in Chicago, bringing along his wife Kittie and their three young sons, Nelson (b. 1886), Kenneth (b. 1887), and Everett (b. 1890).

Since Zeno was a successful chewing gum brand AND the official supplier to a certain Mr. William Wrigley, Charles Brewer was well positioned to absorb all the latest commercial sales tactics of the day—including the use of vending machines, counter displays, and promotional tie-ins.

Since Zeno was a successful chewing gum brand AND the official supplier to a certain Mr. William Wrigley, Charles Brewer was well positioned to absorb all the latest commercial sales tactics of the day—including the use of vending machines, counter displays, and promotional tie-ins.

Trade stimulators (coin operated “games of chance”) were certainly big at the time, too, but they were still stuck a bit in the Wild West era—oversized, impractical machines that were hard to mass-produce and even harder to keep in working order. Charles Brewer, keen market analyst that he was, recognized the potential for a simpler version of this device—something that was cheap to make, easy to operate, and perfectly positioned between the worlds of gambling and advertising.

If you believe an account later described in that 1939 issue of the Saturday Evening Post, “Charles Brewer, the inventor of the punchboard, got his idea by attending a party where forfeit slips were drawn out of a hat. All Brewer did, in a sense, was to substitute a board with holes for the hat.” The result, for all intents and purposes, was the fully realized 20th century punch board—a literal game changer.

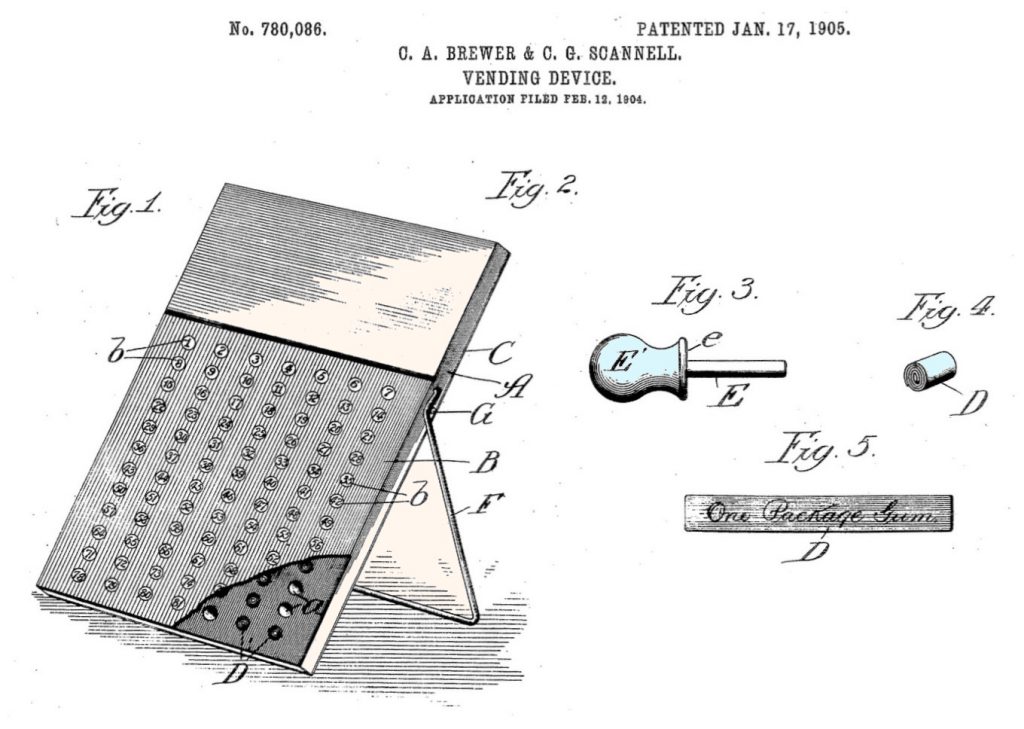

In 1904, while still employed by Zeno, a now 41 year-old Brewer partnered with a man named Clinton G. Scannell to apply for a patent on this “new and useful improvement in vending devices,” as seen below.

“The object for which the invention is principally designed,” Brewer and Scannell wrote in their application, “is to promote the introduction and sale of merchandise . . . such, for instance, as chewing gum, cigars, etc. . . . through a novel mode and instrumentality of advertising and vending a line of goods, accompanied by orders for a limited number of premiums or gifts that are distributed with the goods.”

The Federal Trade Commission gave us a bit of a clearer summary of the object, and its objective, years later:

“Punch boards contain a certain number of holes in which are placed slips of paper bearing different numbers or legends. These slips of paper are effectively concealed from view. Persons desiring to ‘play’ the board pay to the operator thereof a designated sum, and thus become entitled to punch the board and to remove therefrom one of the slips of paper. Certain specified numbers or legends on the slips entitle purchasers to designated articles of merchandise without additional cost. Purchasers who do not punch a lucky or winning number receive nothing for their money other than the privilege of playing the board, or in some cases merchandise which is of much less value than that which would be received if lucky numbers were punched.”

Sure sounds like an illegal gambling operation. But, by claiming the paper slips would correspond only to merchandise rather than cash, Brewer had apparently skirted the legal obstacles. The U.S. Patent Office gave the “vending device” its stamp of approval in January of 1905. The gold standard had been set.

Sure sounds like an illegal gambling operation. But, by claiming the paper slips would correspond only to merchandise rather than cash, Brewer had apparently skirted the legal obstacles. The U.S. Patent Office gave the “vending device” its stamp of approval in January of 1905. The gold standard had been set.

While Brewer almost certainly used some of his earliest punchboard models to sell Zeno gum in the first decade of the 20th century, few if any artifacts of those promotions have survived. It’s not until 1911—the same year William Wrigley bought out Zeno and took over its manufacturing—that we see Charles Brewer break out on his own and bring his invention into the wider world.

Part II: The Devon MFG Co.

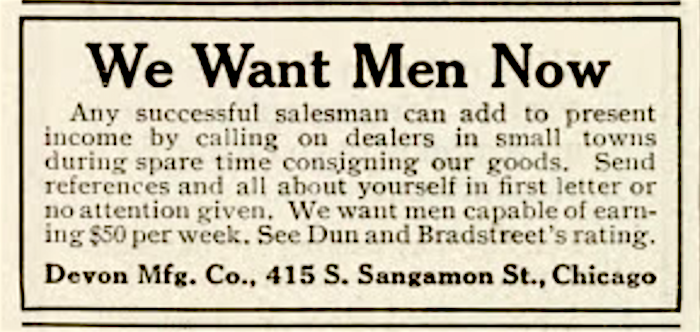

The first iteration of Brewer’s punchboard business was called the Devon Manufacturing Company, and its original offices were located at 415 S. Sangamon St., just a block down the road from the factory of another former Zeno man, F.B. Redington. It’s unclear if Charles had roped his sons into the business just yet. We do know, however, that Brewer was aggressively recruiting salesmen across the country to help promote both the goods and the larger concept to shopkeepers.

[Devon MFG Co. wanted ad from 1911]

[Devon MFG Co. wanted ad from 1911]

From the outset, the Devon MFG Co. handled a lot more than just the machining of cardboard blocks and paper cards. Brewer was establishing a whole new business model, in which his company would provide the game board (stuffed with the paper slips), custom advertising on said board, and even the prizes themselves—likely sourced from local Chicago confectioners and jewelers. A client would pay for the use of the game, then send back a hefty percentage of the profits to the Devon MFG Co. as its supplier. A casino boss always gets his cut.

We know the basics of this scheme thanks to a small blip of a court case from 1917, when Charles Brewer—still doing business as the Devon MFG Co.—tried to collect on a punchboard debt owed by two store owners in Alabama. Brewer wound up losing the case and an appeal, as the judge deemed the punchboard illegal trade in Alabama, thus voiding the original contract. Still, to the benefit of future generations, the records from the “Brewer v. Woodham” case left us with an actual, word-for-word copy of the sales contract that the Devon MFG Co. used to send to its buyers:

“Devon Manufacturing Company, Chicago, Ill. Please ship to my address by prepaid express one assortment No. 8 at $40.00, terms 60 days, less $5.00 if remittance is made in 10 days from date on invoice. If remittance of $40.00 is made thirty days from the date of invoice, you agree to ship to my address, making no charge for same, my choice of premiums shown on your illustrated list; or if at the end of thirty days I remit 80 per cent. of the gross receipts, which is 8 cents for each sale, you agree to take back any unsold goods at price charged me, provided they have been offered for sale as per printed directions for sixty days from date of invoice, at which time final settlement is to be made. The assortment consists of 8 watches, 92 pieces of jewelry and cutlery, and 400 packages of chocolates. You agree to place in center of tray an extra watch for which no charge is made. This watch to be used as per printed directions or returned by me with unsold goods. No salesman has authority to collect money or goods or make settlement of this account. It is understood that I have no agreement with you except as herein stated. [Customer sign here.] __________.”

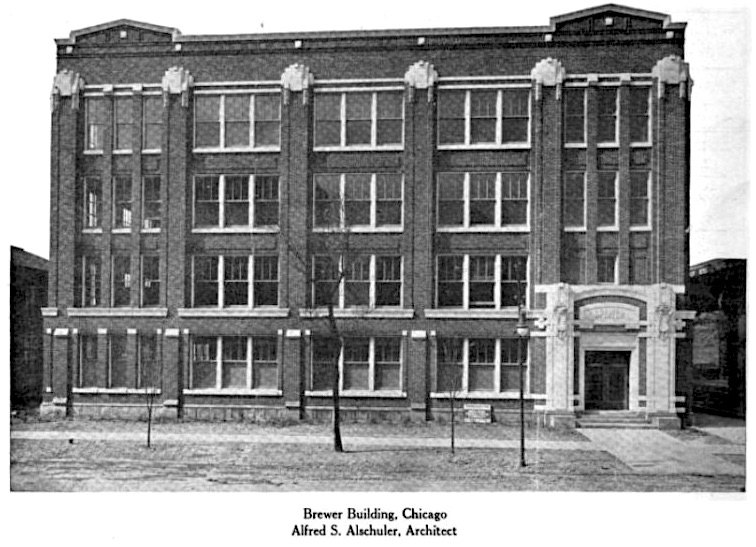

While Brewer lost some money on that Alabama deal, he didn’t suffer any legal consequences for his blatantly obvious gambling operation. In fact, business was good enough—and above ground enough—that he officially welcomed his sons Nelson, Kenneth and Everett into the fold with a 1917 rebranding as Chas. A. Brewer & Sons. The new company was headquartered in the Englewood neighborhood at 6320 S. Harvard Avenue, a four-story building that the Devon MFG Co. had moved into a couple years earlier.

III. Harvard Thinking

It was in the Harvard Avenue plant that this daring little punchboard business grew into a full-scale, major manufacturing company—the largest of its kind in the world, employing more than 200 workers.

Charles Brewer, now in his 50s, wasn’t content to just remain “the guy who invented the punchboard.” He wanted to see his creation through to its fruition, and to do so, he continuously looked for new ways to improve its use and production.

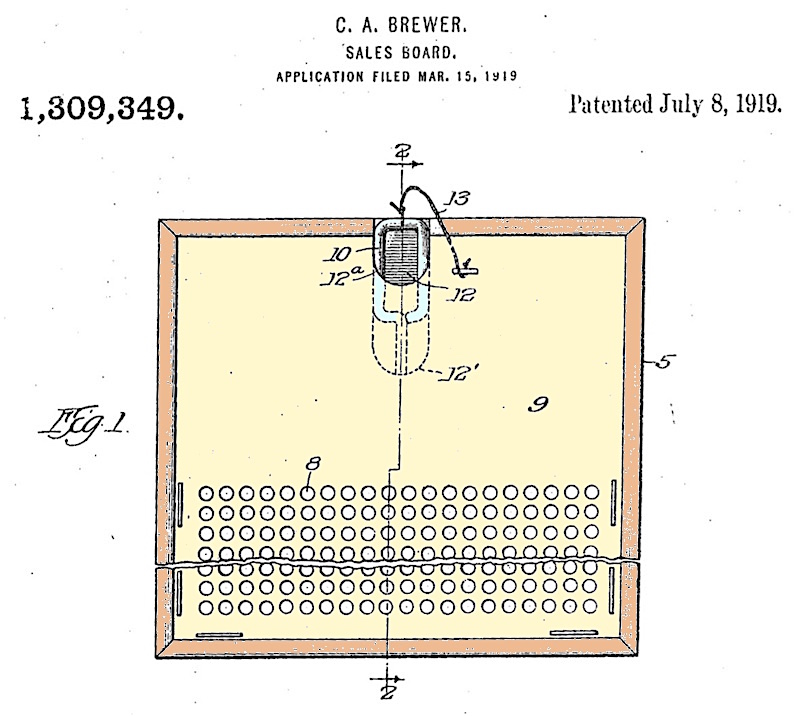

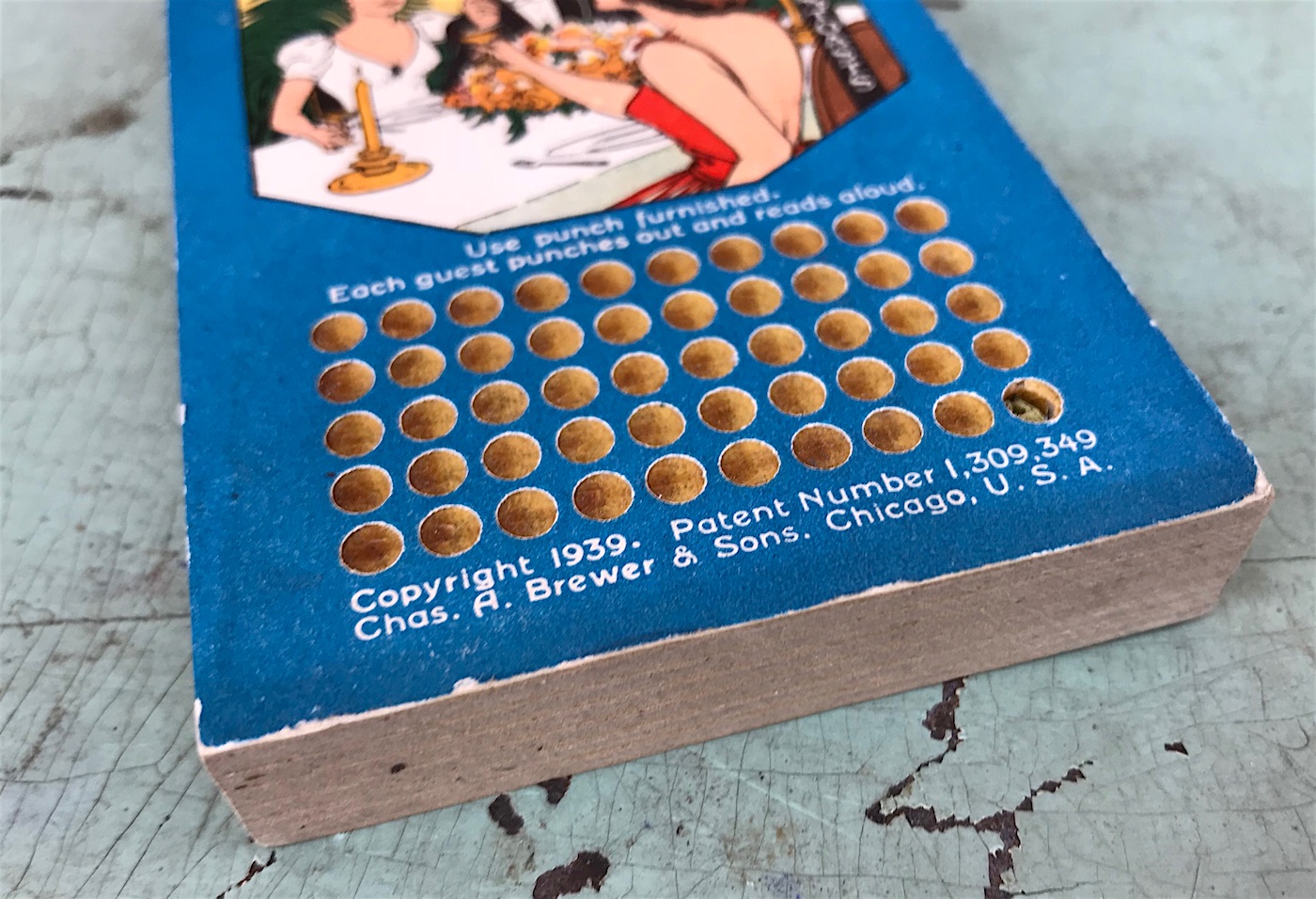

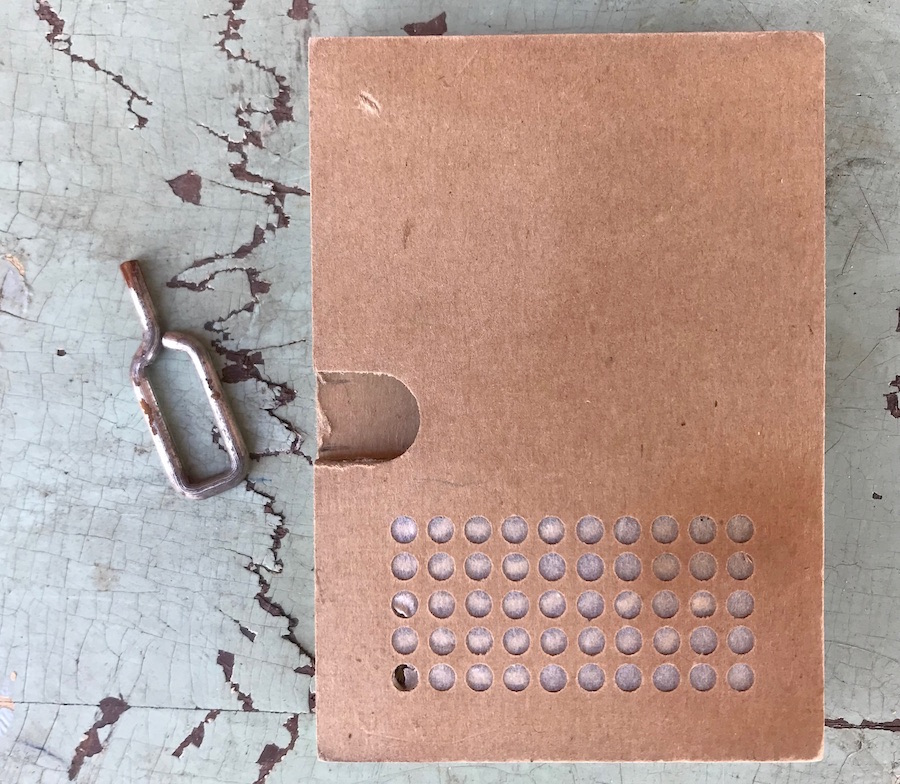

One of the common complaints with early sales-boards was that people consistently misplaced the tiny metal punch tool needed to pop out the paper slips. So, Brewer redesigned his games to include a tuck pocket for the punch key in the back of the board [patent No. 1,309,349], a feature conveniently included in our 1930s artifact.

One of the common complaints with early sales-boards was that people consistently misplaced the tiny metal punch tool needed to pop out the paper slips. So, Brewer redesigned his games to include a tuck pocket for the punch key in the back of the board [patent No. 1,309,349], a feature conveniently included in our 1930s artifact.

On the factory floor, Brewer also played an active role in developing new machinery to automate the preparation of the game boards. This included a “crimping and plaiting machine”—patented in 1920—designed for the precision task of stuffing tiny slips of rolled paper into the holes of each card. Since some individual punchboards had more than 1,000 holes, this sort of invention was perhaps even more critical to the budding industry than the creation of the original game idea itself.

“First in the Business—AND STILL FIRST,” read a 1921 ad. “Brewer Boards are filled by machinery and are safe from the inaccuracies of hand filling. Our prices are the lowest. Our quality the highest. — Chas. A. Brewer & Sons, Chicago, Ill. — The Largest Board and Card House in the World.”

Chuck Brewer may have felt he was perfecting his own creation, but he certainly wasn’t the only one tinkering with the possibilities of the punchboard by this point. Dozens of startup manufacturers started devising their own tweaked versions of the invention [Chicago companies like the Herbert Specialty Co., Harlich MFG Co., and James R. Irvin Co. were eventually among the competition], and out on the streets, game operators hatched some interesting “innovations” of their own.

Like any so-called game of chance, punchboards were designed to ensure that the operator, or “the house,” always won in the long run. Even so, many board operators couldn’t help but rig the system further in their own favor. Some merchants bought illegal “keyed” boards that allowed them to see the locations of prize slips in advance and potentially extract them before a customer could. A few even cleverer cats would take those same keyed boards, remove the cheat codes, sell them as legitimate boards to some other unknowing merchants, then send their buddies in to those stores later to systematically punch out the prizes. Candy from a baby.

As early as 1914, the Annual Report of the Citizens’ Association of Chicago was already recognizing the punch board biz as a corrupt and “evil” menace:

“Another form of gambling in the shape of so-called ‘punch boards’ had become extremely prevalent in various parts of the City and was being operated in hundreds of saloons, cigar stores, candy stores and other places. We pointed out that the operation of these ‘punch boards’ was a rank violation of the laws and ordinances relating to lotteries and gambling; and that the prevalence of large numbers of these illegal devices in any police district was a serious reflection upon the efficiency if not the integrity of the police officer in command of that district. After investigating a number of places which we had reported to him, Chief Gleason promptly suppressed these ‘punch boards’ throughout the City and has kept them suppressed.”

With the help of hindsight, we know that Chief Gleason did NOT, in fact, succeed in suppressing the rise of the punchboard, though he might have given it the old college try.

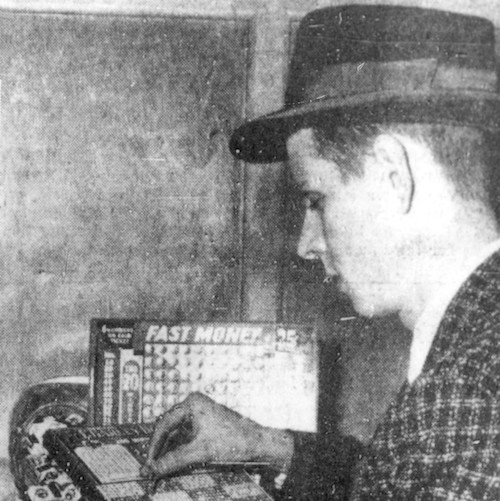

[Punchboard confiscations by the police, like the one above from the 1940s, were much harder to pull off in the device’s earlier days, when legal loopholes abounded.]

[Punchboard confiscations by the police, like the one above from the 1940s, were much harder to pull off in the device’s earlier days, when legal loopholes abounded.]

For many years, thanks to arrangements both crooked and common-sense, the punch board industry chugged right along with minimal attention—too new and ethically ambiguous to inspire severe legal penalties, and too damn enticing to scare off the public (luck, like science, seems predicated on regular testing).

To some observers of the time, people like Charles Brewer and his kids would have seemed like responsible employers and upstanding pillars of the community; to others, opportunistic two-bit schemers. As is generally the case with human beings, the reality is considerably more nuanced. Take, for example . . .

IV. The War Hero

Less than a year after the company transitioned from the Devon MFG Co. to Chas. A. Brewer & Sons, the youngest of those sons—plant superintendent Everett R. Brewer—enlisted in the Marines and joined the Allied cause in World War I as one of America’s first fighter pilots. This would not theoretically be in keeping with the cowardly disposition of a bamboozling bookie. But then again, if you’re a gambler, what’s a bigger roll of the dice than a dogfight?

All three Brewer boys were registered for the draft, and while it’s unclear if they all served (Kenneth asked for a deferment due to his responsibilities as factory manager), there is no doubt as to Everett’s exploits. The kid was kind of a legend.

All three Brewer boys were registered for the draft, and while it’s unclear if they all served (Kenneth asked for a deferment due to his responsibilities as factory manager), there is no doubt as to Everett’s exploits. The kid was kind of a legend.

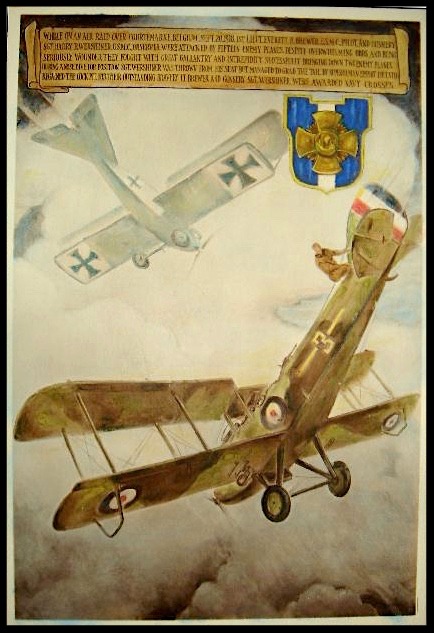

According to Marine Corps records later immortalized on an officially commissioned mural of the event (!), “While on an air raid over Courtemarke, Belgium, Sept. 28, 1918, 1st Lieut. Everett R. Brewer, U.S.M.C., pilot, and Gunner Sgt. Harry R. Wershiner, U.S.M.C., observer, were attacked by fifteen enemy planes. Despite overwhelming odds and being seriously wounded, they fought with great gallantry and intrepidity, successfully bringing down two enemy planes. During a nose dive for position, Sgt. Wershiner was thrown from his seat but managed to grab the tail. By superhuman effort he later regained the cockpit. For their outstanding bravery, Lt. Brewer and Gunnery Sgt. Wershiner were awarded Navy Crosses.”

[A mural commissioned by the U.S. Marine Corps, capturing a moment from Everett Brewer’s historic dogfight in World War I. Note his gunner Harry Wershiner literally hanging off the tail of the plane!]

[A mural commissioned by the U.S. Marine Corps, capturing a moment from Everett Brewer’s historic dogfight in World War I. Note his gunner Harry Wershiner literally hanging off the tail of the plane!]

Nearly 30 years later, Everett Brewer would be awarded the Purple Heart in recognition of the same event, and roughly a century later, he is still credited with the first kill by a Marine aviator in combat. Whatever glory came with that achievement, however, wasn’t particularly tangible or relevant in the immediate aftermath.

In November of 1918, more than six weeks after the air raid in question, Everett was still in recovery in a Dunkirk hospital from wounds to his hip and leg. Meanwhile, a world away in the Beverly neighborhood of Chicago, in a house at 9300 S. Pleasant Avenue, his father Charles and mother Kittie still didn’t know what had become of their son. Word traveled like molasses internationally.

In November of 1918, more than six weeks after the air raid in question, Everett was still in recovery in a Dunkirk hospital from wounds to his hip and leg. Meanwhile, a world away in the Beverly neighborhood of Chicago, in a house at 9300 S. Pleasant Avenue, his father Charles and mother Kittie still didn’t know what had become of their son. Word traveled like molasses internationally.

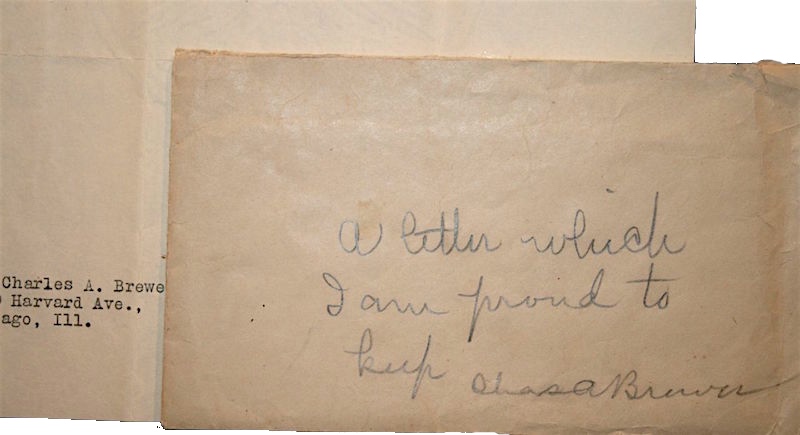

Finally, on November 14, a letter from a Marine Brigadier General reached Charles Brewer in his office at the Harvard plant, informing him of Everett’s recovery status and his courage under fire. One can imagine Charles running through the factory, sharing the letter with Everett’s work pals and celebrating that the kid was both alive and a hero.

That letter from the general, incidentally, was put in special keeping, and remained part of a collection of Everett Brewer’s war service records and commendations, preserved into the present day by his surviving family. If you look carefully, you can see a note written on the back of that original envelope, likely scribbled down by Everett’s relieved father 100 years ago: “A letter which I am proud to keep— Chas. A. Brewer.”

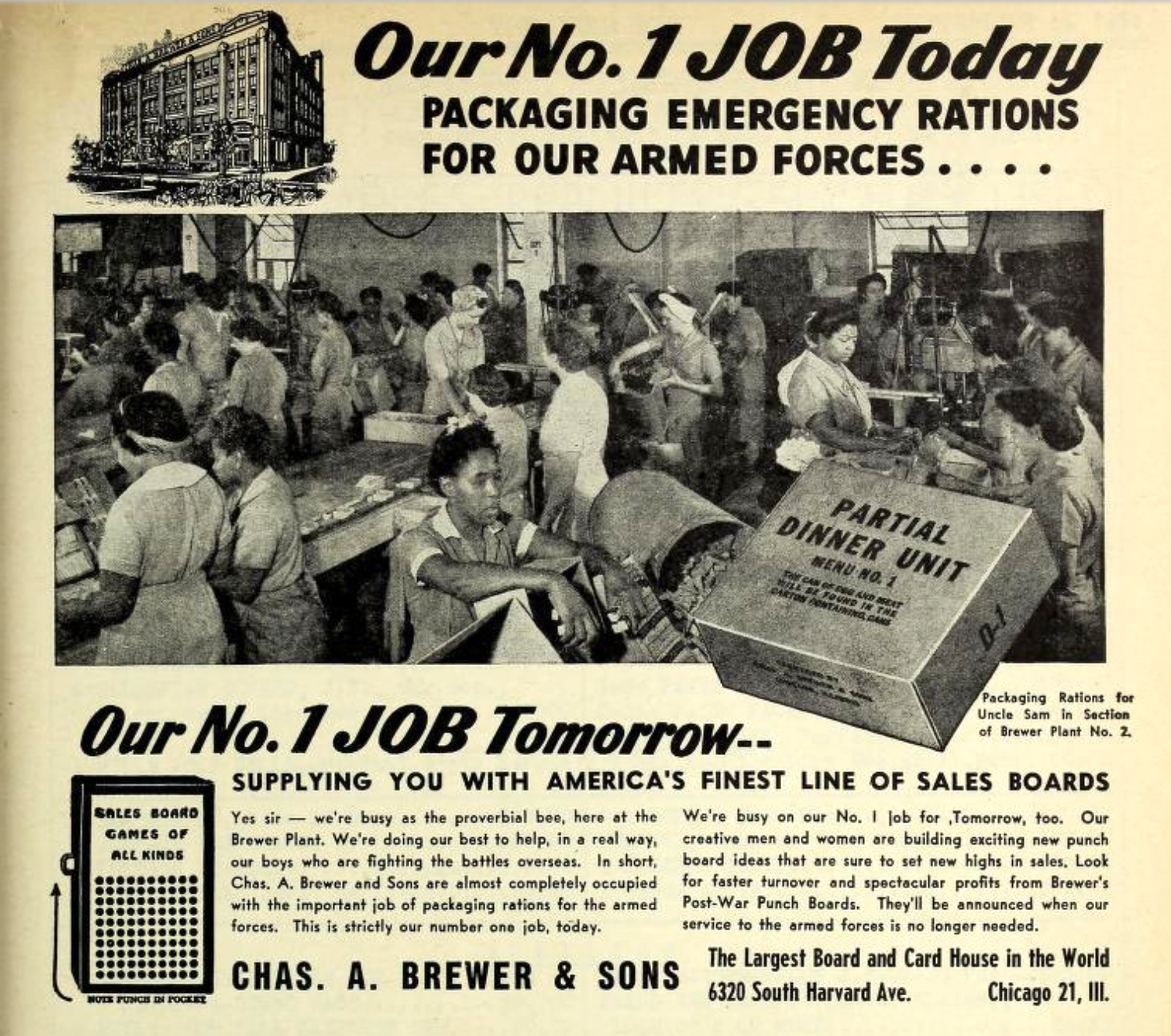

When the U.S. entered World War II, a now 51 year-old Everett Brewer was a chairman of the family business, having succeeded his late father. And, like before, he seemed to have his priorities in order—halting punchboard manufacturing at the factory to focus on packing emergency field rations for the troops. He also volunteered his own skills to help the Air Technical Service Command with its “central district price adjustment board,” earning him yet another medal from the War Department for “meritorious civilian service.”

If that were the entirety of the story, we could probably rest easy assessing the Brewer clan as true, reputable patriots of the highest order. But, of course, as warned, there is nuance.

It’s unclear, for example, if the War Department was aware that their honoree Everett Brewer was simultaneously under investigation by the U.S. Government for unfair trade practices (i.e., the gambling stuff) and labor violations.

[1944 advertisement promoting Brewer & Sons’ emergency rations for the war effort. The company’s workforce was largely women and racially diverse.]

[1944 advertisement promoting Brewer & Sons’ emergency rations for the war effort. The company’s workforce was largely women and racially diverse.]

Apparently, when the Harvard factory switched to making military rations (“Our No. 1 Job,” as noted in the ad above), the company actually kept some of its punchboard production going off-site, hiring women to work from home at substandard wages, doing the delicate task of placing paper slips into boards. In 1942, Chas. A. Brewer & Sons was eventually charged and found guilty of violating the minimum wage provisions of the Fair Labor Standards Act, with a federal judge ordering the company to pay over $6,000 in back wages to 68 women.

The vast majority of the company’s on-site employees at the Harvard plant were women, as well, including a substantial contingent of African-American laborers. This wasn’t merely a consequence of watching the men go off to war. For the precision tasks of preparing and packing punch boards, women could do the work for half the expected wages of men, so the hiring practices were all about economics.

Sometimes war heroes, geniuses, and patriots also dabble in gambling rings and worker exploitation. It’s as American as apple pie and pin-up girls.

V. The Coin Economy

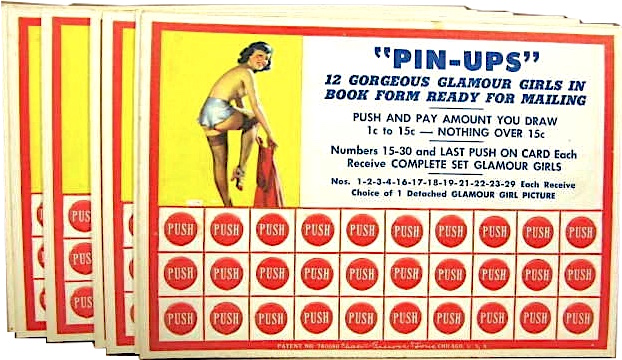

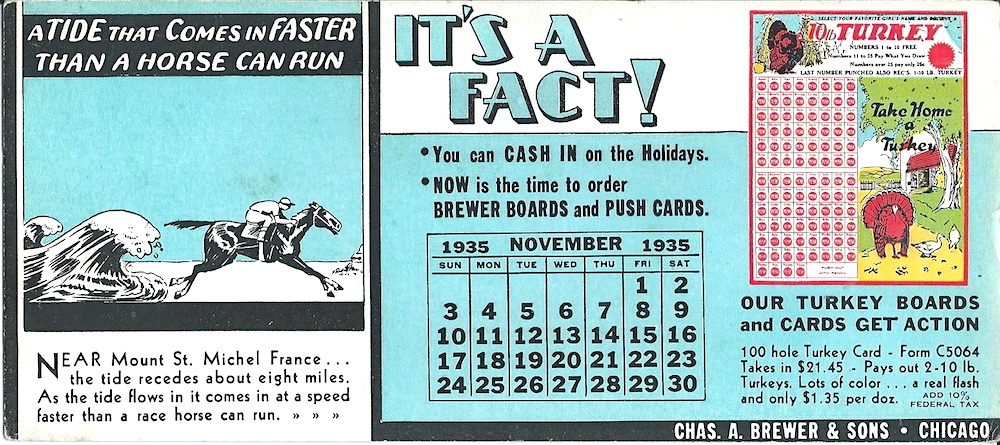

In the years between the wars, scrutiny of the punchboard industry had clearly intensified, leading to an uptick in arrests, lawsuits, and calls for reforms. The boards’ designs began to match that seedy reputation, as well, with scantily clad pin-up girls beckoning would-be customers to spend a nickel on an unlikely shot at free candy, cigarettes, or booze.

During the Prohibition ’20s, lawmakers had bigger fish to fry than small-time lottery games, but by the 1930s—as the trade stimulator market grew in direct inverse to the rest of the American economy—it became clearer that “harmless” punchboards could actually be used to take advantage of an increasingly desperate and vulnerable American populous.

[A set of Glamour Girl “Pin Ups” push cards produced by Chas. A. Brewer & Sons]

[A set of Glamour Girl “Pin Ups” push cards produced by Chas. A. Brewer & Sons]

According to Sam Lubell’s 1939 story in the Saturday Evening Post, people were spending “somewhere between one half and three quarters of a billion dollars” on punchboards and coin machines. “Between ten and fifteen billion nickels . . . as much money as Congress ever has appropriated for any peace time Army or Navy. The amount equals the total sales in nation’s shoe stores, and doubles the business done in the country’s jewelry shops. . . . Ordinary access to bank credit does not exist. Yet today the industry’s capital investment is variously estimated at between $20 million and $50 million [$360 million to $900 million after inflation].”

Lubell traveled to Chicago in the spring of ’39 to interview key players in the trade stimulator biz, presumably looking to shine a light on an epidemic of normalized gambling that was hiding in plain sight. His article, however, wound up sitting surprising well with the big shots in the industry, who saw it as an affirmation of the gaming industry’s ability to successfully promote goods (the Zippo company famously sold hundreds of thousands of lighters through punchboard ads), deliver a new cashflow to struggling merchants, AND bring vital jobs to workers still coming out of the Depression.

“Easily 1,000,000 persons, and perhaps twice that number,” Lubell guessed, “get all or part of their income from the business. Some of the million supply manufacturers with raw materials. Others run one or two of the devices in a little store or hamburger stand.

“. . . The men who head the industry do not regard themselves as villains. They argue that their business is as honorable as many other businesses sanctioned by law and society. Their devices do no more harm, they argue, than liquor.”

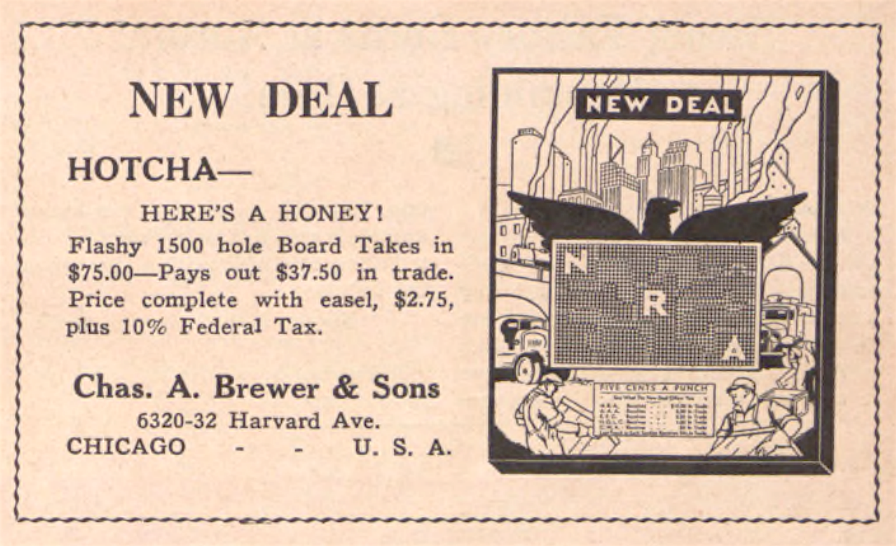

No more harm than liquor seems like a shaky defense, but the comparison makes sense coming right out of Prohibition. Punchboard makers also followed the marketing strategy of many liquor companies, fending off criticism by aligning themselves with incontestable patriotic ideals. The “New Deal” punchboard that Brewer & Sons produced in 1933 is a blatant example, featuring the N.R.A. lettering of the National Recovery Administration and other random images of proud workers, factory smoke, etc. How could a game celebrating the American working man also be designed to exploit him?

No more harm than liquor seems like a shaky defense, but the comparison makes sense coming right out of Prohibition. Punchboard makers also followed the marketing strategy of many liquor companies, fending off criticism by aligning themselves with incontestable patriotic ideals. The “New Deal” punchboard that Brewer & Sons produced in 1933 is a blatant example, featuring the N.R.A. lettering of the National Recovery Administration and other random images of proud workers, factory smoke, etc. How could a game celebrating the American working man also be designed to exploit him?

Many companies also dodged the feds by coming up with new ways to diversify their product lines and soften their image. This could include releasing special seasonal or holiday themed games—like the popular “Turkey Boards” at Thanksgiving—or selling boards supposedly intended “for amusement only,” with no clear gambling element involved.

VI. A Peppy Thrill

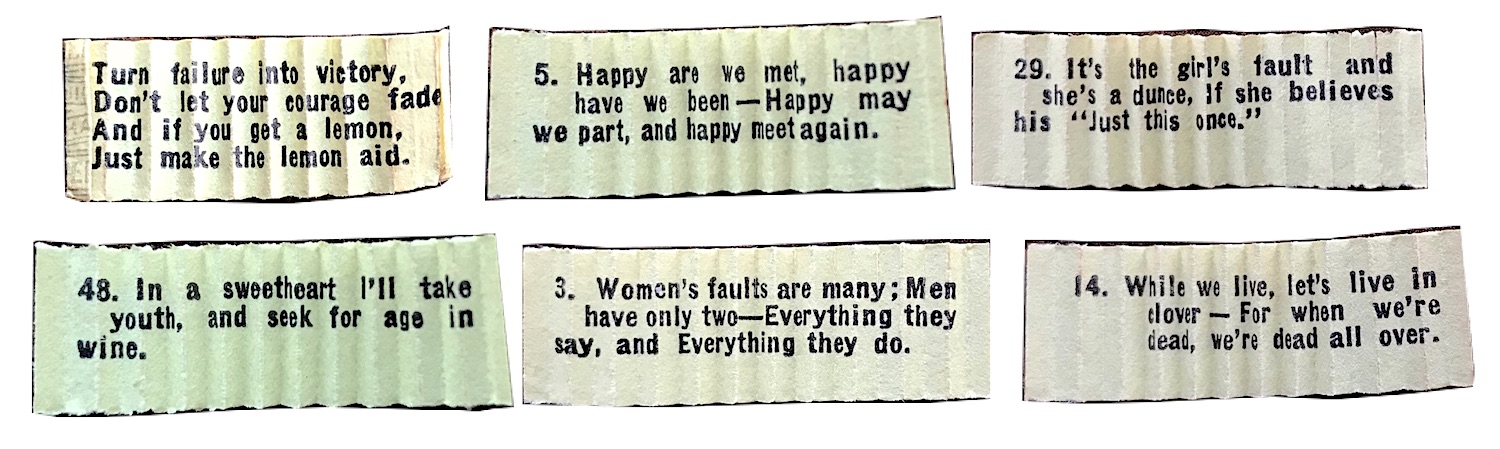

The “Peppy Thrill” icebreaker game in our museum collection is an example of one of Brewer & Sons’ lighter forms of punchable entertainment. Sub-titled “The Party Game,” its paper slips all feature cheeky little jokes or phrases that party-goers would presumably select at random and read aloud for shits and giggles—like Cards Against Humanity for the Greatest Generation.

Sometimes the tiny print on the accordion-rolled paper would reveal the equivalent of a fortune cookie quote: “Turn your failure into victory / Don’t let your courage fade / And if you get a lemon / Just make the lemon aid.”

Sometimes the tiny print on the accordion-rolled paper would reveal the equivalent of a fortune cookie quote: “Turn your failure into victory / Don’t let your courage fade / And if you get a lemon / Just make the lemon aid.”

Other times it’d be a challenge to perform some sort of silly task: “Tie your shoelaces together and strut like a peacock.”

Of the half-dozen papers I punched from the Peppy Thrill board, though, most amounted to comedy one-liners about how fellas are rotten and dames ain’t too smart:

“It’s the girl’s fault and she’s a dunce, if she believes his ‘Just this once.'”

“Women’s faults are many; Men have only two—Everything they say, and Everything they do.”

Tee hee!

Tellingly, though, even the Peppy Thrill paper slips are still numbered in the top left corner just like the gambling boards, suggesting that players could still lottery-ize the game at any time and in any way they wanted.

[Paper slips punched directly from our 1939 Peppy Thrill game, unread for about 80 years]

[Paper slips punched directly from our 1939 Peppy Thrill game, unread for about 80 years]

Clearly, no amount of suggestive jokes could ever top the “peppy thrill” of mankind’s favorite ill-advised pastime: gambling. And long odds, it seemed, only increased the enticement.

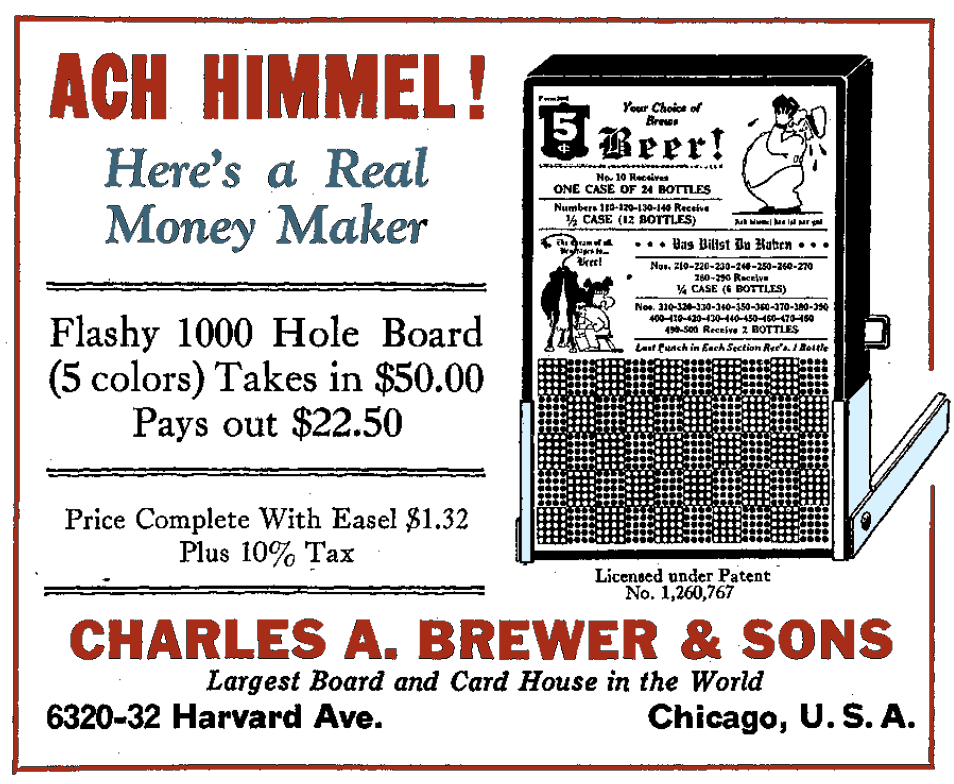

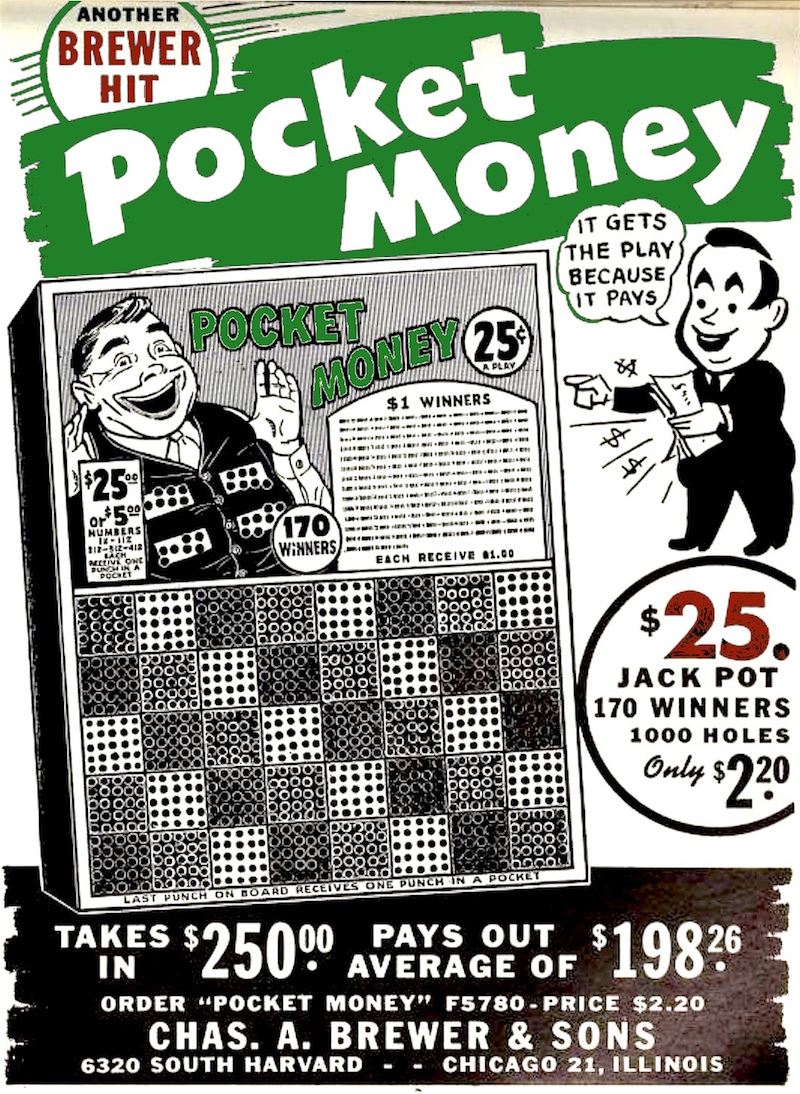

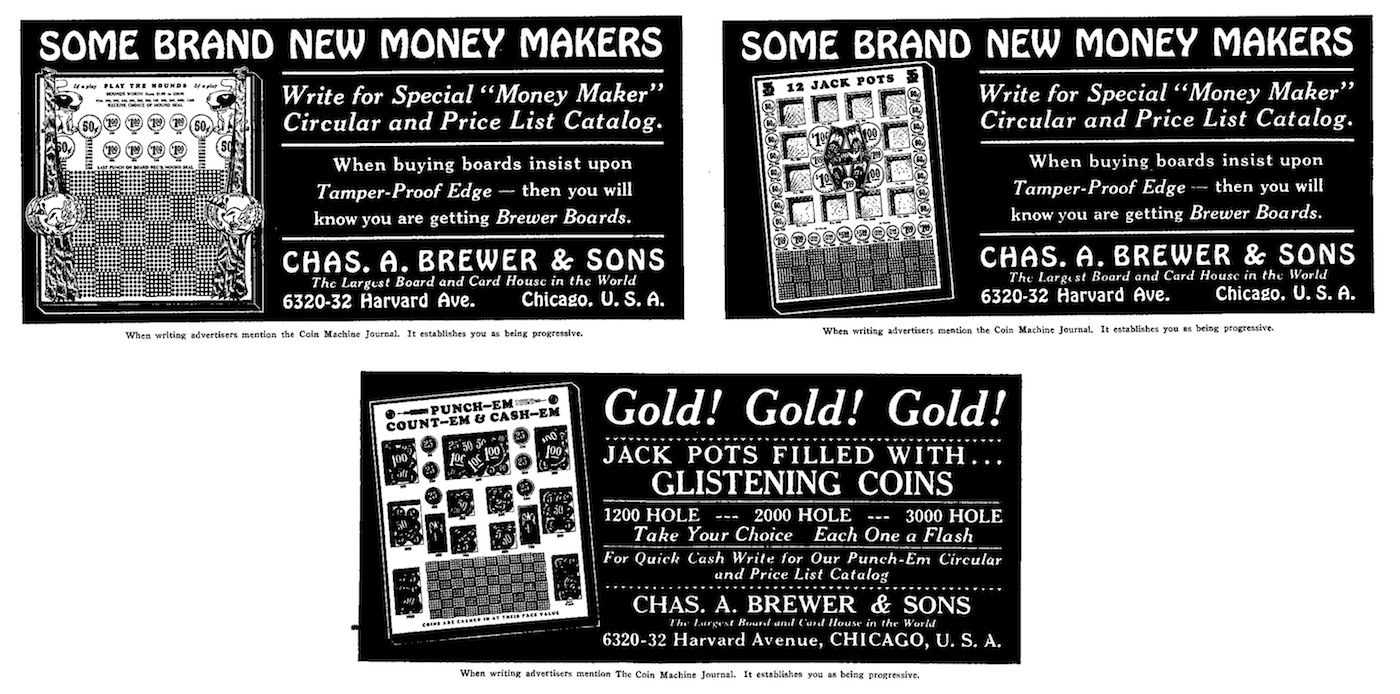

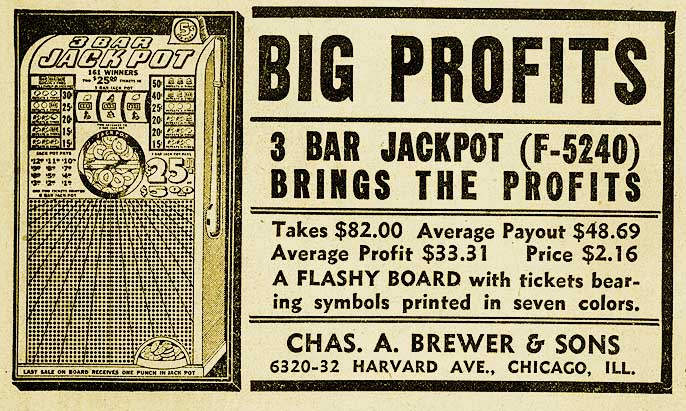

It’s hard to say that Brewer & Sons or any other major punchboard maker were ever truly hoodwinking the public. Even in its advertisements for games like the aforementioned New Deal punchboard, Brewer spelled out the economics right there in black and white, announcing to merchants that this device was a guaranteed winner for the store owner and a loser for the vast majority of his customers.

“Hotcha—Here’s a Honey! Flashy 1500 hole Board takes in $75.00—Pays out $37.50 in trade. Price complete with easel, $2.75, plus 10% Federal Tax.”

Other Brewer Boards from the 1930s advertise similar ratios: “Takes in $50.00, Pays out $22.50.” “Takes in $40.00, Pays out $19.00.” “Takes in $100.00, Pays out $40.00.”

By the early 1940s, Brewer catalogs and sales flyers were unabashedly describing their business model in dangerously direct language.

“Board Sales Bring Other Sales: Compare two stores, one using Brewer Boards and one not using them. Other factors being equal, the one with Brewer Boards invariably has the largest group of regular customers. There is a certain thrill to punching boards and the public will favor the store using them. Records show that the average customer who spends 25c to 50c will spend twice this amount when the storekeeper uses Brewer Boards. And in addition to this, the customer usually makes other purchases while in the store. Are You Getting Your Share?”

The words above—highlighting the benefits of unfair competition— basically doubled as a confession in the eyes of the Federal Trade Commission, which seemed to be galvanized by a wartime fervor of righteousness.

The words above—highlighting the benefits of unfair competition— basically doubled as a confession in the eyes of the Federal Trade Commission, which seemed to be galvanized by a wartime fervor of righteousness.

Brewer & Sons had fended off mounting legal challenges for years, but in 1942 (the same year as the company’s Labor Standards violation), the FTC buried them with a cease-and-desist order. At the time, Brewer was still the largest player in the game, producing 5,000 different types of punch boards and 3,000 styles of push cards. Nonetheless, their efforts to challenge this FTC ruling over the next few years fell on deaf ears, ending with the U.S. Court of Appeals in 1946.

The final ruling asserted that Brewer & Sons “supply and place in the hands of retail dealers, either directly or indirectly, the means of conducting lotteries or games of chance in the sale of merchandise to the general public: a practice which is in contravention of an established public policy of the Government of the United States; and that, through the supplying of such means petitioners knowingly and purposely assist and participate in the violation of this public policy.”

“The acts and practices of [Brewer & Sons] as herein found,” the FTC claimed, “are all to the prejudice of the public and constitute unfair acts and practices in commerce within the intent and meaning of the Federal Trade Commission Act.”

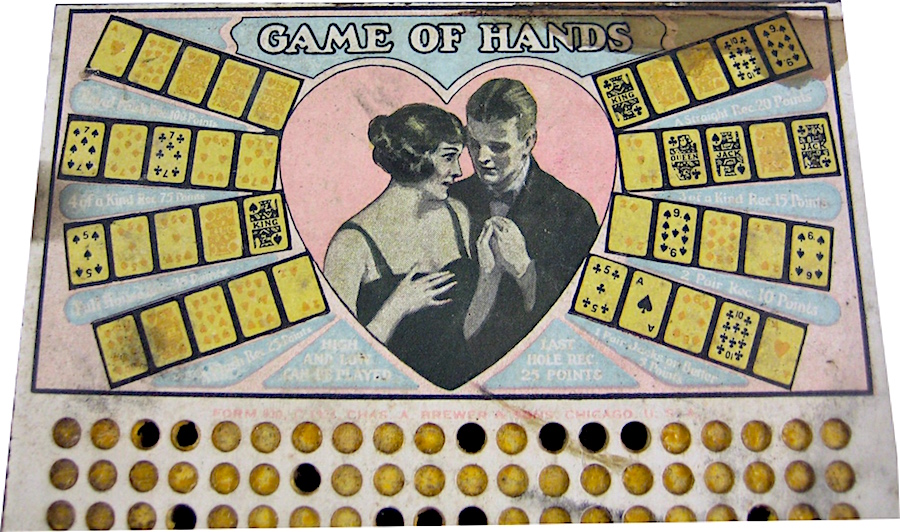

[The eye-catching artwork on Brewer Boards like the Peppy Thrill and the “Game of Hands” above seems to match the style of African-American artist Charles Dawson, who lived on the South Side and did quite a bit of commercial art in the 1930s, most famously for the Valmour Products Company.]

[The eye-catching artwork on Brewer Boards like the Peppy Thrill and the “Game of Hands” above seems to match the style of African-American artist Charles Dawson, who lived on the South Side and did quite a bit of commercial art in the 1930s, most famously for the Valmour Products Company.]

VII. Last Punches

And that was that. Roughly 40 years after Charles Brewer patented his handy new breed of “vending device,” the party was officially coming to an end.

Charles himself wasn’t around to see it. He had died in 1933, and son Kenneth had followed 10 years later. This left the responsibility to Nelson and Everett Brewer to determine a next course of action in the wake of their run-in with the FTC.

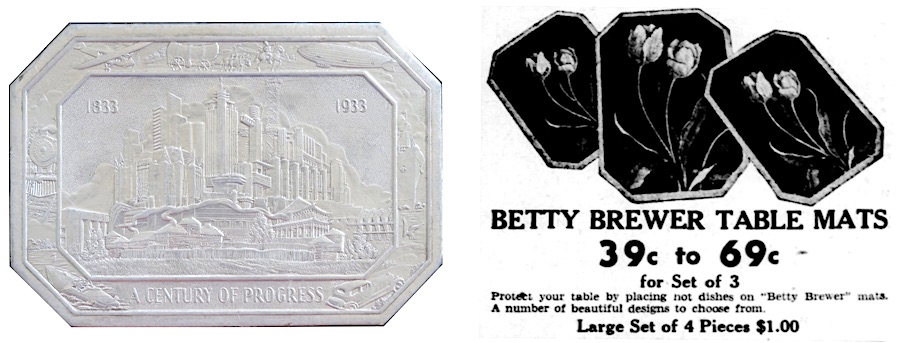

One fairly successful and ethical side venture was the company’s “Betty Brewer” line of heat-resistant table mats, which debuted in 1945. Decorative hot pads, or trivets, had actually been produced at the Brewer plant dating back to the ’30s, including commemorative mats for the Chicago and New York World’s Fairs of 1933 and 1939. But these newer models were named for Everett’s wife Elizabeth, and were geared more toward the post-war housewife, for everyday use.

[Left: A “Century of Progress” hot pad produced by Brewer in 1933. Right: A 1949 ad for “Betty Brewer Table Mats,” a brand likely named for Everett Brewer’s wife Elizabeth Brewer]

Of course, the table mat solution wasn’t going to be the saving grace for the entire punchboard industry, and many of Brewer’s old competitors hadn’t given up the fight just yet; still dodging the government’s hammer. For these businesses, the well-equipped Brewer factory on Harvard Avenue suddenly became a property of considerable interest. One such suitor was the Universal Manufacturing Company of Kansas City, owned by Joseph Berkowitz.

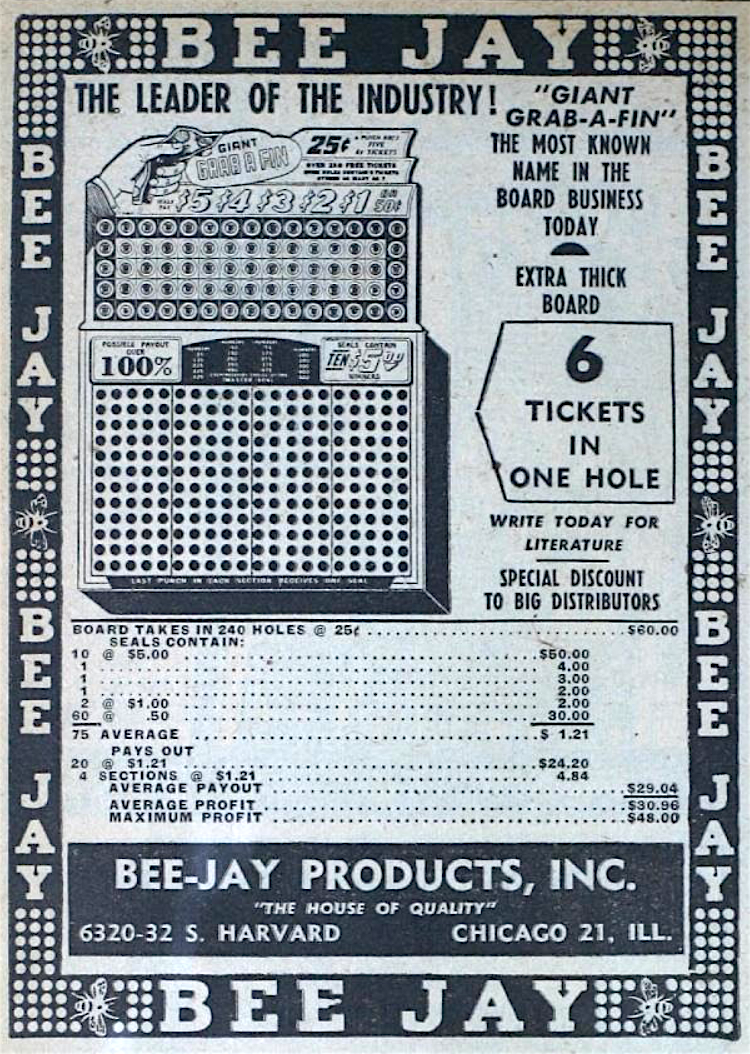

In 1946, Berkowitz worked out a deal to purchase the in-limbo Brewer & Sons business for a song, keeping the plant on Harvard Avenue and renaming it the Bee-Jay Products Company, Inc. Through some sort of legal tap dance, Bee-Jay continued to make and sell punchboards at the factory until 1952, when yet another FTC cease-and-desist order forced them to condense the business into other less regulated gambling paraphernalia like “fish bowl games” and “tip books.”

In 1946, Berkowitz worked out a deal to purchase the in-limbo Brewer & Sons business for a song, keeping the plant on Harvard Avenue and renaming it the Bee-Jay Products Company, Inc. Through some sort of legal tap dance, Bee-Jay continued to make and sell punchboards at the factory until 1952, when yet another FTC cease-and-desist order forced them to condense the business into other less regulated gambling paraphernalia like “fish bowl games” and “tip books.”

As late as 1961, Bee Jay Products was still in business (with a Chicago office at 2855 N. Halsted Street) and still battling the government. That year, the company grabbed headlines for filing a ballsy lawsuit against none other than U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, claiming that new laws against the interstate sale of wagering games were unconstitutional. They were merely delaying the inevitable.

Just a few years later, the first state controlled lotteries were introduced, and by the 1970s, scratch cards became the new craze. The government may have frowned on ethically unsound and exploitative trade stimulators in the past, but in the long run, they only ended up monopolizing the old business model for their own benefit.

Nelson Brewer died in 1967, and Everett followed in 1982. The former Brewer & Sons factory at 6320 S. Harvard Avenue was torn down in 2007.

Sources:

“Ten Billion Nickels” – Saturday Evening Post, May 13, 1939

“The General Significance of Post article ‘Ten Billion Nickels'” – Automatic Age, June, 1939

“Chas. A. Brewer & Sons v. Federal Trade Commission,” 158 F.2d 74 (6th Cir. 1946)

“Interstate Sale Stopped” – The Gazette and Daily (York, PA), Oct 23, 1952

“Vending Device” – U.S. Patent 780,086, Charles A. Brewer and Clinton G. Scannell

“Reformed Gambling Swindle Becomes a Punch Board of Love” – Collectors Weekly, 2012

“Turkey Board Season Opens November 1st” – Coin Machine Journal, October 1933

Annual Report of the Citizens’ Association of Chicago, 1914

“Punchboards” – Clark Phelps Antiques

“Berkowitz Buys Salesboard Company” – The Billboard, March 2, 1946

“Suit Attacks U.S. Curb on Raffle Books” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 16, 1961

“Flyer of 1918 Given Award” – Baltimore Sun, Nov 9, 1947

“Everett R. Brewer Marine Corps Aviation Grouping” – WarRelics Forum

“Brewer v. Woodham” – The Southern Reporter, Vol. 74, 1917

It seems that Brewer & Sons also produced beer coasters (at least during the 30’s) for breweries local to the area. I’m lucky to posses at least one such item, issued for the Acme Brewing Co., Joliet, ILL. which advertises details of the brewery and it’s beer on the front but the reverse is plain other than a feint impression made….’Made By Brewers & Sons Chicago’. Although I live in the UK, I do collect US beer coasters from this period and would be interested to hear from anyone who just may have any to spare.

I have in my possession a Charles A. Brewer and Sons hot dish mat. It is of the Grand Canyon, with smaller embossed pics of the “Watch Tower “ and “Rainbow Bridge” . copyright 1938. It had been my grandmothers and somehow has survived many moves and has now landed in my possession. I know that no one in my family is going to want it when I pass on. Would it be anything you would be interested in adding to your collection? I live in Montana and my phone # is 406-531-9027 if you care to discuss, or email me.

Best regards,

Jan Rach

I came across this article while looking for information on foil Hot Pads . An item for sale on Etsy had one listed as “1933 Chicago World’s Fair Century Of Progress Souvenir Aluminum Hot Pad Pot Holder – Sealed. The image had a label that read, “Century Of Progress Table Mats,” Design by C. A. Brewer & Sons, Chicago. I found your article very interesting, but no mention of products other than punch boards. Could the foil mats have been a prize item for the punch board games? How were they involved in the World’s Fair?

Thank you for your reply.

Regards

Hi Ann, I added a bit about Brewer’s table mats to the article. I imagine the World’s Fair models were sold at the event itself as commemorative items, but they could probably be purchased elsewhere, as well. I can’t say for certain. The company later produced the “Betty Brewer” brand of mats in the ’40s.

I have a Yellowstone Park scrapbook/ album about 7 x 11.5, embossed with a silver front depicting 5 features of the park. “Yellowstone Park” on the top, and “Old Faithful” on the bottom. In the back inner cover, it states “Made in the USA, designed by C A Brewer and Sons, Chicago USA.

I cannot locate any information but have a feeling it is somehow related to the Worlds Fair. Many thanks for any help.