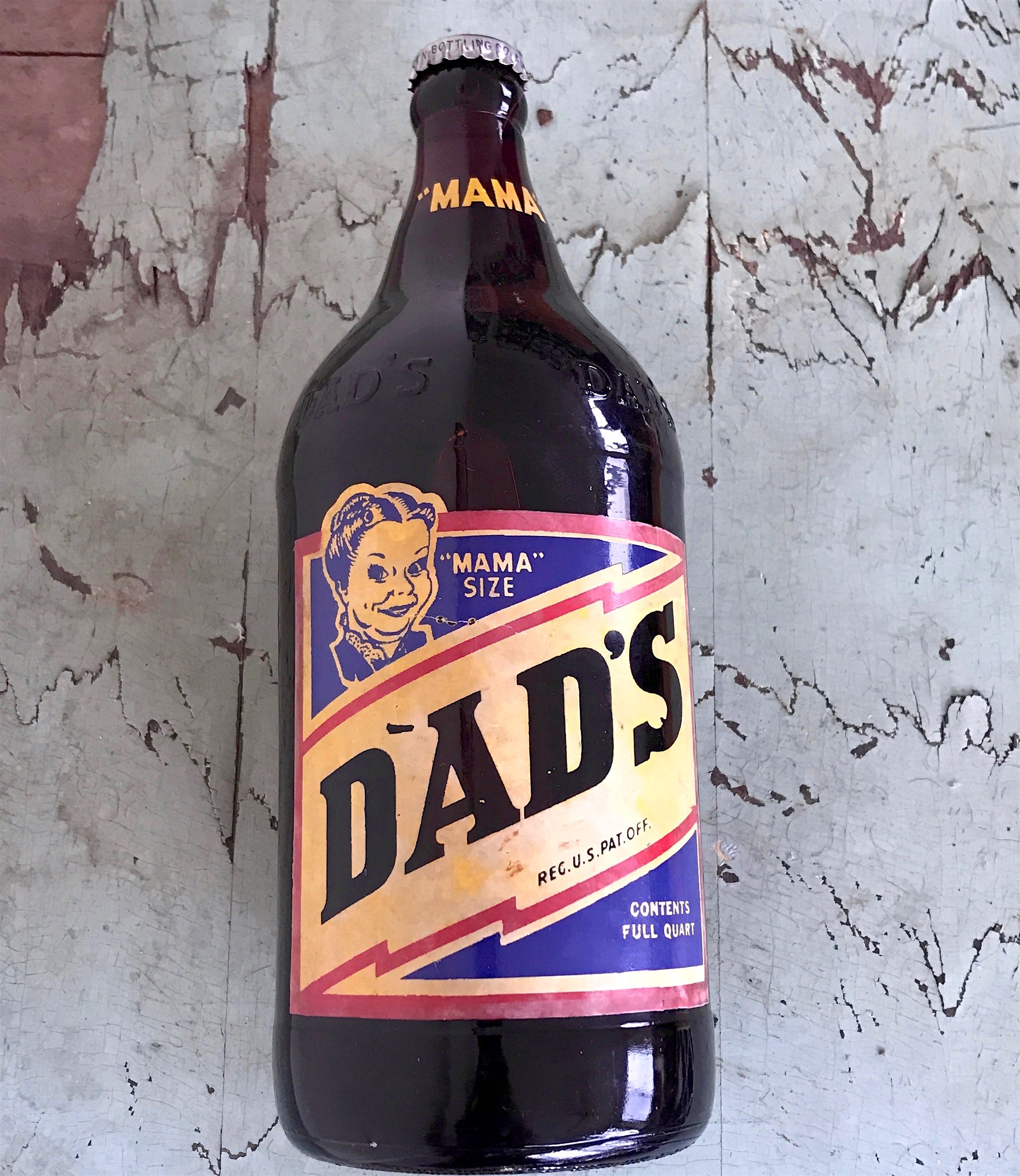

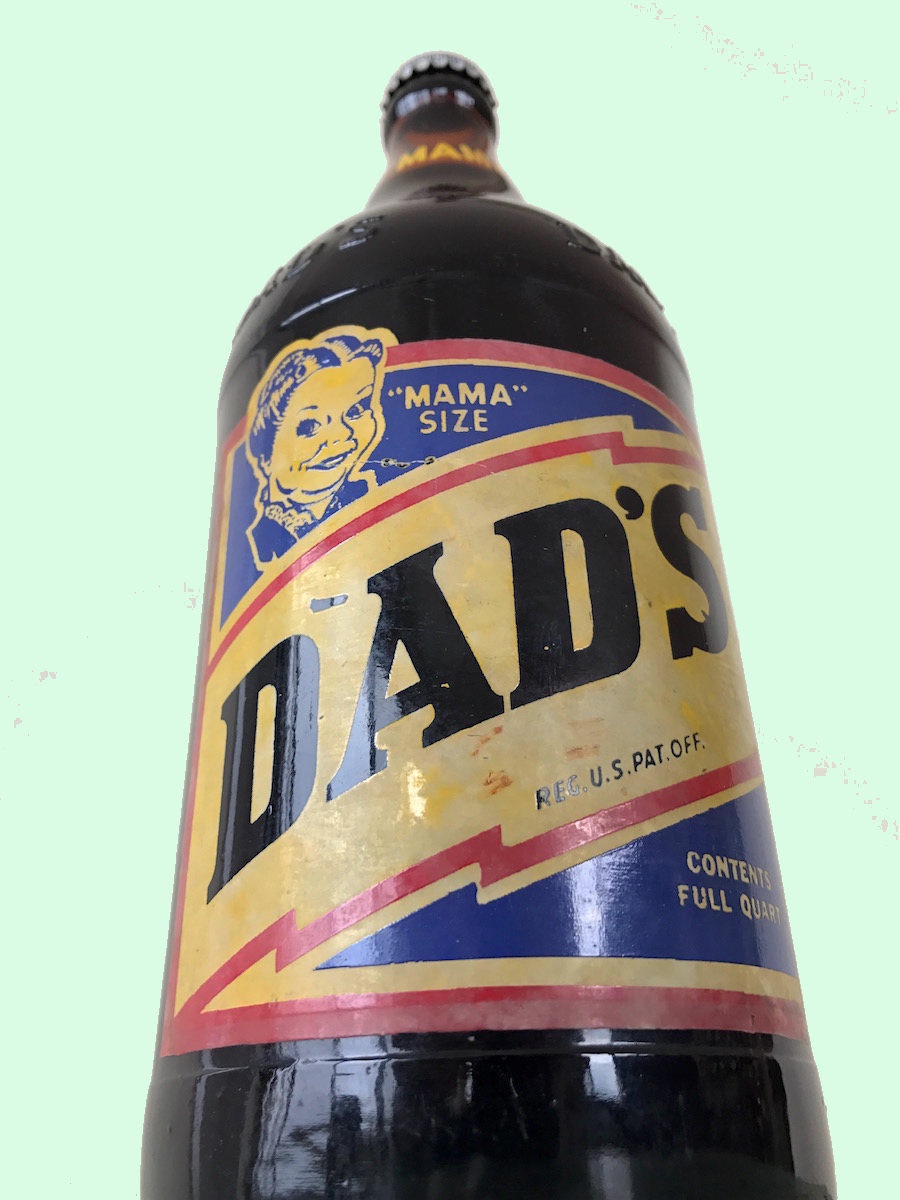

Museum Artifact: Unopened Dad’s Root Beer “Mama” Bottle, 1960s

Made By: Dad’s Root Beer Co., 2800 N. Talman Avenue, Chicago, IL [Avondale / Logan Square]

“It’s a completely new idea! Genuine draft root beer in bottles!”

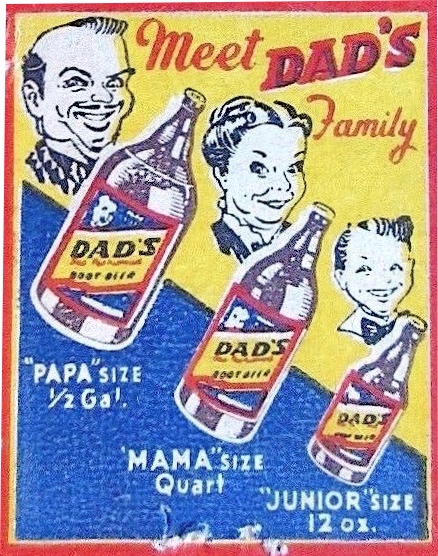

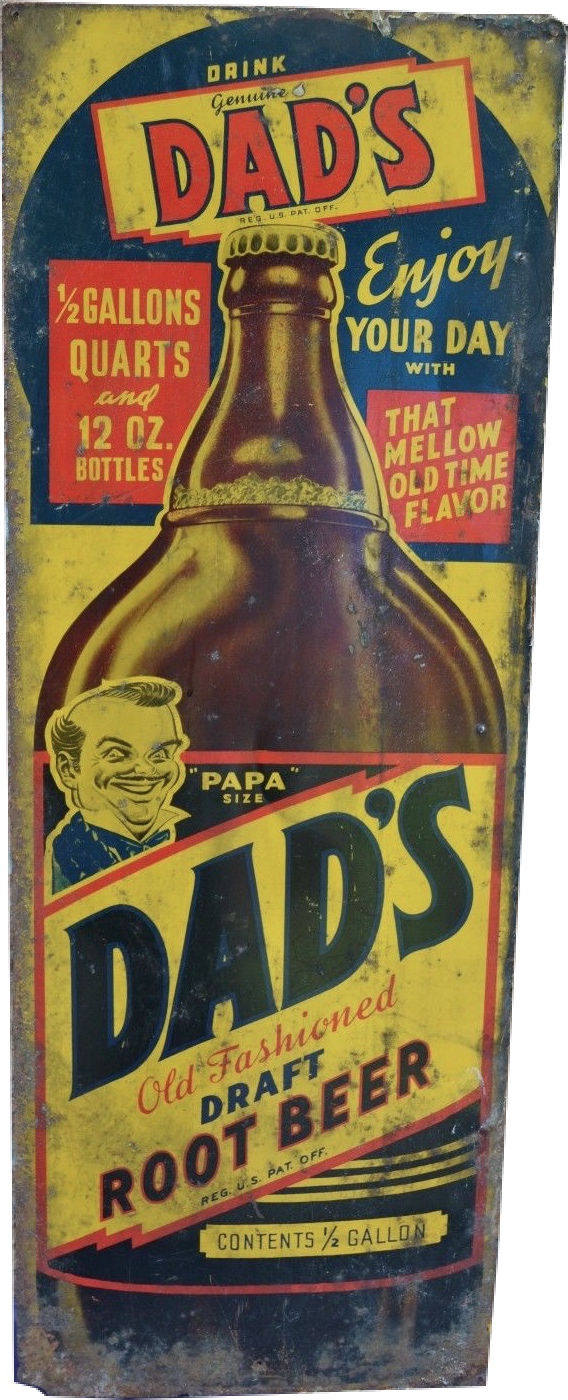

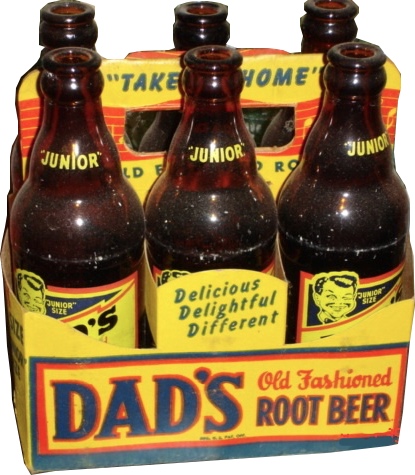

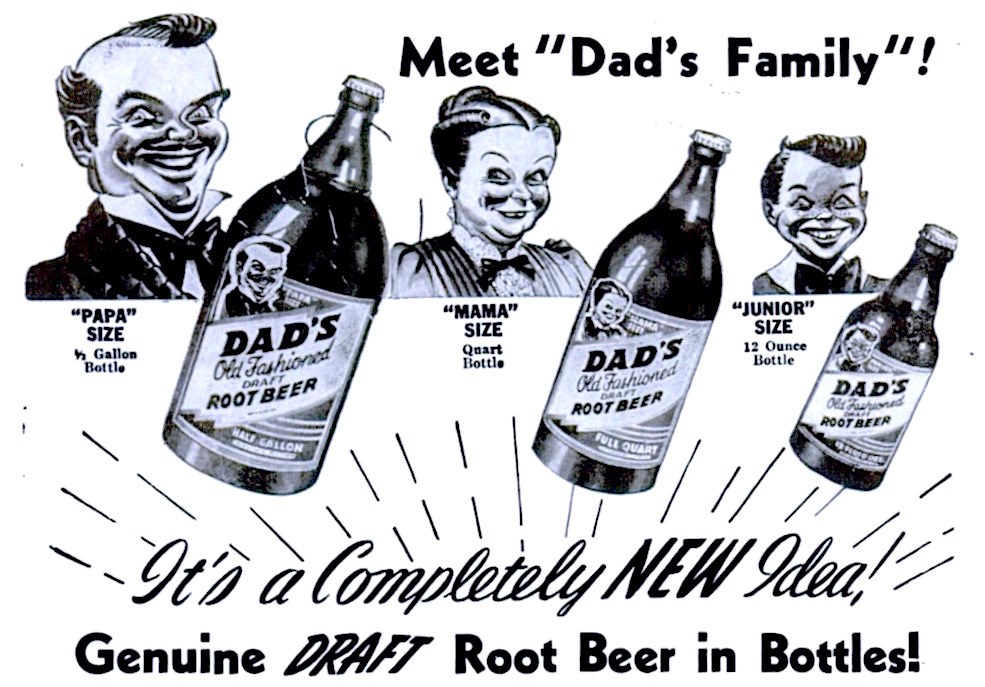

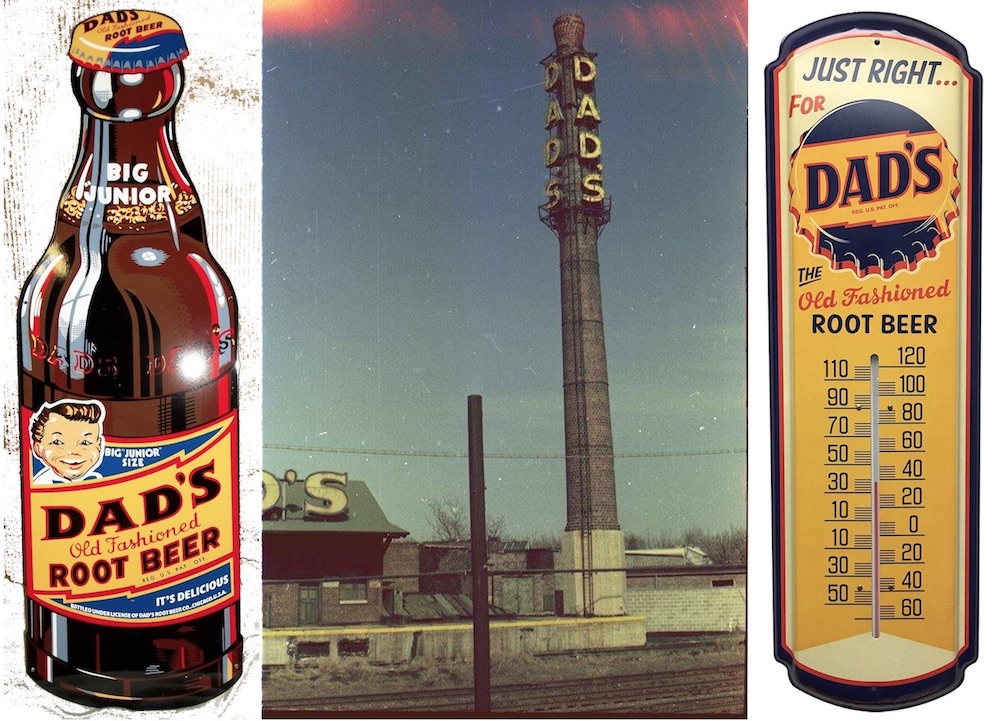

When Dad’s Root Beer creators Ely Klapman and Barney Berns rolled out their first big national ad campaign in 1941, they did so with an immediate contradiction in terms—a “completely new” thing was also promoted as the “old fashioned” root beer. Americans were bewildered but intrigued (and thirsty), and so, in the midst of a blissfully ignorant pre-war euphoria, they happily went out and sampled the whole “Dad’s Family” of breakable brown bottles— the 12 ounce “Junior,” the quart sized “Mama,” and the enormous half-gallon “Papa.”

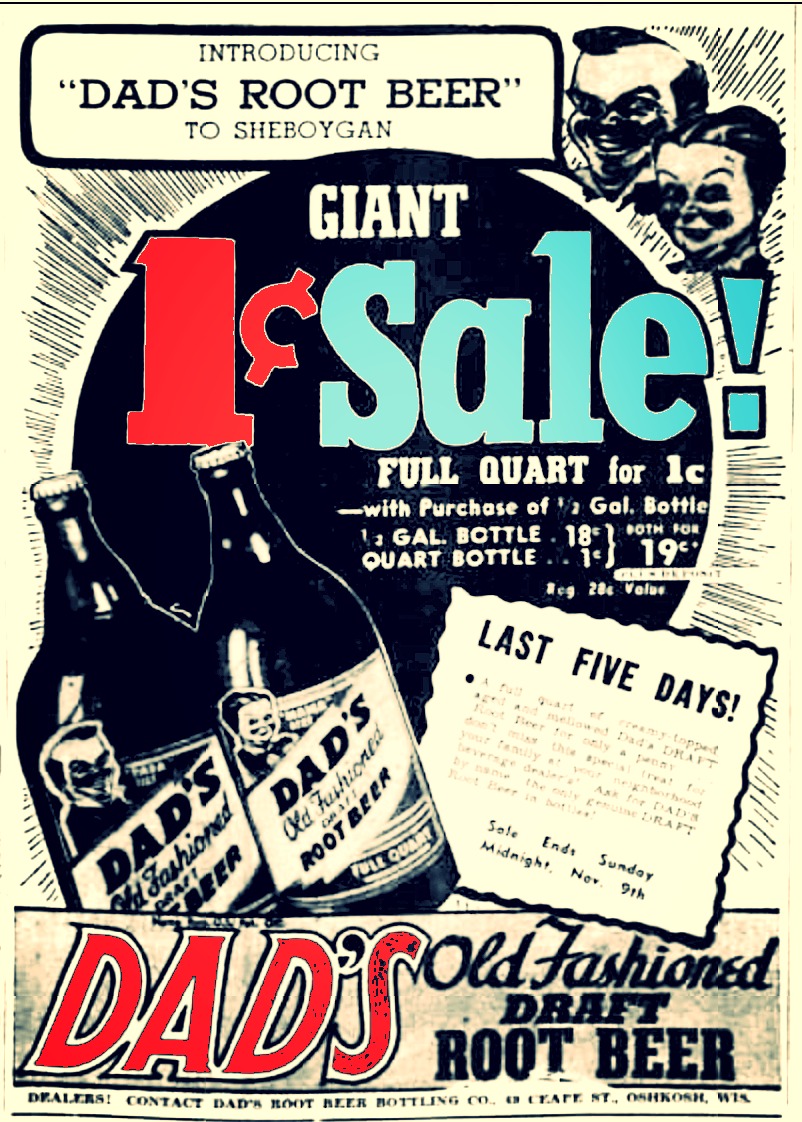

Special deals were advertised in small-town newspapers that autumn, offering a Mama jug for just one extra penny if you bought a Papa bottle at full price.

Special deals were advertised in small-town newspapers that autumn, offering a Mama jug for just one extra penny if you bought a Papa bottle at full price.

“Dad’s Root Beer is described as a creamy topped, aged and mellowed draft root beer,” the local paper in Zanesville, Ohio, reported in November of ’41, “and it’s retailed by neighborhood beverage dealers in convenient, large size economical bottles. Many have learned the refreshment of Dad’s root beer this past summer, and they will doubtless take advantage of this fall special. Many others will learn for the first time of its fine quality during this special 1-cent sale.”

The big sales push was a success. Within another ten years, Klapman and Berns would have 165 franchise bottlers distributing the yellow and blue brand across the continent. The most vital artery of the Dad’s network, naturally, was its Chicago headquarters—a hard-to-miss distillery / bottling plant / office complex located just off the Kennedy Expressway on the fringes of Avondale and Logan Square.

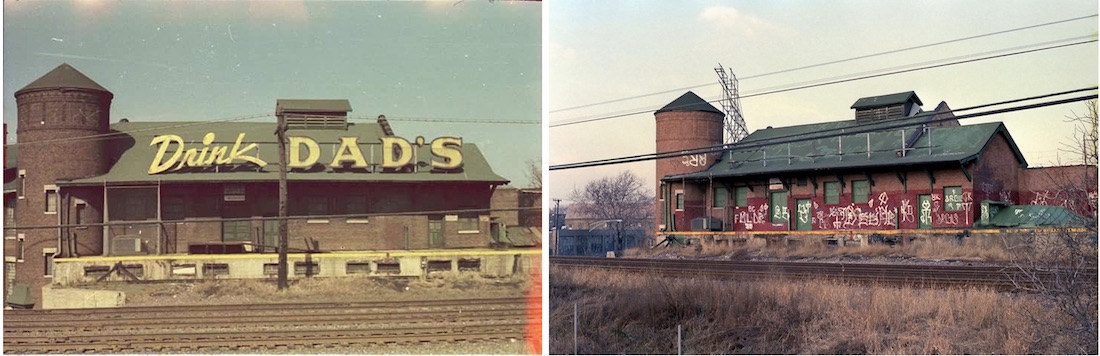

The plant, generally listed with a 2800 N. Talman Avenue mailing address, was originally a Borden’s Dairy facility back in the ’20s, and was already recognizable for the protruding turret / silo section at its south end. The turret remained in use when the Dad’s Root Beer Company took over the building in the late 1930s, but it was soon overshadowed a bit by a few new distractions—massive flashing neon signs beckoning to parched interstate drivers on their evening commutes: “Home of Dad’s: Tastes Like Root Beer Should,” “Drink Dad’s,” “DADS DADS DADS!”

[The Dad’s Root Beer factory at the intersection of N. Talman Ave., W. Diversey Ave., and N. Washtenaw Ave., 1960s]

[The Dad’s Root Beer factory at the intersection of N. Talman Ave., W. Diversey Ave., and N. Washtenaw Ave., 1960s]

During its thirty years at the Talman Avenue factory, Dad’s was a fiercely independent family-owned business, and, by no coincidence, a relatively small fry in its industry. They were routinely trampled over by the juggernauts of the Cola Wars, and couldn’t even overtake A&W in the lesser known Root Beer Squabbles. In local lore, however, Dad’s Old Fashioned Root Beer was king. And while they make the stuff in other places these days (Dad’s is now a division of Indiana’s Hedinger Brands, LLC), it has remained Chicago’s greatest contribution to the soda pop game . . . or at least second to Orange Crush.

In The Beginning: Before Old Fashioned Was Old Fashioned

In the standard corporate version of the Dad’s Root Beer creation myth, everything began in the middle of the Great Depression, when business partners Ely Klapman and Barney Berns discovered “that mellow old time flavor” while experimenting with carbonated concoctions in Klapman’s Wicker Park basement. They trademarked the “Dad’s” name in 1937—supposedly as a tribute to other dad brewers like themselves—and the rest was history.

That folksy image of two buddies with a ramshackle home brewing kit sure is cute and all, but unfortunately, it ain’t quite the complete story.

That folksy image of two buddies with a ramshackle home brewing kit sure is cute and all, but unfortunately, it ain’t quite the complete story.

Ely Klapman [1888-1980, pictured in 1950], for one, was no amateur hobbyist. The hard-working Jewish immigrant, who’d fled Poland before the outset of World War I, was already nearly 50 years old in 1937, and had been earning a living in the bottling business for over a decade, making his home right above his own factory space at 1337 N. Leavitt Street. In that sense, I guess, you could say that Dad’s Root Beer really was born in Klapman’s basement—it just was less of a happy accident.

Years later, when Ely’s son Jules Klapman (secretary-treasurer of Dad’s Root Beer) was asked to testify at a 1966 Congressional hearing on TV advertising rates, he took the opportunity to fill in some of the gaps in his company’s origins.

“Dad’s Root Beer was originally established as the Lion Beverage Company and then Chicago Distilled Water & Beverage Co. by my dad, Mr. Ely Klapman, as a sole proprietorship in the early 1920s,” Jules explained.

“The operation involved the bottling of soft drinks in various sizes and flavors, distributed and sold locally in Chicago. The business became a partnership in 1925 and was incorporated under the name of ‘Chicago Distilled Water & Beverage Co.’ and the sale of bottled distilled water was added to the carbonated beverage line of products.”

“The operation involved the bottling of soft drinks in various sizes and flavors, distributed and sold locally in Chicago. The business became a partnership in 1925 and was incorporated under the name of ‘Chicago Distilled Water & Beverage Co.’ and the sale of bottled distilled water was added to the carbonated beverage line of products.”

[pictured: Chicago Distilled Water & Beverage Co. “Sparkling Seltzer Water” bottle from the 1930s]

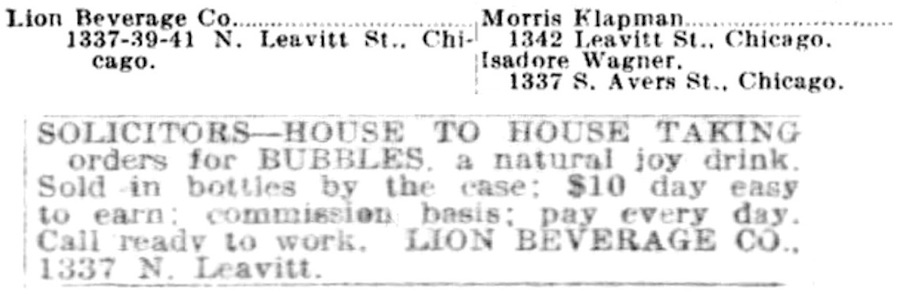

Interestingly, Jules omits any mention of his uncles Morris (1886-1968) and Sam Klapman (1880-1954)—Ely’s older brothers—who seemed to be equally involved in the bottling enterprise during its early days. In the 1922 edition of the Certified List of Domestic and Foreign Corporations of Illinois, in fact, it’s Morris Klapman—not Ely—who’s recorded as the president of the Lion Beverage Company, with Isadore Wagner as secretary-treasurer. Sam Klapman, meanwhile, is noted in his own 1954 obituary as having been a former “co-partner” in the Chicago Distilled Water & Beverage Company.

[First appearance of the Lion Beverage Co. in the Certified List of Domestic and Foreign Corporations, 1922, and a Lion Beverage advertisement from the Tribune in 1923, seeking salesman to move a “natural joy drink” called Bubbles]

[First appearance of the Lion Beverage Co. in the Certified List of Domestic and Foreign Corporations, 1922, and a Lion Beverage advertisement from the Tribune in 1923, seeking salesman to move a “natural joy drink” called Bubbles]

It’s unclear how or why little bro Ely—who was listed as a tailor on his 1917 draft card—eventually came to run the soda show. But from 1922 to 1939, his home/office on North Leavitt Street was abuzz with the rolling of kegs, stacking of crates, and clanking of bottles. And maybe some less kosher activities, as well.

The Soda Underworld

Any discussion of the drinking habits of Chicagoans during the ‘20s and ‘30s tends to begin and end with illegal hooch and the romantic rebellion of the Speakeasies. Understandably, most people don’t find Prohibition’s thriving soda pop industry quite as compelling, except perhaps for the odd novelty of giant breweries like Anheuser-Busch shifting over to non-alcoholic “near beers” to stay in business. As it turns out, though, not even the seemingly safe world of soft drinks was free of gritty Gangland connections.

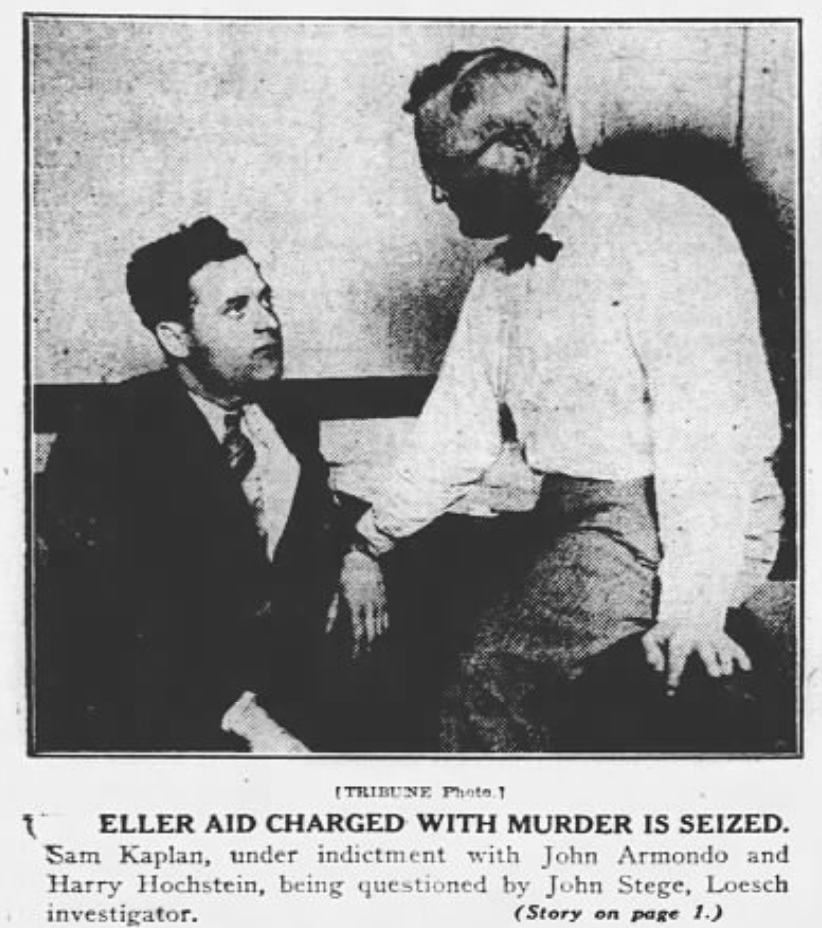

One particularly gruesome character who somehow came into Ely Klapman’s orbit in the late 1920s was a Jewish mobster by the name of Sam Kaplan (not to be confused with Ely’s own brother Sam Klapman).

[Gangster Sam Kaplan claimed to be an employee of the Chicago Distilled Water & Beverage Co. when he was arrested for a gangland murder in 1928]

[Gangster Sam Kaplan claimed to be an employee of the Chicago Distilled Water & Beverage Co. when he was arrested for a gangland murder in 1928]

On April 10, 1928, Kaplan was one of nearly a dozen henchmen dispatched by allies of Morris Eller—feared boss of the 20th Ward (the “Bloody 20th”)—to wreak havoc during the city’s infamous “Pineapple Primary” election day riots. This culminated in the cold blooded killing of an African-American lawyer named Octavius Granady, who had dared to challenge Eller’s seat as ward alderman. Multiple witnesses identified Kaplan as one of Granady’s assailants, and he was finally arrested for the crime on July 2, along with a known associate of Al Capone named Johnny Armando. When questioned by reporters about his involvement in the murder, however, Kaplan offered a very specific alibi in his defense—he had been out working for a certain bottling company that day.

“All these people accuse me because they know I am so close to the Ellers,” argued Kaplan [pictured]. “Where was I on primary day? I was just ridin’ around. I’m a business man.” He then pulled out a business card, according to the Chicago Tribune, on which was printed: “Chicago Distilled Water & Beverage Company, 1337 North Leavitt street, represented by Sam Kaplan.”

“All these people accuse me because they know I am so close to the Ellers,” argued Kaplan [pictured]. “Where was I on primary day? I was just ridin’ around. I’m a business man.” He then pulled out a business card, according to the Chicago Tribune, on which was printed: “Chicago Distilled Water & Beverage Company, 1337 North Leavitt street, represented by Sam Kaplan.”

To be fair, there is no evidence that Ely Klapman or anyone else at the Chicago Distilled Water & Beverage Co. was knowingly supporting bootlegging activities—let alone terrorist ones. We don’t even know if the “thug” Kaplan, as the Tribune called him, was even genuinely on the company payroll. Nonetheless, it paints a clear picture of how easy it was to cross paths with the organized crime element, no matter how small your little West Side bottling business might have been.

In case you’re wondering, Sam Kaplan and the other mobsters accused in the killing of Octavius Granady were all acquitted, thanks in part to Morris Eller’s son Emmanuel Eller (who happened to be a sitting judge in the district) and plenty of jury intimidation.

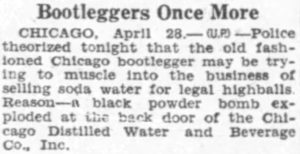

Flashing forward to 1935, with Prohibition already repealed, the Chicago Distilled Water & Beverage Company popped up in news reports for the wrong reasons once again.

Yup, the old pre-Dad’s factory on North Leavitt was literally bombed in the spring of ’35—not your average headache for Ely Klapman and his cohorts.

“Bootleggers Once More,” exclaimed the syndicated headlines in newspapers as far away as Great Falls, Montana. The Tribune took a slightly more measured approach, reporting that “damage estimated at several hundred dollars was caused early today [April 28, 1935] by a bomb explosion that tore out a rear wall of the plant of the Chicago Distilled Water and Beverage Company, 1339 North Leavitt street. Lieut. James Treacy of the bomb squad questioned Samuel Folloda, treasurer of the concern, but he could give no motive for the bombing.”

“Bootleggers Once More,” exclaimed the syndicated headlines in newspapers as far away as Great Falls, Montana. The Tribune took a slightly more measured approach, reporting that “damage estimated at several hundred dollars was caused early today [April 28, 1935] by a bomb explosion that tore out a rear wall of the plant of the Chicago Distilled Water and Beverage Company, 1339 North Leavitt street. Lieut. James Treacy of the bomb squad questioned Samuel Folloda, treasurer of the concern, but he could give no motive for the bombing.”

Naturally, Jules Klapman didn’t offer any insights into these events during his congressional testimony 30 years later (he’d only been a teenager at the time himself), but it sure seems like the family business—in the years just before the creation of Dad’s Root Beer—wasn’t all sunshine and rainbows.

All Root Beer, All the Time

By 1938, Bernard “Barney” Berns (1903-1983) had joined Chicago Distilled Water as its vice president, and Ely Klapman’s 20 year-old son, Jules, was a newly anointed full-time employee, as well. This was the magical year, according to Jules, that “the principals of the company recognized that specialization was necessary if the company was to achieve substantial growth. Root beer was selected as the flavor to promote, as it had a long history of household flavor, and the name ‘Dad’s Old Fashioned Root Beer’ was adopted as it evoked the traditional image of the root beer brewed at home by the father of the household. The first sale of bottled ‘Dad’s’ root beer was made in September of 1938.”

It’s worth noting that Dad’s was hardly the first commercial root beer on the block. Charles Elmer Hires had pioneered the beverage back in the 1870s, and Barq’s arrived around the turn of the century. IBC and A&W had entered the arena at the beginning of Prohibition, wisely foreseeing a new upswing in root beer’s popularity. And so, the consumer had his or her options by the late 1930s. Even so, the clever marketing of Dad’s—and those helpful discount deals—gained it some traction.

It’s worth noting that Dad’s was hardly the first commercial root beer on the block. Charles Elmer Hires had pioneered the beverage back in the 1870s, and Barq’s arrived around the turn of the century. IBC and A&W had entered the arena at the beginning of Prohibition, wisely foreseeing a new upswing in root beer’s popularity. And so, the consumer had his or her options by the late 1930s. Even so, the clever marketing of Dad’s—and those helpful discount deals—gained it some traction.

“The market reception of Dad’s root beer in Chicago was unusually enthusiastic,” according to Jules Klapman, “and inquiries began to be received from soft drink bottlers in surrounding areas such as Gary and Milwaukee, who wanted distribution rights. In the latter part of 1939, Dad’s root beer was franchised to independent bottlers in those areas and thereby the corporation entered into the franchise part of the soft drink business. It was at that time the old plant and three warehouses became completely inadequate and the company moved to its present location at 2800 North Talman Avenue, Chicago, Ill.”

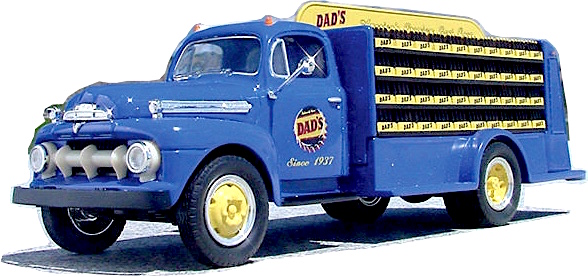

Along with staffing the new factory—which may or may not have been selected based on the large Polish community in and around Avondale—dozens of ads were also placed seeking new Dad’s delivery drivers for the local fleet.

There were thousands of bottles of beer on the wall and not many trucks to move it, so if a driver got hurt and couldn’t work, his wife—in one specific example, at least—would step right in and pick up his route.

On March 22, 1940, the front page of the Tribune included a proto-feminist profile in courage (masquerading as a fluff piece) about an enterprising young housewife named Ann Pekarek, who started driving a Dad’s Root Beer truck after her husband, Frank, broke his leg and couldn’t do the job himself. The story was titled: “A Tale About a Swap; Apron for a Truck.”

“Ann, a trim brunette of 30, went to Frank’s employer, Barney Berne [sic, Berns], vice president of the Chicago Distilled Water and Beverage company at 2800 North Talman avenue,” the article stated.

“‘Frank’s going to be laid up a long time,’ she said. ‘I want to hold his job for him. I think I can sell and deliver as well as anybody you could get.’

“Berns was skeptical about her ability to wrestle 65 pound cases. But he gave Ann her chance. Ever since, she’s been driving 600 miles a week, selling beverages and delivering two truckloads a day with the aid of a single helper.

“Berns was skeptical about her ability to wrestle 65 pound cases. But he gave Ann her chance. Ever since, she’s been driving 600 miles a week, selling beverages and delivering two truckloads a day with the aid of a single helper.

“‘Somebody at our house has to earn,’ she said yesterday. ‘Frank can’t so I had to.’”

“Employer Berns was asked what he thought. ‘Well, I guess I’m neutral,’ he said. ‘But sales are up 40 percent since Ann’s been on the truck.’”

Whether it was entirely Ann’s doing is debatable, but business was definitely picking up in 1940. Later that same year, the company finally ditched its old, long-winded Chicago Distilled etc etc name in favor of the “Dad’s Root Beer Company.” The rollout of the Papa, Mama, and Junior bottles followed in ‘41, and new franchises were being added right up until early December, when the Pearl Harbor bombing put everything on pause.

Four years later, with war rationing concluded and veterans returning to their factory jobs, Dad’s ramped up its network once again, working exclusively with independent bottlers rather than selling out to the big guys—for a while, at least.

Battling the Bottling Giants

In 1948, Barney Berns made his own appearance on Capitol Hill, testifying before a Senate committee that was looking into the potential monopolization of the soda business by Coca Cola.

Frustratedly referring to Coke’s exclusive, single-product vending machines as “red devils,” Berns complained that “once a [Coke] machine goes in an average small outlet—such as these offices or those retail stores or gasoline stations—you are eliminated from that outlet 100 percent. . . . They have placed them by the thousands. You see them strung across the entire country.”

To forge their own way, Dad’s had to be innovative and try new, often unusual things. The half-gallon Papa bottle, as an example, was the first of its kind. Later, in the post-war era, the company set an example for the industry by selling its own sirup concentrate not just to its franchise bottlers, but direct to fountain machine operators, as well—a contentious stance at the time.

To forge their own way, Dad’s had to be innovative and try new, often unusual things. The half-gallon Papa bottle, as an example, was the first of its kind. Later, in the post-war era, the company set an example for the industry by selling its own sirup concentrate not just to its franchise bottlers, but direct to fountain machine operators, as well—a contentious stance at the time.

“Because of its ‘quality control program’ for operator-made sirup,” Billboard reported in 1952, “Dad’s permits full brand promotion. Plastic covered fluorescent signs and decals for vendors are offered to sirup-making operators as well as those purchasing the finished product. . . . While Dad’s sells its finished sirup through 33 processing plants over the country, its concentrate is shipped only from the Chicago parent plant.”

Like the manager of an indie music label or a Minor League baseball team, Jules Klapman—who took an increasing leadership role at Dad’s as his own dad reached retirement age in the 1950s—seemed to relish the role of the underdog.

In contrast to Barney Berns, Jules responded to Congressional questions about Coca Cola’s dominance with a sort of glee in 1966.

“Well, I will tell you one thing it has done for my organization,” he said. “It has kept them on their toes.

“I am of the opinion—and this has been based on my own experience, being in this business all my life basically, that the big giants in this industry, the one big advantage they have is the dollar. We know that. They buy good facilities, and they buy discrimination in advertising. However, we have one advantage that they do not have. We don’t have the complexities. We do not have the forms and the meetings and the inner-office correspondence to go through before we get a job done. In our particular organization, when we want to get something done, we call each other on the intercom phone and in 20 minutes it is on its way. Secondly, in the selling field itself, we feel we have an advantage in that we are much closer personally with the people who buy our product.”

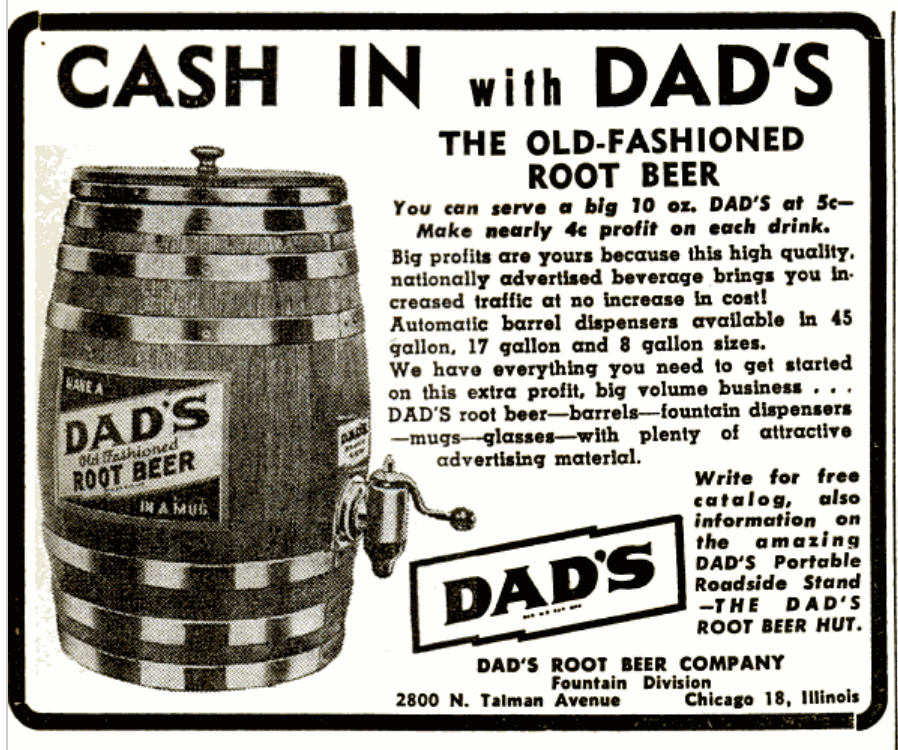

[In this 1950 advertisement, Dad’s offers its own barrel dispensers and other accessories to vendors. The company was also one of the few in the industry to sell its sirup concentrate direct to fountain operators]

[In this 1950 advertisement, Dad’s offers its own barrel dispensers and other accessories to vendors. The company was also one of the few in the industry to sell its sirup concentrate direct to fountain operators]

Hey Jules

Jules Klapman (1918-2002) was as a colorful character, literally and figuratively—he was noted for his loud painted ties and a contradictory disinterest in wearing socks. “Born and raised in the soft drink business,” as he put it, he drove a delivery route to fund his way to an accounting degree from the Walton School of Commerce, then served as an office manager before taking over the secretary role at Dad’s after the death of Louis Belman in 1954.

After Jules’s own death in 2002, his wife Rochelle described him as someone who was “gregarious and loved really living life,” but also “never cared what people thought. He did what he thought was right.

“He could be very stubborn and a person of his convictions, that’s for sure,” she added. “He was strong in his honesty and expected the same from others.”

“He could be very stubborn and a person of his convictions, that’s for sure,” she added. “He was strong in his honesty and expected the same from others.”

In the 1960s, Jules and a sales manager named Roy Gurvey were instrumental in bringing Dad’s to the international market, selling to Japan and Hong Kong and supplying cans to thirsty American soldiers in Vietnam. The company championed the six-pack long before it became the industry standard, and it even ventured out of the root beer niche a few times with offerings like “Flip”—a grapefruit lemon-lime drink.

“It’s the old story that in order to survive in our industry, we have to do things that are out of the ordinary and sometimes beyond comprehension,” Klapman said, “but we have managed to formulate these policies which have proven themselves to be worthwhile in our particular case.”

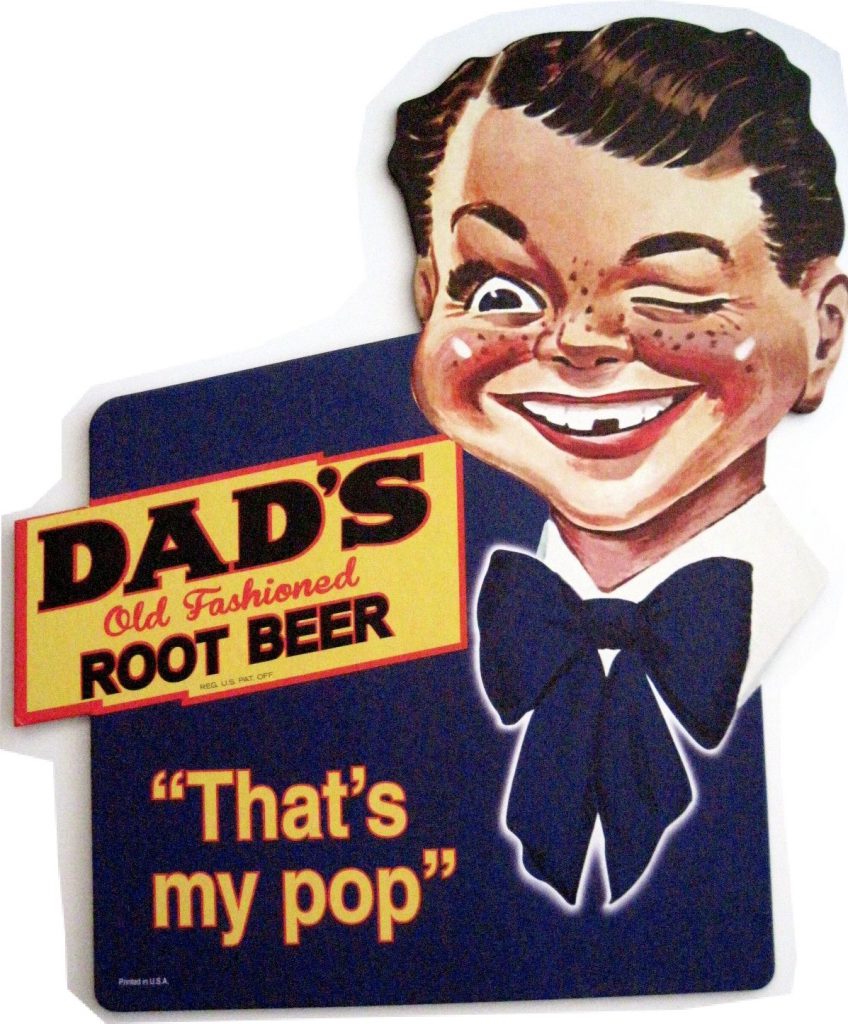

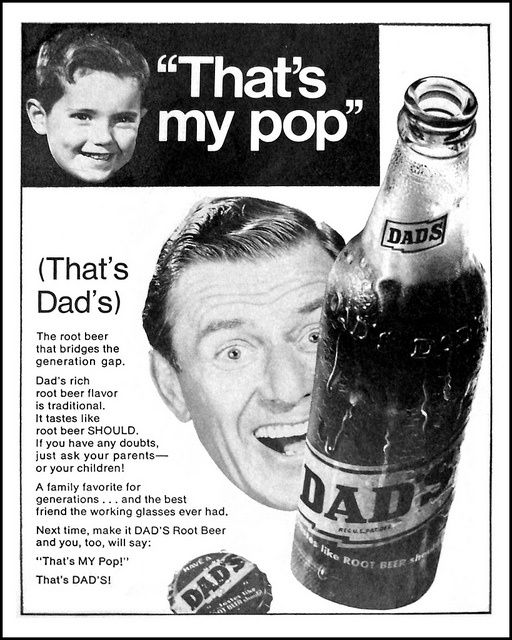

“That’s My Pop”

“The root beer that bridges the generation gap. Dad’s rich root beer flavor is traditional. It tastes like root beer SHOULD. If you have any doubts, just ask your parents—or your children! A family favorite for generations . . . and the best friend the working glasses ever had. Next time, make it DAD’S Root Beer and you, too, will say: ‘That’s MY Pop!’ That’s DAD’S!”—1969 Dad’s advertisement

“The root beer that bridges the generation gap. Dad’s rich root beer flavor is traditional. It tastes like root beer SHOULD. If you have any doubts, just ask your parents—or your children! A family favorite for generations . . . and the best friend the working glasses ever had. Next time, make it DAD’S Root Beer and you, too, will say: ‘That’s MY Pop!’ That’s DAD’S!”—1969 Dad’s advertisement

That’s not a typo in the ad above, by the way. They went with “working glasses” instead of “working classes.” I guess because it’s a play on words—ya know, cuz root beer is generally poured into a glass . . . working glasses. Anyway, by the dawning of the 1970s, Dad’s impressive half-century as an independent business was clearly approaching its end.

In 1971, the Klapman and Berns families finally tired of the uphill climb. They agreed to sell the business to IC Industries, owners of Pepsi, with Jules Klapman and Roy Gurvey staying on to lead the Dad’s division up until 1980.

As part of the sale, Dad’s eventually abandoned the production end of its Talman Avenue plant, and most bottling was handled at the Pepsi plants on Kolmar Ave. & Grand and later 51st Street & Union Ave. When IC/PepsiCo sold Dad’s to the Monarch Beverage Company of Atlanta in 1986, the root beer that “bridged the generation gap” was selling over 12 million cases per year, and yet still owned less than 0.5% of the national soft drink market, according to the Tribune.

[Two anonymous Dad’s Root Beer reps at a sales event in the 1970s (can’t quite read those name tags!). If either of these people are you or somebody you know, let us know.]

[Two anonymous Dad’s Root Beer reps at a sales event in the 1970s (can’t quite read those name tags!). If either of these people are you or somebody you know, let us know.]

Joining Monarch, incidentally, made Dad’s a part of the Coca Cola bottling network. A bitter pill perhaps, but this too was short lived. The division was sold again in 2007, and remains a property of Hedinger Brands—a former Pepsi distributor based in Jasper, Indiana.

So, what became of the old Dad’s Chicago factory after all the neon signs came down? Well, after serving as a warehouse in the ‘80s and an abandoned, graffiti laden horror movie set in the ‘90s, the surviving section of the old plant was finally gutted in the 2000s and renovated into 55 condominium units. It’s called the “Borden Dairy Commons,” because I guess the “Dad’s Apartments” or “Root Beer Estates” didn’t have the same ring to it.

[Above: The former Dad’s plant’s transition from its neon days on the left (photo by Patrick Crane) to its graffiti days in the ’90s. Below: The renovated complex, now known as the Dairy Commons Lofts, opened in the early 2000s]

[Above: The former Dad’s plant’s transition from its neon days on the left (photo by Patrick Crane) to its graffiti days in the ’90s. Below: The renovated complex, now known as the Dairy Commons Lofts, opened in the early 2000s]

One of the new condos is actually built right into the original turret itself (see above), which looks largely the same on the outside, but is now an ultra-modern, 4,000 sq. ft. loft on the inside, complete with catwalks, 18-foot high ceilings, and an oak-paneled circular library in its “attic.”

I guess you could say that Dad’s Root Beer has undergone a similar transformation. The classic label still looks the same on current cans and (plastic) bottles, but the inner workings of the business are pretty unrecognizable from the one the Klapmans ran for so many years.

Most people who buy a Dad’s Old Fashioned Root Beer these days probably presume the “old fashioned” is a reference to the fact that the drink’s been around for 80 years. But now you know better—it was old fashioned from the get go, and staying old in fashion is always the best way to avoid falling out of it.

p.s. The return of genuine draft root beer, produced by hipster micro-brews, has recently become a trend in Chicago. I can’t speak to which of the new brands are the best, but if any of them want to compare their formula to a 1960s Chicago-brewed Dad’s Root Beer still sealed in its original bottle, I’ll await your asking price. I’m sure all the carbonation is just fine in there.

[1980s Dad’s bottlecap neon sign, designed by Mario Pancino]

[Center photograph above courtesy of Patrick Crane]

[Center photograph above courtesy of Patrick Crane]

SOURCES:

Dad’s Root Beer Official Website

“Possible Anti-Competitive Effects of Sale of Network TV Advertising” – Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Anti-Trust and Monopoly, 89th Congress, May 24-June 3, 1966

“Dad’s Root Beer Sale Now On” – Zanesville Times Recorder, Nov 10, 1941

“Concentrate Question Divides Drink Mfrs. Into Three Camps” – Billboard, March 1, 1952

“Bootleggers Once More” – Great Falls Tribune (Montana), April 29, 1935

“Bomb Explosion Tears Out Wall of Beverage Plant” – Chicago Tribune, April 28, 1935

Certified List of Domestic and Foreign Corporations of Illinois – 1922-1939

“A Tale About a Swap; Apron for a Truck” – Chicago Tribune, March 22, 1940

“Senators Study Coke’s Position” – Decatur Daily Review, Dec 7, 1948

“Roy Gurvey, Who Helped Build Dad’s Root Beer into Global Brand, Dies at 92” – Chicago Tribune, Aug 20, 2015

“Louis M. Belman (obit)” – Chicago Tribune, Feb 17, 1954

“Kick Back With a Book in Your Own Turret: 2827 N. Washtenaw in Avondale” – CribChatter.com

“Kaplan Identified as Election Day Killer” – Chicago Tribune, July 3, 1928

Gangland Chicago: Criminality and Lawlessness in the Windy City, by Richard C. Lindberg

Deadly Valentines: The Story of Capone’s Henchman “Machine Gun” Jack McGurn and Louise Rolfe, His Blonde Alibi, by Jeffrey Gusfield

“Dad’s Root Beer Co. vs Atkin” – U.S. District Court, E.D. Pennsylvania, 1950″

“IC Unloads Dad’s, Bubble Up” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 22, 1987

“Jules Klapman, 84, Took Dad’s Root Beer National” – Chicago Tribune, Oct 11, 2002

“Sales Top 75% at 2800 Dairy Commons” – Chicago Tribune, Sept 29, 2001

Archived Reader Comments:

“A Chicago institution. I was raised on Leavitt Street too, a couple miles North, to fondly remember drinking a Dad’s as a boy and driving past the Talman factory on our trips to Downtown Chicago.” —Nicholas Linden, 2020

I have the same Dad’s “Bottlecap” neon sign as shown in the photos above which was made by GHN in Harbor City, Ca in 1986 for Beatrice Foods who owned the logo at the time.

It has dual 9000 transformers and is approximately 33″ sq.

I live in the old Dad’s building in Chicago. I also have nice shots of when it was a Dairy, and an article when the place was robbed, and the security guard tied up. Let me know if the author wants them to flesh out this awesome piece.

I grew up just 2 blocks away from here in the 70s on Rockwell. We would get free pop from workers and wow, it was so good. Sorry to see it’s not up and running anymore but the photos are such sweet memories of once was. Thank you for sharing.

Can you give me an idea what a Mama quart sized bottle would be worth, never opened with nice label.

youll

love

DA

G

REG. U,S. PAT, OFF.

tastes like ROOT BEER should !

I have a sign with slogan listed above. Can you tell me the decade it was manufactured

Cheers Michael

I have a Dads root beer truck (go cart). I won it from a raffle at a store many years ago. Just wondering how much it’s worth. The word Birds is on the front of it.

When was Dad’s Red Cream Soda introduced?

I grew up in Chicago in the 50’s, 60’s and 70’s and vividly remember driving past the Dad’s Root Beer factory thousands of times. It was my favorite root beer back then and still is today. I but it by the case (I have several at home right now) at Costco. I have given cases of it to friends and bring it with me when I go to parties and get-togethers. As long as I can find it I will keep buying it.

What is the value of an unopened Papa sized bottle?

My father’s best friend was Aaron Klapman, his brother was Jimmy. Do these names figure in the mix, cause my Dad said they were descendant to the Dad’s family.

Do you happened to know who Jules Kaplan married?

Jack Margolis

Jules Klapman was married to Rochelle Klapman (1922-2022).

Rochelle, my mother, worked for Jules Klapman as his secretary prior to their marriage, and long before #metoo!

And, please note that Kaplan is not the same as Klapman.

In the 1940s (and maybe continuing in the early 1950s) there was a brief and often-repeated jingle sung on the radio between programs, at least on Chicago-area radio, that simply went: “Dad’s Old Fashioned Root BEER, Dad’s Old Fashioned Root BEER, ….” Is there anywhere on the Internet or anywhere else that I can hear this original jingle?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D20yo4Zeyu0

I can’t find anything about a bottle I have. It is 7oz brown bottle. No picture in side corner of Jr. The back says bottled in Pittsburgh. Pa

When was the dad’s bottling plant in operation in oak Washington.?